Abstract

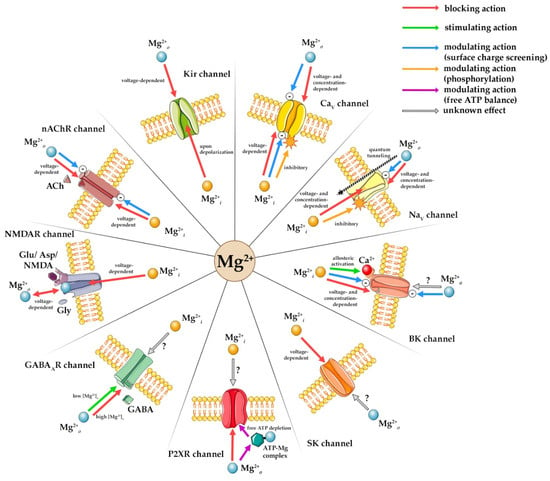

Magnesium ions regulate synaptic and nonsynaptic neuronal excitability from intracellular (Mg2+i) and extracellular (Mg2+o) domains, modulating voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels. K+ inward rectifier (Kir) channel inward rectification arises from Mg2+i blocking the pore and outward K+ current, while Mg2+o targets external sites. Mg2+i causes voltage-dependent Ca2+ voltage-gated (CaV) and Na+ voltage-gated (NaV) channel block while phosphorylation modulates channel activity. Mg2+o elicits direct voltage-dependent CaV channel block, and screens surface charge, and in NaV channels reduces conduction and may cause depolarization by quantum tunneling across closed channels. Mg2+i is an allosteric large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channel activator, binding to low-affinity sites to alter Ca2+ and voltage sensitivity but reduces small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels’ outward K+ current and induces inward rectification. N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) channels are inhibited by Mg2+i binding within the pore, while Mg2+o stabilizes excitability through voltage-dependent block, Mg2+o forms Mg-ATP complex modifying purinergic P2X receptor (P2XR) channel affinity and gating and directly blocks the pore. Mg2+o reduces gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR) channel Cl− current amplitude and augments susceptibility to blockers. Mg2+o and Mg2+i block nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) channels through voltage-dependent pore binding and surface charge screening, impeding current flow and altering gating.

Keywords:

magnesium; Kir channel; CaV channel; NaV channel; BK channel; SK channel; NMDAR; P2XR; GABAAR; nAChR 1. Introduction

Magnesium (Mg) is a mineral micronutrient bioessential for human health and wellbeing. In our cells and tissues, it serves many structural and metabolic functions, as well as important electrophysiological roles. Magnesium ion (Mg2+) is an electrolyte present in all our body fluids with a dominant intracellular distribution. In the brain, Mg2+ is ubiquitous, but more abundant in the cerebrospinal and interstitial fluid than in the blood, reflecting high neuronal demand for Mg2+. Within the nerve cells, Mg2+ distribution is compartmentalized, with specific localization in different cellular structures: the cytoplasm, cell nucleus, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Since mitochondria serve as the site of cellular respiration and major adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, they also store the highest concentration of Mg2+ in the cell. They have the capacity to actively accumulate Mg2+ and release it in response to various biological stimuli. In eukaryotic cells, mitochondrial Mg2+ dynamics and Mg2+ permeation across the inner mitochondrial membrane are facilitated by specific Mg2+-sensitive channels [1]. Several other transporters and exchangers have been identified on the cell membrane and organelles’ membranes responsible for maintaining cellular Mg2+ homeostasis [2]. Studies focusing on the effects of intracellular Mg2+ (Mg2+i) on cell energy metabolism report several mechanisms of modulation of oxidative phosphorylation by Mg2+ in the mitochondrial matrix. The impact of Mg2+i on cell respiration is described to be manifold, with a resulting enhancement of mitochondrial ATP synthesis [3].

Mg2+ ions distributed throughout the cell and across various compartments serve many distinct roles, critical for neuronal health and activity. Magnesium is essential for various nerve cell functions, including enzyme activation, protein synthesis, genome stabilization, cell cycle regulation, energy metabolism, regulation of biochemical pathways, signaling pathways, and modulation of membrane ion transport mechanisms. Little is known that other than intracellular Ca2+ ion (Ca2+i), Mg2+i can also be considered an intracellular messenger, as Mg2+i relays signals within the cell between different compartments. This, in fact, refers to the free, unbound form of Mg2+i, also known as the ionized Mg2+ fraction, physiologically present in low concentrations in the cytosol of the resting cell (0.5–1.2 mmol/L) [4]. Cytosolic Mg2+ fluctuations occur upon stimulation by various extra- or intracellular stimuli, whereby Mg2+i concentrations ([Mg2+]i) can change dynamically. Mg2+i can rapidly be mobilized from the cellular stores or enter from the extracellular fluid, and act as a signal transducer and cellular regulator to perform many roles. It can directly control the activity of various target cell molecules: proteins, enzymes, nucleotides, ATP, etc., usually by binding to their specific motifs [5].

The concentration of free, ionized Mg2+ in human brain tissue fluid measures approximately 0.5 mmol/L (as determined by 31P phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy), which is similar to that in nerve cell cytosol, adequate to ATP levels and energy demands of central neurons. In the blood and all our body fluids, Mg2+ exists in two main forms: the bound form (comprising the protein-bound Mg2+ and Mg2+ complexed with different ligands, including ATP), and the free form (ionized Mg2+ or unbound Mg2+). These three Mg2+ fractions (three states in which Mg2+ can be found) exist in equilibrium, but with constant dynamic Mg2+ shifts between them. It is the ionized Mg2+ fraction (iMg2+) that is free to exert regulatory Mg2+ effects (metabolic, immune, and electrophysiological). Only the iMg2+ is available for biological actions, being unbound and exchangeable between the compartments of body fluids. Although frequent Mg2+ shifts occur, equilibrium is maintained in a manner that both intra- and extracellular concentrations of iMg2+ are physiologically stable and approximately equal. Assessing the Mg2+i and extracellular (outer) Mg2+ (Mg2+o) levels in the brain provides better insights into neuronal Mg2+ homeostasis and its involvement in cell signaling, electrophysiology, and bioenergetics [6]. From both the intra- and the extracellular side of the cell membrane, Mg2+ serves the role of a regulatory cation, known for its overall stabilizing effect on electrically excitable membranes. Its homeostasis helps maintain the physiological functions of central neurons in a complex manner and even more tightly than in other types of excitable cells. Many of its actions couple cell metabolism to its electrical activity [4].

Regular neural and muscular electrical excitability and conductivity are essential to enable proper vital body functions such as sensorineural alertness, consciousness, and other nervous system functions, heart action, blood circulation, and respiration. Other than the traditionally considered electrolytes (Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Cl−), Mg2+ is also required for their maintenance, although it is frequently neglected when testing for the routine blood serum ionogram. Clinical implications of imbalances of Mg2+ metabolism are numerous. Systemic Mg2+ homeostasis with stable concentrations of Mg2+ ([Mg2+]) in the whole body is required for human health. On the other hand, chronic Mg2+ deficiency is associated with chronic low-grade hyperexcitability [4]. Because of its many pathophysiological effects, such as Mg2+ may be a biomarker of poor outcomes and unwanted cardiovascular events, including death, angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, arrhythmias, and stroke [7]. In the fields of neurology, neuropsychiatry, neurosurgery, and neurorehabilitation, it is implicated in a number of conditions, like epilepsy, anxiety, depression, migraine and tension headache, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, stroke recovery, cerebral vasospasm, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, etc. [8,9]. In order to better understand the potency of Mg2+ deficiency to mediate neuropathophysiological mechanisms of these diseases, one must comprehend well the basic electrophysiological effects of Mg2+ on a molecular level. This review aims to present some of them, affecting major voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels of central neurons.

2. Intracellular and Extracellular Magnesium as Modulators of Ion Channel Function

Ion channels are integral membrane proteins that allow the selective passage of ions across cellular membranes. Their activity is tightly regulated by voltage changes, ligand binding, and intracellular signaling molecules. Magnesium, the most abundant divalent intracellular cation, plays a dual role in modulating ion channels depending on its localization. Magnesium ions can affect both voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels, from both the extracellular and intracellular sides of the membrane. Due to their double positive charge, Mg2+ ions in aqueous solutions and all body fluids carry a large surface charge that strongly attracts dipoles of water molecules. In this hydrated state, as Mg2+(aq), they have a large ionic radius, which does not prevent them from being attracted to charged binding sites in the pores of ion channels more specific for some other ions (such as Ca2+, K+, or Na+). However, their double hydration shell is not easy to shed, making it very difficult for Mg2+(aq) ions to pass through the narrow pores of ion channels in biological membranes. This makes Mg2+ a suitable modulator of activity in a number of different ion channels. Once Mg2+ ions bind within the channel pore, it becomes challenging for the competing cations to displace it, and channel permeation becomes blocked [10]. Over time, it has been shown that Mg2+ influences ion channel function through several mechanisms, such as electrostatic interactions with channel pores or gating domains, allosteric modulation of channel conformation, surface charge shift that alters membrane potential sensing, or competition with other cations (Ca2+, Na+) for binding or permeating the channel pore.

