Abstract

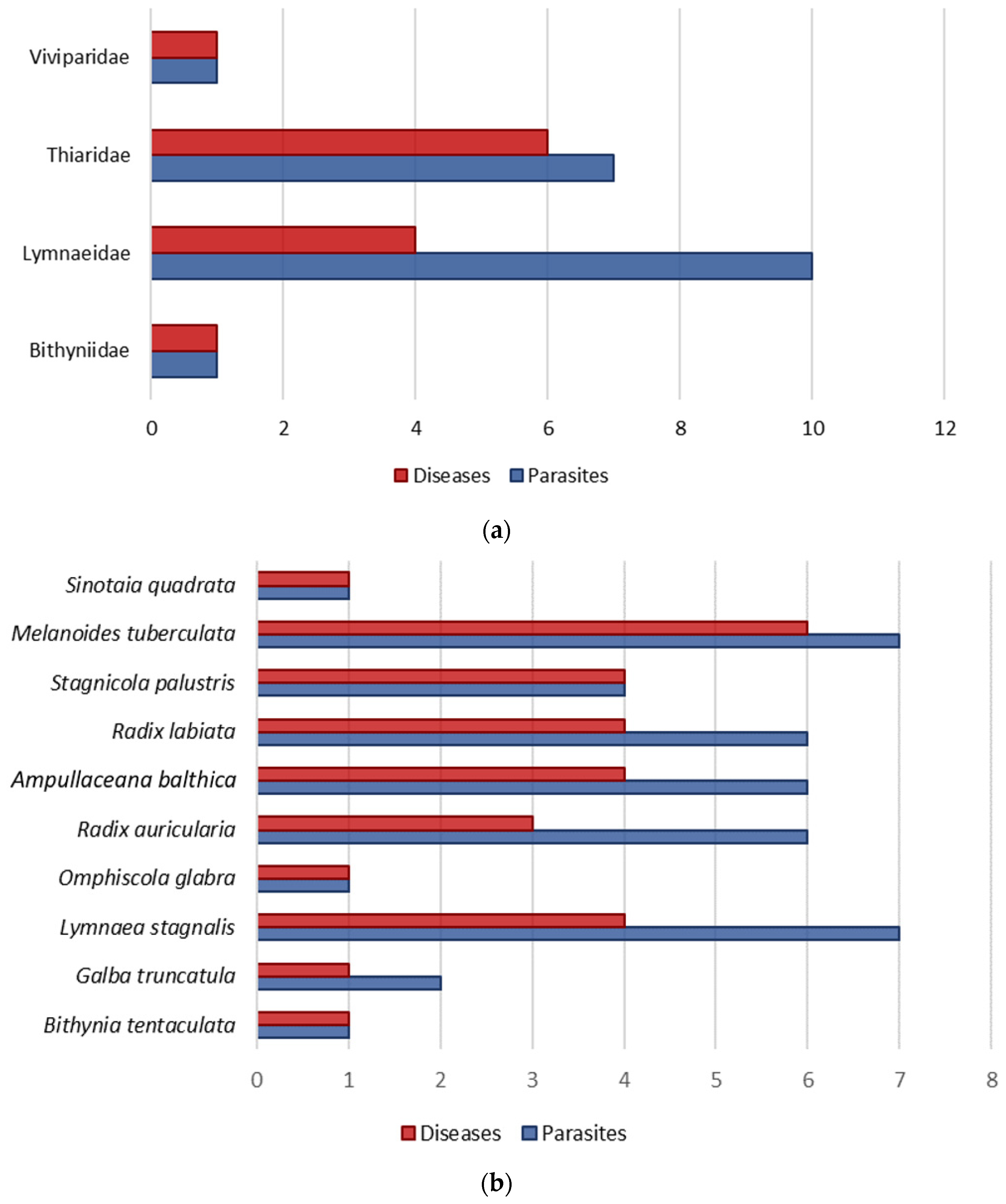

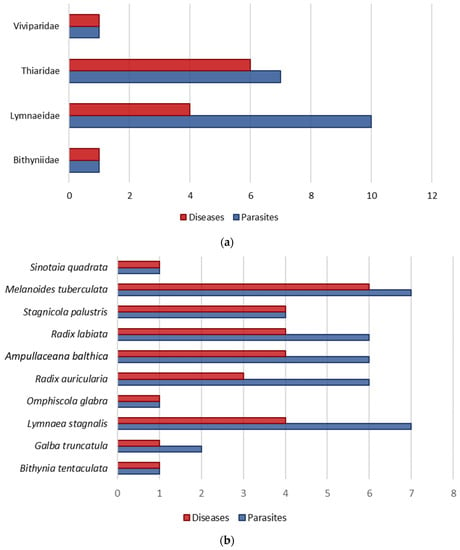

Land and freshwater molluscs are the most abundant non-arthropod invertebrates from inland habitats worldwide, playing important ecological roles and some being important pests in agriculture. However, despite their ecological, and even economic and sanitary importance, their local diversity in many European regions is not perfectly understood, with a particularly notableknowledge gap in the northern Iberian malacofauna. This work aims at providing a revised checklist of continental gastropods and bivalves from the Asturias (northern Spain), based on the examination of newly collected and deposited material and on the critical analysis of published and gray literature. A total of 165 molluscan species are recognized. Ten species constitute new records from Asturias and seven from northern Iberian Peninsula. Seventeen species are introduced or invasive, evidencing the current increase of the bioinvasion rate in continental molluscs. Furthermore, all these exotic species are parasite transmitters or trematode intermediate hosts, and thus represent a potential bio-sanitary risk for human and other animal health. The provided data strongly suggest that the increase of invasive freshwater snail species can lead to an increase in parasitic infections, and this is a crucial point that transcends the merely scientific to the political-social sphere.

1. Introduction

Land and freshwater snails and slugs are mostly heterobranch gastropods (except for some operculate snails that are caenogastropods) inhabiting many different inland habitats worldwide. Overall continental gastropods and bivalves play important ecological roles as prey for many species of birds and small mammals, predators of other invertebrates or as scavengers or filter-feeding organisms. Furthermore, they have attracted attention in the last decade not only for its surprising and unknown diversity [1,2,3,4,5] but also for other aspects, from being indicators of climate change and evolutionary responses (e.g., Cepaea nemoralis) to a sentinel species of wetlands, ponds, and streams environmental quality [6,7]. Some species of land snails and slugs eat plants, including vegetables, fruits and garden flowers and thus they can destroy young plants, ruin crops and constitute an important pest in many countries [8,9]. Other species feed on another invertebrate groups such as earthworms and flatworms or even on other snails or slugs [10,11].

Several snail and slug species are also important from a medical or veterinary point of view, since they can act as first hosts of several trematode worms or being transmitters of nematodes or other parasites [12,13,14]. Parasitic diseases cause serious public health problems worldwide and according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the number of worldwide deaths from infectious parasitic diseases exceeded one and a half million only in 2017 [15].

Many species of parasitic worms (called ‘helminths’ in medical-veterinary terminology) are responsible for several of the most worldwide prevalent parasitosis (e.g., hookworms or schistosomiasis). ‘Helminth’ is a term which groups animals distributed among three phyla: Nematoda, Platyhelminthes and Acanthocephala [16]. However, helminth- caused diseases have suffered a lack of attention on the part of medicine and human sociology [17]. The trematodes are divided into two subclasses: Digenea Carus 1863, the one with the greatest medical and veterinarian importance [18] and Aspidogastrea Faust & Tang, 1936. Digenea flatworms (commonly known as ‘digestive flukes’) include about 9000 species that can parasitize both humans and domestic animals and can be found thoughout the entire body, from the digestive tract and bile and pancreatic ducts to the lung circulatory and genitourinary system [16,19].

Trematodes have a complex life cycle that involves at least four larval stages that occur inside the first intermediate host, which is usually a mollusc [20,21]. The mollusc species that act as trematode intermediate hosts generally belong to the Class Gastropoda, which includes both slugs and land, marine and freshwater snails [3,18] that are widespread in most geographic regions [21]. Most trematodes are highly specific and need a particular species for completing their life cycle, while a smaller part of them are more generalist and can complete their cycle using different species as intermediate hosts [20,22].

Land and freshwater snails, slugs and bivalves have been introduced unintentionally and intentionally to many regions worldwide [23,24]. These introduced species, when become invasive, have greatly impacts on native biodiversity, i.e., preying upon or outcompeting native species, transferring pathogens and parasites, causing community and ecosystem level imbalances or even facilitating the introduction of other species [9,23,25]. In the same way, they may generate significant economic losses, mainly to agriculture, and even they can affect human health [8,9,21,23]. At this critical juncture, these introduced molluscs, together with their trematodes and other parasites, can spread to new areas, generating new bio-sanitary risks in the receiving ecosystems that can affect the human population nearby. Therefore, it is imperative to exactly know the real diversity and the specific identity of the snails that can act as intermediate hosts in one region for evaluate the potential bio-sanitary risk, prevalence and dissemination of trematode infections.

The Iberian Peninsula is one of the largest European peninsulas and constitutes the south-westernmost part of Europe. It is bordered on the southeast and east by the Mediterranean Sea and on the north, west, and southwest by the Atlantic Ocean. Due to these geographical features, the Iberian Peninsula harbors different climate types, with the Oceanic climate from the North to northwestern part and the Mediterranean one in the Centre and southern regions standing out. It also presents Alpine and the Subarctic climate zones in the higher mountains of northern Spain (mainly the Cantabrian Mountains and the Pyrenees) [26]. From the biogeographical perspective, the Iberian Peninsula is considered one of the most important Pleistocene glacial refugia of the European subcontinent, harboring a remarkable biological diversity including endemic species [3].

The Principality of Asturias is one of the largest territories of the north of the Iberian Peninsula. There are many favorable habitats for being colonized by multiple species of terrestrial and freshwater snails, slugs and bivalves. However, the knowledge of Asturian malacofauna is scarce, fragmentary and insufficient [2]. In the same way, even less is known about the effects of mollusc invasions, their potential risks or the prevalence and number of species that act as intermediate hosts of medical-veterinary importance trematodes. So, the main goals of this work are: (a) to carry out an updated review of freshwater and terrestrial molluscs of Asturias, (b) to assess the invasive potential of the new arrived species to the studied territory and (c) to evaluate the bio-sanitary risk associated with the reported molluscs through the elaboration of a list confronting the recorded species with the potential trematodes that can host and the subsequent trematodiasis in humans.

