Abstract

The dynamic remodeling of the fungal cell wall depends on a balance between chitin synthesis and degradation. Chitinases are critical for nutrient acquisition, cell wall remodeling, and defense; yet, the upstream regulatory mechanisms controlling chitinase gene expression remain poorly understood. Here, Tandem Affinity Purification–Mass Spectrometry (TAP–MS) with the Penicillium oxalicum Snf1 kinase (PoSnf1) as bait identified the zinc finger transcription factor (TF) PoCon7 as a putative target of the Snf1 kinase complex. This complex comprises the catalytic α subunit Snf1, one of three alternative β subunits Gal83, and the γ subunit Snf4. Although PoCon7 does not directly bind PoSnf1 or PoSnf4, it specifically interacts with PoGal83. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that PoCon7 is a conserved, nuclear-localized C2H2-type TF in filamentous fungi. PoCon7 is likely essential for fungal viability, as only a truncated mutant (con7-B) could be generated, while full deletion was lethal. The con7-B mutant displayed delayed hyphal extension, reduced conidiation, downregulation of developmental genes, and upregulation of cell wall-degrading enzyme (CWDE) genes. DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing (DAP-seq) revealed that PoCon7 binds target gene promoters via the motif 5′-TATTWTTAT-3′. ChIP-qPCR confirmed PoCon7 enrichment at specific sites within the chitinase genes chi18A and chi18C, and the disruption of PoCon7 markedly reduced their expression. Thus, PoCon7 represents the first TF shown to directly regulate chitinase gene expression in filamentous fungi.

1. Introduction

The fungal cell wall, which serves as the primary interface with the external environment, is a dynamic structure essential for maintaining cell integrity, morphology, and interaction with surroundings. Its composition is predominantly polysaccharide-based, with glucans and chitin accounting for approximately 90% of the cell wall’s dry weight [1]. Chitin is the second most abundant natural polymer after cellulose and is a key structural component in fungal cell walls and invertebrate exoskeletons [2,3]. The dynamic remodeling of the cell wall in these fungi relies on the coordinated actions of chitin synthases and chitinases [4,5].

Chitinases (EC 3.2.1.14) are hydrolytic enzymes that cleave β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in chitin and chito-oligosaccharides [6]. In fungi, chitinases fall exclusively within the glycoside hydrolase family 18 (GH18) [7,8]. Functionally, fungal chitinases participate in a range of physiological processes: (i) the degradation of exogenous chitin from fungal hyphae or arthropod exoskeletons for nutrient acquisition [9,10]; (ii) involvement in cell wall remodeling during hyphal elongation, branching, fusion, and autolysis [11,12]; and (iii) defense against competing fungi or predators [13]. This functional diversity implies the existence of sophisticated regulatory mechanisms to ensure precise control of chitinase expression. While some chitinase genes are known to be induced by chitin or cell wall components [14], the upstream regulators and associated signaling pathways remain largely unidentified.

One conserved eukaryotic kinase complex implicated in metabolic and developmental regulation is SNF1/AMPK, which in fungi comprises a catalytic α-subunit (Snf1), a γ-subunit (Snf4), and one of three alternative β-subunits (Gal83, Sip1, or Sip2) [15]. This complex is a key mediator of carbon catabolite repression and energy sensing [16,17]. It has been reported that the Snf1 kinase complex targets multiple transcription factors (TFs), such as Mig1, Adr1, Cat8, and Sip4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [18]. In several filamentous fungi, Snf1 orthologs have been shown to influence chitinase gene expression and cell wall integrity. For example, the deletion of SNF1 in Cordyceps militaris, Metarhizium acridum, and Beauveria bassiana led to a significant downregulation of chitinase genes and impaired cell wall remodeling [19,20,21].

Penicillium spp. are well-known fungi that play important roles in biotechnology and in the medical and food industries [22]. Penicillium oxalicum is an excellent secretor of cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDEs) and represents a promising microbial platform for CWDE production in white biotechnology [23,24]. The chitinase Chi18A, one of the top ten secreted proteins, is co-secreted with CWDEs [24]. Studies in Penicillium digitatum have shown that chitin metabolism not only regulate hyphal morphology and chitin content, but also significantly affect conidiation and pathogenicity [25]. Increased activities of chitinases and glucanases are often accompanied by a notable reduction in chitin and glucan content within the cell wall [26], indicating a close relationship between chitinase activity and cell wall composition. Moreover, normal growth and development in Penicillium marneffei are closely linked to cell wall structural integrity [27].

In this study, a homolog of TF Con7 was identified as a putative target of the Snf1 kinase complex in P. oxalicum. Functional characterization confirmed its essential role in fungal viability, hyphal growth, and conidiation. PoCon7 directly binds to chitinase gene promoters to regulate their expression, establishing PoCon7 as their direct transcriptional regulator.

2. Results

2.1. TAP-MS Identifies PoCon7 as a Novel Component Associated with the Snf1 Complex

Multiple studies have indicated that Snf1 orthologs play a critical role in chitinase expression and/or cell wall remodeling [19,20,21]. To elucidate the underlying mechanism, we sought to identify the key target proteins through which Snf1 mediates these functions. We used Tandem Affinity Purification coupled with Mass Spectrometry (TAP–MS), a method highly effective in identifying in vivo protein partners of a protein of interest in fungi [28,29,30], as the two-step purification process can effectively reduce proteins that bind non-specifically. The Snf1-TAP strain was constructed by attaching the HA-FLAG tag to the C-terminus of PoSnf1 (PDE_02007, UniProt Entry S7ZEF0). The native PoSnf1 in the P. oxalicum wild-type (WT) strain 114-2 was used as a control, with two biological replicates for the TAP-MS experiment. After the two-step tandem purification, the final eluate was divided into three sections: one designated for SDS-PAGE, another for Western blot, and the third for MS-MS assay to identify the potential interacting proteins of the PoSnf1 bait.

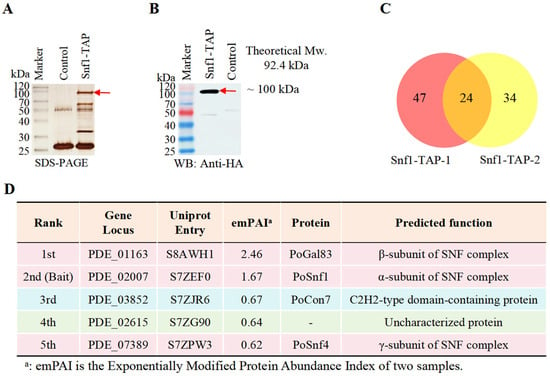

PoSnf1 protein is theoretically 92.4 kDa in molecular weight. An ~100 kDa band was detected between the control (WT) and Snf1-TAP strains on the SDS-PAGE gel (Figure 1A, red arrow), as confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 1B, red arrow).

Figure 1.

Results from TAP-MS with PoSnf1 as the bait. (A) Silver staining after SDS-PAGE of Snf1-TAP eluate. (B) Western blot of Snf1-TAP eluate using an anti-HA antibody. (C) Overlapping proteins in two Snf1-TAP-1 and Snf1-TAP-2 biological samples. (D) The top 5 proteins identified through TAP-MS. Light blue: bait protein PoCon7; light pink background: three subunits of the Snf1 kinase complex; light green background: other proteins. Detailed information, including Unique_PepCount identified by LC-MS/MS, gene locus, theoretical PepCount, emPAI, and predicted functions of potential interacting proteins, is available in Supplementary Spreadsheet S1.

To identify the PoSnf1 bait and its possible interacting proteins, the third section of the eluent was examined using LC-MS/MS. The proteins identified in the two biological replicates, Snf1-TAP-1 and Snf1-TAP-2, via TAP-MS are detailed in Supplementary Spreadsheet S1. Based on the exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) [31], the identified proteins were ranked to estimate their abundance within the sample. The samples Snf1-TAP-1 and Snf1-TAP-2 contained 71 and 58 identified proteins, respectively. Credible proteins that may interact with PoSnf1 include 24 proteins identified in two Snf1-TAP samples but not in any control samples (Figure 1C and Supplementary Spreadsheet S1). In Figure 1D, the five proteins with the highest emPAI rankings are presented.