Magnesium acts as an important determinant in physiological and pathophysiological conditions, and the mechanisms of its action that underlie therapeutic potential are of great interest to basic scientists and practicing clinicians. However, we are still lacking complete knowledge regarding the precise mechanisms of Mg2+ effects on excitable membranes. Understanding structural interactions of Mg2+ with different ion channels, ramifications of these interactions, and their effects on channel functionality, is thereafter crucial for our comprehension of the mechanisms underlying alterations of functions of excitable membranes associated with magnesium imbalances, as well as the effects of potential therapeutic applications of magnesium in the conditions of magnesium deficiency. Therefore, we aim here to present an overview of research data on the interactions between Mg2+i and Mg2+o with some of the most important voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels shown to be affected by Mg2+ (Figure 1).

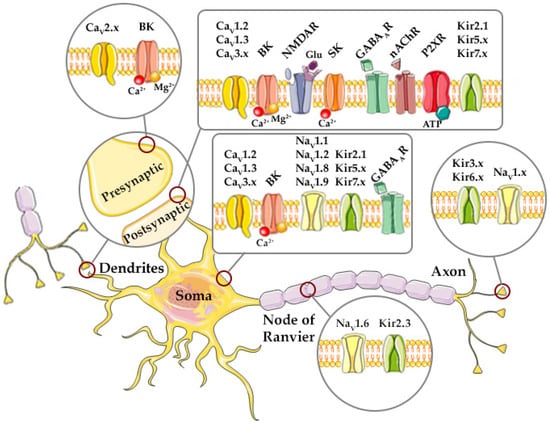

Figure 1.

Localization of major voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels in neurons shown to be regulated by Mg2+. Kir—inward rectifier K+ channel, CaV—voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, NaV—voltage-gated Na+ channel, BK—large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, SK—small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, P2XRs—purinergic P2X receptors, NMDAR—N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptor, Glu—glutamate, GABAAR—type A Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid Receptor, nAChR—nicotinic ACh receptor. Adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com).

2.1. Voltage-Gated Ion Channels Regulated by Mg2+

Voltage-gated channels (VGCs) are transmembrane proteins that mediate ion flux across the cell membrane in response to changes in membrane potential. They play a pivotal role in electrical signaling processes in the body–neurotransmission, muscle contraction, and hormone secretion. The canonical action of these channels arises from an interplay of their components and functions, (a) channel voltage sensing is mediated by special voltage-sensing domains (VSD), (b) conformational changes of channel pores shift between pore opening and pore closing, (c) channels actively transition from open state to closed state, while channel inactivation results from a state of a channel already closed but which cannot be reopened temporarily, and finally (d) ion selectivity of some VGCs comes from specific ion-selectivity filter regions within the channel pore. Magnesium ions, normally present in the extracellular and intracellular fluids (both cytosolic and subcellular compartments), can affect the function of VGCs. Perturbations in the [Mg2+], even within their physiological range, can augment changes in channel activity. These effects are more prominently seen with [Mg2+]i changes and with larger variations in Mg2+o concentration ([Mg2+]o) changes. Here we present the findings concerning Mg2+ effects on several voltage-gated ion channels, inward rectifier K+ channels, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, voltage-gated Na+ channels, and large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, primarily in nerve cells, but also in some other cell types (microglia, astrocytes, cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells).

2.1.1. Mg2+ Effects on Inward Rectifier Potassium (Kir) Channels

Kir channels allow influx of K+ ions into the cells and conduct a more inward K+ current during hyperpolarizing membrane potentials (negative to the K+ equilibrium potential), while restricting outward K+ current amid membrane depolarization [11,12,13]. These channels are tetramers, and each subunit contains two transmembrane (TM) helices (the outer, TM1 helix and the inner, TM2 helix), linked by the pore-forming region (H5) that carries the ion-selectivity filter and large N-terminal (amino, NH2−) and C-terminal (carboxy, COOH-) regions that constitute the cytoplasmic domain (CTD). The Kir channel structure is missing a VSD [14].

Functional studies suggest that K+ ions interact with certain charged residues in the Kir channel CTD, while traversing the extended channel pore composed of the CTD pore and TM pore [15]. The selectivity filter at the extracellular region of the channel pore can also serve as a gating element [16]. Though not being voltage-gated, Kir channels are of interest due to a highly voltage-dependent block of outward K+ currents, elicited by Mg2+i [11,12,17,18,19,20]. This group of K+-selective ion channels is critical for maintaining the resting membrane potential, regulating neuronal and myocyte excitability, and facilitating K+ homeostasis in the nervous system. For example, Kir1.1 channels act as K+ transporters, regulating their excretion and electrolyte balance as they are expressed in renal tubules [14], but their function in the hippocampus and cortex still remains unknown [21]. Kir2.1 channels are expressed diffusely in the whole brain, on neuron somata and dendrites, endothelium, heart muscle, vascular smooth muscles and skeletal muscles, Kir2.2 channels throughout the forebrain and strongly in the cerebellum, but also in the myocardium and skeletal muscles, Kir2.3 channels mainly in the forebrain, olfactory bulb, cardiomyocytes and skeletal myocytes and in the microvilli of Schwann cells at nodes on Ranvier, while Kir2.4 are found in the cranial nerve motor nuclei in the midbrain, pons, and medulla. Since being expressed in excitable tissues, the Kir2.x family helps maintain resting membrane potential and contributes to cardiac excitability. Kir3.1, Kir3.2, and Kir3.3 channel types are expressed throughout the brain, some such as Kir3.2 in homomeric form or as Kir3.1/3.2, Kir 3.2/3.3 heteromers, and mediate inhibitory neurotransmission. Kir4.1 and Kir5.1 channels are expressed on astrocytes in the brain either in Kir4.1 homomeric or Kir4.1/5.1 heteromeric form, respectively, and they mediate K+ buffering, which is important for the control of neuronal function in the central nervous system (CNS), but also in the spinal cord, retina, and stria vascularis in the inner ear. Kir6.x channels are expressed in all muscle cell types, the brain, and the pancreas, and act as metabolic sensors, while Kir7.1, found in the retina, contributes to ion transport and visual function [14,21].

Effects of Mg2+i on Kir Channels

Inward rectification of Kir channels is considered to result from an endogenous effect of Mg2+ binding to the channel from the cytoplasmatic, intracellular side, as registered in isolated murine cardiomyocytes [11,14,22], murine erythroleukaemia (MEL) cells expressing Kir1 channels [23], or modeled in silico [15]. At resting membrane potential level, electrostatic forces repel Mg2+ from the channel pore, allowing for inward K+ conduction, while membrane depolarization allows Mg2+i to flow into the Kir channel pore, physically blocking it and inhibiting the efflux of K+ ions, thus stabilizing membrane potential in neurons and glial cells [15,21]. This competitive blockage of Kir channels by Mg2+i at depolarizing membrane potentials is crucial for the magnitude of the outward K+ current and K+ balance within the cell. Additionally, this block allows astrocytes to uptake an excess of extracellular K+ ions to prevent hyperexcitability during high neuronal activity [14]. Mg2+i produces a rapid block of outward K+ current in bovine vascular endothelial cells, but there seems to be an internal additional voltage-dependent gating mechanism free of Mg2+ influence, leading to closure of Kir channels [24]. Mg2+ (0.1 mmol/L) on the cytoplasmatic side of the membrane diminishes the outward K+ currents through open Kir channels, which become flickery, while there is no effect of Mg2+i on the inward currents [12,18,19]. Electrophysiological experiments on murine ventricular cardiomyocytes show that progressive increase of [Mg2+]i modifies the outward K+ current, which evolves from an open channel current to zero-current level, as [Mg2+]i reaches 1 mmol/L [12,18]. Mg2+ ions have a diameter close to that of K+ ions, making it able to block the channels that permeate K+ and possess K+-binding sites [21].

Over time, it was established that Kir channel subunits possess more than one binding site for Mg2+. Mg2+i can interact with negatively charged residues of the Kir channel pore lining in the cytoplasmatic and transmembrane portion of the channel in the process of rectification [15]. Based on the sensitivity to Mg2+i block, Kir channels are recognized as either strong or weak inward rectifiers [17]. Electrophysiological experiments on Xenopus oocytes expressing various Kir channel mutants identified one of the crucial sites within the channel pore for Mg2+ to bind. This site is in the vicinity of a negatively charged residue, aspartate (Asp) side chain in position 171, as it is shown that substitution of Kir1.1 channel’s polar uncharged asparagine (Asn) with negatively charged Asp in this position (N171D) elicits a 20-fold stronger affinity of the channel to Mg2+ and blocks outward K+ currents [17]. Additionally, findings from the same model, expressing mutant Kir channels, reveal that a single substitution of Asp within the channel’s transmembrane M2 domain at position 172 with Asn (D172N) transforms a strong inward rectifier Kir2.1 channel into a channel with weak rectifier-like properties. Reversed substitution of Asn in position 171 with Asp (N172D) converts a weak rectifier Kir into a channel with a strong rectifier nature [25]. These findings are corroborated on MEL cells by showing that a mutation induced to a Kir2.1 channel, altering negatively charged Asp in position 172 to uncharged glutamine (Gln) (D172Q), reduces the channel’s affinity to Mg2+i more than five-fold [26]. Electrophysiological experiments on oocytes expressing mutant Kir channels suggest another site that is involved in channel rectification. Changing the negatively charged glutamate (Glu) in position 224 of the CTD C-terminus with non-polar glycine (Gly) or polar uncharged Gln or serine (Ser) (E224G/Q/S, respectively) drastically reduces rectification of the mutant channel. Furthermore, it is possible that the Asp residue at position 172 interacts with the Glu residue at position 224 to form a binding pocket for Mg2+ [27]. Multiscale modeling was utilized to investigate the path that Mg2+i crosses from the cytoplasm through the Kir2.1 channel pore, reaching the conclusion that these ions extensively interact with a negatively charged Glu residue in position 299 at the center of the intracellular domain, in order to block K+ outward current [28].

