Abstract

The effects of silver nanoparticles and arsenic at community levels have rarely been assessed in laboratory experiments, despite their obvious advantage in reflecting better the natural conditions compared to traditionally single species-focused toxicological experiments. In the current study, the multifaceted effects of these xenobiotics, acting alone or combined, on meiobenthic nematodes were tested in a laboratory experiment carried out in microcosms. The nematofauna was exposed to two concentrations (0.1 and 1 mg·L−1) of silver nanoparticles (Ag1/Ag2) and arsenic (As1/As2), as well as to a mixture of both compounds, for 30 days. The results particularly highlighted a significant decrease in the abundance and taxonomic diversity of nematodes directly with increasing dosages of these compounds when added alone at the highest concentration. The addition of these levels of xenobiotics seems to make the sediment matrix gluey, hence inducing greater mortality among microvores and diatoms feeders. Moreover, the nematofauna went through a strong restructuring phase following the exposure to both compounds when added alone, leading to the disappearance of sensitive taxa and their replacement with more tolerant ones. However, the similarity in nematofauna composition between control and mixtures of silver nanoparticles and arsenic (except for Ag1As2) suggests that the toxicity of the latter pollutant could be attenuated by its physical bonding to the former.

1. Introduction

Population outgrowth and rapid urbanization by an uninterrupted industrial evolution and progression of different technologies in all aspects of life around the world have negatively impacted many environmental issues [1]. Therefore, the atmosphere, water, soil, and also sediments have become good receivers of classical and emerging pollutants causing an inevitable deterioration in their quality [2].

Silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) are gaining popularity as antibiotic agents in textiles and wound dressings, medical devices, and appliances such as refrigerators and washing machines [3]. They have traditionally been defined as particles with an overall size of less than 100 nanometers, but the term “nanosilver” is also increasingly used, especially in commercial products containing nanomaterials with high proportions of silver. Many Ag NP-containing products are most commonly used as antimicrobial coatings to prevent infection or as deodorants. However, adequate assessment of the long-term effects of Ag NP exposure and its release into the environment has lagged behind the rapid increase in the commercialization of Ag NP products [4].

Arsenic is a crystalline semimetal with properties of both metal and non-metal elements and widely exists in the natural environment. It is the 20th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust and the 14th most abundant element in seawater [5,6]. Arsenic contamination from natural sources such as volcanic eruptions and human activities such as the manufacture of alloys, glass, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals can also lead to the accumulation of arsenic in the environment [7].

Arsenic from natural and anthropogenic sources enters the atmosphere, groundwater, and rivers and eventually the oceans. Arsenic concentrations in seawater are typically below 1.5 µg·L−1 [8]. However, high concentrations ranging from 0.5–5000 µg·L−1 have been reported in drinking water under contaminated conditions in some areas [5]. Arsenic concentrations of 1100 µg·L−1 were reported downstream of an industrial arsenic production site in South Carolina, USA [9].

It is evident that high amounts of both arsenic and silver NPs will be deposited finally into the sea and returned back to the human body through the consumption of contaminated seafood.

The first step for preventing health risks and establishing strict thresholds is knowledge of small bioindicators at the base of the marine food chain as is the case for meiobenthos and especially the dominant group of nematodes. Many studies highlighted the usefulness of these worms in laboratory bioassays based on their short generation times (days to months), small average size range (~1–5 mm), highest abundance (up to 23 million per m2), and easy maintenance in controlled experimental conditions [10,11,12]. Currently, about 20,000 nematode species, of which 6500 are marine meiobenthic, have been formally described [13]

The importance of meiobenthic organisms also comes from the fact that macrobenthic seafood (fish, shrimps, crabs, etc.) feeds on them mostly at larval stages [14]. Consequently, the meiobenthos may be considered as the transmitters of pollution to the higher trophic levels and thus to human beings. Many published studies reported significant effects of stressors mostly by lowering meiobenthic abundance and diversity [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] but to date none has tested that for the NPs, and in particular silver ones. Similarly, no works have been devoted to the effects of arsenic on meiofaunal organisms. Moreover, no one has investigated possible interactions of both xenobiotics even though pollution is usually in the form of a stressful cocktail.

The current work aims to fill the above gaps by answering the following questions: (i) Are arsenic and silver NPs toxic for meiobenthic nematodes? (ii) Do they make each other more ecotoxic? (iii) Or, is their bioavailability reduced once they are mixed? In fact, if the latter assumption is correct, that will encourage their use for remediation purposes to purify subtidal marine areas. It is to be expected that arsenic and silver NPs will have a significant negative impact on meiobenthic nematodes. It is unknown if the effects of arsenic and silver NPs would be additive, synergetic, or antagonistic since there are no known or standard interactions between them.

2. Materials and Methods

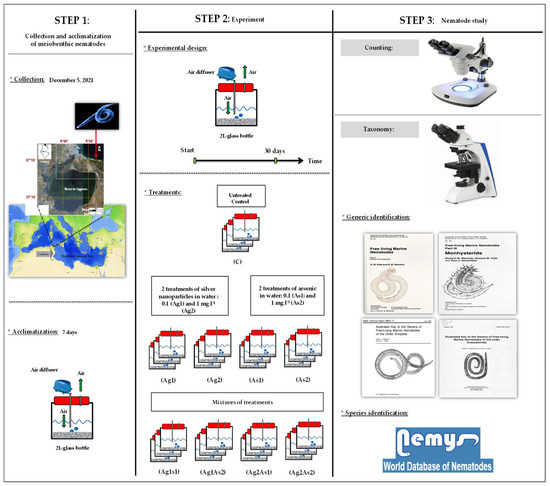

A graphical representation that shows the timeline, the design of the experiment, and the analyses performed is given in Figure 1. Details of all schematic steps are presented thereafter.

