Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) represents a critical global health threat, with ST101 identified as a major circulating clone in Saudi Arabia. We used whole genome sequencing and plasmid reconstruction to investigate the molecular characteristics of CRKP ST101 isolates from Saudi Arabia (2018–2021), analyzing antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), virulence factors, and plasmid structure and replicon types. Clinical isolates were obtained from the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs (MNGHA) hospitals in Saudi Arabia between 2018 and 2021. Whole-genome sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq® platform, followed by comprehensive bioinformatic analysis of ARGs, virulence factors, and plasmid content. All ten isolates belonged to ST101 and harbored extensive antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and virulence determinants. Nine isolates (90%) carried blaOXA-48, with three co-harboring blaNDM-1, representing dual-carbapenemase producers. These carbapenemase genes were located on plasmids with distinct replicon types, including IncL/M, IncHI1B/IncFIB, and IncFIA/IncR. All isolates were multidrug-resistant (MDR), with half classified as extensively drug-resistant (XDR). Four isolates exhibited hypervirulent profiles, harboring aerobactin and yersiniabactin siderophores. This study provides comprehensive genomic characterization of CRKP ST101 in Saudi Arabia, revealing complex resistance mechanisms mediated by diverse plasmid types. The findings highlight the importance of genomic surveillance to track the evolution and dissemination of high-risk MDR and XDR lineages and inform targeted infection control strategies.

1. Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a leading causative agent of a wide variety of community-acquired and hospital-acquired infections, including liver abscess, pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and urinary tract infections [1]. The growing acquisition of ARGs has significantly reduced the effectiveness of available treatment options, including those involving last-resort antibiotics [2,3,4]. In response to this escalating threat, the World Health Organization (WHO) included K. pneumoniae in the highest priority tier of its 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL) to guide research, policy efforts and strategies aimed at combating AMR [5]. The rapid emergence and dissemination of CRKP strains represent a significant public health concern and economic burden worldwide [6,7,8]. Multiple molecular mechanisms contribute to CRKP, often complicating therapeutic management. Key resistance mechanisms include the overproduction of β-lactamases combined with reduced outer membrane permeability, as well as the acquisition of one or more carbapenemase enzymes capable of hydrolyzing carbapenem antibiotics [9,10]. According to the Ambler classification, the major classes of carbapenemases include class A Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), class B Metallo-β-lactamases such as Verona Integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase (VIM), imipenemase (IMP), and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM), and class D (OXA-48-like oxacillinases) [11,12,13]. First identified in 2001, blaOXA-48 has become the most frequently reported carbapenemase gene in Enterobacterales and is strongly associated with hospital outbreaks worldwide [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Among the high-risk clones, sequence type 101 (ST101) has been particularly associated with the dissemination blaOXA-48 in diverse clinical settings [19]. K. pneumoniae ST101 was first defined in 2008 during the development of the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme for categorizing K. pneumoniae, although details regarding its initial clinical emergence remain limited in the published literature. Over the past decade, ST101 has gained recognition as a high-risk clone associated with AMR, supported by its increasing detection in clinical and environmental isolates worldwide [20,21]. Notable cases of CRKP ST101 strains emerged in Italy and other European countries during the early 2010s, prompting public health concerns due to their resistance to critical antibiotics [22,23]. In Saudi Arabia, ST101 has been identified as one of the predominant K. pneumoniae clones implicated in the regional dissemination of CRKP strains [24]. Despite its recognized clinical importance, comprehensive genomic data on ST101 in Saudi Arabia remain limited. This lack of molecular insight hinders our ability to understand its resistance mechanisms, virulence potential, and patterns of regional transmission. In recent years, whole genome sequencing has become a critical tool for elucidating the transmission dynamics and genetic determinants underlying the persistence and dissemination of high-risk K. pneumoniae clones. In response to this knowledge gap, we performed molecular characterization of CRKP ST101 isolates from Saudi Arabia, focusing on sequence typing, ARGs, and key virulence determinants collected over a four-year period (2018–2021). This study represents the first comprehensive genomic analysis of CRKP ST101 isolates in Saudi Arabia, offering novel insights into the distribution of resistance and virulence determinants alongside detailed plasmid architecture, and deepening our understanding of this high-risk clone’s emergence and potential for regional spread.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical and Geographic Distribution of ST101 Isolates

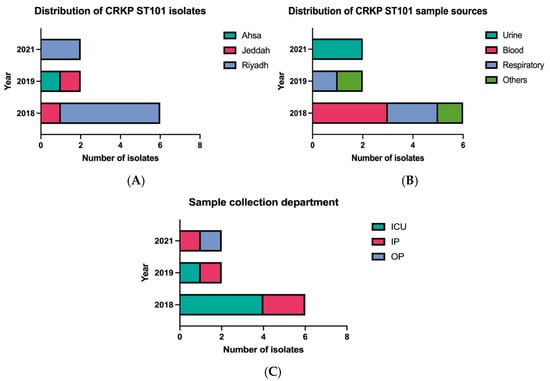

Ten CRKP clinical isolates were obtained from MNGHA hospitals in Saudi Arabia between January 2018 and December 2021, representing 4.5% of all CRKP isolates identified through the institutional AMR surveillance program. Geographic distribution showed Riyadh as the primary source (n = 7), followed by Jeddah (n = 2), and Ahsa (n = 1) (Figure 1A). The isolates originated from a range of clinical specimens, with blood and respiratory samples being the most frequent (n = 3, each), followed by urine (n = 2), and swabs from wound and rectal sites (n = 1, each) (Figure 1B). A temporal analysis revealed that the majority of isolates (n = 6) were recovered in 2018, followed by a sharp decline in 2019 and 2020 (n = 2, each year). No isolates were identified in 2021, likely due to COVID-19-related restrictions affecting surveillance activities. Nine of the ten patients were hospitalized, with a single case identified in an outpatient setting. Among the hospitalized patients, five were located in intensive care units and four were in internal medicine wards. All patients were Saudi nationals with no documented history of international travel (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Epidemiological characteristics of CRKP ST101 isolates. (A) Geographic distribution across Ahsa, Jeddah, and Riyadh (from 2018 to 2021). (B) Distribution by specimen type, including blood, respiratory samples, urine, and wound or rectal swabs. (C) Distribution by clinical setting (intensive care unit, inpatient ward, or outpatient clinic) over the study period.

