Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and pathological α-synuclein aggregation. Growing evidence identifies chronic neuroinflammation—particularly NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia—as a central driver for PD onset and progression. Misfolded α-synuclein, mitochondrial dysfunction, and environmental toxins act as endogenous danger signals that prime and activate NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1–mediated maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 and subsequent pyroptotic cell death. Impaired mitophagy, due to defects in PINK1/Parkin pathways or receptor-mediated mechanisms, permits accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and release DAMPs, thereby amplifying NLRP3 activity. Studies demonstrate that promoting mitophagy or directly inhibiting NLRP3 attenuates neuroinflammation and protects dopaminergic neurons in PD models. Autophagy-inducing compounds, along with NLRP3 inhibitors, demonstrate neuroprotective potential, though their clinical translation remains limited due to poor blood–brain barrier penetration, off-target effects, and insufficient clinical data. Additionally, the context-dependent nature of mitophagy underscores the need for precise therapeutic modulation. This review summarizes current understanding of inflammasome–mitophagy crosstalk in PD, highlights major pharmacological strategies under investigation, and outlines its limitations. Future progress requires development of specific modulators, targeted delivery systems, and robust biomarkers of mitochondrial dynamics and inflammasome activity for slowing PD progression.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a slowly progressive neurological disorder that affects approximately 1% of individuals aged >65 years, increasing to 4–5% among those aged 85–90 years [1,2]. Clinically, PD is characterized by resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability, primarily due to the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra par compacta (SNpc). This neuronal loss leads to dopamine depletion in the caudate–putamen, disrupting basal ganglia circuity responsible for motor coordination [3,4]. In addition to motor impairments, PD patients exhibit a wide range of non-motor symptoms including sleep disturbances, depression, and cognitive decline. Dementia is a major complication affecting 47% of PD patients, and its prevalence substantially increase with disease progression [5]. The chief pathological hallmark of PD is the presence of Lewy bodies and intraneuronal cytoplasmic composed of insoluble α-synuclein aggregates [6,7]. The accumulation of misfolded and fibrillar α-synuclein fibrils in dopaminergic neurons contributes to neuronal dysfunction and degeneration [8]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to underlie PD pathogenesis, including chronic neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, defective autophagic clearance of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles [9,10].

The immune cell of the central nervous system (CNS) includes microglia, astrocytes and dendritic cells, which collectively maintain neuronal surveillance and regulate extracellular signaling to maintain brain homeostasis [11,12,13]. Microglia are the principal immune cells of the brain, displaying a highly ramified morphology, a small cytoplasmic volume, a polygonal nucleus, and abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) in the resting stage [14,15]. Neuroinflammation in the PD brain is closely associated with microglial activation and occurs in parallel with dopaminergic neurons death [16]. Activated microglia, positive for human leukocyte antigen-D related (HLA-DR) in the SNpc and putamen of post-mortem PD brains, were first reported by Mc Geer et al. providing evidence of neuroinflammation in PD pathogenesis [17,18]. Microglial activation may result from chronic infections, repeated tissue injury, or accumulation of misfolded proteins, which act as stress signals or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) [19,20]. While transient microglial activation is beneficial for clearing debris and pathogens, sustained or excessive activation leads to overproduction of pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS), ultimately causing neuronal damage and neurodegeneration [21,22]. Beside maintaining neuronal homeostasis by purging foreign particles and response to tissue damage or bacterial endotoxin, microglia are also involved in tissue remodeling and adaptation via continuous surveillance [23,24]. Microglia express both immune- and neuron-derived receptors on their surface and thus regulate immune as well as neuronal activity [24,25]. Furthermore, microglia establish dynamic contacts with neurons and executes several physiological functions, including synaptic plasticity, neuronal differentiation and production of neurotropic factors during brain development [26,27]. Thus, long-term distortion of microglia activation, shifting from a resting to a chronically active state, can lead to serious neurological and psychiatric disorders, as well as neurodegenerative diseases, including PD, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington disease, and more [28,29]. The generation and maturation of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18), involve activation of the intracellular multimeric protein complex known as NLRP3 inflammasomes, which acts as sensors for pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or DAMPs and contribute to the development of autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders [29]. Therefore, regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation represents a promising therapeutic strategy for PD.

Autophagy is a highly evolved catabolic process in eukaryotes that mediates the elimination and degradation of misfolded proteins and dysfunctional or redundant organelles. Factors such as nutrient deprivation, energy deficiency, and accumulation of misfolded proteins induce autophagy, leading to lysosomal degradation and generation of recycle metabolites that can be reused in several biosynthetic pathways [30,31]. One of the major pathways through which α-synucleins are degraded and lysed is through autophagy [30,32]. Accumulating evidence supports the involvement of aberrant autophagy in PD pathogenesis [33,34]. Neurotoxin such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) or rotenone, which inhibit mitochondrial complex I, lead to mitochondria dysfunctional and impaired autophagic flux, resulting in neuronal death [35,36]. Hence, timely removal of these misfolded protein or damaged mitochondria by stimulating the autophagy machinery by a pharmacological agent has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative disorders particularly PD [37].

Several regulatory mechanisms suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation, among which autophagy, especially mitophagy, has emerged as critical modulator. Induction of mitophagy eliminates damaged mitochondria and endogenous dangerous signals, thereby preventing excessive inflammasome activation [37]. Conversely, impaired mitophagy can augment NLRP3, highlighting their inverse regulatory relationship; however, the precise molecular mechanism is yet to be defined [38].

While earlier reviews have discussed mitophagy or NLRP3 inflammasome activation independently, a significant knowledge gap remains regarding how their bidirectional crosstalk influences PD pathogenesis. Findings from the last decade demonstrating how defective mitochondrial turnover exacerbates neuroinflammation are rarely integrated, and the current literature does not thoroughly evaluate therapeutic strategies targeting both pathways simultaneously. To address this gap, the present review is based on a comprehensive and critical evaluation of peer-reviewed studies retrieved primarily from PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases using combinations of keywords including “Parkinson’s disease,” “NLRP3 inflammasome,” “mitophagy,” “autophagy,” “neuroinflammation,” “microglia,” and “mitochondrial dysfunction.” The review focuses mainly on studies published in English between 2015 and 2025, with inclusion of seminal earlier works where necessary to provide historical and mechanistic context.

This review differs from the existing literature by providing an updated and integrated perspective on how disrupted mitophagy and hyperactive NLRP3 signaling jointly drive PD progression rather than offering a broad overview of all PD-related pathways. Studies were included if they directly examined NLRP3 inflammasome signaling, mitophagy or autophagy processes, or mechanistic interactions between these pathways in PD or PD-relevant experimental models. In contrast, studies were excluded if they focused exclusively on unrelated inflammatory pathways, lacked relevance to inflammasome activation or mitochondrial quality-control mechanisms, or did not provide mechanistic insight into neurodegeneration

2. Inflammasomes Expression, Activation and Regulation

2.1. Inflammatory Mechanisms in the Brain

Inflammation in the brain is an innate immune response triggered by noxious stimuli that may threaten cellular homeostasis. This response requires the immediate elimination of harmful agents and the promotion of tissue repair [39]. However, persistent low-grade neuroinflammation disrupts neuronal homeostasis and activates various pro-inflammatory mediators, especially IL-1β, IL-18, caspase-1, and IL-33, all of which can contribute to neurodegeneration [40]. These cytokines are widely studied because of their established roles in neuronal deficits, which make them emerging therapeutic targets.

Accumulating preclinical and clinical evidence indicates that IL-1β and caspase-1 play a pivotal role in the ignition and propagation of neuroinflammation in PD [41]. These mediators are processed and activated by the inflammasomes’ complex and multimeric immune sensors whose involvement has been established in several neurodegenerative disorders, including PD [11]. Once activated, they promote caspase-1-mediated cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active form [42,43]. The maturation and release of active IL-1β and IL-18 further amplify inflammatory cytokines production, increase immune cell infiltration, and induce pyroptotic cell death in both neuron and glial populations [44,45].

