Abstract

The elasmobranch fauna was studied in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi, which is a mangrove-dominated inshore habitat historically reported to host a diversity of elasmobranch species. A stereo-baited remote underwater video system (Stereo-BRUVS) survey was conducted from September 2021 to August 2022 to assess the species diversity and relative abundance of elasmobranch fishes. A total of 12 elasmobranch taxa were encountered during the study, consisting of five rays (Myliobatiformes), four sharks (Selachii), two wedgefish and one guitarfish (Rhinopristiformes). The area was dominated by honeycomb-patterned rays in the genus Himantura and the Critically Endangered Arabic whipray Maculabatis arabica. Since Himantura uarnak and H. leoparda could not be reliably distinguished from footage, all sex- and size-based results are reported for a combined Himantura species complex and should be interpreted cautiously. Furthermore, the broad size range of individuals found in the area highlights its importance to all life stages of these taxa. This underlines the need for a conservation strategy to avoid detrimental changes to the elasmobranch fauna due to ongoing coastal development.

1. Introduction

Populations of elasmobranch fishes (sharks, skates, and rays) have undergone dramatic declines on a global scale in recent decades [1,2]. These animals face numerous threats ranging from direct and indirect capture in fisheries to habitat degradation and loss [3,4]. Although industrial commercial fisheries have the greatest impact on elasmobranch populations [5], artisanal fisheries and anthropogenic activities on a local scale are also of concern [6,7,8]. A high diversity of elasmobranch species has been reported from the Persian (Arabian) Gulf, herein ‘the Gulf’. For instance, Hsu et al. [9] reported the presence of 47 elasmobranch species in the western Gulf, highlighting the region’s significant biodiversity. Similarly, Navarro et al. [10] investigated the trophic ecology of 33 elasmobranch species in the Gulf and Gulf of Oman, emphasizing the ecological importance of these areas. Despite these contributions, contemporary biological and ecological data remain limited, underscoring the need for further research to assess the current status of elasmobranch populations in the region [9,11,12].

Fishery management in the Gulf region is complicated by numerous national jurisdictions, and existing regulations may not be based on relevant biological or ecological data due to little or no data availability [12]. Thus, many elasmobranch species within the Gulf are considered threatened, critically endangered, or data-deficient by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [13]. Moreover, most accessible data are fishery-dependent and based solely on landing-site surveys [6,11,14,15,16]. Consequently, only species of commercial interest are monitored; therefore, acquiring fishery-independent data is crucial.

The Gulf is recognised to reach the highest marine water temperature globally [17], and models predict a substantial decline in fishery catches in the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) due to increased salinity and temperature and decreased dissolved oxygen, driven by climate change [18]. Contemporary data investigating species biology and ecology are needed to provide baseline knowledge that enables effective conservation management and the detection of long-term changes over time.

Stereo-baited remote underwater video systems (Stereo-BRUVS) offer a non-invasive and non-destructive method for data collection, suitable for cases when species are endangered and physical capture is not essential [19,20,21]. BRUVS use bait, generally a locally sourced sardine type [22], to attract carnivorous fishes in the area. This technique has been successfully utilised in studies focusing on relative abundance, size distribution, and species diversity [23,24,25,26].

Considering the rapid rate of coastal development in the U.A.E., shallow coastal areas are of particular concern for conservation purposes [27]. Moreover, except for one extensive BRUVS survey investigating the open waters within the Gulf conducted by Jabado et al. [28] little research has been performed on the marine biodiversity in this region. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to assess the current elasmobranch fauna in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi (U.A.E.). This is an extensive mangrove-dominated area to the east of Abu Dhabi city, which is known to be utilised by at least two critically endangered elasmobranch species [29]. Moreover, historic accounts of the area’s elasmobranch fauna further indicate that a number of ray and shark species were commonly encountered there (J. Al Romaithi, pers. com., 2022). The same source also reported that juvenile sicklefin lemon sharks Negaprion acutidens (Rüppel, 1837) were particularly common.

2. Materials and Methods

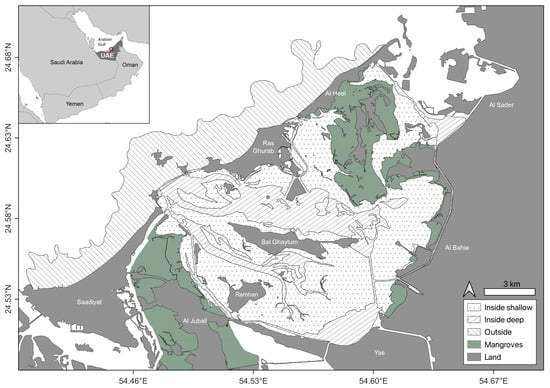

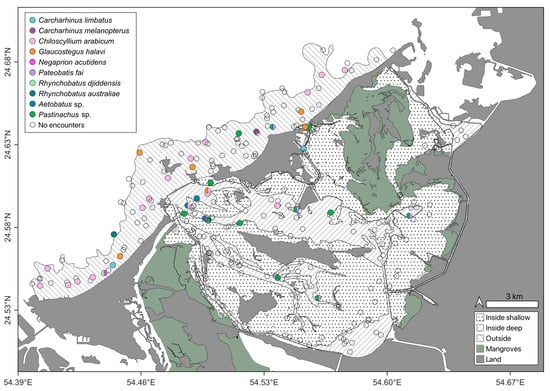

This study focused on the wider Khor Faridah region, a 137 km2 area characterised by sheltered mangrove forests and seagrass meadows interspersed with sandflats and channels that connect to the open waters of the Gulf (Figure 1). Based on these characteristics, the study area was divided into three strata, i.e., the inside shallow ‘IS’ (0 to 3 m depth), the inside deep ‘ID’ (>3 m depth) and the area along the coastline outside ‘OU’ (0 to 10 m).

Figure 1.

Study area in the Khor Faridah region on the eastern side of Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates). Sampling strata are illustrated according to pattern.

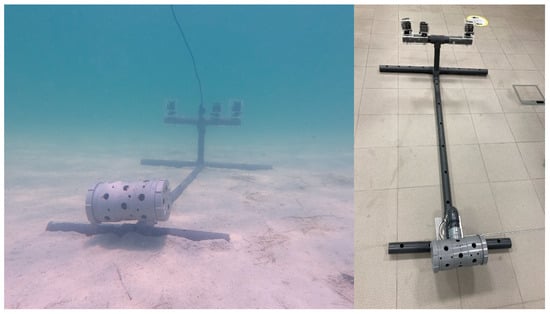

Nine Stereo-BRUVSs were constructed, each with two Lightdow 4k cameras (1920 × 1080 resolution and 60FPS) 50 cm apart facing the bait canister. The frame was also equipped with a third camera (same manufacturer and settings) facing the opposite direction to provide a nearly 360° window of observation (Figure 2). The cameras were calibrated using Cal-Software v3.23 and a 1000 × 1000 mm calibration cube from SeaGis Pty Ltd. (Bacchus Marsh, VIC 3340, Australia). The bait for each deployment was 1 kg of blended and chopped Indian oil sardine (Sardinella longiceps) procured from local fish markets.

