Abstract

Freshwater availability is one of the most pressing environmental concerns in arid ecosystems. The use of free-standing water by raptors has been little studied, and in the context of climate change has become increasingly important as extended droughts are expected to become more frequent. We analyzed digital images from camera traps captured in the freshwater springs of Sierra El Mechudo, during summer to early autumn of 2023 and 2024 in Baja California Sur, Mexico. We recorded 165 detections of four raptor species. The Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) was the most frequently detected (n = 55), followed by the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) (n = 50), the Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) (n = 45), and the Cooper’s Hawk (Astur cooperii), which was observed only in early autumn 2024 (n = 15). The Great Horned Owl exhibited a distinct detection pattern (mainly crepuscular, with the highest peak at 6 a.m.), in contrast with the other three species, which were detected mainly at midday and in the afternoon, during the hottest hours of the day. All raptors were recorded drinking water; however, species differed in the proportion of behaviors they exhibited at the freshwater springs. The Turkey Vulture showed the highest drinking activity (76.3%), whereas both hawks exhibited the same lowest proportions (26.6%) among all species detected. The proportion of behaviors remained constant across years. The time spent at the freshwater springs did not differ across species or years. The Red-tailed Hawk, the Great Horned Owl, and the Turkey Vulture increased their detections at the springs in 2024, when a severe and prolonged drought affected the southern peninsula. The results showed that the importance of freshwater springs for raptors extends beyond their use for drinking only; the surrounding habitat as a refuge and availability of prey in the area are evidently essential for these birds of prey. Further studies should extend research into the diverse use of springs and home ranges of raptors in the southern Baja California peninsula.

1. Introduction

The availability of free-standing water is closely linked to the ecology and survival of terrestrial vertebrates, mostly in arid ecosystems [1]. In the case of raptors, however, it has long been assumed that the need for free-standing water is minimal or even negligible, as it is commonly assumed they can obtain water from metabolic processes and preformed water [2]. Few studies have been conducted (mostly in artificial water sources) to test or evaluate this highly debated assumption and its potential ecological effects [3,4]. Water scarcity, as a consequence of extended droughts, could affect raptors and other groups of birds in both the short and long term [5,6]. Substantial impacts of climate change are likely for species already living close to their physiological thresholds, particularly in desert environments characterized by extreme temperatures and limited water availability [6,7,8].

Free-standing water is not a reliable natural resource, particularly in arid regions where seasonal monsoons only occur during summer and are subject to considerable interannual variability [9]. These areas are expected to become more unpredictable in the context of climate change, with several regions facing reduced water accessibility in ecosystems [10], such as the southern Baja California peninsula where freshwater availability is among the most pressing environmental concerns [11]. Reduced streams and waterholes occur in some areas of the southern Baja California peninsula, where several species of resident raptors are settled throughout the year and where other migratory raptors arrive in early autumn from the US and Canada [12,13,14]. Extreme droughts could reduce the availability of these small freshwater bodies, affecting the quality of these habitats and consequently the ecology of many vertebrates of these regions. The climate in northwestern Mexico is undergoing significant changes; maximum and minimum temperatures have increased in the Baja California peninsula, while accumulated rainfall has decreased over the last few decades [15]. Climate research predicts more extreme climatic events, with more severe droughts and more frequent extreme daily rainfall expected in this region [16,17,18]. Climatic volatility could affect communities in multiple ways, with extended droughts having a greater impact on carnivorous animals [19], and several other key species of North American drylands could face increasing challenges in the near future in response to extreme climate predictions [17,20,21]. Top predators such as raptors could be impacted by climate change mostly by severe drought conditions [22,23,24]. In this climatic scenario, limited water bodies and their immediate surroundings may serve as a refuge for these predators [25]. Not only do they provide opportunities to maintain water and temperature balance (avoiding dehydration and hyperthermia), but they might also offer a higher occurrence of prey in these areas [7,26].

Therefore, expanding our understanding of raptor behavior and ecology in response to extreme events is essential, particularly in regions where climate change is expected to intensify the environmental variability. The aim of the present study is to describe and evaluate the use of water sources and their associated habitats by raptors during two contrasting rainfall seasons in an arid, scarped landscape in the southern area of Sierra La Giganta, Baja California Sur. We predicted that (a) raptor species would use freshwater springs according to their expected daily activity pattern (diurnal vs. nocturnal), (b) species would change their activities at the springs during a drier year (for example, spending more time drinking), and (c) raptors would use freshwater springs more frequently during a drier year.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