Membrane patches excised from murine cardiomyocytes [11], oocytes expressing Kir channels [29] or vascular endothelial cells [24] used to record single Kir channel currents exhibit rapid rundown of Kir activity in an internal solution containing physiological [Mg2+]i (~1 mmol/L), but restore channel rectification capability, while channel activity in Mg2+-free solution, although preserved, leads to a loss of inward rectification. Although it was initially thought that changes in intracellular K+ concentration ([K+]i) have little to no effect on the blocking action of Mg2+i on Kir outward currents [19], it is now known that a decrease in [K+]i augments the blocking affinity of Mg2+i on Kir1.1 expressed on Xenopus oocytes [30]. Additionally, as extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o) increases, the Mg2+i blocking affinity for different families of Kir channels decreases, and a stronger depolarization is required to achieve the same amount of Kir blockage by Mg2+i [17,30].

Effects of Mg2+o on Kir Channels

Mg2+o can also modulate the activity of Kir channels. Electrophysiological recordings of membrane patches of vascular endothelial cells [24], oocytes expressing Kir2.1 [31], Kir2.2 [16] or Kir1.1 [20] channels exposed to increasing concentrations of Mg2+o demonstrate a decay of Kir channel activity, a reduction in the outward K+ current amplitude, and a rise in the extent of Kir channel inactivation. Removal of extracellular bivalent cations, such as Mg2+, reduces the extent of Kir channel voltage-dependent inhibition [16,20,24]. Presence of Mg2+o elicits longer periods of Kir channel closure intermittently separated by bursts of channel activity reflecting Mg2+ entry, association with the channel pore binding site, followed by dissociation from the site and exit from the channel [24]. Inward rectifier K+ channels (Kir2.1) expressed on Xenopus oocytes exhibit greater sensitivity to Mg2+o-induced voltage-dependent block than Kir2.2 and Kir2.3 channels. One of the mechanisms underlying this effect might be the interaction of Mg2+o with a negatively charged Glu residue at position 125 located in the extracellular loop between TM1 and pore domain (PD) of Kir2.1 channel. Substitution of Glu with Asp (E125D) preserves the sensitivity to Mg2+o-induced block of the mutant channel, proving that the negatively charged amino acid residue at position 125 is potentially a binding site for Mg2+o. Moreover, mutant Kir2.1 channel with polar uncharged Gln instead of Glu (E125Q) reduces channel sensitivity to Mg2+o, whereas substitution of Gln (Q126E) in mutant Kir2.2 and positively charged histidine (His) (H116E) in mutant Kir2.3 channels with Glu increases their sensitivity to Mg2+o block [32]. However, an increase in [K+]o reduces the Mg2+o-induced blocking effect on Kir channel activity, possibly by competing for the same binding site in the channel pore in murine cardiomyocytes [11,19], endothelial cells [24] and oocytes expressing Kir2.1 [31,32], Kir2.2 [16] or Kir1.1 [20] channels. Specific residues in the outer region of the channel could constitute a functional K+ sensor that alters its activity to changes in [K+]o. Negatively charged amino acid residues of the outer mouth of the Kir channel and the pore’s selectivity filter attract K+ ions, increasing their concentration in this region. Electrostatic repulsion between cations potentially repels Mg2+ from binding to the channel, thus reducing Mg2+o-induced voltage-dependent block of inward K+ current [16].

Finally, concerning other types of voltage-gated K+ (KV) channels, there are findings that KV1-KV3 are susceptible to increasing [Mg2+]i as it blocks outward K+ currents in a voltage-dependent manner [33,34]. Membrane depolarization can enhance Mg2+i blocking action of KV1.5 and KV2.1 channels to the degree that channels exhibit inward rectification in the presence of Mg2+i at positive membrane voltages, reminiscent of Kir channels [33]. In addition to the direct channel pore block, Mg2+i modulates the channel’s voltage sensor activity by screening negative cytosolic surface charges and shifts activation and inactivation to more negative membrane potentials [33,35]. Contrary to its direct channel blocking action, Mg2+i decreases KCNQ (K+ voltage-gated channel subfamily Q, KV7) channel currents by binding phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a membrane lipid instrumental for KCNQ channel activation, thereby leaving only a limited fraction of free PIP2 available to interact with the channel [36]. Conversely, voltage-dependent activation of EAG (ether-à-go-go, KV10) and hERG (human ether-à-go-go related gene, KV11) channels is modulated by Mg2+o, slowing the channel’s gating kinetics and transition to an open state as it screens negatively charged amino acid residues in the channel’s voltage-sensing region [37,38,39,40].

2.1.2. Mg2+ Effects on Voltage-Gated Calcium (CaV) Channels

In response to membrane depolarization, CaV channels mediate Ca2+ influx that regulates neurotransmitter release, excitability, and intracellular signaling in neurons; cardiac action potential (AP); muscle contractions; hormone secretion; and gene transcription. These channels consist of a pore-forming CaVα1 subunit and auxiliary subunits that attune gating activity–an intracellular CaVβ-subunit (CaVβ1–CaVβ4) and a complex extracellular CaVα2δ-subunit (CaVα2δ1–CaVα2δ4) [41,42]. The CaVα1 subunit is composed of four homologous repeats (I–IV), each containing six TM helices (S1-S6), where S5 and S6 form channel PD, a loop linking S5 and S6 (p-loop) carries the Ca2+ selectivity filter region, while S1–S4 helices constitute channel VSD [43]. CaV channels are classified into three subfamilies. Firstly, CaV1.1–CaV1.4 channels are defined as L-type for their large, long-lasting currents or as dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs) due to their sensitivity to dihydropyridine (DHP). CaV1.1 channels are expressed in skeletal muscles and CaV1.4 channels in the retina, while CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 channels are present in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle cells, sinoatrial node (SAN), neuron soma and dendrites in the brain, intestinal/bladder smooth muscle, presynaptic side in cochlear ribbon synapses, and adrenal chromaffin cells [41,42,44]. CaV2.1 channels are called P-type, as they were first described and are abundant in cerebellar Purkinje neurons, and Q-type, which were initially identified in cerebellar granule cells, and help regulate cerebellar signaling [45]. CaV2.2 channels or N-type (neural type) are involved in neurotransmission in autonomic synapses and sensory synapses conveying nociceptive signals. CaV2.3 channels, known as R-type as they are not only resistant to DHP but mediate Ca2+ currents upon P/Q- and N-type channels block, are found in hippocampal and cortical neurons. The CaV2 channel subfamily is dominantly expressed in presynaptic nerve terminals and mediates coupling of presynaptic membrane depolarization and neurotransmitter release. Furthermore, some CaV2 channels (CaV2.1 and CaV2.2) in neuron somata and dendritic spines [46,47] can associate with Ca2+-activated K+ channels (presented in detail later) to shape AP repolarization and control of neuron firing frequency, by altering K+ conductance, while cooperation of these channels in presynaptic membrane microdomains regulates neurotransmission [48,49]. Lastly, CaV3.1–CaV3.3 channels, known as T-type for their tiny and transient currents, mediate SAN pace-making activity [43,50], but also neurotransmitter release in the retina, olfactory bulbs, hippocampal, and DRG neurons [42]. Orchestrating rebound excitation, CaV3 channels shape oscillatory neuron activity in the cerebellum and thalamocortical circuits as well as in sensory processing [51]. High-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels (CaV1 and CaV2) contain CaVα1-, CaVβ-, and CaVα2δ-subunits, and their activation is achieved at more depolarized membrane potentials, while low-voltage-activated (LVA) Ca2+ channels (CaV3) are built solely of CaVα1-subunits, and they can be activated by depolarizations slightly above the resting membrane potential [41,43]. Channels interact directly or indirectly with various proteins that regulate their function, modulation, and localization within the presynaptic terminal [41]. Long-lasting Ca2+ currents critical for excitation and neuroendocrine regulation are mediated by CaV1.2 channels, while CaV2.1 channels play an essential role in neurotransmitter release. CaV channels possess self-regulatory mechanisms, allowing them to change ion permeation in response to prolonged depolarization and activity or high Ca2+i concentration ([Ca2+]i), namely through voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) and Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI). These actions are a result of the coordinated binding of CaVα1 C-terminal cytoplasmatic isoleucine-glutamine (IQ) domains with a soluble Ca2+ sensor, calmodulin (CaM) already complexed with Ca2+ to induce CDI, or an interaction between the S1–S2 interdomain loop (α1-interacting domain, AID) region with auxiliary CaVβ-subunits to elicit VDI [43,50,52,53]. Another pivotal region for CDI is the Ca2+i-binding CaVα1-subunit’s C-terminus EF-hand motif, a site that is in the vicinity of the IQ domain and is proposed to also mediate in the CaV channel inactivation upon Ca2+-CaM binding [53].

