Structural and Optical Properties of New 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-4-methylopyridine and 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-6-methylpyridine Isomers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD Studies of the Studied Isomers

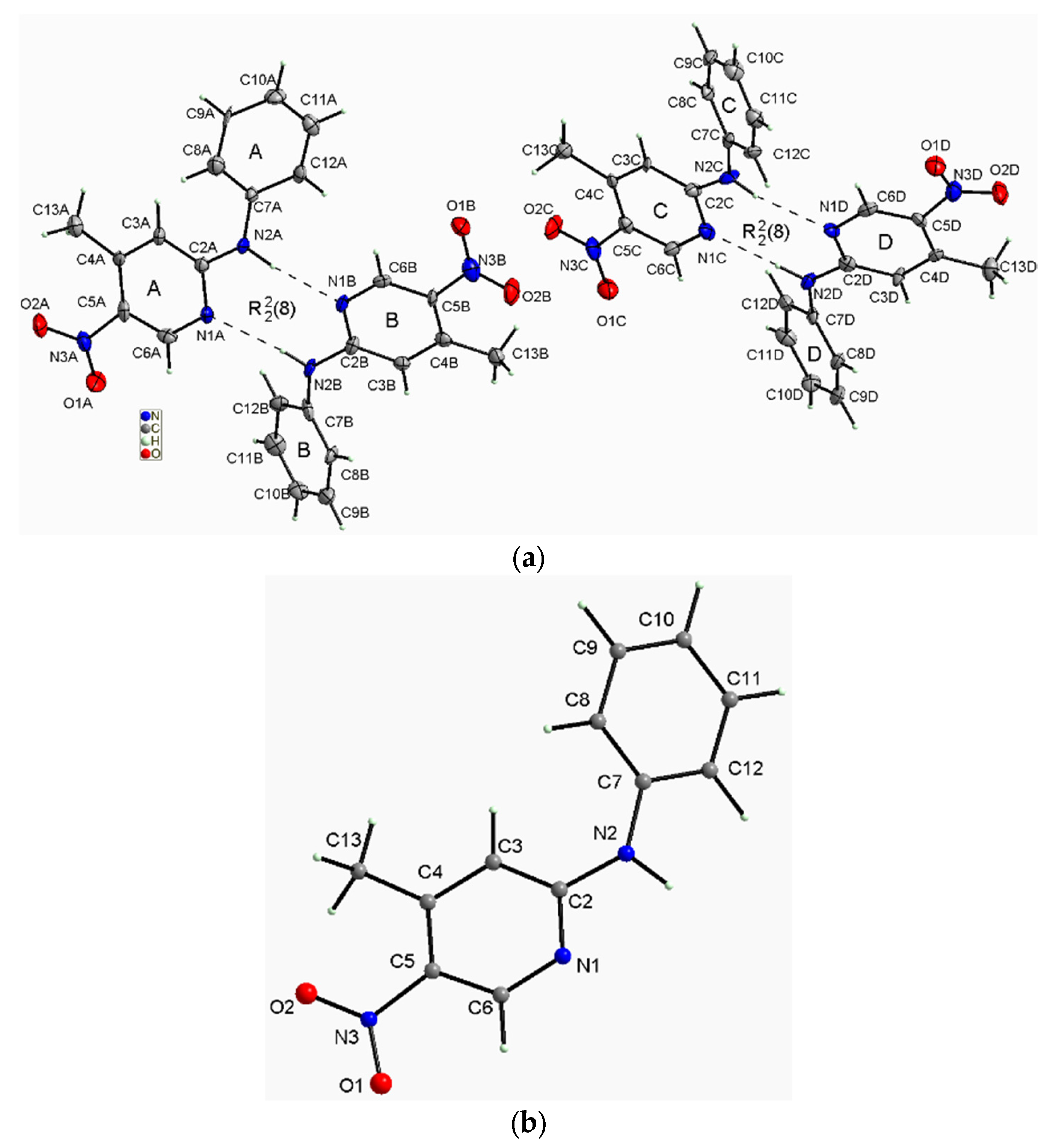

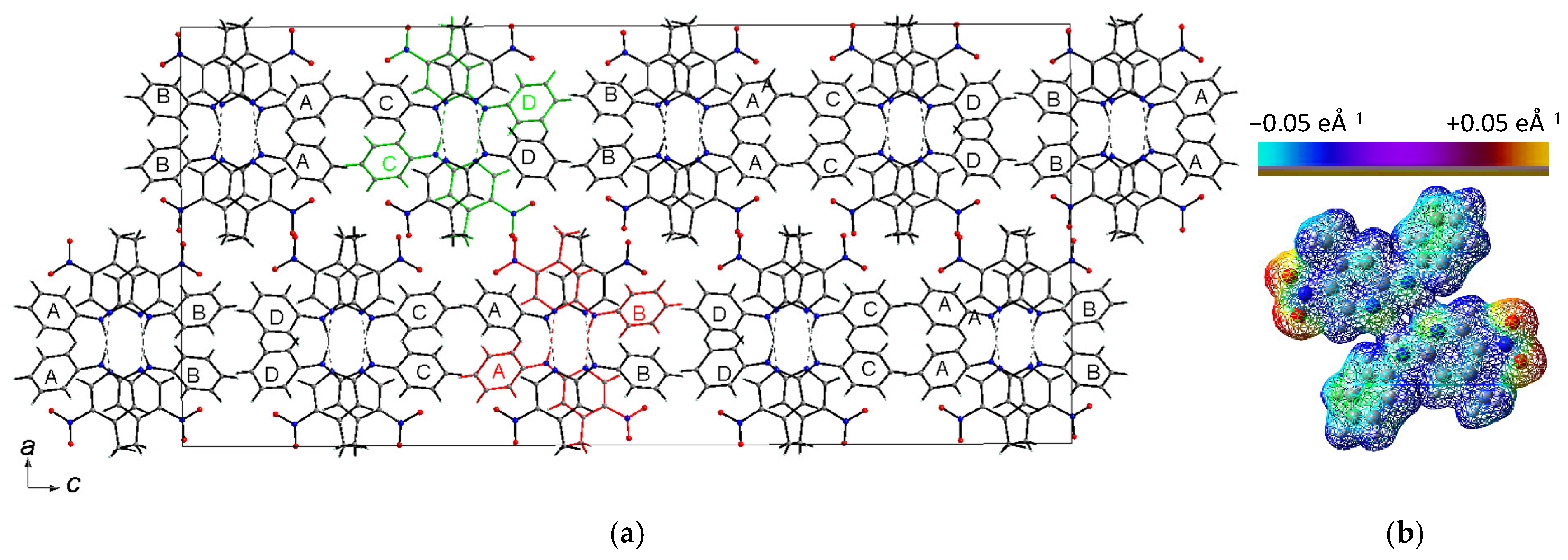

2.1.1. Description of the Structure of 2-N-Phenylamino-5-nitro-4-methylpyridine (2PA5N4MP)

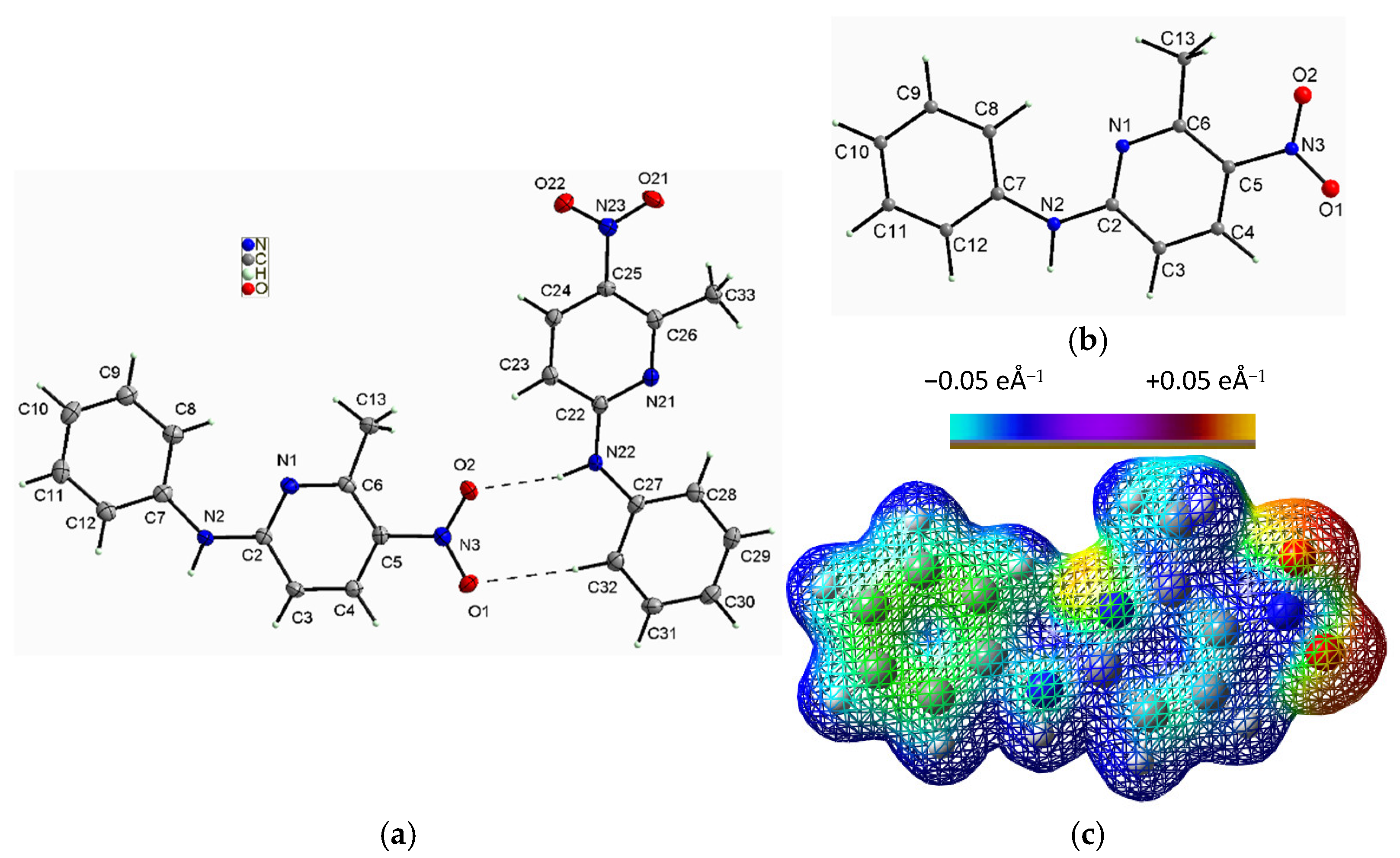

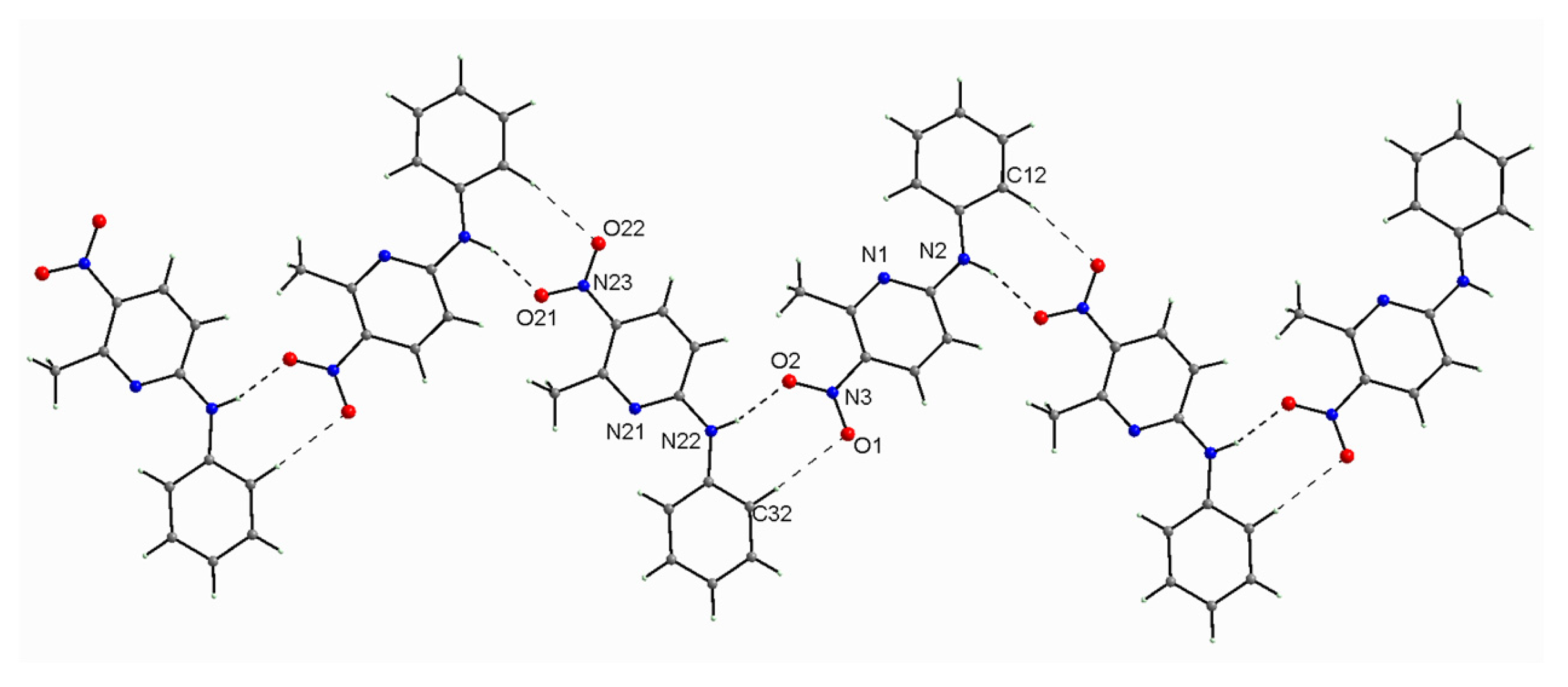

2.1.2. Description of the Structure of 2-N-Phenylamino-5-nitro-6-methylpyridine (2PA5N6MP)

2.2. IR and Raman Spectra

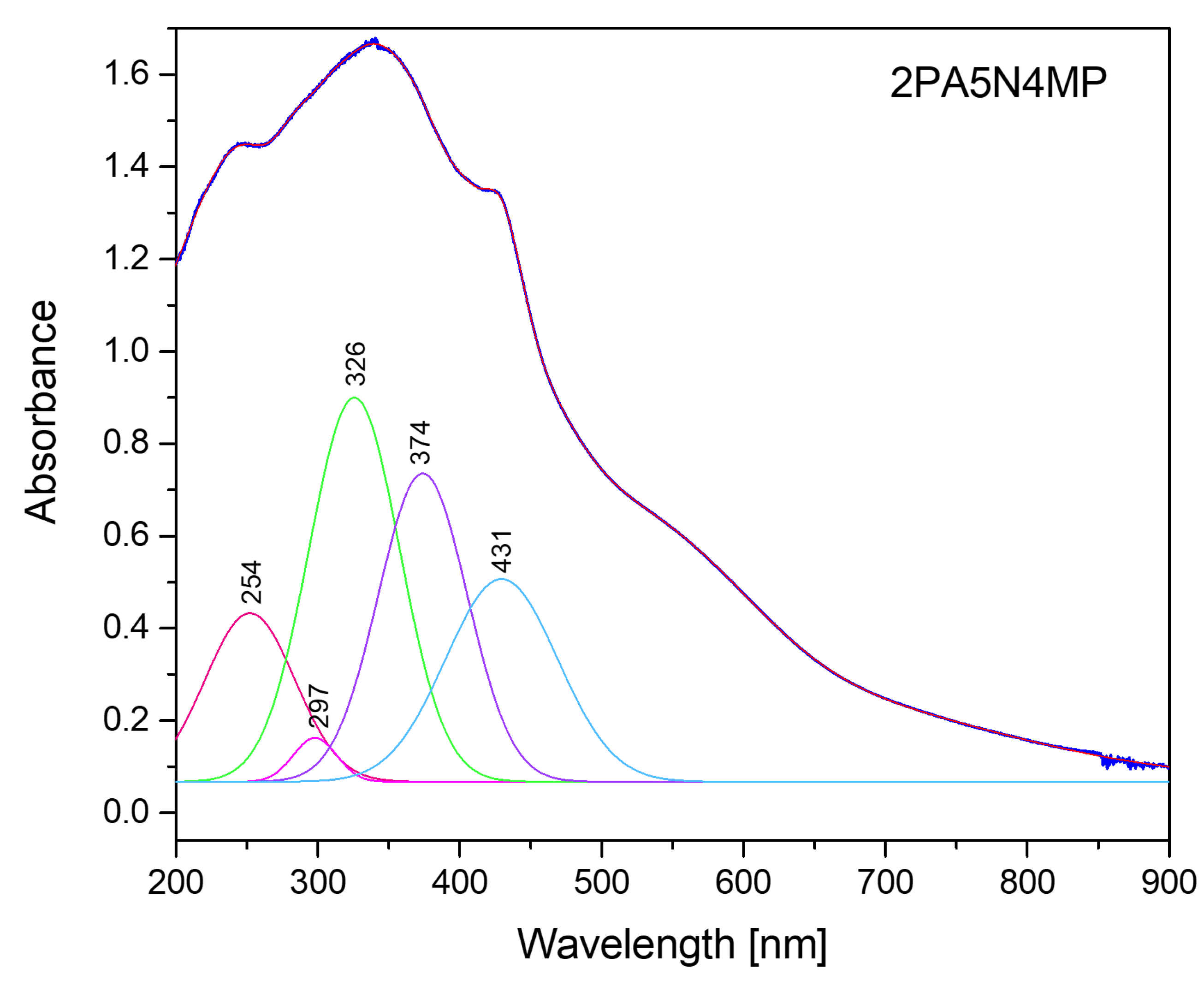

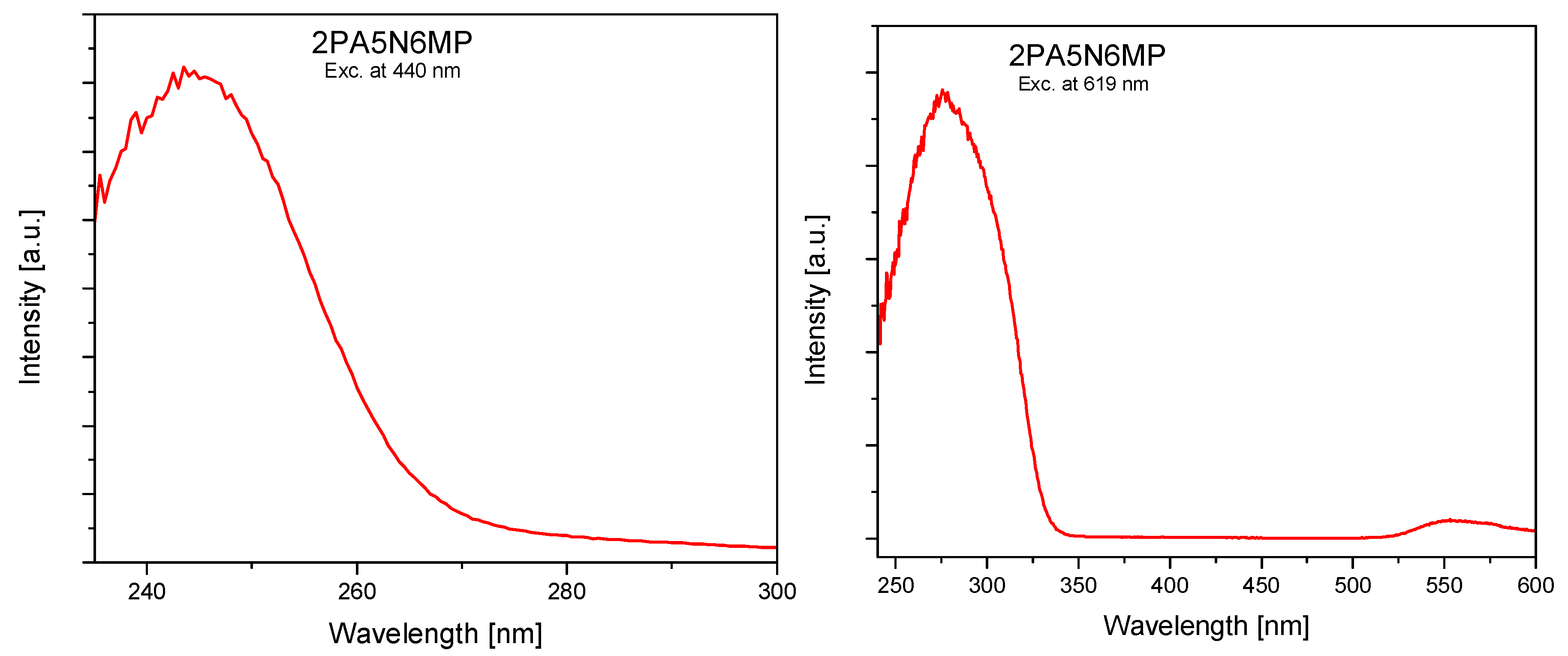

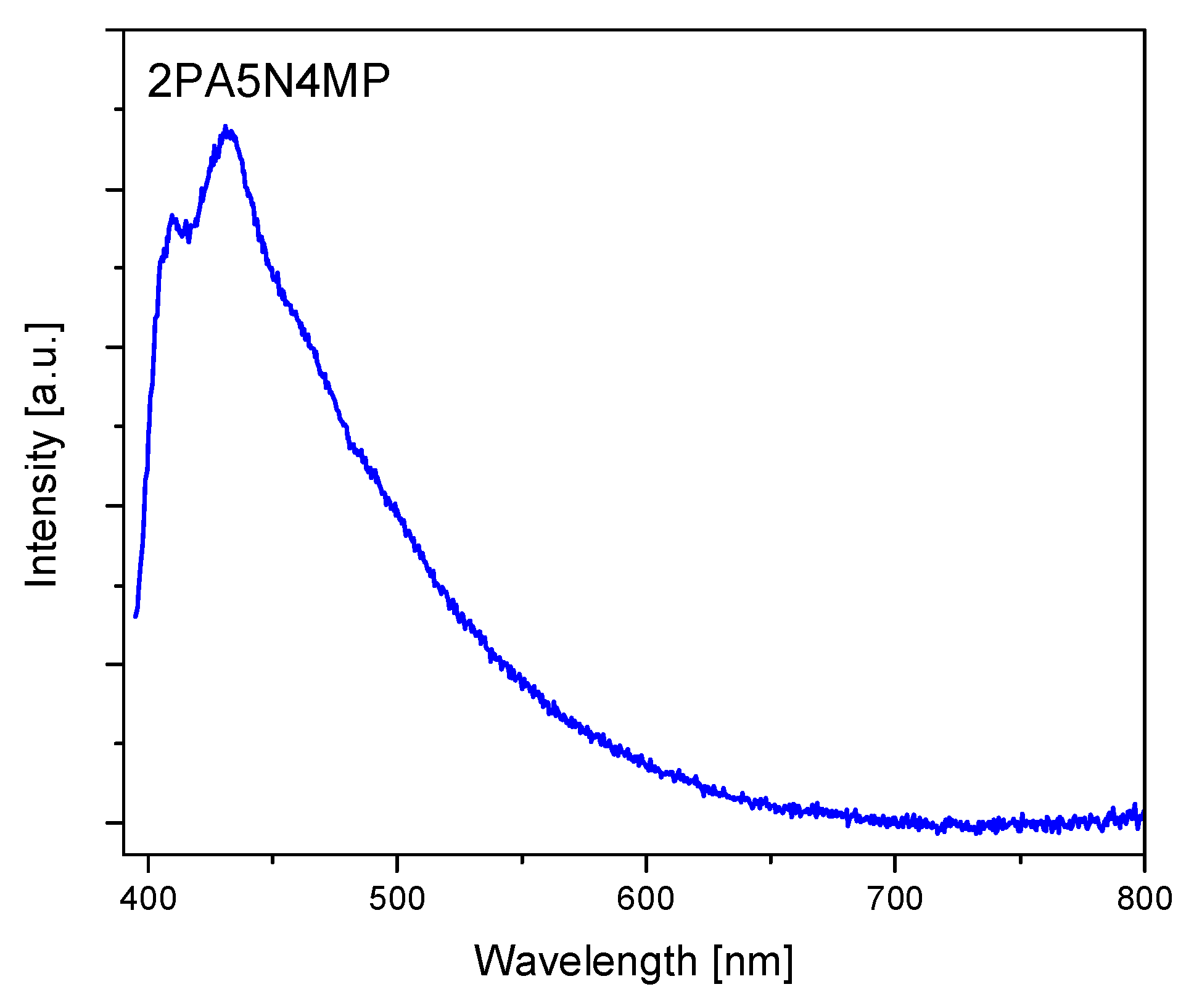

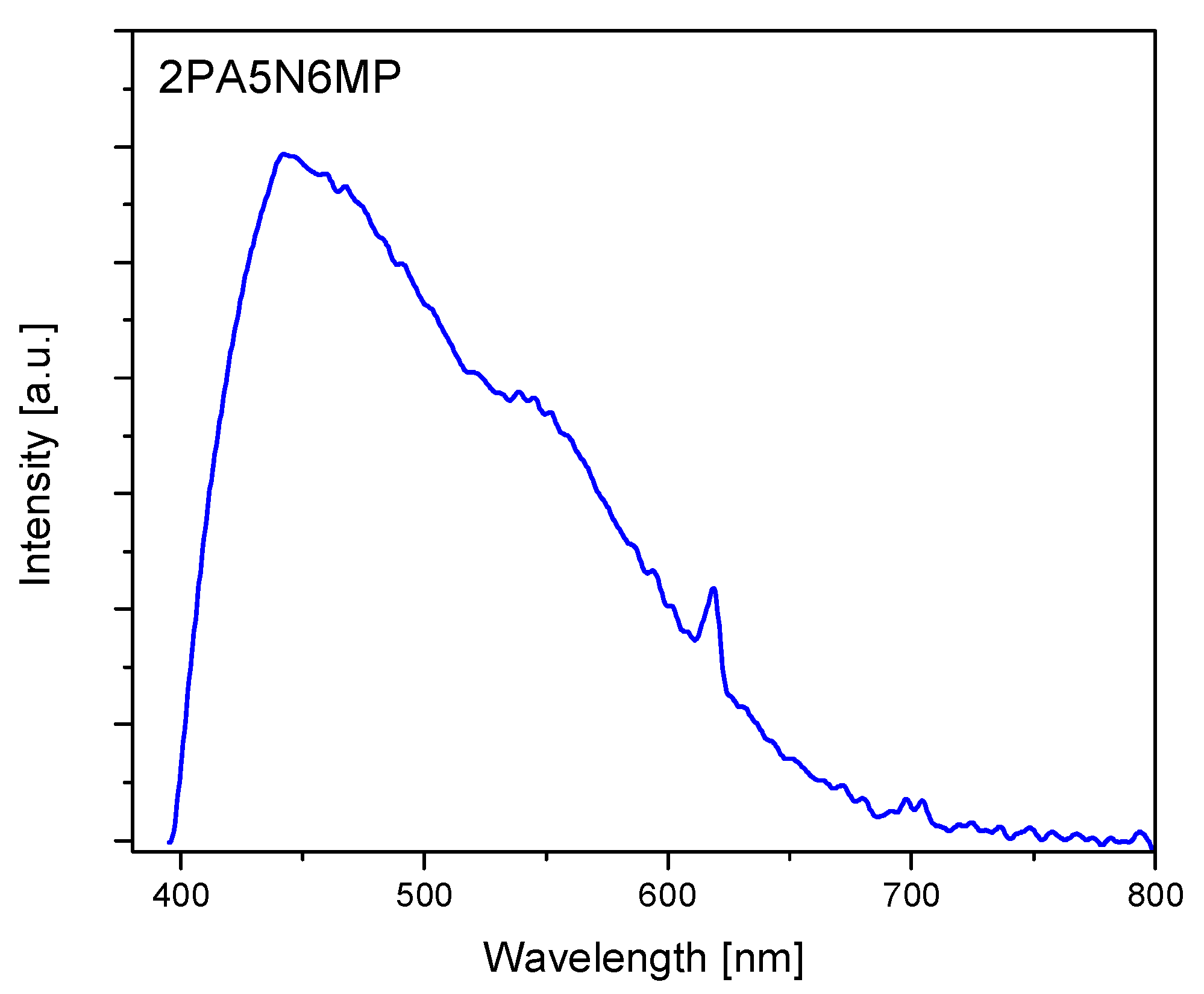

2.3. Electron Reflectance and Emission Spectra

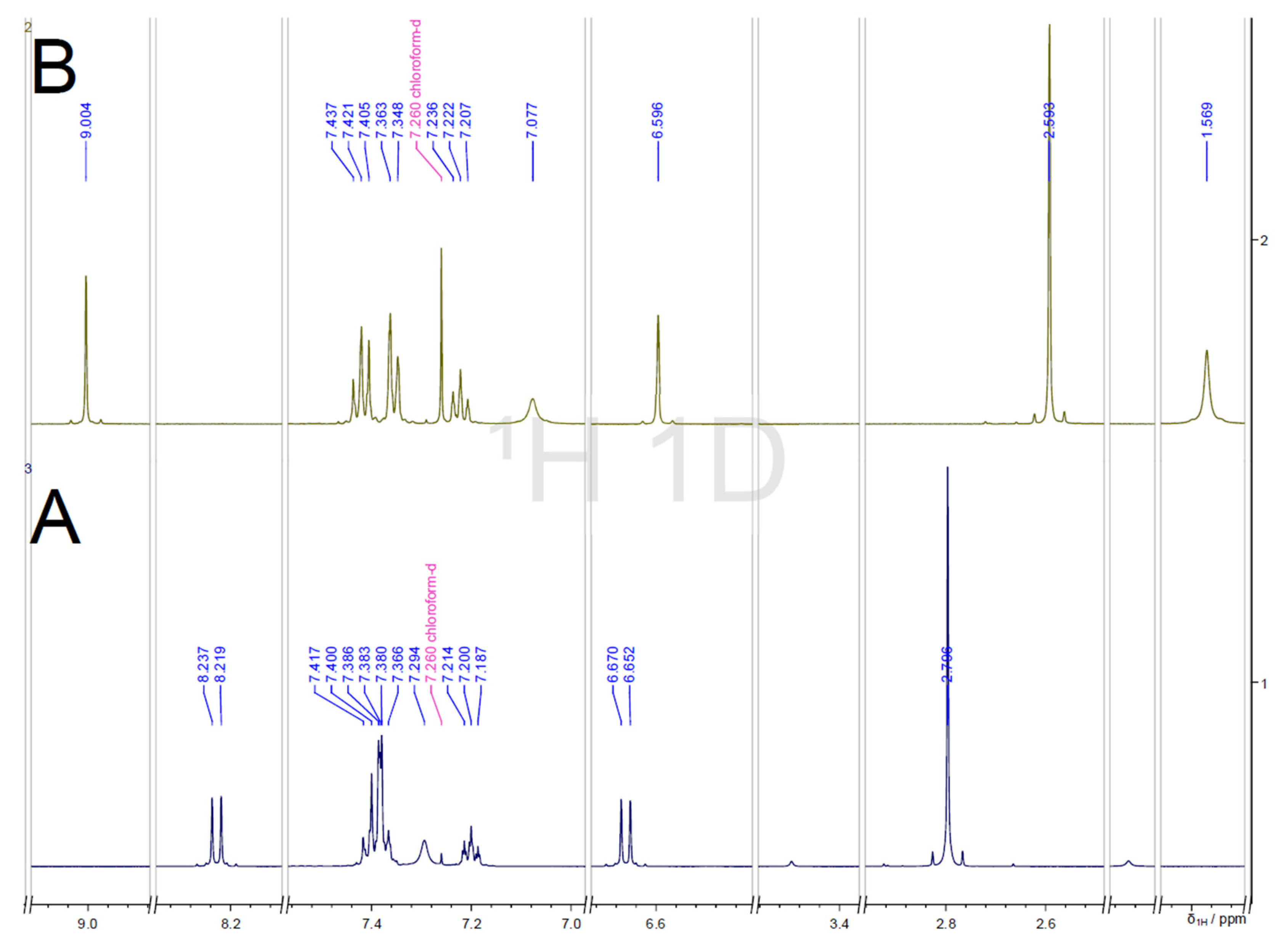

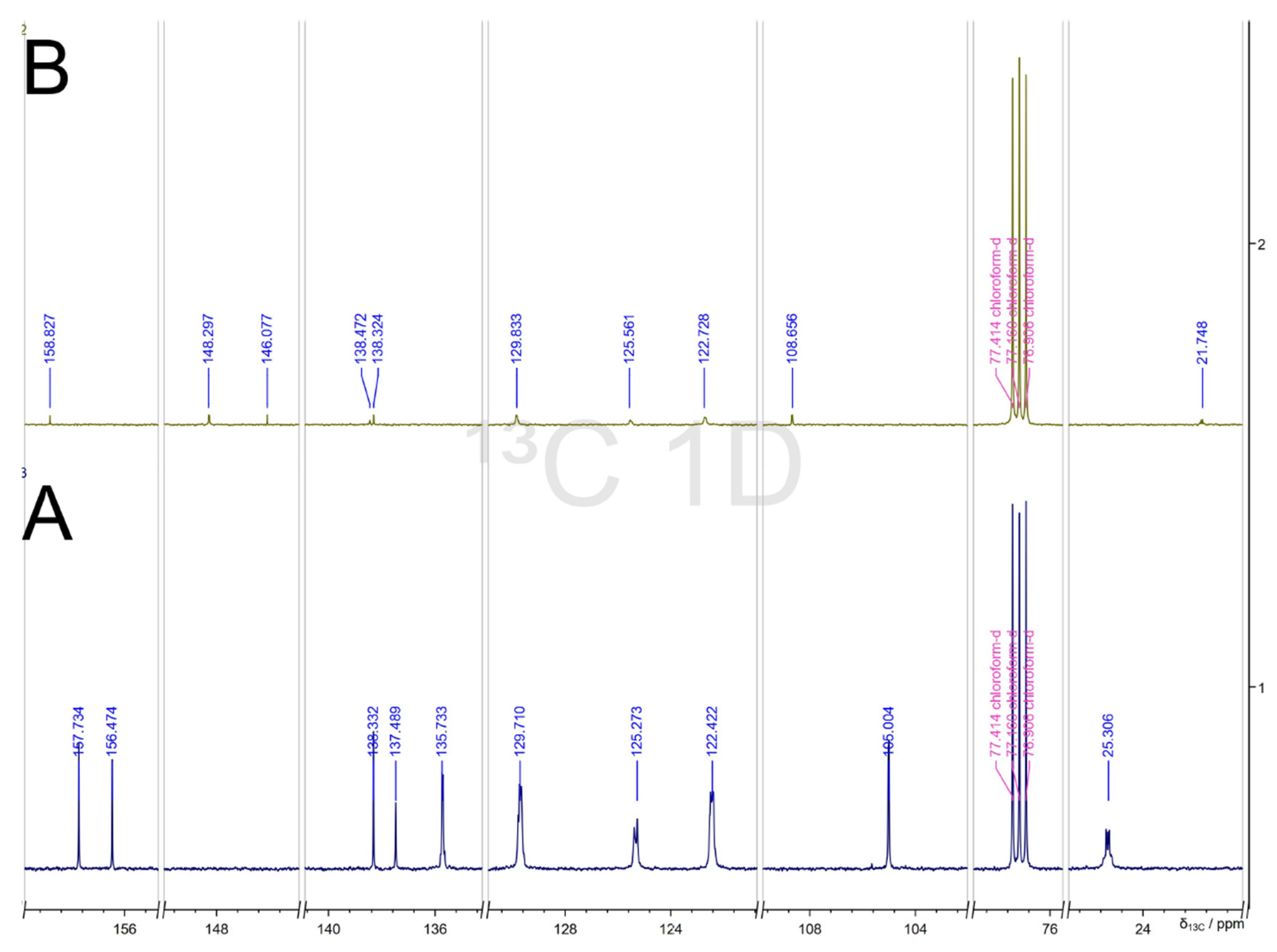

2.4. NMR Spectra

2.5. Prospective Applications of the Studied Isomers

3. Materials and Methods

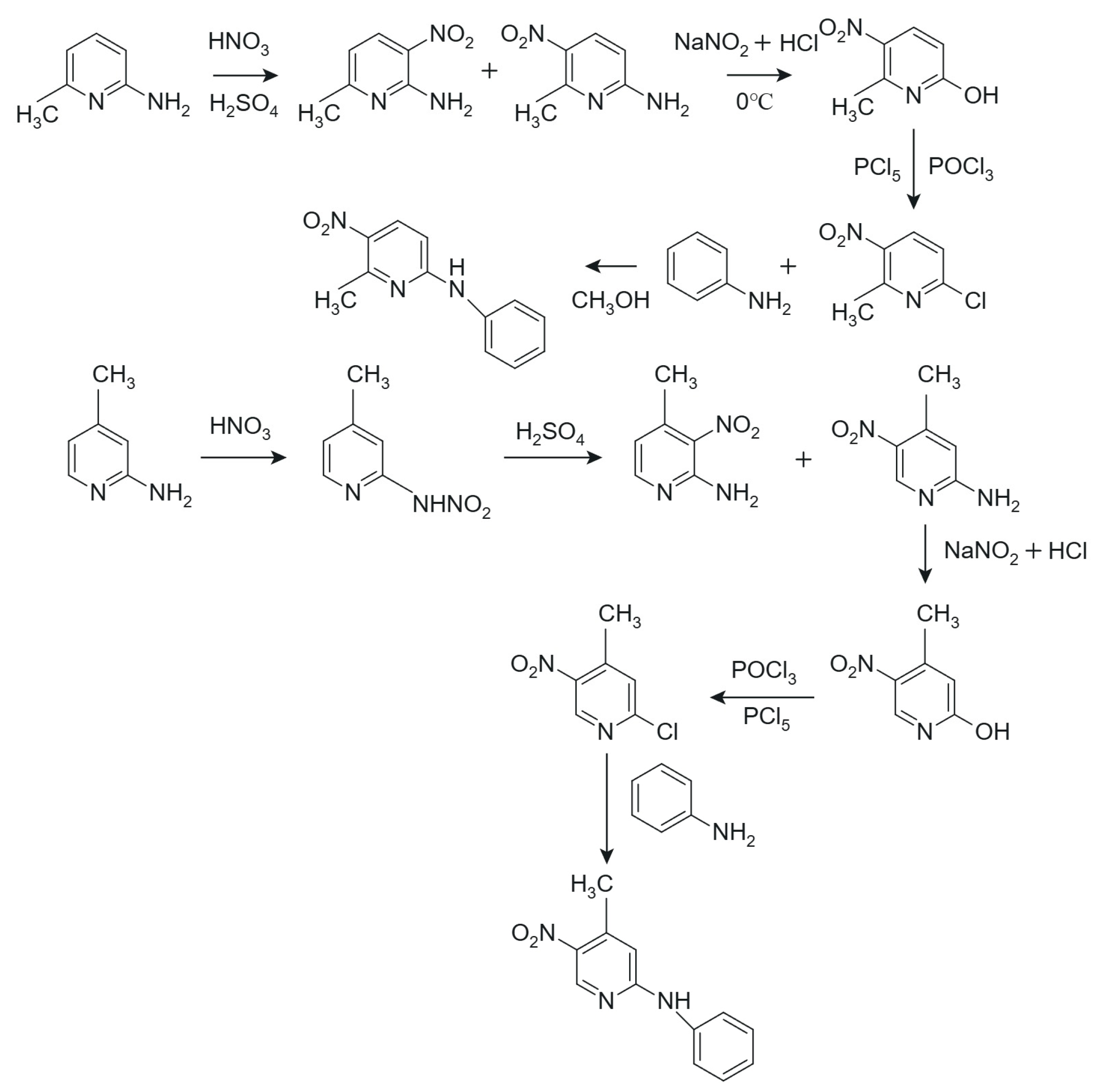

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

3.3. Infrared and Raman Studies

3.4. Electron Absorption Spectra

3.5. Emission Spectra Measurements

3.6. Quantum Chemical Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supporting Information

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hagenmaier, H.; Keckeisen, A.; Dehler, W.; Fiedler, H.P.; Zahner, H.; König, W.A. Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen, 199 Konstitutionsaufklärung der Nikkomycine I, J, M und N. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1981, 6, 1018e1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, H.; Sawa, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Naganawa, H.; Hamada, M.; Takeuchi, T. Isolation and structure determination of novel phosphatidylinositol turnover inhibitors, piericidin B5 and B5 N-oxide, from Streptomyces sp. J. Antibiot. 