Abstract

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is a progressive multisystemic disease caused by a CTG repeat expansion in the DMPK gene. The toxic mutant mRNA sequesters MBNL proteins, disrupting global RNA metabolism. Although alternative splicing in DM1 skeletal muscle pathology has been extensively studied, early-stage transcriptomic changes remained uncharacterized. To gain deeper and contextual insight into DM1 transcriptome, we performed the first Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) on skeletal muscle RNA sequencing data from the widely used DM1 mouse model HSALR (~250 CTG repeats). We identified 532 core genes using data from 16-week-old mice, an age before the onset of muscle weakness. Additional differential expression analysis across multiple HSALR datasets revealed 42 common up-regulated coding and non-coding genes. Within identified core genes, the pathway gene-pair signature analysis enabled contextual selection of functionally related genes involved in maintaining proteostasis, including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein processing, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), macroautophagy and mitophagy, and muscle contraction. The enrichment of ER protein processing with prevailing core genes related to ER-associated degradation suggests adaptive chaperone and UPS activation, while core genes such as Ambra1, Mfn2, and Usp30 indicate adaptations in mitochondrial quality control. Coordinated early alterations in processes maintaining protein homeostasis, critical for muscle mass and function, possibly reflect a response to cellular stress due to repeat expansion and appears before muscle weakness development. Although the study relies exclusively on transcriptomic analyses, it offers a comprehensive, hypothesis-generating perspective that pinpoints candidate pathways, preceding muscle weakness, for future mechanistic validation.

1. Introduction

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1, OMIM: #160900) is the most common adult-onset muscular dystrophy. It is characterized by multisystemic symptoms whose progression cannot be slowed or stopped with available treatments. The underlying autosomal dominant mutation is an unstable expansion of 50 to more than 1000 CTG repeats in the 3′ untranslated region of the DM1 protein kinase (DMPK) gene [1]. Disease severity is broadly correlated to the variable number of repeats [2]. Germline repeat instability underlies genetic anticipation, causing symptoms to start earlier and worsen in later generations, while somatic repeat instability drives disease progression [3]. The main mechanism of DM1 molecular pathogenesis is RNA gain-of-function, where DMPK transcript with expanded CUG repeats acquires new toxic functions [4]. In DM1, tissue and developmental stage-specific splicing is disrupted by the toxic RNA inactivation of MBNL proteins by sequestration in ribonuclear foci and downstream overactivation of CELF1 protein by hyperphosphorylation [5]. Along with the aberrant splicing as a molecular hallmark of DM1, the toxic RNA also causes disruptions in polyadenylation, transcription, and translation of numerous genes [6].

The development of various genetically engineered mouse models has played an essential role in molecular, cellular, pathophysiological, and preclinical research of DM1. HSALR model is the most commonly used one and was generated by random insertion of a genomic fragment carrying the human skeletal actin gene (ACTA1) with ~250 CTG repeats in its 3′UTR [7]. This transgene is expressed only in skeletal muscles and its resulting transcript is retained in the nucleus [7]. These mice develop myotonia at 4 weeks of age, while at that time there are no signs of abnormal muscle histology [7]. Later, DM1-specific muscle histopathology is developed involving abundant central nuclei, ring fibers, and variable fiber size with no necrosis [7], whereas muscle weakness becomes obvious in adult mice at 24 weeks of age [8], and mortality increases by 41% by 44 weeks [9].

Transcriptomic studies on HSALR and Mbnl knockout mice, also serving as DM1 models, reveal commonalities in alternative splicing and differential gene expression [10,11]. Further, analysis of both transcriptome and proteome of HSALR mice has revealed a certain quantitative agreement of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and alternative splicing [12]. While alternative splicing and DEG studies revealed important transcriptomic alterations in DM1, they offer limited insight into coordinated gene expression changes. Gene co-expression analysis enables the discovery of such groups of genes, highlighting system-level dysregulation. Yet, no gene co-expression networks were made for DM1 mouse models. Here, we performed an exploratory, comprehensive transcriptome analysis including weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), to identify clusters of highly co-expressed genes associated with the HSALR mouse genotype and expected to be related with impaired molecular and cellular processes appearing downstream from the toxic RNA.

2. Results

The raw reads derived from 59 skeletal muscle samples of HSALR mice from seven bulk paired-end RNA-seq experiments were acquired from NCBI (BioProject database Accession Numbers and references to publications are given in Table S1). After raw reads preprocessing, the mapping rates ranged from 78 to 98%, while the percentage of reads successfully assigned to genes (gene quantification) ranged from 65 to 86% (Table S1).

WGCNA was performed to identify gene co-expression networks, representing modules of genes with potentially common biological functions, associated with DM1 across a set of samples [13]. The unsigned network type (which uses absolute values of correlations to cluster co-expressed genes) was chosen to provide robust representation of gene co-expression patterns. The Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) [14] was selected for WGCNA because it contains the largest number of samples from adult HSALR (9 samples, 16 weeks old) and wild-type mice (9 samples, 15 weeks, and 6 days old) from both proximal and distal skeletal muscles (Table S1).

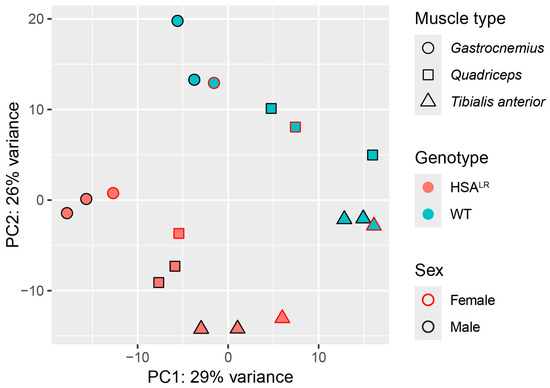

First, a principal component analysis (PCA) of the normalized (variance-stabilized) counts was performed to explore the sample clustering according to gene expression. It was found that genotype (HSALR or wild type) had the strongest influence on the separation of samples, followed by muscle type (quadriceps, tibialis anterior, or gastrocnemius), with no effect of sex (Figure 1). This is in line with functional measurements, histology, and molecular/biochemical profiles between male and female HSALR mice that showed no significant differences [15]. Similarly, samples displayed clustering based on distances in a hierarchical clustering step of WGCNA (Figure S1A).

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) illustrates the effect of genotype and muscle type on detected gene expression patterns in Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789). PCA plot performed on variance-stabilized counts demonstrates that the main drivers of separation between samples are genotype followed by muscle type. The grouping of samples was not influenced by sex.