The bait PoSnf1 is ranked second as the α subunit of Snf1 kinase complex.

The protein with the highest emPAI is PDE_01163 (Uniprot Entry S8AWH1). We name PDE_01163 as PoGal83 because its homolog in S. cerevisiae is protein Gal83, which is the β subunit of the Snf1 kinase complex that functions as an adaptor that brings Snf1 and Snf4 into proximity and also contributes to the substrate specificity of the kinase complex [32].

The protein with the third-highest emPAI is PDE_03852 (Uniprot Entry S7ZJR6), a C2H2-type domain-containing protein. PDE_03852 was named PoCon7 based on its homology to the Con7p TF in Magnaporthe oryzae and F. graminearumis is Con7 [33,34].

The protein ranked 4th (PDE_02615) is an uncharacterized protein.

The protein ranked 5th (PDE_07389) is named PoSnf4 because its homolog in S. cerevisiae is Snf4, the γ subunit of the Snf1 complex that binds to and activates the kinase catalytic subunit under stress conditions [35].

In summary, all three subunits of the Snf1 kinase complex, including the α-subunit (Snf1), β-subunit (Gal83), and γ-subunit (Snf4), were detected in the TAP-MS results, confirming the integrity of the complex. Additionally, a novel interacting protein, PoCon7, was identified, suggesting its identification as a potential target of the Snf1 kinase complex.

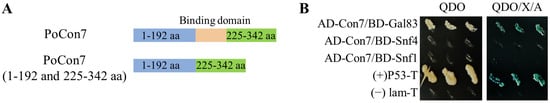

2.2. PoCon7 Interacts Directly with PoGal83

Given that the TAP results may include indirect interactions mediated by bridging proteins, a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay was performed to determine: (1) whether PoCon7 interacts directly with the PoSNF complex; and (2) which subunit or subunits of the complex are responsible for this interaction. Y2H strains were constructed to express PoCon7 along with each individual subunit of the Snf1 kinase complex PoSnf1, PoSnf4, and PoGal83. After confirming the absence of toxicity and autoactivation in these strains (Supplementary Figure S1), direct interaction was observed specifically between PoCon7 and PoGal83. No direct interaction was detected between PoCon7 and either PoSnf1 or PoSnf4 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The results of Y2H. (A) Strategy of Y2H. DNA-binding domain (193–224) was removed from PoCon7 as the intact protein showed autoactivation. (B) Hybridization results of Y2H Gold-BD-PoGal83/Snf4/Snf1 and Y187-AD-PoCon7 strains on QDO (quadruple-dropout, SD-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp) and QDO/x-α-gal/Aba (QDO supplemented with X-α-gal and aureobasidin A).

2.3. PoCon7 Is a Conserved Nuclear-Localized TF in Filamentous Fungi

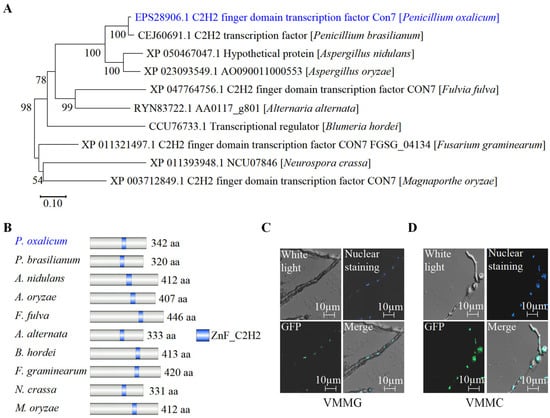

To further characterize PoCon7, we performed phylogenetic analysis and subcellular localization determination.

Using the protein sequence of PoCon7, a BLASTP search was performed on the landmark database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/smartblast/smartBlast.cgi?) (accessed on 10 June 2024), which comprises 27 genomes from well-researched reference species covering a diverse taxonomic range. In well-known model organisms like Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Caenorhabditis elegans, Mus musculus, and Drosophila melanogaster, no homologous protein exists. PoCon7, despite not being identified in well-researched reference species, is phylogenetically conserved and present in different filamentous fungi (Figure 3A and Supplementary Spreadsheet S2). The study of domain architectures in several Con7 orthologs from different filamentous fungi indicated that each contains a C2H2 domain (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Analysis of phylogenetic relationships and subcellular localization of PoCon7. (A) Construction of the phylogenetic tree of the pocon7 homologous protein. (B) Domain analysis of PoCon7 homologous protein in different filamentous fungi. Numbers indicate the total count of amino acids for each protein. For example, 342 aa indicates that there are 342 amino acids. The conserved C2H2 zinc-finger domains are highlighted in blue. These figures were made after the corresponding protein sequence was scaled in a uniform scale. (C) The subcellular localization of PoCon7 on VMMG. (D) The subcellular localization of PoCon7 on VMMC. This picture has four parts: upper left, white light; upper right, Hoechst 33,342 was used to stain nuclei in blue; bottom left, green fluorescence; bottom right, merged image of green fluorescence and nuclear staining.

To assess its subcellular localization, we generated a Con7-GFP strain in P. oxalicum by replacing the native PoCon7 with a GFP-tagged version. Since the nuclear localization of TFs can be signal-dependent [36], we examined the localization of PoCon7 under two different carbon source conditions: Vogel’s minimal medium (VMM) supplemented with 2% glucose (VMMG) or 2% cellulose (VMMC). VMMG, with glucose as the carbon source, mimics nutrient-rich environments commonly used in laboratory or industrial fermentation settings, where readily metabolizable sugars are available. In contrast, VMMC, containing cellulose as the sole carbon source, simulates the natural ecological niche of fungi, where they commonly encounter plant cell walls in which cellulose serves as the primary structural polymer. An overlap of green fluorescence (Figure 3C,D, bottom left) and nuclear staining (Figure 3C,D, top right) was observed on the merged image (Figure 3C,D, bottom right), regardless of whether strain Con7-GFP was cultured on VMMG or VMMC. The results indicate that Pocon7 is localized in the nucleus, whether under glucose or cellulose signal.

2.4. PoCon7 Is Essential for Fungal Viability and Is Required for Normal Growth and Conidiation

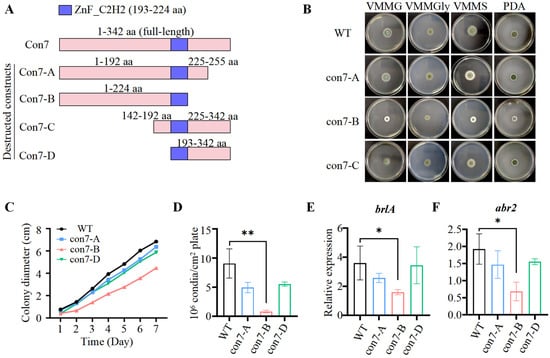

To further elucidate the biological role of PoCon7, we first attempted to generate a complete deletion mutant. However, this effort was unsuccessful. We hypothesized that PoCon7 deletion might be lethal in P. oxalicum. Then, we adopted alternative strategies to construct disruptive mutants of PoCon7. Four mutant designs (A–D) were engineered (Figure 4A), three of which (con7-A, con7-B, and con7-C) were successfully generated.

Figure 4.

