Abstract

Lichens are used in traditional medicine, food and various other ethnic uses by cultures across the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China. Evidence-based knowledge from historical and modern literatures and investigation of ethnic uses from 1990 proved that lichen species used as medicine in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China totaled to 142 species; furthermore, 42 species were utilized as food. Moreover, some lichens are popularly used for lichen produce in ethnic and modern life. An understanding and clarification of the use of lichens in the Himalayas and southeastern parts of China can therefore be important for understanding uses of lichens elsewhere and a reference for additional research of lichen uses in the future.

1. General Introduction of Lichen Uses

Lichens are composite organisms containing algae (e.g., Trebouxia or Trentepohlia), or cyanobacteria (Nostoc), living among filaments of multiple fungal species in a mutualistic relationship [1,2]. Lichens dominate vegetation types on about 7% of the planet’s surface; additionally, they are important components of primary producers in a wide range of substrates and habitats, including some of the most extreme conditions on earth (North and South Pole, desert, even glass surfaces, etc.) [3]. Many lichens (such as Usnea Dill. ex Adans., Everni Ach., Hypogymnia (Nyl.) Nyl., Parmelia Ach. et al.) are very sensitive to environmental disturbances and they can be used to assess air pollution [4,5,6]. Unlike simple dehydration in plants and animals, lichens may experience a complete loss of body water in dry periods [7]. Lichens are important in contributing nitrogen to soils either by forming litter, or predation by herbivores, e.g., snails, which then defecate, providing nitrogen to the soils [8]. In deserts and semi-arid areas, lichens are part of extensive, living biological soil crusts, essential for maintaining the soil structure. They have a long fossil record in soils, dating back 2.2 billion years [9].

Lichens are also important in diets for humans and animals. Based on research on the diet of Rhinopithecus roxellana Milne-Edwards in China, lichens are the most eaten food for Rh. roxellana (Figure 1a), accounting for 38.4% of the overall diet [10]. The regional diversity of lichens will also affect the changes in the living area of Rh. roxellana. Moreover, for the human diet, mostly in the temperate and arctic regions of the world, people usually use lichens as food, pharmaceutical products, and various ethnic uses [11]. In the past, Iceland moss (Cetraria islandica (L.) Ach.) was an important source of food for humans in northern Europe and the lichen was cooked as bread, porridge, pudding, soup, or salad. Wila (Bryoria fremontii (Tuck.) Brodo & D. Hawksw.) was an important food in parts of North America, where it was usually pit cooked. Northern peoples in North America and Siberia traditionally eat the partially digested reindeer lichen (Cladonia P. Browne) after they remove it from the rumen of caribou or reindeer that have been killed. Rock tripe (Umbilicaria Hoffm. and Lasallia Mérat) is a lichen (sometimes more species of lichens) that has frequently been used as an emergency food in North America and one species, Umbilicaria esculenta (Miyoshi) Minks, is used in a variety of traditional Korean and Japanese foods [12].

Figure 1.

Lichens are used by animals and humans. (a) Rhinopithecus roxellana eating Usnea in southwestern China; (b) Bai minority people harvesting lichens in Yunnan; (c) Ethnic lichen market in Yunnan. (d) Freshly gathered lichens for the kitchen in Nepal; (e) Health-promoting tea products of Lethariella and Thamnolia; (a–c,e) photographed by Li-Song Wang; (d) photographed by Shiva Devkota.

