Abstract

VPS13A disease is a rare, autosomal-recessive, neurodegenerative disorder characterized by involuntary movements, orofacial dystonia, seizures, psychiatric symptoms, and the presence of spiky, deformed red blood cells (acanthocytes). The disease is caused by mutations in the VPS13A gene, which encodes the VPS13A protein (previously known as chorein). This protein is a member of the family of bridge-like lipid transport proteins, involved in bulk lipid transfer between membranes and intracellular vesicle trafficking. We describe the case of a 37-year-old woman with gait instability, semi-flexed legs, and involuntary distal muscle movements. Genetic testing was performed using next-generation sequencing (NGS), followed by molecular analysis. Fibroblasts from the patient, her mother, and a healthy control were analyzed by immunofluorescence and Western blotting. NGS identified a novel homozygous 2.8 kb deletion encompassing exons 69–70 (69–70del) of the VPS13A gene (NM_033305.3). The same variant was detected in the patient’s mother in a heterozygous state and her brother in a homozygous state. Although other deletions in the gene have been described, a comprehensive search of population variant databases and the existing literature did not reveal previous reports of this deletion. Fibroblasts from the patient, her mother and a healthy control were characterized. Functional assays showed a complete absence of the VPS13A protein in the patient’s fibroblasts. This study expands the mutational spectrum of VPS13A-linked VPS13A disease and underlines the importance of comprehensive genetic analysis in atypical cases.

1. Introduction

VPS13A (Vacuolar protein sorting 13 homolog A) disease (previously known as Chorea-acanthocytosis, ChAc; OMIM #200150) [1], is the most common subtype of neuroacanthocytosis syndrome, characterized by the presence of abnormal star-shaped red blood cells (acanthocytes) and neurological disturbances [2]. First identified in Japan, where subsequent cases have also been described, VPS13A disease is now recognized worldwide [3,4], although it has an extremely low overall prevalence of fewer than 1000 reported cases (https://www.orpha.net/it/disease/detail/263440 accessed on 15 July 2025). Clinically, VPS13A is characterized by involuntary movements and dystonia of the limbs and oro-facial muscles as well as the presence of acanthocytes (acanthocytosis) [5]. Hearing may also be impaired, as contractions of the tongue and throat can interfere with chewing and swallowing food [6]. There have also been cases where cognitive and psychiatric disorders have preceded the first neurological manifestations. Finally, seizures are the first manifestation of the disease in at least one-third of patients [7]. The age of onset is usually between 20 and 50 years, with a mean of around 30–35 years, and an average diagnostic delay of ~6 years [8]. Despite growing awareness, the causative mechanism of the pathology is still unknown, and VPS13A disease remains underdiagnosed due to its phenotypic overlap with other neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [5]. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis cannot be made based on instrumental tests and the morphological study of acanthocytes alone. In this context, genetics plays a crucial role in identifying the molecular cause of the disease. VPS13A disease is caused by biallelic mutations (autosomal recessive transmission) in the VPS13A gene, located on chromosome 9 (9q21) and spanning 250 kb [9]. This gene (NM_033305.3) comprises 72 exons and encodes a 3174-amino acid protein VPS13A (360 kDa). This protein belongs to the recently characterized family of bridge-like lipid transfer proteins (BLTPs), which mediate non-vesicular bulk lipid transport between closely apposed membranes at organelle contact sites [9,10,11]. The VPS13A protein has a complex domain structure that includes an N-terminal domain, which contains an FFAT (two phenylalanines in an acidic tract) motif for binding to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-associated protein (VAP). It also has a VAB (VPS13 Adaptor Binding) domain and a CHOREIN domain, which likely function in lipid transfer, an APT1 domain (aberrant pollen transcription 1), a C-terminal ATG2 domain (ATG_C), and a PH-like domain (Pleckstrin homology-like domain) located more towards the C-terminal. These domains allow VPS13A to associate with various organelles, including the ER, mitochondria, endosomes, and lipid droplets, facilitating lipid transfer and membrane contact sites (MCSs) [12,13,14].

