Abstract

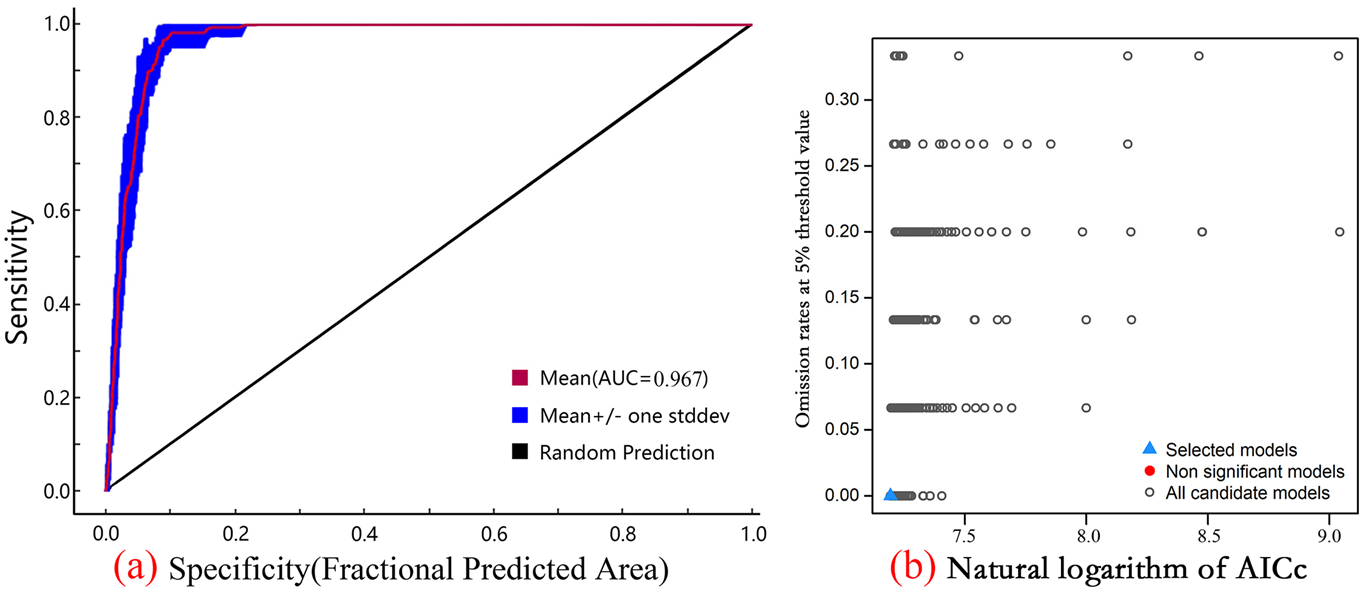

The Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) model, integrated with ArcGIS (a geographic information system), was employed to project potential species distribution under current conditions and future climate scenarios (SSP1–2.6, SSP2–4.5, SSP5–8.5) for the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s. Model optimization involved testing 1160 parameter combinations. The optimized model (FC = LQ, RM = 0.1) exhibited significantly improved predictive performance, with an average AUC of 0.967. Under current conditions, the estimated core suitable habitat spans 35.62 × 104 km2, primarily located in southern China. Future projections indicated a non-linear trajectory: an initial contraction of total suitable area by mid-century, followed by a substantial expansion by the 2090s, particularly under high-emission scenarios. Simultaneously, the distribution centroid shifted northwestward. The primary factors influencing distribution were the annual mean temperature (Bio1, 41.1%) and the precipitation of the coldest quarter (Bio19, 20.0%). These findings establish a critical scientific basis for developing climate-adaptive conservation strategies, including the identification of priority climate refugia in Fujian province, China, and planning for assisted migration to northwestern regions.

1. Introduction

Global climate change is significantly disrupting ecosystem stability and biodiversity, resulting in notable shifts in species distribution patterns [1]. The interplay of climate change and anthropogenic activities has caused extensive habitat loss and fragmentation [2], driving numerous species toward regional extinction [3]. Historical evidence, including range contractions during the Last Glacial Maximum, highlights the sensitivity of species distributions to climatic changes [4]. Woody plants, characterized by their long life cycles and restricted dispersal capacity, are especially susceptible to these alterations [5], as their suitable habitats are closely tied to specific temperature and precipitation regimes [6].

Species distribution models (SDMs) are widely acknowledged tools for identifying priority conservation areas by integrating species occurrence data with environmental variables [7]. Among these models, MaxEnt stands out as a data-driven approach that plays a significant role in assessing habitat suitability for endangered species [8]. This model utilizes species occurrence data in conjunction with relevant environmental variables to predict geographical distribution patterns [9]. Consequently, it has been extensively employed by researchers to evaluate the impact of climate change on the potential suitable habitats of endangered species [10], including Semiliquidambar cathayensis [11], Ormosia microphylla [12], Glyptostrobus pensilis [13]. However, while projecting distribution shifts is a critical initial step, a more profound understanding is often hindered by the lack of integration with species-specific biological traits. The essential question remains how intrinsic biological constraints, such as specific regeneration niches and dispersal limitations, interact with extrinsic climatic factors to influence a species’ fate under rapid climate change.

The Ormosia species are typically trees or large shrubs found in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, primarily in Asia [14]. This group belongs to the Papilionoideae clade and is closely related to the Lupinus clade [15], comprising nearly 130 species [14]. In China, there are 35 species (http://www.iplant.cn/info/Ormosia, accessed on 1 July 2025), among which O. xylocarpa is classified as a National Class II Protected Wild Plant, recognized for its high-quality timber [16]. This species exhibits a range of biological traits—slow growth, deep root systems, prolonged seed dormancy, and limited natural regeneration capacity [17], that are hypothesized to render it particularly vulnerable to rapid climate change. Its slow life history strategy indicates a restricted ability to track shifting climate envelopes through dispersal, while its specific seed germination requirements, likely dependent on winter precipitation to break physical dormancy, may make it susceptible to altered precipitation regimes.

