Abstract

This review examines the safety and clinical efficacy of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs)-based therapies in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). The analysis covers 26 clinical studies conducted on patients with varying degrees of the post-SCI neurological deficit. The review highlights the methodology of trials, the source of MSCs, the dosage of cells administered, transplantation methods, patient inclusion criteria, and the methods of evaluating the effectiveness of the therapy. MSC transplantation in SCI was safe and feasible in all the studies summarized in our review. All studies conducted have demonstrated varying degrees of patient improvement and reduction in the severity of neurological deficits. However, further controlled randomized studies on larger numbers of patients are needed to better evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of MS transplantation. The prospects of the enhancement of the efficacy of the SCI cell therapy with MSCs, including their transplantation with other types of stem cells, administration of MSC-derived exosomes, genetic modification of MSCs, use of the MSC- and other-stem-cell-based tissue-engineered scaffolds, and combination of cell therapy with neuromodulation, are discussed.

1. Introduction

Currently, the epidemiological significance of spinal cord injury (SCI) is increasing worldwide and leads to permanent lifelong motor, sensory and autonomic nervous system disorders, significantly impairing the quality of life and limiting the social and professional activity of patients [1]. The global incidence of SCI is 26.48 cases per million people per year, with a predominance in the male population (the male-to-female ratio is 3.2:1) [2,3]. In the Russian Federation, approximately 8000 patients with varying severity of SCI (American Spinal Injury Association ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) A-D) are registered annually [4,5]. SCI leads to permanent neurological deficit as a result of both primary mechanical damage and secondary damage of the spinal cord caused by neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [6]. Modern approaches of SCI treatment include fracture reduction, surgical decompression of the spinal canal, spinal stabilization, and neurorehabilitation, which aim to reduce secondary damage, but are not capable of significantly enhancing neuroregeneration [1,7]. The economic impact of SCI is substantial: in the absence of effective treatment, the primary expenses are driven by prolonged rehabilitation, which in many cases, fails to restore work capacity in individuals with severe (AIS A) or moderate (AIS B–C) SCI, thereby imposing a considerable burden on healthcare systems [8,9]. Due to the high incidence and disability rates among patients, it is important to develop new approaches to SCI therapy, one of which could be stem-cell-based therapy [7].

A wide range of stem cell types have been investigated in preclinical and early-stage clinical studies for the treatment of experimental spinal cord injury in animal models and humans, including mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), neural stem and progenitor cells, glial progenitor cells, olfactory ensheathing cells, Schwann cells, bone marrow mononuclear cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and others [10,11,12]. Among all cell types, MSCs are the most studied candidates for clinical application [13,14].

MSCs are multipotent cells which can differentiate into mesodermal lineages (osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, and others), and can be relatively easily isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and other sources, including human placental Wharton’s jelly, without any notable ethical concerns [15]. Fundamental in vitro and in vivo studies in recent years have expanded our understanding of the mechanisms of MSC-mediated therapeutic effects in SCI models. The ability of MSCs to replace lost cells in central nervous system (CNS) diseases has not been clearly demonstrated in any fundamental study [16]. The predominant pro-regenerative mechanism of action of MSCs is via paracrine signaling modulating macrophage and microglial polarization at injury sites, activation of regulatory T cells, and extracellular matrix remodeling. The MSCs secretome comprises a range of factors with immunomodulating properties, for example, interleukin 8, interleukin 10 and others (reviewed in [17]). MSC-derived exosomes carry diverse bioactive molecules exerting reparative, immunomodulatory, angiogenic, anti-apoptotic, anti-ferroptotic effects and other pro-regenerative effects. The molecular cargo of such exosomes includes a large number of proteins, including but not limited to several neurotrophic factors, namely, nerve growth factor (NGF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [18]. Furthermore, it contains an array of RNAs, including messenger RNAs [19] and regulatory non-coding RNAs such as mature microRNAs or their precursors [20], long non-coding RNAs [21] and circular RNAs [22]. Additionally, lipids [23] and N-glycans [24] are found in MSC cargo. Remarkably, it has been proposed that MSC-derived exosomes might also carry mitochondria [25,26], which is still a topic of debate. Given space constraints, we refer readers to a recent comprehensive review on this subject [27].

In addition to their paracrine action, MSCs can affect surrounding cells through direct contact, for example, by transferring mitochondria (through nanotunnels, cell fusion, gap junctions, microvesicles, or isolated organelles). This mitochondrial transfer may exert a neuroprotective effect in various pathological conditions by restoring cellular energy reserves and supporting cell viability [28,29,30]. It is also known that MSCs can mediate their effects by interacting with cells in their microenvironment, such as endothelial cells [16,31,32]. The potential of MSCs as a therapeutic agent is further underscored by evidence that they can survive for extended periods of time (at least a week) following direct administration into the site of SCI, potentially exerting therapeutic effects through the mechanisms outlined above [33]. Taken together with their proven safety profile, low immunogenicity, and the relative simplicity and cost-effectiveness of large-scale production, allogeneic MSCs represent a promising candidate for the treatment of diseases and injuries of CNS. To the best of our knowledge, MSCs exert their action via the aforementioned mechanisms and eventually get cleared from the tissue without permanently integrating or differentiating into neural cells within CNS, and no signal of tumorigenicity has been reported in clinical follow-up to date.

Encouraging results from numerous preclinical and fundamental studies, along with advances in understanding the underlying mechanisms of cell therapy, have led to the initiation of clinical trials assessing the impact of MSCs on the progression and outcomes of SCI in humans. A recent comprehensive review by Zeng C et al. [34] summarized the advantages of clinical applications of MSCs, including direct transplantation, tissue-engineering scaffolds and MSC-derived exosome therapies, and highlighted the main molecular mechanism underlining the therapeutic effects of MSCs in SCI.

Given the increasing number of studies combining MSCs with other therapies for SCI (bioscaffolds, functional electrical stimulation, etc.), it has become challenging to evaluate the effects and safety of MSCs as a monotherapy without confounding factors introduced by additional treatments. A more isolated assessment would provide clearer insights into the curative potential and limitations of MSCs. The aim of the present narrative review is to comprehensively summarize and critically analyze all published clinical studies from 2000 to the present, offering a unique and up-to-date synthesis focused exclusively on MSC monotherapy for SCI.

2. Materials and Methods

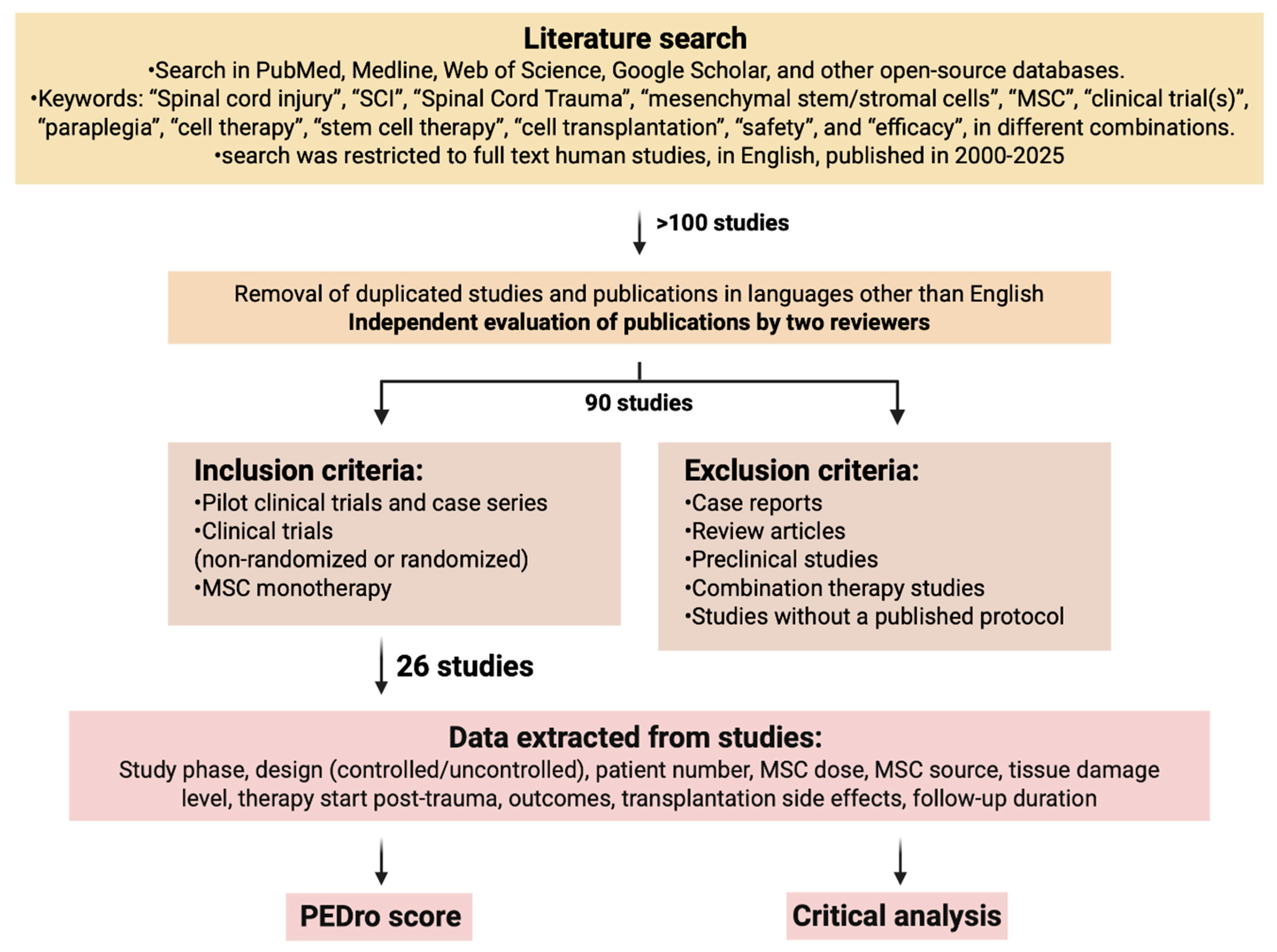

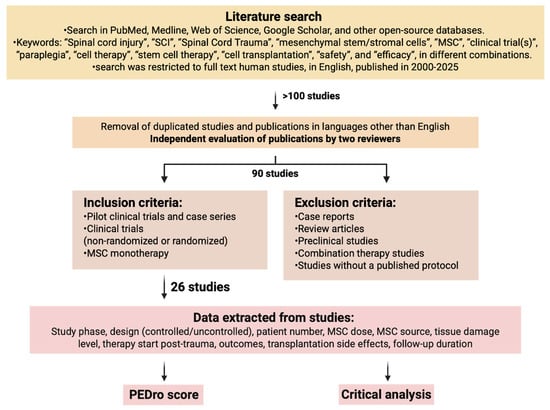

A literature search was performed in the following databases to identify relevant studies: in PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and other open-source databases in August 2025. The following keywords were used: “Spinal cord injury”, “SCI”, “Spinal Cord Trauma”, “mesenchymal stem/stromal cells”, “MSC”, “clinical trial(s)”, “paraplegia”, “cell therapy”, “stem cell therapy”, “cell transplantation”, “safety”, and “efficacy”, in different combinations. The search was restricted to full-text articles in English published in 2000–2025. The study workflow is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The study workflow. Data search strategies for clinical trials about MSCs in SCI (Created in BioRender. Shkap, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/pkvhwko).

