Abstract

The photophysical properties of a BODIPY derivative with the highly twisted molecular structure of anthracene-fused boron–dipyrromethene (AN-BDP) were studied with steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopic methods. The fused anthryl and the BDP units in AN-BDP units both adopt distorted geometry (with ca. 10° of torsion), and there is large dihedral angle between the two units (ca. 49.7°). Interestingly, the fluorescence quantum yields are highly dependent on the solvent polarity (59~3%, from toluene to acetonitrile), yet the fluorescence emission wavelength does not change in different solvents. Nanosecond transient absorption spectra indicate that the triplet state is long-lived, with an intrinsic triplet state lifetime of 551 μs. Interestingly the severely twisted structure only shows a moderate intersystem crossing (ISC) yield (10%). Femtosecond transient absorption spectra indicate slow ISC (>1.5 ns), which is in agreement with the fluorescence lifetime (2.3 ns). Time-resolved electron paramagnetic resonance (TREPR) spectra show smaller zero-field-splitting D and E tensors as (−71.4 mT, 16.7 mT, respectively) compared to the triplet state of the iodinated native BDP (D = −104.6 mT, E = 22.8 mT), inferring that the triplet-state wave function of the new compound is delocalized over the twisted molecular framework. The theoretical computation indicated a solvent-polarity-dependent energy barrier for the relaxed S1 state to a conical interaction (CI) of the S1 and the S0 state potential curves, which agrees with the weaker fluorescence in polar solvents.

1. Introduction

Triplet photosensitizers (PSs) have attracted much attention in recent years, due to the significance of this kind of novel organic molecules in fundamental study of intersystem crossing (ISC) [1,2,3,4,5], as well as their critical roles in applications such as photocatalysis [6,7,8,9], photodynamic therapy (PDT) [10,11,12,13,14], and triplet–triplet–annihilation photon up-conversion [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The ISC ability of triplet PSs is one of the most important properties of these molecules. However, for most of the planar aromatic hydrocarbons, ISC is strongly forbidden because of the large electron exchange energy (J), leading to the large S1/T1 states energy gap, and the weak spin–orbit coupling [22]. Typical methods to enhance the ISC in organic chromophores include using the heavy atom effect (incorporate Pt, Ir, Ru, Br and I atoms in chromophore) [12,13,23,24,25,26], the exciton coupling effect [27,28], establishing n-π *↔ π-π * transitions (El Sayed’s rule for ISC) [29], radical enhanced ISC [30], and charge-recombination-induced ISC [31]. Some drawbacks exist for these conventional methods: for instance, the high cost of precious metal ions, shortened triplet state lifetimes as a result of the heavy atom effect or the radical enhanced ISC, and the difficulties in synthesis [32]. Thus, it is necessary to develop new approaches, based on a simple molecular structure motif, to enhance the ISC in organic chromophores and solve the above problems, which is important for both fundamental photochemistry and for the various applications of these findings.

Concerning this aspect, the twisted π-conjugated framework of a molecular-structure-induced ISC is in particular of interest. Some compounds with twisted molecular structures are known to show efficient ISC: for instance, fullerenes C60/C70 [33] and helicenes [34,35]. However, these compounds alone are not ideal triplet PSs because of their weak absorption of visible light, poor solubility, and challenging derivatization chemistry. Recently, a few other chromophores with twisted geometry showing ISC have been reported: for instance, perylene bisimide (PBI) [36,37,38,39]. Recently, we and Hasobe et al. found that twisted boron–dipyrromethene (BODIPY) also show efficient ISC (Figure 1) [40,41,42]. However, our understanding of the structure–ISC efficiency relationship of these compounds (especially the BODIPY compounds) is far from mature. For instance, we found that the slightly twisted BODIPY derivative show efficient ISC (torsion angle: 7.5°, triplet state quantum yield: 52%) [40], yet some BODIPY derivatives having severely twisted molecular structure show less efficient ISC (torsion angle: ca. 17°, triplet state quantum yield: 16%) [41]. In another twisted BODIPY (helical-BDP-2) with similar torsion angle (ca. 17°), the triplet state quantum yield is as high as 56% [42]. This trend is different from the helicene compounds, for which the more twisted molecular structure usually induces more efficient ISC [34]. Therefore, it is necessary to attain more in-depth understanding of the effect of twisting of the molecular structure on the ISC efficiency with more examples.

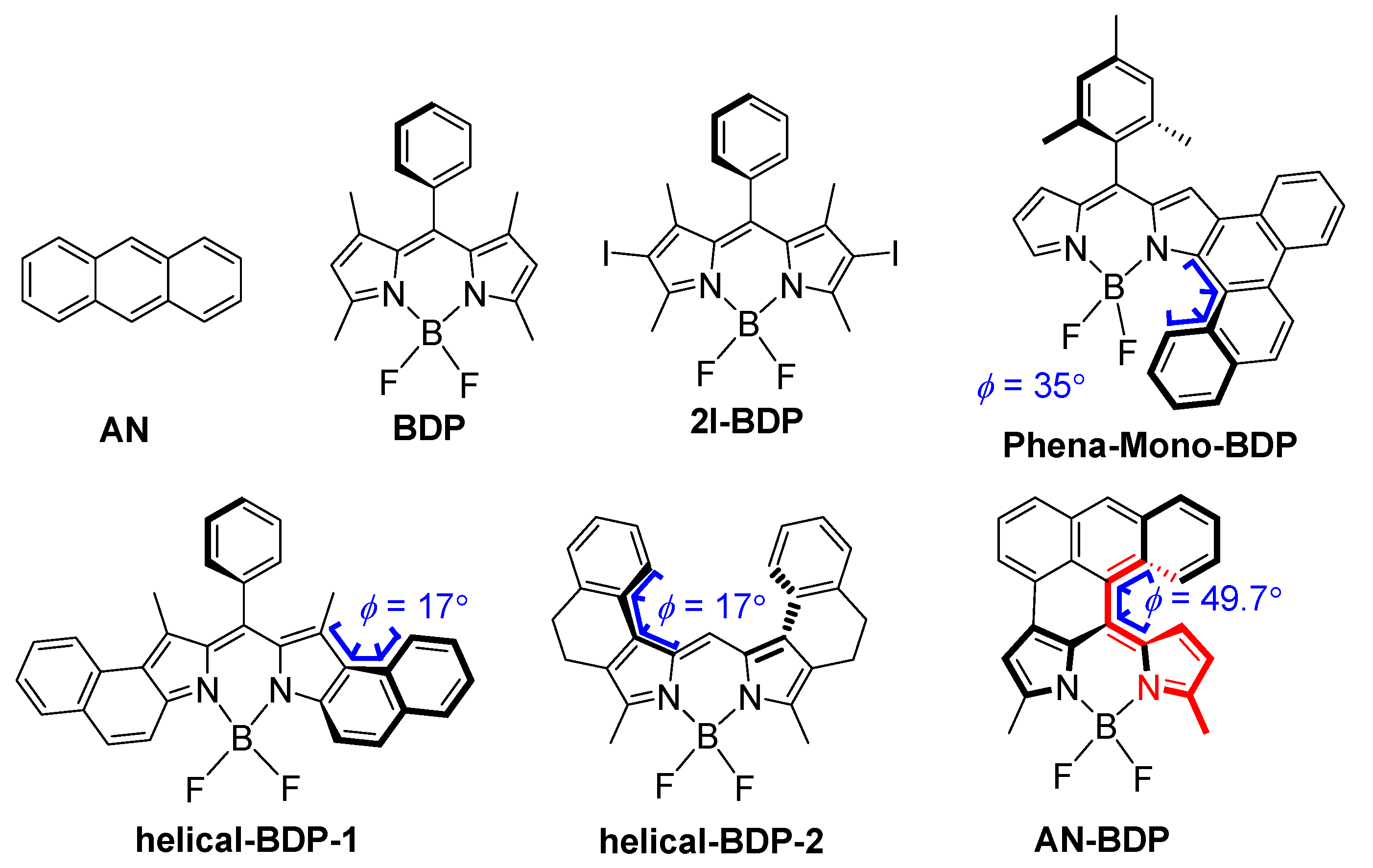

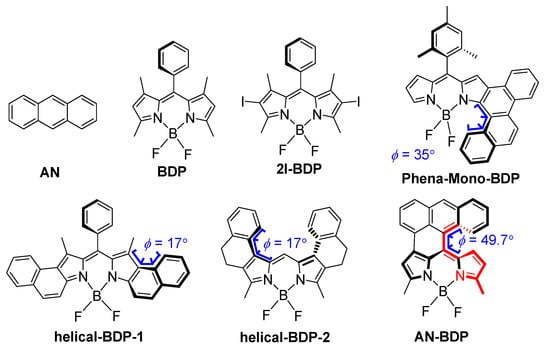

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of the compound AN-BDP, and the recently reported twisted BODIPY derivatives showing ISC (Phena-Mono-BDP, helical-BDP-1 and helical-BDP-2) and reference compounds (AN, BDP and 2I-BDP). The colored part of AN-BDP shows the torsion of the molecule.

Another interesting aspect of the ISC of the twisted BODIPY is the electron spin selectivity, or the population rates of the three sublevels (Tx, Ty, Tz) of the T1 state of the twisted BODIPY derivatives; this is one of the fundamental photophysics principles of ISC [43,44,45,46]. However, it is not possible to study this property with normal optical spectral methods. Recently, we studied the triplet state of twisted BODIPY derivatives and their electron spin polarization (ESP) with time-resolved electron paramagnetic resonance (TREPR) spectroscopy, and we found that the electron spin selectivity of the ISC of the twisted BODIPY chromophore is highly dependent on the molecular structure [40,42]. However, more examples are needed to fully unveil the electron spin selectivity of the ISC of the compounds with a twisted molecular structure.

In order to study the relationship of twisting ISC efficiency, herein, we studied an anthracene-fused BODIPY derivative (AN-BDP, Figure 1) [47]. Both the partially fused anthryl moiety and the BODIPY moiety are highly distorted, and the torsion between the two moieties is large (49.7°, see later sections for detail). The photophysical properties of the compound were studied with steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopic methods; ISC and long-lived triplet state were observed. The TREPR spectra show the electron spin selectivity of the ISC in the twisted BODIPY derivative.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Structure of the Twisted BODIPY

Native BODIPY has a planar molecular structure, which makes the electron exchange energy (J) large; thus, the large S1/T1 energy gap inhibits ISC. Inspired by the twisted π conjugation-framework-induced ISC in helicene [34,35], PBI [36,38,39], and the recently reported twisted BODIPY derivatives (helical-BDP-1 [40], helical-BDP-2 [42] and Phena-Mono-BDP (ΦΔ = 63% in DCM) [41]), herein, we studied another BODIPY derivative which has highly twisted molecular structure, AN-BDP [47]. This compound was reported previously, but no detailed studies on its geometry or ISC were presented [47]. The difference between AN-BDP and Phena-Mono-BDP is that the BODIPY core in the former is severely distorted (see later section); it is almost planar for the latter [41]. This different geometry for the BODIPY core may have significant impacts for the photophysical properties: for instance, the non-radiative decay of the S1 state to the ground state [48]. Moreover, the fluorescence quantum yield and the ISC quantum yield may be also affected.

2.2. UV–Vis Absorption and Fluorescence Spectra

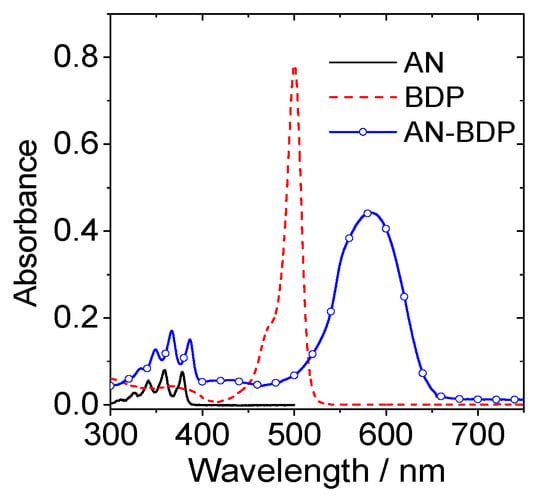

The UV–vis absorption band of AN-BDP is centered at 583 nm, which is broad and structureless (Figure 2). These features are different from the absorption of native BODIPY [49,50,51], as well as the compact dyad with anthryl moiety attached at the meso-position of BODIPY [52,53]. These results indicate that π-conjugation framework of AN-BDP is different from the native BODIPY. The UV–vis absorption of AN-BDP is also different from the fully fused anthryl-BDP analogues (which is with planar π-conjugation framework), which show red and near IR absorption bands centered at 606 nm (ε = 7200 M−1 cm−1), 650 nm (ε = 11,300 M−1 cm−1), 760 nm (ε = 5600 M−1 cm−1), and 826 nm (ε = 5700 M−1 cm−1) [54].

