Mitochondrial Transplantation Restores Immune Cell Metabolism in Sepsis: A Metabolomics Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Quality Control of Isolated Mitochondria

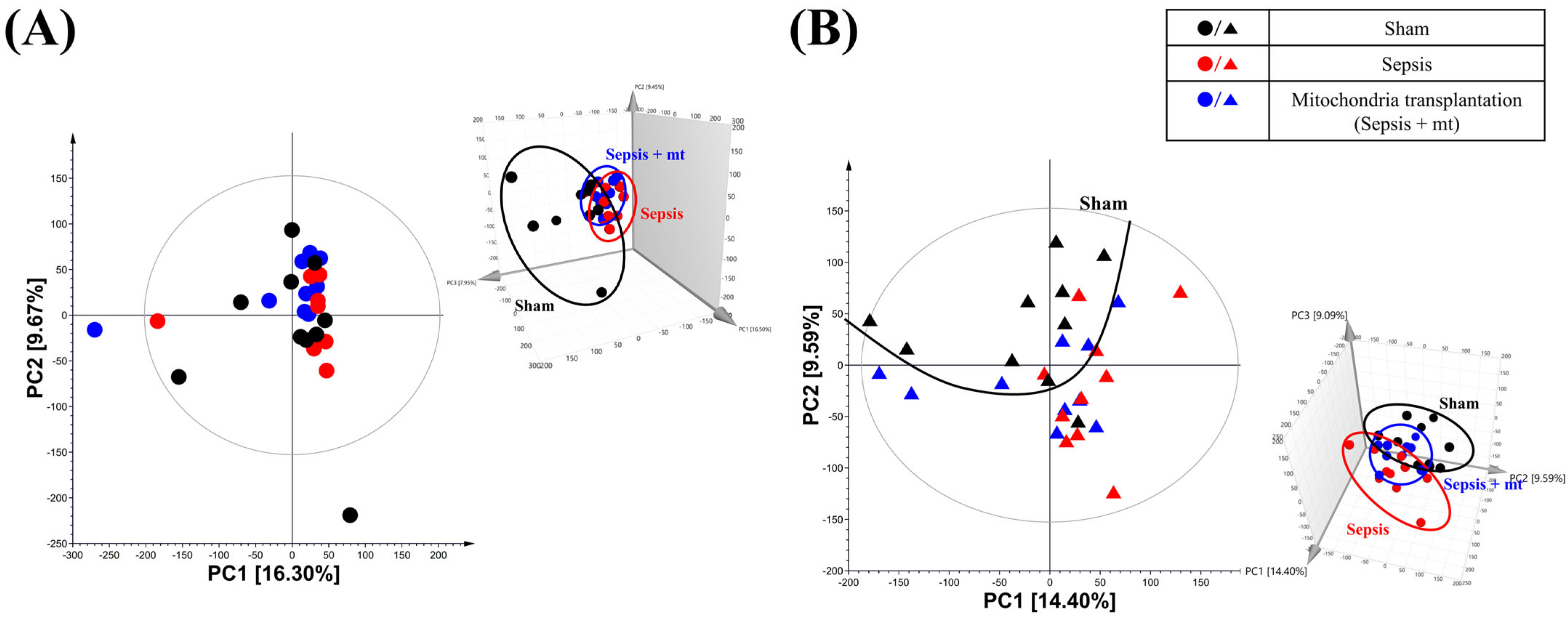

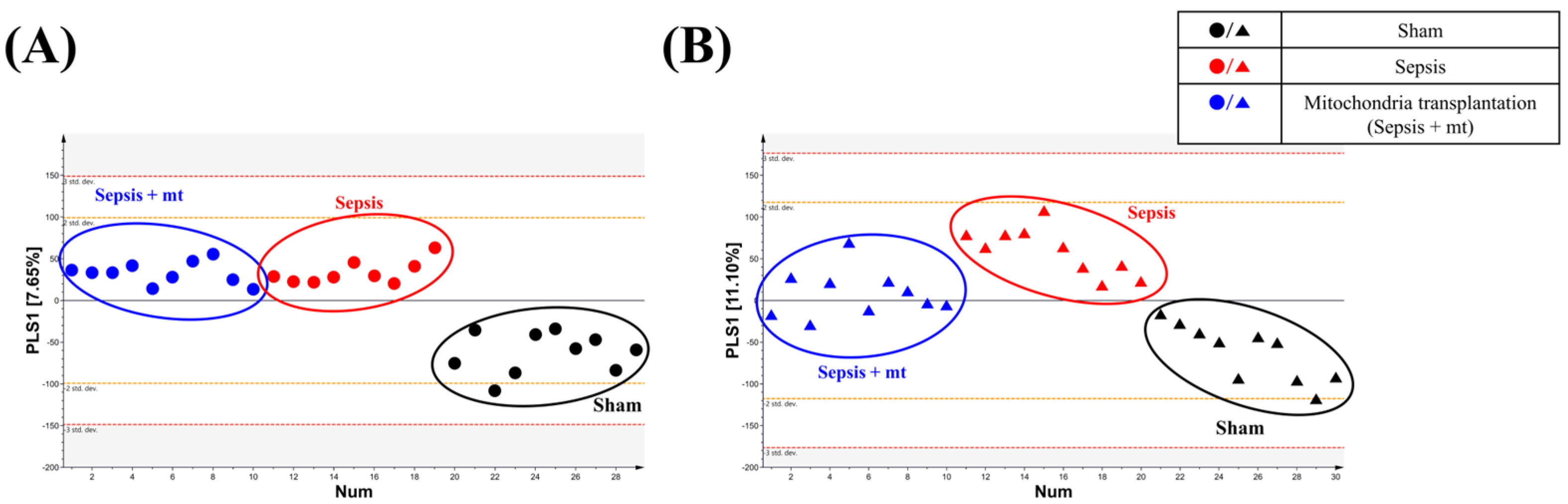

2.2. Global Metabolic Profile Distinction

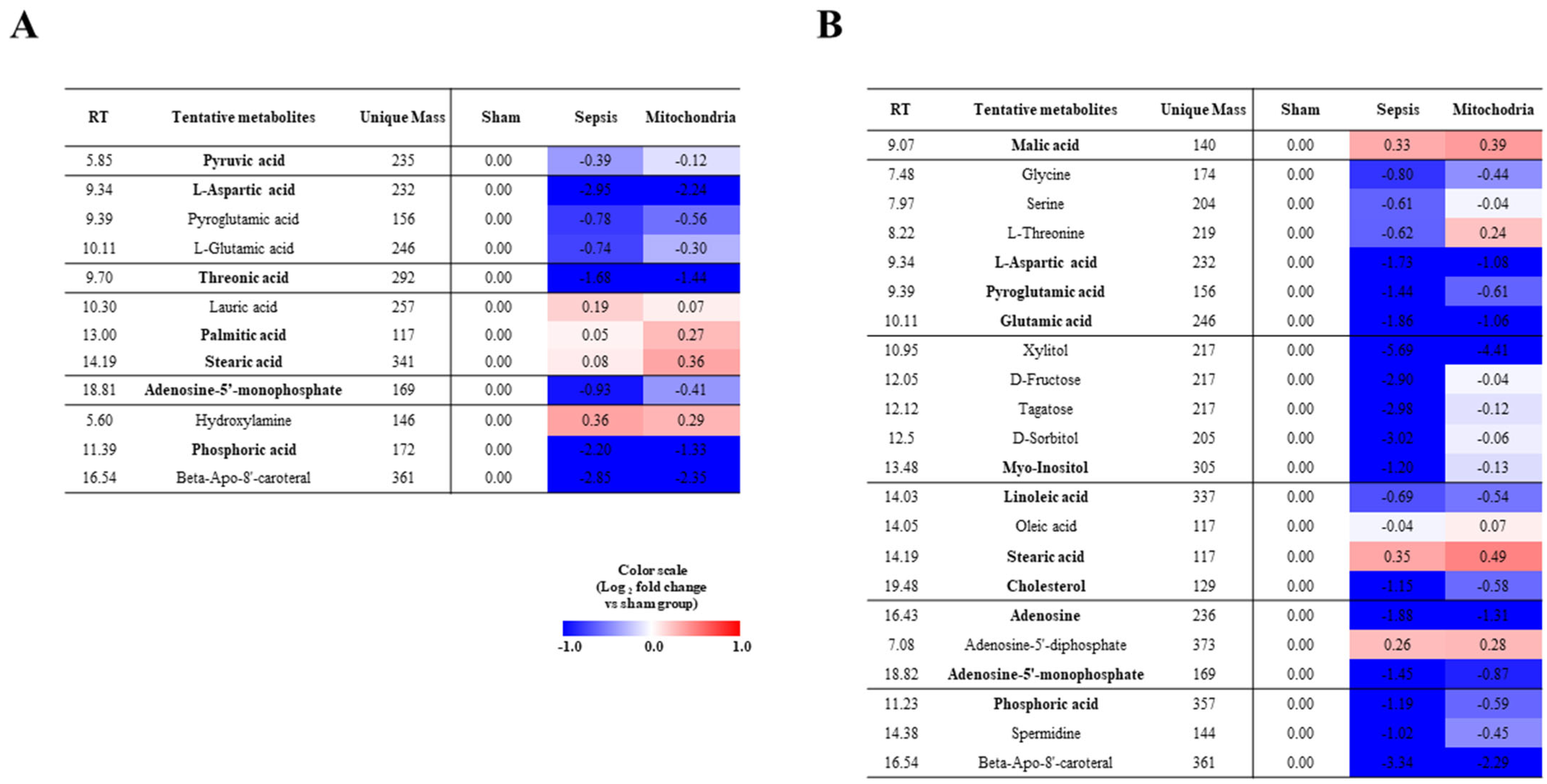

2.3. Heatmap Analysis Associated with the Altered Metabolites