2. Materials and Methods

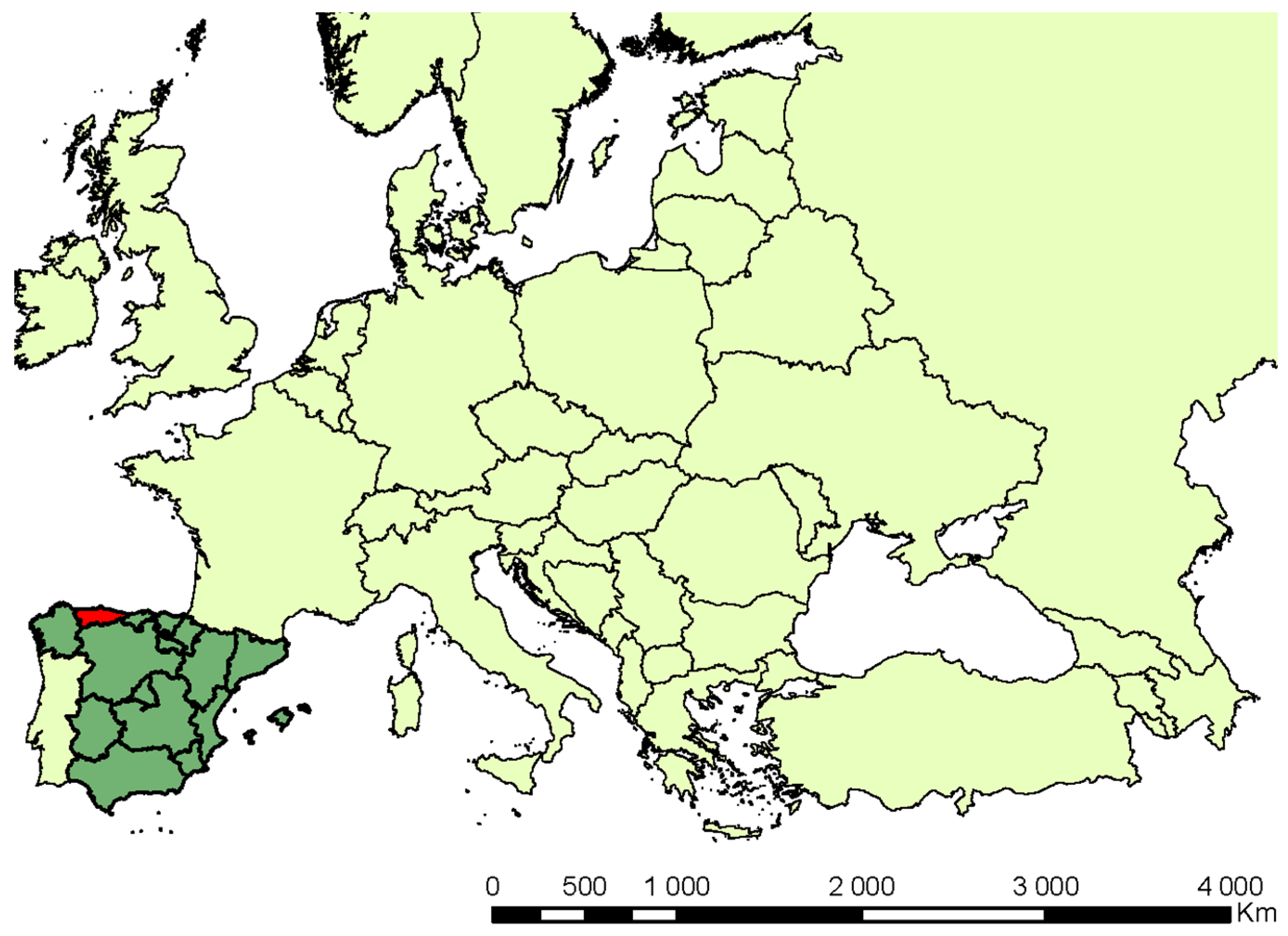

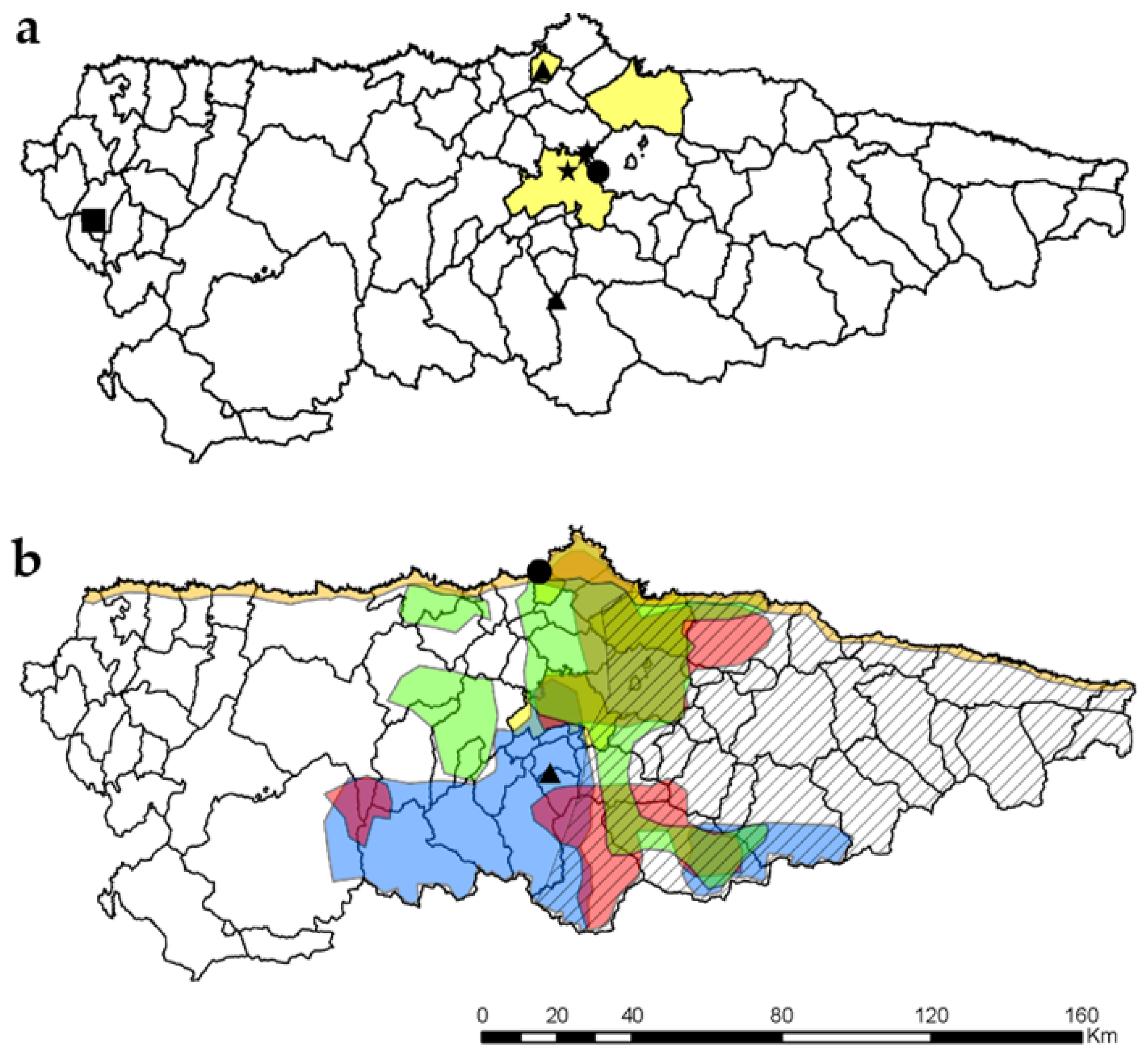

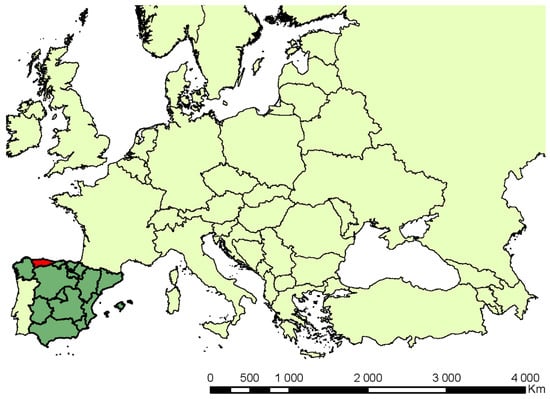

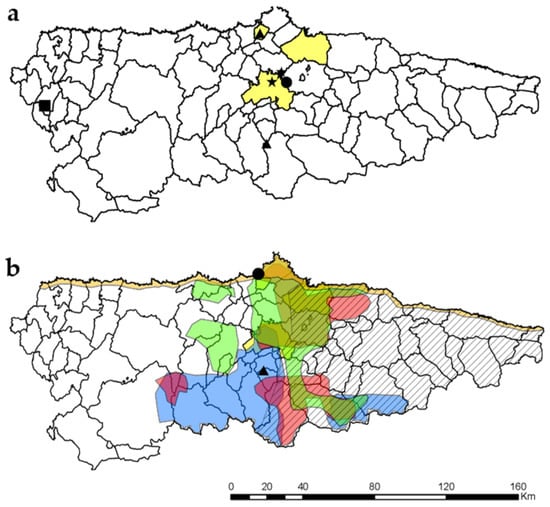

Several seasonal samplings were carried out throughout the Principality of Asturias (2010–2020, Figure 1) looking for molluscs (details of collection date and locality are specified in the respective species sections in ‘Results’ for the new records). In addition, the material from the Collection of the Department of Organisms and Systems (BOS) of the University of Oviedo, in which several mollusc species from previous studies are stored [27,28,29], was revised. For the elaboration of the mollusc checklist, an exhaustive review of the Asturian available bibliography was carried out. The species status was assigned following the guidelines of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). A ‘native species’, ‘autochthonous’ or ‘indigenous’ species is one original from a specific geographical site (here, the Principality of Asturias) without human intervention of any kind. Terms of ‘introduced species’, ‘exotic’, ‘alien’ or ‘non-native’ refer to that species introduced by humans (intentionally or not) outside its present or past range of distribution. Furthermore, an ‘invasive alien species’ is considered that species established outside its range of natural distribution, both present and past, whose introduction and/or expansion supposed a threat to indigenous biological diversity. In addition to these terms, the term ‘cryptogenic species’ refers to a species without certainty about its native or introduced origin, due to a lack of study or other impediments [30]. The European distribution of molluscs was obtained from Welter-Schultes [2] and the Iberian ones from Cadevall and Orozco [3] and our own observations. The ecological data of the Malacofauna was obtained from Cadevall and Orozco [3] and our own observations. The list of trematodes was obtained through a literature review of trematodes associated with all the potential intermediate host species in the Principality of Asturias of molluscs. Only those trematode species with confirmed cases of infection in humans (i.e., trematodiasis) were considered to cause disease. Distribution maps were generated with ArcMap 10.8.1 (ArcGis, Redlands, CA, USA).

Figure 1.

Geographical situation of the Principality of Asturias (red) in Spain (dark green) and within Europe.

