Modulation of Mast Cell Activation via MRGPRX2 by Natural Oat Extract

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

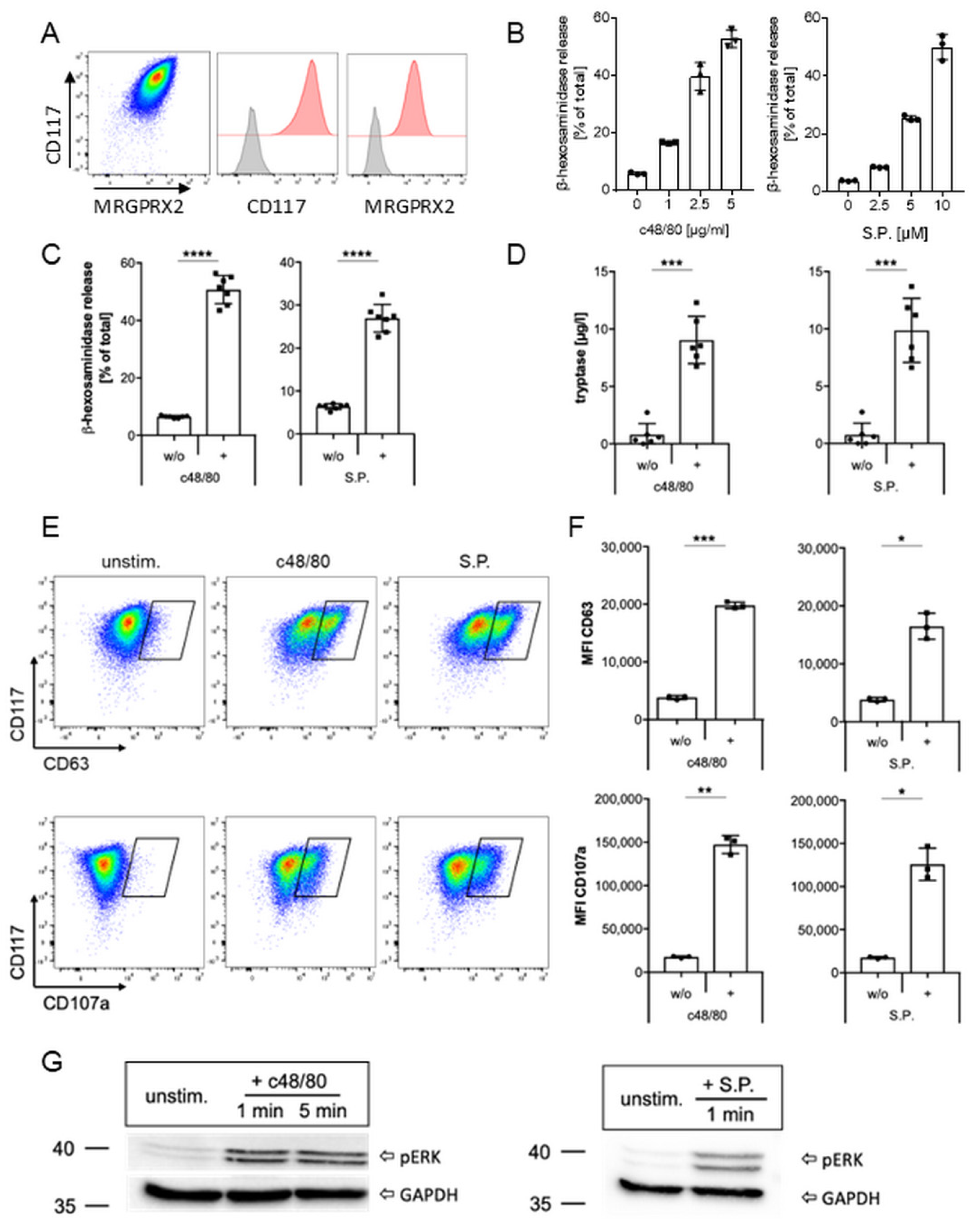

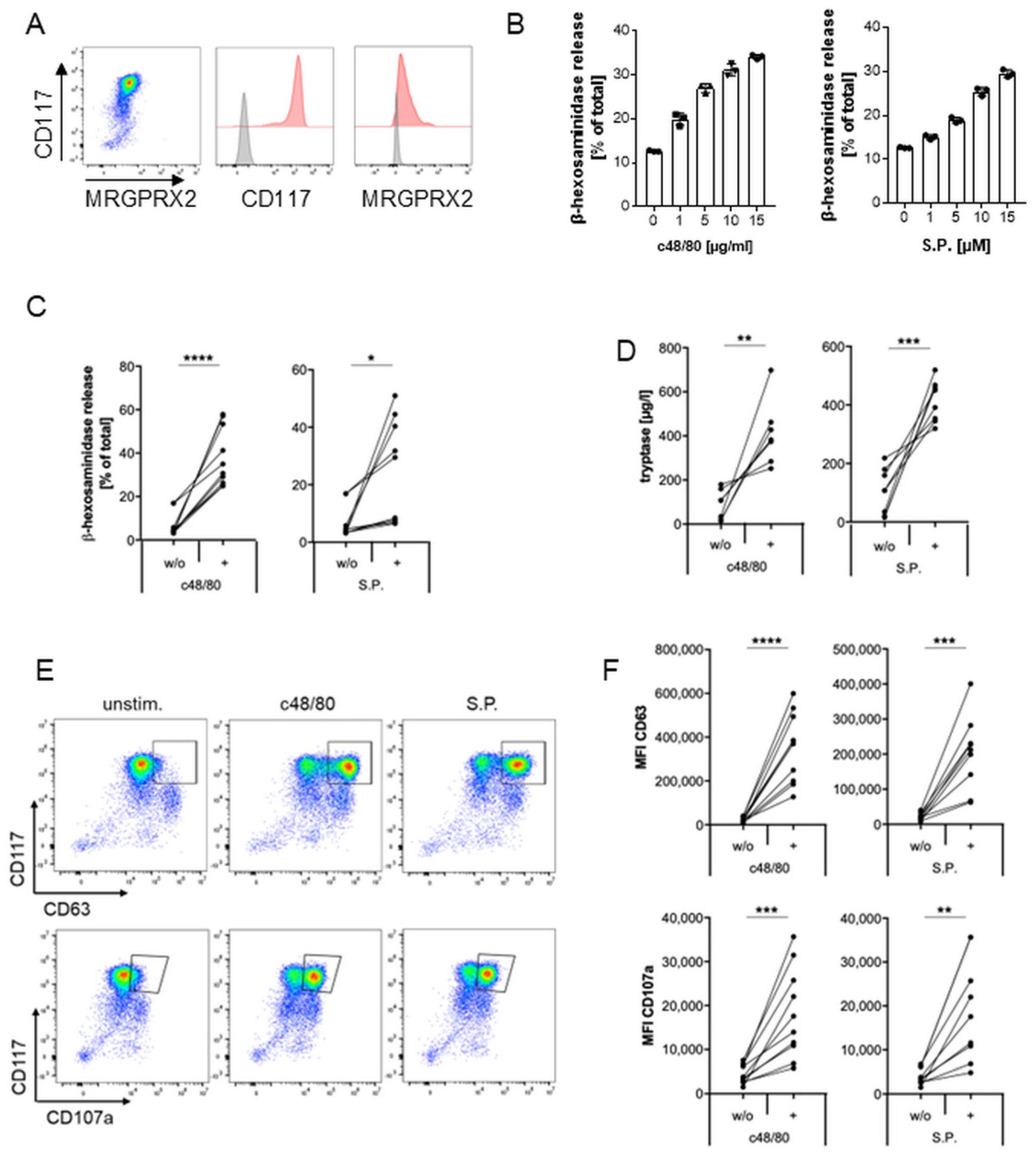

2.1. MRGPRX2 Expression and Activation in Human Mast Cell Line LAD2