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that chronic IL-1β signaling accelerates dopaminergic neuronal loss in both toxin-induced and genetic PD models (e.g., MPTP, rotenone models), supporting its direct pathogenic contribution [46]. Likewise, elevated caspase-1 activity has been reported in post-mortem PD substantia nigra tissue, reinforcing its clinical relevance [47]. Caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis also represent a link between inflammation and programmed cell death, further justifying a focused discussion on inflammasome signaling in context of PD pathogenesis.

However, it is important to critically evaluate whether elevated IL-1β, IL-18, or caspase-1 levels in cerebrospinal fluid truly reflect NLRP3-dependent neuroinflammation in PD, as these cytokines can also be produced through inflammasome-independent mechanisms and may represent broader systemic or neuroinflammatory states rather than specific NLRP3 activation [48,49]. Therefore, while their elevation supports inflammatory involvement, it should not be interpreted as a definitive surrogate for NLRP3 activity without complementary mechanistic evidence. Together, these findings provide strong evidence that sustained inflammasome-mediated cytokine production is not merely a secondary response but a major driver of PD-associated neurodegeneration.

While oxidative stress, apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation are well-recognized contributors to the pathogenesis of PD and cannot be overlooked, accumulating evidence indicates that neuroinflammation is not merely a downstream consequence of neuronal injury. Rather, inflammatory signaling can act as an early driver that can precede and amplify oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways. In this context, inflammasome mediators, particularly NLRP3, have emerged as key mediators that integrate multiple pathogenic signals, including mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS overproduction, lysosomal damage, and misfolded α-synuclein. Therefore, this review focuses specifically on NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and highlights upstream regulatory processes, such as mitophagy, to provide a framework for early disease mechanisms and to improve understanding of PD pathogenesis.

2.2. Inflammasome Complex: Structure and Function

Whenever an immune cell senses any dangerous stimuli in the form of PAMPs or DAMPs, inflammasomes assemble in the cytoplasm, become activated, and arbitrate consequent immune responses. Several inflammasome sensors have been identified, including members of the nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat (NLR) family—NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, and NLRC4—as well as PYHIN family members (non-NLR family), such as absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) and IFI16 [50,51]. All of them can sense dangerous signals and become activated to form the human immune defense system [51]. Most inflammasomes share a common tripartite architecture consisting of an inflammasome sensor molecule, the adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein) containing a caspase 1 activation and recruitment domain (CARD) as well as the effector protease caspase-1 [52,53]. Interactions between these components induce conformational changes that activate immune activity and are therefore tightly regulated.

Several studies have demonstrated that, among the known inflammasome sensors, NLRP3 is the most strongly implicated in PD pathology. Prior work shows that mitochondrial ROS, α-synuclein fibrils, and lysosomal damage—key pathological features of PD—directly trigger NLRP3 activation in microglia [54]. In vivo studies further support this, as NLRP3 knockout mice exhibit reduced neuroinflammation and are partially protected from dopaminergic neuron loss in MPTP models [55]. Additionally, clinical studies report elevated NLRP3 components in the serum and CSF of PD patients [56], underscoring its potential translational relevance.

2.3. Structure and Activation Mechanism of NLRP3 Inflammasome

Among known inflammasomes, NLRP3 is the most extensively studied in neurodegenerative disorders and is therefore considered the prime inflammasome discussed in this review [57]. Early studies suggested that NLRP3 activation required bacterial pathogens or extracellular ATP; however, recent work has demonstrated that a wide array of stimuli and environmental insults—including’s DAMPS, metabolic stress, and particulate matters—can activate NLRP3 [58,59]. Like other inflammasomes, NLRP3 also consists of a NOD-like receptor (NLR3) domain, characterized by three distinctive regions: a central NACHT domain, a leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) domain, and a PYD or CARD mediating ASC/caspase-1 activation. These domains coordinate recognition of stimulus and ensure that NLRP3 activation occurs only under appropriate conditions, making the process highly regulated [42,60].

Activation induces oligomerization of the NLRP3 inflammasomes in brain microglia; it is governed by both transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms that require two check points, priming/transcription (Signal 1) and activation/assembly (Signal 2) [61]. The priming step is mediated by Toll-like receptor (TLR)-adaptors, including pathogenic stimuli (e.g., lipopolysaccharide), tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF) receptors, or IL-1 receptors. This step does not directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome but primes it for activation. Priming involves activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, which translocates to the nucleus and increases transcription of key inflammasomes-related genes, including NLRP3, IL-1β, and IL-18 [62,63]. However, controversy remains regarding the exact mechanisms by which TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation primes NLRP3 [59]. Some studies reported that inhibiting NF-κB does not completely prevent NLRP3 activation [64]. Other studies demonstrate that NLRP3 can also be regulated at the post-translational level, as simultaneous exposure to Signal 1 and Signal 2, for as little as 10 min, is sufficient to enhance inflammasome activation [65]. Juliana et al. showed that non-transcriptional priming via Signal 1 in mouse macrophage regulates activation of NLRP3 deubiquitnation, even without transcriptional changes [66]. Thus, further investigation is required to elucidate the precise regulatory mechanism underpinning the regulation of NLRP3.

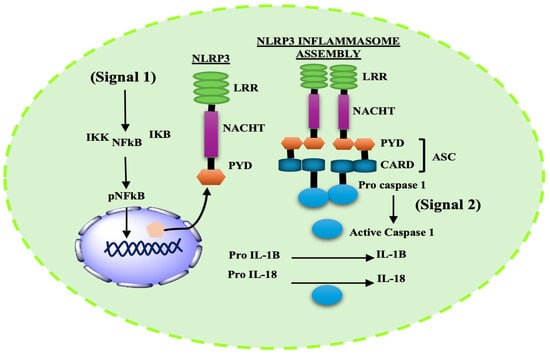

Activation (Signal 2) is triggered by PAMPs, DAMPs, or toxins. The NLRP3 PYD recruits ASC through PYD–PYD interactions, while the CARD of ASC recruits pro-caspase 1 through CARD–CARD interaction and subsequently activates the complex. This arrangement triggers the autocatalytic cleavage of the zymogen pro-caspase 1 into its active caspase-1 p20/p10 [67,68] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Two-step signaling cascade for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Signal 1 (Priming): TLR4 stimulation activates NF-κB, leading to transcriptional upregulation of NLRP3, pro–IL-1β, and pro–IL-18. Signal 2 (Activation) (e.g., mitochondrial stress, K+ efflux, ROS, or lysosomal damage) promotes NLRP3 oligomerization and assembly with ASC and pro–caspase-1, resulting in caspase-1 activation and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18.

3. NLRP3 Inflammasomes in Parkinson’s Disease

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by dopaminergic neuron loss in the SNpc and accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates [69]. Neuroinflammation appears early in PD pathology and progress alongside disease severity. Misfolded α-synuclein acts as an endogenous DAMP that activates through the NLRP3 inflammasomes [70]. Both monomeric and fibrillar α-synuclein can induce pro-IL-1β expression via TLR2 signaling, but fibrillar α-synuclein is the primary trigger for NLRP3 activation, largely through mechanisms involving phagocytosis and cathepsin B release [71,72]. IL-1β is one of the potent pro-inflammatory cytokines and promotes a wide range of immunological processes, including infection, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Elevated IL-1β levels have been verified in the nigrostriatal regions, cerebrospinal fluids, and animal models of PD [25,73]. IL-18 is another cytokine whose role has been established in several neurological disorders, including AD, schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis, and depression [74,75]. The generation of both IL-1β and IL-18 is synchronized by caspase-1, a key mediator of neuroinflammation in the PD brain.

