Abstract

Interleukin 17 (IL-17) is a crucial mediator at the interface of periodontal dysbiosis and host immunity. This review synthesizes current evidence on IL-17 in periodontitis (PD), its systemic connections, and the role of IL-17 gene variants. Clinical and experimental studies show that IL-17 rises in periodontal disease and is associated with the severity of PD via action on epithelial, stromal and osteoblastic cells to promote chemokine release, neutrophil recruitment, cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2 synthesis, RANKL expression, osteoclastogenesis, and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Periodontopathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans pre-activate the local inflammation-maintaining Th17 response. There is converging evidence linking IL-17-centered signaling with rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis in favor of a shared inflammatory network in barrier tissues and synovium. Despite these associations, IL-17 biology is contextually determined with mucosal defense and bone homeostatic roles that caution against unidimensional explanations. Evidence on IL-17A and IL-17F polymorphisms is still heterogeneous across populations with modest and variable risk associations with PD. Clinically, IL-17 in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, or serum is a potential monitoring biomarker when utilized along with conventional indices. Therapeutically, periodontal therapy that reduces microbial burden may inhibit IL-17 function, and IL-17-targeted therapy has to balance potential benefit to inflammation and bone resorption against safety in oral tissues. The following research must utilize harmonized case definitions, standardized sampling, and multiethnic cohorts, and it must include multiomics to be able to differentiate between causal and compensatory IL-17 signals.

1. Introduction

Periodontitis (PD) is a complex and increasingly common disease, affecting many adults. It is well established that supra and subgingival biofilms provoke an inflammatory and immune response in the body [1]. The hypernym “periodontal diseases” includes all pathological processes that affect the periodontium, gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. In most diseased patients, periodontal diseases manifest as gingivitis or its irreversible deuteropathy, PD, which is caused by the increased accumulation of dental plaque. Although these account for a large proportion of periodontal diseases, one should not ignore the fact that viral infections, tumors and multiple other insults may lead to destructive processes affecting the periodontium. Bearing this in mind, it also seems quite logical that the cause may range from a simple, unifactorial agent, like a herpes simplex virus, to compound, multifactorial bacteria and host immune system-mediated dysbiosis [2].

Gingivitis is defined as clinical gingival inflammation and is easy to diagnose with the help of numerous indices, including bleeding on probing (BOP) as the gold standard [3]. While gingivitis is known to be fully reversible, it can, if not treated in time, progress to the irreversible state of PD. PD is primarily defined as the pathological loss of periodontal ligament, which is measurable as clinical attachment loss (CAL), and loss of alveolar bone, which is measurable as radiographical bone loss (RBL) [4]. PD is an inflammatory disease. Its primary cause is of bacterial origin. Pathologic bacteria, especially those of Socransky’s red complex (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola), initiate destructive processes in the periodontium [1]. Both the number of these bacteria and the immune response of the diseased host determine the disease entity. Previous studies have proven that “appropriate” cytokine production results in protective immunity, whereas “inappropriate” cytokine production leads to tissue destruction and disease progression [5]. Several pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to play a pathogenic role in different systemic inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis (RA). IL-17 is proven to be associated with bone destruction in PD [6].

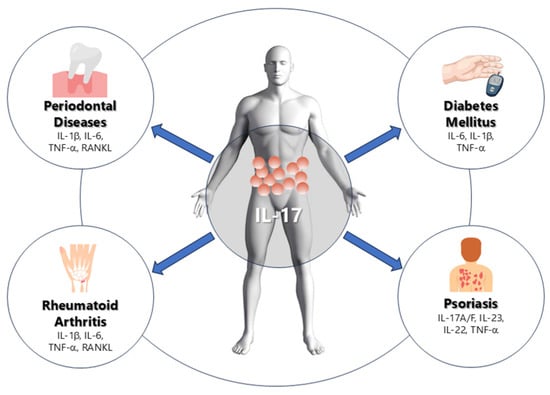

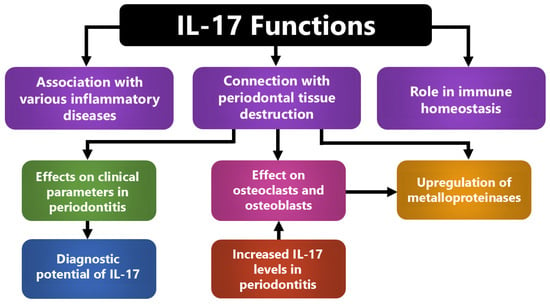

Due to its effect on other systemic diseases, IL-17 and its single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been included in medical research concerning the etiology and progression of PD. The elevation or reduction in IL-17 is associated with an alteration in the severity and progression of periodontal diseases, especially of PD [7]. IL-17 is secreted by a variety of innate and adaptive immune cells. After its secretion, inflammatory cascade reactions take place and mediate the initiation and progress of PD and other systemic diseases. Understanding interactions between multiple diseases including PD and, for example, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and diabetes mellitus on a molecular basis (including the role of IL-17—Figure 1) will help dentists and physicians improve their clinical diagnosis and treatment options [7]. Bearing in mind that diagnostic tests that display IL-17 levels (serum, gingival crevicular fluid (GCF)) are nowadays easy and cheap to obtain and given its proven effect on PD at different levels, IL-17 may play an increasingly pivotal role in diagnostics and treatment approaches (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the role of IL-17 in periodontal and systemic inflammation. IL-17 mediates the relationship between periodontal disease, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis through the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and RANKL, leading to bone resorption, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation.