A predictive understanding of how intrinsic biological constraints interact with extrinsic climatic forces to determine the fate of O. xylocarpa is critically lacking. Additionally, the potential for complex, non-linear distribution trajectories, influenced by the interplay between mid-century climatic stress and late-century CO2 fertilization effects, remains unexplored for slow-growing trees. The existing and fragmented populations of O. xylocarpa in southern China face increasing threats from ongoing habitat loss, primarily driven by historical and contemporary logging for its valuable timber, as well as land conversion for agriculture and infrastructure development. Moreover, the anticipated impacts of climate change present an additional severe risk. Given its subtropical affinity, the distribution of O. xylocarpa is hypothesized to be particularly sensitive to climatic factors related to temperature seasonality and cold-quarter moisture availability, both of which are projected to undergo significant alterations under future climate scenarios. These factors may become critical limiting constraints for its survival and regeneration, highlighting the need for proactive conservation planning.

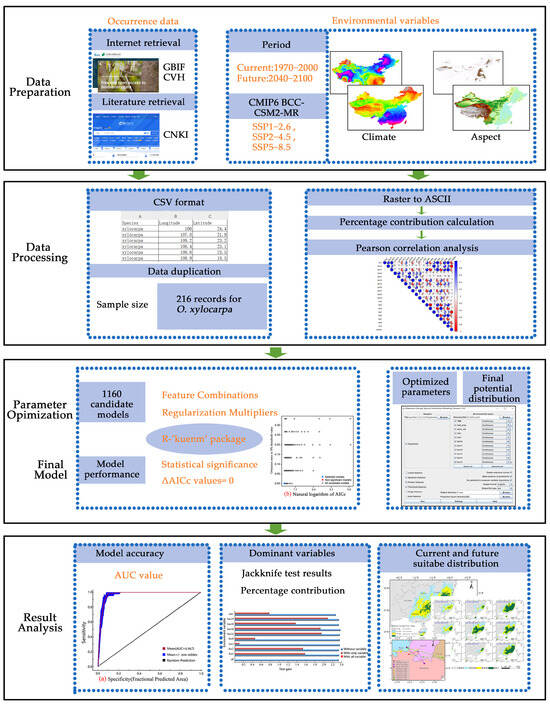

This study integrates an optimized MaxEnt model with GIS spatial analysis to quantify the spatiotemporal shifts in the suitable habitat of O. xylocarpa under multiple future climate scenarios, identify the key climatic factors limiting its distribution, and propose targeted conservation strategies to mitigate its extinction risk (Figure 1). We hypothesize that its distribution is primarily constrained by temperature seasonality and cold-quarter moisture availability, it will exhibit significant range contraction before many other species due to its limited dispersal capacity, and its suitable habitat may recover by the late-century due to the CO2 fertilization effect. The main objectives of this study are as follows:

Figure 1.

Workflow for predicting habitat suitability of O. xylocarpa under climate change scenarios.

- (1)

- To quantify the spatiotemporal shifts in the suitable habitat of O. xylocarpa under multiple future climate scenarios (SSP1–2.6, SSP2–4.5, SSP5–8.5);

- (2)

- To identify the key climatic and environmental factors limiting its distribution;

- (3)

- To propose targeted conservation strategies to mitigate extinction risks under climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Species Occurrence Data

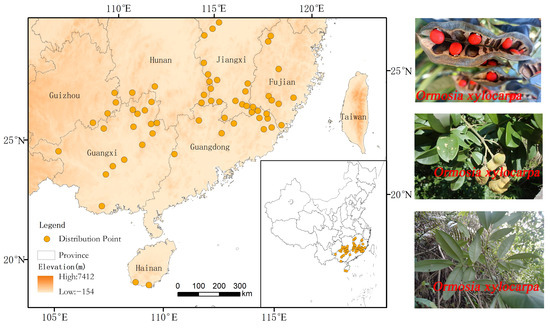

Occurrence records for O. xylocarpa were compiled from multiple sources to ensure comprehensive coverage: (1) Online databases, including the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, http://www.gbif.org/, last accessed on 15 February 2025), the National Specimen Information Infrastructure (NSII, http://www.nsii.org.cn/, last accessed on 17 February 2025), and the Chinese Virtual Herbarium (CVH, http://www.cvh.ac.cn/, last accessed on 19 February 2025). (2) A thorough literature review was conducted using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, http://www.cnki.net/, last accessed on 15 February 2025), employing “O. xylocarpa” as the keyword to obtain additional records with precise locality descriptions. For literature-derived records that lacked coordinates, a geo-referencing tool (https://jingweidu.bmcx.com/, last accessed on 19 February 2025) was utilized to obtain the corresponding coordinates. (3) To mitigate spatial sampling bias and auto-correlation, all occurrence records were spatially rarefied using the SDM toolbox in ArcGIS 10.8 [18], retaining only one point per 5 km × 5 km grid cell. This process, initiated with 216 records, resulted in 61 spatially independent occurrence points for subsequent model calibration (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Occurrence records and a photographic inset of O. xylocarpa. The orange dots represent occurrence records of O. xylocarpa.

2.2. Environmental Variables and Climate Scenarios

We obtained 19 bio-climatic variables and elevation data for the current period (1970–2000) and for three future periods (2050s: 2041–2060, 2070s: 2061–2080, 2090s: 2081–2100) from the WorldClim database (Version 2.1; http://www.worldclim.org, accessed on 20 February 2025) [19]. To represent plausible trajectories of socioeconomic development, we employed Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) [20]. Future projections were generated using the BCC-CSM2-MR global climate model, which is part of the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) [21]. We selected three SSPs to depict contrasting climate futures: SSP1-2.6 (low emissions), SSP2-4.5 (intermediate emissions), and SSP5–8.5 (high emissions) [22].