Effects of Mg2+i on CaV Channel

The concentration of Mg2+ can vary in pathophysiological conditions in the brain or skeletal muscle, increase in transient cardiac ischemia, or decrease in heart failure. Increase of [Mg2+]i, in some cases even within physiological concentration range, alters the function of CaV channels, leading to their inhibition. The underlying mechanism of inhibition is multifaceted and can be interpreted as a concomitant effect of Mg2+i on the direct influence on the channel’s ion permeation and Mg2+i-induced modulation of the channel’s gating kinetics.

Extensive electrophysiological studies on isolated murine ventricular cardiomyocytes report on a progressive reduction in peak currents through CaV1.2 channels during application of [Mg2+]i that reaches the higher end of the physiological range and/or supraphysiological values [54,55,56]. Additionally, cardiomyocytes exhibit progressive shortening of AP duration with increasing [Mg2+]i used. These effects could not be abrogated by increasing levels of Ca2+o ([Ca2+]o) [54]. Variations of [Mg2+]i in isolated murine artery myocytes show a dichotomous response, an initial increase in Ca2+-and Ba2+-carrying inward currents through CaV1.2 channels in extremely low [Mg2+]i conditions, presumably due to instant reduction in Mg2+, followed by a progressive attenuation in current amplitude as [Mg2+]i increases [57]. Concentration-dependent inhibitory action of Mg2+i is also shown in human embryonic kidney (HEK) TsA-201 cells expressing rabbit wild-type CaV1.2 channels at fixed membrane potentials. Namely, increasing [Mg2+]i reduces CaV channel-mediated inward currents, an effect reversed by Mg2+i depletion [55,58]. Moreover, the inhibitory action of increasing [Mg2+]i on CaV channel permeation in isolated amphibian cardiac myocytes is also present, albeit more modest than in mammalian myocytes [59,60]. Concentration surpassing the physiological range; however, they elicit a pronounced voltage-dependent blocking effect on CaV channels, augmenting the rate and extent of channel inactivation. Membrane hyperpolarization undermines the Mg2+i-induced CaV block, promoting influx of Ca2+ during the channel activation phase, while depolarizing potentials allow Mg2+i to enter the cytoplasmatic side of the channel pore, hindering Ca2+ currents [61]. Voltage dependence of CaV channel activation and inactivation can be altered at extremely high and low [Mg2+]i, as shown in rabbit CaV1.2-expressing HEK-TsA-201 cells. High [Mg2+]i leads to a negative shift in the voltage dependence of both channel activation and inactivation, while very low [Mg2+]i causes a positive shift in the voltage–conductance relationship of CaV1.2 channels [58]. It is also proposed that the reduction in inward currents mediated by CaV channels can also partially be due to higher [Mg2+]i screening the negative charges on the intracellular membrane surface, thus modulating channel activity [58,61].

Mg2+i can modulate CaV1.2 channel activity by interacting with the putative Ca2+-binding motif of 12 amino acid residues (EF-hand region) on the C-terminal domain in CaVα1-subunit. Multiple studies on Mg2+ binding affinity to CaV channel pore demonstrate that negatively charged amino acid residues of the proximal C-terminal EF-hand motif are the possible binding sites in the Mg2+i-induced blocking cascade, probably competing with Ca2+-CaM complex binding and leading to a partial CaM displacement. Mutant rabbit CaV channels expressed on HEK-TsA-201 cells, where negatively charged Asp is substituted with either a nonpolar alanine (Ala), polar uncharged Asn or Ser, or positively charged lysine (Lys) (D1546A/N/S/K) in position 1546 of the EF-hand motif in CaVα1-subunit, show decreased affinity for Mg2+i. Conversely, exchanging positively charged Lys for negatively charged Asp in position 1453 or 1539 (K1453D, or K1539D) of the same region, significantly increases channel pore affinity to Mg2+i. In comparison to cells expressing wild-type rabbit CaV1.2, channel conductance decline is seen in lower [Mg2+]i in cells carrying mutant K1453D or K1539D CaV EF-hand motifs, while D1546A/N/S/K CaV mutants require a several-fold higher level of cytosolic Mg2+ to elicit the inhibitory action [58].

The interaction between the CaVα1-subunit’s distal C-terminal domain (DCT) and proximal C-terminal domain (PCT) can be autoinhibitory, as it reduces coupling of charge movement to channel opening, thus leading to prominent augmentation of voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 channels. Mg2+i can also modulate the noncovalent bond between DCT and PCT and the voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2-mediated currents. The binding of Mg2+i to the PCT EF-hand motif is necessary for the DCT to exert the autoinhibitory effect [62]. Electrophysiological examination of isolated murine ventricular cardiomyocytes and HEK-TsA-201 cells expressing mutant variants of the channel’s CaVα1-subunits shows that an increase in [Mg2+]i not only reduces peak amplitudes of inward CaV1.2-mediated currents but also increases the rate and the duration of voltage-dependent inactivation of inward currents. Presence of mutant D1546A/N/S/K EF-hand motifs in CaVα1-subunits reduces VDI and Mg2+i-dependent inhibitory effects on CaV1.2 conductance, since only higher [Mg2+]i can elicit the steady state inactivation of the mutant channel compared to the wild-type one. The effect that the EF-hand motif mutation exerts on the rate and extent of VDI arises from the lack of Mg2+i binding affinity for the mutated region of the channel, thus failing to enhance VDI frequency and degree [62]. Elevated [Mg2+]i in amphibian cardiac myocytes also increases the rate and the extent of CaV channel VDI [61].

Earlier experiments on amphibian cardiomyocytes shed light on another mechanism through which Mg2+i can modulate CaV channels’ gating kinetics. Increased Mg2+i levels markedly reduce inward Ca2+ currents through CaV channels when they are phosphorylated [59,60]. On the other hand, some postulate that inhibitory effects on CaV conductance result from modulation of channel gating properties through phosphorylation of channel residues elicited by Mg2+i [63]. Having in mind that Mg2+i can interact with protein kinases and phosphatases to modify their activity [58], the effect that Mg2+i exerts on CaV channels seems dual, as Mg2+i possibly interacts directly with CaV channels, which, in a more phosphorylated state, are more susceptible to Mg2+i inhibitory effect. As with amphibian myocytes, electrophysiological recordings from murine ventricular cardiomyocytes show that rising [Mg2+]i causes a prominent reduction in Ca2+ currents through CaV1.2 channels conditioned to maximal phosphorylation. Changes from the CaV1.2 channel’s maximal phosphorylation state attenuate the inhibitory Mg2+i effect on inward Ca2+ currents, thus giving rise to the possibility that [Mg2+]i can antagonize the effects of phosphorylation on channel gating kinetics [64]. Dialysis of murine ventricular cardiomyocytes with K252a, a protein-kinase inhibitor, diminishes inward Ca2+ current density and any inhibitory effect of Mg2+i on CaV1.2 channel permeation, while phosphorylation of channels mediated by dialyzed cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) requires higher [Mg2+]i to reduce CaV channel conductance [63]. Inhibition of CaV1.2 channel conduction by high [Mg2+]i in isolated murine cardiomyocytes is potentiated by phosphorylation of the channel by protein kinase A (PKA), but application of phosphatase 2A (PP2A) dampens Mg2+i-induced inhibition as CaV channels become dephosphorylated [55]. Many potential phosphorylation sites are found in CaVα1-and CaVβ-subunits of CaV1.2 channels, and the most important ones for PKA-mediated phosphorylation are Ser residues at position 1928 (S1928) in α1C-subunit and positions 478 and 479 (S478 and S479, respectively), of β2A-subunits [65]. Recordings from HEK-TsA-201 cells expressing mutated rabbit CaV1.2 channels corroborate the significance of the channel’s phosphorylation state and sensitivity to Mg2+i-induced decrease in channel conduction. Namely, inward Ca2+ currents through mutant CaV1.2 channels lacking PKA phosphorylation sites are minutely affected by increasing [Mg2+]i, which is comparable to that of PP2A application in cells carrying wild-type channels. Conversely, truncation of the channel’s α1-subunit to increase channel pore open probability leads to a strong inhibition of inward currents through mutated channels when [Mg2+]i is high, comparable to blocking effects seen in dephosphorylated channels under the influence of dihydropyridine agonist BayK8644, which promotes channel pore opening [55,56]. Interestingly, increasing [Ca2+]i also has the capacity to dampen Mg2+i-induced inhibitory effects regardless of the channel phosphorylation status, indicating that, other than counteracting the CaV channel phosphorylation effects and gating kinetics, Mg2+i probably has a direct blocking effect on channel ion permeation [64].

While existing studies clarify the intricate mechanisms behind Mg2+i regulation of CaV1 channels, comparable direct channel-specific processes for other CaV channel subtypes, to the best of our knowledge, have not been reported.