Colony morphology and conidiation of WT and PoCon7-associated mutants. (A) Schematic illustration of PoCon7-associated mutants. (B) The colony morphology of strains cultivated on VMMG, VMMGly, and VMMS agar or PDA. The strains were cultivated on at 30 °C for 4 days. (C) Colony diameters on VMMG agar. (D) Levels of conidiation of the colony in 4-day-old cultures on VMMG agar. Assay of the transcription levels of genes brlA (E) and abr2 (F). Gene expression copy numbers were calculated using the standard curves constructed for each gene, and the data were then normalized with the expression levels of the actin gene. Three biological triplicates were performed, and the mean values and standard deviations were calculated. Statistical analysis was performed with a one-tailed homoscedastic (equal variance) t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

On solid media including VMMG, VMMGly (VMM with 2% glycerol), VMMS (VMM with 2% sucrose), and potato dextrose agar (PDA), the con7-A and con7-C mutants showed no significant differences in growth or colony morphology compared to the WT. The con7-B mutant, however, exhibited not only reduced radical growth but also a significantly lighter colony color than the WT (Figure 4B). Taking its growth on VMMG agar as an example: the colony diameter of con7-B was only 57.2% of that of the WT after 5 days of cultivation (Figure 4C). Interestingly, when cultured in VMMG liquid medium, the con7-B mutant did not show a significant difference in biomass compared to the WT (Supplementary Figure S2). This is likely because the smaller colony size on solid media reflects impaired polarized hyphal extension necessary for surface colonization, whereas the unchanged biomass in liquid culture indicates that the mutation does not affect the overall metabolic capacity for proliferation.

The lighter colony color of the con7-B mutant could be attributed to reduced conidiation and/or impaired spore pigment synthesis. Measurement of conidial production confirmed a severe conidiation defect, with the con7-B mutant yielding only ~9.0% of the conidia produced by the WT (Figure 4D). We then investigated the expression of key regulatory genes of conidiation. In P. oxalicum, a central regulatory pathway for asexual development consists of three TFs (BrlA → AbaA → WetA), among which BrlA is the most critical and is necessary to drive conidiation [37,38]. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that brlA transcription was significantly downregulated in the con7-B mutant (Figure 4E). In addition, given that pigments are essential structural components of the spore wall and that P. oxalicum possesses a predicted dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN)–melanin biosynthesis pathway (Abr2 → Abr1 → Ayg1 → Arp1 → Arp2 → PksP/Alb1) [39,40], we analyzed the expression of abr2, the first gene in this pathway. The results showed that abr2 expression was also markedly reduced in the con7-B mutant (Figure 4F).

2.5. PoCon7 Directly Binds and Regulates Chitinase Genes

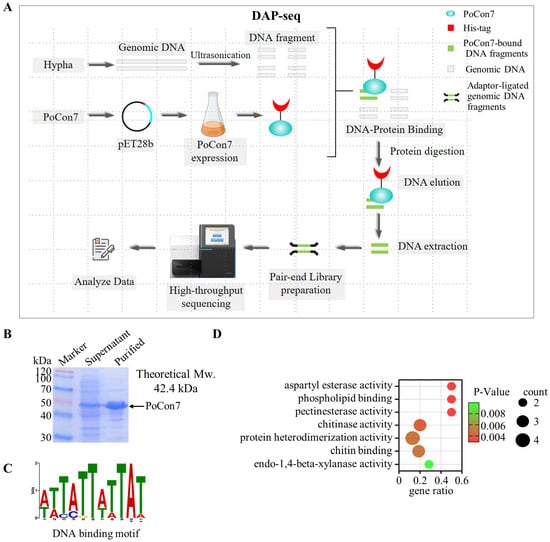

To elucidate the molecular basis of the lethal phenotype caused by the absence of PoCon7, we sought to identify its direct genomic targets. DNA Affinity Purification sequencing (DAP-seq) was performed to map PoCon7-binding sites across the genome (Figure 5A). PoCon7 was expressed in E. coli (Figure 5B), and then the purified recombinant PoCon7 was subjected to DAP-seq analysis, which identified 211 high-confidence peak regions located within promoter sequences (Supplementary Spreadsheet S3). The binding motif of PoCon7 was verified as 5′-TATTWTTAT-3′ (Figure 5C). GO enrichment analysis revealed that 211 peaks were significantly enriched in terms including “chitinase activity” and “chitin binding” (Figure 5D and Supplementary Spreadsheet S4). These enrichment results demonstrate that PoCon7 regulates genes related to chitinases.

Figure 5.

The DAP-seq experiment of PoCon7. (A) Schematic workflow diagram of DAP-seq. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of PoCon7 recombinantly expressed in E. coli. (C) DNA binding motif enrichment analysis of PoCon7. (D) GO enrichment of peak-related genes in Con7.

2.6. ChIP-qPCR Reveals the Enrichment of PoCon7 at Promoter Regions of Key Chitinase Genes

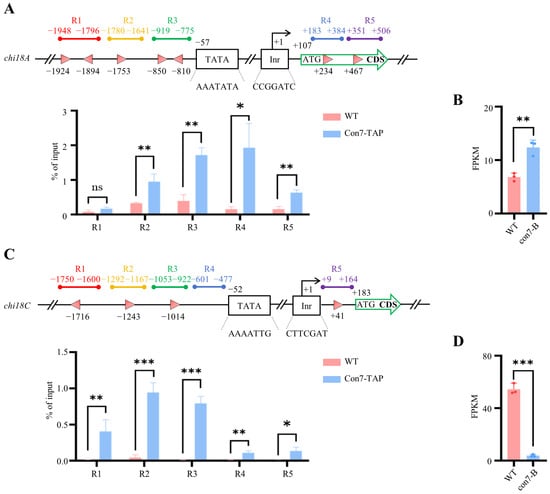

To further validate the binding status of PoCon7 to its target genes, we performed ChIP-qPCR assays. The target genes selected were chi18A (PDE_08122) and chi18C (PDE_06566). chi18A was the most abundant secreted chitinase in P. oxalicum [41], while PDE_06566 was identified as a chitinase in DAP-seq screening. ChIP-qPCR methods and results appear in Figure 6 and Supplementary Spreadsheet S5. Five representative regions (regions 1–5) encompassing upstream sequences and CDS were analyzed for each gene.

Figure 6.

PoCon7 enrichment in the specific regions of chitinase genes assayed by ChIP-qPCR and effects of PoCon7 on the transcription levels of chitinase genes when the WT strain is cultivated on VMMG agar. (A) Chitinase gene chi18A. (B) The expression level of chi18A in con7-B mutant. (C) Chitinase gene chi18C. (D) The expression level of chi18C in con7-B mutant. Top subgraphs depict ChIP-qPCR strategies employed for each gene, with the transcription start site (TSS) positioned at +1. The initiator (Inr) and TATA box elements are illustrated. Pink triangles denote PoCon7 DNA-binding sites, with their orientation indicating the orientation of the binding motif. Bottom subgraphs present ChIP-qPCR results, with relative enrichment of IP DNA calculated as a percentage of input. All data represent average values obtained from measurements in biological triplicates, with error bars denoting standard deviations. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. FPKM stands for fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments.

When designing the ChIP-qPCR assay for chi18A, we positioned regions 1, 2, and 3 (R1/2/3) approximately 2000 bp upstream (-) of the transcription start site (TSS), while region 4 (R4) and region 5 (R5) were positioned near the 5′ region of CDS. The ChIP-qPCR results reveal that PoCon7 binds to regions 2/3/4 and the 5′-CDS in the Con7-TAP strain. Notably, regions 3 and 4 show significantly higher enrichment levels compared to regions 2 and 5. However, despite containing two PoCon7 binding sites, region 1 exhibits no substantial enrichment (Figure 6A).

The ChIP-qPCR design of the chi18C gene is similar to that of the chi18A gene. All four regions (R1/2/3/4) are situated approximately 2000 bp upstream (-) of the TSS, while region 5 (R5) is positioned near the 5′ region of CDS. Notably, PoCon7 enrichment was detected across every region examined (R1/2/3/4/5), with the most pronounced enrichment occurring at R2 and R3. These findings suggest that PoCon7 directly interacts with chitinase genes (Figure 6C). Moreover, transcriptome data reveal significant changes in the expression levels of chi18A and chi18C (Figure 6B,D), further supporting that con7 directly regulates the expression of chitinase genes.

2.7. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals an Extensive Regulatory Role for PoCon7

To analyze the global regulatory role of PoCon7, we further performed transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses on the WT and con7-B mutant cultured in VMMG and VMMC liquid medium.

