Abstract

For the treatment of inflammatory illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis and carditis, as well as cancer, several anti-inflammatory medications have been created over the years to lower the concentrations of inflammatory mediators in the body. Peptides are a class of medication with the advantages of weak immunogenicity and strong activity, and the phage display technique is an effective method for screening various therapeutic peptides, with a high affinity and selectivity, including anti-inflammation peptides. It enables the selection of high-affinity target-binding peptides from a complex pool of billions of peptides displayed on phages in a combinatorial library. In this review, we will discuss the regular process of using phage display technology to screen therapeutic peptides, and the peptides screened for anti-inflammation properties in recent years according to the target. We will describe how these peptides were screened and how they worked in vitro and in vivo. We will also discuss the current challenges and future outlook of using phage display to obtain anti-inflammatory therapeutic peptides.

1. Introduction

A number of diseases are driven by inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), cancer, and atherosclerosis, as well as autoimmune, respiratory, and cardiovascular diseases [1,2]. A complex network of numerous mediators, a variety of cells, and several pathways are involved in inflammation. Current therapy for inflammatory diseases is limited to steroidal and non-steroidal medications. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory drugs on the market and used in research usually have significant side effects, particularly when long-term use is involved [3,4].

Finding a safe and effective drug with which to control inflammation represents a significant challenge; therefore, many researchers are committed to developing anti-inflammation drugs. In the past few years, peptides have attracted increasing amounts of attention due to their specific biochemical and therapeutic features, such as diverse bio-functionalities based on their components (amino acids) and high binding affinity with specific targets in a wide range, even though small molecules still dominate the therapeutic industry [5,6]. Peptide discovery optimization has a significant resource advantage over small molecules; the relatively simple and increasing automation of the synthesis required facilitates the success of much smaller teams of medicinal chemists, many-fold smaller than the sizes necessary for a comparable effort in small molecules. A peptide drug is easy to produce and has a lower immunogenicity compared with the antibody. With the improvements made in this technology, the disadvantages of the peptide drug, such as it being membrane-impermeable and biologically unstable, can be solved under certain conditions by direct structural change, enzyme inhibitors, absorption enhancers, carrier systems, and transdermal delivery technologies, promoting peptide drug innovation [7].

Phage display is a powerful tool for developing new peptide drugs, as it can largely maintain the conformations and functions of the expressed protein and peptide simultaneously, thereby maximizing their retention of biological activities with little risk of the recombinant phage infecting the host [8]. The genes expressed on the surface of phages interact directly with various specific targets. For this reason, they are commonly used as a powerful high-throughput screening tool allowing the potential peptide to quickly connect to various specific cellular targets, including membrane receptors and enzymes [9]. To detect ligand–receptor interactions, the displayed phage can be screened against the target proteins immobilized on the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate. In this way, large peptide libraries can be presented on the surface of the phage and panned during repeated cycles, including binding, washing, elution, and amplification. After this, sequencing the genome of the gradually enriched phage provides the display peptide sequence, which can then be used to synthesize the peptide in recombinant or synthetic form. Finally, unique binding agents with a high affinity and specificity for the desired target can be identified [10]. Phage display peptide libraries usually contain up to 1010 diverse variants [9]; phages can appear with peptides of a variety of sizes and structures on their surfaces. Natural peptides that are directly separated using traditional separation methods, including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), are usually present in complex mixtures of biological components at relatively low concentrations. Phage display, on the other hand, is more effective and economical in selecting peptide ligands that interact with inflammatory mediators [11,12].

Therefore, it could be effective to use phage display technology to select peptides for anti-inflammation purposes. However, it remains unclear as to whether these peptides are effective candidates for developing medicine to treat disease clinically, which has practical value. In this review, we will summarize the peptides screened for anti-inflammation activity through the phage display technique. Then, we will discuss the current achievements, pros and cons, and prospects relating to this topic.

2. How to Use the Phage Display to Screen Peptides

The phage display method was first defined by G. P. Smith et al. in 1985 to express cloned antigens on the viral surface [13]. It is a combinatorial technology that has attracted a great deal of attention regarding its potential in the future of drug discovery. This method is a robust tool in drug discovery, principally for peptide drug identification. It enables researchers to construct libraries and rapidly isolate and identify specific protein interactions of molecular targets [14].

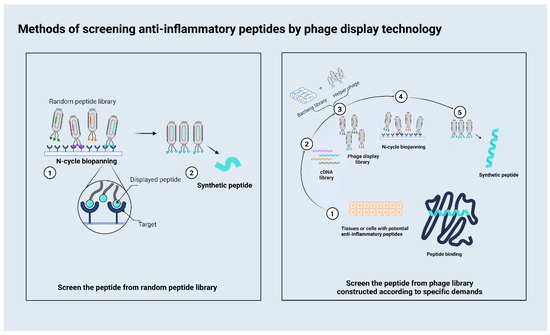

Current phage display systems are based on various bacteriophage vectors, including Ml3 phage, T7 phage, λ phage, and T4 phage display systems [15]. The M13 phage display is the most frequently used of these phage systems. There are two main methods used to screen out therapeutic peptides (Figure 1). One employs different targets to obtain a peptide from a random peptide library. In this method, researchers always use different targets associated with inflammation, and the phage display peptide library Ph.D.-7 is the most commonly used library. This method is relatively convenient because it does not require a phage library to be built. Another method involves constructing a phage according to specific demands. For example, some researchers want to obtain functional peptides from a mixture as with a natural product. They would use their mixture to construct a phage that could display these candidate peptides on the surface, then use the target for biopanning to obtain the peptides which have affinity with the target. For researchers aiming to build a new peptide library according to their demands, the T7 system is most likely to be used. As a phage display platform, M13 contains single-stranded DNA, whereas T7 contains double-stranded DNA, which exhibits increased stability and is less prone to mutation during replication. The T7 phage does not depend on a protein secretion pathway in the lytic cycle. Its display system inserts the gene that encodes the specific peptide into its genome so that the target peptide is fused to the C-terminus of the 10B capsid; thus, the target peptide is expressed on the surface of the phage particle, thereby avoiding problems associated with steric hindrance [16]. T7 phage particles exhibit a high stability under extreme conditions, such as high temperatures, and low pH values, which facilitates effective high-throughput affinity elutriation [17].

Figure 1.

This figure depicts the two most commonly used methods for screening anti-inflammatory therapeutic peptides. The left is the flowchart of screening the peptide from the random peptide library; the right is the flowchart of screening the peptide from the construct library.