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of steps and methodology adopted to experimentally study effects of silver nanoparticles and arsenic on meiobenthic nematodes.

2.1. Collection Site and Laboratory Processing

The sediments were collected early in the morning (7 a.m.) on 27 November 2022, at a coastal site (37°15′07.34″ N, 9°56′26.75″ E) located at the upper infralittoral domain in Bizerte Bay, Tunisia. Samples were taken from the upper 5 cm of the sediment layer at 50 cm of the water column with the aid of Plexiglass hand cores (inner diameter of 3.6 cm, section of 10 cm2). The collection site was chosen intentionally as studies of [22,23,24] documented its pristine quality of both sediment and water in addition to the high diversity of its meiofauna. Four variables were measured at the sediment–water interface during sampling. The water depth was measured with a pendulum, then salinity and temperature were determined using a Model WTW LF 196 thermo-salinometer (Weilheim, Germany). Dissolved oxygen concentrations were measured with a WTW Oxi 330/SET, WTW, Weilheim (Germany) model oximeter.

In the laboratory, aliquots of sediment were sieved through a 63 μm sieve under a jet of water and then dried at 45 °C to quantify the sedimentary fraction larger than 63 μm [25]. The cumulative curves were then plotted to determine the mean grain size of the coarse fraction [25]. Additional aliquots of equal volume were used to evaluate the total organic matter by the mass loss method (450 °C, 6 h) [26] and water content after drying the sediment at 45 °C until a constant weight [27].

2.2. Contamination with Arsenic and Silver NPs

The contamination of water was performed appropriately with standard inorganic trivalent As (As (III)) and/or silver NPs.

- Stock solution was prepared from As (III), to which filtered seawater (0.7 µm pore-size Glass Microfibre GF/F, Whatman, Schnelldorf, Germany) from the collection site in Bizerte Bay (Tunisia) was added to obtain a final concentration of 100 mg·L−1. Aliquots of this solution were diluted and then added to microcosms according to the two intended concentrations: 0.1 (hereafter As1) and 1 mg·L−1 (hereafter As2).

- Ag NPs (described by the vendor as having a size < 100 nm; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) were homogeneously dispersed in deionized water by sonication (Branson-5210 sonicator; Branson, MO, USA) for 13 h at maximum power, stirring for 7 days, then filtered through a cellulose membrane (pore size 100 nm, Advantec; Toyo Toshi Kaisha, Tokyo, Japan) to remove NP aggregates. These Ag NPs were previously characterized microscopically by [28]. The same two nominal concentrations tested for As were considered once again: 0.1 (hereafter Ag1) and 1 mg·L−1 (hereafter Ag2).

To sum up, eight treatments were prepared with two for each xenobiotic paralleled with their respective mixtures: silver NPs (Ag1 and Ag2) and arsenic (As1 and As2) and their mixtures (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2). The control nematodes were topped up with filtered seawater without adding sodium arsenite or Ag NPs, thus keeping all conditions unchanged. All contaminated water with As and Ag NPs was replaced daily in each microcosm to avoid the regression of ambient water concentration. The meiobenthic nematodes were not fed during the entire experimental period.

USEPA [29] reported that the maximum acute toxicity value of arsenic (III) to 12 species of marine organisms was 16.03 mg·L−1. In this work, an environmental concern level (ECL) equal to 100 was adopted for As (III) as proposed by [30] in the case of marine waters to define our lowest concentration of 0.1 mg·L−1.

Moreover, the effects of As III (0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 1 mg·L−1) and Ag NPs (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 2 mg·L−1) were previously tested on the freshwater clam Corbicula fluminea by [31,32] for 14 and 28 days, respectively. Both studies showed that C. fluminea responded biochemically starting from 0.1 mg·L−1 and a high oxidative stress status was noticeable after exposure to 2 mg As·L−1 [32]. Herein, we preferred choosing 1 mg·L−1 as our maximum because clams are much bigger than meiobenthic nematodes and taxonomically more evolved; this allowed us to avoid intensive and quick nematode mortality.

The assay was static and carried out in an experimental room over 30 days, in triplicate for each treatment, using filtered seawater, with controlled conditions (light/dark photoperiod cycle of 8.5/15.5 h and corresponding temperatures of 18 °C/12 °C) and continuous aeration with air pumped directly from a diffuser. These laboratory conditions were deduced from hourly meteorological data (http://www.infoclimat.fr, accessed on 26 November 2022) for the city of Bizerte, Tunisia, during the month before starting the current bioassay.

2.3. Nematode Study

To extract meiobenthic organisms from the sediment, the steps of levigation–decantation–sieving were necessary through two stacked sieves (1 mm and 40 μm) [33]. These sieves were used to separate macrofauna and meiofauna, respectively. Only the fraction retained on the 40 μm mesh size was preserved in 4% neutral formalin and drops of Rose Bengal (0.2 g·L−1) were added to better distinguish meiobenthic animals selectively colored in pink from the inert matter during sorting [34]. Afterward, the meiobenthic nematodes were sorted with the aid of a 50× stereomicroscope (Wild-M3B type) after being poured into a tiled Dollfus chamber. For controls and treatments with arsenic and silver NPs, one hundred nematodes were picked and mounted on microscope slides as described by [35].