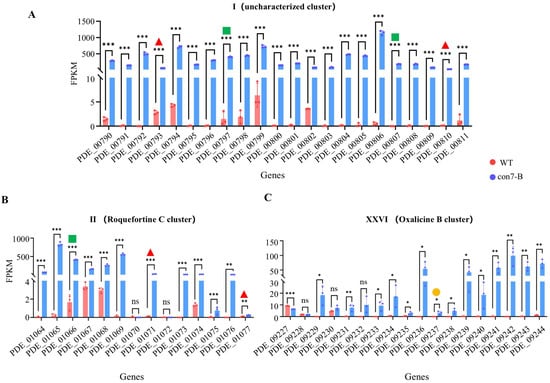

Under glucose condition, compared to the WT strain, the con7-B mutant exhibited 1856 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1, Q-value < 0.05), with 1190 upregulated and 666 downregulated (Supplementary Spreadsheet S6). GO enrichment analysis of upregulated genes in the con7-B mutant revealed associations with biological processes (BPs) related to the growth and development of fungi, including “Phenol-containing compound metabolic process”, “Phenol-containing compound biosynthetic process”, and “Terpenoid/Isoprenoid metabolic process” (Figure S3). These findings suggest that PoCon7 might regulate secondary metabolism. There are 28 predicted secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in P. oxalicum (Supplementary Spreadsheet S7) [42]. We analyzed 28 clusters and noticed these three clusters. All genes in Cluster I (PDE_00790—PDE_00811) were significantly upregulated (Figure 7A), though the secondary metabolite encoded by this cluster remains unknown. Nearly all genes in Cluster II (PDE_01064—PDE_01077) exhibited significantly upregulation (Figure 7B), and this cluster is responsible for the production of the secondary metabolite roquefortine C [43]. Similarly, Cluster XXVI (PDE_09227—PDE_09244) also showed an upregulation of almost all genes (Figure 7C), which has been reported to encode the biosynthesis of oxalicine B [44]. However, the DAP-seq data did not identify significant peaks in the promoters of the core backbone genes of these clusters. The result suggests that PoCon7 does not directly regulate these backbone genes by binding to their promoters. The results indicate that Con7 affects the synthesis of secondary metabolites indirectly.

Figure 7.

Effects of PoCon7 on regulating secondary metabolic clusters. Expression patterns of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters I (A), II (B), and XXVI (C). Core backbone biosynthetic genes in each BGC are denoted: red solid triangle: nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) gene; green solid square: dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (DMATS) gene; orange solid circle, polyketide synthase (PKS) gene. All data represent average values obtained from measurements in biological triplicates, with error bars denoting standard deviations. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. FPKM stands for fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments.

Under cellulose condition, compared to the wild-type (WT) strain, the con7-B mutant exhibited 1,219 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1, Q-value < 0.05), with 620 upregulated and 599 downregulated (Supplementary Spreadsheet S8). GO enrichment analysis of the upregulated genes in the con7-B mutant revealed associations with biological processes (BPs) related to cell wall component metabolism, including “Polysaccharide metabolic process”, “Carbohydrate metabolic process”, and “Cellulose catabolic process” (Supplementary Figure S3). Notably, polysaccharides such as cellulose and chitin are key structural components of plant and fungal cell walls. The enriched cellular component (CC) terms included “extracellular region” and “plasma membrane” (Supplementary Figure S3). The extracellular region is exactly the localization where cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs) are secreted and enriched. Molecular function (MF) terms included “hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds”, where a major component of O-glycosyl compounds is cell wall polysaccharides, represented by cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin (Supplementary Figure S3). These findings collectively suggest that PoCon7 disruption may promote the upregulation of CWDE-encoding genes. Furthermore, we examined the intersection between the DEGs (|log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1, Q-value < 0.05) from transcriptomes and the 211 DAP-seq genes. This intersection identified 56 genes, among which was the chitinase gene chi18C (Supplementary Spreadsheet S9), providing evidence for the direct regulation of chitinase genes by PoCon7.

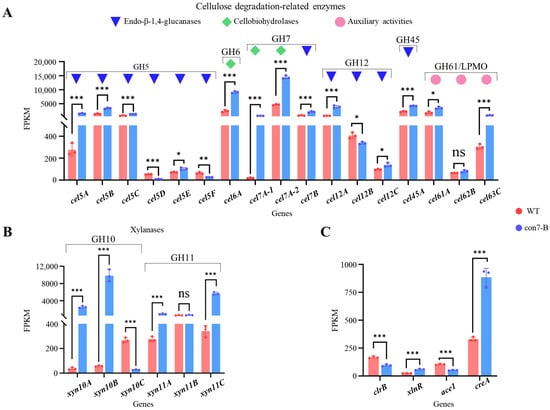

2.8. Disruption of PoCon7 Perturbs the Transcriptional Regulatory Network to Indirectly Enhance (Hemi)Cellulase Expression

Then, we analyzed the expression of genes encoding the major cellulose-degrading enzymes among the CWDEs. Among the 17 cellulose-degrading enzymes, comprising 14 cellulases (11 endo-β-1,4-glucanases and 3 cellobiohydrolases) classified into glycoside hydrolase (GH) families 5, 6, 7, 12, and 45, and 3 lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs; formerly GH61), 14 genes were upregulated in the con7-B mutant (Figure 8A). Notably, the expression levels of the two most abundantly secreted endoglucanases (Cel7B/EG1 and Cel5A/EG2) and the two major cellobiohydrolases (Cel7A-2/CBH1 and Cel6A/CBH2) were all significantly upregulated. Furthermore, expression analysis of the six most abundantly secreted xylanases (three from GH10 and three from GH11 families) revealed that four of the corresponding genes were significantly upregulated in the con7-B mutant (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Effects of PoCon7 on transcription levels of genes encoding key CWDEs and TFs. Expression patterns of cellulose degradation-related genes (A), xylanase genes (B), and key TF genes (C). FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

We also analyzed the expression of four key TFs known to regulate (hemi)cellulase expression: the negative regulators Ace1 and CreA [30,45], and the positive regulators ClrB and XlnR [46,47]. Transcriptome analysis revealed that in the con7-B mutant, the expression of the transcriptional repressor CreA and the activator XlnR was upregulated, whereas the activator ClrB and the repressor Ace1 were downregulated (Figure 8C). However, the DAP-seq data did not identify significant peaks in the promoters of the TF genes clrB, xlnR, ace1, or creA. The result suggests that PoCon7 does not directly regulate these TFs by binding to their promoters. Therefore, the enhancement of the (hemi)cellulase gene expression occurs through an indirect mechanism. These alterations suggest that PoCon7 likely perturbs the transcriptional regulatory network, triggering a cascade of effects that indirectly drive the upregulation of (hemi)cellulase genes expression.

3. Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the TF PoCon7, a downstream target of the Snf1 complex, is likely essential for fungal viability and functions as a direct upstream regulator of chitinase genes.

This finding is similar to the results observed for its homologous proteins, MoCon7 in M. oryzae and FgCon7 in F. graminearum. In the rice blast fungus M. oryzae, TF MoCon7 was first identified and found to affect pathogenicity and cell wall composition [33]. The study on F. graminearum demonstrates that FgCon7 is essential for conidiation as it regulates master regulator genes of conidiation [34]. Nevertheless, the upstream regulators of Con7, the genes it directly regulates, and the DNA motifs to which it binds have not been fully elucidated.

In P. oxalicum, the complete deletion of the Pocon7 gene could not be obtained, indicating that it is likely essential for fungal viability. Similarly, studies on M. oryzae relied on the partial disruption of Mocon7 via T-DNA insertion in the promoter region that severely reduces its expression, rather than a full knockout [33]. While we propose that Con7’s role in regulating chitinases may influence growth, the individual deletion of chitinase genes typically does not cause cell death in most fungi [48,49,50]. This is likely due to functional redundancy within the gene family [51]. Therefore, we speculate that the deletion lethal phenotype produced by PoCon7 as an essential gene may stem from two mechanisms. First, PoCon7 may directly bind to and coregulate multiple chitinase genes, and its absence could severely disrupt normal fungal growth. Second, based on the DAP-seq results, PoCon7 was found to bind to the promoter regions of multiple other genes involved in stress response, signal transduction, and regulation, for example, PDE_03760 and PDE_09149. Its homologous protein in S. cerevisiae is Hsp70 and Hsp90. The conserved Hsp90 and Hsp70 molecular chaperones are essential for proteome maintenance [52]. Maintaining a healthy proteome is fundamental for the survival of all organisms [53].

