Advances in Cytotoxicity Testing: From In Vitro Assays to In Silico Models

Abstract

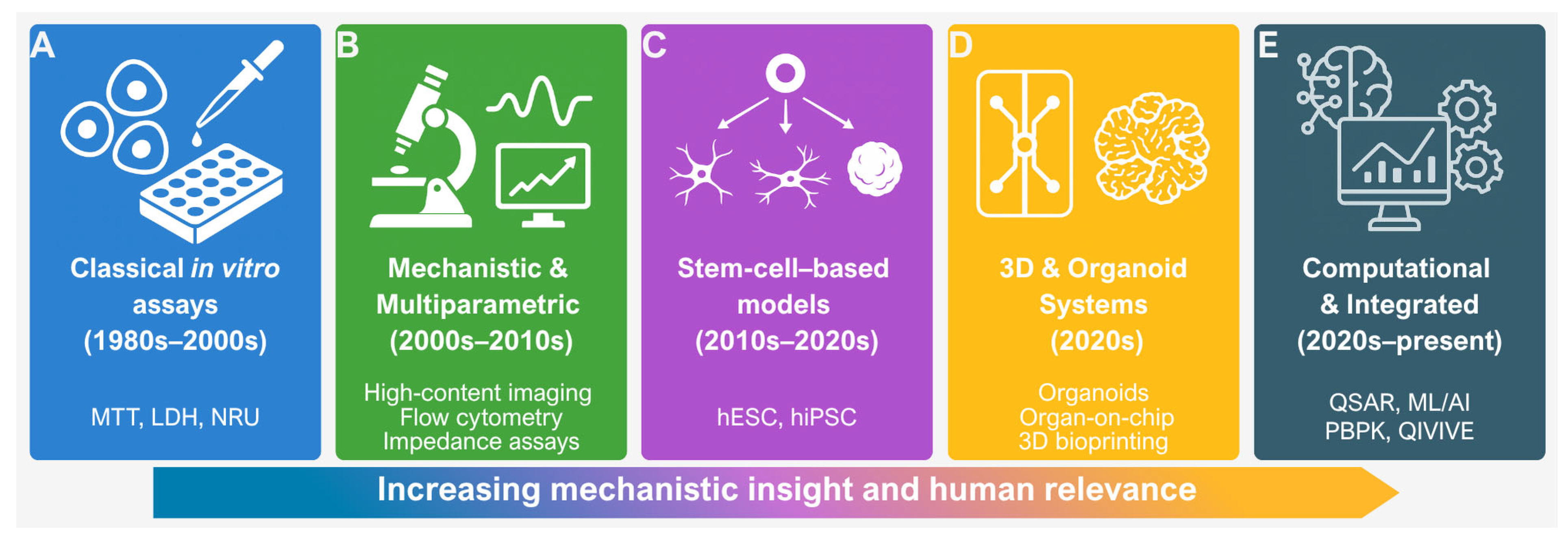

1. Introduction

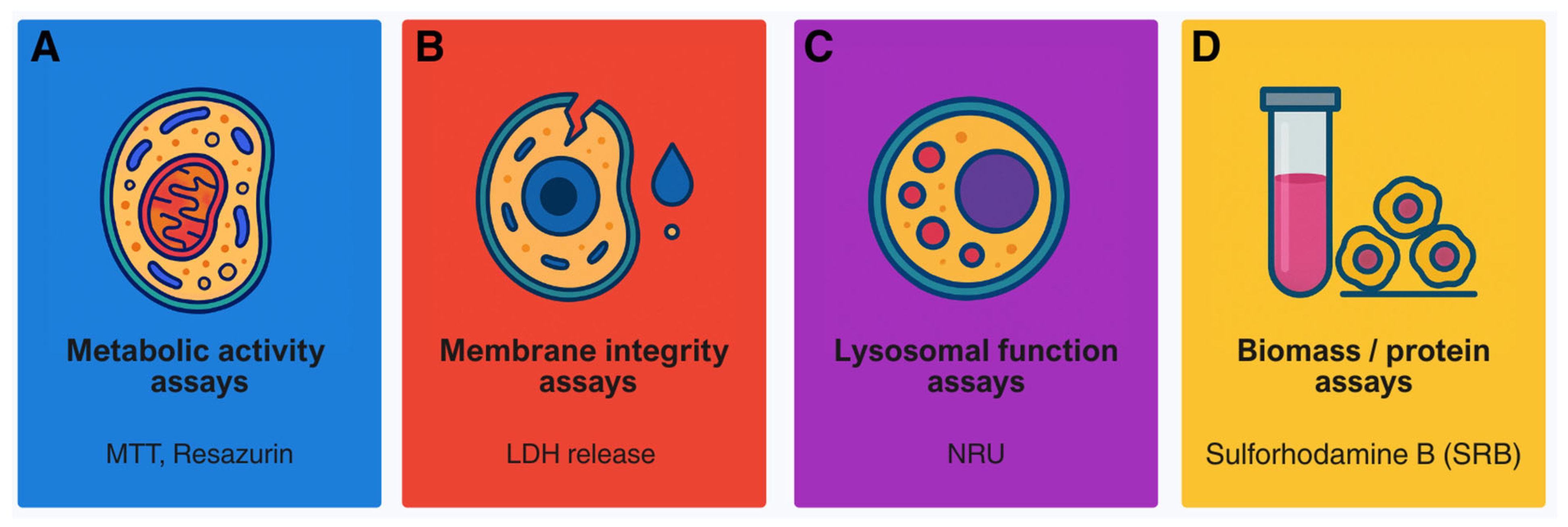

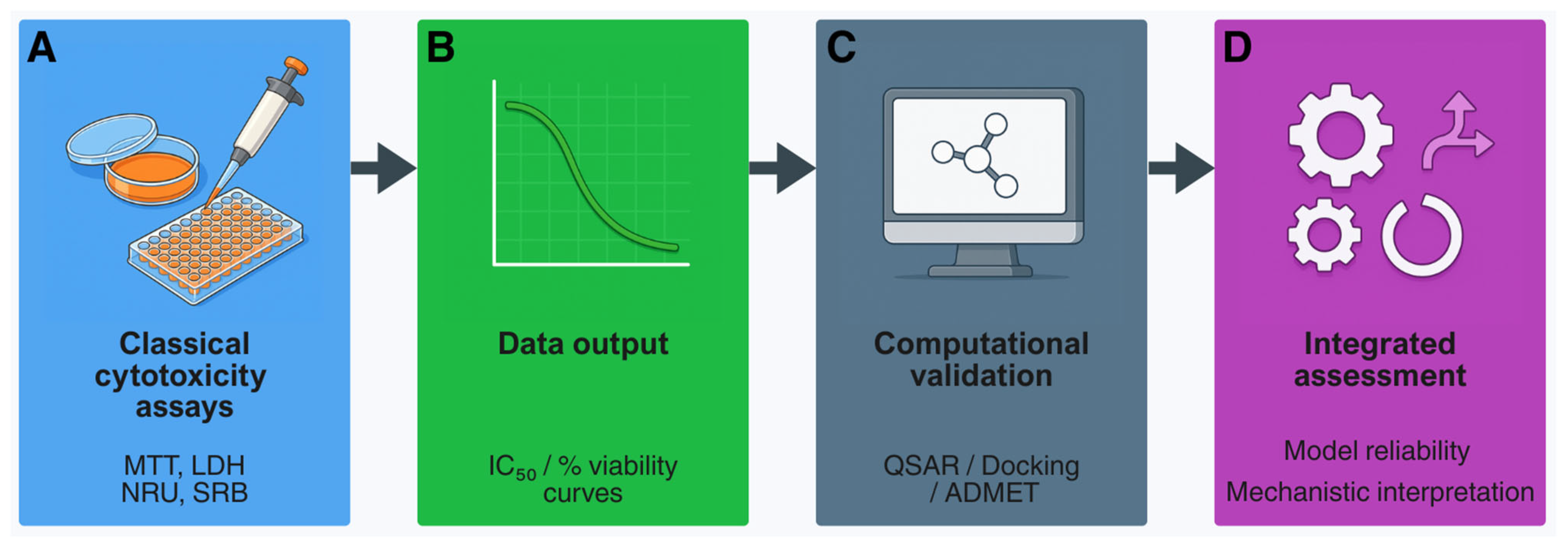

2. Classical Cytotoxicity Assays: Foundations of In Vitro Toxicology

- Verify signal linearity with cell density (5 × 103–2 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates);

- Optimise dye incubation times (e.g., 2–4 h MTT; 3 h NRU) and report conditions;

- Control for LDH background in serum; use serum-free or heat-inactivated controls.

- Screen test compounds for intrinsic fluorescence or colour; include “no-cell” blanks;

- Assess dye adsorption by nanomaterials and confirm with independent endpoints;

- Use appropriate positive and negative controls (e.g., Triton X-100, staurosporine) to verify responsiveness.

- Subtract background from blank wells;

- Normalise viability to untreated controls (100%) and maximal lysis (0%);

- Report raw data, at least three biological replicates with technical triplicates, and variability metrics.

- Specify seeding density, passage number, medium composition, incubation time, dye concentration, and detection settings;

- Describe curve fitting and statistical methods clearly;

- Note any deviations from OECD or ISO guidelines.

- MTT: non-specific reduction by compounds or medium; insoluble formazan crystals; metabolic stimulation mistaken for viability [42];

- NRU: dependence on pH or lysosomal health; false cytotoxicity when lysosomes are targeted [45];

- Resazurin: over-reduction in highly active cells; fluorescence quenching by test compounds [47];

- Protein/biomass assays: variability in fixation or staining; insensitivity to metabolic suppression without cell loss [49];

3. Transition from Viability Endpoints to Mechanistic Approaches

3.1. From Viablity to High-Throughput Screening

3.2. Multiparametric and High-Content Imaging Approaches

3.3. Refining Genotoxicity Assays to Reduce False Outcomes

3.4. Bridging to Three-Dimensional Cultures and Organoids

4. Stem Cell-Based Models in Cytotoxicity Testing

4.1. Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs)

4.2. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs)

4.3. Applications in Developmental and Organ-Specific Toxicity

4.4. Ethical and Technical Considerations

- Declaration of Helsinki (2013)—Universal ethical principles for research involving human-derived material; mandates informed consent and independent ethical review [128];

- EU Directive 2004/23/EC—Standards for donor consent, traceability, and supervision across EU member states [129];

- NIH Stem Cell Registry (United States)—Specifies approved hESC lines for federally funded research in the US [130];

- ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation (2021)—Global reference for hESC/hiPSC research; emphasises informed consent, data protection, and prohibition of reproductive cloning [131];

- National and Institutional Oversight Committees—Ensure compliance with local ethical regulations [131].