As a result of the initial search, more than 100 articles were found. After removing duplicate articles and those in languages other than English (found due to keyword similarities across languages), a total of 90 articles underwent a second-tier evaluation performed by two reviewers independently. Reviewers resolved any disagreements by reaching consensus. Articles to be reviewed were selected based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria: studies on adult participants with neurological impairments caused by SCI, pilot studies, case series, non-randomized and randomized clinical trials, MSC monotherapy. Exclusion criteria: reviews, case reports, preclinical studies, combination therapy studies, studies without a published full protocol. A total of 26 studies were selected. The information gathered from the studies comprised study phase, study design (controlled or uncontrolled, blinded or non-blinded), patient number, MSC dosage, MSC origin, tissue damage level, timing of therapy initiation after trauma, treatment outcomes, side effects of transplantation, and duration of follow-up.

The quality of the studies was assessed by a standard Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale (PEDro), with established quality ratings: 0–3 score classified as “poor”, 4–5 as “fair”, 6–8 as “good”, and 9–10 as “excellent” [35]. Table 1 provides a summary of the reviewed articles.

Table 1.

Results of clinical studies included in the analysis on cell therapy for spinal cord injury.

3. Results of Clinical Studies

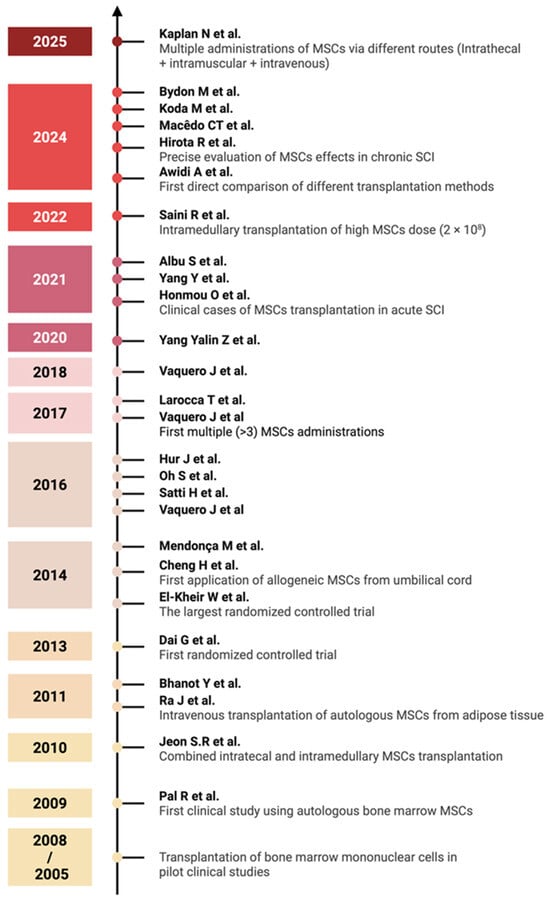

Interest in the use of cell therapy for the treatment of SCI arose at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, when many authors attempted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy in pilot clinical studies: Park H.C. et al. [62], Callera F. et al. [63], Syková E. et al. [64], Yoon S.H. et al. [65], Deda H. et al. [66], Geffner L.F. et al. [67]. It is known that bone marrow mononuclear cells contain MSCs, but in relatively small quantities (0.001–0.03%) [68,69], so we did not include these studies in the analysis. The earliest identified study on MSC-derived monotherapy dates to 2009 [36]. Thus, this review encompasses 26 studies on MSC therapy for SCI from 2009 to 2025 (over 17 years), with a summary of the data presented in Table 1.

3.1. Design of Clinical Trials

Tests were conducted in various countries, including China [40,41,51,54], Egypt [42], Brazil [43,48,60], South Korea [37,39,44,45], Pakistan [46], Turkiye [61], Spain [47,49,50,52], Japan [53,58,59], India [36,38,55], Jordan [57], and the United States [56], indicating global interest in this issue. Most clinical trials were phase I and/or II studies and were designed to demonstrate the safety and tolerability of treatment, as well as to preliminarily assess the efficacy of MSC transplantation in SCI. The number of patients included in the trials ranged from 5 to 68 per cohort. Control groups—comprising patients who received either placebo or standard treatment without cell therapy—were incorporated in fewer than one-quarter of the studies [40,41,42,51,52,55]. These studies also adhered to randomized controlled trial designs in accordance with current clinical trial standards.

Patient inclusion criteria varied significantly between studies. In particular, the level of SCI varied, ranging from isolated cervical [40,45,53,58,59,60], thoracic [46,47,48,52,61], or lumbar [41] lesions to mixed lesions in a majority of studies. The predominance of studies including patients with cervical spine injuries is probably due to the greater clinical significance of restoring function in this location of injury.

Variability was also observed in the degree of neurological deficit of the included patients on the AIS [70]. For instance, the studies by Cheng H. et al. [41] and Vaquero J. et al. [47] enrolled only patients with complete injury (AIS A), while other studies included patients with varying degrees of injury. The time after injury at the start of therapy also varied significantly, from early (up to 1 month) to late recovery periods (after 6 months). The majority of analyzed studies focused on patients with subacute and chronic SCI, predominantly those with severe injury (AIS A-B). This likely reflects both logistical factors and the high prevalence of patients with chronic SCI complicated by disabling neurological deficits, positioning them as the primary target population for regenerative therapies. However, despite the general trend, there have recently been studies describing the effects of MSC in patients with acute SCI [53,55,58], as well as in patients with moderate-to-severe SCI (AIS C-D) [59].

This variation in patient selection criteria should be taken into account when comparing data on the effectiveness of cell transplantation in analyzing various studies, since it is known that the potential for the spontaneous recovery of neurological deficits varies significantly between complete and incomplete spinal cord injuries and also depends on the duration of the injury [71]. Several researchers have additionally highlighted the critical importance of an accurate initial assessment of spinal cord injury severity, as misinterpretation—particularly in studies involving patients with acute trauma—may lead to an overestimation of therapeutic effects attributed to the intervention [72,73].

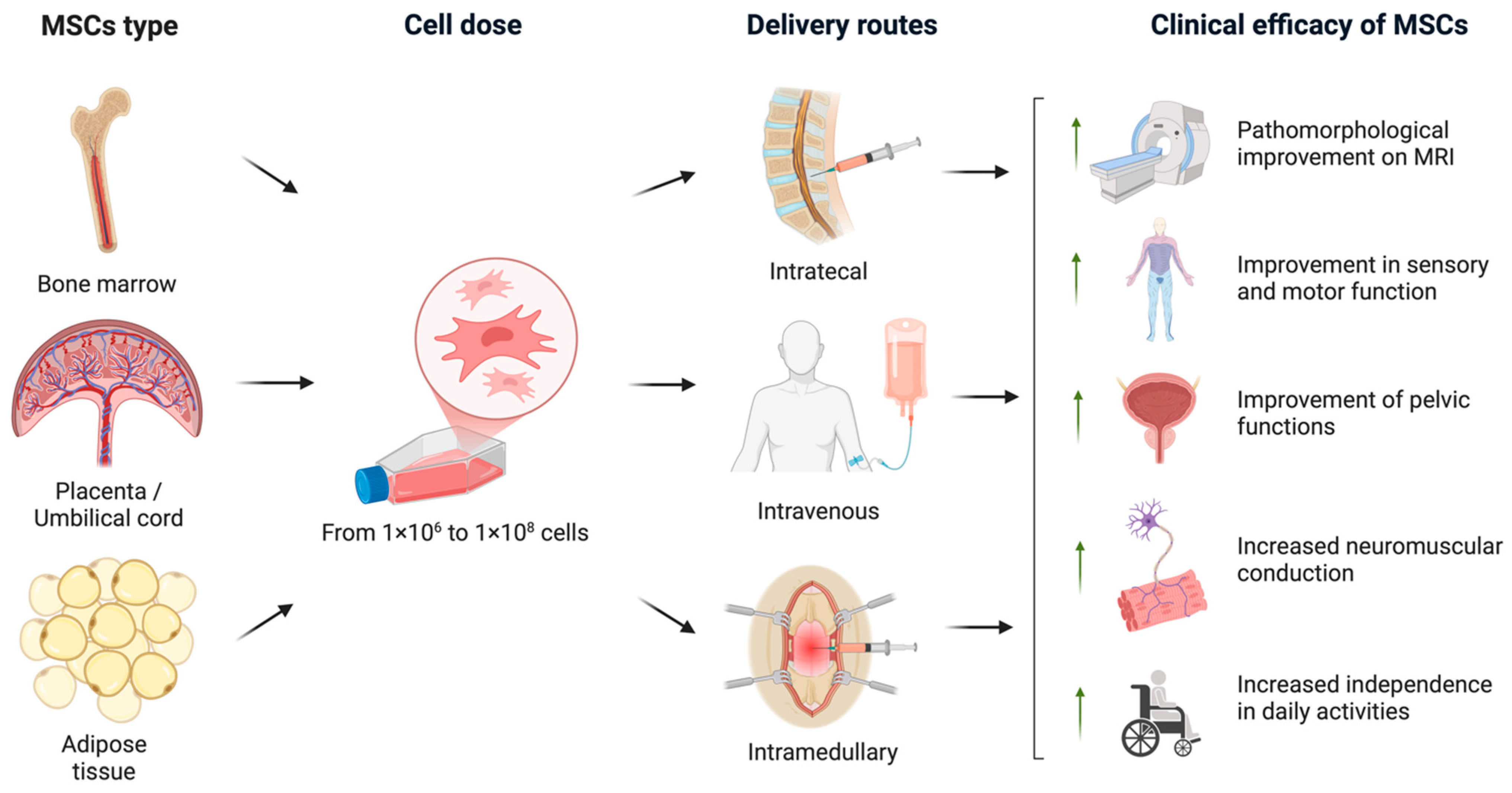

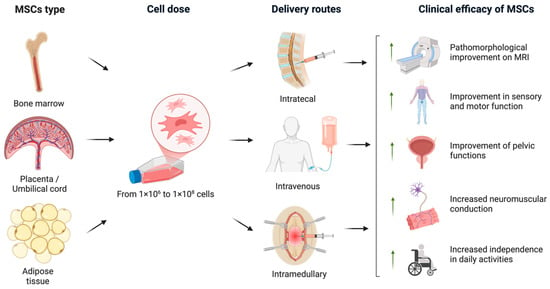

In the analyzed studies, either allogeneic or autologous MSCs derived from various sources, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord, were used. The cells were administered via intrathecal injections, direct intramedullary injection into the lesion site, and/or intravenous infusion, with MSC doses ranging from 1 × 106 to 1 × 108 cells (the data are shown in Table 1).

