Expression of Selected Pharmacologically Relevant Transporters in Murine Non-Parenchymal Liver Cells Compared to Hepatocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

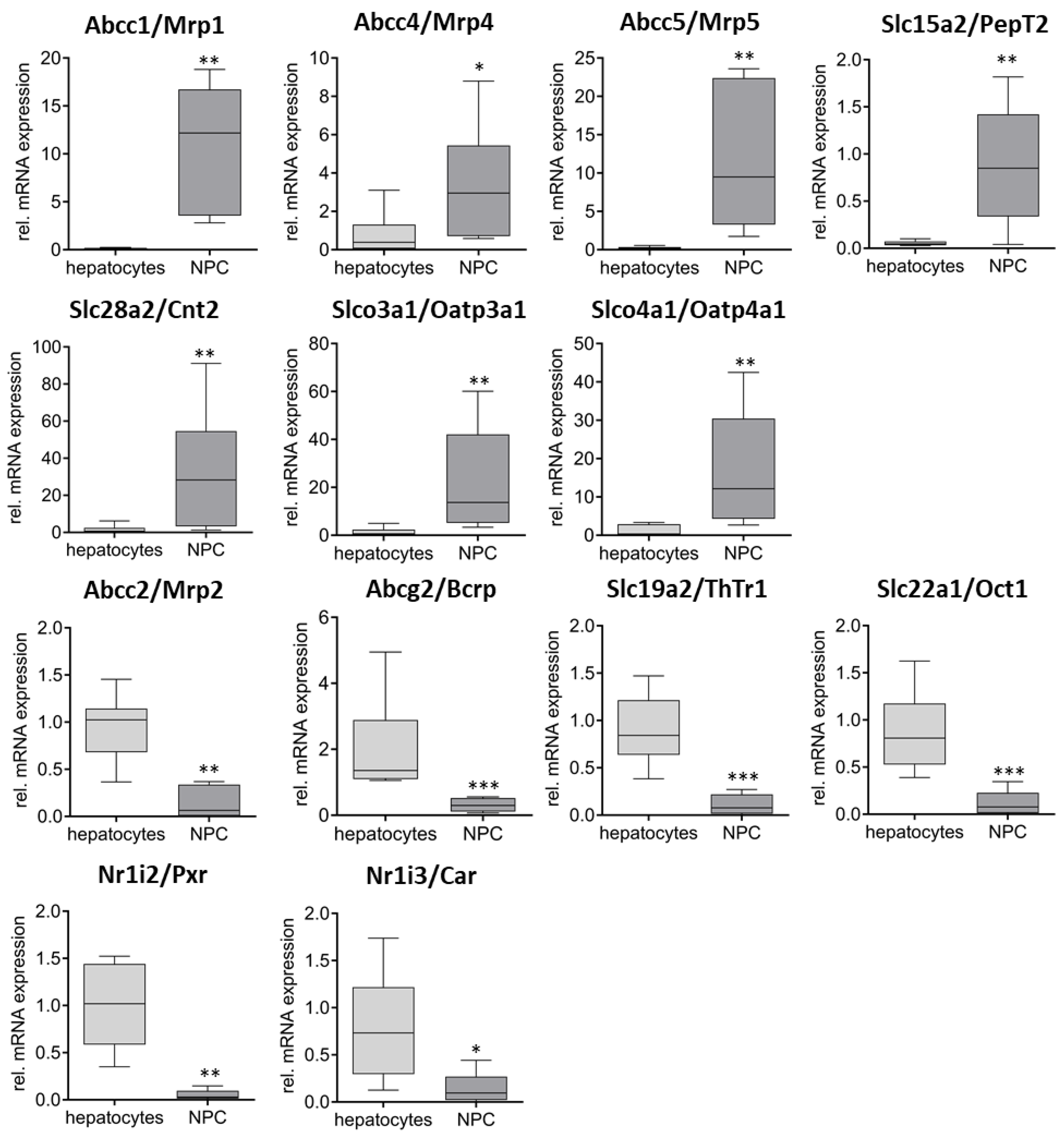

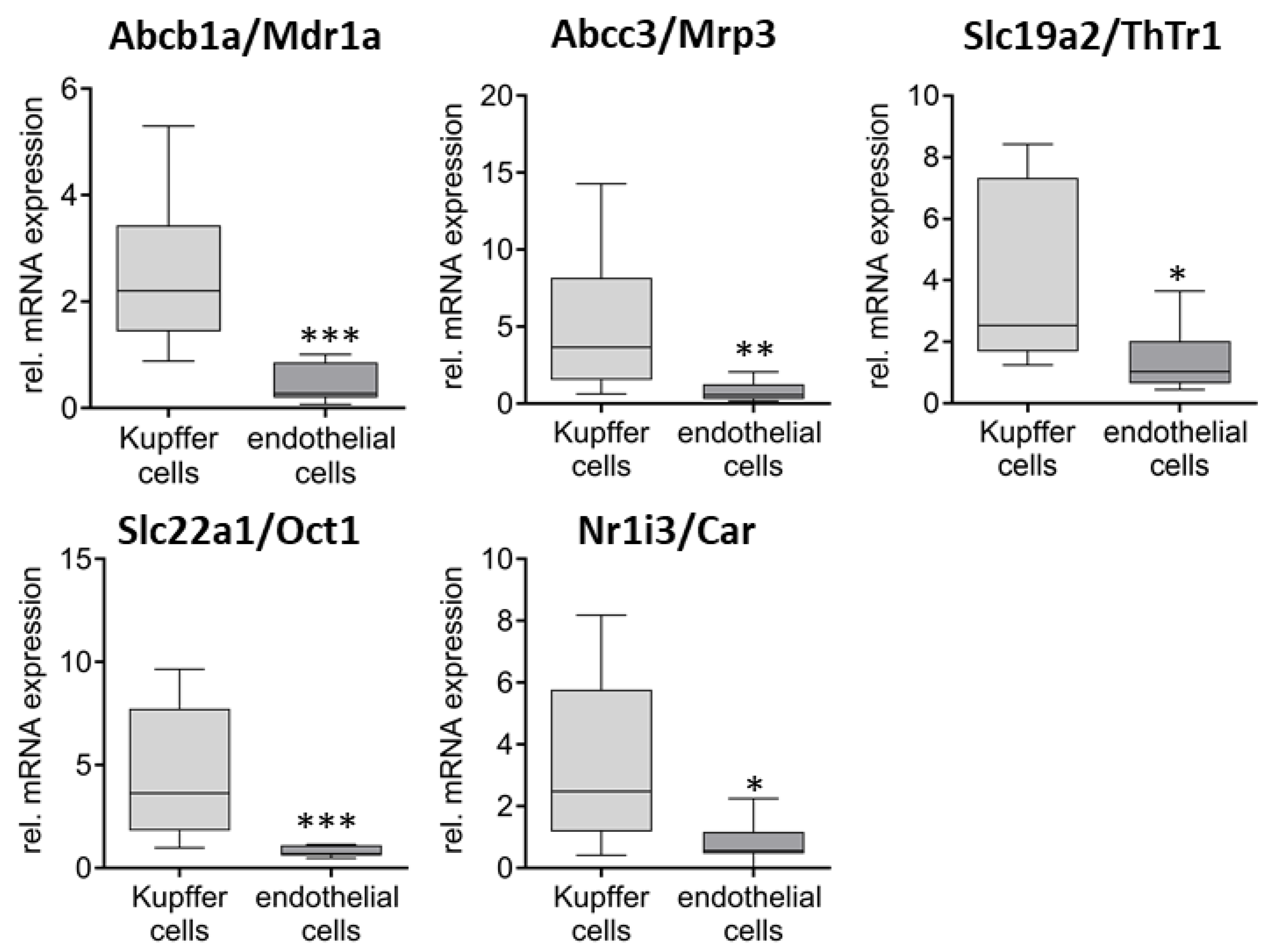

2. Results

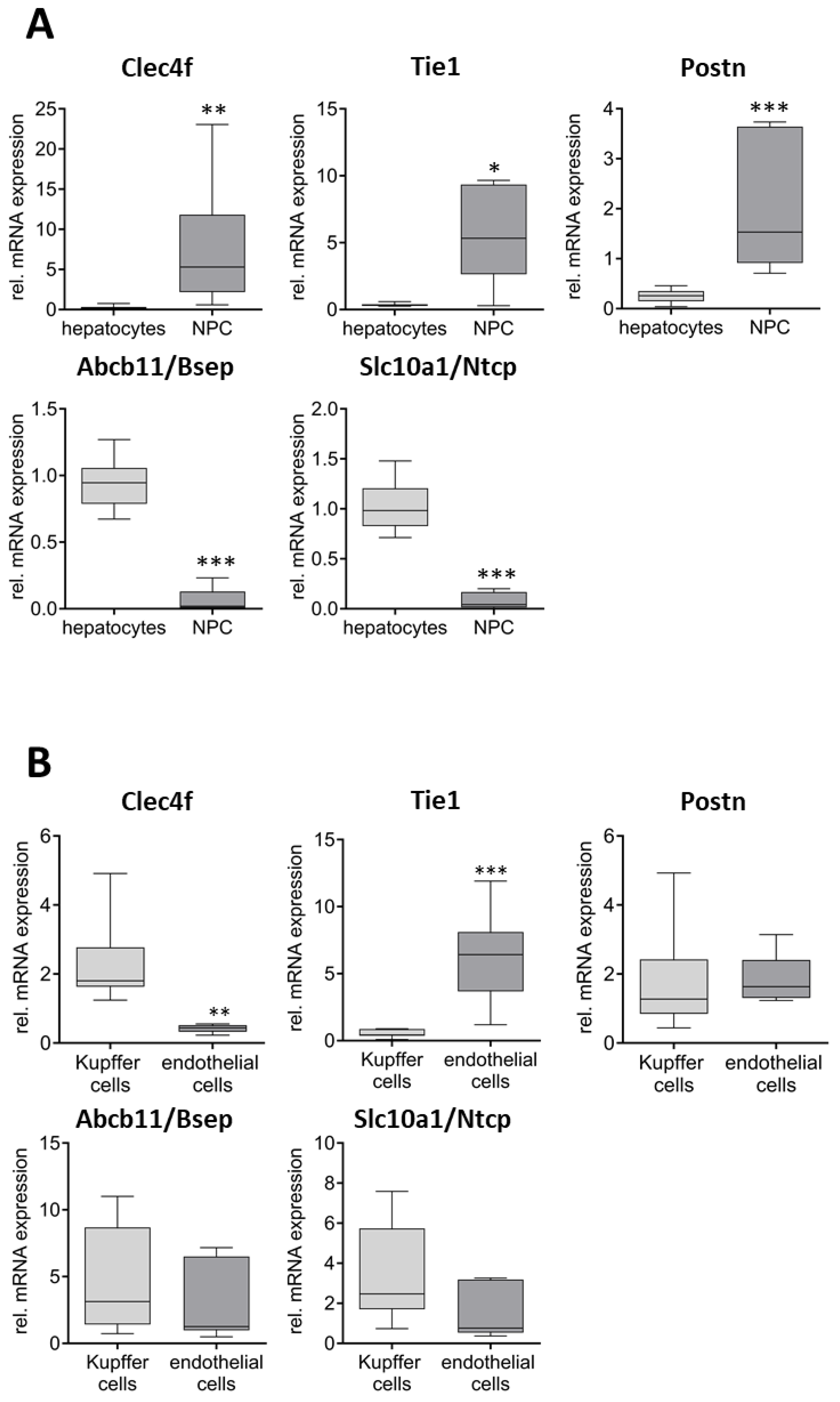

Characterization of the Quality of the Isolated Cell Fractions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Primary Cell Isolation

4.2. Cell Viability

4.3. RNA Expression

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, A.M.; Wheeler, S.E.; Taylor, D.P.; Pillai, V.C.; Young, C.L.; Prantil-Baun, R.; Nguyen, T.; Stolz, D.B.; Borenstein, J.T.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; et al. A microphysiological system model of therapy for liver micrometastases. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014, 239, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmieć, Z. Cooperation of Liver Cells in Health and Disease; (Advances in Anatomy, Embryology, and Cell Biology); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 161, pp. III–XIII, 1–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekemans, K.; Braet, F. Structural and functional aspects of the liver and liver sinusoidal cells in relation to colon carcinoma metastasis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 5095–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, W.; Jeong, W.-I. Hepatic non-parenchymal cells: Master regulators of alcoholic liver disease? World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racanelli, V.; Rehermann, B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology 2006, 43, S54–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang-Lyn, S.; Llerena, V.A. StatPearls: Biochemistry, Biotransformation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. In Vitro Drug Interaction Studies—Cytochrome P450 Enzyme- and Transporter-Mediated Drug Interactions Guidance for Industry; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, R.; Li, F.; Parikh, S.; Cao, L.; Cooper, K.L.; Hong, Y.; Liu, J.; Faris, R.A.; Li, D.; Wang, H. Evaluation of a Novel Renewable Hepatic Cell Model for Prediction of Clinical CYP3A4 Induction Using a Correlation-Based Relative Induction Score Approach. Drug Metab. Dispos. Biol. Fate Chem. 2017, 45, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, M.; Kruijt, J.K.; van Eck, M.; van Berkel, T.J.C. Specific gene expression of ATP-binding cassette transporters and nuclear hormone receptors in rat liver parenchymal, endothelial, and Kupffer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 25448–25453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, N.J.; Lechón, M.J.G.; Houston, J.B.; Hallifax, D.; Brown, H.S.; Maurel, P.; Kenna, J.G.; Gustavsson, L.; Lohmann, C.; Skonberg, C.; et