Figure 2.

Stereo-BRUVS design that was used for an elasmobranch survey in the Khor Faridah region in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. The frame was equipped with two cameras placed 500 mm apart on the base bar facing the bait box at a five-degree inward angle. A third camera facing the opposite side provided a window of observation of approximately 360°.

A stratified sampling approach was adopted based on the area of each stratum, wherein there were 18 monthly deployments in stratum IS, nine deployments in stratum ID and nine deployments in stratum OU, providing a total of 432 deployments during daylight hours across the entire study area and project duration (September 2021 to August 2022). Each deployment lasted for 105 min based to the camera battery life, with the deployment locations randomly generated in QGIS version 3.24 (Open-Source Geospatial Foundation OSGeo, Beaverton, OR, USA). Figure 3 provides an example frame from the stereo-BRUVS footage, illustrating the typical field of view and image quality used for species identification and measurements. Video footage was analysed with EventMeasure software v5.22 from SeaGIS. The MaxN approach to estimate relative abundance was used [30,31]; however, this measure was adapted if individuals were determined to be distinct animals entering the window of observation at different times based on obvious size differences, sex differences, or body markings. In such cases, observations were treated as separate records [32]. Upon video analysis the most dominant habitat type in the field of observation was documented and assigned to the deployment ID. Habitat type was divided into five categories; ‘Seagrass’ (dominated by seagrass meadows and macro algae, ‘Sand’ (bare sand, interspersed with little complexity), ‘Patch reef’ (isolated coral structures surrounded by rubble or sand), ‘Mud flats’ (soft, fine-grained sediment dominated by silt and clay), ‘Rocky reef’ (rocky structure that provides relief and functions ecologically like a reef, without living corals).

Figure 3.

Representative image of a stereo-BRUVS deployment in the Khor Faridah region, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, illustrating a Maculabatis arabica specimen.

Habitat composition was summarised using the proportion of deployments associated with each habitat type within each stratum. To quantify compositional dissimilarity among strata, we applied the Bray–Curtis index to deployment-level habitat type data. Pairwise dissimilarities were calculated among strata, and their significance was tested using a Permanova-style permutation test (999 iterations), in which strata labels were randomly reassigned across deployments to generate a null distribution of dissimilarities.

The relative abundance of animals was represented as observation per unit effort (OPUE) [33] and reported as the number of animals per hour. The observed individuals were identified to species, following Ebert et al. [34] and Last et al. [35]. Within the study area under consideration, honeycomb-patterned rays in the genus Himantura likely encompass at least two species, i.e., the coach whipray Himantura uarnak (Gmelin, 1789) and the leopard whipray Himantura leoparda Manjaji-Matsumoto & Last, 2008. Visual distinction of these species is highly unreliable in juveniles and commonly problematic even in adults [36,37]. Consequently, the analysis treated these observations as a single taxon, namely the Himantura complex.

Sex was determined based on the presence or absence of claspers, and size was estimated using the Eventmeasure software v5.22. In the case of sharks and shark-like rays, the total length (LT) is reported, and in the case of rays, the disc width (WD) is reported. Moreover, maximum visibility was measured at each deployment using the Eventmeasure software v5.22. Using this approach, the furthest object clearly visible was marked on both camera screens and the distance between the base bar and the selected point was measured to the nearest cm.

Immediately before each deployment, water depth was measured using a handheld depth sounder (Vexilar Inc. LP8-1, Bloomington, MN, USA). The water temperature was measured at the midpoint of the water column using a multiparameter meter (model HI98194, Hanna Instruments Inc., Woonsocket, RI 02895, USA). Tidal condition was also observed and noted as flood, ebb, or slack.

The relationship between water temperature and observation per unit effort (OPUE) using Pearson’s correlation. Species diversity of elasmobranchs across deployments were calculated using the Simpson’s diversity index (1 − D) and the effective number (reciprocal of the Simpson’s Index), representing the number of equally common species required to achieve the observed value of the Simpson diversity. The index was first calculated across all deployments combined (overall diversity), and then separately within each stratum and habitat type.

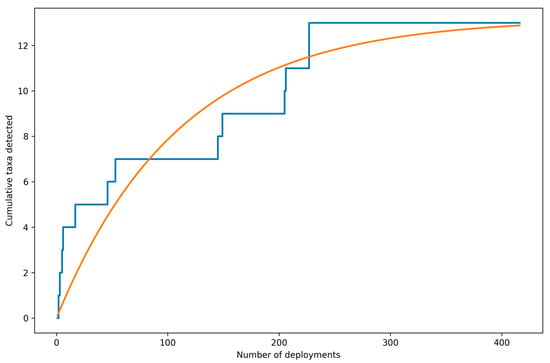

To visualize sampling completeness, a species (taxon) accumulation curve was constructed using each stereo-BRUVS deployment as a sampling unit. For each deployment, taxa were treated as incidence data (presence/absence), such that a taxon was counted once per deployment regardless of the number of individuals observed.

All statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi version 2.3.21.0 (The Jamovi project 2022, Sydney, Australia). Data were first tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When data did not conform to normal distributions or homogeneity of variance, non-parametric alternatives were applied. Specifically, Mann–Whitney U tests were used for comparisons between two groups, while Kruskal–Wallis tests were employed for comparisons among more than two groups. When Kruskal–Wallis results were significant, appropriate post hoc multiple comparisons (Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Flinger) were conducted to identify which groups differed. These approaches were chosen because they are robust to non-normal distributions and small or uneven sample sizes, which are common in BRUVS survey data.