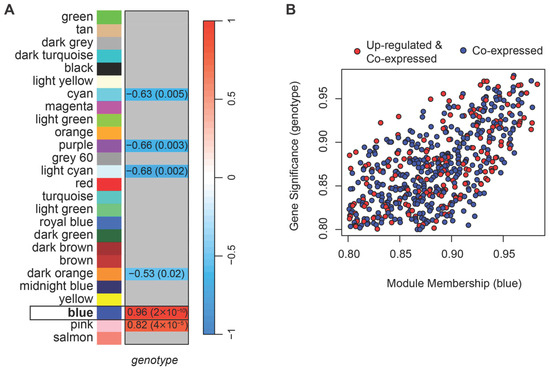

The WGCNA performed on normalized counts identified 26 modules of co-expressed genes (Figure S1B). A soft-thresholding power of four was selected as the lowest value at which the network approximately fits a scale-free topology (R2 > 0.8; Figure S2). Among the detected modules, two eigengenes, i.e., first principal components of the module (blue and pink) were positively correlated, and four (cyan, purple, light cyan, and dark orange) negatively correlated with the HSALR genotype (Figure 2A). For each gene, we calculated gene significance (GS), defined as the Pearson correlation between gene expression and the HSALR genotype (coded as 1 for HSALR and 0 for wild type), and module membership (MM), defined as the correlation between gene expression and the module eigengene. A threshold of 0.8 for the absolute values of both GS and MM was used together with p-values ≤ 0.05, to identify genes strongly associated with both the trait and their module. Only the blue module contained genes that met these criteria.

Figure 2.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Analysis (WGCNA) shows 26 modules of co-expressed genes, with the blue module (framed) showing the strongest association with HSALR genotype. (A) Heatmap showing Pearson correlation between module eigengenes, i.e., the first principal components of modules, and genotype (HSALR vs. wild type), with corresponding p-values in parentheses. Two module eigengenes (blue and pink) show significant positive correlations with the HSALR genotype, and four modules (cyan, purple, light cyan, dark orange) show significant negative correlations. Gray boxes indicate correlations with p-value > 0.05. (B) Scatterplot of gene significance (GS) versus module membership (MM) for genes in the blue module. Shown genes are with GS and MM > 0.8 and their p-values ≤ 0.05. Red points mark genes that are also up-regulated in HSALR according to DESeq2 analysis of Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789), indicating overlap between co-expression and differential expression. These high-MM, high-GS genes are hereafter referred to as core genes of the blue module.

To further isolate genes driving the blue module’s positive correlation in HSALR, we filtered for those with positive GS and positive MM above 0.8 (with corresponding p-values ≤ 0.05). Although the network was unsigned, focusing on genes with both positive GS and MM allowed us to identify a coherent subset of genes that are not only highly connected within the module but can also be more highly expressed in the HSALR group. These genes are likely to be presumed drivers of the module’s association with HSALR genotype (Figure 2B, Table S2) and were selected for downstream analyses (hereafter referred to as core genes). While Hicks et al. reported muscle type-dependent expression of the transgene [14], we did not observe significant associations of individual gene expression levels with muscle type in our data (|GS & MM| > 0.8, p ≤ 0.05).

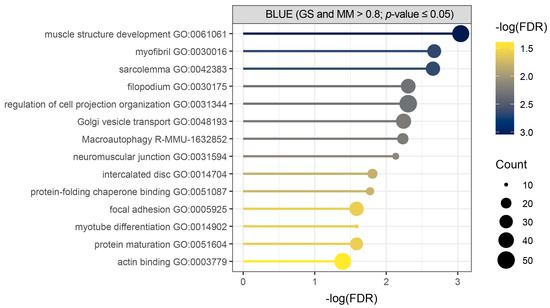

Over-representation analysis (ORA) was used as an initial approach to identify enriched terms and pathways among the core genes of the blue module, applying a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.05 (Figure 3, Table S3). It showed significant enrichment of biological process terms related to muscle structure development, muscle cell components, macroautophagy, and protein folding and maturation in our query of total of 532 detected core genes (Figure 3, Table S3).

Figure 3.

Over-representation analysis (ORA) performed for core genes of the blue module shows initial biological overview guiding towards muscle development, muscle cell components, macroautophagy, and protein folding and maturation. Metascape enrichment results of core genes (GS and MM > 0.8; p-value ≤ 0.05) detected in Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) shows terms with (−log(FDR) > 1.3), where count represents the number of query genes in each enriched term.

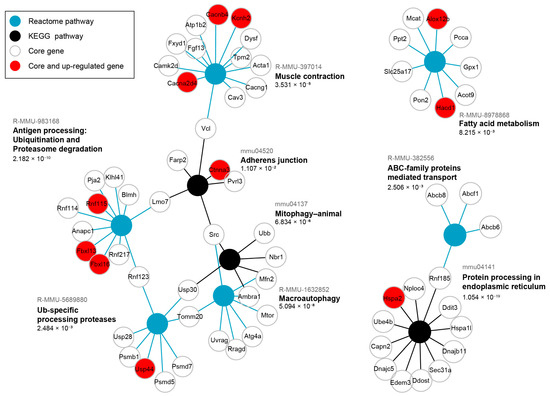

As many genes show a pleiotropic effect and take part in many functions, we additionally performed a significant over-representation analysis (SIGORA) of pathway gene-pair signatures [16] for the same core genes of the blue module. This analysis considers multiple genes as indicators of a certain pathway enabling a more contextual approach than ORA which treats pathways as simple sets of equally important individual genes and can lead towards too general hits when pathways share key components with more relevant processes. Significant results (FDR < 0.05) are shown in form of a graph (Figure 4) where there are different types of nodes representing each enriched pathway and enriched core genes. This analysis identified several signature pathways, reinforcing the major functional themes of blue module core genes.

Figure 4.

Significant over-representation (SIGORA) of blue module core genes, strongly associated with HSALR genotype, shows their convergence on proteostasis and muscle contraction. Graph representation of SIGORA Reactome and KEGG pathway gene-pair signature enrichment for core genes detected in Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) that are strongly correlated with the blue module eigengene and HSALR genotype (GS and MM > 0.8, p-value ≤ 0.05), filtered by Bonferroni FDR < 0.05. The up-regulated were detected by DESeq2 in the same dataset and are present in the module (depicted by red). FDR values for each enriched pathway are written below, while pathway IDs are written in gray above the pathway names.

Protein processing in ER is the enriched term with the lowest FDR (1.054 × 10−19, Figure 4). It encompasses DnaJ heat shock family (Hsp40) members (Dnajc5, Dnajb11), heat shock 70 family members (Hspa1l, Hspa2), along with ubiquitination-related genes (Rnf185, Nploc4, Ube4b). The coordinated expression of these genes, along with a protein that accelerates degradation of misfolded glycoproteins in the ER (Edem3) suggests the activity of ER-associated degradation (ERAD). A multifunctional transcription regulator Ddit3, involved in ER stress response, is an additional core gene in the term Protein processing in ER. Next, the term Antigen processing Ubiquitination and Proteasome degradation (FDR = 2.182 × 10−10), contains E3 ubiquitin-ligase genes (Fbxl13, Fbxl16, Pja2, Klhl41, Rnf217, Rnf115, Rnf114, Rnf123) (Figure 4), suggesting an increased ubiquitination. Conversely, the term Ub-specific processing proteases (FDR = 2.484 × 10−3) mostly includes ubiquitin-peptidase genes (Usp28, Usp44, Usp30), as well as one shared E3 ubiquitin-ligase gene (Rnf123), along with genes of proteasome regulatory (Psmd5, Psmd7) and core (Psmb1) components (Figure 4). Collectively, these two enriched terms suggest tight regulation of protein degradation.