Recent studies have further explored the pathophysiological mechanisms and potential biomarkers of VPS13A disease, providing insights into how mutations in this large lipid transport protein lead to neurodegeneration [9]. Several mutations in the VPS13A gene have been identified to date, including gross deletions (n = 8), nonsense and missense mutations (n = 64), and splicing mutations (n = 34), as reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD; https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php accessed on 2 October 2025).

Supplementary Table S1 provides a comprehensive list of the 92 VPS13A variants that have been identified as either pathogenic or likely pathogenic, and which are associated with VPS13A disease in populations worldwide [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The majority of these (65%) are nonsense or frameshift mutations predicted to lead to a truncated protein. Splice-site variants represent 20% of the total, while large deletions/duplications and missense substitutions account for around 8% and 5%, respectively. These variants are distributed throughout the VPS13A coding sequence, with no single major mutational hotspot [26]. In this report, we describe the first detailed characterization of the functional properties of the occurring deletions of exons 69 and 70 in VPS13A (VPS13A 69-70del; NM_033305.3; chr9:77403236-77405987; c.9190_9419del; p.V3064_K3133del) in a VPS13A disease patient, expanding the known mutational spectrum and emphasizing the importance of combining genetic, cellular, and clinical data for accurate diagnosis.

2. Case Description

The mother of the proband reported she had a complex congenital heart disease at an early age, including Botallo ductus patency, for which she underwent unspecified surgery. At 20, she started complaining of early fatigue, which gradually worsened in the following years. At 30, she began experiencing involuntary limb movements, initially affecting only her legs and then gradually spreading to her arms. She then performed a diagnostic pathway, which revealed creatine phosphokinase above the normal range (>2000 UI) and electromyographic signs of polyneuropathy. A biopsy of the left bicipital muscle showed no abnormalities. At 34, family members started observing behavioral changes, with irritability, inflexibility, and obsessive thoughts. She started off-label treatment with tetrabenazine 100 mg/day per os.

The whole clinical condition gradually worsened in the following years, with increasing choreic movements and psychiatric disturbances, which affected the quality of night rest and autonomy as a whole. The patient is now 37 years old and, as a consequence of the gradual clinical worsening, has unstable walking and needs help in most daily activities.

