Cannabidiol Protects the Neonatal Mouse Heart from Hyperoxia-Induced Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Regulation of Oxidative Stress

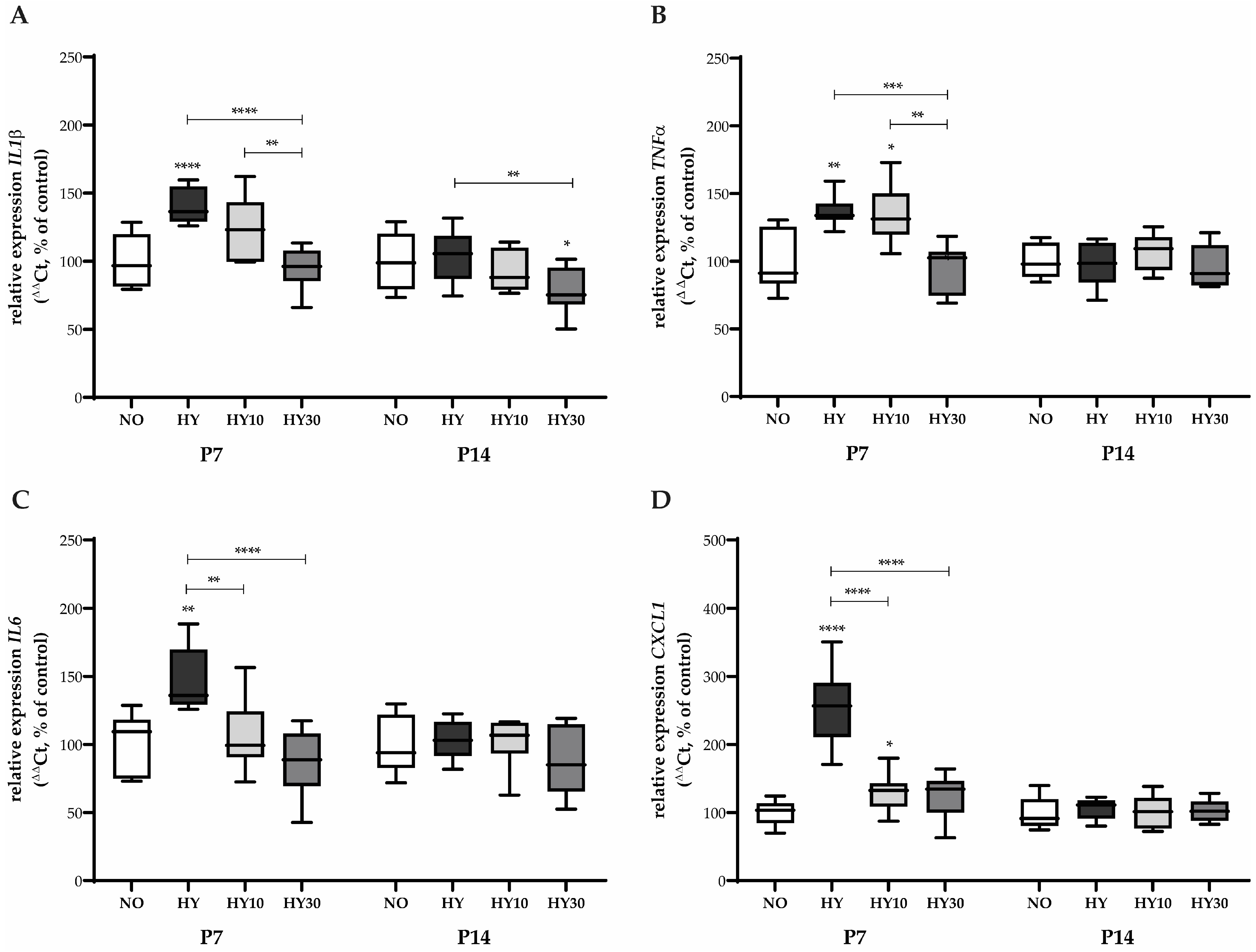

2.2. Impact on Inflammatory Cytokine and Chemokine Expression

2.3. Effects on Apoptotic and Autophagic Signaling Pathways

2.4. Morphometric and Histological Parameters of Cardiac Injury

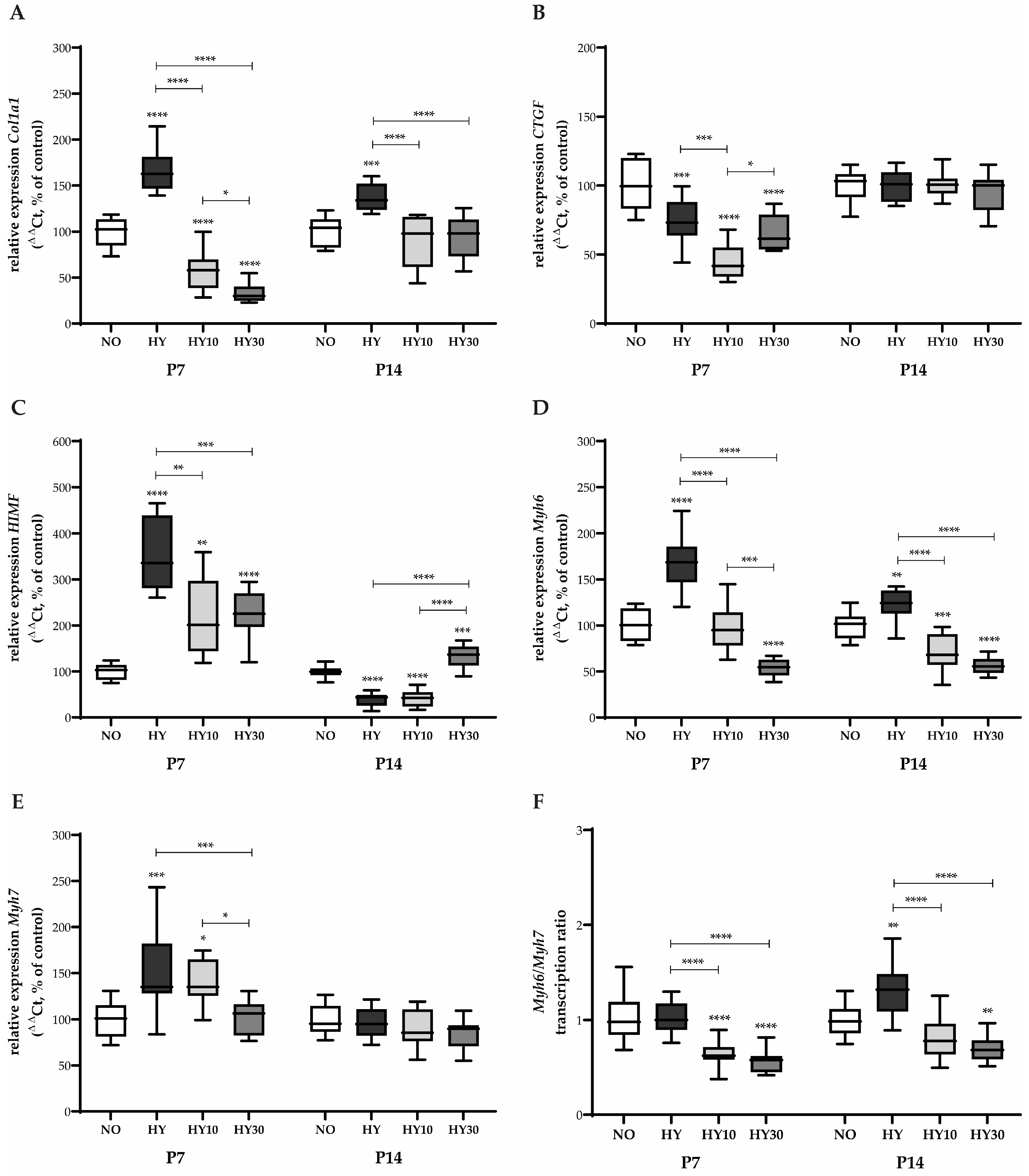

2.5. Gene Expression Changes in Cardiac Remodeling and Maturation

2.6. Effects on Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cell Cycle Regulation

2.7. Regulation of Cardiac Function and Growth Signaling

2.8. Sex-Specific Differences in the Cardiac Response to Hyperoxia and CBD Treatment

3. Discussion

3.1. Mechanistic Interpretation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cell Survival

3.2. Structural and Functional Effects of Cardiac Remodeling

3.3. CBD Effects on Hippo/YAP and Growth Signaling

3.4. Gender-Specific Differences in Response to Hyperoxia and CBD

3.5. Translational Relevance and Therapeutic Potential

3.6. Limitations

3.7. Future Research Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Welfare

4.2. Experimental Study Design

4.3. Drug Formulation and Dosing

4.4. Sampling and Processing Heart Tissue

4.5. RNA Extraction and qPCR

4.6. Sirius Red and HE Staining

4.7. Aspects of Morphometric and Histological Analysis

4.8. Immunohistochemistry, Image Acquisition, and Quantification

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sotiropoulos, J.X.; Oei, J.L.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Libesman, S.; Hunter, K.E.; Williams, J.G.; Webster, A.C.; Vento, M.; Kapadia, V.; Rabi, Y.; et al. Initial Oxygen Concentration for the Resuscitation of Infants Born at Less Than 32 Weeks’ Gestation: A Systematic Review and Individual Participant Data Network Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, R.; Mirza, M.; Baiton, A.; Lazuran, L.; Samokysh, L.; Bobinski, A.; Cowan, C.; Jaimon, A.; Obioru, D.; Al Makhoul, T.; et al. Oxygen toxicity: Cellular mechanisms in normobaric hyperoxia. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, M.; Robbins, M.E.; Revhaug, C.; Saugstad, O.D. Oxygen radical disease in the newborn, revisited: Oxidative stress and disease in the newborn period. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 142, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.D.; Yee, M.; Roethlin, K.; Prelipcean, I.; Small, E.M.; Porter, G.A., Jr.; O’Reilly, M.A. Whole genome transcriptomics reveal distinct atrial versus ventricular responses to neonatal hyperoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2025, 328, H832–H845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Groves, A.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Association of Preterm Birth with Long-term Risk of Heart Failure Into Adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Howell, E.A.; Stroustrup, A.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Association of Preterm Birth with Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, C.; Troughton, R.W.; Adamson, P.D.; Harris, S.L. Preterm birth and cardiac function in adulthood. Heart 2022, 108, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, A.J. Acute and chronic cardiac adaptations in adults born preterm. Exp. Physiol. 