Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Substitutions Underlying Tetrodotoxin Resistance in Nemerteans: Ecological and Evolutionary Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

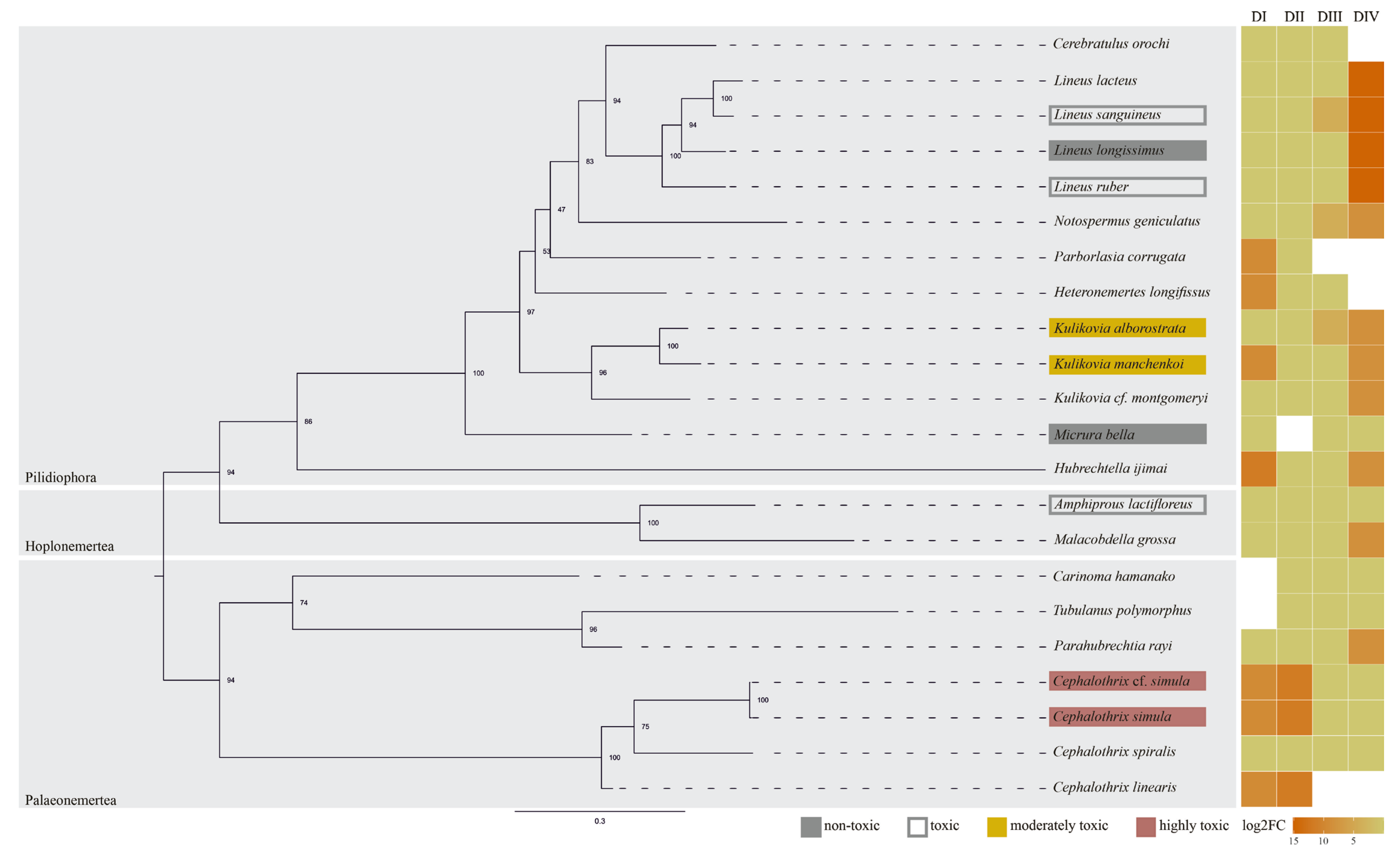

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bioinformatic Analysis of NaV1 Sequences and Primer Design for the Selectivity Filter Regions