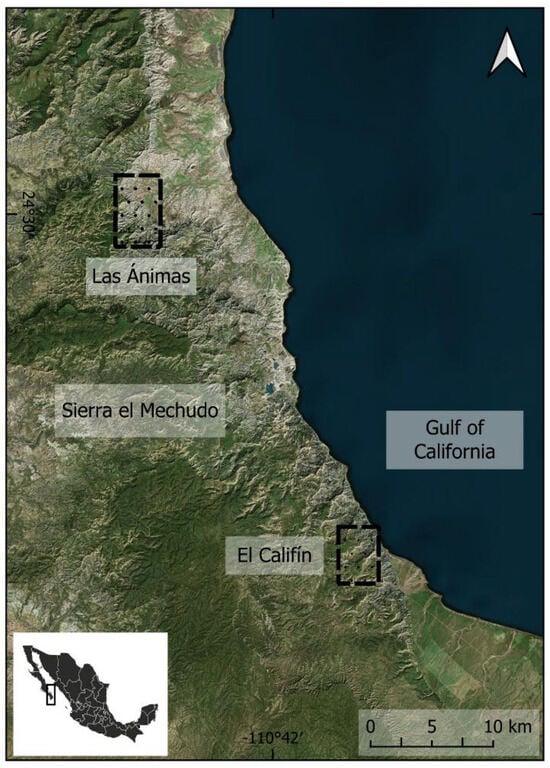

We conducted the study in Sierra El Mechudo, the most southern area of Sierra La Giganta, Baja California Sur, Mexico (Figure 1). The study area consists of streams within canyons with steep walls that share similar characteristics in terms of landforms and xerophilous vegetation [27]. These steep streams with seasonal water availability are sustained mostly by summer monsoonal storms [28].

Figure 1.

Study area located in Sierra El Mechudo (Las Ánimas and El Califín), Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

The climate in the area is classified as a Köeppen hot desert climate, a dry and hot regime, with most of its rainfall during the summer (90%) [29]. Mean annual air temperatures range between 23.7 °C and 29.4 °C, although during the summer, temperatures can be over 40 °C [30]. Precipitation comes mostly from the monsoonal storms and hurricanes, and the area could receive 300 mm of annual rainfall; however, the study area is placed in the transition between the subtropical monsoonal rainfall type characteristic of the southern half of the peninsula, and that of the winter cyclonic rainfall regime of the Pacific coast [9]. When either or both air mass systems are weak, the study area may receive no rainfall, and such conditions can persist for several years [30].

2.2. Data Analysis

We analyzed 27,792 h of digital images captured by motion-triggered camera traps (Bushnell Corporation, Overland Park, KS, USA) from July 8 to October 8 during the summer and early autumn 2023 and 2024. We sampled two areas in Sierra El Mechudo: El Califín, located 23 km north of the city of La Paz, and Las Ánimas, located 25 km north of the first sampling location (Figure 1). These two areas include dynamic natural sources of water; freshwater springs may be available depending on the season. Droughts and violent summer monsoons can change the availability of some freshwater springs either between years or in the same season. We set camera traps in both areas, aiming to represent most of them with equal effort, placing the cameras in freshwater springs according to their availability at the time. Overall, images were obtained from 13 camera traps set in 2023 (7 springs) and 9 camera traps in 2024 (6 springs). We set 8 cameras in Las Ánimas in 2023 (4 springs) and 5 cameras in El Califín in 2023 (3 springs). In 2024, we used 6 cameras in Las Ánimas (4 springs) and 3 cameras in El Califín (2 springs). A total of 16,728 h were analyzed in 2023 (Las Ánimas: 10,392 h; El Califín: 6336 h), and 11,064 h in 2024 (Las Ánimas: 6816 h; El Califín: 4248 h) (Figure 2, Supplementary Materials Table S1).

Figure 2.

(a) Great Horned Owl standing near a spring pool, and (b) a Great Horned Owl detected after drinking water close to midnight in the study area. (c) A Red-tailed Hawk after bathing in a spring pool in Las Ánimas around noon, and (d) a Red-tailed Hawk flying with a bird prey item just captured near the water source in October 2024. (e) Two Turkey Vultures drinking water in the afternoon, and (f) a Cooper’s Hawk standing near the water source, detected in October 2024.

The cameras were positioned to cover most of the sampling points and maximize the detection of raptors in the area of interest. When the points encompass a larger area to be included by a single camera, we set up a second camera to maximize detectability. In this case, we looked for double detections, and if it was the case, the second detection (using the timer of the camera trap) was eliminated from the records before the analyses.

Information about the position of the freshwater springs was obtained in both years through interviews with local ranchers and from previous aerial surveys used for detection and sampling design. Camera traps were set up and deployed 0.70–1 m above ground for wildlife detection in the water points and close surroundings. The cameras were set to continuously take images when motion was detected with a 5 s interval between successive photographs.

We used a 24 h period (00:00 h to 24:00 h) as a recorded day on which the camera was active at each spot. Ambient-temperature data were obtained from the camera trap’s internal sensor and displayed as an overlaid value on the image in which the raptor was first detected. We considered raptor detection as the first sighting; if another individual showed up at the same time, the detection was still considered as one (only increasing the group size) [4]. A new detection was considered if 15 min had passed since the last image of a raptor of the same species; this is a reasonable amount of time to ensure a raptor did not just move out of frame of the camera before returning [4]. Date, time, species, minimum group size, and water source name were recorded for each image in which an individual was initially detected. We classified the behavior in every detection as “drink”, “approaching”, “bath”, “predation” [3], and “fly” when the bird was detected only in flight.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the daily activity patterns of raptors at the freshwater springs using circular statistics. A circular MANOVA was applied to test for differences among species [31]. Additionally, to detect any hourly detection bias, we used a binomial GAM with cyclic time smoothers, generating pseudo-absences across site, week, and year to provide a baseline for comparison. We performed pairwise post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment on the sine and cosine components of the circular data. We also tested for differences in environmental temperatures (at the times birds were detected) among species using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon comparisons adjusted with Holm’s method for multiple testing [32].