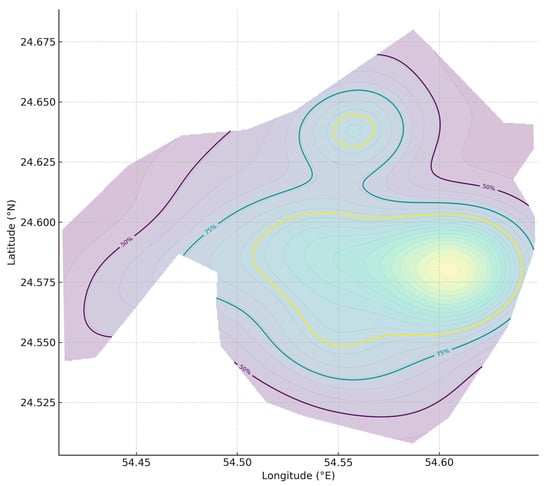

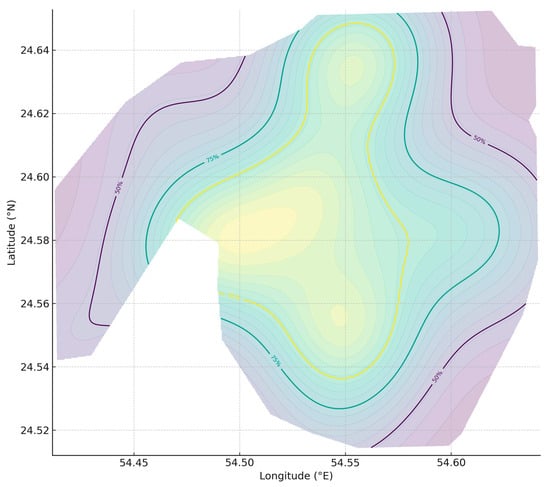

Spatial use patterns were examined with kernel density estimation (KDE), using deployment coordinates and occurrence per unit effort (OPUE, individuals/h) as weights. KDEs were calculated in UTM Zone 40N (EPSG: 32640) on 400–600 cell grids with a Gaussian kernel and bandwidth selected via Scott’s rule. Density surfaces were transformed back to geographic coordinates (EPSG: 4326) and clipped to the Khor Faridah study polygon. Utilization distribution (UD) contours at 50%, 75%, and 95% cumulative probability were extracted to delineate core and broader areas of use.

All means are reported ± standard deviation (SD) and medians are reported with interquartile range (IQR). All graphs were constructed using SigmaPlot version 11.0 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA 94303, USA), and maps were generated using QGIS version 3.24 (Open-Source Geospatial Foundation OSGeo, Beaverton, Oregon, USA).

3. Results

In total, 432 Stereo-BRUVS were deployed over the course of the study. Of these, 416 produced usable footage, and the remaining 16 experienced either poor visibility conditions or camera malfunctions. This resulted in 99 ID, 211 IS, and 106 OU deployments. When the area of each stratum is considered, this effort yielded 2.9 deployments/km2 in the ID, 3.1 deployments/km2 in the IS and 3.2 deployments/km2 in the OU stratum. Although the deployment duration was 105 min, variable camera battery life resulted in a mean deployment time per Stereo-BRUV of 104.95 with a standard deviation of 2.46 min (ID), 104.19 with a standard deviation of 3.71 min (IS) and 104.41 with a standard deviation of 4.87 min (OU). The deployment duration was not found to differ significantly between the three strata (one–way ANOVA, n = 416, p > 0.05). Although the amount of bait remaining at the end of the deployment was variable, there was always at least some bait remaining, suggesting that the BRUVS were fishing continually throughout the deployment.

Habitat composition differed clearly among strata, where both inside strata, IS and ID, were dominated by Seagrass habitat type, followed by Sand and the OU was dominated by the habitat type Sand with over 75% of deployments (Table 1). These proportional differences in habitat type among strata were highly significant (χ2 = 103.01, df = 8, p < 0.001). Pairwise post hoc χ2 tests confirmed that habitat composition differed significantly between all strata. Inside shallow sites differed from inside deep sites (χ2 = 1957.0, df = 4, p < 0.001), while both inside strata also differed strongly from the outside stratum (inside deep vs. outside: χ2 = 4471.9, df = 4, p < 0.001; inside shallow vs. outside: χ2 = 4177.9, df = 4, p < 0.001). These results indicate that each stratum was compositionally distinct in terms of relative habitat representation.

Table 1.

Proportion of Stereo-BRUVS deployments (%) by habitat type within each strata, namely Seagrass, Mud flat, Patch reef, Rocky reef and Sand. Survey was conducted in the Khor Fardiah region, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

The maximum visibility among deployments varied between 1.2–11.8 m with a median of 3.2 m (IQR = 1.8 m). Despite the wide range in maximum visibility, no correlation between maximum visibility and OPUE was found (Spearman rank correlation, n = 407, p > 0.05). The same was true for the tidal condition; no significant difference was found between the flood and ebb tides in relation to the OPUE (Mann–Whitney U-test, n = 399, p > 0.05).

Water temperature varied throughout this study, with a median temperature of 29.0 °C ((IQR): IS = 9.5 °C, ID = 9.0 °C, OU = 8.8 °C) in all three strata; however, IS reported the highest and lowest water temperatures at 38.9 °C and 16.3 °C, respectively. While the data record a wide thermal range among different times of year across the study area, no significant difference in temperature among strata nor habitat types was found (one–way ANOVA = 2.30, df = 2, p > 0.05, in all cases).

Elasmobranchs were encountered on 50.8% of deployments, with the number of individuals observed per deployment ranging from one to eight. In total, 383 elasmobranch encounters were recorded, representing 12 nominal species. This consisted of five ray species (Myliobatiformes), four shark species (Selachii), two wedgefish species, and one guitarfish species (Rhinopristiformes). However, 16 of the 383 encounters were rays that could not be identified beyond family (i.e., Dasyatidae) owing to the distance from the camera.

Patterns of species diversity reflect a Simpson diversity index of 1 − D = 0.50, with an effective number of two, indicating a community dominated by a few common taxa. Strata-level analyses revealed a clear spatial pattern. The IS had the lowest diversity (Simpson’s index 1 − D = 0.38; effective species ≈ 1.6), while ID were moderately diverse (1 − D = 0.53; ≈2.1 effective species), whereas the OU stratum supported the highest diversity (1 − D = 0.73; ≈3.7 effective species), reflecting a greater richness (11 species) among taxa.

When partitioned by habitat type, diversity varied considerably. Patch reef and Rocky reef habitats exhibited the highest Simpson values (1 − D = 0.83 and 1 − D = 0.81, respectively), with effective species numbers of ~6.0 and ~5.2. Bray–Curtis dissimilarity values based on habitat composition supported these trends. The two inside strata were relatively similar (0.22 dissimilarity), whereas outside sites differed substantially from both inside deep (BCdissimilarity = 0.46) and inside shallow (BCdissimilarity = 0.43). Pairwise Permanova-style permutation tests confirmed that these differences were statistically significant between outside and both inside strata (p = 0.001), while the difference between inside deep and inside shallow was not significant (p = 0.109).

The species assemblage was strongly dominated by rays, particularly the Himantura species complex and Maculabatis arabica was first described in 2016 [38] with sharks and wedgefishes encountered infrequently (Table 2). Overall IS documented the highest overall OPUE with 0.65 Ind/h, followed by OU with 0.5 Ind/h, while the ID stratum recorded the lowest OPUE at 0.42 ind./h. Patterns of relative abundance varied by stratum, with Himantura and M. arabica more common in IS and Chiloscyllium arabicum Gubanov, 1980 more common in OU. While the outside stratum was more monotonous in habitat composition, with over 75% represented by plain sand, it nevertheless recorded the highest species richness among strata, encountering all taxa except for Carcharhinus melanopterus (Quoy & Gaimard 1824). However, low encounter rates for most taxa limited interpretation of fine-scale spatial preferences across the study area.

