Abstract

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most prevalent paediatric extracranial solid tumour, which remains a major therapeutic challenge, especially in cases of recurrent and disseminated disease. c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) are increasingly evidenced to play a key role in NB tumourigenesis and progression through apoptosis regulation, making selective JNK inhibitors promising candidates for use in targeted anticancer drugs in NB. Our study comprehensively investigated the acute antineoplastic potential of the selective JNK inhibitor AS601245 (JNK inhibitor V) on the human MYCN-non-amplified neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y, with particular focus on its effects on NB cell viability, proliferation, migration, apoptosis, gene and protein expression, and mitochondrial metabolism. JNK V selectively impaired NB cell survival and function, without exerting cytotoxicity toward normal human Schwann cells (HSC) and fibroblasts (BJ). Our findings highlighted a dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation (XTT assay), colony formation (clonogenic assay), and migration (wound healing assay), accompanied by increased caspase-3 activity (caspase-3 assay), pro-apoptotic genes (qRT-PCR) and protein (Western blotting) expression, and significant disruption of both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis (Agilent Seahorse XF Assay). These results provide new insights into the therapeutic potential of JNK inhibition as a targeted strategy for NB.

1. Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most frequently occurring paediatric extracranial solid tumour, constituting up to 15% of all cancer deaths in children [1]. NB is an embryonal neuroendocrine neoplasm of the sympathetic nervous system, originating from neural crest progenitor cells, which undergo maladaptive differentiation because of genomic and epigenetic defects [2]. MYCN oncogene amplification is the first independent prognostic factor indicating poor clinical outcomes of NB patients. However, it occurs in only approximately 18% of neuroblastoma patients, while nearly 80% present with single-copy MYCN—a subgroup that includes low- and intermediate-risk NB and remains comparatively less explored [3,4]. Given this clinical distribution, our primary aim was to directly address this research gap and investigate the effects of the JNK inhibitor in the context of the more prevalent MYCN-non-amplified disease, relevant to the broad majority of NB patients [5].

Treatment of NB remains challenging because of its high genetic, immunological, and clinical heterogeneity, suboptimal response to initial therapy, high risk of relapse, and growing chemoresistance of tumour cells [6,7,8]. One promising therapeutic strategy against NB is the pharmacological inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), as they converge on many pathways and are considered the main regulators of apoptosis in tumours [9,10,11,12,13].

JNKs constitute a group of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs) that regulate cancer cell survival and apoptosis [14,15]. MAPK8, MAPK9, and MAPK10 genes encode the three JNK isoforms, respectively, JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3, which were reported to have multifaceted roles [16,17,18]. The experimental studies on NB indicated that the JNK1 isoform performs a pro-proliferative role, while JNK2 and JNK3 are assumed to play a pro-apoptotic role [19,20]. JNKs control the expression of cell cycle-, apoptosis-, mitochondria-, and ER stress-related genes, playing a crucial role in executing cell death in response to various apoptotic stimuli, both transcriptionally and through transcription-independent mechanisms [21,22]. JNKs undergo mitotic translocation, which results in the discharge of cytochrome c (Cyt c) and the Second Mitochondria-derived Activator of Caspase (SMAC), both of which directly induce apoptosis [21]. However, the precise mechanism of the JNK pathway’s role has not been fully elucidated in terms of NB.

Although JNK is known as a well-evidenced apoptosis kinase, under specific stress conditions in the tumours, in which JNK is overexpressed, it may evoke a paradoxical effect and contribute to cancer cell survival and chemotherapy resistance and the inhibition of cancer cell apoptosis [12,22]. Emerging evidence indicated that transiently activated JNK promotes cancer cell survival by modulating JNK-Bcl-2/Bcl-xL-Bax/Bak- as well as Cyt-C/caspase-3-dependent pathways [19,23,24]. Studies have demonstrated that both genetic inactivation of JNK signalling and specific pharmacological JNK inhibition can suppress tumorigenesis [25,26]. Hence, multiple JNK inhibitors have recently been widely investigated as a potential anticancer treatment, alone and in combination with chemotherapy [27,28]. Recent data indicated the enormous potential of JNK inhibitors in NB treatment, as they have been reported to induce NB cell death via direct activation of p53-, JNK-, Bcl-2-, and caspase-dependent pathways [29,30].

Based on available evidence, this is the first comprehensive study that investigates the antineoplastic effect of JNK inhibition in the NB in vitro model, a SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line, using the pharmacological inhibition of JNK signalling by JNK inhibitor AS601245 (JNK inhibitor V, JNK V). This selective small-molecule inhibitor exerts the strongest effect on the least-studied isoform, JNK3, which is hypothesised as a target in NB due to its expression in neuronal tissue and potential molecular involvement in apoptosis and oxidative stress response [19,31]. The study provides novel preclinical evidence supporting the further development of JNK inhibitors in the treatment of NB.