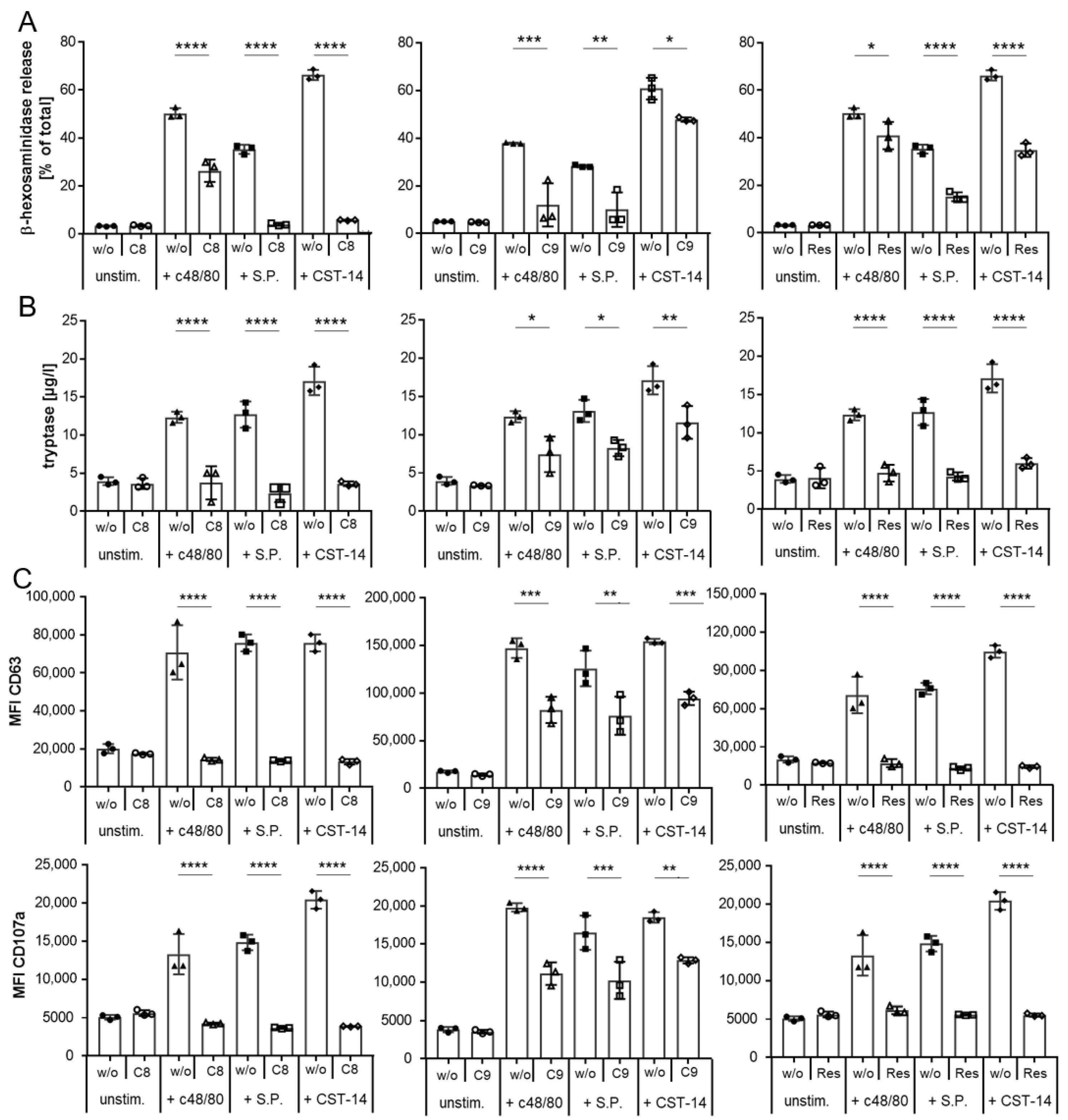

2.2. Inhibition of MRGPRX2 Activation in LAD2 Cells

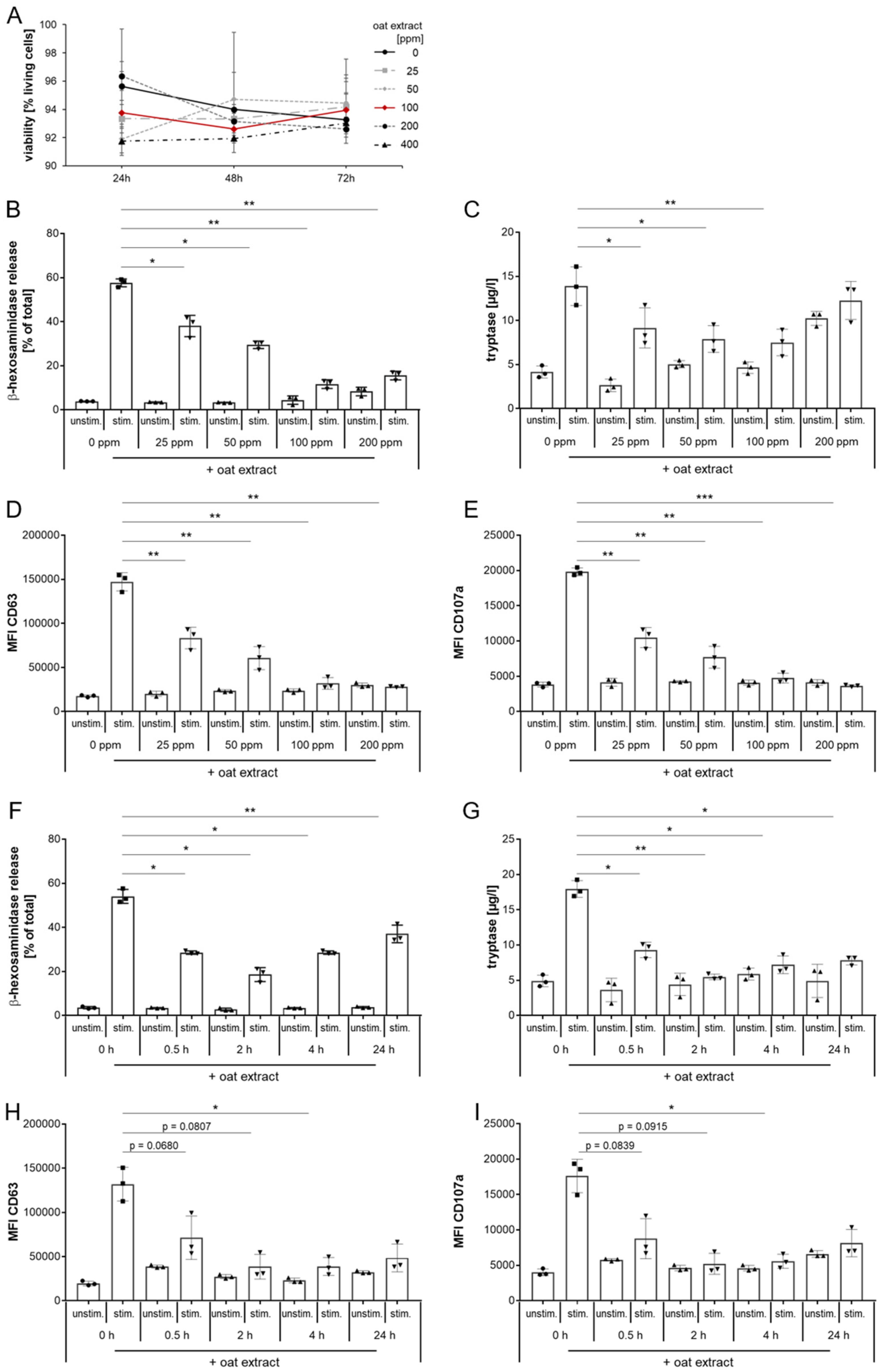

2.3. Evaluation of Oat Extract as a New Inhibitor of MRGPRX2 Activation with LAD2 Cells

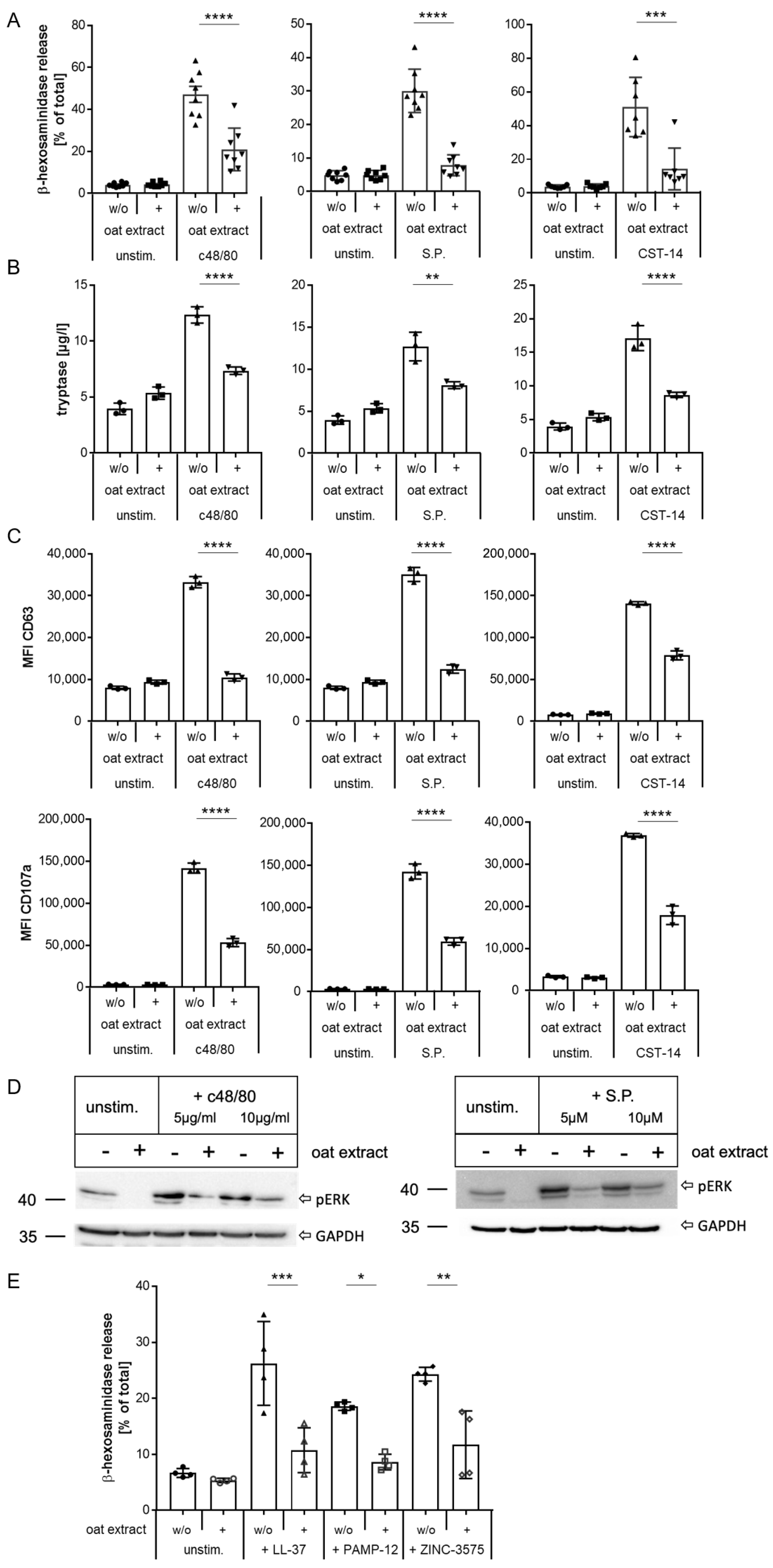

