Analysis of the Distribution of Epiphytic Corticolous Lichens in the Forests Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

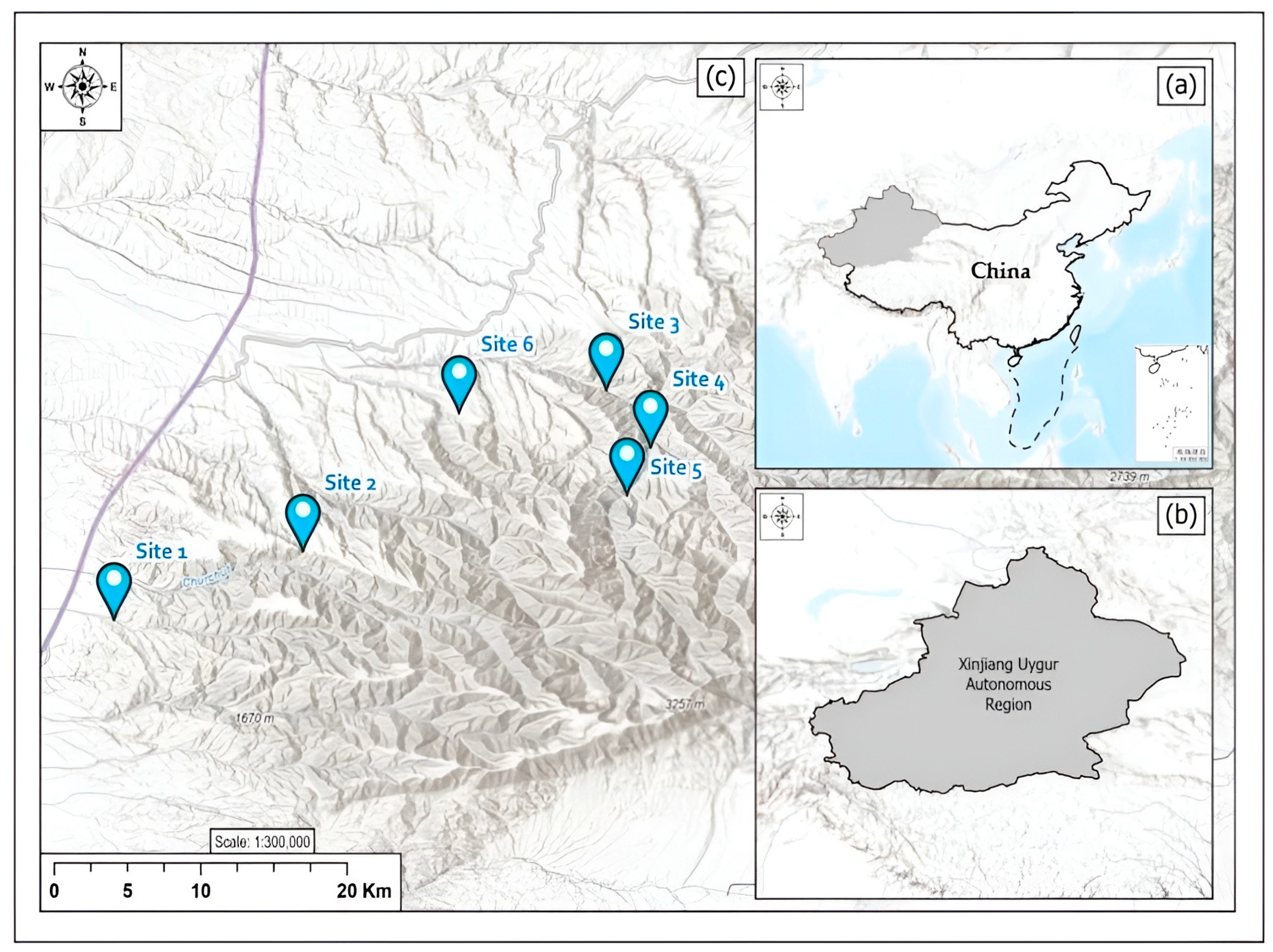

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Design

2.3. Species Identification and Lichen Functional Traits

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Lichen Species Composition

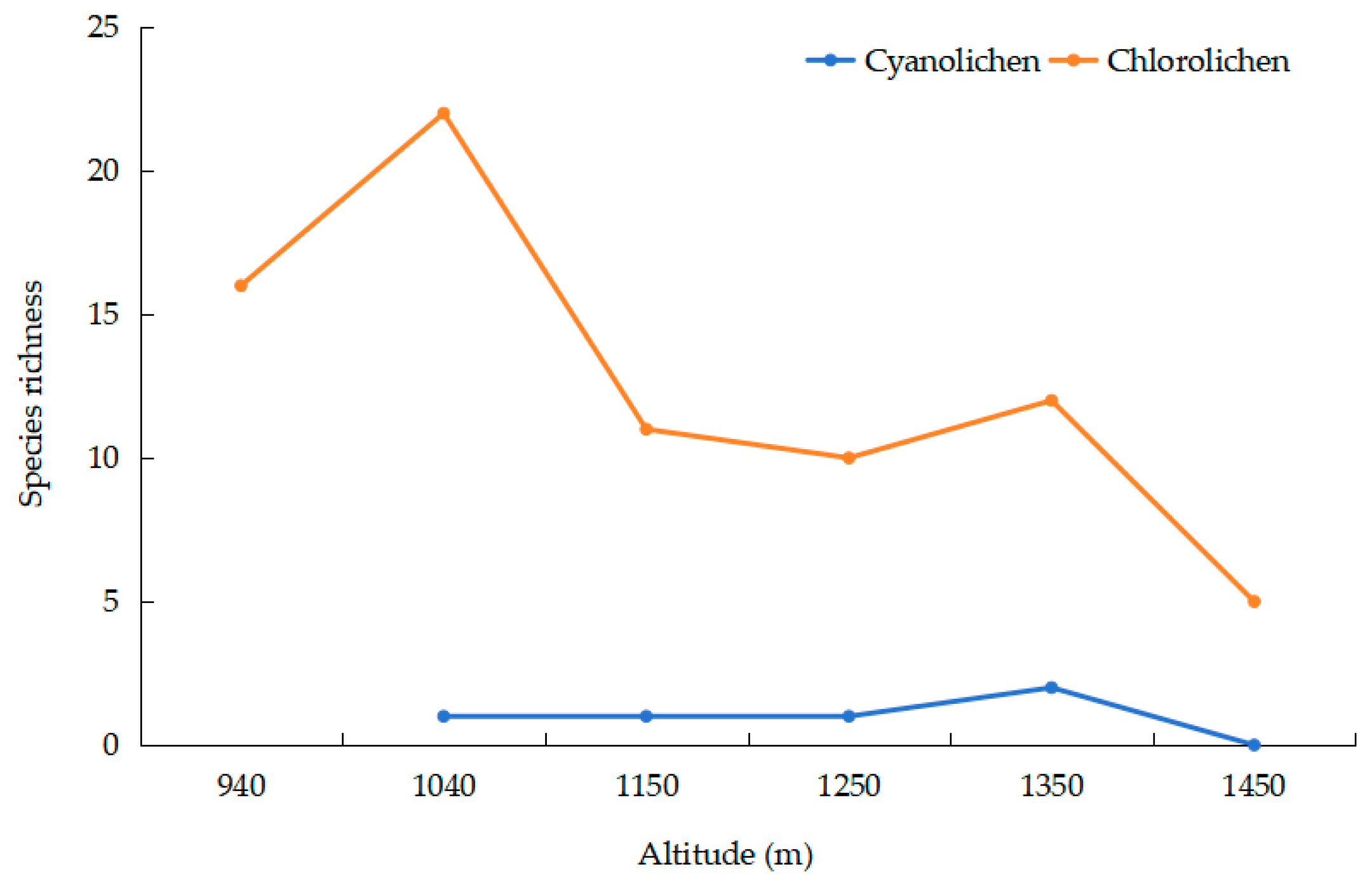

3.2. The Relationship Between Species Richness and Elevation

3.3. The Relationship Between Lichen Functional Traits and Elevation

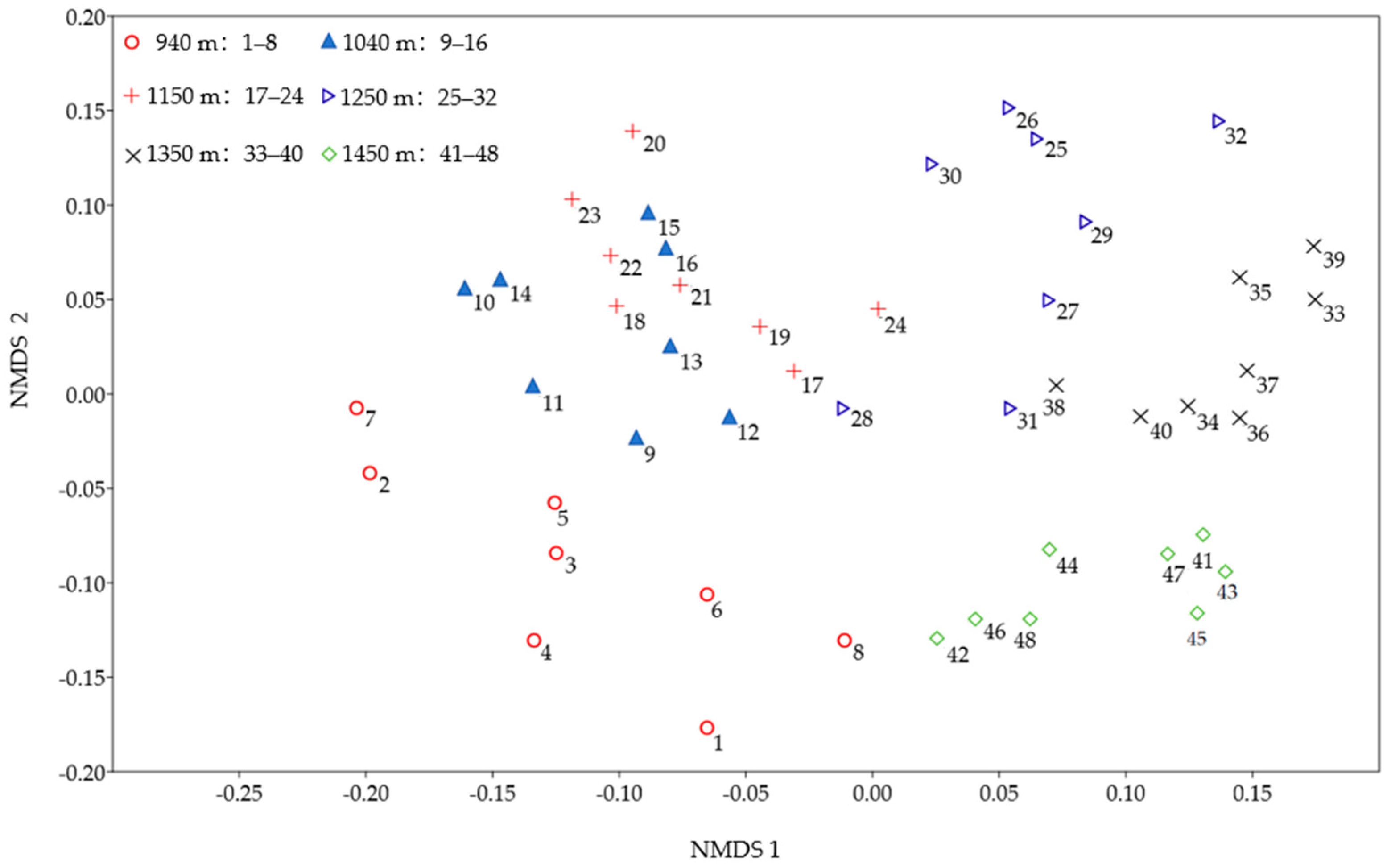

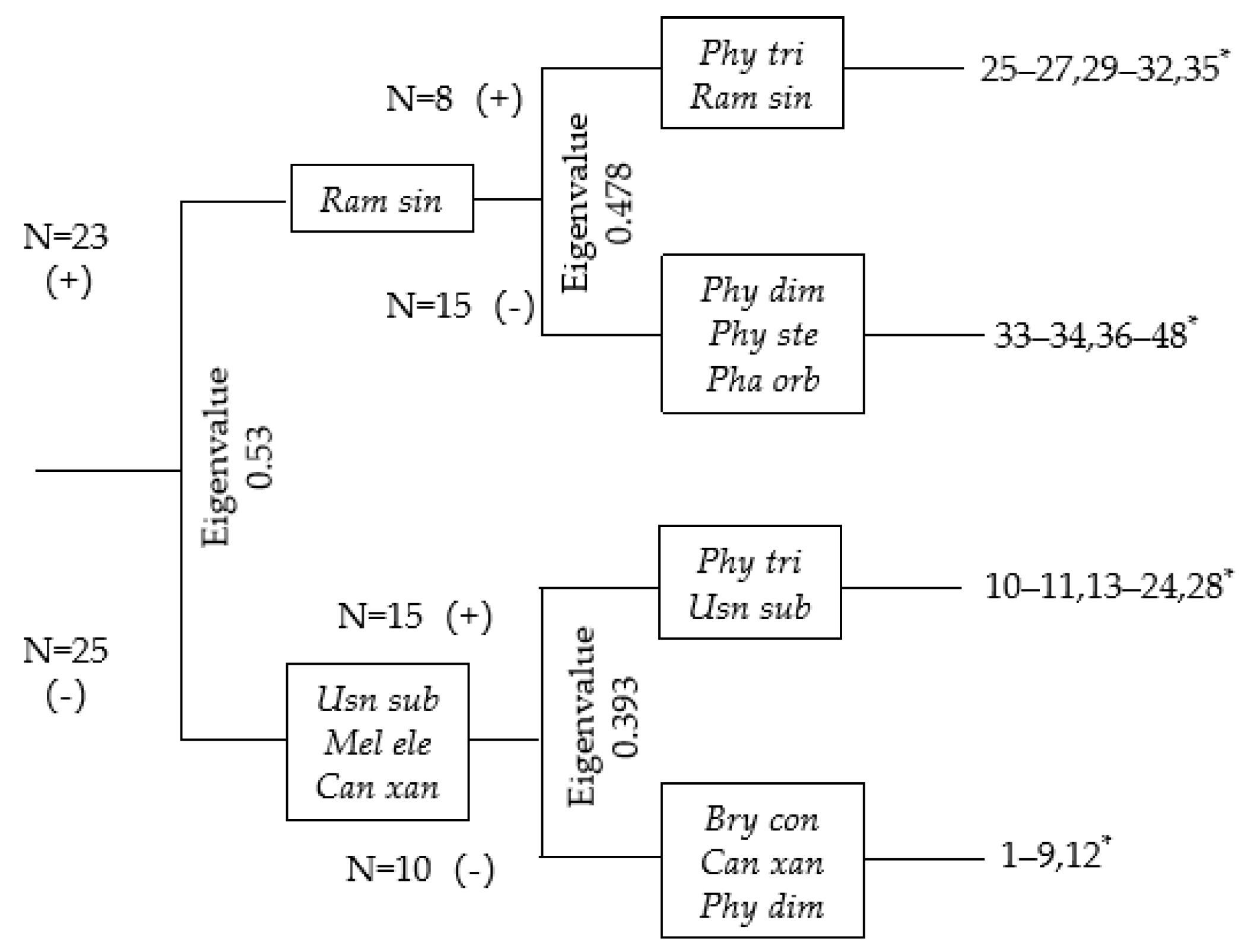

3.4. Distribution of Epiphytic Corticolous Lichens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMNNR | Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve |

Appendix A

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 | P13 | P14 | P15 | P16 | P17 | P18 | P19 | P20 | P21 | P22 | P23 | P24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bry con | 2.12 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 1.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.21 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Can ole | 0.00 | 2.35 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Can xan | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.52 | 3.54 | 0.00 | 2.89 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 5.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.03 | 1.28 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 1.11 | 2.65 | 0.00 |

| Col sub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.20 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| Col subf | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fla cor | 1.21 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 1.38 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fla fla | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 1.30 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec chl | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec sal | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.25 | 0.97 | 5.52 | 0.11 | 1.04 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 2.42 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec xyl | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.12 | 0.65 | 2.05 | 1.87 | 0.65 | 1.36 | 0.87 | 0.00 |

