Abstract

Anal cancer is high in men who have sex with men living with human immunodeficiency virus (MSM-LWHIV). This cancer is strongly associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infection. Anal cancer screening using cytology and high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) for diagnosis of anal intraepithelial neoplasia requires specialized expertise. Biomarkers for the diagnosis of abnormal anal cells are of interest. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) methylation at cg01009664 was detected using a pyrosequencing assay to compare methylation patterns among different anal lesions. Our results demonstrated that TRH methylation was significantly hypermethylated in anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN3) (>20%) and AIN1-2 (>10%) but less methylated in normal (<10%) (p < 0.001). TRH gene methylation showed higher sensitivity than the cytology for predicting AIN1+ (75.96% vs. 25.37%, respectively) and AIN2+ (78.95%% vs. 19.23%, respectively). There was no significant correlation between TRH methylation and the percentage of CD4 in patients with HIV (p > 0.05). TRH methylation in anal swabs reflects the presence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Methylation analysis showed higher sensitivity than cytology for high-grade lesions and was independent of immune status. These findings support its use as a screening tool to preselect patients for HRA, potentially reducing unnecessary procedures while maintaining diagnostic accuracy.

1. Introduction

Anal cancer, although relatively rare, is of significant concern due to its increasing incidence among men who have sex with men living with human immunodeficiency virus (MSM-LWHIV), women with HIV, MSM without HIV, women with a history of cervical/vaginal/vulva cancers and precancers, and non-HIV immunosuppressed people such as solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) [1,2,3,4]. This cancer is strongly associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infection, particularly HPV16 [5,6], which plays a crucial role in its pathogenesis. People in an immunocompromised state, such as those with primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs), solid organ transplant recipients of immunosuppression and acquired immunodeficiency, e.g., HIV infection, are particularly vulnerable for HPV-related diseases, with incidence rates markedly higher compared to the general population [7,8]. Anal cancer screening can be detected by anal cytology and high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) with directed biopsy for histology examination. Anal cytology is diagnosed with different lesions, including negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high grade (ASC-H), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), and anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC) [9]. Anal cytology and HR-HPV tests have good sensitivity but limited specificity [2,9]. The sensitivity of anal cytology for detecting AIN ranges from 47% to 90%, with higher sensitivity observed in more advanced lesions. However, its specificity is lower, ranging from 32% to 60% [10,11,12]. HRA is still the gold-standard diagnostic method for anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN), but its use is limited due to the need for specific training and resources [13].

The prevalence of AIN2+ was the highest among MSM-LWHIV and persons living with HIV (PLWH) [14]. It has been reported that treating anal precancerous HSIL significantly reduces risk of progression to anal cancer among PLWH [15]. The current anal cancer screening depends on cytological and histological examinations which require specialized expertise. Biomarkers for abnormal anal cell diagnosis are of interest.

Previous studies have shown that hypermethylation of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) gene was detected in oral and oropharyngeal cancer [16]. It can also be used to identify high-grade cervical lesions or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+) [17]. It would be interesting to detect TRH gene methylation in other HPV-related cancers. The TRH gene is located on chromosome 3 and is a tripeptide hormone (pGlu-His-Pro-NH2) that is mainly produced in the hypothalamus and stimulates the synthesis and release of Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) as well as the synthesis of prolactin (PRL). It is crucial for controlling metabolism, energy balance, and hormone secretion. It is also found in other peripheral tissues, including the cervix [18]. Beyond its endocrine functions, TRH has been linked to cancer development and progression. TRH has been found as a potential biomarker in breast cancer [18], acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [19], and melanoma [20].

Initially, the GSE186859 dataset of anal samples [21] retrieved from NCBI was analyzed and it was found that the TRH gene at cg01009664 was hypermethylated in AIN3/anal cancer samples compared to normal cells.

Therefore, we further validated this finding in clinical anal samples with different lesion severity using a pyrosequencing assay to detect the TRH methylation at cg01009664. The diagnostic performance of the assay was analyzed.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of GSE186859 Dataset and TRH Methylation in Cervical Cell Lines