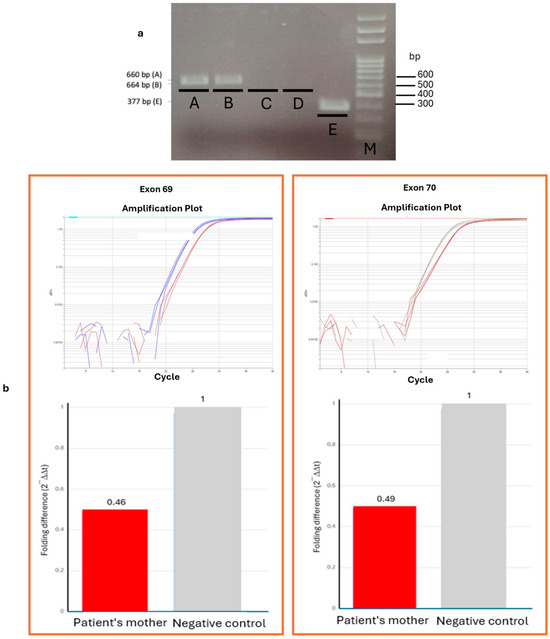

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis was performed using a targeted gene panel comprising the coding regions of 4 genes (Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein (MTTP), Pantothenate Kinase 2 (PANK2), VPS13A and X-Linked Kx Blood Group Antigen, Kell And VPS13A Binding Protein (XK)). Interestingly, a homozygous deletion (69-70del) of 2.,8 Kb in VPS13A (NM_033305.3; chr9:77403236-77405987; c.9190_9419del, p.V3064_K3133del) was revealed. This results in the loss of exons 69 and 70 in frame, corresponding to the removal of 70 amino acids. This VPS13A mutation has not been reported before and, according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines [37] for copy number variants (CNVs), it is classified as likely pathogenic, fulfilling criteria 1A (contains protein-coding exons), 2A (involves a known loss-of-function (LoF)-sensitive gene) and 2E (both breakpoints are within the same gene, confirming a gene-level LoF event). The deletion was confirmed in the proband by PCR and gel electrophoresis analysis (Figure 1a). Semi-quantitative analysis performed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) revealed the presence of the same deletion in a heterozygous state in the proband’s mother (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Gel electrophoresis for exons 69-70 of the VPS13A gene in the proband and qPCR analysis in the proband’s mother. (a) Gel electrophoresis of PCR products for VPS13A exons 69-70. Lane A: Negative control for VPS13A-exon 69 (652 bp); Lane B: Negative control for VPS13A-exon 70 (664 bp); Lane C: PCR product from the proband (P) for VPS13A-exon 69; Lane D: PCR product from the proband (P) for VPS13A-exon 70; Lane E: Amplification control (337 bp). M: 100 bp DNA ladder. (b) Real-time qPCR analysis of VPS13A exons 69 (left) and 70 (right). The red curve corresponds to the mother’s sample, while the blue and grey curves represent the negative controls for exons 69 and 70, respectively. The bottom panels show the corresponding relative quantification histograms (ΔΔCq).

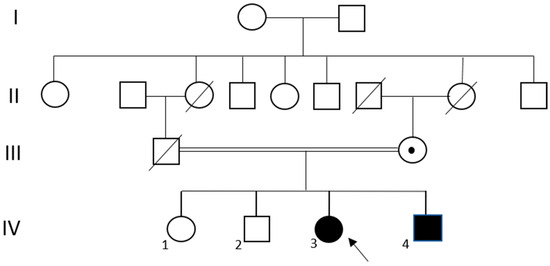

The same 69-70del of the VPS13A gene was also detected in the proband’s brother, who developed clinical signs associated with VPS13A disease. It is also worth noting that the patient’s parents are first cousins, contributing to the homozygous inheritance of the variant. The family pedigree is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pedigree of the VPS13A disease-affected proband. The proband (IV-3) is indicated by an arrow. The double line between the parents indicates consanguinity. A dot symbol (•) denotes carrier status for the VPS13A-related mutation. Black symbols represent affected individuals. Roman numerals indicate generations and Arabic numbers (1,2,4) indicate individuals.

To investigate the functional effects of this novel VPS13A variant, a skin biopsy was performed on the patient, as previously described [38]. Specifically, a skin biopsy, immediately preserved in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), was cultured in a complete medium consisting of DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) supplemented with 10% calf serum (CS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin. The plate was then placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The medium was changed every three to four days until the released fibroblasts reached 80% confluence (approximately 20 days). All experiments were performed using cells from the third or fourth passage.

The immunofluorescence (IF) assay on fibroblasts was performed according to protocols that had been published already [39] to assess the subcellular localization of VPS13A, which is mostly perinuclear, as shown in Figure 3. Briefly, fibroblasts were cultured on glass coverslips in a 4-well plate at a concentration of 10,000 cells/mL with two replicates for each subject. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, then permeabilized with 0.5% PBS-Triton X-100 for 10 min. They were then incubated with a polyclonal VPS13A antibody diluted 1:500 (Proteintech Group Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; catalog number 28618-1-AP).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of VPS13A protein localisation in fibroblasts. Fibroblasts from a healthy control, a heterozygous carrier (mother), and the homozygous patient (69-70del). Cells were immunostained with a polyclonal anti-VPS13A antibody (red) (Proteintech; 1:500 dilution). DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. In all three cell lines, VPS13A shows a perinuclear localization pattern.

