Abstract

At COP16 in Cali, Colombia, significant progress was made in biodiversity conservation efforts. In this regard, financing has been considered a key issue for achieving the objectives. The overview of Mexico’s experience with biodiversity finance in this study presents the experience of an emerging economy, which must finance pressing development priorities and biodiversity and climate action at the same time. Therefore, it is very important to find synergies in the available finance and look for new innovative options. The large overlap between the climate and biodiversity agendas and the international commitments derived from these also presents an opportunity to accelerate biodiversity funding. The methodology applied is the Systematic Literature Review (SLR). The study presents the national strategy on biodiversity in Mexico (ENBioMex), the financial needs of the country, and the existing biodiversity financing, stressing the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), the Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN), and the Adaptation Fund in Mexico. The discussion section centers on analyzing the existing results and outlining some proposals to enhance the existing instruments, looking for innovation and synergies. In the authors’ opinion, the financing of Ecosystem-based Adaptation (EbA) is the main instrument that can link biodiversity conservation and adaptation to climate change impacts, at the same time providing a sustainable way of life and guaranteeing the well-being of communities, but it is not adequately used. Finally, we present some concluding remarks and future research topics.

1. Introduction

We are witnessing an unprecedented crisis of biodiversity loss on a global scale. Ecosystems that have thrived for millennia are now teetering on the brink as forests are cleared, wetlands drained, and irretrievable coral reefs bleached. This rapid disappearance of habitats is not just a loss of beauty or nature but has devastating consequences for humanity [1].

There is a growing concern that the deterioration of the natural environment is accelerating, with biodiversity declining at an unprecedented rate. WWF estimates that at least 10,000 species become extinct every year, a number that underscores the fragile interdependence of life on Earth [2]. For the billions of people who depend on these ecosystems for food, clean water, medicine and climate regulation, this crisis threatens their very survival [3]. Biodiversity erosion destabilizes economies, exacerbates poverty, and deepens inequality, creating a cascade of challenges that humanity must urgently address.

The global economy is fundamentally reliant on natural ecosystems. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), over half of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services, making it vulnerable to ecosystem degradation [4]. In its Global Risks Report 2024, the WEF identifies biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse as the third most severe perceived global risk over the next decade [5].

According to the 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), threats to species and ecosystems in oceans, coastal regions and on land, particularly in biodiversity hotspots, present a global risk that will increase with every additional tenth of a degree of warming. The transformation of terrestrial and ocean/coastal ecosystems and loss of biodiversity, exacerbated by pollution, habitat fragmentation and land use changes, will threaten livelihoods and food security [6].

At the Conference of the Parties 16 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP16) in Cali, Colombia, significant progress was made in biodiversity conservation efforts. A total of 119 countries, representing 61% of the Parties, submitted national biodiversity targets, supported by 44 countries that provided National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs). A new Program of Work was adopted to enhance the role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in biodiversity conservation, recognizing their rights and traditional knowledge [7].

Additionally, a process was established to identify and update Ecologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs) using advanced science. A groundbreaking financial mechanism, the “Cali Fund,” was created to share benefits from Digital Sequence Information (DSI), with at least 50% of funds allocated to Indigenous Peoples and local communities. These measures reflect growing global commitment to addressing biodiversity loss [8].

Parties consider a new Strategy for Resource Mobilization (The Strategy for Resource Mobilization is an essential component of global efforts to halt biodiversity loss, fostering alignment between financial systems and conservation goals while addressing the significant funding gaps in biodiversity protection) to help secure USD 200 billion annually by 2030 from all sources to support biodiversity initiatives worldwide, in line with Target 19 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF), aimed at halting or reversing biodiversity loss. Target 18 of the KMGBF also addresses the reduction of harmful incentives by at least USD 500 billion per year by 2030.

In this regard, financing has been considered a key issue for achieving the objectives; thus, an additional USD 163 million has been committed to the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund (GBFF), raising its total funding to approximately USD 396 million. Supported by governments, private entities, and philanthropic organizations, the GBFF focuses on financing impactful projects in developing regions, prioritizing nations with vulnerable ecosystems, including small island states and transitioning economies [8]. The fund accepts contributions from governments, the private sector, and philanthropies, and finances high-impact projects in developing regions, with emphasis on supporting countries with fragile ecosystems, such as small island states and economies in transition. To date, 11 donor countries as well as the Government of Quebec have pledged nearly US USD 400 million to the GBF Fund, with USD 163 million pledged during COP 16.

On the other hand, the 29th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from 11 to 22 November 2024 and its main theme is enhancing climate finance ambition, enabling action and results, including finance.

The Adaptation Fund works alongside biodiversity funds to support projects that help vulnerable communities in developing countries respond to climate change. These initiatives are tailored to each country’s specific needs, priorities, and perspectives, often leveraging nature-based solutions such as reforestation, mangrove restoration, and the recovery of habitats like coral reefs. An important component is ecosystem-based adaptation, which presents the opportunity to link climate change and biodiversity finance.

Since 2010, the Adaptation Fund has allocated over USD 1 billion to resilience and adaptation efforts, implementing 150 localized projects in highly vulnerable communities worldwide and benefiting over 38 million people. The fund also introduced Direct Access and Enhanced Direct Access mechanisms (Direct Access is a financing mechanism introduced by the Adaptation Fund that allows countries to directly access funding for climate adaptation projects without relying on intermediaries, such as international organizations. Countries can access these funds through accredited national implementing entities (NIEs), which are responsible for managing and implementing projects in line with national priorities. Enhanced Direct Access (EDA) takes this approach further by empowering national entities to not only manage funding but also make decisions on how to allocate resources at the local level. This decentralization strengthens country ownership and allows for more tailored, community-specific interventions, as well as the inclusion of local stakeholders in the decision-making process), enabling countries to directly access funding and manage projects through accredited national entities [9].

Based on the above, it is very important to tackle the insufficiency of financing in both areas, creating synergies between biodiversity conservation and climate change adaptation finance, including innovation options, and the aim of this article is to present a contribution on how to advance in this task, assessing the case of Mexico.

The article presents and analyzes the biodiversity protection strategies in Mexico, the financing instruments, and how synergy could be created between biodiversity protection and climate change adaptation. In the result section, Section 3.1 presents the national strategy on biodiversity in Mexico (ENBioMex) and the financial needs of the country, Section 3.2 is focused on the existing biodiversity financing, and Section 3.3 shows the role of GEF, BIOFIN and the Adaptation Fund in Mexico. The discussion section centers on analyzing the existing results and outlining some proposals to enhance the existing instruments, looking for innovation and synergies. Finally, we present some concluding remarks and future research topics.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology is the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) adopted from [10] based on six stages: formulation of research questions, search criteria and identification, screening process, title and abstract screening, quality assessment and data extraction. The aim of SLR in this study was to find clarity of scholarly communication, validity where the literature is defensible against bias, and audibility of the literature to obtain accurate results, and to develop a strategic recommendations approach.