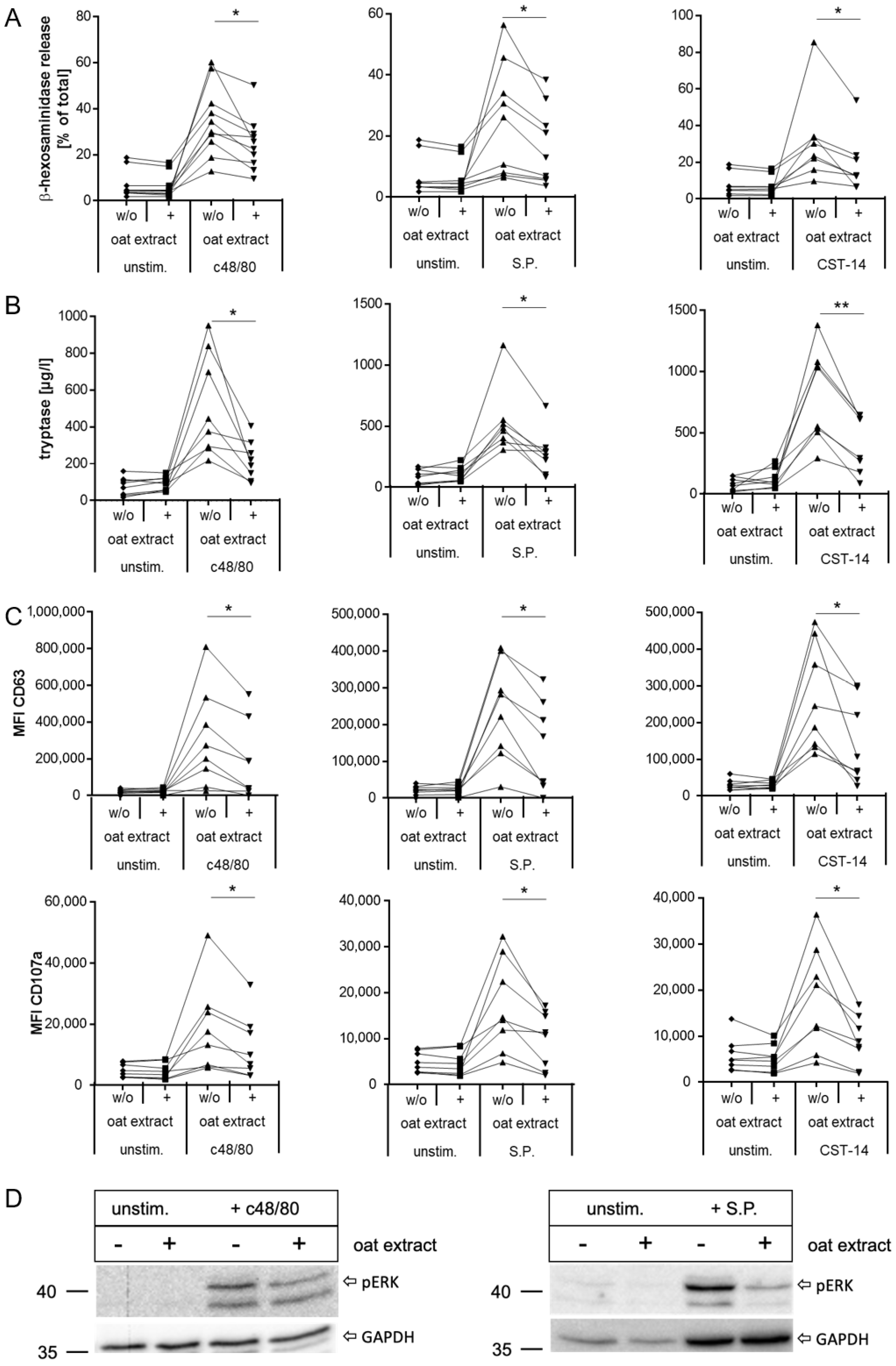

2.4. Inhibition of MRGPRX2 Activation in Human LAD2 Mast Cells by Oat Extract

2.5. Inhibition of MRGPRX2 Activation in Primary Human Mast Cells by Oat Extract

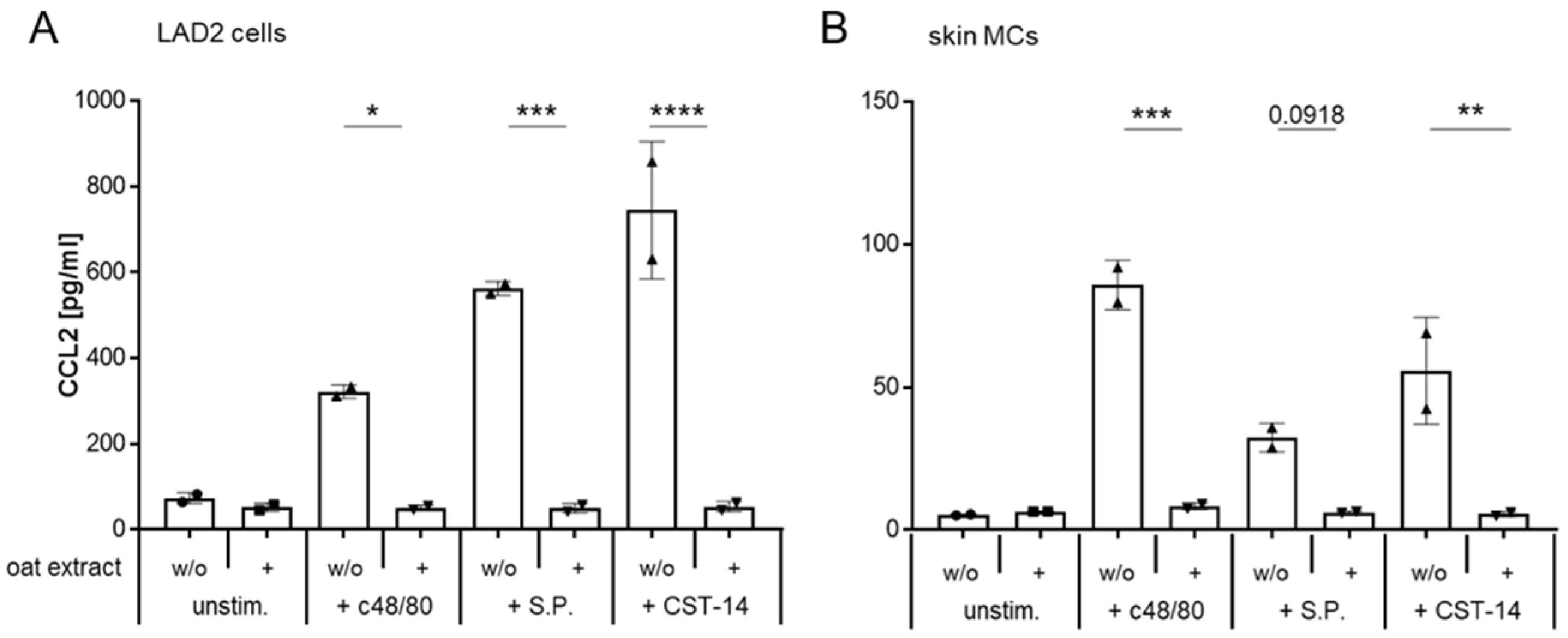

2.6. Oat Extract Inhibits the MRGPRX2-Induced Synthesis of CCL2 in LAD2 Cells and Primary Human Mast Cells

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Reagents

4.2. MC Stimulation

4.3. β-Hexosaminidase Assay

4.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis and Tryptase Measurement