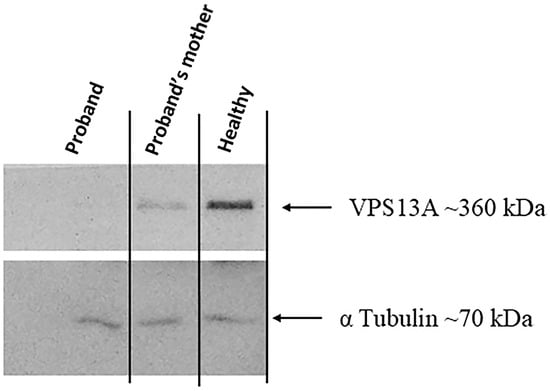

In addition, to evaluate the level of the VPS13A protein, a Western blot (WB) assay was performed in whole lysate extract. The blots were incubated with a dilution of 1:800 of the polyclonal VPS13A antibody (Proteintech Group Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; catalog number 28618-1-AP) and a dilution of 1:1250 of the monoclonal alpha Tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich—St. Louis, MO, USA; catalog number T6199). Protein bands were visualized using ECL Star (Euroclone—Pero, MI, Italy), and chemiluminescence detection was performed using a ChemiDoc-It Imaging System (UVP, Cambridge, UK).

The patient with VPS13A disease lacks the band that marks VPS13A, indicating a loss of protein likely due to the deletion. This is in contrast to her mother and a healthy control, where the band is clearly visible (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of VPS13A protein in fibroblasts. WB was performed using an anti-VPS13A antibody recognizing an epitope between amino acids 2452–2595 (dilution 1:800). The predicted molecular weights are approximately 360 kDa for the full-length wild-type (WT) protein and 352 kDa for the putative truncated protein (p.V3064_K3133del) resulting from 69 to 70del. WB detects the expression of the VPS13A protein in a patient with 69-70del in the homozygous state, her mother, who is a carrier of the same mutation in the heterozygous state, and a healthy control. Alpha tubulin (monoclonal antibody; dilution 1:1250—Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a loading control to normalize the levels of protein detected. Biological replicates: n = 3 independent experiments. Protein marker: Sharpmass VI (Euroclone). The reference molecular weights used were 150 kDa and 250 kDa.

Despite positive immunofluorescence staining in the patient’s fibroblasts, VPS13A was not detectable by WB analysis. This finding is explained by the use of the same C-terminal antibody, which recognizes the epitope aa 2452–2595 and can detect trace amounts of an abnormal VPS13A protein present at levels too low for WB detection.

Extended functional assays in fibroblasts were not performed, as it was beyond the scope of this study.

3. Discussion

This study reports the case of a 37-year-old female patient whose clinical phenotype—characterized by involuntary limb movements, psychiatric symptoms, polyneuropathy signs on electromyography (EMG), and elevated creatine phosphokinase (CK)—is consistent with previously reported manifestations of VPS13A disease. Genetic testing using targeted NGS revealed a previously unreported 2.8 Kb deletion (chr9:77403236-77405987; c.9190_9419del, p.V3064_K3133del) in the VPS13A gene, encompassing exons 69 and 70.

To date, approximately 90 pathogenic variants in the VPS13A gene have been linked to the VPS13A disease phenotype (see Supplementary Table S1). Among these, eight have been reported in Italian patients, including nonsense mutations, frameshift deletions/insertions, and intronic variants [20,22,27].

Overall, eight multiexon deletions (in-frame and frameshift) in the VPS13A gene are reported in the HGMD database. However, only five of these have been definitively classified as pathogenic (see Supplementary Table S1), and most of these have only been described at the genomic level. In particular, the deletion of exons 60–61 appears common in the Japanese population [3,16], and the deletion of exons 70–72 has been observed in the French–Canadian population [4]; therefore, the proportion of pathogenic variants detected varies by population. The majority of disease-associated variants of VPS13A are predicted to be loss-of-function.