- Documented donor consent (in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or somatic cell source);

- Registration of cell lines in recognised repositories;

4.5. Adult Stem Cell Models

5. Nanotoxicology and Specialised In Vitro Models

5.1. Cytotoxicity of Nanomaterials: Mechanistic Basis of Oxidative Stress

5.2. Adaptation of Classical Cytotoxicity Assays to Nanomaterials

5.3. Specialised In Vitro Models and Specific Endpoints

- Assay adaptation: Nanoparticles interfere with colorimetric and fluorometric assays by adsorbing dyes or catalysing redox reactions. Reliable assessment therefore requires nanoparticle-only controls and confirmation using orthogonal endpoints such as ATP quantification or impedance-based measurements [75,76,167,170].

6. Advanced 3D Models: Organoids, Organ-on-Chip, and Bioprinting

6.1. Organoids: Tissue-Specific and Immune-Competent Models

6.2. Microfluidics: Organ-on-Chip and Body-on-Chip Systems

6.3. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting: Standardisation and Reproducibility

6.4. Translational ADME–Tox Prediction and In Vivo Extrapolation

- Combine static and dynamic systems: Use organoids as foundational tissue modules and integrate them into microfluidic circuits to capture physiological flow, nutrient gradients, and metabolite exchange.

- Standardise culture conditions: Define media composition, extracellular matrix parameters, and bioprinting settings to minimise batch variation and improve reproducibility across laboratories.

- Benchmark with reference compounds: Validate functional readouts (e.g., albumin, urea, γ-GT, transporter activity) using well-characterised hepatotoxins or nephrotoxins before introducing novel agents.

- Implement multi-organ connectivity: Couple intestinal, hepatic, and renal modules to assess systemic ADME and metabolite-driven toxicity, supporting QIVIVE modelling.

- Integrate computational tools: Apply PBPK and QIVIVE frameworks to translate microphysiological outputs into clinically relevant exposure predictions.

- Ensure regulatory alignment: Follow OECD and FDA recommendations on Good Cell and Tissue Culture Practice and NAMs to support data acceptance and cross-sector harmonisation.

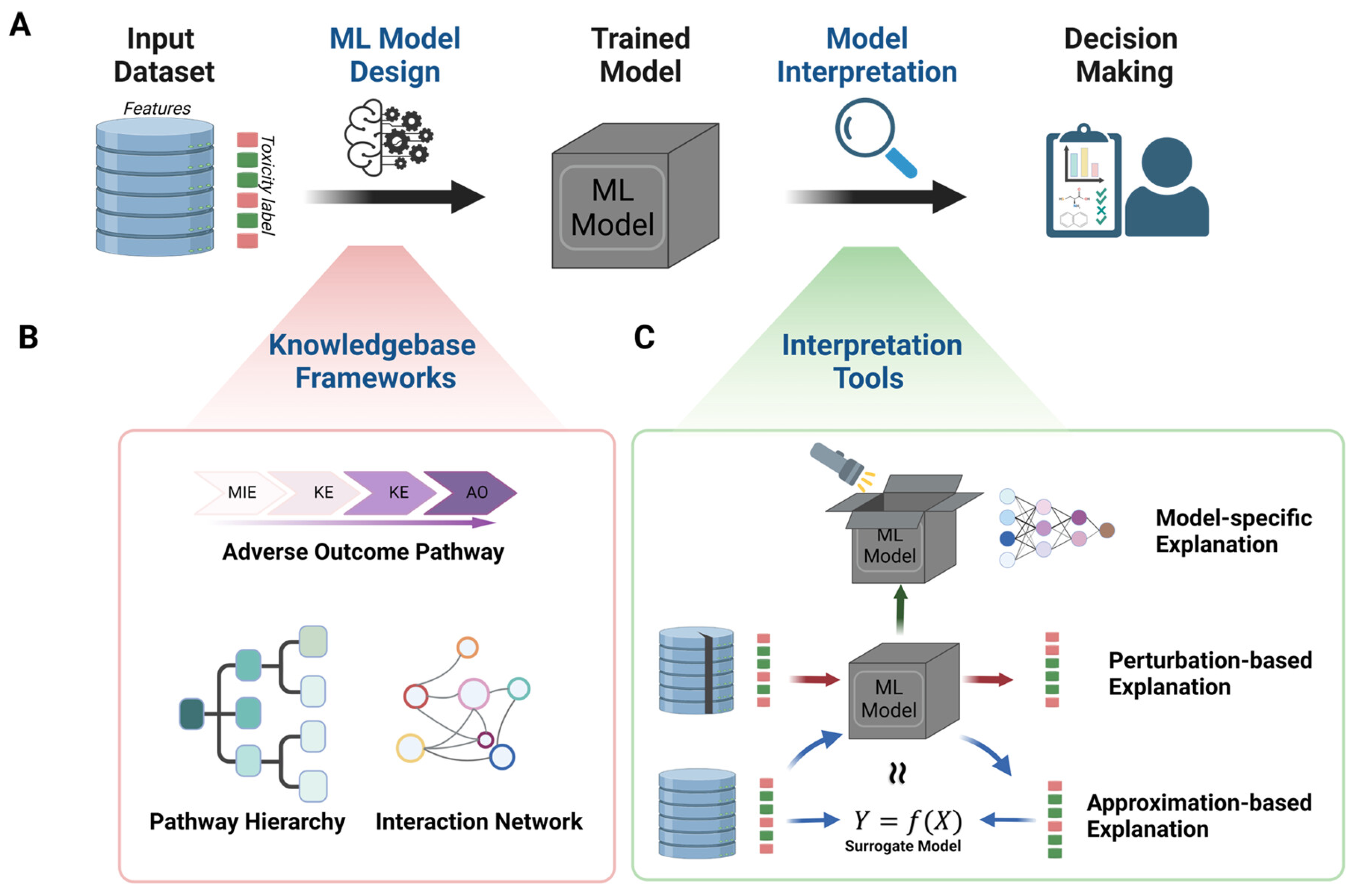

7. In Silico Approaches and Computational Toxicology

- Define the question and endpoint. Select a suitable modelling family (QSAR or ML) and the kinetic coupling (PBPK or QIVIVE) appropriate to the context.

- FAIR data curation. Standardise identifiers, harmonise units, remove duplicates and outliers, and record provenance and data partitions [204].

7.1. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships (QSAR), Read-Across, and Cheminformatics

- careful descriptor selection and redundancy control,

- transparent separation of training and validation sets,

- Y-randomisation to exclude chance correlations, and

7.2. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Cytotoxicity Prediction

7.3. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modelling

- Population relevance: evaluation of specific subgroups such as paediatrics, pregnancy, or hepatic/renal impairment.

- Uncertainty management: systematic sensitivity analysis of physiological and chemical parameters to assess influence on predictions.

- Model qualification: benchmarking against reliable clinical reference data [206].

7.4. Quantitative In Vitro–In Vivo Extrapolation (QIVIVE)

- (i)

- correction of in vitro concentrations for plastic and protein binding;

- (ii)

- determination of binding fractions in blood and tissues;

- (iii)

- measurement of metabolic and excretory clearance; and

- (iv)

- definition of the relevant exposure metric—Cmax, AUC, or steady state—with quantified uncertainty.

- Practical roadmaps for QIVIVE and integration into IATA [92]

- High-throughput PBTK for QIVIVE at scale [93]

- PBPK for decision making and uncertainty analysis [206]

- Model-informed development for special populations [94]

- Linking phenotypic profiling with QIVIVE (Cell Painting) [66]

- PFAS: epigenetic key event integration within PBPK [221]

- AChE inhibition: kinetic cross-species concordance [220]

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

7.5. Software and Web-Based Tools for In Silico Toxicity and Pharmacokinetic Modelling

7.5.1. QSAR and Machine Learning Platforms

7.5.2. PBPK and ADME–Tox Modelling Suites

8. Integrated Approaches and Regulatory Perspectives

8.1. From Concept to Practice: Building Confidence in NAMs

- Skin sensitization—The DA (OECD TG 497) is validated for identifying sensitising chemicals but not for potency ranking or quantitative risk assessment [229].

- Skin irritation—Reconstructed human epidermis models (OECD TG 439) are accepted for classification and labelling but not for chronic or systemic toxicity testing [230].

8.2. Case Studies and Regulatory Uptake

- ReproTracker—Tracks differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into germ layers to detect embryotoxic and teratogenic effects through gene expression markers [239].

- PluriLum Test—Combines stem cell differentiation with high-content imaging and transcriptomics, generating mechanistic fingerprints of disrupted morphogenesis [240].

