Abstract

Lichens, symbiotic associations between fungi and photobionts, are essential and sensitive bioindicators of environmental change. Despite their resilience, lichens face increasing threats from air pollution, land-use change, unsustainable harvesting, and climate change. This study presents a bibliometric analysis of global research on lichen threats between 1981 and 2024, using data from Scopus and Web of Science, combined with an additional analysis based on the database Recent Literature on Lichens (RLL). A total of 319 research publications were analyzed through VOSviewer (version 1.6.20)and Biblioshiny (R core team version 4.5.2) to assess temporal trends, thematic evolution, authorship, and geographical distribution of affiliations, and 1354 publications from RLL were studied for frequent authors and geographical distribution of study sites. Results show that research output was initially dominated by air pollution studies (1981–2004) but shifted after 2005 toward conservation and climate change impacts, with a sharp increase after 2017. North America and a few European countries led in scientific production, while biodiversity-rich regions in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia remained underrepresented. Despite increasing publication trends, collaboration remains moderate (23% international co-authorship), and many threatened species remain unassessed. Recovery measures emphasize habitat protection, improved forest management, pollution control, integration of lichens into global biodiversity frameworks, and enhanced international collaboration. This study provides a systematic overview of how lichen conservation research has evolved, suggesting strategies for decelerating lichen diversity loss under accelerating global change.

1. Introduction

Lichens are a self-sustaining mutualistic relationship between a mycobiont (fungi) and one or more extracellularly existing photobiont (algae or cyanobacteria) that also involves an indefinite number of other microorganisms [1]. They colonize a wide range of substrates, including bark, rocks, soil, leaves of trees, fronds of fern trees in the tropics, or various anthropogenic substrates. They are abundant across diverse ecosystems, from polar tundra to tropical forests and from sea level to high elevations in mountains well above the timberline or even the tree line [2,3]. Lichens contribute significantly to ecosystem functioning [4]. For instance, they provide famine food for wildlife—such as caribou and reindeer—and habitat for small invertebrates [5,6].

They are crucial bioindicators of environmental pollution due to their physiological sensitivity [7,8]. While vascular plants have tissues and organs for water uptake and other functions, the thalline structure of lichens allows the direct uptake of atmospheric air and water over the entire thallus surface, resulting in a direct interaction with air quality and various environmental factors [5].

Despite their resilience to desiccation and temperature extremes, lichens remain vulnerable to stressors. Their diversity in photobionts and the presence of secondary metabolites attribute to their survival and colonization on harsh environments such as deserts, polar regions or temperate semi-arid sandy grassland vegetation, which are scarcely occupied by other organisms [9,10]. The poikilohydric nature [11] makes them sensitive to climate change and human pressure, which calls for conserving their diverse species [12]. The lichen thallus is poikilohydric, meaning the lack of a hydrophobic outer layer (and vascular system like that of the higher plants), thus lichens cannot regulate their own water balance. Their internal hydration depends entirely on the environment. This ‘poikilohydric nature’ allows the lichen to safely dry out (dehydrate) when water is scarce and quickly resume normal functions as soon as moisture returns (hydrate).

Worldwide, lichens are increasingly exposed to environmental pressures, such as air pollution, habitat loss, over harvesting, land-use changes, and climate change [8,13,14]. Heavy industrial emissions have led to the disappearance of many species from polluted regions, while nitrogen enrichment and ozone gases continue to endanger sensitive lichen taxa [15]. The loss of forests, urban expansion, and other land-use changes further reduce the availability of suitable habitats and substrates. Harvesting for dyes, medicines, crafts, and commercial purposes has led to a decrease in the population of some lichen families, e.g., Parmeliaceae and Physciaceae [13], and sometimes particular species (e.g., Alectoria, Usnea spp.) in specific regions [16]. Additionally, the modern climate shifts are increasing at high rates which might exceed the ability of many lichens to adapt or disperse to new environments [14,17].

Airborne pollutants represent one of the significant threats to lichens. Chemicals such as fluoride, lead, nitrogen compounds, and sulfur-containing substances interfere with lichen metabolism and reproduction. Their impacts include reduced photosynthetic activity, inhibition of spore germination, and eventual population loss. These physiological disturbances often translate into shifts in community structure and local extinction of sensitive taxa [17,18,19,20]. Table 1, shown below, presents a summary of the air pollution impacts on lichens.

Table 1.

Pollution-based threats to lichens.

Beyond air pollution, lichens are heavily affected by human activities such as agriculture, infrastructure expansion, and unsustainable harvesting. Land-use changes lead to habitat fragmentation and a reduction in available substrates. Overcollection, often for trade, medicinal, or cultural purposes, leads to a reduction in lichen populations. These anthropogenic drivers together reduce species richness, abundance, and biodiversity, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Land-use change and other threats caused by physical impacts of human activities to lichens.

Climate change contributes to lichens’ current stresses by altering physiological responses, modifying species ranges, and threatening endemic lichen species [17,40]. Many epiphytic lichens in some areas of temperate regions are declining as compared to terricolous species [41]. The survival and metabolic functions of lichens are further affected through physiological stress induced by elevated temperatures and increased UV exposure [17,40,42]. These climate-driven risks are summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Climate change-related threats.

Although lichens are important components of ecosystems, and highly sensitive to environmental change, they are still often overlooked in conservation frameworks. Only a small proportion of species have been formally assessed for extinction risk, leaving many potentially threatened taxa unrecognized [51,52,53].

Epiphytic lichens have been used as vital ecological indicators for assessing air quality and forest health globally. However, according to [54], traditional monitoring needs to expand beyond standard tree trunk areas to include crucial microhabitats such as stumps and fallen branches. Researchers continue to refine both the methodological and biochemical approaches (e.g., Index of Atmospheric Purity) to capture the full scope of species diversity and environmental response. In addition, other novel methods have been implemented, e.g., instance segmentation, which employs a computer vision methodology, which is slowly replacing manual analysis, which is time-consuming to precisely track and quantify individual epiphytic lichen populations [55]. The relevance of these methodologies relies on the presence of data and the diversity of species [56]; thus, all types of forests need to be conserved, even the ones with no economic value, as epiphytes are substrate-specific. Thus, this remains as the conservative challenge [57]. To emphasize the role of epiphytic lichens and their use as bioindicators of forest health, research by Giordani et al. [58] shows that most forests in Europe have exceeded the conservative nitrogen critical load of 2.4 kg N ha−1 yr−1. This was achieved by employing the epiphytic lichens as biomonitoring agents, thus informing the vital role of lichen monitoring for defining sustainable pollution levels and informing effective environmental policy across Europe.

Saxicolous lichens were less represented (hardly a hundred publications) in the literature of the studied field. The basic substrate (e.g., limestone) lessens the effect of acidic pollutants, e.g., acid rain. However, saxicolous lichens have been used to serve as indicators of climate change due to their sensitivity to temperature variations [59]. Temperature variations due to climate change influence growth rates, species diversity, and distribution patterns among these lichen species [60,61]. Due to their substrates, in extreme temperatures the rocks influence the physiology of the lichens compared to that on soil substrates. High precipitation supports increasing species diversity and richness of the saxicolous lichens [62,63,64,65].

The necessity of the conservation of lichens became more and more obvious around the 1990s [66,67]. Though there are lichens protected by law in several countries (e.g., [68,69,70,71,72]), still the number of species is limited and they receive insufficient attention. Local red listing of species is a useful tool for increasing awareness of the threat status of lichens. This activity is usually conducted earlier than protection by law is achieved by national governments. Wirth [73,74] in Germany, Pišút [75] in Slovakia, Cieslinsky et al. [76] in Poland, Trass and Randlane [77] in Estonia, and Clerc et al. [78] in Switzerland were among the first preparing red lists of lichens in Europe. IUCN Categories and Criteria [79] were first published in 1994 after deep research and international consultations. Objectivity and transparency were the aim in assessing the conservation status of species globally, and its understanding among users. The categories and criteria are regularly updated, thus the current version was published on 16 March 2024 [80]. Yahr et al. [81] emphasize the importance of collaboration with the Global Fungal Red List Initiative (GFRLI) [82] and the IUCN Red List Unit in the final reviews and updates of fungal (incl. lichen) contents in the IUCN Red List.