Effects of Mg2+o on CaV Channels

While Mg2+i is considered to have an intricate effect on CaV channel conductance, aimed towards complex channel blocking and modulating channel activity, Mg2+o is considered to have the ability to directly block CaV channels. Early electrophysiological works on murine ventricular cardiomyocytes revealed that increasing [Mg2+]o transformed long-lasting single channel currents into bursts of brief openings, due to CaV channels’ discrete and rapid blocking and unblocking transitions. Channel blocking rate accelerates with increasing [Mg2+]o, and hyperpolarizing membrane potentials expedite channel opening and closing transitions as well. This gave rise to the idea that Mg2+o can lodge within the CaV channel pore and block the channel [66].

Mg2+o-induced blocking action is voltage-dependent. Hyperpolarization of membrane potential increases the degree of Mg2+o-induced steady state block of CaV channels [66]. Mg2+o can block CaV channels quite rapidly in isolated amphibian ventricular myocytes, but has little effect on channel inactivation kinetics [61]. Voltage-clamp experiments on isolated snail neurons and Na+ currents through CaV channels led to a suggestion that these channels have two functional regions–an external region where divalent cations bind with high-affinity to determine channel permeability to currents carried by monovalent cations, and the ion-selective filter that determines channel selectivity for different divalent cations [67].

Experiments on chick dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons exhibit a voltage-dependent block of CaV channels (L-and N-type) elicited by Mg2+o as inward Ca2+ and more prominently Na+ currents are reduced, respectively, to increasing [Mg2+]o. Inhibitory effect on inward currents is dominant at hyperpolarizing membrane potentials, and as the membrane becomes more positive, the blocking action declines. Upon cessation of depolarization and returning to negative membrane potentials, CaV channels are readily blocked again [68]. Given the potential clinical and experimental importance of Mg2+o in the hippocampus, the cellular and molecular bases for non-physiological excitability of hippocampal neurons induced by Mg2+ deficiency are of great practical interest. Electrophysiological findings of Mg2+o-induced CaV channel block are confirmed by visual observations of fluorescent probes in isolated murine hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Increase in Ca2+i-induced fluorescence in response to low [Mg2+]o, corresponds to increased inward Ca2+ currents through CaV channels upon removal of the Mg2+ block. Findings that intracellular fluorescence dissipates when [Mg2+]o increases or when CaV1.2 channel blockers are used further prove the blocking action of Mg2+o surrounding the neurons. Interestingly, Mg2+i levels do not significantly change in response to varying [Mg2+]o. It is proposed that Mg2+o modulates CaV channels and inward currents traversing the channel pore [69].

Equivalent concentration-dependent effects of Mg2+o are observed in recordings of rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells, possessing characteristics of peripheral sympathetic nerves. Increasing [Mg2+]o elicits progressive attenuation of inward currents through N-and L-type CaV channels [70]. Patch clamp recordings of isolated murine mesenteric artery myocytes show that increasing concentrations of Mg2+o elicit progressive reduction in Ca2+-and Ba2+-carried inward currents through CaV1.2 channels, with Ba2+ currents being more affected [57].

Apart from the blocking action on CaV channel conductance, high [Mg2+o] elicits surface charge screening near the mouth of the channel pore and a voltage shift in its gating kinetics [61,68]. As Mg2+o binds to the negatively charged Glu or Asp residues in the extracellular loop of the pore-forming α1-subunit, this reduces the effective voltage sensed by the VSD and shifts the voltage dependence of activation toward more positive potentials. This effect can decrease the amplitude of the Ca2+ current through CaV channels, in addition to elevating the voltage for channel activation [44,57]. Positive divalent cations can accumulate and “screen” or neutralize the negative charge of the cell surface.

2.1.3. Mg2+ Effects on Voltage-Gated Sodium (NaV) Channels

The NaV channels are critical for initiating and propagating APs in neurons, playing a pivotal role in neuronal excitability and signal transmission. These channels are composed of an NaVα-subunit with four homologous domains (I–IV), each with six TM segments (S1–S6), where S4 segment, being rich in positively charged amino acids, acts as a VSD, while S5–S6 segments with their connecting pore loop (p-loop) build the ion-conducting pore with an inactivation gate made out of regions that link III and IV domain. Auxiliary NaVβ-subunits (NaVβ1–NaVβ4) compete with each other (NaVβ1 v. NaVβ3 or NaVβ2 v. NaVβ4) for association with the NaVα-subunit. Although not obligatory for NaV channel function, they attune the activity of the NaVα-subunit to modulate channel kinetics, voltage sensitivity, and sensitivity to other ligands [50,71]. NaV1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.6 channels are primarily expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), NaV1.7, 1.8, and 1.9 channels in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) at nociceptors, while NaV1.4 and NaV1.5 channels are the primary NaV channels in the skeletal muscles and the heart, respectively [50,72]. The channels open in response to membrane depolarization, allowing the influx of Na+ ions.

Effects of Mg2+i on NaV Channels

Electrophysiological experiments performed on murine cerebellar granule cells show that Mg2+i can elicit a voltage-dependent block of NaV channels by binding to the channel pore selectivity filter. During membrane depolarization, Mg2+i ions enter the NaV channel pore several times, reducing inward Na+ currents by half at depolarizing potential. Increase in [Mg2+]i augments the blocking effect of Mg2+i on NaV channels, while Mg2+i-induced inhibition of Na+ currents is reversed by an increase in Na+i concentration ([Na+]i) or Na+o concentration ([Na+]o), unveiling a competitive nature of this blocking effect. It is estimated that the presence of Mg2+ in the channel pore interferes with Na+ flux in both directions. Increase in [Mg2+]i from 0 to 30 mmol/L elicits negative V1/2 shifts in the range of −25 mV to −29 mV, although the voltage dependence of channel activation and inactivation does not change with [Mg2+]i increase [73]. Experimental recordings from Xenopus oocytes expressing rat brain type II Na+ channels [74,75], mutant K226Q NaV channels (Lys 226 substituted with Gln), type III Na+ channels, and neuron-like Na+ channels in chromaffin cells [75] demonstrate that Mg2+i markedly reduces Na+ currents through tested channels in a voltage- and concentration-dependent manner. Blocking effects become more prominent at more positive membrane potentials and with increasing [Mg2+]i in the patching pipette [75]. Examining the effects of Mg2+i on mutant cZ-2 Na+ channels known to exhibit slow and incomplete inactivation after opening demonstrates that increasing [Mg2+]i elicits a reduction in Na+ single-channel current amplitude. Since Mg2+i ions act as fast blockers, closing the Na+ channel pore completely for short time periods, they generate a flickery blocking action. Conversely, the blocking effect of Mg2+i on rat brain type II Na+ channels is augmented with an increase in [Na+]i. As Mg2+i is coupled to ATP–ADP hydrolysis, this balances the energy in the cell, so that a higher energy consumption leads to an increase in [Mg2+]i that modifies NaV channels to decrease in Na+ conductance and attenuate AP firing [75].

Mg2+i can modulate NaV channel activity through channel phosphorylation. Mg2+ is crucial for the function of PKA, an enzyme responsible for phosphorylation of NaV1.1 and NaV1.2 channels’ Ser residues in the NaVα-subunit’s intracellular loop, leading to the reduction in Na+ channel activity and conductance. High [Mg2+]i (10 mmol/L) can conversely lead to a decrease in PKA activity [72,76,77].

It is highly debatable whether high [Mg2+]i (30 mmol/L) elicits a negative shift in the NaV channel’s voltage dependence due to cytoplasmatic membrane surface potential change [73], since there is a relatively low half maximal inhibitory [Mg2+]i (4 mmol/L) compared to high blocking [Mg2+]o (35 mmol/L) that reduces inward Na+ channel conductance [74].

Effects of Mg2+o on NaV Channels

Electrophysiological examination of Mg2+o effects on murine hippocampal neurons presents a concentration-dependent increase in AP thresholds, resulting in decreased excitability. Higher [Mg2+]o (10 mmol/L) also reduces peak AP amplitude. As this action is comparable to the effect of tetrodotoxin (TTX), a highly selective antagonist of NaV channels, it is assumed that an increase in [Mg2+]o leads to a decreased availability and activation of NaV channels. Surface charge on the cell membrane created by sialic acid, phosphates, charged lipids, charged amino acids, and additional hydrophilic channel protein residues elicits local electrical fields near the channel voltage sensor [78]. However, some of the effects of Mg2+o on AP threshold and neuronal excitability are considered to result from surface charge screening, a process where extracellular cations bind to negative charges on the membrane, reduce surface potential, and produce local hyperpolarizing conditions for VSDs of Na+ channels. This charge screening effect is recognized as a depolarizing shift in Na+ voltage-dependent channel activation and inactivation [79]. Similar findings are seen in acutely isolated hippocampal CA1 neurons, as Mg2+o elicits a concentration-dependent reduction in NaV channel conductance. Moreover, exposing the cells to a fixed [Mg2+]o at different holding membrane potentials elicits a progressive reduction in Na+ current amplitude, indicating the voltage-dependence of Mg2+o-induced channel block [80]. NaV channel activity in murine hippocampal slices is susceptible to a concentration-dependent block by Mg2+o, as a decrease in NaV-mediated Na+ current amplitude is evident in high [Mg2+]o. On the other hand, exposing neurons to Mg2+o-free solution facilitates channel activation and leads to an increase in Na+ current amplitude [81]. In addition, studies on isolated murine saphenous nerves confirm that Mg2+o acts in a similar manner to TTX, via a concentration-dependent decrease in Na+ currents through NaV1.6 channels in Aβ fibers [82]. Altering the gating properties of the NaV channel leads to AP threshold shift, spontaneous synaptic activity, ectopic neuronal charges, and epileptic activity in in vitro and in vivo models.