The Macroautophagy term (FDR = 5.094 × 10−8) encompasses genes such as Ambra1, an autophagy regulator, and autophagy-related genes (Atg4a, Uvrag), which beside kinase genes (Mtor, Src) indicate multiple degradation pathways activity, including mitophagy identified as an additional enriched term (Figure 4). The core genes in Mitophagy-animal term (FDR = 6.834 × 10−6) include Ambra1, Src, Ubb (ubiquitin), Nbr1 (a selective autophagy adaptor), Usp30 (deubiquitylase constitutively associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane proteins), and Mfn2 (involved in mitochondrial dynamics and ER mitochondria contact sites). The ABC-family proteins mediated transport term (FDR 2.506 × 10−3), including Abcb8 and Abcb6 (both involved in mitochondrial transport across its membranes), the Fatty acid metabolism term (FDR = 8.215 × 10−3) with Gpx1 (an antioxidant enzyme), and Tomm20 (core component of mitochondrial membrane’s protein machinery), suggest alterations in mitochondrial function and may be related to an increased need of mitochondrial quality control.

Enrichment of the Muscle contraction term (FDR = 3.531 × 10−5), uniting genes encoding K+ and Ca2+ channels (Kcnh2, Cacnb4, Cacna2d4, Cacng1) with structural proteins of sarcomere (Tpm2, Acta1) and sarcolemma (Dysf, Cav3, Fxyd1, Vcl), may reflect early molecular changes that precede muscle weakness (Figure 4). Here, Acta1 should be interpreted with caution or even omitted since it did not show up as DEG in any of the datasets (Table S4), and its human ortholog is present in the HSALR transgene. Adherens junction (FDR = 1.107 × 10−2), as the least statistically significant term, includes genes contributing to cadherin-mediated adhesion (Pvrl3), actin cytoskeleton anchoring and remodeling (Vcl, Ctnna3, Farp2), as well as intracellular signaling (Src).

Proteins encoded by core genes from SIGORA enriched pathways were analyzed in the STRING database, filtering for experimentally validated interactions (confidence ≥ 0.4). This analysis complements SIGORA, revealing experimentally validated interactions among the protein products of SIGORA core genes, divided into four clusters as follows: two pairs (Cav3-Src and Ctnna3-Vcl), a cluster of Ca2+-channel proteins (Cacnb4-Cacng1-Cacna2d4), and the largest cluster centered on Ubb with interactions related to the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Supplementary Figure S3).

To determine the influence of HSALR toxic RNA on direction of individual gene’s expression, DEGs were determined by DESeq2 [17] between HSALR and wild-type groups using the predefined criterion of an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and absolute log base 2 of fold change > 1. The detected DEGs of Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) [14] were overlaid with blue module genes and annotated on the corresponding plots (Figure 2B and Figure 4). Examples of DEGs that were also core genes are observed as coordinately up-regulated with roles in K+ and Ca2+ transport (Kcnh2, Cacnb4, Cacna2d4), ubiquitination and protein folding (Usp44, Rnf115, Fbxl13, Fbxl16, Hspa2), fatty acid metabolism (Alox12b, Hacd1), cell adhesion (Ctnna3) (Figure 4, Table S4).

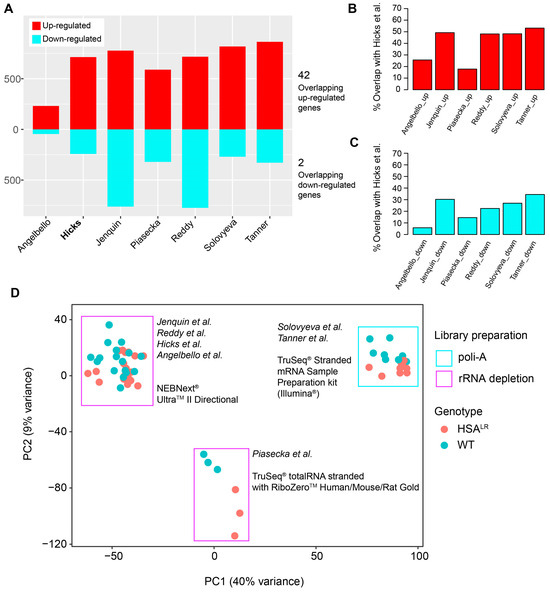

Next, DEGs were overlapped between seven analyzed datasets (Figure 5A, Tables S1 and S4). Overlapping DEGs showed 42 common up-regulated genes from HSALR samples compared to their respective wild-type controls, including both protein-coding (Atp8a2, Camk1d, Ccdc192, Chrna9, Cilp, Cpne2, Cstad, Eda2r, Hsf2bp, Mustn1, Myo1a, Nrg2, Plekho1, Plp2, Prepl, Rrad, Runx1, S100a4, Sbk2, Tceal7, Trp73, Ttc9, Uchl1) and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) genes (Atcayos, Rian, Sp3os), where the listed ones were also core genes of the blue module (Table S4). There were only two common down-regulated genes in HSALR datasets (Hmga2-ps1 and Vamp1) (Table S4). These overlapping DEGs are associated with key skeletal muscle cellular components like the sarcolemma, sarcomere or sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Kcnn3, Sln, Myo1a, Mustn1, Uchl1), mitochondria (Cstad, Vamp1, Uchl1), and the ER/SR specifically (Sln, Uchl1). In case of Atcayos, Sp3os, and Hmga2-ps1, they are expected to cis-regulate the expression of Atcay/Nmrk2, Sp3, and Hmga2, respectively. The overlap of the DEGs from all datasets (Figure 5A), along with the DEGs from Hicks et al. (PRJNA1103789) [14] with each dataset (Figure 5B,C) shows that gene up-regulation is a more common event.

Figure 5.

Overview of shared differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among datasets, with the two-dimensional PCA that illustrates the effects of library preparation on the gene expression between datasets. (A) An overview of the number of up- and down-regulated genes in the analyzed datasets, with the number of shared up-regulated or down-regulated genes acquired by DESeq2. (B) Percentage of shared up-regulated genes and down-regulated genes between the Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) and each other analyzed dataset. (C) Percentage of shared down-regulated genes between the Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) and each other analyzed dataset. (D) Two-dimensional PCA performed on merged and variance-stabilized count/expression data from all datasets with annotations for genotype and library preparation.

Finally, to evaluate the possible batch effects on differences in gene expression between the datasets, PCA was performed on the normalized and variance-stabilized counts of all datasets (Figure 5D). It showed the effect of library preparation and separated datasets with 40% variance represented by the first principal component. This effect was considered when comparing DEGs, and led our decision to focus on a single dataset for WGCNA, in addition to sufficient total number of samples for this analysis (minimum is 15 samples).

3. Discussion

Despite significant progress in understanding DM1 molecular pathogenesis, the knowledge about downstream effects of toxic RNA on both cellular and systemic levels remains fragmented. They are often studied in isolated experiments with a focus on single mechanism/process, neglecting a more global picture important for the better understanding of complex systems [18]. This exploratory study is based solely on transcriptomic data and presents the first robust gene co-expression network analysis in the most commonly used DM1 mouse model—HSALR that expresses toxic RNA and mirrors skeletal muscle pathology. We identified prominent transcriptomic changes in 16-week-old mice prior to development of muscle weakness, which typically emerges around 24 weeks with reduced number of satellite cells and myofibers [8]. Using a single Hicks et al. RNA-seq dataset (PRJNA1103789) [14], our analysis captured transcriptomic alternations in multiple processes involved in protein degradation and muscle contraction (Figure 4), indicating that tight regulation of protein homeostasis on which muscle mass and function depend, could be impaired before the onset of muscle weakness.