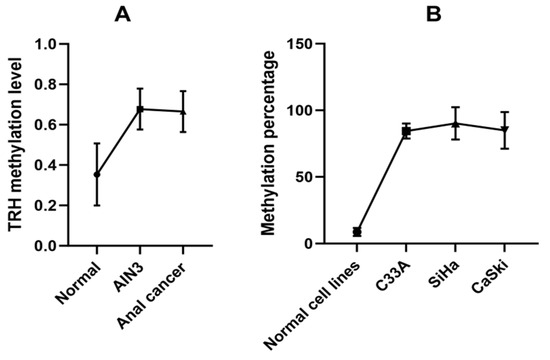

The GSE186859 dataset of methylation comprised over 485,513 CpG positions was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets. The dataset includes samples from 9 normal, 13 AIN3, and 121 anal cancer cases. The GEO2R tool was used for differential methylation analysis between normal and AIN3/CA samples and log2FC ≥ 0.3 was used as cut-off to identify highly methylated CpG positions. There were 2088 CpG positions (t > 3 and p < 0.05), representing 537 genes, which are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The STRING database was used to analyze gene ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway analysis. The significant KEGG pathways included neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction and cAMP signaling pathway. The biological processes (BPs) included nervous system development, system development, multicellular organism development and cell–cell signaling. The molecular functions (MFs) included DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II transcription regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding and transcription regulator activity. Cellular components (CCs) predominantly involved synaptic membrane, cell junction and intrinsic component of plasma membrane. All GO and KEGG pathway of 537 genes are listed in Supplementary Table S2. TRH, which is involved in neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction, is primarily found in the cell periphery and plasma membrane. Its functions include binding, receptor–ligand activity, and signaling receptor regulator activity. It is also involved in biological processes such as cell–cell signaling, multicellular organismal processes, and cellular process regulation. Our group has previously shown that cg01009664 position of TRH gene was substantially methylated in cervical cancer cases when compared to normal cervical cells [17]. The cg01009664 position in the anal sample GSE186859 dataset was analyzed and we found that it was markedly methylated in ≥AIN3 cells when compared to normal anal cells as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

TRH methylation analysis. (A) Data obtained from GSE186859 dataset, methylation levels at cg01009664 of TRH gene in anal cells with different anal lesions stratified by histology as normal (9 samples), AIN3 (13 samples) and anal cancer (121 samples). (B) Pyrosequencing analysis data of normal and cervical cancer cell lines.

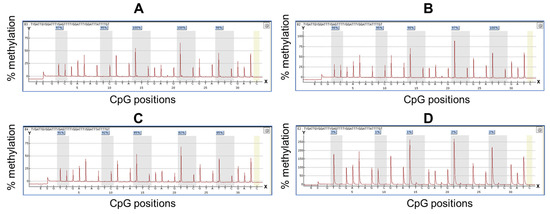

To analyze TRH gene methylation at the cg01009664 position using the pyrosequencing assay, we first tested the assay in normal and cervical cancer cell lines, which showed low and high TRH methylation levels, respectively, as shown in Figure 1B. Pyrogram of five CpGs of CaSki, SiHa and C33A cervical cancer cell lines showed high methylation levels (80–100%) while normal cervical cell lines revealed low methylation levels (<10%) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pyrogram from TRH methylation quantification by pyrosequencing. Y-axis represents percentage of methylation, X-axis represents CpG positions. The yellow bar represents the unmethylated cytosine control within the analyzed sequence. The methylation percentage values of each CpG site were shown in the box on the top of the gray bar. (A–D) are pyrogram results obtained from four cell lines including (A) CaSki, (B) SiHa, (C) C33A and (D) normal cervical cell lines PCS480011.

2.2. Analysis of TRH Methylation in Anal Samples

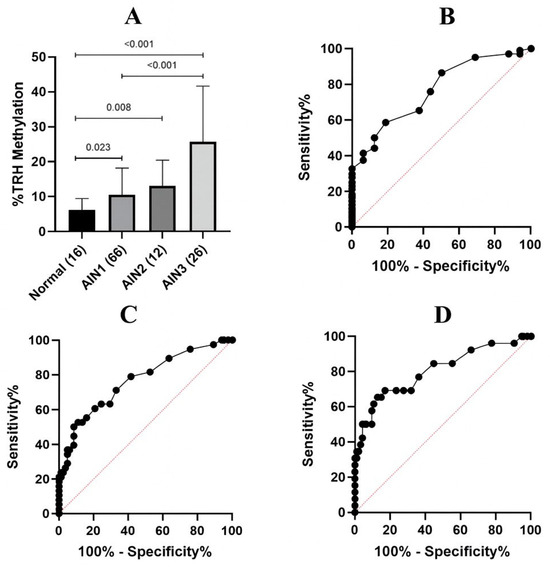

Methylation analysis was performed by comparing between the normal, AIN1, AIN2 and AIN3 samples; the average TRH methylation levels of five CpGs of each group were 6.5%, 10.58%, 13.0%, and 25.65%, respectively (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences in average TRH methylation among the groups (p < 0.001) (Figure 3A).

Table 1.

The percentage of TRH methylation of each CG using pyrosequencing.

Figure 3.