Safety and efficacy were evaluated in patients over a follow-up period ranging from 6 months to 5 years (see Table 1). This variability reflects different approaches to defining the time frame for possible patient recovery, encompassing early indicators of remyelination as well as long-term functional adaptation. The methods used to evaluate therapeutic efficacy—including primary and secondary endpoints and assessment techniques—also differed across studies. AIS was most commonly employed as the primary efficacy measure, aligning with international standards for neurological assessment in spinal cord injury [70,74].

Additional assessment tools included specific functional scales to quantify patients’ levels of independence in daily activities, notably the Barthel Index and the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (SCIM III) [75]. Urodynamic evaluations were performed to objectively assess recovery of pelvic organ function, while neuroimaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were utilized to characterize structural changes. Along with standard neurological scales, a number of studies [41,45,52,53,58] used electrophysiological methods to assess the integrity of the conduction pathways. Therapeutic efficacy was assessed through a series of longitudinal control measurements of selected outcome variables, typically conducted at baseline (pre-intervention), and subsequently, at 3, 6 and 12 months post-treatment.

Notably, several research groups conducted a series of sequential clinical trials evaluating the same type of MSCs with various modifications to the transplantation protocol, including cell dosage, administration route, and frequency [37,45,47,48,49,50,60]. These studies progressively demonstrated that higher MSC doses, repeated transplantations, and combined administration methods resulted in enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

3.2. Safety of MSC Transplantation

All analyzed studies, regardless of their design, confirmed the safety of MSC transplantation. Across patients with varying injury levels, injury durations, and degrees of neurological deficit as assessed by the ASIA scale, reported adverse effects were predominantly mild—such as headache, nausea, and transient fever—or not reported at all. For example, in the largest (in terms of the number of subjects; 70 patients) randomized, controlled phase I/II study conducted at Cairo University [42], it was reported that no severe adverse events were observed over an 18-month follow-up period after intrathecal administration of autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs. Specifically, no inflammatory or infectious complications, intracranial hypertension, or carcinogenic effects were reported, underscoring the favorable safety profile of MSC transplantation in spinal cord injury. Similarly, a number of studies employing intrathecal, intramedullary, or combined ways of MSC administration reported no severe adverse effects, even during long-term follow-up (Table 1). In the study by Kaplan N. et al. [61], patients received MSCs sequentially through three different routes—intrathecal, intramuscular, and intravenous—administered four times over two months, and even this complex combined administration protocol demonstrated good tolerability and safety.

It is important to note that among all methods of administration routes, intramedullary transplantation (administration of MSCs directly into the area of SCI) was associated with the highest risk of complications in the form of local pain syndrome in the area of surgical intervention, increased sensory disturbances, muscle rigidity, and increased body temperature [41,47,57]. The authors of these studies attribute such adverse effects primarily to the neurosurgical procedure rather than to the transplanted stem cells themselves. Despite these moderate side effects, patients receiving intramedullary MSC transplantation demonstrated significant neurological improvements following this delivery method.

Two studies have reported serious complications in patients with SCI, such as bacterial pneumonia, meningitis [47], urinary tract infection, acute bronchitis, and even the death of one patient due to aspiration pneumonia [58]. However, in all cases, complications were deemed nonspecific by the investigators and predominantly ascribed to comorbid illness, chronic trauma, prolonged intensive care admission, or the heightened risk of nosocomial infection, rather than to MSC transplantation itself.

3.3. Clinical Efficacy of MSC Transplantation

3.3.1. Timing-Dependent Outcomes

In the majority of analyzed studies, where MSC transplantation was performed within the first six months after SCI, improvements on the AIS grade were observed [36,53,54,55,58]. In a recent phase I trial by Koda M. et al. [58], patients in the early recovery period after SCI (within 3 weeks post-injury) underwent a single intravenous transplantation of 15 × 106 MSCs. By the end of the observation period, significant improvements in sensory and motor function were reported, and 6 out of 10 patients exhibited improvement on the Frankel neurological scale (a modified analog of AIS [76]). Similarly, an earlier case series study by Honmou O. et al. [53] documented improvement in AIS A grade in 12 of 13 patients with intravenous MSC administration during the acute phase of SCI. In one study, a direct comparison of the impact of MSC transplantation in subacute versus chronic cases was performed [36]. While no improvements in AIS grade were detected in both groups, functional status—measured by the Barthel Index—improved in 5 of 14 subacute patients but in none of the chronic SCI group.

The superior therapeutic outcomes observed with early initiation of MSC administration could be most likely attributable to enhanced neuroplasticity during the acute phase of injury and the reduced presence of irreversible pathological changes, such as glial scar formation and Wallerian degeneration of axons within the descending pathways distal to an injury site [77,78,79]. This pattern mirrors findings after neurosurgical interventions, where spinal cord decompression performed early post-injury is associated with better functional recovery of patients with SCI [80,81]. Furthermore, numerous preclinical studies demonstrate that stem cell transplantation administered during the acute and subacute phases of SCI yields the most favorable neurological improvements in animal models [82].

However, the majority of analyzed studies have reported MSC transplantations performed during the chronic phase following SCI, with intervals extending up to 26 years post-trauma. Despite this delayed timing, patients demonstrated varying degrees of neurological recovery, including restoration of motor, sensory, and autonomic functions, including pelvic organ control, thereby supporting the potential for functional restoration even long after injury. For instance, a controlled clinical trial by Dai G. et al. [62] demonstrated that autologous bone marrow-derived MSC administration in chronic SCI resulted in improved sensory and motor scores on the AIS in 9 of 20 treated patients, and that that was a significantly better outcome than observed in the control cohort. This therapeutic benefit may be attributed to the relatively high local MSC dose (8 × 105 cells) delivered into the subarachnoid space adjacent to the injury site. These findings align with recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, confirming the efficacy of MSC transplantation in traumatic SCI [12,83,84].

Summarizing the current evidence regarding the timing of traumatic SCI MSC transplantation, it is evident that earlier start of treatment yields the most favorable outcomes. Nonetheless, further large-scale, randomized controlled trials are necessary to precisely define the optimal “therapeutic window” for MSC transplantation.

3.3.2. Influence of Injury Severity

Patients with incomplete SCI exhibit a markedly greater capacity for spontaneous motor and sensory recovery within the first 6–12 months post-injury, attributed to the preservation of conduction pathways and neuroplastic mechanisms. In contrast, complete injuries (AIS grade A) demonstrate severely limited recovery potential due to extensive anatomical damage of the spinal cord [85]. The aforementioned patient inclusion criteria in the studies analyzed in this review varied significantly concerning the severity of SCI, classified on the AIS grade from A to D. In most studies involving cell transplantation in patients with complete SCI (AIS grade A), functional improvements were minimal and progressed slowly [44,48]. Nevertheless, in some cases [56,58], even in patients with ASIA grade A, partial recovery of neurological deficits was observed, particularly when intervention was administered early and involved high doses of MSCs.

The recent study by Hirota R. et al. [59] further supports these findings. It reports a clinical series involving patients with moderate-to-severe SCI classified as AIS grade C-D, who were enrolled in the experimental arm after completing a course of physical therapy and reaching a neurological plateau. Following intravenous administration of autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs, only one out of seven patients exhibited an improvement in AIS grade from C to D. Nevertheless, all patients demonstrated either maintained or enhanced functional status. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first study specifically highlighting neurorehabilitation potential in patients with incomplete chronic SCI.

3.3.3. Effect of MSC Type

Clinical studies have reported transplantation of both allogeneic and autologous MSCs obtained from different sources [86]. However, due to substantial heterogeneity in study designs, it remains inconclusive which MSC type confers the greatest therapeutic benefit in SCI treatment. In most of the studies, the transplanted MSCs were autologous bone marrow-derived cells, likely because these cells had been previously used in pilot studies. Additional reasons for the preference of bone marrow-derived MSCs include their extensive characterization, the relative ease of their extraction and processing, and their well-established safety profile. Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Liu et al. [87] showed that transplantation of MSCs from bone marrow in humans led to superior functional outcomes compared to MSCs derived from alternative sources. In the studies conducted by Bydon M. et al. [56] and Hur J et al. [44], MSCs derived from adipose tissue were transplanted, demonstrating promising therapeutic effects, although their use was limited to these two investigations. Autologous MSC transplantation is considered safe and ethically unproblematic; however, its application in acute trauma is constrained by the time required for MSC collection and preparation. During the acute phase, the administration of allogeneic MSCs from pre-established banks of standardized and thoroughly characterized cells obtained from selected donors could be more appropriate. Additionally, several studies indicate that the regenerative capacity of MSCs is influenced by the donor’s age, diminishing as a consequence of natural aging processes [88]. This further supports the rationale for utilizing MSCs sourced from established cell banks.

Several clinical studies conducted over the past five years by Albu S. et al. [52], Yang Y. et al. [54], Awidi A. et al. [57], and Kaplan N. et al. [61], which have also demonstrated a pronounced positive therapeutic benefit of umbilical cord MSCs. Notably, fundamental animal research involving direct comparisons of MSCs from various sources revealed that umbilical cord MSCs confer superior therapeutic effects [89,90]; however, the efficacy of umbilical cord MSCs in humans requires further validation through large-scale randomized clinical trials.