PoCon7 binds to and regulates chitinase genes. This finding aligns with the established role of its ortholog, MoCon7, in M. oryzae. There, MoCon7 is a master regulator of cell wall homeostasis, and its disruption leads to the dysregulation of multiple genes involved in chitin synthesis, binding, and modification [33]. Indeed, associations between TFs and chitinase regulation have been noted in other fungi. For example, in Aspergillus nidulans, both TF RlmA and RlmA-independent factors regulated the expression of chitinase genes chiA and chiB [54]. In Trichoderma reesei, the deletion of TF gene xyr1 led to the upregulation of chitinase-encoding genes [55]. Similarly, in M. oryzae, the suppression of the TF OsNAC111 resulted in a reduced expression of chitinase genes [56]. However, none of these TFs have been established as directly binding to and regulating chitinase genes. Moreover, the con7-B mutant exhibits growth and developmental defects (Figure 4). We propose that these defects are closely linked to the biological role of PoCon7 as a transcriptional regulator of chitinase genes. Chitinases play critical roles in multiple developmental stages of filamentous fungi, including sporulation, spore germination, hyphal growth, and hyphal autolysis. In S. cerevisiae, the disruption of the chitinase gene CTS2 results in abnormal spore wall biosynthesis and failure to form mature asci [57]. Rhizopus oligosporus chitinase Chi3 loosens the cell wall at the hyphal tip, enabling turgor pressure to extend the hypha at the apex [58]. In M. oryzae, the deletion of the chitinase-encoding gene Chi1 leads to reduced hyphal growth [51]. Similarly, in Neurospora crassa, the deletion of a chitinase gene disrupts hyphal cell wall remodeling [48]. Notably, while chi18C was transcriptionally downregulated in the con7-B mutant, it is known that in A. nidulans, the deletion of its homolog chiA gene leads to decreased spore germination and lower hyphal growth rates [59].

PoCon7 was also found to regulate the expression of CWDE genes, which was an unexpected result. We believe that the regulation of CWDE gene expression by PoCon7 is not a direct regulation, but rather a cascading indirect effect. The propose supported by the observed upregulation of the major activator ClrB, XlnR, and the downregulation of the repressor Ace1, both known to enhance CWDE production [45,46,47]. In fact, the deletion of ace1 has been shown to increase xlnR transcription [60]. In the xlnR deletion strain, the transcript levels of clrB significantly decreased [61]. Interestingly, the negative regulator CreA was also upregulated, adding complexity to the regulatory landscape. However, the DAP-seq data did not identify significant peaks in the promoters of the TF genes clrB, xlnR, ace1, or creA. This suggests that PoCon7 does not directly regulate these TFs by binding to their promoters. Therefore, the proposed enhancement of (hemi)cellulase gene expression likely occurs through an indirect mechanism. Together, PoCon7 and these TFs, through their genetic relationships, dosage effects, and competitive interactions, form an intricate network that fine-tunes CWDE gene expression.

Similar to the phenotype observed in PoCon7-disrupted mutants, Snf1 orthologs in many filamentous fungi are key regulators of normal fungal growth and development as well as of chitinase gene expression [19,20,21,62]. Although the TF CreA, which is the fungal homolog of yeast Mig1 and a primary Snf1 target [18], was the anticipated interactor of PoSnf1, our TAP-MS analysis identified PoCon7 as the associated factor. Notably, CreA, a factor whose disruption/deletion/mutation upregulates CWDEs [63,64], and PoCon7 are involved in CWDE gene regulation, linking the Snf1 kinase pathway to CWDE expression control. However, CreA and PoCon7 exhibit a fundamental difference in their regulatory mechanisms. CreA displays dynamic nucleocytoplasmic trafficking mediated by glucose concentration [65]. In contrast, PoCon7 maintains constitutive nuclear localization, whether under glucose or cellulose signal conditions.

Y2H showed that PoCon7 directly interacts with PoGal83, but not with the core catalytic subunits PoSnf1 or PoSnf4. As an adaptor protein, the ASC domain of PoGal83 can simultaneously bind Snf4 and substrate proteins [15,66]. These findings support a model in which PoCon7 is indirectly linked to the SNF complex through PoGal83, forming a transient regulatory module (PoSnf1–Gal83–Con7). As a target of Snf1, the phosphorylation status of CreA is known to modulate its transcriptional repressor activity [67]. The PoCon7 protein was analyzed for potential phosphorylation sites using NetPhos-3.1 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos-3.1/, accessed on 10 June 2024). Several residues, S244, Y38, S52, S108, T166, and S274, showed high phosphorylation potential, with prediction scores above 0.9 (Supplementary Spreadsheet S10). As these sites are predicted computationally, their actual phosphorylation status and functional relevance require further experimental validation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fungal Strains and Culture Conditions

The wild-type (WT) strain of P. oxalicum 114–2 (CGMCC 5302) served as the parent strain for all experiments. Both the WT and its mutants were cultured on agar plates supplemented with 10% wheat bran extract and incubated at 30 °C for five days to allow for conidiation. To assess mycelial development, the various strains were grown in 1× Vogel’s minimal medium (VMM) (50 × Vogel’s salt: 125.0 g Na3Citrate·2H2O, 250.0 g KH2PO4, 100.0 g NH4NO3, 10.0 g MgSO4·7H2O, 5.0 g CaCl2·2H2O, 0.25 mg biotin, 0.25 g citric acid, 0.25 g ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.05 g Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O, 12.5 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 2.5 mg MnSO4·H2O, 2.5 mg H3BO3, 2.5 mg Na2MoO4·2H2O, and 1 L of water) [68] at 30 °C, plus 2% glucose (VMMG), 2% glycerol (VMMGl), or 2% sucrose (VMMS) as the sole carbon source. For solid-phase cultivation on plates, 1.5% agar was added to the VMMG, VMMGly, or VMMS.

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Domain Architecture Analysis

The amino acid sequences of Con7 homologs of different species were obtained from NCBI database. We used the neighbor-joining method in Clustal X 1.83 [69] and MEGA 7.0 [70] to make multiple sequence alignments and draw physiological trees. Protein domain analysis was performed with SMART [71] and Pfam3 [72] databases. Domain architecture patterns were created in proportion to the corresponding protein sequences.

4.3. Construction of Different Mutants

All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Spreadsheet S11.

The Snf1-TAP strain, carrying a C-terminally FLAG-HA-tagged PoSnf1, was generated and validated as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S4A–C. To construct this strain, the 5′-upstream and 3′-downstream homologous arms flanking the PoSnf1 gene were amplified from the WT P. oxalicum genomic DNA using the primer pairs Snf1-TAP-UF/Snf1-TAP-UR and Snf1-DF/Snf1-DR, respectively. Primer pairs hph-F/hph-R were used to amplify the hygromycin B resistance gene (hph) from the plasmid Psilent1 [73]. Subsequently, the hph fragment, along with the 5′-upstream and 3′-downstream regions of the Posnf1 gene, were fused via fusion PCR. The PCR product was further amplified using nested primers Snf1-TAP-CSF/Snf1-CSR and subsequently was transformed into the wild-type strain to generate the Snf1-TAP mutant. Correct integration of the FLAG-HA tag was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The Con7-GFP strain (the protein PoCon7 fused with a green fluorescent protein (GFP)), was constructed, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5A,B. Briefly, the 5′-upstream and 3′-downstream homologous arms of the Pocon7 gene were amplified from P. oxalicum WT genomic DNA using primers Con7-GFP-UF/Con7-GFP-UR and Con7-GFP-DF/Con7-GFP-DR. The gfp and hph marker genes were amplified from plasmids pEGFP and Psilent1 with primer pairs gfp-F/gfp-R and hph-F/hph-R, respectively. The four fragments (the two homologous arms of the Pocon7 gene, gfp, and hph) were then fused by fusion PCR. The PCR product was amplified with nested primers Con7-GFP-CSF/Con7-GFP-CSR and transformed into the WT strain to generate the Con7-GFP mutant.