Although the techniques used to screen the peptides are different, the methods followed to verify their function are quite similar. Firstly, researchers need to verify the affinity between the target and the peptides. Surface plasmon resonance technology (SPR), a major tool used for characterizing and quantifying interactions between biomolecules, is the commonly used and effective way to confirm this affinity. SPR is a technology developed in the 1990s [18], which can monitor the dynamic interaction between ligands and receptors in a fluid environment in real time, so that the affinity constants between ligands and receptors can be calculated [19]. Besides SPR, there are other means to examine the affinity, such as coimmunoprecipitation, but SPR is the most common method used in recent years because it offers exceptional advantages such as being label-free, being able to be used in situ, and providing real-time measurement ability [20].

After confirming the peptides’ affinity, various animal disease models, such as collagen-induced arthritis, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced paw edema, carrageenan-induced paw edema, etc., can be used to verify peptides’ anti-inflammatory activity. In their study, Vogel et al. [21] described many kinds of in vivo and in vitro methods that are used for the pre-clinical assessment of anti-inflammatory drugs. Kalpesh et al. [22] then summarized the advantages and limitations of these animal disease models, so we will not go into detail here.

3. The Peptides Obtained according to Different Targets Related to Inflammation

Below, we have listed nearly all the peptides screened for their anti-inflammation properties through phage display in the last 10 years (Table 1). These do not work identically on disease models. The different functions of these peptides depend on the variety of specific targets related to inflammation. According to their different targets, we evaluated some of the peptides screened out for anti-inflammatory properties by describing their screening mechanisms and mechanisms of action in vitro and in vivo.

Table 1.

The peptides screened for anti-inflammation properties in recent years.

3.1. TNFR1

Primary inflammatory stimuli, including microbial products and cytokines, which mediate inflammation through interaction with the toll-like receptors (TLRs), IL-1 receptor (IL-1R), IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), and the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) [57], can trigger significant intracellular signaling pathways, including the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer, and activator of transcription (STAT) pathways [58,59,60]. To obtain peptides to antagonize the factors in these inflammatory pathways, many researchers have employed inflammatory pathway-related factors as targets to screen the peptides that have an affinity with these factors through phage display. These affinity peptides might have the ability to inhibit downstream signaling pathways and thus could reduce the inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo.

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) is a multifunctional cytokine [61] which can control the inflammatory process caused by bacterial and viral infections and promote autoimmune diseases as well as cancer [62,63,64]. The biological functions of TNF-α are mediated by two different receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2, in the cell membrane. To return to homeostasis, the mechanisms that shut down the inflammatory response are of paramount importance [65]. The current research on this topic is focusing on anti-inflammatory drug trends, aiming to identify new small molecules that can directly bind to TNF-α and/or TNFR1 to prevent TNF-α from interacting with TNFR1, thus modulating downstream signaling pathways [66].

However, inhibiting TNF-α occasionally has negative effects, including enabling life-threatening infections, and the reactivation of hepatitis B and tuberculosis [67,68]. In addition, TNF-α blockers cannot show efficacy in diseases where TNF-α acts as a disease-promoting factor, including multiple sclerosis and heart failure. This may reflect the fact that TNF-α blockers prevent not only TNFR1 signal transduction but also the activation of TNFR2 [69,70]. Specifically blocking sTNF/TNFR1 signaling while maintaining the functioning of tmTNF/TNFR2 signaling appears to be adequate to interfere with pathological TNF signaling. The side effects of this class of therapeutics may be less severe than those associated with global TNF blockers that neutralize sTNF and tmTNF and may be effective therapeutic for other diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS) and neurodegenerative diseases, where it is not recommended to completely inhibit TNF [71].

Therefore, many researchers have used TNFR1 as the target for developing alternative therapeutic interventions rather than TNF-α [72,73]. A peptide Hydrostatin-SN1 (H-SN1) screened from the snake venom of Hydrophis cyanocinctus phage libraries not only verified the affinity between SN-1 and TNFR1 but also inhibited the binding between TNF-α with TNFR1 in SPR. Moreover, its anti-inflammatory activities have been verified. H-SN1 suppressed TNFR1-associated signaling pathways by decreasing NF-кB activation and MAPK signaling in HEK293 embryonic kidney and HT29 adenocarcinoma cell lines induced by TNF-α. It has also been found to have an effect in vivo by researchers, using a murine model of acute colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate, showing that H-SN1 lowered the disease activity index and histological scores in acute colitis and that it could inhibit TNF/TNFR1 downstream targets at both the mRNA and protein levels [74]. The follow-up research on this topic used LPS-induced ALI, LPS-induced bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) cells, and IL-10 knockout mice to test H-SN1’s anti-inflammatory activity; the results suggested that H-SN1 has significant anti-inflammatory effects, both in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating H-SN1 to be a suitable candidate for use in the treatment of TNF-α-associated inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel diseases [24,75]. In addition to H-SN1, A 41-amino acid peptide named DAvp-1 employed TNFR1 as the target, screening it from the T7 phage library of Deinagkistrodon acutus venom glands [23]. WH701 was screened from the phage 6-mer peptide library, which is a kind of random library. DAvp-1 and WH701 can both specifically bind to TNFR1 [76,77].

Apart from the peptides screened from the constructed natural product library and random peptide library, a TNFR1-selective antagonistic mutant TNF-α (R1antTNF) was screened from the TNF variant phage library. This research constructed phage libraries which could display the structural TNF variants, where the six amino acid residues (amino acids 29, 31, 32, 145–147, library I; amino acids 84–89, library II) in the predicted receptor binding sites of TNF were replaced with other amino acids. Thus, these phages include many kinds of TNF variant phages. R1antTNF is one TNF variant that can bind with TNFR1 without activating it. This research employed human TNFR1 Fc chimera, which had the same function as TNFR1 but was harder to degrade and easier to separate and purify. According to the results obtained from SPR and x-ray crystallography experiments, although its affinity for the TNFR1 was almost the same as that of the human wild-type TNF, R1antTNF did not activate TNFR1-mediated responses. It also neutralized the TNFR1-mediated bioactivity of wild-type TNF without influencing its TNFR2-mediated bioactivity and could inhibit hepatic injury in an animal model [52]. In later research, the researcher used two independent experimental models induced by carbon tetrachloride or concanavalin A, demonstrating that R1antTNF might be a clinically useful TNF-a antagonist in hepatitis [53]. Referring to the example above, the peptides which blocked TNFR1 had great potential in clinical drug research and development.