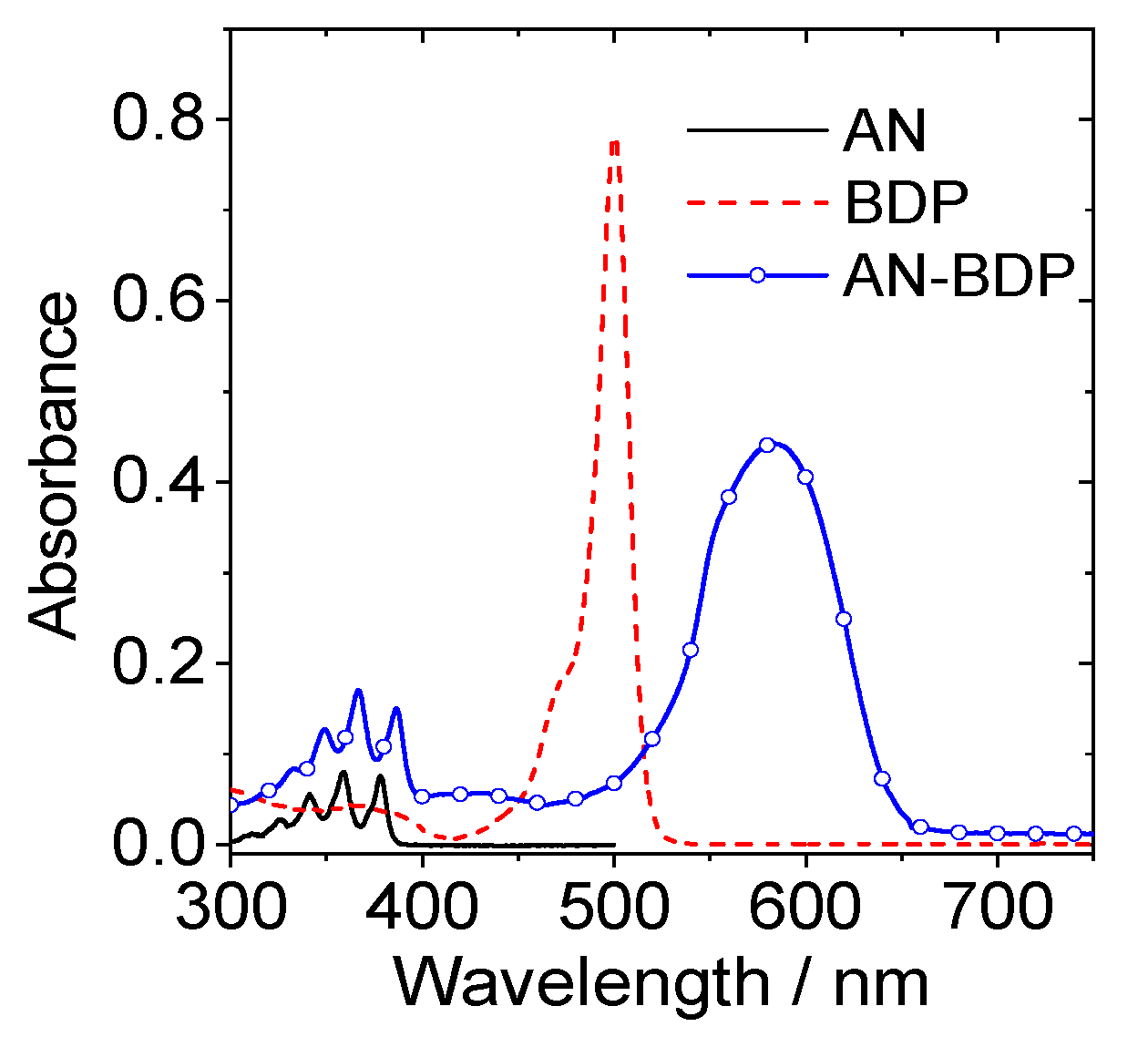

Figure 2.

UV–vis absorption spectra of AN, BDP and AN-BDP in DCM, c = 1.0 × 10−5 M, 20 °C.

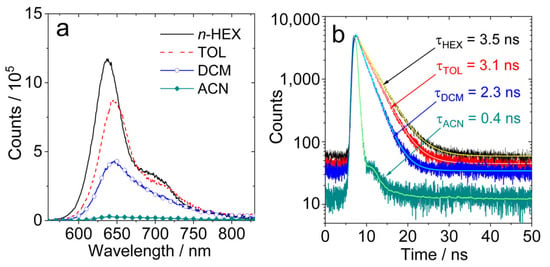

The fluorescence band of AN-BDP is centered at 645 nm, which is red-shifted more when compared with the fluorescence of native BODIPY (ca. 500 nm) [55]. Interestingly, the fluorescence intensity is reduced in polar solvents, but the fluorescence emission wavelength is not red-shifted (Figure 3). This is unusual, and it indicates that the quenching of the fluorescence in polar solvent is not due to the energy gap law. We propose that there is a non-radiative relaxation channel for AN-BDP, which is more efficient in polar solvents. This postulate is confirmed by the theoretical studies (see later section, the theoretical calculation shows that the energy barrier for non-radiative decay of the S1 state becomes smaller in polar solvents). The fluorescence behavior of AN-BDP is also different from the previously reported anthryl-BODIPY dyads, for which charge transfer (CT) emission band was observed (ca. 650 nm), as well as the LE emission (ca. 515 nm) [47,52,53].

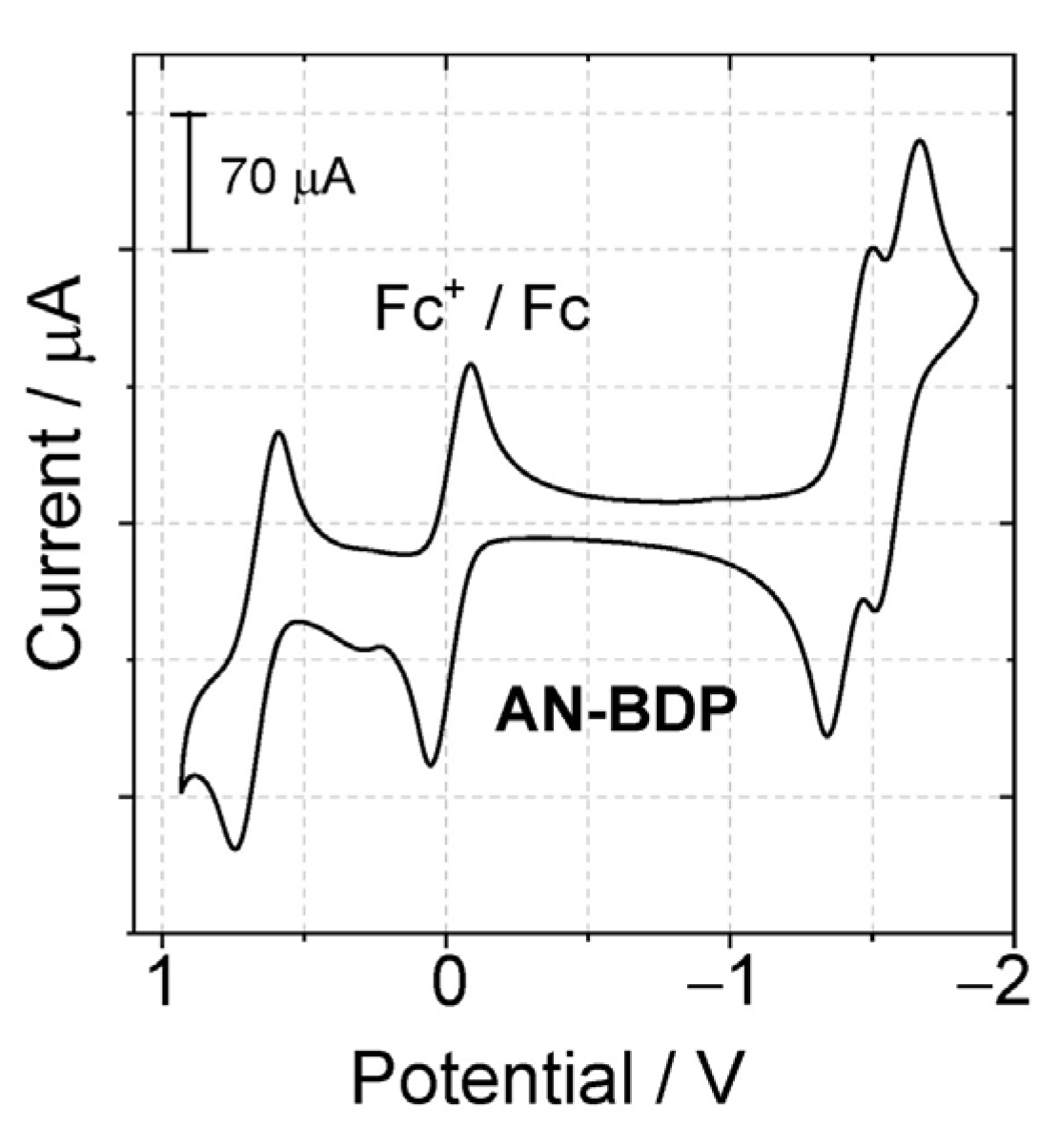

Figure 3.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of AN-BDP in different solvents. Optically matched solutions were used, λex = 550 nm, A550nm = 0.22; (b) fluorescence decay traces of AN-BDP in different solvents. c = 1.0 × 10−5 M, λex = 510 nm, 20 °C.

The fluorescence lifetimes of AN-BDP in different solvents were studied with the time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) technique (Figure 3b). From non-polar solvents to polar solvents, the fluorescence lifetimes are shortened gradually. For instance, the fluorescence lifetime in HEX is 3.5 ns, whereas it is 3.1 ns, 2.3 ns and 0.4 ns in TOL, DCM and ACN, respectively. This result indicates that a non-radiative decay channel is more efficient in polar solvents. Based on the fluorescence quantum yields and the fluorescence lifetimes (Table 1), the radiative decay rate constants (kr) and the non-radiative decay rate constants (knr) in different solvents were calculated; the results show that knr is strongly influenced by the solvent. For helical-BDP-2, the fluorescence quantum yields are solvent-independent, and the fluorescence lifetimes are solvent-polarity-independent (3.6~4.7 ns) [42]. For the Phena-Mono-BDP, the fluorescence quantum yields are almost solvent-polarity-independent (13~22% in most solvent, 4% in DCM), and the fluorescence lifetimes are in the range of 2.48~3.53 ns [41]. Thus, the solvent-polarity-dependent fluorescence quantum yield and lifetimes of AN-BDP are unique in these twisted BODIPY derivatives. Moreover, we noted that the non-radiative relaxation of the S1 state of AN-BDP to the ground state is significant (i.e., the sum of the fluorescence quantum yield and the ISC quantum yield of AN-BDP in a specific solvent is much less than unity), which is different from Phena-Mono-BDP [41], helical-BDP-1 and helical-BDP-2 [40,41,42]. The efficient non-radiative decay of the S1 state of AN-BDP may be due to the puckered geometry of the BODIPY core [48,56], which is different from the planar BODIPY core in Phena-Mono-BDP [41]; for both the helical-BDP-1 and helical-BDP-2, the BODIPY core adopts an almost planar geometry [40,42].

Table 1.

The photophysical properties of AN-BDP.