Multiple studies in mouse models of PD demonstrate that IL-1β production is driven by NLRP3 activation in brain microglia [76]. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of NLRP3 confers protection against neurodegeneration in PD models. A recent study using HEK293 cells identified a genetic variant of NLRP3 multiple single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including rs7525979, which are associated with reduced PD [77]. Chronic IL-1β overexpression in the substantial nigra of rat brain exacerbates PD-like pathology, supporting a causal role of inflammasome signaling [78]. α-Synuclein pathology is also linked to caspase-1, which cleave α-synuclein and promotes aggregation. Inhibition of caspase-1, either by genetic knockdown or chemical inhibitors, reduces α-synuclein truncation and protects neurons [79]. Mice lacking caspase-1 exhibit delayed disease progression and resistance to nigral neuronal damage in the MPTP model [80]. Furthermore, caspase-1 knockout mice showed reduced MPTP- induced caspase-7 cleavage, preventing nuclear translocation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), whereas over-expressing caspase-7 diminishes the protective effect of caspase-1 inhibition [80].

Emerging evidence also highlights the role of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs (miRs) in the regulation of genes responsible for inflammation [81]. Specifically, microRNA-30e (miR-30e) is significantly downregulated in MPTP models, and enhancement of its activity using a miR-30e agomir improves behavior outcomes and attenuate neuronal loss via NLRP3 inhibition [82]. These findings suggest novel therapeutic strategies for modulating NLRP3 activity in neurodegenerative disorders.

Mitochondrial toxins such as MPTP and rotenone are used to model PD in animals and cell lines, implicating a potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction in disease pathogenesis [83]. In MPTP-treated mice, NLRP3 deficiency confers resistance to dopaminergic neuronal loss, thus providing a strong link between NLRP3, mitochondrial dysfunction, and PD [43]. Dopamine has been shown to negatively regulate NLRP3 activation via binding to the dopamine D1 receptor (DRD1), promoting NLRP3 ubiquitination and degradation via E3ubiquitin ligase. Additionally, deletion of DRD1 in MPTP-treated mice exacerbates dopaminergic neuronal damage due to enhanced NLRP3 expression [84]. Dopamine D2 receptor signaling in astrocytes similarly inhibits NLRP3 activation through β-arrestin-2 pathways [85]. Collectively, these findings indicate a bidirectional regulatory relationship between dopamine and NLRP3 inflammasome activity. Rotenone, a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor and environmental risk factor for PD, induces bioenergetic deficits that intensify NLRP3 signaling and promote dopaminergic neuronal death [11,86]. Rotenone treated wild-type mice exhibit increased serum cytokine levels, which was not observed in NLRP3 knockout mice. Similarly, brain samples of mice treated with rotenone showed NLRP3-dependent inflammation and nigral damage, while NLRP3 knockout mice showed neuroprotection [41,87]. Collectively, these findings identify NLRP3 as a key mediator of dopaminergic neurodegeneration driven by α-synuclein pathology, mitochondrial toxins, and inflammatory stress, supporting its relevance as a therapeutic target in PD.

However, it is important to note the limitations of the MPTP and rotenone models. Although these models robustly reproduce mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic neurotoxicity, they do not fully capture the complex, multifactorial nature of sporadic PD, including progressive α-synuclein aggregation, widespread non-dopaminergic pathology, or long-term disease evolution [88,89]. Moreover, their acute or subacute toxin-based mechanisms may not accurately reflect the chronic, idiopathic origins of PD in humans.

In addition, data from human tissues and human-induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neuronal models remain comparatively limited. Incorporating findings from post-mortem human PD brains and human iPSC-based systems—particularly those modeling patient-specific genetics, mitochondrial defects, and inflammatory responses—would significantly enhance the translational relevance of NLRP3-related mechanisms and better bridge the gap between experimental models and human disease pathology [90,91]. Furthermore, the practical utility of proposed biomarkers such as circulating mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) requires more cautious interpretation. While increased plasma mtDNA is often suggested as an indicator of impaired mitophagy or mitochondrial damage in PD, elevated mtDNA can also arise from non-specific systemic cellular stress, inflammation, or peripheral tissue injury [92]. Thus, mtDNA levels alone may not reliably distinguish PD-related mitophagy defects from generalized stress responses, underscoring the need for more specific and context-validated biomarkers.

4. General View of Autophagy and Its Activation

Autophagy is an evolutionarily preserved intracellular catabolic process through which cytosolic cargo, including aged or damaged organelles and aggregated proteins, are degraded via the lysosome-targeted pathways [93]. This system enables the recycling of cellular constituents to withstand metabolism under stress conditions such as nutrient deprivation, organelle deterioration, or pathogen infection, thereby preserving cellular homeostasis [30,94]. Morphologically, autophagy is characterized by the formation of bi-membraned vesicles, termed autophagosomes, which sequester cytoplasmic cargo and subsequently fuse with lysosomes (in mammalian cells) or vacuoles (in fungi). Within lysosomes, acidic hydrolases degrade the autophagic bodies, and release metabolites such as amino acids, sugars, and lipids back into the cytoplasm for reuse [95].

Autophagy comprises three main major types: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Macroautophagy, most often referred to as autophagy, involves autophagosomes formation, whereas macroautophagy involves the direct engulfment of cytosolic constituents by lysosomes or endosomes. CMA, different from the other two types, specifically targets proteins containing KFERQ-like motif, which are recognized by the cytosolic chaperone Hsc70 and translocated into lysosomes via the LAMP2A receptor for degradation [96]. The autophagic process consists of a series of molecular stages beginning with the formation of the phagophore (pre-autophagosomal structure), which derives membranes from multiple cellular organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi, endosomes, and cytosolic membrane, although the precise origin in mammalian cells remains debated [97]. The phagophore expands into a double-membraned autophagosome, which subsequently fuses with lysosomes to form autolysosomes where cargo degradation occurs [98].

Autophagy initiation is regulated by the ULK1 complex (ULK1, ULK2, ATG13, FIP200, ATG101), whose activity is suppressed by mTORC1 under nutrient-rich conditions. Vesicle nucleation is mediated by the class III PI3K complex (VPS34/PIK3C3, ATG14, UVRAG/p63, AMBRA1, Beclin1), which is negatively regulated by BCL-1 and BCL-xL through interaction with Beclin1′s BH3 domain [99,100]. Vesicle elongation involves two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: ATG7 and ATG10 mediate ATG5–ATG12 conjugation to form a complex with ATG16L, while ATG7 also facilitates the lipidation of LC3-I to LC3-II, a process catalyzed by ATG4, ATG7, and ATG10 [101]. In selective autophagy, adaptor protein such as p62/SQSTM1 link ubiquitinated cargo to LC3-II on the phagophore membrane. Fusion of mature autophagosomes with lysosomes is mediated by the SNARE protein syntaxin-17 (STX17), enabling cargo degradation and the recycling of metabolites back into the cytoplasm [102,103].

Among autophagy subtypes, mitophagy—the selective clearance of damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria—is particularly important in maintaining mitochondrial quality control and neuronal health [104]. In PD, mitochondrial dysfunction appears as an early and persistent pathological hallmark, and impaired mitophagy disrupts mitochondrial dynamics, leading to the accumulation of defective mitochondria [54]. This accumulation increases oxidative stress, thereby directly affecting neuronal vulnerability and contributing to progressive neurodegeneration. Importantly, damaged mitochondria that fails to be efficiently cleared release mitochondrial DAMPs such as ROS, providing a mechanistic bridge between impaired mitophagy and aberrant activation of the NLRP3 inflammasomes in PD [105].

5. Mitophagy-Mediated Control of Mitochondrial Homeostasis and NLRP3 Inflammasomes Regulation

Both mitophagy and the NLRP3 inflammasome, rather than acting independently, cross-regulate each other in a context and time dependent manner, either protecting neurons or terminating inflammasome signaling. In PD, this bidirectional regulation becomes more relevant, as excessive inflammasome activation and impaired mitophagy synergistically contribute to neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neuron loss.

5.1. Mitophagy

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that play a central role in maintaining cytoplasmic homeostasis. They produce essential biosynthetic intermediates and serve as key regulators of cellular metabolism, autophagy, and apoptosis [106]. Various mitochondrial complex I inhibitors, endogenous danger signals, and environmental stressors can induces excessive ROS generation, leading to mtDNA dysfunction, which has been shown to positively regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation [43,107]. Mitophagy, a selective form of autophagy, mediates the removal of damaged mitochondria, thereby reducing ROS accumulation and limiting the release of mitochondrial DAMPs that triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation [108]. Thus, efficient mitophagy serves as a checkpoint for inflammasome signaling.