3.2. CD40

CD40 is an important target belonging to the TNFR family. The CD40/CD40 ligand (CD40L) dyad plays a significant role in several immunogenic and inflammatory processes, including atherosclerosis [78,79,80]. CD40 is expressed by different kinds of cell types relevant to atherosclerosis, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes. CD40 ligation induces a series of inflammatory and apoptotic mediators; hence, CD40 signaling has been associated with the pathophysiology of immunodeficiency, neurodegenerative disorders, collagen-induced arthritis, graft-versus-host disease, atherosclerosis, and cancer. Blocking CD40/CD40L signaling by monoclonal antibodies was shown to be beneficial in the treatment of arthritis and atherosclerosis by disrupting CD40 function, and CD40 has been a key immunotherapeutic target for over 20 years [81].

NP31, which contains a randomized linear 15-mer amino acids peptide sequence, was screened from the human pIF15 phage library using CD40-murine IgG as the target. NP31 inhibits VEGF and IL-6 transcriptional activation and decreases IL-6 production by CD40L-activated endothelial cells. In particular, NP31 was found not only to alter the biodistribution profile of a streptavidin scaffold but also to significantly increase the accumulation of the carrier in aged apolipoprotein e (ApoE) mice with atherosclerosis lesions in a CD40-dependent manner [45]. These instances demonstrate that CD40 could be an available target for screening anti-inflammatory peptides.

3.3. IL-17

T helper (Th) cells differ in their cytokine profiles, which identify their subsets. Th1 cells have the characteristics of secret Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and TNF-α [82,83]. After the discovery of the Th1 dichotomy, many other Th subsets were discovered, each one having identical functional properties, cytokine profiles, and roles in autoimmune tissue pathology. These Th subsets include Th17 cells, which can produce IL-17 [84].

The IL-17 cytokine family consists of six polypeptides, IL-17A-F, and five receptors, IL-17RA-E1 [85]. This family of cytokines comprises potent inflammatory mediators involved in host defense against extracellular bacteria, fungi, and other eukaryotic pathogens, in which IL-17 cytokines have been implicated in a broad spectrum of inflammatory conditions and autoimmune diseases [86]. IL-17A signals through a specific cell surface receptor complex, which consists of IL-17RA and IL-17RC3, and its downstream signaling leads to an increased production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, CCL-20, and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1(CXCL1) through different kinds of mechanisms, such as the stimulation of transcription and the stabilization of mRNA [87,88,89]. IL-17A and its signaling are significant aspects of host defense against certain fungal and bacterial infections [90,91], and it is an important pathogenic factor in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Furthermore, inhibiting IL-17A has preclinical and clinical efficacies in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis [92,93,94].

HAP is an IL-17A peptide antagonist which was obtained through phage display. Screening followed by saturation mutagenesis optimization and amino acid substitutions produced HAP, which has a high affinity with IL-17A and is able to inhibit the interaction of the cytokine with its receptor, IL-17RA [40]. In the other example, P725 was selected from the phage library of random linear heptapeptides based on their affinity for the target (extracellular domain of IL-7RA, which contains a fibronectin type III repeat-like sequence). P725 had a strong ability to compete with IL-7 for IL-7RA binding sites and can prevent the signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 activations induced by IL-7 in 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (ADC)-stimulated Jurkat cells; thus, it could be a good candidate for blocking applications [41].

3.4. IFN-α

IFN-α is a member of the type I IFN family, and IFN-α encompasses 13 partially homologous IFN-α protein subtypes encoded by several genes in humans. All members of this family signal through interferon alpha/beta receptor (IFNAR), a heterodimeric transmembrane receptor comprising IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits, which associate upon ligand binding to activate the protein tyrosine JAK1 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2). This can lead to the phosphorylation of signal transducer and STAT1 and STAT2. Finally, it can associate with IFN regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) and form the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). The latter induces the transcription of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), with subsequent immunomodulatory effects on both innate and adaptive immune responses [95,96,97]. The IFN pathway, particularly well-documented for IFN-α, has emerged as a major driver of several autoimmune rheumatic diseases encompassing, but not restricted to, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [98], Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) [99], systemic sclerosis (SSc) [100], and dermatomyositis (DM) [101]. A large amount of evidence supports the important role played by IFN-α in the pathophysiology of several rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Specifically targeting IFN-α or its receptor appears to be a valid approach to ensure its sustained anti-inflammatory efficacy in most patients [102]. To screen a novel IFN-α/β signaling inhibitor to decrease the skin lesions in imiquimod (IMQ) and 12-O- tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) mice models of psoriasis, one researcher used rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-human IFNα1 as their target to obtain phage peptides (Phpep3D). The derived peptide (Pep3D) reduced skin thickness, redness, and acanthosis despite the presence of the psoriasis inducers IMQ and TPA. Pep3D has also been found to reduce the number of GR1+ infiltrated cells and decrease the production of IL-17A and TNF-α in the psoriatic skin of mice; thus, Pep3D has the potential to be used as a new drug for psoriasis [26], and this demonstrates IFN-α as an effective target.

3.5. MMP

In normal cases, TNF-α acts as an immune modulator, and it is a potent inducer of numerous metalloproteinases (MMPs), pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesive molecules, and chemokines, in which MMPs could increase inflammation [31]. As a kind of zinc-dependent endopeptidase, MMPs break down diverse extracellular matrix compounds [103]. This family of enzymes has multiple common domains in their structure, including a pro-peptide domain, a catalytic domain, and a hemopexin domain in C-terminus, and a fibronectin domain only in MMP-2 and MMP-9 [104]. MMP-2 is an anti-cancer drug target in several aggressive tumors, whereas MMP-9 inhibitors may prove useful in treating cancer in its early stages as well as multiple autoimmune diseases [105]. Abnormal expressions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are significant factors in some diseases, and so developing an effective inhibitor for the specific and selective inhibition of gelatinases would be helpful. In a study, the researcher chose MMP-2 as a target, to obtain an MMP inhibitor M219hy [32]. In another study, the researcher selected RSH-12 from a library of random 12-mer peptides. RSH-12 could decrease the gelatin degradation by preventing gelatin combinate with MMP-9 and MMP-2. Selective gelatinase inhibitors might prove the usefulness of the new peptide discovered in tumor targeting and anticancer and anti-inflammation therapy [31].