TRH methylation analysis in anal samples with different lesion severity. (A) Average methylation percentage of five CpGs at cg01009664 of TRH gene in anal samples stratified by histology as normal, AIN1, AIN2 and AIN3. Error bars in the bar graph represent the mean with standard deviation (SD). There were statistically significant differences among the groups (p < 0.001). Error bars in the bar graph represent the mean with standard deviation (SD). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the differences among the groups. (B) ROC of average TRH methylation of five CpGs to differentiate between normal and AIN1+ lesions. AUC was 0.7674 (95% CI: 0.6544–0.8804) (p-value = 0.0006). (C) ROC of average TRH methylation of five CpGs to differentiate between ≤AIN1 and AIN2+ lesions. AUC was 0.7667 (95% CI: 0.6728–0.8606) (p-value = 0.0001). (D) ROC of average TRH methylation of five CpGs to differentiate between ≤AIN2 and AIN3 lesions. AUC was 0.8048 (95% CI: 0.6991–0.9106) (p-value = 0.0001).

ROC analysis was performed comparing average TRH methylation levels between two groups of three models, namely normal vs. AIN1-3, ≤AIN1 vs. AIN2+, and ≤AIN2 vs. AIN3; the areas under the ROC curve (AUC) were 0.7674, 0.7667, and 0.8048, respectively (Figure 3B–D). The sensitivity and specificity data obtained from ROC analysis are presented in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3. The TRH methylation cut-off values considered optimal in the present study which have the acceptable sensitivity (>70%) and specificity (>50%) were 6.5% of normal vs. AIN1-3, 8.5% of ≤AIN1 vs. AIN2+, and 8.5% of ≤AIN2 vs. AIN3, as highlighted in Table 2. The AUC values, sensitivity and specificity for individual CpG are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3, respectively.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of TRH methylation at different cut-off points obtained from ROC analysis to compare average TRH methylation levels of five CpGs of three models, namely normal and AIN1-3, ≤AIN1 and AIN2+ and ≤AIN2 and AIN3.

2.3. Diagnostic Performance of Cytology and TRH Methylation in Detecting for AIN1+, AIN2+ and AIN3 Lesions

The diagnostic performance of cytology and TRH methylation was calculated according to the histological results as a gold standard for AIN diagnosis. The diagnostic performance of cytology in predicting AIN1+ and AIN2+ lesions demonstrated a low sensitivity (25.37% and 19.23%, respectively) but a 100% specificity. The positive predictive value (PPV) was 100%, showing that most positive cytology (LSIL and HSIL) results correctly identified true positives (AIN1+ and AIN2+). The negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy for predicting AIN2+ were higher than detecting AIN1+ (72% vs. 20.63% for NPV and 73.75% vs. 37.50% for accuracy) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy of each test to predict AIN1+, AIN2+ and AIN3 lesions.

The average of TRH methylation values of 6.5%, 8.5% and 8.5% was used to evaluate their diagnostic performance in detecting for AIN1+, AIN2+ and AIN3, respectively. The selected methylation cut-off values were applied to classify each sample as either “positive” (methylation above the cut-off) or “negative” (methylation below the cut-off). These binary classifications were compared with histological diagnoses using 2 × 2 contingency tables, from which sensitivity and specificity were calculated for each diagnostic model and cut-off point. The highest sensitivity was found in detecting AIN3, followed by AIN2+ and AIN1+. However, the accuracy in detecting AIN1+ was higher than detecting AIN2+ and AIN3. The results showed that the TRH methylation demonstrated greater sensitivity and accuracy than the cytology to predict abnormal anal cells. The TRH methylation cut-off value of 6.5% of the average TRH methylation also exhibited higher accuracy than the cytology for predicting AIN1+, improving from 37.50% to 73.33% (Table 3). To increase the specificity and PPV of the TRH methylation, the increased cut-off point was analyzed to evaluate the diagnostic performance; however, the sensitivity and NPV were decreased as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy of TRH methylation at different cut-off points to predict AIN1+, AIN2+ and AIN3 lesions.

To improve the screening test for anal cancer, the combination of cytology and/or TRH methylation was evaluated. Positive cytology or TRH methylation results showed higher sensitivity (80.60% and 83.33%) and accuracy (75.00% and 65.00%) in detecting AIN1+ and AIN2+, respectively, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy of each combined test to predict AIN1+ and AIN2+ lesions.

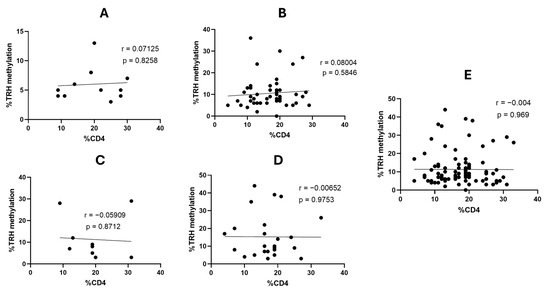

2.4. TRH Methylation Is Not Associated with HIV Status and CD4 Levels

We further investigated whether HIV status and CD4 percentage have an effect on TRH methylation or not; it was found that TRH methylation levels at all five CG positions, as well as the average methylation across these CGs, gradually increased from normal to AIN3 (Table 6). There was no significant correlation with the percentage of CD4 in patients with HIV (p > 0.05 for all comparisons, Figure 4). However, the percentage of TRH gene methylation in patients with HIV increased significantly with disease progression, from normal to AIN3 lesions (p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Mean TRH methylation level of each CpG and the percentage of CD4 count between patients with HIV and patients without HIV.