Figure 2.

Integrated roles of IL-17 in periodontal inflammation and host–tissue interactions. IL-17 coordinates inflammatory and homeostatic responses by linking immune activation with periodontal tissue destruction. It enhances cytokine and metalloproteinase production, stimulates osteoclast and osteoblast activity, and contributes to systemic inflammatory signaling. These combined actions explain its association with clinical disease severity and its potential as a diagnostic biomarker.

Recent global estimates indicate continued growth in the absolute burden of periodontal diseases through 2040, largely driven by population aging and growth, with persistent regional disparities [8]. Contemporary cytokine syntheses position IL-17 as a nodal mediator of periodontal pathogenesis and a potential therapeutic target that interfaces with precision care [9]. At the same time, emerging work underscores a context-dependent role for IL-17 in mucosal defense and bone homeostasis, which suggests that biomarker use and any IL-17 focused strategies should balance pathogenic and protective functions [10].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the role of IL-17 in the development of periodontitis and its systemic relevance. It summarizes current knowledge on IL-17 expression and function in periodontal tissues, its contribution to inflammation-driven tissue destruction, and its involvement in the relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis. By integrating recent scientific evidence, this review underscores the significance of IL-17 as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in both periodontal and systemic inflammation.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane up to May 2025, using combinations of the following keywords: IL-17, periodontitis, cytokines, systemic inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis. Reference lists of relevant articles were also screened manually. Screening was performed manually based on title and abstract relevance. Original research studies, reviews, and meta-analyses addressing IL-17 expression, function, or genetic polymorphisms in periodontal and systemic diseases were included. Studies not published in English or lacking relevance to IL-17-mediated mechanisms were excluded. Although no formal quality appraisal tool was applied, study design, sample size, and diagnostic criteria were considered to minimize selection bias. Methodological variability and unadjusted confounders were noted, and a brief overview of these factors is presented in the “Study limitations/notes” column of Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarized characteristics of included studies.

2. IL-17 as Pro-Inflammatory Marker in Periodontitis

IL-17 is a key T-cell derived cytokine with diverse functions in periodontal tissues [24]. It acts on endothelial cells, fibroblasts and epithelial cells, stimulating them to produce chemokines and pro-inflammatory mediators. Among IL-17-producing cells, CD4+ T cells are the most relevant [11].

While IL-17 contributes to host defense and mucosal homeostasis, prolonged production can amplify inflammation and tissue damage [28]. Mitani et al. demonstrated that IL-17 promotes periodontal tissue destruction by inducing receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) on CD4+ T cells, thereby enhancing osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption [14]. Similar mechanisms underlie other chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and asthma [12].

Clinical studies consistently show elevated IL-17 in PD. Mitani et al. reported significantly higher IL-17A in gingival crevicular fluid of patients compared with healthy controls [14]. Vernal et al. found a correlation between IL-17 levels and radiographic bone loss, which is mediated by IL-17 induced cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis and RANKL expression in osteoblasts [11,29]. IL-17 also upregulates matrix metalloproteinases, further driving connective tissue breakdown [24]. More pronounced increases are observed in PD, where persistent IL-17 cascades sustain destructive inflammation [14,23,26].

Periodontal pathogens contribute directly to this response. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans stimulate monocytes, enhancing Th17 differentiation and IL-17 production [28]. A recent systematic review confirmed that Th17-related biomarkers, including IL-17, are consistently elevated in PD, supporting their pathogenic role [30].

Isoform specific analyses further refine this picture. Mazurek-Mochol et al. showed that IL-17A expression in gingival tissue correlated with plaque index, whereas IL-17B expression was reduced at the mRNA level in PD patients but correlated positively with CAL, suggesting post-translational regulation [24]. Wankhede et al. similarly reported correlations between IL-17 and CAL and probing depth in aggressive PD [23]. More recently, Altaca et al. demonstrated higher IL-17 levels in gingival crevicular fluid of patients with stage III, IV PD, confirming its association with disease severity [26].

Systematic reviews of the IL-23–IL-17 axis reinforce the diagnostic value of IL-17 in gingival crevicular fluid [29]. Meanwhile, genetic epidemiology offers a more nuanced view: higher genetically predicted IL-17 levels may not uniformly increase PD risk, suggesting potential protective or compensatory roles [31].

When the findings from studies summarized in Table 1 are compared, a general trend emerges: IL-17 concentrations are elevated in the gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, and serum of patients with periodontitis compared to healthy individuals. However, not all reports are consistent. Studies with small sample sizes, variable periodontal classifications, and unadjusted confounders such as smoking or diabetes often failed to detect significant differences. These discrepancies highlight methodological heterogeneity and suggest that IL-17 more accurately reflects local inflammatory burden rather than disease severity itself. Although several studies consistently report elevated IL-17 levels in periodontitis, others have not found statistically significant differences between diseased and healthy sites. Such inconsistencies likely reflect methodological variation, including differences in sample sources (gingival crevicular fluid vs. serum), disease classification criteria, and detection assays. Additionally, biological variability—such as local cytokine compartmentalization or the influence of systemic conditions—may modulate measurable IL-17 concentrations. Together, these factors highlight the importance of standardized protocols and confounder adjustment when interpreting cytokine data in periodontal research.

