Ecological Effects of Seaweed Restoration on Benthic Macrofauna in Marine Forest Development Areas Along the Eastern Coast of Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Sample Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

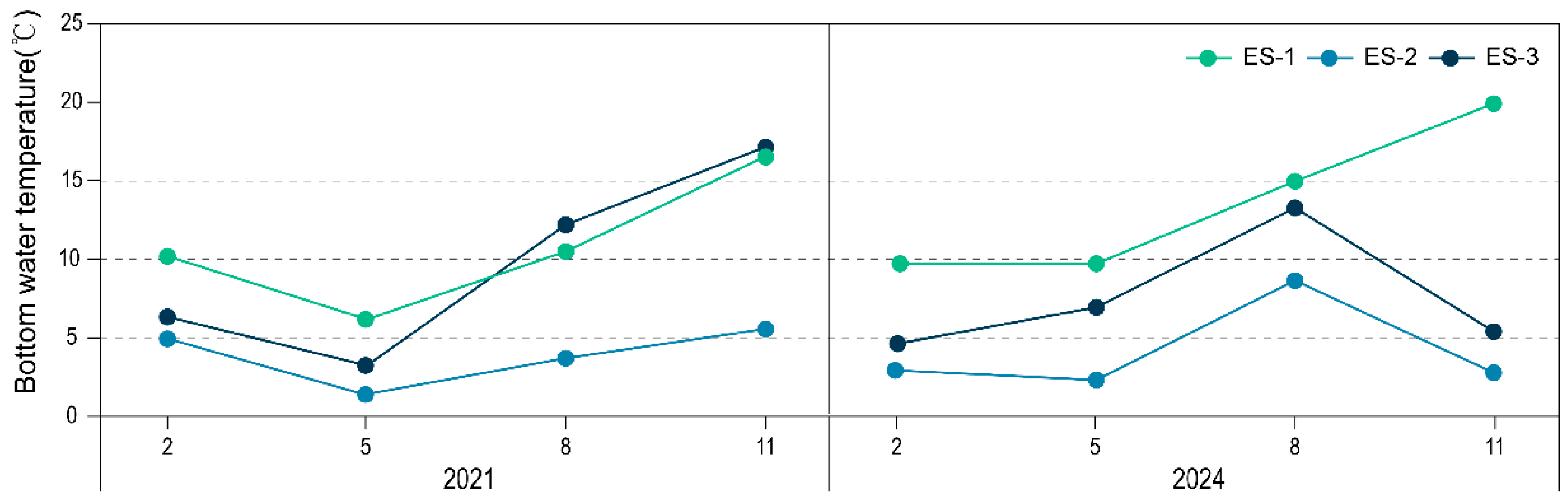

3.1. Water Temperature

3.2. Seaweed and Macrozoobenthic Communities

3.3. Feeding Guild Structure of the Macrozoobenthic Community

3.4. Species Diversity and Richness

3.5. Relationships Between Water Temperature, Seaweed, and Macrozoobenthic Communities

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ES-1 | Pohang study site (southern East Sea coast) |

| ES-2 | Gangneung study site (central East Sea coast) |

| ES-3 | Yangyang study site (northern East Sea coast) |

| SPF | Subpolar Front |

| MEIS | Marine Environmental Information System |

| PRIMER 7 | Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research, version 7 |