Importantly, impaired mitophagy leads to accumulation of mitochondrial DAMPs such as oxidized mtDNA and cardiolipin, which accumulate in the cytosol and directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade [109]. Oxidized mtDNA binds the NLRP3, NACHT, and LRR domains to stabilize inflammasome assembly, while cardiolipin translocate to the outer mitochondrial membrane under stress and promotes NLRP3 recruitment and oligomerization [110]. Failure to clear these signals sustains NLRP3 activation, enhances IL-1β and IL-18 maturation, and perpetuates neuroinflammatory signaling.

5.1.1. PINK1 and Parkin-Dependent Mitophagy

A diverse array of molecular mechanisms mediates mitophagy, among which the PINK1/Parkin-dependent pathway is the most extensively studied [111]. This post-translational signaling cascade selectively identifies and eliminates damaged mitochondria via a ubiquitin-dependent degradation route [112]. Under stressful conditions, mitochondrial depolarize, leading to accumulation of PINK1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) which in turn activates the cytosolic E3 ubiquitin ligase. Activated Parkin ubiquitinates several OMM proteins, including VDAC1 and Mfn2, via a feed-forward amplification loop that promotes mitochondrial tagging. These ubiquitinated mitochondria are recognized by autophagic adaptors such as optineurin (OPTN), neural dot protein 52 kDa (NDP52), and p62, which fuse them to LC3-positive autophagosomal membranes [113,114,115]. Finally, the autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes for degradation, completing the mitophagy cycle.

Studies in post-mortem PD human brains has shown discrete populations of phosphorylated ubiquitin (p-Ub) structures within the mitochondrial clusters colocalized with the lysosome, indicating a blockage in autophagic flux [116]. These p-Ub positive structures accumulate in an age-and Braak stage- dependent manner, suggesting an age-dependent impairment of mitophagy with disease progression. Mutations in PINK1 or PARK2 (Parkin) impair mitochondrial turnover, leading to accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and augment ROS production and loss of dopaminergic neurons [117,118,119]. Thus, timely removal of damaged mitochondria via PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy is critical for neuronal survival and represents a potential therapeutic intervention to curb inflammasome-mediated neurotoxicity.

5.1.2. Parkin-Independent and Receptor-Mediated Mitophagy

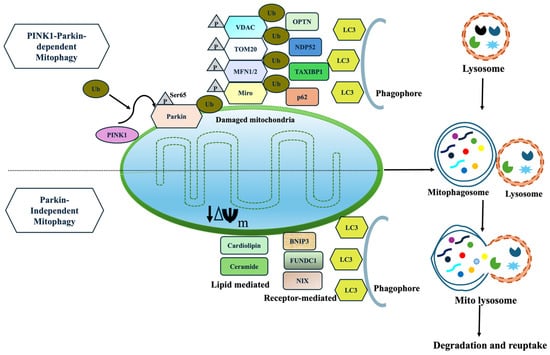

Beyond canonical Parkin-dependent mitophagy, receptor-mediated pathways provide alternative mechanisms for mitochondrial clearance. These pathways involve modulation of mitochondrial fission and fusion dynamics, primarily by inhibiting OPA1 and activation of Drp-1, facilitating mitochondrial fragmentation [120]. OMM proteins such as BNIP3, NIX, and FUNDC1 linked damaged mitochondria to autophagic machinery [121]. Under mitochondrial depolarization, USP19 and PGAM5 mediate FUNDC1 dephosphorylation, which enhances Drp1-dependent mitophagy [122]. Additional regulators such as AMBRA1 stabilize PINK1 and recruit alternative E3 ligases such as ARIH1, SIAH1, and HUWE1 to promote mitophagy [123]. Impaired mitochondrial fission or defective AMBRA1-mediated ubiquitination augment mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to uncontrolled oxidative stress, α-synuclein accumulation, and dopaminergic neuronal death [54]. Targeting these Parkin-independent pathways may therefore offer novel insights to restore mitochondrial homeostasis and slow neurodegeneration in PD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(i) Parkin-dependent mitophagy is initiated when mitochondria lose its membrane potential. PINK1 accumulates on the OMM, leading to phosphorylation (Ser65) and ubiquitination of Parkin, further recruiting and ubiquitinating widespread OMM proteins, including MFN1/2, VDAC, Tom20, and Miro. These OMM proteins are recognized by autophagy receptors (OPTN, NDP52), then link ubiquitinated mitochondria to LC3 and drive autophagosome formation and degradation. (ii) Parkin-independent mitophagy proceeds without Parkin through (a) receptor-mediated pathways (FUNDC1, AMBRA1, BNIP3/NIX) and (b) lipid-mediated signals (cardiolipin, ceramide). These inner and outer membrane proteins contain LC3-interacting region (LIR) motifs that allow direct binding to LC3 for degradation.

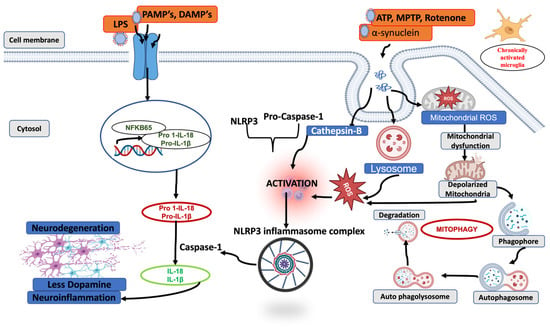

Both Parkin-mediated and receptor-mediated mitophagy play essential roles in maintaining mitochondrial turnover, limiting ROS production, and preventing accumulation of harmful DAMPS (ATP, mtDNA α-synuclein). Impaired mitophagy results in excessive ROS generation, NLRP3 redistribution, and amplification of inflammatory signaling. This in turn aggravates mitochondrial damage and activates caspase-1 activity, along with the activation of IL-1β and IL-18, causing pyroptosis (Figure 3). Several pharmacological agents have been identified to mitigate neuroinflammation in PD by enhancing mitophagy and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Neurotoxic prion peptide rP106-126 activates NLRP3 inflammasome and negatively regulates autophagy [124]. Andrographolide promotes Parkin-dependent mitophagy, effectively reducing NLRP3-mediated inflammation in both in vitro and MPTP-induced PD models [125]. Similar findings were shown where Urolithin promotes mitophagy and suppresses NLRP3 activity in LPS-induced BV2 microglia and the MPTP model of PD [126]. Cycloastragenol also reduces microglial NLRP3 activity in the PD model by promoting autophagy [127]. Pramipexole inhibited astrocytic NLRP3 inflammasome activation via Drd3-dependent autophagy in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease [128]. Palmatine ameliorates dopaminergic neurodegeneration by regulating NLRP3 through mitophagy [129]. Collectively, these findings highlight autophagy/mitophagy-inducing compounds as promising therapeutic strategies for targeting neuroinflammation in PD.

Figure 3.

A schematic representation of the interplay between impaired mitophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The figure illustrates how defects in mitochondrial quality control led to the accumulation of damaged or depolarized mitochondria, resulting in excessive release of mitochondrial danger signals. These signals enhance NLRP3 inflammasome priming and activation, promoting ASC assembly and caspase-1 activation. Activated caspase-1 cleaves pro–IL-1β and pro–IL-18 into their mature forms, driving downstream neuroinflammation and contributing to progressive neurodegeneration.