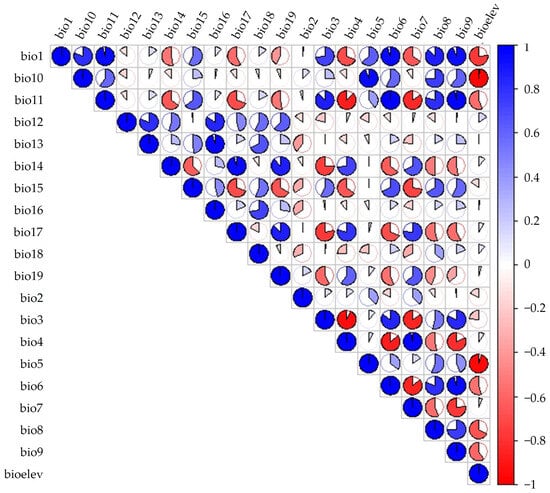

To mitigate model misinterpretation caused by multi-collinearity among variables [23], we excluded highly correlated environmental variables (|r| ≥ 0.8) through Pearson correlation analysis [24]. Initially, we imported the distribution point data along with 20 variables into MaxEnt using default settings to determine the percentage contribution [25]. Additionally, we employed ArcGIS 10.8 to extract environmental variable values at each distribution point via the “Resample” tool [26]. Subsequently, we performed Pearson correlation analysis (|r| ≥ 0.8) in SPSS 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and generated a heat map using R Software v4.5.2 (Figure 3). A pair of variables was classified as highly correlated and considered for removal if the absolute Pearson correlation coefficient (|r|) was ≥0.8 and the correlation was statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). Among the two climatic variables exhibiting |r| ≥ 0.8 [27], we selected the variable with the higher contribution rate to species distribution. For any pair of highly correlated and significant variables, we retained the variable with the greater percent contribution from a preliminary MaxEnt run for further analysis, as it was deemed to have greater biological relevance to the species’ distribution.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation heat-map among the 20 initial environmental variables.

The variable was deemed biologically insignificant if its contribution rate was low [28]. Ultimately, the results revealed that 16 environmental factors exhibited |r| ≥ 0.8 (Figure 3), which lead to the selection of nine climate variables for further analysis. These factors included Bio1 (Annual mean temperature), Bio2 (Mean diurnal range), Bio3 (Isothermality), Bio8 (Mean temperature of the wettest quarter), Bio14 (Precipitation of the driest month), Bio16 (Precipitation of the wettest quarter), Bio18 (Precipitation of the warmest quarter), Bio19 (Precipitation of the coldest quarter), and elev (elevation).

2.3. Model Optimization and Construction

To enhance model performance and prevent over-fitting [29], we optimized the MaxEnt model using the ‘kuenm’ package in R [30]. We generated a set of candidate models by evaluating 31 feature classes (FC), covering all permutations of five feature types—linear (L), quadratic (Q), product (P), hinge (H), and threshold (T)—and 40 regularization multiplier (RM) values ranging from 0.1 to 4.0 (in increments of 0.1) [25], resulting in 1160 candidate models (31 FCs × 40 RMs) [31]. Model selection was conducted based on the Akaike Information Criterion adjusted for small sample sizes (AICc). The model with a delta AICc (ΔAICc) value of 0 was determined as the optimal model from the pool of 1160 candidates for all subsequent analyses [32].

The final model was calibrated with the optimized parameters. A 75/25 random partition of the occurrence data was employed for model training and testing, respectively, and 10 bootstrap replicates were conducted to account for variability in the data partitioning [33]. The average habitat suitability across the 10 replicates served as the final output [34]. Model performance was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) [35], with values interpreted as follows: <0.7 (poor), 0.7–0.9 (moderately useful), and >0.9 (excellent) [36].

2.4. Classification and Area Calculation

Using the filtered distribution point data of O. xylocarpa in CSV format and essential environmental factors in ASCII format, the “avg.asc” file generated by the optimized MaxEnt 3.4.3 was imported into ArcGIS 10.8 for further spatial analysis. The “Extract by Mask” tool was employed to clip the predicted habitat suitability map to the geographical extent of China. Subsequently, a manual reclassification method utilizing the “Reclassify” tool divided the suitability values into four categories: unsuitable habitat (0–0.2), low-suitability habitat (0.2–0.4), medium-suitability habitat (0.4–0.6), and high-suitability habitat (0.6–1) [18], resulting in the creation of a suitability map for O. xylocarpa. To quantify the area of each suitability category, the attribute table tool in ArcGIS was used to extract the number of pixels corresponding to each reclassified category. These pixel counts were then exported to Microsoft Excel, where the total number of pixels and their proportions were calculated. Finally, by multiplying the pixel proportions by the total land area of China, the areas of each suitable habitat zone were determined.

2.5. Dynamic Analysis of Spatial Pattern

Spatial units with a species existence probability ≥ 0.4 were identified as potentially suitable areas and coded as “1” [37]. To analyze the spatial dynamics of suitable habitats for O. xylocarpa, the projected suitable areas under future climate scenarios were compared to those under contemporary climatic conditions (1970–2000) using the “Distribution changes between binary SDMs” tool in the SDM toolbox. Habitat changes were classified into three categories: expansion areas (0–1), stable areas (1–1), and contraction areas (1–0), according to binary suitability matrices [38]. Subsequently, the overall change pattern of the distribution area of O. xylocarpa was visualized using ArcGIS 10.8 software. Additionally, the centroid of the suitable habitat, representing the central location of species distribution, was calculated, and the migration trend was depicted by tracking the dynamic changes in centroid positions under different future climate scenarios [39].

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Optimization Results

The parameter optimization process determined that the optimal setting was the feature combination LQ (linear and quadratic) with a regularization multiplier of 0.1, resulting in a ΔAICc of 0. The optimized model exhibited a substantial enhancement compared to the default model, with the average training AUC of 0.967 from 10 bootstrap replicates (Table 1), signifying outstanding and dependable predictive accuracy. Each individual replicate AUC value surpassed 0.95, providing additional affirmation of the model’s resilience.

Table 1.

Parameter optimization results and evaluation metrics for the MaxEnt model.

3.2. Current Potential Distribution and Future Projections

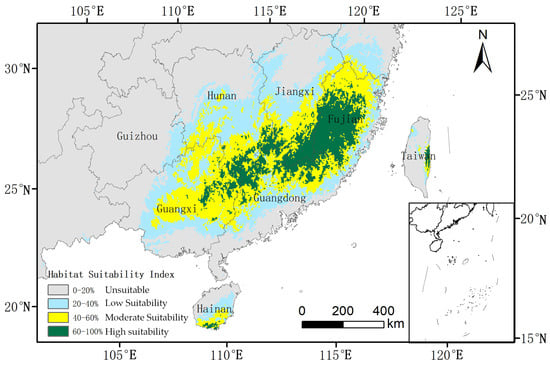

Under current climatic conditions, the total suitable habitat for O. xylocarpa, defined as areas with a probability of presence ≥ 0.2, is estimated at 63.08 × 104 km2, representing 6.58% of China’s land area (Table 2). The core suitable habitat, characterized by a suitability ≥ 0.4, encompasses 35.62 × 104 km2 and is primarily located in the subtropical regions of southern China, including Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, and the southern portions of Hunan and Jiangxi provinces (Figure 4). The spatial distribution reveals a distinct structure, with high-suitability areas forming a core in central Fujian, which is encircled by regions of medium and low suitability.