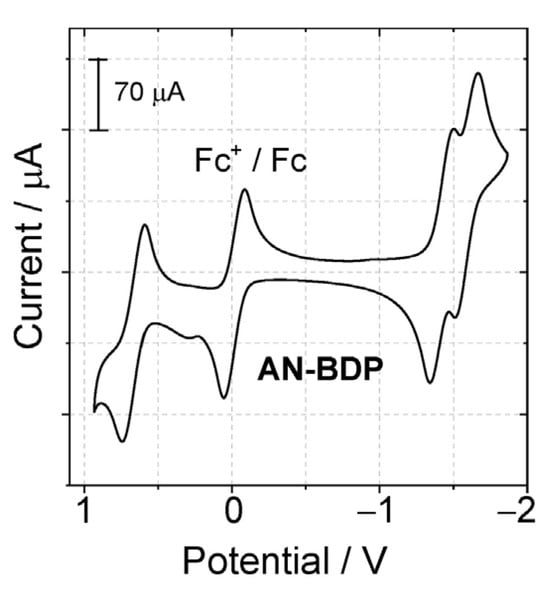

2.3. Electrochemistry Study

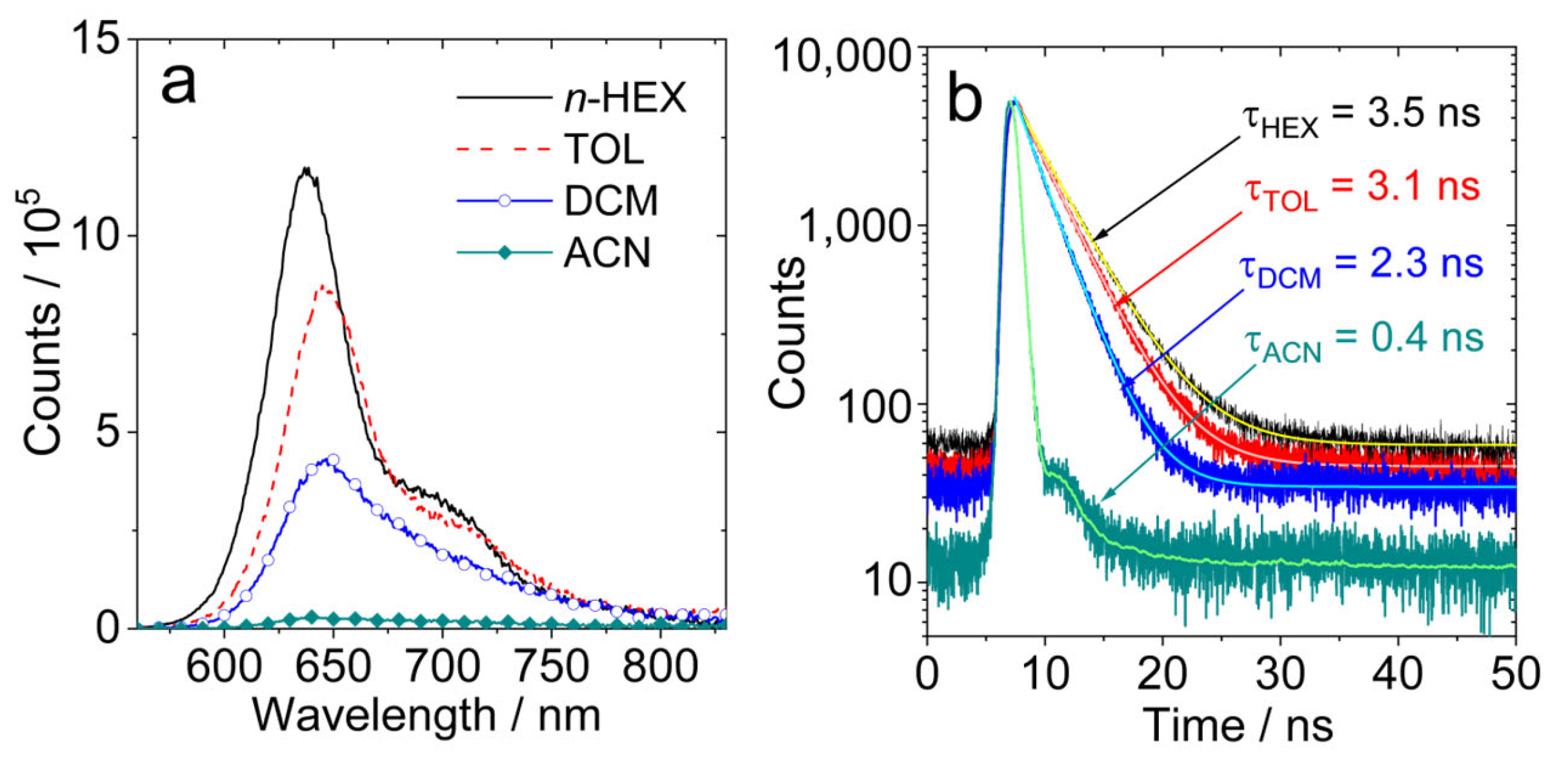

The redox potentials of the dyads were measured with cyclic voltammetry (Figure 4). For AN-BDP, a reversible oxidation wave was observed at +0.65 V (vs. Fc/Fc+), two reversible reduction waves, at −1.40 V and −1.61 V (vs. Fc/Fc+) were observed. According to the molecular orbital analysis, the HOMO is mainly confined on the BODIPY part, and the LUMO is mainly confined to the anthryl part. However, it should be noted that the separation of the HOMO and LUMO is not distinct, i.e., the π-conjugation between the BODIPY part and the anthryl part is significant. The HOMO and LUMO energy levels are influenced by the torsion of the π-conjugation framework. This effect may further lead to the change of the energy levels of the S1 state and the Tn states, as well as their energy matching, which eventually may lead to variation of the ISC ability of the chromophores having a twisted π-conjugation framework.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms determined for AN-BDP in deaerated DCM containing 0.10 M Bu4N[PF6] as supporting electrolyte and with Ag/AgNO3 as reference electrode. Scan rate: 100 mV/s. Ferrocene (Fc) was used as internal reference (set as 0 V in the cyclic voltammograms), c = 1.0 × 10−3 M, 25 °C.

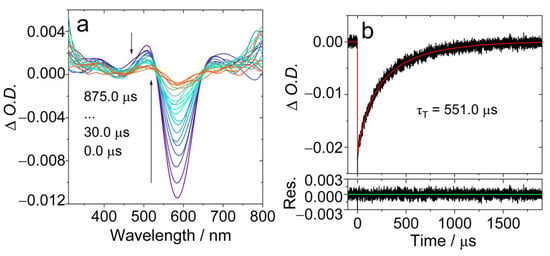

2.4. Nanosecond Transient Absorption (ns-TA) Spectra

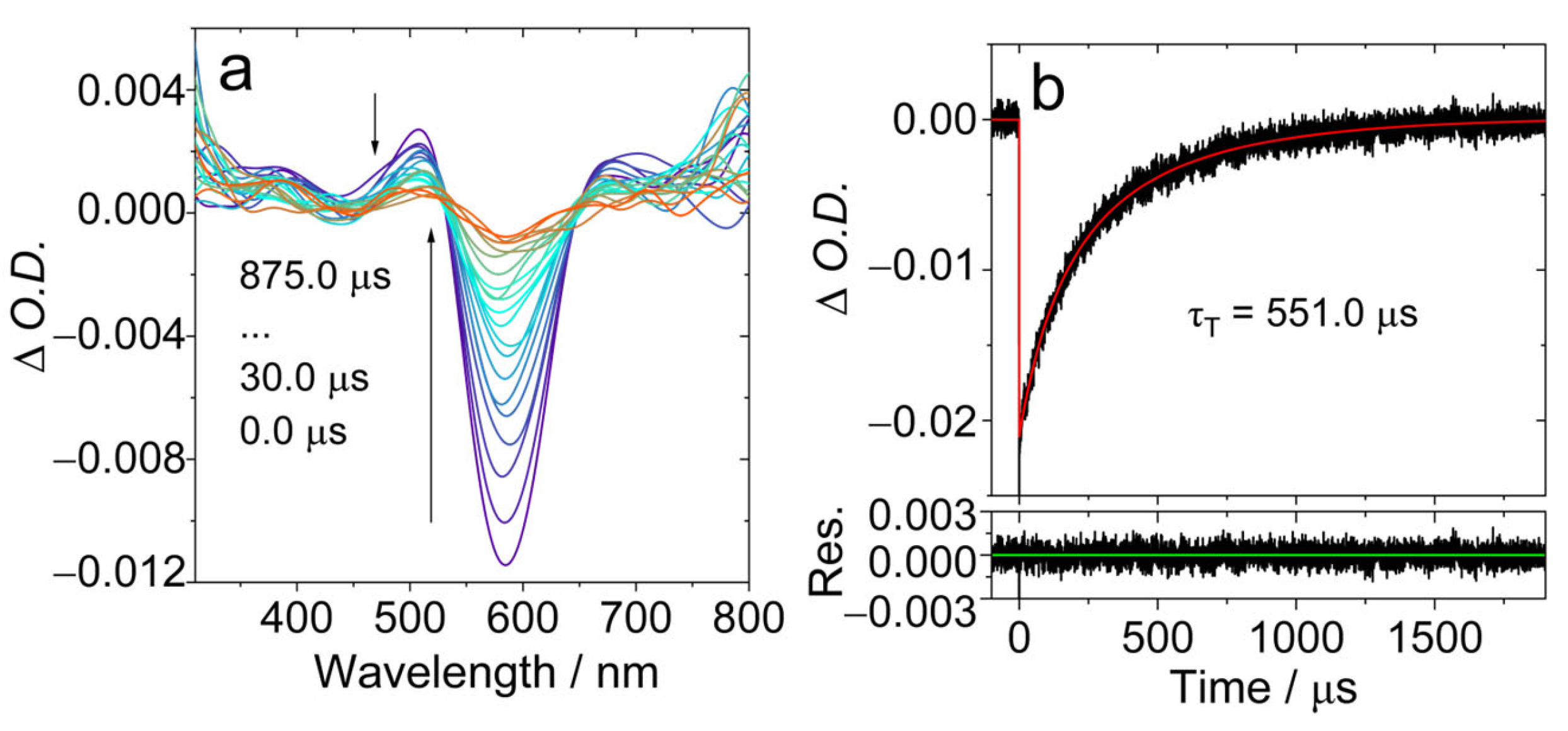

The ns-TA spectra of AN-BDP were studied (Figure 5). Upon pulsed laser excitation, a ground-state bleaching (GSB) band centered at 586 nm was observed, together with the weak excited state absorption (ESA) bands centered at 506 nm and 680 nm, respectively (Figure 5a). This profile may be due to the superposition of the GSB and the ESA bands, i.e., there is probably a broad ESA band in the range of 450 nm–700 nm. The ESA bands are similar to that of the native BDP [26]. The intrinsic triplet state lifetime was determined as 551.0 μs, based on a kinetics model with the TTA self-quenching effect considered in [53,55]. This lifetime is much longer than that of the triplet state of the native BDP (ca. 82 μs) [53] and helical-BDP-2 (197.5 μs) [57], but it is comparable to the recently reported twisted BODIPY (helical-BDP-1, 492 μs) [40].

Figure 5.

Nanosecond transient absorption spectra of AN-BDP in deaerated DCM. (a) Transient absorption spectra and (b) decay trace at 585 nm. λex = 580 nm, c = 3.0 × 10−5 M, 20 °C. The τT is the intrinsic lifetime obtained by fitting τT in two different concentrations. The arrows in (a) indicate the evolution of the spectrum along with increasing of the delay time after laser flash.

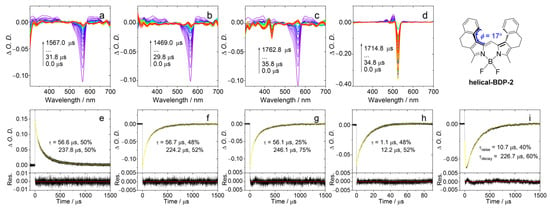

The T1 state energy of AN-BDP was calculated as 1.02 eV with time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) method. In comparison, the T1 state energy of Phena-Mono-BDP was determined as 1.42 eV (phosphorescence method) and the S1 state energy is 1.99 eV [41]. The T1 state energy of helical-BDP-2 is 1.60 eV (TDDFT computation) [42], which is in good agreement with the triplet–triplet energy transfer (TTET) experimental results (1.2–1.7 eV, Figure 6).

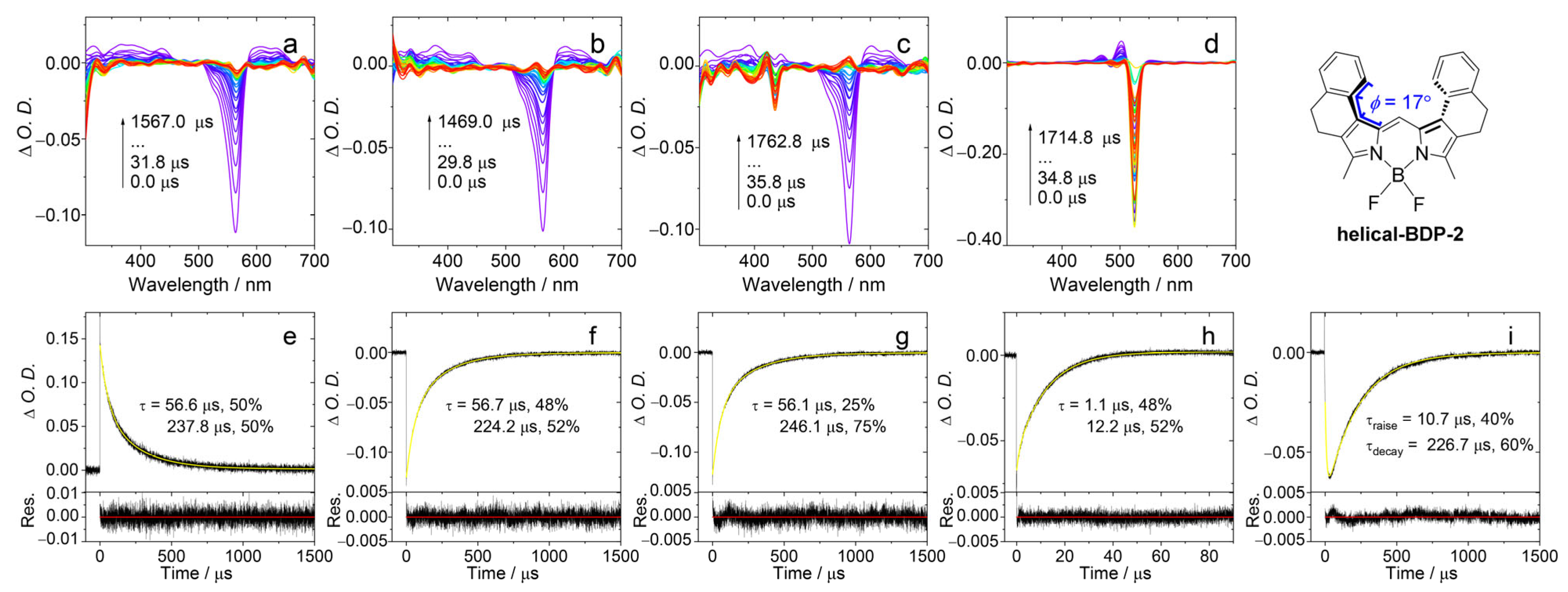

Figure 6.