al. Primary hepatocytes: Current understanding of the regulation of metabolic enzymes and transporter proteins, and pharmaceutical practice for the use of hepatocytes in metabolism, enzyme induction, transporter, clearance, and hepatotoxicity studies. Drug Metab. Rev. 2007, 39, 159–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K.M.; Wen, C.C.; Johns, S.J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, S.-M.; Giacomini, K.M. The UCSF-FDA TransPortal: A Public Drug Transporter Database. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 92, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, B.; Hagenbuch, B. Recent advances in understanding hepatic drug transport. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkakoski, P.; Sueyoshi, T.; Negishi, M. Drug-activated nuclear receptors CAR and PXR. Ann. Med. 2003, 35, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudinger, J.L.; Madan, A.; Carol, K.M.; Parkinson, A. Regulation of drug transporter gene expression by nuclear receptors. Drug Metab. Dispos. Biol. Fate Chem. 2003, 31, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudinger, J.L.; Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Hawkins-Brown, D.; MacKenzie, K.I.; LaTour, A.; Liu, Y.; Klaassen, C.D.; Brown, K.K.; Reinhard, J.; et al. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3369–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synold, T.W.; Dussault, I.; Forman, B.M. The orphan nuclear receptor SXR coordinately regulates drug metabolism and efflux. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorga, A.; Dara, L.; Kaplowitz, N. Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Cascade of Events Leading to Cell Death, Apoptosis or Necrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, P.; Hewitt, N.J.; Albrecht, U.; Andersen, M.E.; Ansari, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bode, J.G.; Bolleyn, J.; Borner, C.; Böttger, J.; et al. Recent advances in 2D and 3D in vitro systems using primary hepatocytes, alternative hepatocyte sources and non-parenchymal liver cells and their use in investigating mechanisms of hepatotoxicity, cell signaling and ADME. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1315–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolios, G.; Valatas, V.; Kouroumalis, E. Role of Kupffer cells in the pathogenesis of liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 7413–7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Lefebvre, A.T.; Horuzsko, A. Kupffer Cell Metabolism and Function. J. Enzymol. Metab. 2015, 1, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T.; El-Assal, O.N.; Ono, T.; Yamanoi, A.; Dhar, D.K.; Nagasue, N. Sinusoidal endothelial cell proliferation and expression of angiopoietin/Tie family in regenerating rat liver. J. Hepatol. 