3. Results

3.1. Annotated Checklist

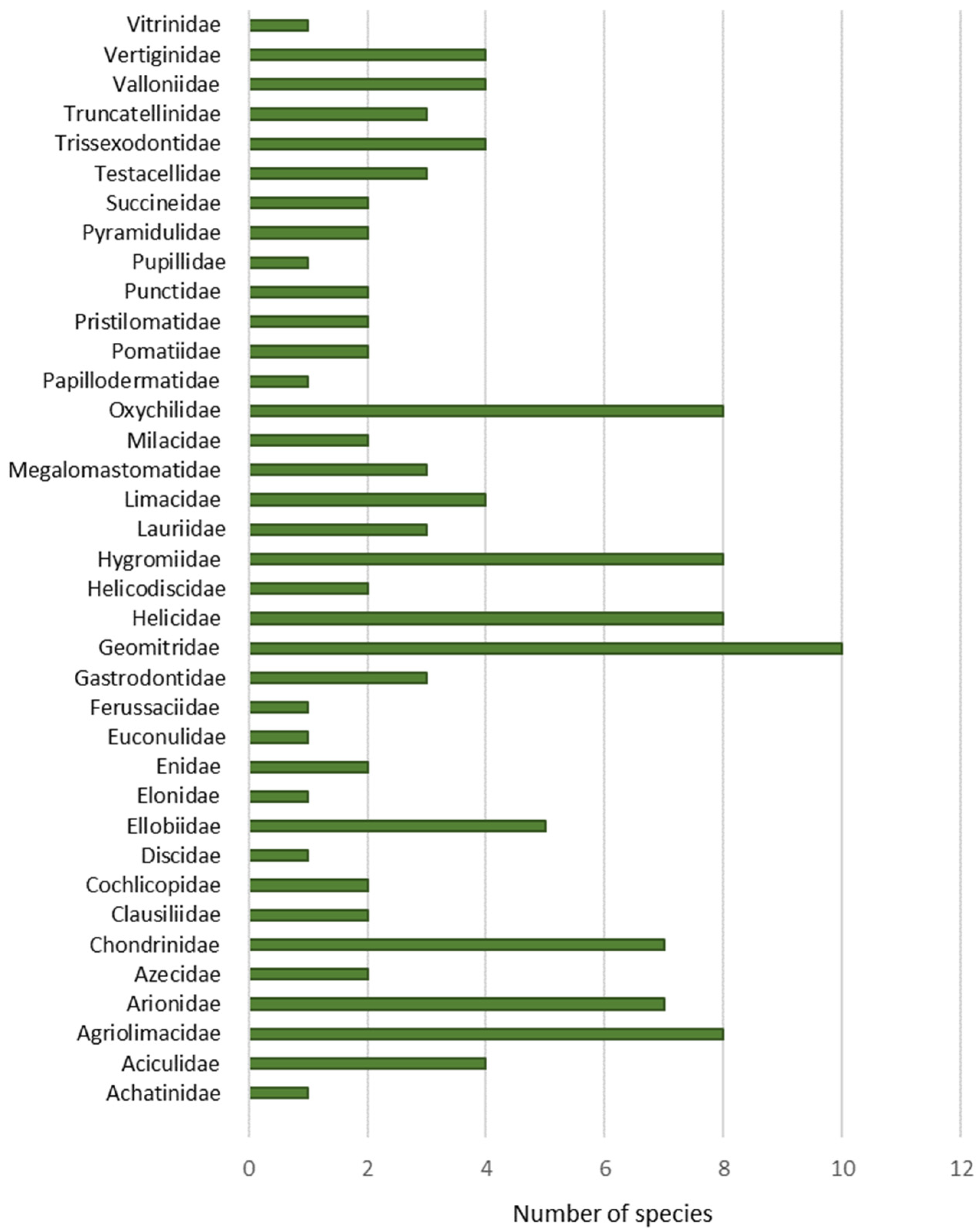

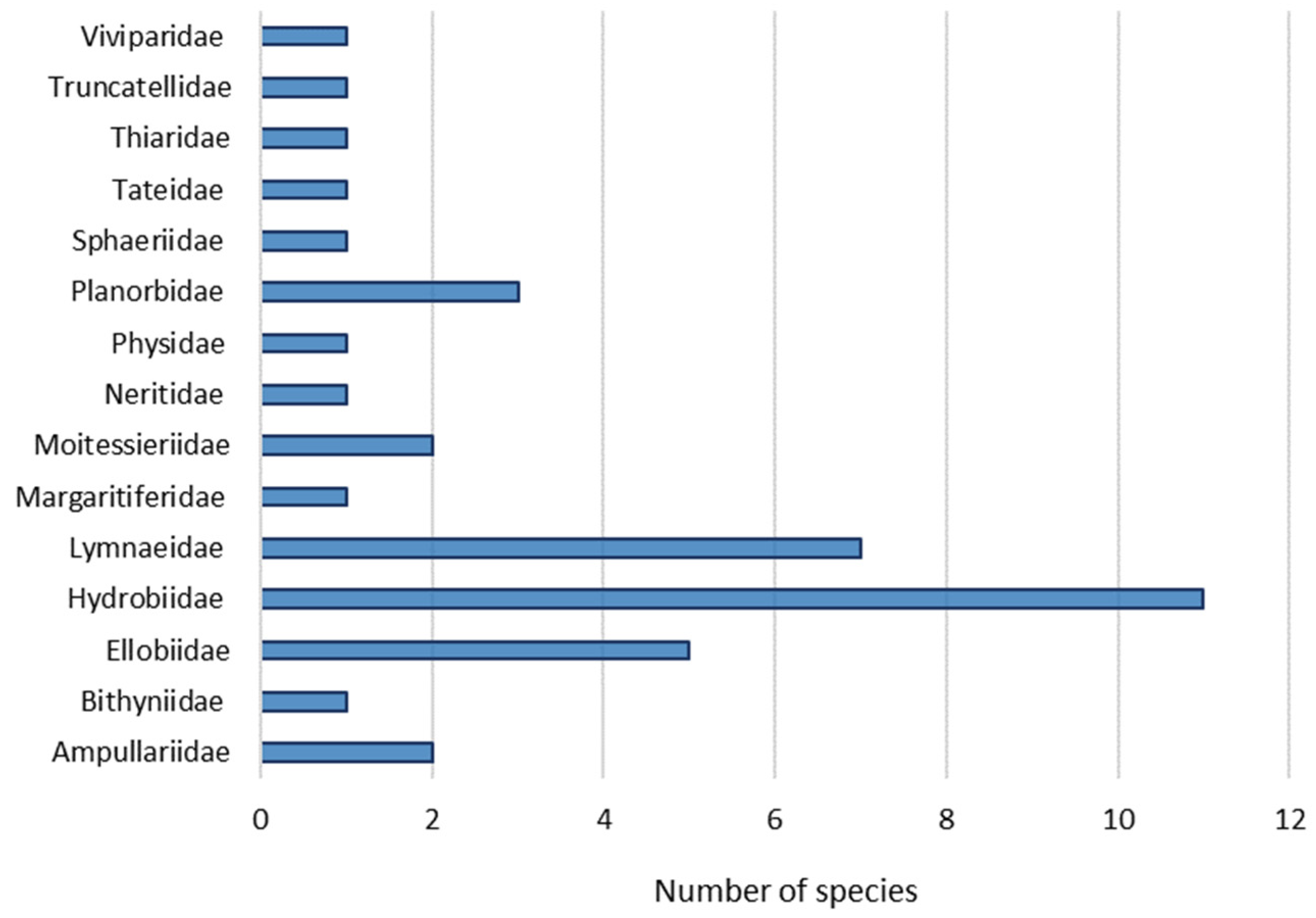

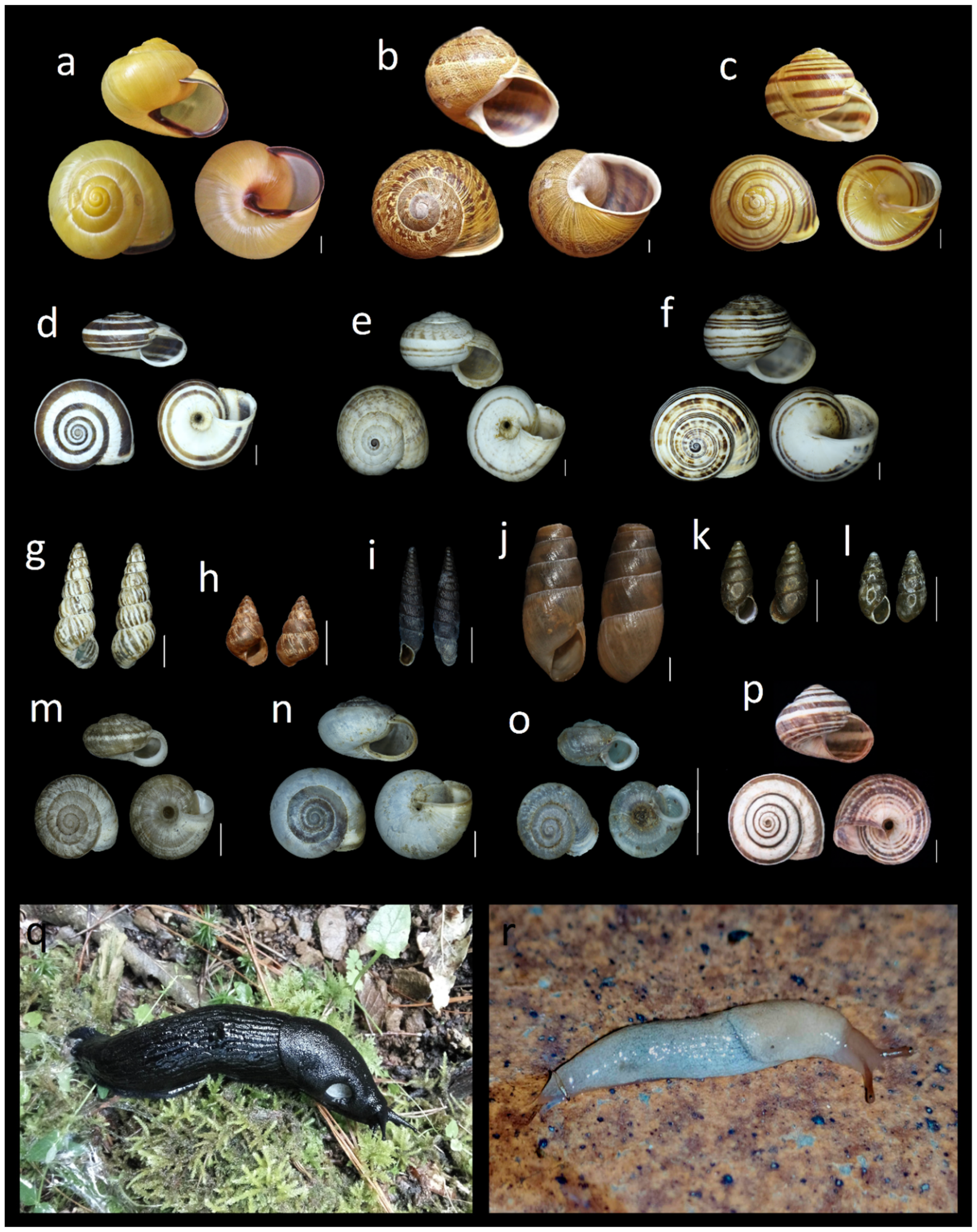

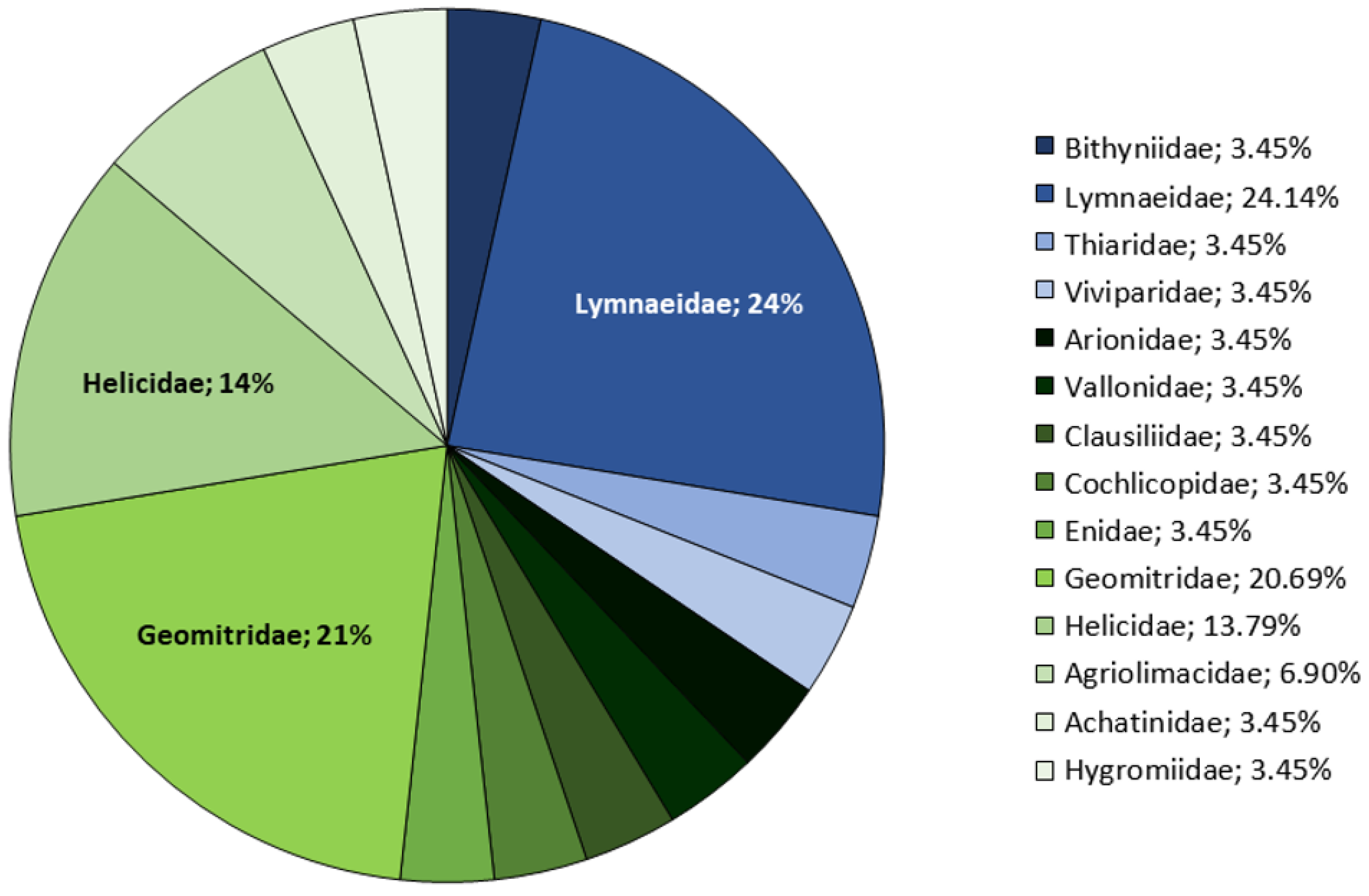

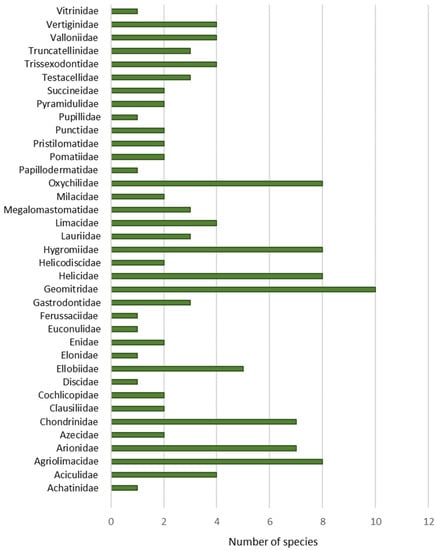

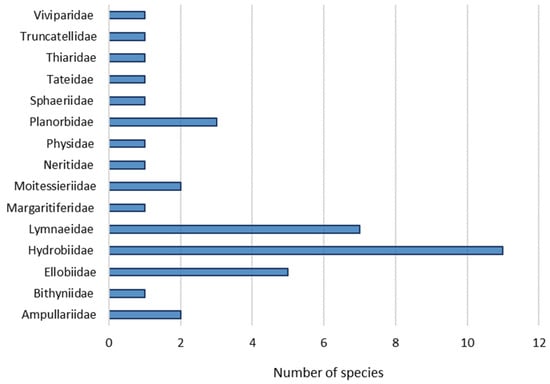

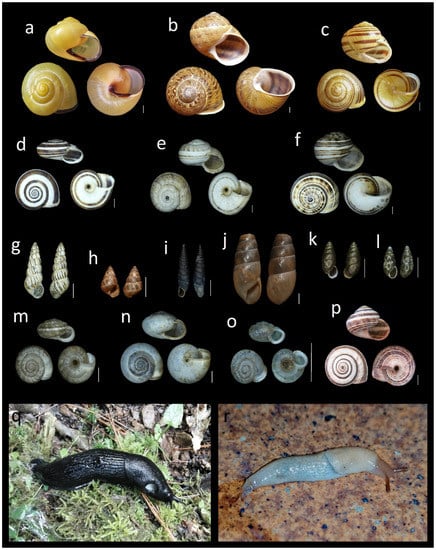

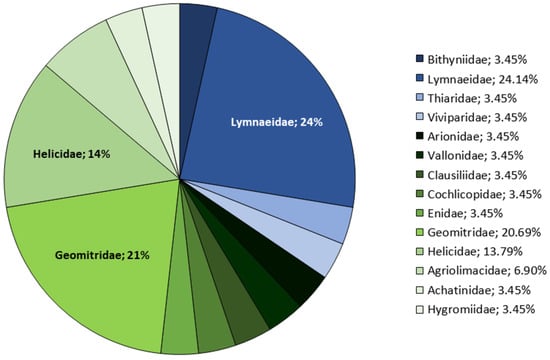

A total of 165 molluscs species has been recorded in the Principality of Asturias. The malacological fauna is composed by 138 snails (83.6%), 25 slugs (15.2%) and two mussels (1.2%) (Table A1 and Table A2). Among snails, there are 37 aquatic species (26.8%) (Table A1) and 101 (73.2%) with terrestrial habits (Table A2).

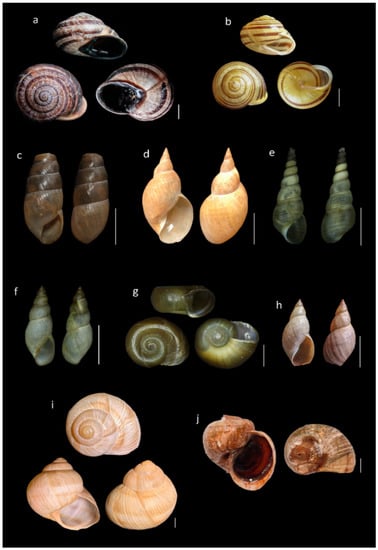

According to their status, 141 native species (85.45%) have been recorded (117 snails, 22 slugs, two mussels). Furthermore, there are 15 (9%) introduced species (14 snails and one slug), seven (4.2%) with no clear origin catalogued as cryptogenic (five snails and two slugs) and two (1.2%) invasive aquatic snail species. Of them, ten species constitute new records from the Asturian malacofauna (Figure 2).

Phylum Mollusca

Class Gastropoda Cuvier, 1795

Order Cycloneritida Haller, 1890

Superfamily Neritoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Neritidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Theodoxus Montfort, 1810