3.3.4. Impact of Transplantation Parameters

In the analyzed studies, MSCs were delivered via various routes: intramedullary injection directly into the injury site, intrathecal administration, or intravenous infusion. Intrathecal delivery was the most common approach, utilized in 16 of 26 studies [36,37,38,42,44,46,47,49,50,51,52,54,56,57,60,61], likely due to its minimal invasiveness and the advantage of delivering cells directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, including around the lesion site. Intramedullary administration, employed in 11 studies (see Table 1) [37,38,40,41,43,45,47,48,55,57,60], enables targeted delivery of cells to the lesion but carries a higher risk of complications related to the surgical procedure itself, as noted earlier. It should be noted that a study by Awidi A. et al. demonstrated that combined intramedullary and intrathecal administration resulted in superior therapeutic efficacy compared to intrathecal delivery alone [39].

In the studies conducted by Ra J et al. [39], Honmou O. et al. [53], Koda M. et al. [58], and Hirota R et al. [59], MSCs were transplanted intravenously into patients with SCI. These investigations reported significant improvements in both sensory and motor functions, which may be attributed to the paracrine actions of MSCs—particularly their anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic effects—which are well-documented in systemic transplantation for neurological disorders [91,92,93].

Jug M. et al. [94] reported a clinical case of a young patient with acute SCI (3 months after trauma at the C3-C4 level with subtotal spinal cord injury) to investigate the biodistribution of MSCs following intravenous and intrathecal transplantation using radionuclide imaging techniques. In this study, autologous MSCs were initially administered intravenously at a dose of 15 × 107 cells, with one-third labeled with a technetium Tc-99m, and their distribution was tracked over the subsequent 20 h. The study demonstrated predominant retention of MSCs in the reticuloendothelial system, lungs, and bone marrow, while their detectable amount at the site of spinal cord injury was insignificant.

Two weeks later, the same dose of MSCs was re-administered intrathecally using the same labeling protocol. Post-intrathecal administration, MSCs initially localized near the injection site and gradually migrated toward the injury site, with signals detectable along the entire spinal cord after 20 h. These findings led the authors to conclude that despite the ability of MSCs to actively migrate to the site of injury after intravenous transplantation, intrathecal administration is a more effective and perceptive method of MSC transplantation in the case of SCI. Nevertheless, intravenous delivery may elicit systemic therapeutic effects via organs of the reticuloendothelial system [95].

It is important to note that among the analyzed studies, both the administered cell dose and the frequency of administration varied considerably. While most studies implemented a single transplantation of MSCs, several trials adopted protocols involving repeated administration [37,38,46,47,49,50,54,57]. Currently, clinical data are insufficient to establish an optimal dosing regimen. However, preclinical investigations indicate that the regenerative effects of MSCs on spinal cord repair are dose-dependent and are potentiated by repeated transplantation, a phenomenon likely applicable to MSC therapies in humans [96].

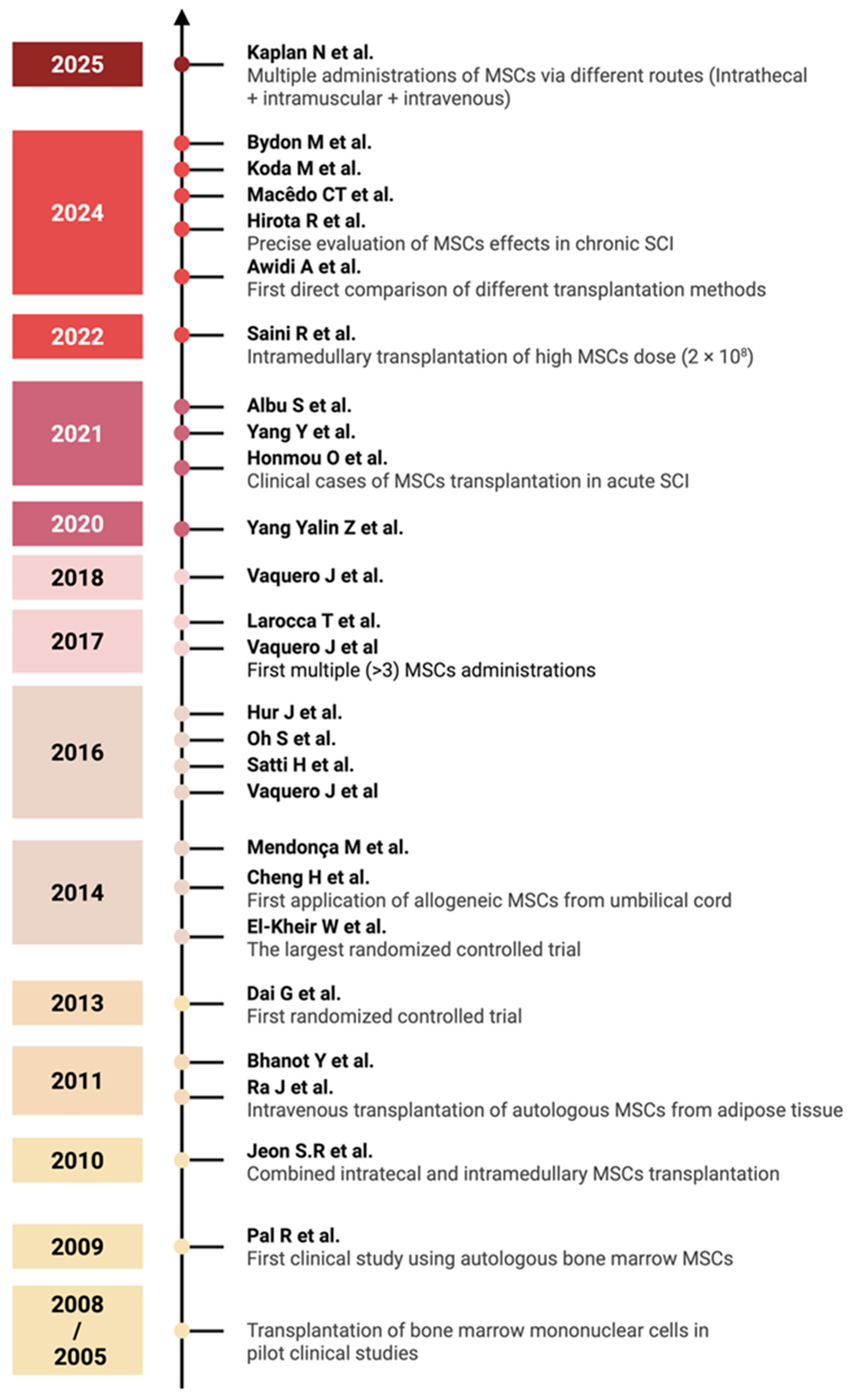

An overview of the various clinical trial designs and their outcomes is schematically illustrated in Figure 2. A timeline of clinical studies on MSC monotherapy for SCI is shown in Figure 3, illustrating major advances in administration routes, transplantation techniques, and trial design over the past two decades summarizing the chronological development of MSC monotherapy trials conducted between 2009 to the present. Despite the numerous studies conducted to date, the precise mechanisms—and their sequential interplay—by which MSCs exert therapeutic effects in spinal cord injury remain insufficiently understood and require further fundamental investigation using animal models of SCI [18]. A more comprehensive elucidation of these mechanisms may help to identify optimal transplantation parameters and inform strategies to enhance the efficacy of MSC-based treatments in future clinical studies.

Figure 2.

An overview of the various clinical trial protocols and the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in SCI. In the analyzed clinical trials, MSCs were derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and placental or umbilical cord sources. The administered MSC dose ranged from 1 × 106 to 1 × 108 cells. The cells were transplanted via intrathecal, intravenous, or intramedullary routes. The most prominent clinical outcomes included pathomorphological improvements observed on MRI, enhanced sensory and motor function, recovery of pelvic organ function, improved neuromuscular conduction, and increased independence in daily activities (created in BioRender, Shkap, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/uy6wvqo).

Figure 3.

Timeline of clinical studies on MSC monotherapy for SCI, 2005–2025. Major milestones highlighted include the evolution of administration routes, the conduct of randomized controlled trials, and the development of transplantation methods [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Each year marks the publication of key studies that have influenced clinical practice in MSC-based SCI therapy (created in BioRender, Shkap, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/zv7cnwh).