2001, 34, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Sun, S.; Wang, K.; Peng, X.; Wang, R.; Li, L.; Zeng, S.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, H. Organic cation transporter 1 mediates the uptake of monocrotaline and plays an important role in its hepatotoxicity. Toxicology 2013, 311, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letschert, K.; Faulstich, H.; Keller, D.; Keppler, D. Molecular characterization and inhibition of amanitin uptake into human hepatocytes. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 2006, 91, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Abt, F.; Faulstich, H.; Hagenbuch, B. Identification of phalloidin uptake systems of rat and human liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1664, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armbrust, T.; Ramadori, G. Functional characterization of two different Kupffer cell populations of normal rat liver. J. Hepatol. 1996, 25, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutam, K.; Ielasi, F.S.; Pardon, E.; Steyaert, J.; Reyes, N. Structural basis of sodium-dependent bile salt uptake into the liver. Nature 2022, 606, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagana, S.M.; Salomao, M.; Remotti, H.E.; Knisely, A.S.; Moreira, R.K. Bile salt export pump: A sensitive and specific immunohistochemical marker of hepatocellular carcinoma. Histopathology 2015, 66, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.I.; Dönmez-Cakil, Y.; Szöllősi, D.; Stockner, T.; Chiba, P. The Bile Salt Export Pump: Molecular Structure, Study Models and Small-Molecule Drugs for the Treatment of Inherited BSEP Deficiencies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, B. The role of the sodium-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) and of the bile salt export pump (BSEP) in physiology and pathophysiology of bile formation. In Drug Transporters; (Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 205–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, C.D.; Cha, E.H.; York, J.D.; Peters, K.G. The endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase Tie1 activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt to inhibit apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 1704–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J.; Armstrong, E.; Mäkelä, T.P.; Korhonen, J.; Sandberg, M.; Renkonen, R.; Knuutila, S.; Huebner, K.; Alitalo, K. A novel endothelial cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase with extracellular epidermal growth factor homology domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Lin, X.