| Lec ela | 0.00 | 1.25 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Myr hag | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.87 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.24 | 2.46 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mel exa | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 2.39 | 1.12 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 1.39 |

| Mel ele | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 1.34 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 1.23 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 1.36 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| Mel sub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mel sp | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.25 |

| Pha sp | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha his | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 2.51 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha lim | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha orb | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.16 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 2.98 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.47 |

| Phy aip | 0.00 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phy dim | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 1.36 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 1.14 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 1.75 | 1.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 2.3 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phy dub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phy ste | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.38 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 5.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.63 |

| Phy tri | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.10 | 2.35 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 1.36 | 2.06 | 2.25 | 0.25 | 2.58 | 0.69 | 5.24 | 2.36 | 1.58 | 0.65 | 3.36 |

| Phy gri | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ram sin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Usn sub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 2.35 | 1.32 | 0.25 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 0.98 | 2.25 | 3.25 | 0.54 | 1.65 | 0.68 | 2.35 | 4.25 | 3.28 | 1.14 |

| Bry con | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Can ole | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.2 | 1.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Can xan | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.64 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Col sub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.77 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Col subf | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fla cor | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fla fla | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.46 | 2.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec chl | 2.22 | 0.00 | 1.19 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 3.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec sal | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec xyl | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lec ela | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Myr hag | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mel exa | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mel ele | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mel sub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mel sp | 8.2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha sp | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha his | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha lim | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.88 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pha orb | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.31 | 0.52 | 1.86 | 0.69 | 3.28 | 1.65 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 2.15 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.68 | 0.00 |