The SLR methodology provides guidelines to ensure comprehensive, unbiased, and reproducible results. The review focused on identifying and analyzing studies related to biodiversity conservation and financing in Mexico. Keywords used included “Biodiversity Conservation”, “Climate Change Adaptation”, and “Ecosystem-based Adaptation”, combined with geographical and financial terms like “Mexico”, “Financing”, and “National Strategy”. Searches were conducted in Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Gray literature (GL) was included from government repositories such as INEGI, CONABIO and SEMARNAT.

The inclusion criteria comprised peer-reviewed articles, reports, and studies in English or Spanish, directly addressing biodiversity and climate finance, published between 2016 and 2024 and with contextual relevance to our study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

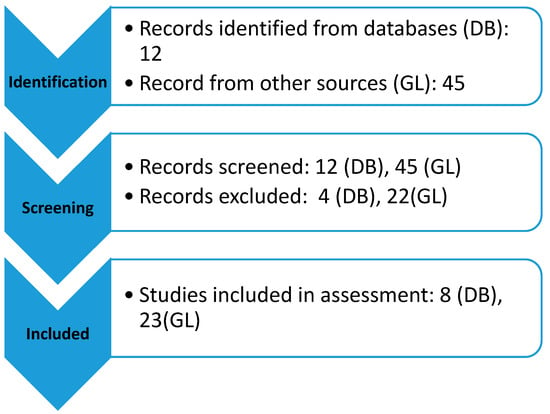

The exclusion of irrelevant papers was performed through a multistep criteria-based rigorous screening process which was purposefully designed to ensure that the selected publications were reasonably representative of the prevailing situation. As shown in Figure 1, the initial search yielded 67 documents that were broadly relevant to the study. Thereafter, these documents were screened to exclude 26 publications by only including those that were published between 2016 and 2024 (Stage 1) and did not meet the inclusion criteria of contextual relevance to this study (Stage 2). The cut-off dates were preferred because documents produced before 2016 were reasoned to be dated and unrepresentative of current perspectives. The screening yielded 31 publications, which provided this study’s final compilation of relevant publications.

Figure 1.

Screening process.

To ensure the relevance and reliability of our sources, we selected recently published documents with strong data and empirical evidence that effectively support and justify the significance of our research focus. Additionally, we examined the latest biodiversity reports in Mexico from SEMARNAT, CONANP, PNUD, INEGI, Biodiversidad Mexicana, BIOFIN, and the Adaptation Fund. These sources provided a clear understanding of the current state of biodiversity financing in Mexico, including financial needs and existing funding gaps.

Furthermore, we analyzed datasets from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Adaptation Fund in Mexico to assess their funding mechanisms, operational structures, primary beneficiaries (by sector, country, or region), and key projects financed over the past decade. Lastly, we conducted an in-depth examination of the most recent project proposals submitted to biodiversity and adaptation funds, evaluating their status, approval trends, and, where applicable, the reasons behind project rejections.

For the statistical analysis and graphical representation, the study involved downloading and systematically organizing relevant databases on biodiversity funds in Mexico. This process included classifying the data to identify key mechanisms and instruments, categorizing the types of solutions implemented, and pinpointing the institutions responsible for managing these funds. The analysis also focused on highlighting the focal areas of investment, identifying the primary beneficiary countries, and examining recently supported projects in Mexico. The structured approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of biodiversity financing dynamics and trends, supporting informed recommendations for future strategies.

For the analysis of adaptation funds in Mexico, a comprehensive database of adaptation projects was obtained and meticulously organized. The data were classified to provide insights into the number of approved projects, their duration, geographical distribution, and sectoral focus. This systematized approach enabled the generation of detailed graphs illustrating the allocation of funds across regions and sectors, offering a clear visualization of financial priorities and trends.

Additionally, an in-depth examination was conducted on each Mexican project to assess their current status. For projects that were not approved, the analysis identified specific reasons for rejection, highlighting critical gaps and challenges in meeting funding criteria. This thorough evaluation provides valuable insights into the effectiveness and alignment of adaptation funding with national and regional priorities, underscoring opportunities for improving project design and resource allocation.

3. Results

3.1. National Strategy on Biodiversity (ENBioMex)

Since Mexico joined the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, the National Biodiversity Commission (CONABIO) has been in charge of providing scientific and technical oversight for projects and negotiations under the Convention. The Biodiversity Cooperation Directorate (DCB) coordinates efforts to implement Mexico’s National Biodiversity Strategy and supports subnational studies and strategies [11].

In 2016, following a four-year review, Mexico published the National Strategy on Biodiversity and Action Plan 2030 (ENBioMex), a comprehensive framework outlining priorities for understanding, conserving, restoring, and sustainably managing biodiversity and its ecosystem services across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons [11].

In 2022, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted, requiring all Party nations to revise their biodiversity strategies to align with its objectives. This further emphasizes Mexico’s ongoing commitment to biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.

The Subnational Strategy on Biodiversity is coordinated by CONABIO, which collaborates with state governments and various sectors of society through the State Biodiversity Strategies (SBSs) initiative. This initiative aims to strengthen local human and institutional capacities for planning and managing biological resources at the state level while supporting Mexico’s commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

As part of the SBSs initiative, diverse local and regional actions are implemented in partnership with state governments to promote the conservation, protection, and sustainable use of biodiversity. These efforts also contribute to fulfilling additional national and international obligations. Key collaborations include work with the Association of State Environmental Authorities and the Central-Western Mexico Biocultural Corridor, fostering integrated approaches to biodiversity management [11].

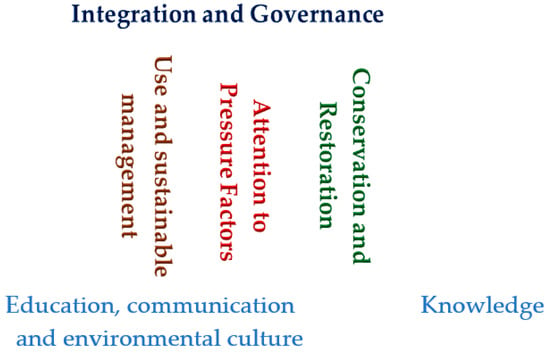

The ENBioMex has a mission, a vision for 2030, and 14 guiding principles. The Action Plan is made up of the following strategic axes: Conservation and restoration, Sustainable use and management, and Attention to pressure factors that seek to increase actions that have a positive impact on biodiversity and reduce the direct causes of biodiversity loss. Finally, but most importantly is the Integration and Governance pillar, which seeks to reinforce the implementation of actions by strengthening coordination between actors and sectors, harmonizing the legal framework, and promoting integration and cooperation (Figure 2) [9].