Bibliometric analyses provide valuable insights into the rough progress of scientific research (e.g., [83,84]) and are increasingly applied in environmental and conservation studies. Bibliometric reviews have addressed global challenges such as deforestation, conservation, biodiversity, biodiversity loss, and climate change [85,86,87,88,89,90,91].

Our focus was on the threats to lichens between 1981 and 2024. Two periods were studied separately. The first period of 1981–2004, when research of the threats to lichens turned from lichens as bioindicators of air pollution (concentrating on air pollution, and its various types, as a major threat) towards lichens as objects of conservation studies. The second period of 2005–2024 is characterized by a marked increase in studies addressing climate change, direct human impacts, and the discovery of an increasing diversity of various other threat types.

We were concentrating on the geographical distribution of the investigated research fields (themes) via analyzing authors’ affiliation (countries), co-occurrence of keywords, and changing keyword trends with time based on public databases Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. This was to highlight a robust and systematic understanding of how research on lichen conservation threats has evolved over the past 44 years, to identify critical fields that have been widened over time and to suggest proposals for actions that can address the main topic of lichen threats. Since the database Recent Literature on Lichens [92], that is more entirely treating the available specific literature not accessible for the bibliometric analysis, efforts are aimed for a limited comparison with its data and to gain additional information. Thus, our aim was (1) to evaluate global research trends on threats to lichens, (2) to identify drivers of threats to lichens and their shifts over time, and lastly, (3) to find solutions and suggest proposals for conserving and/or recovering lichens under various levels of threat.

2. Materials, Methods, and Background Knowledge Facts

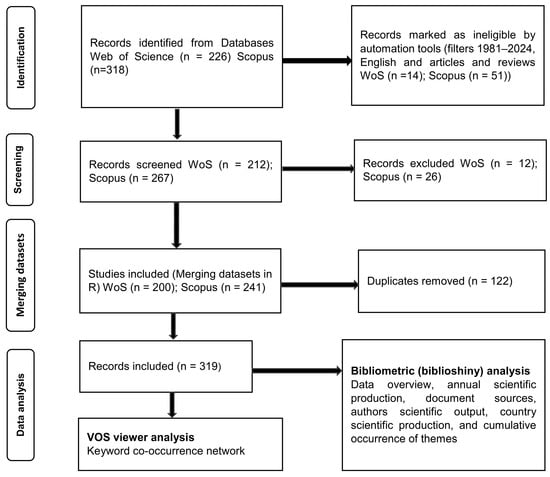

Bibliometrics (VOS viewer version 1.6.20 and Biblioshiny in R core team version 4.5.2) was applied for the analysis. It is a quantitative method that applies statistics to publication and citation data to map the evolutionary structure and the progress of a research field [93]. It not only ensures a systematic and transparent analysis but also enables a replicable evaluation procedure based on the statistical measurement of science, scientists, and scientific activity [94]. Online bibliographic databases such as Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus are among the proposed sources of metadata concerning scientific works [95], as their corpus can be read by analyzing software and were, therefore, chosen for the present study. The systematic flowchart of data search, screening, and analysis according to Page et al. [96] is shown in Figure 1. For retrieving the relevant literature, a comprehensive search was conducted across both Web of Science and Scopus databases using the string: ((“lichen*”) AND ((“threat”) OR (“decline”)) AND ((“climate change”) OR (“air pollution”) OR (“direct human impact”))).

Figure 1.

The systematic flowchart of data search, screening and analysis according to Page et al. [96].

The use of the asterisk (lichen*) ensures the inclusion of all linguistic variations, such as lichen, lichens, lichenized, and lichenized fungi.

Further terms (threat OR decline) act as a filter for environmental vulnerability status. By requiring one of these keywords, we excluded purely taxonomic or physiological papers that describe lichen biology without addressing their environmental vulnerability or population trends. “AND ((“climate change”) OR (“air pollution”) OR (“direct human impact”)))”— These three terms represent the primary drivers recognized in the ecological literature. Using OR allows the search to capture papers focusing on a single driver, while AND ensures that the driver is always linked back to the lichen and its threatened state.

The timespan was restricted to 1981–2024. The years 1981–2004 represent the initial years of research on lichen conservation threats. This phase aligned with the formation of councils that promoted such works, for example, the European Council for the Conservation of Fungi (ECCF) formed in 1985 that is responsible for conservation matters within the European Mycological Association [97]. Currently, it has 80 representatives from across the continent [98]. The International Committee for Conservation of Lichens (ICCL) was established during the second IAL Symposium in Båstad, Sweden in 1992. The Committee also became a Specialist Group under the umbrella of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the IUCN in 1994 [66,67]. The period from 2005 to 2024 marked a notable increase in conservation biology research activity, coinciding with the growing recognition of climate change as a global driver of species decline [99]. Thus, the International Society for Fungal Conservation (ISFC) was formed in 2010, and, currently, it has 300 members representing over 60 countries. Its major aim was to emphasize the importance of fungi globally through awards, publications, meetings, and other activities [100]. The Global Fungal Red List Initiative (GFRLI) was started in 2014 with the aim of relaying information on the status of fungi: threats by pollution, habitat loss, or overexploitation [82].

To ensure consistency and reliability, the search followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [96] for synthesis and analysis of data. The literature search was limited to English language research articles and review papers, excluding editorials and other non-scholarly document types. The selected publications were also reviewed personally by examining their titles and abstract to identify those that were relevant to the subject matter. To ensure the data were relevant, we only included studies that directly evaluated threats to lichens. The bibliographic records from both databases were exported in BibTeX (Scopus) format and plain text (Web of Science) and then were merged and standardized. Bibliometric analysis was conducted using the bibliometric package in R Studio (R version 4.5.2) and VOS viewer (version 1.6.20). According to Aria and Cuccurullo [94] these two tools give a comprehensive assessment of the research topic. The final dataset included studies directly addressing the major threats of lichens and how this topic of research has evolved. VOS viewer (version 1.6.20) was used to generate the keyword co-occurrence map from the study dataset. In total, 899 distinct author keywords were identified. To ensure the clarity and robustness of the network visualization, a minimum threshold of 13 occurrences was applied to the keyword co-occurrence analysis. This specific threshold was selected to identify the definitive core of the research area, ensuring that the included terms are backed by consistent co-occurrence across multiple articles. By filtering “background noise”, this approach eliminated rarely used terms, leaving a stable thematic backbone. In VOS viewer, the size of each node and its label reflect the occurrence of that item in the dataset (i.e., the number of documents in which the keyword appears). Larger nodes indicate terms that occur more frequently and are, therefore, more prominent in the literature. Distance between nodes represents the relatedness of items: shorter distances indicate stronger relationships (higher co-occurrence or link strength), while longer distances indicate weaker relationships.

The bibliometric: the biblioshiny R core team version 4.5.2 ([101] 2023) package was used to generate data output, including an overview of annual scientific production, document sources, authors’ scientific output, country-specific scientific production, and the cumulative occurrence of themes.

Since we are aware of the priority and usefulness of the database Recent Literature on Lichens [92] for lichenological research, we investigated the possibility of its application in the current study. It is more entirely treating the available lichenological literature, and, even if its records are available in BibTeX format, it is not accessible directly for the bibliometric analysis, similarly to the WoS and Scopus. Still, we conducted a search using the search words “threat” and “conservation” and compared the results based on the numbers of hits.

3. Results

3.1. Results Gained from the WoS and Scopus Databases

The bibliometric dataset comprises a timespan from 1981 to 2024, including 319 documents published in 169 distinct sources (Table 4). Average citations per document reached 36, showing the importance of lichen conservation research within the environmental sciences. The mean of five co-authorships per article highlights collaborative work in the research of threats to lichen conservation, although there is a moderate international co-authorship of 23%, which presents a gap for more research and internationally collaborative work.

Table 4.

Overview of the scientific output of 319 research publications.

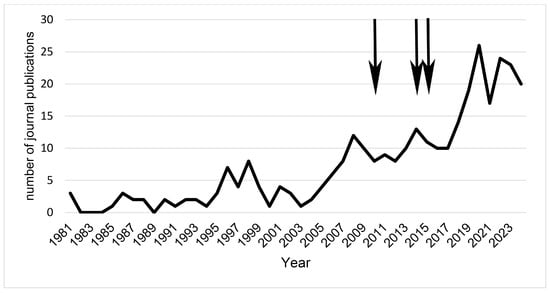

Before 2005, annual scientific production on lichen conservation was generally low, fluctuating between 0 and barely 10 research publications per year, according to Figure 2. This period reflects a stage when research on threats to lichens concentrated in pollution monitoring and with limited integration into broader conservation or climate change discussions. After 2005, there was a marked and sustained increase in publication output, reflecting a shift in the field’s scope. Annual production rose steadily, surpassing 10 research publications, and experienced a sharp acceleration from 2017 onwards, peaking at over 26 publications in 2021.