Depolarization of the resting membrane potential by Mg2+o followed by decreased excitability of neurons seems contradictory. To explain this effect, a relatively novel hypothesis suggests that Mg2+o may induce subthreshold depolarization by quantum tunneling through closed NaV1.2 channels. Namely, it was calculated that at a concentration of 5.5 mmol/L Mg2+o passes through the channel and its intracellular hydrophobic gate, by acquiring the kinetic energy from neuronal membrane voltage and the thermal body energy, thus eliciting minor membrane depolarization by 5 mV. Unlike Mg2+o, Mg2+i has a lower tunneling probability, since they have lower kinetic energy. The degree of neuronal membrane depolarization by Mg2+o is determined by the tunneling probability, Na+ channel density in the membrane, and [Mg2+]o [83].

2.1.4. Mg2+ Effects on Large Conductance Ca2+-Activated Potassium (BK) Channels

BK channels have a large single-channel conductance. Activated by membrane voltage depolarization, micromolar [Ca2+]i, millimolar [Mg2+]i, or other ligands, BK channels mediate substantial K+ efflux and elicit repolarization of the membrane and/or closure of CaV channels to reduce Ca2+ influx. Assuming the role of a negative feedback to membrane depolarization and elevated [Ca2+]i, these channels regulate membrane excitability, intracellular ion homeostasis, and Ca2+ signaling, as they are often colocalized with CaV channels, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) [84,85]. BK channels are expressed in skeletal and smooth muscles, neuron soma, axons, and presynaptic dendrite terminals, cochlear inner hair cells, and chromaffin cells, thus playing an important role in muscle contraction, neurotransmission, control of neuronal excitability (control of interspike interval and spike frequency adaptation), tuning hair cell firing, and hormone secretion. Native BK channels comprise α-subunits or a combination of α- and β-subunits (β1, β2/3, β4) or γ-subunits (γ1–γ4) in homotetrameric form [86,87]. Channels assembled from α-and β1-subunits are found in smooth muscle cells; ones made up of α-and β2/3-subunits exist in the brain, heart, and kidneys [86], while channels containing α-and β4-subunits are most abundant in the brain and spinal cord [87]. On the other hand, channels composed of α- and γ3-subunits are selectively expressed in the brain, while those built from α-and γ1-subunits are expressed in smooth muscle cells of cerebral arteries [87]. Each of the four α-subunits (Slo1 proteins) contains seven TM segments (S0–S6), including an additional S0 transmembrane segment that carries the N-terminus to the extracellular side and interacts with β-subunits, the pore–gate domain (PGD, S5–S6) with the C-linker (between S6 C-terminus and S7 N-terminus), which acts as an activation gate, and the voltage-sensing domain (VSD, S1–S4), whose positively charged Asp residues in the S4 helix represent a primary voltage sensor moving outward in response to membrane depolarization [88,89]. Furthermore, a large CTD or tail domain with four additional hydrophobic segments (S7–S10) is divided into two parts, homologous to a regulator of K+ conductance (RCK domains)–RCK1 (S7–S8) and RCK2 (S9–S10) [90] and serves as a primary ligand sensor [85]. RCK domains carry high-affinity Ca2+-binding sites–one on the RCK1 domain and one on the RCK2 domain (Ca2+ bowl), while the interface between the VSD and the cytoplasmatic domain and the RCK1 domain can be a target for Mg2+ binding [88]. BK channels owe their diversity to alternative splicing of Slo1 mRNA and accessory β subunits, which modify pharmacology, voltage dependence, and channel kinetics [86,88]. The VSD senses voltage, and the cytoplasmatic domain senses intracellular ligands, and they both allosterically control K+ efflux through PGD in response to various stimuli, linking cellular metabolism and membrane excitability [84]. As Mg2+i is one of the ligands that modulates the activity of BK channels, we will mostly focus on its effects.

Effects of Mg2+i on BK Channels

Early experiments on planar lipid bilayers with incorporated murine muscle transverse tubule membrane [91,92] or parotid acinar cell membrane [93] fragments or on cultured hippocampal neurons [94] show that Mg2+i acts like an allosteric BK channel stimulator, increasing the channel open probability [91,92,93], the affinity of the channel for Ca2+i [91,92] and channel activation [93] in a concentration-dependent manner. Mg2+i is suggested to bind to channel’s modulatory sites on its cytoplasmic side distinct from Ca2+-binding sites, as either physiological [Mg2+]i (1 μmol/L to 1 mmol/L) or high [Mg2+]i (10 mmol/L) at constant [Ca2+]i increase in the cooperativity of channel Ca2+ activation, with a two-fold increase in the Hill coefficient for Ca2+i-induced channel activation curve [93]. Interestingly, in the absence of Ca2+i, Mg2+i fails to activate the channel [91,93,94], even at extremely high [Mg2+]i of 50 mmol/L [92]. Increasing [Mg2+]i when Ca2+i is significantly reduced recovers channel open probability and single-channel current amplitude, with Mg2+i achieving almost the same efficacy as Ca2+i [94]. These findings indicate that Mg2+i is a potential internal modulator of BK channels in Ca2+i-dependent regulation of neuronal excitability.

Electrophysiological studies on cultured murine skeletal muscle cells [95], cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells [96], rabbit pulmonary artery [97], portal vein and coronary artery [98] smooth muscle cells, phospholipid bilayers containing rabbit colonocyte membrane fragments [99] or Xenopus oocytes expressing wild-type [100,101,102,103,104] or mutant mouse Slo1 (mSlo1) BK channels [105] show that Mg2+i can decrease channel outward K+ current amplitude and conductance in a concentration-dependent and voltage-dependent manner, acting as a fast blocker. The magnitude of Mg2+i-induced blocking action can be attenuated by [K+]i increase [95,99]. Interestingly, certain millimolar [Mg2+]i can, however, enhance channel open probability independently of membrane potential [96,98,100,101]. Patch-clamp recordings of macroscopic currents on oocytes expressing mSlo1 channel corroborate earlier findings, but also demonstrate that, at positive membrane voltage, Mg2+i reduces outward current amplitude regardless of [Ca2+]i, while negative membrane potential relieves channels from Mg2+i block [100]. Furthermore, Mg2+i can block mutant channels lacking CTD Ca2+-binding sites, but it does not affect channel activation. It is also proposed that channel sites involved in Mg2+-dependent channel activation are distinct from the ones mediating the previously described Mg2+ block [100].

Mg2+i competes with Ca2+i for BK channel low-affinity metal-binding sites (Mg2+-or Mg2+/Ca2+-binding sites). This competition is more evident in the presence of millimolar [Ca2+]i, which, being higher than physiological levels by three orders of magnitude, activates channels not only by occupying their high-affinity Ca2+-binding sites, but also by competitive binding to low-affinity metal-binding ones [100]. Moreover, low-affinity binding sites exhibit greater affinity for millimolar [Ca2+]i than for millimolar [Mg2+]i, indicating that, at high concentrations, Ca2+i and Mg2+i can use these binding sites to modulate channel-gating kinetics [101]. In contrast, apart from binding to the Mg2+-binding site, which activates the channel, Mg2+i can bind to the high-affinity Ca2+-binding site, without any effect, competitively inhibiting Ca2+-dependent activation [100,102]. As [Ca2+]i increases, Mg2+i binding to high-affinity Ca2+-binding sites declines, but when [Mg2+]i reaches supraphysiological levels, this inhibition is preserved [100,102]. Further electrophysiological examination on Xenopus oocytes expressing mSlo1 channels demonstrates that millimolar [Mg2+]i added to saturation micromolar [Ca2+]i (~110 μmol/L) enhances Ca2+i-triggered channel activation by interacting with low-affinity Mg2+-binding site [101]. However, it is debatable whether Mg2+i can activate BK channels by binding to the high-affinity Ca2+-binding site and substituting Ca2+i, and if this activation can occur in Ca2+i-free conditions [91,92,93,94,100,101]. Since Mg2+i causes a shift in channel gating as a result of channel closure retardation, rather than fast channel opening, Mg2+i effects are considered to be dependent on the channel open conformation [100,101]. Activation of BK channels by Ca2+i is probably potentiated by Mg2+i through channel allosteric modulation, as Mg2+i binding to low-affinity sites allosterically regulates channel open conformation, independently of Ca2+i binding to high-affinity binding sites and voltage sensor movement to membrane depolarization [101]. The binding of Ca2+i to the high-affinity binding sites, along with membrane depolarization, opens the channel, while Mg2+i bound to the low-affinity binding site potentiates channel activation.