3.6. Complement Component 3a (C3a)

The complement system is a significant participant in the innate immune response, where it serves as the initial line of defense against invading pathogens [106]. It might play a crucial role in the immune response and host defense by mediating the activation of immune cells and the eradication of infections [107]. C3a is a thoroughly studied anaphylatoxin that induces proinflammatory reactions together with complement component 5a (C5a). When C3a binds to its receptor, signaling cascades involving C3a are activated, which results in the generation of cytokines and other pro-inflammatory responses. For inflammatory conditions including sepsis and asthma, the inhibition of dysregulated complement activity has been viewed as a possible treatment strategy. This study described the creation of a protein binder that is unique to human C3a (hC3a) and may effectively reduce pro-inflammatory reactions. Six variable sites in the neighboring LRRV2 and LRRV3 modules were subjected to random mutations in order to create a library. Preventing the interaction between hC3a and its receptor, Rb1-H12, which was created through biopanning, had a notable suppressive impact on the proinflammatory response in monocytes. Its specificity to hC3a was shown to be more than ten times greater than that of human C5a [29].

3.7. GPR1

GPR1 is a receptor for chemokine-like peptide (chemerin), which is crucial for metabolism and reproduction [108]. Recent studies have shown that GPR1 promotes cancer cell proliferation and invasion in choriocarcinoma cells and gastric cancer cells [109]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has shown a correlation between TNBC and GPR1, especially in TNBC cell lines. TNBC and GPR1 have been shown to be strongly expressed in breast cancer tissue and cell lines, especially in TNBC cell lines [110]. The GPR1-specific peptide LRH7-G5, which competes with chemerin to block chemerin/GPR1 signaling, was screened from the Ph.D.-7 random phage library. The anti-tumor response of this peptide was found to be dose-dependent, inhibiting the proliferation of TNBC cell lines MDA-MB-231 and HCC1937 and suppressing tumor growth, but not T47D cells, through phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT) signaling [30].

3.8. CD14

LPS, or endotoxin, is the major structural and functional component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [111,112], which has been recognized as the principal component responsible for causing ALI/ acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). These complex macromolecules exhibit a variety of toxic and proinflammatory activities [113]. The proinflammatory role of such low-level LPS relies on the endotoxin-sensitivity enhancing system, LBP/CD14, which is located upstream of the proinflammatory signal path and can pass on and proliferate the LPS proinflammatory signal. Thus, antagonism of the endotoxin-sensitivity enhancing system, LBP/CD14, can efficiently inhibit the proinflammatory role of LPS [114].

In one example, phage display peptide library, phages ELISA and LBP competitive inhibition experiments and DNA screening for testing sequence were jointly adopted, along with the attainment of mimetic peptide sequences (MP12). In both in vivo and in vitro experiments, the biological activity of LPS to cause inflammation was blocked by MP12 and rats suffering from LPS-type ALI were protected by MP12 [115]. In another example, Polypeptide P1, which competes with LBP for CD14 binding, was obtained by screening from a mutant phage display library. It was shown to use error-prone polymerase chain reaction (PCR), induce mutations in the C-terminus of LBP, and attach PCR products to T7 phages. P1 could inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α expression and NF-kB activity in U937 cells and improve arterial oxygen pressure, oxygenation index, and lung pathology scores in rats with LPS-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [44]. Furthermore, the researcher could use LPS specific antibody as the target to obtain LPS peptide mimics from Ph.D.™-7 Phage Display Peptide Library. This peptide also exhibits certain anti-inflammatory activity [49].

3.9. Cell

In addition to proteins, cells can also be used as targets. Using PBMCs as the target could allow us to obtain the heptapeptide HP3 from phage display peptide library Ph.D.-7. HP3 was found to block mononuclear cell adhesion to endothelial cells and inhibit trans-endothelial migration in vitro. The activity of the heptapeptide in a murine model of psoriasis was also assessed, indicating that early administration inhibited the development of psoriatic lesions. Therefore, the results suggested that HP3 may serve as a potential therapeutic target for psoriasis [28].

3.10. Others

The above studies uniformly demonstrate that the use of phage display technology to obtain anti-inflammatory peptides is efficient and feasible. The principle of screening is basically to use antagonists of screening targets to antagonize the inflammatory response. Most of these peptides would be used directly after the screening; however, some therapeutic peptides are not directly screened from phages, with researchers instead using peptides screened through phage display and corresponding with other decorations to qualify these peptides. For example, CVX51401 is a Cav modulator that reduces VEGF and immune-mediated inflammation, which fuses RRPPR with a minimal Cav inhibitory domain. In CVX51401, RRPPR was screened from random phage libraries; it was found to be able to internalize efficiently and was demonstrated to be potent in blocking NO release. Caveolin (Cav) regulates various aspects of endothelial cell signaling and cell-permeable peptides (CPPs) fused to domains of Cav can reduce retinal damage and inflammation in vivo. Thus, CVX51401 dose-dependently blocked NO release, VEGF-induced permeability, and retinal damage in a model of uveitis [25]. Taking R1antTNF, which is discussed above, as an example, the molecular stability and bioactivity were improved by converting the homotrimeric R1antTNF into a single-chain derivative (scR1antTNF) through the introduction of short peptide linkers of 5 or 7 residues between the three protomers [116]. The researcher also engineered polyethylene glycol (PEG)-modified R1antTNF (PEG–R1antTNF) to improve stability. As a result of its long plasma half-life, PEG–R1antTNF improved the incidence and clinical score of arthritis. In particular, PEG–R1antTNF showed a greater therapeutic effect than Etanercept in therapeutic protocols. Additionally, it did not reactivate viral infection, unlike Etanercept [54]. This combination means that polypeptides will have more functions and may increase the peptides’ permeability, validity, and stability.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Due to its advantages of a large screening capacity, enabling mass production through fermentation, being high-throughput, and having a straightforward method of execution, phage display has been widely used in bioengineering and biomedicine, especially for diagnostics and therapeutics. With the advent of next-generation sequencing and microfluidic technologies, phage display has become an even more powerful and popular tool for use in drug discovery and development.

However, it also has some limitations. In some constructed libraries, because the peptides displayed on the surface of phages lack modification and the original peptides conformations are different to a certain extent, constructed libraries cannot fully display the original conformations of peptides in vivo. Although the screened peptides have a binding force, they might not play an antagonistic role or even have a therapeutic function. For example, using semaphorin 3F (SEMA3F)/plexin-A2 as the target to screen a peptide with affinity, researchers obtained four peptides AV1, AV2, AcBl3, and AcBl4, which have affinity but which cannot be used in an animal model [117]. We believe there are many peptides, that have not yet been reported, that do not have anti-inflammatory function despite being an inhibitor of the target. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the screening techniques through designs based on experience. Some researchers have combined phage display with other techniques, such as high-throughput sequencing [118], which could help us to better understand and categorize phages after screening.