Figure 2.

Strategic axes of Mexico’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2016–2030. Source: produced by the authors with CONABIO Information.

The ENBioMex strategy integrates nature conservation, restoration, and sustainable use with essential pillars, including knowledge, governance, and education. However, its implementation has been inconsistent, reflecting shifts in administrative priorities. Institutions such as CONABIO, CONANP, and CONAFOR operate with a certain degree of autonomy but are subject to SEMARNAT oversight [11].

At the sub-national level, the principal policy instruments concerning biodiversity are the Strategies for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity (ECUSBE). These strategies are developed in a participatory manner at the state level in accordance with the prevailing national strategy. As of 2023, 18 such strategies have been adopted and published [11].

3.2. Importance of Financing for Biodiversity Protection in Mexico

Mexico, while comprising only 1% of the Earth’s surface, hosts over 10% of the world’s known plant and animal species, highlighting its critical role in global biodiversity conservation [12]. Safeguarding this ecological wealth is a key priority both nationally and internationally. Also, Mexico is one of the 17 world’s megadiverse nations, hosting 10–12% of all known species globally [13].

Mexico ranks third in mammal diversity with more than 564 species, 30% of which are endemic, and second in reptile diversity, with 864 species, 45% of them unique to the country. Mexico also possesses a remarkable biocultural heritage, serving as the center of origin for globally utilized species and preserving its rich natural legacy through the stewardship of Indigenous peoples and local communities. There are more than 3000 medicinal plants in the country, and more than 5000 species of flora (23%) have a traditional use [14].

In Mexico, land use is primarily concentrated on primary activities, including agriculture, extensive livestock farming, forestry, and fisheries. These activities are managed at the community level and by ejidos, which are legal entities that represent collective land ownership. To ensure the conservation of biodiversity in these territories, it is essential to consider the social governance aspects involved [15].

Indigenous Peoples, who often inhabit and protect Mexico’s most biodiverse areas, are vital environmental stewards. They have led efforts to defend ecosystems from harmful projects but face ongoing marginalization, threats, and violence. Between 2017 and 2021, 131 environmental defenders were killed in Mexico, 54 in 2021 alone—nearly half of them Indigenous—alongside frequent forced disappearances [16].

Mexico faces significant challenges that drive biodiversity loss, including overfishing, habitat loss from urbanization and agriculture, pollution, and river alteration [17]. Nearly 2600 species in Mexico are classified as endangered, threatened, or under special protection. This encompasses 97 mammal species, 232 amphibian species, and 306 fish species [18].

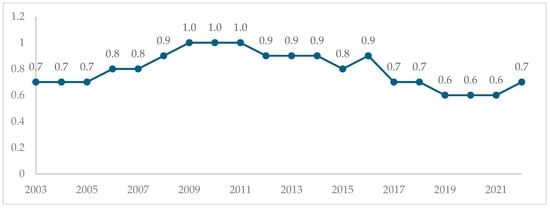

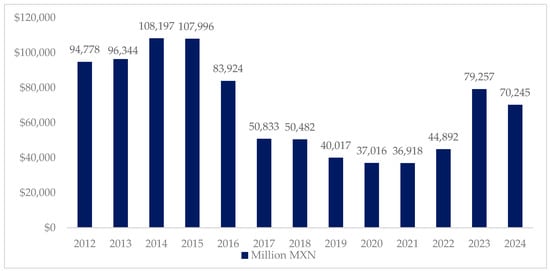

To aggravate the problem, Total Environmental Protection Spending in favor of biodiversity has been decreasing since 2013, allocating only 14.1 billion Mexican pesos in 2022, marking the lowest investment in a decade (0.7% of GDP) [15] (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Public Expenditure on Environmental Protection as % of GDP, 2003–2022. Source: [19].

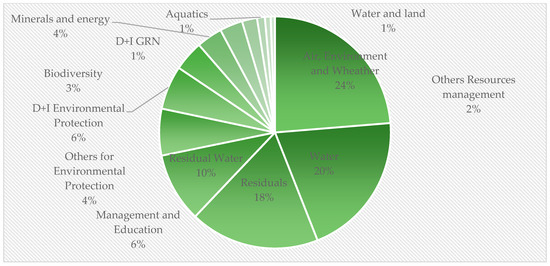

Figure 4 shows how public spending on environmental protection is distributed by sector. Air, Environment and Water appears to be the sector most benefited (24%), followed by Water (20%), Waste (18%) and Wastewater (10%). Spending on biodiversity is only 3%, and on environmental protection 10.3%. We can appreciate that biodiversity is in last place in this spending.

Figure 4.

Total Public Sector Environmental Protection Expenditure by Functional Classification, 2022. Source. [20].

Despite the notable expansion of Mexico’s national protected areas, the environmental sector’s budget, including funding for pivotal agencies like CONABIO and CONANP, has experienced a decline over the past decade (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Approved budget for Branch 16: Environment and Natural Resources for the period 2012–2024, in million MXN. Source: [11].

Mexico has significantly expanded its national protected areas, now 232 sites and covering nearly 95 million hectares—over a third of the country’s land area [13]. However, the 2023 budget for CONANP was 7% lower than the previous year, amounting to less than USD 1 per hectare of protected land. In general, the total budget assigned to Branch 16—Environment and Natural Resources—for 2025, is just over MXN 44,370 million, while in 2024, the amount assigned was MXN 70,245 million.

According to [21] the percentage of Protected Natural Areas with a management program in place that maintain or achieve an effectiveness index at an outstanding or high level according to the “i-effectiveness” was reported as 49.6% in 2020 and 50% in 2022 and 2024.

3.2.1. Financial Needs Related to ENBioMex Strategic Axes

According to UNDP, the estimated annual financial need for biodiversity in Mexico during 2017–2020 was approximately USD 461.9 million annually, reflecting a 46.7% increase compared to biodiversity spending in 2015. This financial assessment encompassed several key areas [21]:

- Protected Natural Areas (PNA): A funding shortfall of USD 60 million per year, as estimated by CONANP.

- Payment for Environmental Services (PES): A funding requirement of USD 202.1 million annually, identified by CONAFOR to meet demand.

- National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP–ENBioMex): An estimated annual need of USD 191.4 million for effective implementation.