Table 2.

Projected changes in habitat suitability areas (×104 km2) for O. xylocarpa under SSP scenarios.

Figure 4.

Current potential habitat suitability distribution for O. xylocarpa in China.

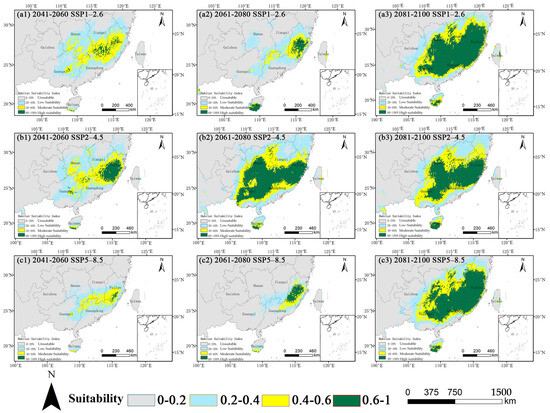

Future projections across the three climate scenarios indicated a consistent and significant non-linear trajectory (Figure 5, Table 2). An initial contraction of the total suitable area was noted by the mid-century (2050s), which was subsequently followed by a substantial expansion by the 2090s. The extent of this fluctuation differed according to the emission scenarios.

Figure 5.

Projected habitat suitability for O. xylocarpa under future climate scenarios (SSP1−2.6, SSP2−4.5, SSP5−8.5) for the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s.

A consistent pattern of initial contraction followed by expansion in the late century was evident across all scenarios, albeit with varying magnitudes (Table 2). In the SSP1–2.6 scenario, the total suitable area decreased by 44.3% by the 2070s before increasing to 94.0% above the current level by the 2090s. The most significant expansion was observed in the SSP5–8.5 scenario, where the high-suitability area, after substantial contraction in the 2050s and 2070s, surged to 40.12 × 104 km2 by the 2090s, significantly surpassing the current level. Particularly noteworthy changes were observed under SSP5–8.5.

The core suitable area experienced a severe contraction to 10.14 × 104 km2 by the 2050s (a 71.5% reduction from the current core area) but then expanded to 64.17 × 104 km2 by the 2090s, indicating an 80.2% increase from the current core area. The high-suitability habitat, nearly disappearing in the 2050s, underwent a remarkable expansion to 40.12 × 104 km2 by the 2090s. In the SSP2–4.5 scenario, a trajectory of moderate initial decline followed by gradual recovery was observed. The core area decreased in the 2050s but rebounded and expanded to 63.48 × 104 km2 and 61.29 × 104 km2 in the 2070s and 2090s, respectively. In the SSP1–2.6 scenario, the core area contracted by the 2070s before expanding to the greatest extent among all scenarios (69.09 × 104 km2) by the 2090s.

3.3. Spatial Dynamics of Suitable Habitats

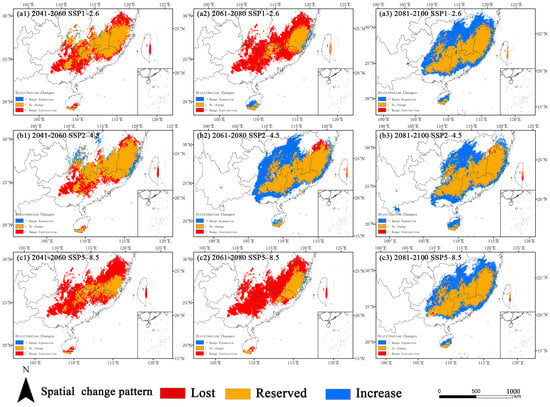

The binary projection analysis (suitable ≥ 0.4, unsuitable < 0.4) further detailed the spatial shifts (Table 3, Figure 6). A key finding across all scenarios was a substantial net expansion of suitable habitat by the 2090s, characterized by minimal habitat loss and extensive gains.

Table 3.

Spatial dynamics of suitable habitats across future periods.

Figure 6.

Spatial dynamics of suitable habitats for O. xylocarpa across future periods, showing stable, lost, and gained areas.

Under SSP1–2.6, the 2090s featured the largest expansion area (33.54 × 104 km2, a 94.16% increase), concentrated in Hunan, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang, alongside negligible habitat loss (0.19%).Under SSP5–8.5, the 2090s were characterized by a massive expansion of 28.81 × 104 km2 (80.87% increase), which predominantly formed a wide belt encircling the core historical habitats, with very low concurrent habitat loss (0.70%).In contrast, the mid-century periods (2050s and 2070s) were generally marked by substantial habitat loss and minimal gain, particularly under SSP5–8.5, which witnessed a 78.52% habitat loss rate in the 2070s.

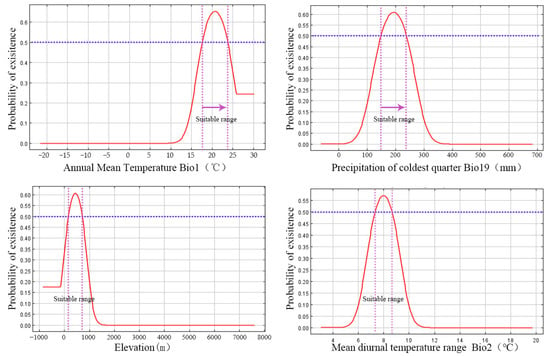

3.4. Dominant Environmental Factors and Response Curves

The distribution of O. xylocarpa was governed by four key environmental factors as identified by the MaxEnt model (Table 4). The annual mean temperature (Bio1) had the highest impact (41.1%), followed by precipitation of the coldest quarter (Bio19, 20.0%), elevation (12.1%), and mean diurnal range (Bio2, 9.6%). These factors collectively explained 82.8% of the model’s variance. Interestingly, the permutation importance, indicating a variable’s unique information, presented a different ranking: Bio2 (40.5%) was most critical, followed by elevation (30.5%), Bio19 (13.9%), and Bio1 (8.9%). This suggests that while Bio1 primarily influences the suitability pattern, the model’s predictive accuracy heavily relies on Bio2 and elevation.

Table 4.

Contribution and permutation importance of dominant environmental variables in the MaxEnt model.