All picked worms were identified to genus level by using a Nikon DS-Fi2 camera coupled with a Nikon microscope (Image Software NIS Elements Analysis Version 4.0 Nikon 4.00.07–build 787–64 bit) and based on the generic keys of [15,36,37]. Morphological descriptions of the species were downloaded from the NeMys database which is constantly updated by the nematologists at Ghent University, Belgium [38]. Four community-based qualitative tools were considered, namely the species number (S), Margalef’s species richness (d), Shannon–Wiener’s index (H′), and Pielou’s evenness (J′).

Two functional traits were distinguished for each nematode genus: feeding type and tail shape. Four trophic groups were separated as suggested by [39]: the selective deposit feeders (1A) that are mainly microcores, non-selective deposit feeders (1B) that are consumers of detritus, epistratum feeders (2A) that are consumers of diatoms, and omnivores and carnivores (2B) that are consumers of small meiobenthic animals. Also, four tail shapes were discriminated as reported in [40]: conical (co), clavate/conico-cylindrical (cla), elongated/filiform (e/f), and short/rounded (s/r).

2.4. Statistical Processing

Data were tested for normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) and equality of variance (Bartlett test) to fulfill the requirements of parametric analyses, and log-transformations were practiced when these assumptions were not met. Five univariate tools were considered in multiple comparisons: abundance, species number (S), Margalef’s species richness (d), Shannon–Wiener index (H′), and Pielou’s evenness (J′). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test were performed with the software STATISTICA v.8 in order to test for the significant global and multiple comparisons, respectively.

Several multivariate analyses were also carried out using the Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research (PRIMER v.5) software package (see [41,42]). First, based on single linkage Bray–Curtis similarity values obtained from square-root transformed nematode frequencies, a similarity matrix was constructed. Then, a hierarchical cluster analysis (hereafter CA) and a non-metric multidimensional scaling (hereafter nMDS) ordination were applied. The distance-based permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted to investigate the influence of nine different treatments on total nematofaunal abundance. PERMANOVA analysis of total nematode community data showed a significant interaction between “treatments” (p < 0.05). Pair-wise tests were carried out to verify the significance of the differences among treatments if any were observed in the main test. It was followed by similarity percentage (SIMPER) analysis to determine the contribution of each species or functional group to the average dissimilarity [41].

3. Results

3.1. Abiotic Features of the Collection Site

On the day of sampling, the sediments were collected at a depth of 0.5 m. In situ, dissolved oxygen was 12.35 mg·L−1 and the temperature and salinity were 14.9 °C and 37.6 PSU, respectively. The data obtained from sediments showed that they were divided into 98.772 ± 0.061% coarse particles (˃63 µm) with a mean grain size of 0.39 ± 0.05%. The sediment contents of total organic matter and water were equal to 0.83 ± 0.04% and 29.47 ± 3.01%, respectively.

3.2. Nematode Abundances

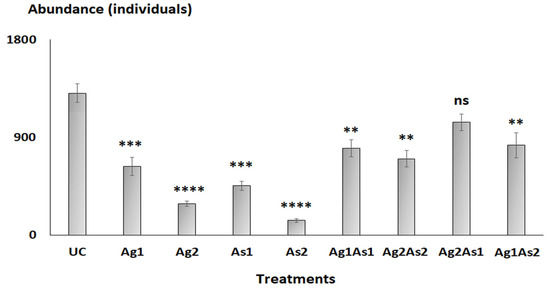

The overall abundance of nematodes decreased significantly (Tukey HSD test: p-values < 0.01) following exposure to silver NPs and/or arsenic, except for the mixture Ag2As1 (p-value = 0.0725) compared to the control (Figure 2). The total abundance of nematodes also decreased significantly in mesocosms treated with the highest concentrations of silver NPs or arsenic (i.e., Ag2 and As2) compared to Ag1 and As1 (Figure 2). Overall, the total abundance of nematodes in mixtures was significantly higher compared to silver NPs and arsenic treatments alone (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Abundances of meiobenthic nematodes from the untreated control microcosms (UC) and those enriched with silver nanoparticles (Ag1 and Ag2), arsenic (As1 and As2), and their mixture (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2). Significant differences in comparison to controls using Tukey’s HSD test: p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and p < 0.0001 (****), log(x)-transformed data. Not significant, ns.

3.3. Taxonomic Census and Community Composition of Nematodes

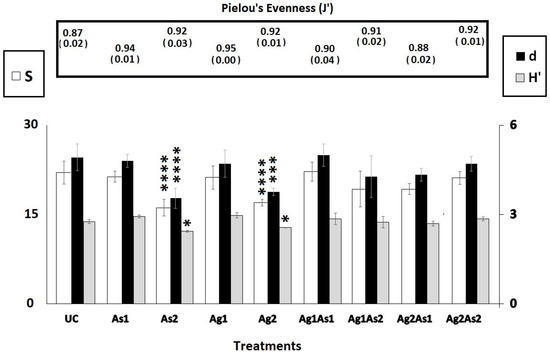

At the end of the bioassay, the nematofauna from control mesocosms comprised 7 orders and 18 families, 23 genera, and 26 species (Table 1 and Table 2). The most diverse families were Xyalidae (S = 6), Cyatholaimidae (S = 3), Oncholaimidae (S = 2), and Comesomatidae (S = 2). The remaining fourteen families were represented by just one species (Table 1). Four treatments, namely UC, Ag1, As1, and Ag2As2, were populated each by twenty-six species. In the control assemblage, two taxa were dominant (≤10%): Halaphanolaimus sp. (18 ± 3.6%) and Calomicrolaimus honestus (14.66 ± 4.16%). As far as the five remaining treatments are concerned, the disappearance of several species was observed as follows: As2 (seven species), Ag2 (seven species), Ag1As1 (one species), Ag2As1 (one species), and Ag1As2 (one species). The diversity indices S, d, and H′ were similar among treatments and control, except for Ag2 and As2, where they were significantly lower (Tukey HSD test: p-values < 0.0001, Figure 3). Pielou’s evenness was similar across all treatments (1-ANOVA: p-values = 0.805, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Alphabetical listing of nematode taxa from microcosms spiked or not with silver nanoparticles and/or arsenic and their taxonomic nomenclature and classification, feeding types (FG), and tail shapes (TS).