-H.; Ma, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, D.-M.; Cui, J.-F.; Chen, R.-X. Periostin involved in the activated hepatic stellate cells-induced progression of residual hepatocellular carcinoma after sublethal heat treatment: Its role and potential for therapeutic inhibition. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiao, H.; Maitikabili, A.; Lin, Q.; Wu, T.; Huang, Z.; Liu, F.; Luo, Q.; Ouyang, G. Matricellular protein periostin contributes to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltiwanger, R.S.; Lehrman, M.A.; Eckhardt, A.E.; Hill, R.L. The distribution and localization of the fucose-binding lectin in rat tissues and the identification of a high affinity form of the mannose/N-acetylglucosamine-binding lectin in rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 7433–7439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Hu, L.-P.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.-L.; Zhang, Z.-G. The physiology, pathology and potential therapeutic application of serotonylation. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs257337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Chen, J.-B.; Tsai, T.-F.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Liang, P.-H.; Hsu, T.-L.; Wu, C.-Y.; Netea, M.G.; Wong, C.-H.; et al. CLEC4F is an inducible C-type lectin in F4/80-positive cells and is involved in alpha-galactosylceramide presentation in liver. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bale, S.S.; Geerts, S.; Jindal, R.; Yarmush, M.L. Isolation and co-culture of rat parenchymal and non-parenchymal liver cells to evaluate cellular interactions and response. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouji, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Moriya, K.; Nishiofuku, M.; Ouji-Sageshima, N.; Matsuda, R.; Nishimura, F.; Ishizaka, S. Isolation and characterization of murine hepatocytes following collagenase infusion into left ventricle of heart. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2010, 110, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knook, D.L.; Blansjaar, N.; Sleyster, E.C. Isolation and characterization of Kupffer and endothelial cells from the rat liver. Exp. Cell Res. 1977, 109, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, E.; Kegel, V.; Zeilinger, K.; Hengstler, J.G.; Nüssler, A.K.; Seehofer, D.; Damm, G. Featured Article: Isolation, characterization, and cultivation of human hepatocytes and non-parenchymal liver cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015, 240, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, E.; Firrincieli, D.; Housset, C.; Chignard, N. Expression patterns of nuclear receptors in parenchymal and non-parenchymal mouse liver cells and their modulation in cholestasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Dial, S.; Shi, L.; Branham, W.; Liu, J.; Fang, J.