Table 2.

Species relative abundance expressed as observation per unit effort (individuals/h) overall and per stratum in the Khor Fardiah region, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Moreover, temperature did not show any association with overall OPUE or species richness (Spearman rank correlation; OPUE: ρ = 0.11, p > 0.05; species richness: ρ = 0.06, p > 0.05). Species-specific analyses likewise revealed no significant relationships between OPUE and temperature for either Himantura species complex (n = 145, ρ = −0.02, p > 0.05) or M. arabica (n = 53, ρ = −0.19, p > 0.05).

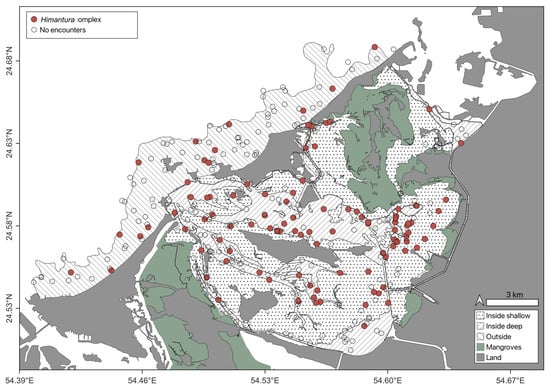

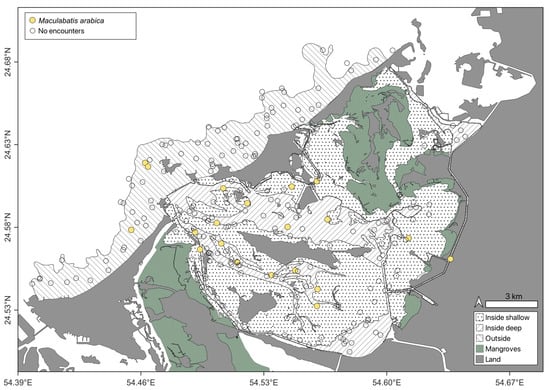

Observations were dominated by the Himantura complex, the taxon was encountered throughout the study area (Figure 4) and there was no significant difference in OPUE between strata (Kruskal–Wallis, n = 250, p > 0.05). The depth distribution of this species complex was 0.5–8.8 m with a median depth of 1.5 m (IQR = 2.1 m). The second most abundant species, M. arabica displayed a similarly broad spatial distribution as the Himantura complex, and its abundance did not differ between strata (Kruskal–Wallis, n = 416, p > 0.05). However, it was encountered in a slightly narrower depth range (0.5–6.0 m) than Himantura, and a shallower median depth of 1.25 m (IQR = 1.73 m). Notably, most encounters with this species occurred in the vicinity of deeper channels (Figure 5). All other species were encountered considerably less frequently than Himantura and M. arabica (Table 2). Although C. arabicum was moderately abundant, its spatial distribution was mostly limited to the OU stratum (Figure 6), with depths ranging from 1.6 m 5.9 m. The spatial distributions and depth records of the remaining species were variable (Figure 6 and Table 3); however, they were encountered too infrequently to infer any trend.

Figure 4.

Himantura spp. encountered on Stereo-BRUVS deployed in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi. Sampling strata are illustrated according to pattern, and deployments with an encounter highlighted by colour red.

Figure 5.

Maculabatis arabica encountered on Stereo-BRUVS deployed in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi. Sampling strata are illustrated according to pattern, and deployments with an encounter highlighted by colour yellow.

Figure 6.

Infrequently encountered elasmobranch species on Stereo-BRUVS deployed in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi. Sampling strata are illustrated according to pattern, and species are differentiated by colour.

Table 3.

Sex ratio, size, represented as disc width (WD) or total length (LT), and depth range for less abundant species within the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

The species accumulation curve increased rapidly during early deployments and then approached an asymptote, indicating diminishing returns in additional taxa with increasing effort. Across the full dataset a total of 13 taxa were detected. All taxa had been encountered by approximately deployment 227 (≈55% of deployments), after which the curve remained flat, consistent with most taxa being detected relatively early and a small number of rare taxa requiring additional sampling to encounter (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Species accumulation curve based on the observed sampling order of stereo-BRUVS deployments across the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi. The step curve shows the cumulative number of unique taxa detected as deployments are added sequentially. A nonlinear saturating trend line is overlaid displaying the approach to an asymptote. Across 416 deployments, 13 taxa were detected, with all taxa first observed by approximately deployment 227.

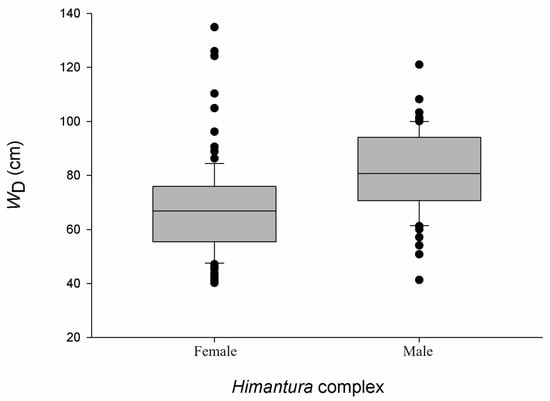

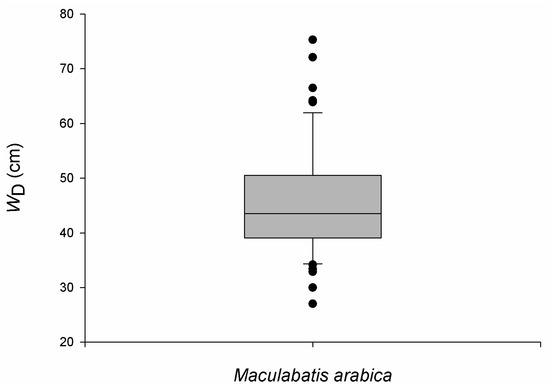

Of the 250 Himantura encounters, it was possible to estimate the size of 225 individuals and determine the sex of 167 individuals. Because H. uarnak and H. leoparda could not be reliably distinguished, all sex- and size-based results are reported for a combined Himantura species complex and should be interpreted cautiously This provided a sex ratio of 1:6 (male:female). Overall, size ranged from 40.22 cm to 134.91 cm WD, and although females displayed a greater size range than males, the latter tended to be larger (Mann–Whitney U-test, n = 167, p < 0.01) (Figure 8). A Kruskal–Wallis test determined that the median size differed between strata (n = 225, p < 0.01), but the difference was limited to between the IS and OU strata (Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Flinger, n = 182, p < 0.01). Moreover, a positive correlation was found between size and depth (Spearman rank correlation, n = 225, p < 0.05), with larger individuals occurring in deeper water. Of the 64 M. arabica individuals encountered, it was possible to estimate the size of 54 individuals and assign sex to 45 individuals. This provided a sex ratio of 14:1 in favour of females. The three males were 51 cm, 48 cm, 41 cm WD, while females ranged from 27 cm to 75 cm WD with a median size of 46.30 cm (IQR = 11.0) (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Size distribution of Himantura spp. observed in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi. Size is reported as disc width (WD), and boxplots illustrate median, interquartiles and outliers. For males n = 60 and for females n = 96.