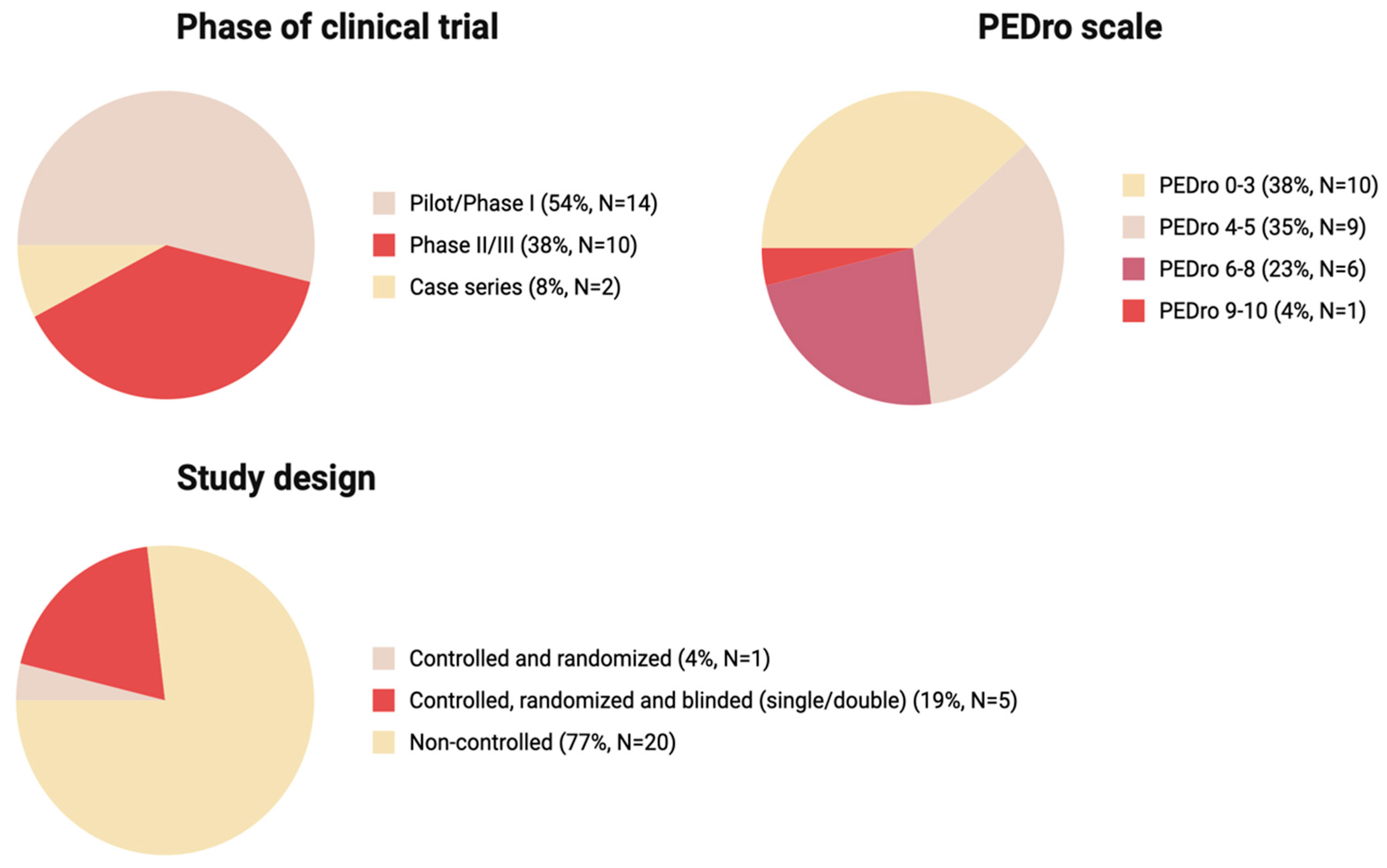

4. Quality of Clinical Trials

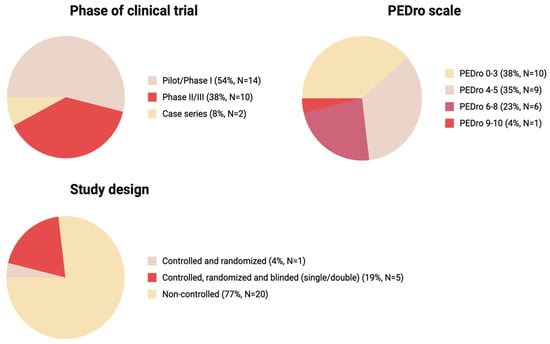

Of all analyzed studies, 54% were Pilot/Phase I series, 38% were Phase II/III, and the remaining 8% were Case series, indicating overall heterogeneity and predominance of early phase studies over more rigorous Phase II/III (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The key characteristics of the studies: phase of clinical trial, PEDro scale score, study design (Created in BioRender. Shkap, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/35ozng7).

We used the PEDro scale as a suitable tool for the assessment of the methodological quality of the studies with varying study designs. Most studies (n = 19) had a low PEDro score below 5, 23% of studies (n = 6) had scores of 6–8, and 4% had score in a 9–10 range (n = 1) (Figure 3). The threshold of PEDro score of 6 is recommended to be used for systematic reviews as one of the inclusion criteria. The high number of studies with a PEDro score below 5 was due to the high number of pilot studies (without randomization, blinding and a control group) in our narrative review.

Randomization and blinding are a key characteristic assessed by the majority of the Clinical Trial Evaluation Systems. Across the 26 studies presented in this review, most studies (77%) were non-randomized pilot studies (Figure 3) with varying designs and methods of MSC administration. Although some pilot studies reviewed in our study report successes of the therapy, after detailed evaluation and the introduction of randomization, the effect of MSC therapy appears to not be that pronounced; the most prominent outcome was improved bladder sensitivity and function [52,55]. Of 26 studies analyzed, only one study was controlled and randomized (4%) and only five were controlled, randomized and blinded (19%) (Figure 3). Of all studies analyzed, only two with the highest PEDro scores, 8 and 9, indicating best quality were randomized and double blinded (Table 1).

Based on this, direct comparison of therapeutic efficacy across the studies described in the review is challenging due to significant variations in the results, which might be attributed to differences in the ethnic characteristics of patients and national standards of medical care. Further, the studies did not have a unified protocol and differed significantly in their design, including the presence or absence of control groups without cell therapy, patient inclusion criteria, sources and characterization standards of MSCs, dosing regimens and administration frequency, transplantation methods, and approaches for evaluating therapeutic efficacy. Patient inclusion criteria varied significantly between studies, reflecting the lack of a standardized approach to selecting candidates for cell therapy at present. Variability was also observed in the degree of neurological deficit of the included patients on the AIS. Such methodological heterogeneity poses challenges for direct comparison of results across studies.

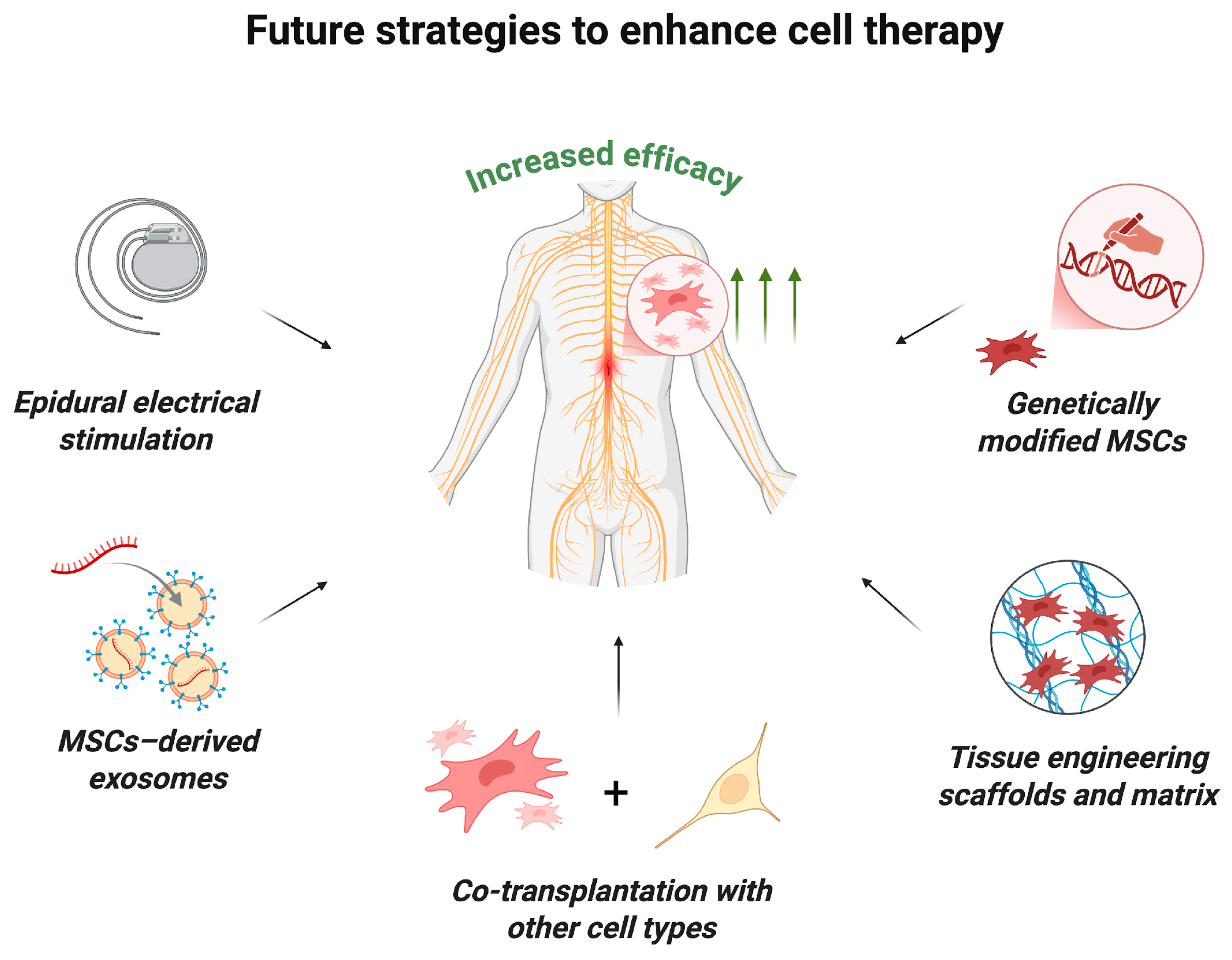

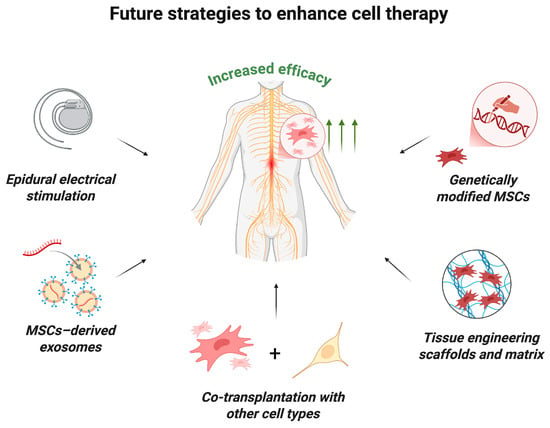

5. Future Prospects

Clinical trials have demonstrated that MSC monotherapy is safe, though its therapeutic efficacy can be potentially enhanced by combining it with other strategies (Figure 5) [18]. For example, experimental studies in animal models of SCI have shown that MSC transplantation in combination with tissue-engineering scaffolds can improve treatment outcomes and promote more targeted and controlled axon regeneration, improve the microenvironment and increase the survival of transplanted cells [97,98,99,100]. Active research and development efforts are underway in this rapidly evolving field. A pilot clinical study by authors who previously reported a study of MSC monotherapy in humans demonstrated the safety and feasibility of intramedullary administration of human umbilical cord MSCs in combination with a collagen scaffold [101]. This approach facilitated axonal growth along collagen fibers and inhibited glial scar formation.

Figure 5.

Future strategies to enhance MSC therapy. The efficacy of MSC transplantation may be increased by the following innovative approaches: the use of epidural electrical stimulation; combined transplantation with MSC-derived exosomes, other types of stem cells or tissue-engineering scaffolds and matrix; transplantation of genetically modified MSCs (created in BioRender, Shkap, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/i3l4hes).

Despite considerable progress in the application of native MSCs for treating SCI, their therapeutic potential is often insufficient for complete restoration of neurological function. In this regard, the development of genetically modified MSCs is a promising strategy for enhancing their regenerative properties and improving the effectiveness of cell therapy. Genetic modification enables the targeted expression of therapeutically relevant factors such as BDNF, GDNF and NGF, among others [102]. For instance, transplantation of MSCs engineered to overexpress interleukin-10 significantly improved motor function in a mouse model of complete SCI compared to native MSCs, which can be attributed to enhanced anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and neuroprotective effects of MSCs [103]. Similarly, Yang et al. [104] demonstrated that MSCs overexpressing neuropeptide S yielded superior therapeutic outcomes in a rat model of SCI, including improved motor recovery, marked reduction in scarring, increased neuroregeneration and neurogenesis. Furthermore, Jiang et al. [105] reported that erythropoietin-overexpressing MSCs exerted potent anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective effects in models of ischemic–hypoxic injury.