Nanosecond transient absorption spectra and decay traces in deaerated DCM. (a) Spectrum of helical-BDP-2 alone. (b–d) Spectra of helical-BDP-2 (triplet donor) in the presence of the triplet acceptors 9,10-Diphenylanthracene, Perylene, and PBI, respectively. (e–h) Corresponding decay traces monitored at 560 nm for conditions (a) to (d), respectively. (i) Decay trace at 505 nm for helical-BDP-2 with PBI. λex = 550 nm, c[donor] = 5.0 × 10−6 M, c[acceptor] = 2.0 × 10−5 M, 20 °C. The arrows in (a–d) indicate the evolution of the spectrum along with increasing of the delay time after laser flash.

We used TTET experiment to estimate the T1 state energy level of helical-BDP-2. In this experiment, helical-BDP-2 is used as the energy donor, while three different compounds (9,10-Diphenylanthracene, perylene, and PBI) were used as energy acceptors. After selectively exciting helical-BDP-2 at 550 nm, we measured the quenching of its triplet state lifetime to determine the range of its T1 energy, as shown in Figure 6. The T1 state energies of the acceptors were calculated as follows: 9,10-Diphenylanthracene, 1.77 eV; perylene, 1.53 eV; and PBI, 1.24 eV. After selectively exciting helical-BDP-2 at 550 nm, the ns-TA spectrum showed a GSB band centered at 560 nm (Figure 6a). When 9,10-Diphenylanthracene was introduced, the decay lifetime at 560 nm (Figure 6f) remained essentially the same as without any acceptor (Figure 6e). No characteristic triplet state absorption of 9,10-diphenylanthracene was detected. This indicates that the T1 state energy level of 9,10-Diphenylanthracene is much higher than that of helical-BDP-2. Note upward energy transfer is thermodynamically forbidden. Upon addition of perylene, a GSB signal of perylene at 435 nm can be observed in the spectrum (Figure 6c). However, the decay lifetime monitored at 560 nm shows almost no change (Figure 6g). This suggests that the T1 state energy levels of helical-BDP-2 and perylene are relatively close. Furthermore, the presence of PBI caused the GSB band centered at 560 nm to disappear rapidly, while a new GSB band centered at 525 nm emerged, attributed to the GSB band of PBI (Figure 6d). This new signal exhibits a distinct rise-and-decay biphasic feature, corresponding to the generation and subsequent decay of the PBI triplet state, confirming the occurrence of highly efficient energy transfer. Since the T1 state energy level of PBI (1.24 eV) is lower than that of helical-BDP-2, while 9,10-diphenylanthracene caused no effective quenching, the experimental results indicate that the T1 state energy level of helical-BDP-2 falls within the range of 1.24–1.77 eV, likely around 1.5 eV.

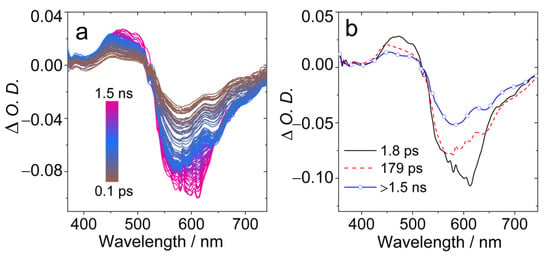

2.5. Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectra

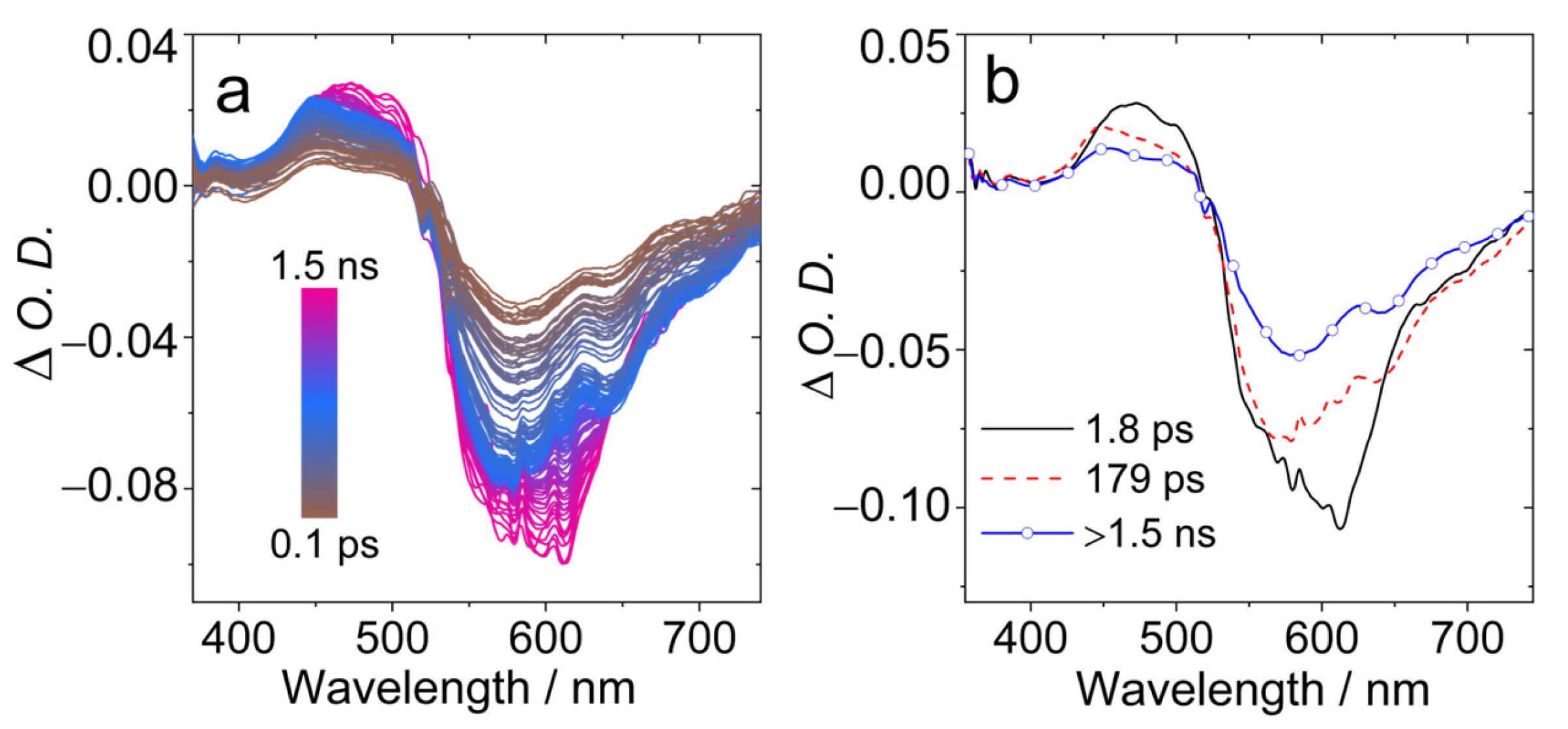

In order to study the excited states dynamics, the femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectra of AN-BDP were studied (Figure 7). A broad GSB band centered at ca. 600 nm was observed (Figure 7a), as well as ESA band in the range of 450–520 nm. With global fitting and target analysis, the evolution-associated difference spectra (EADS) were obtained (Figure 7b). The first spectrum has a shoulder negative band at 610 nm, which is assigned to stimulated emission (SE) band; this spectrum is attributed to the Franck–Condon (FC) singlet excited state (S1 state). Then within 1.8 ps, the spectrum evolved into the second one, this time is attributed to the vibronic relaxation process. The second spectrum is without significant SE band. Within 179 ps (possibly due to geometry relaxation and solvation changes), the third spectrum was the result, with decays over 1.5 ns. We assign the third spectrum to the relaxed emissive S1 state, for which the lifetime is in good agreement with the fluorescence lifetime of AN-BDP in DCM (2.3 ns. Figure 3b). No significant formation of the triplet state was observed within the time window of the fs-TA spectrometer (1.5 ns). This is probably due to the slow ISC and low ISC yield of AN-BDP (ΦΔ = 10%). Previously, a slow ISC was observed for helical-BDP-1 (ca. 8 ns) [40]; for helical-BDP-2, the ISC was determined as 2.57 ns [42].

Figure 7.

Femtosecond transient absorption spectra of AN-BDP. (a) Transient absorption spectra at different delay times and (b) evolution-associated difference spectra (EADS). EADS were obtained by singular value decomposition (SVD) and global fitting. λex = 560 nm, c = 1.0 × 10−5 M in DCM, 20 °C.

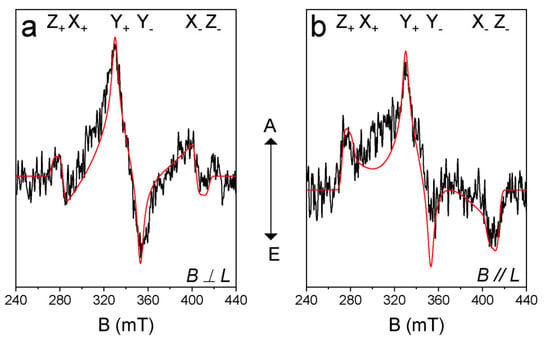

2.6. Time-Resolved Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (TREPR) Spectra

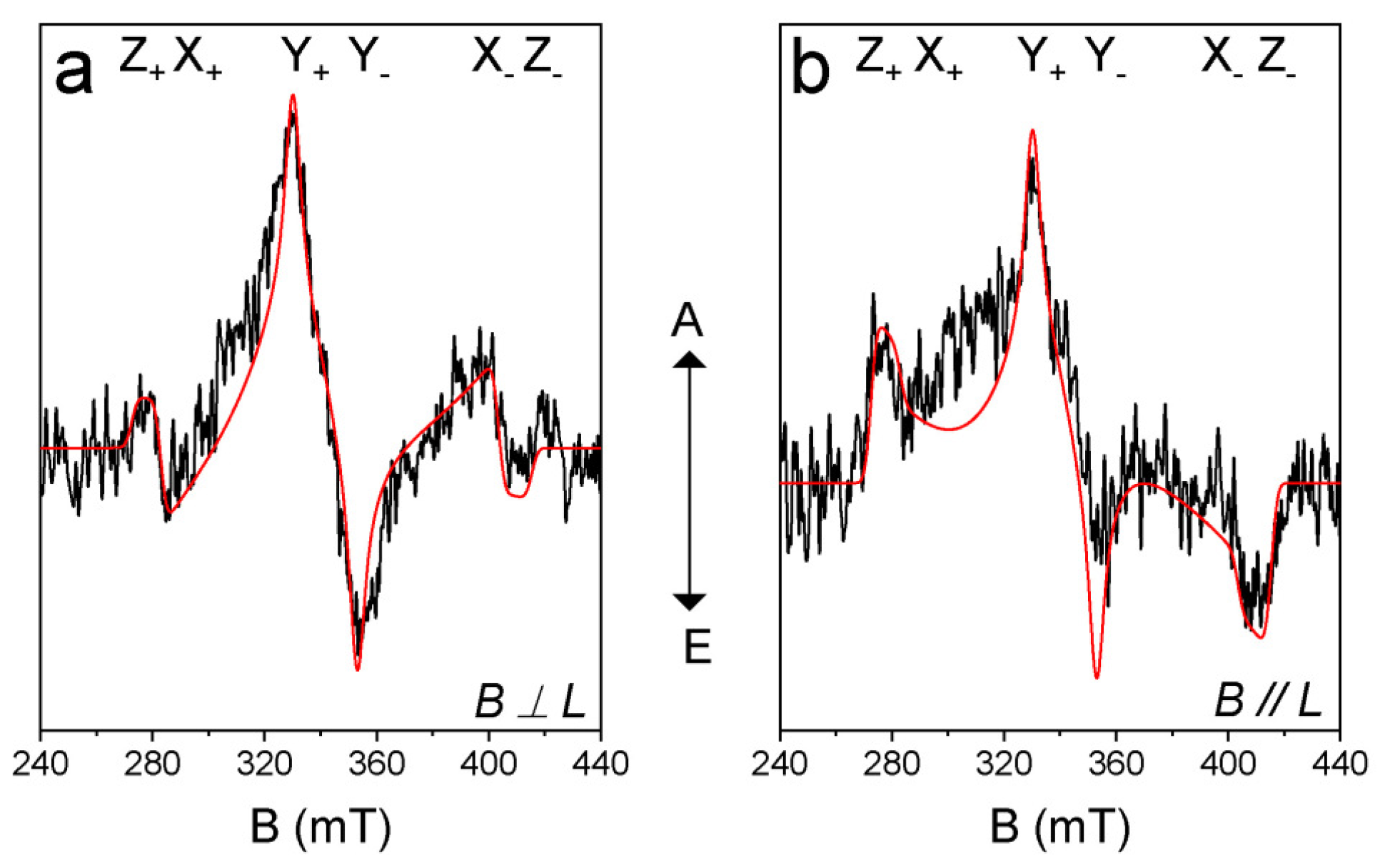

In order to study the electron spin selectivity and the spatial confinement of the triplet-state wave function [43,45,46,58], the TREPR spectrum of AN-BDP was recorded (Figure 8). The ESP phase pattern of the triplet TREPR spectrum of AN-BDP is (a, e, a, e, a, e); this is different from the ordinary ESP phase pattern of the triplet states of anthracene (e, e, e, a, a, a) and 2I-BDP (e, e, e, a, a, a) [53] produced by the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) ISC effect. The spin–orbit charge transfer (SOCT) ISC produces a triplet state showing different ESP as compared to that of SOC. The ESP of AN-BDP is same to that of helical-BDP-1 [40], but it is different from that of helical-BDP-2, which shows ESP of (a, a, e, a, e, e) [42]. These results indicate the sensitivity of the ESP to the structure of the twisted BDP derivatives.