2.2. Clinical Characteristics and Epidemiology of CRKP ST101 Isolates

Clinical data from patients in Riyadh and Jeddah were retrieved from the hospitals’ electronic medical records systems in compliance with ethical approval guidelines. Clinical data of one patient in Ahsa were not available. The patients’ ages ranged from 38 and 92 years. Primary admission diagnoses included respiratory infections and respiratory distress (n = 2), with other presentations detailed in Table 1. Six patients (67%) developed healthcare-associated infections during hospitalization. CRKP isolation occurred ≥48 h after admission in these cases, consistent with nosocomial acquisition. Clinical outcomes were severe. Six patients (67%) developed sepsis that progressed to septic shock and multiorgan failure, and as a result all six died during hospitalization. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus and hypertension, with complete patient profiles provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and comorbidities of patients infected with K. pneumoniae strains. This table presents detailed clinical data for patients infected with K. pneumoniae, including inpatient (IP) or outpatient (OP) status, hospital department, patient outcomes, reasons for admission, causes of death (where applicable), and presence of healthcare-associated infection (HAI) or community-acquired infection (CAI). It also documents age, comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and other chronic illnesses (e.g., chronic kidney disease, dementia, hypothyroidism). High mortality, particularly among intensive care unit (ICU) patients, underscores the severe impact of these MDR infections.

2.3. Phenotypic Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed using the VITEK II automated system with the AST-N291 card (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [25]. All isolates demonstrated resistance to multiple β-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins (ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, piperacillin/tazobactam) and cephalosporins (cefaclor, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefepime), as well as fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin) and other agents (nitrofurantoin, and trimethoprim). High but variable resistance was observed for meropenem (n = 9), amikacin (n = 7), gentamicin (n = 7), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (n = 7). Tigecycline susceptibility was retained in all isolates, representing the only universally effective agent tested. All isolates were classified as MDR, defined as resistance to agents in three or more antimicrobial categories. Five isolates (50%) were classified as XDR, with susceptibility limited to tigecycline and one or two additional agents.

2.4. Genomic Analysis of the ST101 Isolate

All isolates were identified as sequence type (ST) 101 by multilocus sequence typing (MLST), with an average genome size of 5,851,131 bp and a GC content of 56.73%. Assembly statistics revealed an average of 191 contigs per genome, with the largest contig measuring 5,598,060 bp and an average N50 value of 2,362,430 bp. Serotyping revealed a uniform capsular profile across all isolates, with K-locus KL17, O-locus O1/O2v1, and wzi-type wzi137. Plasmid content ranged from 2 to 9 per isolate, with an average of 5. Kleborate resistance scoring revealed high resistance levels: five isolates (50%) achieved the maximum score of 3 (carbapenemase plus colistin resistance), four (40%) scored 2 (carbapenemase only), and one (10%) scored 1 (ESBL only). Kleborate virulence scoring identified two predominant profiles: six isolates (60%) carried yersiniabactin only (score 1), while four (40%) harbored both aerobactin and yersiniabactin (score 4).

2.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms

The CRKP clinical isolates exhibited Kleborate resistance scores of 1–3, harboring 6 to 15 resistance genes conferring resistance to 6–10 antimicrobial classes. The isolates demonstrated resistance to most clinically relevant antimicrobials through diverse resistance mechanisms. β-lactamase genes, including blaOXA-9 and blaTEM-1, were identified in seven (n = 7). Three blaCTX-M Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) variants were identified, blaCTX-M-14 (n = 1), blaCTX-M-15 (n = 7), and blaCTX-M-27 (n = 4), with blaCTX-M-15 being most prevalent. Nine isolates (90%) harbored carbapenemase genes, including blaOXA-48 (n = 9) being most prevalent and blaNDM-1 present in three isolates (30%). Three isolates (30%) co-harbored both carbapenemases, representing dual-carbapenemase producers with enhanced resistance potential. All isolates harbored aminoglycoside resistance genes, including aph(3′), armA, aadA, aac(6′), and sat-2. One isolate harbored the fluoroquinolone resistance gene qnrS, while all the isolates harbored the mutated gyrA, and parC chromosomal genes that confer resistance against fluoroquinolone in all isolates. Additionally, six isolates harbored one or two of sulfonamides resistance genes sul1 and/or sul2, and one isolate harbored the mutated tet(D) gene conferring resistance to tetracyclines. All isolates harbored genes conferring resistance to trimethoprim, such as dfrA5, dfrA14, and dfrA1. No plasmid-mediated colistin resistance genes were detected; however, chromosomal mutations in mgrB associated with colistin resistance were identified in five isolates (50%).

2.6. Virulence Associated Genes

The CRKP isolates exhibited Kleborate virulence scores of 1 and 4, indicating variable virulence potential. Four isolates were classified as hypervirulent CRKP, harboring virulence genes iucABCD and iutA (virulence score 4). All isolates harbored the iron-scavenging siderophore yersiniabactin (ybt9), located on the integrative conjugative element ICEKp3. The presence of ybt9/ICEKp3 combination in K. pneumoniae enhances pathogenicity by linking iron-scavenging capability with resistance mechanisms, contributing to treatment challenges. Aside from plasmid-driven resistance, the detection of ICEKp3 in all isolates reinforces the role of integrative and conjugative elements as conserved genomic features in K. pneumoniae ST101 that could increase its virulence potential. The current analysis examined resistance derived from plasmids; however, the presence of ICEKp variants could also contribute to horizontal gene transfer and genomic diversification. Future long-read sequencing approaches will enable comprehensive mapping and structural validation of these elements. Importantly, four isolates harbored virulence regulators (rmpA/rmpA2) and the siderophore aerobactin (iuc), confirming hypervirulent classification. No colibactin was identified in the isolates and complete virulence gene profiles are detailed in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genomic and phenotypic characteristics of CPKP carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates from various regions in Saudi Arabia (2018–2021).

2.7. Plasmid Characterization and Resistance Gene Environments

Comprehensive plasmid profiling revealed that all isolates harbored multiple plasmids, ranging from 2 to 9 plasmids per isolate (average: 5 plasmids). Replicon typing using the PlasmidFinder database implemented in ABRicate identified diverse plasmid types, including colicinogenic plasmids (Col440, ColKP3, ColpVC, and ColRNA) and incompatibility groups (IncFIA, IncFIB, IncFII, IncHI1B, IncL/M, and IncR). The most prevalent replicon type was IncL/M, detected in 9/10 isolates (90%), followed by IncFIB and Col440 in 7/10 isolates (70% each). IncHI1B was identified in 6/10 isolates (60%), while ColRNA and IncR were present in 4/10 isolates (40% each). Less frequent replicon types included IncFIA in 2/10 isolates (20%) and IncFII in 1/10 isolates (10%).