| Phy aip | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phy dim | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 1.23 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 7.92 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Phy dub | 2.03 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 2.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 1.45 | 3.01 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phy ste | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.25 | 0.87 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 1.25 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 3.27 | 6.32 | 8.54 | 10.2 | 0.68 | 3.25 | 5.32 | 0.25 | 6.35 |

| Phy tri | 3.25 | 2.02 | 1.65 | 6.38 | 2.38 | 0.58 | 4.25 | 6.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phy gri | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 0.24 | 2.46 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 3.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ram sin | 2.14 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.89 | 1.12 | 0.65 | 0 | 0.05 | 1.02 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Usn sub | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Family | Genus | Species | Abbr. | Photobiont | Growth Form | Reproduction Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candelariaceae | Candelariella | C. oleifera H. Magn. | Can ole | Ch | Crustose | Sex |

| C. xanthostigma (Ach.) Lettau | Can xan | Ch | Crustose | Sex | ||

| Physciaceae | Physcia | P.aipolia (Ehrh. ex Humb.) Fürnr. | Phy aip | Ch | Foliose | Sex |

| P.dimidiata (Arnold) Nyl. | Phy dim | Ch | Foliose | A.s | ||

| P.dubia (Hoffm.) Lettau | Phy dub | Ch | Foliose | Sex | ||

| P.stellaris (Linn.) Nyl. | Phy ste | Ch | Foliose | Sex | ||

| P.tribacia (Ach.) Nyl. | Phy tri | Ch | Foliose | A.s | ||

| Phaeophyscia | Phaeophyscia sp. | Pha sp | Ch | Foliose | Sex | |

| P. hispidula (Ach.) Moberg | Pha his | Ch | Foliose | A.s | ||

| P. limbata (Poelt) Kashiw. | Pha lim | Ch | Foliose | A.s | ||

| P.orbicularis (Neck.) Moberg | Pha orb | Ch | Foliose | A.s | ||

| Physconia | P.grisea (Lam.) Poelt | Phys gri | Ch | Foliose | A.s | |

| Lecanoraceae | Lecanora | L.chlarotera Nyl. | Lec chl | Ch | Crustose | Sex |

| L. saligna (Schrad.) Zahlbr. | Lec sal | Ch | Crustose | Sex | ||

| L.xylophila Hue | Lec xyl | Ch | Crustose | Sex | ||

| Lecidella | L.elaeochroma (Ach.) M. Choisy | Lec ela | Ch | Crustose | Sex | |

| Myriolecis | M. hagenii (Ach.) Śliwa, Zhao Xin et Lumbsch | Mys hag | Ch | Crustose | Sex | |