| H′ | Shannon–Wiener Diversity Index |

| R | Species Richness |

References

- Whitaker, S.G.; Smith, J.R.; Murray, S.N. Reestablishment of the Southern California Rocky Intertidal Brown Alga, Silvetia compressa: An Experimental Investigation of Techniques and Abiotic and Biotic Factors That Affect Restoration Success. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, F.; Sun, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, F. Reproductive biology of Sargassum thunbergii (Fucales, Phaeophyceae). Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 2574–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traiger, S.B. Effects of elevated temperature and sedimentation on grazing rates of the green sea urchin: Implications for kelp forests exposed to increased sedimentation with climate change. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2019, 73, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernberg, T. Marine Heatwave Drives Collapse of Kelp Forests in Western Australia. In Ecosystem Collapse and Climate Change; Canadell, J.G., Jackson, R.B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 325–343. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.W.; Rho, H.S.; Choi, C.G. Seaweed Beds and Community Structure in the East and South Coast of Korea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steneck, R.S.; Graham, M.H.; Bourque, B.J.; Corbett, D.; Erlandson, J.M.; Estes, J.A.; Tegner, M.J. Kelp forest ecosystems: Biodiversity, stability, resilience and future. Environ. Conserv. 2002, 29, 436–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbee-Dexter, K.; Scheibling, R.E. Sea urchin barrens as alternative stable states of collapsed kelp ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 495, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.D.; Scheibling, R.E.; Rassweiler, A.; Johnson, C.R.; Shears, N.; Connell, S.D.; Salomon, A.K.; Norderhaug, K.M.; Pérez-Matus, A.; Hernández, J.C.; et al. Global regime shift dynamics of catastrophic sea urchin overgrazing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20130269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, D.S.; Elliott Smith, E.A.; Farrell, S.P.; Rasher, D.B. Kelp forest loss and emergence of turf algae reshapes energy flow to predators in a rapidly warming ecosystem. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Adair, E.C.; Cardinale, B.J.; Byrnes, J.E.K.; Hungate, B.A.; Matulich, K.L.; Gonzalez, A.; Duffy, J.E.; Gamfeldt, L.; O’Connor, M.I. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 2012, 486, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.I.; Rho, H.S.; Park, J.M.; Kim, B.-S.; Park, J.W.; Kim, D.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, C.I. Seasonal Dynamics of Algal Communities and Key Environmental Drivers in the Subpolar Front Zone off Eastern Korea. Biology 2025, 14, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-D.; Park, M.-S.; Yoo, H.-I.; Min, B.-H.; Jin, H.-J. Seasonal variations of seaweed community structure at the subtidal zone of Bihwa on the East coast of Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2012, 45, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, J. Current status and ecological, policy proposals on barren ground management in Korea. Ocean. Polar Res. 2023, 45, 173–183–173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, A.M.; Marzinelli, E.M.; Christie, H.; Fagerli, C.W.; Fujita, D.; Gonzalez, A.P.; Hong, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, L.C.; McHugh, T.A.; et al. Global kelp forest restoration: Past lessons, present status, and future directions. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1449–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Yun, H.Y.; Shin, K.-H.; Kim, J.H. Evaluation of Food Web Structure and Complexity in the Process of Kelp Bed Recovery Using Stable Isotope Analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 885676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, S.; Baird, D.J.; Soares, A.M.V.M. Beyond taxonomy: A review of macroinvertebrate trait-based community descriptors as tools for freshwater biomonitoring. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemani, S.; Misiuk, B.; Cote, D.; Edinger, E.; Mackin-McLaughlin, J.; Templeton, A.; Robert, K. Incorporating functional traits with habitat maps: Patterns of diversity in coastal benthic assemblages. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1141737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galobart, C.; Ballesteros, E.; Golo, R.; Cebrian, E. Addressing marine restoration success: Evidence of species and functional diversity recovery in a ten-year restored macroalgal forest. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1176655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.S.A.; Pontalier, H.; Spence, M.A.; Pinnegar, J.K.; Greenstreet, S.P.R.; Moriarty, M.; Hélaouët, P.; Lynam, C.P. A feeding guild indicator to assess environmental change impacts on marine ecosystem structure and functioning. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 1769–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Moon, C.-H.; Kim, S.; Chun, C.-K. Latitudinal variation of the number of species and species diversity in shelled gastropods of eastern coast of Korea. Korean J. Malacol. 2004, 20, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, R.S.K.; Hughes, R.N. An Introduction to Marine Ecology; Blackwell Scientific Publications: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shimeta, J.; Jumars, P.A. Physical mechanisms and rates of particle capture by suspension feeders. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 1991, 29, 191–257. [Google Scholar]