In order to modulate BK channel activity, Mg2+i needs to simultaneously bind to several amino acid residues within the channel, prompting interdomain and intersubunit interactions. Studies on oocytes expressing mutant mSlo1 channel constructs reveal that the position 397 Gln oxygen-containing carbonyl group (Q397) coordinates Mg2+i ability to bind to Glu residues in 374 (E374) and 399 (E399) positions in the RCK1 domain [106,107]. Exchanging Gln with cysteine (Cys) in position 397 (Q397C) reduces the sensitivity of this mutant channel to Mg2+i both at zero and saturation [Ca2+]i, but it does not abolish it [106,107] and has no effect on the mutant channel conductance-voltage (G–V) relation [108]. Other mutant mSlo1 channel variants with Gln being replaced by arginine (Arg), Lys or tryptophan (Trp) (Q397R/K/W, respectively), exhibit decreased in Mg2+i sensitivity, but substitution with Glu (Q397E) or Asp (Q397D) enhances Mg2+i sensing, possibly due to the electrostatic attraction of negatively charged amino acid residues to bound Mg2+ [107,109] and shifts the channel G–V relation to more positive voltages [108]. Since Q397 is close to Mg2+i-binding sites E374 and E399, its mutation affects the channel’s Mg2+i sensitivity and binding affinity due to conformational changes in the binding sites or by an electrostatic interaction with already bound Mg2+ [107]. Interestingly, adding positive charge to this site, by substitution with Lys (Q397K) or Arg (Q397R) activates the mSlo1 mutant channel in absence of Mg2+i and shifts the G–V relation to more negative voltage, suggesting that the positively charged residue mimics Mg2+i bound to nearby sites (E374 and E399) and can electrostatically interact with positively charged Arg (R213) of the channel VSD [108]. Mutant Q397K or Q397R channels enhance the voltage sensor activation and mobility only when the channels are in the open state, similarly to wild-type channels upon Mg2+i binding [108]. Subsequent work on oocytes expressing several mutant channel variants reveals two additional Mg2+i-binding sites–a negatively charged, oxygen-bearing Asp residue in position 99 (D99) and a polar, uncharged Asn residue in position 172 (N172) in the α-subunit VSD, in addition to E374 and E399 in the RCK1 domain. Exchanging Asp in position 99 with nonpolar Ala (D99A) in the VSD makes the mutant channel not only resistant to Mg2+i but can abolish Mg2+i binding to E374 and E399 sites in the RCK1 domain. Furthermore, mutant channels where Asp is substituted by amino acids lacking oxygen in their side chain, such as Cys, Trp, Arg, or Lys (D99C/W/R/K, respectively), lose Mg2+ sensing as well. Conversely, Mg2+i can still exert its activating effect on a channel with preserved side chain oxygen, namely when Asp is interchanged with Gln, Asn, or Glu (D99Q/N/E, respectively) [109]. BK channels with a mutation of the other binding site, namely Asn replacement with Ala in position 172 (N172A), show a substantial decline of channel responsiveness to Mg2+i, whereas substitution with Arg (N172R) or Lys (N172K) abolishes Mg2+ sensitivity of the channel. Having a negatively charged Glu or Asp residue instead of Asn (N172D or N172E, respectively) enhances the mutant’s binding site interaction with Mg2+i [109]. Double mutant channels bearing Cys instead of Asp in position 99 and Gln in position 397 (D99C:Q397C) show that the VSD and RCK1 domains are close enough that a disulfide bond forms between their cysteine residues. This proves that the spatial proximity between D99 in VSD and E374 and E399 in the RCK1 domain fits the dimensions of a Mg2+-binding site [109]. Furthermore, double mutant channels comprising N172D substitution with either D99A, E374A, or E399N exhibit considerably stronger sensitivity to Mg2+i than those carrying single mutations, indicating that the Asp carboxylate group oxygen in position 172 rescues the channel’s ability to bind Mg2+i [109]. Experimental findings propose that Mg2+i binds to a complex site that consists of Asp residues at position 99 (D99) and Asn residues in position 172 (N127) in the VSD of one α-subunit and Glu residues at positions 374 (E374) and 399 (E399) in the RCK1 domain of a neighboring α-subunit, mediating an intersubunit interaction between the voltage-sensing and ligand-sensing domains [109]. This allows for the activation of the channel by electrostatic interaction between bound Mg2+i and the positively charged Arg (R213) residue of the VSD in the S4 segment [109]. Mutant mSlo1 channels with only preserved low-affinity Mg2+-binding site open to an increasing membrane voltage after a markedly shorter latency period in the presence of Mg2+i and a decrease in the interval duration of the channel closed state. Furthermore, Mg2+i prolongs bursts of channel openings with a higher channel opening rate, while the mean open interval duration increases in 2-fold compared to zero [Mg2+]i conditions. Mg2+i can bind to closed channels, while increasing the probability of channel opening, but is more efficient in binding to open channels, decreasing the probability of channel closing and closing rates [105].

Movement of the voltage sensor in response to membrane voltage change [108,110] generates a transient gating current (Ig) [108]. Whereas having no effect on the IgON, caused by voltage sensor movement from the resting to the activated state, when most channels are closed, Mg2+i slows down the return of the voltage sensor from the activated to the resting state, when most channels are open, and decreases the amplitude of the generated IgOFF [108]. Mutant channels where Asp is exchanged with Ala in position 99 (D99A) or position Glu is replaced with Asn in position 399 (E399N) become resilient to Mg2+i effect on IgOFF [109]. The transmembrane S4 segment is not only the primary voltage sensor that leads to the opening of the channel, but also the C-linker activation gate [110] but also mediates Mg2+i-dependent channel activation cascade. Channels carrying mutations of the VSD in the S4 segment, namely position 213 Arg substitution with polar uncharged Gln (R213Q) [110] or Cys (R213C) [108] have altered voltage dependence and lose sensitivity to Mg2+i and Mg2+i-dependent activation [108,110]. Time course of wild-type channel deactivation in the presence of Mg2+i is slower than in zero [Mg2+]i, but the R213Q mutant becomes unaffected by changes in [Mg2+]i [110]. It is shown that Mg2+i bound to E374 and E399 in the cytoplasmatic RCK1 domain can come close to the VSD in the S4 segment and electrostatically interact with the VSD positively charged R213 site, which is important for voltage sensing. The created electrical field at R213 and the repulsion of positive charges promote activation of the voltage sensor and favor the channel open state. It is proposed that VSD senses not only membrane voltage but also the bound Mg2+i. Therefore, the R213 residue acts both as a membrane voltage sensor and Mg2+i binding sensor, so that VSD can control channel activation [108]. Excitatory Mg2+i effect on BK channels requires activation of the channel voltage sensor. Substitution of Arg in position 210 with Cys leads to a constitutively active voltage sensor in the mutant channel, which can be opened by Mg2+i regardless of the membrane voltage. In addition, the channel’s open probability increases with increasing [Mg2+]i when they are activated [104,105]. However, it is possible that high [Mg2+]i (10–100 mmol/L) elicits a direct effect on channel opening independently of voltage sensor activation, similarly to that of Ca2+i, through an additional low-affinity binding site [104]. Mg2+i strengthens the coupling of voltage sensor activation and channel opening by interacting with multiple sites on the voltage sensor [104].

BK channel reactivity to Mg2+i is also affected by α-subunit mutations in the C-terminal half of the S4 segment and the N-terminal part of the S4–S5 linker. Specifically, mutant channels where Gln in position 216 or 222 is replaced with Arg (Q216R or Q222R, respectively), Glu in position 219 substituted with Gln (E219Q), leucine (Leu) in position 224 exchanged with Arg (L224Q) or channels bearing double mutation at positions 219 and 222 (E219R/Q222R) have a suppressed sensitivity to Mg2+i, albeit some of the positions in wild type channels do not directly participate in Mg2+i binding. These findings suggest that interactions between amino acid residues in the C-terminal part of S4 and the N-terminal part of S4–S5 linker with adjacent voltage-sensing moieties are crucial for Mg2+i-dependent channel activation [110]. Moreover, the interaction between the RCK1 domain and the voltage sensor conveys the energy from Mg2+i binding to open the channel gate [110]. Electrophysiological experiments on oocytes expressing wild-type mSlo1 channels propose that a ring composed of eight negatively charged Glu residues in positions 321 and 324 at the cytosolic channel entrance might be a possible target for Mg2+i blocking action. Moreover, mutant channels without the ring structure, stemming from Glu substitution with polar uncharged Asn (E321N:E324N), exhibit a significant resistance to Mg2+i-induced blocking action [103]. Substantial [K+]i increase equally mitigates Mg2+i block of wild type and mutant channels, suggesting that, when present, the ring of negative charge cannot facilitate blocking action in high [K+]i as it loses electrostatic attraction for Mg2+i and that there might be an additional site of Mg2+i action as the block is not abolished [103]. Namely, not only is Mg2+i attracted to the inner opening of the BK channel, making it easier to block K+ currents, but the screening of the negative charge by Mg2+i decreases in the polar attraction of the channel opening for cytosolic K+ and the outward current [103].

Effects of Mg2+o on BK Channels

Studies examining the effects of [Mg2+]o change on BK channel activity are scarce, as most studies investigate Mg2+i. Earlier electrophysiological experiments on murine muscle transverse tubule membranes incorporated into planar lipid bilayers indicate that high [Mg2+]o exerts no effect on BK channel activation or channel affinity to Ca2+ [91,92]. Subsequent studies on colonocyte membrane fragments incorporated into phospholipid bilayers; however, show that Mg2+o decreases in the channel outward current amplitude and channel conductance altogether in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that this might be a result of electrostatic screening of negative charges located at the channel’s extracellular pore opening [99,111].

