Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Cell- and State-Specific Alternative Splicing in 293T and A549 Cell Transcriptomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Full-Length Transcriptome Profiles of 293T and A549 Cells

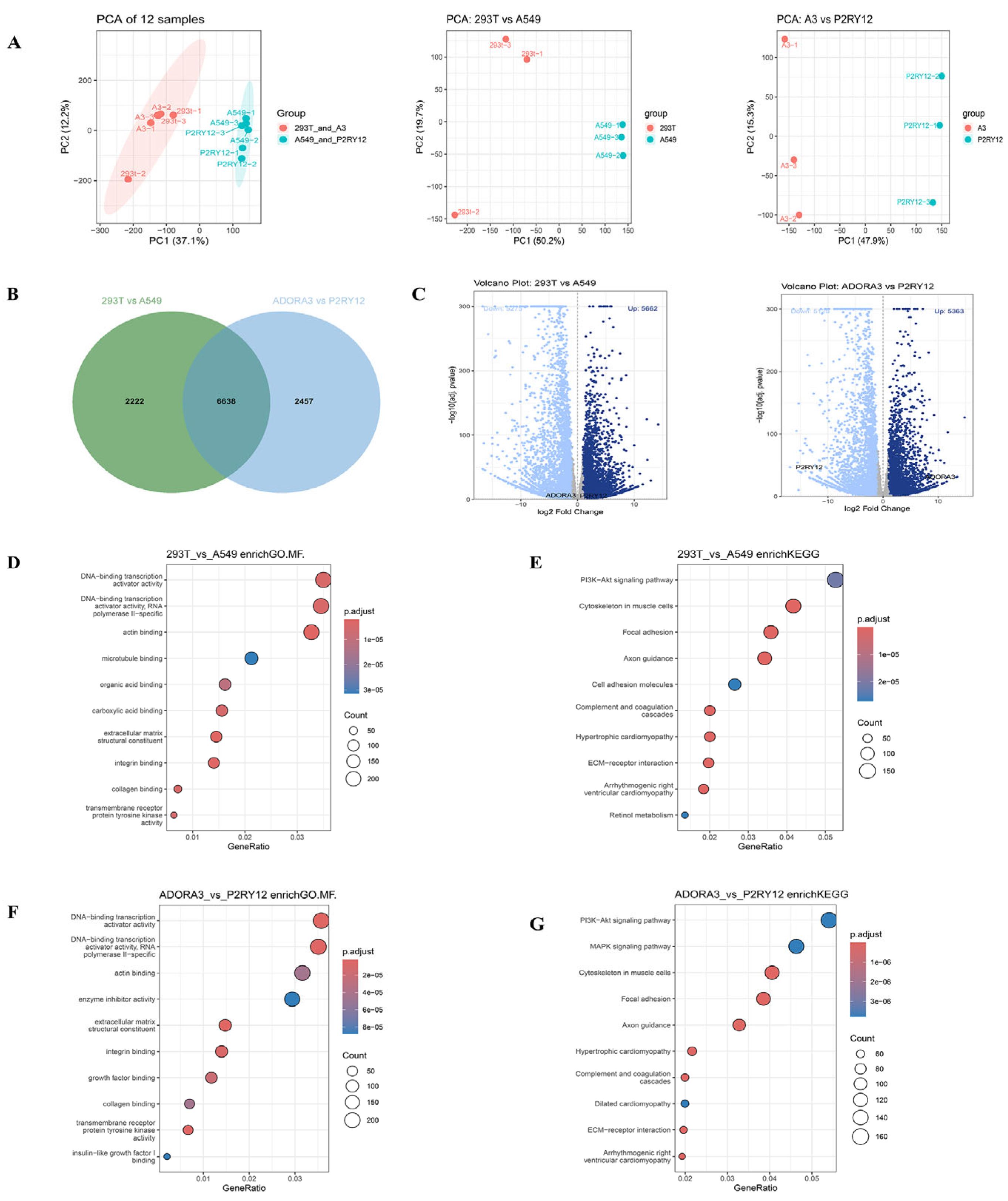

2.2. Transcriptome Expression Under Overexpression Intervention

2.3. Functional Changes Under Overexpression Intervention

2.4. Alternative Splicing Events Under Overexpression Intervention

2.5. IGV Visualization of Alignment Data Uncovered Differences in Gene Expression and Splicing Regulation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Sequencing and Quality Control