| Parmeliaceae | Bryoria | B.confusa (D. D. Awasthi) Brodo & D. Hawksw. | Bry con | Ch | Fruticose | A.f |

| Flavopunctelia | F. flaventior (Stirt.) Hale | Fla fla | Ch | Foliose | A.s | |

| Melanohalea | M.exasperatula (Nyl.) Essl. | Mel exa | Ch | Foliose | A.i | |

| M.elegantula (Zahlbr.) O. Blanco et al. | Mel ele | Ch | Foliose | A.i | ||

| M. subelegantula (Essl.) O. Blanco et al. | Mel sub | Ch | Foliose | A.i | ||

| Melanohalae sp. | Mel sp | Ch | Foliose | A.i | ||

| Usnea | U. subfloridana Stirt. | Usn sub | Ch | Fruticose | A.s | |

| Ramalinaceae | Ramalina | R.sinensis Jatta | Ram sin | Ch | Fruticose | Sex |

| Collemataceae | Collema | C.subconveniens Nyl. | Col subc | Nos | Foliose | A.i |

| C.subflaccidum Degel. | Col sub | Nos | Foliose | A.i | ||

| Teloschistaceae | Flavoplaca | F. coronata (Kremp. ex Körb.) Arup | Fla cor | Ch | Crustose | Sex |

| Name of Species | Altitude of Sampling Sites (m) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 940 | 1040 | 1150 | 1250 | 1350 | 1450 | |

| Bryoria confusa | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Candelariella oleifera | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Candelariella xanthostigma | 12 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Collema subconveniens | 0 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Collema subflaccidum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 0 |

| Flavoplaca coronata | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Flavopunctelia flaventior | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Lecanora chlarotera | 5 | 8 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Lecanora saligna | 4 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Lecanora xylophila | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Lecidella elaeochroma | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myriolecis hagenii | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Melanohalea exasperatula | 8 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Melanohalea elegantula | 0 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Melanohalea subelegantula | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Melanohalea sp. | 0 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| Phaeophyscia sp. | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Phaeophyscia hispidula | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phaeophyscia limbata | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Phaeophyscia orbicularis | 0 | 16 | 4 | 0 | 19 | 14 |

| Physcia aipolia | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Physcia dimidiata | 9 | 5 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 15 |

| Physcia dubia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 0 |

| Physcia stellaris | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Physcia tribacia | 0 | 21 | 24 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Physconia grisea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 0 |

| Ramalina sinensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 17 | 0 |

| Usnea subfloridana | 0 | 16 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Species richness | 16 | 23 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 5 |

| Number of collected specimens | 90 | 177 | 121 | 108 | 118 | 39 |

| Species | Altitude (m) | One-Way ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 940 | 1040 | 1150 | 1250 | 1350 | 1450 | F | Sig. | |

| Bryoria confusa | 12.15 ± 6.73 | 4.87 ± 3.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.26 | 0.01 |

| Candelariella oleifera | 7.77 ± 4.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.63 ± 0.87 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 0.06 |

| Candelariella xanthostigma | 12.86 ± 5.14 | 7.75 ± 4.53 | 10.96 ± 3.99 | 0.00 | 3.95 ± 2.63 | 0.00 | 2.54 | 0.04 |

| Collema subconveniens | 0.00 | 1.56 ± 0.82 | 2.82 ± 0.94 | 0.00 | 10.76 ± 7.12 | 0.00 | 2.02 | 0.09 |

| Collema subflaccidum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.05 ± 2.61 | 4.81 ± 2.48 | 0.00 | 2.94 | 0.02 |

| Flavoplaca coronata | 12.67 ± 4.17 | 2.01 ± 0.87 | 0.48 ± 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.15 | 0.00 |

| Flavopunctelia flaventior | 9.27 ± 3.23 | 0.93 ± 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.93 ± 3.91 | 0.00 | 4.14 | 0.00 |

| Lecanora chlarotera | 3.54 ± 1.85 | 3.81 ± 1.33 | 0.00 | 11.43 ± 6.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.38 | 0.05 |

| Lecanora saligna | 7.17 ± 3.22 | 7.68 ± 3.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.48 ± 0.98 | 3.59 | 0.01 |

| Lecanora xylophila | 3.93 ± 2.47 | 2.25 ± 0.93 | 11.16 ± 2.62 | 0.00 | 0.46 ± 0.21 | 0.00 | 8.30 | 0.00 |