8.3. Global Regulatory Perspectives

8.4. Outlook and Emerging Trends

9. Limitations and Future Perspectives

10. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D/3D | Two-/Three-Dimensional Cell Culture |

| 3Rs | Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement |

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| DA | Defined Approach |

| DDI | Drug–drug interaction |

| DILI | Drug-Induced Liver Injury |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HCI | High-Content Imaging |

| hESC | Human Embryonic Stem Cell |

| hiPSC/iPSC | (Human) Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| hiPSC-CM | hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocyte |

| HSC | Hematopoietic Stem Cell |

| qHTS | Quantitative High-Throughput Screening |

| IATA | Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment |

| ISSCR | International Society for Stem Cell Research |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MPS | Microphysiological System |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NAMs | New Approach Methodologies |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NRU | Neutral Red Uptake |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PBPK | Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (Modelling) |

| PFAS | Polyfluoroalkyl Substances |

| PI | Propidium Iodide |

| PSC | Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| QIVIVE | Quantitative In Vitro–In Vivo Extrapolation |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RTCA | Real-Time Cell Analysis |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| STS | Sequential Testing Strategy |

| tcpl | ToxCast Pipeline for Curve Fitting |

| Tox21/ToxCast | U.S. Toxicology Data Programs for High-Throughput Screening |

References

- Taylor, K. Ten Years of REACH—An Animal Protection Perspective. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2018, 46, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. “The Future of in Vitro Toxicology”. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 1217–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartung, T. Toxicology for the Twenty-First Century. Nature 2009, 460, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenbrand, G.; Pool-Zobel, B.; Baker, V.; Balls, M.; Blaauboer, B.J.; Boobis, A.; Carere, A.; Kevekordes, S.; Lhuguenot, J.C.; Pieters, R.; et al. Methods of in Vitro Toxicology. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 193–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipes, N.S.; Padilla, S.; Knudsen, T.B. Zebrafish: As an Integrative Model for Twenty-First Century Toxicity Testing. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 2011, 93, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, A.P.; Patlewicz, G. Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 856, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Zhang, Q.; Carmichael, P.L.; Boekelheide, K.; Andersen, M.E. Toxicity Testing in the 21 Century: Defining New Risk Assessment Approaches Based on Perturbation of Intracellular Toxicity Pathways. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlier, D.; Thomasset, N. Use of MTT Colorimetric Assay to Measure Cell Activation. J. Immunol. Methods 1986, 94, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, T.; Lohmann-Matthes, M.L. A Quick and Simple Method for the Quantitation of Lactate Dehydrogenase Release in Measurements of Cellular Cytotoxicity and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Activity. J. Immunol. Methods 1988, 115, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenfreund, E.; Puerner, J.A. Toxicity Determined in Vitro by Morphological Alterations and Neutral Red Absorption. Toxicol. Lett. 1985, 24, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotakis, G.; Timbrell, J.A. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays: Comparison of LDH, Neutral Red, MTT and Protein Assay in Hepatoma Cell Lines Following Exposure to Cadmium Chloride. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 160, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearfield, K.L.; Thybaud, V.; Cimino, M.C.; Custer, L.; Czich, A.; Harvey, J.S.; Hester, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kirkland, D.; Levy, D.D.; et al. Follow-up Actions from Positive Results of in Vitro Genetic Toxicity Testing. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2011, 52, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxicology Testing in the 21st Century (Tox21)|US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/toxicology-testing-21st-century-tox21 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Toxicity Forecasting (ToxCast)|US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/comptox-tools/toxicity-forecasting-toxcast (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Shukla, S.J.; Huang, R.; Austin, C.P.; Xia, M. The Future of Toxicity Testing: A Focus on in Vitro Methods Using a Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Platform. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.W.; Peters, M.F.; Dragan, Y.P. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Their Use in Drug Discovery for Toxicity Testing. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 219, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.; Sureshkumar, P.; Sotiriadou, I.; Hescheler, J.; Sachinidis, A. Human Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Based Toxicity Testing Models: Future Applications in New Drug Discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 3495–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrand, A.M.; Dai, L.; Schlager, J.J.; Hussain, S.M. Toxicity Testing of Nanomaterials. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 745, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Rajwade, J.M.; Paknikar, K.M. Nanotoxicology and in Vitro Studies: The Need of the Hour. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 258, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillegass, J.M.; Shukla, A.; Lathrop, S.A.; MacPherson, M.B.; Fukagawa, N.K.; Mossman, B.T. Assessing Nanotoxicity in Cells in Vitro. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 2, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampaloni, F.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Three-Dimensional Cell Cultures in Toxicology. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2010, 26, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zuo, X.; Yuan, J.; Xie, Z.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J. Research Progress in the Development of 3D Skin Models and Their Application to in Vitro Skin Irritation Testing. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, J.; Bertero, A.; Coccini, T.; Baderna, D.; Buzanska, L.; Caloni, F. Organoids Are Promising Tools for Species-Specific in Vitro Toxicological Studies. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, K.L.; Colquhoun, J.; Hannan, N.R.F. Intestinal Organoids for Modelling Intestinal Development and Disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Midwoud, P.M.; Verpoorte, E.; Groothuis, G.M.M. Microfluidic Devices for in Vitro Studies on Liver Drug Metabolism and Toxicity. Integr. Biol. 2011, 3, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahler, G.J.; Esch, M.B.; Stokol, T.; Hickman, J.J.; Shuler, M.L. Body-on-a-Chip Systems for Animal-Free Toxicity Testing. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2016, 44, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, S. Organs-on-a-Chip: Current Applications and Consideration Points for in Vitro ADME-Tox Studies. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 33, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groothuis, F.A.; Heringa, M.B.; Nicol, B.; Hermens, J.L.M.; Blaauboer, B.J.; Kramer, N.I. Dose Metric Considerations in in Vitro Assays to Improve Quantitative in Vitro-in Vivo Dose Extrapolations. Toxicology 2015, 332, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, M.E.B.; Lipscomb, J.C. Gaining Acceptance for the Use of in Vitro Toxicity Assays and QIVIVE in Regulatory Risk Assessment. Toxicology 2015, 332, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlewicz, G.; Fitzpatrick, J.M. Current and Future Perspectives on the Development, Evaluation, and Application of in Silico Approaches for Predicting Toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, R.D. In Silico Methods for Toxicity Prediction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 745, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, M.M.; Sepehri, S.; Midali, M.; Stinckens, M.; Biesiekierska, M.; Wolniakowska, A.; Gatzios, A.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Reszka, E.; Marinovich, M.; et al. Recent Advances and Current Challenges of New Approach Methodologies in Developmental and Adult Neurotoxicity Testing. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1271–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creton, S.; Dewhurst, I.C.; Earl, L.K.; Gehen, S.C.; Guest, R.L.; Hotchkiss, J.A.; Indans, I.; Woolhiser, M.R.; Billington, R. Acute Toxicity Testing of Chemicals-Opportunities to Avoid Redundant Testing and Use Alternative Approaches. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010, 40, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmus, K.R. The Draize Eye Test. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2001, 45, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Ahearne, M.; Hopkinson, A. An Overview of Current Techniques for Ocular Toxicity Testing. Toxicology 2015, 327, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.V.; Herst, P.M.; Tan, A.S. Tetrazolium Dyes as Tools in Cell Biology: New Insights into Their Cellular Reduction. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 2005, 11, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, G.; del Peso, A.; Zurita, J.L. Neutral Red Uptake Assay for the Estimation of Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E. Human Organs-on-Chips for Disease Modelling, Drug Development and Personalized Medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doost, N.F.; Srivastava, S.K.; Doost, N.F.; Srivastava, S.K. A Comprehensive Review of Organ-on-a-Chip Technology and Its Applications. Biosensors 2024, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehullah, A.; Tan, S.H.; Barker, N. Organoids as an in Vitro Model of Human Development and Disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, A.; Joubert, A.M.; Cromarty, A.D. Limitations of the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-Diphenyl-2H-Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assay When Compared to Three Commonly Used Cell Enumeration Assays. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specian, A.F.L.; Serpeloni, J.M.; Tuttis, K.; Ribeiro, D.L.; Cilião, H.L.; Varanda, E.A.; Sannomiya, M.; Martinez-Lopez, W.; Vilegas, W.; Cólus, I.M.S. LDH, Proliferation Curves and Cell Cycle Analysis Are the Most Suitable Assays to Identify and Characterize New Phytotherapeutic Compounds. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, A.L.; Moravec, R.A.; Riss, T.L. In Vitro Viability and Cytotoxicity Testing and Same-Well Multi-Parametric Combinations for High Throughput Screening. Curr. Chem. Genom. 2009, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacanli, M.; Anlar, H.G.; Başaran, A.A.; Başaran, N. Assessment of Cytotoxicity Profiles of Different Phytochemicals: Comparison of Neutral Red and MTT Assays in Different Cells in Different Time Periods. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, S.K.; Lettieri, T. Comparison of Four Different Colorimetric and Fluorometric Cytotoxicity Assays in a Zebrafish Liver Cell Line. BMC Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ji, J.; Fan, Y. A Resazurin-Based, Nondestructive Assay for Monitoring Cell Proliferation during a Scaffold-Based 3D Culture Process. Regen. Biomater. 2020, 7, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żyro, D.; Radko, L.; Śliwińska, A.; Chęcińska, L.; Kusz, J.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Przekora, A.; Wójcik, M.; Posyniak, A.; Ochocki, J. Multifunctional Silver(I) Complexes with Metronidazole Drug Reveal Antimicrobial Properties and Antitumor Activity against Human Hepatoma and Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limame, R.; Wouters, A.; Pauwels, B.; Fransen, E.; Peeters, M.; Lardon, F.; de Wever, O.; Pauwels, P. Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Cell Viability, Migration and Invasion Assessments by Novel Real-Time Technology and Classic Endpoint Assays. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiró, L.R.; Comerlato, L.C.; Da Silva, M.V.; Zuanazzi, J.Â.S.; Von Poser, G.L.; Ziulkoski, A.L. Toxicity of Glandularia Selloi (Spreng.) Tronc. Leave Extract by MTT and Neutral Red Assays: Influence of the Test Medium Procedure. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2017, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kourkopoulos, A.; Sijm, D.T.H.M.; Geerken, J.; Vrolijk, M.F. Compatibility and Interference of Food Simulants and Organic Solvents with the in Vitro Toxicological Assessment of Food Contact Materials. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e17659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostingh, G.J.; Casals, E.; Italiani, P.; Colognato, R.; Stritzinger, R.; Ponti, J.; Pfaller, T.; Kohl, Y.; Ooms, D.; Favilli, F.; et al. Problems and Challenges in the Development and Validation of Human Cell-Based Assays to Determine Nanoparticle-Induced Immunomodulatory Effects. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2011, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, L.C.B.; Nunes, H.L.; Ribeiro, D.L.; do Nascimento, J.R.; da Rocha, C.Q.; de Syllos Cólus, I.M.; Serpeloni, J.M. Aglycone Flavonoid Brachydin A Shows Selective Cytotoxicity and Antitumoral Activity in Human Metastatic Prostate (DU145) Cancer Cells. Cytotechnology 2021, 73, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M.A.; Patil, K.; Ettayebi, K.; Estes, M.K.; Atmar, R.L.; Ramani, S. Divergent Responses of Human Intestinal Organoid Monolayers Using Commercial in Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernilla, A.; Rodrigues, B.D.S.; Pieters, A.; Caufriez, A.; Leroy, K.; Van Campenhout, R.; Cooreman, A.; Gomes, A.R.; Arnesdotter, E.; Gijbels, E.; et al. In Vitro Liver Toxicity Testing of Chemicals: A Pragmatic Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filer, D.L.; Kothiya, P.; Woodrow Setzer, R.; Judson, R.S.; Martin, M.T. Tcpl: The ToxCast Pipeline for High-Throughput Screening Data. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hallinger, D.R.; Murr, A.S.; Buckalew, A.R.; Lougee, R.R.; Richard, A.M.; Laws, S.C.; Stoker, T.E. High-Throughput Screening and Chemotype-Enrichment Analysis of ToxCast Phase II Chemicals Evaluated for Human Sodium-Iodide Symporter (NIS) Inhibition. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hsieh, J.H.; Huang, R.; Sakamuru, S.; Hsin, L.Y.; Xia, M.; Shockley, K.R.; Auerbach, S.; Kanaya, N.; Lu, H.; et al. Cell-Based High-Throughput Screening for Aromatase Inhibitors in the Tox21 10K Library. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 147, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xia, M.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Q. Identification of Nonmonotonic Concentration-Responses in Tox21 High-Throughput Screening Estrogen Receptor Assays. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 452, 116206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, T.E.; Wang, J.; Murr, A.S.; Bailey, J.R.; Buckalew, A.R. High-Throughput Screening of ToxCast PFAS Chemical Library for Potential Inhibitors of the Human Sodium Iodide Symporter. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2023, 36, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ostrowska, K.; Maciejewski, H.; Appelhans, D.; Misiewicz, M.; Ziemba, B.; Bednarek, M.; Bryszewska, M.; Borowiec, M. PPI-G4 Glycodendrimers Upregulate TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells. Macromol. Biosci. 2017, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. A Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Data Analysis Pipeline for Activity Profiling. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2474, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.J. High-Content Analysis in Toxicology: Screening Substances for Human Toxicity Potential, Elucidating Subcellular Mechanisms and in Vivo Use as Translational Safety Biomarkers. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 115, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, H.L.; Adams, M.; Higgins, J.; Bond, J.; Morrison, E.E.; Bell, S.M.; Warriner, S.; Nelson, A.; Tomlinson, D.C. High-Content, High-Throughput Screening for the Identification of Cytotoxic Compounds Based on Cell Morphology and Cell Proliferation Markers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.A.; Singh, S.; Han, H.; Davis, C.T.; Borgeson, B.; Hartland, C.; Kost-Alimova, M.; Gustafsdottir, S.M.; Gibson, C.C.; Carpenter, A.E. Cell Painting, a High-Content Image-Based Assay for Morphological Profiling Using Multiplexed Fluorescent Dyes. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, J.; Willis, C.; Harris, F.R.; Foster, M.J.; Chambers, B.; Culbreth, M.; Brockway, R.E.; Davidson-Fritz, S.; Dawson, D.; Shah, I.; et al. Application of Cell Painting for Chemical Hazard Evaluation in Support of Screening-Level Chemical Assessments. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2023, 468, 116513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, Y.; Joshi, K.; Hickey, C.; Wahler, J.; Wall, B.; Etter, S.; Smith, B.; Griem, P.; Tate, M.; Jones, F.; et al. The BlueScreen HC Assay to Predict the Genotoxic Potential of Fragrance Materials. Mutagenesis 2022, 37, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, J.G.; Rudolph, J.; Bailey, D. Phenotypic Screening in Cancer Drug Discovery—Past, Present and Future. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, L.; Corallo, L.; Caterini, J.; Su, J.; Gisonni-Lex, L.; Gajewska, B. Application of XCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis to the Microplate Assay for Pertussis Toxin Induced Clustering in CHO Cells. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Serra, J.; Ggutierrez, A.; Muñoz-Ccapó, S.; Nnavarro-Palou, M.; Rros, T.; Aamat, J.C.; Lopez, B.; Marcus, T.F.; Fueyo, L.; Suquia, A.G.; et al. XCELLigence System for Real-Time Label-Free Monitoring of Growth and Viability of Cell Lines from Hematological Malignancies. OncoTargets Ther. 2014, 7, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramis, G.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Quereda, J.J.; Mendonça, L.; Majado, M.J.; Gomez-Coelho, K.; Mrowiec, A.; Herrero-Medrano, J.M.; Abellaneda, J.M.; Pallares, F.J.; et al. Optimization of Cytotoxicity Assay by Real-Time, Impedance-Based Cell Analysis. Biomed. Microdevices 2013, 15, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnevier, J.; Hammerbeck, C.; Goetz, C. Flow Cytometry: Definition, History, and Uses in Biological Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.B.; Khare, P.; Pandey, A.K. Flow Cytometry: Applications in Cellular and Molecular Toxicology; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ziółkowska, E.; Ziemba, B.; Appelhans, D.; Maciejewski, H.; Voit, B.; Kaczmarek, A.; Robak, T.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Cebula-Obrzut, B.; et al. Glycodendrimer PPI as a Potential Drug in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia. The Influence of Glycodendrimer on Apoptosis in In Vitro B-CLL Cells Defined by Microarrays. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2022, 17, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.L.; Goth-Goldstein, R.; Lucas, D.; Koshland, C.P. Particle-Induced Artifacts in the MTT and LDH Viability Assays. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 1885–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente-Jiménez, J.L.; Rodríguez-Rivas, C.I.; Mitre-Aguilar, I.B.; Torres-Copado, A.; García-López, E.A.; Herrera-Celis, J.; Arvizu-Espinosa, M.G.; Garza-Navarro, M.A.; Arriaga, L.G.; García, J.L.; et al. A Comparative and Critical Analysis for In Vitro Cytotoxic Evaluation of Magneto-Crystalline Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles Using MTT, Crystal Violet, LDH, and Apoptosis Assay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.; Smith, K.; Young, J.; Jeffrey, L.; Kirkland, D.; Pfuhler, S.; Carmichael, P. Reduction of Misleading (“False”) Positive Results in Mammalian Cell Genotoxicity Assays. I. Choice of Cell Type. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2012, 742, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.; Smith, R.; Smith, K.; Young, J.; Jeffrey, L.; Kirkland, D.; Pfuhler, S.; Carmichael, P. Reduction of Misleading (“False”) Positive Results in Mammalian Cell Genotoxicity Assays. II. Importance of Accurate Toxicity Measurement. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2012, 747, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, P.; Smith, R.; Smith, K.; Young, J.; Jeffrey, L.; Carmichael, P.; Kirkland, D.; Pfuhler, S. Reduction of Misleading (“false”) Positive Results in Mammalian Cell Genotoxicity Assays. III: Sensitivity of Human Cell Types to Known Genotoxic Agents. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2014, 767, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.; Ge, J.; Cohen, J.; Pyrgiotakis, G.; Engelward, B.P.; Demokritou, P. High-Throughput Screening Platform for Engineered Nanoparticle-Mediated Genotoxicity Using CometChip Technology. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2118–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yanamandra, A.K.; Qu, B. A High-Throughput 3D Kinetic Killing Assay. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, 2350505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo Pimentel, V.; Yaromina, A.; Marcus, D.; Dubois, L.J.; Lambin, P. A Novel Co-Culture Assay to Assess Anti-Tumor CD8+ T Cell Cytotoxicity via Luminescence and Multicolor Flow Cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 2020, 487, 112899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Sanny, A.; Chan, D.L.K.; van Noort, D.; Lim, W.; Tan, A.H.M.; Park, S. 3D Hanging Spheroid Plate for High-Throughput CAR T Cell Cytotoxicity Assay. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Son, K.; Hwang, Y.; Ko, J.; Lee, Y.; Doh, J.; Jeon, N.L. High-Throughput Microfluidic 3D Cytotoxicity Assay for Cancer Immunotherapy (CACI-IMPACT Platform). Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.B.; Huang, R.; Braisted, J.; Chu, P.H.; Simeonov, A.; Gerhold, D.L. 3D-Suspension Culture Platform for High Throughput Screening of Neurotoxic Chemicals Using LUHMES Dopaminergic Neurons. SLAS Discov. 2024, 29, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.J.; Meyer, S.R.; O’Meara, M.J.; Huang, S.; Capeling, M.M.; Ferrer-Torres, D.; Childs, C.J.; Spence, J.R.; Fontana, R.J.; Sexton, J.Z. A Human Liver Organoid Screening Platform for DILI Risk Prediction. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Geng, X.; Li, B. A 3D Spheroid Model of Quadruple Cell Co-Culture with Improved Liver Functions for Hepatotoxicity Prediction. Toxicology 2024, 505, 153829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karassina, N.; Hofsteen, P.; Cali, J.J.; Vidugiriene, J. Time- and Dose-Dependent Toxicity Studies in 3D Cultures Using a Luminescent Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2255, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominijanni, A.J.; Devarasetty, M.; Forsythe, S.D.; Votanopoulos, K.I.; Soker, S. Cell Viability Assays in Three-Dimensional Hydrogels: A Comparative Study of Accuracy. Tissue Eng. Part. C Methods 2021, 27, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurrell, T.; Lilley, K.S.; Cromarty, A.D. Proteomic Responses of HepG2 Cell Monolayers and 3D Spheroids to Selected Hepatotoxins. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 300, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeisser, S.; Miccoli, A.; von Bergen, M.; Berggren, E.; Braeuning, A.; Busch, W.; Desaintes, C.; Gourmelon, A.; Grafström, R.; Harrill, J.; et al. New Approach Methodologies in Human Regulatory Toxicology—Not If, but How and When! Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Tan, Y.M.; Allen, D.G.; Bell, S.; Brown, P.C.; Browning, L.; Ceger, P.; Gearhart, J.; Hakkinen, P.J.; Kabadi, S.V.; et al. IVIVE: Facilitating the Use of In Vitro Toxicity Data in Risk Assessment and Decision Making. Toxics 2022, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.; Ring, C.L.; Kreutz, A.; Goldsmith, M.R.; Wambaugh, J.F. High-Throughput PBTK Models for in Vitro to in Vivo Extrapolation. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2021, 17, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, V.; Venkatakrishnan, K. Role of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Simulation in Enabling Model-Informed Development of Drugs and Biotherapeutics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 60 (Suppl. 1), S7–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.W.; Austin, S.; Gamma, M.; Cheff, D.M.; Lee, T.D.; Wilson, K.M.; Johnson, J.; Travers, J.; Braisted, J.C.; Guha, R.; et al. Cytotoxic Profiling of Annotated and Diverse Chemical Libraries Using Quantitative High-Throughput Screening. SLAS Discov. 2020, 25, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambale, F.; Lavrentieva, A.; Stahl, F.; Blume, C.; Stiesch, M.; Kasper, C.; Bahnemann, D.; Scheper, T. Three Dimensional Spheroid Cell Culture for Nanoparticle Safety Testing. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 205, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, A.K.; Kolde, R.; Gaspar, J.A.; Rempel, E.; Balmer, N.V.; Meganathan, K.; Vojnits, K.; Baquié, M.; Waldmann, T.; Ensenat-Waser, R.; et al. Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Test Systems for Developmental Neurotoxicity: A Transcriptomics Approach. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaseeli, I.; Doss, M.; Antzelevitch, C.; Hescheler, J.; Sachinidis, A. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Model for Accelerated Patient- and Disease-Specific Drug Discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.; Klima, S.; Sureshkumar, P.S.; Meganathan, K.; Jagtap, S.; Rempel, E.; Rahnenführer, J.; Hengstler, J.G.; Waldmann, T.; Hescheler, J.; et al. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Based Developmental Toxicity Assays for Chemical Safety Screening and Systems Biology Data Generation. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 2015, e52333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Shapiro, S.S.; Waknitz, M.A.; Swiergiel, J.J.; Marshall, V.S.; Jones, J.M. Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science 1998, 282, 1145–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magdy, T.; Schuldt, A.J.T.; Wu, J.C.; Bernstein, D.; Burridge, P.W. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (HiPSC)-Derived Cells to Assess Drug Cardiotoxicity: Opportunities and Problems. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 58, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, D.S.; Alawathugoda, T.T.; Ansari, S.A. Fine Tuning of Hepatocyte Differentiation from Human Embryonic Stem Cells: Growth Factor vs. Small Molecule-Based Approaches. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 5968236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.; Withey, S.; Harrison, S.; Segeritz, C.P.; Zhang, F.; Atkinson-Dell, R.; Rowe, C.; Gerrard, D.T.; Sison-Young, R.; Jenkins, R.; et al. Phenotypic and Functional Analyses Show Stem Cell-Derived Hepatocyte-like Cells Better Mimic Fetal Rather than Adult Hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelting, L.; Scheinhardt, B.; Bondarenko, O.; Schildknecht, S.; Kapitza, M.; Tanavde, V.; Tan, B.; Lee, Q.Y.; Mecking, S.; Leist, M.; et al. A 3-Dimensional Human Embryonic Stem Cell (HESC)-Derived Model to Detect Developmental Neurotoxicity of Nanoparticles. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.; Tan, J.B.L.; Lim, L.W.; Tan, K.O.; Heng, B.C.; Lim, W.L. Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Neural Lineages as In Vitro Models for Screening the Neuroprotective Properties of Lignosus Rhinocerus (Cooke) Ryvarden. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3126376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotasová, H.; Capandová, M.; Pelková, V.; Dumková, J.; Koledová, Z.; Remšík, J.; Souček, K.; Garlíková, Z.; Sedláková, V.; Rabata, A.; et al. Expandable Lung Epithelium Differentiated from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 19, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, B.; Son, M.Y.; Jung, K.B.; Kim, U.; Kim, J.; Kwon, O.; Son, Y.S.; Jung, C.R.; Park, J.H.; Kim, C.Y. Next-Generation Intestinal Toxicity Model of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Enterocyte-Like Cells. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 587659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Torren, C.R.; Zaldumbide, A.; Duinkerken, G.; Brand-Schaaf, S.H.; Peakman, M.; Stangé, G.; Martinson, L.; Kroon, E.; Brandon, E.P.; Pipeleers, D.; et al. Immunogenicity of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.L.; Tan, B.Z.; Goh, W.X.T.; Cua, S.; Choo, A. In Vivo Surveillance and Elimination of Teratoma-Forming Human Embryonic Stem Cells with Monoclonal Antibody 2448 Targeting Annexin A2. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 2996–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Wang, C.K.; Yang, S.C.; Hsu, S.C.; Lin, H.; Chang, F.P.; Kuo, T.C.; Shen, C.N.; Chiang, P.M.; Hsiao, M.; et al. Elimination of Undifferentiated Human Embryonic Stem Cells by Cardiac Glycosides. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Xiong, Y.; Siddiq, M.M.; Dhanan, P.; Hu, B.; Shewale, B.; Yadaw, A.S.; Jayaraman, G.; Tolentino, R.E.; Chen, Y.; et al. Multiscale Mapping of Transcriptomic Signatures for Cardiotoxic Drugs. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.M.; Sparks, N.R.L.; Puig-Sanvicens, V.; Rodrigues, B.; Zur Nieden, N.I. An Evaluation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Test for Cardiac Developmental Toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozawa, T.; Kimura, M.; Cai, Y.; Saiki, N.; Yoneyama, Y.; Ouchi, R.; Koike, H.; Maezawa, M.; Zhang, R.R.; Dunn, A.; et al. High-Fidelity Drug-Induced Liver Injury Screen Using Human Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Organoids. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 831–846.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carberry, C.K.; Ferguson, S.S.; Beltran, A.S.; Fry, R.C.; Rager, J.E. Using Liver Models Generated from Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (IPSCs) for Evaluating Chemical-Induced Modifications and Disease across Liver Developmental Stages. Toxicol. Vitr. 2022, 83, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Inaba, T.; Shinke, K.; Hiramatsu, N.; Horie, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Hata, Y.; Sugihara, E.; Takimoto, T.; Nagai, N.; et al. Comprehensive Search for Genes Involved in Thalidomide Teratogenicity Using Early Differentiation Models of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Potential Applications in Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity Testing. Cells 2025, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xie, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, X.; Sánchez, O.F.; Rochet, J.C.; Freeman, J.L.; Yuan, C. Developmental Neurotoxicity of PFOA Exposure on HiPSC-Derived Cortical Neurons. Environ. Int. 2024, 190, 108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandasamy, K.; Chuah, J.K.C.; Su, R.; Huang, P.; Eng, K.G.; Xiong, S.; Li, Y.; Chia, C.S.; Loo, L.H.; Zink, D. Prediction of Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity and Injury Mechanisms with Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cells and Machine Learning Methods. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achberger, K.; Probst, C.; Haderspeck, J.C.; Bolz, S.; Rogal, J.; Chuchuy, J.; Nikolova, M.; Cora, V.; Antkowiak, L.; Haq, W.; et al. Merging Organoid and Organ-on-a-Chip Technology to Generate Complex Multi-Layer Tissue Models in a Human Retina-on-a-Chip Platform. eLife 2019, 8, e46188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, K.C.; Kurokawa, Y.K.; Hajek, B.S.; Paladin, J.A.; Shirure, V.S.; George, S.C. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem-Cardiac-Endothelial-Tumor-on-a-Chip to Assess Anticancer Efficacy and Cardiotoxicity. Tissue Eng. Part. C Methods 2020, 26, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauschke, K.; Rosenmai, A.K.; Meiser, I.; Neubauer, J.C.; Schmidt, K.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Holst, B.; Taxvig, C.; Emnéus, J.K.; Vinggaard, A.M. A Novel Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Assay to Predict Developmental Toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 3831–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.; Antonijevic, T.; Hall, J.C.; Fisher, J. In Vitro and Computational Approaches to Predict Developmental Toxicity: Integrating PBPK Models with Cell-Based Assays. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 502, 117435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanjuk, S.; Zühr, E.; Dönmez, A.; Bartsch, D.; Kurian, L.; Tigges, J.; Fritsche, E. The Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Test as an Alternative Method for Embryotoxicity Testing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lei, W.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Shen, Z.; et al. Generation of Human Vascularized and Chambered Cardiac Organoids for Cardiac Disease Modelling and Drug Evaluation. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, 13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidball, A.M.; Niu, W.; Ma, Q.; Takla, T.N.; Walker, J.C.; Margolis, J.L.; Mojica-Perez, S.P.; Sudyk, R.; Deng, L.; Moore, S.J.; et al. Deriving Early Single-Rosette Brain Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 2498–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Comolli, D.; Fanelli, R.; Forloni, G.; De Paola, M. Neonicotinoid Pesticides Affect Developing Neurons in Experimental Mouse Models and in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (IPSC)-Derived Neural Cultures and Organoids. Cells 2024, 13, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive-2004/23-EN-EU Tissue Directive-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32004L0023 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- HESCRegistry-Public Lines|STEM Cell Information. Available online: https://stemcells.nih.gov/registry/eligible-to-use-lines (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Lovell-Badge, R.; Anthony, E.; Barker, R.A.; Bubela, T.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Carpenter, M.; Charo, R.A.; Clark, A.; Clayton, E.; Cong, Y.; et al. ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation: The 2021 Update. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltner, J.; Lanner, F. Refined Transcriptional Blueprint of Human Preimplantation Embryos. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1503–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, P. Some Mechanistic Requirements for Major Transitions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 0150439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalto-Setälä, K.; Conklin, B.R.; Lo, B. Obtaining Consent for Future Research with Induced Pluripotent Cells: Opportunities and Challenges. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, B.; Parham, L. Ethical Issues in Stem Cell Research. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzechowski, M.; Schochow, M.; Kühl, M.; Steger, F. Content and Method of Information for Participants in Clinical Studies with Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (IPSCs). Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 627816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, M. Ethical Aspects of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Alzheimer’s Disease: Potentials and Challenges of a Seemingly Harmless Method. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, G.; Keminer, O.; Leu, J.; Tandon, R.; Meiser, I.; Willing, A.; Winschel, I.; Abt, J.C.; Brändl, B.; Sébastien, I.; et al. An Automated and High-Throughput-Screening Compatible Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Test Platform for Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Assessment of Small Molecule Compounds. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2021, 37, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauschke, K.; Treschow, A.F.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Davidsen, N.; Holst, B.; Emnéus, J.; Taxvig, C.; Vinggaard, A.M. Creating a Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based NKX2.5 Reporter Gene Assay for Developmental Toxicity Testing. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I.C.; Bohrer, L.R.; Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Wiley, L.A.; Shrestha, A.; Harman, B.E.; Jiao, C.; Sohn, E.H.; Wendland, R.; Allen, B.N.; et al. Biocompatibility of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Progenitor Cell Grafts in Immunocompromised Rats. Cell Transpl. 2022, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Péault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Perspective: Cell Biology to Clinical Progress. NPJ Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak-Mnich, K.; Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Ziemba, B.; Pieszyński, I.; Bryszewska, M.; Kujawa, J. Effect of Photobiomodulation Therapy on the Morphology, Intracellular Calcium Concentration, Free Radical Generation, Apoptosis and Necrosis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells-an in Vitro Study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 39, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P.C.; Xu, H.; Wang, S.C.; Medina, S.; Burchiel, S.W. Evaluation of Toxicity in Mouse Bone Marrow Progenitor Cells. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2016, 67, 18.9.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, N.K.; Shukla, P.; Omer, A.; Singh, R.K. In-Vitro Hematological Toxicity Prediction by Colony-Forming Cell Assays. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent-Massin, D.; Hymery, N.; Sibiril, Y. Stem Cells in Myelotoxicity. Toxicology 2010, 267, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Sun, J.; Ma, T.; Hua, F.; Shen, Z. A Brief Review of Cytotoxicity of Nanoparticles on Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, I.; Goulielmaki, M.; Kritikos, A.; Zoumpourlis, P.; Koliakos, G.; Zoumpourlis, V. Suitability of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Fetal Umbilical Cord (Wharton’s Jelly) as an Alternative In Vitro Model for Acute Drug Toxicity Screening. Cells 2022, 11, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Venkatesan, V.; Prakhya, B.M.; Bhonde, R. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Novel Platform for Simultaneous Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Pharmaceuticals. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Cheng, Z.; Liang, S. Advantages and Prospects of Stem Cells in Nanotoxicology. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, B.; Babaahmadi, M.; Pakzad, M.; Hajinasrollah, M.; Mostafaei, F.; Jahangiri, S.; Kamali, A.; Baharvand, H.; Baghaban Eslaminejad, M.; Hassani, S.N.; et al. Standard Toxicity Study of Clinical-Grade Allogeneic Human Bone Marrow-Derived Clonal Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Cao, Y. Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Induced by ZnO Nanoparticles in Endothelial Cells: Interaction with Palmitate or Lipopolysaccharide. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M.; Sinha, S.; Jothiramajayam, M.; Jana, A.; Nag, A.; Mukherjee, A. Cyto-Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress Induced by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle in Human Lymphocyte Cells in Vitro and Swiss Albino Male Mice in Vivo. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 97, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Haddouti, E.M.; Beckert, H.; Biehl, R.; Pariyar, S.; Rüwald, J.M.; Li, X.; Jaenisch, M.; Burger, C.; Wirtz, D.C.; et al. Investigation of Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammatory Responses of Tantalum Nanoparticles in THP-1-Derived Macrophages. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 3824593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, B.; Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Pion, M.; Appelhans, D.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.Á.; Voit, B.; Bryszewska, M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Toxicity and Proapoptotic Activity of Poly(Propylene Imine) Glycodendrimers in Vitro: Considering Their Contrary Potential as Biocompatible Entity and Drug Molecule in Cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 461, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, M.; Brouwer, H.; Aalderink, G.; Bredeck, G.; Kämpfer, A.A.M.; Schins, R.P.F.; Bouwmeester, H. Investigating Nanoplastics Toxicity Using Advanced Stem Cell-Based Intestinal and Lung in Vitro Models. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1112212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.; Vilas-Boas, V.; Lebre, F.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Catarino, C.M.; Moreira Teixeira, L.; Loskill, P.; Alfaro-Moreno, E.; Ribeiro, A.R. Microfluidic-Based Skin-on-Chip Systems for Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1282–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiak-Szepietowska, M.; Karczmarczyk, A.; Jönsson-Niedziółka, M.; Winckler, T.; Feller, K.H. Development of Complex-Shaped Liver Multicellular Spheroids as a Human-Based Model for Nanoparticle Toxicity Assessment in Vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 294, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Matthews, B.D.; Mammoto, A.; Montoya-Zavala, M.; Yuan Hsin, H.; Ingber, D.E. Reconstituting Organ-Level Lung Functions on a Chip. Science 2010, 328, 1662–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benameur, L.; Auffan, M.; Cassien, M.; Liu, W.; Culcasi, M.; Rahmouni, H.; Stocker, P.; Tassistro, V.; Bottero, J.Y.; Rose, J.; et al. DNA Damage and Oxidative Stress Induced by CeO2 Nanoparticles in Human Dermal Fibroblasts: Evidence of a Clastogenic Effect as a Mechanism of Genotoxicity. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, H.; Mukherjee, S.P.; O’Neill, L.; Byrne, H.J. Structural Dependence of in Vitro Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Uptake Mechanisms of Poly(Propylene Imine) Dendritic Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016, 36, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdolenova, Z.; Drlickova, M.; Henjum, K.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Tulinska, J.; Bilanicova, D.; Pojana, G.; Kazimirova, A.; Barancokova, M.; Kuricova, M.; et al. Coating-Dependent Induction of Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9 (Suppl. 1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; Xiao, L.; Diener, L.; Arslan, O.; Hirsch, C.; Maeder-Althaus, X.; Grieder, K.; Wampfler, B.; Mathur, S.; Wick, P.; et al. In Vitro Mechanistic Study towards a Better Understanding of ZnO Nanoparticle Toxicity. Nanotoxicology 2013, 7, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ziemba, B.; Sikorska, H.; Jander, M.; Appelhans, D.; Bryszewska, M.; Borowiec, M. Neurotoxicity of Poly(Propylene Imine) Glycodendrimers. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzkiewicz, M.; Sztandera, K.; Jatczak-Pawlik, I.; Zinke, R.; Appelhans, D.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Pulaski, Ł. Terminal Sugar Moiety Determines Immunomodulatory Properties of Poly(Propyleneimine) Glycodendrimers. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1562–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illarionova, N.B.; Morozova, K.N.; Petrovskii, D.V.; Sharapova, M.B.; Romashchenko, A.V.; Troitskii, S.Y.; Kiseleva, E.; Moshkin, Y.M.; Moshkin, M.P. “Trojan-Horse” Stress-Granule Formation Mediated by Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liang, Y.; Wei, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M. ROS-Mediated NRF2/p-ERK1/2 Signaling-Involved Mitophagy Contributes to Macrophages Activation Induced by CdTe Quantum Dots. Toxicology 2024, 505, 153825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutary, A.; Sanderson, B.J.S. The MTT and Crystal Violet Assays: Potential Confounders in Nanoparticle Toxicity Testing. Int. J. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, K.M.; Marzi, A.; Wågbø, A.M.; Vermeulen, J.P.; de la Fonteyne-Blankestijn, L.J.J.; Rösslein, M.; Ossig, R.; Klinkenberg, G.; Vandebriel, R.J.; Schnekenburger, J. Standardization of an in Vitro Assay Matrix to Assess Cytotoxicity of Organic Nanocarriers: A Pilot Interlaboratory Comparison. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 2187–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, B.; Matuszko, G.; Bryszewska, M.; Klajnert, B. Influence of Dendrimers on Red Blood Cells. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2012, 17, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, D.; Marcinkowska, M.; Janaszewska, A.; Appelhans, D.; Voit, B.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Bryszewska, M.; Štofik, M.; Herma, R.; Duchnowicz, P.; et al. Influence of Core and Maltose Surface Modification of PEIs on Their Interaction with Plasma Proteins—Human Serum Albumin and Lysozyme. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 152, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, A.A.M.; Busch, M.; Schins, R.P.F. Advanced In Vitro Testing Strategies and Models of the Intestine for Nanosafety Research. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, A.; Kwon, I.H.; Lee, D.H.; Choi, W.H.; Lee, S.W.; Yoo, J.; Heo, M.B.; Lee, T.G. Novel Organoid Culture System for Improved Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franiak-Pietryga, I.; Ostrowska, K.; Maciejewski, H.; Ziemba, B.; Appelhans, D.; Voit, B.; Jander, M.; Treliński, J.; Bryszewska, M.; Borowiec, M. Affecting NF-ΚB Cell Signaling Pathway in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia by Dendrimers-Based Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 357, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikonorova, V.G.; Chrishtop, V.V.; Mironov, V.A.; Prilepskii, A.Y. Advantages and Potential Benefits of Using Organoids in Nanotoxicology. Cells 2023, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, M.; Aina, K.O.; Grandmougin, L.; Jäger, C.; Pérez Escriva, P.; Letellier, E.; Mosig, A.S.; Wilmes, P. An Organ-on-Chip Platform for Simulating Drug Metabolism Along the Gut-Liver Axis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2303943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, K.T.; Vanslambrouck, J.M.; Higgins, J.W.; Chambon, A.; Bishard, K.; Arndt, D.; Er, P.X.; Wilson, S.B.; Howden, S.E.; Tan, K.S.; et al. Cellular Extrusion Bioprinting Improves Kidney Organoid Reproducibility and Conformation. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.R.; Zhang, C.J.; Garcia, M.A.; Procario, M.C.; Yoo, S.; Jolly, A.L.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, K.; Kersten, R.D.; et al. A High-Throughput Microphysiological Liver Chip System to Model Drug-Induced Liver Injury Using Human Liver Organoids. Gastro Hep Adv. 2024, 3, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsard, J.; Savary, C.; Massart, J.; Viel, R.; Moutaux, L.; Catheline, D.; Rioux, V.; Clement, B.; Corlu, A.; Fromenty, B.; et al. 3D Multi-Cell-Type Liver Organoids: A New Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease for Drug Safety Assessments. Toxicol. Vitr. 2024, 94, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanslambrouck, J.M.; Wilson, S.B.; Tan, K.S.; Groenewegen, E.; Rudraraju, R.; Neil, J.; Lawlor, K.T.; Mah, S.; Scurr, M.; Howden, S.E.; et al. Enhanced Metanephric Specification to Functional Proximal Tubule Enables Toxicity Screening and Infectious Disease Modelling in Kidney Organoids. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilz, J.; Auge, I.; Groeneveld, K.; Reuter, S.; Mrowka, R. A Proof-of-Concept Assay for Quantitative and Optical Assessment of Drug-Induced Toxicity in Renal Organoids. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef Yengej, F.A.; Jansen, J.