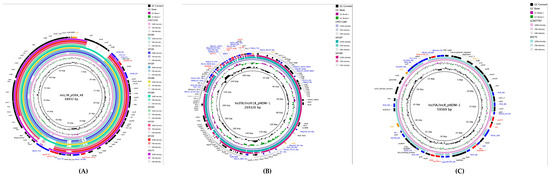

The IncL/M replicon harboring blaOXA-48 was identified in 9/10 isolates (90%) and measured 68,932 bp in length. BLAST (version 2.17.0) comparison demonstrated 100% query coverage and identity with the reference blaOXA-48 bearing plasmid IncL/M(pOXA-48)_1_pOXA-48 (Accession number: JN626286). The blaOXA-48 gene was flanked by insertion sequences IS1D and IS10A, with the complete genetic environment consisting of IS10A-IS1R-IS1D-blaOXA-48-dmIR-IS10A. An additional ESBL gene (blaCTX_M-15) was located on the same plasmid and flanked by the ISEcp1 insertion sequence, demonstrating the multi-resistance capacity of this IncL/M plasmid (Figure 2A).

A hybrid plasmid combining IncHI1B and IncFIB replicons was identified harboring blaNDM-1, with a total length of 269,326 bp. This plasmid carried multiple ARGs, including aphA, msrE, rmtB, and ant, in addition to the carbapenemase gene. The blaNDM-1 gene was flanked by ISAba125 and ISEc33 insertion sequences, embedded within a complex genetic environment consisting of IS4321R-ISStma11-Tn2-IS26-hin-ISAba125-groS-trpF-blaNDM-1-ISEc33-ISAba125-aphA-ISAba14-IS26-ISKpn26-ISKpn21-ISBcen27-msrE-ISEc29-rmtB-ISEc35-folP-emrE-ant-ISSsu9-xerC-hin-TnAs2-IS4321L. This dense clustering of ARGs within multiple mobile genetic elements characterized the complex architecture of the IncHI1B/IncFIB hybrid plasmid (Figure 2B).

A second hybrid plasmid combining IncFIA and IncR replicons was identified harboring two copies of blaNDM-1 alongside blaCTX-M-27, with a total length of 59,369 bp. BLAST comparison showed 83% query coverage and identity with a reference blaNDM-1-bearing plasmid (Accession number: LC807787). The genetic environment of the blaNDM-1 genes on this plasmid differed from that observed on the IncHI1B/IncFIB plasmid, with flanking sequences IS26 and ISCR1 and a genetic environment consisting of IS26- blaNDM-1-ble-trpF-dsbD-ISCR1. The co-located blaNDM-1 gene was flanked by IS26 and ISEcp1, with a genetic environment of IS26-Tn2-wbuC- blaCTX-M-27-ISEcp1-ISKpn14 (Figure 2C).

Mobile genetic element analysis revealed extensive IS26 distribution across the plasmids, particularly associated with resistance gene clusters. The dense presence of insertion sequences, transposons, and integrative elements surrounding ARGs demonstrated the dynamic genetic architecture facilitating horizontal gene transfer. This multi-plasmid resistance framework, encompassing three distinct replicon combinations with varying genetic environments, characterized the complex resistance dissemination mechanisms present in the ST101 isolates.

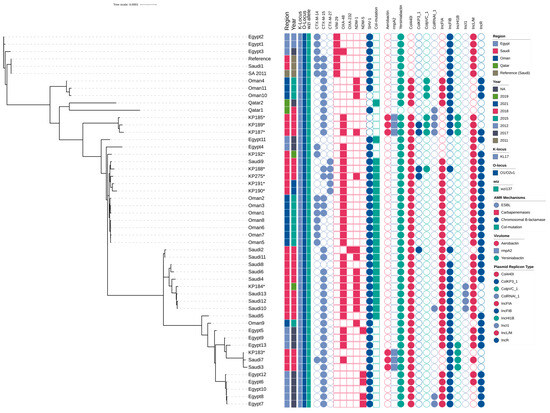

2.8. Phylogenetic Relationships of ST101 Isolates

Phylogenomic reconstruction was performed using maximum likelihood analysis implemented in IQ-TREE multicore (version 2.3.6) with automatic model selection, and the resulting tree was visualized using Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL; version 7). The phylogenetic analysis revealed minimal genetic divergence among study isolates, with short branch lengths indicating recent evolutionary relationships and potential clonal expansion within the ST101 lineage. Genomic clustering analysis identified distinct epidemiological patterns within the study population. Isolate KP183 and several related strains formed a tight cluster, demonstrating high genetic similarity consistent with recent common ancestry or ongoing transmission networks. Phylogeographic analysis revealed that Saudi Arabian isolates clustered with Egyptian ST101 strains, indicating trans-regional dissemination patterns and shared evolutionary origins within the Middle Eastern population structure. A subset of Saudi Arabian isolates formed intermediate clades with other regional isolates, suggesting established circulation of ST101 variants within the Arabian Peninsula. These relationships indicate either ancestral diversification events or multiple independent introduction events followed by local adaptation and expansion. Notably, three isolates (KP190, KP191, KP275) constituted a highly supported a tight clade with minimal internal branch lengths, indicating recent clonal expansion or potential nosocomial transmission. This clustering pattern demonstrates the utility of whole-genome sequencing for high-resolution epidemiological surveillance and outbreak investigation of CRKP clones. Comparative phylogeographic analysis revealed contrasting population structures between regional populations. Egyptian isolates exhibited limited genetic diversity with tight clustering, consistent with clonal expansion from a recent common ancestor or founder effect. In contrast, Saudi Arabian isolates displayed greater phylogenetic diversity with distribution across multiple sub-lineages, indicating more complex introduction patterns or longer-term endemic circulation within the healthcare system (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Circular comparison of carbapenemase-carrying plasmids with related reference plasmids. (A) IncL/M plasmid harboring blaOXA-48 (68,932 bp) compared with related plasmids from the literature. (B) IncHI1B/IncFIB hybrid plasmid harboring blaNDM-1 (269,326 bp) compared with related reference plasmids. (C) IncFIA/IncR hybrid plasmid harboring dual blaNDM-1 genes (59,369 bp) compared with related reference plasmids. ARGs are highlighted in red, insertion sequences in blue, and other genetic elements are color-coded according to the legend.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic Analysis and Resistance Profile of ST101 Isolates. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on core genome single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of K. pneumoniae isolates from Saudi Arabia and neighboring Gulf countries. Isolates from this study are indicated with asterisks (*). The adjacent heatmap displays the presence or absence of acquired extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL), carbapenemases, chromosomal β-lactamases, and chromosomal colistin resistance mutations (mgrB).