4.2. Specimens Collection and Identification

4.3. RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

4.4. PCR Amplification of Selective Filter Regions of the NaV1 Channel Gene

4.5. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bane, V.; Lehane, M.; Dikshit, M.; O’Riordan, A.; Furey, A. Tetrodotoxin: Chemistry, toxicity, source, distribution and detection. Toxins 2014, 6, 693–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lago, J.; Rodriguez, L.P.; Blanco, L.; Vieites, J.M.; Cabado, A.G. Tetrodotoxin, an extremely potent marine neurotoxin: Distribution, toxicity, origin and therapeutical uses. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6384–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Qiao, K.; Cui, R.; Xu, M.; Cai, S.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Z. Tetrodotoxin: The state-of-the-art progress in characterization, detection, biosynthesis, and transport enrichment. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magarlamov, T.Y.; Melnikova, D.I.; Chernyshev, A.V. Tetrodotoxin-producing bacteria: Detection, distribution and migration of the toxin in aquatic systems. Toxins 2017, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xie, L.; Xia, G.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R. Toxicity and distribution of tetrodotoxin-producing bacteria in puffer fish Fugu rubripes collected from the Bohai Sea of China. Toxicon 2005, 46, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, D.I.; Magarlamov, T.Y. An overview of the anatomical distribution of tetrodotoxin in animals. Toxins 2022, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikou, P.; Gokbulut, C.; Kosker, A.R.; Campàs, M.; Ozogul, F. An updated review of tetrodotoxin and its peculiarities. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Riveroll, L.M.; Cembella, A.D. Guanidinium toxins and their interactions with voltage-gated sodium ion channels. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Chung, S. Biochemical and biophysical research communications mechanism of tetrodotoxin block and resistance in sodium channels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. Structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels at atomic resolution. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffeney, S.L.; Fujimoto, E.; Brodie, E.D., III; Brodie, E.D., Jr.; Ruben, P.C. Evolutionary diversification of TTX-resistant sodium channels in a predator–prey interaction. Lett. Nat. 2005, 434, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, C.R.; Brodie, E.D.; Brodie, E.D.; Pfrender, M.E. Constraint shapes convergence in tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels of snakes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4556–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanifin, C.T.; Gilly, W.F. Evolutionary history of a complex adaptation: Tetrodotoxin resistance in salamanders. Evolution 2015, 69, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, G.; Hanifin, C.; Geffeney, S.; Brodie, E.D. Convergent evolution of tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels in predators and prey. Curr. Top. Membr. 2016, 78, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. Voltage-gated sodium channels at 60: Structure, function and pathophysiology. J. Physiol. 2012, 11, 2577–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlothlin, J.W.; Kobiela, M.E.; Feldman, C.R.; Castoe, T.A.; Geffeney, S.L.; Hanifin, C.T.; Toledo, G.; Vonk, F.J.; Richardson, M.K.; Brodie, J.E.D.; et al. Historical contingency in a multigene family facilitates adaptive evolution of toxin resistance. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajihara, H.; Chernyshev, A.V.; Sun, S.; Sundberg, P.; Crandall, F.B. Checklist of nemertean genera and species published between 1995 and 2007. Species Divers. 2008, 13, 245–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, M.; Norenburg, J.L.; Alfaya, J.E.J.E.; Ángel Fernández-Álvarez, F.; Andersson, H.S.; Andrade, S.C.S.; Bartolomaeus, T.; Beckers, P.; Bigatti, G.; Cherneva, I.; et al. Nemertean taxonomy—Implementing changes in the higher ranks, dismissing Anopla and Enopla. Zool. Scr. 2019, 48, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.E.; Arakawa, O.; Noguchi, T.; Miyazawa, K.; Shida, Y.; Hashimoto, K. Tetrodotoxin and related substances in a ribbon worm Cephalothrix linearis (Nemertean). Toxicon 1990, 28, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Fenwick, D.; Powell, A.