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Verhaar, M.C.; Clevers, H. Kidney Organoids and Tubuloids. Cells 2020, 9, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrofanova, O.; Nikolaev, M.; Xu, Q.; Broguiere, N.; Cubela, I.; Camp, J.G.; Bscheider, M.; Lutolf, M.P. Bioengineered Human Colon Organoids with in Vivo-like Cellular Complexity and Function. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 1175–1186.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelinsky, S.A.; Derksen, M.; Bauman, E.; Verissimo, C.S.; van Dooremalen, W.T.M.; Roos, J.L.; Barón, C.H.; Caballero-Franco, C.; Johnson, B.G.; Rooks, M.G.; et al. Molecular and Functional Characterization of Human Intestinal Organoids and Monolayers for Modeling Epithelial Barrier. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, E.T.; Arian, C.M.; Aryeh, K.S.; Wang, K.; Thummel, K.E.; Kelly, E.J. Human Intestinal Enteroids: Nonclinical Applications for Predicting Oral Drug Disposition, Toxicity, and Efficacy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 273, 108879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, J.; Cao, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Leng, L. A Skin Organoid-Based Infection Platform Identifies an Inhibitor Specific for HFMD. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rim, Y.A.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.J.; Kim, H.; Ahn, S.J.; Ju, J.H. Guidelines for Manufacturing and Application of Organoids: Skin. Int. J. Stem Cells 2024, 17, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.T.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Giangarra, V.; Grzeskowiak, C.L.; Ju, J.; Liu, I.H.; Chiou, S.H.; Salahudeen, A.A.; Smith, A.R.; et al. Organoid Modeling of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Cell 2018, 175, 1972–1988.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Lieshout, R.; van Tienderen, G.S.; de Ruiter, V.; van Royen, M.E.; Boor, P.P.C.; Magré, L.; Desai, J.; Köten, K.; Kan, Y.Y.; et al. Modelling Immune Cytotoxicity for Cholangiocarcinoma with Tumour-Derived Organoids and Effector T Cells. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avnet, S.; Di Pompo, G.; Borciani, G.; Fischetti, T.; Graziani, G.; Baldini, N. Advantages and Limitations of Using Cell Viability Assays for 3D Bioprinted Constructs. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 19, 25033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, M.; Giordano, E. Non-Destructive Monitoring of 3D Cell Cultures: New Technologies and Applications. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakolish, C.; Moyer, H.L.; Tsai, H.H.D.; Ford, L.C.; Dickey, A.N.; Wright, F.A.; Han, G.; Bajaj, P.; Baltazar, M.T.; Carmichael, P.L.; et al. Analysis of Reproducibility and Robustness of a Renal Proximal Tubule Microphysiological System OrganoPlate 3-Lane 40 for in Vitro Studies of Drug Transport and Toxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2023, 196, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, J.; Ghanem, A.; Wallisch, P.; Banaeiyan, A.A.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Taškova, K.; Haltmeier, M.; Kurtz, A.; Becker, H.; Reuter, S.; et al. Liver-Kidney-on-Chip To Study Toxicity of Drug Metabolites. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerkens, R.; Mooiweer, J.; Ramírez-Sánchez, A.D.; Oelen, R.; Franke, L.; Wijmenga, C.; Barrett, R.J.; Jonkers, I.H.; Withoff, S. An IPSC-Derived Small Intestine-on-Chip with Self-Organizing Epithelial, Mesenchymal, and Neural Cells. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, K.; Murrieta-Coxca, J.M.; Vogt, T.; Besser, S.; Geilen, D.; Kaden, T.; Bothe, A.K.; Morales-Prieto, D.M.; Amiri, B.; Schaller, S.; et al. Digital Twin-Enhanced Three-Organ Microphysiological System for Studying Drug Pharmacokinetics in Pregnant Women. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1528748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, M.C.; Bernal, P.N.; Oosterhoff, L.A.; van Wolferen, M.E.; Lehmann, V.; Vermaas, M.; Buchholz, M.B.; Peiffer, Q.C.; Malda, J.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; et al. Bioprinting of Human Liver-Derived Epithelial Organoids for Toxicity Studies. Macromol. Biosci. 2021, 21, 2100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Marsee, A.; van Tienderen, G.S.; Rezaeimoghaddam, M.; Sheikh, H.; Samsom, R.A.; de Koning, E.J.P.; Fuchs, S.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; et al. Accelerated Production of Human Epithelial Organoids in a Miniaturized Spinning Bioreactor. Cell Rep. Methods 2024, 4, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addario, G.; Moroni, L.; Mota, C. Kidney Fibrosis In Vitro and In Vivo Models: Path Toward Physiologically Relevant Humanized Models. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2403230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koido, M.; Kawakami, E.; Fukumura, J.; Noguchi, Y.; Ohori, M.; Nio, Y.; Nicoletti, P.; Aithal, G.P.; Daly, A.K.; Watkins, P.B.; et al. Polygenic Architecture Informs Potential Vulnerability to Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauschke, V.M. Toxicogenomics of Drug Induced Liver Injury—From Mechanistic Understanding to Early Prediction. Drug Metab. Rev. 2021, 53, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, N.G.; Ficek, R.A.; Markov, D.A.; McCawley, L.J.; Hutson, M.S. Toxicokinetics for Organ-on-Chip Devices. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, R.; Ingram, M.; Marquez, S.; Das, D.; Delahanty, A.; Herland, A.; Maoz, B.M.; Jeanty, S.S.F.; Somayaji, M.R.; Burt, M.; et al. Robotic Fluidic Coupling and Interrogation of Multiple Vascularized Organ Chips. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chou, W.C. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Toxicological Sciences. Toxicol. Sci. 2022, 189, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, T.; Zhu, H. Advancing Computational Toxicology by Interpretable Machine Learning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 17690–17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.T.D.; Belfield, S.J.; Briggs, K.A.; Enoch, S.J.; Firman, J.W.; Frericks, M.; Garrard, C.; Maccallum, P.H.; Madden, J.C.; Pastor, M.; et al. Making in Silico Predictive Models for Toxicology FAIR. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 140, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G. QSAR Methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2425, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbach, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Dixit, V.; Parrott, N.; Peters, S.A.; Poggesi, I.; Sharma, P.; Snoeys, J.; Shebley, M.; et al. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Renal and Hepatic Impairment Populations: A Pharmaceutical Industry Perspective. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.L.; Silvola, R.M.; Haas, D.M.; Quinney, S.K. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling in Pregnancy: Model Reproducibility and External Validation. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamer, T.M.; Zhou, H.; Hassan, M.A.; Abu-Serie, M.M.; Shityakov, S.; Elbayomi, S.M.; Mohy-Eldin, M.S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheang, T. Synthesis and Physicochemical Properties of an Aromatic Chitosan Derivative: In Vitro Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anticancer Evaluations, and in Silico Studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 240, 124339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Russo, D.P.; Ciallella, H.L.; Wang, Y.T.; Wu, M.; Aleksunes, L.M.; Zhu, H. Data-Driven Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Modeling for Human Carcinogenicity by Chronic Oral Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 6573–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Kemmler, E.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: A Webserver for the Prediction of Toxicity of Chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W513–W520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedykh, A.Y.; Shah, R.R.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Auerbach, S.S.; Gombar, V.K. Saagar-A New, Extensible Set of Molecular Substructures for QSAR/QSPR and Read-Across Predictions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Z.; Volarath, P.; Racz, R.; Cross, K.P.; Girireddy, M.; Chakravarti, S.; Stavitskaya, L. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Models to Predict Cardiac Adverse Effects. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 37, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Kalvass, J.C.; Degoey, D.; Hosmane, B.; Doktor, S.; Desino, K. Global Analysis of Models for Predicting Human Absorption: QSAR, In Vitro, and Preclinical Models. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 9389–9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, J.D.; Hao, Y.; Moore, J.H.; Penning, T.M. Automating Predictive Toxicology Using ComptoxAI. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1370–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; Pan, F.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. In Silico Prediction of Chemical Acute Dermal Toxicity Using Explainable Machine Learning Methods. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 37, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, W.; Tang, Y.; Liu, G. In Silico Prediction of HERG Blockers Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, M.; Bettonte, S.; Stader, F.; Battegay, M.; Marzolini, C. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling to Identify Physiological and Drug Parameters Driving Pharmacokinetics in Obese Individuals. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 62, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.C.; Chen, Q.; Yuan, L.; Cheng, Y.H.; He, C.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Riviere, J.E.; Lin, Z. An Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Model to Predict Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumors in Mice. J. Control. Release 2023, 361, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbek, O.; Genc, D.E.; Ulgen, K.O. Advances in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of Nanomaterials. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 2251–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, S.; Wesseling, S.; Kramer, N.I.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Bouwmeester, H. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition in Rats and Humans Following Acute Fenitrothion Exposure Predicted by Physiologically Based Kinetic Modeling-Facilitated Quantitative In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 20521–20531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.; Luo, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Human Health Risk Assessment of 6:2 Cl-PFESA through Quantitative in Vitro to in Vivo Extrapolation by Integrating Cell-Based Assays, an Epigenetic Key Event, and Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, J.C.; Thompson, C.V. Pharmacokinetic Tools and Applications. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2425, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tess, D.; Chang, G.C.; Keefer, C.; Carlo, A.; Jones, R.; Di, L. In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation and Scaling Factors for Clearance of Human and Preclinical Species with Liver Microsomes and Hepatocytes. AAPS J. 2023, 25, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Elmageed, G.M.A.; El-Qazaz, I.G.; El-Sayed, D.S.; El-Samad, L.M.; Abdou, H.M. The Synergistic Influence of Polyflavonoids from Citrus Aurantifolia on Diabetes Treatment and Their Modulation of the PI3K/AKT/FOXO1 Signaling Pathways: Molecular Docking Analyses and In Vivo Investigations. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, S. Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 123 (Suppl. 5), 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zalm, A.J.; Barroso, J.; Browne, P.; Casey, W.; Gordon, J.; Henry, T.R.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Lowit, A.B.; Perron, M.; Clippinger, A.J. A Framework for Establishing Scientific Confidence in New Approach Methodologies. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 2865–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell, F.; Alexander-White, C.; Brescia, S.; Currie, R.A.; Roberts, R.; Roper, C.; Vickers, C.; Westmoreland, C.; Kimber, I. New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): Identifying and Overcoming Hurdles to Accelerated Adoption. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 13, tfae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Guidance Document on the Reporting of Defined Approaches to Be Used Within Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 255; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Guideline No. 497: Defined Approaches on Skin Sensitisation; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 439: In Vitro Skin Irritation: Reconstructed Human Epidermis Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Stucki, A.O.; Barton-Maclaren, T.S.; Bhuller, Y.; Henriquez, J.E.; Henry, T.R.; Hirn, C.; Miller-Holt, J.; Nagy, E.G.; Perron, M.M.; Ratzlaff, D.E.; et al. Use of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to Meet Regulatory Requirements for the Assessment of Industrial Chemicals and Pesticides for Effects on Human Health. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 964553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, G.; Alépée, N.; Tan, B.; Roper, C.S. A Call to Action: Advancing New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in Regulatory Toxicology through a Unified Framework for Validation and Acceptance. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 162, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, G.H.; Bearth, A.; Jones, L.B.; Hoffmann, S.; Vist, G.E.; Ames, H.M.; Husøy, T.; Svendsen, C.; Tsaioun, K.; Ashikaga, T.; et al. Time for CHANGE: System-Level Interventions for Bringing Forward the Date of Effective Use of NAMs in Regulatory Toxicology. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 2299–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 431: In Vitro Skin Corrosion: Reconstructed Human Epidermis (RHE) Test Method; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Braakhuis, H.M.; Murphy, F.; Ma-Hock, L.; Dekkers, S.; Keller, J.; Oomen, A.G.; Stone, V. An Integrated Approach to Testing and Assessment to Support Grouping and Read-Across of Nanomaterials After Inhalation Exposure. Appl. Vitr. Toxicol. 2021, 7, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 492: Reconstructed Human Cornea-Like Epithelium (RhCE) Test Method for Identifying Chemicals Not Requiring Classification and Labelling for Eye Irritation or Serious Eye Damage; OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Knetzger, N.; Ertych, N.; Burgdorf, T.; Beranek, J.; Oelgeschläger, M.; Wächter, J.; Horchler, A.; Gier, S.; Windbergs, M.; Fayyaz, S.; et al. Non-Invasive in Vitro NAM for the Detection of Reversible and Irreversible Eye Damage after Chemical Exposure for GHS Classification Purposes (ImAi). Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissinger, H.; Knetzger, N.; Cleve, C.; Lotz, C. Impedance-Based in Vitro Eye Irritation Testing Enables the Categorization of Diluted Chemicals. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, T.; Myhre, O.; Fritsche, E.; Rüegg, J.; Craenen, K.; Aiello-Holden, K.; Agrillo, C.; Babin, P.J.; Escher, B.I.; Dirven, H.; et al. New Approach Methods to Assess Developmental and Adult Neurotoxicity for Regulatory Use: A PARC Work Package 5 Project. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1359507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, A.; Oyetade, O.B.; Chang, X.; Hsieh, J.H.; Behl, M.; Allen, D.G.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Hogberg, H.T. Integrated Approach for Testing and Assessment for Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) to Prioritize Aromatic Organophosphorus Flame Retardants. Toxics 2024, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies [PDF]. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/newsroom/published/roadmap_to_reducing_animal_testing_in_preclinical_safety_studies.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. New Approach Methodologies—EU Horizon Scanning Report; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025.