ENBIOMEX’s Finance Needs:

- Strategic priority 1 Knowledge: USD 55.4 million (12%)

- Strategic priority 2 Conservation and restoration: USD 350.8 million (76%) [Includes the financial gap of PNA calculated by CONANP and the estimate of finance needs to cover the demand for CONAFOR’s PES]

- Strategic priority 3 Sustainable use and management: USD 25.8 million (5.6%)

- Strategic priority 4 Attention to negative drivers and threats: USD 19.9 million (4.3%)

- Strategic priority 5 Education, communication and environmental culture: USD 3.6 million (0.8%)

- Strategic priority 6 Integration and governance: USD 6.2 million (1.3%)

The assessment also revealed that 76% of the required resources pertain to recurrent expenditures, while the remaining 24% are allocated for investment spending [22].

3.2.2. Financial Needs Beyond ENBioMex

There are other needs that must be considered, i.e., some actions indirectly affecting biodiversity should be considered, for instance the Environmental Degradation and Resource Depletion Total Costs. As shown in Table 2, in 2022, the National Institute of Geography and Statistics (INEGI) reported that environmental degradation and resource depletion imposed costs equivalent to 4.11% of national GDP, of which degradation represented the equivalent of 3.63%, while depletion was equivalent to 0.48% [15].

Table 2.

Composition of Depletion and Environmental Degradation Costs in 2022.

3.3. Financial Funds Focused on Biodiversity in Mexico

The main economic instruments and mechanisms for environmental management in Mexico identified as of 2018 can be classified into market-based, fiscal, regulatory, risk-related and environmental funds [22].

Market-Based Instruments include diverse solutions such as carbon markets, eco-labels, sustainability standards for products and services, forest bonds, environmental funds, green banking, permits and licenses, access and hunting fees, sustainable species trade, ecotourism, environmental compensation, carbon taxes, payment for environmental services (water and forests), incentives for conservation and sustainable businesses, and ecological fiscal transfers. These are managed by institutions like CONANP, SEMARNAT, CONAFOR, SHCP, PROFEPA, FMCN, GRAF, Profauna, and Aguas de Saltillo [22].

Risk Instruments involve environmental and climate insurance schemes, such as those for coral reef restoration and livestock protection in agriculture. Grants include Official Development Assistance (ODA), donations, and private funding mobilized through mechanisms like international biodiversity financing and philanthropy [23].

Regulatory Instruments focus on intersectoral approaches, fishing quotas, and addressing harmful subsidies in agriculture. Key players include SEMARNAT, SAGARPA, CONAPESCA, EDF, and COBI [20].

Environmental Funds are overseen by CONABIO, SEMARNAT, CONAFOR, FMCN, subnational governments, and FONCET. These funds support biodiversity conservation, forest management, protected areas, climate change mitigation, and specific species protection, such as efforts for the Monarch Butterfly [23].

3.3.1. Global Environment Facility (GEF) in Mexico

GEF is a multilateral fund focused on the fight against biodiversity loss, climate change and pollution, and supporting land and ocean health. Financing allows developing countries to face challenges and achieve objectives related to environmental goals. The partnership incorporates 186 member governments, civil society, Indigenous Peoples, women and youth.

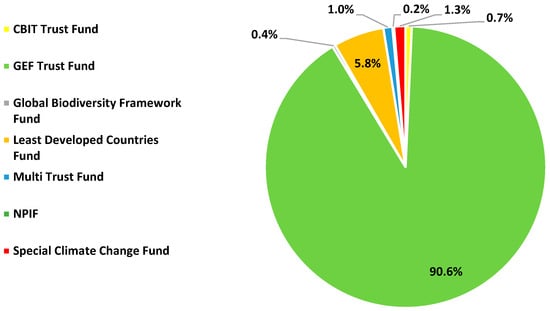

Operating for over 30 years, GEF has allocated more than USD 25 billion in funding and mobilized an additional USD 145 billion for country-driven priority projects. As Figure 5 shows the fund group includes the Global Environment Facility Trust Fund, Global Biodiversity Framework Fund (GBFF), Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), Nagoya Protocol Implementation Fund (NPIF), and the Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency Trust Fund (CBIT) [23]. These investments have been pivotal in addressing biodiversity loss, climate change, land degradation, and other pressing environmental challenges.

According to the GEF, USD 25.5 billion has been allocated to 6155 projects worldwide. The main agencies involved in funding these initiatives are the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), followed by the World Bank and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

GEF’s funding is managed through a group of specialized funds, each tailored to specific environmental goals. The Global Environment Facility Trust Fund serves as the primary financial mechanism, accounting for 91% of the total funding. The Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), which supports climate adaptation initiatives in the most vulnerable nations, contributes an additional 6%. The remaining funds, each representing approximately 1%, include:

- The Global Biodiversity Framework Fund (GBFF), which aligns with biodiversity targets under the Kunming-Montreal Framework;

- The Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), addressing urgent climate adaptation and mitigation needs;

- The Nagoya Protocol Implementation Fund (NPIF), promoting the fair and equitable sharing of benefits derived from genetic resources;

- The Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency Trust Fund (CBIT), enhancing countries’ ability to meet transparency requirements under the Paris Agreement (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Main Focal Areas for GEF Project. Source [22].

Figure 6. Main Focal Areas for GEF Project. Source [22].

This diversified structure enables GEF to target a wide range of environmental priorities while maximizing the impact of its financial resources. Its comprehensive approach underscores its vital role in bridging financial gaps and supporting global efforts to achieve sustainable development and environmental resilience.

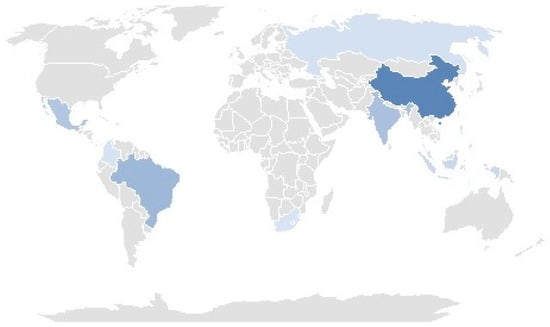

Grant amounts are between USD USD 7000 and USD 306 million and the main funding source is GEF Trust Fund with 91% of grants. Geographically, most of the grants are designated to Global projects, but the most benefited countries are China, Brazil, India, Mexico, Indonesia, Russia, Colombia, Philippines and South Africa (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Countries benefiting most from GEF grants (USD millions). The darker color indicates greater access to funds. Source: Produced by the authors with data of [13,23].

Table 3 presents all the projects related to Biodiversity in Mexico approved by GEF Fund in the last ten years (2014–2024). The biggest project by GEF grant is “Sustainable Productive Landscapes”, followed by “Mex30×30: Conserving Mexican biodiversity through communities and their protected areas” and “ORIGEN: Restoring Watersheds for Ecosystems and Communities”. The agency which manages more projects is the UNDP, and the main funding source is GEF Trust Fund. The amount of the grants has increased in 2023 and 2024.