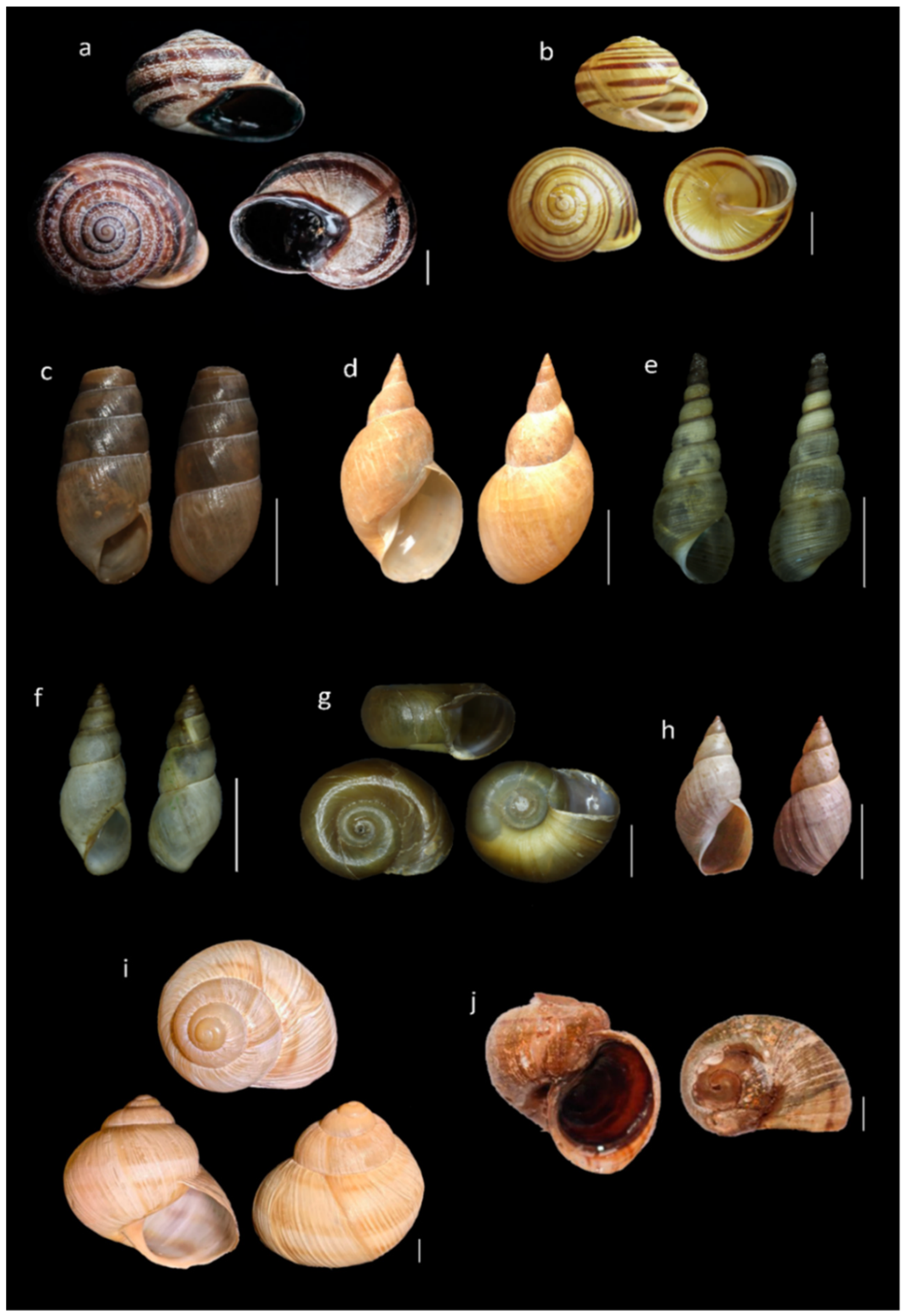

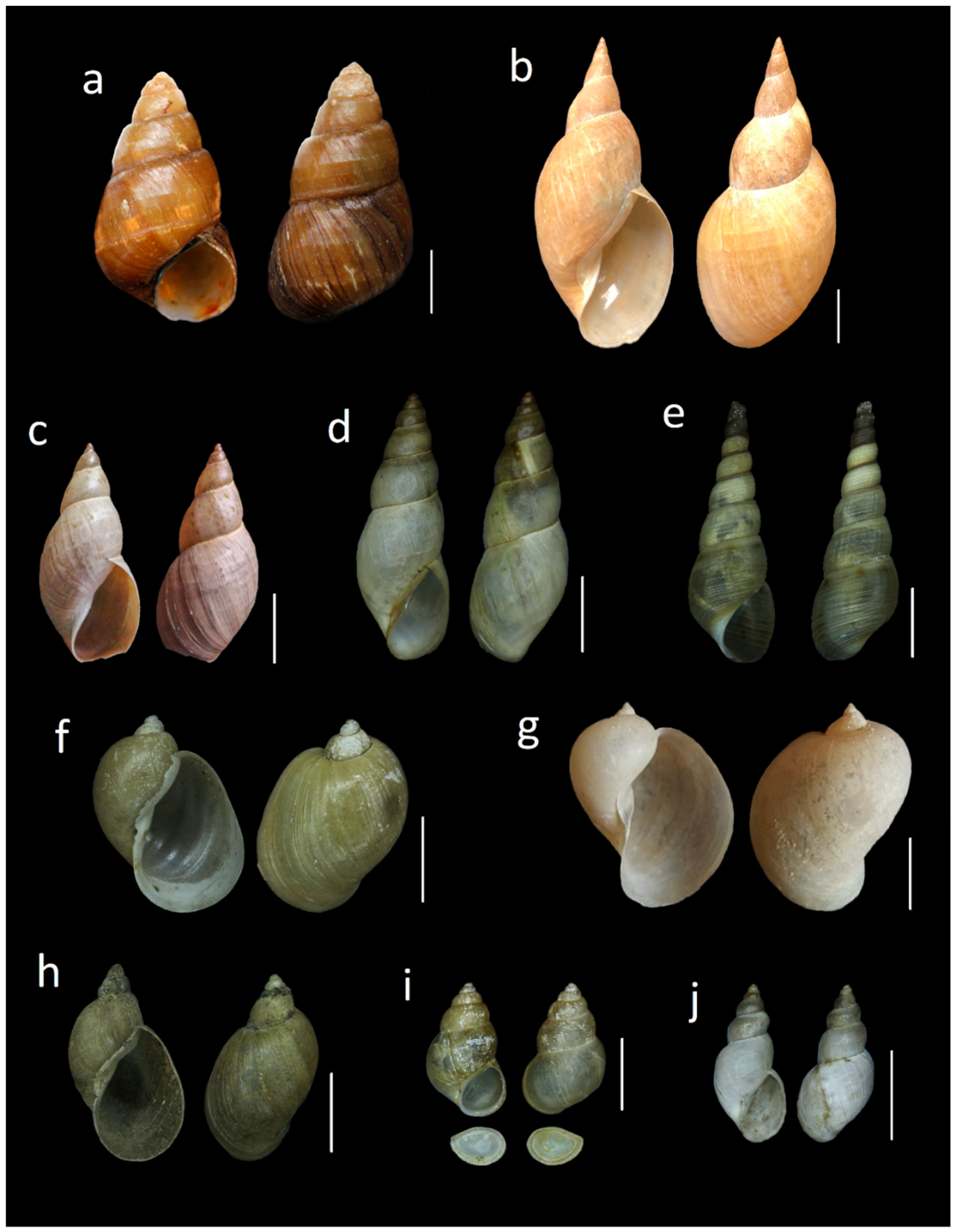

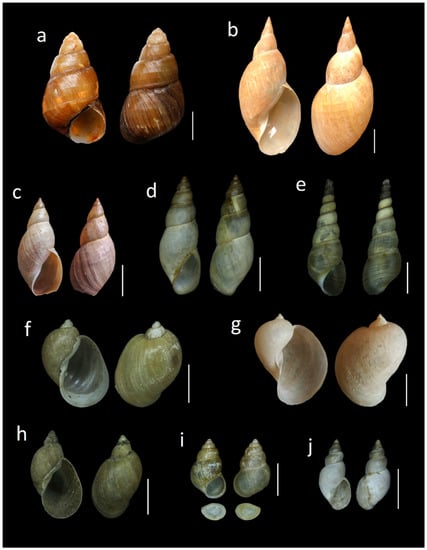

Figure 2.

New species records for the Asturian malacofauna. (a) Otala lactea (La Corredoria-Oviedo), (b) Cepaea hortensis (Grandiella, Riosa), (c) Rumina decollata (dune system of San Juan de Nieva-Avilés), (d) Lymnaea stagnalis (Villanueva de Oscos pond), (e) Melanoides tuberculata (Nora River-Oviedo), (f) Omphiscola glabra (temporary pond in Avilés), (g) Planorbella duryi (Nalón River-El Entrego, San Martín del Rey Aurelio), (h) Stagnicola cf. palustris (spring in Lugones-Siero), (i) Helix pomatia (Isabel la Católica park-Gijón), (j) Pomacea cf. maculata (San Andrés de los Tacones reservoir-Gijón). All scale bars 1 cm.

3.1.1. Theodoxus fluviatilis fluviatilis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Aquatic species widely distributed in Europe and the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias. It generally lives in the medium-high stretches of streams and rivers with clean waters. It lives on stones where it feeds on diatoms and detritus The Asturian record under the name Theodoxia bourguignati (Recluz, 1852) [31,32] corresponds to T. fluviatilis.

Order Architaenioglossa Haller, 1890

Superfamily Ampullarioidea Gray, 1825

Familiy Ampullariidae Gray, 1824

Genus Marisa Gray, 1824

3.1.2. Marisa cornuarietis (Linnaeus, 1758)

This aquatic species inhabits the rivers and lagoons of Central America and the North of South America [33]. Recently a population of this species was found in the Nora River, near the town of Colloto (Oviedo) [34]. They argued that this species could have arrived due to the pet and aquarium trade, followed by its subsequent escape or release of specimens in the area.

Genus Pomacea Perry, 1810

3.1.3. Pomacea cf. maculata Perry, 1810

This is an aquatic species native to South America. In recent years, it has invaded numerous countries, producing several damages, especially colonizing rice plantations [35]. It has been introduced in tropical and subtropical countries, as well as certain temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, such as the United States [35,36]. In the Iberian Peninsula, its presence has been reported in Ebro River, causing serious problems [35]. This species lives preferably in low-flow fresh waters (lagoons, estuaries and some rivers) where it feeds on aquatic plants. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. This snail was found alive in the San Andrés de los Tacones (Gijón) reservoir in 2018. The potential introduction pathway of this species is probably associated with ornamental plant species or through pet trade and subsequent escape or release.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: San Andrés de los Tacones reservoir (Gijón): five alive specimens. 2018. (30TTP77382018).

Superfamily Cyclophoroidea Gray, 1847

Family Megalomastomatidae Blanford, 1864

Genus Obscurella Clessin, 1889

3.1.4. Obscurella asturica Raven, 1990

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula only known from the Desfiladero de los Beyos and the Lagos de Covadonga where its type locality is found [37]. A rare and sparsely distributed species in Asturias. It lives in rocks and limestone walls in sympatry with O. hidalgoi.

3.1.5. Obscurella bicostulata (Gofas, 1989)

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula limited to the center and east of the Cantabrian coast. A frequent species in Asturias. It lives in rocks and limestone walls, occasionally in sympatry with O. hidalgoi. Anadón and Anadón [27] recorded Cochlostoma (Anotus) berilloni (Bassoon, 1880) in Roces and Gato Mountains. However, after reviewing the material, it has turned out to correspond to an identification error with O. bicostulata, a non-described species at the time.

3.1.6. Obscurella hidalgoi (Crosse, 1864)

Species of Iberian-French distribution located in the eastern half of the Cantabrian coast. Frequent species in Asturias, it lives in rocky areas and limestone walls, occasionally in sympatry with O. bicostulata and more specifically in its limited area of distribution, with O. asturica [37].

Family Aciculidae Gray, 1850

Genus Acicula W. Hartmann, 1821

3.1.7. Acicula fusca (Montagu, 1803)

Species distributed in Western Europe. It is mainly located in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias. It lives in very humid environments normally buried in the ground, although it can also live among moss or in the soil mulch.

Genus Menkia Boeters, E. Gittenberger & Subai, 1985

3.1.8. Menkia horsti Boeters, E. Gittenberger & Subai, 1985

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias, although it is only known from a few localities, including its type locality, the Cueva de Tito Bustillo in Ribadesella [38]. It has also been found in Cantabria [39]. It lives in moist environments, generally buried in the ground in areas with loose soil, although it can also live among moss and other humid microenvironments.

3.1.9. Menkia rolani E. Gittenberger, 1991

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. Rare species in Asturias known from few localities, including its type locality in Grado [40]. The habitat in which this species has been found is similar to M. horsti.

Genus Platyla Moquin-Tandon, 1856

3.1.10. Platyla callostoma (Clessin, 1911)

Species distributed throughout western Europe. Limited to the north Iberian Peninsula, specifically to the provinces of Asturias, Cantabria and certain areas of Catalonia. Rare species in Asturias, known only from the east extreme [41]. It lives in humid microenvironments like mosses and leaf litter.

Superfamily Viviparoidea Gray, 1847

Family Viviparidae Gray, 1847

Genus Sinotaia Gray, 1847

3.1.11. Sinotaia cf. quadrata (Benson, 1842)

This aquatic species inhabits the rivers and lagoons of China, Korea, and Taiwan and was later introduced in Japan, Thailand and the Philippines [42]. Sinotaia quadrata has also been introduced in South America, specifically in Argentina [43] and in the Arno River of Italy [44]. Recently, a population of this species in the Nora River near the town of Colloto (Oviedo) was found [45] and argued that this species could have been associated with an ornamental plant species (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms) located in the nearby Nora River.

Order Littorinimorpha Golikov & Starobogatov, 1975

Superfamily Littorinoidea Children, 1834

Family Pomatiidae Newton, 1891 (1828)

Genus Pomatias S. Studer, 1789

3.1.12. Pomatias elegans (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species widely distributed in Europe and North Africa. In the Iberian Peninsula it extends through central Portugal and the Cantabrian and the Mediterranean coast. Frequent species in Asturias that can become locally abundant once located. Well adapted to anthropized environments. It also frequents rocky walls where it hides in crevices and forests, selecting soils with a lot of humus or inhabiting very humid microhabitats.

Genus Leonia Gray, 1850

3.1.13. Leonia mammillaris (Lamarck, 1822)

Species distributed throughout North Africa and the southeast part of the Iberian Peninsula (Alicante, Murcia and Almería). In Asturias, only one single record is known: an empty shell found in August of 1988 on a small beach located in the south of Misiego, in the Villaviciosa estuary [46]. Its origin is uncertain, and it seems more likely that it was introduced due to passive transport in vehicles since it is a very crowded place [46].

Superfamily Cerithioidea J. Fleming, 1822

Family Thiaridae Gill, 1871 (1823)

Genus Melanoides Olivier, 1804

3.1.14. Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774)

This aquatic species inhabits the rivers and lagoons of tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia and Australia [47]. This species has been introduced many times outside its native range including North, South and Central America [48]. It has also been introduced to many countries of Europe [47]. In the Iberian Peninsula it was recorded from Aragón (Zaragoza), Valencia (Castellón) and the Canary Islands [47,49]. In 2010, it was detected in the Ebro River basin, concretely in the town of l’Aldea [47]. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. During a series of monitoring surveys carried out in 2017, some adults of this snail were found in the rocks of the riversides of Nora River, near to the locality of Colloto. In addition, some juveniles were found among river sand at the same locality. As an aquarium species it could come associated with ornamental plant (common in the area) or through pet trade and subsequent release.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Nora River (Oviedo): eight adults and ten juveniles. 2017. (30TTP74080669).

Superfamily Truncatelloidea Gray, 1840

Family Truncatellidae Gray, 1840

Genus Truncatella Risso, 1826

3.1.15. Truncatella subcylindrica (Linnaeus, 1767)

Species widely distributed along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts, distributed along the entire coast of the Iberian Peninsula. It is a rare species in Asturias that inhabits rocky walls and muddy areas influenced by tidal cycles.

Family Bithyniidae Gray, 1857

Genus Bithynia Leach, 1818

3.1.16. Bithynia tentaculata (Linnaeus, 1758)

Aquatic species widely distributed in Europe and throughout much of the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias. It usually lives in the lower-middle course of streams and rivers. It is also found in stagnant water areas and in temporary streams, either on the substrate or among the marshy vegetation, on which it feeds.

Family Hydrobiidae Stimpson, 1865

Genus Alzoniella Giusti & Bodon, 1984

3.1.17. Alzoniella asturica (Boeters & Rolán, 1988)

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. Together with its type locality, the La Fontona fountain [50], it is only found near Grado [51]. A rare species in Asturias believed to be living associated to springs.

3.1.18. Alzoniella cantabrica (Boeters, 1983)

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula that is distributed throughout Cantabria, the Basque Country, the north of León, Burgos, Palencia, and the eastern part of Asturias [51]. Frequent species in the region. Although Boeters [52] does not refer to the habitat of A. cantabrica, it seems to live associated to springs and water currents. In certain localities it lives in sympatry with A. ovetensis or A. montana [51].

3.1.19. Alzoniella camocaensis Rolán & Boeters, 2015

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. It is only known from the vicinity of Camoca in Villaviciosa, being its type locality Fuente Tebia [53]. A rare species in Asturias that lives associated to the spring and is found under stones and among the characteristic reddish sediment of its fountain.

3.1.20. Alzoniella lucensis (Rolán, 1993)

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula that is distributed throughout Galicia, the western part of Asturias and some localities of León [51]. A rare species in Asturias, which tends to live associated to running and clean waters. It is generally found attached to leaf litter, wood and branches [54].

3.1.21. Alzoniella marianae Arconada, Rolán & Boeters, 2007

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula, only known from its type locality Fuente Caliente and nearby areas in Villazón in Salas [51]. Due to its scarce geographical distribution, it can be considered rare in Asturias. It lives associated to the spring [51].

3.1.22. Alzoniella montana (Rolán, 1993)

Peninsular endemism distributed throughout Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque Country and some localities in León [51]. Rare species in Asturias. It can be found in the eastern part of the region. This species lives associated to running and clean waters. Rolán [54] commented that the absence of juvenile individuals in the sampled areas may indicate that their juvenile stages live in areas deeper than the interstitial levels. In certain localities it lives in sympatry with other Alzoniella species [51].

3.1.23. Alzoniella ovetensis (Rolán, 1993)

Peninsular endemism located in Asturias and some localities of León and Cantabria [39,51]. Its type locality is Baselgas in Grado [54]. Frequent species in Asturias. Brodely distributed in the central-eastern zone. This species lives in springs, fountains, and streams of running and clean water. In certain localities it lives in sympatry with A. montana and A. cantabrica [51]. Ojea and Anadón [55] recorded Bythinella brevis (Draparnaud, 1805) in Monte Naranco. However, this species does not seem to be part of the fauna of the Iberian Peninsula [56]. Thus, it is believed the record from Ojea and Anadón [55] corresponds to A. ovetensis, a very abundant species in this area that had not been described at that time.

3.1.24. Alzoniella somiedoensis Rolán, Arconada & Boeters, 2009

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. It is located near Pola de Somiedo from where its type locality La Malva is found [57]. This species is rare and lives under fallen leaves on flooded surfaces. It can also be found on rocks and mosses.

