A Rare Case of Mild Hemophilia A in a Female with Mosaic Monosomy X and a De Novo F8 Variant

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Coagulation Study

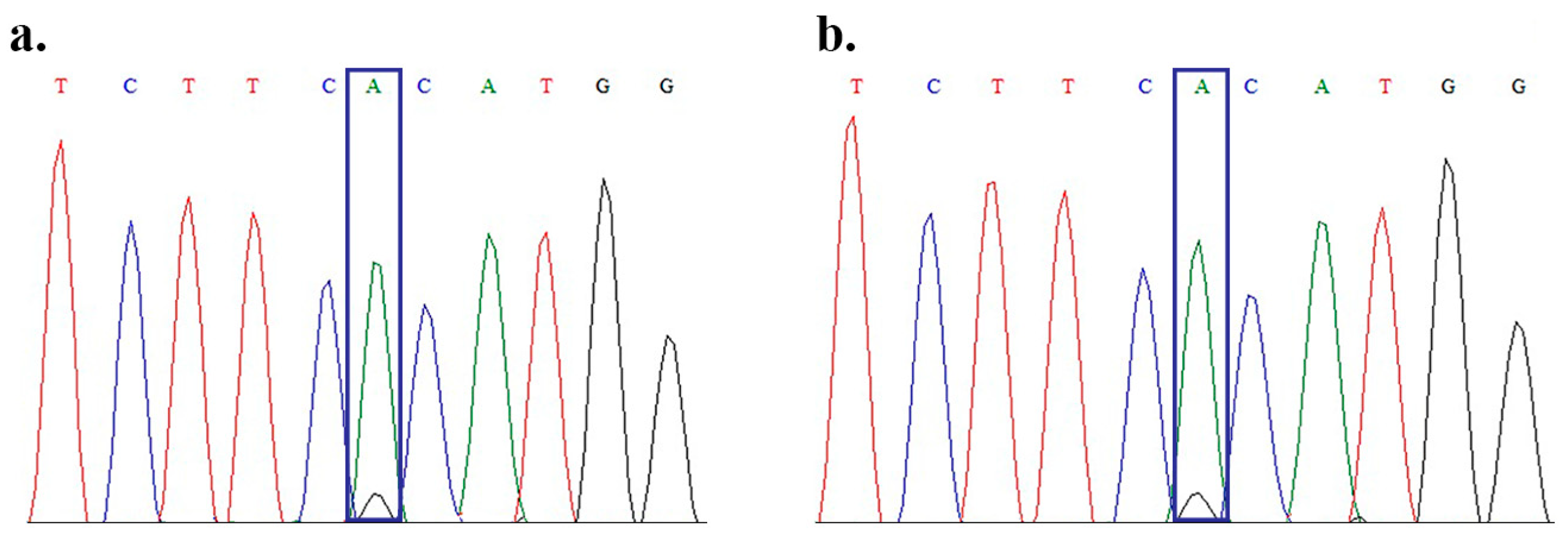

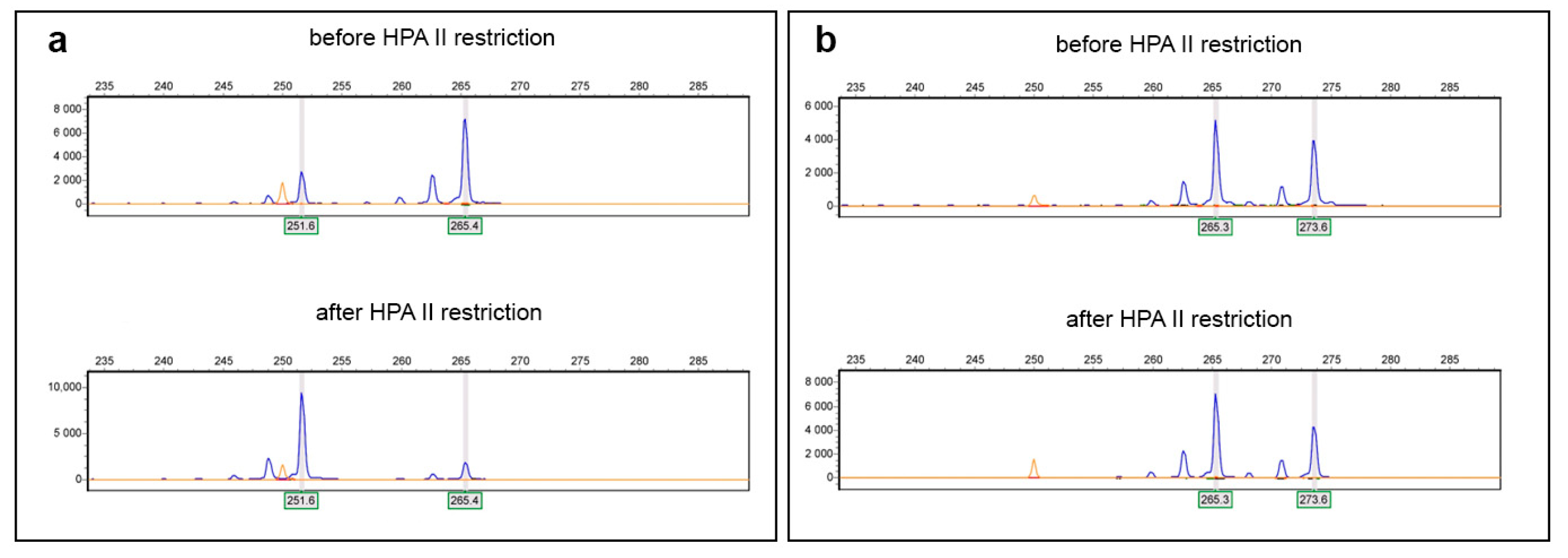

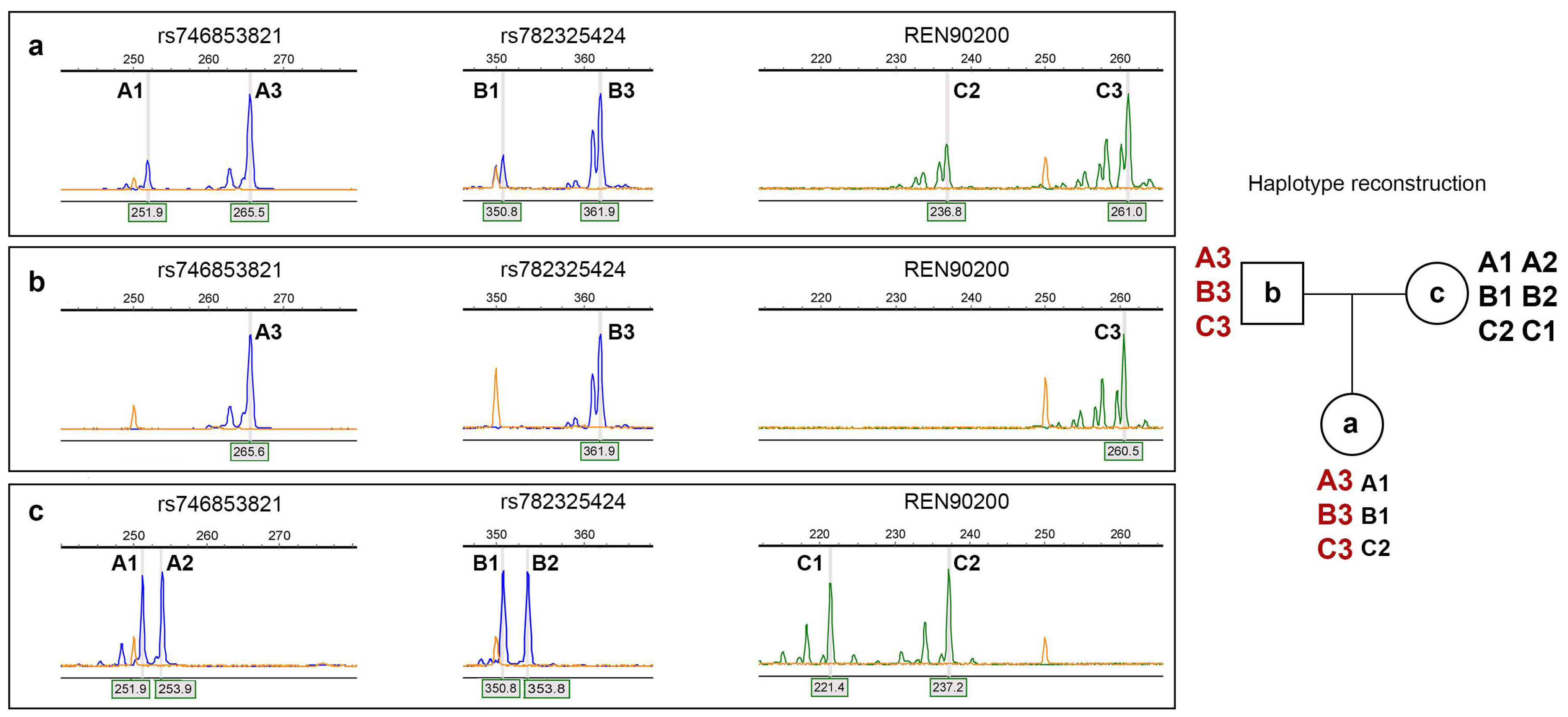

4.2. DNA Extraction and Detection of Mutations

4.3. Conventional Cytogenetic Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HA | Hemophilia A |

| XCI | X chromosome inactivation |

| STR | Short tandem repeat |

| TS | Turner syndrome |

| APTT | Activated partial thromboplastin time |

| vWF | Von Willebrand factor |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| LD-PCR | Long-range polymerase chain reaction |