Table 3.

GEF Projects in Mexico related to Biodiversity (2014–2024).

Over the years, GEF projects in Mexico have demonstrated significant advances in funding and implementation. The GEF Trust Fund emerges as the primary funding source, supporting the majority of initiatives. Recent years, particularly 2023 and 2024, have seen an increase in project size, with substantial grants allocated to projects such as “Mex30×30” (USD 16.6 million) and “ORIGEN” (USD 14.3 million). This reflects a growing emphasis on large-scale biodiversity conservation and restoration efforts.

The projects cover a wide range of focus areas, including ecosystem restoration, biodiversity conservation, sustainable agriculture, and tourism. For instance, “Promoting sustainability in the agave-mezcal value chain” highlights sustainable agricultural practices in biocultural landscapes, while “From bait to plate” focuses on marine biodiversity and food security. These initiatives underline the strategic diversification of biodiversity efforts in Mexico, addressing both terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Key implementing agencies play a pivotal role in delivering these projects. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) lead multiple projects, demonstrating their centrality in biodiversity initiatives. Additionally, organizations like Conservation International manage impactful projects such as “Mex30×30” and “ORIGEN,” underscoring their influence in driving conservation efforts.

Cofinancing stands out as a major strength of GEF projects in Mexico. Many initiatives secure cofinancing amounts significantly higher than the GEF grants. For example, “COBIOCOM” leveraged USD 252.8 million in cofinancing compared to its USD 8.9 million GEF grant, while “ORIGEN” obtained USD 145.1 million in cofinancing alongside its USD 14.3 million grant. This demonstrates the ability of GEF projects to attract additional financial resources, amplifying their impact.

Specific regions and ecosystems are prioritized in these projects, such as the Biocultural Corridor of Central West Mexico and priority landscapes in Oaxaca and Chiapas. Marine and coastal ecosystems also receive attention, with projects like “Mainstreaming Biodiversity Conservation in Mexico Tourism Sector” addressing biodiversity in tourism-rich coastal areas. However, certain critical areas, such as invasive species management and genetic diversity conservation, receive relatively smaller grants, indicating potential gaps in funding allocation [23].

The involvement of local communities is notable in initiatives like the Small Grants Program, which focuses on grassroots-level interventions. Despite their relatively smaller size, these projects emphasize community-driven biodiversity efforts, suggesting opportunities to scale such initiatives for broader impact.

3.3.2. The Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) in Mexico

BIOFIN was initiated in 2014 at the CBD COP 11, by UNDP and the European Commission, in response to the urgent global need to divert more finance from all possible sources towards global and national biodiversity goals. Now present in 40 countries, BIOFIN is working with governments, civil society, vulnerable communities, and the private sector to catalyze investments in nature.

The UNDP’s BIOFIN FNA initiative has taken a crucial first step by identifying financial needs and outlining a pathway for ENBioMex implementation until 2025. It has also fostered collaboration with subnational governments, the private sector, and civil society, facilitating dialogue, generating synergies, and aligning potential financing mechanisms to target biodiversity needs effectively.

Currently, BIOFIN MX is developing concrete resource mobilization proposals, focusing on identifying funding sources, mechanisms for resource allocation, instruments, expected financial outcomes, and necessary institutional arrangements.

So far BIOFIN MX has identified four types of financing solutions:

- Increasing resources from different sources (public, private and social),

- Efficient spending to improve results, aligning programs and budgets across sectors,

- Reducing future costs of negative impacts.

- Also, there are financial solution proposals like: integration of biodiversity (mainstreaming), Climate and Biodiversity Finance, Financial mechanisms of conservation, Sustainable business and impact investment, Greening the financial system, Support solutions (International finance vision and Economic and finance analysis) [24].

As of November 2024, BIOFIN has calculated the biodiversity expenditure, identified the biodiversity needs to be covered, calculated the financial gap for conservation, and developed a plan for financing solutions.

Currently, BIOFIN Mexico has a portfolio of more than 25 financing mechanisms grouped into five main financial solutions (FS): 1. Greening financial flows in cross-sectoral policies. 2. Strengthening financial mechanisms for climate change and biodiversity. 3. Strengthening biodiversity at the subnational level. 4. Bioeconomy. 5. Greening of development and commercial banks [25].

According to UNDP, in terms of climate finance and biodiversity, some mechanisms have been proposed and integrated in Mexico, particularly in some states [24].

1. The Sustainable Fund. The main purpose is to develop and implement a financial mechanism to channel resources toward sustainable development projects in the country, focusing on environmental and biodiversity goals, as a response to the elimination of public trusts.

In Jalisco, funding strategies have been implemented to address biodiversity, climate change, and other environmental degradation challenges. The plan integrates the following activities: (1) Assess the state’s existing financing mechanisms, (2) Develop a financial solutions plan to meet biodiversity needs and align with state and national commitments, (3) Evaluate and align Jalisco’s four public trusts (environmental, forestry, entrepreneurship, and agricultural), including legal, operational, and regulatory aspects, to optimize resource use and enhance their effectiveness [24].

2. Creation of the Green Investments Office (OIV) and the reinforcement of the Public Environmental Fund (FAP) in Mexico City. In this regard, BIOFIN has supported SEDEMA in strengthening the Public Environmental Fund to promote the allocation of resources through innovative financial mechanisms for projects in sustainable development, biodiversity conservation and sustainable use, and climate change adaptation and mitigation.

This FAP will serve as the focal point and single window for Mexico City to engage with national and international providers of financing and technical assistance in these areas. Additionally, institutional and financial capacities will be enhanced to transform the fund into an effective tool for selecting, evaluating, and financing environmental, climate change, and biodiversity projects [25].

3. Forest Carbon Credits, for which BIOFIN has proposed several initiatives. These include assessing the feasibility of complementary financing mechanisms to ensure the sustainability of forest projects, emphasizing the benefits of such initiatives to influence public policy and private sector strategies, and documenting the development process to provide replicable recommendations for scaling up forest carbon projects in Mexico.

Promising results have been achieved in Mexico City. The Public Environmental Fund (FAP) has been strengthened, leveraging financial resources from international sources such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the Spain-Mexico Mixed Fund, and the UK Embassy. Additionally, a fiduciary change resulted in savings of USD 3 million, which were redirected to conservation activities, achieving budget efficiency of USD 28 million. The reception and execution processes for international funding have also been systematized to enhance operational efficiency.

In addition, SEDEMA and Mexico City government officials have been trained and the legal and operational structure of the Public Fund for the Environment has been improved. Key areas included financial structuring, risk management, credit and financial instruments, international resource mobilization, audit and internal control, project appraisal methodologies, and development of regulatory and operational frameworks for funding. The process of strengthening the fund was systematized to enable its replication in other Mexican states [25].