- Jumars, P.A.; Dorgan, K.M.; Lindsay, S.M. Diet of Worms Emended: An Update of Polychaete Feeding Guilds. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2015, 7, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; Illinois University Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Margalef, R. Information theory in ecology. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 1958, 3, 36–71. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.; Gorley, R. PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Somerfield, P.J.; Chapman, M.G. On resemblance measures for ecological studies, including taxonomic dissimilarities and a zero-adjusted Bray-Curtis coefficient for denuded assemblages. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2006, 330, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Walsh, D.C.I. PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr. 2013, 83, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Gorley, R.; Clarke, K. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E Plymouth Marine Laboratory: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Linke, T. Trophic Interactions Among Abundant Members of the Fish Fauna in a Permanently-Open and a Seasonally-Open Estuary in South-Western Australia; Murdoch University: Perth, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Jensen, D.; Duarte, C.M. Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagle, H.; Hawkins, S.J.; Moore, P.J.; Smale, D.A. The role of kelp species as biogenic habitat formers in coastal marine ecosystems. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2017, 492, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, A.M.; Marzinelli, E.M.; Beas-Luna, R.; Blain, C.O.; Blamey, L.K.; Byrnes, J.E.K.; Carnell, P.E.; Choi, C.G.; Hessing-Lewis, M.; Kim, K.Y.; et al. The value of ecosystem services in global marine kelp forests. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salland, N.; Jensen, A.; Smale, D.A. The structure and diversity of macroinvertebrate assemblages associated with the understudied pseudo-kelp Saccorhiza polyschides in the Western English Channel (UK). Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 198, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salta, M.; Wharton, J.A.; Blache, Y.; Stokes, K.R.; Briand, J.-F. Marine biofilms on artificial surfaces: Structure and dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 2879–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.F.; Abd-Elgawad, A.; Cai, R.; Luo, Z.; Pie, L.; Xu, C. Microbial community shift on artificial biological reef structures (ABRs) deployed in the South China Sea. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uji, T.; Mizuta, H. The role of plant hormones on the reproductive success of red and brown algae. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1019334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes, K.M.; Carpenter, R.C. Kelp canopy facilitates understory algal assemblage via competitive release during early stages of secondary succession. Ecology 2015, 96, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bué, M.; Smale, D.A.; Natanni, G.; Marshall, H.; Moore, P.J. Multiple-scale interactions structure macroinvertebrate assemblages associated with kelp understory algae. Divers. Distrib. 2020, 26, 1551–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.H. Effects of Local Deforestation on the Diversity and Structure of Southern California Giant Kelp Forest Food Webs. Ecosystems 2004, 7, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, J.-C.; Riera, P.; Laurans, M.; Leroux, C.; Lévêque, L.; Davoult, D. Community, trophic structure and functioning in two contrasting Laminaria hyperborea forests. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 152, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, K.; Janke, K.; Krüß, A.; Weidemann, W. The macrofauna and macroflora associated with Laminaria digitata and L. hyperborea at the island of Helgoland (German Bight, North Sea). Helgoländer Meeresunters 1990, 44, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.T.; Byers, J.E.; DeVore, J.L.; Sotka, E.E. Engineering or food? Mechanisms of facilitation by a habitat-forming invasive seaweed. Ecology 2014, 95, 2699–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørberg, S.B.; Krause-Jensen, D.; Mouritsen, K.N.; Olesen, B.; Marbà, N.; Larsen, M.H.; Blicher, M.E.; Sejr, M.K. Canopy-Forming Macroalgae Facilitate Recolonization of Sub-Arctic Intertidal Fauna and Reduce Temperature Extremes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafeh-Dalmau, N.; Montaño-Moctezuma, G.; Martínez, J.A.; Beas-Luna, R.; Schoeman, D.S.; Torres-Moye, G. Extreme Marine Heatwaves Alter Kelp Forest Community Near Its Equatorward Distribution Limit. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, D.A. Impacts of ocean warming on kelp forest ecosystems. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, K.M.; Reed, D.C.; Miller, R.J. The Blob marine heatwave transforms California kelp forest ecosystems. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, C.D.G.; Anderson, K.M.; Demes, K.W.; Jorve, J.P.; Kordas, R.L.; Coyle, T.A.; Graham, M.H. Effects of climate change on global seaweed communities. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1064–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, A.; Doropoulos, C.; Malcolm, H.A.; Skye, M.; Garcia-Pizá, M.; Marzinelli, E.M.; Campbell, A.H.; Ballesteros, E.; Hoey, A.S.; Vila-Concejo, A.; et al. Long-term empirical evidence of ocean warming leading to tropicalization of fish communities, increased herbivory, and loss of kelp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13791–13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.J.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lamy, T.; Kui, L.; Rassweiler, A.; Reed, D.C. Giant kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera, increases faunal diversity through physical engineering. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20172571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstone-Gallagher, R.V.; Needham, H.R.; Lohrer, A.M.; Lundquist, C.J.; Pilditch, C.A. Site-dependent effects of bioturbator-detritus interactions alter soft-sediment ecosystem function. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 569, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, R.B. Organization of a Plant-Arthropod Association in Simple and Diverse Habitats: The Fauna of Collards (Brassica Oleracea). Ecol. Monogr. 1973, 43, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statzner, B.; Dolédec, S.; Hugueny, B. Biological trait composition of European stream invertebrate communities: Assessing the effects of various trait filter types. Ecography 2004, 27, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchelli, S.; Fraschetti, S.; Martini, F.; Lo Martire, M.; Nepote, E.; Ippoliti, D.; Rindi, F.; Danovaro, R. Macroalgal forest restoration: The effect of the foundation species. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1213184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnie, J.; Creel, S. The many effects of carnivores on their prey and their implications for trophic cascades, and ecosystem structure and function. Food Webs 2017, 12, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Stations | Bottom-Water Temperature (MEIS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stations | Local Name | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Water Depth (m) | Stations | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) |