- Najjar, A.; Kühnl, J.; Lange, D.; Géniès, C.; Jacques, C.; Fabian, E.; Zifle, A.; Hewitt, N.J.; Schepky, A. Next-Generation Risk Assessment Read-across Case Study: Application of a 10-Step Framework to Derive a Safe Concentration of Daidzein in a Body Lotion. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1421601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Guiding Principles and Key Elements for Establishing a Weight of Evidence for Chemical Assessment; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 311; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zuang, V.; Baccaro, M.; Barroso, J.; Berggren, E.; Bopp, S.; Bridio, S.; Capeloa, T.; Carpi, D.; Casati, S.; Chinchio, E.; et al. Non-Animal Methods in Science and Regulation. In Proceedings of the Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 19–20 March 2025; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zuang, V.; Barroso, J.; Berggren, E.; Bopp, S.; Bridio, S.; Casati, S.; Corvi, R.; Deceuninck, P.; Franco, A.; Gastaldello, A.; et al. Non-Animal Methods in Science and Regulation—EURL ECVAM Status Report 2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zuang, V.; Daskalopoulos, E.P.; Worth, A.; Corvi, R.; Munn, S.; Deceuninck, P.; Barroso, J.; Batista Leite, S.; Berggren, E.; Bopp, S.; et al. Non-Animal Methods in Science and Regulation—EURL ECVAM Report 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Guidance Document on Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) for Phototoxicity Testing; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 397; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Performance Standards for the Assessment of Proposed Similar or Modified In Vitro Epidermal Sensitisation Assay (EpiSensA) Test Methods; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 396; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiros, P.; Minadakis, V.; Li, D.; Sarimveis, H. Parameter Grouping and Co-Estimation in Physiologically Based Kinetic Models Using Genetic Algorithms. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 200, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, L.M.; Paparella, M.; Burden, N.; Constantine, L.; Margiotta-Casaluci, L.; Miller, T.H.; Moe, S.J.; Owen, S.F.; Schaffert, A.; Sikanen, T. Big Question to Developing Solutions: A Decade of Progress in the Development of Aquatic New Approach Methodologies from 2012 to 2022. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, M.; Krause, S.; Brinkmann, M. Validation of Methods for in Vitro- in Vivo Extrapolation Using Hepatic Clearance Measurements in Isolated Perfused Fish Livers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 12416–12423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | hESCs | hiPSCs | Adult Stem Cells (HSCs, MSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Inner cell mass of human blastocysts (IVF surplus embryos) | Reprogrammed adult somatic cells (fibroblasts, blood, urine) using Yamanaka factors | Bone marrow, peripheral blood (HSCs), adipose or umbilical cord tissue (MSCs) |

