Abstract

Three free-living marine nematode species of the family Desmodoridae are described and illustrated based on light and scanning electron microscopy. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. was collected from muddy sand sediments at Eulwangri Beach, Incheon, Korea, and P. capitata sp. nov. from sublittoral muddy sediments off Jindo Island, Korea. Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978, is also recorded for the first time from Korean waters, based on specimens from sandy sediments off Jeju Island. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. is distinguished from P. parva Gagarin & Thanh, 2008 and related congeners by having a tripartite cephalic region consisting of a jar-shaped main capsule, an anterior transition zone with weaker cuticle bearing the cephalic setae, and a highly elevated hat-shaped labial region. It additionally shows a sexually dimorphic amphideal fovea, a unique arrangement of precloacal thorns, a gubernaculum with a dorsal apophysis, and ventral thorns lacking cuticular hillocks. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. is characterized by a cephalic region composed of a rounded labial region and a thickly cuticularized main capsule, together with a sexually dimorphic amphideal fovea, arcuate spicules with a large hammer-shaped capitulum, a gubernaculum with a dorsal apophysis, and 3–8 precloacal and 3–5 postcloacal thorns arranged in a row. Molecular data (18S and 28S rRNA) were generated for both new species, and phylogenetic analyses support their placement within the genus Pseudochromadora and provide molecular evidence distinguishing them from closely related congeners. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) observations of M. itoi also revealed multiple configurations of the buccal cavity, providing additional morphological information useful for understanding structural variation within the genus. These findings refine the taxonomic framework within the Desmodoridae and expand current knowledge of morphological diversity in free-living marine nematodes.

1. Introduction

The family Desmodoridae Filipjev, 1922, is among the most morphologically diverse groups of free-living marine nematodes. Members of this family are found across a wide range of habitats, including tropical coral reefs, sandy beaches, seagrass meadows [1], deep-sea sediments [2,3], and freshwater environments (although rarely) [4]. Taxonomic revisions over recent decades have reorganized the classification of several subfamilies [1,5,6]. According to Hodda (2022), the family currently comprises five subfamilies, 48 genera, and approximately 420 valid species [7]. Desmodorid nematodes are ecologically important in benthic ecosystems due to their high morphological variability and frequent associations with sulphur-oxidizing bacteria, which may enhance microbial productivity and nutrient cycling in sediments [8,9]. However, species-level identification remains challenging because of their small body size and morphological similarity. Diagnostic traits such as cuticular annulations, cephalic capsule morphology, buccal cavity structure, and sexual dimorphism in the amphideal fovea are therefore essential for species delimitation [10,11,12].

Within the Desmodoridae, the genera Pseudochromadora and Metachromadora are distinguished by subtle but consistent morphological characters. Pseudochromadora is typically characterized by a short cylindrical body, a cephalic region composed of two (occasionally three) parts, including a short labial region (rounded or hat-shaped) and a heavily cuticularized main capsule region, and a narrow buccal cavity bearing a dorsal tooth and two ventrosublateral teeth. Amphideal fovea are typically unispiral but may also be loop-shaped or cryptospiral, and are often sexually dimorphic. Males often possess one or more rows of copulatory thorns and postcloacal thorns, whose number and arrangement vary among species [13,14]. Species of this genus have been reported from various coastal habitats, including sandy and muddy sediments, estuaries, mangrove swamps, intertidal zones, and shallow subtidal areas, with occasional records from brackish and freshwater environments [4,15]. To date, approximately 17 valid species are recognized worldwide [14]. In contrast, Metachromadora is recognized by its wider buccal cavity with a well-developed dorsal tooth and two ventrosublateral teeth, as well as spiral or cryptospiral amphideal fovea [12,16]. The accurate observation of these fine-scale traits requires high-resolution light microscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), both of which are essential for modern taxonomic and phylogenetic studies of this family.

In Korean waters, knowledge of desmodorid nematodes remains limited despite a growing interest in marine nematode diversity. Until recently, only two species—Onyx disparamphis Tchesunov, Jeong and Lee, 2022 and Spirinia koreana Son and Jeong, 2025—had been recorded [17,18]. The subsequent discovery of Pseudochromadora microacantha Kim & Jeong, 2025 and P. typica Kim & Jeong, 2025 [14] increased the known Korean fauna to four species, underscoring the need for continued taxonomic investigation of this group. In this context, the present study describes two new species—Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., collected from intertidal sandy sediments at Eulwangri Beach, Incheon, and Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., from sublittoral muddy sediments off Jindo Island—and reports Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978 from Korea for the first time, based on specimens collected from sandy sediments off Jeju Island. The objective of this study is to expand the taxonomic knowledge of Desmodoridae in Korea by documenting these new species of Pseudochromadora and providing the first Korean record of Metachromadora itoi.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Morphological Analysis

Sediment samples were collected from three coastal sites in Korea. Intertidal samples were taken from muddy sand flats at Eulwangri Beach (Incheon) and sandy shores at Sinchang-ri (Jeju Island). At both intertidal locations, surface sediments (0–10 cm depth) were scooped using a hand shovel during low tide. The samples were sieved on-site through a 64 μm mesh to retain the meiofauna and fixed in 5% buffered formaldehyde solution for storage. Sublittoral samples were collected from muddy sediments off Jindo Island using a van Veen grab sampler and processed using the same method.

In the laboratory, meiofauna were extracted using Ludox HS40 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) flotation with two centrifugation steps, followed by rinsing through a 64 μm mesh [19]. Individual nematodes were isolated under a LEICA 205 C stereo microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) using a Pasteur pipette and transferred to 3% glycerol solution. The specimens were gradually dehydrated at room temperature over approximately 10 days. Permanent mounts were prepared by placing nematodes in anhydrous glycerin on HS slides using the wax-ring method [20].

Morphological observations and measurements were conducted using an Olympus BX53 compound microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with cellSens Standard 1.16 software. Photomicrographs were taken using a LEICA DM2500 LED microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a LEICA K5C CMOS camera and processed in Adobe Photoshop 2022. Line drawings were prepared using a drawing tube attached to the LEICA DM2500 LED microscope under a 100× oil-immersion objective and refined digitally using a Wacom Cintiq 22 tablet and Adobe Illustrator 2023.

Morphometric ratios a, b, and c were calculated following standard nematode taxonomy, where a = body length/maximum body diameter, b = body length/pharynx length, and c = body length/tail length.

For SEM, selected specimens were rinsed twice with distilled water to remove residual fixatives, freeze-dried on an FDU-1200 cooling stage (EYELA, Tokyo, Japan), mounted on aluminum stubs, sputter-coated with gold/palladium, and examined under a SEC SNE-3200M desktop SEM (SEC, Suwon, Republic of Korea) to observe fine surface structures. All SEM micrographs were obtained from non-type specimens. These specimens were collected on the same date and from the same locality as the type series but were not designated as types because SEM preparation is destructive.

2.2. Molecular Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from individual nematodes using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Partial fragments of the 18S and 28S rRNA genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The 18S fragment was amplified using the primer pair R (5′-AAAGATTAAGCCATGCATGT-3′) and T (5′-ACCTTGTTACGACTTTTA-3′), newly designed in this study. The 28S (D2–D3) fragment was amplified using primers D2A and D3B following the protocol of [21]. PCR products were purified and sequenced commercially.

Sequence chromatograms were edited using Chromas. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using concatenated 18S + 28S rRNA sequences and included closely related genera within Desmodoridae and Draconematidae, following the taxon sampling strategy of [14]. All publicly available Pseudochromadora sequences were retrieved from GenBank, excluding unidentified entries labeled as P. obesa. Based on this strategy, Nudora ilhabelae (Desmodorina, Desmodorida) and Monoposthia costata (Spirininae, Desmodoridae) were used as outgroup taxa. All sequence data used in this study, together with the corresponding GenBank accession numbers, are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

The 18S and 28S rRNA sequences were aligned using the auto-alignment strategy in MAFFT v7 [22] and manually checked in MEGA X (Kumar et al. [23]). Concatenation was performed in FASconCAT-G (Kück & Longo [24]; https://github.com/PatrickKueck/FASconCAT-G, accessed 18 December 2025) in the order 18S followed by 28S. PartitionFinder v2.1.1 [25], under the Bayesian Information Criterion, identified GTR + I + G for 18S and SYM + G for 28S as the best-fitting models.

Bayesian inference (BI) analyses were conducted using MrBayes v3.2.6 [26]. Two independent runs of four Metropolis-coupled Markov chains were performed for 5 × 106 generations, sampling every 1000 generations, with the first 10% discarded as burn-in. Convergence was assessed using standard MrBayes diagnostics (ESS > 200, ASDSF < 0.01, PSRF ≈ 1.00). A majority-rule consensus tree was subsequently generated.

Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using IQ-TREE [27], with node support assessed using the ultrafast bootstrap method with 5000 replicates [28]. The final consensus trees from BI and ML analyses were visualized in FigTree v1.4.4 [29].

Species divergence was evaluated using uncorrected pairwise distances (p-distance) based on both 18S and 28S rDNA sequences. p-distances were calculated across all nucleotide positions using MEGA 12.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Analysis of Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov.

- Systematics

- Class Chromadorea Inglis, 1983

- Order Desmodorida De Coninck, 1965

- Family Desmodoridae Filipjev, 1922

- Subfamily Desmodorinae Filipjev, 1922

- Genus Pseudochromadora Daday, 1899

- Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, Table 1)

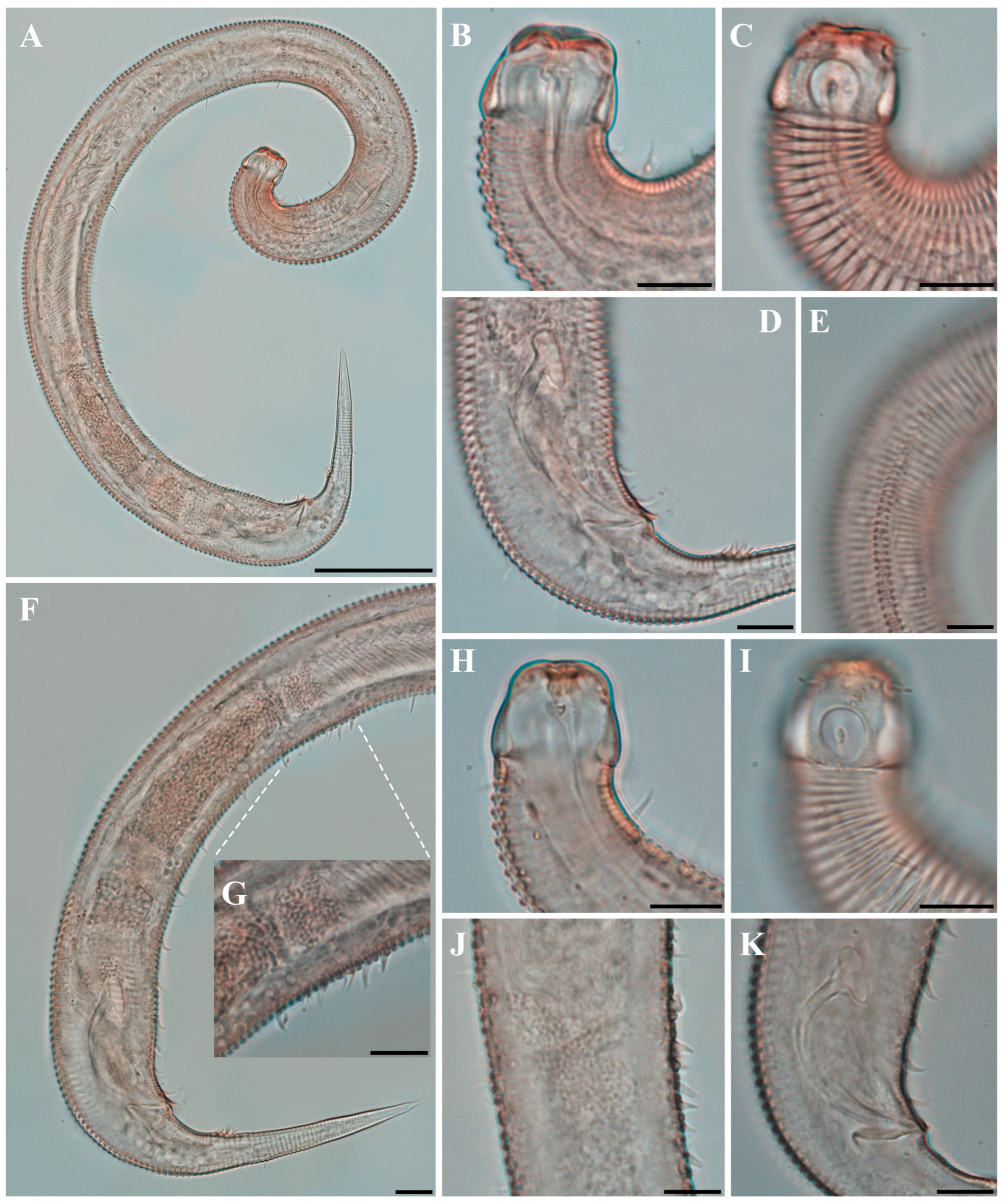

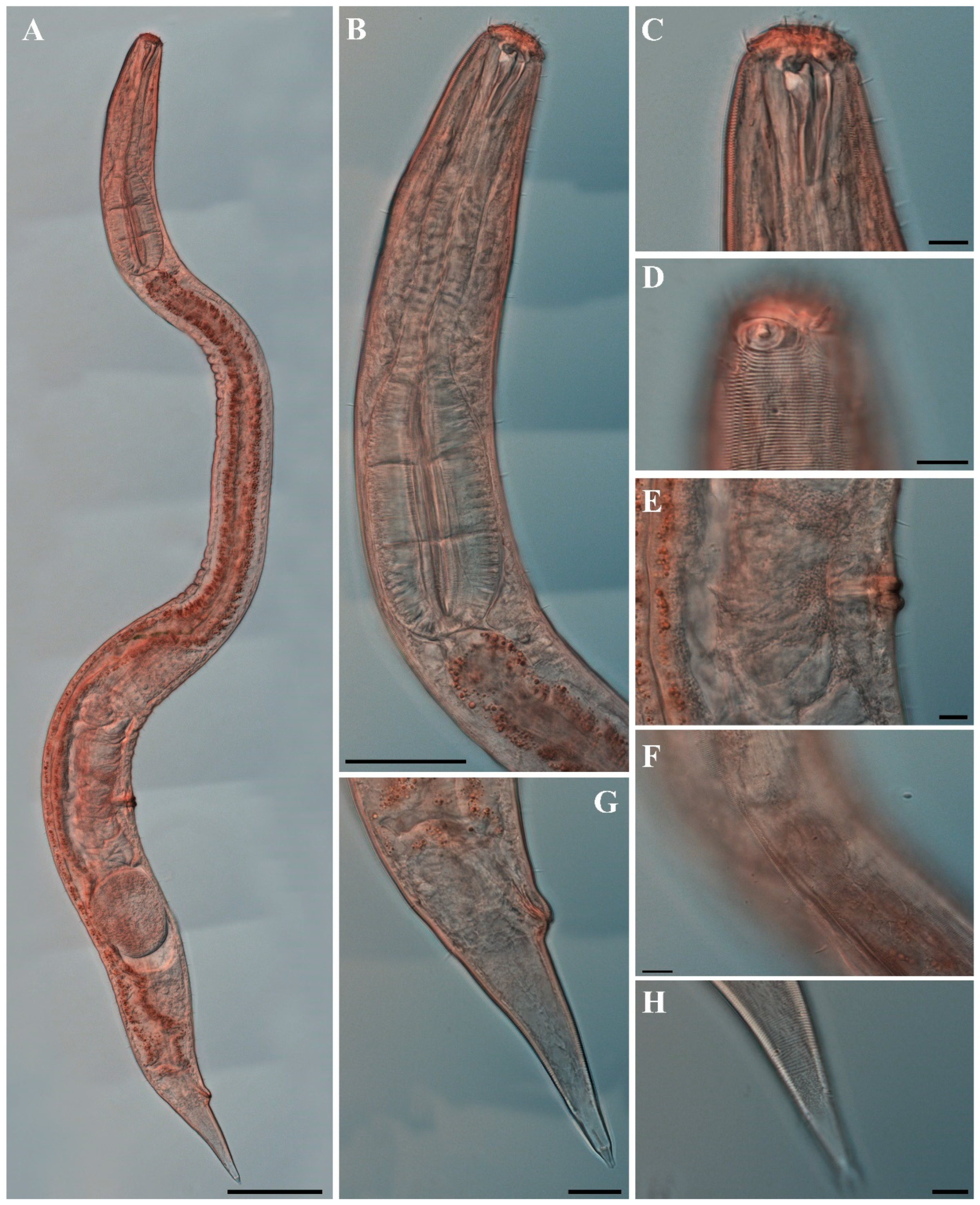

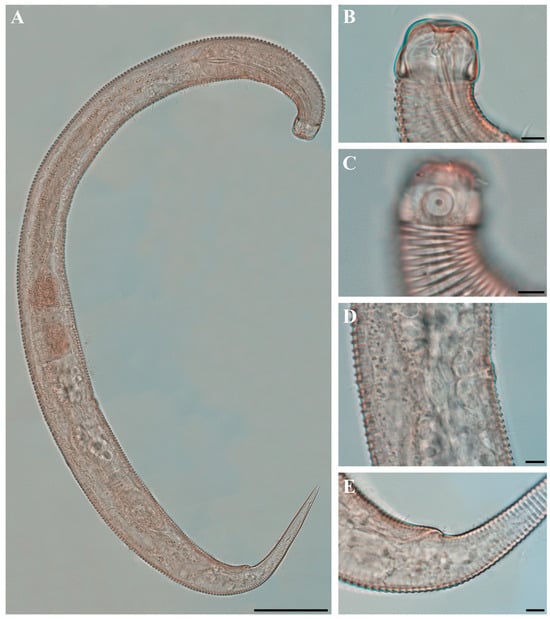

Figure 1. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., (A,F,G) holotype male; (B–E) paratype males. (A) entire body; (B) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section (KIOST NEM-1-2807); (C) external view of cephalic region (KIOST NEM-1-2807); (D) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section (KIOST-NEM-1-2812); (E) external view of cephalic region (KIOST NEM-1-2812); (F) pharyngeal body region; (G) posterior body region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–E) = 10 µm; (F,G) = 20 µm.