Figure 4.

Correlation between the percentage of TRH methylation and the percentage of CD4 counts in patients with HIV with different AIN lesions. (A) Normal (12 samples), (B), AIN1 (49 samples), (C) AIN2 (10 samples), (D) AIN3 (25 samples) and (E) all 96 samples.

3. Discussion

The present study focused on TRH methylation in the MSM group, particularly MSM-LHIV because it has a higher risk of developing anal cancer than in HIV-negative MSM [8,22]. In Thailand, the HIV prevalence among MSM was high, especially in Bangkok [23,24,25,26]. A high incidence of new HIV infections was observed among young MSM with age ≤ 22 years [27]. High-grade AIN was also highly detected in MSM with and without HIV [28]. Due to the anal cancer incidence being high in MSM and transgender women (TW) with HIV, the anal cancer screening for HIV-positive TW and MSM should begin around age 35. For MSM and TW who are HIV-negative and other HIV-positive individuals, screening should begin at age 45 [9]. The routine screening of anal cancer is anal cytology alone or co-testing (anal cytology and HPV testing) for early diagnosis of cancer and its precursor lesions. Individuals with abnormal results, such as ASCUS, LSIL with HR-HPV positive, and those with ASC-H or HSIL cytology, are referred to HRA, and biopsies should be collected [29]. However, the specificity of cytology and HPV testing was low [11,30]. HRA is considered the gold standard for diagnosing high-grade AIN and anal cancer, but it is invasive, time-consuming, requires expert skill, and is not feasible for resource-limited settings or low- to middle-income countries [10,11,12,31,32,33,34]. Molecular biomarkers, such as host DNA methylation, which reflects epigenetic changes occurring during the transition from normal tissue to precancerous and cancerous lesions, have been studied in many cancer types [35,36,37,38].

In this study, we demonstrated that the methylation levels of the TRH gene at cg01009664 in anal cells correlate with the progression of anal precancerous lesions that could be used to differentiate between normal and low-grade (AIN1-2) to high-grade (AIN3) lesions. TRH methylation may serve as a biomarker for predicting anal lesion severity. This is particularly important because high-grade lesions (AIN2+) have a higher risk of progressing to anal carcinoma [32,39,40,41,42] and identifying these at an earlier stage can reduce the incidence of anal cancer. The results of the present study is consistent with previous studies that TRH hypermethylation was detected in oral and oropharyngeal cancer and cervical cancer [16,17]. The present study had a high AUC of TRH methylation for predicting AIN2+ and AIN3+ lesions (0.7667 vs. 0.8048, respectively). The present study has shown that single TRH methylation has a high AUC for predicting AIN2+ and AIN3+.

In comparison, a meta-analysis of viral and host gene methylation found that the pooled AUC for the diagnosis of AIN2+ was 0.68 (0.63–0.73) [43], which is lower than the present study. Many studies reported that methylation panels could increase the AUC for predicting AIN3+ in HIV-positive groups, such as LHX8 and ZNF582 or ASCL1 and ZNF582 panels, which revealed AUCs of 0.70 and 0.69, respectively. The single-gene methylation marker had a low AUC range from 0.55 to 0.68 for identifying HSIL cases [44]. A marker panel of FMN2 and ASCL1 (AUC of 0.725) showed better diagnostic performance than FMN2 or ASCL1 alone (AUCs of 0.723 and 0.658, respectively) for prediction of HSIL (AIN2-3) [45]. A marker panel of ASCL1 and ZIC1 had an AUC of 0.85 for prediction of AIN3+ [46]. A five-marker panel including ASCL1, ST6GALNAC3, WDR17, ZIC1, and ZNF582 had an AUC of 0.90 for prediction of AIN3+ [47]. Another marker panel consisting of ASCL1, SST, and ZNF582 showed an AUC of 0.89 [48]. The present study has shown that single TRH methylation has a high AUC for predicting AIN2+ and AIN3+. TRH represents a single-gene methylation marker that may provide a simpler, more cost-effective, and more accessible assay while maintaining diagnostic performance that is comparable to or better than other panel tests mentioned above. Importantly, TRH hypermethylation has been consistently observed in many HPV-related cancers, including oral and cervical cancer [16,17].

Our study showed that there was no correlation between CD4 counts and TRH methylation in any anal lesions; however, it was found at CG position 5 showed moderate correlation between AIN3 and CD4 percentage (r = 0.6372, Supplementary Figure S1). One study reported that there was moderate correlation between some CG positions of HPV16 L1 gene and CD4 count in high-grade AIN HIV-positive patients [49].