Figure 2.

Annual scientific output trend on lichen threats (1981–2024). This figure shows the number of journal publications per year, highlighting a significant increase in research activity over the last two decades. The observed spikes in annual output correspond to major institutional and policy milestones: the formation of the International Society for Fungal Conservation (ISFC) in 2010, the launch of the Global Fungal Red List Initiative (GFRLI) in 2014, and the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 (see arrows). These events, among others, provided the necessary infrastructure and global focus to drive research, particularly as climate change became a central concern in conservation biology.

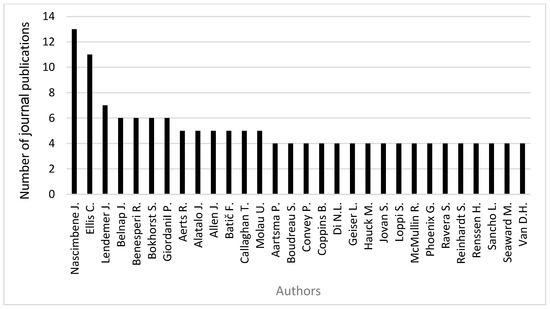

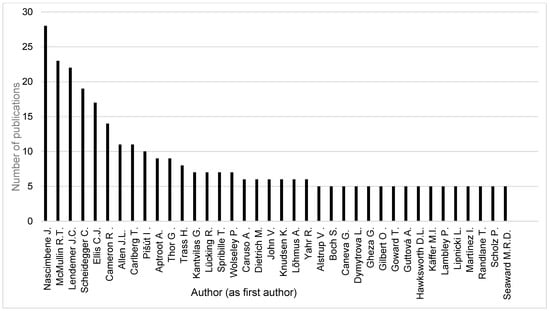

Across the 319 publications reviewed, 1276 authors were identified, emphasizing the broad collaborative base of research in this conservation field. However, only a small proportion of contributors have maintained sustained publishing activity. Specifically, 30 authors produced four or more papers (Figure 3), indicating uneven authorship pattern typical of conservation science, where a core group of specialists drives much of the published work.

Figure 3.

Most relevant authors with ≥4 publications between 1981 and 2024.

The most prolific contributors were Juri Nascimbene (13 publications) and Christopher Ellis (11 publications). James Lendemer followed them with seven papers, and a set of active authors such as Jayne Belnap, Renato Benesperi, Stef Bokhorst, and Paolo Giordani each with six papers. The remaining productive authors published five or four research publications each. Collectively, this group of 30 authors contributed a substantial proportion of the overall output of the investigated dataset. At the same time, the diversity of names with fewer publications also indicates broad participation from the wider lichenological and ecological community. This combination reflects both sustained leadership from established scholars and contributions from a broader pool of researchers, which may support the interdisciplinary character of the field.

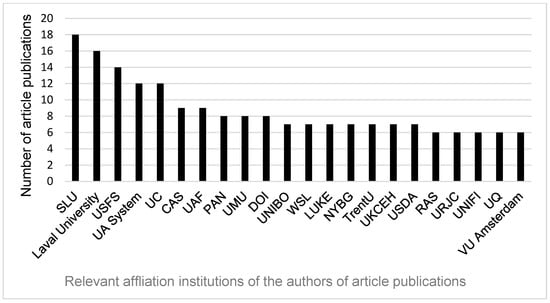

Figure 4 illustrates the most relevant (≥6) contributing institutions identified through the bibliometric analysis. The institutional analysis revealed that a limited number of organizations accounted for a substantial proportion of the total scientific output within the dataset. SLU—Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet) contributing 18 publications, followed by Laval University (Canada) contributing 16 publications, emerged as the most prolific institutions, followed by USDA Forest Service (USA) with 14 publications, then the University of Alaska System (USA) and University of California System (USA) (12 publications each). Other key contributors included the Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks (USA), the Polish Academy of Sciences, Umeå University (Sweden), and the United States Department of the Interior, each producing between eight and nine publications. Several governmental and research organizations, such as the Natural Resources Institute Finland (LUKE), and the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH), also demonstrated notable productivity, each with seven publications. The predominance of European and North American institutions underscores the geographic concentration of research capacity and funding in these regions, reflecting their leading roles in advancing the scientific discourse within the field.

Figure 4.

Most relevant affiliations with ≥6 publications between 1981 and 2024. Abbreviations of institutions are as follows: SLU—Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet), Laval University (Canada), USFS—USDA Forest Service (United States Forest Service—United States Department of Agriculture), UA System—University of Alaska System (USA), UC—University of California (University of California System, USA), CAS—Chinese Academy of Sciences, UAF—University of Alaska Fairbanks, PAN—Polish Academy of Sciences, UMU—Umeå University (Sweden), DOI—United States Department of the Interior, UNIBO—Alma Mater Studiorum—Università di Bologna (Italy), WSL—Eidgenössische Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft (Switzerland), LUKE—Natural Resources Institute Finland, NYBG—New York Botanical Garden (USA), TrentU—Trent University (Canada), UKCEH—UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, USDA—United States Department of Agriculture (USA), RAS—Russian Academy of Sciences, URJC—Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Spain), UNIFI—University of Florence (Italy), UQ—University of Quebec system (Canada), VU Amsterdam—Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

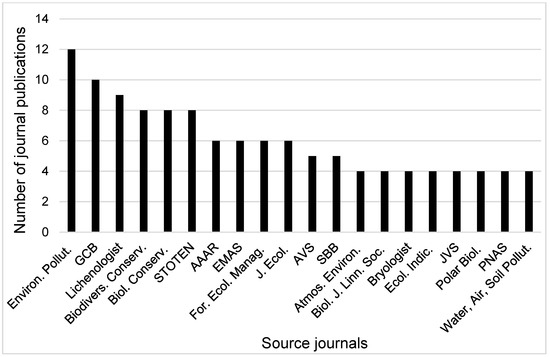

Figure 5 presents 20 journals out of 169 where most of the research work have been published. The concentration of threats to lichen conservation research publication in broad environmental science journals highlights a strong focus on global environmental change and a highly interdisciplinary research approach. For example, Environmental Pollution (12 research publications) and Global Change Biology (10 research publications) top the list, showing that air quality and climate change are dominant themes in the lichen conservation literature. Additionally, The Lichenologist (9) is particularly notable, as it is a highly specialized journal dedicated to lichen research and conservation. Its position among the top three sources highlights the strong role of lichen-focused studies within the broader conservation literature. Other influential sources included Biodiversity and Conservation, Biological Conservation, and Science of the Total Environment (eight research publications each), which together reflect the integration of biodiversity, ecological monitoring, and environmental change in conservation research. Journals such as Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, and Forest Ecology and Management, also played a key role in linking conservation priorities with ecosystem dynamics and management strategies.

Figure 5.

Top publication sources with ≥4 journal publications between 1981 and 2024. Abbreviations of the titles of the journals are as follows: Environ. Pollut.—Environmental Pollution, GCB—Global Change Biology, Lichenologist, Biodivers. Conserv.—Biodiversity and Conservation, Biol. Conserv.—Biological Conservation, STOTEN—Science of the Total Environment, AAAR—Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, EMAS—Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, For. Ecol. Manag.—Forest Ecology and Management, J. Ecol.—Journal of Ecology, AVS—Applied Vegetation Science, SBB—Soil Biology & Biochemistry, Atmos. Environ.—Atmospheric Environment, Biol. J. Linn. Soc.—Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Bryologist, Ecol. Indic.—Ecological Indicators, JVS—Journal of Vegetation Science, Polar Biol.—Polar Biology, PNAS—Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Water, Air, Soil Pollut.—Water, Air and Soil Pollution.