2.1.5. Mg2+ Effects on Small Conductance Ca2+-Activated Potassium (SK) Channels

The SK channels are responsible for the medium membrane afterhyperpolarization (AHP) following APs, thus modulating intrinsic neuronal excitability and controlling spike firing rates and AP frequency, regulating dendritic excitability [112]. These channels are built as homotetramers of α subunits composed of six TM segments (S1–S6), with the PGD (S5–S6) surrounded by S1–S4 TM segments. Unlike BK channels, SK channels are voltage-insensitive and activate in response to low [Ca2+]i interacting with their CaM-binding domain (CaMBD). Each subunit binds one CaM through an interaction between the CaM C-lobe with the CaMBD independently of Ca2+i and between the CaM N-lobe and S4–S5 linker. In response to Ca2+i, the S4–S5 linker elicits a set of conformational changes, causing the S6 TM segment to move and open the channel pore for K+ efflux. SK channels are primarily expressed in the CNS, PNS, and the cardiovascular system [89]. Activation of SK channels in substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, and cerebellar dopaminergic (DA) neurons to counteract CaV channel-or NMDAR-mediated Ca2+ influx and membrane excitation regulates muscle coordination and movement [113,114]. SK1 channels are expressed in the neocortex and co-expressed with SK2 channels in the hippocampus, thalamus, cerebellum, and brain stem, while SK3 channels are expressed in the midbrain and the cerebellum [89]. They are usually activated by Ca2+ influx through CaV channels during AP. SK channels couple their activity with postsynaptic modulators of [Ca2+]i, like NMDARs, in dendritic spines of neurons in the hippocampus and amygdala. They are involved in the regulation of the excitatory postsynaptic potential and can influence NMDAR activation through voltage-dependent Mg2+ block, affecting synaptic plasticity [115]. Inhibition of dendritic SK channels leads to long-term potentiation (LTP) and has an important role in memory and learning [116,117]. In cardiac atria and ventricles, SK channels act as an important negative feedback mechanism to [Ca2+]i increase through CaV1 channel activation or Ca2+ release from cellular storage, and lead to repolarization of cardiomyocytes and AP completion [118]. Interestingly, the evidence of direct Mg2+i effect on the function and gating kinetics of SK channels is scarce, while there are still no studies showing the effects of Mg2+o.

Patch-clamp recordings of Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned rat SK2 (rSK2) channels [119,120] or freshly isolated murine aorta endothelial cells [121] show that increasing [Mg2+]i within the physiological range reduces outward K+ channel currents [119,120,121]. Supraphysiological [Mg2+]i (up to 10 mmol/L) blocks the channel completely. Depolarizing shifts in membrane voltage enhance Mg2+i blocking action as if Mg2+i are pushed into the channel. Furthermore, increasing [Mg2+]i leads to inward rectification of the channel current-voltage (I–V) relation in a voltage-dependent manner [119,121]. Conversely, SK channel block elicited by high [Mg2+]i is attenuated with increasing [Ca2+]i, while a decrease of [K+]o potentiates the blocking effect and reduces its voltage-dependency [119]. Explaining the mechanisms of SK channel behavior in these conditions leads to the conclusion that they act similarly to Kir channels, so they can be referred to as “Ca2+-activated inward rectifier K+ channels” [119]. Electrophysiological studies on oocytes expressing mutant rSK2 channels were used to examine possible metal-binding sites in the channel pore-forming region that can mediate the Mg2+-induced block [120]. Mutant rSK2 channels where Ala substitutes Trp in position 379 (T379A), 398 (T398A), or Cys in position 386 (C386A) exhibit a comparable degree of channel block by divalent cations to that of wild-type channels. Conversely, replacement of Ser in position 359 with Ala (S359A) decreases the mutant channel susceptibility to any blocking action, proving that this is the intended site for direct interaction with Mg2+, among other divalent cations, and that it determines channel ionic selectivity. Mg2+i binding affinity to the S359A mutant rSK2 channel increases at lower positive membrane voltages [120]. Knowing that the activity of these channels is coupled with Ca2+i balance modulated by CaV channel, NMDAR, and nAChR activity, it is plausible that Mg2+i and Mg2+o can also indirectly affect SK channel gating kinetics by altering [Ca2+]i.

2.2. Ligand-Gated Ion Channels Regulated by Mg2+

Ligand-gated ion channels are oligomeric protein structures that convert a chemical signal into an ionic current flux through the central pore of the channel. They are involved in crucial signal transduction in the CNS and PNS. The canonical activation pathway of these channels starts with chemical messenger activation, i.e., ligand binding, conformational change, and restructuring of the channel’s integral protein components, opening of the channel pore, and ion flux across the membrane that alters the cell’s membrane potential and ends with a cellular response. The channel pore is permeable to cations such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ or anions such as Cl−, with certain selectivity determined by ion size and charge. Here we present the findings concerning Mg2+ effects on several ligand-gated ion channels of ionotropic receptors, cationic channels of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptor and purinergic P2X receptors, Cl− ion channel of type A receptor for gamma-Amino Butyric Acid (GABAAR), and cationic channel of the nicotinic cholinergic receptors (nAChR). There are a few studies demonstrating the effects Mg2+ exerts on GABAAR and nAChR function. We present their findings in two short overviews.

2.2.1. Mg2+ Effects on N-Methyl-D-aspartate Receptors (NMDARs)

The NMDARs belong to a family of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) known for their essential contribution to excitatory synaptic plasticity and long-term signaling in the CNS. These are heterotetrametric structures composed of two GluN1 subunits and two of four types (A–D) of GluN2 subunits or two types (A–B) of GluN3 subunits. Each receptor subunit contains an extracellular amino-terminal domain (ATD), an extracellular agonist-or ligand-binding domain (LBD), three TM regions (TM1, TM3, and TM4), a re-entrant p-loop (M2 region) with a pore-lining segment and a selectivity filter, and an intracellular C-terminal domain [122,123]. Mg2+ plays a pivotal role in modulating NMDAR activity. Activation of the NMDAR is unique as it requires two signaling factors–Gly binding to a site on the GluN1 subunit and the agonist (NMDA, Glu, Asp) binding to a site on the GluN2 subunit in coordination with depolarization-dependent removal of Mg2+ from its binding site on the GluN2 subunit. Most excitatory synapses function as a result of AMPA (α-amino3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid) and NMDA receptor interplay, and the resulting excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSC) reflect this heterogeneity. Upon membrane voltage change stimulus, AMPA receptor (AMPAR) currents rise and subside fast, as they determine the onset and maximal amplitude of the EPSC, while NMDAR currents rise and decline more slowly, setting the decay of the EPSC and strongly influencing total positive charge entering the cell [124].

Effects of Mg2+i on NMDARs

Mg2+i can block NMDAR channels, and this blocking effect has yet to be explained for its physiological function. Electrophysiological examination of inside-out patches from oocytes expressing NMDAR GluN1 and GluN2A subunits shows that increasing [Mg2+]i in Ca2+o-free solution at positive membrane potentials reduces outward currents through the NMDAR channel. However, at more negative membrane potentials, blocking of inwardly directed currents by Mg2+i is stronger [125]. Mg2+i produces only slight inhibition of inward currents in CA1 neurons at negative potentials but has substantial blocking activity on outward currents at positive membrane potentials. The blocking effect of Mg2+i is more pronounced in conditions lacking Mg2+o [126]. Experiments on outside-out patches of neuronal membranes show that physiological [Mg2+]i can rapidly block the NMDA-activated channel, as it reduces the channel’s current amplitude at positive membrane potentials, without any flickering. This effect, which is augmented with increasing [Mg2+]i, is reversible and not detectable at negative membrane potentials [127,128,129]. The absence of the flickering activity during electrophysiological recording of cultured murine cortical neurons was hypothesized to be due to Mg2+i association and dissociation rates that are so high that the discrete open and blocked states cannot be discerned with signal filtering. The blocking rate constants increase with rising [Mg2+]i and membrane depolarization [129].

In contrast to Mg2+o eliciting channel blocking action by binding to Asn residues of GluN2 subunit, the blocking action of Mg2+i is primarily the result of an interaction with Asn residues in the channel’s GluN1 subunit. Mutant NMDAR expressed on oocytes where GluN1 subunit’s Asn is position 598 is exchanged with nonpolar Gly (N598G) or polar uncharged Gln (N598Q) or Ser (N598S) attenuates the Mg2+i-elicited channel block [125,130,131], while substitution with Asp (N598D) enhances the blocking action due to the negatively charged Asp residue. Asn residues of both GluN subunits form a narrow constriction of the channel pore and represent binding sites for Mg2+i, although GluN1 is the dominant binding site [125,131].

In addition to the binding site for Mg2+o and blockage deep in the pore (~0.64 through the electric field of the membrane from the extracellular side) [127,132], NMDAR channel possesses a divalent cation binding site near the external mouth of the pore (~0.2 through the electric field), to which Mg2+ binds slowly [133]. The difference in the channel’s blocking activity by Mg2+i and Mg2+o [127,130], as well as the markedly faster unblocking rate constants of Mg2+i at physiological voltage [128], suggest that Mg2+i and Mg2+o bind at different sites within the channel pore.