Abstract

Mass spectrometry has become an indispensable tool for the identification and quantification of epigenetic modifications, offering both high sensitivity and structural specificity. The two major classes of epigenetic modifications identified—DNA methylation and histone post-translational modifications—play fundamental roles in cancer development, underscoring the relevance of their precise quantification for understanding tumorigenesis and potential therapeutic targeting. In this scoping review, we included 89 studies that met the inclusion criteria for detailed methodological assessment. Among these, we compared pre-treatment workflows, analytical platforms, and acquisition modes employed to characterize epigenetic modifications in human samples and model systems. Our synthesis highlights the predominance of bottom-up strategies combined with Orbitrap-based platforms and data-dependent acquisition for histone post-translational modifications, whereas triple quadrupole mass spectrometers were predominant for DNA methylation quantification. We critically evaluate current limitations, including heterogeneity in validation reporting, insufficient coverage of combinatorial post-translational modifications, and variability in derivatization efficiency.

1. Introduction

DNA plays a pivotal role in transmitting all the genetic information required for the correct development, function, growth and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses. Consequently, it is fundamental in shaping biological phenotypes and orchestrating the intricate process of life. Changes in its composition, sequence, or structure can cause a variety of physiological dysfunctions. DNA stability and integrity are crucial for proper cellular functioning and the accurate transmission of hereditary traits across generations. Deviations from the normal state of DNA can have serious consequences for an organism’s health and well-being, leading to a wide range of pathologies, including genetic diseases and cancers [1].

Recently, there has been a growing interest in understanding the mechanisms by which DNA modifications arise and how they affect the structure and function of DNA. The final goal is to gain a comprehensive understanding of their broader implications in both normal physiological processes and disease states. Epigenetics is often defined as functionally relevant changes to the genome that occur without altering the nucleotide sequence [2]. Key mechanisms responsible for these phenomena include: DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling [3]. Techniques such as chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (Chip-seq), bisulfite sequencing, methylated DNA immunoprecipitation, and chromosome conformation capture have been instrumental in improving our understanding of the epigenetic regulation of gene expression [4]. In addition, advances in mass spectrometry (MS) technologies have greatly improved the analysis of epigenetic DNA damage and modifications.

Of all the epigenetic modifications, DNA methylation is the most widely studied. DNA methylation patterns are highly dysregulated in cancer. In fact, changes in methylation status have been postulated to inactivate tumor suppressors and activate oncogenes, thus contributing to tumorigenesis [5]. Currently, there are three main groups of techniques that involve the identification of specific regions that are differentially methylated: bisulfite conversion-based methods, restriction enzyme-based approaches, and affinity enrichment-based assays [6].

In addition to noncanonical bases that are actively generated for partially unknown purposes, genomic DNA (gDNA) contains modified bases that are generated as DNA lesions. In particular, oxidative DNA lesions such as 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-deoxyguanosine (8oxodG) can easily form [7], and the levels of such base lesions can correlate with diseases [8]. Although 5-Methyl-2′-deoxycytidine (5mdC) is the most abundant epigenetic modification, its total content is only around 2%. Following in prevalence is 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-deoxycytidine (5hmdC), typically found at levels below 1%. Other modifications, such as 8oxodG and N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine, are significantly rarer, occurring at approximately 0.001% and 0.0001%, respectively [1].

Histones are basic proteins whose positive charges enable them to combine with DNA. Covalent post-translational modifications (additions or removal of functional groups) mainly occur on side chains of histone tails [9]. Certain modifications alter the charge density between histones and DNA, thereby affecting the organization of the chromatin, modifying its accessibility to the enzymes orchestrating gene transcription [3,10]. Thereby, gene expression is affected by histone modifications [3].

Detecting and quantifying chemical DNA modifications, especially epigenetic alterations, is crucial for disease screening and treatment. Thanks to its high sensitivity, analytical precision, and ability to characterize complex molecular changes, mass spectrometry has become a key tool in the study of epigenetic modifications.

Given the rapid expansion and methodological heterogeneity of MS approaches applied to epigenetics, a structured overview is needed to help researchers navigate analytical variability across sample preparation, instrumental platforms, and quantification strategies. By systematically mapping available workflows rather than evaluating biological outcomes, this review aims to provide a methodological frame of reference and identify areas where harmonization or further development is required.

We further narrow our scope to applications in human studies or in vitro models of human and animal origin.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted to map the existing research on the application of MS in the epigenetic field and to identify current knowledge gaps. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11] to ensure transparency and completeness in reporting. Although the protocol was not preregistered, it is available upon request from the corresponding author.

2.1. Search Strategy and Sources

A comprehensive bibliographic search was conducted using the three most popular electronic databases Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus, selecting the most relevant studies published between 2015 and 2025 without any linguistic restriction. We sought to identify articles focused on the identification and quantification of epigenetic modifications using MS approaches. To this end, the following initial research questions were posed by the authors:

- Which epigenetic modifications are most frequently studied using MS?

- Which MS instruments are most employed?

- Which studies apply MS in clinical contexts or in human biological models?

- Have any new approaches or improvements been developed in sample preparation and data analysis specific to the application of MS to epigenetics?

2.2. Search Terms

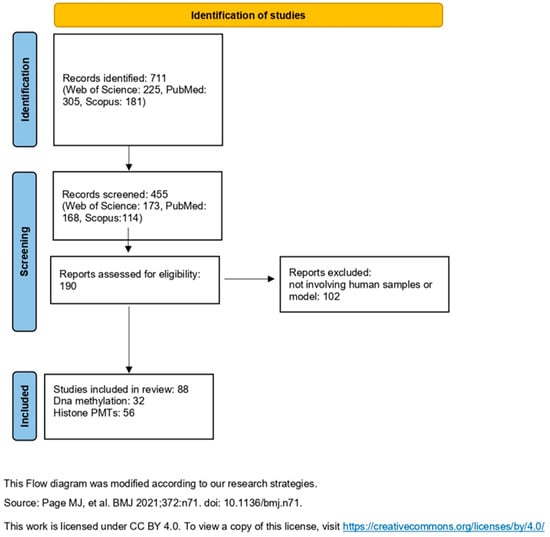

We focused our research solely on articles, by using the following strings in abstract title and keywords: “epigenetic modification” AND “quantification” AND “mass spectrometry”; “DNA methylation” AND “quantification” AND “mass spectrometry”; “histone modification” AND “quantification” AND “mass spectrometry”; “epigenetic modification” AND “mass spectrometry” and “treatment” AND “biological sample”; “DNA methylation” AND “mass spectrometry” and “treatment” AND “biological sample”, “histone modification” AND “mass spectrometry” and “treatment” AND “biological sample. Full-text articles were obtained online. Figure 1 illustrates the workflow adopted to identify, screen, and select studies in this review.

Figure 1.

Overview of the workflow. Adapted from Page, M.J. et al. [12], licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

3. Results

The search results retrieved a total of 711 articles, of which 225 studies from Web of Science, 305 from PubMed, and 181 from Scopus. The authors selected articles based on the abstract and reviews following the questions written in Section 2.1 identifying 173 articles through Web of Science, 168 through PubMed, and 114 through Scopus. After thorough de-duplication, a consolidated set of 190 unique articles was obtained. From this final collection, only 88 articles specifically focused on applications in human samples or human models.

Results were summarized as follows: epigenetic modifications identified by MS, analytical method used to study DNA methylation and histone post-translation modifications (PMTs).