We evaluated the time raptors spent in freshwater springs and surroundings using the Scheirer–Ray–Hare test, a non-parametric alternative to a two-way ANOVA. This analysis tested whether the species and/or the year produced significant differences in the amount of time raptors spend at these sites.

We also compared the proportion of each detected behavior across years (2023, 2024) and species. Behavioral classifications were independently assigned by three observers. When two agreed, that classification was adopted. In the hypothetical case of three different classifications (which did not occur), a fourth observer would have resolved the tie. For this purpose, we used contingency tables combined with Chi-square tests of independence.

We aimed to evaluate whether detection rates differed between a normal year (2023) and a dry year (2024), both overall and at the species level. To address this question, we used a model selection approach based on generalized additive models (GAMs) fitted with a Tweedie error distribution and a log link. Because sampling sites were expected to differ in baseline detection levels, all models included a random-effect smooth for site (average detection rate of each freshwater spring). We constructed a set of candidate models: (1) a null model with only the site random effect; (2) a model including year; (3) a model including the raptor species; (4) an additive model including both predictors (species + year); and (5) an interaction model to test whether species responded differently. All models were fitted using restricted maximum likelihood (REML). Model comparison was conducted using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), and nested models were additionally evaluated using analysis of deviance (F-test). Model selection was based on the combination of AIC, parsimony, and numerical stability.

All the statistical analyses were carried out using the “MASS”, “car”, “circular”, and “mgcv” packages and for graphics, the “ggplot2” package of the R version 4.5.2 [33]. Geographical data were processed using QGIS version 3.40.12 [34].

3. Results

We detected raptors 165 times (mean = 1.24 individuals, SD = 0.68, range = 1–6) during the study period. The Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) was the most numerous species detected by the camera traps (n = 55, mean = 1.63 individuals, SD = 1.04, range = 1–6), then the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) (n = 50, mean = 1.08 individuals, SD = 0.27, range = 1–2), followed by the Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) (n = 45, mean = 1.04 individuals, SD = 0.20, range = 1–2), and the Cooper’s Hawk (Astur cooperii) only in 2024 (n = 15, mean = 1 individuals, SD = 0, range = 1) (Figure 2).

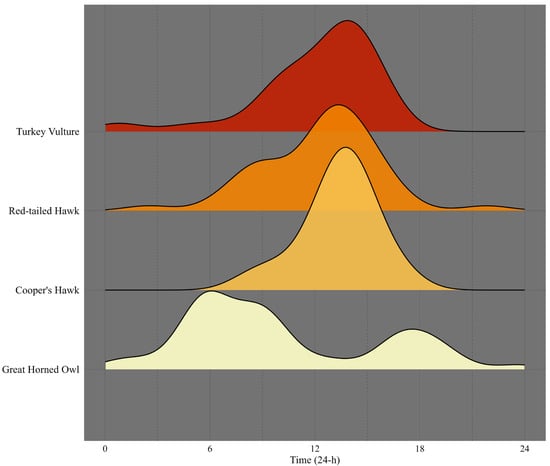

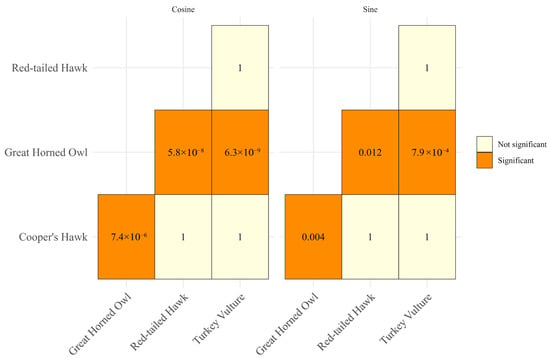

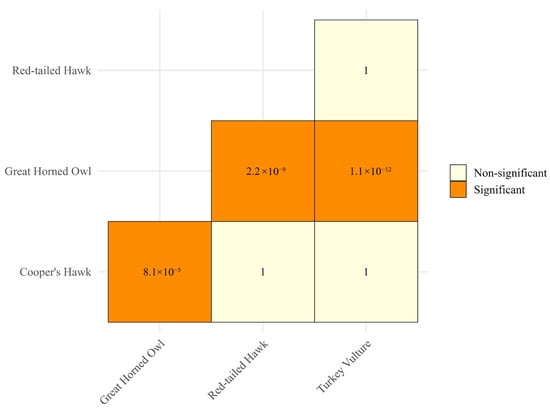

The time of the day when the natural water bodies were used differed among species (Figure 3 and Figure 4). For the cosine component, species explained a substantial proportion of the variance (F3, 161 = 19.44, p = 8.29 × 10−11), while the sine component also showed significant differences (F3, 161 = 7.14, p = 0.0001). We found no evidence of significant detection bias due to nocturnal camera function in raptor occurrence (Supplementary Materials Figure S1. Pairwise post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment showed that Great Horned Owl differed significantly from all other species. In contrast, the Cooper’s Hawk, Red-tailed Hawk, and Turkey Vulture did not differ significantly among themselves (adjusted p-values = 1) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Time-of-day (24 h) detection by raptor species in the study area, Baja California Sur, Mexico, during 2023–2024.