Coordinately expressed genes in the enriched term Protein processing in ER are mainly involved in ERAD, a quality control mechanism in the protein secretory pathway that helps clear terminally misfolded proteins from ER lumen by directing them toward ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation in the cytoplasm [19,20]. In our results, Dnajb11 and Edem3 core genes are involved in selecting misfolded proteins in ER lumen for translocation to the cytoplasm. DNAJB11, a heat shock family 40 chaperone, binds soluble misfolded ER proteins for BiP (HSPA5)-mediated degradation [21], while EDEM3 participates in glycoprotein quality control, where it recognizes proteins stuck in calnexin/calreticulin folding cycle targeting them to ERAD [20]. The core genes also involve Rnf185 coding ERAD-related E3 ubiquitin ligase localized at the ER membrane, and Nploc4 whose protein product is part of p97/VCP-NPLOC4-UFD1 complex responsible for extracting ubiquitinated misfolded proteins from ER membrane and delivering them to proteasome [22]. Heat shock 70 family chaperones (represented among core genes by Hspa1l and Hspa2) recognize defective proteins in the cytoplasm, forming one of the quality control checkpoints for ERAD [20]. Another mechanism of protein quality control in ER is the unfolded protein response, activated when misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER and serving as ERAD back-up [19]. Human DM1 myotubes showed increased mRNA and protein levels of CHOP [23], a human homolog of Ddit3, which is an unfolded protein response gene and an ER and cellular stress induction marker [19]. Although it is one of the core genes, Ddit3 is not co-expressed with any other hallmark genes of unfolded protein response (e.g., Hspa5, Xbp1, Eif2ak3, Ire1 or Ern1, Atf4 or Atf6) [24] and neither is up-regulated in any of analyzed datasets (Table S4), making the unfolded protein response and ER stress less probable in HSALR mice at age of 16 weeks. These results may imply that prior the muscle weakness onset, ERAD successfully clears misfolded proteins, alleviating ER stress [19] that has been observed in DM1 patient muscle biopsies and thought to be involved in muscle wasting [25].

The second most significantly enriched term highlights alternation in ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in HSALR mice. Most myofibrillar proteins are degraded through UPS, which if dysregulated can promote muscle wasting, myofiber degeneration, and muscle weakness [26]. In addition, UPS interacts with ER membrane and degrades secreted proteins that are targeted by ERAD [20]. Identified core genes include ubiquitin-ligases, considered as one of the causes of muscle mass decrease when upregulated [27], proteasomal subunits, and ubiquitin-hydrolase genes. Although HSALR mice do not yet exhibit muscle weakness at 16 weeks of age, these early transcriptomic changes are in line with increased proteasome activity described in DM300 mice (carriers of ~550 repeats) between 3 and 10 months of age when progressive muscle weakness appeared [28], and in DMSXL mice (carriers of >1000 repeats) at 4 months of age when muscle weakness had already developed [29].

The next protein degradation pathway highlighted in our results is autophagy. It is the second major proteolytic system, extending to degradation of dysfunctional cell components (macroautophagy), such as mitochondria (mitophagy), with the main activation factor being nutrient starvation [26]. Multiple core genes mark the initiation phase of autophagy, where they are involved in the regulation of Beclin1-Vps34 complex (Ambra1, Uvrag), or acting as cargo degradation receptors of ubiquitinated substrates for autophagy (Nbr1) [30]. In line with our findings, HSALR mice have increased the expression of autophagic and mitophagic proteins and increased tagging of damaged organelles (including mitochondria), likely due to an impaired capacity for protein degradation under basal conditions [31,32]. Furthermore, HSALR has reduced levels of AMPK activation (an event that activates catabolic pathways such as autophagy) [32], and mild changes in autophagic markers, and also shows AMPK- and mTORC1-independent mechanisms contributing to autophagy [32]. However, in the context of DM1 there are conflicting results about the status of AMPK depending on the model used [18]. Interestingly, there is a notion that autophagy could be a source of energy for the activation of quiescent satellite cells emphasizing its importance for the DM1-affected adult skeletal muscle progenitor cells [33]. Increased autophagic flux along with abnormal activation of UPS, is related not only to muscle weakness, but also atrophy in DM1 [32], a symptom that is not recapitulated by HSALR mice [7,8]. A series of events described in DM1 cells, but not explored in HSALR, causes the emergence of UPS activity and autophagy, and starts from the STAU1 stabilization, followed by PTEN activation and down-regulation of AKT signaling [18,34]. In addition, in UPS-deficient mice, autophagy is enhanced, and satellite cell function impaired [26], while in myocytes autophagy accounts for 40% of degradation of long-lived proteins with an ability to become a backup for UPS [30]. Balanced autophagy is essential for skeletal muscles: basal activity clears damaged mitochondria and sustains satellite-cell fitness, whereas both excessive autophagy (driving atrophy and apoptosis in some myopathies) and deficient autophagy (in aging or sarcopenia) can culminate in muscle cell death and weakness [35]. Taken together, in skeletal muscles both proteolytic systems are connected [36], and their crosstalk should be explored in DM1.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is proposed to be a contributor to DM1 phenotype in patient skeletal muscles due to severe downregulation of mitochondrial transcription, protein abundance, and respiration [37]. By interpreting autophagy-related results at the level of individual core genes and their features, we identify a co-expression of genes linked to mitophagy suggesting their coordinated regulation. Among these, Mfn2, Ambra1, and Usp30 emerged as key components of mitochondrial quality control mechanisms (Figure 4). Mfn2 is involved in regulating mitochondrial quality control and fusion [38], while Ambra1 participates in skeletal muscle mitophagy and mitochondrial function, while also regulating the activity of both cell proliferation and autophagy machineries [39]. Usp30, a deubiquitinase, regulates mitochondrial dynamics by modulating turnover of outer membrane proteins such as Mfn1 or Mfn2, and its inhibition promotes mitochondrial fusion [40]. This co-expression suggests a known regulatory triad in which USP30-mediated deubiquitination stabilizes Mfn2 to suppress mitophagy, while AMBRA1 provides a compensatory mechanism to restore mitochondrial clearance [41], indicating a dynamic balance between fusion, degradation, and autophagy which could be relevant for mitochondrial integrity in the early DM1 pathology.