The truncated mutant con7-B (the gene Pocon7 was partially disrupted) was constructed, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5C,D. To construct this strain, the 5′-upstream and 3′-downstream homologous arms of the Pocon7 gene were amplified from P. oxalicum WT genomic DNA using primers con7-B-UF/con7-B-UR and con7-B-DF/con7-B-DR. Primer pairs hph-F/hph-R were used to amplify the marker gene hph. Subsequently, the hph fragment, along with the 5′-upstream and 3′-downstream regions of the Pocon7 gene, were fused via fusion PCR. The PCR product was further amplified using nested primers con7-B-CSF/con7-B-CSR and subsequently was transformed into the WT strain to generate the con7-B mutant.

4.4. Fungal Colony and Microscopic Observation

Fresh spore suspensions (107/mL) from different strains were prepared and spotted (2 μL) onto VMMG, VMMGly, or VMMS, or onto potato dextrose agar (PDA). Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 4 days to assess colonial growth.

For observing hyphae in the Con7-GFP strain, 100 μL of fresh spore suspensions was spread on VMMG or VMMC (VMM with 2% ball-milled cellulose) agar inserting sterile coverslips. After 24 h at 30 °C, the coverslips were removed, and the mycelia were stained with 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33,342 for 15 min in the dark for nuclear staining. Samples were imaged using a ZEISS LSM900 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with excitation values at 488 nm (GFP) and 405 nm (nuclei).

4.5. Tandem Affinity Purification and Mass Spectrometry

Fresh conidial suspensions of P. oxalicum WT and Snf1-TAP strains were cultured in 2 L of VMMG liquid medium at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h. The harvested mycelia were washed twice with 0.96% NaCl (w/v) containing 1% DMSO and 1 mM PMSF, then ground under liquid nitrogen. The resulting powder was resuspended in 15 mL of protein lysis buffer (containing 9 g/L NaCl, 1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mL/L glycerol, 10 mL/L NP-40, and 0.05% Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China)) and incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 30 min, the supernatant was collected.

For the first affinity purification step, the supernatant was incubated with ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Resin (Smart-Lifesciences, Changzhou, China) overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation. Bound proteins were eluted by competition with 500 µL of 3×FLAG peptide (150 ng/µL). The eluate was then subjected to a second affinity purification using ANTI-HA Resin (Smart-Lifesciences, China) under the same incubation conditions. Final elution was performed using 80 µL of 8 M urea to obtain the final protein eluate.

The final eluate was divided for three parts: separation by 12.5% SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining; Western blot using an anti-HA antibody (ABclonal, Wuhan, China); and LC-MS/MS (APT, Shanghai, China) for protein identification. Relative protein abundance was estimated using the emPAI (exponentially modified Protein Abundance Index) method [31], where emPAI = 10PAI − 1, and PAI represents the ratio of experimentally observed to theoretically observable tryptic peptides (Nobserved/Nobservable) for each protein.

4.6. Total RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis by RT-qPCR

Fresh spore suspensions from different strains were incubated in VMMG liquid medium at 30 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, 0.3 g of filtered hyphae was transferred to 50 mL of fresh VMMG and VMMC and cultured at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. After 24 h, the mycelia were collected by centrifugation and ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of the ground powder using TRIzol reagent (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed using a LightCycler 480 system with software version 4.0 (Roche, Basel, Germany) with specific primers for PobrlA, Poabr2, and Poactin (see Supplementary Spreadsheet S11). The Poactin gene (PDE_01092) was used as the internal control. Relative expression was calculated as the ratio of the target gene copy number to that of actin. All experiments were conducted with three biological replicates, and statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05.

4.7. Transcriptome Analysis and GO Analysis

Strains were cultured as described in the “Real-time quantitative PCR” section. After 24 h of growth in VMMC, fresh mycelia of the WT and con7-B strains were collected, ground in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). To remove genomic DNA, the RNA was treated with 10 U of DNase I at 37 °C for 30 min. mRNA quality was verified based on the following criteria: OD260/OD280 between 1.8–2.2, OD260/OD230 greater than 1.5, and an RNA integrity number (RIN) above 8.0. Transcriptome sequencing was conducted on the BGISEQ-500 platform at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Shenzhen, China). Sample saturation analysis was performed to confirm suitability for omics studies.

Clean reads for each gene were normalized using the fragments per kilobase transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) for differential expression analysis. Significantly differentially expressed genes were identified with the thresholds |log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1 and Q-value < 0.05. Functional enrichment and GO annotation were carried out with ShinyGO v0.82 (FDR ≤ 0.05), and cluster analysis was performed using Genesis 1.0 software [74].

4.8. Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

For yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays, truncated versions of PoCon7 CDS (avoiding the DNA-binding domain; amino acids 1–192 and 225–342) were amplified using primers con7-BDF/con7-BDR. The products were cloned into the plasmid pGADT7 and transformed into S. cerevisiae Y187. Similarly, the CDS sequences of PoGal83, PoSnf4, and PoSnf1 were amplified with specific primer Gal83-BDF/Gal83-BDR, Snf4-BDF/Snf4-BDR and Snf1-BDF/Snf1-BDR, and cloned into pGBKT7, which was then transformed into S. cerevisiae Y2HGold. Protein–protein interactions were assessed by growing the Y2H strains on QSD (SD-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade) and QSD/X/Aba (SD-Leu/−Trp/-His/−Ade/x-α-gal/Aba) agar plates.

4.9. Protein Expression and Purification

The codon-optimized coding sequence of PoCon7 was synthesized by GenScript Biotech Corporation (Nanjing, China) for heterologous expression in E. coli. Following digestion with SalI and XhoI, the fragment was ligated into similarly digested pET28b(+). The resulting recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein expression. The transformed cells were cultured in LB medium supplemented with 30 mg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C until OD600 reached a range of 0.6–0.8. Expression was induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 18 °C for 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (14,000 g, 4 °C, 15 min), washed with PBS, and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.0). After sonication on ice, the lysate was centrifuged under the same conditions. The supernatant was filtered (0.22 μm) and loaded onto a 1 mL HisTraTM HP column (Smart-Lifesciences, China) pre-equilibrated with buffer A (50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.0). The column was washed with buffer A, followed by elution using buffer A containing 500 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.0). Protein concentration was determined using a Modified Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Sango Biotech, Shanghai, China) with BSA as the standard.

4.10. DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing Assays

The DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing (DAP-seq) assay was conducted based on a previously described method [75] with minor modifications. Briefly, fresh spore suspensions of the P. oxalicum WT strain were cultured in VMMG liquid medium at 30 °C for 24 h. The mycelia were ground in liquid nitrogen, and genomic DNA was isolated via phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. The DNA was then broken into approximately 500 bp fragments by sonication at 35% power output.

The recombinant transcription factor protein was incubated with the fragmented genomic DNA library. Complexes of the target protein and bound DNA were isolated using His-labeled protein purified agarose magnetic beads (Beyotime, China), followed by digestion with Proteinase K (Vazyme, China) to release the DNA. The purified DNA fragments were used for library construction and sequenced on the DNBSEQ platform (BGI, Shenzhen, China).

Raw sequencing data from the DAP-seq were filtered to obtain clean reads, which were aligned to the reference genome using Bowtie2. The aligned results were visualized, and peak calling was performed with MACS2 to identify transcription factor binding sites. Genomic annotation of peaks was conducted to determine their distribution across functional elements. De novo motif analysis within the peak regions was carried out using the MEME suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme 5.5.9, accessed on 10 June 2024).