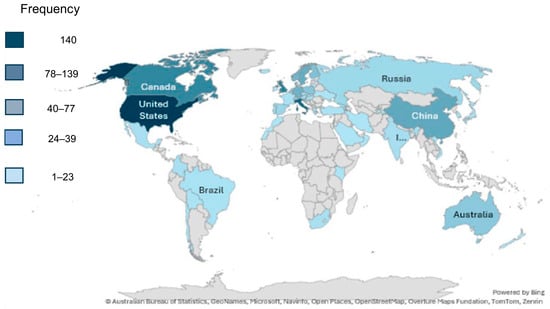

Figure 6 shows the scientific production per country on a global scale in the research topic of threats to lichen conservation. The United States emerges as the leading contributor together with Italy and the United Kingdom, followed by Canada and China, and several European countries, including Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Germany. Australia also has highly notable publication activity. Moderate-to-low output is observed across South America, parts of Asia, and Africa, with most of the African continent showing little to no representation in the dataset.

Figure 6.

The heat map illustrates the geographic frequency of publications by country (1981–2024). The colour scale indicates production intensity: pale blue (1–23 publications), light blue (24–39), medium blue (40–77), dark blue (78–139), and the darkest blue representing the maximum of 140 publications.

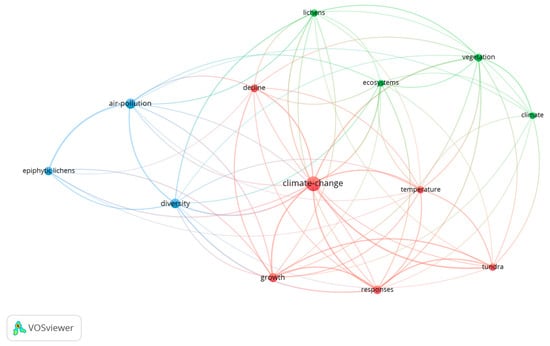

The keyword co-occurrence network (Figure 7) was generated using VOSviewer with a minimum threshold of 13 occurrences. Out of 899 keywords identified in publications addressing threats to lichens from 1981 to 2024, 13 met the cut-off. It revealed three major thematic clusters. The largest and most central cluster (red, cluster 1) was organized around climate change, demonstrating the strongest connectivity with other keywords. Keywords associated with this cluster included temperature, tundra, growth, responses, and decline, reflecting the central role of climatic factors in shaping lichen physiology, population dynamics, and ecosystem impacts. A second cluster (blue, cluster 2) was centred on air pollution, closely linked to epiphytic lichens and diversity. This emphasizes the ongoing significance of atmospheric pollution as a research focus, especially regarding its effects on species richness and the use of lichens as bioindicators of environmental health.

Figure 7.

Keyword co-occurrence map generated in VOSviewer with a minimum threshold of 13 occurrences. This map displays the relationships between the most frequent research terms. A minimum threshold of 13 occurrences was applied to ensure robust connections in the network visualization; of the 899 identified keywords, 13 met this criterion. Node size corresponds to keyword frequency, while link thickness indicates the strength of co-occurrence between terms. The colours represent distinct research themes: red (Cluster 1), blue (Cluster 2), and green (Cluster 3).

The third cluster (green, cluster 3) focused on lichens, ecosystems, vegetation, and climate. This group highlights the integration of lichen conservation into broader ecological and vegetation studies.

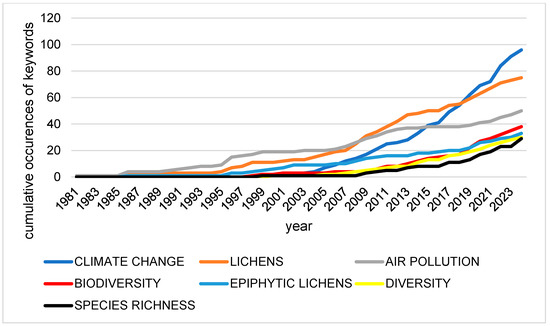

Figure 8 presents the cumulative occurrence of selected keywords in the lichen conservation literature from 1981 to 2024. The results indicate that climate change has become the most prominent and fastest-growing theme, with a sharp increase in usage after 2015 [102]. Air pollution shows a steady growth trajectory beginning in the early 1990s, reflecting its long-standing importance in lichen research, although its rate of increase has been surpassed by climate change in recent years.

Figure 8.

Cumulative occurrences of themes and objects expressed in keywords between 1981 and 2024. The figure illustrates a significant shift in research priorities, with “Climate Change” (deep blue line) showing an exponential growth rate that surpassed “Air Pollution” (grey line) around 2017. This divergence reflects a rising proportion of the total literature focused on global climatic impacts.

The observed “outburst” of climate change-related literature reflected in our results shows a documented paradigm shift within the field. While lichens were historically used to monitor air pollution originating from residential heating and industrial activities, currently, many regions have revealed climate change as the dominant contemporary threat to lichen biodiversity [58]. From a bibliometric point, this transition is evidenced by the high citation (shown by the key keyword co-occurrence map performed by VOS viewer and the cumulative occurrence of keywords performed by Biblioshiny in R version 4.5.2—Figure 7 and Figure 8), strength of climate-related keywords, signalling that the focus of the research community has pivoted toward the poikilohydric response of lichens to global climatic change.

3.2. Results Gained from the Recent Literature on Lichens Database

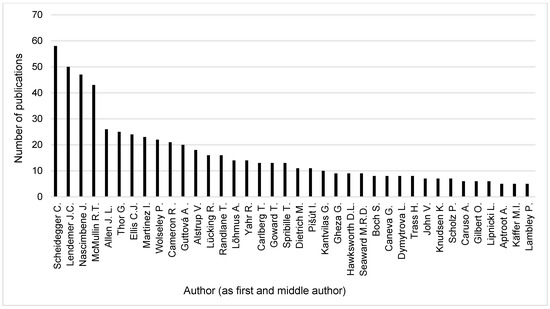

The search word “threat” resulted in 102 publications in the database Recent Literature on Lichens. Therefore we changed the search word to “conservation” where we hoped to have larger hits. Thus, we found 1447 publications (journal publications, books, book chapters, conference proceedings, abstracts, etc.). After deleting those 93 items referring to nomenclatural conservation and book reviews, 1354 publications remained for a further analysis. Across the 1354 publications found the most frequent authors (as first authors, with publication numbers in brackets) (Figure 9) were Juri Nascimbene (28), Richard Mc Mullin (23), and James Lendemer (22). The most frequent authors (as first and middle authors, with publication numbers in brackets) (Figure 10) were Christoph Scheidegger (58), James Lendemer (50), and Juri Nascimbene (47).

Figure 9.

Most relevant authors as first authors with ≥5 publications found in Recent Literature on Lichens between 1981 and 2024.

Figure 10.

Most relevant authors as first and middle authors with ≥5 publications found in Recent Literature on Lichens between 1981 and 2024.

The geographic distribution of the publications was analyzed on the basis of study sites introducing an additional side to the investigated elements of the study (Table 5). Most of the studies were conducted in Europe (48%). North American investigations covered about 20%, Asia 7%, South America and Australia (with Oceania/New Zealand, Papua New Guinea) 3–3%, then Africa and Central America reached hardly 1%. About 18% of the publications studied global problems and general topics, theories of conservation, or the study site indication was missing. In Europe, the studies were most frequently carried out in Great Britain, Sweden, Italy, Germany, Spain, Poland, and Switzerland, but there were studies from Slovakia, Denmark, France, Austria, Norway, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, Hungary, Estonia, Belgium, Belarus, Ukraine, and Finland. Within North America, the United States and Canada participated in 60% and 40%, respectively. From other areas, India, China, Nepal, Thailand, Taiwan, Mongolia, Japan, Türkiye (Asia), then Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Chile (South America), or South Africa, Tanzania, Tunisia (Africa), and Tasmania, Australia, and New Zealand can be mentioned.

Table 5.

Geographic distribution of publications by study sites based on annotations of Recent Literature on Lichens database.

4. Discussion

4.1. Lichen Threat Research Focus over Time

According to the bibliometric results (1981–2004), research on lichen threats was sparse but heavily centred on air quality and environmental pollution. “Air pollution” stands out as one of the main themes during these decades. The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a significant concern over acidic rain, industrial emissions, and their ecological effects [103]. Lichens, being extremely sensitive to sulfur dioxide and other pollutants, were widely used as an indicator of air pollution [104,105]. The concerns of pollution led to standardized protocols for lichen monitoring in forest health and air pollution programmes. A notable outcome was the integration of lichens into environmental policy—for example, lichens were included in European forest condition monitoring under the UNECE Air Convention from 1985 [106,107,108]. In the 1990s–2000s, other pollution challenges emerged (e.g., the increase in nitrogen deposition), which kept the lichen-pollution theme relevant even as its research received somewhat less attention. Studies saw reported shifts in lichen communities due to nitrogen oxides and ammonia from agriculture and traffic, with increasing abundance of nitrophilous lichen species (e.g., Xanthoria parietina) [19].