1993, 46, 564e568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M.; Bauch, F.; Henkel, T.; Mühlbauer, A.; Müller, H.; Spaltmann, F.; Weber, K. Antifungal Actinomycete Metabolites Discovered in a Differential Cell-Based Screening Using a Recombinant TOPO1 Deletion Mutant Strain. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Med. Chem. 2001, 334, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewick, P.M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maskey, R.P.; Huth, F.; Grün-Wollny, I.; Laatsch, H.; Naturforsch, Z. 2-Alkyl-3,4-dihydroxy-5-hydroxymethylpyridine Derivatives: New Natural Vitamin B6 Analogues from a Terrestrial Streptomyces sp. Z. Für Naturforschung B 2005, 60b, 63–66. Available online: http://www.znaturforsch.com/ab/v60b/s60b0063.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- El-Gazzar, A.-R.B.A.; Hussein, H.A.R.; Hafez, H.N. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thieno [2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives for anti-inflammatory, analgesic and ulcerogenic activity. Acta Pharm. 2007, 57, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.H.; Savas, Ü.; Lasker, J.M.; Jonson, E.F. Genistein Resveratrol 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside Induce Cytochrome P450 4F2 Expression through an AMP-Activated Protein Kinase-Dependent Pathway. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 337, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardino, A.M.R.; de Azevedo, A.R.; Pinheiro, L.C.d.S.; Borges, J.C.; Carvalho, V.L.; Miranda, M.D.; de Meneses, M.D.F.; Nascimento, M.; Ferreira, D.; Rebello, M.A.; et al. Synthesis and antiviral activity of new 4-(phenylamino)/4-[(methylpyridin-2-yl)amino]-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-4-carboxylic acids derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2007, 16, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.