Table 2.

Relative abundances (SD) of the free-living nematode species identified in the control treatment (UC) and those enriched with silver nanoparticles (Ag1 and Ag2) and arsenic (As1 and As2) and their mixture (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2). Bold values represent proportions of functionally dominant species (≥10%). Black and gray cells indicate the species with decreased and increased abundances, respectively (SIMPER outcomes).

Figure 3.

Graphical summary of univariate taxonomic indices of the control microcosms (UC) and those enriched with silver nanoparticles (Ag1 and Ag2), arsenic (As1 and As2), and their mixtures (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2). S = species number, d = Margalef’s species richness, H′ = Shannon–Wiener index, J′ = Pielou’s evenness. The stars indicate significant differences compared to the controls (UC) (* = p <0.05; *** = p <0.0001; **** = p < 0.00001) (Tukey’s HSD test, log-transformed data).

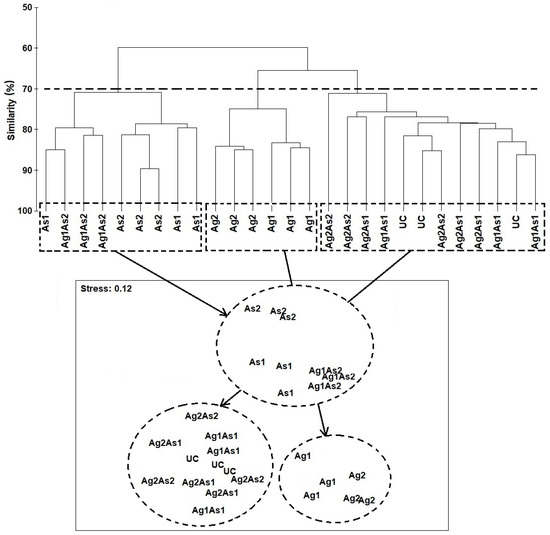

The hierarchical cluster analysis and the nMDS orientation based on the Bray–Curtis similarity matrix revealed at the cut-off of 70% practically the same two-dimensional pattern of the nematode assemblages, based on their taxonomic affinity (Figure 4). Thus, the nematofauna from the assemblages exposed to As1, Ag1As2, and As2 were distinctly separated at the top of the ordination space, far from the cluster from the right side, which comprised the species treated with silver NPs (i.e., Ag1 and Ag2) and the assemblages UC, Ag1As1, Ag2As1, and Ag2As2, which were located at the bottom of the ordination space.

Figure 4.

(Above): Hierarchical cluster analysis (single linkage Bray–Curtis similarity values) of nematode assemblages on the basis of square-root transformed abundances of species from nematofauna of the control nematode assemblage (UC) and those enriched with silver nanoparticles (Ag1 and Ag2), arsenic (As1 and As2), and their mixtures (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2) where groups are separated by fixing the cut-off at 70% of Bray–Curtis similarity, as shown by the dotted horizontal line. (Below): non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) 2D plot based on Bray–Curtis similarity.

The PERMANOVA results showed a significant effect of the factor “treatment” on the nematode community composition (Table 3) and the pair-wise tests detected significant differences between controls and As2, Ag2, Ag1As2, and As1, respectively.

Table 3.

Results of PERMANOVA and pair-wise tests for differences in nematode taxonomic composition between the control nematode assemblage (UC) and those enriched with silver nanoparticles (Ag1 and Ag2), arsenic (As1 and As2), and their mixtures (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2). Significant difference at p less than 0.05.

The spatial distribution of communities in treatments in the nMDS 2D plot was closely supported by the dissimilarity values (Table 4), following the ranking: Ag2As1 < Ag1As1 < Ag2As2 < Ag1 < As1 < Ag1As2 < Ag2 < As2. SIMPER results (Table 4) supported the overall nMDS outcomes, by specifying the contributions of taxa to ~50% of the dissimilarities between assemblages exposed to As and Ag NPs and the untreated control one.

Table 4.

Similarity percentage (SIMPER) procedures based on taxonomic composition between the control nematode assemblage (UC) and those enriched with silver nanoparticles (Ag1 and Ag2), arsenic (As1 and As2), and their mixtures (Ag1As1, Ag2As2, Ag2As1, and Ag1As2). The values in parentheses indicate the relative contributions of nematode species participating in about 50% of the average dissimilarity between the reference nematofauna and those exposed to the different treatments. Average dissimilarity (AD); more abundant (+); less abundant (−); steady relative abundance (st); elimination (ø).

- Comparing the species’ relative frequency among treatments, several trends were observed. First, with respect to Ag1 and Ag2 versus control, the relative abundance of the nematodes changed. The relative abundances of the species C. honestus and Halaphanolaimus sp., decreased, whereas those of M. pristiurus and D. trabeculosum increased (Table 4). The species L. longicaudatus disappeared in Ag2, whereas the frequency of O. calvadocicus increased compared to Ag1 and control.

