Analysis of Transcript Expression and Core Promoter DNA Sequences of Brain, Adipose Tissues and Testis in Human and Fruit Fly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Expression Patterns and Tissue Specificity of Human and Drosophila Tissues

2.1.1. A Considerable Portion of Transcripts Are Showing Tissue Enrichment in Both Human and Drosophila

2.1.2. Investigating Tissue Specificity Revealed an Extreme Number of Testis Enriched Transcripts

2.1.3. Expression Patterns Are More Conserved in Human

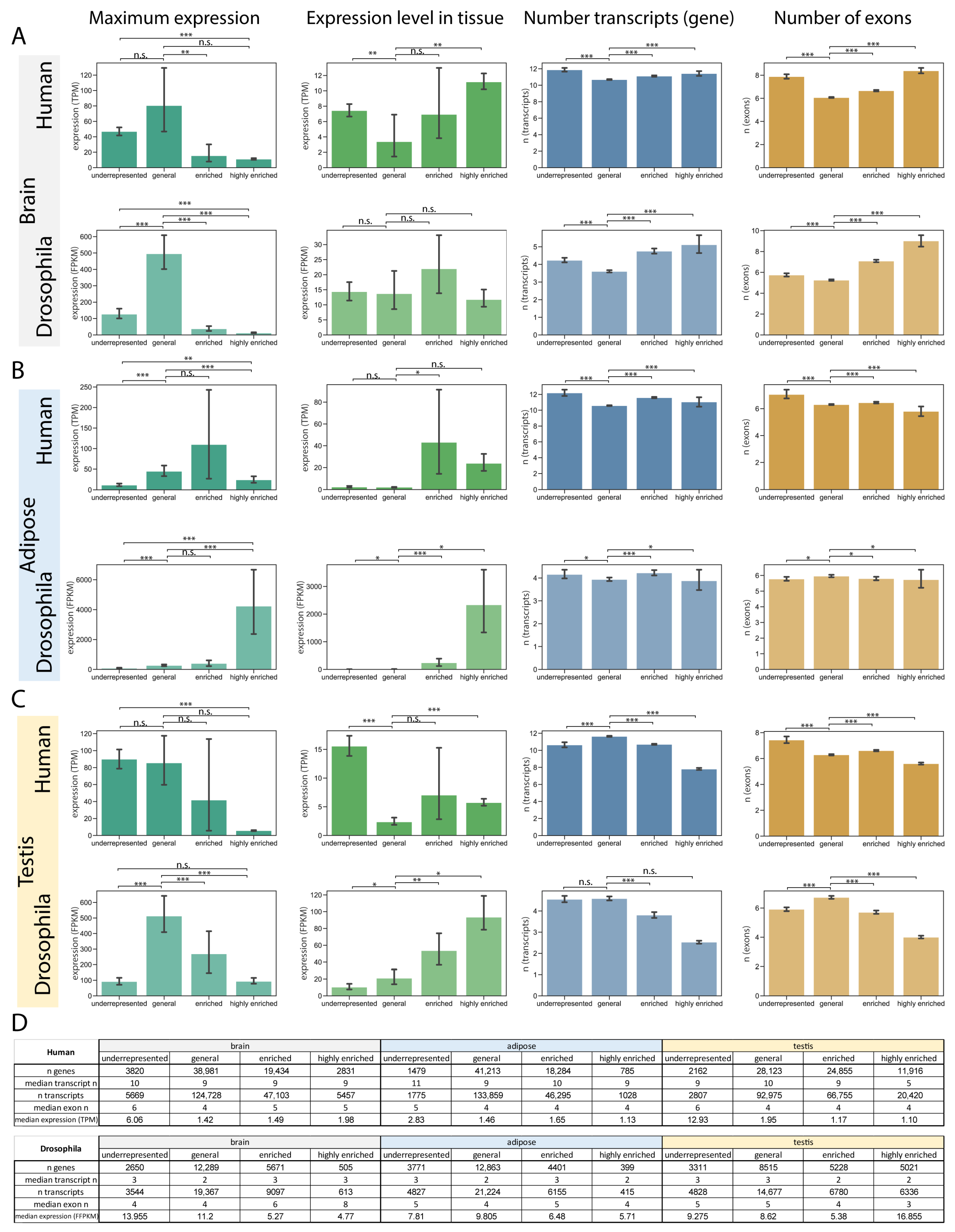

2.2. Transcript and Gene Characteristics Change Within Specificity Groups

2.2.1. Brain Characteristics Revealed More Complex Gene Structures Among Genes with Highly Enriched Transcripts

2.2.2. Transcripts Enriched in Adipose Tissue Have Higher Expression in the Tissue

2.2.3. Genes with Testis-Enriched Transcripts Have Simpler Genomic Organisation in Both Human and Drosophila

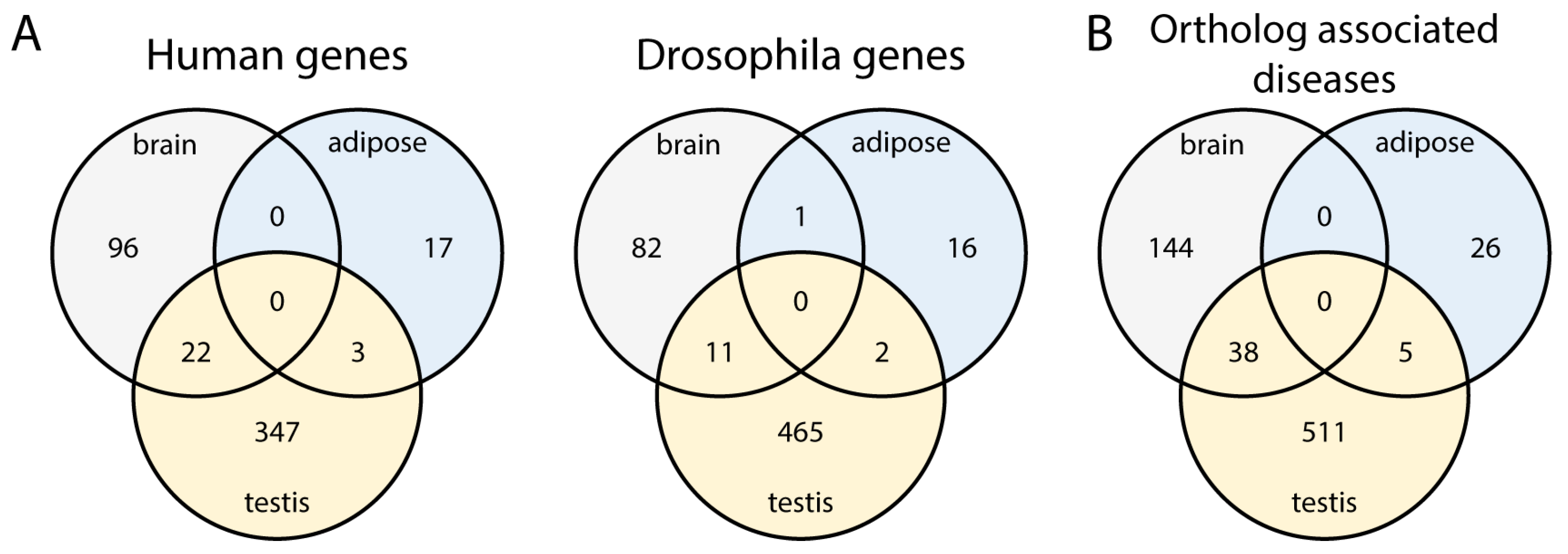

2.3. Investigating Orthologous Genes with Enriched Transcripts Between Human and Drosophila

2.3.1. Orthologues in Human and Drosophila Have a Similar Expression Pattern Only in Adipose Tissue

2.3.2. Orthologous Genes May Have Highly Enriched Transcripts in Multiple Tissues

2.3.3. Orthologous Genes with Highly Enriched Transcripts Could Serve as Disease Models

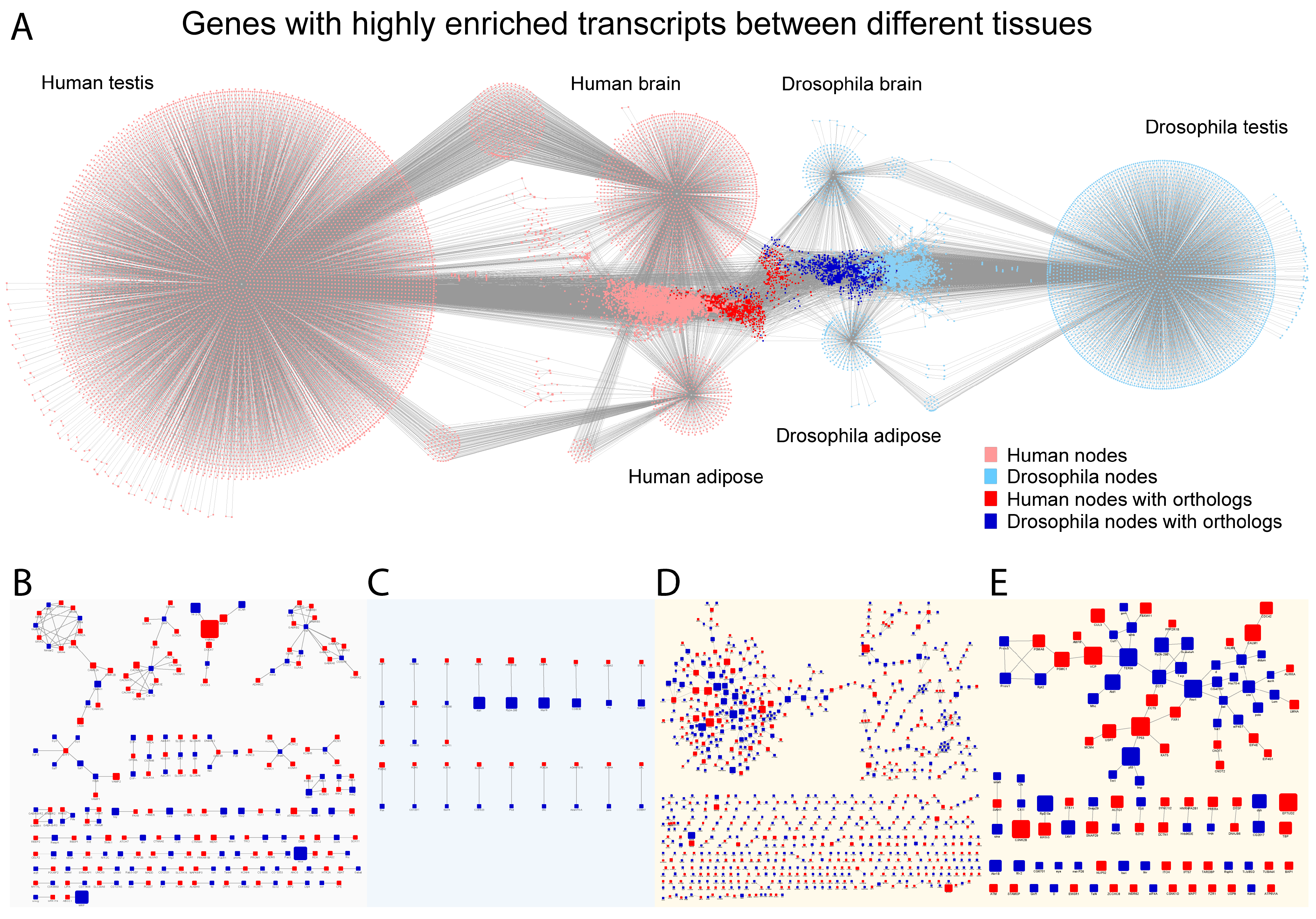

2.4. Network Analysis Revealed Conserved Central Elements Are Present in All Tissues

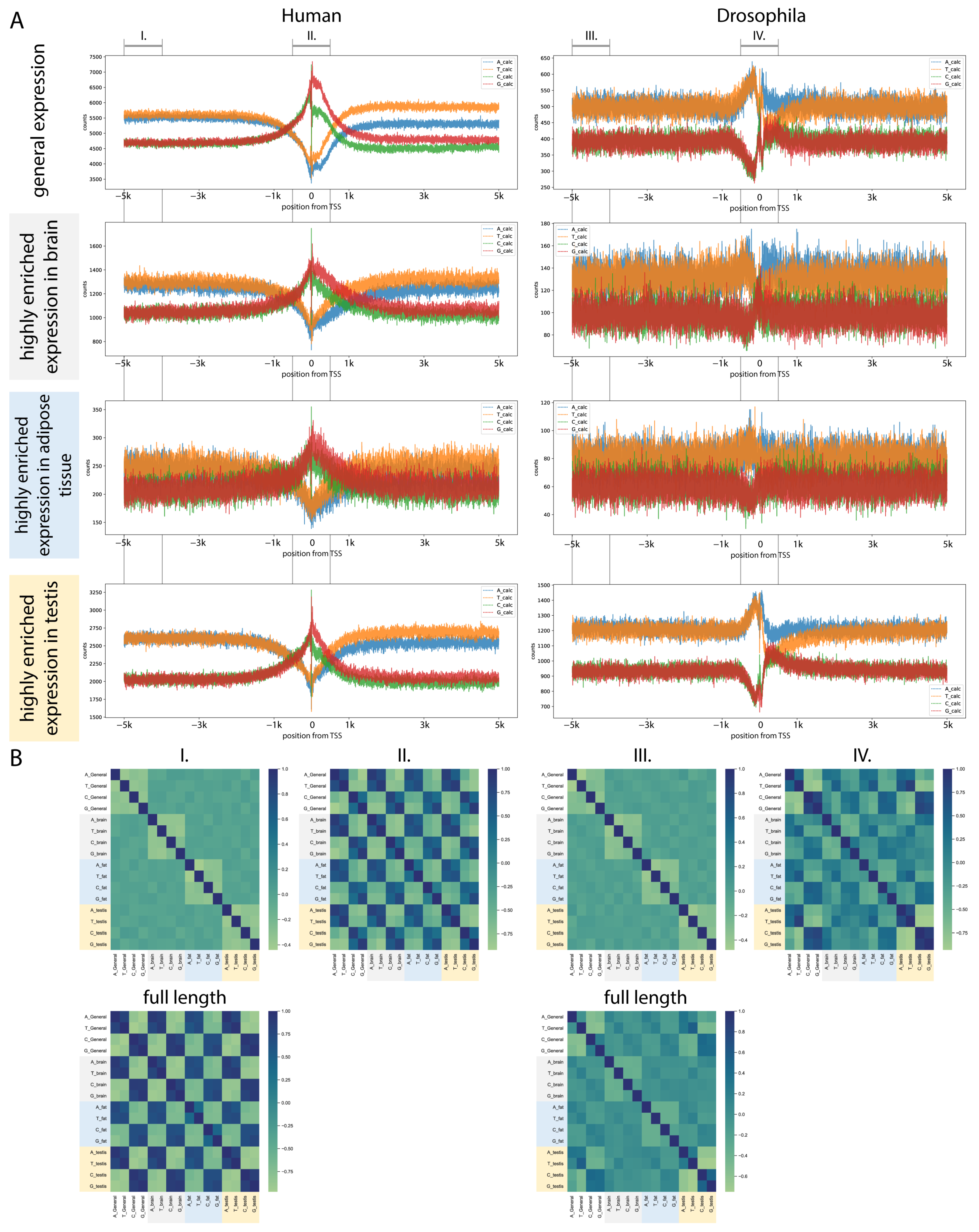

2.5. Sequence Analysis of Enriched Transcripts Showed Characteristic Patterns

2.5.1. Transcriptional Start Site Regions Show Characteristic ATGC Content

2.5.2. Human TSS Shows High Similarity Between Tissues

2.5.3. The TSS of Drosophila Tissue-Enriched Transcripts Show Different ATGC Profiles Between Tissues

2.5.4. ATGC Profile of Non-Coding RNA TSS Varies in Drosophila Testis

2.6. Differentially Enriched Motifs Are Present in the TSS Region of Enriched Transcripts

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source and Preparation

4.2. Gene Ontology Analysis

4.3. Network Analysis

4.4. Transcription Start Sites and Motif Analysis

4.5. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hill, M.S.; Vande Zande, P.; Wittkopp, P.J. Molecular and Evolutionary Processes Generating Variation in Gene Expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coniglio, J.G. Testicular Lipids. Prog. Lipid Res. 1994, 33, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurinyecz, B.; Péter, M.; Vedelek, V.; Kovács, A.L.; Juhász, G.; Maróy, P.; Vígh, L.; Balogh, G.; Sinka, R. Reduced Expression of CDP-DAG Synthase Changes Lipid Composition and Leads to Male Sterility in Drosophila. Open Biol. 2016, 6, 150169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, S.; Williamson, C.; Bevan, C.L. Liver X Receptors and Male (In)Fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.F.; Pesch, Y.-Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, C.; Aristizabal, M.J.; Huan, T.; Tanentzapf, G.; Rideout, E.J. An Important Role for Triglyceride in Regulating Spermatogenesis. eLife 2024, 12, RP87523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, T.J.; Steyn, F.J.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Ngo, S.T. Neuronal Lipid Metabolism: Multiple Pathways Driving Functional Outcomes in Health and Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, S.; Ying, J.; Hua, F. Lipid Metabolism and Storage in Neuroglia: Role in Brain Development and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Moreira, M.; Halbert, J.; Valloton, D.; Velten, B.; Chen, C.; Shao, Y.; Liechti, A.; Ascenção, K.; Rummel, C.; Ovchinnikova, S.; et al. Gene Expression across Mammalian Organ Development. Nature 2019, 571, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantica, F.; Iñiguez, L.P.; Marquez, Y.; Permanyer, J.; Torres-Mendez, A.; Cruz, J.; Franch-Marro, X.; Tulenko, F.; Burguera, D.; Bertrand, S.; et al. Evolution of Tissue-Specific Expression of Ancestral Genes across Vertebrates and Insects. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Wu, H.; Lee, K. Integrative Analysis Revealing Human Adipose-Specific Genes and Consolidating Obesity Loci. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.-X.; Li, H.-T.; Gu, Y.; Sun, X. Brain-Specific Gene Expression and Quantitative Traits Association Analysis for Mild Cognitive Impairment. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Omae, Y.; Kakita, A.; Gabdulkhaev, R.; Hitomi, Y.; Miyagawa, T.; Honda, M.; Fujimoto, A.; Tokunaga, K. Identification of Region-Specific Gene Isoforms in the Human Brain Using Long-Read Transcriptome Sequencing. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, S.K.; Guda, C. Global Gene Expression Profiling of Healthy Human Brain and Its Application in Studying Neurological Disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Osorio, D.; Guan, J.; Ji, G.; Cai, J.J. Overdispersed Gene Expression in Schizophrenia. npj Schizophr. 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Xie, G.; Jiang, X.; Khaitovich, P.; Han, D.; Liu, X. Epigenetic Regulation of Human-Specific Gene Expression in the Prefrontal Cortex. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babenko, V.; Redina, O.; Smagin, D.; Kovalenko, I.; Galyamina, A.; Kudryavtseva, N. Brain-Region-Specific Genes Form the Major Pathways Featuring Their Basic Functional Role: Their Implication in Animal Chronic Stress Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, A.T.; Wang, M.; Hauberg, M.E.; Fullard, J.F.; Kozlenkov, A.; Keenan, A.; Hurd, Y.L.; Dracheva, S.; Casaccia, P.; Roussos, P.; et al. Brain Cell Type Specific Gene Expression and Co-Expression Network Architectures. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, J.; Aibar, S.; Taskiran, I.I.; Ismail, J.N.; Gomez, A.E.; Aughey, G.; Spanier, K.I.; De Rop, F.V.; González-Blas, C.B.; Dionne, M.; et al. Decoding Gene Regulation in the Fly Brain. Nature 2022, 601, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, K.; Janssens, J.; Koldere, D.; De Waegeneer, M.; Pech, U.; Kreft, Ł.; Aibar, S.; Makhzami, S.; Christiaens, V.; Bravo González-Blas, C.; et al. A Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of the Aging Drosophila Brain. Cell 2018, 174, 982–998.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacrinò, A.; Brengdahl, M.I.; Kimber, C.M.; Mital, A.; Shenoi, V.N.; Mirabello, C.; Friberg, U. Ageing Desexualizes the Drosophila Brain Transcriptome. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20221115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaessmann, H. Origins, Evolution, and Phenotypic Impact of New Genes. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S.; Vedanayagam, J.; Mohammed, J.; Eizadshenass, S.; Kan, L.; Pang, N.; Aradhya, R.; Siepel, A.; Steinhauer, J.; Lai, E.C. New Genes Often Acquire Male-Specific Functions but Rarely Become Essential in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurinyecz, B.; Vedelek, V.; Kovács, A.L.; Szilasi, K.; Lipinszki, Z.; Slezák, C.; Darula, Z.; Juhász, G.; Sinka, R. Sperm-Leucylaminopeptidases Are Required for Male Fertility as Structural Components of Mitochondrial Paracrystalline Material in Drosophila melanogaster Sperm. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedelek, V.; Laurinyecz, B.; Kovács, A.L.; Juhász, G.; Sinka, R. Testis-Specific Bb8 Is Essential in the Development of Spermatid Mitochondria. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzyoud, E.; Vedelek, V.; Réthi-Nagy, Z.; Lipinszki, Z.; Sinka, R. Microtubule Organizing Centers Contain Testis-Specific γ-TuRC Proteins in Spermatids of Drosophila. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 727264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beall, E.L.; Lewis, P.W.; Bell, M.; Rocha, M.; Jones, D.L.; Botchan, M.R. Discovery of tMAC: A Drosophila Testis-Specific Meiotic Arrest Complex Paralogous to Myb–Muv B. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 904–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanov, A.V.; Barcenilla-Merino, D.; Loppin, B.; Fyodorov, D.V. APOLLO, a Testis-Specific Drosophila Ortholog of Importin-4, Mediates the Loading of Protamine-like Protein Mst77F into Sperm Chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Wu, M.; Sun, A.; Wu, X.; Zheng, J.; Shi, W.; Gao, G. Broad Phosphorylation Mediated by Testis-Specific Serine/Threonine Kinases Contributes to Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, M.-R.; Suh, Y.; Lee, H.; Hwang, S.; Mamuad, L.L.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, K. A Novel Testis-Enriched Gene, Samd4a, Regulates Spermatogenesis as a Spermatid-Specific Factor. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 978343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morohoshi, A.; Miyata, H.; Tokuhiro, K.; Iida-Norita, R.; Noda, T.; Fujihara, Y.; Ikawa, M. Testis-Enriched Ferlin, FER1L5, Is Required for Ca2+-Activated Acrosome Reaction and Male Fertility. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Cao, C.; Zhuang, C.; Luo, X.; Li, X.; Wan, H.; Ye, J.; Chen, F.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. AXDND1, a Novel Testis-Enriched Gene, Is Required for Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneda, Y.; Miyata, H.; Shimada, K.; Oyama, Y.; Iida-Norita, R.; Ikawa, M. IRGC1, a Testis-Enriched Immunity Related GTPase, Is Important for Fibrous Sheath Integrity and Sperm Motility in Mice. Dev. Biol. 2022, 488, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Messina, G.; Lehner, C.F. Nuclear Elongation during Spermiogenesis Depends on Physical Linkage of Nuclear Pore Complexes to Bundled Microtubules by Drosophila Mst27D. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Yabuta, N.; Shimada, K.; Mashiko, D.; Tokuhiro, K.; Oyama, Y.; Miyata, H.; Garcia, T.X.; Matzuk, M.M.; Ikawa, M. Individual Disruption of 12 Testis-Enriched Genes via the CRISPR/Cas9 System Does Not Affect the Fertility of Male Mice. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2024, 163, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellil, H.; Ghieh, F.; Hermel, E.; Mandon-Pepin, B.; Vialard, F. Human Testis-Expressed (TEX) Genes: A Review Focused on Spermatogenesis and Male Fertility. Basic Clin. Androl. 2021, 31, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, J.W.; Koster, J.; Lodder, P.; Repping, S.; Hamer, G. Massive Expression of Germ Cell-Specific Genes Is a Hallmark of Cancer and a Potential Target for Novel Treatment Development. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5694–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenpreisa, J.; Vainshelbaum, N.M.; Lazovska, M.; Karklins, R.; Salmina, K.; Zayakin, P.; Rumnieks, F.; Inashkina, I.; Pjanova, D.; Erenpreiss, J. The Price of Human Evolution: Cancer-Testis Antigens, the Decline in Male Fertility and the Increase in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.L.; Fonseca, A.F.; Fonseca, M.; da Silva, T.E.; Coelho, A.C.; Kroll, J.E.; de Souza, J.E.S.; Stransky, B.; de Souza, G.A.; de Souza, S.J. Genome-Wide Identification of Cancer/Testis Genes and Their Association with Prognosis in a Pan-Cancer Analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 92966–92977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmins, S.; Kotaja, N.; Davidson, I.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Testis-Specific Transcription Mechanisms Promoting Male Germ-Cell Differentiation. Reproduction 2004, 128, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C. Control of Human Testis-Specific Gene Expression. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsch, T.J.; Dubuisson, O.; Johnson, A.E.; Bohnert, K.A. VCP Promotes tTAF-Target Gene Expression and Spermatocyte Differentiation by Downregulating Mono-Ubiquitylated H2A. Development 2023, 150, dev201557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Nurminsky, D.I. Evidence for a Hierarchical Transcriptional Circuit in Drosophila Male Germline Involving Testis-Specific TAF and Two Gene-Specific Transcription Factors, Mod and Acj6. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevaraju, S.; Fear, J.M.; Akeju, M.; Galletta, B.J.; Pinheiro, M.M.L.S.; Avelino, C.C.; Cabral-de-Mello, D.C.; Conlon, K.; Dell’Orso, S.; Demere, Z.; et al. Dynamic Sex Chromosome Expression in Drosophila Male Germ Cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.H.; Hansen, A.S. Enhancer Selectivity in Space and Time: From Enhancer–Promoter Interactions to Promoter Activation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 574–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloutskin, A.; Shir-Shapira, H.; Freiman, R.N.; Juven-Gershon, T. The Core Promoter Is a Regulatory Hub for Developmental Gene Expression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 666508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danino, Y.M.; Even, D.; Ideses, D.; Juven-Gershon, T. The Core Promoter: At the Heart of Gene Expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gene Regul. Mech. 2015, 1849, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberle, V.; Stark, A. Eukaryotic Core Promoters and the Functional Basis of Transcription Initiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, P. Organization and Regulation of Gene Transcription. Nature 2019, 573, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, F.; Gasch, A.; Kaltschmidt, B.; Renkawitz-Pohl, R. A 14 Bp Promoter Element Directs the Testis Specificity of the Drosophila beta 2 Tubulin Gene. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, K.-F.; Pan, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Lin, W. Top-Ranked Expressed Gene Transcripts of Human Protein-Coding Genes Investigated with GTEx Dataset. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, A.; Marygold, S.J.; Antonazzo, G.; Attrill, H.; dos Santos, G.; Garapati, P.V.; Goodman, J.L.; Gramates, L.S.; Millburn, G.; Strelets, V.B.; et al. FlyBase: Updates to the Drosophila melanogaster Knowledge Base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D899–D907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzàlez-Porta, M.; Frankish, A.; Rung, J.; Harrow, J.; Brazma, A. Transcriptome Analysis of Human Tissues and Cell Lines Reveals One Dominant Transcript per Gene. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, B.B.; Karczewski, K.J.; Kosmicki, J.A.; Seaby, E.G.; Watts, N.A.; Singer-Berk, M.; Mudge, J.M.; Karjalainen, J.; Satterstrom, F.K.; O’Donnell-Luria, A.H.; et al. Transcript Expression-Aware Annotation Improves Rare Variant Interpretation. Nature 2020, 581, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.Y.; Kim, H.U.; Lee, S.Y. Human Genes with a Greater Number of Transcript Variants Tend to Show Biological Features of Housekeeping and Essential Genes. Mol. BioSyst. 2015, 11, 2798–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ule, J.; Blencowe, B.J. Alternative Splicing Regulatory Networks: Functions, Mechanisms, and Evolution. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralle, F.E.; Giudice, J. Alternative Splicing as a Regulator of Development and Tissue Identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, J.; Gu, C.; Yang, Y. Alternative Splicing and Cancer: A Systematic Review. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedelek, V.; Kovács, A.L.; Juhász, G.; Alzyoud, E.; Sinka, R. The Tumor Suppressor Archipelago E3 Ligase Is Required for Spermatid Differentiation in Drosophila Testis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, N.T.; Moberg, K.H. The Archipelago Ubiquitin Ligase Subunit Acts in Target Tissue to Restrict Tracheal Terminal Cell Branching and Hypoxic-Induced Gene Expression. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arama, E.; Bader, M.; Rieckhof, G.E.; Steller, H. A Ubiquitin Ligase Complex Regulates Caspase Activation During Sperm Differentiation in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.V.; Buchwalter, R.A.; Kao, L.-R.; Megraw, T.L. A Splice Variant of Centrosomin Converts Mitochondria to Microtubule-Organizing Centers. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 1928–1940.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedelek, V.; Bodai, L.; Grézal, G.; Kovács, B.; Boros, I.M.; Laurinyecz, B.; Sinka, R. Analysis of Drosophila Melanogaster Testis Transcriptome. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Huang, H.; Bickel, P.J.; Brenner, S.E. Comparison of D. Melanogaster and C. Elegans Developmental Stages, Tissues, and Cells by modENCODE RNA-Seq Data. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1086–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurisch-Yaksi, N.; Wachten, D.; Gopalakrishnan, J. The Neuronal Cilium—A Highly Diverse and Dynamic Organelle Involved in Sensory Detection and Neuromodulation. Trends Neurosci. 2024, 47, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, P.C.; Sturgill, D.; Shyakhtenko, A.; Oliver, B.; Vinson, C. Comparative Genomics of Drosophila and Human Core Promoters. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.; Ewing, B.; Miller, W.; Thomas, P.J.; Green, E.D. NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Transcription-Associated Mutational Asymmetry in Mammalian Evolution. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinckenbosch, N.; Dupanloup, I.; Kaessmann, H. Evolutionary Fate of Retroposed Gene Copies in the Human Genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3220–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.C.; Dupanloup, I.; Vinckenbosch, N.; Reymond, A.; Kaessmann, H. Emergence of Young Human Genes after a Burst of Retroposition in Primates. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorus, S.; Freeman, Z.N.; Parker, E.R.; Heath, B.D.; Karr, T.L. Recent Origins of Sperm Genes in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Betrán, E.; Thornton, K.; Long, M. Retroposed New Genes Out of the X in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 1854–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; He, H.; Zhou, Q. On the Origin and Evolution of Drosophila New Genes during Spermatogenesis. Genes 2021, 12, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, L. The Origin and Structural Evolution of de Novo Genes in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, E.; Benjamin, S.; Svetec, N.; Zhao, L. Testis Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals the Dynamics of de Novo Gene Transcription and Germline Mutational Bias in Drosophila. eLife 2019, 8, e47138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus-McQuillan, J.E.; Nanni, A.V.; McIntyre, L.M.; Rogers, R.L. Estimating Transcriptome Complexities across Eukaryotes. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bush, S.J.; Tovar-Corona, J.M.; Castillo-Morales, A.; Urrutia, A.O. Correcting for Differential Transcript Coverage Reveals a Strong Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Organism Complexity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, B.; Schnappauf, G.; Thoma, F. Poly(dA.dT) Sequences Exist as Rigid DNA Structures in Nucleosome-Free Yeast Promoters in Vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 4083–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, A.; Muskhelishvili, G. DNA Structure and Function. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2279–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harteis, S.; Schneider, S. Making the Bend: DNA Tertiary Structure and Protein-DNA Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12335–12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naro, C.; Cesari, E.; Sette, C. Splicing Regulation in Brain and Testis: Common Themes for Highly Specialized Organs. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Gleeson, J.G. Cilia in the Nervous System: Linking Cilia Function and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011, 24, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, I.; Boulianne, G.L. Modeling Obesity and Its Associated Disorders in Drosophila. Physiology 2013, 28, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musselman, L.P.; Kühnlein, R.P. Drosophila as a Model to Study Obesity and Metabolic Disease. J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 221, jeb163881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfa, R.W.; Kim, S.K. Using Drosophila to Discover Mechanisms Underlying Type 2 Diabetes. Dis. Models Mech. 2016, 9, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brattig-Correia, R.; Almeida, J.M.; Wyrwoll, M.J.; Julca, I.; Sobral, D.; Misra, C.S.; Di Persio, S.; Guilgur, L.G.; Schuppe, H.