4.3. Short-Read RNA Sequencing and Analysis

4.4. Isoform Reconstruction and Classification with FLAIR and SQANTI3

4.5. Alternative Splicing Identification and Differential Analysis

4.6. Differentially Expressed Genes and Differential Transcript Usage Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Alternative splicing |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptors |

| SR | Serine- and arginine-rich |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| gDTUs | Genes with differential transcript usage |

| FSM | Full-splice matches |

| ISM | Incomplete-splice match |

| NNC | Novel not in catalog |

| NIC | Novel in catalog |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| CC | Cellular component |

| BP | Biological process |

| MF | Molecular function |

| FLAIR | Full-length alternative isoform analysis of RNA |

| SE | Skipping exons |

| A5 | Alternative 5′ splice site |

| A3 | Alternative 3′ splice site |

| MX | Mutually exclusive exon |

| RI | Retained intron |

| AF | Alternative first exon |

| AL | Alternative last exon |

| RBP | RNA-binding protein |

References

- Cui, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, R.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Lin, P.; Guo, B.; Sun, S.; Zhao, X. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing in stem cell function and therapeutic potential: A critical review of current evidence. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarca, A.; Perez, C.; van den Bor, J.; Bebelman, J.P.; Heuninck, J.; de Jonker, R.J.F.; Durroux, T.; Vischer, H.F.; Siderius, M.; Smit, M.J. Differential Involvement of ACKR3 C-Tail in β-Arrestin Recruitment, Trafficking and Internalization. Cells 2021, 10, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, L.; Porter, J.J.; Lueck, J.D.; Orlandi, C. G(z)ESTY as an optimized cell-based assay for initial steps in GPCR deorphanization. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Wu, M.; Mo, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, G.; Leng, L.; Zhang, S. Alterations in Gene Expression and Alternative Splicing Induced by Plasmid-Mediated Overexpression of GFP and P2RY12 Within the A549 Cell Line. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Tian, X.; Mo, J.; Leng, L.; Wang, C.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S.; Xie, J. Transduction of Lentiviral Vectors and ADORA3 in HEK293T Cells Modulated in Gene Expression and Alternative Splicing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Cen, J.; Zhu, Z. Lentivirus-Mediated RNA Interference Targeting Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Enhances the Sensitivity of K562 Cells to Imatinib. Blood 2008, 112, 4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Liu, F.C.; Pan, C.H.; Lai, M.T.; Lan, S.J.; Wu, C.H.; Sheu, M.J. Suppression of Cell Growth, Migration and Drug Resistance by Ethanolic Extract of Antrodia cinnamomea in Human Lung Cancer A549 Cells and C57BL/6J Allograft Tumor Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, S.K.; Castanho, I.; Jeffries, A.; Moore, K.; Dempster, E.L.; Brown, J.T.; Bamford, R.A.; Hannon, E.J.; Mill, J. Isoform characterisation & splicing signatures of AD-risk genes using long-read sequencing. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e074237. [Google Scholar]