Another promising therapeutic strategy involves the administration of MSC-derived exosomes, which have demonstrated significant efficacy in treating SCI in preclinical models [106]. Liu et al. [21] showed that intravenous administration of exosomes derived from MSCs engineered to overexpress the tectonic family member 2 gene significantly enhanced functional recovery in a murine SCI model, presumably through inhibition of neuronal apoptosis and suppression of inflammation and oxidative stress in the injured spinal cord. Another example of successful use of modified MSCs for SCI treatment is the work of Chen et al. [107], in which rats with SCI were intravenously administered exosomes isolated from miR-26a-modified MSCs, showing marked recovery of neurological deficits in the animals. The authors observed activation of neuroregeneration, neurogenesis, and reduced glial scar formation. These effects were attributed to the activation of the PTEN/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, which may be one of the potential targets for enhancing neuroregeneration [108].

An additional promising approach is the combined transplantation of MSCs with other types of stem cells [109]. Early clinical trials have explored this approach in patients with SCI. In a pilot study conducted by Oraee-Yazdani et al. [110], 11 patients with subacute severe SCI underwent a single intrathecal transplantation of autologous Schwann cells together with bone marrow MSCs. The study confirmed the safety and feasibility of such a combined cell transplantation approach and demonstrated its initial effectiveness in the form of improved motor, sensory, and pelvic functions in patients. A recent preclinical study by Kim et al. [111] demonstrated the higher efficacy of co-administration of MSCs and neural progenitor cells compared to monotherapy, as evidenced by more pronounced functional recovery of animals, enhanced axonal neurogenesis, and motor neuron maturation. The results of this study also demonstrated that stepwise combined cell transplantation was more effective than monotherapy (even with repeated MSC administrations) and had a pronounced neuroregenerative effect. The authors attribute the therapeutic effect to the synergistic action of different stem cell types and improvement of the microenvironment during combined transplantation [112].

Moreover, recent investigations have highlighted the potentiation of MSC therapy effects by combining cell transplantation with neuromodulation techniques. These studies demonstrated that simultaneous stimulation of spared conductive pathways enhances the overall therapeutic impact of MSC-based therapy [113,114].

Recently, our team conducted preclinical studies on MSCs for traumatic SCI, demonstrating efficacy when delivered within a fibrin hydrogel and platelet-enriched plasma matrix, followed by invasive neuromodulation below the lesion and rigorous physical rehabilitation (data forthcoming, Russian patent, 26 November 2024: https://fips.ru/EGD/734a8ff9-32b8-47f7-8c70-9382e8c2d185). These findings supported regulatory approval for a phase I/II clinical trial (FCBRN-RM01-2023, https://grlsbase.ru/clinicaltrails/clintrail/14481 accessed on 10 October 2025). This work and related studies aim to establish MSCs as key immunomodulatory and regenerative agents within multimodal traumatic spinal injury therapies.

6. Conclusions

The collective findings from the analyzed clinical trials indicate that MSC transplantation in SCI is safe and feasible.

Preliminary efficacy data suggest improvements in neurological function, including restoration of motor, sensory, and autonomic nervous system functions. However, the pilot nature of many studies, lack of control groups in several cases, and heterogeneity in trial design require cautious interpretation of these results. Here, it should be acknowledged that the field of MSC therapy for SCI is highly heterogeneous and generally low in clinical strength. To confirm the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in SCI and establish an optimal transplantation protocol, larger multicenter randomized controlled trials are necessary.

After detailed evaluation and the introduction of randomization, the effect of MSC therapy appears to not be that pronounced, with the most prominent outcome being improved bladder sensitivity and function. Future strategies to enhance cell therapy efficacy may include combining MSC transplantation with established treatments such as neuromodulation, neurorehabilitation, and surgical intervention for SCI, as well as adjunctive approaches like functional electrical stimulation, the administration of MSC-derived exosomes, co-implantation with tissue-engineered scaffolds, genetic modification of MSCs, and co-administration with other cell types to potentiate neuroregeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N., V.B. and K.Y.; methodology (article search) M.S., E.C., A.B. and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation M.S., D.N. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, V.B., K.Y., D.N. and D.C.; funding acquisition, V.B. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study of clinical trials was funded by FMBA of Russia. The study of molecular mechanisms and biological effects was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (federal scientific and technical program for the development of genetic technologies for 2019–2030: 075-15-2025-519).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not required.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| ASIA | American Spinal Injury Association |

| AIS | ASIA Impairment Scale |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| GDNF | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| SCIM III | Spinal Cord Independence Measure III |