-Y.; Zuo, W.-Q.; Xu, Y.; Gao, C.; Zeng, X.-X.; Zhang, L.-D.; You, X.-Y.; Peng, C.-T.; Shen, Y.; Yang, S.-Y.; et al. Discovery and structure–activity relationships study of novel thieno[2,3-b]pyridine analogues as hepatitis C virus inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elansary, A.K.; Moneer, A.A.; Kadry, H.H.; Gedawy, E.M. Synthesis and anticancer activity of some novel fused pyridine ring system. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2012, 35, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, A.; Abbate, L.; Patella, C.; Martorana, A.; Dattolo, G.; Almerico, A.M. New annelated thieno[2,3-e][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines, with potent anticancer activity, designed through VLAK protocol. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 62, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohareb, R.M.; Al-Omran, F.; Azzam, R.A. Heterocyclic ring extension of estrone: Synthesis and cytotoxicity of fused pyran, pyrimidine and thiazole derivatives. Steroids 2014, 84, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhoo, A.R.; Miri, R.; Arianpour, N.; Firuzi, O.; Ebadi, A.; Salarian, A.A. Cytotoxic activity assessment and c-Src tyrosine kinase docking simulation of thieno[2,3-b] pyridine-based derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2014, 23, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Ahmed, O.M.; Elgendy, H.S. Novel Synthesis of Puriens analougues and Thieno[2,3-b] pyridine derivatives with anticancer and antioxidant activity. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 8, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhite, E.A.; Abdel-Rahman, A.E.; Mohamed, O.S.; Thabet, E.A. Synthesis, reactions and antimicrobial activity of new cyclopenta[e]thieno[2,3-b]pyridines and related heterocyclic systems. Pharmazie 2000, 55, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Altalbawy, F.M.A. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Some Novel Bis-α,β-Unsaturated Ketones, Nicotinonitrile, 1,2-Dihydropyridine-3-carbonitrile, Fused Thieno[2,3-b]pyridine and Pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine Derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 2967–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumpus, N.N.; Johnson, E.F. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide-ribonucleoside (AICAR)-Stimulated Hepatic Expression of Cyp4a10, Cyp4a14, Cyp4a31, and Other Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α-Responsive Mouse Genes Is AICAR 5′-Monophosphate-Dependent and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase-Independent. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 339, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyton, K.J.; Liu, X.M.; Yu, Y.; Yates, B.; Durante, W. Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Inhibits the Proliferation of Human Endothelial Cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 342, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajiama, K.; Komiyama, Y.; Hojo, H.; Ohba, S.; Yano, F.; Nishikawa, N.; Aburatani, H.; Takato, T.; Chung, U. Enhancement of bone formation ex vivo and in vivo by a helioxanthin-derivative. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 395, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Hojo, H.; Shimohata, N.; Choi, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Takato, T.; Chung, U.; Ohba, S. Bone healing by sterilizable calcium phosphate tetrapods eluting osteogenic molecules. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 5530–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemba, T.; Ninomiya, M.; Matsunaga, K.; Ueda, M. Effects of a novel calcium antagonist, S-(+)-methyl-4,7-dihydro-3-isobutyl-6- methyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl)thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-5-carboxylate (S-312-d), on ischemic amino acid release and neuronal injury in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993, 265, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerru, N.; Gummidi, L.; Maddila, S. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Baxendale, I. An overview of the synthetic routes to the best selling drugs containing 6-membered heterocycles. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2265–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishbaugh, T. Six-membered ring systems: Pyridine and benzo derivatives. Prog. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 24, 343–391. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A. A review: Biological importance of heterocyclic compounds. Der Pharma Chem. 2017, 9, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, P.; Arora, V.; Lamba, H. Importance of heterocyclic chemistry: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 2947–2955. [Google Scholar]

- Nevase, M.; Pawar, R.; Munjal, P. Review on various molecule activity, biological activity and chemical activity of pyridine. Eur. J. Pharm. Med. Res. 2018, 5, 184–192. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.; Sethy, S.; Sameena, T. Pyridine and its biological activity: A review. Asian J. Res. Chem. 2013, 6, 888–899. [Google Scholar]