- Monzó, C.; Liu, T.; Conesa, A. Transcriptomics in the era of long-read sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025, 26, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, L. Alternative splicing: Human disease and quantitative analysis from high-throughput sequencing. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.H.; Landback, P.; Arsala, D.; Guzzetta, A.; Xia, S.; Atlas, J.; Sosa, D.; Zhang, Y.E.; Cheng, J.; Shen, B.; et al. Evolutionarily new genes in humans with disease phenotypes reveal functional enrichment patterns shaped by adaptive innovation and sexual selection. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Chen, C.; Shen, H.; He, B.Z.; Yu, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, S.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. GenTree, an integrated resource for analyzing the evolution and function of primate-specific coding genes. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.E.; Vibranovski, M.D.; Landback, P.; Marais, G.A.; Long, M. Chromosomal redistribution of male-biased genes in mammalian evolution with two bursts of gene gain on the X chromosome. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Cho, N.; Kim, K.K. The implications of alternative pre-mRNA splicing in cell signal transduction. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Bruford, M.W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Gu, Z.; Hou, X.; Deng, X.; Dixon, A.; Graves, J.A.M.; Zhan, X. Transcription-Associated Mutation Promotes RNA Complexity in Highly Expressed Genes—A Major New Source of Selectable Variation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.T.; Sandberg, R.; Luo, S. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W. Why genes in pieces? Nature 1978, 271, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, H.; Lev-Maor, G.; Ast, G. Alternative splicing and evolution: Diversification, exon definition and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanitz, A.; Gypas, F.; Gruber, A.J.; Gruber, A.R.; Martin, G.; Zavolan, M. Comparative assessment of methods for the computational inference of transcript isoform abundance from RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Gao, H.; Zhang, D. Genome-Wide Analysis of Light-Regulated Alternative Splicing in Artemisia annua L. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 733505. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Li, F.; Xu, Z.; Huang, C.; Xiong, C.; Jiang, C.; Xie, N.; Leng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yousaf, Z.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of methyl jasmonate-regulated isoform expression in the medicinal plant Andrographis paniculata. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 1, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Du, Y.; Sun, Z. Manual correction of genome annotation improved alternative splicing identification of Artemisia annua. Planta 2023, 258, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wu, J.; Sun, H. Single-molecule, full-length transcript isoform sequencing reveals disease-associated RNA isoforms in cardiomyocytes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Yu, Z.; Jin, S. Comprehensive assessment of mRNA isoform detection methods for long-read sequencing data. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamo, J.; Suzuki, A.; Ueda, M.T. Long-read sequencing for 29 immune cell subsets reveals disease-linked isoforms. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Beaudin, A.E.; Olsen, H.E. Nanopore long-read RNAseq reveals widespread transcriptional variation among the surface receptors of individual B cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinos, D.A.; Garborcauskas, G.; Hoffman, P.; Ehsan, N.; Jiang, L.; Gokden, A.; Dai, X.; Aguet, F.; Brown, K.L.; Garimella, K.; et al. Transcriptome variation in human tissues revealed by long-read sequencing. Nature 2022, 608, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.P.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Transcriptional census of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabi7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, W.D.; Liu, Y.Z.; Yang, Y.Q.; Liu, Z.G.; Zhao, K.; Lu, J.R.; Lei, G.Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Cai, L.; Sun, R.F. Effect of naturally derived surgical hemostatic materials on the proliferation of A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Pirrung, M.; McCue, L.A. FQC Dashboard: Integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3137–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Fernandez, C.; Gimeno, M.; San Martín, A.; Anorbe, A.; Rubio, A.; Ferrer-Bonsoms, J.A. A Systematic Identification of RNA-Binding Proteins (RBPs) Driving Aberrant Splicing in Cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.K.; Min, K.H.J.; Hjörleifsson, K.E.; Luebbert, L.; Holley, G.; Moses, L.; Gustafsson, J.; Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Booeshaghi, A.S.; et al. Kallisto, bustools and kb-python for quantifying bulk, single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq. Nat. Protoc. 2025, 20, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.D.; Soulette, C.M.; van Baren, M.J.; Hart, K.; Hrabeta-Robinson, E.; Wu, C.J.; Brooks, A.N. Full-length transcript characterization of SF3B1 mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals downregulation of retained introns. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.T.; Inamo, J.; Miya, F.; Shimada, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kochi, Y. Functional and dynamic profiling of transcript isoforms reveals essential roles of alternative splicing in interferon response. Cell Genom. 2024, 4, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Palacios, F.J.; Arzalluz-Luque, A.; Kondratova, L.; Salguero, P.; Mestre-Tomás, J.; Amorín, R.; Estevan-Morió, E.; Liu, T.; Nanni, A.; McIntyre, L.; et al. SQANTI3: Curation of long-read transcriptomes for accurate identification of known and novel isoforms. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, N.; Monzó, C.; McIntyre, L.; Conesa, A. Quality assessment of long read data in multisample lrRNA-seq experiments using SQANTI-reads. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trincado, J.L.; Entizne, J.C.; Hysenaj, G.; Singh, B.; Skalic, M.; Elliott, D.J.; Eyras, E. SUPPA2: Fast, accurate, and uncertainty-aware differential splicing analysis across multiple conditions. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Que, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, G.; Wang, Y.; Cong, Z.; Leng, L.; Wu, S.; Chen, C. Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Cell- and State-Specific Alternative Splicing in 293T and A549 Cell Transcriptomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010487

Li X, Que H, Liu Z, Xu G, Wang Y, Cong Z, Leng L, Wu S, Chen C. Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Cell- and State-Specific Alternative Splicing in 293T and A549 Cell Transcriptomes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010487

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xin, Hanyun Que, Zhaoyu Liu, Guoqing Xu, Yipeng Wang, Zhaotong Cong, Liang Leng, Sha Wu, and Chunyan Chen. 2026. "Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Cell- and State-Specific Alternative Splicing in 293T and A549 Cell Transcriptomes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010487

APA StyleLi, X., Que, H., Liu, Z., Xu, G., Wang, Y., Cong, Z., Leng, L., Wu, S., & Chen, C. (2026). Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Cell- and State-Specific Alternative Splicing in 293T and A549 Cell Transcriptomes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010487