| PEDro | Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale |

References

- Ahuja, C.S.; Wilson, J.R.; Nori, S.; Kotter, M.R.N.; Druschel, C.; Curt, A.; Fehlings, M.G. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadour, F.A.; Khadour, Y.A.; Meng, L.; XinLi, C.; Xu, T. Epidemiology Features of Traumatic and Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in China, Wuhan. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Pang, M.; Hu, X.; Dai, Y.; Shen, R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Luo, T.; et al. Global Incidence and Characteristics of Spinal Cord Injury since 2000–2021: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharikov, Y.; Nagaytseva, A.A.; Nikolenko, V. Spinal Injuries in Compression Fractures of the Spine: Neurological Insufficiency and Rehabilitation of Patients with Neurological Disorders. Med. News North Cauc. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobzin, S.V.; Mirzaeva, L.M.; Tcinzerling, N.V.; Dulaev, A.K.; Tamaev, T.I.; Tyulikov, K.V. Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Saint Petersburg. Epidemiological Data: Incidence Rate, Gender and Age Characteristics. Her. North-West. State Med. Univ. Named II Mechnikov 2019, 11, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, W.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Huang, R.; Ma, B.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, R.; Cheng, L. Spinal Cord Injury: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipser, C.M.; Cragg, J.J.; Guest, J.D.; Fehlings, M.G.; Jutzeler, C.R.; Anderson, A.J.; Curt, A. Cell-Based and Stem-Cell-Based Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury: Evidence from Clinical Trials. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlings, M.G.; Tetreault, L.A.; Wilson, J.R.; Kwon, B.K.; Burns, A.S.; Martin, A.R.; Hawryluk, G.; Harrop, J.S. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Introduction, Rationale, and Scope. Glob. Spine J. 2017, 7, 84S–94S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diop, M.; Epstein, D. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Spinal Cord Injury on Costs and Health-Related Quality of Life. Pharmacoecon Open 2024, 8, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Wanyan, P. Clinical Translation of Stem Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury Still Premature: Results from a Single-Arm Meta-Analysis Based on 62 Clinical Trials. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, B.F.; da Cruz, B.C.; de Sousa, B.M.; Correia, P.D.; David, N.; Rocha, C.; Almeida, R.D.; da Cunha, M.R.; Marques Baptista, A.A.; Vieira, S.I. Cell Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury: A Review of the Clinical Trials and Cell-Type Therapeutic Potential. Brain 2023, 146, 2672–2693, Correction in Brain 2023, 146, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoto-Meijide, R.; Meijide-Faílde, R.; Díaz-Prado, S.M.; Montoto-Marqués, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Rao, J.; Lin, F.; Yang, Z.; Wang, R.; Chen, C. Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of Cell Transplantation for Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 860131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.D.V.; Pickard, M.R.; Johnson, W.E.B. The Comparative Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury in Humans and Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biology 2021, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Li, C.; Xiao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Rong, M.; Zeng, J. Beyond Conventional Therapies: MSCs in the Battle against Nerve Injury. Regen. Ther. 2025, 28, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, Q.-L. Mechanisms Underlying the Protective Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2771–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigo, C.M.; Rodrigues, J.S.; Camões, S.P.; Solá, S.; Miranda, J.P. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Regenerative Medicine: Where Do We Stand? J. Adv. Res. 2025, 70, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Fu, C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury: Mechanisms, Current Advances and Future Challenges. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1141601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, E.; Banfi, F.; Barilani, M.; Cherubini, A.; Parazzi, V.; Larghi, P.; Dolo, V.; Bollati, V.; Lazzari, L. Extracellular Vesicle-Shuttled MRNA in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Communication. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.S.; Lai, R.C.; Lee, M.M.; Choo, A.B.H.; Lee, C.N.; Lim, S.K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretes Microparticles Enriched in Pre-MicroRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, M.; Qiao, F.; Zhang, C. Exosomes Derived from LncRNA TCTN2-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Spinal Cord Injury by MiR-329-3p/IGF1R Axis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 72, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Hao, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y. Hypoxia-Treated Umbilical Mesenchymal Stem Cell Alleviates Spinal Cord Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in SCI by Circular RNA CircOXNAD1/MiR-29a-3p/FOXO3a Axis. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 34, 101458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzinat, N.; Ong-Meang, V.; Bourgailh-Tortosa, F.; Blanzat, M.; Perquis, L.; Cussac, D.; Parini, A.; Poinsot, V. Extracellular Vesicles of MSCs and Cardiomyoblasts Are Vehicles for Lipid Mediators. Biochimie 2020, 178, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clos-Sansalvador, M.; Garcia, S.G.; Morón-Font, M.; Williams, C.; Reichardt, N.-C.; Falcón-Pérez, J.M.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Roura, S.; Franquesa, M.; Monguió-Tortajada, M.; et al. N-Glycans in Immortalized Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Critical for EV–Cell Interaction and Functional Activation of Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Tong, B.; Ke, W.; Yang, C.; Wu, X.; Lei, M. Extracellular Vesicles as Carriers for Mitochondria: Biological Functions and Clinical Applications. Mitochondrion 2024, 78, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorova, L.D.; Kovalchuk, S.I.; Popkov, V.A.; Chernikov, V.P.; Zharikova, A.A.; Khutornenko, A.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Plokhikh, K.S.; Zinovkin, R.A.; Evtushenko, E.A.; et al. Do Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Contain Functional Mitochondria? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, C. MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Roles and Molecular Mechanisms for Tissue Repair. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 7953–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.C.; Shukla, M.; Shukla, M. From Bench to Bedside: Translating Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies through Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchetti, F.; Carloni, S.; Nasoni, M.G.; Reiter, R.J.; Balduini, W. Tunneling Nanotubes and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: New Insights into the Role of Melatonin in Neuronal Recovery. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 73, e12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babenko, V.; Silachev, D.; Popkov, V.; Zorova, L.; Pevzner, I.; Plotnikov, E.; Sukhikh, G.; Zorov, D. Miro1 Enhances Mitochondria Transfer from Multipotent Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MMSC) to Neural Cells and Improves the Efficacy of Cell Recovery. Molecules 2018, 23, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Xu, L.; Dong, L.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zang, X.; et al. Cell–Cell Contact with Proinflammatory Macrophages Enhances the Immunotherapeutic Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Two Abortion Models. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2019, 16, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cselenyák, A.; Pankotai, E.; Horváth, E.M.; Kiss, L.; Lacza, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Rescue Cardiomyoblasts from Cell Death in an in Vitro Ischemia Model via Direct Cell-to-Cell Connections. BMC Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkap, M.O.; Chudakova, D.A.; Gubsky, I.L.; Kovalchuk, A.M.; Doroshenko, Y.S.; Kibirsky, P.D.; Kirsova, D.P.; Yusubalieva, G.M.; Baklaushev, V.P. Fate of Transplanted Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in the Rat Spinal Cord under Normal Conditions and during the Acute Phase of Spinal Cord Contusion Injury. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2025, 179, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.-W. Multipotent Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Biology 2023, 12, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro Scale for Rating Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Venkataramana, N.K.; Bansal, A.; Balaraju, S.; Jan, M.; Chandra, R.; Dixit, A.; Rauthan, A.; Murgod, U.; Totey, S. Ex Vivo-Expanded Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Human Spinal Cord Injury/Paraplegia: A Pilot Clinical Study. Cytotherapy 2009, 11, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Sung, I.Y.; Choi, G.H.; Jeon, M.H.; Kim, K.K.; Jeon, S.R. Long-Term Results of Spinal Cord Injury Therapy Using Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Bone Marrow in Humans. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, Y.; Rao, S.; Ghosh, D.; Balaraju, S.; Radhika, C.R.; Satish Kumar, K.V. Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 25, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, J.C.; Shin, I.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, S.K.; Kang, B.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Jo, J.Y.; Yoon, E.J.; Choi, H.J.; et al. Safety of Intravenous Infusion of Human Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Animals and Humans. Stem Cells Dev. 2011, 20, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Xu, R. Transplantation of Autologous Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Complete and Chronic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. Brain Res. 2013, 1533, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Hua, R.; Dai, G.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; An, Y. Clinical Observation of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Treatment for Sequelae of Thoracolumbar Spinal Cord Injury. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kheir, W.A.; Gabr, H.; Awad, M.R.; Ghannam, O.; Barakat, Y.; Farghali, H.A.M.A.; El Maadawi, Z.M.; Ewes, I.; Sabaawy, H.E. Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Cell Therapy Combined with Physical Therapy Induces Functional Improvement in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury Patients. Cell Transpl. 2014, 23, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, M.V.P.; Larocca, T.F.; Souza, B.S.D.F.; Villarreal, C.F.; Silva, L.F.M.; Matos, A.C.; Novaes, M.A.; Bahia, C.M.P.; Martinez, A.C.D.O.M.; Kaneto, C.M.; et al. Safety and Neurological Assessments after Autologous Transplantation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Subjects with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, J.W.; Cho, T.H.; Park, D.H.; Lee, J.B.; Park, J.Y.; Chung, Y.G. Intrathecal Transplantation of Autologous Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treating Spinal Cord Injury: A Human Trial. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 2016, 39, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.K.; Choi, K.H.; Yoo, J.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Jeon, S.R. A Phase III Clinical Trial Showing Limited Efficacy of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury. Neurosurgery 2016, 78, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satti, H.S.; Waheed, A.; Ahmed, P.; Ahmed, K.; Akram, Z.; Aziz, T.; Satti, T.M.; Shahbaz, N.; Khan, M.A.; Malik, S.A. Autologous Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Transplantation for Spinal Cord Injury: A Phase I Pilot Study. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, J.; Zurita, M.; Rico, M.A.; Bonilla, C.; Aguayo, C.; Montilla, J.; Bustamante, S.; Carballido, J.; Marin, E.; Martinez, F.; et al. An Approach to Personalized Cell Therapy in Chronic Complete Paraplegia: The Puerta de Hierro Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, T.F.; Macêdo, C.T.; de Freitas Souza, B.S.; Andrade-Souza, Y.M.; Villarreal, C.F.; Matos, A.C.; Silva, D.N.; da Silva, K.N.; de Souza, C.L.e.M.; da Silva Paixão, D.; et al. Image-Guided Percutaneous Intralesional Administration of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Subjects with Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Study. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, J.; Zurita, M.; Rico, M.A.; Bonilla, C.; Aguayo, C.; Fernández, C.; Tapiador, N.; Sevilla, M.; Morejón, C.; Montilla, J.; et al. Repeated Subarachnoid Administrations of Autologous Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Supported in Autologous Plasma Improve Quality of Life in Patients Suffering Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, J.; Zurita, M.; Rico, M.A.; Aguayo, C.; Bonilla, C.; Marin, E.; Tapiador, N.; Sevilla, M.; Vazquez, D.; Carballido, J.; et al. Intrathecal Administration of Autologous Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: Safety and Efficacy of the 100/3 Guideline. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Li, W.; Wang, K. Therapeutic Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 13, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Albu, S.; Kumru, H.; Coll, R.; Vives, J.; Vallés, M.; Benito-Penalva, J.; Rodríguez, L.; Codinach, M.; Hernández, J.; Navarro, X.; et al. Clinical Effects of Intrathecal Administration of Expanded Wharton Jelly Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Patients with Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Study. Cytotherapy 2021, 23, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honmou, O.; Yamashita, T.; Morita, T.; Oshigiri, T.; Hirota, R.; Iyama, S.; Kato, J.; Sasaki, Y.; Ishiai, S.; Ito, Y.M.; et al. Intravenous Infusion of Auto Serum-Expanded Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Spinal Cord Injury Patients: 13 Case Series. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021, 203, 106565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Pang, M.; Du, C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Wang, N.X.; Zhang, L.M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Mo, J.; Dong, J.W.; et al. Repeated Subarachnoid Administrations of Allogeneic Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: A Phase 1/2 Pilot Study. Cytotherapy 2021, 23, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.; Pahwa, B.; Agrawal, D.; Singh, P.K.; Gujjar, H.; Mishra, S.; Jagdevan, A.; Misra, M.C. Efficacy and Outcome of Bone Marrow Derived Stem Cells Transplanted via Intramedullary Route in Acute Complete Spinal Cord Injury—A Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 100, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bydon, M.; Qu, W.; Moinuddin, F.M.; Hunt, C.L.; Garlanger, K.L.; Reeves, R.K.; Windebank, A.J.; Zhao, K.D.; Jarrah, R.; Trammell, B.C.; et al. Intrathecal Delivery of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: Phase I Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awidi, A.; Al Shudifat, A.; El Adwan, N.; Alqudah, M.; Jamali, F.; Nazer, F.; Sroji, H.; Ahmad, H.; Al-Quzaa, N.; Jafar, H. Safety and Potential Efficacy of Expanded Mesenchymal Stromal Cells of Bone Marrow and Umbilical Cord Origins in Patients with Chronic Spinal Cord Injuries: A Phase I/II Study. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, M.; Imagama, S.; Nakashima, H.; Ito, S.; Segi, N.; Ouchida, J.; Suda, K.; Harmon Matsumoto, S.; Komatsu, M.; Endo, T.; et al. Safety and Feasibility of Intravenous Administration of a Single Dose of Allogenic-Muse Cells to Treat Human Cervical Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, R.; Sasaki, M.; Iyama, S.; Kurihara, K.; Fukushi, R.; Obara, H.; Oshigiri, T.; Morita, T.; Nakazaki, M.; Namioka, T.; et al. Intravenous Infusion of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells Expanded in Auto Serum for Chronic Spinal Cord Injury Patients: A Case Series. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macêdo, C.T.; de Freitas Souza, B.S.; Villarreal, C.F.; Silva, D.N.; da Silva, K.N.; de Souza, C.L.e.M.; da Silva Paixão, D.; da Rocha Bezerra, M.; da Silva Moura Costa, A.O.; Brazão, E.S.; et al. Transplantation of Autologous Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Complete Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1451297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, N.; Kabatas, S.; Civelek, E.; Savrunlu, E.C.; Akkoc, T.; Boyalı, O.; Öztürk, E.; Can, H.; Genc, A.; Karaöz, E. Multiroute Administration of Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury: A Phase I Safety and Feasibility Study. World J. Stem Cells 2025, 17, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Shim, Y.S.; Ha, Y.; Yoon, S.H.; Park, S.R.; Choi, B.H.; Park, H.S. Treatment of Complete Spinal Cord Injury Patients by Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Transplantation and Administration of Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor. Tissue Eng. 2005, 11, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callera, F. Delivery of Autologous Bone Marrow Precursor Cells into the Spinal Cord Via Lumbar Puncture Technique in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. Blood 2005, 106, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syková, E.; Homola, A.; Mazanec, R.; Lachmann, H.; Konrádová, Š.L.; Kobylka, P.; Pádr, R.; Neuwirth, J.; Komrska, V.; Vávra, V.; et al. Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation in Patients with Subacute and Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Transpl. 2006, 15, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.H.; Shim, Y.S.; Park, Y.H.; Chung, J.K.; Nam, J.H.; Kim, M.O.; Park, H.C.; Park, S.R.; Min, B.-H.; Kim, E.Y.; et al. Complete Spinal Cord Injury Treatment Using Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Transplantation and Bone Marrow Stimulation with Granulocyte Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor: Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 2066–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deda, H.; İnci, M.; Kürekçi, A.; Kayıhan, K.; Özgün, E.; Üstünsoy, G.; Kocabay, S. Treatment of Chronic Spinal Cord Injured Patients with Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: 1-Year Follow-Up. Cytotherapy 2008, 10, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffner, L.F.; Santacruz, P.; Izurieta, M.; Flor, L.; Maldonado, B.; Auad, A.H.; Montenegro, X.; Gonzalez, R.; Silva, F. Administration of Autologous Bone Marrow Stem Cells into Spinal Cord Injury Patients via Multiple Routes Is Safe and Improves Their Quality of Life: Comprehensive Case Studies. Cell Transpl. 2008, 17, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraman, M.; Bingi, S.K.; Muthu, S.; Jeyaraman, N.; Packkyarathinam, R.P.; Ranjan, R.; Sharma, S.; Jha, S.K.; Khanna, M.; Rajendran, S.N.S.; et al. Impact of the Process Variables on the Yield of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Viejo, M.; Menendez-Menendez, Y.; Blanco-Gelaz, M.A.; Ferrero-Gutierrez, A.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, M.A.; Gala, J.; Otero-Hernandez, J. Quantifying Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Mononuclear Cell Fraction of Bone Marrow Samples Obtained for Cell Therapy. Transpl. Proc. 2013, 45, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Burns, S.P.; Graves, D.E.; Guest, J.; Jones, L.; Read, M.S.; Rodriguez, G.M.; Schuld, C.; Tansey, K.E.; et al. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord InjuryRevised 2019. Top. Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2021, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C.S.; Nori, S.; Tetreault, L.; Wilson, J.; Kwon, B.; Harrop, J.; Choi, D.; Fehlings, M.G. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury—Repair and Regeneration. Clin. Neurosurg. 2017, 80, S22–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.S.; Lee, B.S.; Ditunno, J.F.; Tessler, A. Patient Selection for Clinical Trials: The Reliability of the Early Spinal Cord Injury Examination. J. Neurotrauma 2003, 20, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evaniew, N.; Sharifi, B.; Waheed, Z.; Fallah, N.; Ailon, T.; Dea, N.; Paquette, S.; Charest-Morin, R.; Street, J.; Fisher, C.G.; et al. The Influence of Neurological Examination Timing within Hours after Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries: An Observational Study. Spinal Cord. 2020, 58, 247–254, Correction in Spinal Cord. 2020, 58, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, R.; Agrawal, A. Management of Spinal Injuries in a Patient with Polytrauma. J. Orthop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2013, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, P.; Morrison, S.A.; McDowell, S.; Vazquez, L. Using the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III to Measure Functional Recovery in a Post-Acute Spinal Cord Injury Program. Spinal Cord 2009, 48, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, H.L.; Hancock, D.O.; Hyslop, G.; Melzak, J.; Michaelis, L.S.; Ungar, G.H.; Vernon, J.D.S.; Walsh, J.J. The Value of Postural Reduction in the Initial Management of Closed Injuries of the Spine with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia. Spinal Cord. 1969, 7, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Shao, J.; Hu, X.; Xu, W.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ge, W.; Zhang, K.; et al. Temporal and Spatial Cellular and Molecular Pathological Alterations with Single-Cell Resolution in the Adult Spinal Cord after Injury. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 65, Correction in Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjani, N.; Deska-Gauthier, D.; Hachem, L.D.; Abramian, M.; Fehlings, M.G. Neuroplasticity and Regeneration after Spinal Cord Injury. N. Am. Spine Soc. J. (NASSJ) 2023, 15, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvan, M.; Meknatkhah, S.; Hassannejad, Z.; Sharif-Alhoseini, M.; Zadegan, S.A.; Shokraneh, F.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Lu, Y.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Time-Dependent Microglia and Macrophages Response after Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Rat: A Systematic Review. Injury 2020, 51, 2390–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badhiwala, J.H.; Wilson, J.R.; Witiw, C.D.; Harrop, J.S.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Aarabi, B.; Grossman, R.G.; Geisler, F.H.; Fehlings, M.G. The Influence of Timing of Surgical Decompression for Acute Spinal Cord Injury: A Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient Data. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C.S.; Badhiwala, J.H.; Fehlings, M.G. “Time Is Spine”: The Importance of Early Intervention for Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.R.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Wanyan, P. What Is the Optimal Timing of Transplantation of Neural Stem Cells in Spinal Cord Injury? A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis Based on Animal Studies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 855309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiani, Z.; Chipman, D.E.; Ryan, T.J.; Haider, M.N.; Kowalski, D.; Hasanspahic, B.; Scott, M.M.; Vallee, E.K.; Lucasti, C. Efficacy of Mesenchymal and Embryonic Stem Cell Therapy for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Studies. Glob. Spine J. 2025, 15, 3969–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Yan, F.; Sun, J.; Zhang, T. Assessment of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1532219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.; Dyck, S.M.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 441408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofano, F.; Boido, M.; Monticelli, M.; Zenga, F.; Ducati, A.; Vercelli, A.; Garbossa, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: Current Options, Limitations, and Future of Cell Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Yu, K.; Yang, L. A Comparative Study of Different Stem Cell Transplantation for Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2022, 159, e232–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, E.; Olenic, M.; De Vlieghere, E.; De Smet, S.; Devriendt, B.; Thorrez, L.; De Schauwer, C. Donor Age and Breed Determine Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Characteristics. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.-H.; Kang, B.-J.; Park, S.-S.; Kim, Y.; Sung, G.-J.; Woo, H.-M.; Kim, W.H.; Kweon, O.-K. Comparison of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Fat, Bone Marrow, Wharton’s Jelly, and Umbilical Cord Blood for Treating Spinal Cord Injuries in Dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2012, 74, 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yea, J.-H.; Kim, Y.; Jo, C.H. Comparison of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Bone Marrow, Umbilical Cord Blood, and Umbilical Cord Tissue in Regeneration of a Full-Thickness Tendon Defect in Vitro and in Vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 34, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewska, A.; Dabrowska, S.; Lukomska, B.; Janowski, M.; Andrzejewska, A.; Dabrowska, S.; Lukomska, B.; Janowski, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Neurological Disorders. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaković, J.; Šerer, K.; Barišić, B.; Mitrečić, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Neurological Disorders: The Light or the Dark Side of the Force? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1139359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namestnikova, D.D.; Kovalenko, D.B.; Pokusaeva, I.A.; Chudakova, D.A.; Gubskiy, I.L.; Yarygin, K.N.; Baklaushev, V.P. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. J. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug, M.; Švajger, U.; Lezaić, L.; Sočan, A.; Sever, M.; Zver, S.; Bajrović, F. Homing of Mesenchymal Stem Cells after Acute Traumatic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury—A Case Report. Cytotherapy 2020, 22, S89–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Diaz, M.; Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; Sanabria de la Torre, R.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Sierra-Sánchez, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Biodistribution of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells after Administration in Animal Models and Humans: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, P.; Vackova, I.; Ruzicka, J.; Zaviskova, K.; Dubisova, J.; Koci, Z.; Turnovcova, K.; Urdzikova, L.M.; Kubinova, S.; Rehak, S.; et al. The Effect of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Wharton’s Jelly in Spinal Cord Injury Treatment Is Dose-Dependent and Can Be Facilitated by Repeated Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; He, F.; Cao, Z.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Rosei, F.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Laden Hydrogel Microfibers for Promoting Nerve Fiber Regeneration in Long-Distance Spinal Cord Transection Injury. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baklaushev, V.P.; Bogush, V.G.; Kalsin, V.A.; Sovetnikov, N.N.; Samoilova, E.M.; Revkova, V.A.; Sidoruk, K.V.; Konoplyannikov, M.A.; Timashev, P.S.; Kotova, S.L.; et al. Tissue Engineered Neural Constructs Composed of Neural Precursor Cells, Recombinant Spidroin and PRP for Neural Tissue Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutepfa, A.R.; Hardy, J.G.; Adams, C.F. Electroactive Scaffolds to Improve Neural Stem Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury. Front. Med. Technol. 2022, 4, 693438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefifard, M.; Maleki, S.N.; Askarian-Amiri, S.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Chapman, J.R.; Fehlings, M.G.; Hosseini, M.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. A Combination of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Scaffolds Promotes Motor Functional Recovery in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2019, 32, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, F.; Xiao, Z.; Han, G.; Wang, N.; Yin, N.; Chen, B.; Jiang, X.; Yun, C.; Han, W.; et al. Clinical Study of Neuroregen Scaffold Combined with Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Repair of Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Transpl. 2017, 26, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasceno, P.K.F.; de Santana, T.A.; Santos, G.C.; Orge, I.D.; Silva, D.N.; Albuquerque, J.F.; Golinelli, G.; Grisendi, G.; Pinelli, M.; Ribeiro dos Santos, R.; et al. Genetic Engineering as a Strategy to Improve the Therapeutic Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Regenerative Medicine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Huang, F.; Wang, W.; Xie, Y.; Wang, B. Interleukin-10 Genetically Modified Clinical-Grade Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Markedly Reinforced Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury via Directing Alternative Activation of Macrophages. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Tao, Z.; Yu, M.; Sun, C.; Ye, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing Neuropeptide S Promote the Recovery of Rats with Spinal Cord Injury by Activating the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β Signaling Pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, R.; Ban, Y.; Zhang, W.; Kong, N.; Tang, J.; Ma, B.; Shao, Y.; Jin, R.; Sun, L.; et al. EPO Modified MSCs Protects SH-SY5Y Cells against Ischemia/Hypoxia-Induced Apoptosis via REST-Dependent Epigenetic Remodeling. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, C.; Xia, Z.; Wang, X.; Dai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y. Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Treatment for Acute Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on Preclinical Evidence. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1447414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; He, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, N.; Rong, L.; Liu, B. Exosomes Derived from MiR-26a-Modified MSCs Promote Axonal Regeneration via the PTEN/AKT/MTOR Pathway Following Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, Q. MTOR Pathway: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Spinal Cord Injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145, 112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namestnikova, D.D.; Cherkashova, E.A.; Sukhinich, K.K.; Gubskiy, I.L.; Leonov, G.E.; Gubsky, L.V.; Majouga, A.G.; Yarygin, K.N. Combined Cell Therapy in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraee-Yazdani, S.; Akhlaghpasand, M.; Golmohammadi, M.; Hafizi, M.; Zomorrod, M.S.; Kabir, N.M.; Oraee-Yazdani, M.; Ashrafi, F.; Zali, A.; Soleimani, M. Combining Cell Therapy with Human Autologous Schwann Cell and Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Patients with Subacute Complete Spinal Cord Injury: Safety Considerations and Possible Outcomes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.; Mo, H.; Han, H.; Rim, Y.A.; Ju, J.H. Stepwise Combined Cell Transplantation Using Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Motor Neuron Progenitor Cells in Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.M.; Rim, Y.A.; Sung, Y.C.; Nam, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.; Jung, S.I.; Lim, J.; et al. Combination of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Motor Neuron Progenitor Cells with Irradiated Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor over-Expressing Engineered Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhanced Restoration of Axonal Regeneration in a Chronic Spinal Cord Injury Rat Model. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalif, J.I.; Chavarro, V.S.; Mensah, E.; Johnston, B.; Fields, D.P.; Chalif, E.J.; Chiang, M.; Sutton, O.; Yong, R.; Trumbower, R.; et al. Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation for Spinal Cord Injury in Humans: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Z.; Qin, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, K. Synergistic Effects of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells/Neural Stem Cells and Epidural Electrical Stimulation on Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).