Genus Deganta Arconada & Ramos, 2019

3.1.25. Deganta azarum (Boeters & Rolán, 1988)

Endemic aquatic species to the Iberian Peninsula. It is only known from Asturias and Cantabria [39,58] being its type locality the Fuente La Broquera in Trubia (Oviedo). This fountain was destroyed for road construction [50,58]. A frequent species in the central area of Asturias that lives in springs, streams, washing places and peri-urban channels with clean water. It prefers shady places, so it is easily found living under stones, leaves or submerged tree branches [50]. Curiously, localities where D. azarum is abundant, Alzoniella species are scarce or absent and vice versa [58].

Genus Islamia Radoman, 1973

3.1.26. Islamia ayalga Alonso, Quiñonero-Salgado & Rolán, 2018

Endemic Iberian species. Only known from Asturias, specifically from its type locality the cave of the Caldueñín spring in Llanes [59]. Nothing is known about the ecology and biology of this rare species. It seems to be a stigobiotic species which completes its entire life cycle in underground watercourses.

Genus Mercuria Boeters, 1971

3.1.27. Mercuria tachoensis (Frauenfeld, 1865)

Rolán and Boeters [53] described Alzoniella camocaensis in Fuente Tebia from La Camoca in Villaviciosa. In addition, they commented that there is a species of the genus Mercuria pending description. Although the work remains unpublished, the species that lives in Asturias is Mercuria tachoensis (Jonathan Miller, pers. comm).

Family Moitessieriidae Bourguignat, 1863

Genus Spiralix Boeters, 1972

3.1.28. Spiralix asturica Quiñonero-Salgado, Ruiz-Cobo & Rolán, 2017

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. Only known from Asturias, specifically from its type locality, a small spring near the train tracks on the road to Las Caldas and Fuso from Caces to Trubia (Oviedo) and from the Fuente de los Tres Caños in Priorio, Las Caldas [60]. It is a rare species and nothing is known about its ecology and biology, appearing to be a stigobiotic species. Rolán and Ramos [61] described Paladilhiopsis septentrionalis based on material collected in the provinces of Álava, Vizcaya, Burgos and Cantabria. Rolán and Arconada [62] recorded this species in Asturias. Years later P. septentrionalis was included in the genus Spiralix and the subgenus Burgosia and its distribution was restricted to Álava, Vizcaya and Burgos due to the description of two new species previously confused with S. septentrionalis: S. burgensis for Cantabria and S. asturica for Asturias [60].

3.1.29. Spiralix vetusta Quiñonero-Salgado, Alonso & Rolán, 2018

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. It is only known from Asturias, specifically from its locality type Fuente Vieya (Palaciós) in Lena [63]. Nothing about the ecology and biology of this extremely rare species is known, apart for being a stigobiotic species [63].

Family Tateidae Thiele, 1925

Genus Potamopyrgus Stimpson, 1865

3.1.30. Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843)

This aquatic species lives in the rivers and lagoons of New Zealand [64]. Potamopyrgus antipodarum has been introduced in several countries of Europe, Asia and North America [64]. It is widely distributed throughout the Iberian Peninsula and is a very common species in Asturias. It lives in different aquatic environments, from fountains, troughs, and springs, to running waters and river mouths with brackish water, where it buries itself in the substrate. This species is listed in the Spanish Catalogue of Invasive Exotic Species (Real Decreto 630/2013, from 2 of August).

Order UNASIGNED

Superfamily Lymnaeoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Lymnaeidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Galba Schrank, 1803

3.1.31. Galba truncatula (O.F. Müller, 1774)

Aquatic species widely distributed throughout Europe. It can be found in most of the Iberian Peninsula. A frequent species in Asturias that lives in temporary ponds, humid plains and walls, swampy forests, fountains and springs.

Genus Lymnaea Lamarck, 1799

3.1.32. Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Aquatic species widely distributed throughout Europe, Asia and North Africa. In the Iberian Peninsula it is only known from Catalonia, Castilla y León and Andalucía [31]. This species lives in stagnant waters, rivers and pools. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. This snail was found alive in a peatbog at Villanueva de Oscos in 2018.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Villanueva de Oscos pond: three specimens. 20-VIII-2018. (29TPH61559569).

Genus Omphiscola Rafinesque, 1819

3.1.33. Omphiscola glabra (O. F. Müller, 1774)

A poorly known aquatic species widely distributed across Europe (from Scandinavia to northern Spain). In the Iberian Peninsula is a quite rare species, only known from some collections from Euskadi and Galicia [65]. Here, we present the first published record of this species for Asturias. This snail was found in a temporary pond of a recreational area at the base of Sierra del Aramo and only one live specimen could be examined in the field. The pond was surrounded by abundant aquatic vegetation such Juncus spp. and mint. The specimen was found adhered to a submerged log in a quite muddy substrate. Although much sampling in the mud was made, no more snails were found. All the ecological remarks fit with recent works [65] with the exception of the height (range 400–500 m. vs. our own observation at 888 m. high).

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Temporal pound in Aviles: four specimens. BOS Collection. V-1979 (Coordinates not indicated). Recreational area of La Peral, Pola de Lena (Lena): one live specimen. 17-IX-2020, 888 m. (30TTN64998266).

Family Physidae Fitzinger, 1833

Genus Physella Haldeman, 1842

3.1.34. Physella acuta (Draparnaud, 1805)

This aquatic species inhabits the rivers and lagoons of North America where it coexists with other species of the same family [66]. Currently this species is found in Europe, Africa, South Asia, Australia, and Japan [66]. In the Iberian Peninsula it is distributed throughout all the territory. Physella acuta is frequent in Asturias, where it inhabits all kinds of waters such as lakes, temporary ponds, drinking troughs and rivers, ditches and fountains. It is believed that its introduction in Europe occurred through the cotton trade in the 18th century [67], and it was later dispersed throughout the territory due to aquatic plants linked to aquarium and pets trade [68]. This highly invasive species does not appear in the Spanish Catalogue of Invasive Alien Species (Real Decreto 630/2013, from 2 of August).

Genus Radix Montfort, 1810

3.1.35. Radix auricularia (Linnaeus, 1758)

Species distributed throughout central Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula is distributed along the North. Only one Asturian record is known [31], making it a rare species in Asturias. It usually lives associated with rivers where it is common to find among stones on the riversides.

3.1.36. Radix labiata (Rossmässler, 1835)

Species distributed throughout Europe. Only known from León and Huesca in the Iberian Peninsula [69]. In the past, there was some confusion due to the use of Radix peregra (O.F. Müller, 1774) to refer to R. labiata, when the former is a junior synonym of R. balthica. Therefore, Iberian records must be reviewed [69]. A rare species that lives in different types of water: rivers, fountains and springs. Thus, although it is quite probable this species occurs in Asturias, its presence in the territory needs confirmation.

Genus Ampullaceana Servain, 1882

3.1.37. Ampullaceana balthica (Linnaeus, 1758)

Species distributed throughout Europe and the whole the Iberian Peninsula. This species was recorded as Lymnaea (Radix) limosa (Linnaeus, 1758) in Piedras Blancas and Santa María del Mar (Castrillón) [32]. Common species that lives in different types of water courses.

Genus Stagnicola Jeffreys, 1830

3.1.38. Stagnicola cf. palustris (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species distributed throughout much of Europe and the Iberian Peninsula. It usually habits in stagnant waters with abundant vegetation, from small swamps to lagoons and lakes, even tolerates brackish water and temporary desiccations. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. The status of this species in Asturias is not clear, it could be part of the native fauna since the species is distributed throughout much of the Iberian Peninsula. However, the material here recorded belongs to the collection of molluscs of the University of Oviedo (BOS) and all the material was found in anthropized areas where it has been able to be introduced.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Silvota industrial estate (Siero): one specimen. BOS Collection. 29-VII-1980 (coordinates not indicated). Spring in Monte Naranco (Oviedo): one specimen. BOS Collection. 07-III-1981 (coordinates not indicated). Spring in Lugones (Siero): one specimen. BOS Collection. 28-IV-1983 (coordinates not indicated).

Family Planorbidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Ancylus O. F. Müller, 1773

3.1.39. Ancylus fluviatilis O.F. Müller, 1774

Aquatic species widely distributed throughout Europe except for its northern fringe. It is broadly distributed throughout the Iberian Peninsula. It is a common species in Asturias that lives in rivers, streams, lakes, and sources of clean and oxygenated water. It is generally easy to locate on stones scraping the algae on which it feeds.

Genus Gyraulus Charpentier, 1837

3.1.40. Gyraulus laevis (Alder, 1838)

Aquatic species widely distributed throughout Europe. It is widely distributed in the Iberian Peninsula and is found in most communities. It is a rare species in Asturias. Since the record from El Llano in Llordón (Cangas de Onís) [70], this species has not been found again. Its typical habitat is the edges of lakes and swamps with stagnant, clean and shallow waters.

Genus Planorbella Haldeman, 1843

3.1.41. Planorbella duryi (Wetherby, 1879)

Aquatic species that inhabits waterways in Florida (North America). It has been established on numerous occasions outside its native range including much America, Jamaica and Cuba, the Middle East, Russia, Australia, Hawaii and Europe [71,72,73]. In the Iberian Peninsula, it has been recorded in the city of Barcelona, Ebro River Basin, Tarragona [73], Elche, Alicante [74], Castellón, Valencia, Mallorca [73] and the Canary Islands [49]. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. These snails were found alive in highly anthropized areas, so the probable pathway of introduction of this species is linked to ornament aquatic plants and pet trade.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Nora River, near Colloto (Oviedo): four adults and nine juvenile specimens. VII-2013. (30TTP74080669). Nalón River (El Entrego, San Martín del Rey Aurelio): five specimens. 2017 (30TTN85699627). San Andrés de los Tacones reservoir (Gijón): five specimens. 2018. (30TTP77382018). Spring in Monte Naranco at the beginning of Pista Finlandesa (Oviedo): one juvenile specimen. 11-XI-2019. (30TTP68060658).

Order Ellobidae L. Pfeiffer, 1854 (1822)

Superfamily Ellobioidea L. Pfeiffer, 1854 (1822)

Family Ellobiidae L. Pfeiffer, 1854 (1822)

Genus Ovatella Bivona-Bernardi, 1832

3.1.42. Ovatella aequalis (Lowe, 1832)

Species distributed along the European Atlantic coasts. Regarding its distribution in the Iberian Peninsula, Bank et al. [75] considered this species as a Macaronesian endemism commenting that the previous records of O. aequalis could correspond to a misidentification with O. firminii (Payraudeau, 1827). However, Alonso et al. [76] provide the first records of O. aequalis outside the Macaronesian region, specifically for the coasts of Cantabria and Asturias. This rare species lives in Asturias in rocks linked to estuaries.

Genus Pseudomelampus Pallary, 1900

3.1.43. Pseudomelampus exiguus (Lowe, 1832)

Species distributed along the European Atlantic coast. It is widely distributed in the Cantabrian and Atlantic coasts of the Iberian Peninsula. A rare species in Asturias [76]. It can be found in coastal rocky areas, hidden under stones subjected to a strong saline influence.

Genus Myosotella Monterosato, 1906

3.1.44. Myosotella myosotis (Draparnaud, 1801)

Species of Euro-Mediterranean distribution that is distributed throughout good part of the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula. A frequent species in Asturias [76]. It is found in rocks linked to estuaries. It can also be found among halophilic plants and under wood and stones in humid dune areas, always subject to a certain saline influence.

3.1.45. Myosotella denticulata (Montagu, 1803)

Species distributed along the European Atlantic coast. It is located on the Cantabrian and Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula. Certain authors consider this species as a synonymous of M. myosotis and may constitute a complex of species [76]. Frequent in the study area living in the crevices of the coastal rocky areas [76].

Genus Leucophytia Winckworth, 1949

3.1.46. Leucophytia bidentata (Montagu, 1808)

Species distributed along the European Atlantic coast and the western Mediterranean basin. In the Iberian Peninsula it is present on the Cantabrian and Atlantic coast. It can also be found scattered along the Mediterranean coasts and the Balearic Islands. Frequent species in Asturias [76]. Its habitat is very similar to that of other members of the Ellobiidae family.

Genus Carychium O. F. Müller, 1773

3.1.47. Carychium minimum O.F. Müller, 1774

Eurosiberian species distributed throughout a good part of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly linked to the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Cantabrian fringes. A rare species in Asturias. There is only one record from the Integral Reserve of Muniellos [28]. This species prefers humid microenvironments under rocks, logs, and leaf litter.

3.1.48. Carychium tridentatum (Risso, 1826)

Eurosiberian species found throughout the north of the Iberian Peninsula, with other isolated Iberian records. Frequent species in Asturias, whose microhabitat is identical to its sister species C. minimum.

Genus Zospeum Bourguignat, 1856

3.1.49. Zospeum gittenbergeri Jochum, Prieto & De Winter, 2019

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. It is only known from its type locality, the cave Puente de Inguanzo in Cabrales (Asturias) [77]. This species lives inside caves. However, the authors do not refer to the type of habitat where Z. gittenbergeri can be found, so more studies are necessary to clarify the data on its biology, ecology and distribution.

3.1.50. Zospeum percostulatum Alonso, Prieto, Quiñonero-Salgado & Rolán, 2018

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. In Asturias is known from two caves, located geographically very close to each other, in the lower part of the Sierra of Cuera [78]. Its type locality is the cave La Herrería (La Pereda) in Llanes [78]. This species lives inside caves, on damp walls covered with a clay film. It has been found in sympatry with Z. cf. praetermissum [78].

3.1.51. Zospeum praetermissum Jochum, Prieto & De Winter, 2019

Endemic species to the Iberian Peninsula. Only known from Asturias, from its type locality the Puente de Inguanzo cave in Cabrales [77], previouly recorded as Zospeum schaufussi Frauenfeld, 1982. This species lives inside caves, however, the authors do not refer to the type of habitat where this species can be found, so more studies are necessary to clarify its biology, ecology and distribution.

Order Stylommatophora A. Schmidt, 1855

Superfamily Achatinoidea Swainson, 1840

Family Achatinidae Swainson, 1840

Genus Rumina Risso, 1826

3.1.52. Rumina decollata (Linnaeus, 1758)

Species distributed throughout the European Mediterranean coast and north Africa. It is a common Mediterranean species in the Iberian Peninsula being absent in the northwest. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. Some live adults and juveniles of this snail were found in the dune system of San Juan de Nieva in Avilés. The area where this species was found is near a car park, so the introduction of this species in Asturias is quite probably linked to tourism. Since it has been found in a highly crowded area, it has been able toculd have been introduced passively attached to vehicles.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: dune system of San Juan de Nieva (Avilés) near the parking area: seven specimens. 8-VIII-2012. (30TTP62713027).

Family Ferussaciidae Bourguignat, 1883

Genus Cecilioides A. Férussac, 1814

3.1.53. Cecilioides acicula (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species with a circum-Mediterranean distribution, broadly distributed in much of the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias. It lives buried, sometimes at great depth. However, it also lives in the humid microhabitat located under stones and in rock crevices with abundant organic matter.