2. Results

2.1. Evaluation of the Cellular Toxicity of the JNK Inhibition on SH-SY5Y, HSC, and BJ Cells

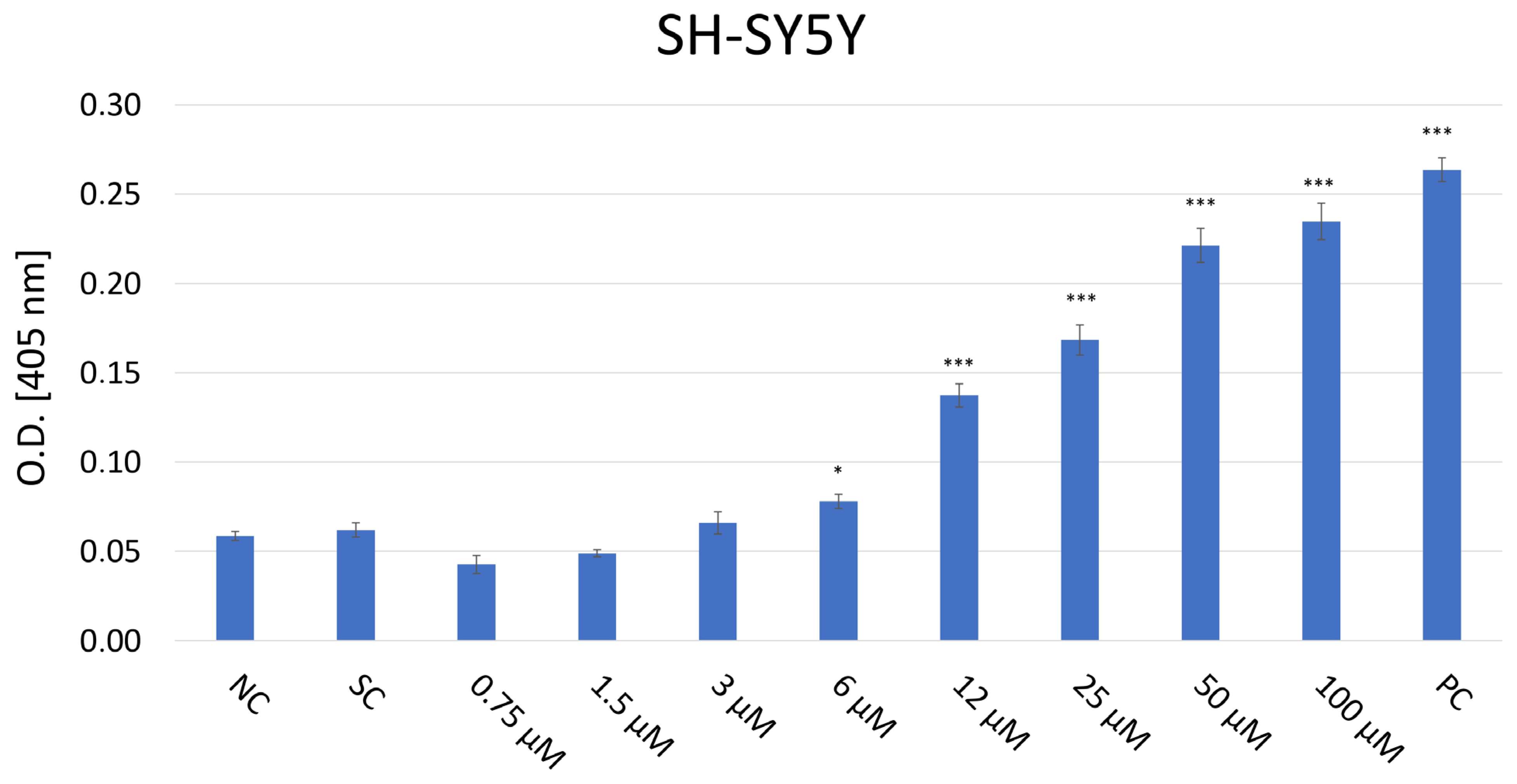

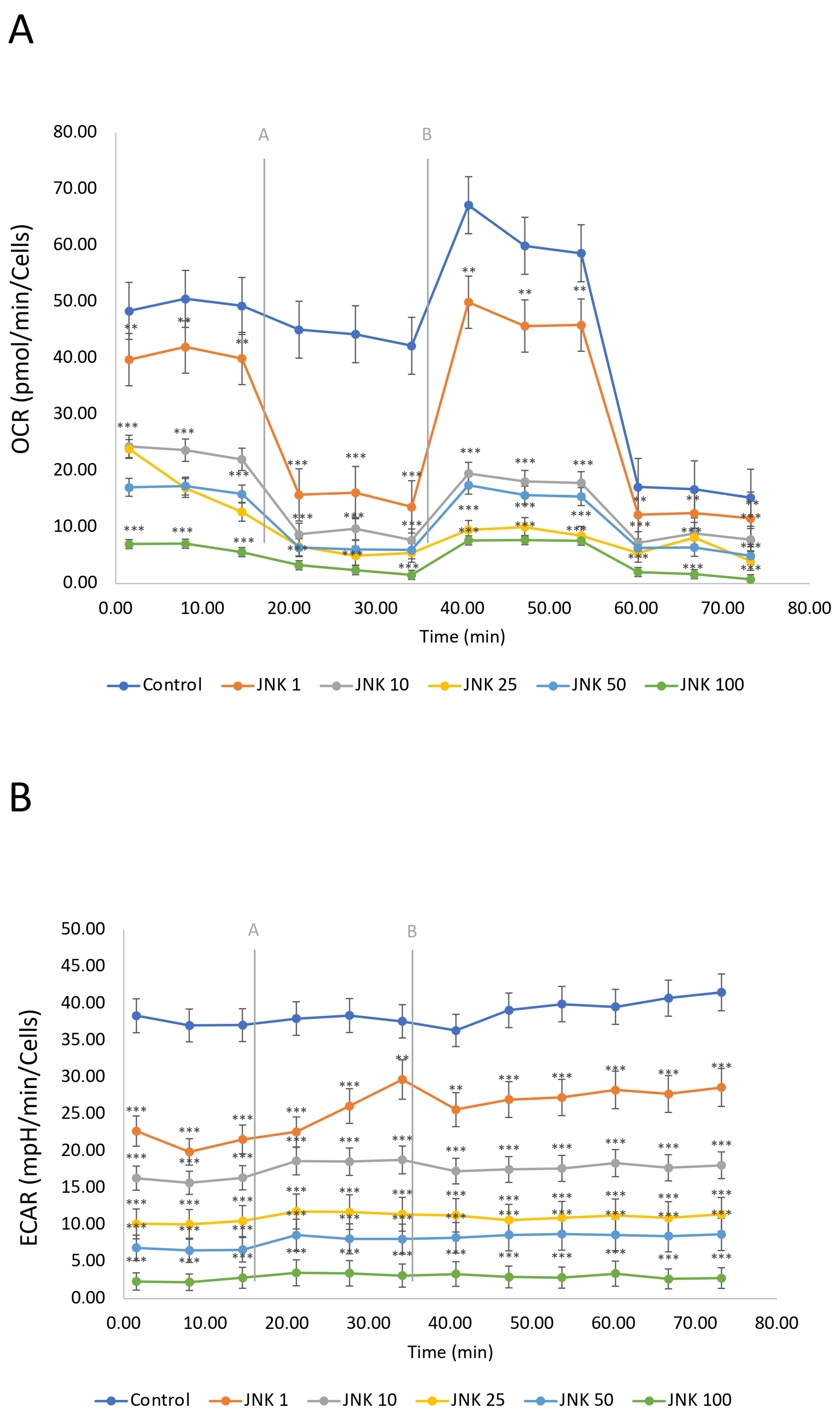

The cytotoxic effect of JNK V on three cell lines was evaluated using a colorimetric XTT assay (Figure 1). The cells were then treated and incubated with a particular compound for 24 h to assess the acute short-term effects of the investigated compound. The cytotoxicity experiment revealed significant inhibition of the proliferation of SH-SY5Y cells following the 24 h incubation with JNK V at concentrations ≥ 0.75 µM compared with the negative control. The cytotoxic effect was significant, and SH-SY5Y cells’ viability was reduced by almost 60% at 12 µM JNK V. In our experiment on SH-SY5Y cells, the IC50 of JNK V was 9 μM after 24 h of incubation. Therefore, the particular JNK V concentration ranges for all further experiments were determined based on XTT assay results, using the methods’ dedicated specifications. Low concentrations of JNK V (0.1–3 μM), reducing cell viability up to 30% after 24 h, were chosen for migration experiments, moderate concentrations for clonogenic assay (0.19–25 μM) and mRNA expression analysis (1–25 μM), and higher concentrations for caspase-3 activity assessment (0.75–100 μM), protein expression, and mitochondrial function analysis (1–100 μM). A solvent for JNK V, 0.01% DMSO, did not induce significant toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h of incubation compared to the negative control. Furthermore, on normal cell lines, HSC and BJ, the JNK V did not demonstrate a cytotoxic effect. Although in HSC, the decrease in cell viability at JNK V ≥ 6 μM was statistically significant compared to the negative control, the viability of HSCs at all tested concentrations was maintained ≥78%, which is above the ISO 10993-5 cytotoxicity threshold [32]. HSC is a primary glial cell line characterised by high sensitivity to treatment-induced stress, which may explain the observed but non-cytotoxic reduction in viability. Moreover, the viability of BJ fibroblasts, which are much more resilient cells, was not significantly affected by JNK V at all tested concentrations, nor at 0.01% DMSO. Therefore, the XTT assay revealed the selective cytotoxicity of JNK V toward NB cells.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the cytotoxicity of the JNK V inhibitor at 0.1–100 µM after incubation for 24 h toward SH-SY5Y (A), HSC (B), and BJ (C) cells performed by the XTT assay. NC—negative control (untreated cells); SC—solvent control (cells treated with 0.01% DMSO); PC—positive control (cells treated with 20% DMSO). All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (mean ± SD). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. negative control.

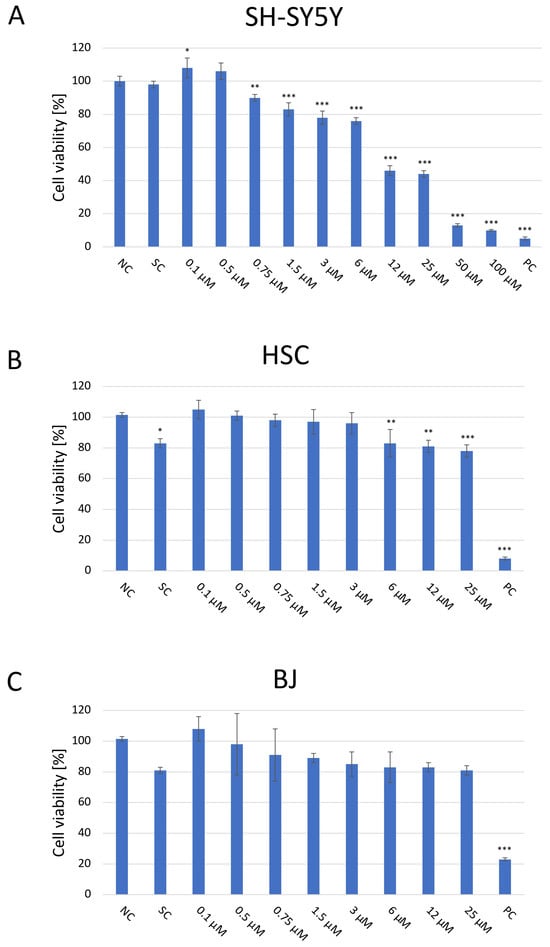

2.2. Evaluation of the Morphology of SH-SY5Y Cells After JNK Inhibition

The morphology of the cells exposed to JNK V, 0.01% DMSO, or 20% DMSO was assessed after 24 h of incubation using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 2). Untreated SH-SY5Y cells (negative control) exhibited a characteristic neuronal-like morphology with elongated neurites, an adherent and polygonal cell shape, and a homogenous cytoplasm. Cells treated with JNK V demonstrated concentration-dependent morphological alterations, from moderate shrinkage, the loosening of cell–cell contact, and neurite retraction at <3μM JNK V concentrations to increased cell detachment, loss of neurites, and nuclear condensation at 3–12 μM JNK V to loosening of the capacity to attach to the culture vessels and widespread cell lysis at JNK V > 12 μM. The results demonstrated a markedly visible impairment of the morphology of SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with JNK V at a wide concentration range, evidencing the cytotoxic effect of the compound on NB cells.

Figure 2.

Representative images of SH-SY5Y cells’ morphology after 24 h of incubation with JNK V inhibitor at 0.1–100 µM. NC—negative control (untreated cells); SC—solvent control (cells treated with 0.01% DMSO); PC—positive control (cells treated with 20% DMSO).

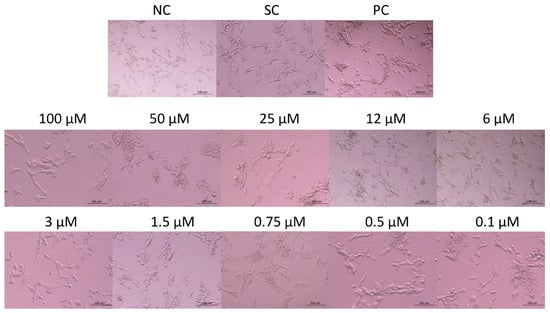

2.3. Evaluation of the Colony-Forming Abilities of SH-SY5Y Cells After JNK Inhibition

A clonogenic assay was performed in order to assess the proliferation and colony-forming abilities of SH-SY5Y cells, indicating their long-term reproductive capacity and overall viability after 2 weeks of incubation with JNK V at 0.1–25 μM (Figure 3). Untreated cells maintained undisturbed proliferation, reaching 100% confluence, and properly formed colonies. The assay results showed that JNK inhibition significantly impaired the proliferation and colony-forming abilities of SH-SY5Y cells in a dose-dependent manner, compared to untreated cells, which reached 47% confluence at the final time point. Cells exposed to JNK V, even at the very low concentration of 0.1 μM, reached 29% confluence, while the confluence of cells treated with JNK V concentrations ≥1.5 μM was <10% at the final time point. Treatment with the inhibitor at a high concentration of 25 µM completely suppressed the cells’ proliferation, calculated at 0.3% confluence, and led to no colony formation, indicating the strong cytotoxicity of the compound. The results showed the impairment of long-term proliferation and survival of SH-SY5Y cells by pharmacological JNK inhibition, showing its cytotoxic and antineoplastic potential against cancerous NB cells.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative images of proliferation and colony-forming abilities of SH-SY5Y cells incubated for 2 weeks with JNK V inhibitor at 0.1–25 µM by clonogenic assay; NC—negative control (untreated cells). Scale bar: 500 µm. (B) Evaluation of the confluence of new colonies formed; NC—negative control (untreated cells). All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (mean ± SD); *** p < 0.001 vs. negative control.

2.4. Evaluation of the Migratory Abilities of SH-SY5Y Cells After JNK Inhibition

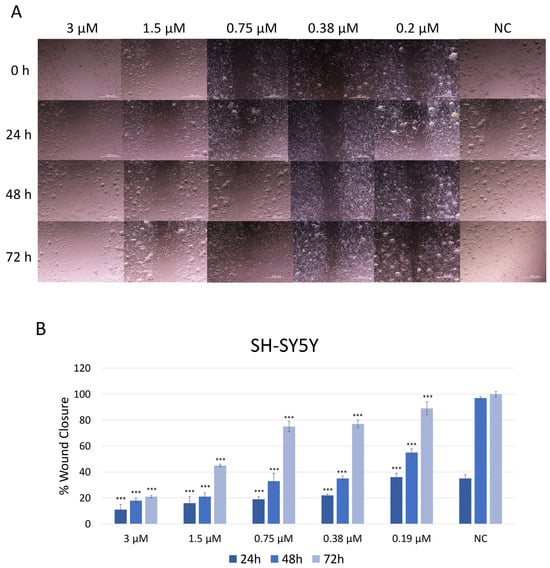

The effect of JNK V on the migration ability of SH-SY5Y cells was assessed using a wound healing (scratch) assay (Figure 4). Cells treated with JNK V at low and moderate concentrations (0.19 µM to 3 µM) closed the mechanically made scratch relatively more slowly compared to untreated cells. Phase-contrast microscopy revealed that inhibitor-treated cells retained their morphology but exhibited reduced motility, as indicated by fewer cells at the wound edges and a wider residual gap. In the control group (untreated cells), the wound area gradually decreased over time, with 38% wound closure after 24 h and almost complete wound closure (97%) after 48 h, indicating active cell migration. The treatment with JNK V at all tested concentrations resulted in significantly impaired cell migration across all time points, compared to negative control cells. At all tested JNK V concentrations, cells reached <60% wound closure after 48 h. SH-SY5Y cells reached only 21% of wound closure after 72 h of treatment with JNK V at 3 µM and less than 50% of wound closure after 72 h of incubation with 1.5 µM JNK V, indicating a strong anti-migratory effect of the inhibitor. These results suggest that JNK V effectively suppresses SH-SY5Y cells’ invasion abilities in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating the anti-migratory and further anti-metastatic potential of the pharmacological JNK inhibition in NB cells.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative images of SH-SY5Y cells’ migration by wound healing assay after treatment with JNK V inhibitor at 0.19 μM, 0.38 μM, 0.75 μM, 1.5 μM, and 3 μM concentrations. Photos were taken at particular timepoints: 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. (B) Evaluation of the percentage of wound closure. NC—negative control (untreated cells). All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (mean ± SD); *** p < 0.001 vs. negative control.