3.1. Epigenetic Modifications Identified by Mass Spectrometry

DNA methylation is a biochemical process where a cytosine residue is enzymatically methylated with a methyl group (–CH3) at the five carbon position [13,14]. This process predominantly occurs at the CpG sites (dinucleotide cytosine-phospho-guanine), which are present at high frequency in regions known as CpG islands (CGI). These regions are usually found in gene promoters, where gene expression is regulated through methylation [15,16]. Approximately 4% of cytosines appear in CpG context, and 60–80% of CpG cytosines are methylated depending on the cell type and physiologic or pathologic state [17]. DNA methylation is coordinated by a family of enzymes named DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). It is a reversible chemical modification, and active demethylation processes are mediated by erasing DNA methylation mechanisms, mainly controlled by Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) enzymes [18]. TET have been shown to catalyze the conversion of 5 methyl cytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroximethyl cytosine (5hmC) as well as into 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [19]. DNA methylation has been shown to play an important role in the regulation of many essential biological processes, including retrotransposon silencing, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, regulation of gene expression, and maintenance of epigenetic memory [20].

Acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation are well-studied modifications that are known to significantly impact gene expression [3]. Aberrant histone acetylation and methylation in cancer alter the transcription of cytokines, chemokines, and transcription factors. This impacts the function and differentiation of T cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), key components of the tumor microenvironment (TME), leading to TME immunosuppression [21]. Numerous transcription factors, histone-modifying enzymes, and components of the transcriptional machinery interact with specific histone PTMs in a coordinated fashion, thereby influencing DNA function. Alterations in the regulation of histone variants and their post-translational modifications have been linked to several human diseases, including cancer. The number of PTMs that can be analyzed is several. Histones, H3 and H4 N-termini, in particular, are highly enriched in the number of possible modifications, both on the same residue and on neighboring residues [22].

Among the reviewed articles, 32 articles have been found to focus on DNA methylation, whereas 56 articles are focused on histone PMTs analyzed by MS.

3.2. DNA Methylation

Approximately 53% (17/32 studies) of the studies applied MS to human samples, including blood, plasma, urine, and tissues, while 40% focused on human cell lines. Among the remaining articles, one was focused on the analysis of both human samples and cell lines. The other was focused on a standard solution.

The most common instrument was the triple quadrupole (QqQ) mass spectrometer, employed in 69% (22/32) of the articles, including various QTRAP (Quadrupole Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry) systems and dedicated triple-Q mass spectrometers. Other detection methods, such as Q-TOF/TOF (Quadrupole–Time of Flight/Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry), Orbitrap, ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry), MALDI (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry) or DESI-TOF (Desorption Electrospray Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry) were utilized in the remaining 31% of the studies.

In terms of chromatographic separation, reversed-phase C18 columns are used in 25% of the employed methods, reflecting their robust retention and compatibility with nucleoside analysis. Other types of columns such as hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), mixed-mode or graphitised carbon columns and C8, were used less frequently. Mobile phase compositions are largely dominated by aqueous phases containing volatile buffers (e.g., 0.1% formic acid, ammonium acetate or ammonium formate), combined with organic phases such as methanol or acetonitrile.

Regarding sample pre-treatments, the majority of studies (19/32, 59%) adopt enzymatic hydrolysis of extracted DNA into nucleosides prior to MS analysis. These studies use multi-enzyme digestion protocols involving nuclease P1 (or S1 nuclease), phosphodiesterase and alkaline phosphatase. Five studies (16%) use acid hydrolysis with strong acids (e.g., formic acid or hydrochloric acid) at elevated temperatures, typically to shorten processing times, but with the potential risk of base degradation. Other studies apply alternative treatments, such as chemical derivatisation (e.g., benzoylation or dansylation) to improve chromatographic resolution or ionization efficiency, chemoenzymatic labeling of specific modifications (particularly 5hmC) or direct analysis of digested oligonucleotides rather than free nucleosides. These pre-analytical workflows directly influence the sensitivity, selectivity and susceptibility to artifacts of methylation analysis.

Quantification of methylated cytidine is essentially ever-present, 27/32 papers (84%) include 5mC or 5mdC among the monitored targets. Hydroxymethylcytosine is analyzed in approximately 20/32 studies (62%). Less frequently reported analytes include formylcytosine (5fC) (6/32 studies and carboxylcytosine (5caC) (6/32studies). Other modifications that are monitored include oxidized guanine bases (e.g., 8-oxodG), methylated purines (various N-methyl guanines) and rarer modifications such as N6-methyladenine. Collectively, these non-cytosine modifications appear in a minority of studies. Table 1 lists the results in order of publication year.

Table 1.

Analyte quantification, sample pre-treatment, validation parameters and instrument used in the reviewed papers.

3.3. Histone PMTs

Among the 56 articles, 75% used cell lines (42/56), 7 studies analyzed human samples (12%), 2 human primary-derived monocytes, one PMBS, and one in standard solution. Among all the considered studies, 25 relied on cancer/tumor (46%). In particular, 19 were cell lines, 4 were human clinical samples, and 2 included both. This highlights a strong prevalence of cell line–based models compared to patient-derived material. The most frequently used lines were HeLa (31%, 13/42).

The bottom-up approach was the dominant sample preparation strategy by far. Acid extraction was the preferred method for histone isolation, with sulfuric acid being the most used one (59%, 33/56). The TCA (trichloroacetic acid) precipitation step is often employed.

Chemical derivatisation was dominated by propionylation (53%, 30/56), with propionic anhydride being the most used chemical. Acetylation is used only in 9% of studies (5/56). On the other hand, trypsin is largely used for the digestion step (86%, 48/56). The final crucial step of desalting was predominantly performed using C18 StageTips to remove impurities that could interfere with MS analysis.

The gold standard for peptide separation was liquid chromatography (LC), with C18 reversed-phase columns dominating (77%, 43/56). Mobile phases typically consisted of a binary mixture of formic acid in water (solvent A) and formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B), a well-established system for compatibility with MS.

The MS platforms most frequently used were from the Orbitrap family (Q-Exactive/Fusion/Lumos; 66% 37/56), favored for their superior mass accuracy and high resolving power, followed by triple quadrupoles/QTRAP (16%, 9/36), TripleTOF/TOF (7%, 4/56). Imaging MS was used in 7% of the studies (4/56) with MALDI-TOF instruments.

The dominant data acquisition method was data-dependent acquisition (DDA) (52%, 29/56), a discovery-based approach that randomly selects the most abundant peptides for fragmentation. An increasing number of studies employed data-independent acquisition (DIA) or SWATH strategies (20% and 5%, respectively), which provide more comprehensive and reproducible peptide maps. Targeted multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) (18%, 10/56) and parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) (5%, 3/56) were used for focused quantification. Table 2 resumes the results in order of publication years.

Table 2.

Analyte quantification, sample pre-treatment, and instrument used in the reviewed papers.

4. Discussion

4.1. DNA Methylation

The collected data clearly show a community preference for targeted, quantitative LC–MS/MS on triple-quadrupole platforms for DNA methylation and nucleoside quantification. This choice reflects the need for high sensitivity and the routine use of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM/SRM) methods for quantifying low-abundance modified nucleosides in complex biological matrices.

However, the sample pre-treatment methods show significant variability, with enzymatic hydrolysis being the most frequently employed approach. Some studies adopt hybrid approaches, combining chemical and enzymatic steps to balance speed and fidelity, though optimization is critical to avoid inconsistent recoveries.