- In As1 and As2, the relative abundances of C. honestus, Halaphanolaimus sp., and C. germanicum decreased compared to the control (Table 4); the latter species disappeared in As2. In contrast, the abundance of the species M. pristiurus, D. trabeculosum, and E. longicaudatus increased in both arsenic treatments compared to controls. Similar taxonomic changes in nematofauna were also observed after exposure to Ag1As2, namely C. honestus ↓, Halaphanolaimus sp. ↓, M. pristiurus ↑, and D. trabeculosum ↑ (Table 4).

- In Ag2As1 the relative abundances of M. pristiurus and E. longicaudatus were higher compared to control. SIMPER analyses (Table 4) revealed that the taxonomic changes compared to controls were sometimes linked to one of the two xenobiotics and sometimes to both (Table 4). Several species exhibited an opposite response in mixtures when compared to treatments applied separately (i.e., S. edax in Ag1As1 and P. paradoxus in Ag2As2).

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present experiment was to study the separate and combined effects of arsenic and silver NPs on meiobenthic nematodes. The size of nanoparticles used in the current experiment (<100 nm) implies that the potentially hazardous space is not pelagic but benthic because the particles have already undergone strong fractionation. The current study included several novel aspects: (1) the taxonomic effects of arsenic and silver NPs have never been studied for meiobenthic nematodes, (2) is it possible or not to use silver NPs for remediation purposes of marine areas contaminated by arsenic? The main goals of the current study were thus to study the individual effects of these xenobiotics and their possible interactions and to measure if Ag NPs are eventually responsible for metal extraction.

4.1. Do Meiobenthic Abundances Change When Exposed to Different Treatments?

Abundances of free-living marine nematodes are generally lower in treated assemblages, except for Ag2As1, with two obvious trends with regard to the nature (single or combined) or the intensity (low or high concentration) of treatments. Indeed, it seems that the increase in the contamination level was associated with a higher negative numerical effect for both types of pollutants. It was easy to provide satisfactory explanations for the low abundances in Ag2 and As2, which were significantly lower than in controls. This may be explained by the potential toxicity of arsenic and Ag NPs in direct contact with nematode cuticles. These xenobiotics are most probably ingested with sediments by deposit feeders. The decrease in abundance under stress is a classic response for meiobenthic nematodes and is in accordance with findings of [27,43,44,45], who confirmed the same outcomes for nickel, cobalt, zinc, chromium, and cadmium. In the case of nanoparticles, no works at all are known in the literature for meiobenthic nematodes. However, it must be said that a nematicidal activity of chitosan-derived silver nanoparticles was documented experimentally against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita that infests tomato plants [46,47].

The fact that microcosms with mixed treatments were discernibly more populated than those with single ones seems to support that Ag NPs possess complexing potential towards arsenic, especially since the abundances of Ag2As1 did not differ significantly from those of UC. At the moment, such assumptions are difficult to confirm since the taxonomic diversity of these worms has not been explored yet.

4.2. How Do Nematodes Respond to the Treatments at the Taxonomic Level?

The same impact of As and Ag NPs on taxonomic diversity was found at the end of the current experiment. Indeed, the microcosms with the highest concentrations of arsenic and silver NPs were significantly less rich in species than all the rest of the assemblages, including the control one. For both types of xenobiotics, C. honestus (2A, co) and Halaphanolaimus sp. (1A, co) appeared as sensitive taxa and M. pristiurus (2B, cla) and D. trabeculosum (1B, cla) as tolerant/opportunistic ones. These responses suggest that these taxa are metal-sensitive regardless of the particle sizes of the pollutant introduced.

The classification above seems to be related first to the trophic level because Ag2 and As2 were characterized by a lower frequency of epistratum feeders (or diatom consumers) and microvores. Thus, benthic diatoms and/or associated bacteria probably emerged as the main targets at 1 mg·L−1 of As or Ag NPs, which contributed to the observed increase in mortality of nematodes 1A and 2A. The literature review of [48] on the uptake and toxicity of silver NPs in autotrophic algae and heterotrophic microbes supported the findings obtained. Indeed, these authors stated that NPs, with large surface-to-volume ratios, are functionalized with target-specific biomolecules and, thus, can efficiently destroy bacteria [49]. Furthermore, it is well known that Ag NPs are commonly used due to their electrical conductivity and wide antimicrobial activity against various microorganisms [50]. Various algal species have also been tested for the toxicity of Ag NPs at various concentrations, namely, Chlorella vulgaris [51], Dunaliella tertiolecta [51], Euglena gracilis [52], and Thalassiosira pseudonana [53]. It appears that, for algal species, the Ag NPs affect the photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry and cause an alteration of the oxygen evolution complex, inhibition of electron transport activity, and structural deterioration of the PSII reaction [54,55]. Similar toxicities were also found for arsenic for both algae [56] and microorganisms [57], which may support a harmful indirect impact of As on nematodes 2A and 1B as previously mentioned for Ag NPs.

SIMPER outcomes showed few other taxonomic changes specific to the exposure to Ag NPs and to As. Thus, the presence of the first xenobiotic was followed by a proliferation of O. calvadocicus (2B, cla) and the second by that of E. longicaudatus (2B, cla). The arsenic was, in contrast, specifically harmful to C. germanicum (2B, co).

Overall, two feeding groups seem to be significantly favored under stress conditions: non-selective deposit feeders (1B) and omnivores and carnivores (2B). The most obvious explanation may be related to Ag NP- and arsenic-induced toxicity for sensitive nematodes (obviously belonging to microvores and epistrate consumers). Indeed, both feeding types of nematodes (i.e., 1B and 2B) may ingest detritus made of corpses of dead prey under decomposition. This is common for 1B nematodes [39] but facultative for 2B ones who may become detritivores depending on the available feeding resources [58].