Furthermore, mitophagy depends on UPS, as ubiquitination of proteins such as Mfn2 or TOM20 promotes fission and the removal of mitochondria by autophagosomes [36]. The co-expression of ER and mitochondrial genes may reflect adaptations at the level of mitochondria-associated membranes (specialized regions of ER membrane), which facilitate functional coupling of the two organelles with proteins such as Mfn2 or TOM20 that mediate calcium exchange and coordinate mitochondrial dynamics with ER homeostasis [42]. Interestingly, MFN2 has been found to play fusion-independent role, interacting with proteasome and cytosolic chaperones in prevention of newly synthesized protein aggregation [43]. Similarly, Hspa1l and Rnf185 orthologs participate in mitochondrial protein quality control and selective mitophagy, respectively [44,45]. While these findings suggest a potential role for mitochondrial–autophagy crosstalk in maintaining proteostasis, they remain correlative and require experimental validation to establish a causal relationship in early DM1 muscle pathology. Notably, in the context of muscle wasting the disruption of mitochondrial network seems to be crucial for the muscle atrophy program, and it has been shown that expression of fission machinery in mice is sufficient to cause muscle wasting [27]. However, HSALR mice when compared to patients do not show a decrease in mitochondrial protein abundance between the age of 3 and 6 months [31].

Beyond proteostasis, transcriptomic changes reflect possible alterations in muscle contractile function, but these results can also be traced back to UPS and autophagy. A core gene for calcium-/calmodulin-dependent kinase gene (Camk2d) has two isoforms and does not show major splicing changes in HSALR mice or DM1 cells [46]. However, in cardiomyocytes the increased activity of its cytoplasmic form reduces contractility and alters Ca2+ handling [47]. Interestingly, Kcnh2, which is also an up-regulated potassium voltage-gated channel gene in Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789) [14], is shown to be up-regulated in atrophic mice, where its activity modulates ubiquitin proteasome proteolysis in gastrocnemius muscles [48]. Among core genes, several voltage-gated calcium channel genes (Cacnb4, Cacna2d4, and Cacng1) along with Ddit3 may be related to stress due to the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER lumen [23]. Ca2+ is released from the SR after depolarization of the sarcolemma, but is also known to be involved in proliferation, apoptosis, and protein folding, as chaperones are calcium-binding [23]. Human DM1 myotubes showed uncoupling of the ER/SR Ca2+ store and voltage-induced Ca2+ machinery [23]. Under dysregulation of calcium cycling dynamics, Ca2+ transfer from the ER to the mitochondria can lead to an overload of the mitochondrial matrix, triggering a permeability transition and the collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, an increase in ROS, and the release of pro-apoptotic factors [49]. In this regard, we detected two core genes, Alox12b and Gpx1, both related to oxidative stress response [50,51]. If mitochondria are defective, increased ROS can promote myofiber degeneration by activating AMPK and promoting autophagy as well as UPS degradation [36]. Skeletal muscles do not have any cell–cell junctions, therefore genes belonging to Adherens junction term (Figure 4) should be regarded as early signs of possible cell–matrix cytoskeletal remodeling preceding weakness and involving genes such as Vcl [52].

To complement network and pathway analyses, we explored differential expression results across multiple publicly available RNA-seq datasets from untreated HSALR muscle tissues. This is the first study to compare differential gene expression analysis output across multiple HSALR datasets, which ensured higher confidence of obtained DEGs. Through the analysis of these datasets, we uncovered frequently occurring DEGs that were largely up-regulated. We identified a common up-regulation of two lncRNAs Rian (AB063319) and Atcayos. Rian expression is dynamic across development and aging [53], while Atcayos is up-regulated during the rapid growth stage of satellite cells [54]. In this context, it is important to consider the progressive reduction in muscle strength, along with impaired muscle regenerative capacity in HSALR [8]. Here, 12-week-old mice show elevated Pax7 expression, suggesting active satellite cells and preserved regeneration, while 24-week-old mice exhibit fewer nuclei below basal lamina, lower amount of Pax7+ cells and myofibers, indicating impaired regeneration [8]. Furthermore, Atcayos is an antisense transcript from the locus of Atcay gene, which is important for acetylcholine signaling [55,56]. Atcay is co-localized with mitochondria and plays a role in spatial positioning of mitochondria in neurites [57]. Since lncRNAs are not included in gene ontologies or metabolic pathways databases, but could be regulating genes involved in those terms/pathways, it would be useful to consider them for further research as factors shaping the DM1 molecular pathology. In closing, there are several commonly up-regulated genes which relate to muscle function and therefore DM1 pathology. For example, sarcolipin (Sln) is up-regulated in atrophic muscles and may contribute to promoting oxidative metabolism under conditions of metabolic stress [58]. The up-regulation of pre-mRNA of Sln, a ubiquitin-hydrolase gene Uchl1, as well as ectodysplasin A2 receptor (Eda2r) has already been shown by competitive RT-PCR analysis [59]. Additionally, a calcium-dependent protein copine II (Cpne2) gene and Uchl1 have confirmed the up-regulation of protein expression by immunoblot in HSALR mice [59]. Lastly, the shared down-regulated gene Vamp1 coding for synaptic vesicle-associated integral membrane protein has a role in Ca2+-triggered neurotransmitter release at the mouse neuromuscular junction, where it is also crucial for its efficacy [60]. However, it should be noted that there is no toxic RNA in neurons of HSALR mice, which limits the representation of neuromuscular junction changes in DM1. These results coming from multiple datasets emphasize complex structural and functional players of early DM1 transcriptome, considering the age range (5-16 weeks) of analyzed HSALR mice RNA-seq data (Table S1).

The main limitations of this study are that it is exploratory and hypothesis-generating, based solely on transcriptomic data, and it relies on gene-level without considering splicing isoform level. Nevertheless, the results provide a coherent and detailed transcriptomic overview, with discussed key pathways prioritized by enrichment significance. The absence of wet-lab validation represents another limitation.

The results of this study provide basis for many different wet-lab follow-up experimental validations. We are suggesting a subset of genes, considering their expression patterns and correlation with HSALR genotype, for functional follow-up experiments. To validate our findings, future studies should validate co-expressed genes such as Dnajb11, Edem3, Rnf185, Hspa1l/Hspa2, Ambra1, Mfn2, Usp30, Drp1, Camk2d, Kcnh2 at the protein level using Western blot (WB) in 16-week-old HSALR mice without severe DM1 symptoms. Additionally, using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with reverse transcription it would be important to measure the expression of identified lncRNAs Rian and Atcayos since they are present in all analyzed datasets (aged 5 to 16 weeks) as up-regulated (Table S4). The measurement of these lncRNAs should be quantified for different ages of HSALR mice to correlate their expression with disease progression. It would be interesting to assess UPS function in 16-week-old HSALR mouse muscles by measuring proteasome activity using fluorogenic substrates, and by evaluating ubiquitin accumulation or K48-linked ubiquitin chains through WB or immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, monitoring the degradation kinetics of misfolded ER protein reporters can in primary myoblasts or myotubes derived from HSALR mice enable exploring ERAD efficiency in this system. Additionally, one should consider assessing the accumulation of LC3-II both with and without a lysosomal inhibitor to explore autophagy in muscles of 16-week-old HSALR mice. Furthermore, mitophagy can be assessed by measuring PINK1 accumulation and Parkin Ser65 phosphorylation by WB, combined with qPCR analysis of mitochondrial DNA to quantify mitochondrial mass. Together, these experiments would provide functional validation of our network-based findings, highlighting molecular events present in early DM1.