3. Discussion

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains represent a critical global public health threat through their capacity for rapid horizontal dissemination of resistance determinants, resulting in difficult-to-treat infections with increased mortality rates and adverse clinical outcomes across healthcare systems worldwide [26]. Recent European surveillance studies have identified K. pneumoniae ST101 as an emerging high-risk clone characterized by widespread dissemination of carbapenem and colistin resistance mechanisms, accompanied by elevated morbidity and mortality rates [21,22,27,28]. In Saudi Arabia, K. pneumoniae ST101 has been recognized as one of the predominant MDR clones driving regional resistance dissemination [24]. This investigation presents comprehensive findings from a four-year CRKP surveillance program conducted at MNGHA hospitals throughout Saudi Arabia, during which ST101 emerged as one of the predominant circulating clones. Our analysis encompasses detailed clinical epidemiology alongside comprehensive phenotypic and genotypic characterization of collected isolates, with particular emphasis on plasmid architecture and mobile genetic element analysis. Furthermore, this study elucidates critical molecular mechanisms underlying resistance gene acquisition and dissemination within the ST101 clone of CRKP circulating throughout Saudi Arabian healthcare networks. While our analysis focused on ten ST101 isolates, which may not fully capture the complete genetic diversity of this lineage across the country, these findings provide essential insights into regional resistance patterns. Therefore, results should be interpreted within this context while recognizing their significant contribution to understanding ST101 epidemiology in the Middle Eastern region.

As part of a comprehensive surveillance initiative, CRKP ST101 isolates were recovered from patients across three major regions in Saudi Arabia Riyadh, Jeddah, and Al-Ahsa enabling comparative genomic analysis across distinct healthcare settings and geographic distributions. The temporal distribution revealed that the majority of isolates were collected during 2018, with no isolates obtained in 2021, likely reflecting reduced clinical sampling and operational constraints associated with COVID-19 pandemic disruptions. Clinical epidemiological analysis demonstrated that over 80% of isolates were obtained from hospitalized patients, indicating that CRKP ST101 infections are predominantly hospital-acquired rather than community-acquired [29]. This nosocomial predominance was further reinforced by the observation that all ten ST101 isolates analyzed were recovered from inpatient settings, emphasizing the healthcare-associated transmission patterns characteristic of this high-risk clone. Patient demographics revealed significant underlying comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which represent established risk factors for adverse outcomes in MDR bacterial infections. Clinical presentations included multiple patients admitted with critical conditions, and comprehensive infection classification identified all cases as healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), with no community-acquired infections documented throughout the surveillance period. Although clinical outcome data availability was limited, a substantial proportion of patients experienced severe adverse outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, with infection-related deaths documented in multiple cases. These clinical findings align with previous investigations reporting elevated morbidity and mortality rates associated with CRKP infections, particularly among vulnerable patient populations with underlying chronic disease conditions [21,27].

Comprehensive phenotypic susceptibility testing revealed extensive multidrug resistance across multiple antibiotic classes, including β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, and sulfonamides, reflecting the complex resistance architecture harbored by these ST101 isolates. This broad resistance profile substantially constrained available therapeutic options, with susceptibility retained primarily to colistin, tigecycline, and, in select cases, aminoglycosides, thereby limiting clinicians to last-resort antimicrobial agents. The therapeutic implications of this resistance pattern present significant clinical challenges, as CRKP ST101 infections often necessitate the use of last-resort antimicrobials associated with considerable toxicity profiles and variable clinical efficacy. Although plasmid-mediated colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae ST101 strains has been increasingly documented in global surveillance studies [27], none of our isolates carried plasmid-borne mcr genes. Instead, colistin resistance mechanisms in our cohort were attributed to chromosomal mutations within the mgrB regulatory gene, which was detected in (n = 5, 50%) of the analyzed isolates. This chromosomal resistance pattern demonstrates the critical role of mutation-driven mechanisms in mediating colistin resistance among CRKP within our healthcare setting.

Furthermore, these findings underscore the critical importance of differentiating plasmid-mediated from chromosomally encoded resistance when shaping antimicrobial-resistance surveillance frameworks and infection-control policies. The genomic context of resistance genes fundamentally determines their epidemiological behavior. Plasmid-borne determinants can disseminate rapidly across bacterial lineages and species through conjugative transfer, fueling interhospital and interregional outbreaks. In contrast, chromosomal integration of resistance genes ensures vertical inheritance and long-term stability within successful clonal lineages, often with a reduced fitness burden. These distinct evolutionary pathways profoundly influence diagnostic interpretation and containment strategies: plasmid-encoded ARGs signal active horizontal-gene-transfer events, whereas chromosomal integration represents entrenched resistance within established clones. Recognizing this dichotomy is essential for anticipating transmission dynamics and for designing precision genomic-surveillance systems that effectively mitigate the regional and global spread of AMR [30,31].

Comprehensive phenotypic-genotypic correlation analysis revealed that all carbapenemase-producing isolates were accurately identified through phenotypic susceptibility testing, demonstrating complete concordance with molecular detection methods and validating the reliability of laboratory diagnostic approaches. However, one isolate exhibited a carbapenem-resistant phenotype despite the absence of detectable carbapenemase-encoding genes, representing an important diagnostic consideration for clinical laboratories. This phenomenon is well-documented in the literature and typically results from alternative resistance mechanisms, including overexpression of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in combination with compromised outer membrane permeability [32,33]. Consistent with this established mechanism, molecular characterization revealed that the isolate harbored the blaCTX-M-15 gene alongside disruptive mutations in the ompK35 and ompK36 porin genes, which represent likely contributors to the observed carbapenem-resistant phenotype [34,35]. This finding emphasizes the complexity of carbapenem resistance mechanisms and highlights the importance of comprehensive molecular characterization for accurate resistance profiling, particularly in isolates where phenotypic and genotypic results appear discordant.