Ethnolichenology is a branch of ethnobotany that studies the uses that man makes of lichens traditionally [13,14]. Lichens are used for many different medicinal purposes, but there are some general categories of use that reoccur across the world. Lichens are often drunk as a decoction to treat ailments relating to either the lungs or the digestive system [15,16,17,18]. This is particularly common in the Himalayas and southeastern China. Many other uses of lichens are related to treating gynecological diseases. This may be related to the common use of lichens for treating sexually transmitted infections and aliments of the urinary system [11]. Two other uses of lichens that are less common, but reoccur in several different cultures, are the treatment of eye afflictions and use in smoking mixtures [11]. Besides, lichens are often used externally for dressing wounds, either as a disinfectant or to stop bleeding [18]. Other common topical lichen uses are for skin infections and sores, including sores in the mouth [11,19]. Many of the traditional medicinal uses of lichens are probably related to their secondary metabolites, many of which are known to both be physiologically active and act as antibiotics [15]. However, some of the traditional uses of lichens also rely on the qualities of lichen carbohydrates. Many of the traditional uses of lichens involve boiling the lichen to create a mucilage which is drunk for lung or digestive ailments, or applied topically for other issues [17,18,20]. Other lichen carbohydrates which may be important are the isolichenins and galactomannans, which are widespread across various taxonomic groups of lichens, and the pustulins, that are found in Umbilicariaceae [11].

Today, ethnic groups inhabiting the mighty Himalayas (Bhutan, China, India and Nepal) primarily adapt the classical systems of medicine following Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Amchi practices and continue their traditional uses of lichens for food, beverages and traditional medicine. Within the last decade, however, the sale of lichens for folk uses, especially for supposedly health-promoting teas, has increased remarkably, as the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China have become popular regions for domestic tourism (Figure 1b,e).

Since 1990, the authors have studied these folk uses as part of a broader investigation of the lichen flora of southwestern parts of China, with aims to reveal the species diversity of lichens used traditionally and currently, the diversity of various uses by studying records from herbaria and other notes and interviewing current population. The present paper summarizes the results of our ethnobotanical investigation, which has already been treated in our previous studies [21,22,23,24,25,26], and other related research references, which are listed in this study. We expect that the understanding of the use of lichens in the Himalayas and southeastern parts of China will serve as an important reference for additional research of lichen uses.

2. Materials and Methods

Chinese samples are available in the Lichen Herbarium of the Kunming Institute of Botany (KUN-L) and we reviewed useful lichen collections housed at different herbaria (KATH, TUCH) and at the Natural History Museum, Tribhuvun University, Nepal, for their additional notes, if any. We interviewed local people about their uses of lichens and visited ethnic markets to buy samples of the lichens offered for sale and also to ensure the legitimacy, relevance and credibility of the given evidence.

Specimens were examined using standard microscopic techniques and hand-sectioned under a Nikon SMZ 745T dissecting microscope. Anatomical descriptions are based on observations of these preparations under a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope. Secondary metabolites of all the specimens were identified using spot tests and thin-layer chromatography (TLC), as described by White and James [27] and Orange et al. [28]. Solvent system C (toluene:acetic acid = 85:15) was used for TLC analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Traditional Medicinal Lichens in the Himalayas and Southwestern Parts of China

Introduction of Typical Medicinal Lichens

Some of the typical, traditionally applied lichens are presented in Figure 2. Several species of Lobaria (Schreb.) Hoffm. are frequently used traditional medicines effective for treating pneumonia in the Himalayas and southwestern China, due to their lung-like appearance (applied because of the doctrine of signatures, suggesting that herbs can treat body parts that they physically resemble) [23,29]. Lobaria species have also been reported to serve as a valuable source of proteins, having a protein content higher than that of kelp or edible fungi, such as Tremella Pers. In addition, the content of dietary fiber in Lobaria species is significantly higher than in other fungi and edible algae and Lobaria species are rich in calcium [30]. Similarly, Peltigera leucophlebia (Nyl.) Gyeln. is used as a supposed cure for thrush (Aphtha, Candidiasis), due to the resemblance of its cephalodia to the appearance of the disease [31]. The earliest report about traditional medicin of lichen could be the Usnea longissima Ach. in the Chinese Qing dynasty (ca. 1500); it was reported that the Usnea species were used as litmus, to treat cold, swelling and pain [32]. Lichens also have their place in current pharmaceutical research; lichens produce metabolites of potential therapeutic or diagnostic value [18]. Some metabolites produced by lichens are structurally and functionally similar to broad-spectrum antibiotics, while a few of them are associated, respectively, with antiseptic similarities [33]. Usnic acid is the most commonly studied metabolite produced by lichens [15]. It is also under research as a bactericidal agent against Escherichia coli (Migula) Castellani & Chalmers and Staphylococcus aureus Bergey.