| Lecidella elaeochroma | 5.28 ± 2.51 | 3.12 ± 1.2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.66 | 0.01 |

| Myriolecis hagenii | 5.01 ± 3.17 | 5.18 ± 2.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.54 | 0.00 |

| Melanohalea exasperatula | 5.25 ± 2.24 | 2.56 ± 1.27 | 7.71 ± 2.16 | 5.48 ± 3.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.72 | 0.03 |

| Melanohalea elegantula | 0.00 | 7.57 ± 2.22 | 5.9 ± 2.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.85 | 0.00 |

| Melanohalea subelegantula | 5.01 ± 2.11 | 2.31 ± 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.35 | 0.06 |

| Melanohalea sp. | 0.00 | 1.68 ± 0.68 | 2.93 ± 1.94 | 5.01 ± 1.24 | 0.00 | 3.09 ± 1.87 | 0.58 | 0.71 |

| Phaeophyscia sp. | 0.00 | 2.31 ± 1.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.66 ± 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.52 |

| Phaeophyscia hispidula | 4.77 ± 2.32 | 2.87 ± 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 0.18 |

| Phaeophyscia limbata | 0.00 | 1.12 ± 0.76 | 0.00 | 1.53 ± 0.58 | 1.50 ± 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.80 |

| Phaeophyscia orbicularis | 0.00 | 8.93 ± 4.01 | 1.96 ± 0.78 | 0.00 | 16.81 ± 4.25 | 16.99 ± 7.36 | 4.14 | 0.00 |

| Physcia aipolia | 8.87 ± 3.87 | 2.81 ± 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.16 | 0.02 |

| Physcia dimidiata | 13.26 ± 4.17 | 2.69 ± 1.17 | 7.80 ± 2.91 | 7.58 ± 2.09 | 2.73 ± 1.21 | 13.50 ± 7.82 | 1.35 | 0.26 |

| Physcia dubia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.82 ± 3.49 | 12.75 ± 4.86 | 0.00 | 4.65 | 0.00 |

| Physcia stellaris | 7.58 ± 3.79 | 2.37 ± 1.96 | 11.02 ± 6.47 | 8.40 ± 3.55 | 10.26 ± 3.61 | 64.91 ± 9.74 | 18.52 | 0.00 |

| Physcia tribacia | 0.00 | 16.01 ± 3.82 | 17.86 ± 4.82 | 33.51 ± 7.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.47 | 0.00 |

| Physconia grisea | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.17 ± 1.32 | 14.24 ± 3.76 | 0.00 | 10.29 | 0.00 |

| Ramalina sinensis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.30 ± 2.54 | 10.48 ± 3.71 | 0.00 | 8.65 | 0.00 |

| Usnea subfloridana | 0.00 | 13.01 ± 3.81 | 19.33 ± 4.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 14.76 | 0.00 |