Efforts in Jalisco included revising and updating fund operating rules and contracts while creating a linkage strategy to avoid duplication and enhance efficiency. Of 49 identified financial mechanisms, six were prioritized for implementation through a workshop with strategic stakeholders. A state financing solutions plan was developed, aligned with the State Biodiversity Strategy. Capacity-building initiatives were conducted for SEMADET, alongside establishing frameworks for investment selection and impact measurement for state environmental funds, ensuring alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

3.3.3. The Adaptation Fund in Mexico

The Adaptation Fund provides financial support for projects that assist vulnerable communities in developing countries in adapting to climate change, with a particular focus on local needs and priorities. Since 2010, the Fund has allocated over USD 1.2 billion to 176 localized projects, which have benefited more than 45 million people. Furthermore, the Fund introduced Direct and Enhanced Direct Access, which enables countries to develop and manage projects through accredited national entities [26].

The Adaptation Fund is financed through government and private donations, as well as a 2% levy on Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) from Clean Development Mechanism projects under the Kyoto Protocol.

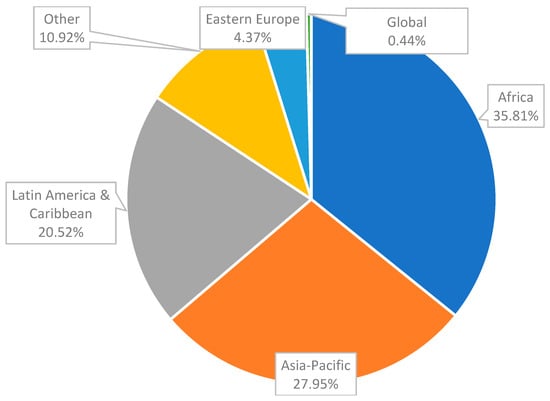

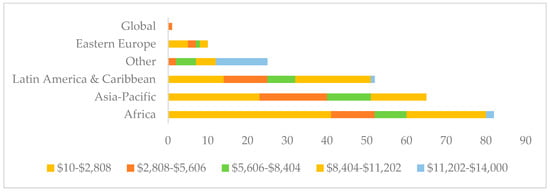

According to the Database of Adaptation Fund to November 2024, 233 projects were approved. The project duration is between 0.5 and 6 years. The regional share of the projects is 36% in Africa, 28% in Asia-Pacific, 21% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 4% in Eastern Europe (Figure 8). In terms of the duration of the projects, most of them are between 3 and 5 years (64%), but also a quarter are for less than 1 year [25].

Figure 8.

Adaptation Fund Projects by Region. Source: [26].

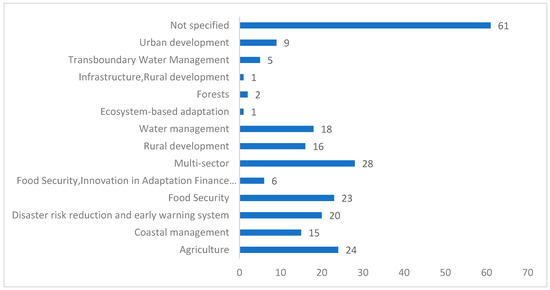

As observed in Figure 9, the majority of the projects are focused on Multi-sector (28), followed by Agriculture (24), Food security (23), Disaster risk reduction and early warning system (20), Water management (18), Rural Development (16). It is important to highlight that only 1 project of the Adaptation Fund in 2024 was oriented to ecosystem-based adaptation.

Figure 9.

Adaptation Fund Projects by Sector, 2024. Source: Produced by the authors with data from [26].

Most of the projects are in the implementation phase (114), 73 projects have been completed and 38 have been approved. Grant amounts range from USD 10,000 to 14,000,000. Almost half of the projects are below USD 2.8 million and an important portion are between USD 8.4 and 11.2 million (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Adaptation Fund by Grant Amount and Region (thousands USD). Source: Produced by the authors with data from [27].

According to adaptationfund.org Mexico has received one support for USD 25,000 related to “Technical assistance grant for the environmental and social policy and gender policy (ta-esgp)” requested by Mexican Institute of Water Technology (IMTA) Mexico. The project was developed from 5 January to 31 October 2021 [28].

The support activities were related to the development of procedures/manuals/guidelines for screening projects for: (i) environmental, social and gender risks; (ii) conducting environmental, social and gender risk assessments of projects and formulating gender-sensitive risk management plans; (iii) public disclosure and gender-sensitive consultation; (iv) developing transparent, accessible, fair and effective mechanisms for receiving and addressing complaints of environmental or social harm and complaints related to gender inequality and other adverse gender impacts caused by projects/programs during implementation; and (v) training selected staff to carry out relevant tasks related to the implementation of the Fund’s environmental and social policy and gender policy [27].

Other adaptation fund projects submitted but not accepted are: (1) “Restoration of Lake Texcoco through resilient actions” and (2) “Ha Ta Tukari, “Water for Life”. In both cases, projects did not clarify climate vulnerabilities in the target areas, define the target beneficiary communities, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness of concrete activities, and compliance with the Environmental and Social Policy and Gender Policy of the Fund [28].

4. Discussion

It is well established that biodiversity loss and climate change are correlated and mutually reinforcing. A thriving nature keeps carbon stored where it naturally belongs and not in our planet’s atmosphere. Biodiversity enhances adaptation capacity and resilience, including in disaster-risk reduction. Climate change, on the other hand, is one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss.

Available adaptation options can reduce risks to ecosystems and the services they provide, but they cannot prevent all changes and should not be regarded as a substitute for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Ambitious and swift global mitigation offers more adaptation options and pathways to sustain ecosystems and their services [6].

The overview of Mexico’s experience with biodiversity finance in this study presents the experience of an emerging economy, which must finance pressing development priorities and biodiversity and climate action at the same time. However, the 2025 Federal Expenditure Budget of Mexico reflects significant cuts in the environmental sector, which complicates the outlook. The total budget allocated to Branch 16 (Environment and Natural Resources) was reduced by almost 40%, from MXN 70,245 million in 2024 to just MXN 44,370 million in 2025 [29]. Therefore, it is very important to find synergies in the available finance and look for new innovative options.

Mexico is an extraordinarily biodiverse country with a long history of sustainably using natural resources. The country’s most important policy instrument on biodiversity protection, the National Biodiversity Strategy of Mexico, explicitly connects nature conservation, restoration and sustainable use with key supporting elements, such as knowledge, good governance and mainstreaming, and education.