Figure 1. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., (A,F,G) holotype male; (B–E) paratype males. (A) entire body; (B) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section (KIOST NEM-1-2807); (C) external view of cephalic region (KIOST NEM-1-2807); (D) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section (KIOST-NEM-1-2812); (E) external view of cephalic region (KIOST NEM-1-2812); (F) pharyngeal body region; (G) posterior body region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–E) = 10 µm; (F,G) = 20 µm. Figure 2. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2819). (A) entire body; (B) anterior region; (C) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section; (D) external view of cephalic region; (E) tail region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B) = 20 µm; (C–E) = 10 µm.

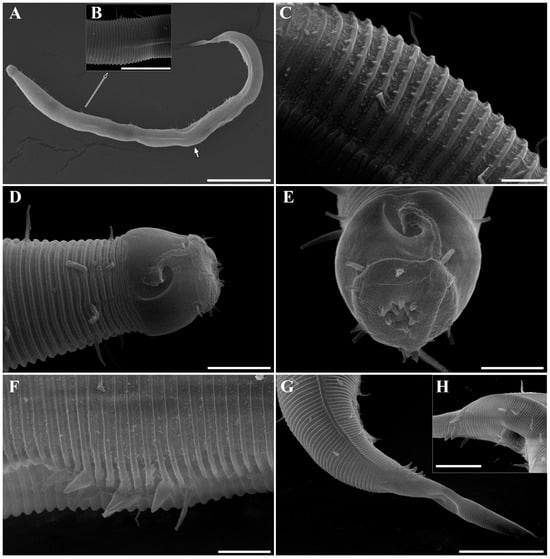

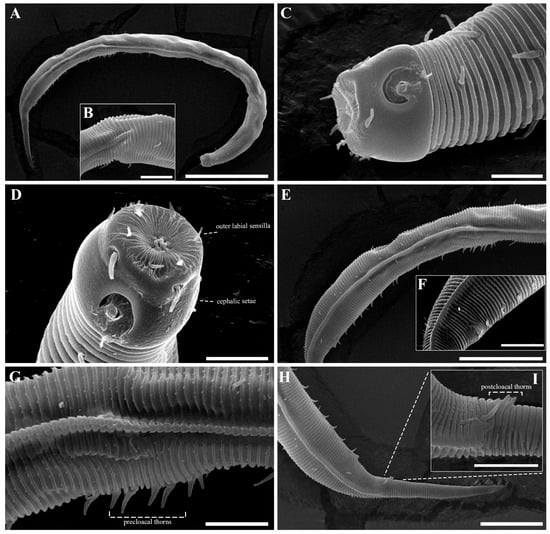

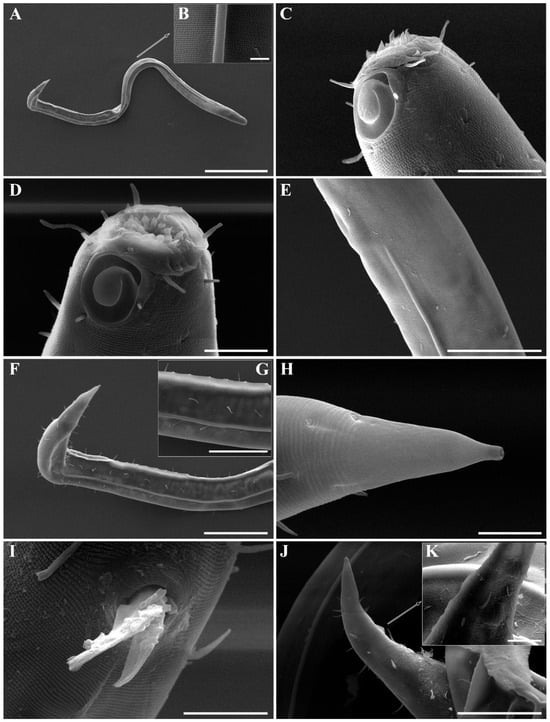

Figure 2. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2819). (A) entire body; (B) anterior region; (C) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section; (D) external view of cephalic region; (E) tail region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B) = 20 µm; (C–E) = 10 µm. Figure 3. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) micrographs, male 1. (A) entire body; (B) lateral alae starting region; (C) dorsal spiny posterior annule margins; (D) cephalic region; (E) oblique en face view of labial region; (F) precloacal thorn group; (G) tail region; (H) oblique view of spicules and postcoloacal thorn region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 30 µm; (C,E,F) = 5 µm; (D,H) = 10 µm; (G) = 20 µm.

Figure 3. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) micrographs, male 1. (A) entire body; (B) lateral alae starting region; (C) dorsal spiny posterior annule margins; (D) cephalic region; (E) oblique en face view of labial region; (F) precloacal thorn group; (G) tail region; (H) oblique view of spicules and postcoloacal thorn region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 30 µm; (C,E,F) = 5 µm; (D,H) = 10 µm; (G) = 20 µm. Figure 4. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., SEM micrographs, male 2. (A) entire body with an arrow indicating one of the ventral thorns; (B) cephalic region; (C) detail of the ventral thorn marked in (A); (D) precloacal region; (E) ventral view of precloacal thorn group; (F) tail region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 10 µm; (C,E) = 5 µm; (D,F) = 30 µm.

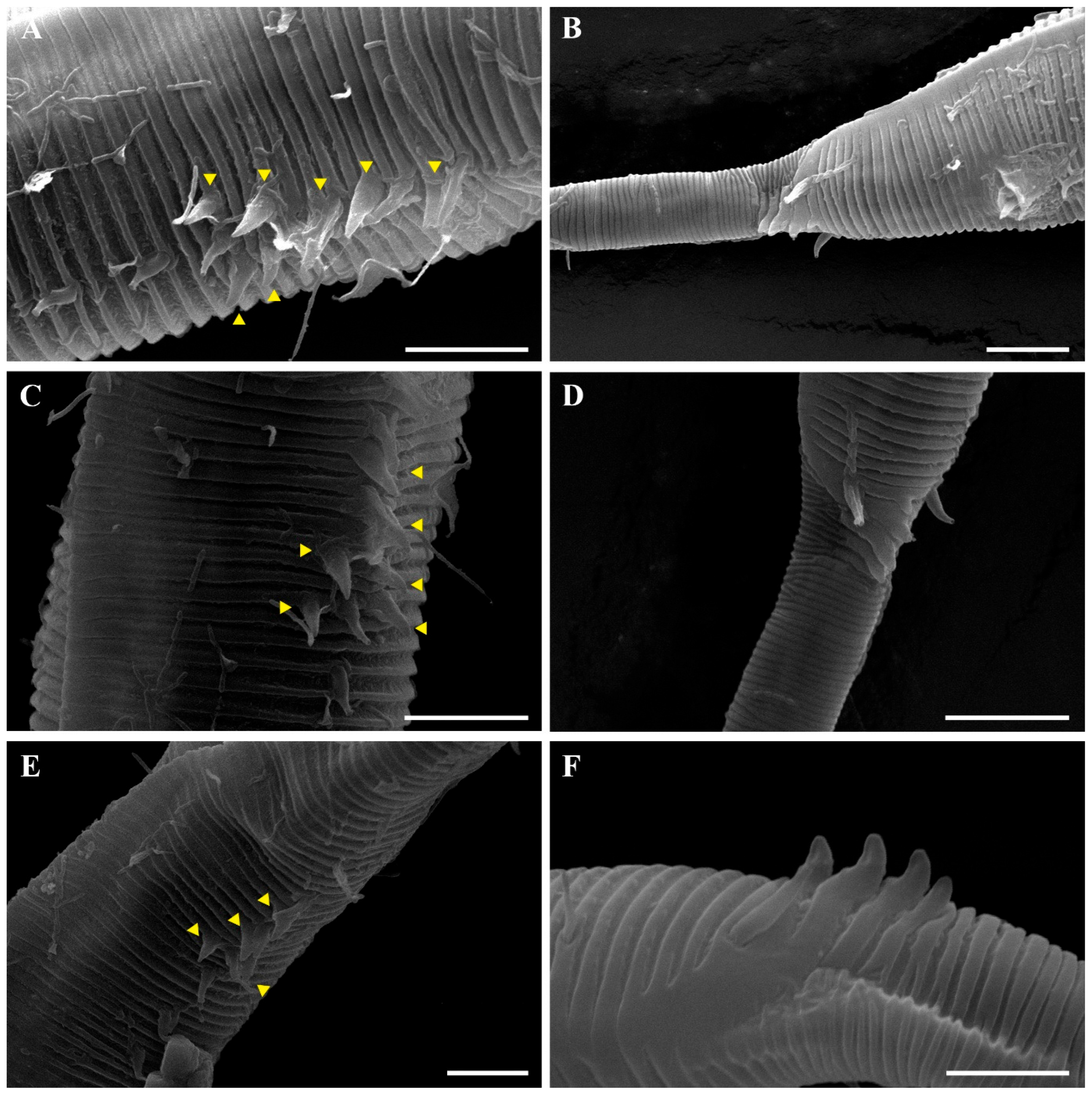

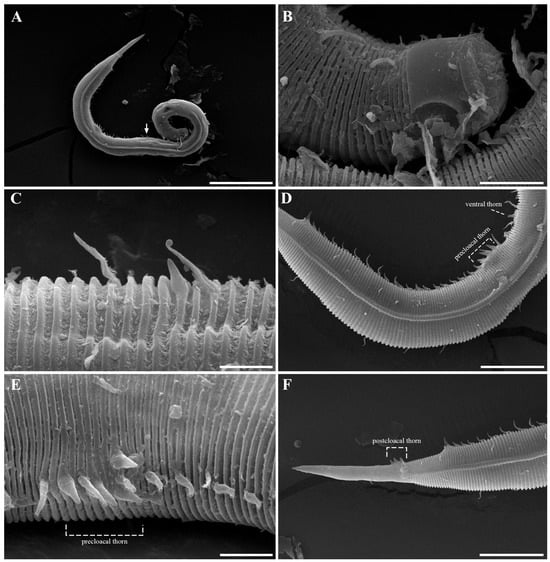

Figure 4. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., SEM micrographs, male 2. (A) entire body with an arrow indicating one of the ventral thorns; (B) cephalic region; (C) detail of the ventral thorn marked in (A); (D) precloacal region; (E) ventral view of precloacal thorn group; (F) tail region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 10 µm; (C,E) = 5 µm; (D,F) = 30 µm. Figure 5. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., SEM micrographs, variation in the male’s copulatory thorn group (yellow arrows). (A) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 3); (B) ventral view of postcloacal thorns (male 3); (C) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 4); (D) ventral view of postcloacal thorns (male 4); (E) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 5); (F) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 6). Scale bars: (A–E) = 10 µm; (F) = 5 µm.

Figure 5. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., SEM micrographs, variation in the male’s copulatory thorn group (yellow arrows). (A) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 3); (B) ventral view of postcloacal thorns (male 3); (C) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 4); (D) ventral view of postcloacal thorns (male 4); (E) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 5); (F) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 6). Scale bars: (A–E) = 10 µm; (F) = 5 µm. Figure 6. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., SEM micrographs, female 1. (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region; (C) en face view of labial region; (D) vulval region (white arrow); (E) ventral spiny posterior annule margins; (F) tail region showing anal region (white arrow). Scale bars: (A) = 200 µm; (B,D,E) = 10 µm; (C) = 5 µm; (F) = 20 µm.

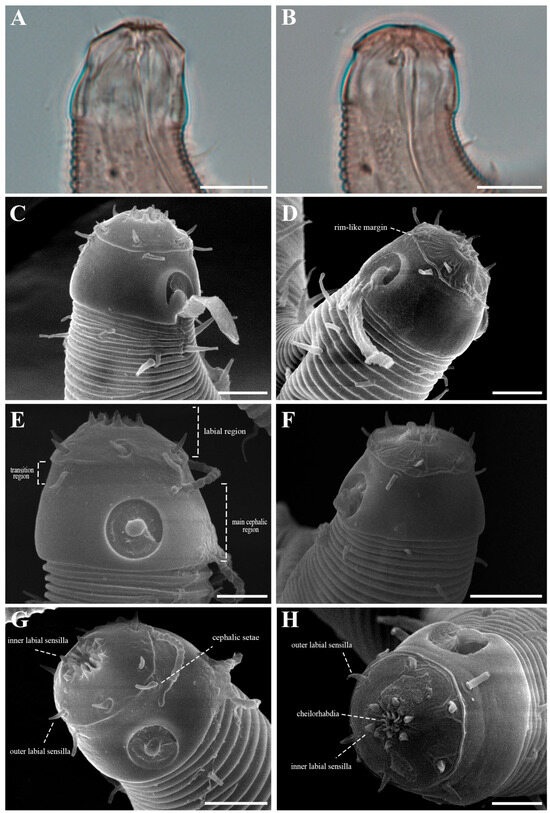

Figure 6. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., SEM micrographs, female 1. (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region; (C) en face view of labial region; (D) vulval region (white arrow); (E) ventral spiny posterior annule margins; (F) tail region showing anal region (white arrow). Scale bars: (A) = 200 µm; (B,D,E) = 10 µm; (C) = 5 µm; (F) = 20 µm. Figure 7. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and SEM micrographs. (A) lateral view of cephalic region showing protruding labial region, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2807); (B) lateral view of cephalic region with slightly contracted labial region, holotype male; (C) subdorsal view of the cephalic region showing swollen labial region (male 7); (D) Subdorsal view of the cephalic region with slightly contracted labial region showing margin of lip region (male 8); (E) lateral view of swollen labial region and a tripartite cephalic region (female 2); (F) cephalic region with slightly contracted labial region (female 3); (G) en face view of the labial region (female 02); (H) en face view of the labial region showing sensilla (male 9). Scale bars: (A–E,G,H) = 5 µm; (F) 10 µm.

Figure 7. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and SEM micrographs. (A) lateral view of cephalic region showing protruding labial region, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2807); (B) lateral view of cephalic region with slightly contracted labial region, holotype male; (C) subdorsal view of the cephalic region showing swollen labial region (male 7); (D) Subdorsal view of the cephalic region with slightly contracted labial region showing margin of lip region (male 8); (E) lateral view of swollen labial region and a tripartite cephalic region (female 2); (F) cephalic region with slightly contracted labial region (female 3); (G) en face view of the labial region (female 02); (H) en face view of the labial region showing sensilla (male 9). Scale bars: (A–E,G,H) = 5 µm; (F) 10 µm. Figure 8. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, holotype male. (A) entire body; arrows labeled d–g indicate the approximate positions of the regions shown in (D–G); (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) amphideal fovea; (D) cuticle of the posterior pharyngeal region; (E) lateral alae at midbody; (F) anteriormost ventral thorn; (G) precloacal thorn group; (H) posterior body region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–G) = 5 µm; (H) = 10 µm.