References

- Rinas, C.R.; Haughian, S.R.; Harper, K.A. Diversity, composition, and gastropod grazing of epiphytic lichen communities of forested wetlands at clearcut and intact edges in Nova Scotia, Canada. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 595, 123045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Iqbal, Z.; Shah, G.M.; Haq, F. Diversity, distribution, and environmental influences on epiphytic lichens in the Hazara Division, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Ecol. Fron. 2025, 46, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, T.; Kaufmann, S.; Hauck, M. Tree, stand, and landscape scale effect on epiphytic lichen and bryophyte diversity in temperate mountain forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 594, 122967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W.H.; Patricia, L.H. The Macrolichens of New England; The New York Botanical Garden Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, D.J. Biodiversity: A lichenological perspective. Biodivers. Conserv. 1992, 1, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.J. Lichen epiphyte diversity: A species, community and trait-based review. Perspect. Plant Ecol. 2012, 14, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, W.Y.; Li, D.W. Bole epiphytic lichens as potential indicators of environmental change in subtropical forest ecosystems in southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunialti, G.; Frati, L.; Aleffi, M.; Marignani, M.; Rosati, L.; Burrascano, S. Lichens and bryophytes as indicators of old-growth features in Mediterranean forests. Plant Biosyst. 2010, 144, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ilvesniemi, H.; Westman, C.J. Biomass of arboreal lichens and its vertical distribution in a boreal coniferous forest in central Finland. Lichenologist 2000, 32, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, G.; Martínez, I.; Izquierdo, P.; Belinchón, R.; Escudero, A. Effects of forest management on epiphytic lichen diversity in Mediterranean forests. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2010, 13, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P. Consequences of disturbance on epiphytic lichens in boreal and near boreal forests. Biol. Conser. 2008, 141, 1933–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobajo, S.; Martinez, I.; Prieto, M.; Fernandez-Salegui, A.B.; Terron, A.; Hurtado, P. Multi-scale environmental drives of lichen diversity: Insights for forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 585, 122671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubek, A.; Adamowski, W.; Dyderski, M.K.; Wierzcholska, S.; Czortek, P. Invasive Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. hosts more lichens than native tree species does quantity reflect quality? For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 590, 122812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łubek, A.; Kukwa, M.; Czortek, P.; Jaroszewicz, B. Impact of Fraxinus excelsior dieback on biota of ash-associated lichen epiphytes at the landscape and community level. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 29, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, L.; Nascimbene, J.; Nimis, P.L. Large-scale patterns of epiphytic lichen species richness: Photobiont-dependent response to climate and forest structure. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4381–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomolino, M.V. Elevational gradients of species-density: Historical and prospective views. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2001, 10, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, J.; Marini, L. Epiphytic lichen diversity along elevational gradients: Biological traits reveal a complex response to water and energy. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, H.; Dainese, M.; Chiarucci, A.; Nascimbene, J. Networks of epiphytic lichens and host trees along elevation gradients: Climate change implications in mountain ranges. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplundm, J.; Roos, R.E.; Klanderud, K.; Zuijlen, K.; Lang, S.I.; Birkemoe, T. Divergent responses of functional diversity to an elevational gradient for vascular plants, bryophytes and lichens. J. Vegetat. Sci. 2022, 33, e13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthy, F.R.; Douglas, A.S.; Stefanie, D.G.; Dhanushka, W.; Hui, L.L.; Vinodhini, T. Simulated climate change impacts health, growth, photosynthesis, and reproduction of high-elevation epiphytic lichens. Ecosphere 2025, 16, e70224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, M.; Hofmann, E.; Schmull, M. Site factors determining epiphytic lichen distribution in a dieback-affected spruce-fir forest on Whiteface Mountain, New York: Microclimate. Ann. Bot. Fen. 2006, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.R. Altitudinal patterns of Stereocaulon (Lichenized Ascomycota) in China. Acta. Oecol. 2010, 36, 173–178. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, C.B.; Solhoy, T.; Gauslaa, Y.; Palmer, M.W. The elevation gradient of lichen species richness in Nepal. Lichenologist 2010, 42, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinas, C.L.; McMullin, R.T.; Rousseu, F.; Vellend, M. Diversity and assembly of lichens and bryophytes on tree trunks along a temperate to boreal elevation gradient. Oecologia 2023, 202, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdushalik, N. Universal Scientific Expedition Report of Barluk Mountain Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China; Xinjiang University Press: Urumqi, China, 2013; pp. 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A.; Wu, J.R. Lichens of Xinjiang; Science Technology & Hygiene Publishing House of Xinjiang: Urumqi, China, 1998; pp. 1–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mamatali, R.; Yong, H.Y.; Tosun, D.; Tumur, A. Diversity of macrolichen in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve, in Xinjiang, China. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 100, 02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toksun, D.; Mamatali, R.; Yong, H.Y.; Tumur, A. The macrolichens of Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve, Xinjiang Province, China. Open. J. For. 2024, 14, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamatali, R.; Imin, B.; Kahriman; Tumur, A. The diversity of crustose lichens in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, China. In Proceedings of the 2023 Science and Technology Annual Conference of the Chinese Society of Environmental Sciences, Nanchang, China, 22–23 April 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Toksun, D.; Mamatali, R.; Yong, H.Y.; Tumur, A. Species diversity of ground-dwelling macrolichens and their ecological indicator values in the Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2025, 53, 1998–2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Toksun, D.; Bahenuer, J.; Yong, H.Y.; Tumur, A. Distribution characteristics of epiphytic lichens on Populus tremula trunks in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve of Xinjiang, China. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2025, 34, 62–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tajiguli, A.; Nurbay, A.; Wang, Y.Y. Biodiversity and protection countermeasures research on Natural Reserve of Xinjiang Barluk Mountain. North. Hortic. 2011, 21, 73–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.B.; Nurbay, A. Research on wild plant resources in Barluk Mountain Natural Reserve of Xinjiang. J. Anhui. Agric. Sci. 2011, 39, 5996–5999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak, D.; Osyczka, P. Non-forest vs forest environments: The effect of habitat conditions on host tree parameters and the occurrence of associated epiphytic lichens. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 47, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.; Oran, S.; Guvenc, S.; Dalkiran, N. Analysis of the distribution of epiphytic lichens in the oriental beech (Fagus orientalis Lipsky) forests along an altitudinal gradient in Uludag mountain, bursa—Turkey. Pak. J. Bot. 2010, 42, 2661–2670. [Google Scholar]

- Orange, A.; James, P.W.; White, F.J. Microchemical Methods for the Identification of Lichens, 2nd ed.; British Lichen Society: London, England, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, M.B. Keys to Lichens of North America: Revised and Expanded; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2016; pp. 3–423. [Google Scholar]