Around 2005, the annual number of lichen-threat publications began to increase noticeably. Globally, the early 2000s resulted in new high-level commitments to combat climate change and biodiversity loss. For instance, the Kyoto Protocol (negotiated in 1997) entered into force in 2005, and the Convention on Biological Diversity had outlined ambitious targets for 2010 to reduce biodiversity loss [109,110]. These initiatives emphasized climate impacts and species conservation as significant issues, expanding the scope and funding of research.

After 2017, the bibliometric patterns show an increase in the climate change cluster (Figure 8), also reflected by an increase in article production in the same year (Figure 2) marking a new dominant theme in lichen threat research. Several factors explain this rapid rise. The increase in publications after 2017 might be because of growing emphasis on global environmental change, biodiversity conservation, and ecosystem monitoring in international policy frameworks, as well as the increased availability of high-resolution environmental data and collaborative research networks. Although there has been a slight decline since this peak, recent output remains high (20–23 publications per year). The mid-to-late 2010s brought the landmark Paris Agreement (2015) [111] on climate change and the start of climate advocacy, as well as key assessments of biodiversity loss. In addition, in the late 2010s, there was the integration of lichens into international conservation frameworks. Fungal specialists (including lichenologists) became organized under the IUCN Species Survival Commission to conduct red list assessments for lichenized fungi, a process that was started after 2015. Thus, only seven lichen species were assessed in the IUCN Red List in 2015 [67,112]. By 2022, the IUCN Red List included 94 lichen species [113].

Advances in scientific methodology and data accessibility further explain the post-2017 increase in publications. By the late 2010s, citizen-science platforms and biodiversity databases had included millions of fungal (including lichen) observations worldwide [114]. At the same time, high-throughput DNA sequencing and genomics provided new insights into lichen population genetics and physiology, reflecting how factors like habitat fragmentation, pollution, and climate warming affect their viability [115]. All the above shows that the evolution of lichen-threats research corresponds to environmental changes and other external factors, such as regulatory successes in pollution control, the rise in global climate change discussions, and growing conservation movements, all of which influenced where researchers directed their attention.

While the primary analysis focused on established stressors identified in the 319-document set, recent evidence suggests an emerging role for lichens in detecting microplastic (MP) pollution. Table 6, shown below, provides an illustrative overview of these new findings, highlighting how lichens serve as indicators for atmospheric microplastic dispersion and deposition.

Table 6.

Emerging environmental threats of microplastics (MP): lichens as microplastic biomonitors.

The awareness of microplastics as polluting agents is relatively fresh. Lichens are potential detectors of microplastics, and the concentrations accumulated in the lichen thalli might differ depending on distance from the source of the pollutant [116,117,118]. According to [119], lichens are an effective tool for monitoring the atmospheric dispersion and deposition of microplastics around landfills. In addition, the lichen’s potential to grow on plastics is an easier way to detect microplastics, as autofluorescent PET (polyethene terephthalate) microplastic particles adhere to the surface of the lichen thalli [120]. The chemical composition of the microplastics is diverse in the lichen thalli—representing aldehyde, alkene, amine, carboxylic acid, ether, hydrocarbon, hydroxide, ketone, methyl, methylene, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide substances according to [121,122]. As indicated by [121], using chlorophyll fluorescence measurements; short-term exposure to microplastics might have little impact on the lichen but has an environmental impact when introduced into the ecosystem food chain [119].

4.2. Geographic Patterns of Research Output

The production of research on threats to lichens is uneven geographically. Certain countries and regions contribute unequally to the topic. Analysis of authors and publication origins indicates that temperate, developed countries in the Northern Hemisphere dominate this field. Europe and North America stand out as hotspots of lichen-threat research, having main research centres developed in their universities and other institutions. Several factors help to explain this pattern: these regions have long traditions of lichenology and possess the institutional and financial support for sustained research programmes [105]. The United States and Canada, for their part, have integrated lichen monitoring into national forest and air quality programmes since the 1980s, resulting in a steady stream of data-rich studies (e.g., the USDA Forest Service lichen biomonitoring network in forests across the U.S. contributes to many publications) [123,124]. In contrast, countries and regions in the Global South (e.g., tropical Asia, Africa, South America) are underrepresented in the bibliometric data on lichen threats. This is not necessarily due to a lack of threats—indeed, many of these regions host rich lichen floras that are likely experiencing pressure from deforestation, pollution, and climate change—but rather due to historically limited research capacity and funding in lichenology [125].

This geographic disparity in publication output may also reflect differences in environmental priorities and funding: developed nations have been able to invest in long-term ecological monitoring (where lichens feature as indicators), whereas developing nations might prioritize other immediate conservation issues, with lichen-specific threats garnering less attention so far. This geographical pattern highlights a concentration of lichen conservation research in economically developed regions with established environmental science infrastructures and long-standing traditions in ecological monitoring [81,126,127]. The geographic concentration of lichen-climate research in the United States, Canada, China, and Europe primarily reflects a high institutional research capacity and the availability of specialized funding. However, it is important to distinguish between scientific output and environmental performance. While these regions possess the infrastructure to lead global research, they also represent many of the world’s largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions [128,129]. This suggests a socio-economic paradox where the industrial development driving global climatic shifts also provides the financial and academic resources necessary to monitor their ecological consequences. Consequently, high publication volume in these regions should be viewed as a measure of monitoring capability rather than an indicator of successful climate mitigation. Another factor influencing geographic patterns is the distribution of industrial pollution and climate change impacts. Regions that underwent early industrialization (like Western Europe) experienced lichen declines from pollution sooner and, thus, started relevant research earlier (e.g., the famous disappearance of lichens in London during the 19th–20th century induced British studies) [130].

4.3. Proposed Recovery Measures of Lichens from Their Threats

According to the literature, Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, the results of bibliometric analysis, and Figure 7 and Figure 8, lichens are faced by threats that are mainly driven by climate change, air pollution, and human/anthropogenic impacts. In addition, Figure 3 and Figure 6 show that there is uneven representation of research on lichen threats through a few authors and research concentrated in a few countries. The tentative recovery measures (Table 7) were, therefore, suggested as ways to sustain lichens globally in the environment.

Table 7.

Threats, their influencing factors, and proposed recovery measures that enhance lichen conservation.

Table 7 suggests tentative recovery measures that can be applied for the sustainable conservation of lichens. Effective responses highlighted for threats that cause lichen habitat loss through either pollution, climate change, or human impacts are the protection of critical habitats, maintenance of forest heterogeneity, reduction in anthropogenic disturbance, and systematic monitoring of invasive species [59,101]. National and regional strategies, such as establishing protected areas and adapting land-use policy, remain central to safeguarding lichen diversity [136,151].

Beyond habitat-related pressures, lichen thallus is affected directly through air pollution and heat and temperature stress from climate change effects, which can be solved through the involvement of lichenologists in industrialization planning and establishing industrial facilities away from natural reserves [142]. Moreover, the bibliometric analysis outcome revealed two critical gaps. Firstly, collaboration remains limited, with only 23% of studies involving international co-authorship, suggesting that lichen research networks are still regionally centred (Table 4 and Figure 3). Secondly, there is a geographical imbalance in contributions: most publications come from North America, Europe, and parts of East Asia, while presumed biodiversity-rich regions such as Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia are underrepresented (Figure 6). To address these gaps, the recent literature calls for stronger integration of lichens into global biodiversity policy, refinement of IUCN assessments from all regions, and international collaboration that includes underrepresented regions. Even if we consider that conservation and red listing (understanding that red listing is not equal to protection by law) are local matters, since state governments create their own laws and red listing must be the prior responsibility of local experts, the following international cooperations can still be introduced or increased: creating and incorporating general ideas, theories, contributing in identification of lichen taxa, selecting methods used in monitoring, restauration, applying instruments better available in more developed countries, adding that less developed areas should also do their best in increasing their knowledge and struggle for increasing the governmental research budget for the necessary innovations. Such multidimensional and inclusive efforts are critical to ensuring the persistence of lichens in rapidly changing environments [148].