Figure 8. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, holotype male. (A) entire body; arrows labeled d–g indicate the approximate positions of the regions shown in (D–G); (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) amphideal fovea; (D) cuticle of the posterior pharyngeal region; (E) lateral alae at midbody; (F) anteriormost ventral thorn; (G) precloacal thorn group; (H) posterior body region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–G) = 5 µm; (H) = 10 µm. Figure 9. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2819). (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) cryptospiral amphideal fovea; (D) vulva region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–D) = 5 µm.

Figure 9. Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2819). (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) cryptospiral amphideal fovea; (D) vulva region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–D) = 5 µm. Table 1. Morphometric measurements of Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. (in micrometers, µm).

Table 1. Morphometric measurements of Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. (in micrometers, µm).

Diagnosis (after Verschelde et al., 2006; Mordukhovich et al., 2015; Zograf et al., 2021; Leduc, 2023; Kim & Jeong, 2025) [11,13,14,15,30].

Body short and cylindrical; cuticle transversely annulated with distinct interannular spaces. Lateral alae present, extending from the pharynx to the tail. Somatic setae are short, arranged in six or eight longitudinal rows. Cephalic region is composed of two (occasionally three) distinct parts: a slender labial region (rounded or hat-shaped), sometimes followed by a transition region with relatively thinner cuticle, and then the main capsule region with a thickened inner cuticle. A sutura may be present between the labial region and the main capsule region. Four cephalic setae situated either on the labial region or on the anterior part of the cephalic capsule. Pharynx is short and cylindrical, terminating in a bipartite or posterior bulb. Males generally possess arched spicules and a gubernaculum, and in most species copulatory thorns and postcloacal thorns are present (with a few exceptions).

Type species: Pseudochromadora quadripapillata Daday, 1899.

3.1.1. Material Examined

The holotype is an adult male (MABIK NA00158847) mounted in anhydrous glycerin on an HS slide, deposited at the Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), Seocheon, Korea. Nine paratype males (KIOST NEM-1-2807 to 2815) and four paratype females (KIOST NEM-1-2816 to 2819) are deposited at the Bio-Resources Bank of Marine Nematodes (BRBMN), East Sea Research Institute, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST), Korea.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:0CC65561-5888-4B33-AE78-709B6F1A393E

3.1.2. Type Locality and Habitat

All specimens were collected from Eulwangri Beach, Incheon, Korea (37°26′44.31″ N, 126°22′5.41″ E) on 5 September 2024. The sampling site is an intertidal flat composed of fine muddy sand and is exposed during low tide.

3.1.3. Etymology

The species epithet paraparva is derived from the Latin prefix para- meaning “near” or “resembling,” referring to the close morphological resemblance of the new species to Pseudochromadora parva.

3.1.4. Measurements

Morphometric data for the holotype and paratypes are provided in Table 1.

3.1.5. Diagnosis

Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. is diagnosed by the following combination of characters: a tripartite cephalic region composed of a jar-shaped main capsule region with thickened cuticle, an anterior transition zone with weaker cuticle bearing a crown of cephalic setae, and a high, hat-shaped labial region clearly separated from the other two parts; lateral alae 2–4 μm wide, extending from just posterior to the pharyngeal bulb to the level of the postcloacal thorns; and marked sexual dimorphism in amphideal fovea morphology—open-loop in males and unispiral or cryptospiral in females. Males are further characterized by arcuate spicules (40–48 μm long), a gubernaculum with a dorsal apophysis, a compact group of 4–7 stout precloacal thorns (anterior 2–3 thorns single and larger; posterior thorns paired and smaller), 7–10 additional ventral thorns lacking cuticular hillocks, and 3–4 medioventral postcloacal thorns.

3.1.6. Description

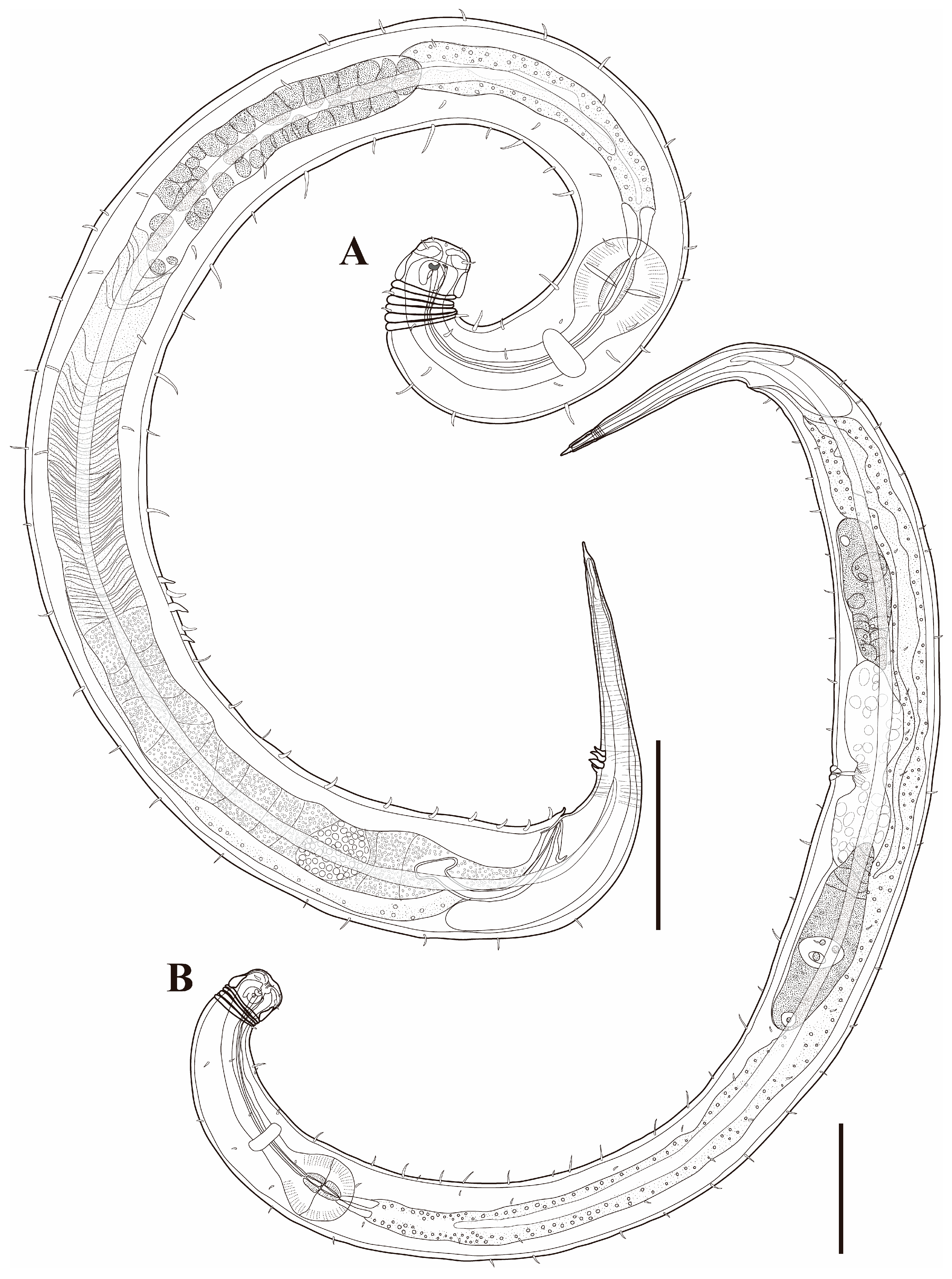

Males. The body is short and cylindrical, becoming widest at mid-body. The head is blunt, and the tail tapers into a slender conical tip (Figure 1A and Figure 8A). The cuticle is distinctly annulated beginning posterior to the head, with annuli 1–2 μm wide and separated by clear inter-annular spaces (Figure 8D). The lateral alae, 2–4 μm wide, extend from just behind the pharyngeal bulb (cardia) to the level of the postcloacal thorns (Figure 3A, Figure 4A and Figure 8E). At the level of the alae, annuli very rarely divide into two and occasionally into three rows, producing interlocking patterns (Figure 3B). The distance from the anterior end to the beginning of the alae is 116–174 μm. The posterior borders of the annules form a spiny cuticular margin, which is particularly pronounced dorsally in the posterior part of the body (Figure 3C). These spiny annular margins are not visible under light microscopy. Somatic setae are arranged in six longitudinal rows—one dorsal, one ventral, two subdorsal, and two subventral—and extend from the cephalic capsule to the tail. The dorsal setae are fewer but more regularly spaced (Figure 1A).

The cephalic region is broader than the adjacent annuli and clearly separated from the annulated body (Figure 3D and Figure 7). The cephalic region is tripartite (Figure 1C and Figure 7C,D,H). The posterior portion, referred to here as the ‘main capsule’, is a sclerotized, jar-shaped structure with a thickened cuticle. Anterior to this lies a zone with a thinner cuticle, here termed the transition zone (Figure 7E), which bears the crown of cephalic setae. The anteriormost part, the hat-shaped labial region, bears two crowns of inner and outer labial sensilla and is clearly separated from the other two parts (Figure 3E, Figure 4B and Figure 7). The labial region often appears folded inward or protruding, forming a swollen rim when contracted (Figure 7). The inner labial papillae are inconspicuous unless the labial region is extended. The outer labial sensilla measure 1–2 μm in length (Figure 7A,B).

The amphideal fovea is located on the cephalic capsule, 5–8 μm from the anterior end, and forms a large, ventrally directed open-loop aperture (Figure 1B–E and Figure 8C). Under SEM, the amphideal fovea appears as an open loop with a distinctly shorter dorsal arm (Figure 3D). The buccal cavity is strongly cuticularized and bears a crown of 12 cheilorhabdia in the cheilostome, as well as one large dorsal tooth and two smaller ventrosublateral teeth in the pharyngostome (Figure 1B,D and Figure 8B). The pharynx is cylindrical, with a slightly swollen anterior portion and a bipartite terminal bulb, comprising 21–26% of its total length. The nerve ring is located at 59–66% of pharyngeal length. The cardia is elongate and extends into the intestine (Figure 1F). Intestinal cells contain numerous lipid droplets.

The reproductive system is monorchic, with a single anterior testis located on the right side of the intestine (Figure 1A). The spicules are arcuate with a prominent capitulum. The gubernaculum bears a proximal dorsal apophysis measuring about one-third of the spicule length (Figure 1G and Figure 8H). A compact group of 4–7 stout precloacal thorns is situated 98–139 μm anterior to the cloacal opening (Figure 3F, Figure 4E and Figure 8G). The anterior 2–3 thorns are single and relatively larger, whereas the posterior thorns are paired and smaller; this pattern is consistent across individuals (Figure 5A,C,E and Figure 8G). An additional 7–10 ventral thorns extend anteriorly to the level of the lateral alae, most commonly numbering seven; in some specimens, two thorns arise from a single base (Figure 1A, Figure 4C and Figure 8F). Between the main thorn group and the cloacal opening, 14–19 ventral thorn-like setae with broad bases form a single row. The anterior and posterior somatic setae are short (3–4 μm), while the middle 4–6 setae are longer (6–8 μm) (Figure 4D).

The tail is conical and tapers posteriorly. A row of 3–4 medioventral postcloacal thorns is located 21–25 μm behind the cloacal opening (Figure 3G,H and Figure 4F). The second thorn is usually the tallest (3–4 μm), although in some specimens the first thorn may be longer (Figure 5F). The thorns arise directly from the annulated surface, where the annulation is interrupted to form a smooth cuticular patch (Figure 5F). A pair of short, broad setae (3–4 μm) flanks the postcloacal thorns (Figure 5B,D). The posterior 15–18 μm of the tail is non-annulated and ends in a narrow spinneret (Figure 1G and Figure 8H). The caudal glands extend anteriorly beyond the cloacal opening.

Females. Females are similar to males in general morphology, including cuticle annulation, lateral alae, buccal cavity, and pharyngeal structure (Figure 2, Figure 6 and Figure 9). The body is cylindrical and slightly broader in the ovarian region (Figure 2A, Figure 6A and Figure 9A). The posterior borders of the annules form a spiny cuticular margin dorsally, and the spines are occasionally visible ventrally (Figure 6E). The amphideal fovea are unispiral or cryptospiral (Figure 6C and Figure 7E), positioned slightly more posteriorly on the third region of the cephalic capsule (Figure 6C and Figure 9C). The reproductive system is didelphic–amphidelphic, with both ovaries reflexed and positioned on the right side of the intestine. The vulva is small and slit-like, located at approximately two-thirds of the body length from the anterior end (Figure 6D and Figure 9D).

3.1.7. Differential Diagnosis

To facilitate comparisons among species of Pseudochromadora, the major diagnostic characters of the genus are summarized in Table 2. All species-level information was compiled from the original descriptions; for P. benepapillata, data were integrated from the revision by Datta et al. (2018) and the original description by Timm (1961), while information for P. quadripapillata was derived from Coomans et al. (1985) [31,32,33].

Table 2.

Comparative matrix of diagnostic morphological characters for the 19 valid species of Pseudochromadora, including the two new species described in this study. Morphometric Values are rounded. The presence of a character is indicated by ‘+’, absence by ‘–’, and unknown data by ‘n.a.’.

Among congeners, ventral thorns have been reported in P. buccobulbosa Verschelde & Vincx, 1995, P. cazca Gerlach, 1956, P. interdigitata Muthumbi, Verschelde & Vincx, 1995, P. parva Gagarin & Thanh, 2008, and P. rossica Mordukhovich et al., 2015 [15,34,35,36,37]. Of these, P. buccobulbosa and P. interdigitata are easily distinguished from the new species by their rounded labial region and straight gubernaculum. Pseudochromadora buccobulbosa also possesses more than 20 precloacal thorns arranged in multiple rows, whereas the new species has only 4–7 thorns forming a single compact group. Pseudochromadora interdigitata exhibits completely interdigitating lateral alae with annuli divided into four distinct branches; in contrast, the new species shows only localized bifurcation of annuli into two or three branches, forming a partial interdigitation pattern.

Pseudochromadora cazca differs from the new species by having a rounded labial region, spiral amphideal fovea in males, more numerous postcloacal thorns, and a straight gubernaculum. Pseudochromadora rossica, described from the Sea of Japan (East Sea), is geographically proximate to the type locality of the new species. However, it can be clearly differentiated by its rounded labial region, straight gubernaculum without dorsal apophysis, and lack of sexual dimorphism in amphideal fovea structure.

The most morphologically similar species is P. parva, originally described from fine muddy sediments (1–2 m depth) of the Red River estuary, Vietnam. It was later redescribed by Zograf et al. (2021) [30] based on specimens from Thi Nai Lagoon, including detailed DIC and SEM imagery. A comparative analysis between P. paraparva sp. nov. and P. parva reveals several key differences. Males of the new species are significantly larger (630–750 μm vs. 400–531 μm), as are females (650–710 μm vs. 399–477 μm). Spicules are longer in the new species (40–48 μm vs. 28–31 μm), and the gubernaculum-to-spicule ratio is lower (27–34% vs. 45–50%). Tail-to-body length ratios are also greater in P. paraparva (7.9–9.0 vs. 4.8–6.6).

Additional morphological distinctions further separate the two species. In P. parva, the labial region is greatly elongate and retracts to cover the anterior cephalic capsule. In P. paraparva sp. nov., the labial margin remains exposed even when retracted, forming a distinct, rim-like edge. In lateral view, main capsule region is swollen, producing a characteristic jar-shaped appearance. When everted, the labial region forms a high, rounded, hat-like structure—a feature absent from the original description of P. parva.

Another notable distinction involves the structure and arrangement of ventral thorns. In P. parva, ventral thorns are surrounded by eight conspicuous cuticular hillocks, clearly visible in the SEM images of Zograf et al. (2021) [30]. In contrast, P. paraparva sp. nov. lacks these hillocks around the ventral thorns, which instead arise directly from the striated cuticle. Only the precloacal thorn group may exhibit faint hillock-like swellings in some specimens. The arrangement of the precloacal thorn group also differs markedly. In most previously described species examined under SEM—including P. rossica, P. galeata, and P. securis—the precloacal thorns number 8–20 and are arranged in multiple irregular rows. By contrast, P. paraparva sp. nov. consistently displays a compact, single group of 4–7 precloacal thorns, with the anterior thorns larger and unpaired, and the posterior thorns smaller and arranged in pairs.