Superfamily Papillodermatoidea Wiktor, R. Martin & Castillejo, 1990

Family Papillodermatidae Wiktor, R. Martin & Castillejo, 1990

Genus Papilloderma Wiktor, R. Martin & Castillejo, 1990

3.1.54. Papilloderma altonagai Wiktor, Martín & Castillejo, 1990

It is an endemic Iberian species. The only records are those used in its description (Sanctuary of Covadonga in Asturias and Puerto de las Alisas in Cantabria) and one from Alejandro Pérez-Ferrer through a citizen science platform [79]. Its habitat includes high mountain meadows, anthropized areas and ruderal environments [80]. Slug shells discovered at the entrance to the caves (without living specimens) [79] remarks the importance to study the real distribution of this unknown species or other that remains undefined. It could be underground and predatory of worms [79,80].

Superfamily Punctoidea Morse, 1864

Family Punctidae Morse, 1864

Genus Paralaoma Iredale, 1913

3.1.55. Paralaoma servilis (Shuttleworth, 1852)

Species distributed throughout the Mediterranean part of Europe, including throughout a good part of the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias. It is well adapted to anthropized areas, where it lives between cracks in stone walls with abundant vegetation. It also frequents forests and riverbanks, where it is found on the vegetation, under stones or leaf litter.

Genus Punctum Morse, 1864

3.1.56. Punctum pygmaeum (Draparnaud, 1801)

Holarctic species distributed throughout a large part of the Iberian Peninsula with lack of records in the central zone. Punctum pygmaeum is common in Asturias and lives associated with banks and grasslands near watercourses, occupying high humidity microhabitats.

Family Discidae Thiele, 1931 (1866)

Genus Discus Fitzinger, 1833

3.1.57. Discus rotundatus (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species widely distributed throughout Europe. Common in the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula. Amply distributed species in Asturias that lives in all kinds of environments such as forests, stone walls, gardens and meadows. Its most common microhabitats are those located under stones, logs and mosses.

Family Helicodiscidae Pilsbry, 1927

Genus Lucilla R. T. Lowe, 1852

3.1.58. Lucilla scintilla (Lowe, 1852)

Species distributed throughout North America and several countries in Europe. There is an open debate about its status as an introduced species in Europe [81]. In the Iberian Peninsula is only known from Asturias and Cantabria [82]. This species is considered rare in Asturias since only a few records from the eastern part of the territory are known [82]. Not much is known about the biology of this species. Although it is known that generally exhibits underground habits it could frequent flooded areas thanks to its high resistance to immersion in water [83].

3.1.59. Lucilla singleyana (Pilsbry, 1890)

Species distributed throughout North America and a large part of Europe and Africa. Like in the case of L. scintilla, there is an open debate about its status as an introduced species in Europe [81]. Patchily distributed in the Iberian Peninsula. In Asturias it is rare, with only a few records in the western coast of Asturias [70]. It has habits that are practically identical to its sister species L. scintilla [82]. The recent appearance of L. scintilla in Asturias [79], has made the presence of L. singleyana in the region remain in doubt, and it is possible that the records provided by Hermida [70] correspond to misidentifications.

Superfamily Testacelloidea Gray, 1840

Family Testacellidae Gray, 1840

Genus Testacella Lamarck, 1819

3.1.60. Testacella haliotidea Draparnaud, 1801

Broadly distributed species in the Atlantic coast and the European Mediterranean. In the Iberian Peninsula it is distributed from Asturias to Catalonia, as well as the provinces neighboring the Mediterranean coast. Asturias records are scarce and fragmented, probably due to the underground habitat of this species that makes it difficult to detect. It is a predatory species of worms. A review of Testacella species in Asturias is provided in Robla and Alonso [11].

3.1.61. Testacella maugei Férussac, 1819

Broadly distributed species in the European Atlantic. In the Iberian Peninsula it is distributed from Navarra to Galicia, continues along the Atlantic coast to Gibraltar and reaches Valencia in the Mediterranean. It is the most easily identifiable Testacella due to its large shell compared to the rest Iberian species. Same biology to other members of Testacellidae. It seems a widely distributed species in Asturian territory based on the location of slug shells [11].

3.1.62. Testacella scutulum G. B. Sowerby I, 1821

This species is distributed through the western Mediterranean, easily found in the entire Iberian Mediterranean coastal area. In Asturias, no living specimens were located, but shells were found [11]. The lack of more exhaustive studies on this family of slugs and its apparent Mediterranean distribution, allow us to think whether the found slug shells [11] could have been the result of several introductions. However, more studies are needed to clarify its status in Asturias as native or introduced.

Superfamily Succineoidea Beck, 1837

Family Succineidae Beck, 1837

Genus Oxyloma Westerlund, 1885

3.1.63. Oxyloma elegans (Risso, 1826)

Cosmopolitan Holarctic species, broadly distributed in the Iberian Peninsula. Oxyloma elegans is an amphibian aquatic species very common in Asturias. It lives on the banks of rivers, streams, water courses, canals, lagoons, wetlands and fountains, generally attached to the riverside vegetation.

Genus Quickella C.R. Boettger, 1939

3.1.64. Quickella arenaria (Potiez & Michaud, 1838)

Species distributed throughout Western Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula there are only a few records from the Arán Valley (Lérida), Castellón, Teruel and Asturias. In Asturias it is a very rare species, only known from Sta. María del Puerto (Santoña) and Tielve (Cabrales) [84]. It lives in humid areas near watercourses and even in high mountains.

Superfamily Pupilloidea W. Turton, 1831

Family Pupillidae W. Turton, 1831

Genus Pupilla J. Fleming, 1828

3.1.65. Pupilla muscorum (Linnaeus, 1758)

Holarctic species distributed throughout the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula and in some isolated areas in the south. Pupilla muscorum is rare in Asturias and it is highly chalky and hygrophilous. It lives mainly associated with banks and meadows near watercourses among other habitats.

Family Cochlicopidae Pilsbry, 1900 (1879)

Genus Cochlicopa A. Férussac, 1821

3.1.66. Cochlicopa lubrica (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Holarctic species widely distributed in the Iberian Peninsula. This species is common in Asturias and lives in all types of environments: banks, forests, crops, anthropized areas, usually in humid microhabitats under stones, logs, and leaf litter. It is usually found in sympatry with C. lubricella, from which it is difficult to separate due to its great morphological similarity [85]. Hermida [70] assigned the record of Zua subcilindrica (Linnaeus, 1767) registered by Bofill and Haas [32] in Covadonga, Las Caldas (Oviedo) and Sta. María del Mar (Castrillón) to Cochlicopa lubrica.

3.1.67. Cochlicopa lubricella (Porro, 1838)

Holarctic species, somewhat less distributed by the Iberian Peninsula than C. lubrica but distributed throughout the same regions. Frequent species in Asturias with identical habitat to C. lubrica. Both species have a great morphological similarity [85].

Family Enidae B. B. Woodward, 1903 (1880)

Genus Merdigera Held, 1838

3.1.68. Merdigera obscura (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Widely distributed species in North Africa and southern Europe, occurring in a good part of the Iberian Peninsula. Common species in Asturias well adapted to anthropized areas, easily found in walls and leaf litter.

Genus Jaminia Risso, 1826

3.1.69. Jaminia quadridens (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Broadly distributed in southern Europe and the Iberian Peninsula. This is a thermophilic species. Not yet recorded from Asturias, it has been found in a few localities, in dry, south oriented rocky slopes with shrubs (Alonso and Raven, in press).

Family Lauriidae Steenberg, 1925

Genus Lauria Gray, 1840

3.1.70. Lauria cylindracea (Da Costa, 1778)

Species distributed throughout Africa, Asia and Europe. It is distributed throughout practically the entire Iberian Peninsula, being quite frequent in Asturias. It lives in all kinds of environments, particularly in anthropized areas and stone walls. It usually forms enormous colonies under the rocks.

3.1.71. Lauria sempronii (Charpentier, 1837)

Species distributed throughout the European Mediterranean and Atlantic fringe. It is a rare species in the Iberian Peninsula limited to a small fraction of the Cantabrian region. Very rare species in Asturias, since only one record is known in Campo de Caso [86]. It seems to live in limestone soils and wall cavities.

Genus Leiostyla R. T. Lowe, 1852

3.1.72. Leiostyla anglica (Férussac, 1821)

Species widely distributed across the European Atlantic coast. In the Iberian Peninsula it is distributed from the northwest to the south of Portugal with some records towards the Mediterranean area. It is a very rare species in Asturias, only known from an isolated record in the vicinity of Trubia and Proaza [87]. It is typical from humid and shady areas such as forests and swamps.

Family Pyramidulidae Kennard & B. B. Woodward, 1914

Genus Pyramidula Fitzinger, 1833

3.1.73. Pyramidula rupestris (Draparnaud, 1801)

Species distributed throughout Asia, Africa and central and southern Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula is found in the northwest part. It is rare in Asturias and is limited to rocks and limestone walls. This species prefers crevices where humid microhabitats are easily formed. It feeds mainly on lichens.

3.1.74. Pyramidula umbilicata (Montagu, 1803)

Species distributed throughout Western Europe. It is found in the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula. Its typical habitat is very similar to P. rupestris although it can also be found frequently on stone walls. They are very active in humid walls.

Family Valloniidae Morse, 1864

Genus Vallonia Risso, 1826

3.1.75. Vallonia costata (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Holarctic species broadly distributed in the Iberian Peninsula. Vallonia costata is frequent in Asturias and lives in a great diversity of environments that include humid places (forests and grasslands), where it is found linked to leaf litter and wood. It is also not uncommon on drier calcareous substrates. Easily observed in sympatry with V. pulchella.

3.1.76. Vallonia excentrica Sterki, 1893

Holarctic species with patchy distribution in the Iberian Peninsula. Rare species in Asturias, only recorded in several isolated localities [88]. It inhabits calcareous soils, coastal areas and meadows. The lack of new records of this species in Asturias, together with its similar appearance to its sister species V. pulchella, makes us think that the material recorded by Altonaga et al. [88] corresponds to a misidentification. However, more studies are needed to clarify the presence of this species in Asturias.

3.1.77. Vallonia pulchella (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Holartic species with same distribution as V. costata in the Iberian Peninsula. Frequent species in Asturias that shares the same type of habitats as V. costata.

Genus Acanthinula H. Beck, 1847

3.1.78. Acanthinula aculeata (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species of western Palearctic distribution that occupies a good part of the Iberian Peninsula. Quite a rare species in Asturias. It is distributed in very humid areas such as forests, bushes and riverbanks, generally living among leaf litter.

Family Vertiginidae Fitzinger, 1833

Genus Vertigo O. F. Müller, 1773

3.1.79. Vertigo antivertigo (Draparnaud, 1801)

Species amply distributed throughout Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula it is limited to the north-northeast region. Rare species in Asturias, where only one record from near the Lago Enol (Covadonga) is known [89]. It is a typical species of humid and swampy areas where it can be found among the mosses and leaf litter on which it feeds.

3.1.80. Vertigo pusilla O. F. Müller, 1774

Species distributed throughout the Central Europe and Asia, with isolated records in the Iberian Peninsula (Catalonia, Castellón and Asturias). It can be considered very rare in Asturias, since only one record from Cangas de Narcea is known [89]. Its typical habitat is associated with fountains and springs living among stones, wood and vegetation.

3.1.81. Vertigo pygmaea (Draparnaud, 1801)

Holarctic species broadly distributed throughout the north of the Iberian Peninsula, the Portuguese coast and some areas of the Mediterranean. Frequent species in Asturias. Vertigo pygmaea is typical in moist environments. However, it can also be found in calcareous walls.

3.1.82. Vertigo substriata (Jeffreys, 1833)

Species distributed throughout central and northern Europe, with isolated records in the Iberian Peninsula limited to Andorra, the Pyrenees, Sierra Nevada (Granada) and Asturias. Very rare species in Asturias with a single record near the town of Noriega [90].

Superfamily Clausilioidea J. E. Gray, 1855

Family Clausiliidae J. E. Gray, 1855

Genus Clausilia Draparnaud, 1805

3.1.83. Clausilia bidentata abietina Dupuy, 1849

Species distributed throughout France and the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula. It is a very common species in Asturias. Typical of humid microenvironments. It is normally found attached to stones and calcareous walls, although it is also found under wood and stones. It is found from the coast to mountain areas. As a highly variable species, it has been historically confused with several subspecies of Clausilia rugosa [3]. Therefore, the old records of Clausilia rugosa Draparnaud, 1801 registered by Hidalgo [91] and Clausilia (Kuzmicia) rugosa Draparnaud, 1801 from Bofill and Haas [32] are surely misidentifications and probably correspond C. bidentata abietina.

Genus Balea Gray, 1824

3.1.84. Balea heydeni Maltzan, 1881

Species distributed throughout the Atlantic European coastal areas. Limited to the northwest part of the Iberian Peninsula. It is an uncommon species in Asturias associated with humid environments such as riverbanks and fountains. Historically this species has been confused with its sister species B. perversa by several authors. However, after recent reviews it is clarified the distribution of these two sister species in the Peninsula, B. heydeni was relegated to the northwest of the Peninsula and B. perversa to the northeast [92,93]. A recent study on this species in Cantabria seems to confirm because B. perversa was not found in any of the sampled localities [39,94]. After the mentioned works, B. perversa is recorded in the Integral Reserve of Muniellos in Asturias [28]. However, after reviewing the material, it has turned out to correspond to a misidentification with adults of B. heydeni and juveniles of Clausilia bidentata abietina.

Superfamily Arionoidea Gray, 1841

Family Arionidae Gray, 1840

Genus Arion A. Férussac, 1819

3.1.85. Arion ater (Linnaeus, 1758)

It is a widely distributed European species. This slug occurs in the north of the Iberian Peninsula and is perhaps a common species in Asturias. Historically, the Arion ater complex (usually denominated Arion ater s. l.) have comprised two different morphological forms: Arion ater and Arion rufus, without consensus about their status [95]. Both species have been considered different subspecies [96,97], ecotypes [98] or species/clades [99,100]. Due to its external resemblance, most authors confused both species, so the records of Arion ater must be revaluated in Asturias. Recently, with new genetic approaches, Peláez et al. [101] stablished the members of Arion complex as separated species. Arion ater, among its great external variability, tends to be a large black species usually found in gardens, meadows, orchards and other ruderal and anthropized areas. It can be found in mountainous regions and forests too. It is an important pest species.

3.1.86. Arion rufus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Records of Arion rufus from Arion ater complex needs re-examinations and confirmations after new studies [101]. Tentatively, with the same European, Iberian and Asturian distribution of A. ater. Arion rufus frequents gardens, orchards and other anthropized areas as an important pest for agriculture.

3.1.87. Arion hispanicus Simroth, 1886

Endemic slug distributed across the northwest and central part of the Iberian Peninsula. Asturias is the northern limit of its distribution. It seems to be a species that prefers humid meadows [80]. This slug is poorly known.

3.1.88. Arion hortensis Férussac, 1819

This slug species is distributed in southwest Europe with several introductions in other parts of the continent. In the Iberian Peninsula is limited to the north. Castillejo [80,102] and Cadevall and Orozco [3] created distribution maps including Asturias but no specimens were collected from there or studied. Various specimens of Arion that fitted with the external appearance of A. hortensis were observed under a stone in a meadow with some bushes in December of 2019 in Monte Naranco (Oviedo). However, slugs were not collected, so the presence of this species in Asturias, although quite probable, needs confirmation.