Multiple lines of evidence support the pathogenicity of the exons 69 and 70 in-frame deletion reported in this study: (i) the deleted region encodes a critical portion of the C-terminal domain of VPS13A, including the PH-like domain encoded by the final exons of VPS13A. This region is essential for lipid transport and membrane tethering at organelle contact sites (e.g., ER–mitochondria sites). The C-terminal of VPS13A harbors conserved lipid-binding domains (similar to ATG2, the autophagy protein) and interaction motifs for partners like XK [40]. Notably, many patient mutations have been reported in this domain, which is encoded by the last three exons of the VPS13A gene [41] (Supplementary Table S1); (ii) the family pedigree revealed consanguinity between the proband’s parents, and segregation analysis confirmed the presence of a homozygous deletion in two affected family members (IV-3 and IV-4); (iii) functional analysis showed a complete absence of full-length VPS13A in the patient compared to the control and the proband’s mother, as demonstrated by WB. However, the residual signal detected by IF is consistent with the presence of trace amounts of an abnormal VPS13A protein, which is likely degraded and/or non-functional. It is important to note that the antibody used for both WB and IF recognizes an epitope (aa 2452–2595) upstream of the region involved in the deletion (aa 3064–3133). Thus, the positive IF signal most likely represents an unstable, incomplete protein that persists at very low levels, below the WB detection threshold. Although the resulting protein may remain “intact” in terms of structure, the loss of these exons would eliminate a region essential for its function, rendering it non-functional.

Rarely, individuals with VPS13A disease may express VPS13A that lacks the PH domain, involved in lipid transfer and MCS [41]. In addition, some pathogenic missense substitutions that do not result in misfolding and protein degradation or small deletions leading to expression of a truncated protein are known to be associated with normal levels of VPS13A [41]. Together, our findings support a loss-of-function mechanism, in line with previous studies [15,26,40].

Additionally, the GnomAD browser shows a low rate of missense variants in the exons of VPS13A and classifies this as a gene with a pLI score of 0.7 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/gene/ENSG00000197969?dataset=gnomad_r4, accessed on 7 July 2025), which indicates that it is likely to be intolerant to loss-of-function variants. This is in line with the severe neurological consequences observed in patients with VPS13A disease resulting from VPS13A mutations [29].

A clinical comparison with previously described Italian patients, as shown in Supplementary Table S1, reveals an overlap of features, particularly concerning movement disorders, psychiatric symptoms and elevated CK levels. However, the presence of polyneuropathy signs and evidence of cardiac involvement in our patient appear to be less frequently reported findings in Italian patients [20,27].

Taken together, these data further support that the mutation causes VPS13A deficiency and disrupts intracellular lipid trafficking, resulting in the neurodegenerative features of VPS13A disease. Our results also underline the importance of combining genetic diagnosis and molecular characterization to correctly classify variants, in line with the ACMG guidelines [37].

4. Conclusions

The identification of a novel homozygous VPS13A 69-70del highlights the diagnostic importance of NGS in revealing pathogenic variants that elude conventional sequencing approaches. This finding broadens the mutational spectrum of VPS13A disease and improves our understanding of its molecular pathology. An early and accurate genetic diagnosis of VPS13A disease is crucial, as it facilitates appropriate patient management and genetic counseling and lays the groundwork for future therapeutic approaches in VPS13A disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262311521/s1.