-C.; Silva, N.; et al. The Conserved Genetic Program of Male Germ Cells Uncovers Ancient Regulators of Human Spermatogenesis. eLife 2024, 13, RP95774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, D.P.; Krause, S.A.; Pandit, A.; Davies, S.A.; Dow, J.A.T. FlyAtlas 2: A New Version of the Drosophila Melanogaster Expression Atlas with RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq and Sex-Specific Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D809–D815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Flockhart, I.; Vinayagam, A.; Bergwitz, C.; Berger, B.; Perrimon, N.; Mohr, S.E. An Integrative Approach to Ortholog Prediction for Disease-Focused and Other Functional Studies. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, D.; Tegenfeldt, F.; Manni, M.; Seppey, M.; Berkeley, M.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. OrthoDB V11: Annotation of Orthologs in the Widest Sampling of Organismal Diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D445–D451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Korhonen, T. DIOPT: Extremely Fast Classification Using Lookups and Optimal Feature Discretization. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lindskog, C. The Human Protein Atlas—An Important Resource for Basic and Clinical Research. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2016, 13, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.D.; Ebert, D.; Muruganujan, A.; Mushayahama, T.; Albou, L.-P.; Mi, H. PANTHER: Making Genome-Scale Phylogenetics Accessible to All. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Muruganujan, A.; Casagrande, J.T.; Thomas, P.D. Large-Scale Gene Function Analysis with the PANTHER Classification System. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H. The PANTHER Database of Protein Families, Subfamilies, Functions and Pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 33, D284–D288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Morris, J.H.; Demchak, B.; Bader, G.D. Biological Network Exploration with Cytoscape 3. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014, 47, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AltschuP, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vedelek, V.; Ochieng, P.J.; Vágvölgyi, A.; Nagy, O.; Zádori, J.; Sinka, R. Analysis of Transcript Expression and Core Promoter DNA Sequences of Brain, Adipose Tissues and Testis in Human and Fruit Fly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211114

Vedelek V, Ochieng PJ, Vágvölgyi A, Nagy O, Zádori J, Sinka R. Analysis of Transcript Expression and Core Promoter DNA Sequences of Brain, Adipose Tissues and Testis in Human and Fruit Fly. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211114

Chicago/Turabian StyleVedelek, Viktor, Peter Juma Ochieng, Anna Vágvölgyi, Olga Nagy, János Zádori, and Rita Sinka. 2025. "Analysis of Transcript Expression and Core Promoter DNA Sequences of Brain, Adipose Tissues and Testis in Human and Fruit Fly" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211114

APA StyleVedelek, V., Ochieng, P. J., Vágvölgyi, A., Nagy, O., Zádori, J., & Sinka, R. (2025). Analysis of Transcript Expression and Core Promoter DNA Sequences of Brain, Adipose Tissues and Testis in Human and Fruit Fly. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211114