Figure 2.

Selected traditional medicinal lichens. (a) Sulcaria sulcata (Lév.) Bystrek; (b) Cladonia sp.; (c) Lobaria sp.; (d) Usnea longissima. Photographed by Li-Song Wang.

3.2. Summary of Research on Medicinal Lichens

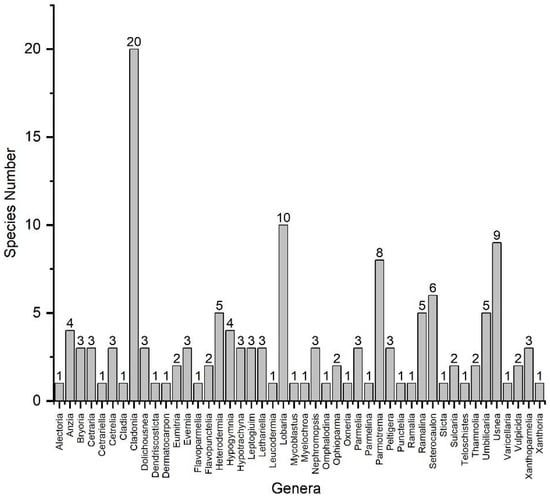

Textual research of several publications have documented the inventory and ethnic uses of lichens from Nepal [22,34,35,36,37], India [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], Bhutan [19,42] and southwestern parts of China, in ancient [32] and modern research [14,23,25,43,44]. The literature and investigation of folk usages proved that lichen species used as medicine in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China totaled to 142 species belonging to 16 families and 46 genera. Figure 3 provides the species number within the different genera of traditional medicinal lichens. Table 1 presents lichen species in alphabetical order and provides the details on each traditional use.

Figure 3.

Species number within the different genera of traditional medicinal lichen.

Table 1.

Lichen species used in traditional medicine or herbal medicine in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China. The newly added ones through our investigation are indicated in boldface.

3.3. Edible Lichens in the Himalayas and Southwestern Parts of China

3.3.1. Introduction of Typically Edible Lichen

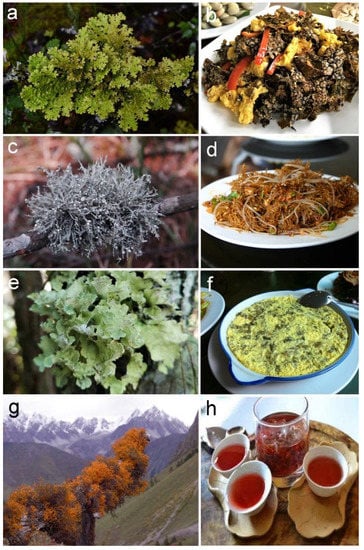

In the past, edible lichens were mostly gathered for private consumption [24]. In recent years, edible lichens are increasingly sold by local people or tourists as a commodity, after drying in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China (Figure 4). Lethariella (Motyka) Krog and Thamnolia Ach. ex Schaer. are widely used as health-promoting teas, Lobaria, Umbilicaria Hoffm., Nephromopsis Müll. Arg. and Ramalina Ach. are used as food and are relatively common in the local supermarkets and some restaurants. Normally, summer and autumn are the best seasons to harvest edible lichens, which are used fresh or dried for later use. Usually, stewing with burns, steaming, cooking soup and other methods are used to make dishes, such as “Liang Ban” Ramalina, etc.

Figure 4.

Selected edible lichens in the Himalayas and southwestern China. (a) Lobaria; (b) Scrambled eggs with Lobaria; (c) Ramalina fastigiata; (d) “Liang Ban” Ramalina; (e) Nephromopsis pallescens (Schaer.) Y.S. Park; (f) Egg custard with Nephromopsis pallescens; (g) Lethariella; (h) Lethariella tea. Photographed by Li-Song Wang.