4.4. Comparison with Results Gained from the Recent Literature on Lichens Database

The keywords were different in the two studies, being “threat in the bibliometric analysis” and “conservation” in Recent Literature on Lichens (RLL) [92]. It was necessary to change the keyword to a different and wider one in the case of RLL, since the structure and working method in the data-handling did not result in a high number of publications for a more detailed study in this latter database. The bibliometric analysis was restricted to journal publications (319), RLL was searched for all publications to allow further valuable works (abstracts, books, book chapters, proceedings papers, reviews, local brochures) for the entire analysis. Thus, the higher number of publications (1354) found in RLL is not surprising. Due to these circumstances, the value of comparisons is limited, though the results are interesting and can serve with some additional information.

Contrary to the differences in the datasets, the results were similar in respect to the relevant authors (Figure 3, Figure 9 and Figure 10). Investigating the three most relevant authors (Nascimbene, Ellis, and Lendemer) from the bibliometric analysis, we found that the order changed somewhat, but they remained within the five and seven most relevant authors, accordingly, in the RLL analysis considering their role as first author or considering their entire publication activity in all author positions. Further authors from the results of the RLL analysis are Richard Mc Mullin (23/43), Christoph Scheidegger (19/58), Jessica Allen (11/26), and Göran Thor (9/25) (publication number as first/all author position in brackets). It shows that, in the field of lichen conservation, all publications count and the restriction to journal publications hides important activities of the researchers, which can increase the awareness of the importance of the topic. Furthermore, in the case of some authors (e.g., Scheidegger), the number of publications activities originating from cooperations can be especially prolific.

Concerning the geographic analysis, bibliometric analysis uses the authors’ affiliations, irrelevant of the geographic position of the study site or the nationality (at birth) of the authors. RLL sources were analyzed for the geographic position of the study sites to represent a further side of the entire review. We also found similarities in this comparison, establishing the leading role of Europe, then North America. Some European countries (e.g., Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland) are better represented in RLL, and the diversity of countries with high impact is more obvious based on the study of RLL.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

This study conducted a keyword search in two widely used bibliographic databases, Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, both of which provide reliable metadata. However, reliance on these databases alone may limit coverage. Other lichen-specific resources, such as Recent Literature on Lichens (RLL) [92], could complement WoS and Scopus by capturing publications dedicated exclusively to lichen research, thereby strengthening the comprehensiveness of the dataset. At present, RLL does not allow corpus downloads in a metadata-readable format, which restricts its direct use in bibliometric studies. Nonetheless, integrating multiple databases would help to mitigate database-specific biases and enhance the robustness of future analyses. Future work should, therefore, consider incorporating specialized databases (e.g., RLL) in a more detailed analysis, while also developing methods to extract and harmonize their corpus into bibliometric workflows, as this would expand coverage and improve the accuracy of lichen-threat research assessments.

Additionally, another limitation of this study is that, although potential solutions are proposed to address the identified research gaps, these recommendations remain at a conceptual level. The development and evaluation of detailed implementation strategies fall beyond the scope of this bibliometric review.

5. Conclusions

Over the last 44 years, research on lichen threats has transitioned from a narrow focus on air pollution to a broader conservation-oriented perspective encompassing climate change and direct human pressures. The field has expanded significantly since 2005 and reached a high number of publications after 2017, with slight declines from time to time, recent output remains high (20–23 publications per year), suggesting that research on threats to lichens is now well established and continues to attract considerable scientific attention. However, the bibliometric analysis revealed regional and thematic imbalances, with much of the research concentrated in temperate developed countries and limited international collaboration. The relative underrepresentation of tropical and developing regions, despite their ecological significance and potential vulnerability to environmental change, suggests an imbalance in research coverage. This result emphasizes the need for more globally distributed research efforts, global collaborations, especially in presumed biodiversity hotspots, for example, South America, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Addressing these gaps requires global-scale efforts, particularly in biodiversity-rich but underrepresented regions, along with the integration of lichens into conservation policies and IUCN assessments. Effective recovery strategies should prioritize habitat protection, sustainable land-use policies, pollution mitigation, and stronger cross-regional research networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N.K. and E.É.F.; methodology, C.N.K.; software, C.N.K.; validation, C.N.K. and E.É.F.; formal analysis, C.N.K.; investigation, C.N.K. and E.É.F.; resources, C.N.K. and E.É.F.; data curation, C.N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N.K. and E.É.F.; writing—review and editing, E.É.F.; visualization, C.N.K.; supervision, E.É.F.; project administration, C.N.K. and E.É.F.; funding acquisition, C.N.K. and E.É.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Stipendium Hungaricum, PhD grant number 2022–2026. The APC was funded by the Doctoral School of Biological Sciences, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Original data are available in the public online sources Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus mentioned in the chapter materials, methods, and background knowledge facts.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical support of and useful discussions with László Lőkös (Budapest) during analyzing the data and the preparation of the manuscript. We are very grateful to the three anonymous reviewers who also had very useful comments and suggestions for improving the manuscript text and contents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DTP | Doctoral Training Programmes |

| ECCF | European Council for the Conservation of Fungi |

| GFRLI | The Global Fungal Red List Initiative |

| IAL | International Association for Lichenology |

| ICCL | International Committee for Lichen Conservation |

| ISFC | International Society for Fungal Conservation |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RLL | Recent Literature on Lichens |

| SSC | Species Survival Commission |

| UNECE | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

References

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Grube, M. Lichens redefined as complex ecosystems. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 1281–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahti, T.; Oksanen, J. Epigeic lichen communities of taiga and tundra regions. Vegetation 1990, 86, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasalainen, U.; Tuovinen, V.; Kirika, P.M.; Mollel, N.P.; Hemp, A.; Rikkinen, J. Diversity of Leptogium (Collemataceae, Ascomycota) in East African montane ecosystems. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zedda, L.; Rambold, G. The Diversity of Lichenised Fungi: Ecosystem Functions and Ecosystem Services. In Recent Advances in Lichenology; Upreti, D., Divakar, P., Shukla, V., Bajpai, R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, A.; Adamo, P.; Bonanomi, G.; Motti, R. The role of lichens, mosses, and vascular plants in the biodeterioration of historic buildings: A review. Plants 2022, 11, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, C.; Stofer, S. The importance of old-growth forests for lichens: Keystone structures, connectivity, ecological continuity. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 2015, 166, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, G.; Manneville, O.; Asta, J. Mosses and lichens as bioindicators (s. l.) of wetlands state: Example of four protected areas in the Isère Department (France) [Mousses et lichens, bioindicateurs (s.l.) de l’état des zones humides: Exemples de quatre sites protégés du Département de l’Isère (France)]. Rev. D’ecologie (Terre Vie) 2004, 59, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Çobanoğlu Özyiğitoğlu, G. Use of lichens in biological monitoring of air quality. In Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development; Shukla, V., Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; De Boer, H.; Olafsdottir, E.S.; Omarsdottir, S.; Heidmarsson, S. Phylogenetic diversity of the lichenized algal genus Trebouxia (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta): A new lineage and novel insights from fungal-algal association patterns of Icelandic cetrarioid lichens (Parmeliaceae, Ascomycota). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 194, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, E.; Xu, M.; Muhoro, A.M.; Szabó, K.; Lengyel, A.; Heiðmarsson, S.; Viktorsson, E.Ö.; Olafsdottir, E.S. The algal partnership is associated with quantitative variation of lichen specific metabolites in Cladonia foliacea from Central and Southern Europe. Symbiosis 2024, 92, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ortega, S.; Ortiz-Álvarez, R.; Allan Green, T.; de los Ríos, A. Lichen myco- and photobiont diversity and their relationships at the edge of life (McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, L.; Benesperi, R.; Fačkovcová, Z.; Nascimbene, J.; Ravera, S.; Marchetti, M.; Anselmi, B.; Landi, M.; Landi, S.; Bianchi, E.; et al. Impact of forest management on threatened epiphytic macrolichens: Evidence from a Mediterranean mixed oak forest (Italy). Iforest–Biogeosci. For. 2019, 12, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upreti, D.K.; Divakar, P.K.; Nayaka, S. Commercial and ethnic use of lichens in India. Econ. Bot. 2005, 59, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.L.; Lendemer, J.C. Climate change impacts on endemic, high-elevation lichens in a biodiversity hotspot. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 25, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Larruga, B.; Estébanez-Pérez, B.; Ochoa-Hueso, R. Effects of Nitrogen Deposition on the Abundance and Metabolism of Lichens: A Meta-analysis. Ecosystems 2020, 23, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxham, T.H. The commercial exploitation of lichens for the perfume industry. In Progress in Essential Oil Research; Brunke, E.J., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1986; pp. 491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Aptroot, A. Lichens as an Indicator of Climate and Global Change. In Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth, 1st ed.; Trevor, M.L., Ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamada, O.; Benhamada, N.; Leghouchi, E. Review on the toxic effect of fluorine and lead on lichen metabolism. Int. J. Second. Metab. 2024, 11, 765–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, H.A.; Pignata, M.L. Effects of the heavy metals Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+ on some physiological parameters of the lichen Usnea amblyoclada. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2007, 67, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, T.H. Lichen sensitivity to air pollution. In Lichen Biology, 2nd ed.; Nash, T.H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kaur, R. Fluoride toxicity triggered oxidative stress and the activation of antioxidative defence responses in Spirodela polyrhiza L. Schleiden. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.N.; Safarova, R.B.; Park, S.Y.; Sakuraba, Y.; Oh, M.H.; Zulfugarov, I.S.; Lee, C.B.; Tanaka, A.; Paek, N.C.; Lee, C.H. Chlorophyll Degradation and Light-harvesting Complex II Aggregate Formation During Dark-induced Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis Pheophytinase Mutants. J. Plant Biol. 2019, 62, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamada, O.; Laib, E.; Benhamada, N.; Charef, S.; Chennah, M.; Chennouf, S.; Derbak, H.; Leghouchi, E. Oxidative stress caused by lead in the lichen Xanthoria parietina. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2023, 45, e63221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Brown, D.H.; Máguas, C.; Catarino, F. Lead (Pb) uptake and its effects on membrane integrity and chlorophyll fluorescence in different lichen species. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1997, 37, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, O.; Palmqvist, K.; Olofsson, J. Nitrogen deposition drives lichen community changes through differential species responses. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 2626–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, J.; Padgett, P.E.; Nash, T.H. Physiological responses of lichens to factorial fumigations with nitric acid and ozone. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 170, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujetovienė, G.; Sališiūtė, J.; Dagiliūtė, R.; Žaltauskaitė, J. Physiological response of the bioindicator Ramalina farinacea in relation to atmospheric deposition in an urban environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 26058–26065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarabska-Bożejewicz, D. The impact of nitrogen pollution in the agricultural landscape on lichens: A review of their responses at the community, species, biont and physiological levels. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, T.H. Sensitivity of Lichens to Sulfur Dioxide. Bryologist 1973, 76, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, M.R.; Pirasteh, S.; Shahabpoor, G.; Dehghani, S.A. Biomonitoring of air pollution sulfur dioxide (SO2) by lichen Lecanora muralis. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2011, 15, 933–938. [Google Scholar]