| ES-1 | Pohang | 36°14′43.62″ | 129°23′6.51″ | 12.50 | CE2504 | 36°12′6.00″ | 129°24′1.00″ |

| ES-2 | Gangneung | 37°38′37.58″ | 129°03′2.74″ | 7.80 | CE2530 | 37°39′52.00″ | 129°04′51.00″ |

| ES-3 | Yangyangi | 37°58′49.34″ | 128°45′57.02″ | 11.50 | CE2538 | 38°00′45.00″ | 128°45′1.00″ |

| Study Area and Year Classification | ES-1 | ES-2 | ES-3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | |||

| Seaweed | Total | Species number | 51 | 48 | 33 | 46 | 33 | 51 |

| Biomass | 104.41 | 816.08 | 52.90 | 732.54 | 18.86 | 1022.32 | ||

| Rhodophyta | Species number | 31 | 31 | 22 | 29 | 21 | 39 | |

| Biomass | 62.21 | 465.16 | 2.57 | 216.23 | 10.91 | 151.45 | ||

| Ochrophyta | Species number | 12 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 7 | 9 | |

| Biomass | 36.49 | 331.48 | 50.21 | 506.90 | 6.81 | 841.89 | ||

| Chlorophyta | Species number | 8 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |

| Biomass | 5.71 | 19.44 | 0.12 | 9.41 | 1.14 | 28.99 | ||

| Macrozoobenthos | Total | Species number | 131 | 239 | 105 | 226 | 103 | 216 |

| Biomass | 537.99 | 717.59 | 335.68 | 667.00 | 97.30 | 508.09 | ||

| Annelida | Species number | 22 | 46 | 18 | 43 | 22 | 40 | |

| Biomass | 4.50 | 24.65 | 2.53 | 15.09 | 0.87 | 5.41 | ||

| Arthropoda | Species number | 38 | 87 | 47 | 78 | 32 | 83 | |

| Biomass | 6.46 | 15.71 | 11.24 | 85.35 | 0.53 | 20.37 | ||

| Echinodermata | Species number | 11 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 9 | |

| Biomass | 85.79 | 53.53 | 40.71 | 33.16 | 43.72 | 48.39 | ||

| Mollusca | Species number | 52 | 61 | 30 | 54 | 37 | 51 | |

| Biomass | 1.43 | 4.86 | 0.03 | 2.35 | 0.29 | 7.25 | ||

| Others | Species number | 8 | 33 | 5 | 44 | 8 | 33 | |

| Biomass | 7.12 | 67.96 | 59.16 | 30.53 | 0.29 | 15.07 | ||

| Source | df | Seaweed | Macrozoobenthos | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | Pseudo-F | p | COV | MS | Pseudo-F | p | COV | ||