In conclusion, our study provides the first system-level view of the HSALR transcriptome using WGCNA, suggesting coordinated early alterations in proteostasis pathways, including ERAD, UPS, autophagy, mitophagy, and genes linked to muscle contraction. These transcriptomic signatures emerge in the absence of apparent muscle weakness, underscoring their potential role as early markers of DM1 pathology. By integrating co-expression and cross-dataset DEG analysis, we highlight a set of robust candidate pathways that warrant validation at the proteomic and functional levels. Future work should explore how these early molecular changes and crosstalk in protein degradation processes connect to muscle weakness progression and whether they can be targeted for therapeutic intervention. Importantly, testing these candidate pathways jointly in patient-derived samples will be essential to determine their relevance beyond the HSALR model.

4. Materials and Methods

Ten publicly available RNA-seq datasets from skeletal muscles of HSALR mouse models expressing repeat expansion were obtained from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database. Last search was performed on 13th November 2024. Among these datasets, the age ranged from the 5 to 16 weeks, while there were both proximal (quadriceps) and distal (tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius) skeletal muscle tissues (Table S1).

To systematically compare results between datasets, we relied on identical tools throughout the workflow with slight parameter modification according to dataset properties. First, reads were quality-checked, trimmed, mapped, and quantified by using FastQC (v.0.11.9) [61], Cutadapt (v.3.8) [62], hisat2 (v.2.1.0) [63], and featureCounts (v.2.0.0) [64], respectively. Next, differential gene expression analysis was performed by DESeq2 (v.1.46.0) [17] in the R environment version 4.4.2 [65], using genotype (HSALR or wild type) as the only factor variable in the design formula. The thresholds for the adjusted p-value and the absolute log base-2-fold-change for this analysis were as follows: padj < 0.05, |log2FC| > 1. All visualizations were performed in R.

The two-dimensional PCA, performed using the pca wrapper function from the M3C package (v.1.28.0) [66], on the input in the form of merged counts from all datasets converted into a matrix of variance-stabilized values using DESeq2’s varianceStabilizingTransformation function, was used to obtain a general overview of various biological and/or technical effects on gene expression in all data used. For Hicks et al. dataset (PRJNA1103789), PCA was performed individually for variance-stabilized counts using DESeq2’s built-in plotPCA function.

To detect co-expression patterns in Hicks et al. HSALR dataset [14], the weighted gene co-expression network was constructed using the WGCNA package (v.1.73) [13]. The network was built with a soft-thresholding power of 4 by using the blockwiseModules function (scale-free topology fit index R2 = 0.82). Key parameters included an increased block size (30,000) to ensure a single-block analysis, unsigned network type, unsigned topological overlap matrix (TOM), merge cut height of 0.25 (to favor more distinct modules), and enabled parameters for Partitioning Around Medoids (PAM) clustering with pamRespectsDendro = TRUE to preserve hierarchical clustering of gene dendrograms. These settings were selected to balance network robustness and biological interpretability.

Module-trait relationships were assessed using Pearson correlations between module eigengenes (i.e., their first principal components) and the genotype (1 for HSALR and 0 for wild-type). For each gene, gene significance (GS) was defined as the Pearson correlation between gene expression and the binarized genotype, and module membership (MM) was defined as the correlation between gene expression and the corresponding module eigengene. Although the network was unsigned and modules may contain both positively and negatively correlated genes, we specifically focused on genes with positive GS and positive MM (with respective p-values ≤ 0.05), reflecting those whose expression level positively correlates with HSALR, as well as the module itself, i.e., the module eigengene. This subset of genes is co-expressed and associated with HSALR genotype.

Over-representation analysis (ORA) for core genes of the WGCNA blue module that were positively associated with HSALR genotype (GS and MM > 0.8; p-value ≤ 0.05) was performed in Metascape (v.3.5.20250101) [67], with enrichment p-value < 0.05, gene overlap > 3, enrichment > 1.5, and the following database selection: Gene Ontology (GO): Biological Processes, Molecular Functions, and Cellular Components, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathways (KEGG), and Reactome. The non-redundant ‘summary’ terms that have FDR (i.e., q-value) ≤ 0.05 from ORA results were plotted using the ggplot2 package [68]. Significant over-representation (SIGORA) of pathway gene-pair signatures for the same group of genes was performed in package sigora (v.3.1.1) [16] in R environment, using KEGG and Reactome databases with FDR cutoff 0.05. Visualization of these results was performed using igraph package (v.2.1.4) [69].

STRING (v.12.0) [70] was queried using core genes from enriched pathways of SIGORA to acquire information on experimentally validated protein interactions. Network type was set to full STRING network, active interaction sources to ‘Experiments’, minimum required interaction score to medium confidence (0.4), while the network nodes were hidden and edges set to depict interaction score.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262110793/s1, references [11,12,14,71,72,73,74] are included.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J., D.S.-P., V.M.J., D.M.L.; methodology, D.M.L., V.M.J.; formal analysis, D.M.L.; investigation, D.M.L., B.J.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, B.J., D.S.-P., V.M.J., J.K., D.M.L.; D.M.L., B.J.; visualization, D.M.L., B.J.; supervision, D.S.-P., B.J.; funding acquisition D.S.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, Grant number #7754217, READ-DM1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA sequencing datasets that were analyzed are available through the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

Acknowledgments

We thank Lana Radenkovic (University of Belgrade-Faculty of Biology, Center for Human Molecular Genetics) for reading the manuscript and sharing useful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DM1 | Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| SR | Sarcoplasmic Reticulum |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| GS | Gene Significance |

| MM | Module Membership |

| ORA | Over-representation Analysis |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| SIGORA | Significant Over-representation Analysis |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| UPS | Ubiquitin-Proteasome System |