Another functional axis must be evoked too: the tail shape. It was clear that worms with clavate/conico-cylindrical tails were more encouraged than conical ones. It could be hypothesized here that the first morphotype allows worms to move with large, more frequent, and faster jumps since the tail functions like a spring. In contrast, it is supposed that the conical caudal shape is more sensitive to pollution because of its larger support lateral surface and, so, lower jumping potential in length, frequency, and speediness, which certainly means longer exposure to pollution. An additional potential explanation for such a pattern could also be the possibility of corpses acting as glue, binding to worms with higher lateral surfaces in their caudal part (co).

Arsenic and Ag NPs had a less toxic impact on meiobenthic nematodes when combined compared to their individual effects. This result could be deduced firstly from the abundances observed in Ag2As1 which were comparable to controls and secondly from the outcomes of multivariate analyses. Such an effect was logically related to an antagonism between the two xenobiotics considered. Particularly, the multivariate analysis nMDS showed an interesting significant difference between Ag1As2 and Ag2As1. The first treatment possessed the highest ecotoxicity for meiobenthic nematodes (average dissimilarity with controls = 37.92%), mainly through the harmful effect of As2 (SIMPER outcomes). Thus, it could be suggested that: (1) As2 was able to camouflage Ag1 or (2) Ag1 was not sufficient enough to neutralize As2. The latter hypothesis was finally retained since once more Ag NPs were used in Ag2As2, the toxicity of As2, which was already proved when it was applied individually, was reduced. Following the same principle, Ag1 NPs were also able to neutralize As1. The best depollution performance was reached when the Ag NPs were introduced using the highest concentration (Ag2) against the lowest level of arsenic (As1).

That is why Ag2As1 was numerically and taxonomically the closest treatment to controls with only 19.97% dissimilarity. A similar finding was previously observed for polyvinyl chloride microplastics by [45] and [20] in the case of cadmium and chrysene, respectively. Following the same logic, the formation of aggregates of arsenic on sediment particles to which the NPs become bonded places arsenic internally far from nematodes.

In addition, these aggregates with NPs in the outer border may make the substrate itself coarser and reduce, at least partly, the availability of nanoparticles for nematodes. The particle agglomeration is frequently observed in published works involving silver NPs, especially when they exist in media with high ionic strength (>10 mM) [59]. This agglomeration may also affect their bioavailability by reducing their rate of degradation or cuticular uptake by nematodes, as naturally larger aggregates are less efficiently internalized.

5. Conclusions

The multitude of responses in the current experiment exhibited by the marine nematode communities demonstrates the importance of comprehensive assessments when evaluating the potential risk of released chemicals in the marine realm. Specifically, the highest concentrations of silver nanoparticles and arsenic, when added alone, induced a strong reduction in the overall abundance of nematode communities. The release of silver nanoparticles and arsenic into marine coastal habitats can have a detrimental impact on aquatic fauna. Both compounds seem to make the sediment matrix gluey and have a negative impact on certain trophic guilds, such as the microvores and diatoms feeders.