| Site | 2 | 829.4 | 1.103 | 0.376 | 3.192 | 788.3 | 4.220 | 0.001 | 8.671 |

| Year | 1 | 5441.2 | 7.197 | 0.002 | 20.245 | 1944.3 | 10.407 | 0.001 | 12.102 |

| Site × Year | 2 | 891.8 | 1.186 | 0.339 | 6.068 | 735.4 | 3.936 | 0.010 | 11.711 |

| Residual | 17 | 751.9 | 27.421 | 186.8 | 13.668 | ||||

| Total | 22 | ||||||||

| Study Area and Year | ES-1 | ES-2 | ES-3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrozoobenthic Feeding Guild | 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | ||

| Grazer | Species number | 28 | 35 | 15 | 35 | 21 | 35 | |

| Density (ind./m2) | 59 | 391 | 50 | 123 | 29 | 252 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | 163.20 | 203.70 | 220.25 | 157.00 | 50.77 | 113.65 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | 562.7% | 146.0% | 769.0% | |||||

| Carnivore | Species number | 42 | 72 | 36 | 71 | 32 | 66 | |

| Density (ind./m2) | 101 | 222 | 42 | 281 | 30 | 327 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | 77.77 | 95.85 | 52.51 | 200.02 | 11.57 | 34.90 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | 119.8% | 569.0% | 990.0% | |||||

| Suspension feeder | Species number | 31 | 53 | 22 | 55 | 20 | 42 | |

| Density (ind./m2) | 110 | 334 | 103 | 532 | 28 | 155 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | 287.18 | 374.72 | 61.53 | 296.65 | 32.87 | 346.75 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | 203.6% | 416.5% | 453.6% | |||||

| Others | Deposit feeder | Species number | 6 | 22 | 8 | 20 | 6 | 19 |

| Density (ind./m2) | 6 | 42 | 4 | 41 | 6 | 30 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | 4.97 | 12.72 | 0.22 | 4.22 | 0.80 | 1.92 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | 600.0% | 925.0% | 400.0% | |||||

| Omnivore | Species number | 22 | 51 | 21 | 42 | 24 | 49 | |

| Density (ind./m2) | 24 | 112 | 26 | 549 | 24 | 856 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | 0.78 | 21.12 | 0.79 | 8.62 | 1.29 | 10.72 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | 366.7% | 2011.5% | 3466.7% | |||||

| Scavenger | Species number | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | - | 4 | |

| Density (ind./m2) | 3 | 3 | 7 | 8 | - | 1 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | 4.10 | 9.48 | 0.39 | 0.49 | - | 0.12 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | 0% | 14.3% | - | |||||

| Parasite | Species number | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Density (ind./m2) | - | - | - | - | - | <1 | ||

| Biomass (gWWt/m2) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.01 | ||

| Ratio of increase in density (%) | - | - | - | |||||

| Study Area and Year Classification | ES-1 | ES-2 | ES-3 | Avg. | Two-Way ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | 2021 | 2024 | Factor | Sig. | ||

| Seaweed | Diversity (H′) | 1.61 A | 1.18 A | 0.78 A | 1.16 A | 1.18 A | 1.62 A | 1.19 | 1.32 | Site | n.s. |

| Year | n.s. | ||||||||||

| Richness (R) | 5.11 A | 2.94 B,C | 3.19 A,C | 2.71 C | 4.99 A,B | 3.22 B,C | 4.43 | 2.96 | Site | n.s. | |

| Year | ** | ||||||||||

| Macrozoobenthos | Diversity (H′) | 2.18 A,B | 2.69 A | 2.07 A,B | 2.61 A | 1.59 B | 1.99 A,B | 1.94 | 2.43 | Site | n.s. |

| Year | * | ||||||||||

| Richness (R) | 10.47 A,C | 17.59 A | 8.29 C | 17.44 A | 9.40 B,C | 16.51 A,B | 9.39 | 17.18 | Site | n.s. | |