- Meysurova, A.F.; Khizhnyak, S.D.; Pakhomov, P.M. Toxic effect of nitrogen and sulfur dioxides on the chemical composition of Hypogymnia physodes (L.) Nyl.: IR spectroscopic analysis. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2011, 4, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaward, M.R.D. Lichens and sulphur dioxide air pollution: Field studies. Environ. Rev. 1993, 1, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Rodrigues, A.; Branquinho, C.; Garcia, P. Elemental profile of native lichens displaying the impact by agricultural and artificial land uses in the Atlantic Island of São Miguel (Azores). Chemosphere 2021, 267, 128887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, J.; Tretiach, M.; Corana, F.; Lo Schiavo, F.; Kodnik, D.; Dainese, M.; Mannucci, B. Patterns of traffic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution in mountain areas can be revealed by lichen biomonitoring: A case study in the Dolomites (Eastern Italian Alps). Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 475, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.; Pinho, P.; Vieira, J.; Branquinho, C.; Matos, P. Testing the poleotolerance lichen response trait as an indicator of anthropic disturbance in an urban environment. Diversity 2019, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, I.V.; Keller, C.; Scheidegger, C. Effects of management on lichen species richness, ecological traits and community structure in the Rodnei Mountains National Park (Romania). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesperi, R.; Lastrucci, L.; Nascimbene, J. Human disturbance threats the red-listed macrolichen Seirophora villosa (Ach.) Frödén in coastal Juniperus habitats: Evidence from western peninsular Italy. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavitt, S.D.; St. Clair, L.L. Biomonitoring in Western North America: What Can Lichens Tell Us About Ecological Disturbances? In Recent Advances in Lichenology; Upreti, D., Divakar, P., Shukla, V., Bajpai, R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, R.; Devi, D.; Nayaka, S.; Yasmin, F. A checklist of lichens of Assam, India. Asian J. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 11, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptroot, A.; Stapper, N.J.; Košuthová, A.; van Herk, K.C.M. Lichens as an indicator of climate and global change. In Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth, 3rd ed.; Trevor, M.L., Ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptroot, A.; van Herk, C.M. Further evidence of the effects of global warming on lichens, particularly those with Trentepohlia phycobionts. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 146, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowaniec, K.; Latkowska, E.; Skubała, K. Effect of thallus melanisation on the sensitivity of lichens to heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptroot, A.; Stapper, N.J.; Košuthová, A.; Cáceres, M.E.S. Lichens. In Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth, 2nd ed.; Trevor, M.L., Ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.G.A.; Sancho, L.G.; Pintado, A.; Schroeter, B. Functional and spatial pressures on terrestrial vegetation in Antarctica forced by global warming. Polar Biol. 2011, 34, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E.D.; Villella, J.; Carey, G.; Carlberg, T.; Root, H.T. Canopy distribution and survey detectability of a rare old-growth forest lichen. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 392, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayaka, S.; Rai, H. Antarctic Lichen Response to Climate Change: Evidence from Natural Gradients and Temperature Enchantment [sic] Experiments. In Assessing the Antarctic Environment from a Climate Change Perspective; Khare, N., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.D.; Wahren, C.H.; Hollister, R.D.; Henry, G.H.R.; Ahlquist, L.E.; Alatalo, J.M.; Bret-Harte, M.S.; Calef, M.P.; Callaghan, T.V.; Carroll, A.B.; et al. Plant community responses to experimental warming across the tundra biome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, J.W. Winter climate change: Ice encapsulation at mild subfreezing temperatures kills freeze-tolerant lichens. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 72, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksin, I.; Shelyakin, M.; Zakhozhiy, I.; Kozlova, O.; Beckett, R.; Minibayeva, F. Ultraviolet-induced melanisation in lichens: Physiological traits and transcriptome profile. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhaug, K.A.; Gauslaa, Y.; Nybakken, L.; Bilger, W. UV-induction of sun-screening pigments in lichens. New Phytol. 2003, 158, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheza, G.; Di Nuzzo, L.; Nimis, P.L.; Benesperi, R.; Giordani, P.; Vallese, C.; Nascimbene, J. Towards a Red List of the terricolous lichens of Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2022, 156, 824–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullin, R.T. Lichens and allied fungi added to the list of rare species inhabiting the carden alvar natural area, Ontario. Nat. Areas J. 2019, 39, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullin, R.T.; Allen, J.L. An assessment of data accuracy and best practice recommendations for observations of lichens and other taxonomically difficult taxa on iNaturalist. Botany 2022, 100, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stofer, S.; Calatayud, V.; Giordani, P.; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP) International Co-Operative Programme on Assessment and Monitoring of Air Pollution Effects on Forests (ICP Forests) MANUAL on Methods and Criteria for Harmonized Sampling, Assessment, Monitoring and Analysis of the Effects of Air Pollution on Forests Part VII.2; Assessment of Epiphytic Lichen Diversity Assessment of Epiphytic Lichen Diversity ICP Forests 2016, Part VII(2); UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi, S.; Koubaa, O.; Bouachir, W.; Bilodeau, G.A.; Jeddore, G.; Baines, P.; Correia, D.L.P.; Arsenault, A. Automating Lichen Monitoring in Ecological Studies Using Instance Segmentation of Time-Lapse Images. In Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, ICMLA, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitlich, P.; Rogers, P.; Rosentreter, R. Lichen Communities Indicator Results from Idaho: Baseline Sampling. USDA Forest Service–General Technical Report RMRS-GTR; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2003; 14p. [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, J.; Nimis, P.L.; Dainese, M. Epiphytic lichen conservation in the Italian Alps: The role of forest type. Fungal Ecol. 2014, 11, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, P.; Calatayud, V.; Stofer, S.; Seidling, W.; Granke, O.; Fischer, R. Detecting the critical nitrogen loads on European forests by means of epiphytic lichens. A signal-to-noise evaluation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 311, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, L.G.; Pintado, A.; Green, T.G.A. Antarctic studies show lichens to be excellent biomonitors of climate change. Diversity 2019, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, L.; Di Musciano, M.; Conti, M.; Di Nuzzo, L.; Gheza, G.; Grube, M.; Mayrhofer, H.; Martellos, S.; Nimis, P.L.; Pistocchi, C.; et al. Range shift and climatic refugia for alpine lichens under climate change. Divers. Distrib. 2025, 31, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Salcedo, M.; Psomas, A.; Prieto, M.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Martínez, I. Case study of the implications of climate change for lichen diversity and distributions. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 1121–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.; Mohapatra, J.; Shukla, V.; Hamid, M.; Samal, A.; Joshi, Y.; Singh, C.P.; Khuroo, A.A.; Upreti, D.K. Functional traits in lichens along different altitudinal gradients in Indian Himalayan regions as potential indicator of climate change. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespanhol, H.; Séneca, A.; Figueira, R.; Sérgio, C. Bryophyte-environment relationships in rock outcrops of North-western Portugal: The importance of micro and macro-scale variables. Cryptogam. Bryol. 2010, 31, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Bermúdez, G.; Calvino-Cancela, M.; López De Silanes, M.E.; Prieto, B. Lichen saxicolous communities on granite churches in Galicia (NW Spain) as affected by the conditions of north and south orientations. Bryologist 2021, 124, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Correa, J.C.; Saldaña-Vega, A.; Cambrón-Sandoval, V.H.; Concostrina-Zubiri, L.; Gómez-Romero, M. Diversity of saxicolous lichens along an aridity gradient in Central México. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 91, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, C. Erioderma pedicellatum: A critically endangered lichen species. Species Newsl. Species Surviv. Comm. IUCN 1998, 1998, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN SSC Lichen Specialist Group. 2025. Available online: https://iucn.org/our-union/commissions/group/iucn-ssc-lichen-specialist-group (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Faltynowicz, W. Wykaz gatunków porostów chronionych w Polsce [List of lichens protected by law in Poland]. Chronmy Przyr. Ojczysta 1998, 54, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pišút, I. Chránené druhy machorastov a lisajníkov v Slovenskej republike [Bryophytes and lichens protected by law in the Slovak Republic]. Bryonora 1999, 24, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Samir, H.A.; Hachemi, B.; Djamel, M.M.; Mohammed, A.H.; Oussama, H. Species diversity, chorology and conservation of the lichen flora in Tessala Mountains forest (North-West Algeria). Flora Mediterr. 2019, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, C.; Goward, T. Monitoring Lichens for Conservation: Red Lists and Conservation Action Plans. In Monitoring with Lichens—Monitoring Lichens; Nimis, P.L., Scheidegger, C., Wolseley, P.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Nertherlands, 2002; pp. 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, C.; Werth, S. Conservation strategies for lichens: Insights from population biology. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2009, 23, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, V. Rote Liste der Flechten (Lichenes). 1. Fassung (vorlaufige Artenauswahl), Stand Ende 1976. In Rote Liste der Gefahrdeten Tiere und Pfanzen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Naturschutz Aktuell 1; Blab, J., Nowak, E., Trautmann, W., Sukopp, H., Eds.; Kildaverlag: Greven, Germany, 1977; pp. 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, V. Rote Liste der Flechten (Lichenieserte Ascoyzeten). In Rote Liste der Gefährdeten Tiere und Pflanzen in der BRD; Blab, J., Nowak, E., Trautmann, W., Sukopp, H., Eds.; Kildaverlag: Greven, Germany, 1984; pp. 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pišút, I. Zoznam vyhynutych, nezvestnych a ohrozenych lisajnikov Slovenska (1. Verzia) [List of extinct missing and threatened. lichens in Slovakia (1st draft)]. Biologia 1985, 40, 925–935. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslinsky, S.; Czyzewska, K.; Fabiszewski, J. Red list of threatened lichens in Poland. In List of Threatened Planst in Poland; Zarzycki, K., Wojewoda, W., Eds.; Panstwowe Wydawnictvo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1986; pp. 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Trass, H.; Randlane, T. Extinct macrolichens of Estonia. Folia Cryptogam. Est. 1987, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Clerc, P.; Scheidegger, C.; Ammann, K. Liste rouge des macrolichens de la Suisse [The red data list of Swiss macrolichens]. Bot. Helv. 1992, 102, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN 1994; IUCN Red List Categories. IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1994; 18p.