Figure 9.

Size distribution of Maculabatis arabica observed in the Khor Faridah region of Abu Dhabi. Size is reported as disc width (WD), and boxplots illustrate median, interquartiles and outliers. Sexes are not presented separately as only three males were encountered during the study. Sexes combined, n = 54.

Both, the Himantura species complex and M. arabica showed a distinct habitat association (Table 4). The Himantura species complex was recorded most frequently in Seagrass habitats (0.89 encounter per deployment), but also showed notable occurrence on sand (0.42) and Rocky Reef (0.30). In contrast, M. arabica was more restricted, with its highest relative occurrence in Seagrass (0.21 encounter per deployment) and much lower values across other habitats (≤0.15). A Chi-square test of independence confirmed that habitat use differed significantly among habitats for both species (Himantura species complex: χ2 = 187.4, df = 4, p < 0.001; M. arabica: χ2 = 41.6, df = 4, p < 0.001), indicating non-random distributions and a strong association with Seagrass habitats. Further analysis on their spatial ecology using Kernel density analysis revealed that both taxa show clear habitat preference. Rays of the Himantura species complex were broadly distributed across the study area, with high densities in inshore channels and seagrass beds but extending into sandflats and outer lagoon habitats (Figure 10). Although both mature male and female Himantura were observed, the number of individuals was insufficient to conduct robust statistical tests of sexual segregation. In contrast, M. arabica was more restricted, with core areas concentrated in shallow channels and mangrove-fringed seagrass, and little use of open sand (Figure 11). Interestingly, Himantura are found more in shallow areas inside, whereas the individuals of M. arabica, tend to be on seagrass habitats but in vicinity of deeper channels throughout the study area. Other species were encountered to less in number to interfere any trends of their spatial distribution and habitat preference (Table 4).

Table 4.

Encounters per deployment for each different habitat type, by species recorded during a Stereo-BRUVS survey in the Khor Faridah region, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Figure 10.

Himantura species complex utilization distribution (UD). Kernel density estimate (KDE) of OPUE (individuals per hour) for Himantura species complex across the Khor Faridah, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, shown as 50%, 75%, and 95% utilization isopleths. Density reflects relative encounter intensity, not absolute counts.

Figure 11.

Maculabatis arabica utilization distribution (UD). Kernel density estimate (KDE) of OPUE for Maculabatis arabica across the Khor Faridah, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, shown as 50%, 75%, and 95% utilization isopleths. Density reflects relative encounter intensity, not absolute counts.

All 23 C. arabicum were successfully sexed and measured. The species had a mean LT of 62.41 cm (SD = 5.82 cm) and a sex ratio of 1.3:1 (Female:Male). The remaining species encountered in the survey were fewer in number (Table 3). The three Myliobatiformes, Aetobatus ocellatus (Kuhl, 1823), Pastinachus sp., and Pateobatis fai (Jordan & Seale, 1906), were observed infrequently, with three, eight, and four encounters, respectively (Table 3). Similarly, the other three shark species Negaprion acutidens (Rüppell 1837), Carcharhinus limbatus (Müller & Henle, 1839), and C. melanopterus were observed in small numbers; one, one and two individuals, respectively. Of the total encounters, 12.9% could not be measured successfully; this was the case when encounters were only made on the back camera, or when one of the front cameras did not operate correctly.

4. Discussion

All of the elasmobranch species encountered in this study are known to occur in the Arabian Gulf and have been previously reported in U.A.E. waters [11,16,29,39].

The study area was dominated by batoid species, with few small-bodied carcharhinid shark encounters. This contrasts with local ecological knowledge from a retired fisherman active in the region during the 1970s/1980s (J. Al Romaithi, pers. com., 2022), who reported regular encounters with a broader assemblage, including sicklefin lemon shark Negaprion acutidens (Rüppell, 1837), Arabian carpetshark Chiloscyllium arabicum Gubanov, 1980, spot-tail shark Carcharhinus sorrah (Valenciennes, 1839), halavi guitarfish Glaucostegus halavi (Fabricius, 1775), wedgefish Rhynchobatus spp., leopard-patterned whiprays Himantura spp., cowtail rays Pastinachus spp., and green sawfish Pristis zijsron Bleeker, 1851. Moreover, the account described the presence of multiple size classes across rays, guitarfish and sharks, consistent with a range of life stages, whereas bull/pigeye sharks Carcharhinus leucas (Valenciennes, 1839) and C. amboinensis (Müller & Henle, 1839) were mentioned only as juveniles. However, apart from two wedgefish individuals, no large-bodied elasmobranchs were encountered in this study.

The diversity indices calculated in this study reflect these patterns, with moderate species richness but relatively low evenness, as assemblages were dominated by a few common batoid taxa. This skewed community structure is consistent with other reports from the Arabian Gulf, where elasmobranch assemblages are increasingly characterised by rays rather than sharks [9,40]. The absence of large-bodied sharks and shark-like rays in our records, despite their historical presence, highlights how decades of intense and largely unmanaged fishing pressure have reshaped community composition, leading to present-day diversity deficits that are masked by the relative abundance of smaller, more resilient species.

Although the U.A.E. developed a national plan of action for sharks in 2018 [41] and implemented some fishery management measures, fisheries in the preceding decades were largely unregulated [12,42]. Large-bodied sharks and shark-like rays are especially targeted because of the high commercial value of their fins in the export market [13,16,43]. Indeed, the U.A.E. ranked fifth globally in total reported fin exports to Hong Kong in 2010 [1], with this trade consisting of both locally sourced and reexported fins. Additionally, there has been considerable coastal development in the U.A.E. over the past five decades, resulting in large alterations in coastal habitats [44]. It is possible that the assemblage of species altered over time and large bodied elasmobranchs declined in the area.

The most commonly encountered taxon during this study was Himantura but, unfortunately, it was not possible to identify these individuals to species. Previous surveys within the study area have confirmed the presence of both H. leoparda and H. uarnak [29]; therefore, it is highly likely that the observations included these two species. Further dedicated studies are needed to investigate the relative abundance of H. leoparda and H. uarnak in U.A.E. waters. However, it is essential that any such efforts include molecular data, as colour patterns are not a reliable differentiator of these species [35,37].