Figure 4.

p-values of pairwise post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment for time-of-day utilization of freshwater springs by raptors, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

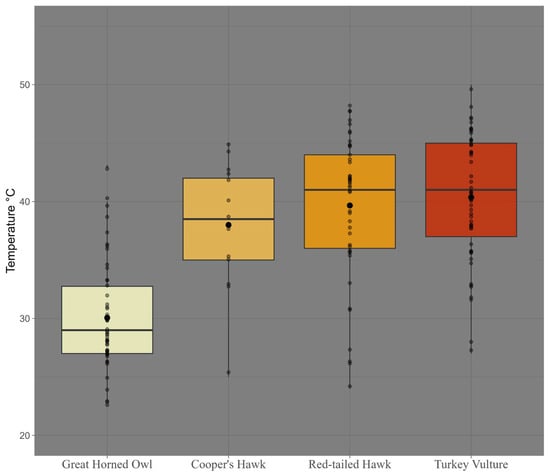

Concordantly, mean measured temperatures differ among species (Kruskal-Wallis, X2 = 64.85, df = 3, p = 5.38 × 10−14, Figure 5). Furthermore, pairwise post hoc contrasts also showed that the Great Horned Owl differed significantly from all other species (adjusted p-values = 1) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Temperatures (°C) associated with raptor detections by camera traps in the study area, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

Figure 6.

p-values of pairwise Wilcoxon comparisons adjusted with Holm’s method for multiple testing of temperatures by raptor species, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

The time raptors spent in the springs did not show significant main effects of species (H = 0.84, p = 0.83) or year (H = 0.35, p = 0.55). Likewise, the species × year interaction was not significant (H = 3.1, p = 0.20) (Supplementary Materials Tables S2 and S3).

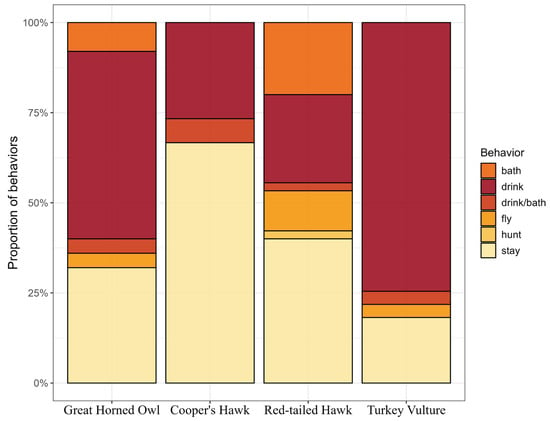

Birds exhibited several activities at the water sources and their immediate surroundings. The most frequent activity—drinking water—was registered in the Turkey Vulture (76.3%, Figure 7), whereas both hawks (26.6%) registered the lowest number of records for this behavior. We also documented a successful predation event in which a Red-tailed Hawk captured a passerine (Figure 2d). The analyses of behavior proportions showed that behaviors did not differ significantly between 2023 and 2024 (X2 = 6.90, df = 5, and p = 0.22). In contrast, the comparison between behavior and species revealed a statistically significant association (X2 = 46.6, df = 15, and p = 4.26 × 10−5).

Figure 7.

Proportion of behaviors recorded by raptor species, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

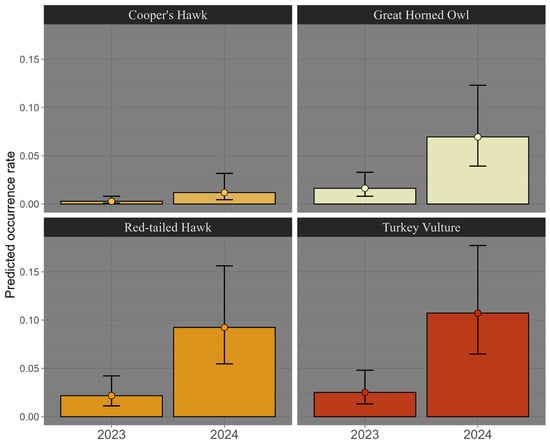

The evaluation of occurrence rates showed that model comparison indicated that the best-supported model included species and year as fixed effects (AIC = 92.20, Supplementary Materials Table S4). The effect of year was highly significant (β = 1.45 ± 0.32, t = 4.60, p = 7.6 × 10−6), with higher occurrence rates in 2024 (Supplementary Materials Tables S4 and S5). Three species—the Great Horned Owl (β = 1.77 ± 0.57, p = 0.0021), Red-tailed Hawk (β = 2.05 ± 0.55, p = 2.9 × 10−4), and Turkey Vulture (β = 2.20 ± 0.55, p = 8.9 × 10−5)—showed significantly higher rates than the Cooper’s Hawk (Figure 8). The random effect of site did not explain additional variation (edf ≈ 0, p = 0.40). The additive model explained 23.4% of the deviance (adjusted R2 = 0.135, REML = 40.43, scale parameter = 0.45, n = 192). The interaction model (species × year) had the lowest AIC (79.43) but produced numerically unstable estimates (extreme coefficients and collinearity) and was therefore excluded from interpretation.