| MLPA | Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification |

References

- Gitschier, J.; Wood, W.I.; Goralka, T.M.; Wion, K.L.; Chen, E.Y.; Eaton, D.H.; Vehar, G.A.; Capon, D.J.; Lawn, R.M. Characterization of the Human Factor VIII Gene. Nature 1984, 312, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winikoff, R.; Scully, M.F.; Robinson, K.S. Women and Inherited Bleeding Disorders—A Review with a Focus on Key Challenges for 2019. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2019, 58, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D. Hemophilia and Other Congenital Coagulopathies in Women. J. Hematol. 2024, 13, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkle, B.A.; Johnsen, J.M.; Wheeler, M.; Watson, C.; Skinner, M.; Pierce, G.F.; on behalf of My Life Our Future Programme. Genotypes, Phenotypes and Whole Genome Sequence: Approaches from the My Life Our Future Haemophilia Project. Haemophilia 2018, 24, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cygan, P.H.; Kouides, P.A. Regulation and Importance of Factor VIII Levels in Hemophilia A Carriers. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2021, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A.; Sidonio, R.; Jain, N.; Tsao, E.; Tymoszczuk, J.; Oviedo Ovando, M.; Kulkarni, R. Women and Girls with Haemophilia and Bleeding Tendencies: Outcomes Related to Menstruation, Pregnancy, Surgery and Other Bleeding Episodes from a Retrospective Chart Review. Haemophilia 2021, 27, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.H.; Bean, C.J. Genetic Causes of Haemophilia in Women and Girls. Haemophilia 2021, 27, e164–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczar, S.; Babol-Pokora, K.; Jatczak-Pawlik, I.; Taha, J.; Klukowska, A.; Laguna, P.; Windyga, J.; Odnoczko, E.; Zdziarska, J.; Iwaniec, T.; et al. Six Molecular Patterns Leading to Hemophilia A Phenotype in 18 Females from Poland. Thromb. Res. 2020, 193, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, A.; Brondke, H.; Müsebeck, J.; Pollmann, H.; Srivastava, A.; Oldenburg, J. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Hemophilia A Phenotype in Seven Females. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renault, N.K.; Dyack, S.; Dobson, M.J.; Costa, T.; Lam, W.L.; Greer, W.L. Heritable Skewed X-Chromosome Inactivation Leads to Haemophilia A Expression in Heterozygous Females. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, C.P.; Rossetti, L.C.; Abelleyro, M.M.; Tetzlaff, T.; Candela, M.; Neme, D.; Sciuccati, G.; Bonduel, M.; Medina-Acosta, E.; Larripa, I.B.; et al. Phenotype–Genotype Correlations in Hemophilia A Carriers Are Consistent with the Binary Role of the Phase between F8 and X-chromosome Inactivation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 13, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardik, R.; Avishai, E.; Lalezari, S.; Barg, A.A.; Levy-Mendelovich, S.; Budnik, I.; Barel, O.; Khavkin, Y.; Kenet, G.; Livnat, T. Molecular Mechanisms of Skewed X-Chromosome Inactivation in Female Hemophilia Patients—Lessons from Wide Genome Analyses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos-Landgraf, J.M.; Cottle, A.; Plenge, R.M.; Friez, M.; Schwartz, C.E.; Longshore, J.; Willard, H.F. X Chromosome–Inactivation Patterns of 1005 Phenotypically Unaffected Females. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garagiola, I.; Mortarino, M.; Siboni, S.M.; Boscarino, M.; Mancuso, M.E.; Biganzoli, M.; Santagostino, E.; Peyvandi, F. X Chromosome Inactivation: A Modifier of Factor VIII and IX Plasma Levels and Bleeding Phenotype in Haemophilia Carriers. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 29, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Michele, D.M.; Gibb, C.; Lefkowitz, J.M.; Ni, Q.; Gerber, L.M.; Ganguly, A. Severe and Moderate Haemophilia A and B in US Females. Haemophilia 2014, 20, e136–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.-K.; Ren, H.-Y.; Ren, J.-H.; Guo, X.-N. Compound Heterozygous Hemophilia A in a Female Patient and the Identification of a Novel Missense Mutation, p.Met1093Ile. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 9, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surin, V.L.; Salomashkina, V.V.; Pshenichnikova, O.S.; Perina, F.G.; Bobrova, O.N.; Ershov, V.I.; Budanova, D.A.; Gadaev, I.Y.; Konyashina, N.I.; Zozulya, N.I. New Missense Mutation His2026Arg in the Factor VIII Gene Was Revealed in Two Female Patients with Clinical Manifestation of Hemophilia A. Russ. J. Genet. 2018, 54, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venceslá, A.; Fuentes-Prior, P.; Baena, M.; Quintana, M.; Baiget, M.; Tizzano, E.F. Severe Haemophilia A in a Female Resulting from an Inherited Gross Deletion and a de Novo Codon Deletion in the F8 Gene. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, A.; Qiao, C.; Shao, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Poon, M.-C.; et al. Investigation of a Hemophilia Family with One Female Hemophilia A Patient and 12 Male Hemophilia A Patients. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 104, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreth, R.M.; El-Maarri, O.; Schröder, J.; Budde, U.; Herrmann, F.H.; Oldenburg, J. Haemophilia A in a Female Caused by Coincidence of a Swyer Syndrome and a Missense Mutation in Factor VIII Gene. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 95, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blag, C.; Serban, M.; Ursu, C.E.; Popa, C.; Traila, A.; Jinca, C.; Tomuleasa, C.; Bota, M.; Ionita, I.; Arghirescu, T.S. Rare within Rare: A Girl with Severe Haemophilia A and Turner Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendt, A.; Wójtowicz-Marzec, M.; Wysokińska, B.; Kwaśniewska, A. Severe Haemophilia a in a Preterm Girl with Turner Syndrome—A Case Report from the Prenatal Period to Early Infancy (Part I). Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, S.; Aumann, V.; Nanda, I.; Oldenburg, J.; Müller, C.R. Mild Haemophilia A in a Female Patient with a Large X-chromosomal Deletion and a Missense Mutation in the F8 Gene—A Case Report. Haemophilia 2013, 19, e310–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.L.; McNamara, E.A.; Longoni, M.; Miller, D.E.; Rohanizadegan, M.; Newman, L.A.; Hayes, F.; Levitsky, L.L.; Herrington, B.L.; Lin, A.E. Dual Diagnoses in 152 Patients with Turner Syndrome: Knowledge of the Second Condition May Lead to Modification of Treatment and/or Surveillance. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2018, 176, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Allegaert, K.; Mei, D.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, S.; Fang, Y.; et al. Evaluating the Relationship between the Proportion of X-Chromosome Deletions and Clinical Manifestations in Children with Turner Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1324160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuke, M.A.; Ruth, K.S.; Wood, A.R.; Beaumont, R.N.; Tyrrell, J.; Jones, S.E.; Yaghootkar, H.; Turner, C.L.S.; Donohoe, M.E.; Brooke, A.M.; et al. Mosaic Turner Syndrome Shows Reduced Penetrance in an Adult Population Study. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, G.S.; Hammond, D.; Melnyk, J. Hemophilia A in a Phenotypically Normal Female with XX/XO Mosaicism. N. Engl. J. Med. 1965, 273, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, M.; Bazrafshan, A.; Moghadam, M.; Karimi, M. Severe Hemophilia in a Girl Infant with Mosaic Turner Syndrome and Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2016, 27, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophilus, B.D.M.; Enayat, M.S.; Higuchi, M.; Kazazian, H.H.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Hill, F.G.H. Independent Occurrence of the Novel Arg2163 to His Mutation in the Factor VIII Gene in Three Unrelated Families with Haemophilia A with Different Phenotypes. Hum. Mutat. 1998, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, N.; Markoff, A.; Eisert, R.; Wermes, C.; Pollmann, H.; Todorova, A.; Chlystun, M.; Nowak-Göttl, U.; Horst, J. Spectrum of Molecular Defects and Mutation Detection Rate in Patients with Mild and Moderate Hemophilia A. Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.A.; Aung, H.T.; Nandini, A.; Woods, R.G.; Fairbairn, D.J.; Rowell, J.A.; Young, D.; Susman, R.D.; Brown, S.A.; Hyland, V.J.; et al. Demonstration of a Novel Xp22.2 Microdeletion as the Cause of Familial Extreme Skewing of X-inactivation Utilizing Case-parent Trio SNP Microarray Analysis. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2018, 6, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pshenichnikova, O.; Salomashkina, V.; Poznyakova, J.; Selivanova, D.; Chernetskaya, D.; Yakovleva, E.; Dimitrieva, O.; Likhacheva, E.; Perina, F.; Zozulya, N.; et al. Spectrum of Causative Mutations in Patients with Hemophilia A in Russia. Genes 2023, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannoy, N.; Hermans, C. Genetic Mosaicism in Haemophilia: A Practical Review to Help Evaluate the Risk of Transmitting the Disease. Haemophilia 2020, 26, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.H.; Gitlin, S.A.; Patrick, J.L.; Crain, J.L.; Wilson, J.M.; Griffin, D.K. The Origin, Mechanisms, Incidence and Clinical Consequences of Chromosomal Mosaicism in Humans. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiela, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Karlins, E.; Sampson, J.N.; Freedman, N.D.; Yang, Q.; Hicks, B.; Dagnall, C.; Hautman, C.; Jacobs, K.B.; et al. Female Chromosome X Mosaicism Is Age-Related and Preferentially Affects the Inactivated X Chromosome. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invernizzi, P.; Miozzo, M.; Selmi, C.; Persani, L.; Battezzati, P.M.; Zuin, M.; Lucchi, S.; Meroni, P.L.; Marasini, B.; Zeni, S.; et al. X Chromosome Monosomy: A Common Mechanism for Autoimmune Diseases. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersak, K.; Veble, A. Low-Level X Chromosome Mosaicism in Women with Sporadic Premature Ovarian Failure. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 22, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniatis, T.; Fritsch, E.F.; Sambrook, J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; 14 print; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Long Island, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-87969-136-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnall, R.D.; Giannelli, F.; Green, P.M. Int22h-related Inversions Causing Hemophilia A: A Novel Insight into Their Origin and a New More Discriminant PCR Test for Their Detection. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 4, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnall, R.D.; Waseem, N.; Green, P.M.; Giannelli, F. Recurrent Inversion Breaking Intron 1 of the Factor VIII Gene Is a Frequent Cause of Severe Hemophilia A. Blood 2002, 99, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomashkina, V.V.; Pshenichnikova, O.S.; Perina, F.G.; Surin, V.L. A Founder Effect in Hemophilia A Patients from Russian Ural Region with a New p.(His634Arg) Variant in F8 Gene. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2022, 33, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.C.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Moseley, A.B.; Rosenblatt, H.M.; Belmont, J.W. Methylation of Hpall and Hhal Sites Near the Polymorphic CAG Repeat in the Human Androgen-Receptor Gene Correlates with X Chromosome Inactivation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992, 51, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature. ISCN 2020: An International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (2020): Recommendations of the International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature Including Revised Sequence-Based Cytogenomic Nomenclature Developed in Collaboration with the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) Sequence Variant Description Working Group; McGowan-Jordan, J., Hastings, R.J., Moore, S., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-318-06706-4. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter (Normal Range) | Patient, Age of 17 | Patient, Age of 27 | Patient’s Mother | Patient’s Father |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APTT, sec (22–29) | 51.7 | 48.9 | 32 | 34.3 |