Figure 8.

TREPR spectra of AN-BDP. The simulations (red lines) and experimental data (black lines) are shown. The polarization of laser and magnetic field is (a) perpendicular and (b) parallel. Spectra were recorded by excitation of the frozen solution with 580 nm nanosecond-pulsed laser. In TOL/MeTHF (3:1, v/v). 80 K. Integration time window: 0.0~0.4 μs.

Simulation of the TREPR spectrum of AN-BDP gives the zero-field-splitting (ZFS) D and E tensors, as well as the population rates of the three sublevels of the triplet state [45,46]. We performed the magneto photoselection (MPS) experiment which allows the determination of the relative orientation of the transition dipole moment (TDM) and ZFS axes. The D and E values of AN-BDP are −71.4 mT and 16.2 mT, respectively (Table 2). The orientation of the TDM (θ, φ) was (30°, 90°), where θ and φ are the polar and azimuthal angles between ZFS tensor and TDM, respectively. From the ZFS parameter D and E values, we concluded that the electron spin density is delocalized on the twisted π-conjugation framework of AN-BDP. This is because the magnitude of the D and E parameters of the triplet state of 2,6-diiodoBODIPY (2I-BDP) are −105.0 mT and 23.2 mT, respectively [53], which are larger than that of AN-BDP. The magnitude of the D parameter is dependent on the dipolar interaction of the electrons (spin–spin coupling, SSC), which is related to the average distance between the two electrons. Spin–orbit coupling (SOC) also contribute to the ZFS D. For a non-fused anthracene-BODIPY dyad, the triplet state localized on the BODIPY unit show D and E parameters of −85.0 mT and 17.5 mT, respectively [53]. We recently reported a twisted BODIPY derivative with larger π-conjugation framework, which shows D and E parameters of −59.5 mT and 11.0 mT, respectively [40]. These results show that the triplet state of a molecule with larger π-conjugation system gives smaller ZFS D value. Interestingly, the D and E parameters of the triplet state of AN-BDP are similar to a recently reported twisted BODIPY derivative, with two peripheral phenyl rings, for which the D and E parameters are −69.5 mT and 15.5 mT, respectively [42]. The population rates of the three sublevels of the T1 state of AN-BDP are Px: Py: Pz = 0: 1: 0 (Table 2), which are different from the previously reported twisted BDP derivatives [40,42]. Also, the TDM orientation of AN-BDP is not coincide with TDM orientation of 2,6-diiodoBODIPY [59].

Table 2.

ZFS parameters (D and E) and relative population rates Px,y,z of the zero-field spin states of compounds. The compounds used in the study as reference are also presented.

2.7. Theoretical Computation: The Non-Radiative Decay Channel and the ISC of AN-BDP

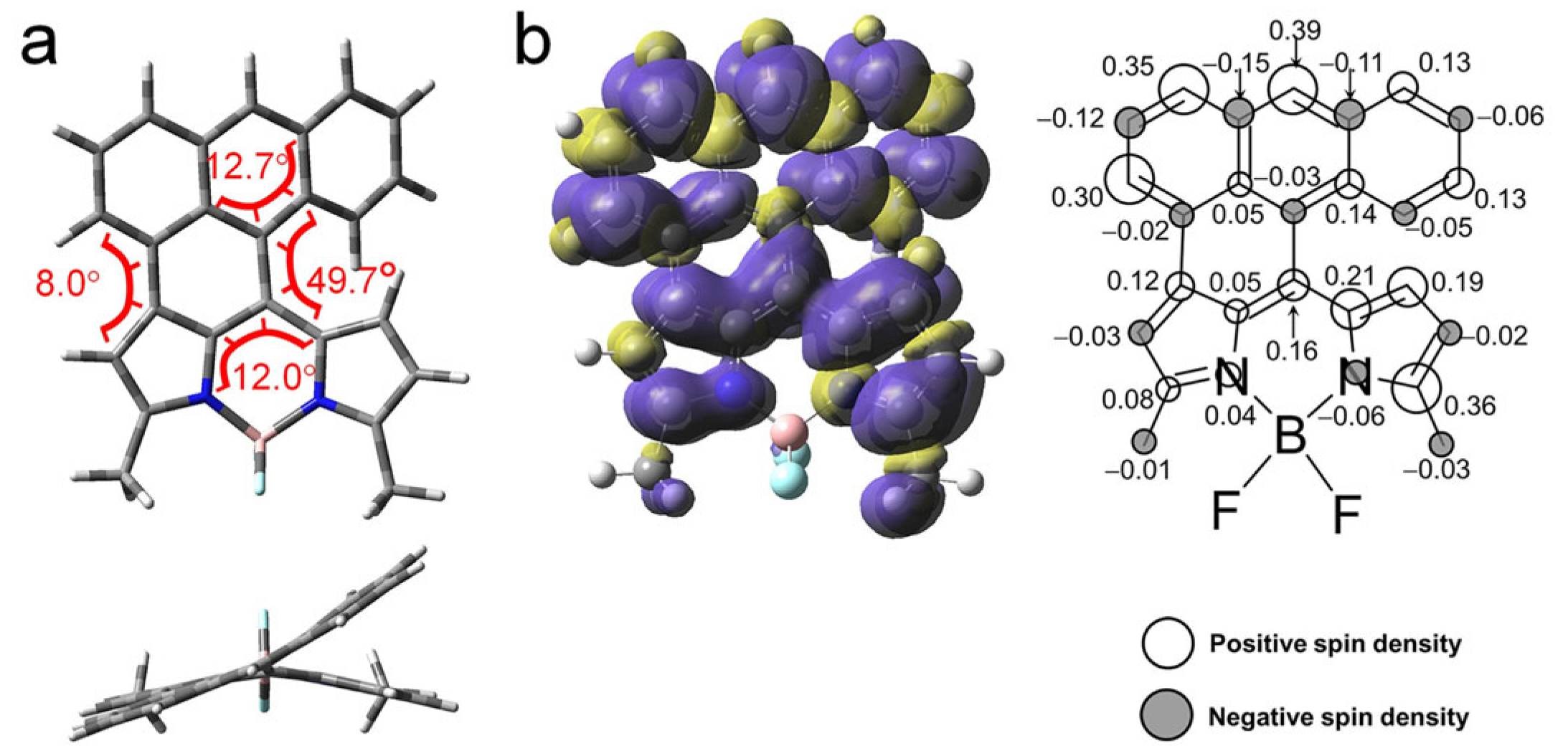

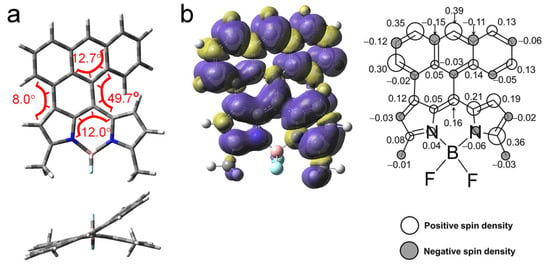

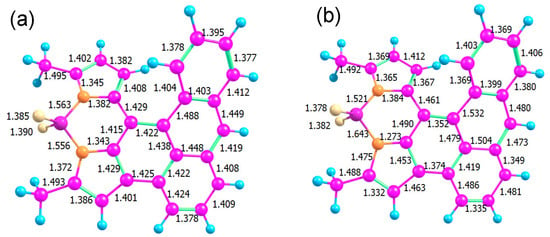

The geometry and the photophysical property of AN-BDP were studied in detail with theoretical computation. The optimized ground state geometry indicated a highly twisted molecular structure (Figure 9a). Both the fused anthryl and the BDP units are non-planar. The anthryl unit is twisted by 12.7°, whereas the puckered BDP unit is with torsion of 12°. The dihedral angle between the two units is 49.7°, whereas it is 8.0° on the other side of the fused structure (Figure 9a). These geometry detail was not reported in the previous literature [47], and it is drastically different from the analogue that the anthryl unit is fully fused with the BDP unit, the fully fused analogue takes a planar geometry [54]. The conformation of AN-BDP is also different from the recently reported anthryl-BODIPY dyads in which the two units are connected by one single C-C band [52,53,60].

Figure 9.

(a) Optimized conformations and the dihedral angles of AN-BDP. Top, side view; bottom, top view. DFT computation is at UB3LYP/6-31G(d) level with Gaussian 16. (b) Isosurfaces of spin density of AN-BDP at the optimized triplet state geometries (Isovalue = 0.0004). The color part in (a) highlight the torsion of the molecular structure. Calculation was performed at UB3LYP/6-31G(d) level with Gaussian 16. The numbers in the figure indicate the contribution of each atom to the total spin density.

The spin density surface of the T1 state of the AN-BDP was computed (Figure 9b); the results show that the spin density is fully delocalized on the whole molecular structure, and the distribution on the fused anthryl moiety is significant. This result is in agreement with the smaller ZFS D parameter of AN-BDP as compared to that of the 2I-BDP. Note the spin density distribution of AN-BDP is also slightly different from that of the helical-BDP-1, for which the spin density is mainly confined on the core of the BDP, and the distribution on the peripheral fused phenyl rings are limited [40]. The triplet state spin density distribution is drastically different from the compact orthogonal anthryl-BDP dyads with C-C as linker between the two parts, for which the spin density of the T1 state is exclusively confined on the BDP unit [53]. The T1 state energy was estimated to be 0.96 eV with TDDFT computation. It is significantly lower than the native BDP (ca. 1.6 eV) and helical-BDP-2 (ca. 1.5 eV) [42].