The original description of P. parva lacks detailed information on thorn height, distance from the cloacal opening to the thorn group, and thorn arrangement, limiting direct comparison. However, DIC images provided by Zograf et al. (2021) [30] clearly illustrate differences in size, shape, and spacing of thorns relative to the new species. Taken together, these morphological distinctions—particularly in cephalic structure, thorn arrangement, body and spicules size—support the recognition of P. paraparva sp. nov. as a distinct species closely related to, but clearly separable from, P. parva.

3.2. Morphological Analysis of Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov.

- Family Desmodoridae Filipjev, 1922

- Subfamily Desmodorinae Filipjev, 1922

- Genus Pseudochromadora Daday, 1899

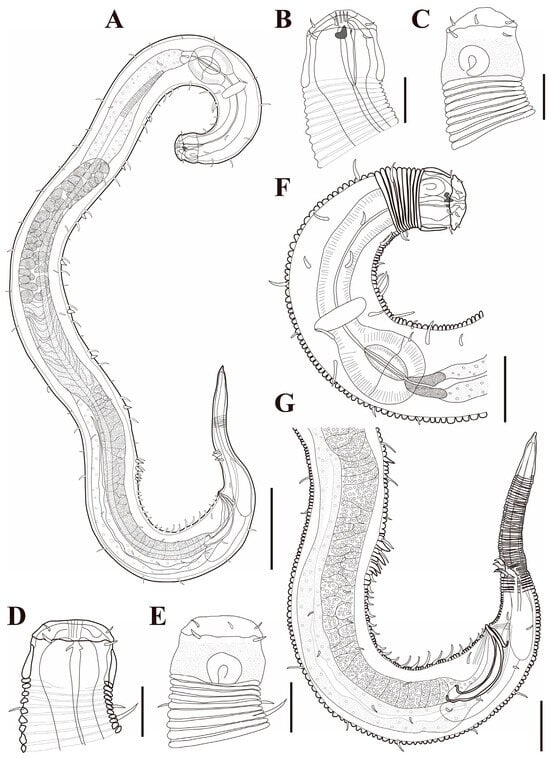

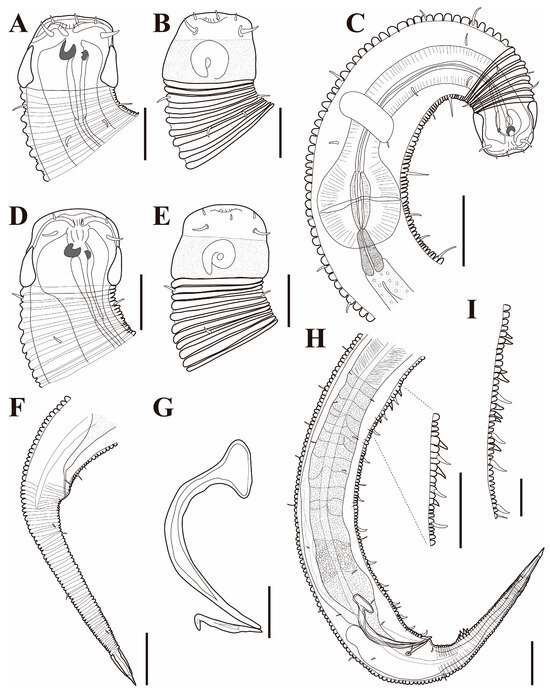

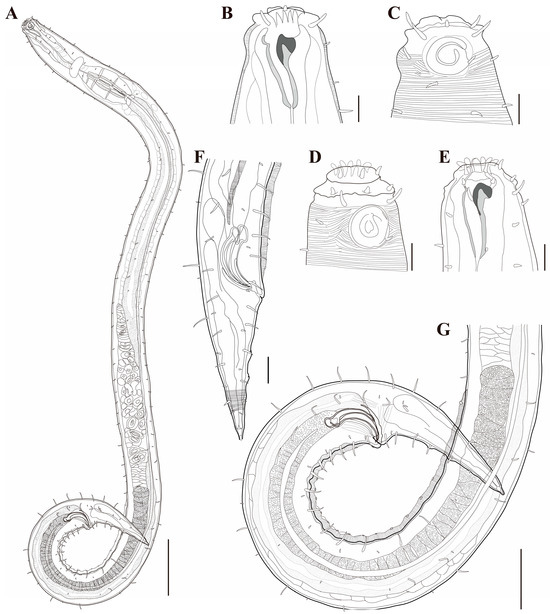

- Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, Table 3)

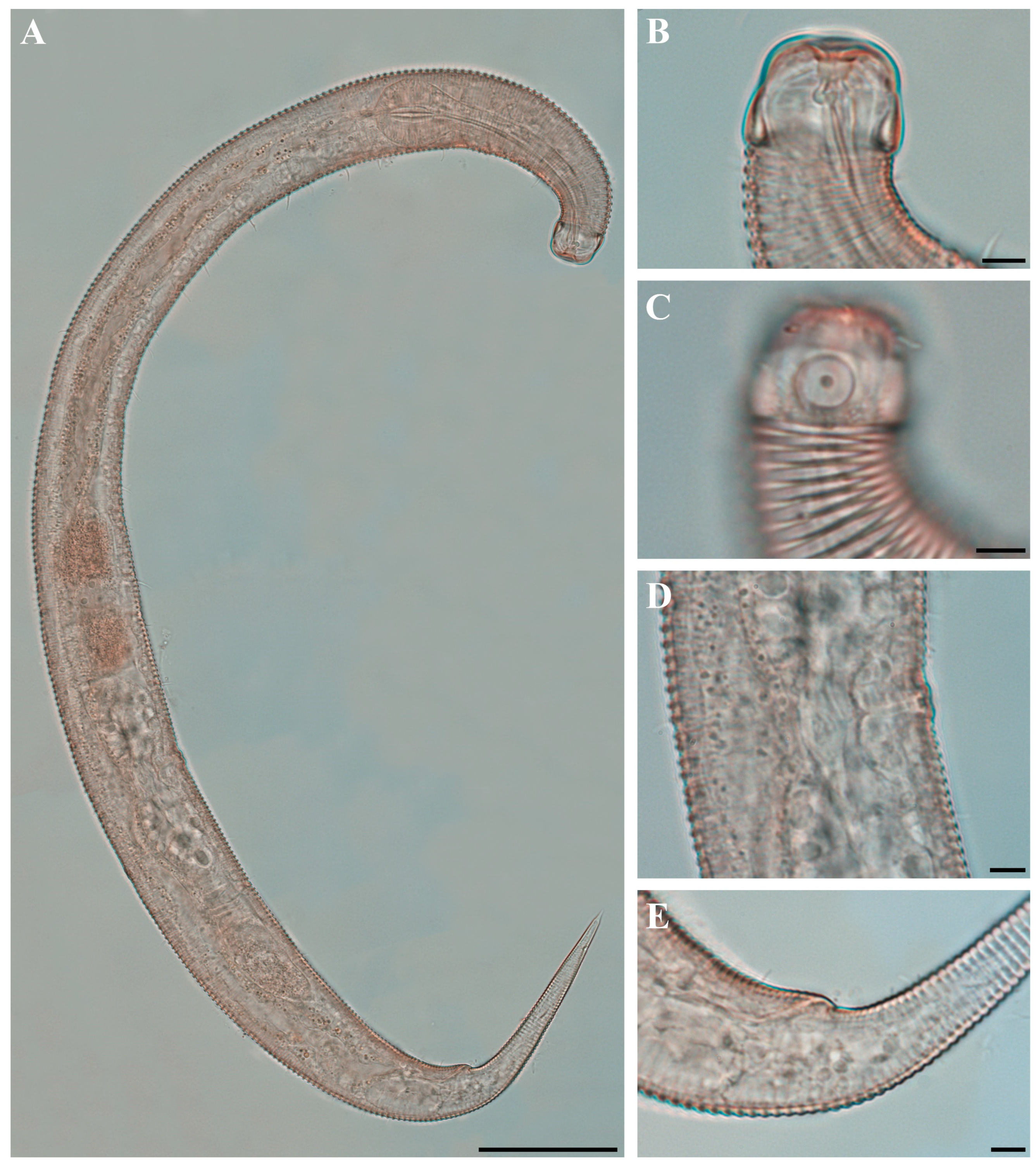

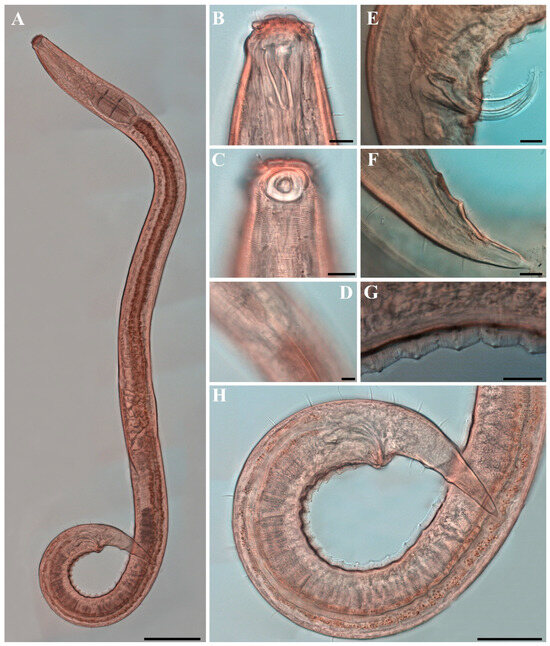

Figure 10. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. (A) entire body, holotype male; (B) entire body, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2848). Scale bars = 50 µm.

Figure 10. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. (A) entire body, holotype male; (B) entire body, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2848). Scale bars = 50 µm. Figure 11. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., (A–C,H) holotype male; (D–F) paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2848); (G,I) paratype males. (A) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section; (B) external view of cephalic region; (C) anterior region; (D) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section; (E) external view of cephalic region; (F) tail region; (G) spicules and gubernaculum (KIOST NEM-1-2846); (H) posterior body region showing precloacal thorn group; (I) precloacal thorn group (KIOST NEM-1-2839). Scale bars: (A,B,D,E,G,I) = 10 µm; (C,F,H) = 20 µm.

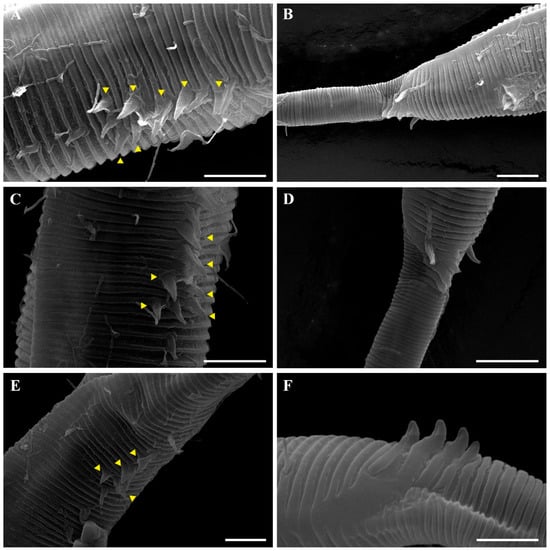

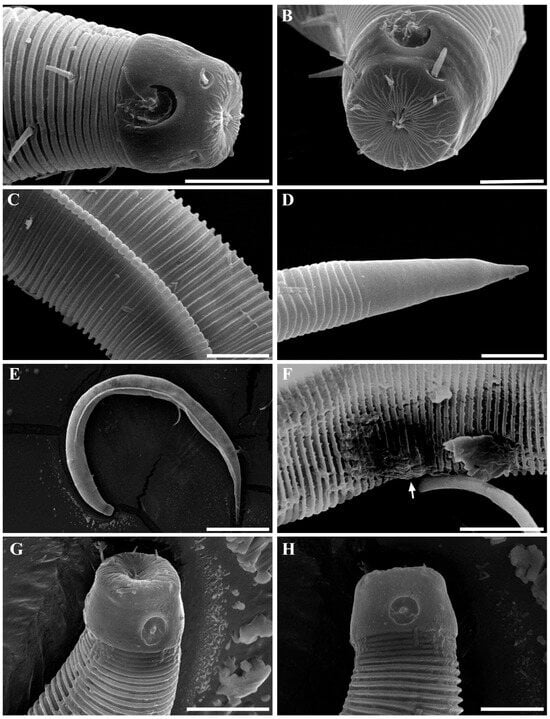

Figure 11. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., (A–C,H) holotype male; (D–F) paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2848); (G,I) paratype males. (A) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section; (B) external view of cephalic region; (C) anterior region; (D) lateral view of anterior body region showing buccal cavity and armature in optical section; (E) external view of cephalic region; (F) tail region; (G) spicules and gubernaculum (KIOST NEM-1-2846); (H) posterior body region showing precloacal thorn group; (I) precloacal thorn group (KIOST NEM-1-2839). Scale bars: (A,B,D,E,G,I) = 10 µm; (C,F,H) = 20 µm. Figure 12. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., SEM micrographs, male 1. (A) entire body; (B) lateral alae starting region; (C) cephalic region; (D) en face view of labial region; (E) posterior body region; (F) ventral view of cloacal opening; (G) precloacal thorn group; (H) tail region; (I) postcloacal thorn region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 15 µm; (C,D) = 5 µm; (E) = 50 µm; (F,G,I) = 10 µm; (H) = 30 µm.

Figure 12. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., SEM micrographs, male 1. (A) entire body; (B) lateral alae starting region; (C) cephalic region; (D) en face view of labial region; (E) posterior body region; (F) ventral view of cloacal opening; (G) precloacal thorn group; (H) tail region; (I) postcloacal thorn region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 15 µm; (C,D) = 5 µm; (E) = 50 µm; (F,G,I) = 10 µm; (H) = 30 µm. Figure 13. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., SEM micrographs. (A) head region showing amphideal fovea, male 2; (B) en face view of labial region, male 2; (C) lateral alae, male 3; (D) tail of non-annulated region, male 3; (E) entire body, female 1; (F) vulva region (white arrow), female 1; (G) labial region, female 1; (H) head region showing amphideal fovea, female 1. Scale bars: (A,C,F–H) = 10 µm; (B,D) = 5 µm; (E) = 100 µm.

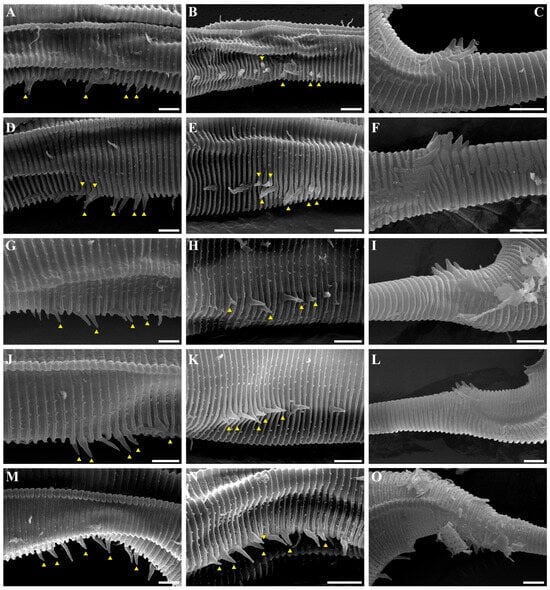

Figure 13. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., SEM micrographs. (A) head region showing amphideal fovea, male 2; (B) en face view of labial region, male 2; (C) lateral alae, male 3; (D) tail of non-annulated region, male 3; (E) entire body, female 1; (F) vulva region (white arrow), female 1; (G) labial region, female 1; (H) head region showing amphideal fovea, female 1. Scale bars: (A,C,F–H) = 10 µm; (B,D) = 5 µm; (E) = 100 µm. Figure 14. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., SEM micrographs, variation in the male’s copulatory thorn group (yellow arrows). (A) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 2); (B) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 2); (C) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 2); (D) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 3); (E) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 3); (F) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 3); (G) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 4); (H) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 4); (I) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 4); (J) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 5); (K) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 5); (L) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 5); (M) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 6); (N) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 6); (O) lateral view of postcloacal thorn (male 6). Scale bars: 5 µm.