The therapeutic peptide market is an emerging field that is currently growing, and there are some problems relating to peptide drugs that still need to be solved. For example, the pharmacokinetic properties, the cost of synthetic peptides, and the delivery of peptides to their specific target need to be improved [119,120,121], as these are technical hurdles to the development of more effective peptide-based therapeutics.

Nevertheless, the natural sources or random libraries from which active peptides can be isolated are virtually unlimited. Thus, the appearance of new peptides will not stop soon. According to Craik et al., the market for protein and peptide-based drugs represents about 10% of the total pharmaceutical market, and this proportion is still increasing [120]. Numerous scientific publications demonstrate the intense basic research that is currently taking place in this field, with thousands of peptides being studied as we write, of which 400 to 600 are enrolled in preclinical studies [122]. Although more researchers have used phage displays to screen peptides with anti-inflammatory properties over the past 20 years, the anti-inflammatory peptides developed as drugs are frequently only tested in cells and animals, and clinical trials are required to verify their efficacy. Further research is still needed to improve the effectiveness of screening and the use of peptides as anti-inflammatory drugs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z. and Y.L.; methodology, K.Z. and Y.L.; validation, Y.L. and Y.T.; investigation, K.Z. and Y.L.; resources, K.Z. and Y.L.; data curation, K.Z. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, K.Z., Y.L., Q.C. and Y.T.; visualization, K.Z. and Y.L.; supervision, K.Z., Y.L. and Y.T.; project administration, Y.L., Q.C. and Y.T.; funding acquisition, Y.L., Q.C. and Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China: 2018YFB1304702; National Natural Science Foundation of China: 31970423; National Natural Science Foundation of China: 32071242; Nature Science Foundation of Sichuan Province: 2022NSFSC0579.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Carmeliet, P. Mechanisms of Disease: Hypoxia and Inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, A.T.; Gohil, V.M.; Bhutani, K.K. Modulating TNF-alpha signaling with natural products. Drug Discov. Today 2006, 11, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamley, I.W. Small Bioactive Peptides for Biomaterials Design and Therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 14015–14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morimoto, B.H. Therapeutic peptides for CNS indications: Progress and challenges. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2859–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, B.J.; Miller, G.D.; Lim, C.S. Basics and recent advances in peptide and protein drug delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2013, 4, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, P.; Han, L.; Wang, F.; Petrenko, V.A.; Liu, A.H. Gold nanoprobe functionalized with specific fusion protein selection from phage display and its application in rapid, selective and sensitive colorimetric biosensing of Staphylococcus aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 82, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.P.; Petrenko, V.A. Phage display. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, E.; Arap, W.; Rajotte, D.; Lahdenranta, J.; Pasqualini, R. Identification of receptor ligands with phage display peptide libraries. J. Nucl. Med. 1999, 40, 883–888. [Google Scholar]