-L.; Green, B.; Deng, H.; Kaput, J.; Ning, B. Similarities and differences in the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes between human hepatic cell lines and primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. Biol. Fate Chem. 2011, 39, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ölander, M.; Wiśniewski, J.R.; Artursson, P. Cell-type-resolved proteomic analysis of the human liver. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2020, 40, 1770–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Shang, X.; Qin, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, X. Characterization of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1b2 knockout rats generated by CRISPR/Cas9: A novel model for drug transport and hyperbilirubinemia disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, H.; Meyer zu Schwabedissen, H.E.; Tirona, R.G.; Cox, M.L.; Obert, L.A.; Agrawal, N.; Palandra, J.; Stock, J.L.; Kim, R.B.; Ware, J.A. Targeted disruption of murine organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1b2 (Oatp1b2/Slco1b2) significantly alters disposition of prototypical drug substrates pravastatin and rifampin. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, I.; Duflot, S.; Fernández-Veledo, S.; Guillén-Gómez, E.; Huber-Ruano, I.; Casado, F.J.; Pastor-Anglada, M. The concentrative nucleoside transporter family (SLC28): New roles beyond salvage? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005, 33, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karlsson, M.; Zhang, C.; Méar, L.; Zhong, W.; Digre, A.; Katona, B.; Sjöstedt, E.; Butler, L.; Odeberg, J.; Dusart, P.; et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, A.; Le Vee, M.; Jouan, E.; Parmentier, Y.; Fardel, O. Drug transporter expression in human macrophages. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 25, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Li, D.; Tao, L.; Luo, Q.; Chen, L. Solute carrier transporters: The metabolic gatekeepers of immune cells. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.S.; Torres-Vergara, P.; Penny, J. Regulation of the ATP-binding cassette transporters ABCB1, ABCG2 and ABCC5 by nuclear receptors in porcine blood-brain barrier endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, 3092–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.S.; Zerangue, N.; Woodford, K.; Roberts, L.M.; Tate, E.H.; Feng, B.; Li, C.; Feuerstein, T.J.; Gibbs, J.; Smith, B.; et al. Comparative gene expression profiles of ABC transporters in brain microvessel endothelial cells and brain in five species including human. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 59, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabis, G.M.; Kostaki, A.; Andrews, M.H.; Petropoulos, S.; Gibb, W.; Matthews, S.G. Multidrug resistance phosphoglycoprotein (ABCB1) in the mouse placenta: Fetal protection. Biol. Reprod. 2005, 73, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, P.; Schinkel, A.H. P-glycoprotein ABCB1: A major player in drug handling by mammals. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 4131–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, M.; Wanek, T.; Menet, M.-C.; Noack, A.; Declèves, X.; Langer, O.; Löscher, W.; Pahnke, J. Humanization of the Blood-Brain Barrier Transporter ABCB1 in Mice Disrupts Genomic Locus—Lessons from Three Unsuccessful Approaches. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 8, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.P.; Brivio, E.; Santambrogio, A.; de Donno, C.; Kos, A.; Peters, M.; Rost, N.; Czamara, D.; Brückl, T.M.; Roeh, S.; et al. Single-cell molecular profiling of all three components of the HPA axis reveals adrenal ABCB1 as a regulator of stress adaptation. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.J.; Cheng, X.; Weaver, Y.M.; Klaassen, C.D. Tissue Distribution, Gender-Divergent Expression, Ontogeny, and Chemical Induction of Multidrug Resistance Transporter Genes (Mdr1a, Mdr1b, Mdr2) in Mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, J.; Müller, W.H.; Brölsch, C.; Schmidt, F.W. “In vivo” distribution of liposomes between parenchymal and non parenchymal cells in rat liver. Biomedicine 1980, 32, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.; Messner, C.J.; Gaiser, C.; Hämmerli, C.; Suter-Dick, L. Methotrexate-Induced Liver Injury Is Associated with Oxidative Stress, Impaired Mitochondrial Respiration, and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsard, J.; Savary, C.; Massart, J.; Viel, R.; Moutaux, L.; Catheline, D.; Rioux, V.; Clement, B.; Corlu, A.; Fromenty, B.; et al. 3D multi-cell-type liver organoids: A new model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease for drug safety assessments. Toxicol. Vitr. 2024, 94, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granitzny, A.; Knebel, J.; Müller, M.; Braun, A.; Steinberg, P.; Dasenbrock, C.; Hansen, T. Evaluation of a human in vitro hepatocyte-NPC co-culture model for the prediction of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: A pilot study. Toxicol. Rep. 2017, 4, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Kim, S.Y.; Adewale, F.; Zhou, Y.; Aldler, C.; Ni, M.; Wei, Y.; Burczynski, M.E.; Atwal, G.S.; Sleeman, M.W.; et al. Single-cell RNA transcriptome landscape of hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells in healthy and NAFLD mouse liver. iScience 2021, 24, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seglen, P.O. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976, 13, 29–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Zhao, M.; Svensson, K.J. Isolation, culture, and functional analysis of hepatocytes from mice with fatty liver disease. STAR Protoc. 2020, 1, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegel, V.; Deharde, D.; Pfeiffer, E.; Zeilinger, K.; Seehofer, D.; Damm, G. Protocol for Isolation of Primary Human Hepatocytes and Corresponding Major Populations of Non-parenchymal Liver Cells. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2016, 109, e53069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.L.; Schelcher, C.; Demmel, M.; Hauner, M.; Thasler, W.E. Isolation of human hepatocytes by a two-step collagenase perfusion procedure. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2013, 79, e50615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Popova, P.I.; Avdonin, P.P.; Kudryavtsev, I.V.; Serebryakova, M.K.; Korf, E.A.; Avdonin, P.V. Markers of Endothelial Cells in Normal and Pathological Conditions. Biochem. Mosc. Suppl. Ser. A Membr. Cell Biol. 2020, 14, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.H.; Nguyen, V.G.; Tran, C.M.; Nguyen, M.N. Down-regulation of solute carrier family 10 member 1 is associated with early recurrence and poorer prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagawa, K.; Takayama, K.; Isoyama, S.; Tanikawa, K.; Shinkai, M.; Harada, K.; Tachibana, M.; Sakurai, F.; Noguchi, E.; Hirata, K.; et al. Generation of a bile salt export pump deficiency model using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rönnpagel, V.; Ullrich, A.; Joseph, C.; Tzvetkov, M.V.; Runge, D.; Grube, M. Expression of Selected Pharmacologically Relevant Transporters in Murine Non-Parenchymal Liver Cells Compared to Hepatocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211116

Rönnpagel V, Ullrich A, Joseph C, Tzvetkov MV, Runge D, Grube M. Expression of Selected Pharmacologically Relevant Transporters in Murine Non-Parenchymal Liver Cells Compared to Hepatocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211116

Chicago/Turabian StyleRönnpagel, Vincent, Anett Ullrich, Christy Joseph, Mladen V. Tzvetkov, Dieter Runge, and Markus Grube. 2025. "Expression of Selected Pharmacologically Relevant Transporters in Murine Non-Parenchymal Liver Cells Compared to Hepatocytes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211116

APA StyleRönnpagel, V., Ullrich, A., Joseph, C., Tzvetkov, M. V., Runge, D., & Grube, M. (2025). Expression of Selected Pharmacologically Relevant Transporters in Murine Non-Parenchymal Liver Cells Compared to Hepatocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211116