Figure 8.

Detection rate (per week) by year of sampling for each raptor species in the study area, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

4. Discussion

Several studies have highlighted the importance of water sources and freshwater ecosystems for birds’ survival [35,36], and others have shown multiple types of freshwater use by raptors [3,4]. In the case of raptors, most of the studies were conducted in artificial water sources [3,4,37]; to our knowledge, this is the first camera trap analysis focused on raptor use of natural springs in arid landscapes. The present study confirms, as expected, that the temporal patterns of freshwater springs use are closely aligned with the diel activity rhythms of diurnal species; however, owls exhibited predominantly crepuscular–nocturnal use of the springs.

Climatic records in the area of La Paz (20 km south of the sampling area) indicated an accumulated rainfall of 17 mm approximately throughout 2024 (January–October); in contrast, the 2023 accumulated rainfall registered more than 400 mm (January–October) (https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/tools/RESOURCES/Normales_Climatologicas/Mensuales/bcs/mes03074.txt, accesed on 25 October 2025). This context likely explains the increasing number of raptors detected (except the Great Horned Owl) in the 2024 summer camera trap sampling. The reduction in water sources in the home range utilized by vultures and hawks probably increased the visits to these scarcer water sources. However, the drought also may reduce the primary productivity in the extended home range of these raptors and consequently the availability of hawks’ prey in the arid landscape. The prolonged drought could also cause rodents and smaller birds to become restricted to these limited humid environments. Small water bodies could be focal points of intensified ecological interactions—such as predation—among individuals and species in arid landscapes, particularly when these sources are scarce [26,38,39]. The Red-tailed Hawk and Cooper’s Hawk could take advantage of these refuges for these small vertebrates, staying closer to water springs during a dry year in contrast to average rainfall years. A recent study in Texas showed raptors visited man-made water sources more frequently during years of scarce rainfall than in wet years, accounting for more than 80% of total occurrences in dry years [4]. There is a clearly general trend regarding the use of water sources in arid landscapes in several studies; however, certain aspects must be discussed in more detail for each raptor species and considering certain limitations of the design. In the current study, most sites were revisited within seasons, providing a sampling effort that strengthens inference about relative occurrence rates. Nevertheless, not all sites could be consistently surveyed across years, as several were lost to flooding or became unsuitable due to severe drought. Our GAM approach with a site random-effect smooth therefore captures species- and year-level variation under highly dynamic freshwater conditions, but the requirement of stable points replication to use fully balanced multi-season occupancy models is a limitation. As a result, our conclusions pertain to relative differences in occurrence and site use, rather than absolute abundance trends. Below, we further discuss specific data related to water use and associated habitat.

4.1. Turkey Vulture

It is evident that species of raptors have diverse natural water requirements, influenced not only by the water itself but also by the surrounding habitats provided by the springs. It should be noted that Turkey Vultures are the most common raptor in southern Baja California [12], which explains the highest occurrence of the species at the spring. However, the use of water sources reflected the physiological importance of this natural resource in the area for them. Although the mean proportion of time did not differ significantly among species, this vulture displayed the highest use of water for drinking in contrast to hawks as the lowest. Boal et al., in 2023, found a similar proportion of vultures using artificial water sources for drinking (63%) in an arid landscape of Texas, evidencing the physiological importance of this resource for survival in the arid landscape. In the current study, the occurrence of vultures increases from 10:00 h with the peak of activity between 13:00 h and 15:00 h, when temperatures reach 40 °C in the area.

Scavengers need a large area to find a food source, and these same areas may also be used simply for drinking, as suggested by our behavioral records. On rare occasions, we recorded a group of vultures spending the whole morning in the shade of the springs, indicating some degree of social interaction, but it was not the rule.