Bearing this in mind, it is difficult to assign any importance to the sex ratio observed during the present study, as either species may have been represented by a single sex or a combination of sexes. Nevertheless, Himantura leoparda and Himantura uarnak reach sexual maturity at broadly similar sizes, i.e., 75 and 83 cm WD, respectively [45,46,47], indicating that the Himantura observed during the present study were a mix of mature and immature individuals. Indeed, a large proportion of females, in particular, were likely immature. That being said, numerous individuals were encountered during this study that were consistent with the maximum sizes reported for H. leoparda and H. uarnak [16,46]. Taken together, these observations suggest that the Khor Faridah region is utilised by all life stages of this taxon.

M. arabica, but little is known about its biology and ecology. Although its geographic range was initially reported to be limited to the west coast of India [35], the species has since been confirmed within the Arabian Gulf [29,48]. Of particular note is the fact that the species grows larger than previously thought, and it exhibits pronounced sexual segregation, with females dominating the nearshore environment. It is worth noting that Al Hameli et al. [29] recorded a higher relative abundance of Glaucostegus halavi (Fabricius, 1775) in the study area than in the present Stereo-BRUVS survey. This discrepancy between the two studies requires further attention but suggests that the use of a multiple-survey-technique approach can be advantageous when investigating relative abundance or species diversity.

The size at which sexual maturity is attained in M. arabica remains unknown. However, a very broad size range was observed here and by Al Hameli et al. [29] suggesting the presence of mature and immature females in the area. Females with notably distended abdomens during the summer months, including some with well-developed and fully pigmented tails protruding from the cloaca (S. Bruns pers. obs., 2022) confirmed the presence of pregnant females in the study area and suggested that parturition may occur at this time of the year. Future studies should aim to survey a wider geographic area that extends further from the shore and incorporate deeper waters to elucidate the demographics of male M. arabica.

The only other species encountered during the present study in sufficient numbers to provide any information about sexual demographics was C. arabicum, in which both sexes were equally represented. The size range in both sexes during this study and published records on size at maturity indicate that a mix of mature and immature individuals was present [49]. Data from previous studies elsewhere suggest that most of the G. halavi, Rhynchobatus djiddensis (Forsskål, 1775), and Rhynchobatus sp. individuals encountered here were also sexually mature [35,50,51], whereas C. melanopterus, C. limbatus, N. acutidens, Pastinachus sp., and P. fai were more likely to be immature [47,52,53,54]. While comparisons with other regions are limited due to the unique environmental conditions of the Gulf, this study provides baseline data critical for understanding regional diversity patterns. For instance, the diversity observed here contrasts with the lower abundance of elasmobranchs recorded in open waters of the Gulf [28], and highlights the importance of shallow coastal habitats.

Coastal inshore areas play a critical role in the ecology and biology of various elasmobranch species [27]. However, rapid coastal development and extreme environmental conditions around the Gulf has introduced numerous anthropogenic stressors coupled with rapid coastal development in Abu Dhabi, significantly impact habitat quality and elasmobranch populations. Previous studies [18,44] have demonstrated that such anthropogenic pressures contribute to habitat fragmentation and biodiversity loss, underscoring the importance of conserving areas that appear to provide juvenile habitat consistent with nursery function like the Khor Faridah region. Moreover, such activities have been shown to adversely affect elasmobranch biology and ecology, particularly their reproductive processes elsewhere [55,56,57]. This stresses the concern that future coastal development in the study area will have severe implications for the elasmobranch communities present.

Studies from elsewhere have shown that reduced shark populations can benefit ray population growth due to a release from predation pressure [58,59,60]. This may help to explain the relatively high abundances of rays during this study, although their low commercial value and the lack of a targeted fishery is also important to consider. Similarly, the low commercial value of C. arabicum is likely to have contributed to its abundance in the study area and throughout the Gulf [28,39].

The spatial characteristics of species occurrence and abundance did not follow any clear trends for the majority of the encountered taxa. Although some species were limited to certain areas, habitat types and depths, this is likely a reflection of their low abundance during the present study. Interestingly, despite the relatively high-water temperatures recorded during the study, no significant decline in species abundance was detected. This suggests that even under elevated thermal conditions, inshore habitats continued to be actively used by a range of species encountered during this study. Species that were sufficiently represented to investigate spatial dynamics, that is, Himantura and M. arabica, were encountered in all strata. However, both species displayed their greatest abundance in the IS, followed by the ID and OU, highlighting the importance of the sheltered inshore area of the Khor Faridah region for both species. The 95% utilization distributions highlight the habitats that function as the main activity areas for both taxa within the lagoon. These broad areas represent the extent of space used beyond the core hotspots and are ecologically important because they encompass the channels, sandflats, and seagrass beds that likely provide access to foraging resources, refuge, and movement corridors. Protecting these wider areas of use is critical, as management that focuses only on the densest core areas may overlook the habitats that support connectivity and daily movements. The apparent overlap in 95% UDs between Himantura and M. arabica further suggests that shared inshore habitats are key to sustaining both species, even though they differ in how intensively they use them. Here, especially seagrass meadows are essential to a range of batoid life stages, such, ongoing coastal development across the Gulf is a major threat to seagrass meadow loss and the inherent loss of suitable nursery habitats [61,62].

Even though seasonal fluctuations in abundance were not further analysed in this study due to the limited duration of one year, a previous study conducted by Al Hameli et al. [29] recorded the highest abundance of M. arabica during the summer and the lowest during the winter. If parturition indeed takes place during the summer, the higher abundance during this season may reflect an inshore migration of gravid females. Further studies are required to investigate this possibility and to better understand the seasonal dynamics and reproductive behaviours of this species.

In conclusion, this survey of the Khor Faridah region revealed a moderate diversity and abundance of batoid species, three of which are categorised as critically endangered by the IUCN, namely G. halavi, M. arabica and R. djiddensis [63,64,65]. The high abundance of M. arabica in this area is of particular note given the lack of knowledge about the species and its current extinction risk [63]. Coastal development in this area is ongoing, and a conservation strategy is needed to avoid detrimental changes to the elasmobranch fauna inhabiting the region. From a management perspective, these findings support prioritising the protection of shallow mangrove and seagrass habitats, as well as channel corridors that likely underpin juvenile habitat use. Particularly, actions that limit dredging and/or reclamation activities in shallow flats and channels.