5.2. Direct Degradation of Inflammasomes Through Autophagy

Compelling evidence links NLRP3 inflammasome overactivation in microglia to PD pathology across patient samples, animal models, and in vitro systems [107,130,131]. Under physiological conditions, microglia act as surveillance cells, clearing misfolded protein aggregates and damaged neurons while maintaining brain homeostasis. However, chronic microglial activation leads to excessive production of IL-6 and TNF-α, along with mature IL-1β and IL-18 through NLRP3 dependent pathway. Autophagy provides a critical break on this inflammatory cascade by directly degrading active inflammasome components. Studies demonstrate the co-localization of NLRP3 inflammasome components with the autophagic marker LC3, facilitating inflammasome clearance and limiting cytokine release. Qin et Al. have shown that a microglial-specific knockout of Atg5 enhances NLRP3 activation and accelerates dopaminergic neuron death in a MPTP model of PD [132]. Moreover, a p38–TFEB axis have introduced shown to inhibit chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA)-dependent degradation of NLRP3 in α-synuclein A53T transgenic mice promoting inflammasome activation [133]. Thus, autophagic degradation of NLRP3 represents a plausible therapeutic strategy to interrupt early form of neuroinflammatory cascades in PD.

6. Drug Targets

6.1. Autophagy/Mitophagy Enhancers

Enhancing autophagy and mitophagy has emerged as a promising neuroprotective strategy in PD, aiming to mitigate α-synuclein aggregation, improve mitochondrial function, and reduce neuroinflammation. Several pharmacological agents have been identified that activate autophagic pathways, offering potential therapeutic avenues, as listed in Table 1. These compounds have consistently demonstrated that enhancement of autophagy/mitophagy improves neuronal survival, preserves mitochondrial integrity, and attenuates inflammatory responses in cellular and animal models of PD. However, most autophagy and mitophagy-inducing agents have not progressed beyond preclinical evaluation in PD due to poor blood–brain barrier penetration, dose-limiting toxicity, and pleiotropic systemic effects. Furthermore, the lack of PD-specific clinical trials and ongoing safety concerns underscore the need for next-generation autophagy/mitophagy modulators with improved specificity, enhanced brain penetrance, and controllable activity.

Table 1.

Summary of pharmacological agents that enhance autophagy, detailing their mechanistic evidence (in vitro and in vivo), stage of development, and key limitations relevant to PD. Arrows indicate direction of effects: ↑, increase; ↓, decrease; →, mechanistic linkage.

6.2. NLRP3 Inhibitors

Several NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors have been identified that can effectively suppress neuroinflammation in PD by directly blocking NLRP3 activation, preventing its oligomerization, or inhibiting downstream cytokine production such as IL-1β, IL-18, and active Caspase-1. Some of them are summarized in Table 2, with their mechanistic mechanism. Preclinically, all these compounds consistently demonstrate strong inhibition of NLRP3 signaling, reduce microglial activation, attenuate pyroptosis, preserve nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons, and improve motor outcomes. However, despite robust anti-inflammatory efficacy in vitro and in vivo, clinical translation remains limited. Only a small subset of NLRP3 inhibitors, such as MCC950 and dapansutrile (OLT1177), have advanced to clinical trials, and none have yet been approved for PD. Major obstacles include hepatotoxicity (e.g., MCC950), insufficient blood–brain barrier penetration, off-target immunosuppression, metabolic liabilities, and the absence of PD-specific clinical trial data for most compounds.

Table 2.

Summary of pharmacological agents targeting NLRP3 inflammasome activation, detailing mechanistic evidence (in vitro and in vivo studies), stage of development, and key limitations relevant to PD. The arrow (→) denotes downstream signaling or mechanistic linkage.

6.3. Dual Modulation

Studies have suggested that simultaneous targeting of mitophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome activation offers a beneficial outcome in the pre-clinical model of PD. Impaired mitophagy leads to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, excessive ROS generation, and subsequent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Therefore, pharmacological agents or interventions that enhance mitophagy while concurrently suppressing NLRP3 activation may synergistically reduce neuroinflammation. Some studies have demonstrated the additive or synergistic neuroprotective effects of such dual modulators are listed below (Table 3). Overall, these dual-modulator strategies exemplify how targeting both upstream triggers (damaged mitochondria) and downstream effectors (inflammasome activation) can achieve synergistic neuroprotection, highlighting the therapeutic potential of integrated approaches in PD.

Table 3.

Summary of dual modulators targeting autophagy/mitophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways, detailing its mechanistic rationale and experimental evidence (in vitro and in vivo studies). The arrow (→) denotes downstream signaling or mechanistic linkage.

6.4. Drugs in Clinical Trials

Below is a summary of some clinical-trial agents that either modulate NLRP3 inflammasomes’ activity or enhance autophagy/mitophagy in PD, as listed in Table 4. Several compounds have advanced into early-phase clinical trials, reflecting growing translational interest in modulating these mechanisms to slow disease progression. However, challenges remain, including defining optimal patient stratification, treatment timing, long-term safety, and reliable biomarkers of target engagement and disease modification.

Table 4.

Summary of compounds targeting NLRP3 inflammasome or autophagy/mitophagy pathways in PD detailing developmental stage and its key outcomes.

7. Limitations of Current Therapeutic Strategies

Despite significant advances achieved in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying PD, several limitations remain in translating NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors and autophagy/mitophagy modulators into effective clinical therapies. Although several IL-1β–targeted therapies, such as anakinra, canakinumab, and rilonacept, have shown efficacy in various neuroinflammatory diseases, no clinical trials in PD or other neurodegenerative disorders have been reported, mainly due to poor blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability and limited therapeutic efficacy [168]. Moreover, since IL-1β can also be produced via inflammasome-independent pathways, blocking it directly may lead to undesired immunosuppression [25].

Other NLRP3 inhibitors, such as MCC950, β-hydroxybutyrate, Bay 11-7082, and Ac-YVAD-CMK, have shown promising anti-inflammatory effects in vitro and in pre-clinical PD models. However, these compounds remain largely off target, exhibit low potency, poor BBB permeability, and short biological half-lives and lack human trail data [169,170]. In addition, inhibitors such as MCC950 and β-hydroxybutyrate have serious long-term adverse effects, including hepatotoxicity, metabolic disturbances and off-target immune modulation, which significantly hinder their translational potential [171]. Another drawback of these NLRP3 inhibitors is that prolonged suppression of NLRP3 activity may impair physiological immune responses, thereby increasing vulnerability to infections and diminishing normal tissue repair processes, which highlights an important long-term safety concern [172]. Additionally, IL-18 and other pro-inflammatory mediators involved in PD pathology still lack specific inhibitors [173]. Collectively, these limitations raise safety and translational concern prompting an urgent need for novel therapeutics targeting upstream regulators of NLRP3 activation that can effectively cross the BBB and modulate neuroinflammation in PD.

Similarly, enhancing mitophagy through pharmacological agents such as PINK1/Parkin activators (e.g., spermidine, urolithin A), mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin), NAD+ precursors, and AMPK/SIRT1 activators has demonstrated neuroprotective effect in preclinical PD models, including improved mitochondrial quality control, reduced neuroinflammation, and preservation of dopaminergic neurons [113,174,175]. However, several unresolved challenges remain. Both excessive and insufficient mitophagy can be detrimental, making its regulation a double-edged sword for neuronal survival [104,176]. Although many studies advocate the benefits of mitophagy enhancement, increasing mitophagic flux is not always therapeutically beneficial and may exacerbate mitochondrial stress under certain pathological conditions [176]. Therefore, mitophagy offers therapeutic benefits; however, precise modulation, rather than indiscriminate activation, is essential to achieve neuroprotection.

Furthermore, a more in-depth mechanism of mitophagy must be elucidated, showing that its interconnection with different mitophagy pathways is required. Untangling the multifaceted roles of mitophagy in neuronal survival and death is needed, and mitophagy can be both beneficial and detrimental for the neuronal bioenergetics depending on the pathological condition. Since mitochondria are highly dynamic, the precise stage of mitochondrial morphology (fusion and fission) must be determined to develop mitophagy inducers [177]. Moreover, the development of specific, potent, and low-toxicity mitophagy inducers with demonstrable clinical benefits is still a missing linkage [178,179]. The dual role of mitophagy in promoting both cell survival and death, together with the poor specificity and safety profile of current inducers and lack of reliable in vivo markers to monitor mitophagy, further complicate the current therapy [180,181].