4.2. Great Horned Owl

The number of individuals per visit was generally low; owls occurred mostly alone at the springs, as registered in another study in an arid landscape of Arizona [3]. Based on the camera trap images, the species evidenced mostly a crepuscular activity, showing two peaks of occurrence: one around at 6:00 h in the morning and another near the sunset at approximately 18:00 h. Nocturnal activity in the springs was found for other Strigiform, the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) in Texas; however, this species showed a peak of occurrence around midnight [4]. Probably, the difference in timing depends more on the preying activity of each species. A diverse kind of prey has been recorded in the diet of the Great Horned Owl (rodents, birds, reptiles, and arthropods) in a southern area of the Baja California peninsula, supporting a crepuscular activity pattern when some birds and reptiles are still active, rather than during the middle of the night [40]. This timing may also help avoid predators such as the Bobcat (Lynx rufus), the Coyote (Canis latrans), and/or the Puma (Puma concolor), which were frequently detected at these water sources during nighttime hours. It is noteworthy that the main activity peak occurred in the early morning rather than in the afternoon. Owls significantly increased their use of water between 3 a.m. and 5 a.m. during darkness and visits were more than twice as frequent at sunrise compared to sunset. This suggests that water use by this species is more complex than simply coinciding with the timing of its foraging activity. Digestive physiology and water balance in owls, which differ markedly from those of Falconiformes [41], should be considered when interpreting early diurnal water consumption in comparison with the other three raptor species in this study. Information on the timing of water consumption in this owl is largely unknown, and further research is needed to better understand the physiological requirements of this species in the wild.

4.3. Red-Tailed Hawk

This raptor increases its occurrence in the springs from the early morning, reaching a maximum during the afternoon when temperatures rise between 12:30 h and 14:00 h. The balanced range of activities observed in this microhabitat denotes that this natural water habitat could be considered an optimal refuge during the hot summer in the area for this raptor. The species showed the highest use for bathing and for remaining nearby, and exhibited a proportion of drinking water use very similar to that of the other hawk, the Cooper’s Hawk. In contrast, Boal et al., in 2023, registered this species drinking water all the time it was detected; however, this study in Texas was conducted in artificial water sources (tanks) and probably in the absence of the kind of natural habitat that offers a water spring in our study area. This habitat could also provide a profitable area for hunting, as birds are very abundant in these water spots. A successful hunting attempt was also registered, evidencing the diverse use of this habitat by this hawk (Figure 2d). Several bird species have been documented in the diet of the Red-tailed Hawk [42,43]. Furthermore, other birds detected using the water sources, such as the Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), could also be on the diet of this raptor (Frixione, unpublished data).

Considering their geographical origin, we suspect the individuals detected are mostly residents because they were registered since the early summer. Most of the migrants of several species (raptors and other Families) that overwinter in the southern Baja California peninsula started to arrive in September, when temperatures decreased and most of the primary productivity increased in the area after the rainfall season [12,44,45]. The primary productivity augmentation in the arid landscape of the peninsula consequently increases prey availability for raptors, in most of the habitats of the peninsula. However, the number of individuals detected remained stable throughout the summer, showing they could be settled in a larger area including these springs as key habitats in their home range.

4.4. Cooper’s Hawk

We recorded at least two different individuals in the area, one of them a juvenile detected in late September. We suggest these individuals may be mostly migrants arriving from northern regions, as they began to appear during the last week of September 2024 and increased in number the first week of October, coinciding with the onset of autumn. The Cooper’s Hawk can reproduce in the southwestern USA and migrate during autumn–winter to the Baja California peninsula, Mexico, from California, USA [46]. Like this species, other large raptors—such as the Zone-tailed Hawk (Buteo albonotatus) (Frixione, unpublished data) and the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) [47]—have been registered in the southern area of the peninsula after September–October through winter.

In the case of this hawk, the use of water springs followed the same pattern as that of the Red-tailed Hawk; however, Cooper’s Hawks were primarily detected after 12:00, when temperatures approached their daily peak. It is evident that the species use this habitat not only for drinking but also as a potential hunting site, given the high abundance of birds in this microhabitat. Birds—especially doves—are well-known primary prey of this hawk [48]. Doves, such as Zenaida asiatica, Z. macroura, and Columbina passerina, were the most abundant species detected by camera traps at the springs. In Arizona, doves have been observed being hunted by Cooper’s Hawks [3], so it is plausible that this raptor takes advantage of the high dove activity at water sources in our study area.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the importance of freshwater springs in the Baja California peninsula for raptors extends beyond water consumption; it also reflects the value of the habitats associated with these sources. The use of springs by raptors is closely connected with the diel activity rhythms as expected. Our study shows that these environments function as a refuge during droughts and extreme heat, and provide increased opportunities for hunting, among other uses. The time raptors spend at the springs and the proportion of behaviors they display did not change because of a drier year; however, extended droughts may intensify raptor occurrence at springs, both due to reduced availability of water sources and increased concentrations of prey species. Such climatic events may contract home ranges and concentrate raptor activity in specific areas during drier years. Our results suggest an increase in the use of freshwater springs during a drought year; however, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the study limitations inherent to this highly unstable hydrological environment when compared to more stable systems. Future studies should focus on raptor home range dynamics in relation to climatic factors. The use and management of natural water sources should be further studied and protected, as these habitats clearly serve as refuges for a wide diversity of species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18010028/s1, Figure S1: Hourly detection bias for raptors species (Great Horned Owl, Cooper’s Hawk, Red-tailed Hawk, and Turkey Vulture) estimated with binomial GAMs using cyclic time smoothers; Table S1: Location, names of the freshwater springs points, and time evaluated (h) by point in Sierra El Mechudo, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024. Table S2: Mean time by species recorded at springs in Sierra El Mechudo, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024. Table S3: Scheirer–Ray–Hare test results when the time raptors spent was evaluated at freshwater springs in Sierra El Mechudo, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024. Table S4: Model-selection analysis based on generalized additive models (GAMs) for evaluation of detection rates at freshwater springs in Sierra El Mechudo, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024. Table S5: Model selected based on generalized additive models (GAMs) for detection rates at freshwater springs in Sierra El Mechudo, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2023–2024.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.F. and I.G.-C.; methodology, M.G.F. and I.G.-C.; formal analysis, M.G.F. and I.G.-C.; investigation, M.G.F., I.G.-C., R.R.-O., E.d.J.R.-M., I.T.-Z., G.A.A.-F., J.R.-R. and F.I.G.-M.; writing—original draft, M.G.F.; writing—review and editing, I.G.-C., R.R.-O., E.d.J.R.-M., I.T.-Z., G.A.A.-F., J.R.-R. and F.I.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We thank for the support provided by Eólicas Coromuel S.A. de C.V. for the use of camera traps for this study in the project titled: “General analysis of the spatial distribution and current status of the bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) population in the Sierra El Mechudo, municipality of La Paz, B.C.S.”; with institutional registration number 20463.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable support of the field and laboratory technicians Abelino Cota Castro, Gil. E. Ceseña, and Agustín Argueta.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research was funded by Eólicas Coromuel S.A. de C.V., and all potential conflicts have been disclosed and managed according to standard ethical practices.