Author Contributions

Fieldwork was conducted by S.B., S.A.H. and A.C.H. Data analysis was performed by S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was partially funded by United Arab Emirates University (UAEU) grant G00003663.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or vertebrate animal experimentation; all research activities were conducted in accordance with Abu Dhabi and UAE federal laws.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank UAE University for providing logistical support. Moreover, we are thankful to all the volunteers who participated in this fieldwork, as well as the Environmental Agency of Abu Dhabi, for permitting the research to be undertaken. We also thank J. Seager from SeaGis for all supports with camera calibration and setup. We are particularly grateful to Jumaa Al Romaithi, the final member of the local fishing community who fished in the area from the 1970s until 2000 and provided invaluable insights into the transformations that have occurred in the region.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dulvy, N.K.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Davidson, L.N.K.; Fordham, S.V.; Bräutigam, A.; Sant, G.; Welch, D.J. Challenges and priorities in shark and ray conservation. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R565–R572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Fowler, S.L.; Musick, J.A.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Kyne, P.M.; Harrison, L.R.; Carlson, J.K.; Davidson, L.N.; Fordham, S.V.; Francis, M.P.; et al. Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. eLife 2014, 3, e00590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, J.; Wangensteen, O.S.; Chapman, D.D.; Boussarie, G.; Buddo, D.; Guttridge, T.L.; Hertler, H.; Mouillot, D.; Vigliola, L.; Mariani, S. Environmental DNA reveals tropical shark diversity in contrasting levels of anthropogenic impact. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, D.E.; Gruber, S.H.; Franks, B.R.; Kessel, S.T.; Robertson, A.L. Effects of large-scale anthropogenic development on juvenile lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris) populations of Bimini, Bahamas. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2008, 83, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, B.; Davis, B.; Kettemer, L.; Ward-Paige, C.A.; Chapman, D.; Heithaus, M.R.; Kessel, S.T.; Gruber, S.H. Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks. Mar. Policy 2013, 40, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabado, R.W.; Al Ghais, S.M.; Hamza, W.; Henderson, A.C. The shark fishery in the United Arab Emirates: An interview based approach to assess the status of sharks. Aquat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 800–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.I. Can shark resources be harvested sustainably? A question revisited with a review of shark fisheries. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1998, 49, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward-Paige, C.A.; Worm, B. Global evaluation of shark sanctuaries. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.H.; Yacoubi, L.; Lin, Y.J.; Le Loc’h, F.; Katsanevakis, S.; Giovos, I.; Qurban, M.A.; Nazeer, Z.; Panickan, P.; Maneja, R.H.; et al. Elasmobranchs of the western Arabian Gulf: Diversity, status, and implications for conservation. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 56, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.; Rastgoo, A.R.; Giménez, J. Unravelling the trophic ecology of poorly studied and threatened elasmobranchs inhabiting the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Mar. Biol. 2024, 171, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabado, R.W.; Al Ghais, S.M.; Hamza, W.; Shivji, M.S.; Henderson, A.C. Shark diversity in the Arabian/Persian Gulf higher than previously thought: Insights based on species composition of shark landings in the United Arab Emirates. Mar. Biodivers. 2015, 45, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.B.M.; McCarthy, I.D.; Carvalho, G.R.; Peirce, R. Species, sex, size and male maturity composition of previously unreported elasmobranch landings in Kuwait, Qatar and Abu Dhabi Emirate. J. Fish. Biol. 2012, 80, 1619–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabado, R.W.; Kyne, P.M.; Pollom, R.A.; Ebert, D.A.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Ralph, G.M.; Al Dhaheri, S.S.; Akhilesh, K.V.; Ali, K.; Ali, M.H.; et al. Troubled waters: Threats and extinction risk of the sharks, rays and chimaeras of the Arabian Sea and adjacent waters. Fish Fish. 2018, 19, 1043–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.C.; Al-Oufi, H.; McIlwain, J.L. Survey, Status and Utilization of the Elasmobranch Fishery Resources of the Sultanate of Oman; Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries: Muscat, Oman, 2008.

- Henderson, A.C.; McIlwain, J.L.; Al-Oufi, H.S.; Al-Sheili, S. The Sultanate of Oman shark fishery: Species composition, seasonality and diversity. Fish. Res. 2007, 86, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.B.M. Elasmobranchs of the Persian (Arabian) Gulf: Ecology, human aspects and research priorities for their improved management. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2011, 22, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegl, B.M.; Purkis, S.J.; Al-Cibahy, A.S.; Abdel-Moati, M.A.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Present limits to heat-adaptability in corals and population-level responses to climate extremes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabnitz, C.C.; Lam, V.W.Y.; Reygondeau, G.; Teh, L.C.L.; Al-Abdulrazzak, D.; Khalfallah, M.; Pauly, D.; Palomares, M.L.D.; Zeller, D.; Cheung, W.W.L. Climate change impacts on marine biodiversity, fisheries and society in the Arabian Gulf. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappo, M.; Speare, P.; De’Ath, G. Comparison of baited remote underwater video stations (BRUVS) and prawn (shrimp) trawls for assessments of fish biodiversity in inter-reefal areas of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2004, 302, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Garcon, J.; Braccini, M.; Langlois, T.J.; Newman, S.J.; Mcauley, R.B.; Harvey, E.S. Calibration of pelagic stereo-BRUVs and scientific longline surveys for sampling sharks. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, S.K.; Fairweather, P.G.; Huveneers, C. What is Big BRUVver up to? Methods and uses of baited underwater video. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2017, 27, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, S.R.; Harvey, E.S.; Newman, S.J. Bait Effects in Sampling Coral Reef Fish Assemblages with Stereo-BRUVs. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, E.J.; Sloman, K.; Sims, D.W.; Danylchuk, A.J. Validating the use of baited remote underwater video surveys for assessing the diversity, distribution and abundance of sharks in the Bahamas. Endanger. Species Res. 2011, 13, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappo, M.; Harvey, E.; Shortis, M. Counting measuring fish with baited video techniques-an overview In Cutting-Edge Technologies in Fish and Fisheries Science; Lyle, J.M., Furlani, D.M., Buxton, C.D., Eds.; Australian Society for Fish Biology: Hobart, Australia, 2006; pp. 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, M.; Araya-Arce, T.; Chaves-Zamora, I.; Chinchilla, I.; Cambra, M. Monitoring elasmobranch assemblages in a data-poor country from the Eastern Tropical Pacific using baited remote underwater video stations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, M.; Cappo, M.; Heupel, M.R.; Tobin, A.J.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Quantifying Shark Distribution Patterns and Species-Habitat Associations: Implications of Marine Park Zoning. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knip, D.; Heupel, M.; Simpfendorfer, C. Sharks in nearshore environments: Models, importance, and consequences. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 402, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabado, R.W.; Al Hameli, S.M.; Grandcourt, E.M.; Al Dhaheri, S.S. Low abundance of sharks and rays in baited remote underwater video surveys in the Arabian Gulf. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hameli, S.; Bruns, S.; Henderson, A.C. Notable abundance of two Critically Endangered elasmobranch fishes near an area of intensive coastal development in the Arabian Gulf. Endanger. Species Res. 2024, 53, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.M.; DeMartini, E.E. Evaluation of a video camera technique for indexing abundances of juvenile pink snapper, Pristipomoides filamentosus, and other Hawaiian insular shelf fishes. Oceanogr. Lit. Rev. 1995, 9, 786. [Google Scholar]