The elevated methylation levels in high-grade anal lesions indicated its association with the progression of dysplastic and neoplastic lesions as shown by a previous study that endothelin 3 (EDN3) silencing by methylation promotes cervical cancer cell proliferation and invasion [50]. The gradual increase in methylation from normal to AIN1-2 and AIN3 highlights the potential of the TRH gene as a dynamic marker that reflects the severity of cellular abnormalities in the anal cells. Further research is needed to explore the role of TRH methylation in AIN progression and its potential interaction with other molecular pathways involved in anal carcinogenesis.

However, this study has limitations, including small sample sizes, which may weaken the strength of the findings. More research with larger sample sizes is required to confirm that the findings may be used in clinical settings for distinguishing normal cells from AIN and cancer. In conclusion, our study highlights the potential of TRH methylation as a biomarker for identifying and differentiating AIN lesions, indicating the possibility of enhanced diagnostics in anal neoplasia management. As a result, TRH methylation may help to reduce the need for immediate referral to HRA or to help clinicians in deciding whether patients should be referred for HRA or not.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Clinical Samples and Cell Lines

The present study is a retrospective study of 120 archived DNA samples extracted from anal cells including 16 negatives for malignancy, 66 AIN I, 12 AIN II and 26 AIN III. There were 96 HIV-positive samples and 24 HIV-negative samples. These samples were collected from MSM at the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre (TRC-ARC), Bangkok, Thailand, during May to December 2013. All of the samples were anonymized and bisulfite-treated DNA samples were leftovers from a previous study [49]; therefore, informed consent was not required. The DNA extracted from human cervical cancer cell lines containing HPV16, i.e., CaSki (ATCC CRL-1550, Manassas, VA, USA) and SiHa (ATCC HTB-35, Manassas, VA, USA), human cervical cancer cell line without HPV; C33A (ATCC HTB-31, Manassas, VA, USA), and normal human cervical epithelial cells, PCS480011 (ATCC PCS-480-011™, Manassas, VA, USA) were used as a control for hypermethylated and hypomethylated TRH gene. The DNA samples were used for bisulfite treatment using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA).

We retrieved methylation profiling by genome tiling array GSE186859 data by accessing GENBANK on 30 January 2024 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, the data was available in NCBI on 29 November 2021), using the GPL13534 Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip platform (HumanMethylation450_15017482, Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). There were 143 FFPE anal samples including 121 invasive tumors, 13 adjacent AIN3 and 9 adjacent normal [21]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (COA No. 0191/2025, IRB No. 0043/68, Date of approval: 6 February 2025), and the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (MDCU-IBC001/2025, Effective date: 17 February 2025).

4.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction of Bisulfite-Treated DNA

The EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to bisulfite treatment following the manufacturer’s procedure. The sequences of forward, reverse, and sequencing primers were as follows: Forward Primer—5′-GGGGTTTTTAGAGTTGTAGATTTTTGA-3′; Reverse Primer—Biotin 5′-CCAAAAATAAACTCCACAAAATAAATC-3′. The TRH sequencing primer was 5′-TTTAGAGTTGTAGATTTTTGATTTG-3′ and the sequence to analyze was TYGATTGYGGATTTYGAGTTTTYGGATTTYGGATTTATTTTGT; bisulfite-treated DNA in each sample was used for PCR using TaKaRa EpiTaq™ HS (Cat. #R110A, Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). Reagent concentrations per 25 µL reaction tube were as follows: 1X of 10XEpiTaq PCR Buffer (Mg2+ free), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM dNTPs (2.5 mM each), 0.8 µM each primer, 0.625 U Taq polymerase (TaKaRa EpiTaq HS), 2 µL of bisulfite-treated DNA each sample and DNase/RNase-free water were added to the final volume of 25 µL. The PCR amplification was started with an initial denaturing at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 45 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 53 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min, and a cycle for the final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were detected by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

4.3. Methylation Analysis by a Pyrosequencing Assay

Pyrosequencing was performed using the PSQ96MA System (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, prior to pyrosequencing, 20 µL of biotin-labeled amplified products were mixed with beads, washed with 70% ethanol, denatured, washed and mixed with 0.4 µM of sequencing primers and loaded into the PyroMark™ Q96 machine (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Following the run, the program will calculate each CpG site’s percentage of methylation level, as shown in the pyrogram analysis. The bisulfite conversion control, which indicates that a single cytosine is entirely converted to uracil, is shown by a yellow bar. The sequence’s investigated CpG sites are shown by the gray bar. On top of the gray bar, each CpG site that passes the quality check has its percentage of methylation level shown in blue.