Figure 14. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., SEM micrographs, variation in the male’s copulatory thorn group (yellow arrows). (A) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 2); (B) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 2); (C) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 2); (D) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 3); (E) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 3); (F) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 3); (G) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 4); (H) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 4); (I) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 4); (J) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 5); (K) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 5); (L) lateral view of postcloacal thorns (male 5); (M) lateral view of precloacal thorn group (male 6); (N) ventral view of precloacal thorn group (male 6); (O) lateral view of postcloacal thorn (male 6). Scale bars: 5 µm. Figure 15. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, (A–G) holotype male; (H–K) paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2846). (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) amphideal fovea; (D) spicules and gubernaculum; (E) lateral alae; (F) posterior body region; (G) precloacal thorn group; (H) cephalic region showing dorsal teeth; (I) amphideal fovea; (J) precloacal thorn group; (K) spicules and gubernaculum. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–K) = 10 µm.

Figure 15. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, (A–G) holotype male; (H–K) paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2846). (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) amphideal fovea; (D) spicules and gubernaculum; (E) lateral alae; (F) posterior body region; (G) precloacal thorn group; (H) cephalic region showing dorsal teeth; (I) amphideal fovea; (J) precloacal thorn group; (K) spicules and gubernaculum. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–K) = 10 µm. Figure 16. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2848). (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) amphideal fovea; (D) vulva region; (E) anal region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–E) = 5 µm.

Figure 16. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov., DIC photomicrographs, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2848). (A) entire body; (B) cephalic region in optical section; (C) amphideal fovea; (D) vulva region; (E) anal region. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–E) = 5 µm. Table 3. Morphometric measurements of Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. in micrometers (µm).

Table 3. Morphometric measurements of Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. in micrometers (µm).

3.2.1. Material Examined

The holotype is an adult male (MABIK NA00158849) mounted in anhydrous glycerin on an HS slide and deposited at the Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), Seocheon, Korea. Eleven paratype males (KIOST NEM-1-2836 to 2846) and three paratype females (KIOST NEM-1-2847 to 2849) are deposited at the nematode specimen repository of the Bio-Resources Bank of Marine Nematodes (BRBMN), East Sea Research Institute, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST), Korea.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:9231A69C-BF60-49B6-8B11-90E663BBA180

3.2.2. Type Locality and Habitat

All specimens were collected from subtidal muddy sediments at Site 4 off Jindo Island, Korea (34°25′24.83″ N, 126°22′33.04″ E) on 20 May 2025, using a van Veen grab sampler at a depth of 5 m. The sediment was primarily composed of fine mud with moderate organic content. Environmental parameters at the time of sampling included a bottom-water temperature of 17.0–17.4 °C and salinity of 33‰.

3.2.3. Etymology

The species epithet capitata is derived from the Latin adjective capitatus, meaning “having a head” or “knobbed,” referring to the conspicuously enlarged capitulum of the spicule.

3.2.4. Measurements

Morphometric data for the holotype and paratypes are presented in Table 3.

3.2.5. Diagnosis

Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. is distinguished by a cephalic region divided into two parts: a short anterior labial region and a thickly cuticularized main capsule region. The species exhibits sexual dimorphism in amphideal fovea structure: males possess an open-loop type, while females have a unispiral type. Spicules are arcuate, featuring a relatively large, hammer-shaped capitulum, and the gubernaculum is equipped with a prominent dorsal apophysis. Males bear a group of 3–8 ventral precloacal thorns arranged in a longitudinal row and 3–5 medioventral postcloacal thorns.

3.2.6. Description

Males. The body is short and cylindrical, with its broadest region located at mid-body. The head is blunt, and the tail tapers into a slender conical tip (Figure 10A, Figure 12A and Figure 15A). The cuticle is annulated from just behind the cephalic capsule, with annuli 1–2 μm wide and distinctly separated by narrow inter-annular spaces (Figure 13A). The lateral alae, 2–4 μm wide, begin immediately posterior to the pharyngeal bulb and extend to the level of the postcloacal thorns (Figure 12A,B, Figure 13C and Figure 15E). The distance from the pharynx terminus to the start of the alae is 17–34 μm. The posterior borders of the annules form a spiny cuticular margin that is clearly visible dorsally and ventrally under SEM, especially in the posterior body region (Figure 12G), although this margin is not discernible under light microscopy. Where the spiny ornamentation becomes densely developed, the lateral alae lack spines but display a slightly serrated margin (Figure 14M). Somatic setae occur in six longitudinal rows—one dorsal, one ventral, two subdorsal, and two subventral—extending from the cephalic capsule to the tail; dorsal setae are fewer but more regularly spaced than ventral ones.

The cephalic capsule is well developed and clearly separated from the annulated body (Figure 12C). The cephalic region consists of two parts: an anterior labial region and a posterior main capsule region with thickened cuticle. The labial region bears six inner and six outer labial sensilla, and four cephalic setae are inserted just anterior to the transverse sutura that demarcates the labial region from the main capsule. In SEM images, the labial region appears retracted, the oral opening is closed, and fine folds form around the lip margin (Figure 12D and Figure 13B). The main capsule is broader than the labial region, strongly cuticularized (Figure 11A and Figure 15B), and ornamented with numerous minute vacuoles under DIC microscopy (Figure 15C); no additional setae are present. Inner labial sensilla are inconspicuous unless the labial region is extended. The outer labial setiform sensilla measure 1–2 μm in length. The amphideal fovea is positioned laterally on the cephalic capsule, 4–8 μm from the anterior end, forming a large, ventrally directed open-loop aperture (Figure 11B and Figure 15I). Under SEM, the amphideal fovea appears as an open loop with a distinctly shorter dorsal arm (Figure 12C and Figure 13A).

The buccal cavity is strongly cuticularized and contains a prominent dorsal tooth and two smaller ventrosublateral teeth in the pharyngostome (Figure 11A and Figure 15B,H). The pharynx is cylindrical and ends in a bipartite terminal bulb comprising 24–27% of total pharyngeal length. The nerve ring is located at 48–60% of pharyngeal length. The cardia is elongate and extends into the intestine (Figure 11C). Intestinal cells contain numerous lipid droplets.

The reproductive system is monorchic, with a single anterior testis extending alongside and positioned on the right side of the intestine (Figure 10A). The cloacal opening is slightly protruded, and the cuticle is smooth (Figure 12F). The spicules are arcuate, with a relatively large hammer-shaped capitulum measuring 8–12 μm in width and 3–4 μm in thickness (Figure 11G and Figure 15D,K). The gubernaculum bears a proximal dorsal apophysis measuring about one-third of the spicule length (Figure 11G and Figure 15K). A compact group of 3–8 stout ventral precloacal thorns is located 129–156 μm anterior to the cloacal opening; the tallest thorn reaches 3–4 μm (Figure 11H,I, Figure 12G and Figure 15G,J). Under SEM, the thorns appear mainly in a single longitudinal row, although paired thorns occur in some individuals (Figure 14). Between the precloacal thorns and the cloacal opening, 10–12 ventral thorn-like setae with broad bases form a single row (Figure 11H, Figure 12E and Figure 15F); one or two setae lie within the precloacal thorn group.

The tail is conical and tapers posteriorly, carrying 3–5 medioventral postcloacal thorns located 11–23 μm behind the cloacal opening (Figure 12H,I and Figure 15D). In most specimens, these thorns occur in a single row, although paired thorns may occur (Figure 14); the longest thorn measures 2–3 μm. The thorns arise directly from the cuticle, with the surrounding annuli interrupted to produce a smooth patch (Figure 12I). A pair of short, broad lateral setae flanks the postcloacal thorns. The distal 13–17 μm of the tail is non-annulated and terminates in a narrow spinneret (Figure 13D).

Females. Females resemble males in overall morphology, including cuticle annulation, lateral alae, buccal cavity, and pharyngeal structure (Figure 10B, Figure 11D–F, Figure 13E,F and Figure 16). The body is cylindrical and slightly wider in the ovarian region. The amphideal fovea is unispiral and positioned on the cephalic capsule (Figure 11E, Figure 13G,H and Figure 16C). The reproductive system is didelphic–amphidelphic, with reflexed ovaries on the right side of the intestine. The vulva is small and slit-like, located at about three-fifths of the body length from the anterior end (Figure 13F and Figure 16D). The pars distalis vaginae is cuticularized, and the pars proximalis vaginae is surrounded by a constrictor muscle. Copulatory and postcloacal thorns are absent (Figure 11F and Figure 16E).

3.2.7. Differential Diagnosis

Within the genus Pseudochromadora, the shape of the labial region is a key diagnostic character, broadly categorized as either hat-shaped or rounded. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. exhibits a rounded labial region, a condition also reported in nine congeners: P. buccobulbosa Verschelde & Vincx, 1995; P. cazca Gerlach, 1956; P. coomansi Verschelde & Vincx, 1995; P. incubans Gourbault & Vincx, 1990; P. interdigitatum Muthumbi, Verschelde & Vincx, 1995; P. plurichela Leduc & Zhao, 2023; P. reathae Leduc & Wharton, 2010; and P. rossica Mordukhovich et al., 2015; P. typica Kim & Jeong, 2025 [13,14,15,34,35,36,38].

Among these, only three species—P. coomansi, P. incubans, and P. typica—lack both ventral thorns and precloacal supplements, as in P. capitata sp. nov. Pseudochromadora coomansi possesses unispiral amphideal fovea without sexual dimorphism and spicules with a funnel-shaped proximal part, lacking a capitulum. In addition, it features interdigitating, split lateral alae—absent in P. capitata sp. nov. Similarly, P. incubans differs in having eight longitudinal rows of somatic setae, cryptospiral amphideal fovea with no sexual dimorphism, and a differently shaped spicule capitulum and gubernaculum.

Among the rounded labial region congeners, P. capitata sp. nov. most closely resembles P. typica Kim & Jeong, 2025. Both species exhibit sexual dimorphism in amphideal fovea structure—loop-shaped in males and unispiral in females in P. capitata sp. nov., versus unispiral in males and cryptospiral in females in P. typica—and both possess precloacal and postcloacal thorns. However, P. capitata sp. nov. differs from P. typica in several key aspects: it has fewer precloacal thorns (3–8 vs. 8–10), which are arranged in a single longitudinal row rather than in two discrete groups; lacks a ventral cuticular hump bearing anterior thorns; and possesses a gubernaculum with a dorsal apophysis. The spicules of P. capitata sp. nov. are robust and arcuate, with a large, broad capitulum (8–12 µm wide, 3–4 µm thick) nearly as wide as the gubernaculum, whereas those of P. typica are comparatively narrower and have a smaller capitulum.

Although both species were collected from Korean coastal waters, their habitats differ. P. typica was recorded from intertidal sandy sediments along the western coast (Incheon area), while P. capitata sp. nov. was found in subtidal muddy sediments at approximately 5 m depth off Jindo Island on the southern coast. These differences in geographic location and sediment type may reflect ecological influences contributing to morphological divergence between the two taxa.

In addition, P. capitata sp. nov. shows some similarity to P. thinaiica Zograf et al., 2021 in certain male copulatory systems, such as the large capitulum on the spicules and a gubernaculum with dorsal apophysis. However, the two species differ fundamentally in several diagnostic characters. P. capitata sp. nov. possesses a rounded labial region, whereas P. thinaiica is characterized by a distinctly hat-shaped labial region. The amphideal fovea structure also differs considerably: P. capitata sp. nov. shows sexual dimorphism—loop-shaped in males and unispiral in females—whereas P. thinaiica has cryptospiral amphideal fovea in both sexes. In addition, the ventral cuticular hump bearing precloacal thorn group, a characteristic feature of P. thinaiica, is absent in P. capitata sp. nov. These consistent morphological differences clearly separate the two taxa and support the recognition of P. capitata sp. nov. as a distinct species. These consistent differences clearly distinguish the two taxa and support the recognition of P. capitata sp. nov. as a distinct species.

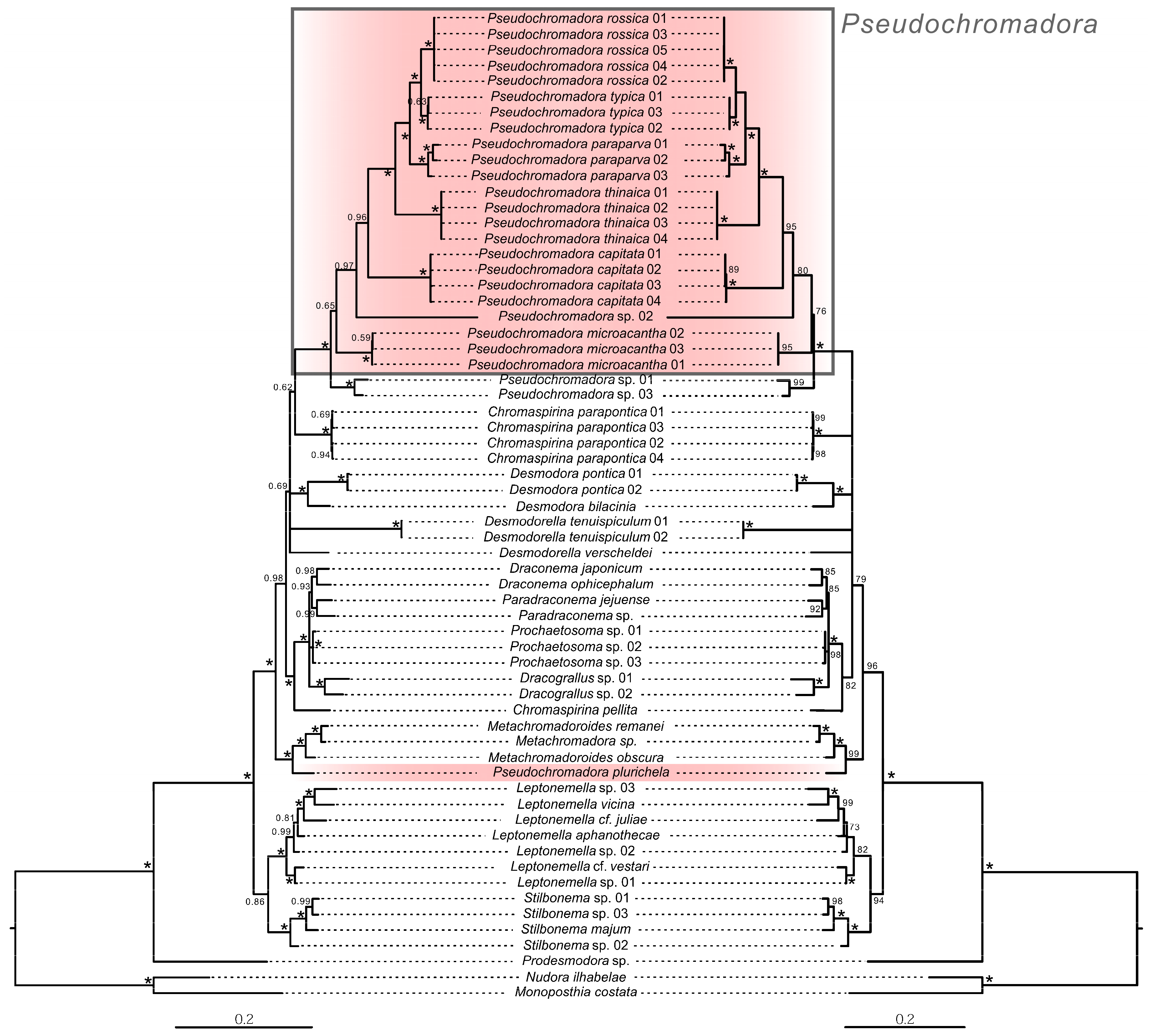

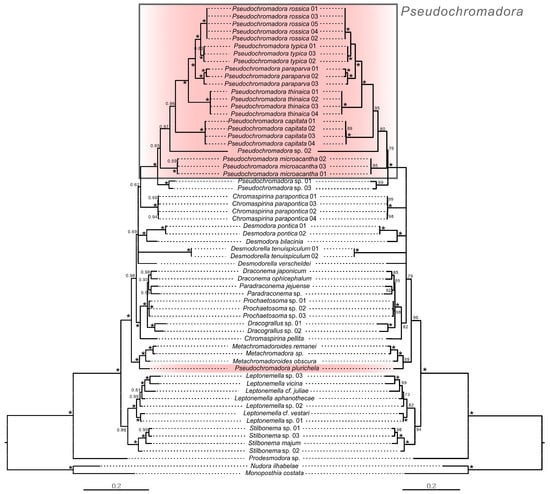

3.3. Molecular Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships (Figure 17)

Figure 17.