8. Conclusions

Several studies have highlighted the critical role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and defective mitophagy as key drivers for neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in PD. Dysregulated mitochondrial quality control promotes the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and releases DAMP’s, which, in turn, amplify NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and sustain neuroinflammatory cascades. Consequently, targeting the inflammasome–mitophagy axis, either individually or in combination, emerges as a compelling therapeutic strategy for slowing PD progression.

Despite promising preclinical outcomes, the clinical translation aimed to target NLRP3 inflammasome activity and autophagy/mitophagy in PD remains highly challenging. Major barriers include an incomplete understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms, poor blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability of current agents, limited target specificity, off-target toxicities, and inconclusive clinical outcomes. Moreover, indiscriminate inhibition of NLRP3 or excessive mitophagy may disrupt physiological immune responses and mitochondrial homeostasis, underscoring the need for precise and context-dependent modulation. These challenges highlight the need for more refined and targeted therapeutic strategies to safely harness the neuroprotective potential of inflammasome–mitophagy regulation in PD.

9. Future Perspectives

Future research should prioritize elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms that link mitophagy dysfunction to NLRP3 inflammasome activation in PD models. A deeper understanding of upstream regulatory mechanisms—such as post-translational modifications and specific phosphorylation sites governing NLRP3 activation—may enable the development of highly specific therapeutic interventions with reduced off-target effects [182,183]. In parallel, structure–activity relationship (SAR)-based optimization, comprehensive pharmacokinetic profiling, and rigorously designed clinical trials will be essential to establish the safety and efficacy of inflammasome- and mitophagy-targeted therapies.

A critical gap lies in the lack of robust, clinically translatable biomarkers capable of monitoring mitophagy and inflammasome activity in vivo. Conventional techniques such as [18F]-FDG PET and fMRI primarily assess glucose metabolism and functional connectivity, offering only indirect and non-specific information about mitophagy and inflammasome activity [184]. Instead, newer radiopharmaceuticals techniques, such as second-generation TSPO ligand, could provide a direct way to trace activated microglia and neuroinflammatory process in vivo. However, their interpretation is challenging, because TSPO expression is not specific to the microglial phenotype, and cellular heterogeneity impairs signal outcome. Another major gap that needs to be addressed is the disconnect between molecular mechanisms and clinically measurable parameters. For example, circulating cell-free mtDNA may reflect impaired mitophagy, but its relationship to neuronal mitophagy remains unsolved. Bridging this gap will require the development of integrated biomarker panels that combine cytokine profiling, circulating cell-free mtDNA, TSPO-based PET imaging, and next-generation mitochondrial PET tracers.

Advanced techniques, including phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy and mitochondrial-PET tracers, may allow real-time visualization and assessment of mitochondrial dynamics without triggering excessive mitophagy or energy depletion [185]. Additionally, the combination of therapeutic strategies that simultaneously inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation, promote controlled mitophagy, and exhibit better BBB-penetrating ability may provide superior potential by targeting both upstream pathogenic triggers and downstream inflammatory cascades [186]. Ultimately, integrating mechanistic insights with innovative therapeutic and biomarker development will be crucial for translating inflammasome mitophagy-based strategies into effective clinical interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A., T.P. and F.A.; validation, S.A., T.P. and F.A.; investigation, S.A.; resources, S.A., T.P. and F.A.; data curation, S.A., T.P. and F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A., T.P. and F.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A. and T.P.; visualization, S.A., T.P. and F.A.; supervision, S.A.; project administration, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| SNpc | Substantia Nigra Par Compacta |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| HLA-DR | Human Leukocyte Antigen-D-Related |

| DAMPS | Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta) |

| Il-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR-, and Pyrin Domain-Containing Protein 3 |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine |

| PYHIN/HIN | Hematopoietic Interferon-Inducible Nuclear |

| AIM2 | Absent in Melanoma 2 |

| IFI16 | Interferon-Gamma Inducible Protein 16 |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| NACHT | Nucleotide-Binding |

| LRR | Leucine Rich Repeats |

| CARD | Caspase Recruitment Domain |

| TLR | Toll-like Receptor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase 1 |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| CMA | Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy |

| LAMP2A | Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 2 |

| ULK1 | Unc-51-Like Autophagy Activating Kinase 1 |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| LC3I | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| ATG | Autophagy-Related |

| SQSTM1 | Sequestosome 1 |

| PINK1 | PTEN-Induced Putative Kinase 1 |

| OMM | Outer Mitochondrial Membrane |

| OPTN | Optineurin |

| FUNDC1 | FUN14 Domain Containing 1 |

| OPA1 | Optic Atrophy 1 |

| BNIP3 | Bcl-2/Adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-Interacting Protein 3 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| TSPO | Translocator Protein |