Comprehensive molecular epidemiological analysis revealed the regional complexity and dissemination patterns of CRKP ST101 lineages across Middle Eastern healthcare networks. Notably, two isolates within our study population harbored both blaCTX-M-15 and blaCTX-M-27 ESBL genes, representing a rare co-occurrence that suggests active plasmid-mediated genetic exchange and the emergence of highly resistant sub-lineages with enhanced therapeutic evasion potential. This dual ESBL gene acquisition pattern raises significant concerns regarding local adaptation mechanisms and the evolution of increasingly complex resistance architectures. Comparative genomic analysis utilizing the Pathogenwatch database demonstrated that our ST101 isolates exhibit close phylogenetic relationships with other strains circulating throughout the Middle Eastern region, indicating established regional clonal dissemination networks. These phylogenetically related clones demonstrate similar resistance patterns despite considerable variation in their plasmid content profiles, reflecting the dynamic acquisition and loss of plasmid-mediated resistance determinants within regional healthcare systems. Furthermore, several Egyptian isolates clustered closely with Saudi Arabian strains, particularly those harboring blaNDM-5, suggesting potential epidemiological linkages or shared regional selective pressures driving resistance evolution. The presence of NDM-5-producing strains in Egypt, a carbapenemase gene frequently associated with high-level carbapenem resistance and enhanced plasmid mobility, reflects broader regional resistance dynamics that may significantly influence future dissemination patterns across Middle Eastern healthcare settings [36,37].

K. pneumoniae ST101 is globally recognized as a high-risk clone strongly associated with the dissemination of blaOXA-48 carbapenemase genes across healthcare systems worldwide [21,38,39,40]. According to comprehensive surveillance conducted in Europe, the same high-risk lineages identified during 2013-14 (EuSCAPE) continued to circulate across European hospitals in 2019, including ST11, ST15, ST101, and ST258/512. Moreover, concerning epidemiological shifts in pathogen populations were observed, including increased acquisition of carbapenemase genes by MDR lineages such as ST147, ST307, and ST39 [28]. Consistent with our findings, recent surveillance studies from Saudi Arabia have similarly identified ST101 as one of the predominant circulating clones harboring blaOXA-48 carbapenemase genes [24,41]. In our cohort, 20% of CRKP ST101 isolates co-harbored blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 genes, indicating the emergence of dual-carbapenemase producers with enhanced resistance potential. The identification of co-producing blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 carbapenemase genes underscores the critical need for early molecular diagnostics to guide optimal antibiotic selection and prevent inappropriate empiric therapy. A parallel study from Spain similarly reported co-presence of blaNDM-1, blaOXA-48 and blaCTX-M-15 genes in ST101 clinical isolates, supporting the hypothesis that globally circulating high-risk clones with complex resistance architectures are increasingly present within our region [42]. These findings demonstrate the evolving complexity of resistance mechanisms in high-risk clones and underscore the urgent need for sustained genomic surveillance and targeted infection control measures. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying plasmid-mediated resistance can directly support antimicrobial-stewardship initiatives aimed at minimizing unnecessary carbapenem use and preserving the efficacy of remaining last-line treatment options, including tigecycline and colistin. These findings demonstrate how genomic data can inform evidence-based prescribing and strengthen infection-control practices within healthcare systems facing the growing challenge of CRKP.

Our genomic analysis revealed that blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 genes were located on distinct plasmid systems, suggesting independent acquisition events and potential for differential horizontal transfer. However, we acknowledge that conjugation or transformation assays were not performed to experimentally validate their mobility potential. Future investigations incorporating conjugation experiments are warranted to confirm the horizontal transfer capacity of these resistance determinants and their epidemiological significance. This genomic investigation establishes one of the first comprehensive molecular epidemiology datasets of CRKP ST101 in Saudi Arabia, offering crucial insight into the evolutionary mechanisms driving the persistence of this globally disseminated high-risk clone. The concurrent presence of blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 carbapenemase genes on IncL/M-type plasmids, together with virulence-associated elements such as ICEKp3, indicates an adaptive genomic process that strengthens bacterial fitness and survival under antimicrobial pressure. These findings not only underscore the regional emergence of MDR K. pneumoniae lineages but also contribute essential data to global AMR surveillance efforts from a region where genomic information remains limited. Plasmid and resistance gene structures were inferred from short-read Illumina assemblies, which may not fully resolve repetitive genomic regions; future work integrating long-read sequencing (PacBio or Oxford Nanopore technologies) will enable high-resolution mapping of mobile genetic elements and refine our understanding of resistance evolution in ST101. Importantly, this work supports the ongoing national efforts in Saudi Arabia to strengthen genomic surveillance and early detection of AMR, reinforcing the Kingdom’s contribution to global AMR preparedness and One Health initiatives.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Hospital Setting and Study Design

This retrospective cross-sectional study was part of the AMR Surveillance Program initiated by the MNGHA in Saudi Arabia in 2018, led by the Infectious Disease Research Department (IDRD) at King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre (KAIMRC). The MNGHA operates a network of hospitals and specialized medical centers located in various regions, including Riyadh, Jeddah, Al-Ahsa, Dammam, and Medina, under the Ministry of National Guard and the Saudi Arabian National Guard. These facilities, with a capacity of over 3000 beds, primarily serve National Guard employees and their families, offering care from primary health services to advanced tertiary care. All K. pneumoniae isolates and their VITEK reports were collected from MNGHA hospital microbiology laboratories across the country and sent to the IDRD at KAIMRC. There, species identification and the presence of ARGs were confirmed through multiplex PCR. Isolates that met the selection criteria were further analyzed using whole-genome sequencing and advanced bioinformatics tools for deeper genetic insights.

4.2. Bacterial Isolates and Phenotypic Testing

Between January 2018 and December 2021, a total of ten CRKP clinical isolates were gathered from various clinical sources, like blood, urine, respiratory samples, wound tips, tissue, and other clinical types. These strains were sent by MNGHA hospital microbiology labs throughout Saudi Arabia. The isolates were first identified using the VITEK II automated system (BioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) and then further validated through multiplex PCR. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the Gram-negative bacteria card on the VITEK II system. These CRKP isolates were further examined to identify resistance mechanisms, virulence factors, and the associated mobile genetic elements through molecular characterization. All clinical data was pulled from the MNGHA clinical system. Data collection and research was authorized by the Ethics Committee of KAIMRC.

4.3. Bacterial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing for CRKP isolates was done on 16 antibiotic agents, which included ampicillin (AMP), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC), piperacillin/tazobactam (PTZ), cefaclor (CEF), cefoxitin (FOX), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftriaxone (CRO), cefepime (FEB), imipenem (IMP), meropenem (MEM), amikacin (AMK), gentamicin (GEN), ciprofloxacin (CIP), tigecycline (TGC), nitrofurantoin (NIT), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX). These were tested using the VITEK II automated system (BioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) along with the (AST-N291) GN identification card. The interpretation of results was done according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations [25].