| ERAD | ER-Associated Degradation |

| qPCR | quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

References

- Brook, J.D.; McCurrach, M.E.; Harley, H.G.; Buckler, A.J.; Church, D.; Aburatani, H.; Hunter, K.; Stanton, V.P.; Thirion, J.-P.; Hudson, T.; et al. Molecular Basis of Myotonic Dystrophy: Expansion of a Trinucleotide (CTG) Repeat at the 3′ End of a Transcript Encoding a Protein Kinase Family Member. Cell 1992, 68, 799–808, Erratum in Cell 1992, 7, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Antonio, M.; Dogan, C.; Hamroun, D.; Mati, M.; Zerrouki, S.; Eymard, B.; Katsahian, S.; Bassez, G. Unravelling the Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Clinical Spectrum: A Systematic Registry-Based Study with Implications for Disease Classification. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 172, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić Pavićević, D.; Miladinović, J.; Brkušanin, M.; Šviković, S.; Djurica, S.; Brajušković, G.; Romac, S. Molecular Genetics and Genetic Testing in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. BioMed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 391821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranum, L.P.W.; Day, J.W. Myotonic Dystrophy: RNA Pathogenesis Comes into Focus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalsotra, A.; Xiao, X.; Ward, A.J.; Castle, J.C.; Johnson, J.M.; Burge, C.B.; Cooper, T.A. A Postnatal Switch of CELF and MBNL Proteins Reprograms Alternative Splicing in the Developing Heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20333–20338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Espinosa, J.; González-Barriga, A.; López-Castel, A.; Artero, R. Deciphering the Complex Molecular Pathogenesis of Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 through Omics Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankodi, A.; Logigian, E.; Callahan, L.; McClain, C.; White, R.; Henderson, D.; Krym, M.; Thornton, C.A. Myotonic Dystrophy in Transgenic Mice Expressing an Expanded CUG Repeat. Science 2000, 289, 1769–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Wei, C.; Iakova, P.; Bugiardini, E.; Schneider-Gold, C.; Meola, G.; Woodgett, J.; Killian, J.; Timchenko, N.A.; Timchenko, L.T. GSK3β Mediates Muscle Pathology in Myotonic Dystrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4461–4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, D.G.; Wieringa, B. Transgenic Mouse Models for Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2003, 100, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Cline, M.S.; Osborne, R.J.; Tuttle, D.L.; Clark, T.A.; Donohue, J.P.; Hall, M.P.; Shiue, L.; Swanson, M.S.; Thornton, C.A.; et al. Aberrant Alternative Splicing and Extracellular Matrix Gene Expression in Mouse Models of Myotonic Dystrophy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, M.K.; Tang, Z.; Thornton, C.A. Targeted Splice Sequencing Reveals RNA Toxicity and Therapeutic Response in Myotonic Dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 2240–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovyeva, E.M.; Utzinger, S.; Vissières, A.; Mitchelmore, J.; Ahrné, E.; Hermes, E.; Poetsch, T.; Ronco, M.; Bidinosti, M.; Merkl, C.; et al. Integrative Proteogenomics for Differential Expression and Splicing Variation in a DM1 Mouse Model. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2024, 23, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.M.; Frias, J.A.; Mishra, S.K.; Scotti, M.; Muscato, D.R.; Valero, M.C.; Adams, L.M.; Cleary, J.D.; Nakamori, M.; Wang, E.; et al. Alternative Splicing Dysregulation across Tissue and Therapeutic Approaches in a Mouse Model of Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa-Sàez, M.; Colom-Rodrigo, A.; González-Martínez, I.; Pérez-Gómez, R.; García-Rey, A.; Piqueras-Losilla, D.; Ballestar, A.; Llamusí, B.; Cerro-Herreros, E.; Artero, R. Use of HSALR Female Mice as a Model for the Study of Myotonic Dystrophy Type I. Lab. Anim. 2025, 54, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroushani, A.B.K.; Brinkman, F.S.L.; Lynn, D.J. Pathway-GPS and SIGORA: Identifying Relevant Pathways Based on the over-Representation of Their Gene-Pair Signatures. PeerJ 2013, 1, e229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimski, L.L.; Sabater-Arcis, M.; Bargiela, A.; Artero, R. The Hallmarks of Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Muscle Dysfunction. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Qi, L. Quality Control in the Endoplasmic Reticulum: Crosstalk between ERAD and UPR Pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meusser, B.; Hirsch, C.; Jarosch, E.; Sommer, T. ERAD: The Long Road to Destruction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Qu, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Noxon, I.C.; Schonhoft, J.D.; Plate, L.; Powers, E.T.; Kelly, J.W.; Lander, G.C.; Wiseman, R.L. The Endoplasmic Reticulum HSP 40 Co-chaperone ER Dj3/DNAJB 11 Assembles and Functions as a Tetramer. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2296–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blythe, E.E.; Olson, K.C.; Chau, V.; Deshaies, R.J. Ubiquitin- and ATP-Dependent Unfoldase Activity of P97/VCP•NPLOC4•UFD1L Is Enhanced by a Mutation That Causes Multisystem Proteinopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4380–E4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, A.; Malena, A.; Loro, E.; Del Moro, G.; Suman, M.; Pantic, B.; Szabadkai, G.; Vergani, L. Altered Ca2+ Homeostasis and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Muscle Cells. Genes 2013, 4, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi, S.; Fukuda, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Tsukada, S.; Yoshida, K. Gene Regulatory Network of Unfolded Protein Response Genes in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2013, 18, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezoe, K.; Nakamori, M.; Furuya, H.; Arahata, H.; Kanemoto, S.; Kimura, T.; Imaizumi, K.; Takahashi, M.P.; Sakoda, S.; Fujii, N.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Muscle. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 114, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, Y.; Yoshioka, K.; Suzuki, N. The Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Regulation of the Skeletal Muscle Homeostasis and Atrophy: From Basic Science to Disorders. J. Physiol. Sci. 2020, 70, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaldo, P.; Sandri, M. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Muscle Atrophy. Dis. Models Mech. 2013, 6, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignaud, A.; Ferry, A.; Huguet, A.; Baraibar, M.; Trollet, C.; Hyzewicz, J.; Butler-Browne, G.; Puymirat, J.; Gourdon, G.; Furling, D. Progressive Skeletal Muscle Weakness in Transgenic Mice Expressing CTG Expansions Is Associated with the Activation of the Ubiquitin–Proteasome Pathway. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010, 20, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, A.; Medja, F.; Nicole, A.; Vignaud, A.; Guiraud-Dogan, C.; Ferry, A.; Decostre, V.; Hogrel, J.-Y.; Metzger, F.; Hoeflich, A.; et al. Molecular, Physiological, and Motor Performance Defects in DMSXL Mice Carrying >1,000 CTG Repeats from the Human DM1 Locus. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1003043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilienbaum, A. Relationship between the Proteasomal System and Autophagy. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mikhail, A.I.; Manta, A.; Ng, S.Y.; Osborne, A.K.; Mattina, S.R.; Mackie, M.R.; Ljubicic, V. A Single Dose of Exercise Stimulates Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Plasticity in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Acta Physiol. 2023, 237, e13943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhoff, M.; Rion, N.; Chojnowska, K.; Wiktorowicz, T.; Eickhorst, C.; Erne, B.; Frank, S.; Angelini, C.; Furling, D.; Rüegg, M.A.; et al. Targeting Deregulated AMPK/mTORC1 Pathways Improves Muscle Function in Myotonic Dystrophy Type I. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Aierdi, A.J.; Goicoechea, M.; Aiastui, A.; Fernández-Torrón, R.; Garcia-Puga, M.; Matheu, A.; De Munain, A.L. Muscle Wasting in Myotonic Dystrophies: A Model of Premature Aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater-Arcis, M.; Bargiela, A.; Furling, D.; Artero, R. miR-7 Restores Phenotypes in Myotonic Dystrophy Muscle Cells by Repressing Hyperactivated Autophagy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 19, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Huang, X.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Y.; March, M.E.; Li, J.; Wei, Y. The Role of Autophagy in Skeletal Muscle Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 638983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Phogat, J.; Yadav, A.; Dabur, R. The Dependency of Autophagy and Ubiquitin Proteasome System during Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhail, A.I.; Nagy, P.L.; Manta, K.; Rouse, N.; Manta, A.; Ng, S.Y.; Nagy, M.F.; Smith, P.; Lu, J.