3.3.2. Summary of Research on Edible Lichen

By researching ancient and modern literature and investigating folk usages in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China, it is obvious that people generally name edible lichen “shuhua” or “shihuacai”; the names mean flowering form of an organism growing on the trees or stones and these phrases are still in use. Here we document a total of 42 species belonging to 18 genera of lichens that are edible (Table 2). The most commonly used genera of lichens are foliose or fruticose growth forms (such as Hypotrachyna, Lethariella, Lobaria, Nephromopsis, Ramalina, Thamnolia and Umbilicaria). The edible lichens counted in this article are limited and more investigation and research are needed in the future.

Table 2.

Edible lichens in Himalayas and southwestern China.

4. Other Ethnic and Modern Uses

Lichens are mainly used by humans for medicine and foods in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China, but we have also found many other, novel uses for these organisms in a local place. Lethariella, only distributed at around 3700–4300 m in the Himalayas, is mainly sold in Yunnan and Shangri-La, China, and also exported to Taiwan and Japan. In the Himalayas, Tibet is a holy place of Buddhism and there is a great demand for Tibetan incense; Lethariella is also used as an important component of Tibetan incense because of its special fragrance (Figure 5a). Besides, in current applications of lichens, Usnea and Sulcaria are used for raw materials of perfume and fragrance in Yunnan (Figure 5b). Cladonia is commonly used as garden decoration in China. Devkota et al. [22] reported ritual and spiritual value (RSV), aesthetic and decorative value (ADV), bedding value (BV) and ethno-veterinary values (EVV) of lichens, together with medicinal value (MV) and food value (FV), among different collectors and indigenous people and local communities (IPLCs) in Nepal. Cetrelia collata (Nyl.) W.L. Culb. & C.F. Culb. (current name: Platysma collatum Nyl.) is used as a sacrificial fiber, together with Melanelia infumata (Nyl.) Essl., Everniastrum cirrhatum and Parmotrema nilgherrense, Usnea ghattensis G. Awasthi, for coloring hair, Thamnolia vermicularis (Sw.) Schaer., with its spiritual value in India and Nepal [22,45], and Buellia subsororioides, used to color palms and lips as a substitute for Heena, mostly by the Garhwali Herdsman in Uttarakhand and India [39]. Furthermore, Shukla et al. [55] have also highlighted the use of eleven lichen species as dying agents in Gharwal region of India.

Figure 5.

(a) Lethariella, used for Tibetan incense; (b) Usnea and Sulcaria, used for raw materials of perfume in Yunnan; (a) Photographed by Mei-Xia Yang; (b) photographed by Li-Song Wang.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Our investigation and survey of the literature indicate that 142 lichen species are used as medicine and 42 species are used as food in the Himalayas and southwestern parts of China. We found considerable overlap between the medicinal and consumed lichens; except for three species of edible lichens (Leptogium wilsonii, Leucodermia leucomelos and Lobaria isidiophora), other species with edible uses also have medicinal functions (Table 1 and Table 2). Therefore, the popularity of consuming healthy food items might be explained by their preventive role. Almost all food lichens are cooked in some way before being eaten and the cooking process is often complex, usually involving steps to remove toxins from the lichen [11,22,23,25,43]. For the medicinal lichens, the secondary compounds and carbohydrates are useful to humans. The studies reported that the nutritionally relevant carbohydrates in lichens include the glucans lichenin and isolichenin [11,14]. Some lichens also have significant levels of proteins and essential amino acids, as well as some minerals and vitamins, but most lichens only have minimal amounts of these nutrients [11,12,15,30]. Some lichens are only eaten in times of famine, some are a staple food or even a delicacy in the Himalayas and southwestern China. The medicinal and edible usage of lichen as healthy food is becoming more and more popular among local people and tourists. However, two obstacles are often encountered when eating lichens: lichen polysaccharides are generally indigestible to humans and lichens usually contain mildly toxic secondary compounds that should be removed before eating. Very few lichens are poisonous, but those having high concentrations of vulpinic acid or usnic acid are toxic [56].