Another important finding of the current experiment was the fact that the mixed effect of lower and higher dosages of silver nanoparticles and arsenic, respectively, had apparently no negative impact on the taxonomic composition and abundance of nematofauna. It is possible that the combination of both pollutants reduces the overall toxicity by bonding arsenic to silver nanoparticles. The interaction between arsenic and the complexes of silver nanoparticles can be considered an understudied depollution method, important for the protection of living organisms. The results of the current experiment emphasize the need for future ecotoxicological experiments in order to have a better understanding of these intimate interactions among silver nanoparticles, arsenic, and marine nematodes.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, A.H. and S.I.; Validation and writing—original draft, A.A.H.; Review and editing and funding acquisition, N.A.-H.; Literature investigation and formal analysis, M.B.A. and H.A.R.; Statistical analyses, review and editing, conceptualization, and supervision, F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project (number PNURSP2023R437), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data in the article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project (number PNURSP2023R437), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Avio, C.G.; Gorbi, S.; Milan, M.; Benedetti, M.; Fattorini, D.; d’Errico, G.; Pauletto, M.; Bargelloni, L.; Regoli, F. Pollutants bioavailability and toxicological risk from microplastics to marine mussels. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 198, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchaca, I.; Rodriguez, J.G.; Borja, A.; Jesus Belzunce-Segarra, M.; Franco, J.; Garmendia, J.M.; Larreta, J. Determination of polychlorinated biphenyl and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon marine regional sediment quality guidelines with the European water framework directive. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 30, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, A.; Sharma, V. Toxicity assessment of nanomaterials: Methods and challenges. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, N.; Marcato, P.D.; de Conti, R.; Alves, O.L.; Costa, F.T.M.; Brocchi, M. Potential use of silver nanoparticles on pathogenic bacteria, their toxicity and possible mechanisms of action. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010, 21, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, B.K.; Suzuki, K.T. Arsenic round the world: A review. Talanta 2002, 58, 201–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garelick, H.; Jones, H.; Dybowska, A.; Valsami-Jones, E. Arsenic pollution sources. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008, 197, 17–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cubadda, F.; Aureli, F.; Ciardullo, S.; D’Amato, M.; Raggi, A.; Acharya, R.; Reddy, A.V.R.; Tejo Prakash, N. Changes in selenium speciation associated with increasing tissue concentration of selenium in wheat grain. J. Agri. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 2295–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, P.L.; Kinniburgh, D.G. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl. Geochem. 2002, 17, 517–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, P.L.; Kinniburgh, D.G. Source and behavior of arsenic in natural waters. In United Nations Synthesis Report on Arsenic in Drinking Water; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, M.C.; McEvoy, A.J.; Warwick, R.M. The specificity of meiobenthiccommunity responses to different pollutants: Results from microcosm experiments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1994, 28, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suderman, K.; Thistle, D. Spills of Fuel Oil and Orimulsion Can Have Indistinguishable Effects on the Benthic Meiofauna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Essid, N.; Beyrem, H.; Hedfi, A.; Boufahja, F.; Vitiello, P.; Aïssa, P. Effects of hydrocarbon contamination on a free-living marine nematode community: Results from microcosm experiments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Arce, A.; De Jesús-Navarrete, A.; Leasi, F. DNA Barcoding for Delimitation of Putative Mexican Marine Nematodes Species. Diversity 2020, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, M.; Nasri, A.; Harrath, A.H.; Mansour, L.; Alwasel, S.; Beyrem, H.; Plăvan, G.; Rohal-Lupher, M.; Boufahja, F. Do presence of gray shrimp Crangon crangon larvae influence meiobenthic features? Assessment with a focus on traits of nematodes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21303–21313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwick, R.M. The level of taxonomic discrimination required to detect pollution effects on marine benthic communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1988, 19, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Toro, D.M.; Zarba, C.S.; Hansen, D.J.; Berry, W.J.; Swartz, R.C.; Cowan, C.E.; Pavlou, S.P.; Allen, H.E.; Thomas, N.A.; Paquin, P.R. Technical basis for establishing sediment quality criteria for nonionic organic chemicals using equilibrium partitioning. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1991, 10, 1541–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coull, B.C.; Chandler, G.T. Pollution and meiofauna: Field, laboratory and mesocosm studies. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 1992, 30, 191–271. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, K.R.; Todaro, M.A. Influence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on the meiobenthic-copepod community of a Louisiana salt marsh. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1996, 198, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotufo, G.R.; Fleeger, J.W. Effects of sediment-associated phenanthrene on survival, development and reproduction of two species of meiobenthic copepods. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997, 151, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedfi, A.; Ben Ali, M.; Korkobi, M.; Allouche, M.; Harrath, A.H.; Beyrem, H.; Pacioglu, O.; Badraoui, R.; Boufahja, F. The exposure to polyvinyl chloride microplastics and chrysene induces multiple changes in the structure and functionality of marine meiobenthic communities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 12916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, M.; Ishak, S.; Ben Ali, M.; Hedfi, A.; Almalki, M.; Karachle, P.K.; Harrath, A.H.; Abu-Zied, R.H.; Badraoui, R.; Boufahja, F. Molecular interactions of polyvinyl chloride microplastics and beta-blockers (diltiazem and bisoprolol) and their effects on marine meiofauna: Combined in vivo and modelling study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufahja, F. Approches Communautaires et Populationnelles de Biosurveillance du Milieu Marin chez les Nématodes Libres (Lagune et Baie de Bizerte, Tunisie). Ph.D. Thesis, Biological Sciences, Faculty of Sciences of Bizerte (University of Carthage, Tunisia), Carthage, Tunisia, 2010; 300p. [Google Scholar]

- Hedfi, A.; Boufahja, F.; Ben Ali, M.; Aïssa, P.; Mahmoudi, E.; Beyrem, H. Do trace metals (chromium, copper and nickel) influence toxicity of diesel fuel for free-living marine nematodes? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 3760–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedfi, A.; Ben Ali, M.; Noureldeen, A.; Darwish, H.; Mahmoudi, E.; Plăvan, G.; Pacioglu, O.; Boufahja, F. Effects of benzo(a)pyrene on meiobenthic assemblage and biochemical biomarkers in an Oncholaimus campylocercoides (Nematoda) microcosm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 16529–16548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, J.B. Measurement of the physical and chemical environment: Sediments. In Methods for the Study of Marine Benthos. International Biological Programme Handbook No. 16; Holme, N., McIntyre, A., Eds.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1971; 334p. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano, M.; Danovaro, R. Composition of organic matter in sediment facing a river estuary (Tyrrhenian Sea): Relationships with bacteria and microphytobenthic biomass. Hydrobiologia 1994, 277, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufahja, F.; Hedfi, A.; Amorri, J.; Aïssa, P.; Beyrem, H.; Mahmoudi, E. Examination of the bioindicator potential of Oncholaimus campylocercoides (Nematoda, Oncholaimidae) from Bizerte bay (Tunisia). Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.A.; Bonin, V.; Reed, M.; Graham, B.J.; Hood, G.; Glattfelder, K.; Reid, R.C. Anatomy and function of an excitatory network in the visual cortex. Nature 2016, 532, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Test methods for evaluating solid waste. In Vol. IB: Laboratory Manual Physicallchemical Methods. SW-846; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/ (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- ANZECC/ARMCANZ. Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality, Vol. 1. The Guidelines; Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council and Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New Zealand: Auckland, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, M.S.; Santos, H.M.; Costa, P.M.; Peres, I.; Costa, M.H.; Capelo, J.L. Metallothionein responses in the Asiatic clam (Corbicula fluminea) after exposure to trivalent Arsenic. Biomarkers 2007, 12, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, A.; Zeng, G.; Xiao, R.; Guo Zhi, Y.F.; Huang, Z.; He, K.; Hu, L. Toxicity effects of silver nanoparticles on the freshwater bivalve Corbicula fluminea. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4236–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, P.; Dinet, A. Définition et échantillonnage du méiobenthos. Rapp. Comm. Int. Expl. Sci. Mer. Médit. 1979, 25, 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Somerfield, P.J.; Warwick, R.M.; Zhang, Z. Large-scale patterns in the community structure and biodiversity of free-living nematodes in the Bohai Sea, China. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2001, 81, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinhorst, J.W. A Rapid Method for the Transfer of Nematodes From Fixative To Anhydrous Glycerin. Nematologica 1959, 4, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, H.M.; Warwick, R.M. Free-Living Marine Nematodes. Part I. British Enoplids. Synopses of the British Fauna No 28; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983; 314p. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, H.M.; Warwick, R.M. Free-Living Marine Nematodes. Part II. British Chromadorids. Synopsis of the British Fauna (New Series) No. 38; Brill, E.J., Backhuys, W., Eds.; The Linnean Society of London: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, T.N.; Decraemer, W.; Eisendle-Flöckner, U.; Hodda, M.; Holovachov, O.; Leduc, D.; Miljutin, D.; Mokievsky, V.; Peña Santiago, R.; Sharma, J.; et al. Nemys: World Database of Nematodes. 2019. Available online: http://nemys.ugent.be/ (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Wieser, W. Die Besiehung zwischen Mundhchlen-gestalt, Ernährungsweise und. Vorkommen beifreilbenden marinen Nematoden. Ark. Zoop. Ser. 1953, 2, 439–484. [Google Scholar]