- Chaubey, A.; Pandeya, S. Pyridine: A versatile nucleus in pharmaceutical field. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res 2011, 4, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Altaf, A.; Shahzad, A.; Gul, Z. A review on the medicinal importance of pyridine derivatives. J. Drug Des. Med. Chem. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharychev, V.; Kuzenkov, A.; Martsynkevich, A. Good pyridine hunting: A biomimic compound, a modifier and a unique pharmacophore in agrochemicals. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2020, 56, 1491–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Jiang, Z.; Lalancette, R.A.; Tang, X.; Jäkle, F. Near-Infrared-Absorbing B–N Lewis Pair-Functionalized Anthracenes: Electronic structure tuning, conformational isomerism, and applications in photothermal cancer therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 18908–18917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Wen, S.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, D. Oxygen-Promoted 6-endo-trig Cyclization of β,γ-Unsaturated Hydrazones/Ketoximes with Diazonium Tetrafluoroborates for Pyridazin-4(1H)-ones/Oxazin-4(1H)-ones. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 6110–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qin, C.; Wang, E.; Li, Y.; Hao, N.; Hu, C.; Xu, L. Synthese, structures and photoluminescence of a novel class of metal complexes constructed from pyridine-3,4-dicarboxylicacid. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 1850–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.Y.; Dai, J. Main group metal chalcogenidometalates with transition metal complexes of 1,10-phenanthroline and 2,2′-bipyridine. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 330, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.K. Chemistry with Schiff bases of pyridine derivatives: Their potential as bioactive ligands and chemosensors. In Exploring Chemistry with Pyridine Derivatives; Pal, S., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhail, M.A.; Smith, K.J.; Freire, D.M.; Pota, K.; Nguyen, N.; Burnett, M.E.; Green, K.N. Increased Efficiency of a Functional SOD Mimic Achieved with Pyridine Modification on a Pyclen-Based Copper(II) Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 5415–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S. Pyridine: A useful ligand in transition metal complexes. Pyridine 2018, 57, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahoš, B.; Kotek, J.; Cı́sařová, I.; Hermann, P.; Helm, L.; Lukeš, I.; Tóth, É. Mn2+ Complexes with 12-Membered Pyridine Based Macrocycles Bearing Carboxylate or Phosphonate Pendant Arm: Crystallographic, Thermodynamic, Kinetic, Redox, and 1H/17O Relaxation Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 12785–12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubenko, A.D.; Egorova, B.V.; Kalmykov, S.N.; Shepel, N.E.; Karnoukhova, V.A.; Fedyanin, I.V.; Fedorov, Y.V.; Fedorova, O.A. Out-cage metal ion coordination by novel benzoazacrown bisamides with carboxyl, pyridyl and picolinate pendant arms. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 2848–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Dey, S.K.; Kairmakar, S.; Mukherjee, Z. Structure and properties of metal complexes of a pyridine based oxazolidione synthesized by atmospheric CO2 fixation. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 38817–38826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.S.; Costa, J.; Gaspar, J.; Rueff, J.; Cabral, M.F.; Cipriano, M.; Castro, M.; Oliveira, N.G. Development of pyridine-containing macrocyclic copper(II) complexes: Potential role in the redox modulation of oxaliplatin toxicity in human breast cells. Free Radic. Res. 2012, 46, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.S.; Cabral, M.F.; Costa, J.; Castro, M.; Delgado, R.; Drew, M.G.B.; Félix, V. Two macrocyclic pentaaza compounds containing pyridine evaluated as novel chelating agents in copper(II) and nickel(II) overload. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011, 105, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taki, M.; Kawashima, Y.; Sakai, N.; Hirayama, T.; Yamamoto, Y. Effects of Heteroatom Substitution on the Structures, Physicochemical Properties, and Redox Behavior of Nickel(II) Complexes with Pyridine-Containing Macrocyclic Ligands. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2008, 81, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, K.P.; Delgado, R.; Drew, M.G.B.; Félix, V. Bis- and tris-(3-aminopropyl) derivatives of 14-membered tetraazamacrocycles containing pyridine: Synthesis, protonation and complexation studies. Dalton Trans. 2006, 166, 4124–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonnière, L.J.; Nonat, A.M.; Knighton, R.C.; Godec, L. Upconverting Photons at the Molecular Scale with Lanthanide Complexes. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3048–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.C.; Cao, R.; Hong, M.; Sun, D.; Zhao, Y.; Weng, J.; Wang, R. Syntheses and Characterizations of Two Novel Ln(III)–Cu(II) Coordination Polymers Constructed by Pyridine-2,4-Dicarboxylate Ligand. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2002, 5, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Z.A.; Ajlouni, A.M.; Hijazi, A.K.; Al-Rawashdeh, N.A.; Al-Hassan, K.A.; Al-Haj, Y.A.; Ebqa’i, M.A.; Altalafha, A.Y. Synthesis and Luminescent Spectroscopy of Lanthanide Complexes with Dimethylpyridine-2,6-Dicarboxylate (dmpc). J. Lumin 2015, 161, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, C.S.; Buron, F.; Caillé, F.; Shade, C.M.; Drahoš, B.; Pellegatti, L.; Zhang, J.; Villette, S.; Helm, L.; Pichon, C.; et al. Pyridine-Based Lanthanide Complexes Combining MRI and NIR Luminescence Activities. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2011, 18, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, A.; Cristobal-Cueto, P.; Hidalgo, T.; Vitórica-Yrezábal, I.J.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Horcajada, P.; Rojas, S. Potential Antiprostatic Performance of Novel Lanthanide-Complexes Based on 5-Nitropicolinic Acid. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 29, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-P.; Kang, B.-S.; Wong, W.-K.; Su, C.-Y.; Liu, H.-Q. Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Luminescent Properties of Lanthanide Complexes with Tripodal Ligands Bearing Benzimidazole and Pyridine Groups. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, N.; Zhou, X.; Shi, Y.; He, Q. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Studies of Lanthanide Complexes with 2,6-Pyridine Dicarboxylic Acid and α-Picolinic Acid. J. Coord. Chem. 2010, 63, 2360–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, A.; Bonomo, R.R.; Cucinotta, V.; Seminara, A. Lanthanide Complexes with N-Oxides: Complexes with Pyridine 1-Oxide, 2,2′-Bipyridine 1,1′-Dioxide, and 2,2′,2″-Terpyridine 1,1′,1″-Trioxide. Inorganica Chim. Acta 1982, 59, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, P.; Bryndal, I.; Hanuza, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Janczak, J.; Macalik, L.; Lis, T.; Lorenc, J.; Cieplik, J. Structure and optical properties of 3-bromo-4-methylthio-2,6-lutidine N-oxide and its eight-coordinate europium(III) and terbium(III) aqua complexes. J. Lumin. 2021, 234, 117900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, P.; Sąsiadek, W.; Kucharska, E.; Ropuszyńska-Robak, P.; Dymińska, L.; Janczak, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Ptak, M.; Hanuza, J. Structural, spectroscopic properties ant prospective application of a new nitropyridine amino N-oxide derivative: 2-[(4-nitropyridine-3-yl)amino]ethan-1-ol N-oxide. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 305, 123426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, P.; Hanuza, J.; Hermanowicz, K.; Lisiecki, R.; Lorenc, J.; Ryba-Romanowski, W.; Kucharska, E.; Ptak, M.; Macalik, L. Optical properties of terbium(III) and gadolinium(III) complexes with 2-hydroxy-5-methyl-3-nicotinic and 5-methyl-3-nicotinic acids—A new sensitive ligands for energy-transfer process. Opt. Mater. 2020, 109, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, P.; Hanuza, J.; Kucharska, E.; Solarz, P.; Roszak, S.; Kaczmarek, S.M.; Leniec, G.; Ptak, M.; Kopacz, M.; Hermanowicz, K. Optical and magnetic properties of lanthanide(III) complexes with quercetin-5′-sulfonic acid in the solid state and silica glass. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1219, 128504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, P.; Macalik, L.; Lorenc, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Ryba-Romanowski, W.; Hanuza, J.; Kaczmarek, S.M.; Fuks, H.; Leniec, G. Optical and magnetic properties of neodymium(III)six-coordinate complexes of 2,6-lutidine N-oxide derivatives. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 276, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, J.; Kucharska, E.; Michalski, J.; Hanuza, J.; Mugeński, E.; Chojnacki, H. Excited electronic states of 2-ethylamino-(3- or 5-methyl)-4-nitropyridine. J. Mol. Struct. 2002, 614, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, J.; Kucharska, E.; Hanuza, J.; Chojnacki, H. Excited electronic states of 2-ethylamino-(3 or 5)-methyl-4-nitropyridine and 2-methylamino-(3 or 5)-methyl-4-nitropyridine. J. Mol. Struct. 2004, 707, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.; Kucharska, E.; Wandas, M.; Hanuza, J.; Waśkowska, A.; Mączka, M.; Talik, Z.; Olejniczak, S.; Potrzebowski, M.J. Crystal Structure, Vibrational and NMR Studies and Chemical Quantum Calculations of 2-phenylazo-5-nitro-6-methyl-pyridine (C12H10N4O2). J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 744–747, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Maczka, M.; Hermanowicz, K.; Pikul, A.; Hanuza, J. Temperature-dependent Raman and IR Studies of Multiferroic MnWO4 Doped with Ni2+ Ions. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 86, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandas, M.; Lorenc, J.; Kucharska, E.; Maczka, M.; Hanuza, J. Molecular Structure and Vibrational Spectra of 3 (or 4 or 6)-methyl-5-nitro-2-pyridinethiones: FT-IR, FT-Raman and DFT Quantum Chemical Calculations. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2008, 39, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, J. A comprehensive vibrational study of substituted 2-ethylamino-4-nitropyridine derivatives. Vib. Spectrosc. 2012, 61, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.; Kucharska, E.; Sąsiadek, W.; Lorenc, J.; Hanuza, J. Intra- and Inter-molecular Hydrogen Bonds, Conformation and Vibrational Characteristics of Hydrazo-group in 5-nitro-2-(2-phenylhydrazinyl)Pyridine and Its 3-, 4- or 6-methyl Isomers. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 112, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryndal, I.; Kucharska, E.; Wandas, M.; Lorenc, J.; Hermanowicz, K.; Mączka, M.; Bryndal, I.; Kucharska, E.; Wandas, M.; Lorenc, J.; et al. Optical properties of new hybrid materials based on 2-amino-4-methyl-3-nitropyridine derivatives. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 117, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenc, E.; Maczka, M.; Hermanowicz, K.; Waskowska, A.; Puszko, A.; Hanuza, J. Temperature-dependent IR and Raman spectroscopic studies of 2-ethylamino-4-nitropyridine. Vib. Spectrosc. 2005, 37, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, J.; Hanuza, J.; Janczak, J. Structure and vibrational studies of 3- or 5-methyl-substituted 2-ethylamino-4-nitropyridine N-oxides. Vib. Spectrosc. 2012, 59, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. BN Lewis Pair-functionalized Anthracenes. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers University Community Repository; Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Liu, F.; Yang, C.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Qi, Z. Au/Ag synergistic catalysis of synthesis of 4 H -imidazo-oxadiazin-4-ones via three-component domino cyclization. Org. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 5862–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, H.; Tan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, P.; Qin, J. Ten-gram-scale mechanochemical synthesis of ternary lanthanum coordination polymers for antibacterial and antitumor activities. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 898324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, J.; Xiang, D.; Luo, S.; Hu, X.; Tang, T.; Sun, T.; Liu, X. Micelles Loaded With Puerarin And Modified with Triphenylphosphonium Cation Possess Mitochondrial Targeting And Demonstrate Enhanced Protective Effect Against Isoprenaline-Induced H9c2 Cells Apoptosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 8345–8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, I.; Lorenc, J.; Macalik, L.; Michalski, J.; Sąsiadek, W.; Lis, T.; Hanuza, J. Crystal structure, vibrational and optic properties of 2-N-methylamino-3-methylpyridine N-oxide–Its X-ray and spectroscopic studies as well as DFT quantum chemical calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1195, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macalik, L.; Wandas, M.; Sąsiadek, W.; Lorenc, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Hanuza, J. Molecular structure and spectroscopic properties of new neodymium complex with 3-bromo-2-chloro-6-picolinic N-oxide showing the ligand-to-metal energy transfer. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1223, 128967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, J.; Bryndal, I.; Syska, W.; Wandas, M.; Marchewka, M.; Pietraszko, A.; Lis, T.; Mączka, M.; Hermanowicz, K.; Hanuza, J. Order–disorder phase transitions and their influence on the structure and vibrational properties of new hybrid material: 2-Amino-4-methyl-3-nitropyridinium trifluoroacetate. Chem. Phys. 2010, 374, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, I.; Kucharska, E.; Sąsiadek, W.; Wandas, M.; Lis, T.; Lorenc, J.; Hanuza, J. Molecular and crystal structures, vibrational studies and quantum chemical calculations of 3 and 5-nitroderivatives of 2-amino-4-methylpyridine, Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 96, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, I.; Marchewka, M.; Wandas, M.; Sąsiadek, W.; Lorenc, J.; Lis, T.; Dymińska, L.; Kucharska, E.; Hanuza, J. The role of hydrogen bonds in the crystals of 2-amino-4-methyl-5-nitropyridinium trifluoroacetate monohydrate and 4-hydroxybenzenesulfonate—X-ray and spectroscopic studies, Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 123, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sąsiadek, W.; Bryndal, I.; Lis, T.; Wandas, M.; Hanuza, J. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of the methyl-nitro-pyridine-disulfide: X-ray, NMR, electron absorption and emission, IR and Raman studies and quantum chemical calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1257, 132535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, J. Dimeric structure and hydrogen bonds in 2-N-ethylamino-5-metyl-4-nitro-pyridine studied by XRD, IR and Raman methods and DFT calculations. Vib. Spectrosc. 2012, 61, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, J.; Zając, A.; Janczak, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Hanuza, J.; Hermanowicz, K. Structure and optical properties of new nitro-derivatives of 2-N-alkiloamino-picoline N-oxide isomers. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1265, 133372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandas, M.; Kucharska, E.; Michalski, J.; Talik, Z.; Lorenc, J.; Hanuza, J. Experimental and simulated 1H and 13C NMR spectra (GIAO/DFT approach0 and molecular and crystal spructures of dimethyl-dinitro-azo-mand dimethyl-dinitro-hydrazo-pyridines. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 1004, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Al-Najjar, H.J.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Shaik, M.R.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Fun, H.K. Synthesis, NMR, FT-IR, X-ray Structural Characterization, DFT Analysis and Isomerism Aspects of 5-(2,6-dichlorobenzylidene)Pyrimidine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 147, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carthigayan, K.; Xavier, S.; Periandy, S. HOMO–LUMO, UV, NLO, NMR and Vibrational Analysis of 3-methyl-1-phenylpyrazole Using FT-IR, FT-RAMAN FT-NMR Spectra and HF-DFT Computational Methods. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 142, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puszko, A.; Wasylina, L. The influence of steric effect on 1H NMR, 13C NMR and IR spectra of methylated derivatives of 4-nitropyridine N-oxide. Chem. Pap. 1995, 49, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kątcka, M.; Urbański, T. NMR spectra of pyridine, picolines and hydrochlorides and of their hydrochlorides and methiodides. Bull. Acad. Pol. Sci. 1968, 16, 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Talik, Z.; Palasek, B. Synthesis of some sulfur derivatives of 3,5-dinitro-6-methylpyridines. Prace Nauk. AE Wrocław 1984, 255, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaku Oxford Diffraction. CrysAlis CCD and CrysAlis RED, Version 1.171.38.43; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Ltd.: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71 Pt 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71 Pt 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, K.; Putz, H. DIAMOND Version 3.0, Crystal Impact GbR: Bonn, Germany, 2006.