4.5. CCL2 Assay

4.6. Western Blot

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MC | Mast Cell |

| MRGPRX2 | Mas-related G-protein coupled receptor X2 |

| MCT | Tryptase expressing MCs |

| MCTC | Tryptase- and chymase expressing MCs |

| FcεRI | Fcε receptor I |

| GPCR | G-protein coupled receptor |

| Avn | Avenanthramide |

| oat | Avena sativa |

| LAD2 | Laboratory of allergic disease 2 |

| CST-14 | Cortistatin 14 |

| S.P. | Substance P |

| c48/80 | Compound 48/80 |

| MFI | Mean fluorescence intensity |

| Res | resveratrol |

References

- Voehringer, D. Protective and pathological roles of mast cells and basophils. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudeck, A.; Koberle, M.; Goldmann, O.; Meyer, N.; Dudeck, J.; Lemmens, S.; Rohde, M.; Roldan, N.G.; Dietze-Schwonberg, K.; Orinska, Z.; et al. Mast cells as protectors of health. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, S4–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Chompunud Na Ayudhya, C.; Thapaliya, M.; Deepak, V.; Ali, H. Multifaceted MRGPRX2: New insight into the role of mast cells in health and disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, B.D.; Pundir, P.; Meeker, S.; Han, L.; Undem, B.J.; Kulka, M.; Dong, X. Identification of a mast-cell-specific receptor crucial for pseudo-allergic drug reactions. Nature 2015, 519, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Kang, H.J.; Singh, I.; Chen, H.; Zhang, C.; Ye, W.; Hayes, B.W.; Liu, J.; Gumpper, R.H.; Bender, B.J.; et al. Structure, function and pharmacology of human itch GPCRs. Nature 2021, 600, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, K.L.; Premont, R.T.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plum, T.; Wang, X.; Rettel, M.; Krijgsveld, J.; Feyerabend, T.B.; Rodewald, H.R. Human Mast Cell Proteome Reveals Unique Lineage, Putative Functions, and Structural Basis for Cell Ablation. Immunity 2020, 52, 404–416.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollam, J.; Solomon, M.; Villescaz, C.; Lanier, M.; Evans, S.; Bacon, C.; Freeman, D.; Vasquez, A.; Vest, A.; Napora, J.; et al. Inhibition of mast cell degranulation by novel small molecule MRGPRX2 antagonists. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Fang, G.X.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Yan, X.; et al. Structure, function and pharmacology of human itch receptor complexes. Nature 2021, 600, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Raimondi, F.; Kadji, F.M.N.; Singh, G.; Kishi, T.; Uwamizu, A.; Ono, Y.; Shinjo, Y.; Ishida, S.; Arang, N.; et al. Illuminating G-Protein-Coupling Selectivity of GPCRs. Cell 2019, 177, 1933–1947.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M.; Madden, M.; Oskeritzian, C.A. Mast Cells and Mas-related G Protein-coupled Receptor X2: Itching for Novel Pathophysiological Insights to Clinical Relevance. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2024, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Franke, K.; Bal, G.; Li, Z.; Zuberbier, T.; Babina, M. MRGPRX2-Mediated Degranulation of Human Skin Mast Cells Requires the Operation of Gαi, Gαq, Ca++ Channels, ERK1/2 and PI3K-Interconnection between Early and Late Signaling. Cells 2022, 11, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chompunud Na Ayudhya, C.; Roy, S.; Alkanfari, I.; Ganguly, A.; Ali, H. Identification of Gain and Loss of Function Missense Variants in MRGPRX2’s Transmembrane and Intracellular Domains for Mast Cell Activation by Substance P. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazki-Hagenbach, P.; Ali, H.; Sagi-Eisenberg, R. Authentic and Ectopically Expressed MRGPRX2 Elicit Similar Mechanisms to Stimulate Degranulation of Mast Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahri, R.; Custovic, A.; Korosec, P.; Tsoumani, M.; Barron, M.; Wu, J.; Sayers, R.; Weimann, A.; Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Patel, N.; et al. Mast cell activation test in the diagnosis of allergic disease and anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 485–496.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koberle, M.; Kaesler, S.; Kempf, W.; Wolbing, F.; Biedermann, T. Tetraspanins in mast cells. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Duraisamy, K.; Chow, B.K. Unlocking the Non-IgE-Mediated Pseudo-Allergic Reaction Puzzle with Mas-Related G-Protein Coupled Receptor Member X2 (MRGPRX2). Cells 2021, 10, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, B.A. MRGPRX2, drug pseudoallergies, inflammatory diseases, mechanisms and distinguishing MRGPRX2- and IgE/FcepsilonRI-mediated events. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 3232–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbiere, A.; Loste, A.; Gaudenzio, N. MRGPRX2 sensing of cationic compounds—A bridge between nociception and skin diseases? Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixiong, J.; Anderson, M.; Limjunyawong, N.; Sabbagh, M.F.; Hu, E.; Mack, M.R.; Oetjen, L.K.; Wang, F.; Kim, B.S.; Dong, X. Activation of Mast-Cell-Expressed Mas-Related G-Protein-Coupled Receptors Drives Non-histaminergic Itch. Immunity 2019, 50, 1163–1171.