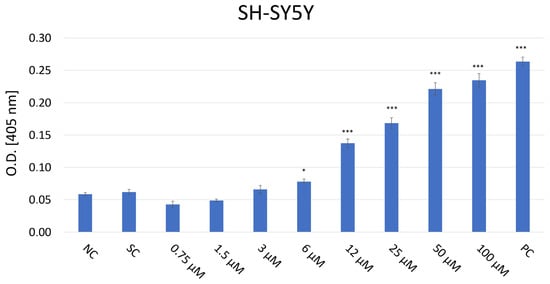

2.5. Evaluation of Caspase-3 Level in SH-SY5Y Cells After JNK Inhibition

The caspase-3 colorimetric activity assay was conducted to evaluate the activity of the caspase-3 enzyme as an indicator of apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells treated with JNK V inhibitor at a concentration range of 0.75–100 µM (Figure 5). Although JNK is typically known to activate caspase-3, its inhibition may paradoxically increase caspase-3 levels in particular cancer and neuronal cells under chronic stress conditions by disinhibiting other pro-apoptotic signals such as p38 or intrinsic mitochondrial pathways, triggering the activation of caspase-9 as well as downstream caspase-3 [33]. The absorbance of the chromogenic reaction product, p-nitroaniline (pNA), at 405 nm corresponds to the caspase-3 enzymatic activity in cells. The obtained results demonstrated a significant elevation in the caspase-3 activity level in cells treated with JNK V inhibitor ≥ 6 µM after 24 h of treatment, compared to the baseline level of caspase-3 in untreated cells. The absorbance values in untreated cells showed minimal caspase activity (O.D. = 0.055), whereas treatment with 100 μM of the inhibitor resulted in a 4.3-fold increase in enzyme activity (O.D. = 0.240). The result evidenced that pharmacological JNK inhibition promotes caspase-dependent apoptosis in NB cells.

Figure 5.

Analysis of caspase-3 level in SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h incubation with JNK V inhibitor at 0.75–100 µM by Caspase-3 colorimetric assay. The absorbance of the chromogenic reaction product values at 405 nm corresponds to the caspase-3 enzymatic activity. NC—negative control (untreated cells); SC—solvent control (cells treated with 0.01% DMSO); PC—positive control (cells treated with 10 µM staurosporine). All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks with Bonferroni t-test (mean ± SD); *** p < 0.001 and * p < 0.05 vs. negative control.

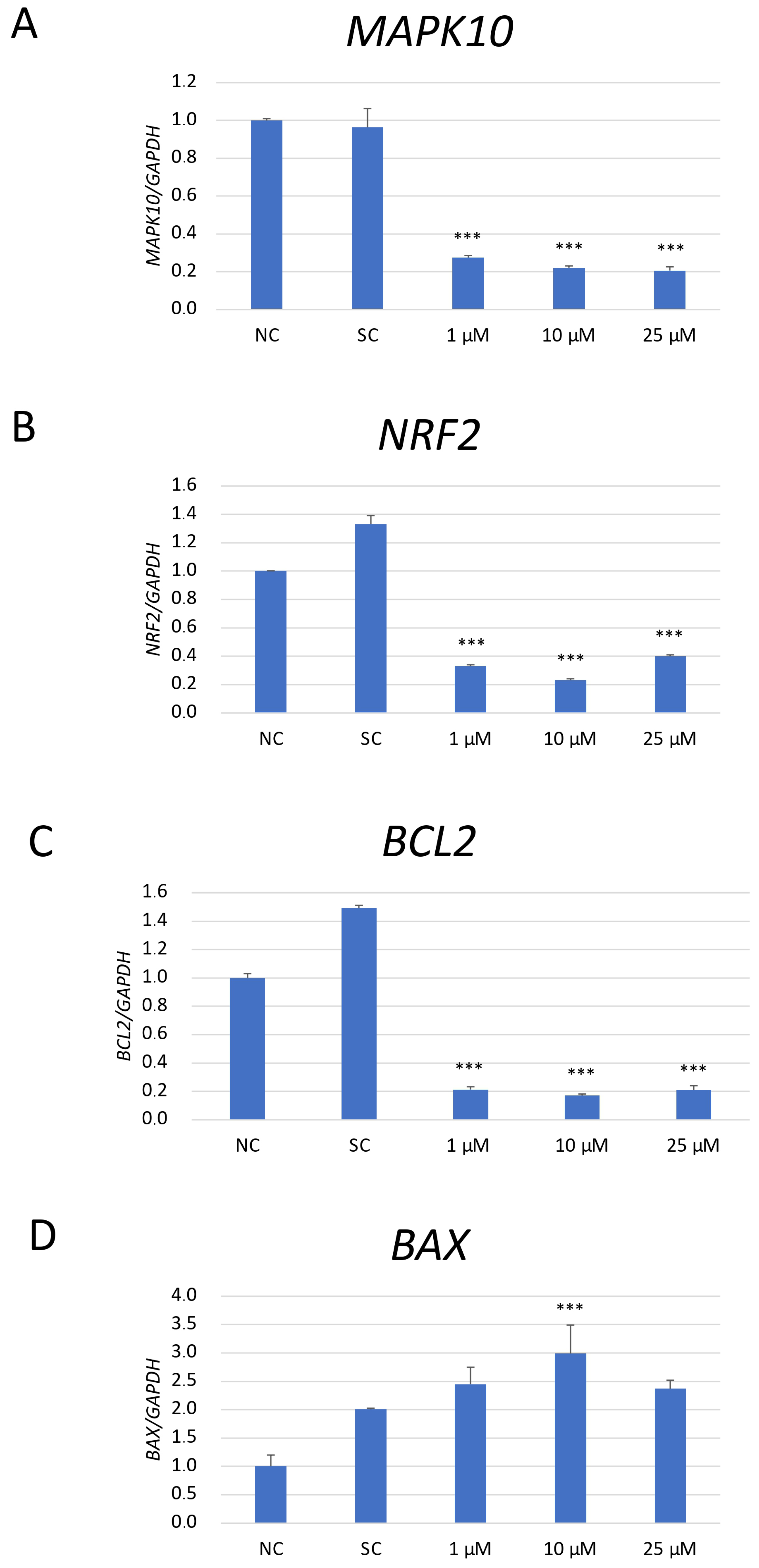

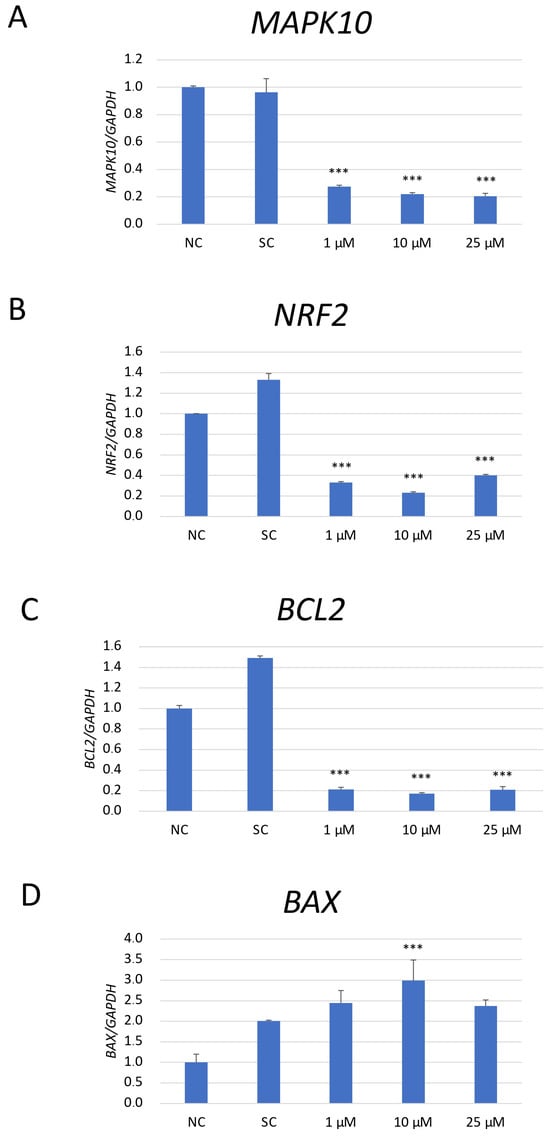

2.6. mRNA Expression Analysis of the Apoptosis-Related Genes in SH-SY5Y Cells After Pharmacological JNK Inhibition

The expression analysis of mRNA of genes associated with apoptosis (Mitogen-activated protein kinase 10/c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 (MAPK10/JNK3), B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), and BCL2-Associated X, Apoptosis Regulator (BAX)) and anti-oxidative response (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)) was performed in SH-SY5Y cells exposed to JNK V (1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM), 0.01% DMSO (solvent control), and untreated cells (negative control) (Figure 6). As NRF2 is a master regulator of antioxidant responses, and JNK can modulate oxidative stress response signalling, the changes in NRF2 mRNA expression could explain whether the observed anti-neoplastic effects could be related to oxidative stress regulation rather than only direct apoptotic signalling [33]. The obtained results have shown that the expression of MAPK10 mRNA, the less explored JNK isoform with an established neuroprotective effect on normal cells, was significantly reduced by all tested concentrations of JNK V compared to that in the negative control cells. JNK V in all tested concentrations caused a significant decline in the expression of anti-apoptotic BCL2 and a significant increase in the expression of pro-apoptotic BAX mRNA in comparison to that in the negative control. The expression of the master regulator of anti-oxidative responses, NRF2 mRNA, was significantly reduced by all tested concentrations of JNK V, indicating that JNK inhibition may impair SH-SY5Y resistance to oxidative stress by downregulating Nrf2-dependent protective mechanisms. These results suggest that JNK V modulates the expression of the chosen genes associated with apoptosis and oxidative stress response in SH-SY5Y cells, enhancing NB cell apoptosis.

Figure 6.

The mRNA depression levels of MAPK10 (A), NRF2 (B), BCL2 (C), and BAX (D) genes in SH-SY5Y cells treated with JNK at 1 μM, 10 μM, and 25 μM for 24 h. GAPDH was used as a reference gene. NC—negative control (untreated cells); SC—solvent control (cells treated with 0.01% DMSO). All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (mean ± SD); *** p < 0.001 vs. negative control.