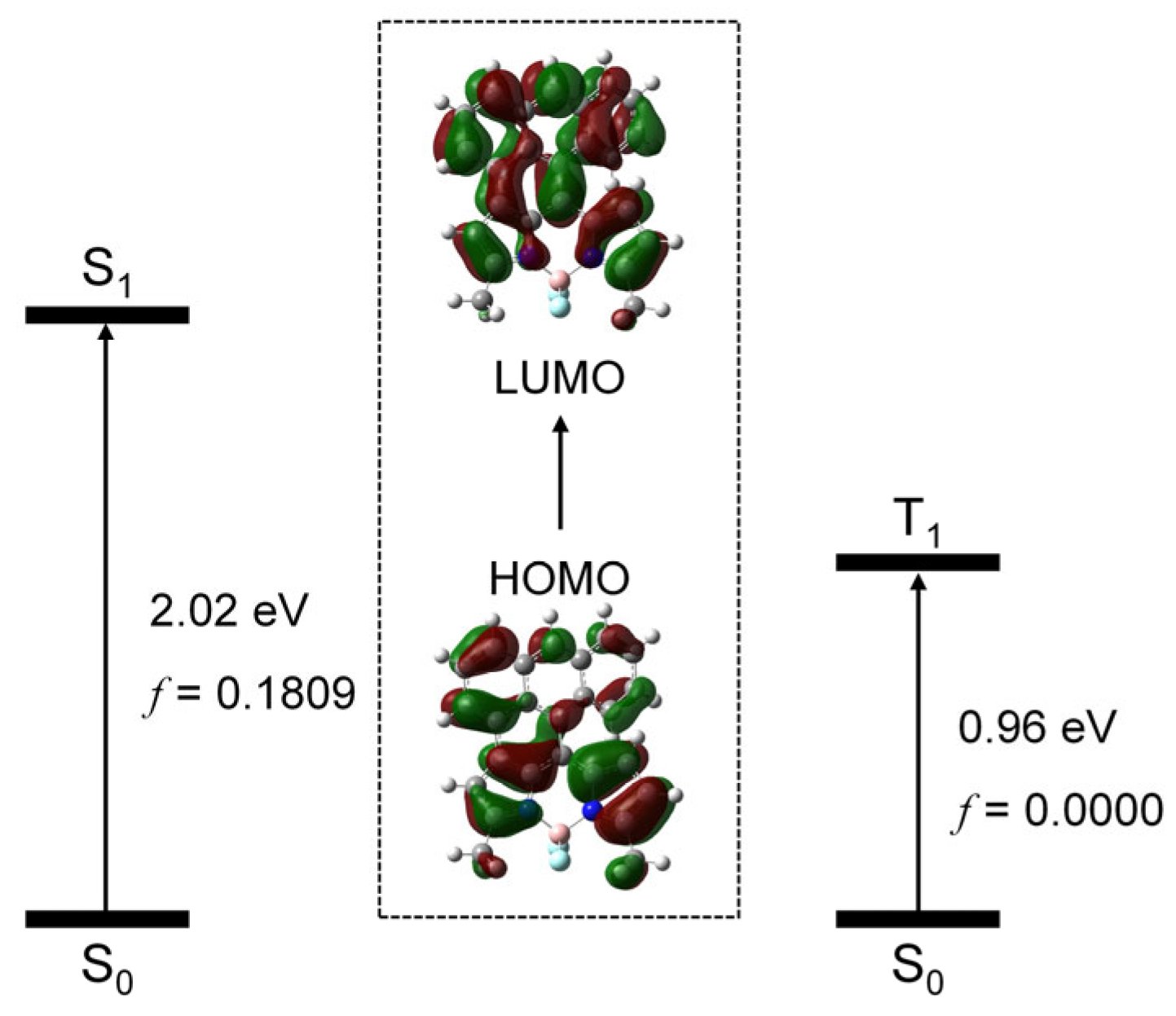

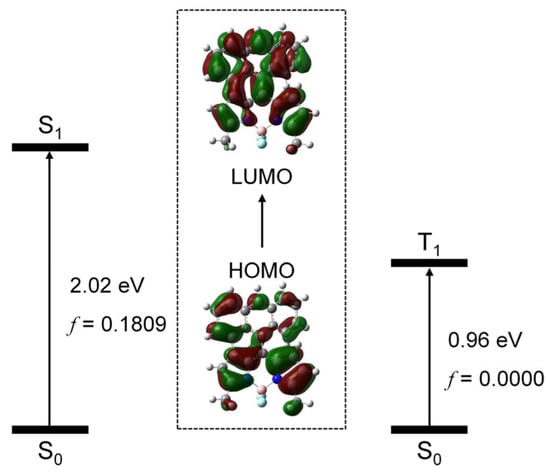

We studied the frontier molecular orbitals involved in the transition from ground state (S0) to the low-lying electronic excited states (S1 and T1 states), using the TDDFT method. We found that, for the S0 → S1 transition, the HOMO and LUMO are involved, and the excitation energy is 2.02 eV, in good agreement with the experimental results (2.14 eV). For the S0 → T1 transition, the HOMO and LUMO are involved and the excitation energy is 0.96 eV. The HOMO and LUMO are mainly delocalized on the whole molecular structure (Figure 10). Note that, for the transition, no SOC effect was considered; therefore, the oscillator strength for the transition is null.

Figure 10.

Molecular orbitals involved in the transition from the ground state (S0) to the low-lying excited states (S1 and T1 states). TDDFT computation was performed at B3LYP/6-31G(d) level with Gaussian 16.

Using the TDDFT method and the EPR/NMR module of ORCA 6.0 program [61], we carried out a preliminary study of the ISC ability and the triplet state property (mainly the ZFS). Firstly, we checked the spin–orbit coupling matrix elements (SOCMEs) of the S1 state to the triplet states, we found that for the S1 → Tn (n = 1–4), the SOCMEs are negligible (less than 0.5 cm−1), indicating that the ISC should be weak for AN-BDP. This is in agreement with the experimental results. In order to verify this approach, we also investigate the BODIPY with the same method, which is known for lack of ISC ability [26]. Small SOCMEs with similar magnitude were observed. On the other hand, for the 2I-BDP, which is known showing efficiency ISC [26], larger SOCMEs were observed: for instance, the SOCMEs are 1.14 cm−1, 1.29 cm−1, and 460 cm−1 for the ISC of S1 → T3, S1 → T4, and S1 → T5, respectively.

Moreover, the ZFS of the triplet state of AN-BDP was calculated with the EPR/NMR module of ORCA 6.0 program. For AN-BDP, the calculated ZFS D is −15.9 mT, which is on the same order of magnitude of the experimental value of −71.7 mT. The contribution of spin–spin coupling (SSC) to the ZFS D tensor of AN-BDP is −23.5 mT, and the contribution of the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) to the ZFS D tensor is 7.6 mT. On the other hand, we studied 2I-BDP (which is known to have an efficient ISC) with a similar method for comparison. The calculated ZFS D is −98.4 mT, which is in good agreement with the TREPR experimental results (−105.7 mT) [53]. In this case, the contribution of SSC to the ZFS D tensor is −2.1 mT, and the contribution of SOC to the ZFS D tensor is −96.1 mT; this is reasonable because the SOC is strong for 2I-BDP, due to the heavy atom effect of the iodine atoms in the molecular structure. Furthermore, for the unsubstituted BODIPY, the calculated ZFS D is −66.3 mT; again, it is in good agreement with the experimental results (−84.5 mT; note the theoretical computation correctly predicted the trend of the change of the magnitude of the ZFS D values) [53]. The contribution of SSC to the ZFS D tensor is −73.8 mT, and the contribution of SOC to the ZFS D tensor is much smaller (7.4 mT).

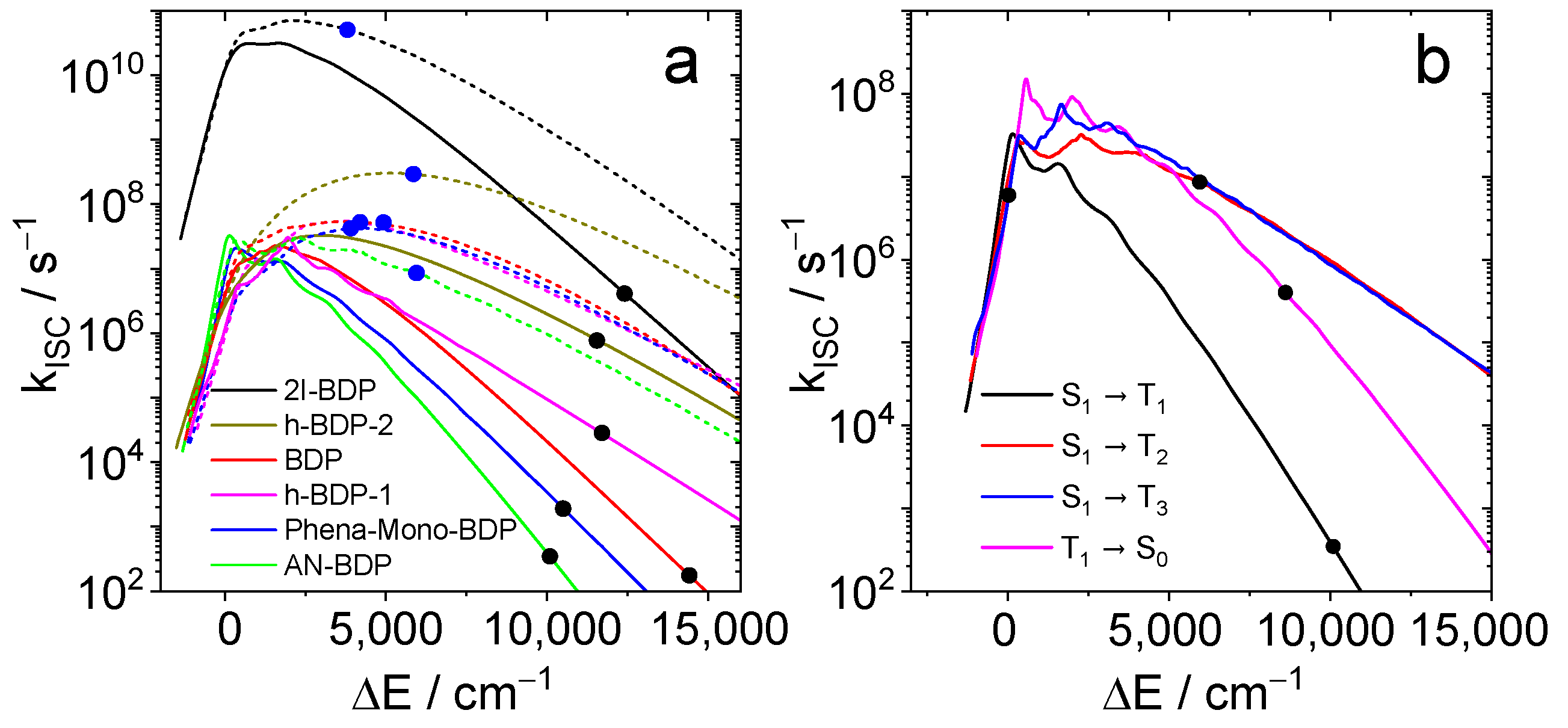

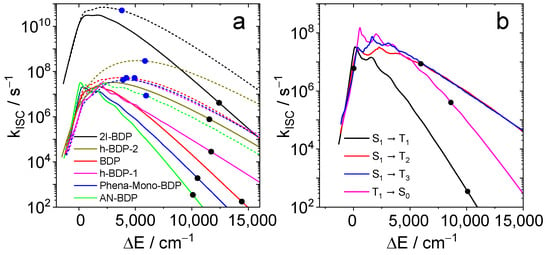

For the calculation of the ISC rate constants, the geometries of the states S1, T1, and T2 were optimized by TDDFT using the CAM-B3LYP functional and the def2-SVP basis set. The Hessian matrices of all states were calculated, all stationary points are minimal. For each pair of states, the SOCMEs and their derivatives with respect to all normal coordinates were calculated. The ORCA 6.0 programs [61] were used, in particular the ESD [62] module. These data were subsequently used by our own program [63], which determines the ISC rate constants (both Franck–Condon and Herzberg–Teller terms) as function of the energy gap.

The results are summarized in Figure 11. For all compounds, the S1 → T1 rate constant at the calculated energy gap is smaller than 107 s−1. Hence, this channel should not contribute significantly to the decay of S1 in these compounds. When T2 is considered as final state of the ISC (dotted lines and blue dots), smaller energy gaps and larger rate constants are found. The largest value (5.1 × 1010 s−1) is obtained for 2I-BDP. The other rates are still small compared to the radiative rate of fluorescence. Hence, they are compatible with moderate quantum yields for both fluorescence and triplets. The calculated rate constants (3.5 × 102 s−1 for T1, 8.6 × 106 s−1 for T2, and 6.0 × 106 s−1 for T3) are rather small compared to the radiative rate constants. The sum of the latter two comprise about 10% of the radiative rate, which could explain a triplet yield of similar magnitude. The rate constant for the transition T1 → S0 (4.0 × 105 s−1) corresponds to a triplet lifetime of 2.5 µs, whereas the observed lifetime is larger by a factor of ca. 200. This is probably due to the use of the harmonic approximation which leads to overestimation of the rate constant with an increasing energy gap.

Figure 11.

(a) Calculated ISC rate constants as function of the energy gap. The colors correspond to 2I-BDP (black), BDP (red), helical-BDP-1 (magenta) helical-BDP-2 (brown), Phena-Mono-BDP (blue) and AN-BDP (green). Full lines are the S1-T1 rates; dotted lines are S1-T2 rates. Black dots indicate the calculated S1/T1 energy gaps; blue dots indicate the calculated S1/T2 energy gaps. (b) ISC rate constants for AN-BDP as function of the energy gap for the transitions S1-T1 (black), S1-T2 (red), S1-T3 (blue), and T1-S0 (magenta). The dots indicate the calculated energy gaps.

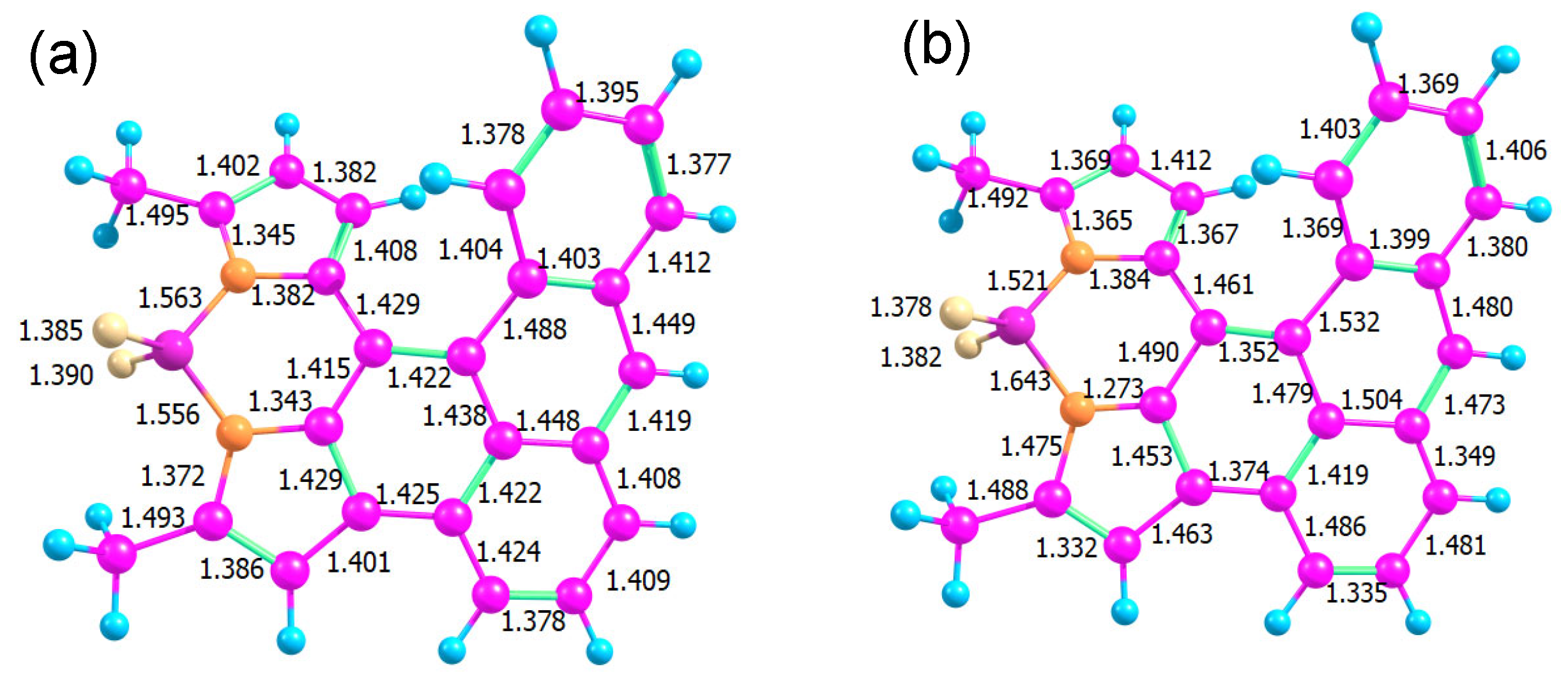

The optimized ground state geometry of AN-BDP is presented in Figure 12. The low quantum yields of AN-BDP both for fluorescence and triplet in polar solvents could be explained by a fast, radiation-less decay of S1 directly to the ground state. In a helicene-like structure, a ring closure at the overlapping ends of the helix is a possible path: for example, for a helicene with two thiophene units, such a ring closure was found along a barrierless path from the excited singlet state [63]. The resulting structure is a biradical with almost degenerate singlet and triplet. From this point, another path leads without a barrier back to the molecular singlet ground state. We checked the reaction path for such a ring closure in AN-BDP but found a substantial barrier in this case.