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Ford, C.; Hatfield, R.G.; Santos, A.; Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Bean, T.P.; Baker-Austin, C.; et al. New invasive nemertean species (Cephalothrix simula) in England with high levels of tetrodotoxin and a microbiome linked to toxin metabolism. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, A.E.; Velansky, P.V.; Chernyshev, A.V.; Kuznetsov, V.G.; Magarlamov, T.Y. Tetrodotoxin and its analogues profile in nemertean species from the Sea of Japan. Toxicon 2018, 156, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malykin, G.V.; Velansky, P.V.; Magarlamov, T.Y. Levels and profile of tetrodotoxins in spawning Cephalothrix mokievskii (Palaeonemertea, Nemertea): Assessing the potential toxic pressure on marine ecosystems. Toxins 2025, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasenko, A.E.; Kuznetsov, V.G.; Malykin, G.V.; Pereverzeva, A.O.; Velansky, P.V.; Yakovlev, K.V.; Magarlamov, T.Y. Tetrodotoxins secretion and voltage-gated sodium channel adaptation in the ribbon worm Kulikovia alborostrata (Takakura, 1898) (Nemertea). Toxins 2021, 13, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlau, H.; Heinemann, S.H.; Stfihmer, W.; Pusch, M.; Conti, F.; Imoto, K.; Numa, S. Mapping the site of block by tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin of sodium channel HI. Fed. Eur. Biochem. Soc. 1991, 293, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricelj, V.M.; Connell, L.; Konoki, K.; MacQuarrie, S.P.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A.; Trainer, V.L. Sodium channel mutation leading to saxitoxin resistance in clams increases risk of PSP. Nature 2005, 434, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, M.C.; Hillis, D.M.; Lu, Y.; Kyle, J.W.; Fozzard, H.A.; Zakon, H.H. Toxin-resistant sodium channels: Parallel adaptive evolution across a complete gene family. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaelli, P.M.; Theis, K.R.; Williams, J.E.; O’connell, L.A.; Foster, J.A.; Eisthen, H.L. The skin microbiome facilitates adaptive tetrodotoxin production in poisonous newts. Elife 2020, 9, e53898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Matsumoto, G.; Hanyu, Y. TTX resistivity of Na+ channel in newt retinal neuron. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 240, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlothlin, J.W.; Chuckalovcak, J.P.; Janes, D.E.; Edwards, S.V.; Feldman, C.R.; Brodie, E.D., Jr.; Pfrender, M.E.; Brodie, E.D., III. Parallel evolution of tetrodotoxin resistance in three voltage-gated sodium channel genes in the garter snake Hamnophis sirtalis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffeney, S.L.; Williams, B.L.; Rosenthal, J.J.C.; Birk, M.A.; Felkins, J.; Wisell, C.M.; Curry, E.R.; Hanifin, C.T. Convergent and parallel evolution in a voltage-gated sodium channel underlies TTX-resistance in the greater blue-ringed octopus: Hapalochlaena lunulata. Toxicon 2019, 170, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, G.; Yotsu-Yamashita, M.; Shang, L.; Yasumoto, T.; Dudley, S.C. Interactions of the C-11 hydroxyl of tetrodotoxin with the sodium channel outer vestibule. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, B.; Lu, S.Q.; Dandona, N.; See, S.L.; Brenner, S.; Soong, T.W. Genetic basis of tetrodotoxin resistance in pufferfishes. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2069–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Thiel, J.; Khan, M.A.; Wouters, R.M.; Harris, R.J.; Casewell, N.R.; Fry, B.G.; Kini, R.M.; Mackessy, S.P.; Vonk, F.J.; Wüster, W.; et al. Convergent evolution of toxin resistance in animals. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1823–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, M.T.J.; Feldman, C.R.; Brodie, E.D.; Brodie, E.D. Convergent adaptation to dangerous prey proceeds through the same first-step mutation in the garter snake Thamnophis sirtalis. Evolution 2017, 71, 1504–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, E.D.; Ridenhour, B.J.; Brodie, E.D. The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: Hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts. Evolution 2002, 56, 2067–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasenko, A.E.; Magarlamov, T.Y. Tetrodotoxins in ribbon worms Cephalothrix cf. simula and Kulikovia alborostrata from Peter the Great Bay, Sea of Japan. Toxins 2023, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasenko, A.E.; Pereverzeva, A.O.; Velansky, P.V.; Magarlamov, T.Y. Tetrodotoxins in tissues and cells of different body regions of ribbon worms Kulikovia alborostrata and K. manchenkoi from Spokoynaya Bay, Sea of Japan. Toxins 2024, 16, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.; McEvoy, E.G.; Gibson, R. The production of tetrodotoxin-like substances by nemertean worms in conjunction with bacteria. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2003, 288, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, M.; Hedström, M.; Seth, H.; McEvoy, E.G.; Jacobsson, E.; Göransson, U.; Andersson, H.S.; Sundberg, P. The bacterial (Vibrio alginolyticus) production of tetrodotoxin in the ribbon worm Lineus longissimus—Just a false positive? Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffeney, S.L.; Cordingley, J.A.; Mitchell, K.; Hanifin, C.T. In silico analysis of tetrodotoxin binding in voltage-gated sodium ion channels from toxin-resistant animal lineages. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Yamamori, K.; Furukawa, K.; Kono, M. Purification and some properties of a tetrodotoxin binding protein from the blood plasma of kusafugu, Takifugu niphobles. Toxicon 2000, 38, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Shimakura, K.; Shiomi, K. A tetrodotoxin-binding protein in the hemolymph of shore crab Hemigrapsus sanguineus: Purification and properties. Toxicon 2002, 40, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.A.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lin, H.P.; Hwang, D.F. Tetrodotoxin-binding proteins isolated from five species of toxic gastropods. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, D.; Blaxter, M. The genome sequence of the bootlace worm, Lineus longissimus (Gunnerus, 1770). Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 6, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boullot, F.; Castrec, J.; Bidault, A.; Dantas, N.; Payton, L.; Perrigault, M.; Tran, D.; Amzil, Z.; Boudry, P.; Soudant, P.; et al. Molecular characterization of voltage-gated sodium channels and their relations with paralytic shellfish toxin bioaccumulation in the pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernyshev, A.V.; Polyakova, N.E. Nemerteans collected in the Bering Sea during the research cruises aboard the R/V Akademik, M.A. Lavrentyev in 2016, 2018, and 2021 with an analysis of deep-sea heteronemertean and hoplonemertean species. Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2022, 199, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbi, S.R.; Martin, A.; Romano, S.; McMillan, W.O.; Stice, L.; Grabowski, G. The Simple Dool’s Guide to PCR; University of Hawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Norén, M.; Ulf, J. Phylogeny of the Prolecithophora (Platyhelminthes) Inferred from 18S rDNA Sequences. Cladistics 1999, 15, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giribet, G.; Carranza, S.; Baguñà, J.; Riutort, M.; Ribera, C. First molecular evidence arthropoda clade for the existence of a tardigrada. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996, 13, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, M.F.; Carpenter, J.C.; Wheeler, Q.D.; Wheeler, W.C. The Strepsiptera problem: Phylogeny of the holometabolous insect orders inferred from 18S and 28S ribosomal DNA sequences and morphology. Syst. Biol. 1997, 46, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D.J.; Meier, R. SequenceMatrix: Concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Nguyen, M.A.T.; Von Haeseler, A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | 16S | 18S | COI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebratulus orochi | - | PX464474 * | PX472899 * |