- Priede, I.G.; Bagley, P.M.; Smith, A.; Creasey, S.; Merrett, N.R. Scavenging deep demersal fishes of the Porcupine Seabight, north-east Atlantic: Observations by baited camera, trap and trawl. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 1994, 74, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, C.S.; Chin, A.; Heupel, M.R.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Are we underestimating elasmobranch abundances on baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVS) using traditional metrics? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2018, 503, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, S.; Henderson, A. A baited remote underwater video system (BRUVS) assessment of elasmobranch diversity and abundance on the eastern Caicos Bank (Turks and Caicos Islands); an environment in transition. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2020, 103, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.A.; Dando, M. Fowler S Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Last, P.; White, W.T.; Carvalho, M.R.; de Séret, B.; Stehmann, M.F.W.; Naylor, G.J.P.; McEachran, J.D. Rays of the World; CSIRO Publishing: Hobart, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlyza, I.S.; Shen, K.N.; Solihin, D.D.; Soedharma, D.; Berrebi, P.; Borsa, P. Species boundaries in the Himantura uarnak species complex (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 66, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.C. A review of potential taxonomic barriers to the effective management of Gulf elasmobranch fisheries. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2020, 23, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjaji-Matsumoto, B.M.; Last, P.R. Two new whiprays Maculabatis arabica sp nov, M. bineeshi sp. nov. (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae), from the northern Indian Ocean. Zootaxa 2016, 4144, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, J.M.; Moore, A.B.M.; Alsaffar, A.H.; Abdul Ghaffar, A.R. The distribution, diversity and abundance of elasmobranch fishes in a modified subtropical estuarine system in Kuwait. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2016, 32, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabado, R.W.; Antonopoulou, M.; Möller, M.; Al Suweidi, A.S.; Al Suwaidi, A.M.; Mateos-Molina, D. Baited Remote Underwater Video Surveys to assess relative abundance of sharks and rays in a long standing and remote marine protected area in the Arabian Gulf. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2021, 540, 151565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. United Arab Emirates National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks; United Arab Emirates Ministry of Climate Change & Environment: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018.

- Ben-Hasan, A.; Christensen, V. Vulnerability of the marine ecosystem to climate change impacts in the Arabian Gulf—An urgent need for more research. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, e00556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.R.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Sharks Rays Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes in Sharks Rays Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2005; pp. 140–149. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1376361/sharks-rays-and-chimaeras/1990624/ (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Hamza, W.; Munawar, M. Protecting and managing the Arabian Gulf: Past, present and future. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2009, 12, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjaji-Matsumoto, B.M.; Last, P.R. Himantura leoparda sp nov a new whipray (Myliobatoidei: Dasyatidae) from the Indo-Pacific. In Descriptions of New Australian Chondrichthyans; Last, P.R., White, W.T., Pogonoski, J.J., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Hobart, Australia, 2008; pp. 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Tsikliras, A.C.; Dimarchopoulou, D. Filling in knowledge gaps: Length–weight relations of 46 uncommon sharks and rays (Elasmobranchii) in the Mediterranean Sea. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 2021, 51, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.T.; Last, P.R.; Stevens, J.D.; Yearsley, G.K.; Fahmi, D. Economically Important Sharks and Rays of Indonesia; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Al-Faisal, A.; Mutlak, F. New record of Arabic whipray, Maculabatis arabica (Elasmobranchii: Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae), from the Persian Gulf off Iraq. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 2020, 50, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajji, A.H.; Hsu, H.H.; Alkhamis, Y.A.; Alsaqufi, A.S.; Ajmal Khan, S.; Nazeer, Z. Maturity and reproduction in the Arabian carpet shark, Chiloscyllium arabicum from the Saudi Arabian waters of the Arabian Gulf. Mar. Biol. Res. 2022, 18, 361–18371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushottama, G.B.; Raje, T.; Akhilesh, K.V.; Kizhakudan, S.J.; Zacharia, P.U. Reproductive biology and diet composition of Rhynchobatus laevis (Bloch and Schneider, 1801) (Rhinopristiformes:Rhinidae) from the northern Indian Ocean. Indian J. Fish. 2020, 67, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, T.L.; Taurusman, A.A.; Nurani, T.W.; Yuwandana, D.P.; Muttaqin, E.; Yulianto, I.; Simeon, B.M. Catch composition, sex ratio, and clasper maturity of wedgefish (Rhynchobatus spp.) landed in Tegalsari, Central Java, Indonesia. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2021, 14, 3487–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Papastamatiou Yp Caselle Je Friedlander Am Lowe, C.G. Distribution, size frequency, and sex ratios of blacktip reef sharks Carcharhinus melanopterus at Palmyra Atoll: A predator-dominated ecosystem. J. Fish. Biol. 2009, 75, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.; Chin, A.; Tobin, A.; Simpfendorfer, C.; White, W. Age and growth of the common blacktip shark Carcharhinus limbatus from Indonesia, incorporating an improved approach to comparing regional population growth rates. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 37, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.T. Aspects of the biology of carcharhiniform sharks in Indonesian waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2007, 87, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giareta, E.P.; Leite, R.D.; Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Chaves, A.P.; Charvet, P.; Wosnick, N. Unveiling the batoid plight: Insights from global stranding data and future directions. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2024, 34, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskar, G.; McCallister, M.P.; Schaefer, A.M.; Ajemian, M.J. Elasmobranch community dynamics in Florida’s southern Indian River Lagoon. Estuaries Coasts 2021, 44, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, C.R.; Gervais, C.R.; Johnson, M.S.; Vance, S.; Rosa, R.; Mandelman, J.W.; Rummer, J.L. Anthropogenic stressors influence reproduction and development in elasmobranch fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2020, 30, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.N.; Bizzarro, J.J.; Clark, B.; Underwood, C.J.; Johanson, Z. Large batoid fishes frequently consume stingrays despite skeletal damage. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucifora, L.O.; García, V.B.; Menni, R.C.; Escalante, A.H.; Hozbor, N.M. Effects of body size, age and maturity stage on diet in a large shark: Ecological and applied implications. Ecol. Res. 2009, 24, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, C.S.; Heupel, M.R.; Moore, S.K.; Chin, A.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. When sharks are away, rays will play: Effects of top predator removal in coral reef ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2020, 641, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, H.A.; Abdulla, K.H. Coastal dredging and reclamation in the Arabian Gulf: Impacts and management. In Oceanographic and Marine Environmental Studies Around the Arabian Peninsula; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Molina, D.; Bejarano, I.; Pittman, S.J.; Möller, M.; Antonopoulou, M.; Jabado, R.W. Coastal lagoons in the United Arab Emirates serve as critical habitats for globally threatened marine megafauna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 200, 116–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Bineesh, K.; Owfi, F.; Fernando, D.; Moore, A.B.M.; Ali, K. Maculabatis arabica Red List Status. In IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyne, P.M.; Gledhill, K.; Jabado, R.W. Rhynchobatus djiddensis. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyne, P.M.; Jabado, R.W. Glaucostegus halavi. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.