2022, 107, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, F.; McNamara, N.; Nanayakkara, S.; Doyle, M.P.; Williams, M.; Yaeger, L.; Marwick, T.H.; Leeson, P.; Levy, P.T.; Lewandowski, A.J. Changes in the Preterm Heart from Birth to Young Adulthood: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, K.N.; Haraldsdottir, K.; Beshish, A.G.; Barton, G.P.; Watson, A.M.; Palta, M.; Chesler, N.C.; Francois, C.J.; Wieben, O.; Eldridge, M.W. Association Between Preterm Birth and Arrested Cardiac Growth in Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, A.J.; Raman, B.; Bertagnolli, M.; Mohamed, A.; Williamson, W.; Pelado, J.L.; McCance, A.; Lapidaire, W.; Neubauer, S.; Leeson, P. Association of Preterm Birth with Myocardial Fibrosis and Diastolic Dysfunction in Young Adulthood. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.D.; Yee, M.; Porter, G.A., Jr.; Ritzer, E.; McDavid, A.N.; Brookes, P.S.; Pryhuber, G.S.; O’Reilly, M.A. Neonatal hyperoxia inhibits proliferation and survival of atrial cardiomyocytes by suppressing fatty acid synthesis. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e140785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, B.N.; Kimura, W.; Muralidhar, S.A.; Moon, J.; Amatruda, J.F.; Phelps, K.L.; Grinsfelder, D.; Rothermel, B.A.; Chen, R.; Garcia, J.A.; et al. The oxygen-rich postnatal environment induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through DNA damage response. Cell 2014, 157, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertagnolli, M.; Dartora, D.R.; Lamata, P.; Zacur, E.; Mai-Vo, T.A.; He, Y.; Beauchamp, L.; Lewandowski, A.J.; Cloutier, A.; Sutherland, M.R.; et al. Reshaping the Preterm Heart: Shifting Cardiac Renin-Angiotensin System Towards Cardioprotection in Rats Exposed to Neonatal High-Oxygen Stress. Hypertension 2022, 79, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFreitas, M.J.; Shelton, E.L.; Schmidt, A.F.; Ballengee, S.; Tian, R.; Chen, P.; Sharma, M.; Levine, A.; Katz, E.D.; Rojas, C.; et al. Neonatal hyperoxia exposure leads to developmental programming of cardiovascular and renal disease in adult rats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, M.O.R.; He, Y.; Bertagnolli, M.; Mai-Vo, T.A.; Fernandes, R.O.; Boudreau, F.; Cloutier, A.; Luu, T.M.; Nuyt, A.M. TLR (Toll-Like Receptor) 4 Antagonism Prevents Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Dysfunction Caused by Neonatal Hyperoxia Exposure in Rats. Hypertension 2019, 74, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravizzoni Dartora, D.; Flahault, A.; Pontes, C.N.R.; He, Y.; Deprez, A.; Cloutier, A.; Cagnone, G.; Gaub, P.; Altit, G.; Bigras, J.L.; et al. Cardiac Left Ventricle Mitochondrial Dysfunction After Neonatal Exposure to Hyperoxia: Relevance for Cardiomyopathy After Preterm Birth. Hypertension 2022, 79, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velten, M.; Hutchinson, K.R.; Gorr, M.W.; Wold, L.E.; Lucchesi, P.A.; Rogers, L.K. Systemic maternal inflammation and neonatal hyperoxia induces remodeling and left ventricular dysfunction in mice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sack, M.N.; Fyhrquist, F.Y.; Saijonmaa, O.J.; Fuster, V.; Kovacic, J.C. Basic Biology of Oxidative Stress and the Cardiovascular System: Part 1 of a 3-Part Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzel, T.; Camici, G.G.; Maack, C.; Bonetti, N.R.; Fuster, V.; Kovacic, J.C. Impact of Oxidative Stress on the Heart and Vasculature: Part 2 of a 3-Part Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oria, R.; Schipani, R.; Leonardini, A.; Natalicchio, A.; Perrini, S.; Cignarelli, A.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Cardiac Disease: From Physiological Response to Injury Factor. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 5732956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverne, Y.J.; Bogers, A.J.; Duncker, D.J.; Merkus, D. Reactive oxygen species and the cardiovascular system. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 862423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandali, K.S.; Belanger, M.P.; Wittnich, C. Hyperoxia causes oxygen free radical-mediated membrane injury and alters myocardial function and hemodynamics in the newborn. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 287, H553–H559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannavò, L.; Perrone, S.; Viola, V.; Marseglia, L.; Di Rosa, G.; Gitto, E. Oxidative Stress and Respiratory Diseases in Preterm Newborns. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lembo, C.; Buonocore, G.; Perrone, S. Oxidative Stress in Preterm Newborns. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramouni, K.; Assaf, R.; Shaito, A.; Fardoun, M.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Sahebkar, A.; Eid, A.H. Biochemical and cellular basis of oxidative stress: Implications for disease onset. J. Cell Physiol. 2023, 238, 1951–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, A.; Valenzuela, R.; Videla, L.A.; Zúñiga-Hernandez, J. Cellular Functional, Protective or Damaging Responses Associated with Different Redox Imbalance Intensities: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 3927–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertagnolli, M.; Huyard, F.; Cloutier, A.; Anstey, Z.; Huot-Marchand, J.E.; Fallaha, C.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Deblois, D.; Nuyt, A.M. Transient neonatal high oxygen exposure leads to early adult cardiac dysfunction, remodeling, and activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 2014, 63, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyongyosi, A.; Terraneo, L.; Bianciardi, P.; Tosaki, A.; Lekli, I.; Samaja, M. The Impact of Moderate Chronic Hypoxia and Hyperoxia on the Level of Apoptotic and Autophagic Proteins in Myocardial Tissue. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 5786742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benny, M.; Sharma, M.; Kulandavelu, S.; Chen, P.; Tian, R.; Ballengee, S.; Huang, J.; Levine, A.F.; Claure, M.; Schmidt, A.F.; et al. Protective role of CXCR7 activation in neonatal hyperoxia-induced systemic vascular remodeling and cardiovascular dysfunction in juvenile rats. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borger, M.; von Haefen, C.; Bührer, C.; Endesfelder, S. Cardioprotective Effects of Dexmedetomidine in an Oxidative-Stress In Vitro Model of Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocytes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Arellano, J.; Canseco-Alba, A.; Cutler, S.J.; León, F. The Polypharmacological Effects of Cannabidiol. Molecules 2023, 28, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, L.; Karimi, G.; Alavi, M.S.; Roohbakhsh, A. Pharmacological effects of cannabidiol by transient receptor potential channels. Life Sci. 2022, 300, 120582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosropoor, S.; Alavi, M.S.; Etemad, L.; Roohbakhsh, A. Cannabidiol goes nuclear: The role of PPARγ. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raïch, I.; Lillo, J.; Ferreiro-Vera, C.; Sánchez de Medina, V.; Navarro, G.; Franco, R. Cannabidiol at Nanomolar Concentrations Negatively Affects Signaling through the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, A.; Estes, E.; Aparasu, R.; Reddy, D.S. Clinical efficacy and safety of cannabidiol for pediatric refractory epilepsy indications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Neurol. 2023, 359, 114238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez Naya, N.; Kelly, J.; Corna, G.; Golino, M.; Abbate, A.; Toldo, S. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Action of Cannabidiol. Molecules 2023, 28, 5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Orgado, J.; Villa, M.; Del Pozo, A. Cannabidiol for the Treatment of Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 584533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruza, L.; Pazos, M.R.; Mohammed, N.; Escribano, N.; Lafuente, H.; Santos, M.; Alvarez-Díaz, F.J.; Hind, W.; Martínez-Orgado, J. Cannabidiol reduces lung injury induced by hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in newborn piglets. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 82, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Lazzara, F.; Thermos, K.; Zingale, E.; Spyridakos, D.; Romano, G.L.; Di Martino, S.; Micale, V.; Kuchar, M.; Spadaro, A.; et al. Retinal pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile of cannabidiol in an in vivo model of retinal excitotoxicity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 991, 177323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F.J.; Alvarez, A.A.; Rodríguez, J.J.; Lafuente, H.; Canduela, M.J.; Hind, W.; Blanco-Bruned, J.L.; Alonso-Alconada, D.; Hilario, E. Effects of Cannabidiol, Hypothermia, and Their Combination in Newborn Rats with Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. eNeuro 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, A.D.; Hoz-Rivera, M.; Romero, A.; Villa, M.; Martínez, M.; Silva, L.; Piscitelli, F.; Di Marzo, V.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, A.; Hind, W.; et al. Cannabidiol reduces intraventricular hemorrhage brain damage, preserving myelination and preventing blood brain barrier dysfunction in immature rats. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21, e00326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimasi, C.G.; Darby, J.R.T.; Morrison, J.L. A change of heart: Understanding the mechanisms regulating cardiac proliferation and metabolism before and after birth. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 1319–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensley, J.G.; Moore, L.; De Matteo, R.; Harding, R.; Black, M.J. Impact of preterm birth on the developing myocardium of the neonate. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 83, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraps, N.; Tirre, M.; Pyschny, S.; Reis, A.; Schlierbach, H.; Seidl, M.; Kehl, H.G.; Schänzer, A.; Heger, J.; Jux, C.; et al. Cardiomyocyte maturation alters molecular stress response capacities and determines cell survival upon mitochondrial dysfunction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 213, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huestis, M.A.; Solimini, R.; Pichini, S.; Pacifici, R.; Carlier, J.; Busardò, F.P. Cannabidiol Adverse Effects and Toxicity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 974–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonhofen, P.; Bristot, I.J.; Crippa, J.A.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Zuardi, A.W.; Parsons, R.B.; Klamt, F. Cannabinoid-Based Therapies and Brain Development: Potential Harmful Effect of Early Modulation of the Endocannabinoid System. CNS Drugs 2018, 32, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurič, D.M.; Bulc Rozman, K.; Lipnik-Štangelj, M.; Šuput, D.; Brvar, M. Cytotoxic Effects of Cannabidiol on Neonatal Rat Cortical Neurons and Astrocytes: Potential Danger to Brain Development. Toxins 2022, 14, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccetto, S.L.; Black, T.; Barnard, I.L.; Macfarlane, L.M.; Sanfuego, G.B.; Laprairie, R.B.; Howland, J.G. Neurodevelopmental outcomes following prenatal cannabidiol exposure in male and female Sprague Dawley rat offspring. Neuroscience 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkelhamer, S.K.; Kim, G.A.; Radder, J.E.; Wedgwood, S.; Czech, L.; Steinhorn, R.H.; Schumacker, P.T. Developmental differences in hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress and cellular responses in the murine lung. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Tataranno, L.M.; Stazzoni, G.; Ramenghi, L.; Buonocore, G. Brain susceptibility to oxidative stress in the perinatal period. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015, 28, 2291–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Cuevas, I.; Corral-Debrinski, M.; Gressens, P. Brain oxidative damage in murine models of neonatal hypoxia/ischemia and reoxygenation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 142, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endesfelder, S.; Weichelt, U.; Strauss, E.; Schlor, A.; Sifringer, M.; Scheuer, T.; Buhrer, C.; Schmitz, T. Neuroprotection by Caffeine in Hyperoxia-Induced Neonatal Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endesfelder, S.; Strauß, E.; Scheuer, T.; Schmitz, T.; Bührer, C. Antioxidative effects of caffeine in a hyperoxia-based rat model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endesfelder, S.; Strauß, E.; Bendix, I.; Schmitz, T.; Bührer, C. Prevention of Oxygen-Induced Inflammatory Lung Injury by Caffeine in Neonatal Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 3840124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giszas, V.; Strauß, E.; Bührer, C.; Endesfelder, S. The Conflicting Role of Caffeine Supplementation on Hyperoxia-Induced Injury on the Cerebellar Granular Cell Neurogenesis of Newborn Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 5769784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, J.; Schmitz, T.; Bührer, C.; Endesfelder, S. Protective Effects of Early Caffeine Administration in Hyperoxia-Induced Neurotoxicity in the Juvenile Rat. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puls, R.; von Haefen, C.; Bührer, C.; Endesfelder, S. Dexmedetomidine Protects Cerebellar Neurons against Hyperoxia-Induced Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in the Juvenile Rat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kletkiewicz, H.; Wojciechowski, M.S.; Rogalska, J. Cannabidiol effectively prevents oxidative stress and stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) in an animal model of global hypoxia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaksar, S.; Bigdeli, M.; Samiee, A.; Shirazi-Zand, Z. Antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects of cannabidiol in model of ischemic stroke in rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 180, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, M.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Bátkai, S.; Patel, V.; Saito, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Kashiwaya, Y.; Horváth, B.; Mukhopadhyay, B.; Becker, L.; et al. Cannabidiol attenuates cardiac dysfunction, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and inflammatory and cell death signaling pathways in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 2115–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urlić, H.; Kumrić, M.; Pavlović, N.; Dujić, G.; Dujić, Ž.; Božić, J. Cardiovascular Effects of Cannabidiol: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implementation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepebaşı, M.Y.; Aşcı, H.; Özmen, Ö.; Taner, R.; Temel, E.N.; Garlı, S. Cannabidiol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiovascular toxicity by its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity via regulating IL-6, Hif1α, STAT3, eNOS pathway. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Tong, C.; Cong, P.; Mao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, M.; Piao, Y.; et al. Protective effect and mechanism of cannabidiol on myocardial injury in exhaustive exercise training mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 365, 110079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, M.A.; Fathy Mohamed, Y.; Fernandez, R.; Ruben, P.C. Anti-inflammatory effects of cannabidiol against lipopolysaccharides in cardiac sodium channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 5259–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrselja, A.; Pillow, J.J.; Bensley, J.G.; Ellery, S.J.; Ahmadi-Noorbakhsh, S.; Moss, T.J.; Black, M.J. Intrauterine inflammation exacerbates maladaptive remodeling of the immature myocardium after preterm birth in lambs. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 92, 1555–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, R.; Masotti, S.; Musetti, V.; Rocchiccioli, S.; Prontera, C.; Perrone, M.; Passino, C.; Clerico, A.; Caselli, C. Cardiac troponins: Mechanisms of release and role in healthy and diseased subjects. Biofactors 2023, 49, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.C.; Gaze, D.C.; Collinson, P.O.; Marber, M.S. Cardiac troponins: From myocardial infarction to chronic disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 1708–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, C.; Walker, J.W.; Huang, X. Progressive troponin I loss impairs cardiac relaxation and causes heart failure in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H1273–H1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.J.; Jin, J.P. Gene regulation, alternative splicing, and posttranslational modification of troponin subunits in cardiac development and adaptation: A focused review. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.J.; Jin, J.P. TNNI1, TNNI2 and TNNI3: Evolution, regulation, and protein structure-function relationships. Gene 2016, 576, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Feijen, A.; Korving, J.; Korchynskyi, O.; Larsson, J.; Karlsson, S.; ten Dijke, P.; Lyons, K.M.; Goldschmeding, R.; Doevendans, P.; et al. Connective tissue growth factor expression and Smad signaling during mouse heart development and myocardial infarction. Dev. Dyn. 2004, 231, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, A.; van Bilsen, M.; Goldschmeding, R.; van der Vusse, G.J.; van Nieuwenhoven, F.A. Connective tissue growth factor and cardiac fibrosis. Acta Physiol. 2009, 195, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Khanna, S.; Azad, A.; Schnitt, R.; He, G.; Weigert, C.; Ichijo, H.; Sen, C.K. Fra-2 mediates oxygen-sensitive induction of transforming growth factor beta in cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, M.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cardounel, A.J.; Swartz, H.M.; He, G. Hyperoxia and transforming growth factor β1 signaling in the post-ischemic mouse heart. Life Sci. 2013, 92, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.; Kanisicak, O.; Prasad, V.; Correll, R.N.; Fu, X.; Schips, T.; Vagnozzi, R.J.; Liu, R.; Huynh, T.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Fibroblast-specific TGF-β-Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3770–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cai, A.