The jackknife test for regularized training gain validated the critical importance of Bio19, exhibiting the highest gain in isolation. Species-specific ecological preferences were elucidated by the response curves (Figure 7, Table 4). The likelihood of presence increased with Bio19 until reaching an optimal value of around 194 mm, after which it decreased. Bio1 demonstrated peak suitability at 20.6 °C. The species displayed a preference for mid-elevations, with optimal suitability at approximately 428 m, and a narrow optimal range for Bio2, focused at 8.0 °C.

Figure 7.

Response Curves of Dominant Environmental Variables determining the distribution of O. xylocarpa. The solid red line represents the predicted probability of occurrence (habitat suitability). The blue dashed-dotted line indicates the manually set suitability threshold (≥0.5), above which is classified as a suitable area. The purple dashed-dotted lines delineate the range of environmental variable values within the suitable habitat.

3.5. Shifts in the Spatial Centroid of Suitable Habitat

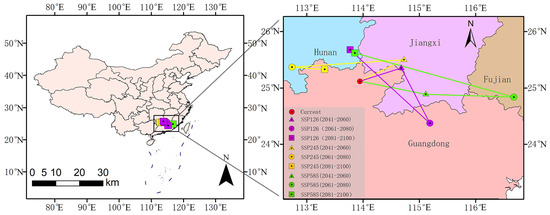

The geometric centroid of the current suitable habitat for O. xylocarpa is situated in Renhua County, Guangdong Province (113.939° E, 25.129° N). Future projections suggest a consistent directional shift toward northern and northwestern regions, including Hunan and Jiangxi, by the 2090s across all scenarios, although the specific migration paths may vary (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Shifts in the spatial centroid of suitable habitat for O. xylocarpa under future climate scenarios.

Under the SSP1–2.6 scenario, the centroid displayed a complex migration trajectory, ultimately shifting northwestward to Xinfeng County, Jiangxi (114.674° E, 25.362° N) by the 2050s. It then moved southeastward to Heping County, Guangdong (115.181° E, 24.382° N) in the 2070s, before undergoing a significant northwestward shift to Rucheng County, Hunan (113.766° E, 25.687° N) by the 2090s. The SSP2–4.5 scenario exhibited a predominant northward migration, accompanied by notable east–west oscillations. The center of gravity shifted towards the northeast to Nankang District, Jiangxi (114.720° E, 25.509° N) during the 2050s, subsequently veering west to Linwu County, Hunan (112.733° E, 25.376° N) in the 2070s, and ultimately shifting eastward to Lechang City, Guangdong (113.313° E, 25.337° N) by the 2090s. The most significant centroid displacements occurred under the SSP5–8.5 scenario, exhibiting a notable eastward movement towards Dingnan County, Jiangxi (115.110° E, 24.895° N) in the 2050s, followed by a substantial northwestward shift to Rucheng County, Hunan (113.848° E, 25.630° N) by the 2090s.

In summary, although the specific trajectories differed, the future distribution centroids consistently moved from the current core in Guangdong toward the northern and northwestern regions, specifically Hunan and Jiangxi, across all scenarios by the 2090s. This shift indicates a potential directional response of suitable habitats to climate change.

4. Discussion

The predictive accuracy of MaxEnt, similar to other correlative species distribution models (SDMs), relies on the quality of occurrence data, the selection of environmental predictors, and the model parameters. These models inherently assume an equilibrium between species distributions and the current climate, which may not adequately account for dispersal limitations or biotic interactions. Nevertheless, the high predictive accuracy of our parameter-optimized MaxEnt model (AUC = 0.967) and its close correspondence with the known distribution of the endangered species O. xylocarpa lend substantial credibility to our comprehensive, range-wide projections of habitat suitability under future climate scenarios (Figure 2 and Figure 5).

4.1. Dominant Environmental Drivers Reflect Species-Specific Adaptations and Vulnerabilities

Our findings provide robust support for the hypothesis that the distribution of O. xylocarpa is predominantly influenced by climatic factors, specifically temperature and cold-quarter moisture. The significance of annual mean temperature (Bio1) and precipitation during the coldest quarter (Bio19) corresponds with their essential roles in regulating plant physiological processes, particularly among subtropical tree species [40]. The optimal range for annual mean temperature, identified as 17.6–23.7 °C, distinctly characterizes its core subtropical niche. Notably, the species’ strong reliance on winter precipitation (Bio19) likely highlights a critical bottleneck in regeneration. For Ormosia species exhibiting physical seed dormancy, moisture from winter rains is vital for breaking dormancy and promoting germination [41]. Consequently, our model shifts the discourse from a general emphasis on precipitation importance to a more focused understanding of cold-quarter precipitation as a specific demographic filter, thereby providing a precise target for conservation management.

The mean diurnal range (Bio2) demonstrated the highest permutation importance, underscoring its distinctive informational value for the model. The optimal range of 7.3–8.7 °C indicates that O. xylocarpa is particularly sensitive to temperature stability between day and night. Asymmetric warming, characterized by a more rapid increase in nighttime temperatures, represents a significant aspect of climate change and can disrupt the carbon balance by elevating nighttime respiration at a greater rate than daytime photosynthesis [42]. This physiological stress may pose considerable challenges for slow-growing species such as O. xylocarpa, which may account for the increased significance of this variable in our model.

4.2. Mid-Century Contraction: A Consequence of Trait-Mediated Vulnerability

The extensive reduction in suitable habitat, particularly in high-suitability areas, anticipated for the 2050s across all scenarios supports our second hypothesis. Under the high-emission pathway (SSP5–8.5), this reduction exceeds 70%, suggesting that the species’ thermal and hydro–logical niches are likely to be significantly compromised within decades in its current core range. This observation is consistent with global predictions indicating that 4–8% of species will experience heightened extinction risk once warming exceeds 1.5 °C above pre–industrial levels [43], a threshold expected to be reached by mid–century [44]. The combined stress of extreme warming and altered precipitation patterns is likely to disrupt essential ecological processes, resulting in metabolic imbalance and increased water loss [45], a trend also observed in other subtropical trees, such as Shorea robusta [46]. This finding provides empirical evidence that certain biological traits—such as slow growth, limited dispersal, and a narrow regeneration niche—can render species vulnerable to early and pronounced declines under climate change, thereby serving as an early warning signal for similar taxa in subtropical forest ecosystems.