| Year | ** | ||||||||||

| Rho. | Och. | Chl. | Gra. | Car. | Sus. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seaweed | Rhodophyta | ||||||

| Ochrophyta | 0.643 | ||||||

| Chlorophyta | 0.024 | 0.571 | |||||

| Benthic Macrofauna | Grazer | 0.905 ** | 0.548 | 0.143 | |||

| Carnivore | −0.095 | 0.167 | 0.405 | −0.214 | |||

| Suspension feeder | 0.905 ** | 0.548 | 0.143 | 1.000 ** | −0.214 |

| (A) | Temp. | Rho. | Och. | Chl. | Gra. | Car. | Sus. | |

| Environmental variable | Water temperature | - | ||||||

| Seaweed | Rhodophyta | −0.071 | - | |||||

| Ochrophyta | −0.310 | 0.357 | - | |||||

| Chlorophyta | −0.500 | −0.333 | 0.357 | - | ||||

| Benthic Macrofauna | Grazer | −0.262 | 0.476 | −0.024 | −0.119 | - | ||

| Carnivore | −0.405 | 0.071 | 0.238 | 0.643 | −0.310 | - | ||

| Suspension feeder | −0.214 | 0.619 | −0.167 | −0.238 | 0.714 * | 0.119 | - | |

| (B) | Temp. | Rho. | Och. | Chl. | Gra. | Car. | Sus. | |

| Environmental variable | Water temperature | - | ||||||

| Seaweed | Rhodophyta | 0.048 | - | |||||

| Ochrophyta | 0.024 | 0.599 | - | |||||

| Chlorophyta | −0.216 | 0.545 | 0.855 ** | - | ||||

| Benthic Macrofauna | Grazer | −0.405 | 0.548 | 0.455 | 0.507 | - | ||

| Carnivore | −0.762 * | −0.238 | −0.503 | −0.203 | 0.000 | - | ||

| Suspension feeder | −0.286 | 0.714 * | 0.347 | 0.520 | 0.690 | 0.048 | - | |

| (C) | Temp. | Rho. | Och. | Chl. | Gra. | Car. | Sus. | |

| Environmental variable | Water temperature | - | ||||||

| Seaweed | Rhodophyta | −0.119 | - | |||||

| Ochrophyta | −0.262 | 0.905 ** | - | |||||

| Chlorophyta | 0.180 | 0.467 | 0.611 | - | ||||

| Benthic Macrofauna | Grazer | 0.238 | 0.810 * | 0.643 | 0.371 | - | ||

| Carnivore | −0.024 | 0.548 | 0.619 | 0.563 | 0.500 | - | ||

| Suspension feeder | 0.333 | 0.500 | 0.333 | 0.287 | 0.429 | −0.095 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hwang, C.-H.; Jin, G.; Kim, D.Y.; Jang, J.-G.; Oh, J.C.; Bae, C.S.; Park, J.M. Ecological Effects of Seaweed Restoration on Benthic Macrofauna in Marine Forest Development Areas Along the Eastern Coast of Korea. Diversity 2026, 18, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010027

Hwang C-H, Jin G, Kim DY, Jang J-G, Oh JC, Bae CS, Park JM. Ecological Effects of Seaweed Restoration on Benthic Macrofauna in Marine Forest Development Areas Along the Eastern Coast of Korea. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Choul-Hee, Gayoung Jin, Do Yeon Kim, Jae-Gil Jang, Ji Chul Oh, Chang Soo Bae, and Joo Myun Park. 2026. "Ecological Effects of Seaweed Restoration on Benthic Macrofauna in Marine Forest Development Areas Along the Eastern Coast of Korea" Diversity 18, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010027

APA StyleHwang, C.-H., Jin, G., Kim, D. Y., Jang, J.-G., Oh, J. C., Bae, C. S., & Park, J. M. (2026). Ecological Effects of Seaweed Restoration on Benthic Macrofauna in Marine Forest Development Areas Along the Eastern Coast of Korea. Diversity, 18(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010027