- Sclavons, C.; Burtea, C.; Boutry, S.; Laurent, S.; Elst, L.V.; Muller, R.N. Phage Display Screening for Tumor Necrosis Factor- alpha -Binding Peptides: Detection of Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Hepatitis. Int. J. Pept. 2013, 2013, 348409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chirinos-Rojas, C.L.; Steward, M.W.; Partidos, C.D. A peptidomimetic antagonist of TNF-alpha-mediated cytotoxicity identified from a phage-displayed random peptide library. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 5621–5626. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.P. Filamentous fusion phage-novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science 1985, 228, 1315–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, I.; Tufekci, K.U.; Karaca, E.; Genc, S.; Genc, K. Peptide Derivatives of Erythropoietin in the Treatment of Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. In Therapeutic Proteins and Peptides; Donev, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 112, pp. 309–357. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.Y.; Tian, T.; Liu, W.L.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, C.Y.J. Advance in phage display technology for bioanalysis. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 11, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, S.; Belasco, J.G. T7 phage display: A novel genetic selection system for cloning RNA-binding proteins from cDNA libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12954–12959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, X.Y.; Wang, L.; You, X.L.; Dai, P.; Zeng, Y.H. Advances in the T7 phage display system. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Homola, J.; Yee, S.S.; Gauglitz, G. Surface plasmon resonance sensors: Review. Sens. Actuator B Chem. 1999, 54, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.J.; Frazier, R.A.; Shakesheff, K.M.; Davies, M.C.; Roberts, C.J.; Tendler, S.J.B. Surface plasmon resonance analysis of dynamic biological interactions with biomaterials. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.O.; Pandey, G.R.; Patil, A.G.; Borse, V.B.; Deshmukh, P.K.; Patil, D.R.; Tade, R.S.; Nangare, S.N.; Khan, Z.G.; Patil, A.M.; et al. Graphene-based nanocomposites for sensitivity enhancement of surface plasmon resonance sensor for biological and chemical sensing: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 139, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boominathan, R.; Parimaladevi, B.; Mandal, S.C.; Ghoshal, S.K. Anti-inflammatory evaluation of Ionidium suffruticosam Ging. in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.R.; Mahajan, U.B.; Unger, B.S.; Goyal, S.N.; Belemkar, S.; Surana, S.J.; Ojha, S.; Patil, C.R. Animal Models of Inflammation for Screening of Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Implications for the Discovery and Development of Phytopharmaceuticals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, K.R.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.Z. Screening of TNFR1 Binding Peptides from Deinagkistrodon acutus Venom through Phage Display. Toxins 2022, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Li, A.; Sun, K.; Qiu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Lu, Y. Anti-Inflammatory Activity and Mechanism of Hydrostatin-SN1 From Hydrophis cyanocinctus in Interleukin-10 Knockout Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, P.N.; Tao, B.; Bradshaw, R.A.; Eveleth, D.; Sessa, W.C. Characterization of a Novel Caveolin Modulator That Reduces Vascular Permeability and Ocular Inflammation. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapi-Colin, L.A.; Gutierrez-Gonzalez, G.; Rodriguez-Martinez, S.; Cancino-Diaz, J.C.; Mendez-Tenorio, A.; Perez-Tapia, S.M.; Gomez-Chavez, F.; Cedillo-Pelaez, C.; Cancino-Diaz, M.E. A peptide derived from phage-display limits psoriasis—Like lesions in mice. Heliyon 2020, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, M.H.; Fan, X.B.; Xu, W.; Zhang, R.; Wu, G.Q. A novel peptide binding to the C-terminal domain of connective tissue growth factor for the treatment of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 1464–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Sanchez, E.A.; Mendoza-Figueroa, J.S.; Gutierrez-Gonzalez, G.; Zapi-Colin, L.A.; Torales-Cardena, A.; Briseno-Lugo, P.E.; Diaz-Toala, I.; Cancino-Diaz, J.C.; Perez-Tapia, S.M.; Cancino-Diaz, M.E.; et al. Heptapeptide HP3 acts as a potent inhibitor of experimental imiquimod-induced murine psoriasis and impedes the trans-endothelial migration of mononuclear cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.-K.; Son, S.; Choi, Y.; Hwang, D.-E.; Seo, H.-D.; Lee, J.-J.; Kim, H.-S. Effective inhibition of C3a-mediated pro-inflammatory response by a human C3a-specific protein binder. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 1904–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Dai, X.-Y.; Cai, J.-X.; Chen, J.; Wang, B.B.; Zhu, W.; Wang, E.; Wei, W.; Zhang, J.V. A Screened GPR1 Peptide Exerts Antitumor Effects on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2020, 18, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoari, A.; Rasaee, M.J.; Kanavi, M.R.; Daraei, B. Functional mimetic peptide discovery isolated by phage display interacts selectively to fibronectin domain and inhibits gelatinase. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 19699–19711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maola, K.; Wilbs, J.; Touati, J.; Sabisz, M.; Kong, X.D.; Baumann, A.; Deyle, K.; Heinis, C. Engineered Peptide Macrocycles Can Inhibit Matrix Metalloproteinases with High Selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2019, 58, 11801–11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, R.; Huang, N.; et al. Alternaria B Cell Mimotope Immunotherapy Alleviates Allergic Responses in a Mouse Model. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Soler, M.; Gehring, M.P.; Lechtenberg, B.C.; Zapata-Mercado, E.; Hristova, K.; Pasquale, E.B. Engineering nanomolar peptide ligands that differentially modulate EphA2 receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 8791–8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koolpe, M.; Dail, M.; Pasquale, E.B. An ephrin mimetic peptide that selectively targets the EphA2 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46974–46979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Sha, J.C.; Wang, H.; An, L.F.; Liu, T.; Li, L. P-FN12, an H4R-Based Epitope Vaccine Screened by Phage Display, Regulates the Th1/Th2 Balance in Rat Allergic Rhinitis. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 11, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Dwyer, R.; Kovaleva, M.; Zhang, J.; Steven, J.; Cummins, E.; Luxenberg, D.; Darmanin-Sheehan, A.; Carvalho, M.F.; Whitters, M.; Saunders, K.; et al. Anti-ICOSL New Antigen Receptor Domains Inhibit T Cell Proliferation and Reduce the Development of Inflammation in the Collagen-Induced Mouse Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, E.; Moss, A.J.; Fischer, M.; Kang, M.; Ahmed, S.; Farah, H.; Bate, N.; Giakomidi, D.; Brindle, N.P.J. Development of an Orthogonal Tie2 Ligand Resistant to Inhibition by Ang2. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 3962–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.; Wald, H.; Vaizel-Ohayon, D.; Grabovsky, V.; Oren, Z.; Karni, A.; Weiss, L.; Galun, E.; Peled, A.; Eizenberg, O. Development of novel Promiscuous anti-chemokine Peptibodies for Treating autoimmunity and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Desharnais, J.; Sahasrabudhe, P.V.; Jin, P.; Li, W.; Oates, B.D.; Shanker, S.; Banker, M.E.; Chrunyk, B.A.; Song, X.; et al. Inhibiting complex IL-17A and IL-17RA interactions with a linear peptide. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtea, C.; Laurent, S.; Sanli, T.; Fanfone, D.; Devalckeneer, A.; Sauvage, S.; Beckers, M.-C.; Rorive, S.; Salmon, I.; Elst, L.V.; et al. Screening for peptides targeted to IL-7R alpha for molecular imaging of rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, E.R.; Fujimura, P.T.; Araujo, G.R.; Silva, C.A.T.D.; Silva, R.L.; Cunha, T.M.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Lima, C.; Ferreira, M.J.; Cunha-Junior, J.P.; et al. A Short Peptide That Mimics the Binding Domain of TGF-beta 1 Presents Potent Anti-Inflammatory Activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, W.W.; Lu, S.; Su, Y.J.; Xue, D.; Yu, X.L.; Wang, S.W.; Zhang, H.; Xu, P.X.; Xie, X.X.; Liu, R.T. Decreasing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation with a multifunctional peptide rescues memory deficits in mice with Alzheimer disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 74, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, G.S.; Ji, F.Y.; Mei, C.X.; Liu, J.; Wu, G.M. Directed Evolution of an LBP/CD14 Inhibitory Peptide and Its Anti-Endotoxin Activity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Segers, F.; Sliedregt-Bol, K.; Bot, I.; Woltman, A.M.; Boross, P.; Verbeek, S.; Overkleeft, H.; Marel, G.A.V.D.; Kooten, C.V.; et al. Identification of a novel CD40 ligand for targeted imaging of inflammatory plaques by phage display. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 4136–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houimel, M.; Mazzucchelli, L. Chemokine CCR3 ligands-binding peptides derived from a random phage-epitope library. Immunol. Lett. 2013, 149, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolg, C.; Hamilton, S.R.; Zalinska, E.; McCulloch, L.; Amin, R.; Akentieva, N.; Winnik, F.; Savani, R.; Bagli, D.J.; Luyt, L.G.; et al. A RHAMM Mimetic Peptide Blocks Hyaluronan Signaling and Reduces Inflammation and Fibrogenesis in Excisional Skin Wounds. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1250–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanger, K.; Steffek, M.; Zhou, L.; Pozniak, C.D.; Quan, C.; Franke, Y.; Tom, J.; Tam, C.; Elliott, J.M.; Lewcock, J.W.; et al. Allosteric peptides bind a caspase zymogen and mediate caspase tetramerization. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, A.; Rajoria, S.; George, A.L.; Mittelman, A.; Suriano, R.; Tiwari, R.K. Synthetic Toll Like Receptor-4 (TLR-4) Agonist Peptides as a Novel Class of Adjuvants. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Segers, F.M.E.; Yu, H.; Molenaar, T.J.M.; Prince, P.; Tanaka, T.; Berkel, T.J.C.V.; Biessen, E.A.L. Design and Validation of a Specific Scavenger Receptor Class AI Binding Peptide for Targeting the Inflammatory Atherosclerotic Plaque. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, Y.; Sun, H.-X.; Li, X.-Y.; Mo, X.-M.; Zhang, G. Screening for a Peptide That Inhibits Expression of a Broad-spectrum of Chemokines Using Models of Endotoxin Tolerance and LIPS-induced Pro-inflammation. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 40, 461–470. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ohkawa, A.; Minowa, K.; Mukai, Y.; Abe, Y.; Taniai, M.; Nomura, T.; Kayamuro, H.; Nabeshi, H.; et al. Creation and X-ray structure analysis of the tumor necrosis factor receptor-1-selective mutant of a tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shibata, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ohkawa, A.; Abe, Y.; Nomura, T.; Mukai, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Taniai, M.; Ohta, T.; Mayumi, T.; et al. The therapeutic effect of TNFR1-selective antagonistic mutant TNF-alpha in murine hepatitis models. Cytokine 2008, 44, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Abe, Y.; Ohkawa, A.; Nomura, T.; Minowa, K.; Mukai, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Taniai, M.; Ohta, T.; et al. The treatment of established murine collagen-induced arthritis with a TNFR1-selective antagonistic mutant TNF. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6638–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, T.; Arisawa, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Hirata, I.; Nakano, H.; Sawada, M. Identification of ligands binding specifically to inflammatory intestinal mucosa using phage display. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007, 34, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, T.J.M.; Appeldoorn, C.C.M.; Haas, S.A.M.D.; Michon, N.N.; Bonnefoy, A.; Hoylaerts, M.F.; Pannekoek, H.; Berkel, T.J.C.V.; Kuiper, J.; Biessen, E.A.L. Specific inhibition of P-selectin-mediated cell adhesion by phage display-derived peptide antagonists. Blood 2002, 100, 3570–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaminska, B. MAPK signalling pathways as molecular targets for anti-inflammatory therapy—From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic benefits. BBA Proteins Proteom. 2005, 1754, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrayani, S.F.; Al-Harbi, B.; Al-Ansari, M.M.; Silva, G.; Aboussekhra, A. The inflammatory/cancer-related IL-6/STAT3/NF-kappa B positive feedback loop includes AUF1 and maintains the active state of breast myofibroblasts. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41974–41985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; Avruch, J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 807–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C.; Altamirano, F.; Valladares, D.; Lopez, J.R.; Allen, P.D.; Jaimovich, E. Altered ROS production, NF-kappa B activation and interleukin-6 gene expression induced by electrical stimulation in dystrophic mdx skeletal muscle cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollias, G.; Douni, E.; Kassiotis, G.; Kontoyiannis, D. On the role of tumor necrosis factor and receptors in models of multiorgan failure, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol. Rev. 1999, 169, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annibaldi, A.; Meier, P. Checkpoints in TNF-Induced Cell Death: Implications in Inflammation and Cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosz-Griffiths, H.H.; Holbrook, J.; Lara-Reyna, S.; McDermott, M.F. TNF receptor signalling in autoinflammatory diseases. Int. Immunol. 2019, 31, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stone, M.B.; Shelby, S.A.; Veatch, S.L. Super-Resolution Microscopy: Shedding Light on the Cellular Plasma Membrane. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7457–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Balkwill, F.; Chonchol, M.; Cominelli, F.; Donath, M.Y.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Golenbock, D.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Heneka, M.T.; Hoffman, H.M.; et al. A guiding map for inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinelt, N.; Karathanasis, C.; Smith, S.; Medler, J.; Malkusch, S.; Fulda, S.; Wajant, H.; Heilemann, M.; Wijk, S.J.L.V. Quantitative single-molecule imaging of TNFR1 reveals zafirlukast as antagonist of TNFR1 clustering and TNFα-induced NF-ĸB. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 109, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efimov, G.A.; Kruglov, A.A.; Tillib, S.V.; Kuprash, D.V.; Nedospasov, S.A. Tumor Necrosis Factor and the consequences of its ablation in vivo. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni, C.; Braun, J. Side effects of anti-TNF therapy: Current knowledge. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2002, 20, S152–S157. [Google Scholar]