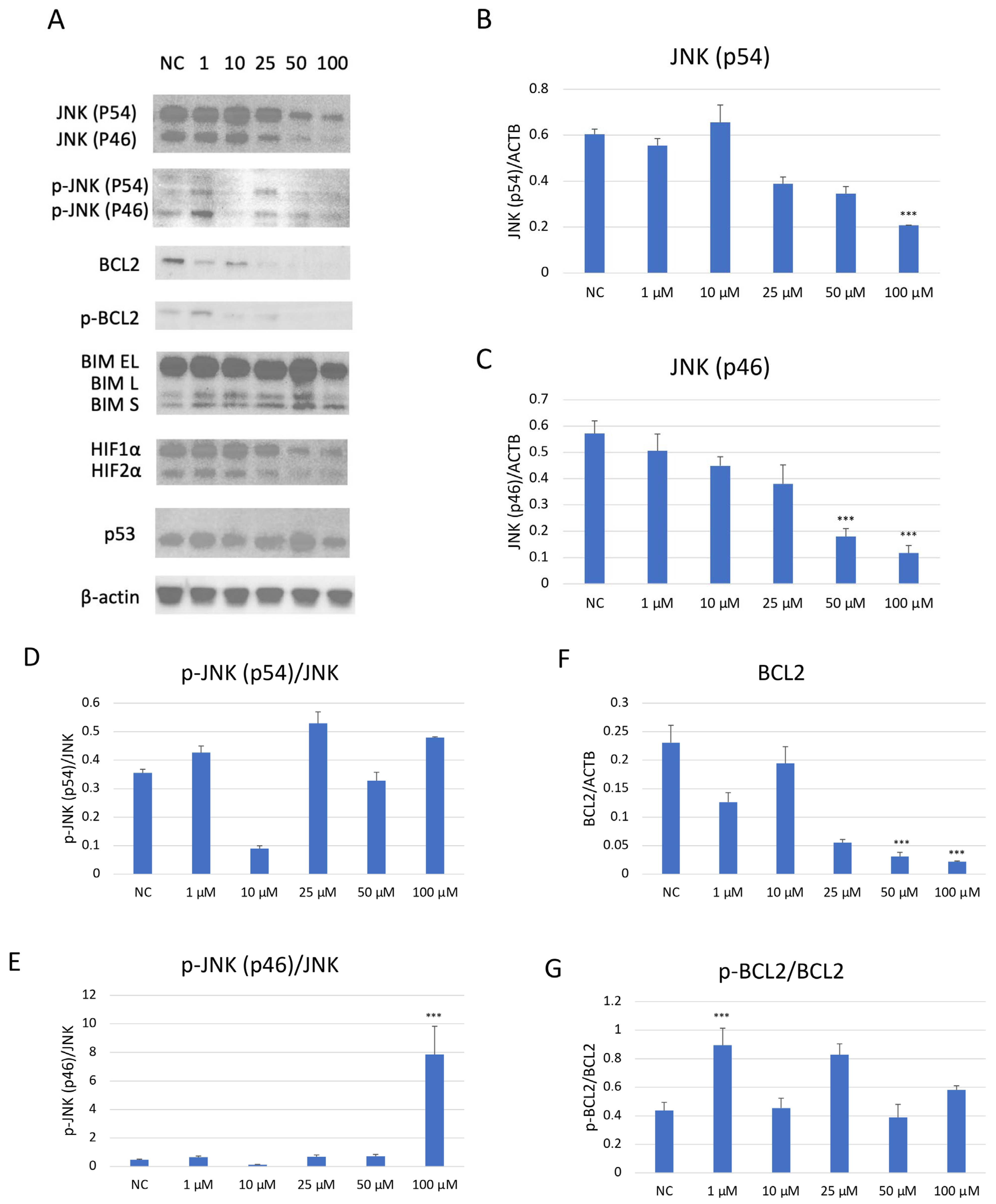

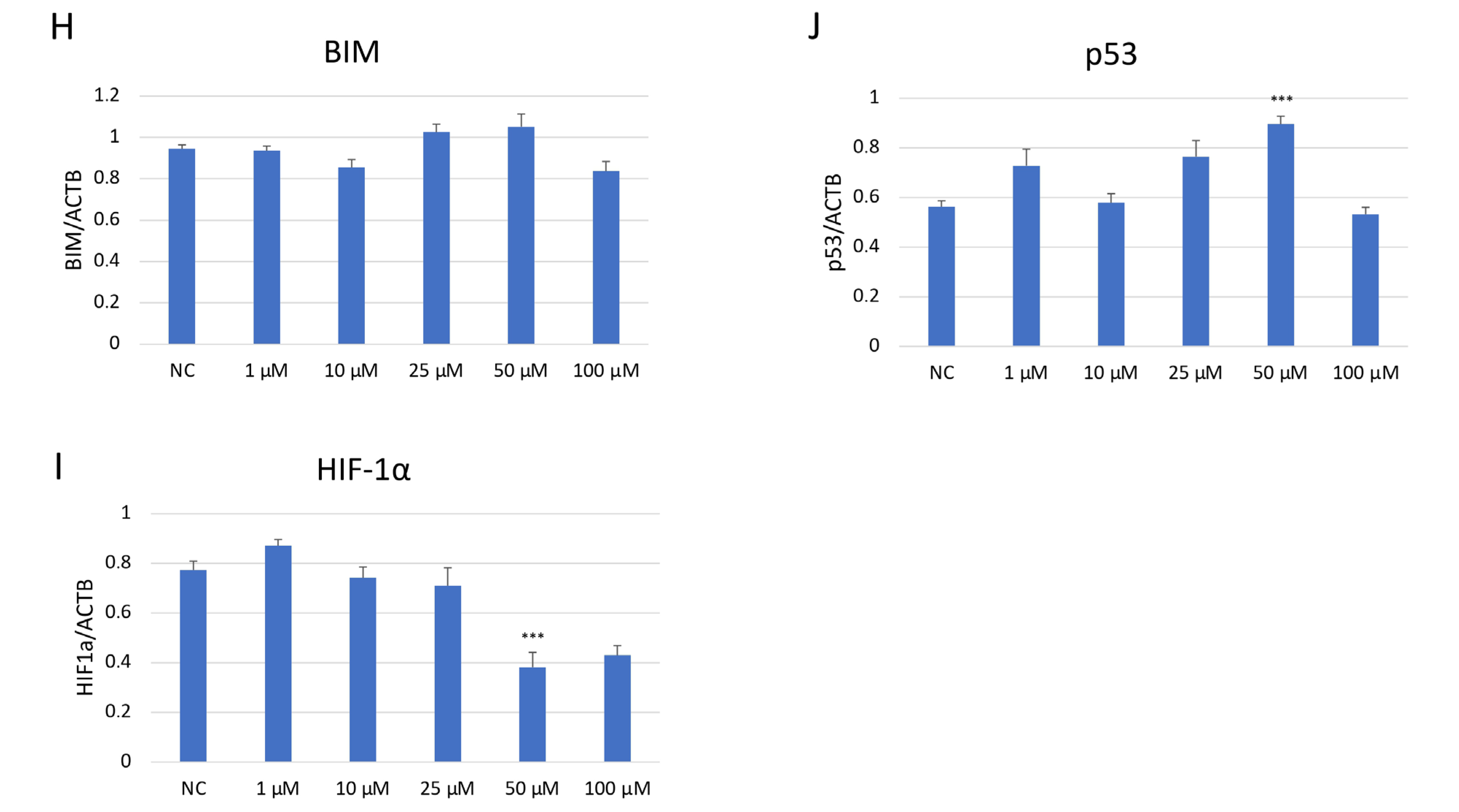

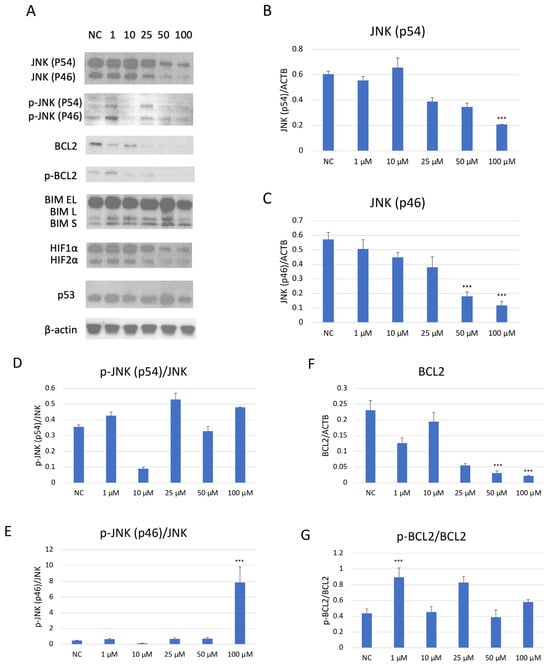

2.7. Evaluation of Apoptosis- and Cell Cycle-Related Protein Expression in SH-SY5Y Cells After JNK Pharmacological Inhibition

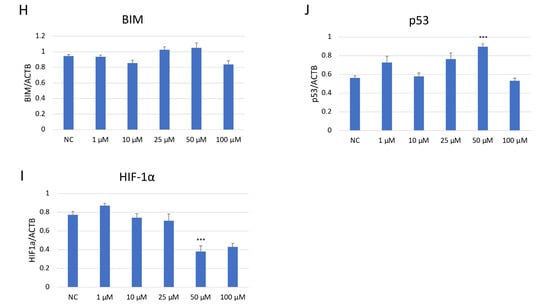

Western blot analysis demonstrated a dose-dependent suppression of JNK pathway activation in SH-SY5Y cells after JNK V treatment (Figure 7). The investigated compound treatment decreased both JNK isoforms p54 and p46 and modulated p-JNK isoform expression in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, the deregulation of chosen key apoptosis- and cell cycle-related protein expression in SH-SY5Y cells by JNK V was demonstrated. The expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 was significantly downregulated by JNK V at 50 and 100 µM, accompanied by a reduction in p-Bcl2 expression. The Bim expression levels after JNK V treatment were not changed significantly, but an increasing tendency of protein expression with higher concentrations of JNK V could be observed, which is consistent with a pro-apoptotic shift, since the Bcl-2 level is decreasing. The expression level of HIF-1α was reduced by all tested concentrations of JNK V, with statistical significance at 50 µM, suggesting a probable effect of JNK V on hypoxia-related signalling or stability. The p53 protein expression level was significantly increased after JNK V treatment at 50 µM, suggesting that the pro-survival p53 axis is affected by JNK inhibition under these conditions. The obtained results show that JNK signalling in SH-SY5Y cells can be pharmacologically blocked by JNK V to effectively suppress its downstream phosphorylation events and to promote an apoptotic molecular profile with reduced Bcl-2 signalling and increased p53 expression.

Figure 7.

Western blot analysis (A) of the expression level of proteins JNK (p54) (B), JNK (p46) (C), p-JNK (p54) (D), p-JNK (p46) (E), BCL2 (F), p-BCL2 (G), BIM (H), HIF-1α (I), and p53 (J) in SH-SY5Y cells treated with JNK V at concentrations 1–100 μM for 24 h. NC—negative control; 1, 10, 25, 50, 100—increasing concentrations of JNK V in µM; ACTB (β-actin) was used as a loading control. All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (mean ± SD). *** p < 0.001 vs. negative control.

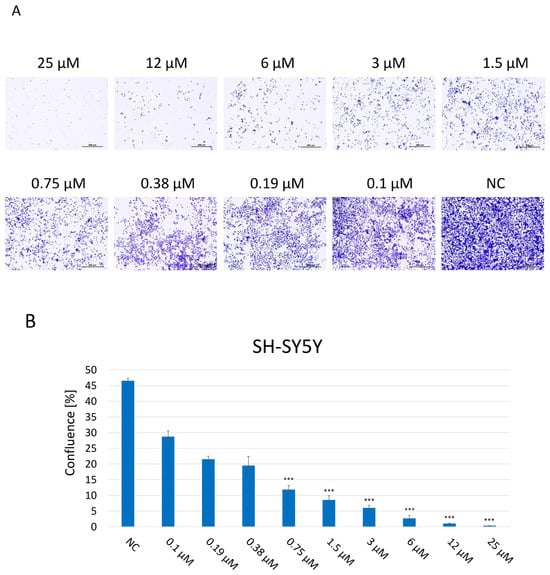

2.8. Evaluation of the Mitochondrial Metabolism of SH-SY5Y Cells After JNK Inhibition

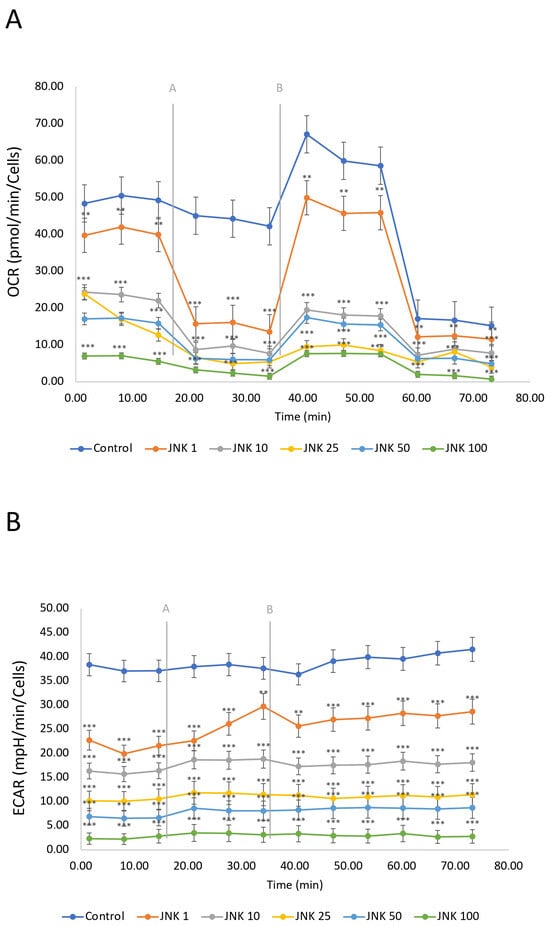

The mitochondrial respiration, including oxidative phosphorylation, defined as oxygen consumption rate (OCR), and glycolysis, defined as extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), was measured using the Seahorse Mitostress Assay (Figure 8). SH-SY5Y cells were treated with JNK V inhibitor (1–100 µM) for 24 h. The OCR of untreated cells (control) was the highest, indicating active mitochondrial respiration of the living cells. The modulation of OCR in untreated cells is a consequence of injections of the assay reagents. The ECAR in the control group was relatively high and stable, indicating active glycolysis. JNK V treatment showed a significant reduction in OCR in a concentration-dependent manner compared to the control, suggesting that JNK inhibition decreases mitochondrial respiration in a dose-dependent manner. Similarly to the OCR results, ECAR decreased with increasing JNK inhibitor concentrations. The drop in both OCR and ECAR suggests that JNK inhibition not only impairs ATP production via mitochondria but also limits the cells’ ability to compensate through glycolysis, ultimately leading to a significant metabolic disruption, preserving only residual OCR while treated with 100 μM JNK V. These findings suggest that JNK activity may be critical for maintaining both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis in SH-SY5Y cells.