A key challenge that has been identified is the need for highly effective purification and pre-concentration steps. Several studies have mentioned the use of solid-phase extraction (SPE) or specific precipitation methods to address matrix effects and improve recovery. These patterns suggest that the field is moving towards two complementary strategies: enzymatic digestion and targeted LC–QqQ quantitation for robust quantification, and labeling/derivatisation or high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) approaches for extreme sensitivity or the broader discovery of low-abundance species. Chemical modifications are increasingly being used to improve the efficiency and sensitivity of ionization. Examples include labeling 5hmdC with beta-glucosyltransferase, derivatisation with 4-(dimethylamino)benzoic anhydride or chemical labeling for the targeted analysis of oxidized nucleosides. Although HR-MS offers powerful structural capabilities, it may exhibit a reduced dynamic range and often requires more complex data processing, ultimately limiting throughput. In parallel, some studies have explored MALDI-TOF [28,44] and LAMP-TOF [51] for site-specific methylation analysis, providing rapid screening options, albeit with lower sensitivity than LC-MS/MS.

An additional consideration emerges from the observed trends in chromatography and the mobile phase. Although the prevalence of C18 reversed-phase columns (around 74%) demonstrates their versatility in nucleoside analysis, they can struggle to retain highly polar analytes such as 5hmC or 5fC. This could justify the use of HILIC phases (approximately 19%) or graphitized carbon supports (approximately 7%) in targeted workflows.

Nevertheless, the review highlights several critical limitations. A major issue is theinconsistent reporting: while most studies provide some validation parameters, many fail to present a comprehensive validation set, including matrix effects, recovery across the analytical range, and stability assessments. The absence of such information complicates cross-study comparisons and undermines the feasibility of meaningful meta-analyses. This gap poses a significant challenge for the scientific community as it limits the ability to evaluate data quality and reproduce results across laboratories. Ultimately, it compromises the robustness and reliability of the findings.

Secondly, methodological choices inherently involve trade-offs. Enzymatic hydrolysis protocols are generally preferred due to their ability to reduce the risk of artefactual degradation. Indeed, enzymatic digestion is gentler and better preserves oxidized cytosine derivatives, improving accuracy for low-abundance modifications. The main drawback of enzymatic digestion is the increased complexity and duration of multi-step protocols, which may introduce variability if enzyme activity or incubation conditions are not rigorously controlled. In contrast, strong-acid hydrolysis is a simpler and faster approach, but the harsh conditions may introduce artificial base modifications. Rapid chemical hydrolysis is convenient, but it may introduce bias in the quantification of labile marks. It typically involves high-temperature, FA treatment and provides rapid and straightforward DNA cleavage, making it suitable for high-throughput applications. However, this approach can induce partial degradation of labile modifications, particularly 5hmC and 5fC, which could lead to an underestimation of these marks.

The impact of matrix effects is a recurring issue, as highlighted in several articles which emphasize the need for specific purification and pre-concentration steps, such as SPE. Endogenous compounds present in complex biological matrices (e.g., serum, urine or tissue lysates) can interfere with the MS signal, resulting in inaccurate quantification. While some studies address this with specific protocols, there is no consistent, robust approach yet to mitigate these effects. Pre-analytical heterogeneity (e.g., different DNA extraction kits, inconsistent use of internal standards (IS), and varied cleanup procedures) introduces potential biases: reported recoveries span a wide range, and not all studies correct for recovery or matrix suppression using isotopically labeled IS. The lack of a single, universally adopted protocol contributes to variability between methods. The diversity of sample preparation methods, combined with the lack of comprehensive validation reporting, highlights the urgent need to develop and adopt harmonized protocols to ensure the quality, comparability, and reliability of DNA methylation data in research and clinical settings. Moreover, studies frequently prioritize technical precision over addressing potential pre-analytical sources of error, such as DNA degradation during storage or extraction. This can have a disproportionate impact on oxidized derivatives. Furthermore, while triple-quadrupole MS remains the gold standard for targeted quantification, the relatively limited application of HR-MS contrasts with its widespread use. HR-MS would allow for the more confident identification of unexpected or novel nucleoside modifications and better resolution of isobaric interferences. Meanwhile, MALDI-and TOF-based approaches, although adopted by only a minority of studies, offer certain advantages, such as higher throughput and positional information (e.g., EpiTyper MALDI assays). However, these methods generally have lower quantitative sensitivity than QqQ platforms. MALDI-TOF in particular suffers from a restricted dynamic range and limited accuracy in measuring methylation levels, despite its promise.

Finally, many reports have limited sample sizes and clinical validation (small cohorts and single-center measurements).

However, to advance clinical translation and enable reliable cross-study synthesis, future work should emphasize full method validation (including matrix effect assessment and stability), wider adoption of isotopically labeled standards, and coordinated inter-laboratory standardization, while preserving the complementary role of high-resolution and derivatisation-based methods for discovery and applications requiring extreme sensitivity. This convergence would ultimately improve the reproducibility of methylation biomarker studies and accelerate the transition from analytical development to clinically actionable assays.

4.2. Histone PMTs

A critical evaluation of these findings shows that, despite being well-established, the field of histone proteomics faces significant challenges that prevent it from reaching its full potential. The data show a strong trend towards in vitro cell line models (48 articles), with only a small proportion of studies (8 articles) utilizing direct human samples. This methodological preference has important implications for the applicability of research findings. While these models offer advantages such as reproducibility and experimental control, their altered and simplified biology may not accurately reflect the complex PTM dynamics observed in living human organisms or tissues. The limited use of human samples, predominantly blood-derived cells, highlights the logistical challenges of obtaining and processing more complex clinical specimens. The discrepancy between in vitro and clinical models remains a critical bottleneck in the field.

While technically sound, the heavy reliance on the bottom-up approach is a major impediment to deciphering the histone code. Although this method simplifies the analytical process by breaking down histones into smaller peptides, it has a significant and frequently overlooked drawback: it destroys information about PTM combinatorial patterns on a single histone molecule. The loss of this ‘PTM crosstalk’ is a fundamental limitation that prevents a complete understanding of the complex biological code encoded by multiple PTMs on a single histone molecule. Identifying individual modifications is not enough; the biological meaning resides in their specific combinations. The fact that only a handful of studies have explored middle-down or top-down proteomics highlights a methodological gap that the field must address to gain a more comprehensive understanding of histone PTM dynamics.

Concerning the sample pre-treatment, the subsequent core procedure is proteolytic digestion, primarily performed using trypsin to achieve robust peptide coverage for bottom-up analyses. However, trypsin can cleave after methylated or acetylated lysines, which makes identifying PTM sites challenging. To address this issue, many protocols incorporate propionylation (either before or after digestion) to seal off the free N-termini of lysine and prevent non-specific enzymatic cleavage. This makes it easier to localize the marks of methylation and acetylation with confidence. However, the strong reliance on propionylation improves chromatographic behavior and tryptic specificity; incomplete propionylation, variability in derivatisation efficiency between samples, and side reactions on certain acyl marks can distort stoichiometry. Alternative approaches, such as acylation using acetic or deuterated acetic anhydride, and alkylation using dithiothreitol or iodoacetamide, offer partial solutions, but they can introduce artifacts or fail to capture transient modifications. Furthermore, enzymes such as GluC are used in middle-down approaches to produce longer peptides, which are beneficial for analyzing PTMs that are far apart on the histone tail. This preserves combinatorial information that is often lost in bottom-up methods.