Figure 12.

Bond lengths in the optimized structures of the electronic ground state S0 (a) and the conical intersection (b).

Another option is a conical intersection (CI) between S1 and S0 states at an energy below or near the Franck–Condon point (Figure 12b). Such a conical intersection has been found for BDP analogue phenyl–BDP at a geometry where the BDP unit is bent and the phenyl ring is “coplanar” with the BDP unit [55,64,65]. A search for a CI requires a wavefunction of the same quality for S0 and S1; hence, we cannot use a single reference method (like DFT). We used an algorithm based on the gradient projection method [66] implemented in a home-written program [67] that treats constraints in an orthogonal basis and acts as a frontend to the Firefly quantum chemistry program. Our search for a CI was successful with a surprising result: the main geometrical changes occur in the bond lengths connecting the BDP and the AN units, accompanied by a reorganization of bond alternation in some of the aromatic rings.

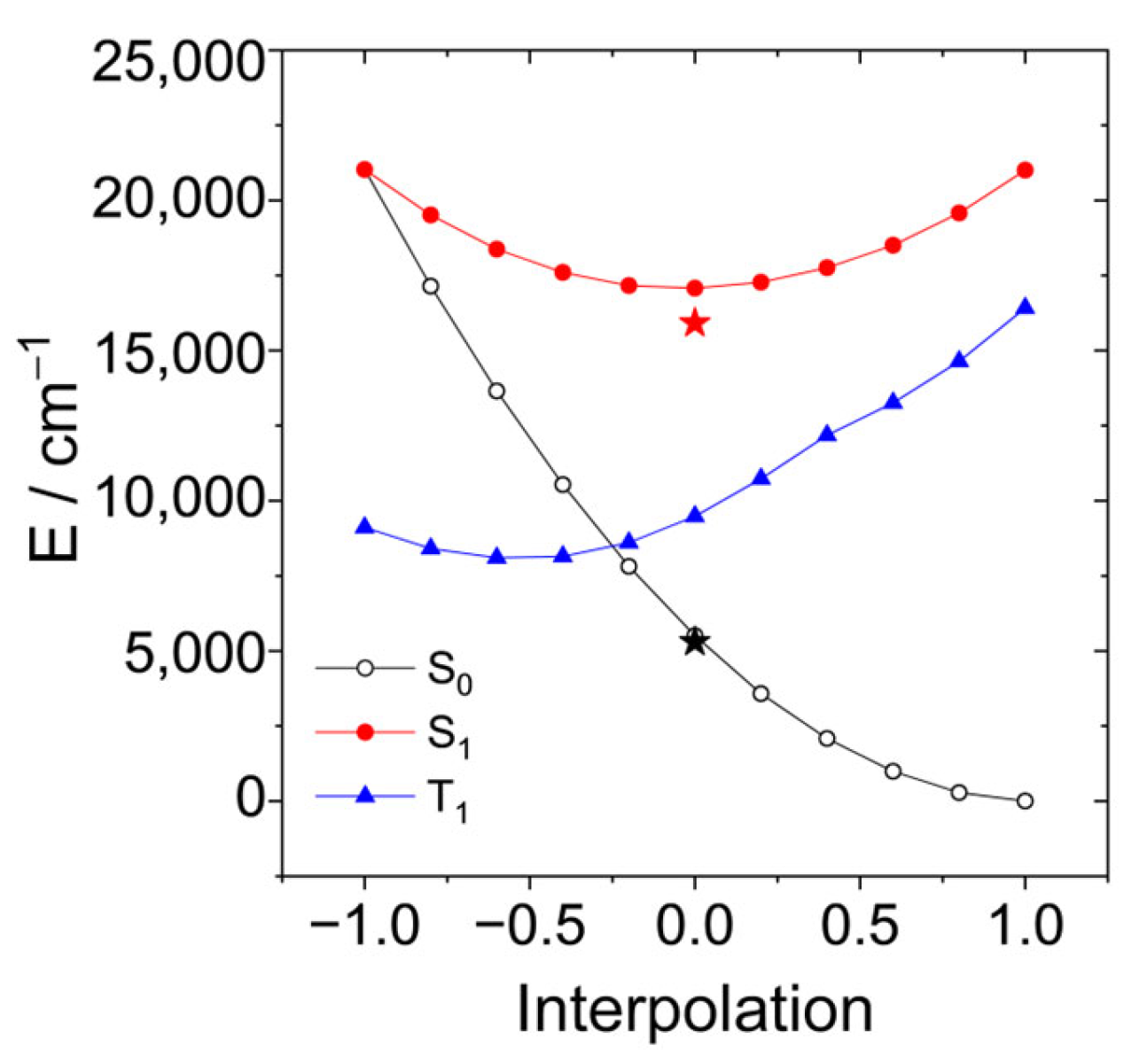

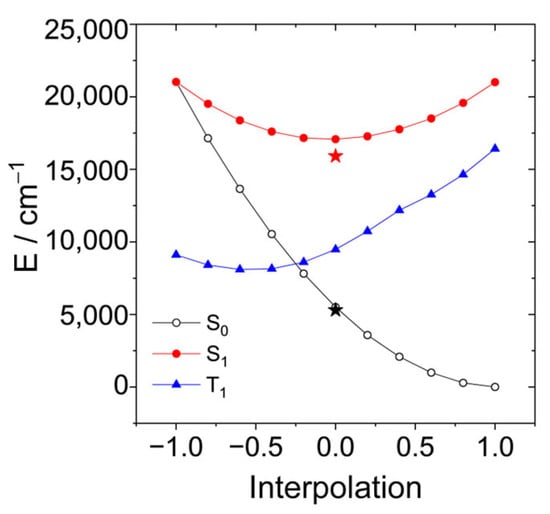

A linear interpolation between these structures yields the potential energy curves shown in Figure 13. The optimized energy of the S1 state and the corresponding energy of the ground state are shown as red and black stars. The FC-point is at the same energy as in the case when the increasing polarity of the solvent lowers the barrier. Although we do not find a vanishing barrier with this level of theory, the results provide an explanation that the radiation-less process becomes more efficient in more polar solvents. (Note that the transition from the S1 to the S0 state usually occurs when both states approach within the energy of a few vibrational quanta.) This can explain the absence of fluorescence and the missing triplet yield of AN-BDP.

Figure 13.

Linear interpolation between the structures of the conical intersection (r = −1) and the ground state (r = +1). The structures at the endpoints were optimized with state-averaged CASSCF(10|10) and the cc-pVDZ basis. The energy of the triplet state is shown as the blue curve. The optimized energy of the S1 state and the corresponding energy of the ground state at this geometry are shown as red and black stars.

In the CI, there is no barrier between both structures on the surfaces of S0 (black), S1 (red), and T1 (blue). Therefore, decay to the CI can compete with vibrational relaxation. The optimized structure of the S1 state is somewhat below the CI. Hence, when vibrational relaxation occurs before the system can reach the CI, internal conversion via the CI requires an activation energy. Table 3 shows these activation energies calculated at the same level of theory, CASSCF(10|10)/cc-pVDZ, but considering various solvents with the PCM model.

Table 3.

Energy barrier (ΔE, in cm−1 units) from the optimized structure of S1 towards the CI in various solvents (ACE: acetone; TOL: toluene; CHX: cyclohexane).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analytical Measurements

All chemicals used in the synthesis are analytically pure and were used as-received. Solvents were dried and distilled before used for synthesis. The UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on an Agilent 8453 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Ltd., Foster City, CA, USA). Fluorescence spectra were recorded on an RF-5301 PC spectrofluorometer (Shimadzu Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). Luminescence lifetimes were measured on an OB920 fluorescence lifetime instrument (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Edinburgh, UK).

3.2. Nanosecond Transient Absorption Spectra

The nanosecond transient absorption spectra were measured on an LP980 laser flash photolysis spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., UK). The samples were photoexcited with an OpoletteTM 355II+UV nanosecond-pulsed laser (OPOTEK, Carlsbad, CA, USA; typical pulse length: 7 ns. Pulse repetition: 20 Hz. Peak OPO energy: 5 mJ). The wavelength is tunable in the range 410–2200 nm. Lifetime values were obtained with the L900 software (https://www.edinst.com/product/l900-software/, accessed on 26 January 2026) by fitting exponential functions to the decay traces. The intrinsic triplet state lifetimes were obtained with a kinetic model that the TTA self-quenching effect is considered [53,55]. All samples in flash photolysis experiments were deaerated with N2 for ca. 15 min before measurement.

3.3. TREPR Spectroscopy

The magnetic resonance experiments were carried out in frozen solutions of the compounds with a mixture of toluene/MeTHF (3:1, v/v) as solvent. Optical excitation was carried out with an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) system (LP603, SolarLS, Minsk, Belarus) pumped by an Nd:YAG laser (LQ 629 SolarLS, Minsk, Belarus) with a pulse energy of 1 mJ with pulse length = 10 ns. The repetition rate of the laser was set to 100 Hz. Polarization for the MPS experiments was obtained using a Glan laser polarizer (SolarLS, Minsk, Belarus) in combination with a half-wave plate. The TR CW EPR spectra were obtained by the summation of the data in different time windows after the laser pulse. The EPR spectra were simulated using the EasySpin (6.0.4) package implemented in the MATLAB (R2021b) programming language [68].

3.4. Theoretical Computation

The ground states geometry of the compound was optimized with Gaussian 16 [69]. The TDDFT computation was done at the optimized ground state geometry. The excited state property including the ISC rate constants were calculated with ORCA 6.0 program [61]; this involves optimization of the geometries of the initial and final states of each transition, including calculation of the hessian matrices. The CAM-B3LYP functional and the def2-SVP basis set were used throughout, using DFT for the ground state and TDDFT for all excited states. The search and optimization of the conical intersection used the CASSCF method with the cc-pVDZ basis set using the Firefly QC package [70] (which is partially based on the GAMESS (US) [71] source code) with our own optimizer [67] as frontend.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we studied the intersystem crossing (ISC) of an anthracene-fused boron–dipyrromethene (AN-BDP) derivative, which has highly twisted molecular structure. The fused anthryl and the BDP in AN-BDP units both adopt distorted geometry (with ca. 12° of torsion), and there is large dihedral angle between the two units (ca. 49.7°). The fluorescence quantum yields are highly dependent on the solvent polarity (59~3% in toluene and acetonitrile); yet, the fluorescence emission wavelength does not change in different solvents. The nanosecond transient absorption spectra indicate that the triplet state is long-lived, with intrinsic triplet state lifetime of 551 μs. Interestingly, the severely twisted structure only show a moderate ISC yield (10%), which is different from the trend found for helicene. Femtosecond transient absorption spectra indicate the intersystem crossing (ISC) is slow (>1.5 ns). The time-resolved electron paramagnetic resonance (TREPR) spectra show smaller zero-field-splitting D (−71.4 mT) and E tensors (16.2 mT) as compared to the triplet excited state of the iodinated native BDP (−104.6 mT and 22.8 mT, respectively), inferring that triplet-state wave function of the compound is delocalized over the twisted molecular framework. Theoretical computation indicated a decreased energy barrier from the relaxed S1 state to a conical interaction (CI) of the S1 and the S0 state potential curves in polar solvents, which agrees with the quenched fluorescence in polar solvents compared to that in non-polar solvents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervise the research, and funding acquisition, J.Z.; TREPR spectra recording and data analysis, A.A.S. and V.K.V.; Theoretical chemistry analysis, B.D.; Synthesis and steady-state spectral studies and nanosecond transient absorption spectral studies, Y.W., Y.H., B.L. and Y.D. All the corresponding authors wrote the manuscript, and all the authors took part in the revising of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSFC (W2521100, U25A20619 and 22473021), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFE0197600), the Research and Innovation Team Project of Dalian University of Technology (DUT2022TB10), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DUT22LAB610) and the State Key Laboratory of Fine Chemicals of Dalian University of Technology for financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