References

- Rosenstock, S.S.; Ballard, W.B.; DeVos, J.C. Viewpoint: Benefits and impacts of wildlife water developments. Rangel. Ecol. Manag./J. Range Manag. Arch. 1999, 52, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildstein, K.L. Raptors: The curious nature of diurnal birds of prey. In Raptors; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, C.S.; Waddell, R.B.; Rosenstock, S.S.; Rabe, M.J. Wildlife use of water catchments in southwestern Arizona. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2006, 34, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boal, C.W.; Bibles, B.D.; Gicklhorn, T.S. Patterns of water use by raptors in the Southern Great Plains. J. Raptor Res. 2023, 57, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ruiz, M.; Dykstra, C.R.; Booms, T.L.; Henderson, M.T. Conservation letter: Effects of global climate change on raptors. J. Raptor Res. 2023, 57, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKechnie, A. Physiological and morphological effects of climate change. In Effects of Climate Change on Birds, 2nd ed.; Dunn, P.O., Møller, A.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie, A.E.; Wolf, B.O. Climate change increases the likelihood of catastrophic avian mortality events during extreme heat waves. Biol. Lett. 2010, 6, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iknayan, K.J.; Beissinger, S.R. Collapse of a desert bird community over the past century driven by climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8597–8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, J.R.; Turner, R.M. Seasonal precipitation regimes in Baja California, Mexico. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 1965, 47, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milly, P.C.; Betancourt, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Hirsch, R.M.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Stouffer, R.J. Stationarity is dead: Whither water management? Science 2008, 319, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Rubio, A.; Lagunas-Vázques, M.; Morales, L.F.B. Conclusiones. In Evaluación Biológica y Ecológica de la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra La Laguna, Baja California Sur: Avances y Retos; Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C.: La Paz, Mexico, 2019; 422p. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Estrella, R.; Donázar, J.A.; Hiraldo, F. Raptors as indicators of environmental change in the scrub habitat of Baja California Sur, Mexico. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, P.H.; McCrary, M.D.; Scott, J.M.; Papp, J.M.; Sernka, K.J.; Thomas, S.E.; Kidd, J.W.; Henckel, E.H.; Henckel, J.L.; Gibson, M.J. Northward summer migration of Red-tailed Hawks fledged from southern latitudes. J. Raptor Res. 2015, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frixione, M.G.; Rodríguez-Estrella, R. Factors influencing prevalence and intensity of Haemosporidian infection in American Kestrels in the nonbreeding season on the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. J. Raptor Res. 2023, 57, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray-Tortarolo, G.N. Seven decades of climate change across Mexico. Atmósfera 2021, 34, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Austria, P.F.; Jano-Pérez, J.A. Climate change and extreme temperature trends in the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Air Soil Water Res. 2021, 14, 11786221211010702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Reséndiz, R.A.; Galina-Tessaro, P.; Sinervo, B.; Miles, D.B.; Valdez-Villavicencio, J.H.; Valle-Jiménez, F.I.; Méndez-de La Cruz, F.R. How will climate change impact fossorial lizard species? Two examples in the Baja California Peninsula. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 95, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Camarena, J.P.; Brito-Castillo, L.; Farfán, L.M. Precipitation in Northwestern Mexico: Daily extreme events. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 2689–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prugh, L.R.; Deguines, N.; Grinath, J.B.; Suding, K.N.; Bean, W.T.; Stafford, R.; Brashares, J.S. Ecological winners and losers of extreme drought in California. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, T.P.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Rittenhouse, C.D.; Clayton, M.K.; Wardlow, B.D.; Flather, C.H.; Culbert, P.D.; Radeloff, V.C. Combined effects of heat waves and droughts on avian communities across the conterminous United States. Ecosphere 2010, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, P.A.; Christensen, E.; Ernest, S.M.; Lightfoot, D.C.; Schooley, R.L.; Stapp, P.; Rudgers, J.A. Declines in rodent abundance and diversity track regional climate variability in North American drylands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 4005–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-McDonnell, K.K.; Wolf, B.O. Rapid warming and drought negatively impact population size and reproductive dynamics of an avian predator in the arid southwest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Heras, M.S.; Mougeot, F.; Simmons, R.E.; Arroyo, B. Regional and temporal variation in diet and provisioning rates suggest weather limits prey availability for an endangered raptor. Ibis 2017, 159, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, S.K.; Bloom, P.H.; Madden, M.C.; Molden, J.C.; Sebes, J.B.; E Duerr, A.; E Katzner, T.; Fisher, R.N. Extreme drought increased home range sizes and space use of Aquila chrysaetos (Golden Eagles) in coastal southern California. Ornithol. Appl. 2025, duaf044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, P.L. Wildlife Use of Two Artificial Water Developments on the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, Southwestern Arizona. Master’s Thesis, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Destefano, S.; Schmidt, S.L.; DeVos, J.C. Observations of predator activity at wildlife water developments in southern Arizona. J. Range Manag. 2000, 53, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Zavala, E. Caracterización del Hábitat y Fauna Asociada a los Cuerpos de Agua Superficial en el sur de la Sierra de El Mechudo, BCS México. Master’s Thesis, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, La Paz, Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grismer, L.L.; McGuire, J.A. The oases of central Baja California, Mexico. Part I. A preliminary account of the relict mesophilic herpetofauna and the status of the oases. Bull. South. Calif. Acad. Sci. 1993, 92, 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- García, E. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Kóppen (para Adaptarlo a las Condiciones de la República Mexicana), 2nd ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1973; 246p. [Google Scholar]