Rigorous inclusion of internal heavy standards is still not systematic. On the other hand, although acid extraction is fast and efficient, it risks disturbing labile PTMs (e.g., some acylations and phospho-marks), and when combined with extensive TCA precipitation, it can result in losses or introducing matrix components that complicate ionization.

The most prevalent bottom-up approaches afford high site-specific resolution, but obscure combinatorial PTM patterns. Conversely, middle-down and top-down analyses preserve such patterns, but require greater sample input, complex workflows, and advanced instrumentation, which limits their routine adoption.

In the field of MS, targeted methods such as MRM and PRM improve quantitative reliability but limit global discovery. In contrast, DDA and DIA approaches enable broader mapping but sacrifice sensitivity to low-abundance marks. Orbitrap-centric DDA offers high mass accuracy and extensive coverage, but is affected by stochastic precursor sampling and co-isolation interference. DIA/SWATH is used for a significant proportion of applications, yet remains underutilized despite its advantages in reproducible quantification. This is probably due to the limited availability of histone-tail-specific spectral libraries and turnkey scoring workflows. The shift from DDA to DIA is particularly encouraging. DIA enables comprehensive, systematic, and quantitative analysis by acquiring all fragment ion spectra, thus overcoming the stochasticity of DDA and providing a more complete dataset. Developing advanced software and bioinformatic pipelines is also crucial for interpreting the immense complexity of the data generated by these high-throughput techniques.

Overall, these statistics demonstrate the ongoing challenge of balancing methodological compromises. High-throughput and sensitive quantification often come at the expense of combinatorial context and reproducibility. Conversely, approaches that capture PTM complexity tend to be less scalable and more demanding in terms of instrumentation. However, the technological landscape offers some promising solutions. Adopting new-generation instruments such as modern Orbitrap and Q-TOF instrumentation represents a significant advance. These hybrid instruments combine the speed of a linear ion trap with the high resolution of an Orbitrap, enabling faster and more precise analysis. Overall, the weak link is reproducibility: extraction protocols, derivatisation efficiency, choice of acquisition mode, and variable clean-up steps all create avoidable variance between studies.

Looking to the future, several areas are essential for the field to progress. Firstly, there is an urgent need for standardized protocols to ensure inter-laboratory reproducibility and facilitate data sharing. The development of community reference materials and internal standards is crucial for benchmarking acid versus extraction, codifying propionylation protocols (including checks for over-derivatisation), and reporting QC metrics such as digestion efficiency.

Secondly, research should focus on developing and implementing methodologies that preserve PTM combinatorial information, such as combined top-down/middle-down approaches. DIA should be adopted more broadly alongside openly shared, histone-focused libraries, and DIA/PRM should be paired with rigorous interference evaluation. Finally, software pipelines should be consolidated (with open formats, versioned parameters, unit-tested quantification and ready-to-reuse Skyline/EpiProfile-style templates).

4.3. General Observations Across MS-Based Epigenetic Workflows

In addition to the heterogeneity observed across analytical workflows, several studies highlight the importance of addressing the stability of epigenetic marks during sample preparation and storage. A subset of the reviewed articles includes oxidized nucleobases such as 8-oxo-dG, 5-formyl-dC or 5-carboxyl-dC among their analytical targets, underscoring their relevance not only as markers of oxidative stress but also as potential artifacts introduced during DNA extraction, storage, and hydrolysis (e.g., references [25,38,47] in our review). This aspect has also been highlighted in the broader literature, where several authors note that improper sample handling can lead to spontaneous oxidation of guanine-or cytosine-derived species. For example, substantial discrepancies in reported endogenous levels of cellular 8-oxodG are largely attributed to artefactual oxidation of dG occurring during DNA isolation and processing [110]. Future methodological developments should therefore prioritize standardized protocols aimed at minimizing artefactual oxidation, including: (i) the systematic use of antioxidants (e.g desferrioxamine (DFAM) or butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) [111]) during extraction; (ii) controlled-temperature workflows for hydrolysis and enzymatic digestion [112]; (iii) immediate stabilization and aliquoting to reduce freeze–thaw cycles [112]; and (iv) validated storage conditions for long-term biobanking. Harmonizing such practices across laboratories would significantly improve reproducibility, especially in studies quantifying low-abundance modified nucleosides. Integrating these stabilization strategies into MS-based epigenetic pipelines represents a key future direction for the field.

Although the primary focus of this scoping review is the analytical variability of MS-based approaches for epigenetic analysis, it is worth noting that several articles in the broader literature highlight additional practical aspects influencing the adoption of these methodologies. In particular, some authors underline that access to MS platforms, especially in laboratories without established analytical facilities, and the need for operators with specific training in sample processing and data interpretation may represent relevant barriers to widespread implementation [113,114,115,116,117].

5. Conclusions

Overall, while the field benefits from advanced MS technologies and diverse analytical targets, future work should prioritize methodological standardization, comprehensive validation reporting, and integrated multi-omics approaches to enhance biological insight and clinical translational potential.

The ultimate challenge will be to integrate histone proteomics and DNA methylation data with other ‘omics’ platforms (e.g., transcriptomics and genomics) to reveal the entire network of epigenetic regulation. Histone PTM and DNA methylation research will only evolve from a characterisation tool to a means of understanding the molecular mechanisms of health and disease by combining robust methods, state-of-the-art instrumentation, and sophisticated bioinformatics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C., F.S.V. and E.P.; methodology, R.C., A.M., A.P.L.M., F.B. and C.Z.; validation, R.C. and E.P.; investigation, R.C. and A.M.; resources, R.C. and A.M.; data curation, R.C. and E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., A.M., A.P.L.M. and E.P.; writing—review and editing, R.C., E.P., F.B., C.Z., E.N. and F.S.V.; supervision, E.P., E.N. and F.S.V.; project administration F.B., C.Z., E.P., E.N. and F.S.V.; funding acquisition, F.S.V. and E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Health—National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 6 Component 2—Investment 2.1 “Enhancement and strengthening of biomedical research of the National Health Service”, financed by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—1st Public Call—Project “Night-shift work and breast cancer”—PNRR-MAD-2022-12376823—CUP F33C22001130001.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMTs | post-translation modifications |

| Cyt | Cytidine |

| 5mC | 5-Methylcytosine |

| 5hmC | 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine |

| 5caC | 5-Carboxylcytosine |

| 5fC | 5-Formylcytosine |

| dC | Deoxycytidine |

| 5mdC | 5-Methyldeoxycytidine |

| 5hmdC | 5-Hydroxymethyldeoxycytidine |

| 4mdC | N4-Methyldeoxycytidine |

| 5cadC | 5-Carboxyldeoxycytidine |

| 5fdC | 5-Formyldeoxycytidine |

| 5-Aza-dC | 5-Azadeoxycytidine |

| 2o-mdC | 2′-Oxymethylcytidine |

| dG | 2′-Deoxyguanosine |

| 5-fodC | 5-Formyl-2′-deoxycytidine |

| 5forC | 5-Formylcytidine |

| 5-fodU | 5-Formyl-2′-deoxyuridine |

| 5-forU | 5-Formyluridine |

| 5forCm | 2′-O-methyl-5-formylcytidine |

| 5-forUm | 2′-O-methyl-5-formyluridine |

| 5hmdU | 5-Hydroxymethyldeoxyuridine |

| dA | 2′-Deoxyadenosine |

| dT | Thymidine |

| N3-5gmdC | 6-Azide-β-glucosyl-5-hydroxymethylcytidine |

| O6-Me-dG | O6-Methyl-2′-deoxyguanosine |

| O6-CM-dG | O6-Carboxymethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine |

| N6-CM-dA | N6-Carboxymethyl-2′-deoxyadenosine |

| εdA | N6-Vinyl-2′-deoxyadenosine |

| N2-Et-dG | N2-Ethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine |

| 5-Cl-dC | 5-Chloro-2′-deoxycytidine |

| Guo | Guanosine |

| Ado | Adenosine |

| Urd | Uridine |

| 5-methyluridine | 5-Methyluridine |

| dU | 2′-Deoxyuridine |

| m6dA | N6-Methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine |

| 3MeA | N3-Methyladenine |

| 7MeG | N7-Methylguanine |

| 6MeG | O6-Methylguanine |

| 1MeG | 1-Methylguanine |

| 9MeG | 9-Methylguanine |

| 2EtdG | 2-Ethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine |

| 1MeA | 1-Methyladenine |

| 9MeA | 9-Methyladenine |

| MeA | 3-Methyladenine (come da tua lista) |

| 9EtA | 9-Ethyladenine |

| 9EtG | 9-Ethylguanine |

| Ino | Inosine |

| 5-methyl-CMP | 5-Methylcytidylic acid |

| FA | Formic Acid |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LLOD | Lower Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| LLOQ | Lower Limit of Quantification |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography |

| QqQ | Triple Quadrupole |

| Q | Quadrupole |

| TOF | Time-of-Flight |

| ICP | Inductively Coupled Plasma |

| MALDI | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization |

| DESI | Desorption Electrospray Ionization |

| CE | Capillary Electrophoresis |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography |

| LAMP | Linear Amplification |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| CRC | Colon Rectal Cancer |

| Affi-BAMS | Affinity-bead Assisted Mass Spectrometry |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SPE | Solid Phase Extraction |