| Potency | Pluripotent (all germ layers) | Pluripotent (patient-specific, variable) | Multipotent (restricted to specific tissue lineages) |

| Applications | Developmental toxicity; cardiac, hepatic, neuronal, epithelial, ocular models [101,107] | Cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, developmental neurotoxicity, renal and ocular assays, precision toxicology [113,116,118] | Immunotoxicity, myelotoxicity, biomaterial and nanomaterial cytotoxicity [144,145,147,149] |

| Advantages | Natural pluripotency; reproducible protocols; validated differentiation | Ethically acceptable; scalable; patient-specific | Easy access; ethically uncontroversial; tissue-relevant |

| Limitations | Ethical controversy; limited access; teratoma risk | Variability; incomplete maturation; donor heterogeneity | Limited potency; donor variability; senescence |

| Ethical/Legal | Strict oversight (NIH Registry, EU Directive 2004/23/EC, ISSCR) | Informed consent; data protection (ISSCR 2021) | Standard medical consent; minimal restrictions |

| Method | Primary Inputs | Typical Outputs | Strengths | Common Pitfalls | Use Cases | Key Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR/ read-across | Molecular structures, curated labels | Class or continuous risk | Fast, interpretable | Limited domain, data leakage | Early hazard identification | [204,205,209] |

| ML/AI | Structures + omics/phenotypes | Multi-endpoint predictions | Handles non-linear, multi-task data | Interpretability drift | Portfolio triage, prioritisation | [202,203,210] |

| PBPK | Physiology, ADME parameters | Tissue concentration–time (C(t)) | Human- relevance | Parameter uncertainty | Populations, drug–drug interaction (DDI), exposure assessment | [94,206,207] |

| QIVIVE | In vitro ECx + PBPK | Human-equivalent dose | Translational, mechanistic | Mis-specified clearance | Screening-level risk, potency estimation | [92,93] |

| Tool/Platform | Main Function | Key Advantages | Typical Limitations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Structure-based prediction, read-across | Open-access, regulatory credibility, mechanistic alerts | Limited chemical domain; manual curation required | [204] |

| ProTox 3.0 | Web-based toxicity prediction (ML/QSAR hybrid) | Intuitive interface; wide coverage of endpoints | Dependent on curated training data; black box algorithms | [210] |

| ComptoxAI | AI-assisted chemical hazard modelling | Automated data handling; reproducible pipelines | Model transparency and interpretability challenges | [214] |

| Simcyp Simulator | PBPK/PK–PD modelling, virtual clinical trials | Population variability, organ impairment modules | Requires licenced software; parameter sensitivity | [206] |

| GastroPlus | PBPK-based oral absorption and systemic PK | Physiological realism, QIVIVE capability | Cost, complex calibration | [94] |

| PK-Sim/MoBi | Open-source PBPK modelling suite | Transparency; flexible scripting; reproducible models | Requires expert parameterisation | [207] |