- Medler, J.; Wajant, H. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 (TNFR2): An overview of an emerging drug target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medler, J.; Nelke, J.; Weisenberger, D.; Steinfatt, T.; Rothaug, M.; Berr, S.; Hunig, T.; Beilhack, A.; Wajant, H. TNFRSF receptor-specific antibody fusion proteins with targeting controlled Fc gamma R-independent agonistic activity. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, R.; Kontermann, R.E.; Pfizenmaier, K. Selective Targeting of TNF Receptors as a Novel Therapeutic Approach. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.H.; Schaaf, T.M.; Grant, B.D.; Lim, C.K.W.; Bawaskar, P.; Aldrich, C.C.; Thomas, D.D.; Sachs, J.N. Noncompetitive inhibitors of TNFR1 probe conformational activation states. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12, eaav5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.H.; Vunnam, N.; Lewis, A.K.; Chiu, T.L.; Brummel, B.E.; Schaaf, T.M.; Grant, B.D.; Bawaskar, P.; Thomas, D.D.; Sachs, J.N. An Innovative High-Throughput Screening Approach for Discovery of Small Molecules That Inhibit TNF Receptors. SLAS Discov. 2017, 22, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, Z.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Qiu, L.; Hu, Z.; Ma, X.; Lu, Y. Screening of an anti-inflammatory peptide from Hydrophis cyanocinctus and analysis of its activities and mechanism in DSS-induced acute colitis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, G.S.; Wang, J.J.; Luo, P.F.; Li, A.; Tian, S.; Jiang, H.L.; Zheng, Y.J.; Zhu, F.; Lu, Y.M.; Xia, Z.F. Hydrostatin-SN1, a Sea Snake-Derived Bioactive Peptide, Reduces Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Acute Lung Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xia, J.; Wu, H.; Xiang, Y. Selection of peptide ligands for TNF receptor imaging. Chin. J. Nucl. Med. 2005, 25, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; He, X.; Chen, L.; Guo, W.; Guo, X.; Hao, B.; Li, Y. Pre-clinical study of a TNFR1-targeted F-18 probe for PET imaging of breast cancer. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonbeck, U.; Libby, P. The CD40/CD154 receptor/ligand dyad. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 4–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kooten, C.V.; Banchereau, J. CD40-CD40 ligand: A multifunctional receptor-ligand pair. In Advances in Immunology; Dixon, F.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 61, pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.B.; Foy, T.M.; Noelle, R.J. CD40 and its ligand. In Advances in Immunology; Dixon, F.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 63, pp. 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, D.M.; Sefrin, J.P.; Gieffers, C.; Hill, O.; Merz, C. Concepts for agonistic targeting of CD40 in immuno-oncology. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. Science commentary: Th1 and Th2 responses: What are they? Br. Med. J. 2000, 321, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosmann, T.R.; Cherwinski, H.; Bond, M.W.; Giedlin, M.A.; Coffman, R.L. 2 types of murine helper T-cell clone. I. definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol. 1986, 136, 2348–2357. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, I.; Nalawade, S.; Eagar, T.N.; Forsthuber, T.G. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine 2015, 74, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaffen, S.L. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korn, T.; Bettelli, E.; Oukka, M.; Kuchroo, V.K. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 485–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, K.W.; Park, M.K.; Moon, Y.; Kim, W.U.; Kim, H.Y. IL-17 induces production of IL-6 and IL-8 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts via NF-kappa B- and PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathways. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2004, 6, R120–R128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Onishi, R.M.; Gaffen, S.L. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: Mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunol. 2010, 129, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.H.G. Induction, function and regulation of IL-17-producing T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 2636–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Jiang, C.Y.; Ma, Y.F.; He, H.J.; Wu, Y.; Devriendt, B.; Cox, E.; Zhang, H.B. Toll-like receptor 5-mediated IL-17C expression in intestinal epithelial cells enhances epithelial host defense against F4+ ETEC infection. Vet. Res. 2019, 50, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowley, J.J. Humanized monoclonal antibody demonstrating dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F Treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Drugs Future 2018, 43, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raychaudhuri, S.P.; Raychaudhuri, S.K. Mechanistic rationales for targeting interleukin-17A in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubash, S.; McGonagle, D.; Marzo-Ortega, H. New advances in the understanding and treatment of axial spondyloarthritis: From chance to choice. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2018, 9, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, S.H.; Ye, X.Q.; Iwakura, Y. Interleukin-17 family members in health and disease. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borden, E.C.; Sen, G.C.; Uze, G.; Silverman, R.H.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Foster, G.R.; Stark, G.R. Interferons at age 50: Past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskardin, T.L.W.; Niewold, T.B. Type I interferon in rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazewski, C.; Perez, R.E.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Type I Interferon (IFN)-Regulated Activation of Canonical and Non-Canonical Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niewold, T.B. Interferon Alpha as a Primary Pathogenic Factor in Human Lupus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 31, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marketos, N.; Cinoku, I.; Rapti, A.; Mavragani, C.P. Type I interferon signature in Sjogren’s syndrome: Pathophysiological and clinical implications. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Skaug, B.; Assassi, S. Type I interferon dysregulation in Systemic Sclerosis. Cytokine 2020, 132, 154635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Higgs, B.W.; Rebelatto, M.; Zhu, W.; Greth, W.; Yao, Y.H.; Roskos, L.K.; White, W.I. Suppression of soluble T cell-associated proteins by an anti-interferon-alpha monoclonal antibody in adult patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceuninck, F.D.; Duguet, F.; Aussy, A.; Laigle, L.; Moingeon, P. IFN-a: A key therapeutic target for multiple autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Romero-Perez, D.; Jacobsen, J.A.; Villarreal, F.J.; Cohen, S.M. Zinc-binding groups modulate selective inhibition of MMPs. Chem. Med. Chem. 2008, 3, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, G.; Nagase, H. Progress in matrix metalloproteinase research. Mol. Asp. Med. 2008, 29, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benjamin, M.M.; Khalil, R.A. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as investigative tools in the pathogenesis and management of vascular disease. Exp. Suppl. 2012, 103, 209–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunkelberger, J.R.; Song, W.C. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kemper, C.; Verbsky, J.W.; Price, J.D.; Atkinson, J.P. T-cell stimulation and regulation: With complements from CD46. Immunol. Res. 2005, 32, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.J.; Davenport, A.P. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology CIII: Chemerin Receptors CMKLR1 (Chemerin(1)) and GPR1 (Chemerin(2)) Nomenclature, Pharmacology, and Function. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goralski, K.B.; Jackson, A.E.; McKeown, B.T.; Sinal, C.J. More Than an Adipokine: The Complex Roles of Chemerin Signaling in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garmpis, N.; Damaskos, C.; Garmpi, A.; Nikolettos, K.; Dimitroulis, D.; Diamantis, E.; Farmaki, P.; Patsouras, A.; Voutyritsa, E.; Syllaios, A.; et al. Molecular Classification and Future Therapeutic Challenges of Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Vivo 2020, 34, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erridge, C.; Bennett-Guerrero, E.; Poxton, I.R. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharides. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.E. Fundamentals of endotoxin structure and function. Contrib. Microbiol. 2005, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphinee, S.M.; Karsan, A. Lipopolysaccharide signaling in endothelial cells. Lab. Investig. 2006, 86, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schumann, R.R. Function of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein (LBP) and CD14, the receptor for LPS/LBP complexes—A short review. Res. Immunol. 1992, 143, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qian, G.S.; Li, Q.; Feng, Q.J.; Wu, G.M.; Li, K.L. Screening of mimetic peptides for CD14 binding site with LBP and antiendotoxin activity of mimetic peptide in vivo and in vitro. Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Ando, D.; Kamada, H.; Taki, S.; Niiyama, M.; Mukai, Y.; Tadokoro, T.; Maenaka, K.; Nakayama, T.; Kado, Y.; et al. A trimeric structural fusion of an antagonistic tumor necrosis factor-alpha mutant enhances molecular stability and enables facile modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6438–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kunath, J.; Delaroque, N.; Szardenings, M.; Neundorf, I.; Straub, R.H. Sympathetic nerve repulsion inhibited by designer molecules in vitro and role in experimental arthritis. Life Sci. 2017, 168, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, C.; Neumeier, D.; Reddy, S.T. Integrating high-throughput screening and sequencing for monoclonal antibody discovery and engineering. Immunology 2018, 153, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattabiraman, V.R.; Bode, J.W. Rethinking amide bond synthesis. Nature 2011, 480, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, D.J.; Fairlie, D.P.; Liras, S.; Price, D. The Future of Peptide-based Drugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013, 81, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albericio, F.; Kruger, H.G. Therapeutic peptides foreword. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1527–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sachdeva, S. Peptides as ‘Drugs’: The Journey so Far. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2017, 23, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).