Figure 8.

A real-time evaluation of mitochondrial bioenergetics—oxidative phosphorylation (A) and glycolysis (B) by Seahorse ATP Rate assay in SH-SY5Y cells treated with the JNK V inhibitor at 1 µM, 10 µM, 25 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM. Control—negative control (untreated cells); grey letters and lines represent the injections of oligomycin [A] and rotenone/antimycin A [B]. All experiments were run in triplicate. Statistics: Student’s t-test (mean ± SD). *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01 vs. negative control.

3. Discussion

The treatment of NB remains challenging because of its high genetic, immunological, and clinical heterogeneity; suboptimal response to initial therapy; high risk of relapse; and growing chemoresistance of tumour cells [6,7,8]. Therefore, the development of novel therapies should focus on increasing response rates to first-line therapies (chemo/immunotherapy), developing effective salvage therapies for relapsed and refractory disease, sustaining disease remissions, and enhancing antitumour immune function [34]. In infants, NB often regresses spontaneously or matures into ganglioneuroblastoma (GNB) after initial chemotherapy. However, the prognosis of NB patients becomes worse as patients age, and the current treatment standards remain ineffective in older patients and those with disseminated or recurrent disease. Despite advances in therapy, outcomes for high-risk patients remain poor [35,36].

MYCN oncogene amplification is the first independent prognostic factor indicating poor clinical outcomes of NB patients, observed in approximately 18% of cases, accounting for 40% of high-risk neuroblastomas [5,37]. The MYCN gene consistently promotes the progression of MYCN-related neuroendocrine tumours by driving dynamic spatial and temporal interactions, including distinct transcriptional programmes, DNA damage repair, resolving torsional stress, regulating R-loops, metabolic networks, stress–response, and apoptosis-related signalling patterns, and contributing to the aggressive phenotype of MYCN-amplified diseases [38,39]. However, despite the extensive study of MYCN-amplified NB, a gap in pre-clinical and clinical research of MYCN non-amplified cases was recently highlighted. New large-scale transcriptional subtyping analysis has suggested that MYCN non-amplified NBs are roughly heterogeneous and could be classified into three subgroups according to their transcriptional profiling [3]. Subgroup 2 had the worst prognosis, presenting an ‘MYCN’ signature that was potentially affected by overexpression of Aurora Kinase A (AURKA), while subgroup 3 showed an ‘inflamed’ immune-related gene signature. These findings emphasised the substantial extent of inner heterogeneity within the MYCN non-amplified population and show the vulnerability of stratified subgroups to different therapeutic approaches. Moreover, this research demonstrated active stress–response pathways and MAPK/JNK signalling within the subtype groups, underscoring that JNK pathway biology is not limited only to MYCN-amplified NB phenotypes. Consistent with this, JNK activity has been implicated in migration, invasion, and stress-induced apoptosis in both MYCN-amplified and MYCN-non-amplified neuroblastoma models [20,40]. Thus, although our study focuses on a non-amplified cell line, it addresses cellular mechanisms relevant to multiple NB subtypes.

Furthermore, NB with MYCN amplification exhibits both transcriptional and functional inhibition of JNK signalling, resulting in low basal JNK activity and a significantly impaired apoptotic response. Patient-specific modelling consistently places tumours with MYCN amplification in the low JNK activity cluster, and system-level reconstructions show systematic downregulation of upstream JNK circuits in MYCN-induced disease [41,42]. Notably, a newly published study has shown that high-risk tumours with MYCN amplification respond better to treatment regimens involving JNK-independent drugs, confirming that the JNK pathways are significantly silenced in this subtype [43]. Hence, JNK-dependent therapies are much more biologically relevant in MYCN-nonamplified neuroblastoma, where the JNK cascade remains intact.

Elevated JNK activity is an established contributor to malignancy progression and chemo/radiotherapy resistance in many cancers in which JNK is transiently activated, such as B-cell lymphoma, osteosarcoma, breast, lung, skin, and pancreatic cancer [13,27,44,45,46]. JNK exhibits pro-survival function in cancer cells due to its ability to enhance the processes of proliferation, migration, and invasion through a plethora of mechanisms, including synergistic action with p38 MAPKs and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), the upregulation of antiapoptotic gene expression such as BCL2, and the blockade of caspase activation [23,47,48,49]. Moreover, JNK induces pro-survival autophagy to counteract apoptosis, which, together with immune evasion mechanisms, increases the resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapy [50,51]. Therefore, JNK constitutes an interesting molecular anti-neoplastic target for therapeutic intervention with small-molecule kinase inhibitors [52]. Intriguingly, the JNK inhibitor AS602801, bentamapimod, was evidenced to block gap-junction communication between astrocytes and glioma cells [53], lung cancer stem cells [54], and breast cancer cells, and together with modulating Cx43 expression, it inhibited particular cancer metastasis to the brain [24]. Multiple JNK targeting strategies, including various ATP-competitive, non-kinase, and substrate-competitive inhibitors, have been developed and, due to the anticancer potential demonstrated in preclinical models, several JNK inhibitors have been investigated in the II/III phases of clinical trials [55,56]. However, JNK’s pleiotropic signalling limits the clinical application of direct JNK inhibition, as evidenced by past clinical trials primarily focused on fibrotic and inflammatory diseases [40,57,58,59,60].

The anticancer effects of the inhibition of the JNK signalling pathway have previously been successfully reported in diverse NB in vitro and in vivo models [61]. The newest data indicated an enormous potential of JNK inhibitors in NB treatment, as they have been reported to induce NB cell death via direct activation of p53, Bcl-2, and caspase-dependent pathways [27,62]. NSC697923, an inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N, promoted NB cell death by regulating both p53 and JNK pathways, apoptosis induction, and colony formation inhibition in a dose-dependent manner across multiple MYCN-amplified and MYCN-non-amplified NB cell lines [29]. The compound also demonstrated in vivo antineoplastic activity in NB orthotopic xenografts. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, suppressed cell growth and angiogenesis in SH-SY5Y and CHP126 NB cell lines by modulating the JNK pathway, while its combination with all-trans retinoic acid enhanced tumour growth inhibition in human NB xenografts and a mouse model [63,64,65]. Recently, a highly selective in vitro JNK3 Inhibitor, FMU200, was reported to decrease cell viability in SH-SY5Y cells [66,67]. The newest data showed that another selective JNK3 inhibitor, piceatannol, was highly effective in apoptosis induction by the inhibition of Cyt-C/ Bcl-2/caspase-3-dependent pathway, protecting SH-SY5Y cells from hypoxic insult [68,69]. The other possible mechanism of activity of JNK inhibitors in NB is a disruption in cancer stemness maintained by the STAT3-JNK axis, evidenced by the remarkably lower viability of IMR5, NLF, and SK-N-AS NB cell lines, and the downregulation of the expression of the stem cell marker CXCR4 after treatment with SP600125 or JNK-IN-8 inhibitors [70,71].

Our study is the first to comprehensively investigate the anti-neoplastic effect of AS601245 (JNK inhibitor V) on the SH-SY5Y cell line via a detailed assessment of the cellular effects of the compound on cell functions. JNK V demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in the proliferation of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) cells by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, accompanied by a reduction in c-Myc and Bcl-2 protein levels [72]. Moreover, JNK V significantly diminished the adhesion and migration of multiple human colon cancer cell lines through specific gene expression modulation [73,74,75]. Recent gene analysis has reported that the JNK V inhibitor also shows promise for use in breast cancer treatment [13,24]. However, the potential of JNK V has not yet been elucidated in any pre-clinical or clinical trials with regard to NB. Importantly, the JNK V inhibitor has the most potent impact on the least-explored isoform of JNKs, JNK3. As NB is a neural crest-derived malignancy with a high propensity for metastasis, we selected this compound for its high specificity; strong pro-apoptotic effects, evidenced in other cancers; and its neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties, which may help minimise excessive toxicity to neural tissue [76,77,78,79].

An important notion that emerges from our study is that JNK inhibition induced by the chosen inhibitor is not cytotoxic towards primary human Schwann cells (HSC)—a well-established control model for NB in vitro research. Furthermore, JNK inhibition may also modulate the tumour microenvironment (TME) by influencing stromal development, specifically Schwannian stroma, which plays a crucial role in NB to GNB maturation [80,81]. Our results demonstrated that JNK inhibitor treatment reduced the invasion abilities of SH-SY5Y cells, so it is reasonable to hypothesise that JNK inhibition could favour the development of a more organised, Schwannian-rich stroma. JNK inhibitors might induce a more permissive environment for stromal differentiation and maturation by reducing tumour cell invasiveness, which may shift the NB cells towards a phenotype closer to GNB, which is associated with better prognosis [81,82]. Also of particular value in our research is the Seahorse mitochondrial metabolism analysis, which reveals a novel aspect of JNK V’s anti-neoplastic mechanism—significant disruption of both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis—which, together with pro-apoptotic gene regulation, ultimately contributes to its overall antineoplastic efficacy.