- León de la Luz, J.L.; Rebman, J.; Domínguez-León, M.; Domínguez-Cadena, R. The vascular flora and floristic relationships of the Sierra de La Giganta in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2008, 79, 29–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pewsey, A.; Neuhäuser, M.; Ruxton, G.D. Circular Statistics in R; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.40.12-Bratislava). Open Source Geospatial Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Manning, D.W.; Sullivan, S.M.P. Conservation across aquatic-terrestrial boundaries: Linking continental-scale water quality to emergent aquatic insects and declining aerial insectivorous birds. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 633160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, A.; Tobler, M.W.; Valladares, N.A.; Pardo, A.A.; Macdonald, D.W.; Swaisgood, R.R. Protected areas maintain neotropical freshwater bird biodiversity in the face of human activity. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, C.G.W.; Naholo, S.; Mendelsohn, J.M.; Stratford, K.J. Drinking and bathing behaviour of raptors in an arid, warm environment: Insights from a long-term camera trapping study in Namibia. Namib. J. Environ. 2024, 9, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, D.B. Inter-and Intra-specific Conflict between Arid-zone Kangaroos at Watering Points. Wildl. Res. 1985, 12, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paúl, M.J.; Layna, J.F.; Monterroso, P.; Álvares, F. Resource partitioning of sympatric African wolves (Canis lupaster) and side-striped Jackals (Canis adustus) in an arid environment from West Africa. Diversity 2020, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Sarmiento, C.A. Comparación de la Ecología Trófica del búho Cornudo (Bubo virginianus) en una zona Natural y una Fragmentada del Matorral Desértico en Baja California Sur. Master’s Thesis, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, La Paz, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, G.E. Gastrointestinal physiology and nutrition in wild birds. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1997, 56, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, C.D.; Kochert, M.N. Are red-tailed hawks and great horned owls diurnal-nocturnal dietary counterparts? Wilson Bull. 1995, 107, 615–628. [Google Scholar]

- Gatto, A.E.; Grubb, T.G.; Chambers, C.L. Red-tailed hawk dietary overlap with Northern Goshawks on the Kaibab Plateau, Arizona. J. Raptor Res. 2005, 39, 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, G.; Rodriguez-Estrella, R. Human activity may benefit white-faced ibises overwintering in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Colon. Waterbirds 1998, 21, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, G.; Rodríguez-Estrella, R.; Merino, S.; Bertellotti, M. Effects of spatial and host variables on hematozoa in white-crowned sparrows wintering in Baja California. J. Wildl. Dis. 2001, 37, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, P.H.; McCrary, M.D.; Papp, J.M.; Thomas, S.E. Banding reveals potential northward migration of Cooper’s Hawks from southern California. J. Raptor Res. 2017, 51, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Cárdenas, I.; Galina-Tessaro, P.; Álvarez-Cárdenas, S.; Mesa-Zavala, E. Avistamientos recientes de águila real (Aquila chrysaetos) en la sierra El Mechudo, Baja California Sur, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2013, 84, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, T.C.; Lima, S.L. Hunting behavior and diet of Cooper’s Hawks: An urban view of the small-bird-in-winter paradigm. Condor 2003, 105, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.