3.1.89. Arion intermedius Normand, 1852

Arion species native to Western Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula it is widely distributed, only missing in the south. It is, with the members of A. ater complex, the other most common species in Asturias, frequently found in meadows, orchards, gardens and forests.

3.1.90. Arion lusitanicus auct. non Mabille, 1868/Arion vulgaris Moquin-Tandon, 1855

Under the denomination of Arion lusitanicus/Arion vulgaris, two different slugs were included without a clear specific status. Arion lusitanicus is supposed to be a microendemic slug to Portugal [3,80,103] quite different from A. vulgaris. The separation of both species was confirmed thanks to molecular analysis [95,98]. On the other hand, A. vulgaris, commonly named ‘Spanish slug’, is a wide distributed species with a high expansive and invasive character [9,104]. Although its origin is not clear, it could be native from Central Europe [104,105]. Thus, all the records of this species in Asturias must be reviewed [25,70,80,88,102] because only A. lusitanicus was apparently recorded. Asturian records of A. lusitanicus probably must be reassigned to A. vulgaris, a slug ranked among the hundred must invasive species in Europe [104].

Género Geomalacus Allman, 1843

3.1.91. Geomalacus maculosus Allman, 1843

Endemism is limited to the northern Iberian Peninsula and Ireland [106,107]. It is a nocturnal species that spends most of the day hidden in crevices or under stones and logs. It occurs in very humid microhabitats of well-preserved wooded areas (oak groves, chestnuts and beech forests). It also has a mountain morph (with different color from the common morph) and can appear in anthropized areas such as stone walls covered by moss [80]. It is the only Iberian slug under some type of protection. It is protected under Appendix A of the Bern Convention and is included in Annex IV (a) of the EU Habitats Directive 92/43 [106]. It is catalogued as Vulnerable (VU B1ab(I, ii, iii)) in the Iberian Peninsula red book of invertebrates [108]. It is a common species in Asturias but difficult to detect due to its nocturnal habits.

Superfamily Limacoidea Lamarck, 1801

Family Limacidae Lamarck, 1801

Genus Limacus Lehmann, 1864

3.1.92. Limacus flavus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Species patchily distributed, mainly occurring in the Mediterranean region. In the Iberian Peninsula it is a broadly distributed species lacking in some regions. In Asturias it is a very common species that appears frequently in orchards, gardens and anthropic areas. It presents ruderal habits, although it also frequents forests and other natural habitats. Limacus maculatus (Kaleniczenko, 1851) is a similar species that have not be found in Iberian territory yet. Due to its external resemblance to L. flavus and its status of introduced in other regions [80], it is not rare that could be found in Asturias in the future.

Genus Ambigolimax Pollonera, 1887

3.1.93. Ambigolimax valentianus (Férussac, 1822)

Amply distributed species throughout all the Iberian Peninsula, introduced in north and central parts of Europe. It is a common species in Asturias with anthropic trends, frequent in ruderal habitats and gardens [80]. It can be found in cities, urban parks and walls with crevices and mosses. It also occurred in natural habitats. Due to its relative abundance, it can become an agricultural pest.

Género Lehmannia Heynemann, 1862

3.1.94. Lehmannia marginata (O.F. Müller, 1774)

Common species in central and western Europe. It is distributed in the northern Iberian Peninsula. Common species in Asturias linked to ruderal and anthropized areas. However, it can also be found in forests developing arboreal trends [80]. It is considered a species with a great variability [109]. One morphological form treated as Lehmannia marginata f. rupicola, is considered as a separated species by some authors [3,110]. Lehmannia rupicola Lesson & Pollonera, 1882 is not still found in Asturias, but it is a species that quite probably will be found in future samplings.

Género Limax Linnaeus, 1758

3.1.95. Limax maximus Linnaeus, 1758

Widely distributed species throughout Europe that occurs in the northern Iberian Peninsula, as well as Portugal. It has specific records in southern Spain [111], probably due to introductions. Common species, linked to altered environments such as orchards, walls and other habitats under man influence. It is a nocturnal species that is easily observed on the cooler and rainy nights. However, during the day it is quite difficult to find even under stones or logs in which it hides.

Family Agriolimacidae H. Wagner, 1935

Genus Deroceras Rafinesque, 1820

3.1.96. Deroceras agreste (Linnaeus, 1758)

Broadly distributed species in the western Palearctic. In the Iberian Peninsula it is common in the northern, although it has also been found in certain areas of the Mediterranean. It is an abundant species in Asturias, common in mountainous areas, both in meadows and forests [80].

3.1.97. Deroceras panormitanum (Lessona & Pollonera, 1882)/D. invadens Reise, Hutchinson, Schunack & Schlitt, 2011

This species was believed to be distributed along the European Atlantic coast and some areas of the Mediterranean region. In the Iberian Peninsula it had been recorded in the Basque Country, Galicia, León, Cantabria, Valencia and Portugal. In fact, Castillejo [80] drew distribution maps of this species that included Asturias, even though no Asturian specimen had been studied at the time. The only Asturian record of D. panormitanum is one from Muniellos [28]. Cadevall and Orozco [3] did not include this reference in their book, but they included Asturias as the region where D. panormitanum occurred. Exhaustive analyses and studies have determined that D. panormitanum is a species limited to Sicily and Malta [112] and all the records of this species from the rest of the world need revision. It could actually correspond to Deroceras invandens [112,113]. Therefore, D. panormitanum does not occur in Asturias. The specimen of D. panormitanum from the Integral Reserve of Muniellos could not be revised due to its bad conservation state. However, this record probably belongs to D. invadens. More studies are needed to clarify its status in Asturias, but it is probably an extended anthropical species introduced from Italy [114].

3.1.98. Deroceras ercinae De Winter, 1985

Iberian endemism exclusively limited to the Cantabrian region. Species distributed in a variety of environments, but usually preferring calcareous soils [80]. This species is quite unknown and since its description and some later works [115] that contribute with new records for Galicia, it has not been re-studied.

3.1.99. Deroceras laeve (O.F. Müller, 1774)

Holarctic species that in the Iberian Peninsula is distributed in the north, lacking in southern and central regions. It is a species linked to very moist microenvironments. In Asturias it is preferably found in areas close to rivers [80] among other habitats.

3.1.100. Deroceras lombricoides (Morelet, 1845)

Peninsular endemism distributed in northwest Spain and that extends to the south of Portugal. Its typical habitat is pine forests inhabiting the needles layer, but it is also found in other habitats [80] Like D. ercinae, it is a little studied species that, since the works of Castillejo [80] and Pesqueira et al. [115] has not been restudied and its distribution and biology in the Asturian region is still an enigma.

3.1.101. Deroceras reticulatum (O.F. Müller, 1774)

The most abundant Iberian species of Deroceras widely distributed across Europe. It is a very common species in Asturias, particularly in anthropized areas, gardens and crops. It is an important pest.

3.1.102. Deroceras rodnae Grossu & Lupu, 1965

A species restricted to certain areas of central and eastern Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula is limited to the northern section. It is a typically forest species that frequents forest edging on wet nights, although it can also be found in leaf litter or dead wood [80]. It is a common species in Asturias.

Genus Furcopenis Castillejo & Wiktor, 1983

3.1.103. Furcopenis darioi Castillejo & Wiktor, 1983

Iberian endemism, only found in a small region of Galicia, the Sil Valley (León) and the south of Asturias [80]. It is typical from chestnut forests, holm oaks and broom scrub [80] However, like other species such as D. ercinae and D. lombricoides it is a species quite unknown.

Family Vitrinidae Fitzinger, 1833

Genus Vitrina Draparnaud, 1801

3.1.104. Vitrina pellucida (O. F. Müller, 1774)

A Holarctic species widely distributed in the Iberian Peninsula, except the southwestern area. In Asturias, this species prefers humid environments such river meadows and forests with logs, trunks and leaf litter.

Superfamily Gastrodontoidea Tryon, 1866

Family Gastrodontidae Tryon, 1866

Genus Aegopinella Lindholm, 1927

3.1.105. Aegopinella nitidula (Draparnaud, 1805)

Species distributed throughout Western Europe that in the Iberian Peninsula is limited to the northern part. It is a frequent species in Asturias that lives in forests and edges of orchards.

3.1.106. Aegopinella pura (Alder, 1830)

Species distributed throughout central Europe. In the Iberian territory it is limited to the northeast region with some records in certain provinces of Portugal. It is not a common species in Asturias, which tends to select relatively dry and exposed environments, being easy to find under stones.

Genus Zonitoides Lehmann, 1862

3.1.107. Zonitoides nitidus (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Holarctic species distributed throughout much of the Iberian Peninsula. Rare species in Asturias, there is only evidence of an isolated record in Cangas de Onís [70] and it has not been located again. In other parts of the Peninsula where it is abundant, it lives associated with watercourses such as sources and riversides, generally among the vegetation or leaf litter.

Family Oxychilidae Hesse, 1927 (1879)

Genus Oxychilus Fitzinger, 1833

3.1.108. Oxychilus alliarius (J. S. Miller, 1822)

Western European species. In the Iberian Peninsula is distributed throughout the northwest region and other several localities (Salamanca, Ávila and Tarragona). Rare species in Asturias that lives in forests among the leaf litter.

3.1.109. Oxychilus anjana Altonaga, 1986

Endemic Iberian species with a limited distribution to Cantabria and western Asturias. This species is rare in Asturias because there is only one known record in Trescares from Peñamellera Alta [116], so little can be said about its habitat in Asturias. It could live in riverside forests with organic matter.

3.1.110. Oxychilus cellarius (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species distributed throughout western and central Europe, widespread in the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula. It is one of the most frequent species of Oxychillus in Asturias. This species lives in riverside forests and gardens. It can adapt to certain degree of anthropization.

3.1.111. Oxychilus draparnaudi (H. Beck, 1837)

Species distributed throughout the western Mediterranean and Europe. Well widespread over the entire Iberian Peninsula. It is one of the most frequent species in Asturias with O. cellarius. It lives in the same habitat as O. cellarius. In front of the snails of the region it is partially carnivorous and feeds on worms and snails.

3.1.112. Oxychilus navarricus (Bourguignat, 1870)

Endemism to the Cantabrian-Pyrenean region in the northern Iberian Peninsula. It is a frequent species in Asturias that usually lives in humid beech trees forest among the leaf litter. This species has been recorded in Asturias many times under the name of O. helveticus (Blum, 1881) (= O. navarricus) [70,88,117]. Bech [118] registered Oxychilus (Oxychilus) cfr. psaturus Bourguignat, 1864 in Covadonga and later, Altonaga [117] assigned this record to O. helveticus (= O. navarricus).

Genus Perpolita H. B. Baker, 1928

3.1.113. Perpolita hammonis (Strøm, 1765)

Species distributed throughout much of central and northern Europe. It lives in the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula. It is a common species in Asturias that lives in deciduous forests and gardens, among leaf litter and mosses.

Genus Retinella P. Fischer, 1877

3.1.114. Retinella incerta (Draparnaud, 1805)

Cantabrian-Pyrenean endemism distributed throughout the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula. There are only two records belonging to a establish population detected in 2015 in Baldornón (Gijón) and an empty shell found in El Monte in Pico San Martín from Siero [46]. Its origin is uncertain, and it seems introduced through ornamental plants [46].

Genus Morlina A. J. Wagner, 1914

3.1.115. Morlina glabra (Rossmässler, 1835)

This species was recorded by Hermida [70] under the name of Oxychilus (Morlina) glaber (Rossmässler, 1835) in Luarca (Valdés), on the riverside. Its distribution in the Iberian Peninsula includes the coast of Catalonia, as well as other provinces such as Galicia, Ávila, Castellón, Salamanca and Cáceres. Its presence in Galicia was ratified by Altonaga [119]. However, he mentions that he had not found it anywhere else in the north. It is absent in the eastern half of Galicia. This distribution gap, with the difficulty that this family presents regarding its identification, makes us question the presence of this species in Asturias. It may be a misidentification with another species of the genus Oxychilus.

Family Pristilomatidae Cockerell, 1891

Genus Vitrea Fitzinger, 1833

3.1.116. Vitrea subrimata (Reinhardt, 1871)

Species distributed throughout southern Europe and the northeast Iberian Peninsula. A rare species in the region, it lives in humid places, usually under stones, logs or leaf litter. This species has historically been recorded throughout the Iberian Peninsula under the name of Vitrea narbonensis (Clessin, 1877). However, it is currently considered an endemism from southern France and therefore absent on the Iberian Peninsula. The records of this species by Bofill and Haas [32] under the name of Hyalinia (Vitrea) narbonnensis Clessin, 1877 on the road from Castrillón to Sta. Maria del Mar correspond to V. contracta as indicated by Hermida [70]. Thus, V. narbonensis are not part of the fauna of the region.

3.1.117. Vitrea contracta (Westerlund, 1871)

Species with a Euro-Mediterranean distribution found in practically all the Iberian Peninsula. It is frequent in Asturias and usually lives in the humid microhabitat formed under stones, logs and among the leaf litter. Álvarez-Cuesta et al. [28] recorded V. crystallina (O. F. Müller, 1774) in the Integral Reserve of Muniellos. However, after reviewing the material it turned out to correspond to a misidentification with V. contracta.

Superfamily Parmacelloidea P. Fischer, 1856 (1855)

Family Milacidae Ellis, 1926

Genus Milax Gray, 1855

3.1.118. Milax nigricans (Philippi, 1836)

It is a slug broadly distributed in central Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula occurs in the Mediterranean. In the north, it is distributed until Asturias, where its status is completely unknown. Hermida [70] collected some specimens, after which it has not been recorded again. It is a slug that prefers ruderal and anthropized areas.

3.1.119. Milax gagates (Draparnaud, 1801)

Slug with a patchy distribution in Europe, widely distributed in the Iberian Peninsula. The records from Asturias are scarce [28,70,80]. Curiously, Asturias is the northern region with the least records of this species. It is an anthropical and ruderal slug that occurs in orchards, gardens, walls and forests. M. gagates and M. nigricans are similar species difficult to distinguish without anatomical analysis. More studies are needed to reach the real abundance of Milax species and for clarifying the status of these two species in the study area. However, specimens from the Integral Reserve of Muniellos could not be reviewed due to its bad conservation condition.

Superfamily Trochomorphoidea Möllendorff, 1890

Family Euconulidae H. B. Baker, 1928

Genus Euconulus Reinhardt, 1883

3.1.120. Euconulus fulvus (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Holarctic species. It is widely distributed in the Iberian Peninsula missing in some provinces, probably due to sampling deficiencies. Frequent species in Asturias. It lives in a wide variety of environments: montane meadows, deciduous forests, riverbanks and gardens. A recent review of Euconulus is provided in Horsáková et al. [120].

Superfamily Helicoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Helicidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Cepaea Held, 1838

3.1.121. Cepaea hortensis (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species distributed throughout central and western Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula it is only distributed along the Pyrenees, in the mountains systems of Guadalajara, Cuenca and Teruel and La Rioja. It usually lives in forests close to riversides. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. This snail was found alive in Alto L’Angliru Mountain.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Grandiella, L’Angliru (Riosa). one specimen. 15—X-2016. (30TTN63429172).