4.4. Genotypic Screening of Carbapenemases

All K. pneumoniae isolates with reduced carbapenem susceptibility were screened for carbapenemase genes (blaOXA-48, blaNDM, blaKPC, blaIMP, and blaVIM) using a Multiplex-PCR assay [9]. The assay was optimized for specificity, and results were validated with control strains. Gel electrophoresis confirmed the presence of the targeted resistance genes. the primers used for this essay are listed in (Table 3).

Table 3.

Primers sequences of carbapenemase genes used in Multiplex-PCR assay.

4.5. Whole Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

Each K. pneumoniae isolate was obtained from a single colony sub-cultured from the primary clinical specimen to ensure clonal purity. High-quality genomic DNA was extracted and sequenced from this purified colony to confirm genomic uniformity and avoid sequencing a heterogeneous population. DNA quality and concentration were assessed using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sequencing libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol and subjected to paired-end whole-genome sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq® platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The quality of the raw sequencing data was checked with FastQC “https://github.com/s-andrews/FastQC, (accessed on 15 April 2023)”, and de novo assembly of high-quality reads was performed using SPAdes (version 1.0.9) “https://github.com/ablab/spades (accessed on 15 March 2023)” [43]. Assembly quality assessment and stats like genome size, GC content, and N50 were identified using QUAST software (version 5.3.0) “https://github.com/ablab/quast (accessed on 23 April 2025)”. Then, the genomic sequences were characterized and annotated using advanced bioinformatics pipelines. Sequence types were determined using MLST (version 2.9) “https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (accessed on 24 April 2025)” [44], while ARGs, virulence-associated genes, and plasmid replicon typing were identified by ABRicate (version 0.5) “https://github.com/tseemann/abricate (accessed on 24 April 2025)” using the pre-downloaded ResFinder [45], VFDB [46], and PlasmidFinder databases [47], respectively. Sequence types, ARGs, virulence factor genes, resistance and virulence scores, and capsule serotype (K) and O antigen (LPS) serotype predictions were validated using Kleborate (version 2.3.2) “https://github.com/klebgenomics/Kleborate/tree/main (accessed on 26 April 2025)” [48].

4.6. Plasmid Characterization

The annotation for ARGs, virulence factors, and mobile genetic elements was performed using Prokka (version 1.13) and Artemis Software (version 18.2.0) [49,50,51,52,53]. Mauve software (version 2.4.0) was used for assembly quality assessment and for aligning genomic and open reading frame sequences using K. pneumoniae strain KP4823, complete genome (accession numbers: CP082791.1-CP082795.1) as a reference; BRIG (version 0.95) software was used to generate plasmid circle figures [54]. The complete genome of characterized plasmid replicon types were used as a reference (IncL/M: accession number: CP071281.1); (IncHI1B/IncFIB: accession number: CP071280.1); and (IncFIA/IncR: accession number: LC807787) [55,56].

4.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

All K. pneumoniae ST101 strains isolated in Saudi Arabia were retrieved from Pathogenwatch genome database. The whole genome of K. pneumoniae (accession number: SAMD00055765) was obtained from the Pathogenwatch genome database to be used as a reference. All K. pneumoniae ST101 sequences from Middle Eastern countries available in the Pathogenwatch genome database were retrieved and incorporated into the phylogenetic analysis. The accession numbers and associated metadata for these sequences are provided in the supplementary file Table S1. Phylogenetic analysis of the isolates was conducted by identifying single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using Snippy (version 4.6.0) “https://github.com/tseemann/snippy, (accessed on 9 May 2025)”. To ensure precise reconstruction of evolutionary relationships under realistic short-term bacterial evolution models, Gubbins (version 3.3.5) “https://github.com/nickjcroucher/gubbins, (accessed on 10 May 2025)” was employed [57]. The output from Gubbins was subsequently used to construct the phylogenetic tree with IQ-TREE (version 2.3.6) “https://github.com/iqtree/iqtree2, (accessed on 11 May 2025)” [58,59]. A treefile that was generated by IQ-TREE was annotated and visualized in the interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) (version 7.0) “https://itol.embl.de, (accessed on 16 May 2025)”.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Microsoft Excel was used for the quantitative analysis of the collected data and GraphPad Prism (version 10.2.3) (347) was used in creating the graphs and figures.

5. Conclusions

This investigation reveals K. pneumoniae ST101 as an evolutionary paradigm shift in AMR, representing the emergence of a “super-pathogen” that fundamentally threatens the foundation of modern medicine. Our comprehensive genomic architecture analysis demonstrates the unprecedented convergence of dual carbapenemases (blaOXA-48/blaNDM-1) with multiple extended-spectrum β-lactamases (blaCTX-M-15/blaCTX-M-27) within sophisticated multi-plasmid resistance platforms, creating an essentially pan-resistant phenotype that renders the entire antimicrobial armamentarium ineffective.

These findings represent a watershed moment in the global AMR crisis, marking the transition from treatable MDR infections to virtually untreatable pan-resistant pathogens. The complex molecular architecture we have elucidated, encompassing three distinct plasmid systems (IncL/M, IncHI1B/IncFIB, IncFIA/IncR) with extensive mobile genetic element landscapes, establishes a highly efficient horizontal gene transfer network capable of rapidly disseminating this resistance constellation across bacterial populations worldwide. The strategic emergence of these isolates within Saudi Arabia, positioned at the crossroads of global healthcare networks, amplifies their pandemic potential and represents an immediate existential threat to international health security.

Our molecular epidemiological analysis provides the critical foundation for paradigm-shifting public health interventions. The genomic signatures and resistance architectures we have characterized enable the development of next-generation rapid diagnostics, precision surveillance systems, and targeted containment strategies, which are essential for preventing global dissemination of this emerging super-pathogen. This work establishes K. pneumoniae ST101 as the highest priority target for enhanced global genomic surveillance and underscores the critical urgency for revolutionary therapeutic approaches, including novel antimicrobial classes and alternative treatment modalities, to combat what may represent the vanguard of a post-antibiotic era.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262311518/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.A. and E.K.I.; methodology, E.K.I., A.A.A., E.T.A., A.S.A., L.O., S.M.A.J. and M.F.A.; software, A.A.A. and E.K.I.; validation, E.K.I., M.G.A., N.A. and M.F.A.; formal analysis (including bioinformatics), E.K.I., A.A.A. and M.F.A.; investigation, E.K.I., L.O., E.T.A. and A.S.A.; resources, S.M.A.J., H.H.B., M.F.A. and MNGHA Surveillance Group; data curation, E.K.I.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K.I. and M.F.A.; writing—review and editing, E.K.I., M.M.A., M.G.A., N.A., H.H.B. and M.F.A.; visualization, E.K.I. and M.F.A.; supervision, M.G.A., M.M.A. and M.F.A.; project administration, H.H.B. and M.F.A.; funding acquisition, M.G.A. and M.F.A.; ethical approval, M.G.A. and M.F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, through project approval number NRC23R/240/04.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (approval number NRC23R/240/04) on 19 June 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or identifiable human data. Only de-identified, basic clinical metadata associated with bacterial isolates were analyzed under institutional ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