4.4. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of TRH methylation across three clinically relevant comparison models: (1) Normal vs. AIN1–3 represents a primary screening distinction between lesion-free individuals and those with any grade of AIN (2) ≤AIN1 vs. AIN2+ is a triage threshold used to identify individuals who may require referral for high-resolution anoscopy, as AIN2+ represents high-grade disease; and (3) ≤AIN2 vs. AIN3 differentiates the most advanced precancerous lesions with the greatest likelihood of progression. Average methylation percentages of each sample with different anal lesions obtained from pyrosequencing were analyzed as continuous variables. ROC curves, the area under the curve (AUC) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and sensitivity and specificity were generated using GraphPad Prism 10.0.3 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

To further characterize diagnostic accuracy, the selected methylation cut-off values that showed the best sensitivity and specificity derived from the ROC curves were applied to each comparison model. For each cut-off, TRH methylation values above the cut-off value were classified as positive, and values below the cut-off value were classified as negative. The diagnostic performance of TRH methylation was also compared with cytology using histology as the reference standard. These binary classifications were compared with histological diagnoses using 2 × 2 contingency tables. All diagnostic indices were calculated using the MedCalc Diagnostic Test Calculator (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium; available online at https://www.medcalc.org/en/calc/diagnostic_test.php; accessed on 6 February 2025).

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.3 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All information was analyzed as a mean and percentage. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to evaluate the diagnostic capability of TRH methylation levels in distinguishing between normal and AIN1+. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to examine the differences in the mean percentage of methylation levels among groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to analyze the association between the percentage of methylation and the CD4 and %CD4 count. A statistically significant difference was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262411784/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.; Investigation and methodology, C.P.; Formal analysis, C.P. and A.C.; Resources, N.P. and T.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, C.P. and A.C.; Guidance on data analysis and interpretation, B.L., P.B., N.K. and S.B.; Writing—review and editing, P.B., N.K., S.B. and A.C.; Supervision, N.K., S.B. and A.C.; Project administration, A.C.; Funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is supported by The Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University. This work was supported by the Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund (65413000120839 RCU_68_025_3000_001), Chulalongkorn University. The 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Scholarship, Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (COA No. 0191/2025, IRB No. 0043/68, Date of approval: 6 February 2025), and the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (MDCU-IBC001/2025, Effective date: 17 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data used in this research would be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Scholarship, Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, and Ratchadapiseksompotch Endowment Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. This research was also supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University. We would like to thank all members of the Center of Excellence in Applied Medical Virology (CEAMV), Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, for their efforts in conducting the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AIN | Anal intraepithelial neoplasia |

| ASC-H | Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL |

| ASC-US | Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| HRA | High-resolution anoscopy |

| HSIL | High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LSIL | Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| MSM-LWHIV | Men who have sex with men living with HIV |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| TRH | Thyrotropin-releasing hormone |