| Heteronemertes longifissus | OQ449308 | OQ449295 | PX463919 * |

| Hubrechtella ijimai | KF935470 | KF935303 | KY986686 |

| Kulikovia alborostrata | LC553790 | LC553802 | PX463916 * |

| Kulikovia manchenkoi | KU821490 | - | PX463917 * |

| Kulikovia cf. montgomeryi | KU197411 | - | KU197742 |

| Lineus lacteus | KX261708 | - | KX261759 |

| Lineus longissimus | MK067321 | MK076323 | MK047697 |

| Lineus ruber | KX261701 | KY468933 | GU733828 |

| Lineus sanguineus | MK067331 | MK076333 | MK047707 |

| Micrura bella | OQ449312 | OQ449302 | OQ450494 |

| Notospermus geniculatus | LC625660 | LC625685 | LC625629 |

| Parborlasia corrugata | EU194791 | - | PX463918 * |

| Carinoma hamanako | KU197313 | - | KU197661 |

| Cephalothrix linearis | - | - | GU726652 |

| Cephalothrix simula | OQ075733 | - | PV984388 |

| Cephalothrix cf. simula | PX559980 * | PX586769 * | PX526497 * |

| Cephalothrix spiralis | KU197338 | - | GU726648 |

| Parahubrechtia rayi | - | - | PX463920 * |

| Tubulanus polymorphus | JF277598 | JF293061 | KU197697 |

| Amphiprous lactifloreus | MN211511 | MN211417 | MN205528 |

| Malacobdella grossa | MZ231135 | MZ231197 | MZ216519 |

| № | Primer Name | Primer Sequence | Reference | |

| DI | 1 | DIFUni | RTGCGCMTTYCGMCTYATGAC | Current study |

| 2 | DI_Forward | ATGCGCCTTTCGCCTTATGAC | [23] | |

| 3 | DI_Reverse | CGGCGTTCTTCCTCTTCCTTT | [23] | |

| 4 | RID_improved | CATTCTGATGGACTTTTTGGCA | Current study | |

| 5 | DIFw_csim | GTTTTTCAGTCAATGTTTGG | Current study | |

| 6 | DIRev_csim | CGACACTTACTAACTGATAC | Current study | |

| 7 | DIRUni | CGGCGYTCYTCYTCTTCCTTT | Current study | |

| DII | 8 | DIIForward | GTCCTYCGAACATTCAGATTGC | [23] |

| 9 | DII reverse | AGATTGGAGATTTTCAGCCCC | [23] | |

| 10 | DII reverse v2 | ATGCTTTCAATCCATTCCCCA | Current study | |

| 11 | DIIFw_csim | TTCATATTTGCTGTCGTCGGT | Current study | |

| 12 | DIIRev_csim | CTAACACCAAGTCCCCTCAAC | Current study | |

| DIII | 13 | DIII forward | GTCTTCTGGCTCATCTTCAGTATCA | [23] |

| 14 | DIII reverse | TCAGCGTGAAGAAAGAACCGA | [23] | |

| 15 | DIIIFw_paleo | CTGGCTKATCTTTAGYATMATGGG | Current study | |

| 16 | DIIIRev_paleo | TACCCCTCTCATRTCSGTYG | Current study | |

| DIV | 17 | DIV Forward | AACATGCTGCCGGGATAGA | [23] |

| 18 | DIV Forward new | CGCTAGCGGTTTCACTTCCT | Current study | |

| 19 | DIV reverse | TTGCCGCAGTTACCCTTGAC | [23] | |

| 20 | DIV_F_paleo | TCCCTGCCTGCCYTMTTC | Current study | |

| 21 | DIV_R_paleo | GTACTGCGTGGCTTCAGGATC | Current study |

| DI—Primer Combinations | DII—Primer Combinations | DIII—Primer Combinations | DIV—Primer Combinations | |

| Cerebratulus orochi | DIFUni + RID_improved (Ta 57 °C) len 281bp | DIIForward + DII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 431bp | DIII forward + DIII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 348bp | N/A |

| Heteronemertes longifissus | DI_Forward + DI_Reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 233bp | DIIForward + DII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 431bp | DIII forward + DIII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 348bp | N/A |

| Kulikovia manchenkoi | DI_Forward + DI_Reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 233bp | DIIForward + DII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 431bp | DIII forward + DIII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 348bp | DIV Forward + DIV reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 193bp |

| Kulikovia cf. montgomeryi | DI_Forward+ DI_Reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 233bp | DIIForward + DII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 431bp p | DIII forward + DIII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 348bp | DIV Forward + DIV reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 193bp |

| Micrura bella | DI_Forward+ DI_Reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 233bp | N/A | DIII forward + DIII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 348bp | DIV Forward new + DIV reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 294bp |

| Parborlasia corrugata | DIFUni +DIRUni (Ta 56 °C) len 233bp | DIIForward + DII reverse v2 (Ta 56 °C) len 295bp | N/A | N/A |

| Parahubrechtia rayi | DIFUni+ DI_Reverse (Ta 52 °C) len 233bp | DIIForward + DII reverse v2 (Ta 56 °C) len 295bp | DIII forward + DIII reverse (Ta 57 °C) len 348bp | DIV Forward + DIV reverse (Ta 56 °C) len 193bp |

| Cephalothrix cf. simula | DIFw_csim + DIRev_csim (Ta 47 °C) len 163bp | DIIFw_csim + DIIRev_csim (Ta 52 °C) len 334bp | DIIIFw_paleo + DIIIRev_paleo (Ta 57 °C) len 270 bp | DIV_F_paleo DIV_R_paleo (Ta 53 °C) len 464bp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuznetsov, V.G.; Vlasenko, A.E.; Magarlamov, T.Y. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Substitutions Underlying Tetrodotoxin Resistance in Nemerteans: Ecological and Evolutionary Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411785

Kuznetsov VG, Vlasenko AE, Magarlamov TY. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Substitutions Underlying Tetrodotoxin Resistance in Nemerteans: Ecological and Evolutionary Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411785

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuznetsov, Vasiliy G., Anna E. Vlasenko, and Timur Yu. Magarlamov. 2025. "Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Substitutions Underlying Tetrodotoxin Resistance in Nemerteans: Ecological and Evolutionary Implications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411785

APA StyleKuznetsov, V. G., Vlasenko, A. E., & Magarlamov, T. Y. (2025). Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Substitutions Underlying Tetrodotoxin Resistance in Nemerteans: Ecological and Evolutionary Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411785