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, M.; Kaitani, A.; Izawa, K.; Ando, T.; Yoshikawa, A.; Nakamura, M.; Maehara, A.; Yamamoto, R.; Okamoto, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Neuronal substance P-driven MRGPRX2-dependent mast cell degranulation products differentially promote vascular permeability. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1477072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Alkanfari, I.; Chaki, S.; Ali, H. Role of MrgprB2 in Rosacea-Like Inflammation in Mice: Modulation by beta-Arrestin 2. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2988–2997.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtessel, M.; Limjunyawong, N.; Oliver, E.T.; Chichester, K.; Gao, L.; Dong, X.; Saini, S.S. MRGPRX2 Activation Causes Increased Skin Reactivity in Patients with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 678–681.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Cui, H.; Wang, T.; Shimada, S.G.; Sun, R.; Tan, Z.; Ma, C.; LaMotte, R.H. CCL2/CCR2 signaling elicits itch- and pain-like behavior in a murine model of allergic contact dermatitis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Choi, Y.G.; Wong, T.; Li, P.H.; Chow, B.K.C. Beyond the classic players: Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member X2 role in pruritus and skin diseases. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elieh-Ali-Komi, D.; Metz, M.; Kolkhir, P.; Kocaturk, E.; Scheffel, J.; Frischbutter, S.; Terhorst-Molawi, D.; Fox, L.; Maurer, M. Chronic urticaria and the pathogenic role of mast cells. Allergol. Int. 2023, 72, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattkemper, L.A.; Tey, H.L.; Valdes-Rodriguez, R.; Lee, H.; Mollanazar, N.K.; Albornoz, C.; Sanders, K.M.; Yosipovitch, G. The Genetics of Chronic Itch: Gene Expression in the Skin of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis with Severe Itch. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhu, D.; Franke, K.; Aparicio-Soto, M.; Kumari, V.; Pazur, K.; Illerhaus, A.; Hartmann, K.; Worm, M.; Babina, M. Mast cells instruct keratinocytes to produce thymic stromal lymphopoietin: Relevance of the tryptase/protease-activated receptor 2 axis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 2053–2061.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Babina, M. MRGPRX2 signals its importance in cutaneous mast cell biology: Does MRGPRX2 connect mast cells and atopic dermatitis? Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, H.; Noguchi, M. Therapeutic Potential of MRGPRX2 Inhibitors on Mast Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, N.; Shim, W.S. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibits pseudo-allergic reactions via inhibition of MRGPRX2/MrgprB2-dependent mast cell degranulation. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2022, 45, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, K.; Duraisamy, K.; Allam, A.A.; Ajarem, J.; Kwok Chong Chow, B. Protective Effect of Genistein against Compound 48/80 Induced Anaphylactoid Shock via Inhibiting MAS Related G Protein-Coupled Receptor X2 (MRGPRX2). Molecules 2020, 25, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capone, K.; Kirchner, F.; Klein, S.L.; Tierney, N.K. Effects of Colloidal Oatmeal Topical Atopic Dermatitis Cream on Skin Microbiome and Skin Barrier Properties. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diluvio, L.; Dattola, A.; Cannizzaro, M.V.; Franceschini, C.; Bianchi, L. Clinical and confocal evaluation of avenanthramides-based daily cleansing and emollient cream in pediatric population affected by atopic dermatitis and xerosis. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 154, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diluvio, L.; Piccolo, A.; Marasco, F.; Vollono, L.; Lanna, C.; Chiaramonte, B.; Niolu, C.; Campione, E.; Bianchi, L. Improving of psychological status and inflammatory biomarkers during omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Future Sci. OA 2020, 6, FSO618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilnytska, O.; Kaur, S.; Chon, S.; Reynertson, K.A.; Nebus, J.; Garay, M.; Mahmood, K.; Southall, M.D. Colloidal Oatmeal (Avena sativa) Improves Skin Barrier Through Multi-Therapy Activity. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2016, 15, 684–690. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaaji, A.N.; Wallo, W. A randomized controlled clinical study to evaluate the effectiveness of an active moisturizing lotion with colloidal oatmeal skin protectant versus its vehicle for the relief of xerosis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014, 13, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Lisante, T.A.; Nunez, C.; Zhang, P.; Mathes, B.M. A 1% Colloidal Oatmeal Cream Alone is Effective in Reducing Symptoms of Mild to Moderate Atopic Dermatitis: Results from Two Clinical Studies. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2017, 16, 671–676. [Google Scholar]