References

- Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Darweesh, S.; Llibre-Guerra, J.; Marras, C.; San Luciano, M.; Tanner, C. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2024, 403, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Dong, W.; Liu, J.; Yin, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, M. Disease burden of Parkinson’s disease in China and its provinces from 1990 to 2021: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2024, 46, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.A.; Romero-Ramos, M. Microglia response during Parkinson’s Disease: Alpha-synuclein intervention. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Guo, D.; Wei, J. The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and crosstalk with other diseases. Biocell 2024, 48, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M.; Small, G.W.; Isaacson, S.H.; Torres-Yaghi, Y.; Pagan, F.; Pahwa, R. Unmet needs in the diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson’s disease psychosis and dementia-related psychosis. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2023, 27, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leak, R.K.; Clark, R.N.; Abbas, M.; Xu, F.; Brodsky, J.L.; Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Luk, K.C. Current insights and assumptions on α-synuclein in Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runwal, G.; Edwards, R.H. The membrane interactions of synuclein: Physiology and pathology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2021, 16, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabresi, P.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Marino, G.; Campanelli, F.; Ghiglieri, V. Advances in understanding the function of alpha-synuclein: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2023, 146, 3587–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Santoro, A.; Monti, D.; Crupi, R.; Di Paola, R.; Latteri, S.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Zappia, M.; Giordano, J.; Calabrese, E.J. Aging and Parkinson’s disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 115, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, L.; Mannino, D.; Filippone, A.; Romano, A.; Esposito, E.; Paterniti, I. The role of autophagy in Parkinson’s disease: A gender difference overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1408152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Malovic, E.; Harishchandra, D.S.; Ghaisas, S.; Panicker, N.; Charli, A.; Palanisamy, B.N.; Rokad, D.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V. Mitochondrial impairment in microglia amplifies NLRP3 inflammasome proinflammatory signaling in cell culture and animal models of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2017, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yin, D.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, L. The immunology of Parkinson’s disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodveldt, C.; Bernardino, L.; Oztop-Cakmak, O.; Dragic, M.; Fladmark, K.E.; Ertan, S.; Aktas, B.; Pita, C.; Ciglar, L.; Garraux, G. The immune system in Parkinson’s disease: What we know so far. Brain 2024, 147, 3306–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubrand, V.E.; Sepúlveda, M.R. New insights into the role of the endoplasmic reticulum in microglia. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1397–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Polis, B.; Jamwal, S.; Sanganahalli, B.G.; Kaswan, Z.M.; Islam, R.; Kim, D.; Bowers, C.; Giuliano, L.; Biederer, T. Transient impairment in microglial function causes sex-specific deficits in synaptic maturity and hippocampal function in mice exposed to early adversity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 122, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind-Holm Mogensen, F.; Seibler, P.; Grünewald, A.; Michelucci, A. Microglial dynamics and neuroinflammation in prodromal and early Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeer, P.; Itagaki, S.; Boyes, B.; McGeer, E. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 1988, 38, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, G.; Hutchinson, H.; Gonzalez, M.; Dagra, A. Central and Peripheral Immunity Responses in Parkinson’s Disease: An Overview and Update. Neuroglia 2025, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yin, D.; Ren, H.; Gao, W.; Li, F.; Sun, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Lyu, L.; Yang, M. Selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor reduces neuroinflammation and improves long-term neurological outcomes in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 117, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, M.G.; Wallings, R.L.; Houser, M.C.; Herrick, M.K.; Keating, C.E.; Joers, V. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Polis, B.; Kaffman, A. Microglia: The Drunken Gardeners of Early Adversity. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Y.; Tian, M.; Deng, S.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Gao, J.; Pei, X.; Wang, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhao, F. The key drivers of brain injury by systemic inflammatory responses after sepsis: Microglia and neuroinflammation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 1369–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, K.K.; Ahmed, S.; Wang, D.; Polis, B.; Islam, R.; Kaffman, A. Early life stress impairs synaptic pruning in the developing hippocampus. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 107, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-W.; Chen, C.-M.; Chang, K.-H. Biomarker of neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Creese, B.; Politis, M.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Weintraub, D.; Ballard, C. Cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Kwatra, M.; Gawali, B.; Panda, S.R.; Naidu, V. Potential role of TrkB agonist in neuronal survival by promoting CREB/BDNF and PI3K/Akt signaling in vitro and in vivo model of 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP)-induced neuronal death. Apoptosis 2021, 26, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaso, K. Roles of Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Yonago Acta Medica 2024, 67, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, W.; Sun, Y.; Wu, M. New insight on microglia activation in neurodegenerative diseases and therapeutics. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1308345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechushtai, L.; Frenkel, D.; Pinkas-Kramarski, R. Autophagy in Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, E.; Martinez-Vicente, M. The consequences of GBA deficiency in the autophagy–lysosome system in Parkinson’s disease associated with GBA. Cells 2023, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.S.; Moglad, E.; Afzal, M.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, G.; Sivaprasad, G.; Deorari, M.; Almalki, W.H.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I. Autophagy-associated non-coding RNAs: Unraveling their impact on Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, A.; Atilano, M.L.; Gergi, L.; Kinghorn, K.J. Lysosomal storage, impaired autophagy and innate immunity in Gaucher and Parkinson’s diseases: Insights for drug discovery. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20220381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usenko, T. Autophagy impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Approaches to therapy. Mol. Biol. 2025, 59, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Abraham, N.; Gao, G.; Yang, Q. Dysregulation of autophagy and mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, E.; Larsen, J. A review of MPTP-induced parkinsonism in adult zebrafish to explore pharmacological interventions for human Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1451845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antico, O.; Thompson, P.W.; Hertz, N.T.; Muqit, M.M.; Parton, L.E. Targeting mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Q.; Du, X.; Jiang, H. Targeting the Interplay Between Autophagy and the Nrf2 Pathway in Parkinson’s Disease with Potential Therapeutic Implications. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Domínguez, M. Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms, Dual Roles, and Therapeutic Strategies in Neurological Disorders. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, O.; Faizan, M.; Goswami, S.; Singh, M.P. An update on the involvement of inflammatory mediators in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 3527–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, S.; Herath, A.M.; Gordon, R. Inflammasome Activation in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, S113–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.N.; Nguyen, H.D.; Kim, Y.J.; Nguyen, T.T.; Lai, T.T.; Lee, Y.K.; Ma, H.-I.; Kim, Y.E. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in Parkinson’s disease and therapeutic considerations. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.-Q.; Le, W. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and related mitochondrial impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 39, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-H.; Liu, X.-D.; Jin, M.-H.; Sun, H.-N.; Kwon, T. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuronal pyroptosis and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 72, 1839–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, H.M.; Atef, E.; Elsayed, A.E. New Insights on the Potential Role of Pyroptosis in Parkinson’s Neuropathology and Therapeutic Targeting of NLRP3 Inflammasome with Recent Advances in Nanoparticle-Based miRNA Therapeutics. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 9365–9384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Revilla, J.; Herrera, A.J.; De Pablos, R.M.; Venero, J.L. Inflammatory animal models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, S165–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Vora, L.; Nathiya, D.; Khatri, D.K. Nrf2–Keap1 Pathway and NLRP3 Inflammasome in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanistic Crosstalk and Therapeutic Implications. Mol. Neurobiol. 2026, 63, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Habean, M.L.; Panicker, N. Inflammasome assembly in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera Ranaldi, E.d.R.; Nuytemans, K.; Martinez, A.; Luca, C.C.; Keane, R.W.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P. Proof-of-principle study of inflammasome signaling proteins as diagnostic biomarkers of the inflammatory response in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piancone, F.; La Rosa, F.; Marventano, I.; Saresella, M.; Clerici, M. The Role of the Inflammasome in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2021, 26, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Qian, L.; Luo, H.; Li, X.; Ruan, Y.; Fan, R.; Si, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. The Significance of NLRP Inflammasome in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y. Targeting NLRP3 inflammasome for neurodegenerative disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4512–4527, Correction in Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 28, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, F.M.; Cuenca-Bermejo, L.; Fernández-Villalba, E.; Costa, S.L.; Silva, V.D.A.; Herrero, M.T. Role of Microgliosis and NLRP3 Inflammasome in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 42, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Kuruvilla, J.; Tan, E.-K. Mitophagy and reactive oxygen species interplay in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Chen, Z.; Fan, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Jiang, B.; Long, H.; Zhong, W.; Li, X.; Li, Y. A selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor attenuates behavioral deficits and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 354, 577543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, A.M.; Machado, V.; Pagano, G.; Muelhardt, N.M.; Kustermann, T.; Mracsko, E.Z.; Brockmann, K.; Shariati, N.; Anzures-Cabrera, J.; Zinnhardt, B. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers of NLRP3 Pathway, Immune Dysregulation, and Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Mov. Disord. 2025. Available online: https://movementdisorders.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mds.70103 (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, R.; Siracusa, R.; Genovese, T.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Di Paola, R. Focus on the Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Sterling, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Song, W. The role of inflammasomes in human diseases and their potential as therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Núñez, G. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Activation and regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, X.; Escames, G.; Lei, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Jing, T.; Yao, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Contributions to inflammation-related diseases. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, N.; Luo, Y. Role of NLRP3 in Parkinson’s disease: Specific activation especially in dopaminergic neurons. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-Y.; Yuan, X.-L.; Jiang, J.-M.; Zhang, P.; Tan, K. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in Parkinson’s disease: From molecular mechanism to therapeutic strategy. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 386, 115167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Liu, Z.-S.; Xue, W.; Bai, Z.-F.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.-J.; Cai, H.; Zhan, X.-Y. NLRP3 phosphorylation is an essential priming event for inflammasome activation. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 185–197.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliana, C.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Kang, S.; Farias, A.; Qin, F.; Alnemri, E.S. Non-transcriptional Priming and Deubiquitination Regulate NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 36617–36622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, S.; Kim, J.K.; Shin, H.J.; Park, E.-J.; Kim, I.S.; Jo, E.-K. Updated insights into the molecular networks for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 563–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Tao, W.-Y.; Chen, X.-Y.; Jiang, C.; Di, B.; Xu, L.-L. Mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and the development of peptide inhibitors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2023, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, M.; Rikalovic, M.G. Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation Pathway in Parkinson’s Disease: Current Status and Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Cells 2022, 11, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.F.; Varanita, T.; Herrebout, M.A.; Plug, B.C.; Kole, J.; Musters, R.J.; Teunissen, C.E.; Hoozemans, J.J.; Bubacco, L.; Veerhuis, R. α-Synuclein evokes NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion from primary human microglia. Glia 2021, 69, 1413–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soraci, L.; Gambuzza, M.E.; Biscetti, L.; Laganà, P.; Lo Russo, C.; Buda, A.; Barresi, G.; Corsonello, A.; Lattanzio, F.; Lorello, G. Toll-like receptors and NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent pathways in Parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Yazdanpanah, N.; Rezaei, N. The role of Toll-like receptors and neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; O‘Connell, K.S.; Ueland, T.; Sheikh, M.A.; Agartz, I.; Andreou, D.; Aukrust, P.; Boye, B.; Bøen, E.; Drange, O.K. Increased circulating IL-18 levels in severe mental disorders indicate systemic inflammasome activation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 99, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alboni, S.; Tascedda, F.; Uezato, A.; Sugama, S.; Chen, Z.; Marcondes, M.C.G.; Conti, B. Interleukin 18 and the brain: Neuronal functions, neuronal survival and psycho-neuro-immunology during stress. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 3197–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J. Recent advances of the NLRP3 inflammasome in central nervous system disorders. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 9238290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Herrmann, K.M.; Salas, L.A.; Martinez, E.M.; Young, A.L.; Howard, J.M.; Feldman, M.S.; Christensen, B.C.; Wilkins, O.M.; Lee, S.L.; Hickey, W.F.; et al. NLRP3 expression in mesencephalic neurons and characterization of a rare NLRP3 polymorphism associated with decreased risk of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashia, P.; Cordella, A.; Nobili, A.; La Barbera, L.; Federici, M.; Leuti, A.; Campanelli, F.; Natale, G.; Marino, G.; Calabrese, V. Blunting neuroinflammation with resolvin D1 prevents early pathology in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3945, Correction in Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Venero, J.L.; Joseph, B.; Burguillos, M.A. Caspases orchestrate microglia instrumental functions. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 171, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Zhang, L.X.; Sun, X.Y.; Ding, J.H.; Lu, M.; Hu, G. Caspase-1 Deficiency Alleviates Dopaminergic Neuronal Death via Inhibiting Caspase-7/AIF Pathway in MPTP/p Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 4292–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Doseff, A.I.; Schmittgen, T.D. MicroRNAs Targeting Caspase-3 and -7 in PANC-1 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, H.; Ma, J.; Luo, S.; Chen, S.; Gu, Q. MicroRNA-30e regulates neuroinflammation in MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease by targeting Nlrp3. Hum. Cell 2018, 31, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, M.T.; Oertel, W.H.; Surmeier, D.J.; Geibl, F.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease—A key disease hallmark with therapeutic potential. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Ding, C.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, R. Dopamine controls systemic inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell 2015, 160, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Hu, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Q.; Ding, J.; Xiao, M.; Wang, C.; Lu, M.; Hu, G. Dopamine D2 receptor restricts astrocytic NLRP3 inflammasome activation via enhancing the interaction of β-arrestin2 and NLRP3. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Xu, H.-D.; Guan, J.-J.; Hou, Y.-S.; Gu, J.-H.; Zhen, X.-C.; Qin, Z.-H. Rotenone impairs autophagic flux and lysosomal functions in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 2015, 284, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, E.M.; Young, A.L.; Patankar, Y.R.; Berwin, B.L.; Wang, L.; von Herrmann, K.M.; Weier, J.M.; Havrda, M.C. Editor’s Highlight: Nlrp3 Is Required for Inflammatory Changes and Nigral Cell Loss Resulting from Chronic Intragastric Rotenone Exposure in Mice. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 2017, 159, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, M.; Salama, M.; Collins-Praino, L.E.; Baetu, I.; Fathalla, A.M.; Soliman, A.M.; Mohamed, W.; Moustafa, A.A. Neurotoxin-induced rodent models of Parkinson’s disease: Benefits and drawbacks. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 897–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunlu, Ö.; Topatan, E.; Al-yaqoobi, Z.; Burul, F.; Bayram, C.; Sezen, S.; Okkay, I.F.; Okkay, U.; Hacımüftüoğlu, A. Experimental Models in Parkinson’s Disease: Advantages and Disadvantages. Ağrı Tıp Fakültesi Derg. 2024, 2, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Tcw, J. Human iPSC-based modeling of central nerve system disorders for drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ai, X.; Cao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, D. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Derived Cellular Models for Investigating Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis and Drug Screening. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2025, 21, 1883–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gaetano, A.; Solodka, K.; Zanini, G.; Selleri, V.; Mattioli, A.V.; Nasi, M.; Pinti, M. Molecular mechanisms of mtDNA-mediated inflammation. Cells 2021, 10, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwatra, M.; Ahmed, S.; Gangipangi, V.K.; Panda, S.R.; Gupta, N.; Shantanu, P.; Gawali, B.; Naidu, V. Lipopolysaccharide exacerbates chronic restraint stress-induced neurobehavioral deficits: Mechanisms by redox imbalance, ASK1-related apoptosis, autophagic dysregulation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 144, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Watzlawik, J.O.; Fiesel, F.C.; Springer, W. Autophagy in Parkinson’s disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 2651–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minchev, D.; Kazakova, M.; Sarafian, V. Neuroinflammation and autophagy in Parkinson’s disease—Novel perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Debnath, J. Autophagy at the crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Matsui, T. Molecular mechanisms of macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 2024, 91, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, W.W.-Y.; Mizushima, N. Lysosome biology in autophagy. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, P.-Y. Molecular mechanism of autophagosome–lysosome fusion in mammalian cells. Cells 2024, 13, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, X. Ubiquitination in the regulation of autophagy: Ubiquitination in the regulation of autophagy. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2023, 55, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. Autophagy–lysosomal-associated neuronal death in neurodegenerative disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valionyte, E. Characterisation of Caspase-6-Dependent Regulatory Mechanisms of SQSTM1/p62 Droplet-Based Autophagy; University of Plymouth: Plymouth, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Blasiak, J.; Liton, P.; Boulton, M.; Klionsky, D.J.; Sinha, D. Autophagy in age-related macular degeneration. Autophagy 2023, 19, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpartida, A.B.; Williamson, M.; Narendra, D.P.; Wade-Martins, R.; Ryan, B.J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease: From mechanism to therapy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, F.; Ganley, I.G. Parkinson’s disease and mitophagy: An emerging role for LRRK2. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschopp, J.; Schroder, K. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: The convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Hwang, I.; Park, S.; Hong, S.; Hwang, B.; Cho, Y.; Son, J.; Yu, J.-W. MPTP-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia plays a central role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Cassel, S.L.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Dagvadorj, J. Regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by autophagy and mitophagy. Immunol. Rev. 2025, 329, e13410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, A.; Leonidas, L.; Macapagal, A.; Lee, H.; McNulty, R. How interactions between oxidized DNA and the NLRP3 inflammasome fuel inflammatory disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2025, 50, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.W.; Ordureau, A.; Heo, J.-M. Building and decoding ubiquitin chains for mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, K.; Bolshette, N.; Ahire, A.; Pardeshi, R.; Thakur, K.; Trandafir, C.; Istrate, A.; Ahmed, S.; Lahkar, M.; Muresanu, D.F. The ubiquitin proteasomal system: A potential target for the management of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 1392–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Li, R.; Yang, H. Mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease: From pathogenesis to treatment. Cells 2019, 8, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernie, F. Mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease: From pathogenesis to treatment target. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 138, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.C.; Holzbaur, E.L. Optineurin is an autophagy receptor for damaged mitochondria in parkin-mediated mitophagy that is disrupted by an ALS-linked mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4439–E4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Fiesel, F.C.; Truban, D.; Castanedes Casey, M.; Lin, W.-l.; Soto, A.I.; Tacik, P.; Rousseau, L.G.; Diehl, N.N.; Heckman, M.G. Age-and disease-dependent increase of the mitophagy marker phospho-ubiquitin in normal aging and Lewy body disease. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1404–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.E.; Dodson, M.W.; Jiang, C.; Cao, J.H.; Huh, J.R.; Seol, J.H.; Yoo, S.J.; Hay, B.A.; Guo, M. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature 2006, 441, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, V.A.; Haddad, D.; Craessaerts, K.; De Bock, P.-J.; Swerts, J.; Vilain, S.; Aerts, L.; Overbergh, L.; Grünewald, A.; Seibler, P. PINK1 loss-of-function mutations affect mitochondrial complex I activity via NdufA10 ubiquinone uncoupling. Science 2014, 344, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, E.M.; Abou-Sleiman, P.M.; Caputo, V.; Muqit, M.M.; Harvey, K.; Gispert, S.; Ali, Z.; Del Turco, D.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Healy, D.G. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 2004, 304, 1158–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]