| DI | Direct Infusion |

| DDA | Data-Dependent Acquisition |

| DIA | Data-Independent Acquisition |

| SIM | Selected Ion Monitoring |

| PRM | Parallel Reaction Monitoring |

| MRM | Multiple Reaction Monitoring |

| SWATH | Sequential Window Acquisition of all Theoretical Fragmention Spectra |

References

- Chen, S.; Lai, W.; Wang, H. Recent Advances in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry Techniques for Analysis of DNA Damage and Epigenetic Modifications. Mutat. Res.—Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2024, 896, 503755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, A.; Freeman, W.M.; Jackson, J.; Wren, J.D.; Porter, H.; Richardson, A. The Role of DNA Methylation in Epigenetics of Aging. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 195, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadida, H.Q.; Abdulla, A.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Hashem, S.; Macha, M.A.; Akil, A.S.A.-S.; Bhat, A.A. Epigenetic Modifications: Key Players in Cancer Heterogeneity and Drug Resistance. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 39, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papait, R.; Serio, S.; Condorelli, G. Role of the Epigenome in Heart Failure. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 1753–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiliani, M.; Koh, K.P.; Shen, Y.; Pastor, W.A.; Bandukwala, H.; Brudno, Y.; Agarwal, S.; Iyer, L.M.; Liu, D.R.; Aravind, L.; et al. Conversion of 5-Methylcytosine to 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in Mammalian DNA by MLL Partner TET1. Science 2009, 324, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, M.J.; Palanca-Ballester, C.; Urtasun, R.; Alemany-Cosme, E.; Lahoz, A.; Sandoval, J. Methods for Analysis of Specific DNA Methylation Status. Methods 2021, 187, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traube, F.R.; Schiffers, S.; Iwan, K.; Kellner, S.; Spada, F.; Müller, M.; Carell, T. Isotope-Dilution Mass Spectrometry for Exact Quantification of Noncanonical DNA Nucleosides. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 283–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA Damage: Mechanisms, Mutation, and Disease. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, K.; Mäder, A.W.; Richmond, R.K.; Sargent, D.F.; Richmond, T.J. Crystal Structure of the Nucleosome Core Particle at 2.8 Å Resolution. Nature 1997, 389, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, J.E.; Campbell, R.M. Histone Modifications and Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a019521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, J.C.; Aquila, G.; Oton-Gonzalez, L.; Selvatici, R.; Rizzo, P.; De Mattei, M.; Pavasini, R.; Tognon, M.; Campo, G.C.; Martini, F. Methylation of SERPINA1 Gene Promoter May Predict Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Patients Affected by Acute Coronary Syndrome. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, J.C.; Oton-Gonzalez, L.; Selvatici, R.; Rizzo, P.; Pavasini, R.; Campo, G.C.; Lanzillotti, C.; Mazziotta, C.; De Mattei, M.; Tognon, M.; et al. SERPINA1 Gene Promoter Is Differentially Methylated in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Pregnant Women. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 550543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.V.C.; Bourc’his, D. The Diverse Roles of DNA Methylation in Mammalian Development and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, B.D. A Practical Guide to the Measurement and Analysis of DNA Methylation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, J.C.; Lanzillotti, C.; Mazziotta, C.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F. Epigenetics of Male Infertility: The Role of DNA Methylation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 689624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schübeler, D. Function and Information Content of DNA Methylation. Nature 2015, 517, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. Mechanisms and Functions of Tet Protein-Mediated 5-Methylcytosine Oxidation. Genes. Dev. 2011, 25, 2436–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieda, M.; Matsuura, N.; Kimura, H. Histone Modifications Associated with Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion. In Cancer Epigenetics; Verma, M., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1238, pp. 301–317. ISBN 978-1-4939-1803-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Garcia, B.A. Examining Histone Posttranslational Modification Patterns by High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 512, pp. 3–28. ISBN 978-0-12-391940-3. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, T.; Espina, M.; Montes-Bayón, M.; Sierra, L.; Blanco-González, E. Anion Exchange Chromatography for the Determination of 5-Methyl-2′-Deoxycytidine: Application to Cisplatin-Sensitive and Cisplatin-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjobert, C.; El Maï, M.; Gérard-Hirne, T.; Guianvarc’h, D.; Carrier, A.; Pottier, C.; Arimondo, P.B.; Riond, J. Combined Analysis of DNA Methylation and Cell Cycle in Cancer Cells. Epigenetics 2015, 10, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Mo, J.; Lu, M.; Wang, H. Detection of Human Urinary 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine by Stable Isotope Dilution HPLC-MS/MS Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 1846–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Jiang, H.-P.; Peng, C.-Y.; Deng, Q.-Y.; Lan, M.-D.; Zeng, H.; Zheng, F.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Yuan, B.-F. DNA Hydroxymethylation Age of Human Blood Determined by Capillary Hydrophilic-Interaction Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Clin. Epigenetics 2015, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X. DNA Methylation as a Potential Diagnosis Indicator for Rapid Discrimination of Rare Cancer Cells and Normal Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaes, G.; Ronneberg, J.; Kristensen, V.; Tost, J. Heterogeneous DNA Methylation Patterns in the GSTP1 Promoter Lead to Discordant Results between Assay Technologies and Impede Its Implementation as Epigenetic Biomarkers in Breast Cancer. Genes 2015, 6, 878–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Zhang, X.; Nie, J.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X. Ultrasensitive Determination of 5-Methylcytosine and 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in Genomic DNA by Sheathless Interfaced Capillary Electrophoresis-Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 2698–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Du, W.; Yin, D.; Lyu, N.; Zhao, G.; Guo, C.; Tang, D. Accurate Quantification of 5-Methylcytosine, 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-Formylcytosine, and 5-Carboxylcytosine in Genomic DNA from Breast Cancer by Chemical Derivatization Coupled with Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 91248–91257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, T.; Guo, N.; Yu, L.; Yuan, B.; Feng, Y. Determination of Formylated DNA and RNA by Chemical Labeling Combined with Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 981, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahal, T.; Koren, O.; Shefer, G.; Stern, N.; Ebenstein, Y. Hypersensitive Quantification of Global 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine by Chemoenzymatic Tagging. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1038, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vető, B.; Szabó, P.; Bacquet, C.; Apró, A.; Hathy, E.; Kiss, J.; Réthelyi, J.M.; Szeri, F.; Szüts, D.; Arányi, T. Inhibition ofDNAMethyltransferase Leads to Increased Genomic 5-hydroxymethylcytosine Levels in Hematopoietic Cells. FEBS Open Bio 2018, 8, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, N.; Wang, H. Multienzyme Cascade Bioreactor for a 10 Min Digestion of Genomic DNA into Single Nucleosides and Quantitative Detection of Structural DNA Modifications in Cellular Genomic DNA. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 21883–21890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Xie, C.; Chen, Q.; Cao, X.; Guo, M.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Y. A Novel Malic Acid-Enhanced Method for the Analysis of 5-Methyl-2′-Deoxycytidine, 5-Hydroxymethyl-2′-Deoxycytidine, 5-Methylcytidine and 5-Hydroxymethylcytidine in Human Urine Using Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1034, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosendaal, J.; Rosing, H.; Lucas, L.; Oganesian, A.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H. Development, Validation, and Clinical Application of a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay for the Quantification of Total Intracellular β-Decitabine Nucleotides and Genomic DNA Incorporated β-Decitabine and 5-Methyl-2′-Deoxycytidine. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 164, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Wakui, M.; Hayashida, T.; Nishime, C.; Murata, M. Intensive Optimization and Evaluation of Global DNA Methylation Quantification Using LC-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 7221–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J. Simultaneous Quantitation of 14 DNA Alkylation Adducts in Human Liver and Kidney Cells by UHPLC-MS/MS: Application to Profiling DNA Adducts of Genotoxic Reagents. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 166, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Liu, D.; Sha, Q.; Geng, H.; Liang, J.; Tang, D. Succinic Acid Enhanced Quantitative Determination of Blood Modified Nucleosides in the Development of Diabetic Nephropathy Based on Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 164, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.-X.; Song, C.-X. 5-Carboxylcytosine Is Resistant towards Phosphodiesterase I Digestion: Implications for Epigenetic Modification Quantification by Mass Spectrometry. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 29010–29014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, B.; Németh, K.; Mészáros, K.; Szücs, N.; Czirják, S.; Reiniger, L.; Rajnai, H.; Krencz, I.; Karászi, K.; Krokker, L.; et al. Demethylation Status of Somatic DNA Extracted From Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors Indicates Proliferative Behavior. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, dgaa156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.-X. 5hmC-MIQuant: Ultrasensitive Quantitative Detection of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in Low-Input Cell-Free DNA Samples. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, K.; Mészáros, K.; Szabó, B.; Butz, H.; Arányi, T.; Szabó, P. A Relative Quantitation Method for Measuring DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation Using Guanine as an Internal Standard. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 4614–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Lei, S.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Yin, Q.; Xu, T.; Zhou, W.; Li, H.; Gu, W.; Ma, F.; et al. RPTOR Methylation in the Peripheral Blood and Breast Cancer in the Chinese Population. Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal-Bekar, N.E.; Siomek-Gorecka, A.; Gackowski, D.; Köken-Avşar, A.; Yarkan-Tuğsal, H.; Birlik, M.; İşlekel, H. Global Hypomethylation Pattern in Systemic Sclerosis: An Application for Absolute Quantification of Epigenetic DNA Modification Products by 2D-UPLC-MS/MS. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 239, 108997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Hu, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, R.; Lv, Y. HOGG1-Assisted DNA Methylation Analysis via a Sensitive Lanthanide Labelling Strategy. Talanta 2022, 239, 123136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Gong, Y.; Guo, L.; Xie, J. In Vitro Evaluation of DNA Damage Effect Markers toward Five Nitrogen Mustards Based on Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, H. Highly Efficient Gel Electrophoresis for Accurate Quantification of Nucleic Acid Modifications via In-Gel Digestion with UHPLC-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 13407–13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresnais, M.; Jung, I.; Klein, U.B.; Miller, A.K.; Turcan, S.; Haefeli, W.E.; Burhenne, J.; Longuespée, R. Important Requirements for Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometric Measurements of Temozolomide-Induced 2′-Deoxyguanosine Methylations in DNA. Cancers 2023, 15, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Hong, X.; Yuan, Z.; Mu, J.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, S.; Guo, C. Pan-Cancer Analysis of DNA Epigenetic Modifications by Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Yang, X.; He, W.; Luo, Z.; Li, W.; Xu, C.; Cui, X.; Zhang, W.; Wei, N.; Wang, X.; et al. LAMP-MS for Locus-Specific Visual Quantification of DNA 5 mC and RNA m6A Using Ultra-Low Input. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202413872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Kumar, A.; Liu, Y.-M.; Odubanjo, O.V.; Noubissi, F.K.; Hu, Y.; Hu, H. Ultraperformance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay of DNA Cytosine Methylation Excretion from Biological Systems. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 13370–13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandoolaeghe, Q.; Bouchart, V.; Guérin, Y.; Lagadu, S.; Lopez-Piffet, C.; Delépée, R. Comparison of PGC and Biphenyl Stationary Phases for the High Throughput Analysis of DNA Epigenetic Modifications by UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1250, 124382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, S.; Furuya, K.; Ikura, M.; Matsuda, T.; Ikura, T. Absolute Quantification of Acetylation and Phosphorylation of the Histone Variant H2AX upon Ionizing Radiation Reveals Distinct Cellular Responses in Two Cancer Cell Lines. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2015, 54, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulej, K.; Avgousti, D.; Weitzman, M.; Garcia, B. Characterization of Histone Post-Translational Modifications during Virus Infection Using Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics. Methods 2015, 90, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, P. Crosstalk of Homocysteinylation, Methylation and Acetylation on Histone H3. Analyst 2015, 140, 3057–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.-F.; Lin, S.; Molden, R.C.; Cao, X.-J.; Bhanu, N.V.; Wang, X.; Sidoli, S.; Liu, S.; Garcia, B.A. Epiprofile Quantifies Histone Peptides with Modifications by Extracting Retention Time and Intensity in High-Resolution Mass Spectra. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2015, 14, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.W.; Turko, I.V. Histone Post-Translational Modifications in Frontal Cortex from Human Donors with Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin. Proteom. 2015, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maile, T.M.; Izrael-Tomasevic, A.; Cheung, T.; Guler, G.D.; Tindell, C.; Masselot, A.; Liang, J.; Zhao, F.; Trojer, P.; Classon, M.; et al. Mass Spectrometric Quantification of Histone Post-Translational Modifications by a Hybrid Chemical Labeling Method. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2015, 14, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, R.C.; Bhanu, N.V.; LeRoy, G.; Arnaudo, A.M.; Garcia, B.A. Multi-Faceted Quantitative Proteomics Analysis of Histone H2B Isoforms and Their Modifications. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Harshman, S.W.; Ruppert, A.S.; Mortazavi, A.; Lucas, D.M.; Thomas-Ahner, J.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Byrd, J.C.; Freitas, M.A.; Parthun, M.R. Proteomic Profiling Identifies Specific Histone Species Associated with Leukemic and Cancer Cells. Clin. Proteom. 2015, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowers, J.L.; Mirfattah, B.; Xu, P.; Tang, H.; Park, I.Y.; Walker, C.; Wu, P.; Laezza, F.; Sowers, L.C.; Zhang, K. Quantification of Histone Modifications by Parallel-Reaction Monitoring: A Method Validation. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 10006–10014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krautkramer, K.A.; Reiter, L.; Denu, J.M.; Dowell, J.A. Quantification of SAHA-Dependent Changes in Histone Modifications Using Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3252–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, S.; Lin, S.; Xiong, L.; Bhanu, N.V.; Karch, K.R.; Johansen, E.; Hunter, C.; Mollah, S.; Garcia, B.A. Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH) Analysis for Characterization and Quantification of Histone Post-Translational Modifications. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2015, 14, 2420–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhang, K.; Tian, S.; Fan, E.; Chen, L.; He, X.; Zhang, Y. Quantitative Characterization of Histone Post-Translational Modifications Using a Stable Isotope Dimethyl-Labeling Strategy. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 3779–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Quantitative Analysis of the Sirt5-Regulated Lysine Succinylation Proteome in Mammalian Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1410, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minshull, T.C.; Cole, J.; Dockrell, D.H.; Read, R.C.; Dickman, M.J. Analysis of Histone Post Translational Modifications in Primary Monocyte Derived Macrophages Using Reverse Phase×reverse Phase Chromatography in Conjunction with Porous Graphitic Carbon Stationary Phase. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1453, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, S.; Bhanu, N.V.; Karch, K.R.; Wang, X.; Garcia, B.A. Complete Workflow for Analysis of Histone Post-Translational Modifications Using Bottom-up Mass Spectrometry: From Histone Extraction to Data Analysis. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 111, e54112. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, F.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Compositional Analysis of Asymmetric and Symmetric Dimethylated H3R2 Using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry-Based Targeted Proteomics. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 8441–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Chai, Y.-R.; Jia, Y.-L.; Gao, J.-H.; Peng, X.-J.; Han, H.-F. Crosstalk among the Proteome, Lysine Phosphorylation, and Acetylation in Romidepsin-Treated Colon Cancer Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 53471–53501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govaert, E.; Van Steendam, K.; Scheerlinck, E.; Vossaert, L.; Meert, P.; Stella, M.; Willems, S.; De Clerck, L.; Dhaenens, M.; Deforce, D. Extracting Histones for the Specific Purpose of Label-Free MS. Proteomics 2016, 16, 2937–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitko, D.; Majek, P.; Schirghuber, E.; Kubicek, S.; Bennett, K. FASIL-MS: An Integrated Proteomic and Bioinformatic Workflow To Universally Quantitate In Vivo-Acetylated Positional Isomers. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 2579–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ren, J.; Jia, X.; Levy, T.; Rikova, K.; Yang, V.; Lee, K.; Stokes, M.; Silva, J. Quantitative Profiling of Post-Translational Modifications by Immunoaffinity Enrichment and LC-MS/MS in Cancer Serum without Immunodepletion. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2016, 15, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noberini, R.; Uggetti, A.; Pruneri, G.; Minucci, S.; Bonaldi, T. Pathology Tissue-Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Analysis to Profile Histone Post-Translational Modification Patterns in Patient Samples. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2016, 15, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, S.; Fujiwara, R.; Garcia, B.A. Multiplexed Data Independent Acquisition (MSX-DIA) Applied by High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Improves Quantification Quality for the Analysis of Histone Peptides. Proteomics 2016, 16, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.; Khade, B.; Pandya, R.; Gupta, S. A Novel Method for Isolation of Histones from Serum and Its Implications in Therapeutics and Prognosis of Solid Tumours. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoli, S.; Lu, C.; Coradin, M.; Wang, X.; Karch, K.R.; Ruminowicz, C.; Garcia, B.A. Metabolic Labeling in Middle-down Proteomics Allows for Investigation of the Dynamics of the Histone Code. Epigenetics Chromatin 2017, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feist, P.E.; Sidoli, S.; Liu, X.; Schroll, M.M.; Rahmy, S.; Fujiwara, R.; Garcia, B.A.; Hummon, A.B. Multicellular Tumor Spheroids Combined with Mass Spectrometric Histone Analysis To Evaluate Epigenetic Drugs. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2773–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méhul, B.; Perrin, A.; Grisendi, K.; Galindo, A.N.; Dayon, L.; Ménigot, C.; Rival, Y.; Voegel, J.J. Mass Spectrometry and DigiWest Technology Emphasize Protein Acetylation Profile from Quisinostat-Treated HuT78 CTCL Cell Line. J. Proteom. 2018, 187, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Sidoli, S.; Garcia, B.A.; Zhao, X. Assessment of Quantification Precision of Histone Post-Translational Modifications by Using an Ion Trap and down to 50000 Cells as Starting Material. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.-F.; Sidoli, S.; Marchione, D.M.; Simithy, J.; Janssen, K.A.; Szurgot, M.R.; Garcia, B.A. EpiProfile 2.0: A Computational Platform for Processing Epi-Proteomics Mass Spectrometry Data. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 2533–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.M.; Sidoli, S.; Coradin, M.; Schack Jespersen, M.; Schwämmle, V.; Jensen, O.N.; Garcia, B.A.; Brodbelt, J.S. Extensive Characterization of Heavily Modified Histone Tails by 193 Nm Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry via a Middle-Down Strategy. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 10425–10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Kavarthapu, R.; Anbazhagan, R.; Liao, M.; Dufau, M.L. Interaction of Positive Coactivator 4 with Histone 3.3 Protein Is Essential for Transcriptional Activation of the Luteinizing Hormone Receptor Gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2018, 1861, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clerck, L.; Willems, S.; Noberini, R.; Restellini, C.; Van Puyvelde, B.; Daled, S.; Bonaldi, T.; Deforce, D.; Dhaenens, M. hSWATH: Unlocking SWATH’s Full Potential for an Untargeted Histone Perspective. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 3840–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidoli, S.; Kori, Y.; Lopes, M.; Yuan, Z.-F.; Kim, H.J.; Kulej, K.; Janssen, K.A.; Agosto, L.M.; da Cunha, J.P.C.; Andrews, A.J.; et al. One Minute Analysis of 200 Histone Posttranslational Modifications by Direct Injection Mass Spectrometry. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, K.; Coradin, M.; Lu, C.; Sidoli, S.; Garcia, B. Quantitation of Single and Combinatorial Histone Modifications by Integrated Chromatography of Bottom-up Peptides and Middle-down Polypeptide Tails. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 30, 2449–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanu, N.V.; Sidoli, S.; Garcia, B.A. A Workflow for Ultra-Rapid Analysis of Histone Post-Translational Modifications with Direct-Injection Mass Spectrometry. Bio Protoc. 2020, 10, e3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, G.M.; Bergo, V.B.; Mamaev, S.; Wojchowski, D.M.; Toran, P.; Worsfold, C.R.; Castaldi, M.P.; Silva, J.C. Affinity-bead Assisted Mass Spectrometry (Affi-BAMS): A Multiplexed Microarray Platform for Targeted Proteomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; De Clerck, L.; Willems, S.; Van Puyvelde, B.; Daled, S.; Deforce, D.; Dhaenens, M. Comprehensive Histone Epigenetics: A Mass Spectrometry Based Screening Assay to Measure Epigenetic Toxicity. MethodsX 2020, 7, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, E.M.; Solis-Mezarino, V.; Kuhm, C.; Northoff, B.H.; Karin, I.; Klopstock, T.; Holdt, L.M.; Völker-Albert, M.; Imhof, A.; Peleg, S. Determining Histone H4 Acetylation Patterns in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Using Mass Spectrometry. Clin. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 15, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Yao, J.; Jin, H.; Yang, P. Outer Membrane Protease OmpT-Based Strategy for Simplified Analysis of Histone Post-Translational Modifications by Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Simultaneous Detection of Site-Specific Histone Methylations and Acetylation Assisted by Single Template Oriented Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Analyst 2020, 145, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abshiru, N.A.; Sikora, J.W.; Camarillo, J.M.; Morris, J.A.; Compton, P.D.; Lee, T.; Neelamraju, Y.; Haddox, S.; Sheridan, C.; Carroll, M.; et al. Targeted Detection and Quantitation of Histone Modifications from 1,000 Cells. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappacosta, F.; Wagner, C.; Della Pietra, A.; Gerhart, S.; Keenan, K.; Korenchuck, S.; Quinn, C.; Barbash, O.; McCabe, M.; Annan, R. A Chemical Acetylation-Based Mass Spectrometry Platform for Histone Methylation Profiling. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021, 20, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noberini, R.; Savoia, E.O.; Brandini, S.; Greco, F.; Marra, F.; Bertalot, G.; Pruneri, G.; McDonnell, L.A.; Bonaldi, T. Spatial Epi-Proteomics Enabled by Histone Post-Translational Modification Analysis from Low-Abundance Clinical Samples. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchaříková, H.; Dobrovolná, P.; Lochmanová, G.; Zdráhal, Z. Trimethylacetic Anhydride-Based Derivatization Facilitates Quantification of Histone Marks at the MS1 Level. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2021, 20, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph-Chowdhury, J.-S.N.; Stransky, S.; Graff, S.; Cutler, R.; Young, D.; Kim, J.S.; Madrid-Aliste, C.; Aguilan, J.T.; Nieves, E.; Sun, Y.; et al. Global Level Quantification of Histone Post-Translational Modifications in a 3D Cell Culture Model of Hepatic Tissue. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 2022, e63606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, M.L.; Tang, H.; Singh, V.K.; Khan, A.; Mishra, A.; Restrepo, B.I.; Jagannath, C.; Zhang, K. Multi-OMICs Analysis Reveals Metabolic and Epigenetic Changes Associated with Macrophage Polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, N.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Jia, Y.; He, Z.; Mo, T.; He, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Proteomic Quantification of Lysine Acetylation and Succinylation Profile Alterations in Lung Adenocarcinomas of Non-Smoking Females. Yonago Acta Medica 2022, 65, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, G.M.; Miele, E.; Wojchowski, D.M.; Toran, P.; Worsfold, C.R.; Anthonymuthu, T.S.; Bergo, V.B.; Zhang, A.X.; Silva, J.C. Affi-BAMSTM: A Robust Targeted Proteomics Microarray Platform to Measure Histone Post-Translational Modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searfoss, R.M.; Karki, R.; Lin, Z.; Robison, F.; Garcia, B.A. An Optimized and High-Throughput Method for Histone Propionylation and Data-Independent Acquisition Analysis for the Identification and Quantification of Histone Post-Translational Modifications. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 34, 2508–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macur, K.; Schissel, A.; Yu, F.; Lei, S.; Morsey, B.; Fox, H.S.; Ciborowski, P. Change of Histone H3 Lysine 14 Acetylation Stoichiometry in Human Monocyte Derived Macrophages as Determined by MS-Based Absolute Targeted Quantitative Proteomic Approach: HIV Infection and Methamphetamine Exposure. Clin. Proteom. 2023, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Ackerveken, P.; Lobbens, A.; Pamart, D.; Kotronoulas, A.; Rommelaere, G.; Eccleston, M.; Herzog, M. Epigenetic Profiles of Elevated Cell Free Circulating H3.1 Nucleosomes as Potential Biomarkers for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M.; Li, W.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Lu, M.; Xie, H.; Chen, Y. Quantitative Pattern of hPTMs by Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics with Implications for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vai, A.; Noberini, R.; Ghirardi, C.; de Paula, D.; Carminati, M.; Pallavi, R.; Araújo, N.; Varga-Weisz, P.; Bonaldi, T. Improved Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods Reveal Abundant Propionylation and Tissue-Specific Histone Propionylation Profiles. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2024, 23, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, M.; Lund, P.J.; Garcia, B.A. Optimized and Robust Workflow for Quantifying the Canonical Histone Ubiquitination Marks H2AK119ub and H2BK120ub by LC-MS/MS. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 5405–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhaya, P.; Pírek, P.; Zdráhal, Z.; Lochmanová, G. Arg-C Ultra Simplifies Histone Preparation for LC-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 12486–12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, E.; Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; Karki, R.; Searfoss, R.M.; de Luna Vitorino, F.N.; Lempiäinen, J.K.; Gongora, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, C.; et al. Development of a High-Throughput Platform for Quantitation of Histone Modifications on a New QTOF Instrument. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2025, 24, 100897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searfoss, R.M.; Zahn, E.; Lin, Z.; Garcia, B.A. Establishing a Top-Down Proteomics Platform on a Time-of-Flight Instrument with Electron-Activated Dissociation. J. Proteome Res. 2025, 24, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.-R.; Yen, C.-C.; Hu, C.-W. Prevention of Artifactual Oxidation in Determination of Cellular 8-Oxo-7,8-Dihydro-2′-Deoxyguanosine by Isotope-Dilution LC–MS/MS with Automated Solid-Phase Extraction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, M.; Pugh, T.J.; Fennell, T.J.; Stewart, C.; Lichtenstein, L.; Meldrim, J.C.; Fostel, J.L.; Friedrich, D.C.; Perrin, D.; Dionne, D.; et al. Discovery and Characterization of Artifactual Mutations in Deep Coverage Targeted Capture Sequencing Data Due to Oxidative DNA Damage during Sample Preparation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayana, S.H.; Spracklin, S.B.; Deharvengt, S.J.; Green, D.C.; Instasi, M.D.; Gallagher, T.L.; Shah, P.S.; Tsongalis, G.J. Standardized Workflow and Analytical Validation of Cell-Free DNA Extraction for Liquid Biopsy Using a Magnetic Bead-Based Cartridge System. Cells 2025, 14, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, C.A.; Thomas, S.N.; Sokoll, L.J.; Chan, D.W. Advances in Mass Spectrometry-Based Clinical Biomarker Discovery. Clin. Proteom. 2016, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, A.W.S.; Sugumar, V.; Ren, A.H.; Kulasingam, V. Emerging Role of Clinical Mass Spectrometry in Pathology. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 73, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robusti, G.; Vai, A.; Bonaldi, T.; Noberini, R. Investigating Pathological Epigenetic Aberrations by Epi-Proteomics. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noberini, R.; Robusti, G.; Bonaldi, T. Mass Spectrometry-based Characterization of Histones in Clinical Samples: Applications, Progress, and Challenges. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 1191–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stunnenberg, H.G.; Vermeulen, M. Towards Cracking the Epigenetic Code Using a Combination of High-throughput Epigenomics and Quantitative Mass Spectrometry-based Proteomics. BioEssays 2011, 33, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.