- Mengeaud, V.; Phulpin, C.; Bacquey, A.; Boralevi, F.; Schmitt, A.M.; Taieb, A. An innovative oat-based sterile emollient cream in the maintenance therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2015, 32, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynertson, K.A.; Garay, M.; Nebus, J.; Chon, S.; Kaur, S.; Mahmood, K.; Kizoulis, M.; Southall, M.D. Anti-inflammatory activities of colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa) contribute to the effectiveness of oats in treatment of itch associated with dry, irritated skin. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2015, 14, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, C.J.; Dubery, I.A. Avenanthramides, Distinctive Hydroxycinnamoyl Conjugates of Oat, Avena sativa L.: An Update on the Biosynthesis, Chemistry, and Bioactivities. Plants 2023, 12, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, H.; Yang, E.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.J.; Baek, M.C.; Lee, B.; Park, P.H.; Kwon, T.K.; Khang, D.; Song, K.S.; et al. Avenanthramide C from germinated oats exhibits anti-allergic inflammatory effects in mast cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sur, R.; Nigam, A.; Grote, D.; Liebel, F.; Southall, M.D. Avenanthramides, polyphenols from oats, exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-itch activity. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2008, 300, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Jun, S.H.; Jeong, E.T.; Kang, N.G. Dihydroavenanthramide D Enhances Skin Barrier Function through Upregulation of Epidermal Tight Junction Expression. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 9255–9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenbaum, A.S.; Akin, C.; Wu, Y.; Rottem, M.; Goff, J.P.; Beaven, M.A.; Rao, V.K.; Metcalfe, D.D. Characterization of novel stem cell factor responsive human mast cell lines LAD 1 and 2 established from a patient with mast cell sarcoma/leukemia; activation following aggregation of FcepsilonRI or FcgammaRI. Leuk. Res. 2003, 27, 677–682, Correction in Leuk. Res. 2003, 27, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkhir, P.; Pyatilova, P.; Ashry, T.; Jiao, Q.; Abad-Perez, A.T.; Altrichter, S.; Vera Ayala, C.E.; Church, M.K.; He, J.; Lohse, K.; et al. Mast cells, cortistatin, and its receptor, MRGPRX2, are linked to the pathogenesis of chronic prurigo. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1998–2009.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, L.; Babina, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Stevanovic, K. Beyond Allergies-Updates on The Role of Mas-Related G-Protein-Coupled Receptor X2 in Chronic Urticaria and Atopic Dermatitis. Cells 2024, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, M.; Krull, C.; Hawro, T.; Saluja, R.; Groffik, A.; Stanger, C.; Staubach, P.; Maurer, M. Substance P is upregulated in the serum of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2833–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena, G.A.; Cassano, N.; Di Leo, E.; Calogiuri, G.F.; Nettis, E. Focus on the role of substance P in chronic urticaria. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2018, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, H.; Gupta, K.; Guo, Q.; Price, R.; Ali, H. Mas-related gene X2 (MrgX2) is a novel G protein-coupled receptor for the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in human mast cells: Resistance to receptor phosphorylation, desensitization, and internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44739–44749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazir, M.; Amponnawarat, A.; Hui, Y.; Oskeritzian, C.A.; Ali, H. Inhibition of MRGPRX2 but not FcepsilonRI or MrgprB2-mediated mast cell degranulation by a small molecule inverse receptor agonist. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1033794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, S.; Ge, S.; Jia, M.; Wang, N. Resveratrol inhibits MRGPRX2-mediated mast cell activation via Nrf2 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 93, 107426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Raj, S.; Arizmendi, N.; Ding, J.; Eitzen, G.; Kwan, P.; Kulka, M.; Unsworth, L.D. Identification of short peptide sequences that activate human mast cells via Mas-related G-protein coupled receptor member X2. Acta Biomater. 2021, 136, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansu, K.; Karpiak, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.P.; McCorvy, J.D.; Kroeze, W.K.; Che, T.; Nagase, H.; Carroll, F.I.; Jin, J.; et al. In silico design of novel probes for the atypical opioid receptor MRGPRX2. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Schneikert, J.; Bal, G.; Jin, M.; Franke, K.; Zuberbier, T.; Babina, M. Intrinsic Regulatory Mechanisms Protect Human Skin Mast Cells from Excessive MRGPRX2 Activation: Paucity in LAD2 (Laboratory of Allergic Diseases 2) Cells Contributes to Hyperresponsiveness of the Mast Cell Line. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 145, 1215–1219.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhl, S.; Babina, M.; Neou, A.; Zuberbier, T.; Artuc, M. Mast cell lines HMC-1 and LAD2 in comparison with mature human skin mast cells—Drastically reduced levels of tryptase and chymase in mast cell lines. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 845–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.P.; Limjunyawong, N.; Gour, N.; Pundir, P.; Dong, X. A Mast-Cell-Specific Receptor Mediates Neurogenic Inflammation and Pain. Neuron 2019, 101, 412–420.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwandtner, M.; Derler, R.; Midwood, K.S. More Than Just Attractive: How CCL2 Influences Myeloid Cell Behavior Beyond Chemotaxis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, R.E.; Echevarria, F.D. Macrophage biology in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 173, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Bal, G.; Franke, K.; Zuberbier, T.; Babina, M. beta-arrestin-1 and beta-arrestin-2 Restrain MRGPRX2-Triggered Degranulation and ERK1/2 Activation in Human Skin Mast Cells. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 930233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, M.; Wang, Z.; Roy, S.; Guhl, S.; Franke, K.; Artuc, M.; Ali, H.; Zuberbier, T. MRGPRX2 Is the Codeine Receptor of Human Skin Mast Cells: Desensitization through beta-Arrestin and Lack of Correlation with the FcepsilonRI Pathway. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1286–1296.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chompunud Na Ayudhya, C.; Amponnawarat, A.; Ali, H. Substance P Serves as a Balanced Agonist for MRGPRX2 and a Single Tyrosine Residue Is Required for beta-Arrestin Recruitment and Receptor Internalization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robas, N.; Mead, E.; Fidock, M. MrgX2 is a high potency cortistatin receptor expressed in dorsal root ganglion. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44400–44404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, P.W.; Cheret, J.; Bahri, R.; Kiss, O.; Wu, Z.; Macphee, C.H.; Bulfone-Paus, S. The MRGPRX2-substance P pathway regulates mast cell migration. iScience 2024, 27, 110984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, M.; Wang, Z.; Franke, K.; Guhl, S.; Artuc, M.; Zuberbier, T. Yin-Yang of IL-33 in Human Skin Mast Cells: Reduced Degranulation, but Augmented Histamine Synthesis through p38 Activation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1516–1525.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varricchi, G.; Pecoraro, A.; Loffredo, S.; Poto, R.; Rivellese, F.; Genovese, A.; Marone, G.; Spadaro, G. Heterogeneity of Human Mast Cells with Respect to MRGPRX2 Receptor Expression and Function. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guhl, S.; Franke, K.; Artuc, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Babina, M. IL-33 and MRGPRX2-Triggered Activation of Human Skin Mast Cells-Elimination of Receptor Expression on Chronic Exposure, but Reinforced Degranulation on Acute Priming. Cells 2019, 8, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieven, T.; Goossens, J.; Roosens, W.; Jonckheere, A.C.; Cremer, J.; Dilissen, E.; Persoons, R.; Dupont, L.; Schrijvers, R.; Vandenberghe, P.; et al. Functional MRGPRX2 expression on peripheral blood-derived human mast cells increases at low seeding density and is suppressed by interleukin-9 and fetal bovine serum. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1506034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkanfari, I.; Gupta, K.; Jahan, T.; Ali, H. Naturally Occurring Missense MRGPRX2 Variants Display Loss of Function Phenotype for Mast Cell Degranulation in Response to Substance P, Hemokinin-1, Human beta-Defensin-3, and Icatibant. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.B.; Graham, T.A.; Azimi, E.; Lerner, E.A. A single amino acid in MRGPRX2 necessary for binding and activation by pruritogens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 1726–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Guo, J.; Yang, M.; Niu, X.; Wang, X.; Yuan, J.; Ren, J.; et al. MRGPRX2 gain-of-function mutation drives enhanced mast cell reactivity in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 156, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, P.L.; Olle, L.; Sabate-Bresco, M.; Guruceaga, E.; Laguna, J.J.; Dona, I.; Munoz-Cano, R.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Martin, M.; Gastaminza, G. Variants of the MRGPRX2 Gene Found in Patients with Hypersensitivity to Quinolones and Vancomycin Show Amplified and Drug-Specific Activation Responses In Vitro. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2025, 55, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cop, N.; Decuyper, II; Faber, M.A.; Sabato, V.; Bridts, C.H.; Hagendorens, M.M.; De Winter, B.Y.; De Clerck, L.S.; Ebo, D.G. Phenotypic and functional characterization of in vitro cultured human mast cells. Cytom. Part B Clin. Cytom. 2017, 92, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, M.; Guhl, S.; Artuc, M.; Trivedi, N.N.; Zuberbier, T. Phenotypic variability in human skin mast cells. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuliano, C.; Absmaier-Kijak, M.; Sinnberg, T.; Hoffard, N.; Hils, M.; Koberle, M.; Wolbing, F.; Shumilina, E.; Heise, N.; Fehrenbacher, B.; et al. Fetal Tissue-Derived Mast Cells (MC) as Experimental Surrogate for In Vivo Connective Tissue MC. Cells 2022, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kaesler, S.; Argiriu, D.; Kandage, S.M.; Schönfeldt, K.; Lekiashvili, S.; Dengiz, C.N.; Ercan, N.; Iuliano, C.; Herrmann, M.; Reichenbach, M.; et al. Modulation of Mast Cell Activation via MRGPRX2 by Natural Oat Extract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010334

Kaesler S, Argiriu D, Kandage SM, Schönfeldt K, Lekiashvili S, Dengiz CN, Ercan N, Iuliano C, Herrmann M, Reichenbach M, et al. Modulation of Mast Cell Activation via MRGPRX2 by Natural Oat Extract. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010334

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaesler, Susanne, Désirée Argiriu, Shyami M. Kandage, Karla Schönfeldt, Shalva Lekiashvili, Ceren N. Dengiz, Neslim Ercan, Caterina Iuliano, Martina Herrmann, Maria Reichenbach, and et al. 2026. "Modulation of Mast Cell Activation via MRGPRX2 by Natural Oat Extract" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010334

APA StyleKaesler, S., Argiriu, D., Kandage, S. M., Schönfeldt, K., Lekiashvili, S., Dengiz, C. N., Ercan, N., Iuliano, C., Herrmann, M., Reichenbach, M., Cichowski, D., Babina, M., Hils, M., Köberle, M., & Biedermann, T. (2026). Modulation of Mast Cell Activation via MRGPRX2 by Natural Oat Extract. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010334