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; et al. Gaussian 03, Revision, A.1; Gaussian Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. IV. A new dynamical correlation functional and implications for exact-exchange mixing. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the density-functional exchange-energy approximation. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, W.; Becke, A.D.; Parr, R.G. Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, A.D.; Chandler, G.S. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z = 11–18. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostkowska, H.; Lapinski, L.; Nowak, M.J. Infrared spectra of monomeric s-triazine and cyanuric acid: Analysis of the normal modes of molecules with D3h symmetry. Vib. Spectrosc. 2009, 49, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GaussView 4.1. Quantum Chemical Studies on Structural, Vibrational, Nonlinear Optical Properties and Chemical Reactivity of Indigo Carmine Dye; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurko, G.A.; Zhurko, D.A. Chemcraft Graphical Program for Visualization of Computed Results. Available online: http://www.chemcraftprog.com (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Palafox, M.A.; Rastogi, V.K. Quantum chemical predictions of the vibrational spectra of polyatomic molecules: The uracil molecule and two derivatives. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2002, 58, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalska, D. RAINT (Raman Intensities), Computer Program for Calculation of Raman Intensities from the Gaussian Outputs; Wrocław University of Technology: Wrocław, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Mol. A | Mol. B | Mol. C | Mol. D | DFT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N3—O1 | 1.217 (4) | 1.231 (4) | 1.237 (4) | 1.244 (4) | 1.229 | |

| N3—O2 | 1.237 (4) | 1.233 (4) | 1.232 (4) | 1.238 (4) | 1.230 | |

| C5—N3 | 1.468 (5) | 1.466 (5) | 1.462 (5) | 1.457 (5) | 1.458 | |

| C2—N2—C7 | 127.7 (3) | 127.4 (3) | 131.2 (4) | 127.0 (4) | 129.98 | |

| Dihedral angle between the planes: | ||||||

| NO2 (O1N3O2)/pyridine ring (N1, C2–C6) pyridine ring (N1, C2–C6)/phenyl ring (C7–C12) | 20.0 (3) | 21.9 (3) | 5.6 (3) | 11.3 (3) | 15.80 | |

| 45.1 (3) | 50.3 (3) | 35.6 (3) | 50.2 (3) | 44.70 | ||

| Hydrogen-bond geometry in crystal (Å, °) | ||||||

| D—H···A | D—H | H···A | D···A | D—H···A | ||

| N2A—H21···N1B | 0.96 (4) | 2.07 (4) | 3.021 (4) | 172 (3) | ||

| N2B—H22···N1A | 0.85 (2) | 2.20 (2) | 3.041 (5) | 171 (4) | ||

| N2C—H23···N1D | 0.85 (4) | 2.21 (4) | 3.032 (5) | 163 (4) | ||

| N2D—H24···N1C | 0.91 (4) | 2.07 (4) | 2.975 (5) | 174 (4) | ||

| Hydrogen bonds in dimer in gas phase (Å, °) | ||||||

| D—H···A | D—H | H···A | D···A | D—H···A | ||

| N2A–H21···N1B | 1.029 | 2.005 | 3.030 | 173.97 | ||

| N2B–H22···N1A | 1.029 | 2.005 | 3.030 | 173.97 | ||

| X-Ray | DFT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N3—O1/N23—O21 | 1.239 (2)/1.239 (2) | 1.242 | |||

| N3—O2/N23—O21 | 1.243 (2)/1.238 (2) | 1.226 | |||

| C5—N3/C25—N23 | 1.436 (3)/1.437 (3) | 1.454 | |||

| C2—N2—C7/C22—N22—C27 | 131.9 (2)/132.1 (2) | 131.64 | |||

| Dihedral angle between the planes: | |||||

| NO2 (O1N3O2)/pyridine ring (N1, C2–C6) | 3.50 (5)/2.40 (5) * | 0.00 | |||

| pyridine ring (N1, C2–C6)/phenyl ring (C7–C12) | 2.31 (5)/4.30 (5) * | 0.00 | |||

| D—H···A | D—H | H···A | D···A | D—H···A | |

| N22—H22···O2 | 0.87 (2) | 2.11 (3) | 2.962 (2) | 136.4 (13) | X-ray |

| C32—H32···O1 | 0.95 | 2.56 | 3.506 | 175 | X-ray |

| N2—H2···O21 * | 0.87 (2) | 2.16 (2) | 2.962 (2) | 153 | X-ray |

| C12—H12···O22 * | 0.95 | 2.62 | 3.511 (3) | 157 | X-ray |

| Symmetry code: (i) x + 1, y, z − 1. | |||||

| N2—H2···O1 | 1.014 | 1.814 | 2.632 | 135.17 | DFT |

| 2PA5N4MP | 2PA5N6MP | |

|---|---|---|

| Cϕ—NH—Cφ bridge | ||

| C2—N2 | 1.365 | 1.361 |

| N2—H2 | 0.987 | 0.870 |

| N2—C7 | 1.414 | 1.407 |

| C2—N2—C7 | 128.3 | 123.03 |

| O1—N3—02 nitro group | ||

| C3—N3 | 1.463 | 1.436 |

| N3—O1 | 1.234 | 1.239 |

| N3—O2 | 1.232 | 1.240 |

| O1—N3—O2 | 123.1 | 121.71 |

| C4—C13H3 methyl group | ||

| C4—C13 | 1.502 | 1.501 |

| C13—H | 0.980 | 0.980 |

| C13—H | 0.980 | 0.980 |

| C13—H | 0.980 | 0.980 |

| D—H···A | D—H | H···A | D···A | D—H···A [°] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2PA5N4MP (inter-molecular HB) | ||||

| N2A—H21····N1B | 0.96 | 2.07 | 3.020 | 172 |

| N2B—H22······N1A | 0.85 | 2.20 | 3.041 | 171 |

| N2C—H23·····N1D | 0.97 | 2.19 | 3.032 | 162 |

| N2D—H24·····N1C | 0.91 | 2.07 | 2.976 | 174 |

| 2PA5N6MP (inter-molecular HB) | ||||

| N22—H22·····O2 | 0.87 | 2.11 | 2.962 | 165 |

| C31—H31····O1 | 0.95 | 2.56 | 3.506 | 175 |

| N2—H2······O21′ | 0.87 | 2.16 | 2.962 | 153 |

| C11—H11····O22′ | 0/95 | 2.62 | 3.511 | 157 |

| 2PA5N4MP | 2PA5N6MP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calc. | Exp. | Calc. | Exp. | |||