4.3. Non-Linear Trajectories and the CO2 Fertilization Effect

One plausible mechanism is the CO2 fertilization effect. Elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations can enhance water-use efficiency and photosynthesis in C3 plants, potentially mitigating the adverse effects of thermal stress and intermittent drought. The anticipated northward and northwestward shifts in the distribution centroid, along with the eventual expansion of suitable habitat by the 2090s, illustrate the dynamic response of the species’ climate envelope. Elevation, serving as a complex proxy for temperature and moisture gradients [42], played a significant role in our model. The species’ preference for mid-elevations (174–698 m) and its shift toward the more topographically complex, higher-latitude regions of Hunan and Jiangxi suggest that these areas may offer future micro–refugia. The current limitation on northward expansion beyond the Yangtze River is likely due to the interactive effects of lower annual mean temperatures (Bio1) and insufficient winter precipitation (Bio19), which fall outside the species’ optimal ecological niche. Our projected northward shift is supported by independent provenance trials, where seedlings from a northern provenance (Liping, Guizhou) outperformed those from a southern provenance (Ruyuan, Guangdong) when cultivated in a common garden situated within our projected future suitable area [47]. This suggests the existence of preadapted genotypes that may facilitate natural migration.

The most compelling evidence supporting H3 is the non-linear trajectory of habitat change, characterized by mid-century contraction followed by late-century expansion, particularly under high-emission scenarios. The significant increase in suitable habitat during the 2070s and 2090s, especially under SSP5–8.5, where the core area rebounded from approximately 10 to over 64 (×104 km2), indicates a shift in limiting factors. Under SSP2–4.5, the gradual recovery and expansion likely stem from a combination of moderate warming and the CO2 fertilization effect. The most pronounced expansion under SSP5–8.5 by the 2090s, despite the severe contraction observed mid-century, strongly suggests that elevated CO2 concentrations may fundamentally alter climatic constraints, potentially mitigating the adverse effects of extreme temperature increases on water-use efficiency. This change could enable the species to recolonize or even extend beyond its historical niche. A plausible explanation for the substantial expansion in the 2090s is indeed the CO2 fertilization effect. Increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations can enhance water-use efficiency and photosynthesis in certain woody plants, potentially counteracting the negative impacts of thermal stress and intermittent drought [42]. This may allow O. xylocarpa to reclaim or even expand into areas that become climatically marginal with respect to temperature and precipitation, thereby stabilizing or increasing overall habitat suitability by the century’s end.

The increase in global temperatures has resulted in a northward shift in the snowline and altered precipitation patterns, which are driving niche displacements toward higher latitudes and elevations [48,49]. In the case of O. xylocarpa, centroid migration corresponds with these trends. Evidence from provenance trials supports this observation: seedlings sourced from Liping, Guizhou (109°8′24.00″ E, 26°14′24.00″ N) and Ruyuan, Guangdong (113°16′48.00″ E, 24°46′12.00″ N), when cultivated under identical conditions in the Jiangxi Academy of Forestry greenhouse (115°49′ E, 28°44′ N), demonstrated significantly greater seedling height and basal diameter in Liping. This finding aligns with our projections regarding habitat shifts [47].

Low Impact Areas (LIAs), defined as regions where species habitats are expected to remain stable under future climate scenarios, are recognized as vital reservoirs for biodiversity conservation [50]. Our analysis identifies concentrated LIAs in Fujian Province, which demonstrate enhanced ecological stability and thus represent optimal sites for the cultivation of new species groups. In contrast, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan provinces are projected to experience significant reductions in habitat suitability by the 2050s. In light of these anticipated range shifts, we recommend prioritizing the establishment of new ecological corridors to functionally connect fragmented suitable habitats, thereby improving natural dispersal capacity and preserving genetic connectivity [51].

4.4. Methodological Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although our optimized MaxEnt model demonstrated robust predictive accuracy, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. Our forecasts rely on the BCC–CSM2–MR GCM and a specific set of SSPs, thereby introducing uncertainties, particularly concerning regional precipitation patterns. To address this issue, future research could utilize multi-model ensembles to assess and quantify such uncertainties. Additionally, given that MaxEnt is a correlative model, it predominantly captures climatic and topographic niches, potentially overlooking crucial non-climatic variables like soil properties, inter–specific competition, and, notably for O. xylocarpa, dispersal constraints and changes in land use. These omissions might lead to an overestimation of areas deemed potentially suitable.

To advance this research, future studies should: (1) Integrate process-based models or hybrid approaches that include species’ physiological tolerances and dispersal mechanisms to enhance the mechanistic comprehension of range shifts; (2) Explicitly model forthcoming land use alterations to evaluate the combined challenges of climate change and habitat fragmentation; (3) Employ genomic tools to detect adaptive genetic variations and evaluate the evolutionary capacity of distinct populations, thus improving assisted migration strategies.

Our spatially explicit projections facilitate the transition from theoretical modeling to practical conservation planning. The stable, high-suitability regions identified in Fujian Province may serve as long-term climate refugia and should be prioritized for in situ conservation, the establishment of germplasm banks, and the enhancement of existing protected areas. In contrast, areas anticipated to experience significant habitat loss by mid-century, such as portions of Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan, necessitate immediate actions to mitigate non-climatic threats and to buffer populations against the forthcoming bottleneck.

To facilitate the tracking of its shifting climate envelope, we recommend the proactive planning of ecological corridors that connect current populations with future suitable areas in Hunan and Jiangxi [51]. For populations confined to deteriorating habitats, assisted migration to pre-identified future suitable areas should be considered. Given the species’ biological constraints, such as slow growth and seed dormancy, conservation efforts must incorporate species-specific management. The application of established techniques to break seed dormancy, including controlled hydrothermal pre-treatment [52], is essential for enhancing germination rates to support large-scale propagation and reforestation. Ultimately, integrating genomic insights to select climate-resilient provenances will be crucial for ensuring the long-term adaptive capacity and persistence of O. xylocarpa in a changing climate.