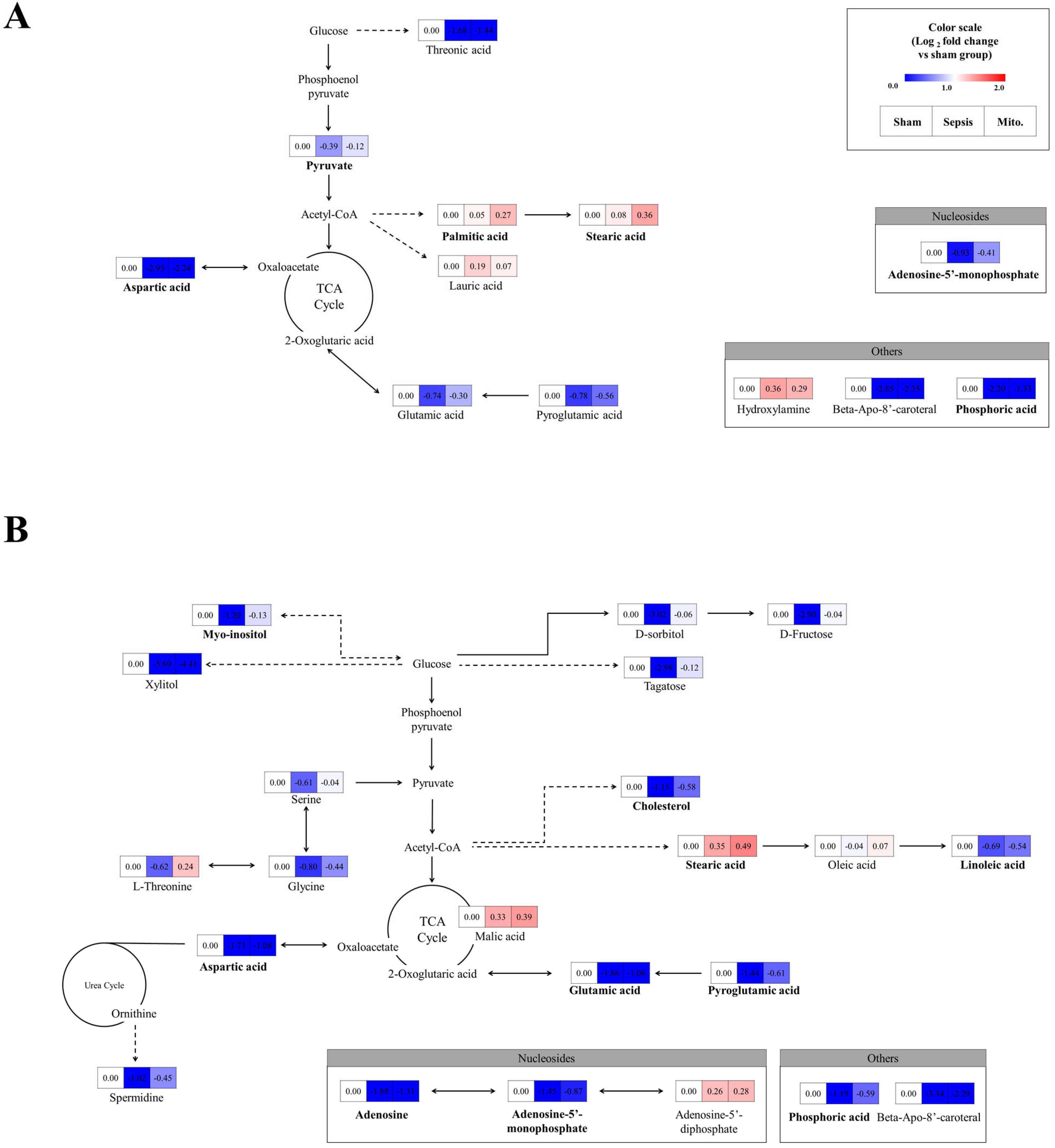

2.4. Effect of Sepsis and Mitochondrial Transplantation on the Metabolic Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. In Vivo Sepsis Model