A major limitation of our in vitro study is that all experimental data are generated in a single neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y, which is an MYCN-non-amplified NB cell model that represents only low- and intermediate-risk NB. To investigate the effect of JNK inhibition on an appropriate model of high-risk NB patients and to be able to ensure the generalizability of the results, further experiments on MYCN-amplified cell lines are mandatory. Furthermore, future research should include not only additional NB cell lines but also primary tumour-derived cells, supportive stromal cell types, and in vivo studies to better understand tumour cell death mechanisms and more accurately reflect the TME and disease complexity. Secondly, exclusive pharmacological JNK inhibition with only a single ATP-competitive inhibitor was tested. Further genetic validation, including JNK silencing, knockout models, or rescue strategies, is necessary to confirm the mechanistic basis of the observed effects. As an exclusive reliance on a single inhibitor is limited, additional orthogonal approaches would further strengthen causal inference and also exclude off-target effects. Thirdly, another important note is that the NB cell death observed in our cytotoxicity experiments may not be solely attributed to apoptosis, but also to alternative mechanisms such as necrosis or necroptosis, which, though not examined in this study, could also have contributed to the observed effects. Fourthly, and moreover, the short 24 h incubation period in toxicity and mechanistic experiments may capture only the acute, short-term effects and cellular responses of JNK inhibition in NB cells, necessitating extended exposure times to access long-term cellular responses and long-term toxicity. Further experiments with longer incubation times are necessary.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) is a thrice-cloned subline of the SK-N-SH cell line and constitutes a well-established, neuronally relevant NB in vitro model [83,84]. The cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) as well as 1% penicillin–streptomycin (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA). As a relevant control for NB in vitro research, primary Human Schwann Cells (HSC) (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) isolated from the human spinal nerve were used. These neural crest-derived cells ensheathe and myelinate axons of peripheral nerves, and interact with cancerous cells in the tumour microenvironment (TME) [85]. The cells were cultured in Schwann Cell Medium (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA). As an additional control, widely used in toxicology and cellular biology research, the BJ cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA)—human fibroblasts from normal foreskin—was used [86,87]. Cells were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 200 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), and 1% antibiotics solution. Using those two different normal cell lines as controls allows us to evaluate both the relevance and broader safety profile of the tested compound. All cell lines were cultured in the same incubator at standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity). Every 2 to 3 days, the cell culture media were replaced. After the cells reached 70–80% confluence, cell passages were performed, with a brief rinse with Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and detachment using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA solution (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For each experiment, the cell culture was not expanded beyond passage 15.

4.2. Inhibitor Treatment

To selectively inhibit the JNK pathway, we have used the commercially available JNK inhibitor AS601245 (JNK inhibitor V, JNK V)—1,3-Benzothiazol-2-yl-(2-{[2-(3-pyridinyl)ethyl]amino}-4-pyrimidinyl) acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). It is a potent, reversible, and cell-permeable ATP-competitive inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (IC50 values: 150 nM for hJNK1, 220 nM for hJNK2, and 70 nM for hJNK3) with anti-inflammatory characteristics and a 10- to 100-fold better selectivity compared to a panel of 25 other commonly researched kinases [88,89]. The JNK V showed notable antineoplastic properties in multiple T-ALL and colon cancer in vitro studies [27,74,75]. Importantly, it exerts the strongest inhibitory effect on the JNK3 isoform, whose role in tumours is not fully established. The inhibitor’s efficacy and well-established in vivo safety profile have been demonstrated in gerbils, mice, and rats following oral, intraperitoneal, and intravenous administration [88,90]. The compound was reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and maintained at −20 °C in darkness. The vehicle concentration in the culture medium was not more than 0.01%. Furthermore, cultures treated with 0.01% DMSO alone were used to rule out the potential effects of the vehicle.

4.3. Cytotoxicity Measurement

The cytotoxicity assessment of the evaluated JNK V compound was conducted using the 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) colorimetric assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The experiment was performed on SH-SY5Y, HSC, and BJ cell lines. Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well plate and cultured in 100 μL of the complete growth medium for 24 h. The cells were then treated and incubated with a particular compound for a standardised time of 24 h to assess the short-term effects of the investigated compound. SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to a wide concentration range of JNK V (0.1–100 µM). HSC and BJ cells were treated with JNK V at concentrations of 0.1–25 µM, because of their substantial sensitivity to DMSO at the concentration required to dissolve higher doses of the investigated compound, specifically 50 and 100 µM JNK V, together with the reduced solubility and partial precipitation of the compound, specifically in Schwann Cell Medium. Cells treated with 20% DMSO served as a positive control. Cells treated with 0.01% DMSO served as the solvent control, while untreated cells constituted the negative control. After incubation for 24 h, 75 μL of XTT/PMS suspension was added to each well in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. After 2 h of incubation in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C, the absorbance measurement was performed using the Synergy HT spectrophotometer (BioTek, Shoreline, WA, USA) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

4.4. Morphology Assessment

The morphology of SH-SY5Y cells was assessed using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), after 24 h incubation of the cells with, respectively, 0.1–100 µM JNK V in the experimental group, 0.01% DMSO in the solvent control group, or 20% DMSO in the positive control group. For each experimental condition, at least 10 random fields were acquired, capturing around 200 cells per replicate. Images were captured at 10× magnification, under identical exposure settings. All images were saved in TIFF format. Morphological changes, including cell shape, adhesion, neurite outgrowth, cytoplasmic integrity, and nuclear condensation, were analysed qualitatively.

4.5. Colony-Forming Assessment

A clonogenic assay, which assesses the ability of a single cell to form a colony over 14 days, was performed on SH-SY5Y cells to evaluate their proliferation and survival abilities. Cells treated with 0.1–25 μM JNK V constituted the experimental control, while untreated cells served as a negative control [91]. Firstly, cells at a density of 2 × 103 cells/well were seeded on a 12-well plate with EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After being incubated for 72 h, the JNK V inhibitor was applied. The media was refreshed every 3 days, and cells were grown for a total of 2 weeks. Ultimately, the cells were washed with DPBS, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min, and visualised using 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min. The plate was then allowed to dry. The colony-forming abilities of cells were assessed using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). For each experimental condition, at least 10 random fields were acquired, capturing around 50 cells per replicate. Images were captured at 400× magnification, under identical exposure settings. Confluence was quantified based on the percentage of the cell-covered surface area within randomly selected 100 × 100 µm image fragments. The proportion of the area covered by cells was calculated using ImageJ software (version 1.53, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.6. Migration Assessment

The wound healing (scratch) assay was performed to assess the migration abilities of SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with JNK at concentrations of 0.1–3 μM, which maintained cell viability over 80%, confirmed by a previous XTT assay [92]. Cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells/mL in an EMEM with 10% FBS. After reaching full confluence, a 200 μL sterile plastic tip was used to scrape the cell monolayer longitudinally on each well. All wells were then intensively rinsed three times with DPBS to mechanically eliminate non-adherent floating cells. To suppress the contribution of cell proliferation but allow cells to survive for the following 72 h, cells were incubated in a medium supplemented with a low serum concentration (1% FBS) together with an inhibitor at an appropriate concentration. Untreated cells constituted a negative control. Subsequently, the scratched area was carefully viewed, and representative images were captured at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after wounding time points using an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were captured at 100× magnification, under identical exposure settings. All images were saved in TIFF format and analysed using ImageJ software (version 1.53, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The percentage of wound closure was calculated by identifying the low-texture region corresponding to the acellular wound area in the Laplacian texture profile and expressing the reduction in this area relative to the initial wound width, as recommended [93].

4.7. Apoptosis Evaluation

The Caspase-3 colorimetric activity assay (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was performed to assess the effect of JNK inhibition on the apoptosis of SH-SY5Y cells. Cells treated with 0.75–100 µM of JNK V for 24 h constituted the experimental sample, the negative control comprised untreated cells, whereas positive control cells were treated with 10 μM staurosporine for 24 h. Following incubation, the cells were dissociated with Trypsin/EDTA solution and centrifuged. Subsequently, the samples were prepared for further protein isolation by resuspension of the cell pellet in 50 μL of cold lysis buffer, incubation for 10 min on ice, centrifugation at 10,000× g for 1 min, transfer of supernatant to new microcentrifuge tubes, and maintenance on ice. Then, the PierceTM Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), calibrated to 100 μg of protein per sample, was performed to determine the protein concentration. Briefly, each well of the microplate was filled with 50 μL of sample per well (except for background wells), 50 μL of freshly prepared Caspase Reaction Mix using 2X Reaction Buffer with dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 μL of the substrate solution (4 mM Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-para-nitroanilide (DEVD-pNA)), and then incubated for 120 min at 37 °C. By monitoring the samples’ absorbance at 400 nm in the Synergy HT Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA), the quantity of p-NA was measured quantitatively.

4.8. Gene Expression Analysis

The expression of selected genes connected with apoptosis and cellular damage control was evaluated by qRT-PCR analysis in cells treated with JNK V at 1 μM, 10 μM, and 25 μM and 0.01% DMSO as a solvent control. Untreated cells constituted the control. Following incubation with the investigated compound, the PureLinkTM RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to extract the total RNA, in line with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Then, the obtained samples’ RNA levels were measured and normalised by use of the Synergy HT Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Subsequently, using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), a final concentration of 100 ng of cDNA was produced by transcription of the isolated RNA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, the expression profile of the MAPK10 (Hs00959268_m1), BCL2 (Hs00608023_m1), BAX (Hs00180269_m1), and NRF2 (Hs00232352_m1) was analysed using the TaqManTM Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1) served as a reference gene. The overall reaction volume was 20 μL, containing 1 μL probes, 1 μL cDNA, 10 μL TaqManTM Universal PCR Master Mix II (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), and 8 μL nuclease-free water (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Ultimately, the Bio-Rad CFX96 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to conduct the PCR reaction in the following sequence: initial denaturation (15 min, 95 °C); cycling–denaturation (10 s, 95 °C); and annealing/extension (60 s, 60 °C), for 40 cycles each. All collected data was quantified using 2−∆∆Ct values.

4.9. Protein Expression Analysis

The effect of JNK V on the expression of several key apoptosis- and cell cycle-related proteins in SH-SY5Y cells was evaluated by Western blot analysis. The JNK V inhibitor was applied to the cells for 24 h at doses of 1, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µM. The untreated cells constituted the negative control. Following treatment, the cells were collected from the wells, and the MinuteTM Total Protein Extraction Kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN, USA) was used to extract the total protein. The PierceTM BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to assess and normalise the protein quantities in the samples. The protein samples were denatured at 70 °C for 10 min, placed into gel wells, and subsequently electrophoresed for 50 min using the NuPageTM/XCell SureLockTM system (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). After that, the proteins were moved to a PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated for one hour. The membrane was then blocked for one hour in a solution of 5% BSA for phosphoproteins, or skim milk for non-phosphoproteins (BioShop Canada, Burlington, ON, Canada) in 1X TBST (Thermo Scientific Chemicals, Waltham, MA, USA). Then, the membranes were incubated for 24 h with primary monoclonal antibodies for targeted proteins such as JNK, p-JNK, Bim, Bcl-2, p-Bcl-2, p53, and HIF-1α (dilution 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). The antibodies’ ID numbers are listed in Table 1. The loading control was β-actin. The next day, secondary HRP-linked antibodies (dilution 1:5000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were added to the membranes after they had been cleaned three times with 1X TBST. Following a final wash in TBST, the membrane was exposed to SuperSignalTM West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for five minutes in the dark. The ChemiDocTM Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to detect the protein bands using enhanced chemiluminescence. NIS-Elements Advanced Research software version 5.42 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) was used to conduct the densitometry analysis.

Table 1.