The National Strategy on Biodiversity and Action Plan 2030 (ENBioMex) should be outlined as a positive achievement, as well as the definition of financing needs for biodiversity protection. The strategy is developed at both national and subnational (state) levels to establish the bases to promote, guide, coordinate and harmonize government and society efforts for conservation, sustainable use and the fair and equitable distribution of the benefits derived from the use of biological diversity components and their integration into sectoral priorities of the country [30].

CONABIO collaborates with state governments and various sectors of society through the State Biodiversity Strategies (EEB) initiative. This initiative aims to strengthen local human and institutional capacities for planning and managing biological resources at the state level while supporting Mexico’s commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity. Important achievements include the establishment of 232 Natural Protected Areas and Marine Protected Areas. Another positive development is the growing inclusion of Indigenous Communities, women, and youth as stewards of biodiversity conservation.

However, in the last decade, public funding has suffered a significant decrease, not only for biodiversity but in the environmental field in general. The incorporation of Mexico into global initiatives such as BIOFIN marks important steps to improve funding, but the effective implementation of the suggestions and recommendations of such initiatives remains a challenge. The total budget assigned to Branch 16—Environment and natural resources—for 2025 is just over MXN 44,370 million, while in 2024, the amount assigned was MXN 70,245 million [29]. Additionally, the ratio between the amount invested in environmental protection and the amount for environmental depletion and degradation is 6:1. Therefore, it is necessary to increase financing oriented to environmental depletion and degradation.

A positive development is that GEF funding for Mexico has increased between 2014 and 2024. Additionally, Mexico is one of the most benefited countries along with China, Brazil, and India.

The large overlap between the climate and biodiversity agendas and the international commitments derived from these also presents an opportunity to accelerate biodiversity funding. Biodiversity-related commitments derived from climate instruments, such as Mexico’s nationally determined contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement, can help leverage resources. In the Adaptation Fund projects by region, Latin America and the Caribbean are in third place after Africa and Asia and the Pacific.

However, our results show that only 1 project of 229 financed by the Adaptation Fund in 2024 was oriented to ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA). It is reported that in the case of Mexico, some projects were not accepted because they did not clarify climate vulnerabilities in the target areas, define the beneficiary communities, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness of concrete activities, and compliance with the Environmental and Social Policy and Gender Policy of the Fund.

In our opinion, the financing of EbA is the main instrument that can link biodiversity conservation and adaptation to climate change impacts while providing a sustainable way of life and guaranteeing the well-being of communities, but it is not adequately used. We assume this is because community-based conservation (CbA) has been primarily championed by development practitioners, and EbA by environment/conservation practitioners. Additionally, EbA is a subset of Nature based Solutions (NbS), which is an umbrella term for conservation, restoration and sustainable use of nature to address societal challenges. Thus, EbA harnesses biodiversity and ecosystem services to increase resilience and reduce the vulnerability of human communities and natural systems to climate change.

That is why it is necessary to implement some actions that would foster EbA, and in general biodiversity financing, addressing the following issues: Gender imbalance in access to climate and EbA information; Difference in risk perceptions (what is at risk and why); Including Indigenous knowledge and traditional governance systems and participatory processes; Providing funding for project upkeep and management; Defining limits and thresholds under which EbA might not deliver expected benefits; Addressing the mismatch of governance (borders, jurisdictions) vs. problem scales (climate hazards and ecosystems).

It is necessary to strengthen Mexico’s biodiversity financing through improvements in its investment targeting, effective coordination among institutions, empowerment of local communities, and by increasing support for innovative production schemes in coordination with other actors such as the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food. In this context, it is important to communicate the financing targets and models to all actors working in their implementation to ensure broad understanding; create incentives for interagency coordination; build capacity for all actors to help them meet their new functions; strengthen of the role that state governments play in the harmonization of public policies that affect their regions; and strengthen the role that local communities play to identify and develop intervention strategies that really address local needs and specificities.

In summary, Mexico’s experiences indicate the importance of political will to promote interagency coordination that leads to comprehensive intervention strategies in contexts with different historical, social, environmental and economic values.

5. Conclusions

Maintaining planetary health is essential for human and societal health and a pre-condition for climate resilient development. Effective ecosystem conservation of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean areas, including all remaining areas with a high degree of naturalness and ecosystem integrity, will help protect biodiversity, build ecosystem resilience and ensure essential ecosystem services.

In these concluding remarks we summarize some main issues based on our results and discussion of the Mexican case to formulate recommendations for the biodiversity conservation and climate adaptation financing agendas, which are of utmost importance to overcome the funding deficit in countries of the Global South.

The host government’s theme for COP 16 on Biodiversity was ’Making Peace with Nature’. Encouraging was the decision on climate change and biodiversity loss, as well as the attention to the need to align related international efforts. These crises are inextricably linked, and we cannot tackle one without the other.

One important outcome was that COP 16 of CBD committed to enhancing policy coherence, including a potential joint work program of the three Rio conventions, namely the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). The details of this collaboration should be further specified both in international fora and in academic research.

The subjects for future research are to explore how to more effectively bring these agendas together, to create synergies tackling biodiversity loss, planetary health, and climate change adaptation issues.

An obligatory task would be to generate precise methodologies for Monitoring and Evaluating outcomes and benefits of EbA projects and other financing oriented to attend biodiversity and climate adaptation priorities.

Because of the decrease in governmental funding, it is imperative to explore financial innovation in market-based instruments, risk instruments, and outcome-based and impact projects. Another challenge is to develop new varieties of blended finance, combining governmental, private and international funding. In this context, it is very useful to share information on cases of success in innovative financing.

It is important to make information on the requisites to apply for Adaptation Fund Financing more transparent and accessible and provide more orientation on Ecosystem-based Adaptation that is directly related to biodiversity conservation.

In Table 4, we highlight the main contributions that are very important to the countries of the Global South to bridge the funding gap for conserving biodiversity, adapting to the impacts of climate change, and creating constructive synergies. Table 4 integrates key points from the discussion and conclusion sections, offering a consolidated view for researchers, policymakers, and implementation stakeholders.

Table 4.

Main contributions to synergies between biodiversity and climate change adaptation financing.