References

- Clifford, G.M.; Georges, D.; Shiels, M.S.; Engels, E.A.; Albuquerque, A.; Poynten, I.M.; de Pokomandy, A.; Easson, A.M.; Stier, E.A. A meta-analysis of anal cancer incidence by risk group: Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, A.; Brunetti, T.; Orioni, G.; Gaspari, V. Screening of Anal HPV Precancerous Lesions: A Review after Last Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Prasad-Hayes, M.; Ganz, E.M.; Poggio, J.L.; Lenskaya, V.; Malcolm, T.; Deshmukh, A.; Zheng, W.; Sigel, K.; Gaisa, M.M. HIV-positive women with anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: A study of 153 cases with long-term anogenital surveillance. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscicki, A.B.; Darragh, T.M.; Berry-Lawhorn, J.M.; Roberts, J.M.; Khan, M.J.; Boardman, L.A.; Chiao, E.; Einstein, M.H.; Goldstone, S.E.; Jay, N.; et al. Screening for Anal Cancer in Women. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2015, 19 (Suppl. S1), S27–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Franceschi, S.; Clifford, G.M. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the anus, according to sex and HIV status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Rasizadeh, R.; Jafari, S.; Baghi, H.B. Prevalence of HPV in anal cancer: Exploring the role of infection and inflammation. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2024, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewavisenti, R.V.; Arena, J.; Ahlenstiel, C.L.; Sasson, S.C. Human papillomavirus in the setting of immunodeficiency: Pathogenesis and the emergence of next-generation therapies to reduce the high associated cancer risk. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1112513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljak, M.; Šterbenc, A.; Lunar, M. Prevention of human papillomavirus (HPV)—Related tumors in people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, E.A.; Clarke, M.A.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Wentzensen, N.; Liu, Y.; Poynten, I.M.; Cavallari, E.N.; Fink, V.; Barroso, L.F.; Clifford, G.M.; et al. International Anal Neoplasia Society’s consensus guidelines for anal cancer screening. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, M.; Singh, N.; Garrett, N.; Hickey, N.; Prevost, T.; Sheaff, M. Performance of anal cytology in a clinical setting when measured against histology and high-resolution anoscopy findings. AIDS 2010, 24, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, I.L.; Fang, S.H. Anal cancer and intraepithelial neoplasia screening: A review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.A.; Seet, J.E.; Stebbing, J.; Francis, N.; Barton, S.E.; Strauss, S.; Allen-Mersh, T.G.; Gazzard, B.G.; Bower, M. The value of anal cytology and human papillomavirus typing in the detection of anal intraepithelial neoplasia: A review of cases from an anoscopy clinic. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2005, 81, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, L.; Etienney, I.; Abramowitz, L.; de Parades, V.; Pigot, F.; Siproudhis, L.; Adam, J.; Balzano, V.; Bouchard, D.; Bouta, N.; et al. Screening for precancerous anal lesions linked to human papillomaviruses: French recommendations for clinical practice. Tech. Coloproctol. 2024, 28, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geba, M.; Cardenas, B.; Williams, B.; Hoang, S.; Newberry, Y.; Dillingham, R.; Thomas, T.A. Prevalence and Predictors of High-Grade Anal Dysplasia in People With HIV in One Southeastern Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Clinic. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palefsky, J.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Jay, N.; Goldstone, S.E.; Darragh, T.M.; Dunlevy, H.A.; Rosa-Cunha, I.; Arons, A.; Pugliese, J.C.; Vena, D.; et al. Treatment of Anal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions to Prevent Anal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttipanyalears, C.; Arayataweegool, A.; Chalertpet, K.; Rattanachayoto, P.; Mahattanasakul, P.; Tangjaturonsasme, N.; Kerekhanjanarong, V.; Mutirangura, A.; Kitkumthorn, N. TRH site-specific methylation in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiwongkot, A.; Buranapraditkun, S.; Oranratanaphan, S.; Chuen-Im, T.; Kitkumthorn, N. Efficiency of CIN2+ Detection by Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) Site-Specific Methylation. Viruses 2023, 15, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, E.; Wahl, R. The forgotten effects of thyrotropin-releasing hormone: Metabolic functions and medical applications. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 52, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.F.; Mao, J.Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.P. Identification of the Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) as a Novel Biomarker in the Prognosis for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerhorst, J.A.; Naderi, A.A.; Johnson, M.K.; Pelletier, P.; Prieto, V.G.; Diwan, A.H.; Johnson, M.M.; Gunn, D.C.; Yekell, S.; Grimm, E.A. Expression of thyrotropin-releasing hormone by human melanoma and nevi. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 5531–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, E.M.; Ajidahun, A.; Berglund, A.; Guerrero, W.; Eschrich, S.; Putney, R.M.; Magliocco, A.; Riggs, B.; Winter, K.; Simko, J.P.; et al. Genome-wide host methylation profiling of anal and cervical carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.A.; Lin, Y.Y.; Damgacioglu, H.; Shiels, M.; Coburn, S.B.; Lang, R.; Althoff, K.N.; Moore, R.; Silverberg, M.J.; Nyitray, A.G.; et al. Recent and projected incidence trends and risk of anal cancer among people with HIV in North America. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansom, T.; Muangnoicharoen, S.; Nitayaphan, S.; Kitsiripornchai, S.; Crowell, T.A.; Francisco, L.; Gilbert, P.; Rwakasyaguri, D.; Dhitavat, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Risk Factors for HIV sero-conversion in a high incidence cohort of men who have sex with men and transgender women in Bangkok, Thailand. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekaew, P.; Pengnonyang, S.; Jantarapakde, J.; Sungsing, T.; Rodbumrung, P.; Trachunthong, D.; Cheng, C.L.; Nakpor, T.; Reankhomfu, R.; Lingjongrat, D.; et al. Characteristics and HIV epidemiologic profiles of men who have sex with men and transgender women in key population-led test and treat cohorts in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmonde, S.; Lolekha, R.; Costantini, S.; Siraprapasiri, T.; Frank, S.; Bakkali, T.; Benjarattanaporn, P.; Hou, T.; Jantaramanee, S.; Kuttiparambil, B.; et al. A focused multi-state model to estimate the pediatric and adolescent HIV epidemic in Thailand, 2005–2025. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thepthien, B.O.; Srivanichakorn, S.; Udomsubpayakul, U.; Sein Win, Z.Z.K.; Zaw, A.M.M. HIV risk behavior and testing among MS M in Bangkok 2015–2019: A short report. AIDS Care 2022, 34, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.J.; Schieber, E.; Janamnuaysook, R.; Wang, B.; Gunasekar, A.; MacDonell, K.; Getwongsa, P.; Kim, D.; Wongharn, P.; Phanuphak, N. Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and adherence among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Thailand: A qualitative study. AIDS Care 2024, 36, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanuphak, N.; Teeratakulpisarn, N.; Triratanachat, S.; Keelawat, S.; Pankam, T.; Kerr, S.J.; Deesua, A.; Tantbirojn, P.; Numto, S.; Phanuphak, P.; et al. High prevalence and incidence of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia among young Thai men who have sex with men with and without HIV. Aids 2013, 27, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grennan, T.; Salit, I.E. Anal cancer screening. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2024, 196, E1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, J.; Fuller, C.; Burris, K. Anal cancer screening and prevention: A review for dermatologists. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, P.; Barquet-Muñoz, S.; Jay, N.; Mendoza, M.J.; Moctezuma, P.; Morales-Aguirre, M.; Pérez-Montiel, D.; Larraga, V.; Martin-Onraet, A. Challenges in the implementation of a high-resolution anoscopy clinic for people with HIV in an oncologic center in Mexico City. AIDS Res. Ther. 2025, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Pria, A.; Alfa-Wali, M.; Fox, P.; Holmes, P.; Weir, J.; Francis, N.; Bower, M. High-resolution anoscopy screening of HIV-positive MSM: Longitudinal results from a pilot study. AIDS 2014, 28, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, C.S.; da Silva Filho, E.V.; Segurado, A.A.; Genevcius, R.F.; Gerhard, R.; Gutierrez, E.B.; Marques, C.F.; Cecconello, I.; Nahas, S.C. Screening anal dysplasia in HIV-infected patients: Is there an agreement between anal pap smear and high-resolution anoscopy-guided biopsy? Dis. Colon Rectum 2009, 52, 1854–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, K.J.; Valderrama-Beltrán, S.L.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Juillard, C.; Amaya, L.J.L. Anal cancer screening in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, J.; Peeters, M.; Van Camp, G.; Op de Beeck, K. Methylation biomarkers for early cancer detection and diagnosis: Current and future perspectives. Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 178, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hum, M.; Lee, A.S.G. DNA methylation in breast cancer: Early detection and biomarker discovery through current and emerging approaches. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wu, H. Research progress of DNA methylation in the screening of cervical cancer and precancerous lesions. Interdiscip. Med. 2025, 3, e20240043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, H.; Hu, N.; Li, T. Methylomics and cancer: The current state of methylation profiling and marker development for clinical care. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, M.T.; Frederiksen, K.; Palefsky, J.M.; Kjaer, S.K. Risk of Anal Cancer Following Benign Anal Disease and Anal Cancer Precursor Lesions: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.T.; Frederiksen, K.; Palefsky, J.M.; Kjaer, S.K. A nationwide longitudinal study on risk factors for progression of anal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 to anal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegunta, S.; Shah, A.A.; Whited, M.H.; Long, M.E. Screening Women for Anal Cancers: Guidance for Health Care Professionals. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.J.; Smith, B.B.; Whitehead, M.R.; Sykes, P.H.; Frizelle, F.A. Malignant progression of anal intra-epithelial neoplasia. ANZ J. Surg. 2006, 76, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresu, N.; Puci, M.V.; Sotgiu, G.; Sechi, I.; Cossu, A.; Usai, M.; Piana, A.F. Diagnostic Performance of Host and Viral DNA Methylation Analysis in the Identification of Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias Gonçalves Lima, F.; Rozemeijer, K.; van der Zee, R.P.; Dick, S.; Ter Braak, T.J.; Geijsen, D.E.; Meijnen, P.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; van Noesel, C.J.M.; de Vries, H.J.C.; et al. DNA methylation analysis on anal swabs for anal cancer screening in people living with HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 232, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasavada, A.; Stankiewicz Karita, H.C.; Lin, J.; Schouten, J.; Hawes, S.E.; Barnabas, R.V.; Wasserheit, J.; Feng, Q.; Winer, R.L. Methylation markers for anal cancer screening: A repeated cross-sectional analysis of people living with HIV, 2015–2016. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 155, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zee, R.P.; van Noesel, C.J.M.; Martin, I.; Ter Braak, T.J.; Heideman, D.A.M.; de Vries, H.J.C.; Prins, J.M.; Steenbergen, R.D.M. DNA methylation markers have universal prognostic value for anal cancer risk in HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 3024–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, R.P.; Richel, O.; van Noesel, C.J.M.; Novianti, P.W.; Ciocanea-Teodorescu, I.; van Splunter, A.P.; Duin, S.; van den Berk, G.E.L.; Meijer, C.; Quint, W.G.V.; et al. Host Cell Deoxyribonucleic Acid Methylation Markers for the Detection of High-grade Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Anal Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, R.P.; Richel, O.; van Noesel, C.J.M.; Ciocănea-Teodorescu, I.; van Splunter, A.P.; Ter Braak, T.J.; Nathan, M.; Cuming, T.; Sheaff, M.; Kreuter, A.; et al. Cancer Risk Stratification of Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Men by Validated Methylation Markers Associated with Progression to Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 2154–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwongkot, A.; Phanuphak, N.; Pankam, T.; Bhattarakosol, P. Human papillomavirus 16 L1 gene methylation as a potential biomarker for predicting anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men who have sex with men (MSM). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, J.; Yuan, D.; Chen, Y.; Luo, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Nie, Q.; et al. Methylation-mediated silencing of EDN3 promotes cervical cancer proliferation, migration and invasion. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1010132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).