| IR, RS | IR | RS | IR, RS | IR | RS | Assignment |

| 3613 vw | 3547 vs | 3344 s | νN-H | |||

| 3536 s | νN-H | |||||

| 3302 vs | 3224 w | νNHO | ||||

| 3237 | 3240 m | νsNHN | ||||

| 3215 | 3213 m | νasNHN | ||||

| 1650 s | 1624 m | 1646 vw | δNHO | |||

| 1657 v | 1623 m | δasNHN | ||||

| 1648 m | 1615 s | 1616 w | δsNHN | |||

| 1610 m | δsNHN | |||||

| 1581 w | 1580 s | 1586 w | ν(NO) + ν(ϕ) | |||

| 1572 m | 1571 s | 1597 w | δasNHN | |||

| 1546 m | 1562 sh | ν(NO) + ν(ϕ) | ||||

| 1549 w | 1553 m | ν(NO) + δNHO + δCHO | ||||

| 1543 m | 1543 vw | ν(NO) + δNHO + δCHO | ||||

| 1542 m | 1543 sh | 1545 w | 1536 m | ν(NO) + ν(ϕ) | ||

| 1500 m | ν(NO) + ν(ϕ) | |||||

| 1499 m | 1497 s | 1500 w | 1490 m | 1474 m | 1474 w | ν(NO) + ν(ϕ) |

| 1451 m | 1433 w | 1423 vw | ν(ϕ) + δ(CH3) + δasNHN | |||

| 1444 m | ν(ϕ) + δsNHN | |||||

| 1364 m | 1363 m | 1364 w | δ(NHO) + ν(ϕ) + δ(CH3) | |||

| 1338 vs | 1338 s | 1335 s | δ(NH) + ν(ϕ) | |||

| 1336 w | δ(NH) + ν(ϕ) | |||||

| 1319 vw | 1321 s | 1327 vs | νs(NO2) + ν(ϕ) + δ(CH3) | |||

| 1312 s | 1309 vs | 1306 vs | 1308 s | νs(NO2) + ν(ϕ) + δ(CH3) | ||

| 1296 w | 1297 vs | 1300 s | νs(NO2) + ν(ϕ) + δ(CH3) | |||

| 1294 w | 1309 m | 1293 s | νCN + νs(NO2) | |||

| 1287 vs | δ(NCNHO) | |||||

| 1277 vs | 1277 vs | δ(NCNHO) | ||||

| 1251 m | 1253 s | δ(NCNHO) | ||||

| 1253 w | 1251 m | 1257 m | ν(NCN) | |||

| 1249 w | 1245 w | 1227 w | 1229 w | ν(NCN) + δNH | ||

| 1234 w | 1237 m | 1237 w | ν(C-NH) | |||

| 1231 w | 1221 vw | ν(C-NH) | ||||

| 1221 w | 1207 w | ν(CN)(NH) | ||||

| 1105 m | 1108 m | 1108 w | νCN(NO2) | |||

| 1080 vw | 1078 m | 1079 w | νCN(NO2) | |||

| 834 w | 837 m | 836 w | 854 vw | 840 w | 824 w | δs(NO)ϕ + τ(ϕ) |

| 787 w | 800 w | δsNHN | ||||

| 773 w | 767 m | 756 w | δ(NO2) + ρ(CH3) | |||

| 767 w | 763 m | δsNHN | ||||

| 736 w | δNCN | |||||

| 703 m | 746 w | ρNHN | ||||

| 674 | δNHO | |||||

| 670 w | 667 w | τasNHN | ||||

| 637 w | 636 w | 635 vw | δCNCN | |||

| 224 w | 219 w | δCNC | ||||

| 202 w | δ(CNHC)ϕ+θ | |||||

| 135 sh | δ(CNHC)ϕ+θ | |||||

| Electron Levels | eV | nm | Oscillator Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| singlets | |||

| (1) | 3.3648 | 368.47 | 0.0014 |

| (2) | 3.5956 | 344.82 | 0.0080 |

| (3) | 3.6292 | 341.63 | 0.9036 |

| (4) | 3.8372 | 323.11 | 0.0004 |

| (5) | 3.8404 | 322.84 | 0.0544 |

| (6) | 4.1984 | 295.31 | 0.0003 |

| (7) | 4.2553 | 291.36 | 0.0572 |

| (8) | 4.2674 | 290.54 | 0.0007 |

| (9) | 4.2725 | 290.19 | 0.0770 |

| (10) | 4.3889 | 282.49 | 0.0143 |

| (11) | 4.4122 | 281.01 | 0.0000 |

| (12) | 4.4932 | 275.94 | 0.0003 |

| (13) | 4.4986 | 275.60 | 0.0053 |

| (14) | 4.5171 | 274.48 | 0.0018 |

| (15) | 4.5214 | 274.22 | 0.0000 |

| (16) | 4.6104 | 268.93 | 0.0998 |

| (17) | 4.6267 | 267.98 | 0.0020 |

| (18) | 4.6921 | 264.24 | 0.0033 |

| (19) | 4.7129 | 263.08 | 0.0946 |

| (20) | 4.7723 | 259.80 | 0.0270 |

| triplets | |||

| (1) | 1.6540 | 749.61 | 0.0769 |

| (2) | 1.8336 | 676.18 | 0.0041 |

| (3) | 1.9787 | 626.58 | 0.2631 |

| (4) | 2.0317 | 610.26 | 0.0001 |

| (5) | 2.0489 | 605.12 | 0.2142 |

| (6) | 2.1133 | 586.70 | 0.0017 |

| (7) | 2.2741 | 545.20 | 0.0377 |

| (8) | 2.3019 | 538.61 | 0.0000 |

| (9) | 2.3284 | 532.49 | 1.7137 |

| (10) | 2.3677 | 523.64 | 0.0000 |

| Electron Levels | eV | nm | Oscillator Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| singlets | |||

| (1) | 1.9553 | 634.08 | 0.0005 |

| (2) | 3.1721 | 390.86 | 0.0293 |

| (3) | 3.2259 | 384.34 | 0.6634 |

| (4) | 3.4036 | 364.27 | 0.6654 |

| (5) | 3.5239 | 351.84 | 0.0001 |

| (6) | 3.5842 | 345.92 | 0.0004 |

| (7) | 3.6283 | 341.71 | 0.0011 |

| (8) | 3.7496 | 330.66 | 0.0006 |

| (9) | 3.7520 | 330.45 | 0.0001 |

| (10) | 3.9468 | 314.14 | 0.0026 |

| (11) | 4.0681 | 304.77 | 0.0042 |

| (12) | 4.0948 | 302.79 | 0.0006 |

| (13) | 4.1003 | 302.38 | 0.0031 |

| (14) | 4.1303 | 300.18 | 0.0910 |

| (15) | 4.1933 | 295.67 | 0.0047 |

| (16) | 4.2553 | 291.37 | 0.0169 |

| (17) | 4.3948 | 282.12 | 0.0026 |

| (18) | 4.4714 | 277.28 | 0.0000 |

| (19) | 4.5383 | 273.20 | 0.2150 |

| (20) | 4.5518 | 272.39 | 0.0022 |

| triplets | |||

| (1) | 3.2259 | 384.34 | 0.6636 |

| (2) | 3.5239 | 351.84 | 0.0001 |

| (3) | 3.7496 | 330.66 | 0.0006 |

| (4) | 3.9468 | 314.14 | 0.0026 |

| (5) | 4.1090 | 301.74 | 0.0307 |

| (6) | 4.1933 | 295.67 | 0.0047 |

| (7) | 4.3948 | 282.12 | 0.0026 |

| (8) | 4.4714 | 277.28 | 0.0000 |

| (9) | 4.5518 | 272.39 | 0.0022 |

| (10) | 4.6538 | 266.41 | 0.0001 |

| 2PA5N4MP | 2PA5N6MP | |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C12H11N3O2 | C12H11N3O2 |

| Formula weight (g·mol–1) | 229.24 | 229.24 |

| Crystal system, space group | Orthorhombic, Pbca | Triclinic, P |

| a, (Å) | 23.6386 (14) | 7.2576 (4) |

| b, (Å) | 7.3142 (4) | 10.8585 (7) |

| c, (Å) | 49.929 (3) | 13.7842 (6) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 87.188 (4), 87.619 (4), 83.061 (5) |

| V (Å3) | 8632.6 (9) | 1076.34 (10) |

| Z | 32 | 4 |

| Dcalc (mg·cm–3) | 1.411 | 1.415 |

| μ (mm–1) | 0.100 | 0.100 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.22 × 0.12 × 0.10 | 0.23 × 0.12 × 0.10 |

| λ (Å) | Mo Kα, 0.71073 | Mo Kα, 0.71073 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) |

| θ range (°) | 2.4–7.0 | 2.5–29.3 |

| Absorption correction | multi-scan | multi-scan |

| Tmin/Tmax | 0.983/1.000 | 0.975/1.000 |

| Refls measured, | 126,761 | 12,740 |

| independent, | 9428 | 5122 |

| observwed, I > 2σ(I) | 4045 | 3601 |

| Rint | 0.099 | 0.030 |

| Refinement on F2 | ||

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)] | 0.102 | 0.058 |

| wR(F2 all reflections) a | 0.170 | 0.129 |

| Goodness-of-fit, S | 1.01 | 1.00 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å–3) | +0.27, −0.32 | +0.33, −0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godlewska, P.; Hanuza, J.; Janczak, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Ropuszyńska-Robak, P.; Dymińska, L.; Sąsiadek, W. Structural and Optical Properties of New 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-4-methylopyridine and 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-6-methylpyridine Isomers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311522

Godlewska P, Hanuza J, Janczak J, Lisiecki R, Ropuszyńska-Robak P, Dymińska L, Sąsiadek W. Structural and Optical Properties of New 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-4-methylopyridine and 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-6-methylpyridine Isomers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311522

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodlewska, Patrycja, Jerzy Hanuza, Jan Janczak, Radosław Lisiecki, Paulina Ropuszyńska-Robak, Lucyna Dymińska, and Wojciech Sąsiadek. 2025. "Structural and Optical Properties of New 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-4-methylopyridine and 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-6-methylpyridine Isomers" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311522

APA StyleGodlewska, P., Hanuza, J., Janczak, J., Lisiecki, R., Ropuszyńska-Robak, P., Dymińska, L., & Sąsiadek, W. (2025). Structural and Optical Properties of New 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-4-methylopyridine and 2-Phenylamino-5-nitro-6-methylpyridine Isomers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311522