-Q.; Nederveen, J.P.; et al. Aerobic Exercise Elicits Clinical Adaptations in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Patients Independently of Pathophysiological Changes. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e156125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, D.; Sorianello, E.; Segalés, J.; Irazoki, A.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Sala, D.; Planet, E.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Muñoz, J.P.; Sánchez-Feutrie, M.; et al. Mfn2 Deficiency Links Age-related Sarcopenia and Impaired Autophagy to Activation of an Adaptive Mitophagy Pathway. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1677–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarotto, L.; Metti, S.; Chrisam, M.; Cerqua, C.; Sabatelli, P.; Armani, A.; Zanon, C.; Spizzotin, M.; Castagnaro, S.; Strappazzon, F.; et al. Ambra1 Deficiency Impairs Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Yan, C.; Chen, M.; Feng, D.; Yan, C.; Wu, H.; Du, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. A Small Natural Molecule Promotes Mitochondrial Fusion through Inhibition of the Deubiquitinase USP30. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwach, A.; Patel, H.; Khairnar, A.; Parekh, P. Molecular Symphony of Mitophagy: Ubiquitin-Specific Protease-30 as a Maestro for Precision Management of Neurodegenerative Diseases. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeresh, P.; Kaur, H.; Sarmah, D.; Mounica, L.; Verma, G.; Kotian, V.; Kesharwani, R.; Kalia, K.; Borah, A.; Wang, X.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum–Mitochondria Crosstalk: From Junction to Function across Neurological Disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquim, M.; Altin, S.; Bulimaga, M.-B.; Simões, T.; Nolte, H.; Bader, V.; Franchino, C.A.; Plouzennec, S.; Szczepanowska, K.; Marchesan, E.; et al. Mitofusin 2 Displays Fusion-Independent Roles in Proteostasis Surveillance. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadiya, P.; Tomar, D. Mitochondrial Protein Quality Control Mechanisms. Genes 2020, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, B.; Li, N.; Wu, Y.; Jia, J.; Suo, T.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.-J.; Tang, J. RNF185, a Novel Mitochondrial Ubiquitin E3 Ligase, Regulates Autophagy through Interaction with BNIP1. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcetta, D.; Quirim, S.; Cocchiararo, I.; Chabry, F.; Théodore, M.; Stiefvater, A.; Lin, S.; Tintignac, L.; Ivanek, R.; Kinter, J.; et al. CaMKIIβ Deregulation Contributes to Neuromuscular Junction Destabilization in Myotonic Dystrophy Type I. Skelet. Muscle 2024, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Maier, L.S.; Dalton, N.D.; Miyamoto, S.; Ross, J.; Bers, D.M.; Brown, J.H. The δC Isoform of CaMKII Is Activated in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Induces Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hockerman, G.H.; Green, H.W.; Babbs, C.F.; Mohammad, S.I.; Gerrard, D.; Latour, M.A.; London, B.; Harmon, K.M.; Pond, A.L.; et al. Mergla K+ Channel Induces Skeletal Muscle Atrophy by Activating the Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1531–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabadkai, G.; Duchen, M.R. Mitochondria: The Hub of Cellular Ca2+ Signaling. Physiology 2008, 23, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, G.; Huang, T.; Zou, M.; Duan, S. The Biological Role of Arachidonic Acid 12-Lipoxygenase (ALOX12) in Various Human Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. The Role of Glutathione Peroxidase-1 in Health and Disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 188, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierke, C.T. The Role of Vinculin in the Regulation of the Mechanical Properties of Cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 53, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; He, H.; Xing, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gu, N.; Kenkichi, S.; Jiang, H.; Wu, Q. Expression of Non-Coding RNA AB063319 Derived from Rian Gene during Mouse Development. J. Mol. Hist. 2011, 42, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Hu, M.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, D.; Xu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Luan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; et al. LncRNAs Are Regulated by Chromatin States and Affect the Skeletal Muscle Cell Differentiation. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschdorf, J.P.; Li Chew, L.; Zhang, B.; Cao, Q.; Liang, F.-Y.; Liou, Y.-C.; Zhou, Y.T.; Low, B.C. Brain-Specific BNIP-2-Homology Protein Caytaxin Relocalises Glutaminase to Neurite Terminals and Reduces Glutamate Levels. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 3337–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pan, C.Q.; Chew, T.W.; Liang, F.; Burmeister, M.; Low, B.C. BNIP-H Recruits the Cholinergic Machinery to Neurite Terminals to Promote Acetylcholine Signaling and Neuritogenesis. Dev. Cell 2015, 34, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Hata, S.; Nakao, T.; Tanigawa, Y.; Oka, C.; Kawaichi, M. Cayman Ataxia Protein Caytaxin Is Transported by Kinesin along Neurites through Binding to Kinesin Light Chains. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 4177–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Bal, N.C.; Periasamy, M. Sarcolipin: A Key Thermogenic and Metabolic Regulator in Skeletal Muscle. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.J.; Lin, X.; Welle, S.; Sobczak, K.; O’Rourke, J.R.; Swanson, M.S.; Thornton, C.A. Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Impact of Toxic RNA in Myotonic Dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sugiura, Y.; Lin, W. The Role of Synaptobrevin1/VAMP1 in Ca2+-triggered Neurotransmitter Release at the Mouse Neuromuscular Junction. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 1603–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.; Krueger, F.; Segonds-Pichon, A.; Biggins, L.; Krueger, C.; Wingett, S. FastQC. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-Based Genome Alignment and Genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-Genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An Efficient General Purpose Program for Assigning Sequence Reads to Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- John, C.R.; Watson, D.; Russ, D.; Goldmann, K.; Ehrenstein, M.; Pitzalis, C.; Lewis, M.; Barnes, M. M3C: Monte Carlo Reference-Based Consensus Clustering. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape Provides a Biologist-Oriented Resource for the Analysis of Systems-Level Datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Use R!; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Csárdi, G.; Nepusz, T.; Traag, V.; Horvát, S.; Zanini, F.; Noom, D.; Müller, K. Igraph: Network Analysis and Visualization, R Package Version 2.1.4. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=igraph (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Jensen, L.J.; Kuhn, M.; Stark, M.; Chaffron, S.; Creevey, C.; Muller, J.; Doerks, T.; Julien, P.; Roth, A.; Simonovic, M.; et al. STRING 8—A Global View on Proteins and Their Functional Interactions in 630 Organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D412–D416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, A.; Szcześniak, M.W.; Sekrecki, M.; Kajdasz, A.; Sznajder, Ł.J.; Baud, A.; Sobczak, K. MBNL Splicing Factors Regulate the Microtranscriptome of Skeletal Muscles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 12055–12073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelbello, A.J.; Rzuczek, S.G.; Mckee, K.K.; Chen, J.L.; Olafson, H.; Cameron, M.D.; Moss, W.N.; Wang, E.T.; Disney, M.D. Precise Small-Molecule Cleavage of an r (CUG) Repeat Expansion in a Myotonic Dystrophy Mouse Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7799–7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Jenquin, J.R.; McConnell, O.L.; Cleary, J.D.; Richardson, J.I.; Pinto, B.S.; Haerle, M.C.; Delgado, E.; Planco, L.; Nakamori, M.; et al. A CTG Repeat-Selective Chemical Screen Identifies Microtubule Inhibitors as Selective Modulators of Toxic CUG RNA Levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 20991–21000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenquin, J.R.; Yang, H.; Huigens III, R.W.; Nakamori, M.; Berglund, J.A. Combination Treatment of Erythromycin and Furamidine Provides Additive and Synergistic Rescue of Mis-Splicing in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Models. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 2, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).