To conclude, it is imperative to stress the importance of communication, capacity building, and promotion of coordination between government agencies in order to foster biodiversity conservation and to converge environmental and development agendas. It is necessary to prioritize these needs in Mexico and in the countries of the Global South.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and A.I.; methodology, A.I.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S. and A.I.; formal analysis, A.I. and M.S.; investigation, M.S.; resources, A.I.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.I.; visualization, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BIOFIN | The Biodiversity Finance Initiative |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CbA | Community-based Adaptation |

| CBIT | Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency Trust Fund |

| CERs | Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) |

| CONABIO | National Commission on Biodiversity of Mexico |

| CONAFOR | National Commission on Forestry in Mexico |

| CONANP | National Commission on Natural Protected Areas in Mexico |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| DSI | Digital Sequence Information |

| EbA | Ecosystem-based Adaptation |

| EBSAs | Ecologically Significant Marine Areas |

| ENBioMex | National Strategy on Biodiversity of Mexico |

| GBFF | Global Biodiversity Framework Fund |

| GBFF | Global Biodiversity Framework Fund |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GEF | Global Environmental Facility |

| GL | Grey Literature |

| IMTA | Mexican Institute of Water Technology |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| KMGBF | Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework |

| LDCF | Least Developed Countries Fund |

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| NBSAPs | National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans |

| NPIF | Nagoya Protocol Implementation Fund |

| ODA | Official Development Assistance |

| SAGARPA | Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries of Mexico |

| SBSs | State Biodiversity Strategies |

| SCCF | Special Climate Change Fund |

| SEMARNAT | Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources of Mexico |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| UNCCD | United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Program |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Program |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| WEF | World Economic Forum |

References

- De León, L.F.; Silva, B.; Avilés-Rodríguez, K.J.; Buitrago-Rosas, D. Harnessing the omics revolution to address the global biodiversity crisis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2023, 80, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WWF. Well... This Is the Million Dollar Question. And One That’s Very Hard to Answer. 2024. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/discover/our_focus/biodiversity/biodiversity/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Halder, M.; Jha, S. The Current Status of Population Extinction and Biodiversity Crisis of Medicinal Plants. In Medicinal Plants: Biodiversity, Biotechnology and Conservation; Jha, S., Halder, M., Eds.; Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. Global Competitiveness Report Special Edition 2020: How Countries are Performing on the Road to Recovery. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-global-competitiveness-report-2020/ (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- WEF. Global Risks Report 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2024/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- IPCC. Fact Sheet—Biodiversity. Climate Change Impacts and Risks. SIXTH ASSESSMENT REPORT, Working Group II—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/outreach/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FactSheet_Biodiversity.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- COP-16. COP-16 Calí, Colombia, Paz con la Naturaleza. 2024. Available online: https://www.cop16colombia.com/es/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- CBD. Biodiversity COP 16: Important Agreements Reached Towards Making Peace with Nature. 2024. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/article/agreement-reached-cop-16 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- NDC Partnership. Adaptation Fund. 2024. Available online: https://ndcpartnership.org/knowledge-portal/climate-funds-explorer/adaptation-fund#:~:text=The%20Adaptation%20Fund%20finances%20projects,country%20needs%2C%20views%20and%20priorities (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONABIO (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). Para Alcanzar Sus Objetivos y Cumplir Sus Funciones, la CONABIO Financia Proyectos de Temas Sobre el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conabio/acciones-y-programas/proyectos-56730 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Guzmán, S.; Velasco, A.; Barbosa, O. Biodiversity Finance in Mexico. A Fair Share of Biodiversity Finance? Perspectives from Developing Countries. ODI Country Study. 2024. Available online: https://media.odi.org/documents/Biodiversity_finance_in_Mexico_country_study.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- GEF. Global Biodiversity Framework Fund. 2024. Available online: https://www.thegef.org/what-we-do/topics/global-biodiversity-framework-fund (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- SEMARNAT. México, Segundo Lugar del Mundo en Bioculturalidad. 2018. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/articulos/mexico-segundo-lugar-del-mundo-en-bioculturalidad?idiom=es (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- PNUD Mexico. Biodiversity Expenditure Review. September, 2024. PNUD. Available online: www.biodiversityfinance.org/mexico (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Martínez-Tomás, S.H.; Tavera-Cortés, M.E. Nature-Based Solutions for Conservation and Food Sovereignty in Indigenous Communities of Oaxaca. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.E.; Sundaram, A. The Deadly Costs for Mexico’s Indigenous Communities Fighting Climate Change. Opinion. 2023. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2023-02-26/us-mexico-border-indigenous-climate-change-environment (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- SEMARNAT. Conoce las Categorías de Riesgo de la NOM 059 SEMARNAT-2010 Para Especies de Flora y Fauna. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/articulos/conoce-las-categorias-de-riesgo-de-la-nom-059-semarnat-2010-para-especies-de-flora-y-fauna (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List od Endangered Species. 2024. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- INEGI CEEM. Cuentas Económicas y Ecológicas de México 2022. Comunicado de Prensa Número 755/23 1 de Diciembre de 2023 Página 1/7. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2023/CEEM/CEEM2022.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- CONANP. Programa Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas 2020—2024. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. 2024. Available online: https://www.conanp.gob.mx/datos_abiertos/DES/PNANP2020-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- UNDP. BIOFIN Executive Summary Phase I: Results and Biodiversity Finance Solutions. The Biodiversity Finance Initiative. United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Available online: https://www.biofin.org/knowledge-product/executive-summary-phase-i-results-and-biodiversity-finance-solutions (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- GEF. GEF Projects Database. 2024. Available online: https://www.thegef.org/projects-operations/database (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- UNDP. Plan de Soluciones de Financiamiento BIOFIN 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.biofin.org/sites/default/files/content/knowledge_products/PSF-BIOFIN.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- UNDP México. Análisis de Gasto Público Federal a Favor de la Biodiversidad 2022. Proyecto 00108628 Iniciativa Finanzas de Biodiversidad BIOFIN México Fase II. 2024. Available online: https://www.biofin.org/sites/default/files/content/knowledge_products/050924_BER_Disen%CC%83o.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Adaptation Fund. Helping Developing Countries Build Resilience and Adapt to Climate Change. 2024. Available online: https://www.adaptation-fund.org/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Adaptation Fund Board. Project and Programme Review Committee Thirtieth Meeting Bonn, Germany, 11–12 October 2022. Available online: https://www.adaptation-fund.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/AFB.PPRC_.30.21-Proposal-for-Mexico-2.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Adaptation Fund Board. Technical Assistance Grant for the Environmental and Social Policy and Gender Policy (ta-esgp)—Mexican Institute of Water Technology (IMTA) Mexico. Project and Programme Review Committee. 2020. Available online: https://www.adaptation-fund.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/AFB.PPRC_.26-27.3-TAESGP-Grant-proposal-for-Mexico_final.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Greenpeace México. El Proyecto de Presupuesto para 2025 Recorta Todavía Más los Recursos para Proteger el Medio Ambiente. 2024. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/mexico/noticia/54846/el-proyecto-de-presupuesto-para-2025-recorta-todavia-mas-los-recursos-para-proteger-el-medio-ambiente (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Biodiversidad Mexicana. La Estrategia Nacional sobre Biodiversidad de México (ENBioMex). 2016. Available online: https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/pais/enbiomex (accessed on 12 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).