Author Contributions

B.P. participated in the organization of the research project and drafted the first draft of the manuscript. V.M. and M.P. collaborated in the experimental execution of the project. P.R. contributed to the critical review of the results. E.D.G., A.L. and M.M. participated in the experimental phase. V.L.B. contributed to the conception and design of the study. R.S. and F.L.C. played a key role in conceiving the research project, planning the activities, and reviewing the work. They also participated in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) through PRIN 2022, project no. 2022XTM2S3, CUP H53D23005530006, and by PRIN PNRR 2022—European Union’s NextGenerationEU initiative, project no. P20225J5NB, CUP H53D23008990001, awarded to Francesca Luisa Conforti.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The current study was performed in collaboration between the University of Calabria and the ALS clinical Research Center of Palermo. The experiments were carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Paolo Giaccone (Protocol No. 04/2019, date 29 April 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects and patients involved in this study underwent thorough psychological and genetic counseling and signed informed consent for the genetic testing and skin biopsy for research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

Elda Del Giudice, Alberta Leon, Martina Maino were employed by the Research & Innovation (R&I Genetics) SRL. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| APT1 | Aberrant pollen transcription 1 |

| ATG_C | C-terminal ATG2 domain |

| BLTPs | Bridge-like lipid transfer proteins |

| ChAc | Chorea-acanthocytosis |

| CK | Creatine phosphokinase |

| CNV | Copy number variant |

| CS | Calf serum |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| FFAT | Two phenylalanines in an acidic tract |

| HGMD | Human Gene Mutation Database |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| MCS | Membrane contact sites |

| MTTP | Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein |

| PANK2 | Pantothenate kinase 2 |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PH-like domain | Pleckstrin homology-like domain |