3.1.122. Cepaea nemoralis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Species widely distributed throughout Europe. An abundant species in the Iberian Peninsula more frequent in the northern. It is a very common species in Asturias. Highly adapted to anthropized environments, it presents a great variability of different color morphs. It lives in a wide variety of environments being especially common in gardens, orchards and walls.

Genus Cornu Born, 1778

3.1.123. Cornu aspersum (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species widely distributed throughout Europe and the entire Iberian Peninsula. Probably one of the most common and known species in Asturias, well adapted to anthropization. Its habitat is very similar to that of C. nemoralis which it lives in sympatry. It is a species with gastronomic interest.

Genus Eobania P. Hesse, 1913

3.1.124. Eobania vermiculata (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species distributed throughout the European Mediterranean area that mainly occupies the eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula. There are only two known records in Asturias: one empty shell found in 1989 in a private garden located in Baldornón (Gijón) and another empty shell found in 2015 in a roadside adjacent to a farm in La Campa Torres in Gijón [42]. Its origin is uncertain. It seems more likely that they are punctual introductions related to the trade of garden and horticulture plants [46].

Genus Helix Linnaeus, 1758

3.1.125. Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758

Species distributed throughout central and southern Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula the only isolated specimens have been recorded as introductions in Catalonia and Valencia. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. This snail was found alive in Isabel la Católica park in 2016, one of the busiest urban parks in Gijón, with numerous native Iberian and ornamental plants. The potential pathway of introduction of this species is, probably, the gardening of ornamental plants.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: Isabel la Católica park (Gijón): one live specimen. 2016. (30TTP86442395).

Genus Otala Schumacher, 1817

3.1.126. Otala lactea (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Species distributed throughout the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula and the north of Morocco. It lives in all kinds of environments from calcareous surfaces to dry and sunny areas, among rocks and vegetation. Here, we present the first record of this species for Asturias. Some adults of this snail were found alive in the in the facilities of a greenhouse in La Corredoria (Oviedo) during 2013–2019. The introduction of this species is probably linked to the importation of ornamental plants to the greenhouse from southern regions of Spain where this species is really common.

Material examined: Spain–Asturias: La Corredoria (Oviedo), near a greenhouse: 21 specimens. 2013–2019. (30TTP71310756).

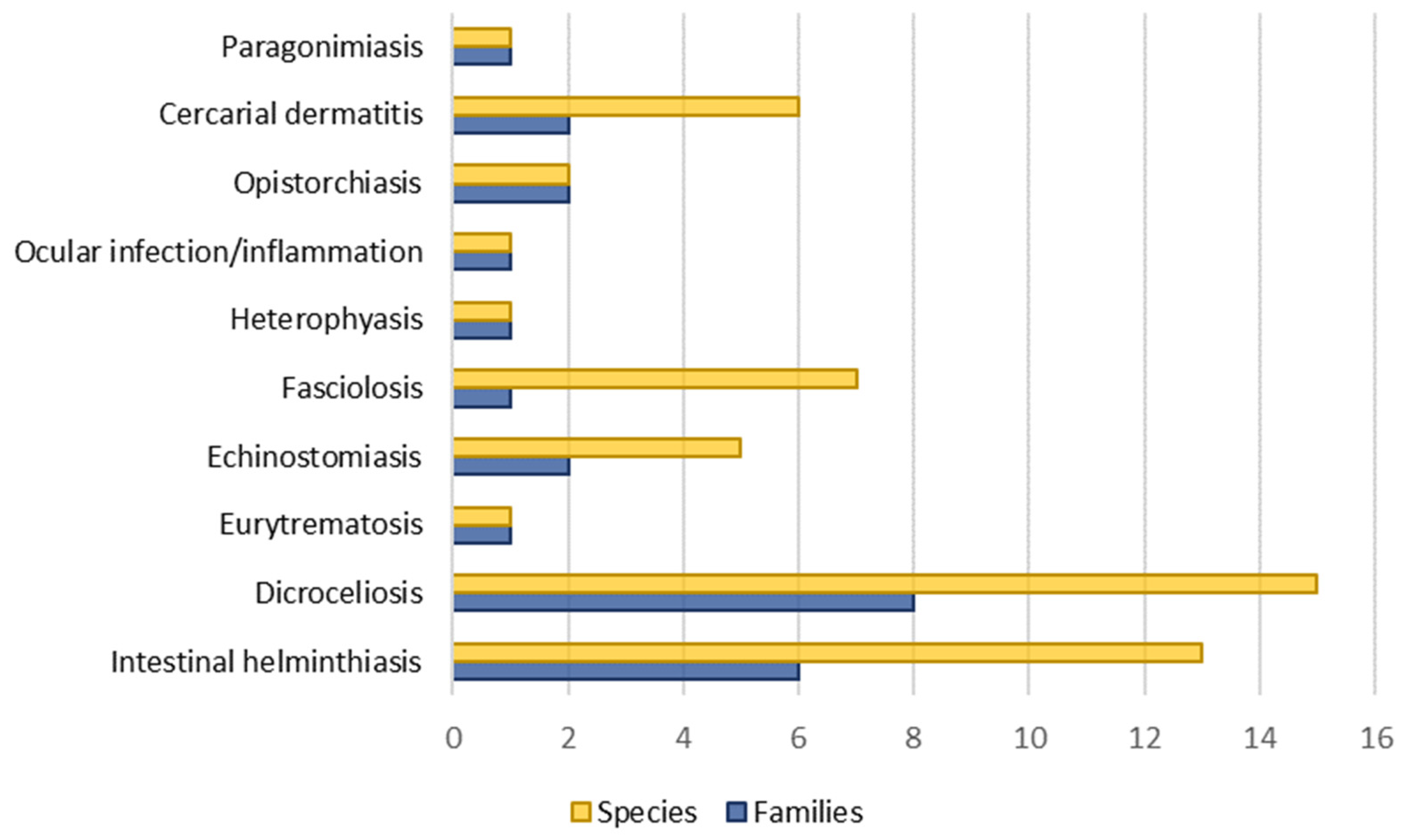

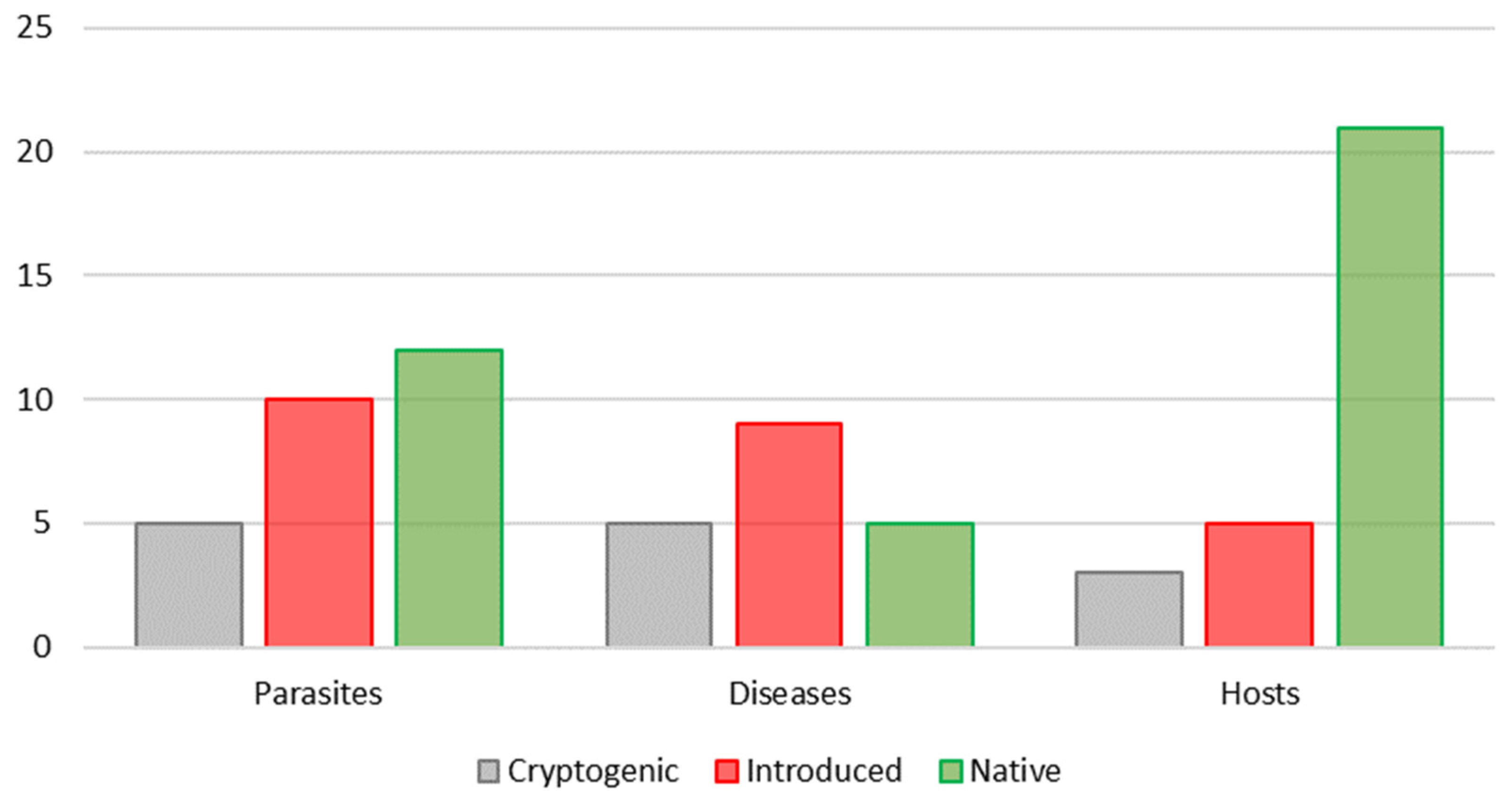

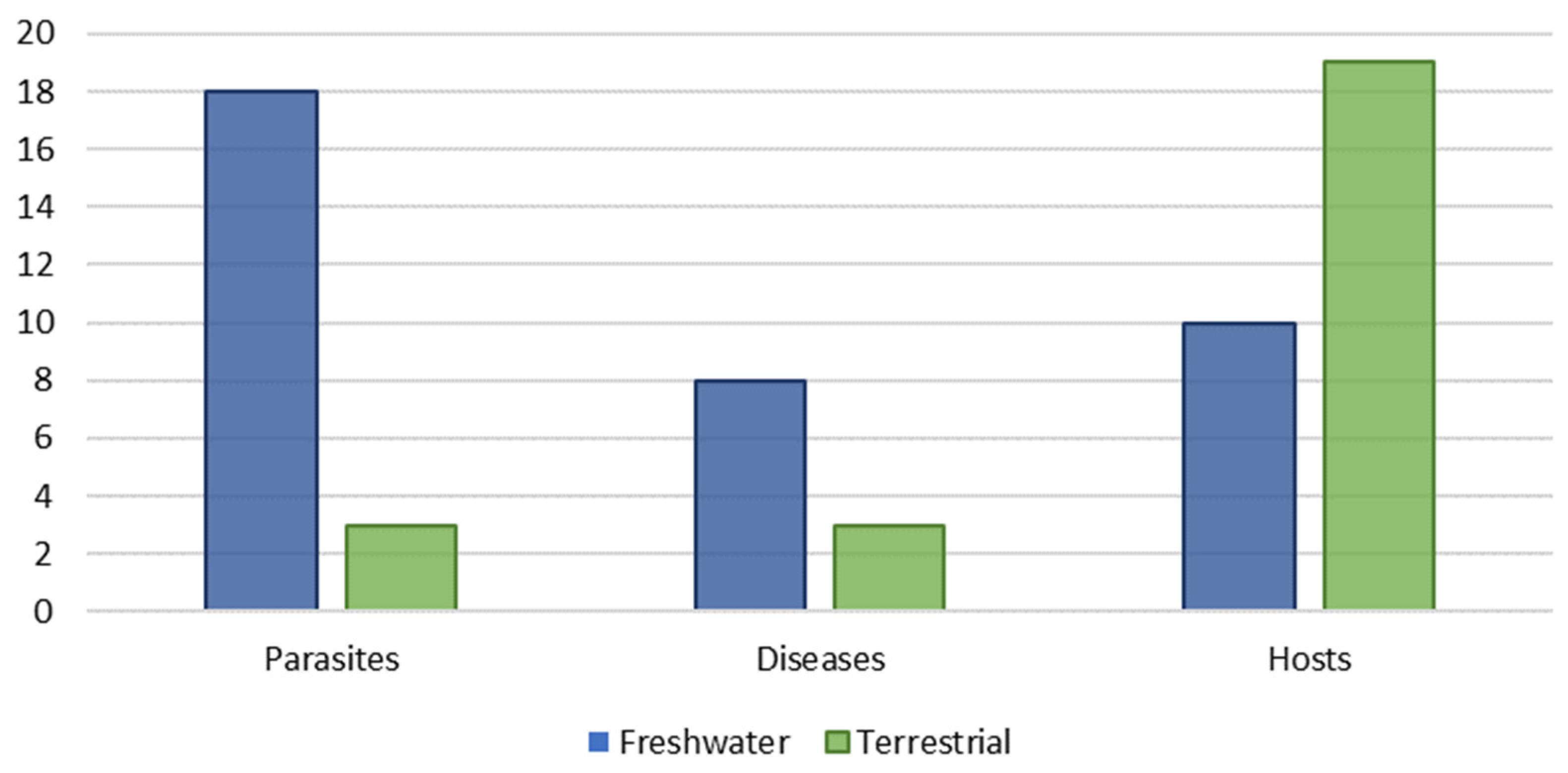

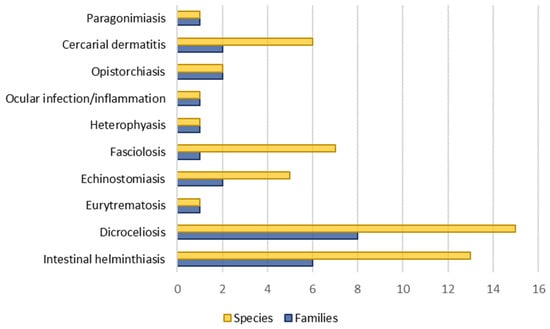

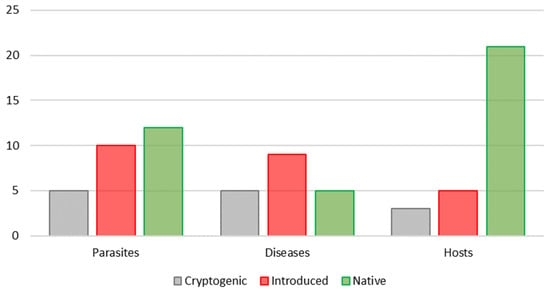

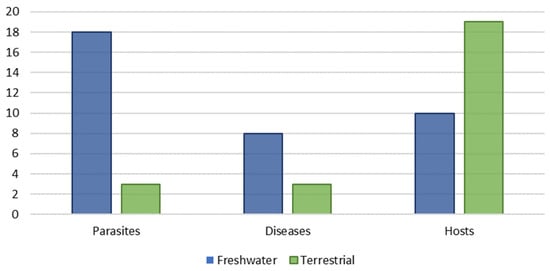

3.1.127. Otala punctata (O. F. Müller, 1774)