Phylogenetic relationships within the genus Pseudochromadora based on concatenated 18S + 28S sequences, with Nudora ilhabelae and Monoposthia costata as outgroups. Left: Bayesian inference tree; node values represent posterior probabilities (PP). Right: Maximum Likelihood tree; node values represent bootstrap supports (BS). Asterisks (*) indicate PP = 1.0 or BS = 100. Scale bar denotes substitutions per nucleotide position. GenBank accession numbers for all reference sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Partial 18S and 28S rRNA sequences of Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. and P. capitata sp. nov. were successfully obtained. Phylogenetic analyses based on Maximum Likelihood (ML), Bayesian inference (BI), and concatenated 18S + 28S datasets consistently placed both new species within the genus Pseudochromadora, revealing clear patterns of interspecific divergence and lineage structuring within the genus.

3.3.1. Phylogenetic Placement Within Pseudochromadora

In all analyses, P. paraparva sp. nov. and P. capitata sp. nov. formed strongly supported monophyletic clades (PP = 1.0; BS = 99–100). Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. was consistently recovered as the sister species to P. rossica and P. typica. In contrast, P. capitata sp. nov. was positioned at the base of the clade containing (P. paraparva sp. nov. + (P. typica + P. rossica)) and P. thinaica, forming a distinct sister lineage. This placement indicates a deeper divergence and strongly supports its status as an independent species-level taxon.

3.3.2. Integrated P-Distance Patterns of 18S and 28S rDNA

Analyses of both 18S and 28S rDNA sequences revealed consistent patterns of genetic divergence among Pseudochromadora species and strongly supported the distinct species-level status of P. paraparva sp. nov. and P. capitata sp. nov. In the 18S dataset, P. paraparva sp. nov. showed very low intraspecific variation (0.7–0.9%), confirming genetic cohesion among individuals. Its closest relative was P. typica (2.5–2.8% divergence), while more distant congeners, such as P. thinaica (4.2–4.3%) and P. microacantha (7.4–7.7%), exhibited substantially higher divergence values. All Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. sequences formed a stable, well-supported monophyletic cluster adjacent to P. typica. Pseudochromadora capitata sp. nov. also exhibited very low intraspecific variation (0.1%). In contrast, interspecific divergences were substantially higher, ranging from 6.02 to 6.03% when compared with P. thinaica, 5.6–5.7% with P. typica, and 6.4–6.5% with P. microacantha. The 28S rDNA dataset displayed a comparable divergence pattern. The closest relatives of Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. were P. typica (9.4% divergence), P. rossica (9.6%) and P. thinaica (17.3%), followed by P. microacantha (21.8%). The divergence between P. paraparva sp. nov. and P. capitata sp. nov. reached 23.5–23.7%, indicating substantial genetic differentiation between the two new species. For P. capitata sp. nov., intraspecific divergence remained extremely low (0.4%), while interspecific comparisons yielded high divergence values, including 23.2–23.5% from P. thinaica, 21.7–22.3% from P. rossica 21.9–22.7% from P. typica, and 21.9–22.5% from P. microacantha. Taken together, the consistently low intraspecific variation and high interspecific divergence across both genetic markers provide strong molecular support for recognizing P. paraparva sp. nov. and P. capitata sp. nov. as valid, distinct species within Pseudochromadora.

3.3.3. Morphological Correlation and Lineage-Specific Traits

The distinct phylogenetic position of P. microacantha corresponds well with its unique morphological characteristics. In all molecular analyses (ML, BI, and concatenated datasets), P. microacantha consistently formed a deeply divergent lineage within Pseudochromadora, showing the highest interspecific genetic distances from the two new species, P. paraparva sp. nov. (7.4–7.7% for 18S; 22% for 28S) and P. capitata sp. nov. (6.4–6.5% for 18S; 22–23% for 28S). This pronounced molecular divergence parallels its distinctive morphology. Most notably, the male precloacal thorn group in P. microacantha is positioned immediately anterior to the cloacal opening, whereas in all examined congeners—including P. typica, P. thinaica, P. paraparva sp. nov., and P. capitata sp. nov.—the same structure is situated farther anteriorly along the body. This positional shift represents a clear deviation from the generic pattern and may reflect a lineage-specific morphological adaptation unique to P. microacantha. The congruence between molecular distinctiveness and this diagnostic morphological trait strongly supports the interpretation that P. microacantha represents an evolutionarily isolated lineage within the genus.

3.3.4. Anomalous Placement of Pseudochromadora plurichela

In all analyses—including the 18S, 28S, and concatenated datasets—P. plurichela did not cluster with other Pseudochromadora species. Instead, it grouped with Metachromadora and Metachromadoroides, forming a lineage entirely separate from the well-supported Pseudochromadora clade. This repeated pattern suggests several possibilities: (1) the species may have been misidentified in its original description; (2) it may retain plesiomorphic traits uncharacteristic of the genus; or (3) it may have been incorrectly assigned to Pseudochromadora at the time of description. Given the consistency of the molecular signal across all datasets, misidentification appears to be the most plausible explanation.

3.4. Morphological Analysis of Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978

- Subfamily Spiriniinae Chitwood, 1936

- Genus Metachromadora Filipjev, 1918

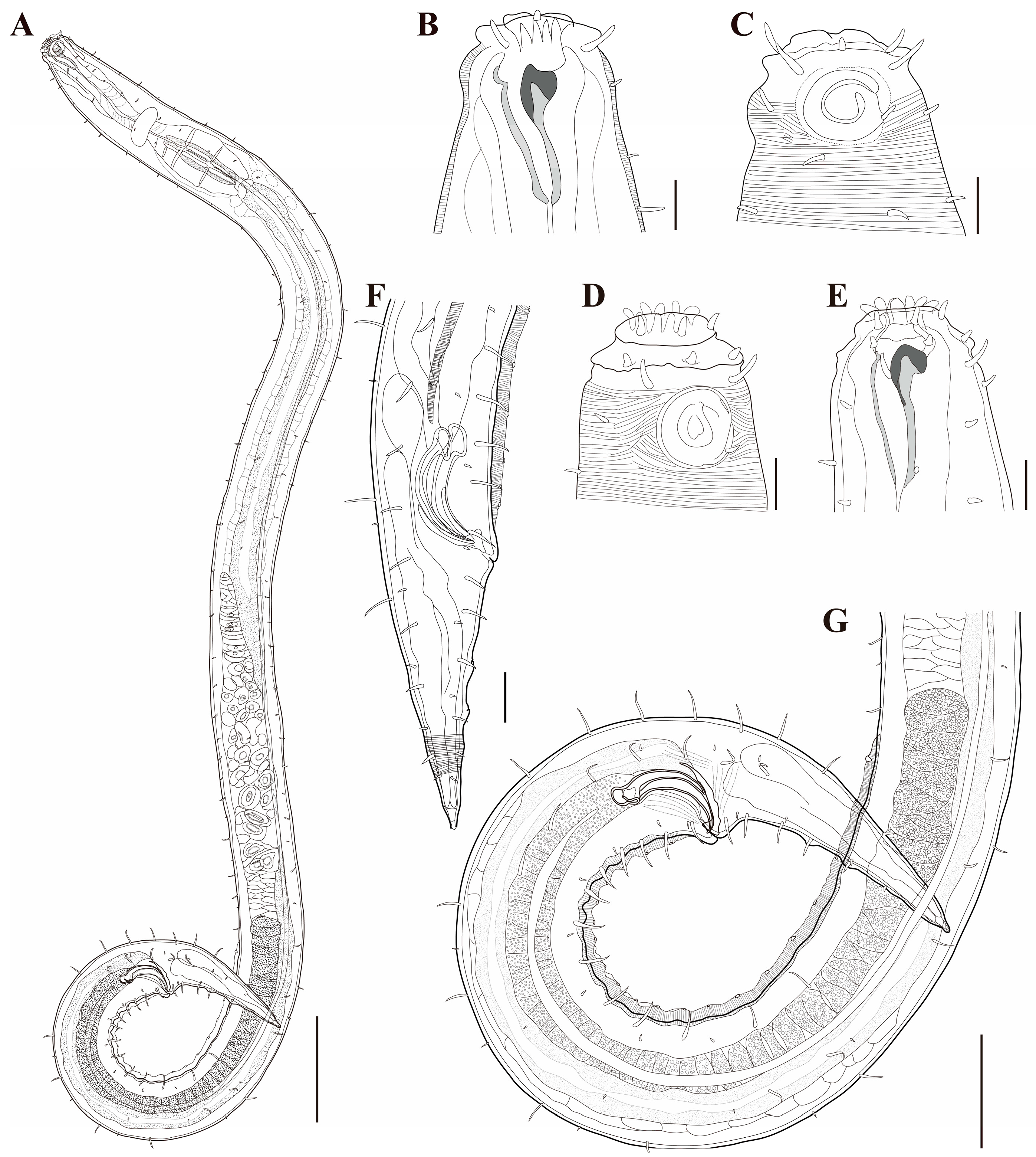

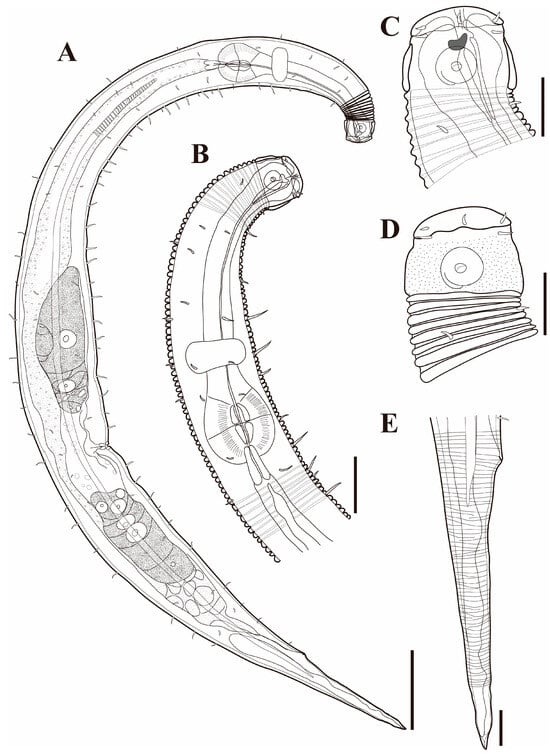

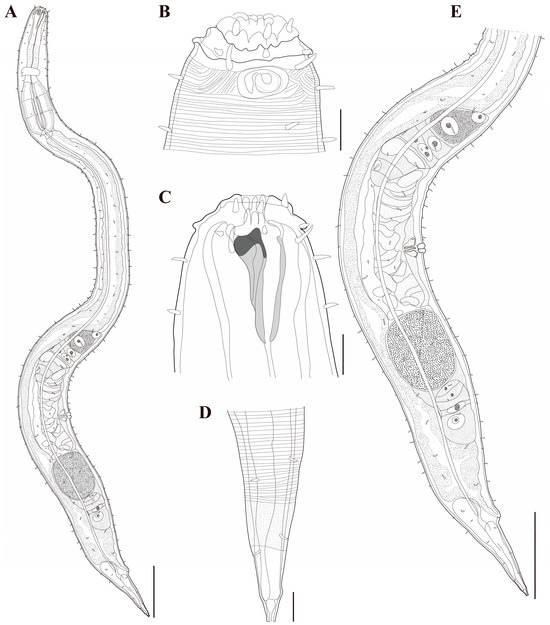

- Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978 (Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23, Table 4)