Overall, IL-17 appears to act as a key modulator at the interface between microbial challenge, host immune response, and periodontal tissue destruction. Its levels in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva and serum correlate with clinical parameters and disease severity, supporting its use as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker [23,24,26,30,31]. Importantly, recent work also highlights IL-17’s dual nature: it drives destructive osteoclastogenesis yet contributes to mucosal defense and bone homeostasis, underscoring the complexity of IL-17 targeted therapeutic strategies [10].

3. Relation Between IL-17 in Periodontitis and Other Systemic Diseases

Systemic diseases, including PD, are linked through shared risk factors and converging inflammatory pathways. Conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus increase susceptibility to destructive periodontal diseases [32]. Although the precise mechanisms are not fully understood, they display overlapping features suggesting common etiological routes [33].

Pro-inflammatory interleukins, particularly IL-17, act as central mediators connecting PD with systemic inflammatory diseases. IL-17 triggers intracellular signaling cascades including NF-κB, MAPK, and JAK/STAT, which stimulate the production of secondary cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β. These cascades amplify inflammation both locally in periodontal tissues and systemically, creating feedback loops that exacerbate tissue destruction and contribute to systemic inflammatory burden. Dysregulated IL-17 signaling promotes the recruitment and activation of neutrophils and osteoclasts, linking bone loss in PD with systemic pathologies [7,12]. The shared pathways among PD, autoimmune, and metabolic diseases suggest that IL-17-centered networks serve as a molecular bridge, unifying disparate systemic conditions through common inflammatory mechanisms [34]. Its activity promotes osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction, which are processes that are observed in PD and bone-related systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [12]. Elevated IL-17 levels have been consistently associated with worse periodontal and systemic outcomes, making it a potential therapeutic target.

Recent work has reinforced these connections. Feng et al. highlighted IL-17A as a central mediator bridging PD with systemic chronic inflammatory diseases, where dysregulated IL-17 signaling contributes to both local tissue breakdown and systemic inflammatory burden [7]. Neurath et al. further demonstrated that cytokines including IL-17 not only sustain gingival inflammation but also disseminate systemically, exacerbating comorbidities and offering potential targets for therapy [9]. Hasan et al. summarized evidence that systemic health is tightly linked to periodontal inflammation with IL-17 acting as one of the pivotal messengers driving this association [34].

Taken together, these findings confirm that IL-17 is not confined to local periodontal pathology but plays a broader role in systemic inflammatory networks. By explicitly connecting intracellular signaling, immune cell recruitment, cytokine amplification, and systemic inflammation, IL-17 demonstrates how PD and systemic diseases are mechanistically intertwined. Its dual involvement underscores the importance of monitoring IL-17 levels in clinical practice and considering periodontal, systemic interactions when designing preventive and therapeutic strategies.

3.1. IL-17 and Rheumatoid Arthritis

PD and rheumatoid arthritis are distinct diseases, yet they share inflammatory circuits that canter on dysregulated cytokines, including IL-17. Th17 responses amplify synovitis, osteoclastogenesis and matrix degradation, which mirror tissue breakdown in PD [7,35].

Mechanistically, IL-17 acts on synovial fibroblasts and stromal cells, induces RANKL and matrix metalloproteinases, and cooperates with TNF and IL-6, which accelerates bone erosion and cartilage damage in rheumatoid arthritis [35]. Contemporary tissue atlases of rheumatoid arthritis synovium reveal inflammatory subtypes and cellular neighborhoods that include Th17-related programs and cytokine responsive stromal states, which is a framework that helps explain variable responses to targeted therapy [36].

Clinical and immunologic data support IL-17 as a disease activity signal. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis show expanded pathogenic Th17 and Th22 subsets, and higher IL-17 associates with composite activity scores [37,38]. Systemic links with PD are also evident. Rheumatoid arthritis cohorts have an increased prevalence of periodontal disease, and serum IL-17 can be higher in rheumatoid arthritis patients who also have PD compared with PD alone, which points to additive systemic inflammation [13,39].

Therapeutically, rheumatoid arthritis treatment that reduces IL-17-driven inflammation can coincide with improved periodontal parameters, and periodontal care may attenuate the systemic inflammatory burden in rheumatoid arthritis [7,39]. Single cell profiling under TNF or JAK inhibition shows shifts in pathogenic cell states in synovial fluid, consistent with cytokine pathway modulation, which may include IL-17-linked programs [40]. Overall, IL-17 is a mechanistic bridge between periodontal and synovial pathology, which supports coordinated management that addresses oral inflammation and systemic immune drivers.

3.2. IL-17 and Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a major chronic inflammatory metabolic disease, and its effects on bone include higher fracture risk and osteolytic lesions that resemble those in PD [41]. Because the two conditions share inflammatory drivers, including Th17 responses, many studies have examined IL-17 as a biomarker to track disease activity and therapy outcomes [41,42].

Mechanistically, diabetes can magnify periodontal inflammation through several routes. Hyperglycemia shifts immune cell programs, increases the Th17 to Treg ratio, and fuels cytokine production, which promotes osteoclastogenesis and connective tissue breakdown in the periodontium [41,42]. Conceptual models of the diabetes–PD axis now explicitly include IL-17 as a contributor to increased periodontal dysbiosis and a heightened host response [42].

Clinical data increasingly support elevated IL-17 in diabetic PD. Inflammatory profiling shows that patients with PD plus type 2 diabetes have stronger systemic and local inflammatory signatures than PD alone with panels that include IL-17 among other mediators [25]. Gingival crevicular fluid studies also report higher IL-17 with concentrations tracking clinical severity [22]. These observations align with a broader framework in which diabetes enhances inflammatory bone loss through IL-17-linked pathways [41].