- Thistle, D.; Lambshead, P.J.D.; Sherman, K.M. Nematode tail-shape groups respond to environmental differences in the deep sea. Vie Milieu/Life Environ. 1995, 45, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Glorley, R.N. PRIMER v5: User Manual/Tutorial; PRIMER-E: Polymouth, UK, 2001; 91p. [Google Scholar]

- Hedfi, A.; Mahmoudi, E.; Boufahja, F.; Beyrem, H.; Aïssa, P. Effects of increasing levels of nickel contamination on structure of offshore nematode communities in experimental microcosms. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 79, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyrem, H.; Boufahja, F.; Hedfi, A.; Essid, N.; Aïssa, P.; Mahmoudi, E. Laboratory study on individual and combined effects of cobalt- and zinc-spiked sediment on meiobenthic nematodes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 144, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakkaf, T.; Allouche, M.; Harrath, A.H.; Mansour, L.; Alwasel, S.; Ansari, K.G.M.T.; Beyrem, H.; Sellami, B.; Boufahja, F. The individual and combined effects of cadmium, Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microplastics and their polyalkylamines modified forms on meiobenthic features in a microcosm. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, G.C.; Fitch, J.; Min, B.; Shahi, N.; Egnin, M.; Ritte, I.; Collier, W.E.; Bonsi, C. Potential Nematicidial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Against the Root-Knot Nematode (Meloidogyne incognita). Online J. Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2, 000531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, R.Y.; Shams El-Din, N.G.E.; Maghraby, D.M.E.; Ibrahim, D.S.S.; Abdel-Megeed, A.; Abdelsalam, N.R. Nematicidal activity of seaweed-synthesized silver nanoparticles and extracts against Meloidogyne incognita on tomato plants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M.; Dubey, N.K.; Chauhan, D.K. Silicon nanoparticles more effectively alleviated UV-B stress than silicon in wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Cui, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Capsules with silver nanoparticle enrichment subdomains and their antimicrobial properties. Chem. Asian J. 2010, 5, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Raghavendra, G.M.; Kim, D.; Seo, J. An investigation on the antibacterial, cytotoxic, and antibiofilm efficacy of starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 8, 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- Oukarroum, A.; Bras, S.; Perreault, F.; Popovic, R. Inhibitory effects of silver nanoparticles in two green algae, Chlorella vulgaris and Dunaliella tertiolecta. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 78, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Schirmer, K.; Bernard, L.; Sigg, L.; Pillai, S.; Behra, R. Silver nanoparticle toxicity and association with the alga Euglena gracilis. Environ. Sci. Nano 2015, 2, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, A.D.; Carvalho, R.N.; Valente, A.; Nativo, P.; Gilliland, D.; Garcìa, C.P.; Passarella, R.; Pedroni, V.; Rossi, F.; Lettieri, T. Effects of silver nanoparticles in diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana and cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11336–11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Piccapietra, F.; Wagner, B.; Marconi, F.; Kaegi, R.; Odzak, N.; Sigg, L.; Behra, R. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8959–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Tran, I.; Agrawal, A.F. Does genetic variation maintained by environmental heterogeneity facilitate adaptation to novel selection? Am. Nat. 2016, 188, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, S.; De Francisco, P.; Olsson, S.; Aguilera, A.; González-Toril, E.; Martín-González, A. Toxicity, Physiological, and Ultrastructural Effects of Arsenic and Cadmium on the Extremophilic Microalga Chlamydomonas acidophila. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francisco, P.; Martín-González, A.; Rodriguez-Martín, D.; Díaz, S. Interactions with Arsenic: Mechanisms of Toxicity and Cellular Resistance in Eukaryotic Microorganisms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, T.; Vincx, M. Observations on the feeding ecology of estuarine nematodes. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1997, 77, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skebo, J.E.; Grabinski, C.M.; Schrand, A.M.; Schlager, J.J.; Hussain, S.M. Assessment of metal nanoparticle agglomeration, uptake, and interaction using a high-illuminating system. Int. J. Toxicol. 2007, 26, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).