5. Conclusions

The conservation of O. xylocarpa is vital for maintaining ecosystem health and biodiversity, particularly in southern China’s fragile subtropical forests [53]. This study utilized an optimized MaxEnt model to quantitatively evaluate and forecast the potential geographical distribution of the endangered tree species O. xylocarpa under both current and future climate scenarios. The principal conclusions are as follows: First, this research identified the key environmental factors influencing the distribution of O. xylocarpa and quantitatively delineated its fundamental ecological niche. The annual mean temperature (Bio1) and precipitation during the coldest quarter (Bio19) emerged as the primary climatic constraints, with optimal ranges of 17.6–23.7 °C and 149–239 mm, respectively. This finding offers essential criteria for selecting suitable sites for ex situ conservation and reforestation efforts. Second, model projections indicated a complex, non-linear trajectory of habitat change.

A substantial reduction in suitable habitat is anticipated by the mid-21st century, with the primary suitable area projected to experience a loss exceeding 70% under the high-emission scenario (SSP5-8.5). Nevertheless, a notable expansion is forecasted by the 2090s, potentially mitigated by the CO2 fertilization effect. This pattern of “contraction-then-expansion” emphasizes a significant risk of extinction during the mid-century bottleneck while also suggesting the possibility of long-term recovery, underscoring the need for a two-phased conservation approach. Geographically, the core of the suitable habitat is consistently predicted to shift northwestward from its current epicenter in Guangdong, ultimately concentrating in topographically intricate regions of Hunan and Jiangxi. This trend of migration is supported by provenance trials, highlighting the crucial role of these areas as future climate refugia. Based on these results, we advocate for a proactive and adaptable conservation framework: (1) Enhance on-site protection of identified stable climate refugia within Fujian Province; (2) Strategically plan ecological corridors to link current populations with forthcoming suitable areas in the northwest, facilitating natural migration; and (3) For populations confined in deteriorating habitats, implement assisted migration along with species-specific management practices (e.g., seed pre-treatment) to surmount biological obstacles, ensuring the enduring survival of O. xylocarpa in the face of climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, W.L.; writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nolan, C.; Overpeck, J.T.; Allen, J.R.M.; Anderson, P.M.; Betancourt, J.L.; Binney, H.A.; Brewer, S.; Bush, M.B.; Chase, B.M.; Cheddadi, R.; et al. Past and future global transformation of terrestrial ecosystems under climate change. Science 2018, 361, 920–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.F.; Liu, W.A.; Ai, J.W.; Cai, S.J.; Dong, J.W. Predicting mangrove distributions in the Beibu Gulf, Guangxi, China, using the MaxEnt model: Determining tree species selection. Forests 2023, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayani-Parás, F.; Botello, F.; Castañeda, S.; Munguía-Carrara, M.; Sánchez-Cordero, V. Cumulative habitat loss increases conservation threats on endemic species of terrestrial vertebrates in Mexico. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 253, 108864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Freiría, F.; Velo-Antón, G.; Brito, J.C. Trapped by climate: Interglacial refuge and recent population expansion in the endemic Iberian adder Vipera seoanei. Divers. Distrib. 2015, 21, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.P.; Liu, Y.F.; Ou, J. Meta-analysis of the impact of future climate change on the area of woody plant habitats in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1139739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.A.; Cabeza, M.; Rahbek, C.; Araújo, M.B. Multiple Dimensions of Climate Change and Their Implications for Biodiversity. Science 2014, 344, 1247579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannuzel, G.; Balmot, J.; Dubos, N.; Thibault, M.; Fogliani, B. High-resolution topographic variables accurately predict the distribution of rare plant species for conservation area selection in a narrow-endemism hotspot in New Caledonia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2021, 30, 963–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, X.D.; Zhou, H.T.; Zang, S.Y.; Wu, C.S.; Li, W.L.; Li, M. Maximum entropy modeling for habitat suitability assessment of red-crowned crane. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Xu, D.P.; Liao, W.K.; Xu, Y.; Zhuo, Z.H. Predicting the current and future distributions of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) based on the MaxEnt species distribution model. Insects 2023, 14, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.X.; Jiang, Z.H.; Li, W.; Hou, Q.Y.; Li, L. Changes in extreme temperature over China when global warming stabilized at 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Z.; Zhao, G.H.; Zhang, M.Z.; Cui, X.Y.; Fan, H.H.; Liu, B. Distribution pattern of endangered plant Semiliquidambar cathayensis (Hamamelidaceae) in response to climate change after the last interglacial period. Forests 2020, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Weng, H.; Ye, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhan, C.; Ahmad, S.; Xu, Q.; Ding, H.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, G.; et al. Simulation of potential geographical distribution and migration pattern with climate change of Ormosia microphylla Merr. & H. Y. Chen. Forests 2024, 15, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Z.; Zhang, M.Z.; Yang, Q.Y.; Ye, L.Q.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhang, G.F.; Chen, S.P.; Lai, W.F.; Wen, G.W.; Zheng, S.Q.; et al. Prediction of suitable distribution of a critically endangered plant Glyptostrobus pensilis. Forests 2022, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azani, N.; Babineau, M.; Bailey, C.D.; Banks, H.; Barbosa, A.R.; Pinto, R.B.; Boatwright, J.S.; Borges, L.M.; Brown, G.K.; Bruneau, A.; et al. A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny. Taxon 2017, 66, 44–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.S.; Su, Z.H.; Yu, S.Q.; Liu, J.L.; Yin, X.J.; Zhang, G.W.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Genome comparison reveals mutation hotspots in the chloroplast genome and phylogenetic relationships of Ormosia species. Biomed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7265030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.H. The complete chloroplast genome of Ormosia nuda (fabaceae), an endemic species in China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B-Resour. 2021, 6, 2095–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.J.; Quan, Y.X.; Chen, Y.A.; Wang, Q.; Zou, X.X.; Chen, F.Y.; Ni, L. A new lignan from leaves of Ormosia xylocarpa. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2023, 17, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.L.; Yao, L.J.; Meng, J.S.; Tao, J. Maxent modeling for predicting the potential geographical distribution of two peony species under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, X.; Tan, Z.; Yao, L.; Hong, Z.; Cai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, H. Geographical distribution and predict potential distribution of Cerasus serrulata. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43369–43376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wang, T.; Groen, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Yang, X.; Ma, K.; Wu, Z. Climate and land use changes will degrade the distribution of Rhododendrons in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.H.; Nix, H.A.; Busby, J.R.; Hutchinson, M.F. BIOCLIM: The first species distribution modelling package, its early applications and relevance to most current MaxEnt studies. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.L.; Ma, J.M.; Chen, G.S. Potential geographical distribution and its multi-factor analysis of Pinus massoniana in China based on the maxent model. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, N. What does ecological modelling model? A proposed classification of ecological niche models based on their underlying methods. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechergui, K.; Hayat, U.; Ahmad, M.H.; Alamri, S.M.; Alamery, E.R.; Faqeih, K.Y.; Aldubehi, M.A.; Jaouadi, W. Forecasting the Impact of Climate Change on Tetraclinis articulata Distribution in the Mediterranean Using MaxEnt and GIS-Based Analysis. Forests 2025, 16, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, K.L.; Tao, J. MaxEnt modeling and the impact of climate change on Pistacia chinensis bunge habitat suitability variations in China. Forests 2023, 14, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Park, D.S.; Liang, Y.; Pandey, R.; Papes, M. Collinearity in ecological niche modeling: Confusions and challenges. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 10365–10376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Tang, L.; He, H.; Yang, F.X.; Tao, J.; Wang, W.C. Assessing the impact of climate change on the distribution of Osmanthus fragrans using Maxent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 34655–34663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazco, S.J.E.; Ribeiro, B.R.; Laureto, L.M.O.; De Marco, P. Overprediction of species distribution models in conservation planning: A still neglected issue with strong effects. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 252, 108822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Bonello, P.; Liu, D.S. Mapping the environmental risk of beech leaf disease in the northeastern United States. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 3575–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos, M.E.; Peterson, A.T.; Barve, N.; Osorio-Olvera, L. kuenm: An R package for detailed development of ecological niche models using Maxent. Peerj 2019, 7, e6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.S.; Xia, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.Y.; Ding, X.Y.; Zhang, B.; Deng, G.X.; Yang, D.D. Predicting the spatial distribution of the mangshan pit viper (Protobothrops mangshanensis) under climate change scenarios using MaxEnt modeling. Forests 2024, 15, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkala, E.M.; Mutinda, E.S.; Wanga, V.O.; Oulo, M.A.; Oluoch, W.A.; Nzei, J.; Waswa, E.N.; Odago, W.; Nanjala, C.; Mwachala, G.; et al. Modeling impacts of climate change on the potential distribution of three endemic Aloe species critically endangered in East Africa. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 71, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.J.; Sun, S.X.; Wang, N.X.; Fan, P.X.; You, C.; Wang, R.Q.; Zheng, P.M.; Wang, H. Dynamics of the distribution of invasive alien plants (Asteraceae) in China under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Wang, T.X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.J. Prediction of historical, current, and future configuration of tibetan medicinal herb Gymnadenia orchidis based on the optimized MaxEnt in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Plants 2024, 13, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Zhao, R.X.; Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhao, G.H.; Zhang, F.G. Prediction of potential distribution areas and priority protected areas of Agastache rugosa based on Maxent model and Marxan model. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1200796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elith, J.; Kearney, M.; Phillips, S. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.H.; Cui, X.Y.; Sun, J.J.; Li, T.T.; Wang, Q.; Ye, X.Z.; Fan, B.G. Analysis of the distribution pattern of Chinese Ziziphus jujuba under climate change based on optimized biomod2 and MaxEnt models. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Li, M.Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.Z. Optimized maxent model predictions of climate change impacts on the suitable distribution of Cunninghamia lanceolata in China. Forests 2020, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Chen, Y.W.; Wei, X.L. Hard seed characteristics and seed vigor of Ormosia hosiei. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, B.; Zhu, W.W.; Wei, S.M.; Li, B.B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, N.; Lu, J.J.; Chen, Q.S.; He, C.Y. Parallel selection of loss-of-function alleles of Pdh1 orthologous genes in warm-season legumes for pod indehiscence and plasticity is related to precipitation. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, A.; Arif, M.; Zarif, N.; Gul, Z.; Xiangyue, L.; Yukun, C. Effects of riparian buffer and stream channel widths on ecological indicators in the upper and lower Indus River basins in Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1113482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.D.; Wynes, S. Current global efforts are insufficient to limit warming to 1.5 °C. Science 2022, 376, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycoo, M.A. Beyond 1.5 °C: Vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies for Caribbean amall island developing states. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.Y.; Yu, H.Y.; Kong, D.S.; Yan, F.; Liu, D.H.; Zhang, Y.J. Effects of gradual soil drought stress on the growth, biomass partitioning, and chlorophyll fluorescence of Prunus mongolica seedlings. Turk. J. Biol. 2015, 39, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishir, S.; Mollah, T.H.; Tsuyuzaki, S.; Wada, N. Predicting the probable impact of climate change on the distribution of threatened Shorea robusta forest in Purbachal, Bangladesh. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.Q.; Deng, H.Y.; Mo, X.Y.; Liu, L.T. Growth rhythms of three Ormosia species seedlings of different provenances. Rev. Arvore 2019, 43, e430606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.H.; Song, G.X.; Hu, Y.M. Rapid determination of volatile compounds emitted from Chimonanthus praecox flowers by HS-SPME-GC-MS. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. C-A J. Biosci. 2004, 59, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Jacquemyn, H.; Burgess, K.S.; Zhang, L.G.; Zhou, Y.D.; Yang, B.Y.; Tan, S.L. Contrasting range changes of terrestrial orchids under future climate change in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 165128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Mi, Z.Y.; Lu, C.; Zhang, X.F.; Chen, L.J.; Wang, S.Q.; Niu, J.F.; Wang, Z.Z. Predicting potential distribution of Ziziphus spinosa (Bunge) HH Hu ex FH Chen in China under climate change scenarios. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgiarini, C.; Meimberg, H.; Curto, M.; Stiehl-Alves, E.M.; Vijayan, T.; Engl, P.T.; Bräuchler, C.; Kollmann, J.; de Souza-Chies, T.T. Low genetic differentiation despite high habitat fragmentation in an endemic and endangered species of Iridaceae from south America: Implications for conservation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 207, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, Y.; Pérez, L.; Escalante, D.; Pérez, A.; Martínez-Montero, M.E.; Fontes, D.; Ahmed, L.Q.; Sershen; Lorenzo, J.C. Heteromorphic seed germination and seedling emergence in the legume Teramnus labialis (L.f.) spreng (fabacaeae). Botany 2020, 98, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Sun, Y.R.; Huang, H.H.; Gong, Z.W.; Zhu, Y.F. Distribution changes of Ormosia microphylla under different climatic scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).