- IUCN 2024; Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, Version 16 (March 2024), 2024. IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/redlistguidelines (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Yahr, R.; Allen, J.L.; Atienza, V.; Burgartz, F.; Chrismas, N.; Dal Forno, M.; Degtjarenko, P.; Ohmura, Y.; Pérez-Ortega, S.; Randlane, T.; et al. Red Listing lichenized fungi: Best practices and future prospects. Lichenologist 2024, 56, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GFRLI. Global Fungal Red List Initiative. 2025. Available online: https://redlist.info/en/iucn (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Aleixandre-Benavent, R.; Aleixandre-Tudó, J.L.; Castelló-Cogollos, L.; Aleixandre, J.L. Trends in scientific research on climate change in agriculture and forestry subject areas (2005–2014). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixandre-Benavent, R.; Aleixandre-Tudo, J.L.; Castelló-Cogollos, L.; Aleixandre, J.L. Trends in global research in deforestation. A bibliometric analysis. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, X.; Lu, F. Research Status and Trends of Agrobiodiversity and Traditional Knowledge Based on Bibliometric Analysis (1992–Mid–2022). Diversity 2022, 14, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, M.L.; Rendina, F.; Cocozza di Montanara, A.; Russo, G.F. Bibliometric Analysis of the Status and Trends of Seamounts’ Research and Their Conservation. Diversity 2024, 16, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A. Trends in climate change research: A Bibliometric review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 114, 190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Stork, H.; Astrin, J.J. Trends in Biodiversity Research. A Bibliometric Assessment. Open J. Ecol. 2014, 4, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.L.; Yiew, T.H.; Habibullah, M.S.; Chen, J.E.; Kamal, S.M.; Saud, N.A. Research trends in biodiversity loss: A Bibliometric analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 2754–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B. A Bibliometric analysis of climate change adaptation based on massive research literature data. J. Clear. Prod. 2018, 199, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Cui, G.; Zhang, L. Progress on geographical distribution, driving factors and ecological functions of Nepalese alder. Diversity 2023, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RLL. Recent Literature on Lichens. 2025. Available online: https://nhm2.uio.no/botanisk/lav/RLL/RLL.HTM (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Baker, H.K.; Kumar, S.; Pattnaik, D. Research constituents, intellectual structure, and collaboration pattern in the journal of Forecasting: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Forecast. 2020, 40, 577–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; Lopez-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualising the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn-Irlet, B. The role of the ECCF in studies and conservation of fungi in Europe. Mycol. Balc. 2005, 2, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECCF. The European Council for the Conservation of Fungi. 2025. Available online: https://www.eccf.eu (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Dobson, A. Monitoring global rates of biodiversity change: Challenges that arise in meeting the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 2010 goals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISFC. International Society for Fungal Conservation. 2025. Available online: www.fungal-conservation.org (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Fu, H.; Waltman, L. Mapping climate change research: A Bibliometric perspective. J. Informetr. 2022, 16, 101187. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L. Lichens as litmus for air pollution: A historical review. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 1971, 1, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.E.; Cecchetti, G. Biological monitoring: Lichens as bioindicators of air pollution assessment: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 114, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, T.; Degrave, W.M.S.; Duarte, G.F. Lichens and health—Trends and perspectives for the study of biodiversity in the Antarctic ecosystem. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Forests. 2025. Available online: https://unece.org/environmental-policy/air/forests (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- UNECE. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Convention and Its Achievements. 2025. Available online: https://unece.org/environmental-policy/air/convention-and-its-achievements (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Frati, L.; Brunialti, G. Recent Trends and Future Challenges for Lichen Biomonitoring in Forests. Forests 2023, 14, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]