The ID numbers of the applied primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

4.10. Cellular Bioenergetics Assessment

The Agilent Seahorse XFp Real-Time ATP rate assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was performed to evaluate the effect of JNK inhibition on SH-SY5Y cells’ cellular respiration. After being seeded in Seahorse XF HS Miniplates (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), the cells were exposed to 1, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μM of JNK V. Untreated cells constituted the control. The day before the experiment, the Seahorse XFp Sensor Cartridge was hydrated overnight in a non-CO2 incubator as directed by the manufacturer. The cartridge was rehydrated using Seahorse XF Calibrant (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and incubated for 45 min on the day of the test. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the culture medium was removed from each well, and the cells were washed with preheated assay medium (pH 7.4) that contained Seahorse XF DMEM, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a non-CO2 incubator for 45 min to attain the desired temperature and pH before measurement. Then, the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (2.5μM) and the mitochondrial complex I/III inhibitors rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM) solutions were inserted into suitable cartridge ports, in line with the manufacturer’s instructions. After the initial three baseline measurements using a Seahorse XF HS Mini Analyser (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), three measurements were taken after each injection of chemical compounds.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica (version 13; StatSoft, Kraków, Poland). The normality of data distribution was determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test. If data were homogeneous and normally distributed, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni or Tukey’s post hoc testing was performed for comparison between multiple groups. Otherwise, the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks with Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was performed. All studies were performed in triplicate, and the data are presented as mean ± SD. The following symbols indicate statistically significant differences in the graphs: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study to characterise the acute in vitro effects of JNK inhibitor AS601245 (JNK V) on the human MYCN-non-amplified neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. We demonstrate that JNK V reduces SH-SY5Y cell viability and dysregulates key cellular functions, without exerting cytotoxicity toward normal human Schwann cells and fibroblasts under the conditions tested. JNK V induces a dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation, colony formation, and migration, accompanied by increased caspase-3 activity, pro-apoptotic gene and protein expression, and significant disruption of both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. These results provide a detailed description of early cellular responses to pharmacological JNK inhibition in the MYCN-non-amplified neuroblastoma in vitro model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.G., W.R.-K. and I.M.; methodology, W.R.-K., I.M., Z.G., N.S. and K.S.; software, G.G. and I.M.; validation, W.R.-K. and I.M.; formal analysis, W.R.-K. and I.M.; investigation, Z.G., N.S., K.S., G.G. and M.G.; resources, W.R.-K. and I.M.; data curation, Z.G., N.S. and K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.G.; writing—review and editing, K.S., G.G., W.R.-K. and I.M.; visualisation, Z.G. and K.S.; supervision, W.R.-K. and I.M.; project administration, W.R.-K. and I.M.; funding acquisition, W.R.-K. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University of Lodz, Poland [503/1-156-07/503-11-001] and by a grant funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, no. 2015/19/N/NZ3/00055. The APC was funded by the Medical University of Lodz, Poland.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BAX | BCL2-Associated X Apoptosis Regulator |

| BCL2 | B-Cell Lymphoma 2 |

| Cyt-C | Cytochrome C |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| ECAR | Extracellular Acidification Rate |

| EMEM | Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium |

| FBS | Foetal Bovine Serum |

| GNB | Ganglioneuroblastoma |

| HSC | Human Schwann Cells |

| JNK | C-Jun N-Terminal Kinases |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MAPK10/JNK3 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 10/C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase 3 |

| NB | Neuroblastoma |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 |

| OCR | Oxygen Consumption Rate |

| TME | Tumour Microenvironment |

| T-ALL | T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A.C.S. Cancer Statistics. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, M.; Bachetti, T.; Corrias, M.V.; Brignole, C.; Pastorino, F.; Calarco, E.; Bensa, V.; Giusto, E.; Ceccherini, I.; Perri, P. Recent Advances in the Developmental Origin of Neuroblastoma: An Overview. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2022, 41, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hill, C.; Chen, K.; Cheng, C.; Liu, X.; Duan, P.; Gu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ewing, R.M.; et al. Identification of MYCN Non-Amplified Neuroblastoma Subgroups Points towards Molecular Signatures for Precision Prognosis and Therapy Stratification. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 1841–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, B.; Park, K.; Shim, J.; Yoo, K.H.; Koo, H.H.; Sung, K.W.; Park, W.-Y. Genomic Profile of MYCN Non-Amplified Neuroblastoma and Potential for Immunotherapeutic Strategies in Neuroblastoma. BMC Med. Genom. 2020, 13, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Glowacka, A.; Mahmoud, L.; Bazzar, W.; Larsson, L.-G.; Alzrigat, M. MYCN Amplification Is Associated with Reduced Expression of Genes Encoding γ-Secretase Complex and NOTCH Signaling Components in Neuroblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, R.; Thiele, C.J. Immunotherapy Approaches Targeting Neuroblastoma. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2021, 33, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Biyik-Sit, R.; Uzun, Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Thadi, A.; Sussman, J.H.; Pang, M.; Wu, C.-Y.; Grossmann, L.D.; Gao, P.; et al. Longitudinal Single-Cell Multiomic Atlas of High-Risk Neuroblastoma Reveals Chemotherapy-Induced Tumor Microenvironment Rewiring. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-T.; Li, C.; Shen, Y.; You, W.-H.; Han, M.-X.; Mu, Y.-F.; Han, F.-J. Mechanisms of the JNK/P38 MAPK Signaling Pathway in Drug Resistance in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1533352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latham, S.L.; O’Donnell, Y.E.I.; Croucher, D.R. Non-Kinase Targeting of Oncogenic c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Signaling: The Future of Clinically Viable Cancer Treatments. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.-B.; Sheng, J.-P.; Xu, B. Signaling Pathways Involved in Colorectal Cancer: Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulpinas, A.; Tenkutytė, M.; Imbrasaitė, A.; Kalvelytė, A.V. The Role and Efficacy of JNK Inhibition in Inducing Lung Cancer Cell Death Depend on the Concentration of Cisplatin. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 28311–28322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, C.; Yin, M.; Teng, X.; Yang, M.; Kong, D.; Zhang, J.; Peng, W.; Chu, Z.; et al. Inhibition of JNK Signaling Overcomes Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Mediated Immunosuppression and Enhances the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Bladder Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 4199–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itah, Z.; Chaudhry, S.; Raju Ponny, S.; Aydemir, O.; Lee, A.; Cavanagh-Kyros, J.; Tournier, C.; Muller, W.J.; Davis, R.J. HER2-Driven Breast Cancer Suppression by the JNK Signaling Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, 2218373120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, S.Y.; Law, H.K.-W. JNK in Tumor Microenvironment: Present Findings and Challenges in Clinical Translation. Cancers 2021, 13, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pua, L.J.W.; Mai, C.-W.; Chung, F.F.-L.; Khoo, A.S.-B.; Leong, C.-O.; Lim, W.-M.; Hii, L.-W. Functional Roles of JNK and P38 MAPK Signaling in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeke, A.; Misheva, M.; Reményi, A.; Bogoyevitch, M.A. JNK Signaling: Regulation and Functions Based on Complex Protein-Protein Partnerships. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 793–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkouveris, I.; Nikitakis, N.G. Role of JNK Signaling in Oral Cancer: A Mini Review. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 2017, 39, 1010428317711659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; He, L.; Lv, D.; Yang, J.; Yuan, Z. The Role of the Dysregulated JNK Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Human Diseases and Its Potential Therapeutic Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.K.; Ramanathan, M. Piceatannol Selectively Inhibited the JNK3 Enzyme and Augmented Apoptosis through Inhibition of Bcl-2/Cyt-c/Caspase-Dependent Pathways in the Oxygen-Glucose Deprived SHSY-5Y Cell Lines: In Silico and in Vitro Study. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2024, 103, 14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waetzig, V.; Wacker, U.; Haeusgen, W.; Björkblom, B.; Courtney, M.J.; Coffey, E.T.; Herdegen, T. Concurrent Protective and Destructive Signaling of JNK2 in Neuroblastoma Cells. Cell Signal 2009, 21, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; López, J.M. Understanding MAPK Signaling Pathways in Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Esparza, U.; Agustín-Chávez, M.C.; Ochoa-Reyes, E.; Alvarado-González, S.M.; López-Martínez, L.X.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Prado-Barragán, L.A.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J. Recent Advances in the Extraction and Characterization of Bioactive Compounds from Corn By-Products. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, F.; Sunayama, J.; Mori, Y.; Hattori, S.; Shimizu, S.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Yoshioka, K.; Masuyama, N.; Gotoh, Y. JNK Promotes Bax Translocation to Mitochondria through Phosphorylation of 14-3-3 Proteins. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1889–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Qian, C.; Zhao, Y. AS602801 Treatment Suppresses Breast Cancer Metastasis to the Brain by Interfering with Gap-Junction Communication by Regulating Cx43 Expression. Drug Dev. Res. 2024, 85, 22124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanaka, C.; Sato, A.; Okada, M. JNK Signaling in the Control of the Tumor-Initiating Capacity Associated with Cancer Stem Cells. Genes. Cancer 2013, 4, 388–396. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tournier, C. The 2 Faces of JNK Signaling in Cancer. Genes. Cancer 2013, 4, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wu, W.; Jacevic, V.; Franca, T.C.C.; Wang, X.; Kuca, K. Selective Inhibitors for JNK Signalling: A Potential Targeted Therapy in Cancer. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, C.; Zhao, P.; Zhong, R.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Lan, S.; Wu, C.; Qiang, X.; et al. Multiple Kinase Small Molecule Inhibitor Tinengotinib (TT-00420) Alone or With Chemotherapy Inhibit the Growth of SCLC. Cancer Sci. 2025, 116, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Fan, Y.-H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Dou, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Rojas, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of UBE2N Induces Neuroblastoma Cell Death via Activation of P53 and JNK Pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, 1079. [Google Scholar]