Lichen resources are especially abundant in the Himalayas and southeastern parts of China and it is also a major advantage that they mostly grow at high altitudes without human activity and pollution. In recent years, resource survey and research on lichens as food and medicine have also been reported in these areas. Unfortunately, there are still some problems concerning the classification of species and the unclear distribution of resources; therefore, for example, the species classification of the genus Lobaria and the resource distribution of Lobaria in these areas also need to be investigated. At present, most lichens for food and traditional medicine are used directly as lichen raw materials and, considering that many lichens grow slowly, it results that lichens productivity is usually low. However, there are still some ecosystems of foliose lichens (e.g., Lobaria pulmonaria) that can produce significant lichen biomass within approximately a decade [57,58]. The low productivity of lichens means that over-harvesting is a real concern. For example, the genus Lethariella—with known distribution only in the Himalayas and southeastern parts of China—has reached an endangered state before its active ingredients and mechanisms could be fully understood. Based on our recent study, we expect to carry out further relevant research on effective medicinal and nutritional ingredients of lichens in the future and explore ways to obtain the required effective ingredients through artificial culturing or by fermentation, also to reduce the dependence on natural resources. Therefore, combining results of lichen taxonomy, ecology, chemistry and pharmacology is a top priority for our forthcoming research. At the same time, effective protection measures for some endangered species are important for the sustainable use of lichen resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and M.-X.Y.; methodology, M.-X.Y.; software, M.-X.Y.; validation, M.-X.Y. and C.S.; formal analysis, M.-X.Y.; investigation, L.-S.W., C.S. and S.D.; resources, L.-S.W. and S.D.; data curation, M.-X.Y., L.-S.W. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-X.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.-X.Y., C.S., S.D. and L.-S.W.; visualization, M.-X.Y. and C.S.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, C.S., S.D. and L.-S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant JRP IZ70Z0_131338/1 to C.S.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31970022, 31670028), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (No. 2019QZKK0503), the Global Biodiversity Information Facility/Biodiversity Fund for Asia (Project No: BIFA5_023 to S.D.) and the China Scholarship Council (CSC No. 201704910901).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Xin-Yu Wang (Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS, China) and Dong Liu (Central South University of Forestry and Technology, China), for supporting expedition and research in China; the Lichen Herbarium of the Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS for providing research support; Ram Prasad Chaudhary (RECAST Kathmandu, Nepal) and Krishna Kumar Shrestha (Tribhuvan Univ. Kathmandu, Nepal), for supporting research in Nepal; and Karma Tshering, for giving insights into ethnobotany in Bhutan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spribille, T.; Tuovinen, V.; Resl, P.; Vanderpool, D.; Wolinski, H.; Aime, M.C.; Schneider, K.; Stabentheiner, E.; Tomme-Heller, M.; Thor, G.; et al. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 2016, 353, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Irwin, M.B.; Sylvia, D.S.; Stephen, S. Lichens of North America; Yale Univeristy Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2001; p. 828. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, O.W. Lichens; The Natural History Museum: London, UK; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Henssen, A.; Jahns, M. Lichenes—Eine Einführung in die Flechtenkunde; Thieme Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 1974; p. 467. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, C.I.; Hawksworth, D.L. Lichen recolonization in London’s cleaner air. Nature 1981, 289, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Rose, F. Lichens as Pollution Monitors; Institute of Biology’s Studies in Biology: London, UK, 1979; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.H.; Harris, R.F. The Ecology and Biogeography of Microorganisms on Plant Surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2000, 38, 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.G.; Shachak, M. Fertilization of the desert soil by rock-eating snails. Nature 1990, 346, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retallack, G.J.; Krull, E.S.; Thackray, G.D.; Parkinson, D. Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa. Precambrian Res. 2013, 235, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.C.; Stanford, C.B.; Yang, J.; Yao, H.; Li, Y. Foods eaten by the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Shennongjia National Nature Reserve, China, inrelation to nutritional chemistry. Am. J. Primatol. 2013, 75, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.D. Lichens used in traditional medicine. In Lichen Secondary Metabolites: Bioactive Properties and Pharmaceutical Potentialsecond; Ranković, B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 31–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, G.A. Lichens, their biological and economic significance. Bot. Rev. 1944, 10, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illana-Esteban, C. Lichen used in perfumery. Bol. Soc. Micol. Madr. 2016, 40, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, S. Ethnolichenology of Bryoria Fremontii: Wisdom of Elders, Population Ecology, and Nutritional Chemistry. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bustinza, F. Antibacterial Substances from Lichens. Econ. Bot. 1952, 6, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H. 中外药用孢子植物资源志要 [Zhong Wai Yao Yong Bai Zi Zhi Wu Zi Yuan Zhi Yao = Illustrated Medicinal Spore Plant of China]; Guizhou Science and Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 2010; pp. 183–212. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Upreti, D.K.; Bajpai, R.; Nayaka, S. Lichenology: Current research in India. In Plant Biology and Biotechnology: Volume I: Plant Diversity, Organization, Function and Improvement; Bahadur, B., Venkat Rajam, M., Sahijram, L., Krishnamurthy, K.V., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliya, B.S.; Baipai, R.; Jadun, V.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, S.; Upreti, D.K.; Singh, B.R.; Nayaka, S.; Joshi, Y.; Singh, B.N. The genus Usnea: A potent phytomedicine with multifarious ethnobotany, phytochemistry and pharmacology. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 21672–21696. [Google Scholar]