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lan, L.; Guo, X.; Yan, H.; Gao, X.; Li, H.; et al. Cannabidiol represses miR-143 to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration after myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 963, 176245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, T.; Li, J.; Liang, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, M.; Yang, G.; Wu, D. Cannabidiol Ameliorates Doxorubicin-Induced Myocardial Injury via Activating Hippo Pathway. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2025, 19, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, H.E. Female cardiovascular biology and resilience in the setting of physiological and pathological stress. Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.L.; Rodgers, L.E.; Tian, Z.; Allen-Gipson, D.; Panguluri, S.K. Sex differences in murine cardiac pathophysiology with hyperoxia exposure. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElBeck, Z.; Hossain, M.B.; Siga, H.; Oskolkov, N.; Karlsson, F.; Lindgren, J.; Walentinsson, A.; Koppenhöfer, D.; Jarvis, R.; Bürli, R.; et al. Epigenetic modulators link mitochondrial redox homeostasis to cardiac function in a sex-dependent manner. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Shirazi, J.; Gleghorn, J.P.; Lingappan, K. Pulmonary endothelial cells exhibit sexual dimorphism in their response to hyperoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H1287–H1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanska, H.H.; Petrlakova, K.; Papouskova, B.; Hendrych, M.; Samadian, A.; Storch, J.; Babula, P.; Masarik, M.; Vacek, J. Safety assessment and redox status in rats after chronic exposure to cannabidiol and cannabigerol. Toxicology 2023, 488, 153460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagno, M.K.; Silver, C.R.; Cox-Holmes, A.; Basso, K.B.; Bishop, C.; Bernstein, A.M.; Carley, A.; Cazorla, J.; Claydon, J.; Crane, A.; et al. Maternal ingestion of cannabidiol (CBD) in mice leads to sex-dependent changes in memory, anxiety, and metabolism in the adult offspring, and causes a decrease in survival to weaning age. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2025, 247, 173902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Cuapio, E.; Coronado-Álvarez, A.; Quiroga, C.; Alcaraz-Silva, J.; Ruíz-Ruíz, J.C.; Imperatori, C.; Murillo-Rodríguez, E. Juvenile cannabidiol chronic treatments produce robust changes in metabolic markers in adult male Wistar rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 910, 174463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, J.; Sonntag, H.J.; Tang, M.K.; Cai, D.; Lee, K.K. Integrative Analysis of the Developing Postnatal Mouse Heart Transcriptome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Exp. Physiol. 2020, 105, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hellberg, T.; Schmitz, T.; Bührer, C.; Endesfelder, S. Cannabidiol Protects the Neonatal Mouse Heart from Hyperoxia-Induced Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010146

Hellberg T, Schmitz T, Bührer C, Endesfelder S. Cannabidiol Protects the Neonatal Mouse Heart from Hyperoxia-Induced Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010146

Chicago/Turabian StyleHellberg, Teresa, Thomas Schmitz, Christoph Bührer, and Stefanie Endesfelder. 2026. "Cannabidiol Protects the Neonatal Mouse Heart from Hyperoxia-Induced Injury" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010146

APA StyleHellberg, T., Schmitz, T., Bührer, C., & Endesfelder, S. (2026). Cannabidiol Protects the Neonatal Mouse Heart from Hyperoxia-Induced Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010146