Genetic and biomarker studies provide a nuanced picture. IL-17A and IL-17F are produced by Th17 cells, and polymorphisms within these loci have been explored. In type 1 diabetes with chronic PD, IL-17A gene variability was associated with immune readouts and microbial patterns, although clinical correlations were limited [16]. Salivary biomarker work in type 2 diabetes and PD suggests that IL-17 can increase with both conditions, sometimes in an additive fashion [18]. The overall message is mixed rather than contradictory. Some cohorts emphasize periodontal status as the primary driver of salivary IL-17, while others show higher IL-17 levels when diabetes and PD coexist [18,22,25].

Taken together, IL-17 sits at the intersection of diabetic inflammation and periodontal tissue destruction. Its measurement in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, or serum can complement clinical parameters when assessing risk and treatment response in patients with diabetes who also have PD [22,25,41,42].

3.3. IL-17 and Psoriasis

Psoriasis is driven by the IL-23–IL-17 axis with IL-17A and IL-17F promoting keratinocyte activation, neutrophil recruitment and sustained cutaneous inflammation [43]. Within this pathway, multiple IL-17 family members, receptors and downstream programs shape disease severity and therapeutic response, which explains the effectiveness of IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors in clinical practice [43].

Links to periodontal pathology are increasingly recognized. Narrative and systematic overviews report a higher prevalence and severity of PD in psoriatic cohorts along with shared immune features that include elevated IL-17 signaling and related mediators [44,45]. A preclinical model supports bidirectionality, ligature-induced PD aggravated psoriasiform inflammation and, conversely, psoriasiform inflammation worsened periodontal breakdown, which is consistent with a systemic inflammatory loop that features Th17–IL-17 pathways [44]. Clinical studies that profile inflammatory markers further suggest that psoriatic patients show correlations between cytokines, including IL-17, and periodontal indices, reinforcing the concept of a common inflammatory network [46].

Overall, IL-17 functions as a mechanistic bridge between psoriasis and PD. It amplifies epithelial, stromal and myeloid responses in the skin, and it participates in osteoclastogenic, matrix-degrading cascades in periodontal tissues. Monitoring IL-17-related biomarkers and coordinating dermatologic with periodontal care may improve outcomes in patients with coexisting disease [43,44,45,46].

Synthesizing the data summarized in Table 2, patients affected by both periodontitis and systemic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis, tend to exhibit higher IL-17 levels than those with either condition alone. This reinforces the concept of a shared inflammatory axis linking oral and systemic immunity. Nevertheless, discrepancies between studies likely arise from variations in systemic disease control, medication regimens, and cytokine detection methods.

Table 2.

Summary of results.

4. IL-17 Polymorphisms in Periodontitis

Polymorphisms in IL-17A and IL-17F can modulate cytokine expression or function, which may alter susceptibility to PD and influence disease severity. The most studied variants are IL-17A rs2275913 and IL-17F rs763780.

4.1. IL-17A rs2275913

Evidence is mixed across populations. A recent systematic review of the IL-23–IL-17 axis catalogued variants in IL-17A–IL-17F–IL-17 receptors and IL-23R, and it reported that only a subset of studies linked rs2275913 to PD with substantial heterogeneity by ancestry and case definitions [47]. A meta-analysis focused on rs2275913 did not show a consistent overall association with chronic PD, although subgroup signals varied and likely reflected sample size and confounding factors such as smoking and diabetes [48]. Primary studies also diverge with some reporting higher risk in A carrying genotypes and others finding null or trend-level effects [15,21,49,50,51].

4.2. IL-17F rs763780

Findings are similarly inconsistent. In a well-characterized European cohort, rs763780 and rs2275913 were not associated with PD overall, and stratification by smoking did not reveal robust effects despite small allele frequency shifts [52]. Other case control analyses suggest population-specific links and possible interaction with the subgingival microbiome, but sample sizes are modest and require replication [53,54].

The variability in reported associations across ethnicities likely reflects differences in allele frequencies and linkage disequilibrium structures among populations. Environmental and lifestyle factors such as smoking, glycemic control, and microbial composition may further interact with IL-17 gene variants, modifying their effect on cytokine expression and disease susceptibility. These gene–environment interactions help explain the inconsistent findings between populations and highlight the importance of studying IL-17 genetics in diverse, well-characterized cohorts.

When variants across the IL-23–IL-17 pathway are considered together, the aggregate signal for PD risk is modest. A broad cytokine polymorphism review and meta-analysis concluded that compared with IL-1 family variants, IL-17 polymorphisms show weaker and less consistent relationships with PD, with heterogeneity and possible publication bias that limit clinical translation at present [55]. A cross-disease meta-analysis likewise did not find a uniform effect of IL-17A and IL-17F variants for PD, underscoring the importance of population context and phenotype definition [33].

4.3. Clinical Implications

IL-17A and IL-17F genotyping should not be used alone for risk prediction. A pragmatic approach is to consider these variants within a multifactorial matrix together with clinical parameters, environmental exposures such as smoking, and protein level biomarkers—for example, IL-17 in gingival crevicular fluid or saliva. Larger, multiethnic studies with harmonized case definitions and rigorous confounder control are needed to clarify population-specific effects and gene–environment interactions [15,21,33,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55].