The whole-genome sequences of the chromosome and plasmids of K. pneumoniae ST101 isolates generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1192313. Individual genome accessions are available under SAMN50015027–SAMN50015036.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs (MNGHA) hospitals in Saudi Arabia for their support in the collection of clinical isolates. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the MNGHA Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Surveillance Group, including Majed F. Alghoribi, Liliane Okdah, Eisa T. Alrashidi, Alhanouf S. Alshahrani, Maha Alzayer, Abdulrahman A. Alghamdi, Maymunah A. Hakami, Abdulrahman A. Alswaji, Sameera M. Aljohani, Bassam Alalwan, Abdulfattah Al-Amri, Mai M. Kaaki, Mohamed Doud, Haitham S. Dadah, Fahad Alnashmy, Michel Doumith and Hanan H. Balkhy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Candan, E.D.; Aksöz, N. Klebsiella pneumoniae: Characteristics of carbapenem resistance and virulence factors. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2015, 62, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo, N.; Taglietti, F.; Granata, G. Treatment options for colistin resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Present and future. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Santiago, J.; Cornejo-Juárez, P.; Silva-Sánchez, J.; Garza-Ramos, U. Polymyxin resistance in Enterobacterales: Overview and epidemiology in the Americas. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Pan, F.; Wang, C.; Zhao, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H. Molecular epidemiology of Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a paediatric hospital in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al Fadhli, A.H.; Mouftah, S.F.; Jamal, W.Y.; Rotimi, V.O.; Ghazawi, A. Cracking the Code: Unveiling the Diversity of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Clones in the Arabian Peninsula through Genomic Surveillance. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isler, B.; Özer, B.; Çınar, G.; Aslan, A.T.; Vatansever, C.; Falconer, C.; Dolapçı, I.; Şimşek, F.; Tülek, N.; Demirkaya, H.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of carbapenemase harbouring carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella spp. bloodstream infections: A multicentre prospective cohort study in an OXA-48 endemic setting. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Peirano, G.; Kock, M.M.; Strydom, K.A.; Matsumura, Y. The Global Ascendency of OXA-48-Type Carbapenemases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00102-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuvillier, V.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Price, L.S.; Poirel, L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Schwaber, M.J.; Daikos, G.L.; Cormican, M.; Cornaglia, G.; Garau, J.; Gniadkowski, M.; Hayden, M.K.; et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L.; Dortet, L. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1503–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgincar, N.; Iyer, S.; Stacey, A.; Maharjan, S.; Pike, R.; Perry, C.; Wyeth, J.; Woodford, N. Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC carbapenemase in a district general hospital in the UK. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 78, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Agamy, M.H.; Shibl, A.M.; Elkhizzi, N.A.; Meunier, D.; Turton, J.F.; Livermore, D.M. Persistence of Klebsiella pneumoniae clones with OXA-48 or NDM carbapenemases causing bacteraemias in a Riyadh hospital. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 76, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammad, S.; Khazani Asforooshani, M.; Malek Mohammadi, Y.; Sholeh, M.; Badmasti, F. Decoding the genetic structure of conjugative plasmids in international clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: A deep dive into blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48, and blaGES genes. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.W.; Quyen, T.L.T.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wu, L.T.; Pan, Y.J. Investigation of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan revealed strains co-harbouring bla(NDM) and bla(OXA-48-like) and a novel plasmid co-carrying bla(NDM-1) and bla(OXA-181). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 62, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solgi, H.; Nematzadeh, S.; Giske, C.G.; Badmasti, F.; Westerlund, F.; Lin, Y.-L.; Goyal, G.; Nikbin, V.S.; Nemati, A.H.; Shahcheraghi, F. Molecular epidemiology of OXA-48 and NDM-1 producing Enterobacterales species at a University Hospital in Tehran, Iran, between 2015 and 2016. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülmez, D.; Woodford, N.; Palepou, M.-F.I.; Mushtaq, S.; Metan, G.; Yakupogullari, Y.; Kocagoz, S.; Uzun, O.; Hascelik, G.; Livermore, D.M. Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Turkey with OXA-48-like carbapenemases and outer membrane protein loss. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 31, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautzenberg, M.; Ossewaarde, J.; De Kraker, M.; Van Der Zee, A.; Van Burgh, S.; De Greeff, S.; A Bijlmer, H.; Grundmann, H.; Stuart, J.W.C.; Fluit, A.C.; et al. Successful control of a hospital-wide outbreak of OXA-48 producing Enterobacteriaceae in the Netherlands, 2009 to 2011. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, A.; Haenni, M.; Bouallègue, O.; Saras, E.; Chatre, P.; Chaouch, C.; Boujâafar, N.; Mansour, W.; Madec, J.-Y. Dynamics and molecular features of OXA-48-like-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae lineages in a Tunisian hospital. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 20, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koster, S.; Rodriguez Ruiz, J.P.; Rajakani, S.G.; Lammens, C.; Glupczynski, Y.; Goossens, H.; Xavier, B.B. Diversity in the characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 of human, environmental, and animal origin. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 838207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, C.C.; Vazquez, A.J.; Esposito, E.P.; Zarrilli, R.; Sahl, J.W. Diversity, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in isolates from the newly emerging Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 lineage. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loconsole, D.; Accogli, M.; De Robertis, A.L.; Capozzi, L.; Bianco, A.; Morea, A.; Mallamaci, R.; Quarto, M.; Parisi, A.; Chironna, M. Emerging high-risk ST101 and ST307 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clones from bloodstream infections in Southern Italy. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubero, M.; Cuervo, G.; Dominguez, M.Á.; Tubau, F.; Martí, S.; Sevillano, E.; Gallego, L.; Ayats, J.; Peña, C.; Pujol, M.; et al. Carbapenem-resistant and carbapenem-susceptible isogenic isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 causing infection in a tertiary hospital. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Alhejaili, A.Y.; Alkherd, U.H.; Milner, M.; Zhou, G.; Alzahrani, D.; Banzhaf, M.; Alzaidi, A.A.; Rajeh, A.A.; Al-Otaiby, M.A.; et al. The dissemination of multidrug-resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clones across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2427793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann, P.; Dortet, L.; Poirel, L. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: Here is the storm! Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, F.; Menekse, S.; Ispir, P.; Atac, N.; Albayrak, O.; Demir, T.; Karaaslan, D.C.; Karahan, S.N.; Kapmaz, M.; Azap, O.K.; et al. Impact of the ST101 clone on fatality among patients with colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröding, I.; David, S.; Yeats, C.; Abu-Dahab, K.; Albiger, B.; Alikhan, N.-F.; Alm, E.; Byfors, S.; Couto, N.; Diaz Caballero, J.; et al. Persistent Spread of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Acute Care Hospitals in 36 European Countries: Results from the Survey of Carbapenem-and/or Colistin-Resistant Enterobacterales (CCRE Survey). 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5275521 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Kang, C.-I.; Kim, S.-H.; Bang, J.-W.; Kim, H.-B.; Kim, N.-J.; Kim, E.-C.; Oh, M.D.; Choe, K.W. Community-acquired versus nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: Clinical features, treatment outcomes, and clinical implication of antimicrobial resistance. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2006, 21, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolen, J.P.M.; den Drijver, E.P.M.; Kluytmans, J.; Verweij, J.J.; Lamberts, B.A.; Soer, J.; Verhulst, C.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Kolwijck, E. Development of an algorithm to discriminate between plasmid- and chromosomal-mediated AmpC β-lactamase production in Escherichia coli by elaborate phenotypic and genotypic characterization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3481–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.T.; Lewin, C.S. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance and implications for epidemiology. Vet. Microbiol. 1993, 35, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-F.; Chuang, C.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chan, Y.-J.; Lin, J.-C.; Lu, P.-L.; Huang, C.-T.; Wang, J.-T.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Siu, L.K.; et al. Treatment outcome of non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: A multicenter study in Taiwan. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, I.; Puzari, M.; Chetia, P. Porin-Mediated Carbapenem Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: An Alarming Threat to Global Health. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2023, 10, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Santiago, J.; Alvarado-Delgado, A.; Rodríguez-Medina, N.; Garza-González, E.; Tellez-Sosa, J.; Duarte-Zambrano, L.; Nava-Domínguez, N.; Sohlenkamp, C.; Vences-Guzmán, M.A.; López-Jácome, L.E.; et al. Colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae species complex: The scenario in Mexico. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 43, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, C.; Butera, O.; Proia, A.; Rigacci, L.; Mariani, B.; Parisi, G.; Messina, F.; Capone, A.; Nisii, C.; Di Caro, A. Reduced susceptibility to carbapenems in a Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolate producing SCO-1 and CTX-M-15 β-lactamases together with OmpK35 and OmpK36 Porin deficiency. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00556-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón, S.; Salem-Bango, Z.; Contreras, D.A.; Ranson, E.L.; Yang, S. Clinical and Genomic Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Concurrent Production of NDM and OXA-48-like Carbapenemases in Southern California, 2016–2022. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, K. Molecular Diversity of NDM-1, NDM-5, NDM-6, and NDM-7 Variants of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamases and Their Impact on Drug Resistance. Clin. Lab. 2021, 67, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElMahallawy, H.; Zafer, M.M.; Al-Agamy, M.; Amin, M.A.; Mersal, M.M.; Booq, R.Y.; Alyamani, E.; Radwan, S. Dissemination of ST101 blaOXA-48 producing Klebsiella pneumoniae at tertiary care setting. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 12, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miro, E.; Rossen, J.W.A.; Chlebowicz, M.A.; Harmsen, D.; Brisse, S.; Passet, V.; Navarro, F.; Friedrich, A.W.; García-Cobos, S. Core/Whole Genome Multilocus Sequence Typing and Core Genome SNP-Based Typing of OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates From Spain. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcade, G.; Brisse, S.; Bialek, S.; Marcon, E.; Leflon-Guibout, V.; Passet, V.; Moreau, R.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.-H. The emergence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae of international clones ST13, ST16, ST35, ST48 and ST101 in a teaching hospital in the Paris region. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013, 141, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hala, S.; Malaikah, M.; Huang, J.; Bahitham, W.; Fallatah, O.; Zakri, S.; Antony, C.P.; Alshehri, M.; Ghazzali, R.N.; Ben-Rached, F.; et al. The emergence of highly resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae CC14 clone in a tertiary hospital over 8 years. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, B.; Salvador, C.; Tormo, N.; García-González, N.; Gimeno, C.; González-Candelas, F. Molecular epidemiology and drug-resistance mechanisms in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in patients from a tertiary hospital in Valencia, Spain. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C.J. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D694–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Y. A global perspective on the convergence of hypervirulence and carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 25, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berriman, M.; Rutherford, K. Viewing and annotating sequence data with Artemis. Brief. Bioinform. 2003, 4, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, T.; Berriman, M.; Tivey, A.; Patel, C.; Böhme, U.; Barrell, B.G.; Parkhill, J.; Rajandream, M.-A. Artemis and ACT: Viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2672–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, T.; Harris, S.R.; Berriman, M.; Parkhill, J.; McQuillan, J.A. Artemis: An integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics 2011, 28, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, K.; Parkhill, J.; Crook, J.; Horsnell, T.; Rice, P.; Rajandream, M.A.; Barrell, B. Artemis: Sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 944–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhan, N.-F.; Petty, N.K.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Beatson, S.A. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghoribi, M.F.; Alqurashi, M.; Okdah, L.; Alalwan, B.; AlHebaishi, Y.S.; Almalki, A.; Alzayer, M.A.; Alswaji, A.A.; Doumith, M.; Barry, M. Successful treatment of infective endocarditis due to pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, T.T.; Sugawara, Y.; Hamaguchi, S.; Takeuchi, D.; Abe, R.; Kuroda, E.; Morita, M.; Zuo, H.; Ueda, A.; Nishi, I.; et al. Genomic characterization of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales from Dhaka food markets unveils the spread of high-risk antimicrobial-resistant clones and plasmids co-carrying blaNDM and mcr-1.1. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, N.J.; Page, A.J.; Connor, T.R.; Delaney, A.J.; Keane, J.A.; Bentley, S.D.; Parkhill, J.; Harris, S.R. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 43, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534, Erratum in Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).