- Cobanoglu, G.; Sevgi, O. Analysis of the distribution of epiphytic lichens on Cedrus libani in Elmali Research Forest (Antalya, Turkey). J. Environ. Biol. 2009, 2, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.L.; Yu, J.; Chen, G.Q. Ecological Data Analyses-Methods, Programs and Software; Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 160–170. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter, B.; Kappen, L.; Sancho, L.G. Seasonal variation in the carbon balance of lichens in the maritime Antarctic: Long-term measurements of photosynthetic activity in Usnea aurantiaco-atra. In Antarctic Ecosystems: Models for Wider Ecological Understanding; Davison, W., Howard-Williams, C., Broady, P., Eds.; The Caxton Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Leppik, E.; Jüriado, I. Factors important for epiphytic lichen communities in wooded meadows of Estonia. Folia. Cryptog. 2008, 44, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Büdel, B.; Scheidegger, C. Thallus morphology and anatomy. In Lichen Biology, 2nd ed.; Nash, I.T.H., Ed.; 2008; pp. 40–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pinokiyo, A.; Singh, K.P.; Singh, J.S. Diversity and distribution of lichen in relation to altitude within a protected biodiversity hot spot, north-east India. Lichenologist 2008, 40, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morando, M.; Matteucci, E.; Nascimbene, J.; Borghi, A.; Piervittori, R.; Favero-Longo, S.E. Effectiveness of aerobiological dispersal and microenvironmental requirements together influence spatial colonization patterns of lichen species on the stone cultural heritage. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P.; Martellos, S. On the ecology of sorediate lichens in Italy. Bibl. Lichenol. 2003, 86, 393–406. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, F.M. Nonvascular epiphytes in forest canopies: Worldwide distribution, abundance, and ecological roles. In Forest Canopies; Lowman, M.D., Nadkarni, N.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 353–408. [Google Scholar]

- Loppi, S.; Printsos, S.A.; Dominics, V.D. Analysis of the distribution of epiphytic lichens on Quercus pubescens along an altitudinal gradient in a mediterranean area (Tuscany, Central Italy). Isr. J. Plant Sci. 1997, 45, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldiz, M.S.; Brunet, J. Litter fall of epiphytic macrolichens in Nothofagus forest of northern Patagonia Argentina: Relation to stand age and precipitation. Austral Ecol. 2006, 31, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmor, L.; Tõrra, T.; Saag, L.; Randlane, T. Species Richness of Epiphytic Lichens in Coniferous Forests: The Effect of Canopy Openness. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 2012, 49, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Sites | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Altitude | Canopy Openness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 45°47′50″ | 82°25′20″ | 940 | 18.2 |

| Site 2 | 45°50′11″ | 82°32′17″ | 1040 | 47.8 |

| Site 3 | 45°55′43″ | 82°43′27″ | 1150 | 33.5 |

| Site 4 | 45°53′45″ | 82°45′05″ | 1250 | 30.7 |

| Site 5 | 45°52′07″ | 82°44′13″ | 1350 | 12.5 |

| Site 6 | 45°54′56″ | 82°38′02″ | 1450 | 6.8 |

| Altitude (m) | F | P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 940 | 1040 | 1150 | 1250 | 1350 | 1450 | |||

| Simpson index | 0.923 ± 0.005 | 0.940 ± 0.02 | 0.871 ± 0.007 | 0.869 ± 0.014 | 0.898 ± 0.012 | 0.698 ± 0.086 | 41.972 | <0.001 |

| Shannon–Wiener index | 2.651 ± 0.140 | 2.961 ± 0.171 | 2.222 ± 0.189 | 2.197 ± 0.147 | 2.436 ± 0.208 | 1.348 ± 0.160 | 83.259 | <0.001 |

| Evenness index | 0.886 ± 0.011 | 0.840 ± 0.022 | 0.769 ± 0.026 | 0.818 ± 0.016 | 0.817 ± 0.025 | 0.770 ± 0.034 | 25.265 | <0.001 |

| Margalef index | 3.333 ± 0.434 | 4.250 ± 0.558 | 2.294 ± 0.318 | 2.136 ± 0.535 | 2.725 ± 0.259 | 1.092 ± 0.458 | 48.258 | <0.001 |

| Altitude (m) | 940 | 1040 | 1150 | 1250 | 1350 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1040 | 0.413 | ||||

| 1150 | 0.300 | 0.424 | |||

| 1250 | 0.293 | 0.333 | 0.324 | ||

| 1350 | 0.292 | 0.351 | 0.321 | 0.380 | |

| 1450 | 0.222 | 0.339 | 0.320 | 0.250 | 0.240 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ablimit, N.; Mamatali, R.; Toksun, D.; Iqbal, M.S.; Tumur, A. Analysis of the Distribution of Epiphytic Corticolous Lichens in the Forests Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China. Diversity 2026, 18, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010002

Ablimit N, Mamatali R, Toksun D, Iqbal MS, Tumur A. Analysis of the Distribution of Epiphytic Corticolous Lichens in the Forests Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAblimit, Nasima, Reyhangul Mamatali, Dolathan Toksun, Muhammad Shahid Iqbal, and Anwar Tumur. 2026. "Analysis of the Distribution of Epiphytic Corticolous Lichens in the Forests Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China" Diversity 18, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010002

APA StyleAblimit, N., Mamatali, R., Toksun, D., Iqbal, M. S., & Tumur, A. (2026). Analysis of the Distribution of Epiphytic Corticolous Lichens in the Forests Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Barluk Mountain National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China. Diversity, 18(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010002