4.11. ChIP-qPCR Analysis

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were carried out with modifications based on established protocols [76,77]. In brief, hyphae grown in VMMG medium were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, and fixation was stopped by adding 125 mM of glycine for 5 min. The harvested hyphae were ground in liquid nitrogen and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail). After centrifugation, the collected chromatin was sonicated to an average size of approximately 500 bp at 35% power output.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) was conducted using an anti-HA antibody (Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA) and protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), with 1 mg of chromatin used per reaction. Both the obtained IP products and 0.1 mg input chromatin DNA (without IP) of each sample were treated with RNase, followed by a reversal of cross-links through heating and proteinase K digestion. Then, IP DNA and input DNA were purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. Quantitative PCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with primers listed in Supplementary S11. The relative enrichment of target DNA was calculated using the Input% method as follows (where Ct = the number of qPCR cycles required to reach the threshold):

ChIP efficiency = 2−ΔCt × 100%

ΔCt = CtIP − (CtInput − log210)

Three biological triplicates were performed for all strain samples.

5. Conclusions

The transcription factor PoCon7 is an essential regulator of fungal viability and a novel target of the SNF complex, specifically interacting with the Gal83 subunit. It directly controls chitinase expression by binding to the 5′-TATTWTTAT-3′ motif in the promoters of chitinase genes. PoCon7 governs the expression of a broad range of CWDE genes, including those encoding cellulases and hemicellulases, demonstrating its extensive regulatory function. These findings show the key role of PoCon7 in cell wall metabolism and its potential as a target for optimizing enzyme production in white biotechnology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27010333/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and Y.Q.; methodology, K.M. and H.Y.; formal analysis, K.M. and H.Y.; investigation, K.M.; data curation, J.Z. and Y.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.Q.; supervision, J.Z. and Y.Q.; project administration, Y.Q.; funding acquisition, Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (32370075) and Intramural Joint Program Fund of State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology (Project No. SKLMTIJP-2025-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Raw MS/MS data for TAP-MS are deposited in iProX (https://www.iprox.cn) under accession codes PXD068340. The raw data of transcriptome sequencing have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession numbers GSE308026.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gow, N.A.R. Fungal cell wall biogenesis: Structural complexity, regulation and inhibition. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2025, 179, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Ifuku, S.; Osaki, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Minami, S. Preparation and biomedical applications of chitin and chitosan nanofibers. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 10, 2891–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, A.; Ashour, A.A. Medicinal and Chemosensing Applications of Chitin-Based Materials: A Comprehensive Review. J. Fluoresc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holen, M.M.; Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Kent, M.P.; Sandve, S.R. Gene family expansion and functional diversification of chitinase and chitin synthase genes in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). G3 2023, 13, jkad069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenardon, M.D.; Munro, C.A.; Gow, N.A. Chitin synthesis and fungal pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrissat, B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem. J. 1991, 280, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.S.; Ghormade, V.V.; Deshpande, M.V. Chitinolytic enzymes: An exploration. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2000, 26, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.J. Fungal cell wall chitinases and glucanases. Microbiology 2004, 150, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Latge, J.P.; Munro, C.A. The Fungal Cell Wall: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Kupiec, R.; Chet, I. The molecular biology of chitin digestion. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1998, 9, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duo-Chuan, L. Review of fungal chitinases. Mycopathologia 2006, 161, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tian, B.; Liang, L.; Zhang, K.Q. Extracellular enzymes and the pathogenesis of nematophagous fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 75, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Fukamizo, T. Targeting Chitin-Containing Organisms, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Poopanitpan, N.; Piampratom, S.; Viriyathanit, P.; Lertvatasilp, T.; Horiuchi, H.; Fukuda, R.; Kiatwuthinon, P. SNF1 plays a crucial role in the utilization of n-alkane and transcriptional regulation of the genes involved in it in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghillebert, R.; Swinnen, E.; Wen, J.; Vandesteene, L.; Ramon, M.; Norga, K.; Rolland, F.; Winderickx, J. The AMPK/SNF1/SnRK1 fuel gauge and energy regulator: Structure, function and regulation. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 3978–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Park, E.-H.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, M.-D.; Yun, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-W. GzSNF1 is required for normal sexual and asexual development in the ascomycete Gibberella zeae. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnakumar, S.; Kacherovsky, N.; Arms, E.; Young, E.T. Snf1 Controls the Activity of Adr1 Through Dephosphorylation of Ser230. Genetics 2009, 182, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.H.; Gong, M.; Shang, J.J.; Zhang, J.S.; Mao, W.J.; Zou, G.; et al. Diverse function and regulation of CmSnf1 in entomopathogenic fungus Cordyceps militaris. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 142, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Wei, Q.; Jin, K.; Xia, Y. MaSnf1, a sucrose non-fermenting protein kinase gene, is involved in carbon source utilization, stress tolerance, and virulence in Metarhizium acridum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 10153–10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; He, P.H.; Feng, M.G.; Ying, S.H. BbSNF1 contributes to cell differentiation, extracellular acidification, and virulence in Beauveria bassiana, a filamentous entomopathogenic fungus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 8657–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Ouyang, B.; Wang, G.; Wei, C.; Zhao, X. Recent advances in genetic engineering to enhance plant-polysaccharide-degrading enzyme expression in Penicillium oxalicum: A brief review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.B.; Zhao, X.; Gao, P.J.; Wang, Z.N. Cellulase production from spent sulfite liquor and paper-mill waste fiber. Scientific note. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1991, 28–29, 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Zou, G.; Qin, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; et al. Genomic and secretomic analyses reveal unique features of the lignocellulolytic enzyme system of Penicillium decumbens. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandia, M.; Garrigues, S.; Bolos, B.; Manzanares, P.; Marcos, J.F. The Myosin Motor Domain-Containing Chitin Synthases Are Involved in Cell Wall Integrity and Sensitivity to Antifungal Proteins in Penicillium digitatum. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, S.; Li, D.; Peng, L.; Fan, G.; Pan, S. The plasma membrane H+-ATPase is critical for cell growth and pathogenicity in Penicillium digitatum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 5123–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwunnakorn, S.; Cooper, C.R.; Kummasook, A.; Vanittanakom, N. Role of the yakA gene in morphogenesis and stress response in Penicillium marneffei. Microbiology 2014, 160, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, O.; Caspary, F.; Rigaut, G.; Rutz, B.; Bouveret, E.; Bragado-Nilsson, E.; Wilm, M.; Seraphin, B. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: A general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods 2001, 24, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayram, O.; Krappmann, S.; Ni, M.; Bok, J.W.; Helmstaedt, K.; Valerius, O.; Braus-Stromeyer, S.; Kwon, N.J.; Keller, N.P.; Yu, J.H.; et al. VelB/VeA/LaeA complex coordinates light signal with fungal development and secondary metabolism. Science 2008, 320, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Song, X.; Qu, Y.; Qin, Y. Carbon catabolite repression involves physical interaction of the transcription factor CRE1/CreA and the Tup1-Cyc8 complex in Penicillium oxalicum and Trichoderma reesei. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihama, Y.; Oda, Y.; Tabata, T.; Sato, T.; Nagasu, T.; Rappsilber, J.; Mann, M. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2005, 4, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbreras, V.; Alba, M.M.; Kleinow, T.; Koncz, C.; Pages, M. Domain fusion between SNF1-related kinase subunits during plant evolution. EMBO Rep. 2001, 2, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenbach, D.; Breth, B.; Thines, E.; Weber, R.W.; Anke, H.; Foster, A.J. The transcription factor Con7p is a central regulator of infection-related morphogenesis in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 64, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Park, J.; Yang, L.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Son, H. Con7 is a key transcription regulator for conidiogenesis in the plant pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. mSphere 2024, 9, e00818-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.; Munday, M.R.; Scott, J.; Yang, X.; Carlson, M.; Carling, D. Yeast SNF1 is functionally related to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase and regulates acetyl-CoA carboxylase in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 19509–19515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, N.C.; Liu, L. Tracking STAT nuclear traffic. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Bao, L.; Gao, M.; Chen, M.; Lei, Y.; Liu, G.; Qu, Y. Penicillium decumbens BrlA extensively regulates secondary metabolism and functionally associates with the expression of cellulase genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 10453–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, L.; Gao, L.; Yao, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Li, F.; et al. Putative methyltransferase LaeA and transcription factor CreA are necessary for proper asexual development and controlling secondary metabolic gene cluster expression. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2016, 94, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihet, M.; Vandeputte, P.; Tronchin, G.; Renier, G.; Saulnier, P.; Georgeault, S.; Mallet, R.; Chabasse, D.; Symoens, F.; Bouchara, J.P. Melanin is an essential component for the integrity of the cell wall of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Qu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Qu, Y.; Qin, Y. Penicillium oxalicum putative methyltransferase Mtr23B has similarities and differences with LaeA in regulating conidium development and glycoside hydrolase gene expression. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 143, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qu, Y.; Qin, Y. Expression and chromatin structures of cellulolytic enzyme gene regulated by heterochromatin protein 1. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Zou, G.; Li, Z.; Yan, X.; Wei, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, L.; Zheng, K.; et al. Long-term strain improvements accumulate mutations in regulatory elements responsible for hyper-production of cellulolytic enzymes. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Estrada, C.; Ullan, R.V.; Albillos, S.M.; Fernandez-Bodega, M.A.; Durek, P.; Von Dohren, H.; Martin, J.F. A single cluster of coregulated genes encodes the biosynthesis of the mycotoxins roquefortine C and meleagrin in Penicillium chrysogenum. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gu, G.; Liu, G.; Su, J.; Zhan, Z.; Zhao, J.; Qian, J.; Cai, G.; Cen, S.; Zhang, D.; et al. Late-stage cascade of oxidation reactions during the biosynthesis of oxalicine B in Penicillium oxalicum. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, K.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S.; Song, X.; Qin, Y. F-box protein Fbx23 acts as a transcriptional coactivator to recognize and activate transcription factor Ace1. PLoS Genet. 2025, 21, e1011539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coradetti, S.T.; Craig, J.P.; Xiong, Y.; Shock, T.; Tian, C.; Glass, N.L. Conserved and essential transcription factors for cellulase gene expression in ascomycete fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7397–7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; He, X.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, G.; Qu, Y. Combinatorial Engineering of Transcriptional Activators in Penicillium oxalicum for Improved Production of Corn-Fiber-Degrading Enzymes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelepis, G.D.; Melin, P.; Jensen, D.F.; Stenlid, J.; Karlsson, M. Functional analysis of glycoside hydrolase family 18 and 20 genes in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2012, 49, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbaraini, N.; Junges, A.; De Oliveira, E.S.; Webster, A.; Vainstein, M.H.; Staats, C.C.; Schrank, A. The deletion of chiMaD1, a horizontally acquired chitinase of Metarhizium anisopliae, led to higher virulence towards the cattle tick (Rhipicephalus microplus). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2021, 368, fnab066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelepis, G.D.; Melin, P.; Stenlid, J.; Jensen, D.F.; Karlsson, M. Functional analysis of the C-II subgroup killer toxin-like chitinases in the filamentous ascomycete Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 64, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Meng, F.; Pang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Islam, M.A.; Xu, N.; Tian, Y.; Liu, J. Binding of the Magnaporthe oryzae Chitinase MoChia1 by a Rice Tetratricopeptide Repeat Protein Allows Free Chitin to Trigger Immune Responses. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.Y.; Noddings, C.M.; Kirschke, E.; Myasnikov, A.G.; Johnson, J.L.; Agard, D.A. Structure of Hsp90-Hsp70-Hop-GR reveals the Hsp90 client-loading mechanism. Nature 2022, 601, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.E.; Hipp, M.S.; Bracher, A.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F.U. Molecular chaperone functions in protein folding and proteostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 323–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, Z.; Szarka, M.; Kovacs, S.; Boczonadi, I.; Emri, T.; Abe, K.; Pocsi, I.; Pusztahelyi, T. Effect of cell wall integrity stress and RlmA transcription factor on asexual development and autolysis in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 54, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Zou, G.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Z. RNA Sequencing Reveals Xyr1 as a Transcription Factor Regulating Gene Expression beyond Carbohydrate Metabolism. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 4841756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokotani, N.; Tsuchida-Mayama, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Mitsuda, N.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Kaku, H.; Minami, E.; Nishizawa, Y. OsNAC111, a blast disease-responsive transcription factor in rice, positively regulates the expression of defense-related genes. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 2014, 27, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaever, G.; Chu, A.M.; Ni, L.; Connelly, C.; Riles, L.; Veronneau, S.; Dow, S.; Lucau-Danila, A.; Anderson, K.; Andre, B.; et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 2002, 418, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, N.; Yamazaki, D.; Horiuchi, H.; Ohta, A.; Takagi, M. Intracellular chitinase gene from Rhizopus oligosporus: Molecular cloning and characterization. Microbiology 1998, 144, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, N.; Yamazaki, D.; Horiuchi, H.; Ohta, A.; Takagi, M. Cloning and characterization of a chitinase-encoding gene (chiA) from Aspergillus nidulans, disruption of which decreases germination frequency and hyphal growth. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998, 62, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Chen, X. Potential biocontrol efficacy of Trichoderma atroviride with cellulase expression regulator ace1 gene knock-out. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulo, R.; Kokolski, M.; Archer, D.B. The roles of the zinc finger transcription factors XlnR, ClrA and ClrB in the breakdown of lignocellulose by Aspergillus niger. AMB Express 2016, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottola, A.; Schwanfelder, S.; Morschhauser, J. Generation of Viable Candida albicans Mutants Lacking the “Essential” Protein Kinase Snf1 by Inducible Gene Deletion. mSphere 2020, 5, e00805-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.; Inoue, H.; Ishikawa, K. Enhancing cellulase and hemicellulase production by genetic modification of the carbon catabolite repressor gene, creA, in Acremonium cellulolyticus. AMB Express 2013, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakari-Setala, T.; Paloheimo, M.; Kallio, J.; Vehmaanpera, J.; Penttila, M.; Saloheimo, M. Genetic modification of carbon catabolite repression in Trichoderma reesei for improved protein production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4853–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Cai, R.; Guo, J.; Zhong, Z.; Bao, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Lu, G.D. Carbon catabolite repressor MoCreA is required for the asexual development and pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2021, 146, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Carlson, M. Glucose regulates protein interactions within the yeast SNF1 protein kinase complex. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 3105–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Assis, L.J.; Silva, L.P.; Bayram, O.; Dowling, P.; Kniemeyer, O.; Kruger, T.; Brakhage, A.A.; Chen, Y.; Dong, L.; Tan, K.; et al. Carbon Catabolite Repression in Filamentous Fungi Is Regulated by Phosphorylation of the Transcription Factor CreA. mBio 2021, 12, e03146-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.J. A convenient growth medium for Neurospora (Medium N). Microbiol. Genet. Bull. 1956, 13, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; Mcgettigan, P.A.; Mcwilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Milpetz, F.; Bork, P.; Ponting, C.P. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: Identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5857–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.L.; Potter, S.C.; Punta, M.; Qureshi, M.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database: Towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D279–D285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayashiki, H.; Hanada, S.; Nguyen, B.Q.; Kadotani, N.; Tosa, Y.; Mayama, S. RNA silencing as a tool for exploring gene function in ascomycete fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturn, A.; Quackenbush, J.; Trajanoski, Z. Genesis: Cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.; O’malley, R.C.; Huang, S.C.; Galli, M.; Nery, J.R.; Gallavotti, A.; Ecker, J.R. Mapping genome-wide transcription-factor binding sites using DAP-seq. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Dominguez, Y.; Bok, J.W.; Berger, H.; Shwab, E.K.; Basheer, A.; Gallmetzer, A.; Scazzocchio, C.; Keller, N.; Strauss, J. Heterochromatic marks are associated with the repression of secondary metabolism clusters in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chujo, T.; Scott, B. Histone H3K9 and H3K27 methylation regulates fungal alkaloid biosynthesis in a fungal endophyte-plant symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 92, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.