| FVIII:C, % (50–150) | 19.9 | 12.7 | 114.3 | 135.1 |

| PTI, % (70–130) | 85.9 | 71 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| vWF:C, % (50–160) | 67 | 77.4 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| vWF:Ag, % (50–150) | 105 | nd 1 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| FIX:C, % (65–150) | 90.3 | 81.9 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| FXI:C, % (65–150) | nd 1 | 78 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| FXII:C, % (50–150) | nd 1 | 113.4 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| AT III, % (80–130) | nd 1 | 93 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| Protein C, % (70–140) | nd 1 | 82 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

| Fibrinogen concentration, g/L (2.00–3.93) | 2.95 | 2.61 | nd 1 | nd 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pshenichnikova, O.; Salomashkina, V.; Yastrubinetskaya, O.; Surin, V.; Mishina, O.; Alimova, G.; Obukhova, T.; Zozulya, N. A Rare Case of Mild Hemophilia A in a Female with Mosaic Monosomy X and a De Novo F8 Variant. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411899

Pshenichnikova O, Salomashkina V, Yastrubinetskaya O, Surin V, Mishina O, Alimova G, Obukhova T, Zozulya N. A Rare Case of Mild Hemophilia A in a Female with Mosaic Monosomy X and a De Novo F8 Variant. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411899

Chicago/Turabian StylePshenichnikova, Olesya, Valentina Salomashkina, Olga Yastrubinetskaya, Vadim Surin, Olesya Mishina, Galina Alimova, Tatiana Obukhova, and Nadezhda Zozulya. 2025. "A Rare Case of Mild Hemophilia A in a Female with Mosaic Monosomy X and a De Novo F8 Variant" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411899

APA StylePshenichnikova, O., Salomashkina, V., Yastrubinetskaya, O., Surin, V., Mishina, O., Alimova, G., Obukhova, T., & Zozulya, N. (2025). A Rare Case of Mild Hemophilia A in a Female with Mosaic Monosomy X and a De Novo F8 Variant. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411899