| VAB | VPS13 adaptor binding |

| VAMP | Vesicle-associated membrane protein |

| VAP | VAMP-associated protein |

| VPS13A | Vacuolar protein sorting 13 homolog A |

| WB | Western blot |

| XK | X-linked Kx blood group antigen, Kell and VPS13A binding protein |

References

- Peikert, K.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Rampoldi, L.; Miltenberger-Miltenyi, G.; Neiman, A.; De Camilli, P.; Hermann, A.; Walker, R.H.; Monaco, A.P.; Danek, A. VPS13A Disease. In GeneReviews(®); Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wan, X.H.; Guo, Y. Progress in the Diagnosis and Management of Chorea-acanthocytosis. Chin. Med. Sci. J. Chung-Kuo I Hsueh K’o Hsueh Tsa Chih 2018, 33, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, S.; Maruki, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Tomemori, Y.; Kamae, K.; Tanabe, H.; Yamashita, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Kaneko, S.; Sano, A. The gene encoding a newly discovered protein, chorein, is mutated in chorea-acanthocytosis. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson-Stone, C.; Danek, A.; Rampoldi, L.; Hardie, R.J.; Chalmers, R.M.; Wood, N.W.; Bohlega, S.; Dotti, M.T.; Federico, A.; Shizuka, M.; et al. Mutational spectrum of the CHAC gene in patients with chorea-acanthocytosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 10, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikert, K.; Danek, A.; Hermann, A. Current state of knowledge in Chorea-Acanthocytosis as core Neuroacanthocytosis syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 61, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, J.G.; Rivera, C.; Utsman, R.; Klasser, G.D. Orofacial manifestations of chorea-acanthocytosis: Case presentation and literature review. Quintessence Int. 2022, 53, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.H.; Danek, A.; Walker, R.H. Neuroacanthocytosis syndromes. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Tao, M.; Lv, Y.; Xu, L.; Liang, Z. Two case reports of chorea-acanthocytosis and review of literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Meng, H.; Shafeng, N.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Hou, S. Exploring the pathophysiological mechanisms and wet biomarkers of VPS13A disease. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1482936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, M.; Guillén-Samander, A.; De Camilli, P. RBG Motif Bridge-Like Lipid Transport Proteins: Structure, Functions, and Open Questions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 39, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, L.E. VPS13 and bridge-like lipid transporters, mechanisms, and mysteries. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1534061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Leonzino, M.; Hancock-Cerutti, W.; Horenkamp, F.A.; Li, P.; Lees, J.A.; Wheeler, H.; Reinisch, K.M.; De Camilli, P. VPS13A and VPS13C are lipid transport proteins differentially localized at ER contact sites. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 3625–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, S.D.; Thakur, R.S.; Gratz, S.J.; O’Connor-Giles, K.M.; Bashirullah, A. Neurodegenerative and Neurodevelopmental Roles for Bulk Lipid Transporters VPS13A and BLTP2. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2025, 40, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminska, J.; Soczewka, P.; Rzepnikowska, W.; Zoladek, T. Yeast as a Model to Find New Drugs and Drug Targets for VPS13-Dependent Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.H.; Xiao, B.; Chen, R.K.; Chen, J.Y.; Cai, N.Q.; Cao, C.Y.; Zhan, L.Q. Novel loss-of-function mutations in VPS13A cause chorea-acanthocytosis in two families. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1643889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodsinezhad, V.; Ghoreishi, A.; Rohani, M.; Dadfar, M.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Rostami, A.; Rahimi, H. Identification of four novel mutations in VSP13A in Iranian patients with Chorea-acanthocytosis (ChAc). Mol. Genet. Genomics 2024, 299, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Chae, H.Y.; Park, H.S. Compound Heterozygous VPS13A Variants in a Patient with Neuroacanthocytosis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Lab. Med. 2022, 53, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Urata, Y.; Kasamo, K.; Hiwatashi, H.; Yokoyama, I.; Mizobuchi, M.; Sakurai, K.; Osaki, Y.; Morita, Y.; et al. Novel pathogenic VPS13A gene mutations in Japanese patients with chorea-acanthocytosis. Neurol. Genet. 2019, 5, e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Ki, C.S.; Cho, A.R.; Lee, J.I.; Ahn, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, J.W. Globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation improves chorea and functional status in a patient with chorea-acanthocytosis. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 2012, 90, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyasu, A.; Nakamura, M.; Ichiba, M.; Ueno, S.; Saiki, S.; Morimoto, M.; Kobal, J.; Kageyama, Y.; Inui, T.; Wakabayashi, K.; et al. Novel pathogenic mutations and copy number variations in the VPS13A gene in patients with chorea-acanthocytosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet. 2011, 156b, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Noyce, A.; Velayos-Baeza, A.; Lees, A.J.; Warner, T.T.; Ling, H. Late Emergence of Parkinsonian Phenotype and Abnormal Dopamine Transporter Scan in Chorea-Acanthocytosis. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2015, 2, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampoldi, L.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Rubio, J.P.; Danek, A.; Chalmers, R.M.; Wood, N.W.; Verellen, C.; Ferrer, X.; Malandrini, A.; Fabrizi, G.M.; et al. A conserved sorting-associated protein is mutant in chorea-acanthocytosis. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchberger, A.; Riedel, E.; Hackenberg, M.; Mensch, A.; Beck-Woedl, S.; Park, J.; Haack, T.B.; Haslinger, B.; Kirschke, J.; Prokisch, H.; et al. The Diverse Neuromuscular Spectrum of VPS13A Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchkat, F.; Regragui, W.; Smaili, I.; Naciri Darai, H.; Bouslam, N.; Rahmani, M.; Melhaoui, A.; Arkha, Y.; El Fahime, E.; Bouhouche, A. Novel pathogenic VPS13A mutation in Moroccan family with Choreoacanthocytosis: A case report. BMC Med. Genet. 2020, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B.S.; Hazrati, L.N.; Lang, A.E. Neuropathological findings in chorea-acanthocytosis: New insights into mechanisms underlying parkinsonism and seizures. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 127, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, S.; Ware, A.P.; Jasti, D.B.; Gorthi, S.P.; Acharya, L.P.; Bhat, M.; Mallya, S.; Satyamoorthy, K. Exome sequencing of choreoacanthocytosis reveals novel mutations in VPS13A and co-mutation in modifier gene(s). Mol. Genet. Genomics 2023, 298, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisfeld, A.; Bruno, G.; Petracca, M.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Servidei, S.; Vita, M.G.; Bove, F.; Straccia, G.; Dato, C.; Di Iorio, G.; et al. Neuroacanthocytosis Syndromes in an Italian Cohort: Clinical Spectrum, High Genetic Variability and Muscle Involvement. Genes 2021, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benninger, F.; Afawi, Z.; Korczyn, A.D.; Oliver, K.L.; Pendziwiat, M.; Nakamura, M.; Sano, A.; Helbig, I.; Berkovic, S.F.; Blatt, I. Seizures as presenting and prominent symptom in chorea-acanthocytosis with c.2343del VPS13A gene mutation. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Novel heterozygous VPS13A pathogenic variants in chorea-neuroacanthocytosis: A case report. BMC Neurol. 2023, 23, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, Y.; Nishie, M.; Ichiba, M.; Nakamura, M.; Mori, F.; Ogawa, M.; Kaimori, M.; Sano, A.; Wakabayashi, K. Chorea-acanthocytosis with upper motor neuron degeneration and 3419_3420 delCA and 3970_3973 delAGTC VPS13A mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sandoval, J.L.; García-Navarro, V.; Chiquete, E.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Monaco, A.P.; Alvarez-Palazuelos, L.E.; Padilla-Martínez, J.J.; Barrera-Chairez, E.; Rodríguez-Figueroa, E.I.; Pérez-García, G. Choreoacanthocytosis in a Mexican family. Arch. Neurol. 2007, 64, 1661–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hadzsiev, K.; Szőts, M.; Fekete, A.; Balikó, L.; Boycott, K.; Nagy, F.; Melegh, B. Neuroacanthocytosis diagnosis with new generation whole exome sequencing. Orvosi Hetil. 2017, 158, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson-Stone, C.; Velayos-Baeza, A.; Jansen, A.; Andermann, F.; Dubeau, F.; Robert, F.; Summers, A.; Lang, A.E.; Chouinard, S.; Danek, A.; et al. Identification of a VPS13A founder mutation in French Canadian families with chorea-acanthocytosis. Neurogenetics 2005, 6, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, I.; Saigoh, K.; Hirano, M.; Mtsui, Y.; Sugioka, K.; Takahashi, J.; Shimomura, Y.; Tani, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Kusunoki, S. Ophthalmologic involvement in Japanese siblings with chorea-acanthocytosis caused by a novel chorein mutation. Park. Relat. Disord. 2013, 19, 913–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Ichikawa, K.; Ueno, S.; Ichiba, M.; Nakamura, M.; Sano, A. A new phenotype of chorea-acanthocytosis with dilated cardiomyopathy and myopathy. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2007, 22, 1669–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merwick, Á.; Mok, T.; McNamara, B.; Parfrey, N.A.; Moore, H.; Sweeney, B.J.; Hand, C.K.; Ryan, A.M. Phenotypic Variation in a Caucasian Kindred with Chorea-Acanthocytosis. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2015, 2, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Bello, M.; Di Fini, F.; Notaro, A.; Spataro, R.; Conforti, F.L.; La Bella, V. ALS-Related Mutant FUS Protein Is Mislocalized to Cytoplasm and Is Recruited into Stress Granules of Fibroblasts from Asymptomatic FUS P525L Mutation Carriers. Neurodegener. Dis. 2017, 17, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Bella, V.; Cisterni, C.; Salaün, D.; Pettmann, B. Survival motor neuron (SMN) protein in rat is expressed as different molecular forms and is developmentally regulated. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998, 10, 2913–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Hu, Y.; Hollingsworth, N.M.; Miltenberger-Miltenyi, G.; Neiman, A.M. Interaction between VPS13A and the XK scramblase is important for VPS13A function in humans. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs260227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Samander, A.; Wu, Y.; Pineda, S.S.; García, F.J.; Eisen, J.N.; Leonzino, M.; Ugur, B.; Kellis, M.; Heiman, M.; De Camilli, P. A partnership between the lipid scramblase XK and the lipid transfer protein VPS13A at the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205425119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).