- Søchting, U. Lichens of Bhutan-Biodiversity and Use; University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nayaka, S.; Upreti, D.K.; Khare, R. Medicinal lichens of India. In Drugs from Plants; Trivedi, P.C., Ed.; Avishkar Publishers: Jaipur, India, 2010; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-S. 中国云南地衣 [Zhong Guo Yunnan Di Yi = Illustrated Lichen in Yunnan, China]; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2012; pp. 1–228. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Devkota, S.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Werth, S.; Scheidegger, C. Indigenous knowledge and use of lichens by the lichenophilic communities of the Nepal Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.-S.; Qian, Z.-G. 中国药用地衣图鉴 [Zhong Guo Yao Yong Di Yi Tu Jian = Illustrated Medicinal Lichens of China]; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Yunnan, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.S.; Narui, T.; Harada, H.; Curberson, C.F.; Culberson, W.L. Ethnic uses of lichens in Yunnan, China. Bryologist 2001, 104, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-X.; Wang, X.-Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Li, L.-J.; Yin, A.-C.; Wang, L.-S. Evaluation of edible and medicinal lichen resources in China. Mycosystema 2018, 37, 819–837. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-S. Introduction to five edible lichens. Edible Fungi China 1993, 12, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.J.; James, P.W. A new guide to the microchemical techniques for the identification of lichen substances. Br. Lichen Soc. Bull. 1985, 57, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Orange, A.; James, P.W.; White, F.J. Microchemical Methods for the Identification of Lichens; British Lichen Society: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-L. 中国地衣植物图鉴 [Zhong Guo Di Yi Zhi Wu Tu Jian = Illustrated Lichen in China]; China Outlook Press: Beijing, China, 1987; pp. 1–236. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.-Y.; Duan, H. Study on edible lichens in China. Jiangsu Agric. Res. 2000, 21, 59–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, F.S. Lichens, an Illustrated Guide to the British and Irish Species; Richmond Publishing: Slough, UK, 2011; p. 520. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.-M. 本草纲目拾遗 [Ben Cao Gang Mu Shi Yi = Illustrated Supplements to Compendium of Materia Medica]; 1765. (Qing-Dynasty). (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Muller, K. Pharmaceutically Relevant Metabolites from Lichens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 56, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacherer, J. The high altitude ethnobotany of Rolwaling Sherpas. CNAS J. 1979, 6, 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, T.B.; Subba, D.; Subba, R. “Yangben” The edible lichens of east Nepal and their food value. J. Nat. Hist. Mus. 2000, 19, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Limbu, D.K.; Rai, B.K. Ethno-medicinal practices among the Limbu community in Limbhuwan, Eastern Nepal. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Devkota, S.; Scheidegger, C. Hypotrachyna nepalensis (Taylor) Divakar, A. Crespo, Sipman, Elix & Lumbsch Parmeliaceae. In Ethnobotany of the Himalayas; Kunwar, R.M., Sher, H., Bussmann, R.W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, B.; Upreti, D.K. Ethnobotanical notes on three Indian lichens. Lichenologist 1995, 27, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Upreti, D. Diversity of lichens in India. In Perspectives in Environment; Agrawal, S., Kaushik, J., Kaul, K., Jain, A., Eds.; APH Publishing Corporation: New Delhi, India, 1998; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, P.; Upreti, D.K. Lichen dyes: Current scenario and future prospects. In Recent Advances in Lichenology; Upreti, D.K., Divakar, P.K., Shukla, V., Bajpai, R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Upreti, D.K.; Lehri, A.; Paliwal, A.K. Quantification of lichens commercially used in traditional perfumery industries of Utter Pradesh, India. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 4, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk, P.; Namgay, K.; Gayleg, K.; Dorji, Y. Medicinal plants of Dagala region in Bhutan: Their diversity, distribution, uses and economic potential. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, J.-C.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wu, J.-L.; Chen, X.-L. 中国药用地衣 [Zhong Guo Yao Yong Di Yi = Illustrated Medicinal Lichens of China]; Beijing Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 1982; pp. 1–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, M.R.; Jaeseoun, H.; Jaeyong, K.; Kyoungwuk, P.; Seongchan, P.; Chinam, S.; Llyun, J.; Myungwoo, B.; Mikyung, L.; Kwonll, S. Anti-proliferative effects of Lethariella zahlbruckneri extracts in human HT-29 human colon cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upreti, D.K.; Bajpai, R.; Nayaka, S.; Singh, B.N. Ethnolichenological studies in India: Future prospects. In Indian Ethnobotany: Emerging Trends; Jain, A.K., Ed.; Scientific Publishers: Jodhpur, India, 2015; pp. 195–231. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board of “Chinese Materia Medica” of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 中华本草 (1) 地衣类植物药 [Zhong Hua Ben Cao (1) Di Yi Lei Zhi Wu Yao = Illustrated Medicinal Lichen in China]; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The Compilation Group of Chinese Herbal Medicine. 全国中草药汇编 (下册) [Quan Guo Zhong Cao Yao Hui Bian (Xia Ce) = Illustrated Medicinal Plant of China]; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1978. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shaanxi Provincial Revolutionary Committee Health Bureau. 陕西中草药 [Shan Xi Zhong Cao Yao = Illustrated Medicinal Plant in Shanxi]; Beijing Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 1971. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.-S. 中国药用孢子植物 [Zhong Guo Yao Yong Bao Zi Zhi Wu Zhi = Illustrated Medicinal Spore Plant of China]; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1982. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Zhou, T.-Y.; Xiao, P.-G. 新华本草纲要 (第3册) [Xin Hua Ben Cao Gang Yao (Di 3 Ce) = Illustrated Xinhua Materia Medica]; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1990. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Q.-R.; Yang, M.; Gao, S.-X. The development of Guizhou lichen spice and its application in flavor adjustment. Flavour Fragr. J. 2000, 3, 5–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Zhong, B.-G. Study on Lichen Spice Plants in Guizhou. Guizhou Sci. 2003, 21, 75–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiangsu New Medical College. 中药大辞典 (上, 下册) [Zhong Yao Da Ci Dian = Illustrated Dictionary of Chinese Medicine]; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1986. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.C. Lichens of commercial importance in India. Scitech J. 2014, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, P.; Upreti, D.K.; Nayaka, S.; Tiwari, P. Natural dyes from Himalayan lichens. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2014, 13, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich, R.; Giez, I.; Lange, O.L.; Proksch, P. Toxicity and antifeedant activity of lichen compounds against the polyphagous herbivorous insect Spodoptera littoralis. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplund, J.; Wardle, D.A. How lichens impact on terrestrial community and ecosystem properties. Biol. Rev. 2017, 99, 1720–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauslaa, Y.; Lie, M.; Solhaug, K.A.; Ohlson, M. Growth and ecophysiological acclimation of the foliose lichen Lobaria pulmonaria in forests with contrasting light climates. Oecologia 2006, 147, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).