5. Discussion

This review summarizes current evidence indicating that IL-17 may play a modulatory role in the interaction between periodontal dysbiosis, immune activation, and tissue destruction. While IL-17 is consistently elevated in periodontal and systemic inflammatory conditions, its causal role remains unconfirmed and requires further mechanistic investigation. Across clinical and experimental studies, IL-17 aligns with periodontal severity and bone loss and sits at the interface between oral and systemic inflammation [7,26,29]. Its biology is dependent on context. IL-17 can support mucosal defense and barrier integrity, while persistent or amplified signaling drives osteoclastogenesis, matrix degradation, and collateral tissue damage [7,56].

Collectively, current findings outline a mechanistic framework in which IL-17 serves as a hub linking microbial dysbiosis to host-mediated tissue injury and systemic immune activation. Through the stimulation of macrophages, fibroblasts, and osteoblasts, IL-17 amplifies IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and RANKL signaling, resulting in osteoclast differentiation and connective-tissue degradation. The same cytokine network propagates inflammatory signals systemically, creating a shared IL-17-driven axis across periodontal and extra-oral diseases. This integrative mechanism is illustrated in Figure 1.

From a biomarker perspective, IL-17 measured in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, or serum associates with disease presence and activity. Cross-sectional data in stage III and IV PD show higher IL-17 with worse clinical indices, and axis level syntheses confirm consistently elevated IL-17 in periodontal disease compared with health [26,29]. Isoform-specific work adds nuance. In gingival tissue, IL-17A and IL-17B show divergent patterns at mRNA and protein levels with post-translational regulation likely contributing to the observed protein increases in disease [24]. Genetic epidemiology provides a cautious note. An instrumental variable analysis suggested that higher genetically proxied IL-17 is not uniformly associated with greater PD risk, and Mendelian randomization work points to specific circulating immune cell phenotypes as causal drivers of PD, which is a framework that helps separate causal from compensatory IL-17 signals [31,57].

Microbial drivers of the Th17–IL-17 axis remain central. Key periodontopathogens stimulate monocytes and favor Th17 differentiation, which amplifies local cytokine networks and recruits neutrophils, creating a self-reinforcing inflammatory loop [28]. This loop helps explain why IL-17 aligns with connective tissue breakdown and radiographic bone loss through COX-2, PGE2, and RANKL pathways in stromal and osteoblastic compartments [11]. At the molecular level, IL-17 promotes osteoclastogenesis and matrix degradation through the activation of STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in stromal and osteoblastic cells. Engagement of the IL-17 receptor triggers the downstream expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and RANKL, which collectively enhance osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption [6,7,12]. Moreover, IL-17 acts synergistically with IL-23 and TNF-α to sustain these inflammatory cascades, amplifying tissue destruction in advanced periodontal lesions [7,11,56].

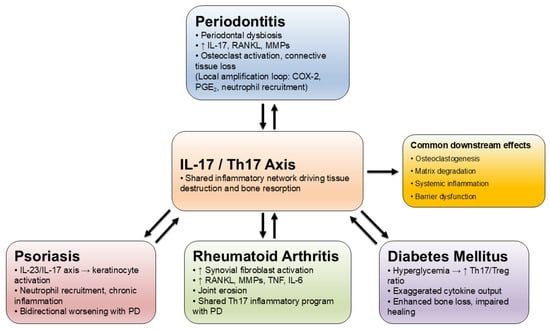

Together, these findings define a cyclical mechanism in which microbial challenge initiates IL-17 signaling, host genetics modulate its intensity, and tissue biomarkers reflect its clinical consequences. Systemic connections are increasingly clear. Reviews integrating oral and systemic data position IL-17 as a mediator that can disseminate inflammatory signals beyond the periodontium, aligning with epidemiologic links to rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and psoriasis [9,31]. In rheumatoid arthritis, IL-17 cooperates with TNF and IL-6 to promote synovial fibroblast activation, RANKL upregulation, and erosive damage with synovial tissue atlases identifying Th17-related inflammatory neighborhoods that may modulate treatment response [13,35,36]. In diabetes, hyperglycemia can skew the Th17 to Treg balance and amplify cytokine output, which aligns with higher local and systemic inflammatory signatures in patients who have both diabetes and PD, although cohort findings vary in magnitude and biomarker panels [25,41,42]. In psoriasis, the IL-23–IL-17 axis drives keratinocyte and myeloid activation. Epidemiology and preclinical models support bidirectional aggravation between skin and periodontal inflammation, which is consistent with a shared Th17 program across barrier tissues [43,44,45].

The polymorphism literature is less conclusive. Meta-analyses and axis-level reviews indicate modest and inconsistent associations between IL-17A rs2275913 or IL-17F rs763780 and PD with substantial heterogeneity by ancestry, case definitions, and environmental exposures such as smoking and glycemic control [47,48,51,55]. These data argue against the clinical translation of single-variant genotyping and support composite risk assessment that integrates clinical indices, exposures, and soluble biomarkers.