- AlKhazal, A.; Chohan, S.; Ross, D.J.; Kim, J.; Brown, E.G. Emerging Clinical and Research Approaches in Targeted Therapies for High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1553511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, Z.; Esmaeili, S.; Xiao, Z.; Kuriakose, D. JNK3 Inhibitors as Promising Pharmaceuticals with Neuroprotective Properties. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2024, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Khan, M.S.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, R.; Rehman, I.U.R.; Ikram, M.; Kim, M.O. Inhibition of JNK Alleviates Chronic Hypoperfusion-Related Ischemia Induces Oxidative Stress and Brain Degeneration via Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-ΚB Signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5291852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Z.; Escutia, C.; Madonna, M.B.; Gupta, K.H. Biological Insight and Recent Advancement in the Treatment of Neuroblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Boterberg, T.; Lucas, J.; Panoff, J.; Valteau-Couanet, D.; Hero, B.; Bagatell, R.; Hill-Kayser, C.E.N. Neuroblastoma. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, 28473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, P.P.T.E. Neuroblastoma Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; National Cancer Institute (USA): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Berbegall, A.P.; Bogen, D.; Pötschger, U.; Beiske, K.; Bown, N.; Combaret, V.; Defferrari, R.; Jeison, M.; Mazzocco, K.; Varesio, L.; et al. Heterogeneous MYCN Amplification in Neuroblastoma: A SIOP Europe Neuroblastoma Study. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Trunk, K.; Fleischhauer, D.; Büchel, G. MYCN in Neuroblastoma: The Kings’ New Clothes and Drugs. EJC Paediatr. Oncol. 2024, 4, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purhonen, J.; Klefström, J.; Kallijärvi, J. MYC—An Emerging Player in Mitochondrial Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1257651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Lv, F.; Xu, G.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Z. Phosphoproteomics Reveals ALK Promote Cell Progress via RAS/JNK Pathway in Neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 75968–75980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Meng, P.; Wang, Y. Breast Cancer Prognosis Prediction and Immune Pathway Molecular Analysis Based on Mitochondria-Related Genes. Genet. Res. 2022, 2022, 2249909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Shibuya, K.; Sato, A.; Seino, S.; Suzuki, S.; Seino, M.; Kitanaka, C. Targeting the K-Ras–JNK Axis Eliminates Cancer Stem-like Cells and Prevents Pancreatic Tumor Formation. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5100–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Okada, M.; Shibuya, K.; Seino, M.; Sato, A.; Takeda, H.; Seino, S.; Yoshioka, T.; Kitanaka, C. JNK Suppression of Chemotherapeutic Agents-Induced ROS Confers Chemoresistance on Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enomoto, A.; Fukasawa, T.; Yoshizaki, A. Hyperthermia-Mediated Cell Death via Deregulation of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase and c-Jun NH2-Terminal Kinase Signaling. Front. Cell Death 2024, 3, 1465506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Hu, J. The Role of JNK in Prostate Cancer Progression and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delprat, V.; Tellier, C.; Demazy, C.; Raes, M.; Feron, O.; Michiels, C. Cycling Hypoxia Promotes a Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype in Macrophages via JNK/P65 Signaling Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasi, S.; Kennedy, B.E.; El-Aghil, M.; Sterea, A.M.; Gujar, S.; Partida-Sánchez, S.; El Hiani, Y. TRPM2 Channel-Mediated Regulation of Autophagy Maintains Mitochondrial Function and Promotes Gastric Cancer Cell Survival via the JNK-Signaling Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3637–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.F.; Latham, S.L.; Kamili, A.; Wheatley, M.S.; Han, J.Z.R.; Wong-Erasmus, M.; Phimmachanh, M.; Nobis, M.; Pantarelli, C.; Cadell, A.L.; et al. Memory of Stochastic Single-Cell Apoptotic Signaling Promotes Chemoresistance in Neuroblastoma. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, 8314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersal, K.I.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.S.; Ali, E.M.H.; Ammar, U.M.; Zaraei, S.-O.; Haque, M.M.; Das, T.; Hassan, N.F.; Kim, E.E.; Lee, J.-S.; et al. Evaluation of Novel Pyrazol-4-Yl Pyridine Derivatives Possessing Arylsulfonamide Tethers as c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Inhibitors in Leukemia Cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 261, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Fu, X.; Xiang, P.; Fan, T. AS602801 Sensitizes Glioma Cells to Temozolomide and Vincristine by Blocking Gap Junction Communication between Glioma Cells and Astrocytes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 4062–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Suzuki, S.; Sanomachi, T.; Togashi, K.; Seino, S.; Kitanaka, C.; Okada, M. AS602801, an Anti-Cancer Stem Cell Drug Candidate, Suppresses Gap-Junction Communication Between Lung Cancer Stem Cells and Astrocytes. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 5093–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Qi, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Luo, M.; Chen, J. Recent Advances in C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Yang, X.; Shuai, W.; Wang, G.; Ouyang, L. Update on JNK Inhibitor Patents: 2015 to Present. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2024, 34, 907–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsriku, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Ye, Y.; Kumar, G.; Surapaneni, S. Metabolism and Disposition of a Potent and Selective JNK Inhibitor [14C]Tanzisertib Following Oral Administration to Rats, Dogs and Humans. Xenobiotica Fate Foreign Compd. Biol. Syst. 2015, 45, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velden, J.L.J.; Ye, Y.; Nolin, J.D.; Hoffman, S.M.; Chapman, D.G.; Lahue, K.G.; Abdalla, S.; Chen, P.; Liu, Y.; Bennett, B.; et al. JNK Inhibition Reduces Lung Remodeling and Pulmonary Fibrotic Systemic Markers. Clin. Transl. Med. 2016, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popmihajlov, Z.; Sutherland, D.J.; Horan, G.S.; Ghosh, A.; Lynch, D.A.; Noble, P.W.; Richeldi, L.; Reiss, T.F.; Greenberg, S. CC-90001, a c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Inhibitor, in Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis: Design of a Phase 2, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2022, 9, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calil, V.; Sudo, F.K.; Santiago-Bravo, G.; Lima, M.A.; Mattos, P. Anosognosia in Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Systematic Review. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2021, 79, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Qi, Y.; Wu, J.; Lin, F.; Liu, Z.; Cui, X. Follistatin Is a Crucial Chemoattractant for Mouse Decidualized Endometrial Stromal Cell Migration by JNK Signalling. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Kuramoto, K.; Takeda, H.; Watarai, H.; Sakaki, H.; Seino, S.; Seino, M.; Suzuki, S.; Kitanaka, C. The Novel JNK Inhibitor AS602801 Inhibits Cancer Stem Cells in Vitro and in Vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27021–27032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Lin, M.; Li, L.; Yang, B.; He, Q. The Proteasome Inhibitor Bortezomib Enhances ATRA-Induced Differentiation of Neuroblastoma Cells via the JNK Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Furfaro, A.L.; Piras, S.; Passalacqua, M.; Domenicotti, C.; Parodi, A.; Fenoglio, D.; Pronzato, M.A.; Marinari, U.M.; Moretta, L.; Traverso, N.; et al. HO-1 up-Regulation: A Key Point in High-Risk Neuroblastoma Resistance to Bortezomib. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczkowska, K.; Sokolowska, K.E.; Taryma-Lesniak, O.; Pastuszak, K.; Supernat, A.; Bybjerg-Grauholm, J.; Hansen, L.L.; Paczkowska, E.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Machaliński, B. Bortezomib Induces Methylation Changes in Neuroblastoma Cells That Appear to Play a Significant Role in Resistance Development to This Compound. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfeldt, S.C.H.; Laufer, S.; Goettert, M.I. A Highly Selective In Vitro JNK3 Inhibitor, FMU200, Restores Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Reduces Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, F.; El-Gokha, A.; Ansideri, F.; Eitel, M.; Döring, E.; Sievers-Engler, A.; Lange, A.; Boeckler, F.M.; Lämmerhofer, M.; Koch, P.; et al. Tri- and Tetrasubstituted Pyridinylimidazoles as Covalent Inhibitors of c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase 3. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü, E.; Ayan, İ.Ç.; Çetinkaya, S.; Dursun, H.G.; Vural, H. Piceatannol Induces Caspase-Dependent Apoptosis by Modulating Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species/Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Enhances Autophagy in Neuroblastoma Cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. JAT 2024, 44, 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerszon, J.; Walczak, A.; Rodacka, A. Attenuation of H2O2-Induced Neuronal Cell Damage by Piceatannol. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 35, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, M.; Kin, K.; Tajiri, T. Abstract B091: Disruption of Cancer Stemness by Targeting the JNK-STAT3 Pathway in Neuroblastoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.Q.; Du, F.X.; Zhang, L.H.; Gu, F.Y.; Deng, Y.L.; Ji, Y.Z. Prevention of STAT3-Related Pathway in SK-N-SH Cells by Natural Product Astaxanthin. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Lv, M.; Zhu, N.; Li, Y.; Feng, J.; Shen, B.; Zhang, J. Basal C-Jun NH2-Terminal Protein Kinase Activity Is Essential for Survival and Proliferation of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 3214–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, L.; Ji, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Li, L.; Zhuo, Z.; Zheng, Z. RHOGTPase-Related Gene Signature Predicts Prognosis, Immunotherapy Response, and Chemotherapy Sensitivity in Colon Cancer. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 4702–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerbone, A.; Toaldo, C.; Minelli, R.; Ciamporcero, E.; Pizzimenti, S.; Pettazzoni, P.; Roma, G.; Dianzani, M.U.; Ullio, C.; Ferretti, C.; et al. Rosiglitazone and AS601245 Decrease Cell Adhesion and Migration through Modulation of Specific Gene Expression in Human Colon Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerbone, A.; Toaldo, C.; Pizzimenti, S.; Pettazzoni, P.; Dianzani, C.; Minelli, R.; Ciamporcero, E.; Roma, G.; Dianzani, M.U.; Canaparo, R.; et al. AS601245, an Anti-Inflammatory JNK Inhibitor, and Clofibrate Have a Synergistic Effect in Inducing Cell Responses and in Affecting the Gene Expression Profile in CaCo-2 Colon Cancer Cells. PPAR Res. 2012, 2012, 269751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, P.P. JNK Inhibitors as Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Agents. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Reyes Corrales, T.; Losada-Pérez, M.; Casas-Tintó, S. JNK Pathway in CNS Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Dai, Q.; Han, K.; Hong, W.; Jia, D.; Mo, Y.; Lv, Y.; Tang, H.; Fu, H.; Geng, W. JNK-IN-8, a c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Inhibitor, Improves Functional Recovery through Suppressing Neuroinflammation in Ischemic Stroke. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Upadhayay, S.; Mehan, S. Understanding Abnormal C-JNK/P38MAPK Signaling Overactivation Involved in the Progression of Multiple Sclerosis: Possible Therapeutic Targets and Impact on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1630–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnat, H.B.; Chan, E.S.; Ng, D.; Yu, W. Maturation of Metastases in Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors (Neuroblastoma) of Children. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2023, 82, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Torres, R.D.; Olloquequi, J.; Parcerisas, A.; Ureña, J.; Ettcheto, M.; Beas-Zarate, C.; Camins, A.; Verdaguer, E.; Auladell, C. JNK Signaling and Its Impact on Neural Cell Maturation and Differentiation. Life Sci. 2024, 350, 122750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, T.; Sammons, R.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Dalby, K.N.; Ueno, N.T. JNK Signaling in Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos Cogo, S.; Nascimento, T.; Almeida Brehm Pinhatti, F.; França Junior, N.; Santos Rodrigues, B.; Cavalli, L.R.; Elifio-Esposito, S. An Overview of Neuroblastoma Cell Lineage Phenotypes and in Vitro Models. Exp. Biol. Med. Maywood NJ 2020, 245, 1637–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalevich, J.; Santerre, M.; Langford, D. Considerations for the Use of SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells in Neurobiology. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2013, 2311, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deborde, S.; Wong, R.J. The Role of Schwann Cells in Cancer. Adv. Biol. 2022, 6, 2200089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadalutti, C.A.; Wilson, S.H. Using Human Primary Foreskin Fibroblasts to Study Cellular Damage and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2020, 86, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannerström, M.; Toimela, T.; Sarkanen, J.-R.; Heinonen, T. Human BJ Fibroblasts Is an Alternative to Mouse BALB/c 3T3 Cells in In Vitro Neutral Red Uptake Assay. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 121 (Suppl. S3), 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, S.; Hiver, A.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Gaillard, P.; Gotteland, J.-P.; Vitte, P.-A. AS601245 (1,3-Benzothiazol-2-Yl (2-[2-(3-Pyridinyl) Ethyl] Amino-4 Pyrimidinyl) Acetonitrile): A c-Jun NH2-Terminal Protein Kinase Inhibitor with Neuroprotective Properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 310, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch, M.A.; Arthur, P.G. Inhibitors of C-Jun N-Terminal Kinases: JuNK No More? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1784, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carboni, S.; Boschert, U.; Gaillard, P.; Gotteland, J.-P.; Gillon, J.-Y.; Vitte, P.-A. AS601245, a c-Jun NH2-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Inhibitor, Reduces Axon/Dendrite Damage and Cognitive Deficits after Global Cerebral Ischaemia in Gerbils. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brix, N.; Samaga, D.; Belka, C.; Zitzelsberger, H.; Lauber, K. Analysis of Clonogenic Growth in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 4963–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radstake, W.E.; Gautam, K.; Rompay, C.; Vermeesen, R.; Tabury, K.; Verslegers, M.; Baatout, S.; Baselet, B. Comparison of in Vitro Scratch Wound Assay Experimental Procedures. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 33, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazzini, V.; Vasarri, M.; Degl’Innocenti, D.; Guastini, A.; Barletta, E.; Salvatici, M.C.; Bergonzi, M.C. Comparison of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Soluplus Micelles to Optimize the Bioactivity of Posidonia Oceanica Extract on Human Neuroblastoma Cell Migration. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Mendioroz, I.; Garate-Soraluze, E.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E. A simple method to assess clonogenic survival of irradiated cancer cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2023, 174, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinotti, S.; Ranzato, E. Scratch wound healing assay. In Epidermal Cells: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, A.A.; Schneider, B., Jr.; Schneider, F.K.; Carvalho, B.H.K.D. Measurement of wound area for early analysis of the scar predictive factor. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).