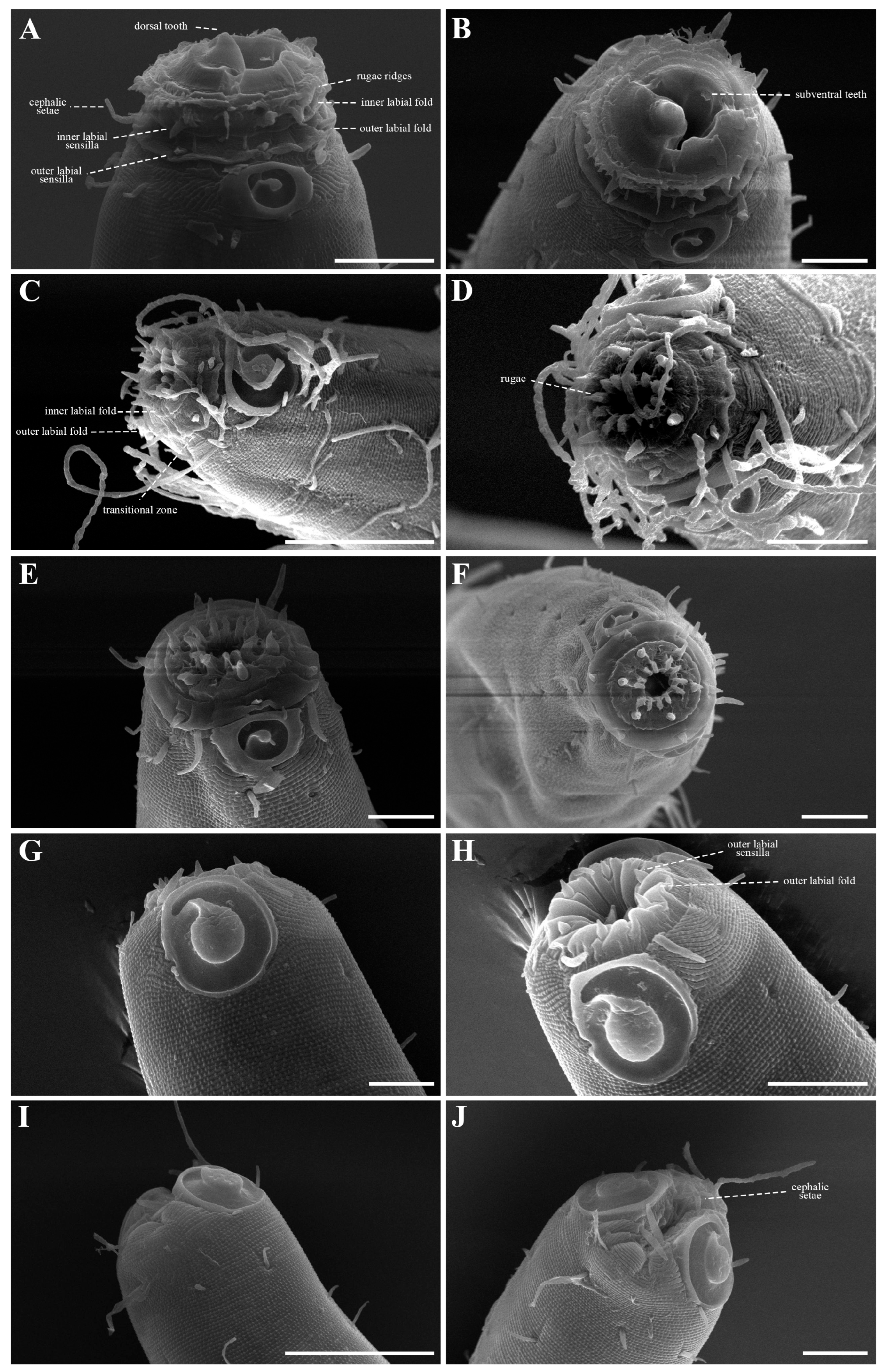

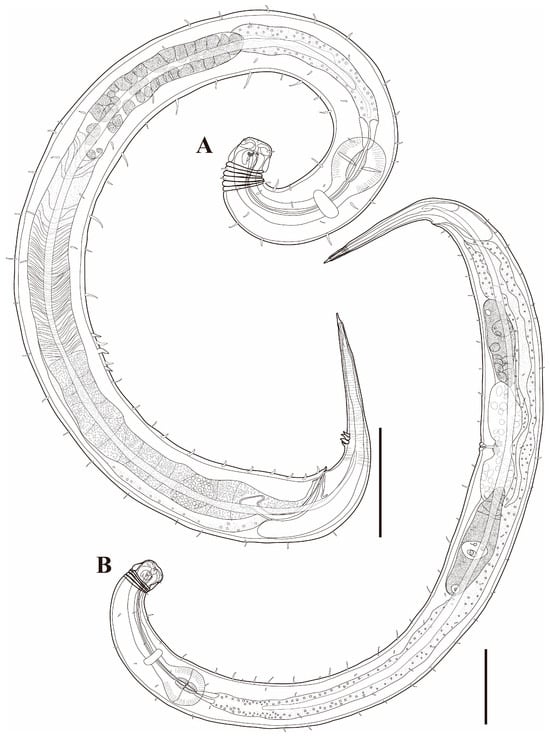

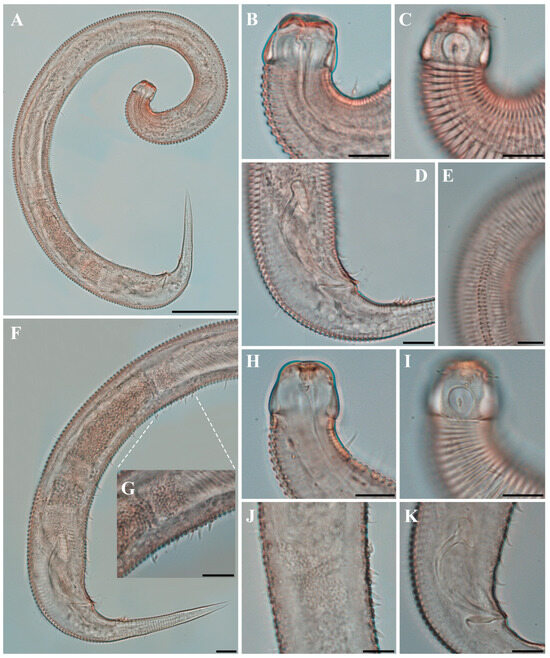

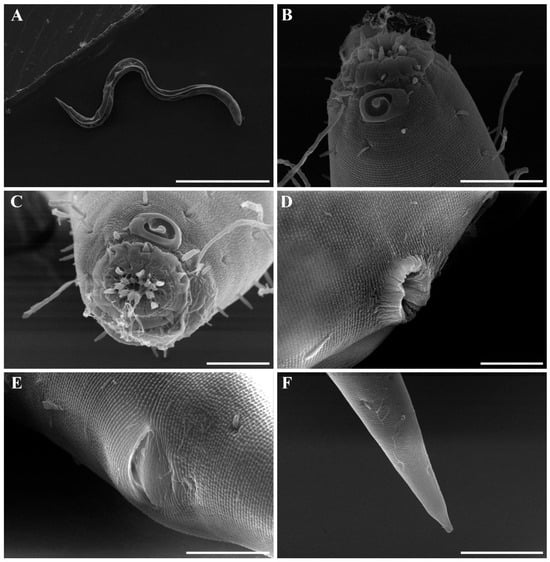

Figure 18. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material, males. (A) entire body (MABIK NA00158848); (B) internal view of head region (MABIK NA00158848); (C) external view of head region (MABIK NA00158848); (D) external view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2830); (E) internal view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2830); (F) posterior body region (MABIK NA00158848); (G) posterior body region showing precloacal elevation (KIOST NEM-1-2823). Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B–E) = 10 µm; (F) = 20 µm; (G) = 50 µm.

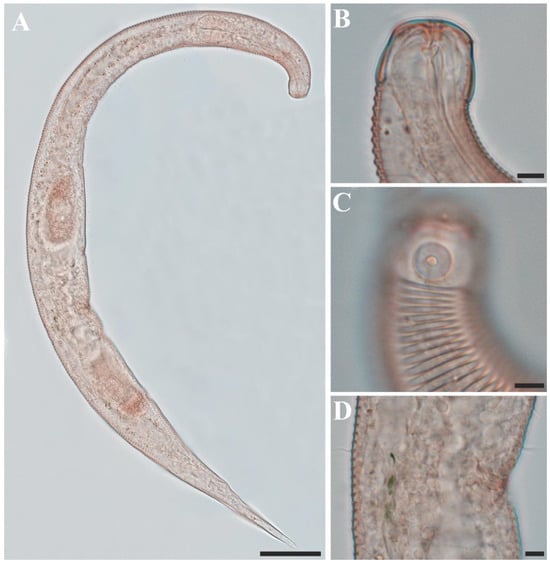

Figure 18. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material, males. (A) entire body (MABIK NA00158848); (B) internal view of head region (MABIK NA00158848); (C) external view of head region (MABIK NA00158848); (D) external view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2830); (E) internal view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2830); (F) posterior body region (MABIK NA00158848); (G) posterior body region showing precloacal elevation (KIOST NEM-1-2823). Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B–E) = 10 µm; (F) = 20 µm; (G) = 50 µm. Figure 19. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material, females. (A) entire body (KIOST NEM-1-2831); (B) external view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2832); (C) internal view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2832); (D) tail tip region showing granular ornamentation of non-annulated terminal part (KIOST NEM-1-2831); (E) posterior body region showing reproductive systems (KIOST NEM-1-2831). Scale bars: (A,E) = 100 µm; (B–D) =10 µm.

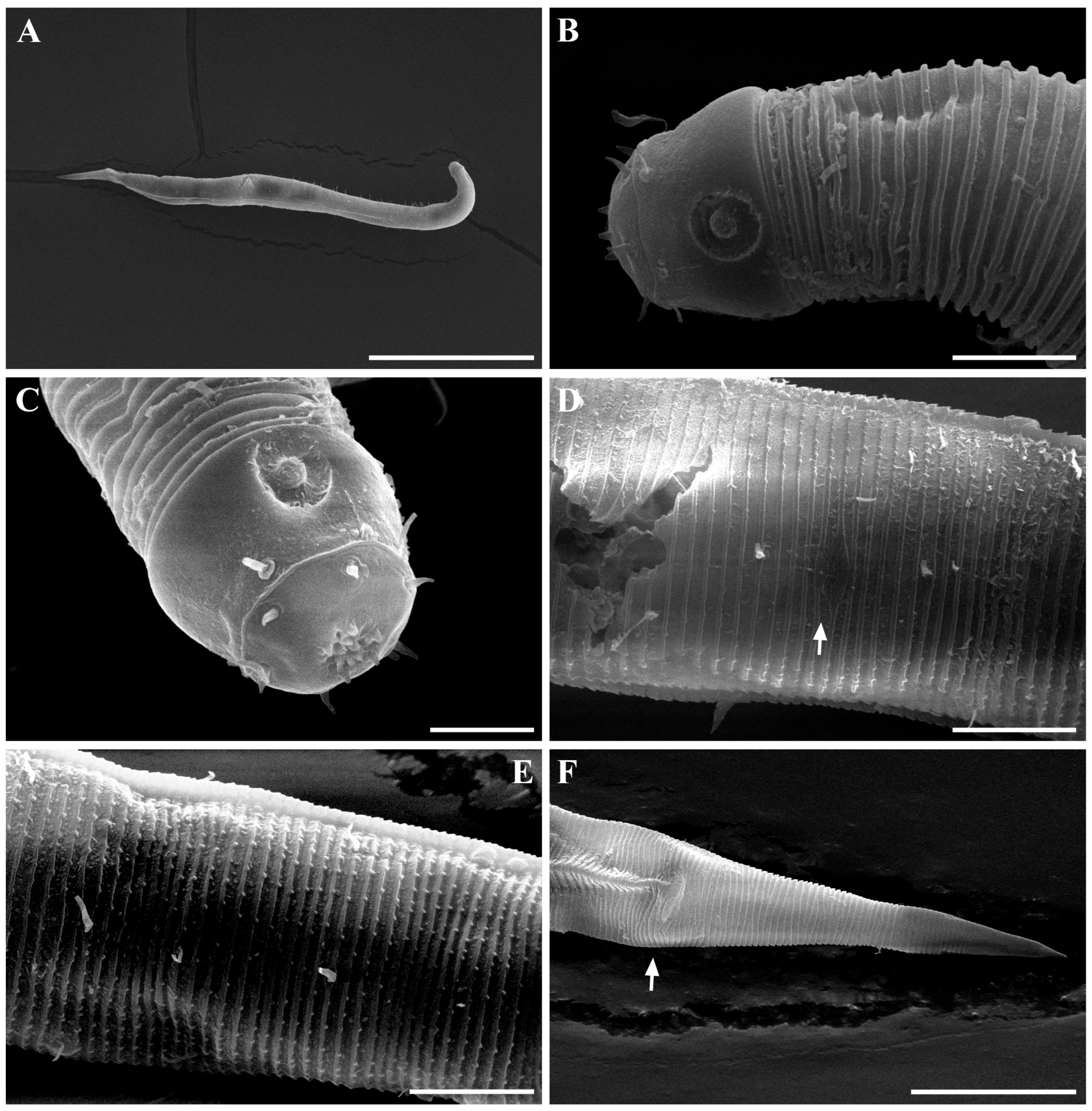

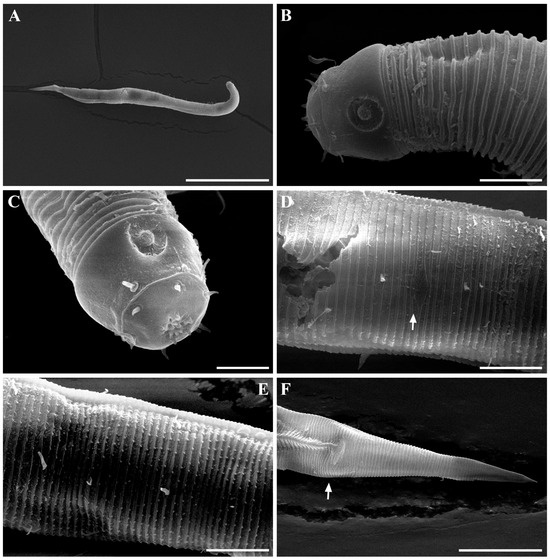

Figure 19. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material, females. (A) entire body (KIOST NEM-1-2831); (B) external view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2832); (C) internal view of head region (KIOST NEM-1-2832); (D) tail tip region showing granular ornamentation of non-annulated terminal part (KIOST NEM-1-2831); (E) posterior body region showing reproductive systems (KIOST NEM-1-2831). Scale bars: (A,E) = 100 µm; (B–D) =10 µm. Figure 20. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material. SEM micrographs, males. (A) entire body (male 1); (B) lateral alae at midbody (male 1); (C) head region (male 1); (D) oblique view of partially visible labial region (male 1); (E) lateral alae starting region (male 1); (F) precloacal cuticle elevation (male 1); (G) precloacal cuticle elevation showing papillae (male 1); (H) tail tip cuticle (male 1); (I) ventral view of cloacal opening showing spicules (male 2); (J) lateral view of tail region (male 3); (K) ventral view of postcloacal papillla (male 2). Scale bars: (A) = 300 µm; (B,K) = 5 µm; (C) = 20 µm; (D,H,I) = 10 µm; (E,G,J) = 50 µm; (F) = 100 µm.

Figure 20. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material. SEM micrographs, males. (A) entire body (male 1); (B) lateral alae at midbody (male 1); (C) head region (male 1); (D) oblique view of partially visible labial region (male 1); (E) lateral alae starting region (male 1); (F) precloacal cuticle elevation (male 1); (G) precloacal cuticle elevation showing papillae (male 1); (H) tail tip cuticle (male 1); (I) ventral view of cloacal opening showing spicules (male 2); (J) lateral view of tail region (male 3); (K) ventral view of postcloacal papillla (male 2). Scale bars: (A) = 300 µm; (B,K) = 5 µm; (C) = 20 µm; (D,H,I) = 10 µm; (E,G,J) = 50 µm; (F) = 100 µm. Figure 21. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material. SEM micrographs, female 1. (A) entire body; (B) lateral view of head region; (C) en face view of labial region; (D) vulva region; (E) anal region; (F) tail tip showing a transition from striated to irregular cuticle, followed by a smooth terminal surface. Scale bars: (A) = 500 µm; (B,F) = 20 µm; (C–E) = 10 µm.

Figure 21. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material. SEM micrographs, female 1. (A) entire body; (B) lateral view of head region; (C) en face view of labial region; (D) vulva region; (E) anal region; (F) tail tip showing a transition from striated to irregular cuticle, followed by a smooth terminal surface. Scale bars: (A) = 500 µm; (B,F) = 20 µm; (C–E) = 10 µm. Figure 22. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material. DIC photomicrographs, males. (A) entire body (MABIK NA00158848); (B) head region in optical section (MABIK NA00158848); (C) amphideal fovea (MABIK NA00158848); (D) lateral alae starting region (MABIK NA00158848); (E) spicules and gubernaculum (KIOST NEM-1-2822); (F) tail region showing two postcloacal papilla (KIOST NEM-1-2822); (G) precloacal elevation (KIOST-NEM-1-2829); (H) posterior body region (MABIK NA00158848). Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B–G) 10 µm; (H) = 50 µm.

Figure 22. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material. DIC photomicrographs, males. (A) entire body (MABIK NA00158848); (B) head region in optical section (MABIK NA00158848); (C) amphideal fovea (MABIK NA00158848); (D) lateral alae starting region (MABIK NA00158848); (E) spicules and gubernaculum (KIOST NEM-1-2822); (F) tail region showing two postcloacal papilla (KIOST NEM-1-2822); (G) precloacal elevation (KIOST-NEM-1-2829); (H) posterior body region (MABIK NA00158848). Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B–G) 10 µm; (H) = 50 µm. Figure 23. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material, DIC photomicrographs, female (KIOST NEM-1-2831). (A) entire body; (B) anterior body region showing pharyngeal bulb; (C) head region; (D) amphideal fovea; (E) vulva region; (F) lateral alae starting region; (G) tail region; (H) tail tip showing granular ornamentation on the non-annulated terminal part. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 50 µm; (C–F,H) = 10 µm; (G) = 20 µm.

Figure 23. Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, present material, DIC photomicrographs, female (KIOST NEM-1-2831). (A) entire body; (B) anterior body region showing pharyngeal bulb; (C) head region; (D) amphideal fovea; (E) vulva region; (F) lateral alae starting region; (G) tail region; (H) tail tip showing granular ornamentation on the non-annulated terminal part. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B) = 50 µm; (C–F,H) = 10 µm; (G) = 20 µm. Table 4. Morphometric measurements (in micrometers, µm) of Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978, from Korean specimens examined in the present study.

Table 4. Morphometric measurements (in micrometers, µm) of Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978, from Korean specimens examined in the present study.

Metachromadora itoi Kito, 1978: p. 249, Figure 1 and Figure 2 [39]; Yushin and Coomans, 2005: p. 255, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 [40].

3.4.1. Material Examined

One male specimen (MABIK NA00158848) is deposited in the Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), Seocheon, Korea. Additional material, comprising ten males (KIOST NEM-1-2821 to 2830) and four females (KIOST NEM-1-2831 to 2834), is housed in the nematode specimen collection of the Bio-Resources Bank of Marine Nematodes (BRBMN) at the East Sea Research Institute, Korea Institute of Ocean Science & Technology (KIOST), Korea.

3.4.2. Locality and Habitat

Specimens were collected from an intertidal sand flat at Sinchang-ri, Jeju Island, Korea (33°20′39.26″ N, 126°10′12.16″ E), on 24 May 2024. The sampling site is characterized by medium sand and is exposed during low tide.

3.4.3. Measurements

All morphometric data are provided in Table 4.

3.4.4. Description

Males. The body is cylindrical, becoming slightly narrower posterior to the pharyngeal bulb and tapering sharply behind the cloacal opening (Figure 18A, Figure 20A and Figure 22A). The cuticle is thick and finely annulated, with inter-annular spacing of approximately 1 µm; annulation begins immediately behind the cephalic setae (Figure 18C,D and Figure 20B). In the amphideal fovea region, the annules form upwardly directed lateral arcs and transverse bands dorsally and ventrally (Figure 18C,D and Figure 20C). Lateral alae are present, extending from the posterior end of the pharynx to the anterior tail region (Figure 20E and Figure 22D), interdigitating with the annules (Figure 20B). Somatic setae are short and robust, arranged in eight longitudinal rows—two lateral, two dorsal, and two ventral on each side of the body.

The cephalic region is clearly demarcated from the body and consists of two labial folds arranged in two layers (Figure 18D,E and Figure 20D). The inner labial fold bears six stout inner labial sensilla, whereas the outer labial fold is broader and carries six stout outer labial sensilla. Around the oral opening, 12 prominent rugae form a crown-like ring. The margins of both labial folds are plicate and recessed within an anterior depression. A short transitional region between the labial folds and the annulated body carries four cephalic setae (Figure 20D). The labial region may appear folded inward (Figure 18B,C) or everted (Figure 18D,E); when folded, the inner labial sensilla become concealed, giving the head a truncated appearance (Figure 22B). The amphideal fovea is spiral and situated laterally on a thickened cuticular plate (Figure 20D and Figure 22C).