4.2. Mitochondria Isolation and Quality Control

4.3. Metabolomics Study

4.3.1. Extraction of Animal Samples for Metabolomics

4.3.2. Gas Chromatography-Time-of-Flight-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

4.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meyer, N.J.; Prescott, H.C. Sepsis and Septic Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, G.B.D.G.S. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e2013–e2026. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, T.G.; Ko, E.; Han, S.H.; Kim, T.; Choi, D.H. Epidemiology of sepsis in emergency departments: Insights from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) database in Korea, 2018–2022. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2025, 12, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, C.E.; Zhu, X.; Zabalawi, M.; Long, D.; Quinn, M.A.; Yoza, B.K.; Stacpoole, P.W.; Vachharajani, V. Sepsis, pyruvate, and mitochondria energy supply chain shortage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 112, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, V.L.S.; Alvares-Saraiva, A.M.; Serdan, T.D.A.; Dos Santos-Oliveira, L.C.; Cruzat, V.; Lobato, T.B.; Manoel, R.; Alecrim, A.L.; Machado, O.A.; Hirabara, S.M.; et al. Essential metabolism required for T and B lymphocyte functions: An update. Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.L.; Sousa, M.B.; Leite, G.G.F.; Brunialti, M.K.C.; Nishiduka, E.S.; Tashima, A.K.; van der Poll, T.; Salomao, R. Glucose metabolism is upregulated in the mononuclear cell proteome during sepsis and supports endotoxin-tolerant cell function. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1051514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciolek, J.A.; Pasternak, J.A.; Wilson, H.L. Metabolism of activated T lymphocytes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 27, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira Chavez, F.M.; Gartzke, L.P.; van Beuningen, F.E.; Wink, S.E.; Henning, R.H.; Krenning, G.; Bouma, H.R. Restoring the infected powerhouse: Mitochondrial quality control in sepsis. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, T.M.; Pereira, A.J.; Schurch, R.; Schefold, J.C.; Jakob, S.M.; Takala, J.; Djafarzadeh, S. Mitochondrial function of immune cells in septic shock: A prospective observational cohort study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.L.; Zhang, D.; Bush, J.; Graham, K.; Starr, J.; Murray, J.; Tuluc, F.; Henrickson, S.; Deutschman, C.S.; Becker, L.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction is Associated with an Immune Paralysis Phenotype in Pediatric Sepsis. Shock 2020, 54, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Filppula, A.; Cui, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhang, H. Encapsulated mitochondria to reprogram the metabolism of M2-type macrophages for anti-tumor therapy. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 20925–20939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.H.; Sagullo, E.; Case, D.; Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Hong, J.S.; TeSlaa, T.; Patananan, A.N.; McCaffery, J.M.; Niazi, K.; et al. Mitochondrial Transfer by Photothermal Nanoblade Restores Metabolite Profile in Mammalian Cells. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.W.; Lee, M.J.; Chung, T.N.; Lee, H.A.R.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, C.H.; Jin, I.; Kim, S.H.; et al. The immune modulatory effects of mitochondrial transplantation on cecal slurry model in rat. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yan, C.; Miao, J.; Pu, K.; Ma, H.; Wang, Q. Muscle-Derived Mitochondrial Transplantation Reduces Inflammation, Enhances Bacterial Clearance, and Improves Survival in Sepsis. Shock 2021, 56, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qi, Z.; Cao, L.; Ding, S. Mitochondrial transfer/transplantation: An emerging therapeutic approach for multiple diseases. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. Metabolomics for Investigating Physiological and Pathophysiological Processes. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1819–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Sheeja Prabhakaran, H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Luo, G.; He, W.; Liou, Y.C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.A.; Owen, A.M.; Stothers, C.L.; Hernandez, A.; Luan, L.; Burelbach, K.R.; Patil, T.K.; Bohannon, J.K.; Sherwood, E.R.; Patil, N.K. The Metabolic Basis of Immune Dysfunction Following Sepsis and Trauma. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyttens, L.; Heyerick, M.; Heremans, G.; Moens, E.; Roes, M.; Van Dender, C.; De Bus, L.; Decruyenaere, J.; Dewaele, J.; Vandewalle, J.; et al. Unraveling mitochondrial pyruvate dysfunction to mitigate hyperlactatemia and lethality in sepsis. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, M.L.; Quon, E.; Vigil, A.B.G.; Engstrom, I.A.; Newsom, O.J.; Davidsen, K.; Hoellerbauer, P.; Carlisle, S.M.; Sullivan, L.B. Mitochondrial redox adaptations enable alternative aspartate synthesis in SDH-deficient cells. Elife 2023, 12, e78654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, V.; Benkovic, S. Metabolic profiling reveals channeled de novo pyrimidine and purine biosynthesis fueled by mitochondrially generated aspartic acid in cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Montgomery, M.K. Physiological roles of phosphoinositides and inositol phosphates: Implications for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 1095–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B.; Szablinska-Piernik, J.; Lahuta, L.B.; Gromadzinski, L.; Majewski, M.S. Antioxidant and anticoagulant properties of myo-inositol determined in an ex vivo studies and gas chromatography analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.; Case, K.C.; Schmidtke, M.W.; Lazcano, P.; Onu, C.J.; Greenberg, M.L. Inositol depletion regulates phospholipid metabolism and activates stress signaling in HEK293T cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2022, 1867, 159137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belew, G.D.; Di Nunzio, G.; Tavares, L.; Silva, J.G.; Torres, A.N.; Jones, J.G. Estimating pentose phosphate pathway activity from the analysis of hepatic glycogen (13) C-isotopomers derived from [U-(13) C]fructose and [U-(13) C]glucose. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020, 84, 2765–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, S.J.; Breton, I.; Decombaz, J.; Boesch, C.; Scheurer, E.; Montoliu, I.; Rezzi, S.; Kochhar, S.; Guy, P.A. A plasma global metabolic profiling approach applied to an exercise study monitoring the effects of glucose, galactose and fructose drinks during post-exercise recovery. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2010, 878, 3015–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K. Recent Progress on Fructose Metabolism-Chrebp, Fructolysis, and Polyol Pathway. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Lee, H.A.R.; Lee, M.J.; Park, Y.J.; Mun, S.; Yune, C.J.; Chung, T.N.; Bae, J.; Kim, M.J.; Choi, Y.S.; et al. The Effects of Mitochondrial Transplantation on Sepsis Depend on the Type of Cell from Which They Are Isolated. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Lee, S.H.; Chung, K.S.; Ku, N.S.; Hyun, Y.M.; Chun, S.; Park, M.S.; Lee, S.G. Development and validation of a novel sepsis biomarker based on amino acid profiling. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3668–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Liang, X.; Wu, T.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ruan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, P.; et al. Integrative analysis of metabolomics and proteomics reveals amino acid metabolism disorder in sepsis. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 123, Erratum in: J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 366.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, M. Metabolomics-based study of potential biomarkers of sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, C.; Vorbach, H.; Robibaro, B.; Schaumann, R.; Buxbaum, A.; Reiter, M.; Georgopoulos, A. Effects of imipenem and meropenem on purine content of endothelial cells. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 37, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Chamkha, I.; Elmer, E.; Sjovall, F.; Ehinger, J.K. Antibiotic-induced mitochondrial dysfunction: Exploring tissue-specific effects on HEI-OC1 cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2025, 1869, 130832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Z.; Kong, W.; Feng, L. Mitochondrial Transplantation: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for Treating Diseases. MedComm (2020) 2025, 6, e70253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubinin, M.V.; Mikheeva, I.B.; Stepanova, A.E.; Igoshkina, A.D.; Cherepanova, A.A.; Semenova, A.A.; Sharapov, V.A.; Kireev, I.I.; Belosludtsev, K.N. Mitochondrial Transplantation Therapy Ameliorates Muscular Dystrophy in mdx Mouse Model. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Kim, M.; Ko, S.H.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, M.; Park, C.H. Primary astrocytic mitochondrial transplantation ameliorates ischemic stroke. BMB Rep. 2023, 56, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhu, F. Non-linear relationship between ionised calcium and 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis: A retrospective cohort study from MIMIC-IV database. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e099781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Bai, H.; Zong, Y. The association between ionized calcium level and 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis: A cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brestoff, J.R.; Singh, K.K.; Aquilano, K.; Becker, L.B.; Berridge, M.V.; Boilard, E.; Caicedo, A.; Crewe, C.; Enriquez, J.A.; Gao, J.; et al. Recommendations for mitochondria transfer and transplantation nomenclature and characterization. Nat. Metab. 2025, 7, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kim, K.; Jo, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, J.E. Dose-dependent mortality and organ injury in a cecal slurry peritonitis model. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 206, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.H.; Son, S.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Ha, T.W.; Im, J.S.; Ryu, A.; Jeon, H.; Chung, H.Y.; Oh, J.S.; Lee, C.H.; et al. Profiling of Metabolic Differences between Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Acute/Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Metabolites 2020, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, I.G.; Lee, M.Y.; Jeon, S.H.; Huh, E.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, C.H.; Oh, M.S. GC-TOF-MS-Based Metabolomic Analysis and Evaluation of the Effects of HX106, a Nutraceutical, on ADHD-Like Symptoms in Prenatal Alcohol Exposed Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, S.Y.; Park, Y.J.; Jung, E.S.; Singh, D.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, C.H. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Unravel the Metabolic Pathway Variations for Different Sized Beech Mushrooms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chung, T.N.; Choi, S.R.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, K. Mitochondrial Transplantation Restores Immune Cell Metabolism in Sepsis: A Metabolomics Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010332

Chung TN, Choi SR, Kim S-H, Lee CH, Kim K. Mitochondrial Transplantation Restores Immune Cell Metabolism in Sepsis: A Metabolomics Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010332

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Tae Nyoung, Se Rin Choi, Su-Hyun Kim, Choong Hwan Lee, and Kyuseok Kim. 2026. "Mitochondrial Transplantation Restores Immune Cell Metabolism in Sepsis: A Metabolomics Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010332

APA StyleChung, T. N., Choi, S. R., Kim, S.-H., Lee, C. H., & Kim, K. (2026). Mitochondrial Transplantation Restores Immune Cell Metabolism in Sepsis: A Metabolomics Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010332