Therapeutic implications follow from this biology. Periodontal care that reduces microbial load and inflammatory burden should down-tune IL-17-centered pathways locally and possibly systemically. Emerging data suggest that non-surgical periodontal therapy can modulate IL-17 in gingival crevicular fluid, with patterns influenced by smoking status, which supports the use of IL-17 as a treatment responsive biomarker [27]. In systemic disease, IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors are effective in psoriasis, while effects are variable in rheumatoid arthritis. Any exploration of IL-17-targeted strategies for PD should balance potential benefits for inflammation and bone resorption with risks related to mucosal defense and candidiasis, given safety observations from the dermatologic use of IL-17 blockade [58], and the documented dual roles of IL-17 in experimental models and human observational studies [7,43,56]. The inhibition of IL-17 can impair mucosal immunity, predisposing to mucocutaneous candidiasis and other opportunistic infections. Moreover, IL-17 contributes to normal tissue repair and epithelial barrier maintenance; therefore, its suppression may delay wound healing and weaken host defense at oral and mucosal sites. These observations underline the need for careful evaluation before extending IL-17-targeted therapy to periodontal settings [7,43,56,58].

Collective findings point to a central role of IL-17 in coordinating interactions between microbial, genetic, and immune factors. Through its dual function in promoting local tissue destruction and amplifying systemic inflammation, IL-17 provides a mechanistic link between periodontitis and related chronic inflammatory diseases (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Common IL-17-centered pathways linking periodontitis with systemic diseases.

Despite the growing body of evidence linking IL-17 with periodontal and systemic inflammation, current studies are constrained by heterogeneity in design, limited sample sizes, and inconsistent periodontal classification systems. Variations in diagnostic criteria, cytokine detection methods, and the presence of systemic comorbidities such as diabetes or smoking complicate comparisons and may partially explain discrepancies among studies. The absence of uniform adjustment for these confounders further limits the interpretability of IL-17 findings. Future research should address these limitations by adopting harmonized case definitions, standardized sampling and assays, and longitudinal study designs. Multiethnic cohorts with rigorous confounder control and gene–environment interaction testing will be essential to clarify causal mechanisms and to validate IL-17 as a reliable biomarker and therapeutic target. Moreover, most available data are observational, which limits the ability to establish causality between IL-17 expression and disease outcomes. Associations observed in cross-sectional and case-control studies may reflect compensatory immune responses rather than direct pathogenic effects. Longitudinal and interventional studies, ideally integrating multiomics and mechanistic models, are required to determine whether IL-17 acts as a causal driver or as a secondary marker of inflammation. Pragmatically, the most immediate use of IL-17 is as part of a composite monitoring strategy, alongside bleeding on probing, pocket depth, CAL, and radiographic assessment, particularly in patients with comorbid rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, or psoriasis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-M. and A.P.; Supervision, M.M.-M.; Writing, original draft, T.B., M.M., E.B., L.J., A.P., J.R.-S., M.L. and M.M.-M.; Writing, review and editing, M.M. and M.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AgP | aggressive periodontitis |

| BI | bleeding index |

| CAL | clinical attachment loss |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CP | chronic periodontitis |

| Del-1 | developmental endothelial locus-1 |

| F | female |

| FBG | fasting blood glucose |

| GAgP | generalized aggressive periodontitis |

| GCF | gingival crevicular fluid |

| GI | gingival index |

| HbA1c | glycated hemoglobin A1c |

| IL | interleukin |

| LAgP | localized aggressive periodontitis |

| M | male |

| NSPT | non-surgical periodontal treatment |

| OPG | osteoprotegerin |

| OPR | osteoporosis |

| PAL | periodontal attachment level |

| PASI | psoriasis area and severity index |

| PD | periodontitis |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| PPD | periodontal probing depth |

| RA | rheumatoid arthritis |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| sRANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand |

| SH | systemically healthy |

| T1DM | type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

References

- Kwon, T.; Lamster, I.B.; Levin, L. Current Concepts in the Management of Periodontitis. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Evidence-Based Update on Diagnosis and Management of Gingivitis and Periodontitis. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Silva, C.O.; Tatakis, D.N. Plaque-induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S44–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slots, J. Periodontitis: Facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontol 2000 2017, 75, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozçaka, O.; Nalbantsoy, A.; Buduneli, N. Interleukin-17 and interleukin-18 levels in saliva and plasma of patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2011, 46, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Ruddy, M.J.; Wong, G.C.; Sfintescu, C.; Baker, P.J.; Smith, J.B.; Evans, R.T.; Gaffen, S.L. An essential role for IL-17 in preventing pathogen-initiated bone destruction: Recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed bone requires IL-17 receptor-dependent signals. Blood 2007, 109, 3794–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tu, S.-Q.; Wei, J.-M.; Hou, Y.-L.; Kuang, Z.-L.; Kang, X.-N.; Ai, H. Role of Interleukin-17A in the Pathomechanisms of Periodontitis and Related Systemic Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 862415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J. Global, regional, and national burden of periodontal diseases from 1990 to 2021 and predictions to 2040: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Oral Health. 2025, 6, 1627746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, N.; Kesting, M. Cytokines in gingivitis and periodontitis: From pathogenesis to therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1435054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Jin, L.; Yang, Y. The dual role of IL-17 in periodontitis regulating immunity and bone homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1578635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernal, R.; Dutzan, N.; Chaparro, A.; Puente, J.; Valenzuela, M.A.; Gamonal, J. Levels of interleukin-17 in gingival crevicular fluid and in supernatants of cellular cultures of gingival tissue from patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkein, H.A.; Koertge, T.E.; Brooks, C.N.; Sabatini, R.; Purkall, D.E.; Tew, J.G. IL-17 in sera from patients with aggressive periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, P.; Buduneli, E.; Bıyıkoğlu, B.; Aksu, K.; Saraç, F.; Nile, C.; Lappin, D.; Buduneli, N. Gingival crevicular fluid, serum levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, osteoprotegerin, and interleukin-17 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis and with periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitani, A.; Niedbala, W.; Fujimura, T.; Mogi, M.; Miyamae, S.; Higuchi, N.; Abe, A.; Hishikawa, T.; Mizutani, M.; Ishihara, Y.; et al. Increased expression of interleukin (IL)-35 and IL-17, but not IL-27, in gingival tissues with chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, H.L.; Warad, S.; Ashok, N.; Baroudi, K.; Tarakji, B. Association of Interleukin-17 polymorphism (-197G/A) in chronic and localized aggressive periodontitis. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30, S1806-83242016000100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linhartova, P.B.; Kastovsky, J.; Lucanova, S.; Bartova, J.; Poskerova, H.; Vokurka, J.; Fassmann, A.; Kankova, K.; Holla, L.I. Interleukin-17A Gene Variability in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Chronic Periodontitis: Its Correlation with IL-17 Levels and the Occurrence of Periodontopathic Bacteria. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 2979846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, S.; Nazemisalman, B.; Hosseinpour, S.; Salavitabar, S.; Aziz, A. Interleukin-2, -16, and -17 gene polymorphisms in Iranian patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, e12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Venugopal, R.; Chandrayan, R.R.; Yuwanati, M.B.; Awasthi, H.; Jain, M. Association of chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus with salivary Del-1 and IL-17 levels. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2020, 10, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Carvajal, D.; Hernández, M.; Valenzuela, F.; Astorga, J.; Fernández, A. Levels of the interleukins 17A, 22, and 23 and the S100 protein family in the gingival crevicular fluid of psoriatic patients with or without periodontitis. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2021, 25, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.J.; Tu, C.C.; Hu, J.X.; Chu, P.H.; Ma, K.S.K.; Chiu, H.Y.; Kuo, M.Y.P.; Tsai, T.F.; Chen, Y.W. Severity of periodontitis and salivary interleukin-1β are associated with psoriasis involvement. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2022, 121, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvandi, M.; Jazi, M.S.; Fakhari, E. Association of interleukin-17A gene promoter polymorphism with the susceptibility to generalized chronic periodontitis in an Iranian population. Dent. Res. J. 2022, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Grover, V.; Arora, S.; Das, G.; Ahmad, I.; Ohri, A.; Sainudeen, S.; Saluja, P.; Saha, A. Comparative Evaluation of Gingival Crevicular Fluid Interleukin-17, 18 and 21 in Different Stages of Periodontal Health and Disease. Medicina 2022, 58, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhede, A.N.; Dhadse, P.V. Interleukin-17 levels in gingival crevicular fluid of aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis patients. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2022, 26, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek-Mochol, M.; Serwin, K.; Bonsmann, T.; Kozak, M.; Piotrowska, K.; Czerewaty, M.; Safranow, K.; Pawlik, A. Expression of Interleukin 17A and 17B in Gingival Tissue in Patients with Periodontitis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.R.; Xu, J.L.; He, L.; Wang, X.E.; Lu, H.Y.; Meng, H.X. Comparison of the inflammatory states of serum and gingival crevicular fluid in periodontitis patients with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaca, M.; Cebesoy, E.I.; Kocak-Oztug, N.A.; Bingül, I.; Cifcibasi, E. Interleukin-6, -17, and -35 levels in association with clinical status in stage III and stage IV periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezgi, S.T.; Gulay, T.; Aysegul, A.Y.; Melek, Y. Non-surgical periodontal treatment effects on IL-17 and IL-35 levels in smokers and non-smokers with periodontitis. Odontology 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; van Asten, S.D.; Burns, L.A.; Evans, H.G.; Walter, G.J.; Hashim, A.; Hughes, F.J.; Taams, L.S. Periodontitis-associated pathogens P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans activate human CD14(+) monocytes leading to enhanced Th17/IL-17 responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 2211–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Sánchez, M.A.; Guerrero-Velázquez, C.; Becerra-Ruiz, J.S.; Rodríguez-Montaño, R.; Avetisyan, A.; Heboyan, A. IL-23/IL-17 axis levels in gingival crevicular fluid of subjects with periodontal disease: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidharthan, S.; Gopalakrishnan, D.; Kheur, S.; Mohapatra, S. Assessment of the role of Th17 cell and related biomarkers in periodontitis: A systematic review. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 175, 106272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, S.; Holtfreter, B.; Reckelkamm, S.L.; Hagenfeld, D.; Kocher, T.; Alayash, Z.; Ehmke, B.; Baurecht, H.; Nolde, M. Effect of interleukin-17 on periodontitis development: An instrumental variable analysis. J. Periodontol. 2023, 94, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, D.T.; Corrêa, J.D.; Silva, T.A. The Oral Microbiota Is Modified by Systemic Diseases. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari-Nasab, E.; Moghadampour, M.; Tahmasebi, A. Meta-Analysis of Risk Association Between Interleukin-17A and F Gene Polymorphisms and Inflammatory Diseases. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2017, 37, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, F.; Tandon, A.; AlQallaf, H.; John, V.; Sinha, M.; Gibson, M.P. Inflammatory Association between Periodontal Disease and Systemic Health. Inflammation 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremese, E.; Tolusso, B.; Bruno, D.; Perniola, S.; Ferraccioli, G.; Alivernini, S. The forgotten key players in rheumatoid arthritis: IL-8 and IL-17—Unmet needs and therapeutic perspectives. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 956127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jonsson, A.H.; Nathan, A.; Millard, N.; Curtis, M.; Xiao, Q.; Gutierrez-Arcelus, M.; Apruzzese, W.; Watts, G.F.M.; Weisenfeld, D.; et al. Deconstruction of rheumatoid arthritis synovium defines inflammatory subtypes. Nature 2023, 623, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitales-Noyola, M.; Hernández-Castro, B.; Alvarado-Hernández, D.; Baranda, L.; Bernal-Silva, S.; Abud-Mendoza, C.; Niño-Moreno, P.; González-Amaro, R. Levels of Pathogenic Th17 and Th22 Cells in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 5398743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaan, S.F.; Taha, S.I.; Mahmoud, F.A.; Elsaadawy, Y.; Khalil, S.A.; Gamal, D.M. Role of Interleukin-17 in Predicting Activity of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Med. Insights. Arthritis Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 17, 11795441241276880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, J.M.; Le Goff, B. Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease. Jt. Bone Spine 2010, 77, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; He, C.; Xue, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Ren, Z.; Huang, Y.; Luo, H.; Chen, H.-N.; Zhang, W.-H.; et al. Single cell immunoprofile of synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis with TNF/JAK inhibitor treatment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pei, X.; Graves, D.T. The Interrelationship Between Diabetes, IL-17 and Bone Loss. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2020, 18, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgnakke, W.S. Current scientific evidence for why periodontitis should be included in diabetes management. Front. Clin. Diabetes Health 2024, 4, 1257087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brembilla, N.C.; Boehncke, W.H. Revisiting the interleukin 17 family of cytokines in psoriasis: Pathogenesis and potential targets for innovative therapies. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1186455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marruganti, C.; Gaeta, C.; Falciani, C.; Cinotti, E.; Rubegni, P.; Alovisi, M.; Scotti, N.; Baldi, A.; Bellan, C.; Defraia, C.; et al. Are periodontitis and psoriasis associated? A pre-clinical murine model. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Spirito, F.; Di Palo, M.P.; Rupe, A.; Piedepalumbo, F.; Sessa, A.; De Benedetto, G.; Barone, S.R.; Contaldo, M. Periodontitis in Psoriatic Patients: Epidemiological Insights and Putative Etiopathogenic Links. Epidemiologia 2024, 5, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzycka, M.; Andrzejewska, M.; Surdacka, A.; Surdacki, M.; Adamski, Z. Evaluation of the relationship between psoriasis, periodontitis, and markers of inflammation. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Montaño, R.; Alarcón-Sánchez, M.A.; Lomelí-Martínez, S.M.; Martínez-Bugarin, C.H.; Heboyan, A. Genetic Variants of the IL-23/IL-17 Axis and Its Association With Periodontal Disease: A Systematic Review. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2025, 13, e70147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, P.K.; Varghese, S.S.; Kumaran, T.; Devi, S.S. Meta-analysis of risk association between interleukin-17A rs2275913 and chronic periodontitis. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2020, 11, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, J.D.; Madeira, M.F.M.; Resende, R.G.; Correia-Silva, J.d.F.; Gomez, R.S.; Souza, D.d.G.d.; Teixeira, M.M.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; da Silva, T.A. Association between polymorphisms in interleukin-17A and -17F genes and chronic periodontal disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 846052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmohammadi, A.; Tavangar, A.; Ehteram, M.; Karimian, M. Association of A-197G polymorphism in interleukin-17 gene with chronic periodontitis: Evidence from six case-control studies with a computational biology approach. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, e12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.R.P.; Pessoa, L.D.S.; Vasconcelos, A.C.C.G.; de Aquino, L.W.; Alves, E.H.P.; Vasconcelos, D.F.P. Polymorphisms in interleukins 17A and 17F genes and periodontitis: Results from a meta-analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2017, 44, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek-Mochol, M.; Kozak, M.; Malinowski, D.; Safranow, K.; Pawlik, A. IL-17F Gene rs763780 and IL-17A rs2275913 Polymorphisms in Patients with Periodontitis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsherif, E.; Alhudiri, I.; ElJilani, M.; Ramadan, A.; Rutland, P.; Elzagheid, A.; Enattah, N. Screening of interleukin 17F gene polymorphisms and eight subgingival pathogens in chronic periodontitis in Libyan patients. Libyan J. Med. 2023, 18, 2225252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, A.M.; e Silva, M.R.M.A.; Silva, J.d.F.C.; da Costa, J.E.; Gollob, K.J.; Dutra, W.O.; Moreira, P.R. Evaluation of IL17A expression and of IL17A, IL17F and IL23R gene polymorphisms in Brazilian individuals with periodontitis. Hum. Immunol. 2013, 74, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Multiple Cytokine Gene Polymorphisms in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 713198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilharm, A.; Binz, C.; Sandrock, I.; Rampoldi, F.; Lienenklaus, S.; Blank, E.; Winkel, A.; Demera, A.; Hovav, A.-H.; Stiesch, M.; et al. Interleukin-17 is disease promoting in early stages and protective in late stages of experimental periodontitis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xie, P.; Jin, Z.; Qin, S.; Ma, G. Leveraging genetics to investigate causal effects of immune cell phenotypes in periodontitis: A mendelian randomization study. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1382270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, A.; Spirito, F.D.; Lembo, S. Oral Diseases During Systemic Psoriatic Drugs: A Review of the Literature and Case Series. Dermatol. Pr. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).