The buccal cavity contains 12 rugae and is armed with one large movable dorsal tooth and two smaller ventrosublateral teeth anterior to the pharyngostome, all surrounded by well-developed pharyngeal musculature (Figure 18B,E). The pharynx is tripartite, consisting of an anterior muscular region surrounding the stoma, a narrow cylindrical corpus, and a long terminal bulb with three distinct regions and well-developed cuticular valves (Figure 22A). The terminal bulb measures 90–106 µm in length and 46–54 µm in width. The nerve ring is located at 43–49% of pharyngeal length. The cardia is elongate and inserted into the intestine (Figure 18A).

The reproductive system is monorchic, with a single anterior testis located on the right side of the intestine. The spicules are strongly arcuate, with a broad, heavily cuticularized, cephalated proximal end bearing a wide velum and tapering distally (Figure 20I and Figure 22E). The gubernaculum is weakly cuticularized; its distal part is laterally swollen, with a pointed tip extending ventrally to support the spicules (Figure 18F,G and Figure 22E). The ventral precloacal cuticle is elevated, forming a striated membrane with 19–26 button-like openings connected by narrow ducts (Figure 20G and Figure 22G), extending 297–472 µm anterior to the cloacal opening (Figure 18G, Figure 20F and Figure 22H). Precloacal setae are arranged as 10–18 subventral pairs in two longitudinal rows, each seta 12–16 µm long.

The tail is short and conical (Figure 18F), with a smooth cuticle over its distal one-fifth (Figure 20H). Two conical ventral papillae are present (Figure 22F), the anterior located 31–50 µm from the cloacal opening. SEM images show longitudinally aligned cuticular elevations surrounding the papillae along the ventral midline (Figure 20J,K).

Females. Females are similar to males in general morphology (Figure 19C and Figure 23B,C,F), but the posterior body is markedly swollen to accommodate the reproductive system (Figure 19A, Figure 21A and Figure 23A). The amphideal fovea is smaller, spiral with approximately 1.25 turns, situated on a lateral cuticular plate (Figure 19B, Figure 21B,C and Figure 23D). The reproductive system is didelphic–amphidelphic with reflexed ovaries located on the right side of the intestine (Figure 19E). The pars distalis vaginaeis sclerotized, and the pars proximalis vaginae is surrounded by constrictor muscles (Figure 23E). The vulva is small and silt-like, and under SEM the open vulva appears as a series of cuticular folds (Figure 21D). The cloacal opening is slightly protruding and appears as a transversely elongate slit (Figure 21E). The tail is short and conical and lacks ventral papillae (Figure 23G). In the distal third of the tail, the annulation is interrupted and replaced by a 16–17 µm-long region of granular ornamentation (Figure 19D, Figure 21F and Figure 23H). The distal quarter of the tail is smooth and tapers to a slender tip.

3.4.5. Remarks

The genus Metachromadora, within the subfamily Spiriniinae Gerlach & Murphy, 1965, represents a complex and taxonomically dynamic group that has undergone several revisions since its original establishment [41]. Gerlach (1951) initially subdivided the genus into five subgenera—Bradylaimus, Chromadoropsis, Metonyx, Metachromadora, and Neonyx—based on the presence, type, and distribution of somatic setae, the morphology and presence of precloacal supplements, and the occurrence of lateral fields (alae) [42]. Subsequently, Timm (1961) proposed a sixth subgenus, Metachromadoroides, which included M. vulgaris and M. complexa, and later Furstenberg & Vincx (1988) elevated Chromadoropsis to full genus rank [32,43]. Currently, Metachromadora comprises five recognized subgenera and includes 28 valid species worldwide [41,44,45].

Species in this genus are typically characterized by a spiral or cryptospiral amphideal fovea partially surrounded by cuticular striations; a buccal cavity containing a large dorsal tooth and two smaller ventrosublateral teeth in most species; longitudinal lateral ridges in some taxa; a posterior pharyngeal bulb divided internally into two or three compartments; and various types of precloacal supplements in males [12,44].

The present specimens exhibit longitudinal cuticular striations on the head, and the combination of morphological features clearly places them within the subgenus Metachromadora Filipjev, 1918. To date, only three species have been described within this subgenus: M. macroutera Filipjev, 1918, M. chandleri (Chitwood, 1951), and M. itoi Kito, 1978 [39,46,47]. Among them, the specimens examined here are most similar to M. macroutera and M. chandleri, but can be readily distinguished by several morphological features.

Metachromadora macroutera shares the presence of arcuate annules on the anterior head, but differs in its longer body length (2.4–2.7 mm vs. 1.2–1.6 mm), absence of sexual dimorphism in the amphideal fovea, and a higher number of precloacal supplements (26–48 vs. 21–25). M. chandleri is similar in body length and also exhibits sexual dimorphism in the amphideal fovea, but differs in having clearly defined obliquely orientated annules on the anterior head and fewer precloacal supplements (12–14).

The present specimens agree well with the diagnostic characteristics of M. itoi, including the presence of arcuate longitudinal striations around the amphideal fovea, sexually dimorphic amphideal fovea, a well-developed tripartite pharyngeal bulb, the detailed morphology of the spicules and gubernaculum, the number and arrangement of precloacal supplement papillae on the cuticular elevation, and the sexually dimorphic pattern of caudal striations. The only notable difference is that the Korean specimens possess slightly larger bodies (1480–2100 μm) compared to the original Japanese material (1428–1596 μm), which may reflect geographic or habitat-related variation.

Importantly, this study provides the first confirmed record of M. itoi from the Korean coast, thereby extending the known geographical distribution of the species. The Korean specimens were collected from intertidal sandy sediments at depths shallower than 1 m, whereas the type specimens from Japan originated from sublittoral fine sand at a depth of 25 m. In addition, the species has been reported from silty sand at 1 m depth near the Vostok Marine Biological Station, Vostok Bay, Sea of Japan (Russia) [40].

3.4.6. Distribution

Japan, Hokkaido (Kito, 1978) [39]; Russia, Vostok Bay, Sea of Japan (Yushin and Coomans, 2005) [40]; Korea, Jeju Island (this study).

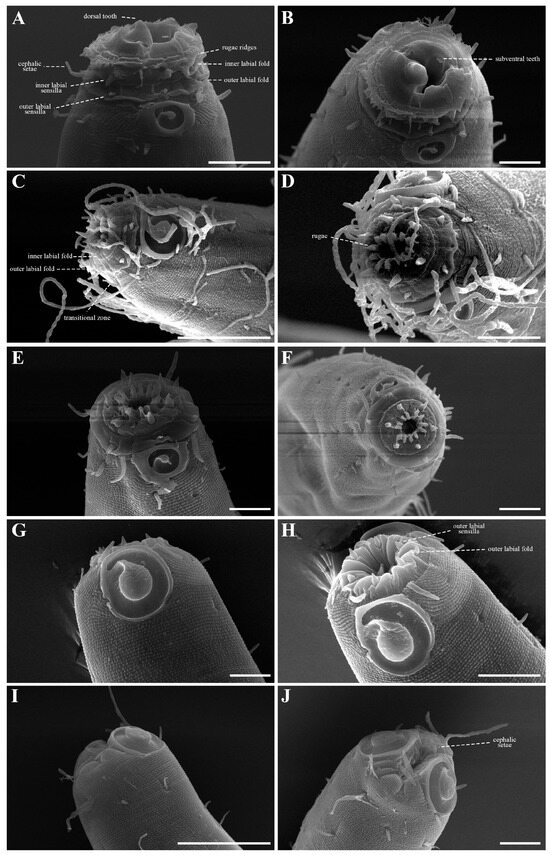

3.5. Supplementary SEM Observations

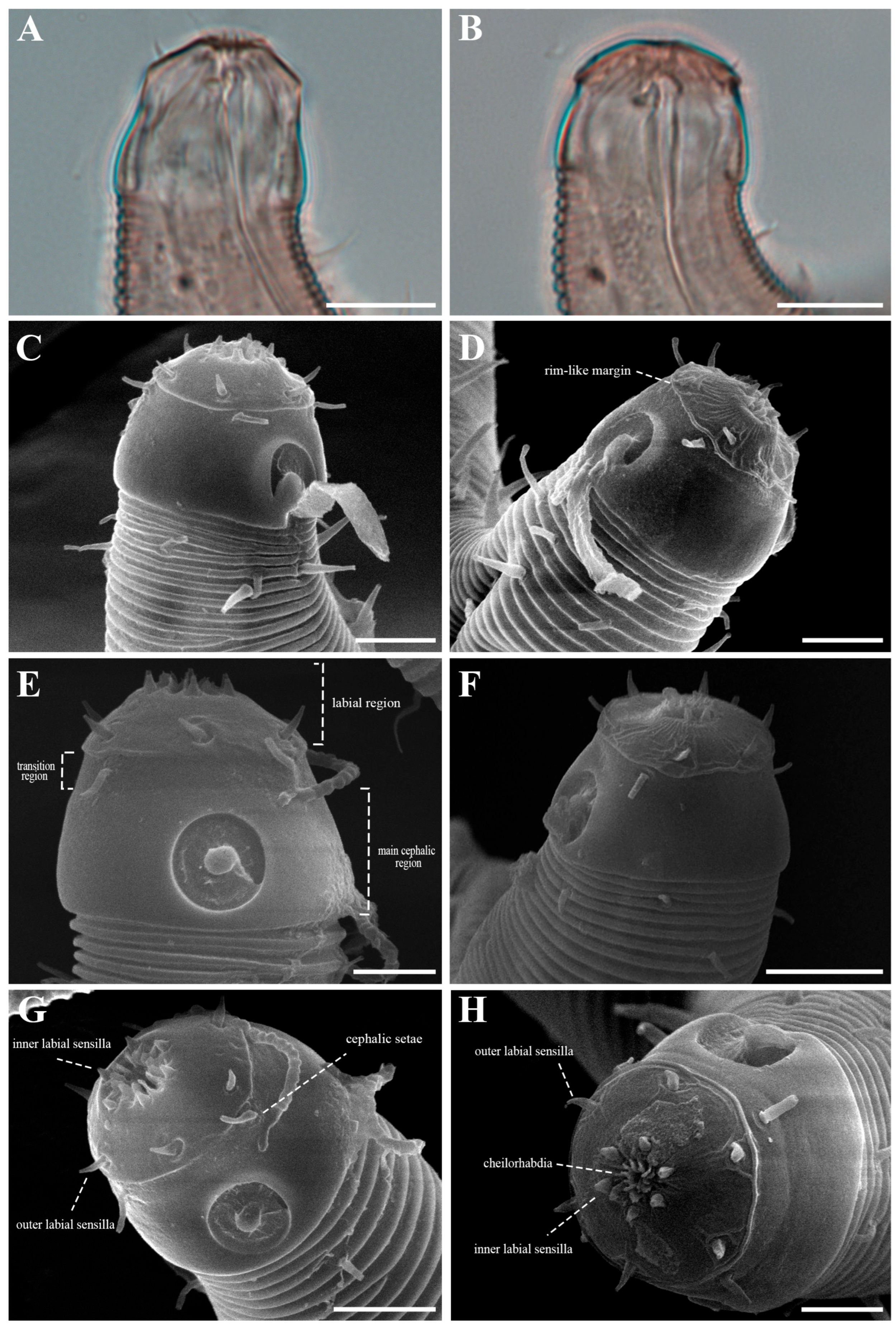

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of Metachromadora itoi specimens collected from Korean coastal sediments revealed distinct stepwise external morphological changes in the lip region and buccal cavity depending on the degree of muscular contraction. These changes resemble those illustrated for M. chandleri by Chitwood (1955) and are consistent with the broader observation that nematode buccal morphology undergoes dynamic reconfiguration during feeding or in response to external stimuli [48].

In en face view, the buccal opening is encircled by 12 cuticular rugae. Six inner labial sensilla are positioned on the inner labial fold, while six outer labial sensilla are situated on broader outer labial fold. Four cephalic setae are located posterior to the labial region. These sensory structures, associated with underlying radial muscles, likely play roles in both chemoreception and the mechanical processes of mouth opening, closure, and prey manipulation.

In this study, SEM analysis focused on contraction-dependent transformations of the oral region. Since the buccal region of free-living marine nematodes undergoes continuous in vivo movements, a fixed “resting state” is difficult to define. Additionally, sample preparation for SEM may preserve specimens in various states of contraction. Thus, following Fürst von Lieven (2002) [49], we describe oral morphology in terms of five contraction stages: fully open, partially contracted I, partially contracted II, partially contracted III, and fully contracted.

- Stage 1: Fully open (Figure 24A,B)

Figure 24. Sequential contraction stages of the anterior region in Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, SEM micrographs. (A,B) Stage 1: Fully open, with everted labial folds and protruded dorsal tooth; (C,D) Stage 2: Partial contraction I, buccal opening narrowed, rugae and transitional zone exposed; (E,F) Stage 3: Partial contraction II, further narrowing with flattened labial folds; rugae and sensilla still visible en face; (G,H) Stage 4: Partial contraction III, inner labial fold folded inward and outer labial fold partly infolded; (I,J) Stage 5: Fully contracted, all folds invaginated. Scale bars: (A,B,D–H,J) = 10 µm; (C,I) = 30 µm.

Figure 24. Sequential contraction stages of the anterior region in Metachoromadora itoi Kito, 1978, SEM micrographs. (A,B) Stage 1: Fully open, with everted labial folds and protruded dorsal tooth; (C,D) Stage 2: Partial contraction I, buccal opening narrowed, rugae and transitional zone exposed; (E,F) Stage 3: Partial contraction II, further narrowing with flattened labial folds; rugae and sensilla still visible en face; (G,H) Stage 4: Partial contraction III, inner labial fold folded inward and outer labial fold partly infolded; (I,J) Stage 5: Fully contracted, all folds invaginated. Scale bars: (A,B,D–H,J) = 10 µm; (C,I) = 30 µm.

The cuticular flaps are everted, and the dorsal tooth extends beyond the buccal margin. In en face view, both the dorsal and ventrosublateral teeth are visible, representing a likely preparatory state for feeding or substrate interaction.

- Stage 2: Partial contraction I (Figure 24C,D)

Partial contraction of radial musculature narrows the buccal aperture, accentuating the visibility of the 12 rugae. The cuticle-free transitional zone bearing cephalic setae is clearly exposed. Bilayered labial folds become expanded, and both labial sensilla and cephalic setae are prominently visible.

- Stage 3: Partial contraction II (Figure 24E,F)

Further contraction narrows the buccal opening. Labial folds appear flattened, giving the anterior head a truncated shape. In lateral view, the transitional zone becomes obscured posterior to the folds, though the rugae and papilla-like sensilla remain discernible in en face view.

- Stage 4: Partial contraction III (Figure 24G,H)

The inner labial fold is folded fully inward, while the outer labial fold is partially invaginated, giving a wrinkled appearance. The outer labial sensilla remain exposed, and in lateral view, the head retracts to the level of the amphideal fovea, making the transitional zone prominent.

- Stage 5: Fully contracted (Figure 24I,J)

All labial folds are deeply invaginated within the buccal cavity. Outer labial sensilla are completely retracted. The four cephalic setae converge and interlock across the buccal opening, effectively sealing the mouth. Amphideal fovea are positioned close to the buccal margin and remain visible in en face view.

4. Discussion

This study integrates morphological observations, molecular data, and SEM-based microstructural analyses to provide a clearer framework for interpreting diagnostic characters and phylogenetic relationships within the Desmodoridae. The two newly described species, Pseudochromadora paraparva sp. nov. and P. capitata sp. nov., exhibit distinctive combinations of cephalic morphology, sexually dimorphic amphideal fovea, and species-specific arrangements of copulatory thorns. These traits contribute to a refined delineation of species boundaries within the genus and underscore the taxonomic value of these diagnostic features.

Molecular analyses based on 18S and 28S rDNA further support the distinctiveness and phylogenetic placement of both species. Each formed a well-supported monophyletic clade and displayed the characteristic pattern of low intraspecific and high interspecific divergence expected for species-level differentiation within the Desmodoridae. However, molecular data for Pseudochromadora remain unevenly represented in GenBank, with several taxa documented for only one of the two markers. Consequently, the concatenated dataset in this study was structured primarily around the 18S rDNA marker, a constraint that may limit the resolution of broader phylogenetic relationships within the genus. In addition, although certain diagnostic morphological traits show trends that broadly parallel the observed molecular divergence among species, the incomplete molecular sampling across Pseudochromadora makes it difficult to assess these correspondences with confidence. The repeated placement of P. plurichela outside the Pseudochromadora clade suggests that its species identification or generic assignment may require re-evaluation. These findings highlight the importance of integrating molecular evidence with morphological information to achieve more robust taxonomic conclusions.