A. Sukhanov and V. Voronkova acknowledge financial support from the government assignment for FRC Kazan Scientific Center of RAS. A. Sukhanov and V. Voronkova are grateful to the Collective Spectro-Analytical Center for Physicochemical Research of the Structure, Properties and Composition of Substances and Materials of the Federal Research Center Kazan Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences for technical support of the studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smith, M.B.; Michl, J. Singlet Fission. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6891–6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marian, C.M. Spin–Orbit Coupling and Intersystem Crossing in Molecules. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryshnikov, G.; Minaev, B.; Ågren, H. Theory and Calculation of the Phosphorescence Phenomenon. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 6500–6537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, D.J.; Farawar, A.; Mazzella, P.; Leroy-Lhez, S.; Williams, R.M. Making Triplets from Photo-Generated Charges: Observations, Mechanisms and Theory. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, C.; Hoehn, S.; Krul, S.; Jockusch, S.; Yang, S.; Seth, S.K.; Lee, E.; Xiao, H.; Crespo-Hernández, C.E. Electronic Relaxation Pathways in Thio-Acridone and Thio-Coumarin: Two Heavy-Atom-Free Photosensitizers Absorbing Visible Light. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 28980–28991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Xia, W. Photoredox Functionalization of C–H Bonds Adjacent to a Nitrogen Atom. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7687–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prier, C.K.; Rankic, D.A.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, D.P.; König, B. The Photocatalyzed Meerwein Arylation: Classic Reaction of Aryl Diazonium Salts in a New Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4734–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, D.; Fagnoni, M.; Albini, A. Photoorganocatalysis. What for? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, S.G.; You, Y. Boron Dipyrromethene (BODIPY)-Based Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 11169–11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharchenko, O.; Gouju, J.; Verdu, I.; Bastiat, G.; Hudhomme, P.; Passirani, C.; Saulnier, P.; Krupka, O. Heavy-Atom-Free Photosensitizer-Loaded Lipid Nanocapsules for Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 3086–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Sun, J.; Guo, S. Triplet Photosensitizers: From Molecular Design to Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5323–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkaew, A.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, H.B.; Kiew, L.V.; Chung, L.Y.; Burgess, K. BODIPY Dyes in Photodynamic Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kolemen, S.; Yoon, J.; Akkaya, E.U. Activatable Photosensitizers: Agents for Selective Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Rachford, T.N.; Castellano, F.N. Photon Upconversion Based on Sensitized Triplet-Triplet Annihilation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2560–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ji, S.; Guo, H. Triplet-Triplet Annihilation Based Upconversion: From Triplet Sensitizers and Triplet Acceptors to Upconversion Quantum Yields. RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Y.C.; Weder, C. Low-Power Photon Upconversion Through Triplet-Triplet Annihilation in Polymers. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 20817–20830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monguzzi, A.; Tubino, R.; Hoseinkhani, S.; Campione, M.; Meinardi, F. Low Power, Non-Coherent Sensitized Photon Up-Conversion: Modelling and Perspectives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 4322–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.; Liang, Z. Photon Upconversionfrom Two-Photon Absorption (TPA) to Triplet–Triplet Annihilation (TTA). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 10818–10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, N.; Kimizuka, N. New Triplet Sensitization Routes for Photon Upconversion: Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Molecules, Inorganic Nanocrystals, and Singlet-to-Triplet Absorption. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.K.; Shokri, S.; Wiederrecht, G.P.; Gosztola, D.J.; Ayitou, A.J.-L. New Perspectives for Triplet–Triplet Annihilation Based Photon Upconversion Using All-Organic Energy Donor & Acceptor Chromophores. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 5809–5818. [Google Scholar]

- Turro, N.J.; Ramamurthy, V.; Scaiano, J.C. Principles of Molecular Photochemistry: An Introduction; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, A.; Killoran, J.; O’Shea, C.; Kenna, T.; Gallagher, W.M.; O’Shea, D.F. In Vitro Demonstration of the Heavy-Atom Effect for Photodynamic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 10619–10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzel, P.; Holzapfel, M.; Schmiedel, A.; Krummenacher, I.; Braunschweig, H.; Wodyński, A.; Kaupp, M.; Würthner, F.; Lambert, C. Excited States and Spin–Orbit Coupling in Chalcogen Substituted Perylene Diimides and Their Radical Anions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 26254–26268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogo, T.; Urano, Y.; Ishitsuka, Y.; Maniwa, F.; Nagano, T. Highly Efficient and Photostable Photosensitizer Based on BODIPY Chromophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12162–12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Guo, H.; Wu, W.; Ji, S.; Zhao, J. Organic Triplet Sensitizer Library Derived from a Single Chromophore (BODIPY) with Long-Lived Triplet Excited State for Triplet–Triplet Annihilation Based Upconversion. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 7056–7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröring, M.; Krüger, R.; Link, S.; Kleeberg, C.; Köhler, S.; Xie, X.; Ventura, B.; Flamigni, L. Bis(BF2)-2,2′-Bidipyrrins (BisBODIPYs): Highly Fluorescent BODIPY Dimers with Large Stokes Shifts. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 2976–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, B.; Marconi, G.; Bröring, M.; Krüger, R.; Flamigni, L. Bis(BF2)-2,2′-Bidipyrrins, a Class of BODIPY Dyes with New Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisei, F.; Lima, J.C.; Ortica, F.; Aloisi, G.G.; Costa, M.; Leitão, E.; Abreu, I.; Dias, A.; Bonifácio, V.; Medeiros, J.; et al. Photophysical Properties of Hydroxy-Substituted Flavothiones. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 6095–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyar, S.M.; Margulies, E.A.; Horwitz, N.E.; Brown, K.E.; Krzyaniak, M.D.; Wasielewski, M.R. Photogenerated Quartet State Formation in a Compact Ring-Fused Perylene-Nitroxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 13560–13569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Barbon, A.; Toffoletti, A.; Liu, Y.; An, Y.; Xu, L.; Karatay, A.; Yaglioglu, H.G.; Yildiz, E.A.; et al. Radical-Enhanced Intersystem Crossing in New Bodipy Derivatives and Application for Efficient Triplet-Triplet Annihilation Upconversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7831–7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, K.; Hou, Y.; Che, Y.; Liu, L.; Jia, D. Recent Progress in Heavy Atom-Free Organic Compounds Showing Unexpected Intersystem Crossing (ISC) Ability. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 3692–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, J.W.; Darmanyan, A.P.; Foote, C.S.; Diederich, F.N.; Whetten, R.L.; Rubin, Y.; Alvarez, M.M.; Anz, S.J. Photophysical Properties of Sixty Atom Carbon Molecule (C60). J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, M.; Donckt, E.V. Intersystem Crossing in the Helicenes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1975, 36, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Brovelli, S.; Coropceanu, V.; Beljonne, D.; Cornil, J.; Bazzini, C.; Caronna, T.; Tubino, R.; Meinardi, F.; Shuai, Z.; et al. Intersystem Crossing Processes in Nonplanar Aromatic Heterocyclic Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 10490–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Z.; Fu, H. Exceptional Intersystem Crossing in Di(perylene bisimide)s: A Structural Platform toward Photosensitizers for Singlet Oxygen Generation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 2499–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, K.; Mallia, A.R.; Reddy, V.S.; Hariharan, M. Access to Triplet Excited State in Core-Twisted Perylenediimide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 8443–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, K.; Mallia, A.R.; Muraleedharan, K.; Hariharan, M. Enhanced Intersystem Crossing in Core-Twisted Aromatics. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, A.; Das, P.P.; Vinod, K.; Maret, P.; Lijina, D.M.P.; Engels, B.; Hariharan, M. Core-Twist Modulated Intersystem Crossing in a π-Fused Single-Molecule. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 4643–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Yan, Y.; El-Zohry, A.M.; Toffoletti, A.; Zhao, J.; Barbon, A.; Dick, B.; Mohammed, O.F.; Han, G. Elucidation of the Intersystem Crossing Mechanism in a Helical BODIPY for Low-Dose Photodynamic Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16114–16121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Sakai, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Kawamata, J.; Hasobe, T. Systematic Control of Structural and Photophysical Properties of π-Extended Mono- and Bis-BODIPY Derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Kumar, P.; Maity, P.; Kurganskii, I.; Li, S.; Elmali, A.; Zhao, J.; Escudero, D.; Wu, H.; Karatay, A.; et al. Twisted BODIPY Derivative: Intersystem Crossing, Electron Spin Polarization and Application as a Novel Photodynamic Therapy Reagent. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 8641–8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levanon, H.; Norris, J.R. The Photoexcited Triplet State and Photosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 1978, 78, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S. Transient EPR. eMagRes 2017, 6, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Richert, S.; Tait, C.E.; Timmel, C.R. Delocalisation of Photoexcited Triplet States Probed by Transient EPR and Hyperfine Spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 2017, 280, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, M.; Miyokawa, K.; Kurashige, Y. The Molecular Mechanism of the Triplet State Formation in Bodipy-Phenoxazine Photosensitizer Dyads Confirmed by ab initio Prediction of the Spin Polarization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 29449–29456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C. Asymmetric Anthracene-Fused BODIPY Dye with Large Stokes Shift: Synthesis, Photophysical Properties and Bioimaging. Dyes Pigm. 2016, 126, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhina, T.; Amirjalayer, S.; Woutersen, S.; Bonn, D.; Brouwer, A.M. Ultrafast Dynamics and Solvent-Dependent Deactivation Kinetics of BODIPY Molecular Rotors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 19998–20007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, G.; Ziessel, R.; Harriman, A. The Chemistry of Fluorescent Bodipy Dyes: Versatility Unsurpassed. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1184–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziessel, R.; Harriman, A. Artificial Light-Harvesting Antennae: Electronic Energy Transfer by Way of Molecular Funnels. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Mack, J.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Z. Structural Modification Strategies for the Rational Design of Red/NIR Region Bodipys. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 4778–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatov, M.A.; Karuthedath, S.; Polestshuk, P.M.; Savoie, H.; Flanagan, K.J.; Sy, C.; Sitte, E.; Telitchko, M.; Laquai, F.; Boyle, R.W.; et al. Generation of Triplet Excited States via Photoinduced Electron Transfer in meso-anthra-BODIPY: Fluorogenic Response toward Singlet Oxygen in Solution and in Vitro. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6282–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sukhanov, A.A.; Toffoletti, A.; Sadiq, F.; Zhao, J.; Barbon, A.; Voronkova, V.K.; Dick, B. Insights into the Efficient Intersystem Crossing of Bodipy-Anthracene Compact Dyads with Steady-State and Time-Resolved Optical/Magnetic Spectroscopies and Observation of the Delayed Fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Jiao, C.; Huang, X.; Huang, K.-W.; Chin, W.-S.; Wu, J. Anthracene-Fused BODIPYs as Near-Infrared Dyes with High Photostability. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6026–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Hou, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhao, J.; Ji, S.; Zhong, F.; Dede, Y.; Dick, B. Different Quenching Effect of Intramolecular Rotation on the Singlet and Triplet Excited States of Bodipy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, H.L.; Kirmaier, C.; Yu, L.; Thamyongkit, P.; Youngblood, W.J.; Calder, M.E.; Ramos, L.; Noll, B.C.; Bocian, D.F.; Scheidt, W.R.; et al. Structural Control of the Photodynamics of Boron−Dipyrrin Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 20433–20443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Dick, B.; Zhao, J. Twisted Bodipy Derivative as a Heavy-Atom-Free Triplet Photosensitizer Showing Strong Absorption of Yellow Light, Intersystem Crossing, and a High-Energy Long-Lived Triplet State. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5535–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, N.; Yamauchi, S. Short-Lived Excited Triplet States Studied by Time-Resolved EPR Spectroscopy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2003, 4, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoletti, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Tommasini, M.; Barbon, A. Precise Determination of the Orientation of the Transition Dipole Moment in A Bodipy Derivative by Analysis of the Magnetophotoselection Effect. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 20497–20503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Feng, N. Photoinduced Electron Transfer-based Halogen-free Photosensitizers: Covalent meso-Aryl (Phenyl, Naphthyl, Anthryl, and Pyrenyl) as Electron Donors to Effectively Induce the Formation of the Excited Triplet State and Singlet Oxygen for BODIPY Compounds. Chem. Asian J. 2017, 12, 2447–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, B.; Neese, F.; Izsak, R. On the Theoretical Prediction of Fluorescence Rates from First Principles Using the Path Integral Approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 034104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergwinkl, S.; Nuernberger, P.; Dick, B.; Kutta, R.J. Enhanced Intersystem Crossing in a Thiohelicene. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202300343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prlj, A.; Fabrizio, A.; Corminboeuf, C. Rationalizing Fluorescence Quenching in meso-BODIPY Dyes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 32668–32672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prlj, A.; Vannay, L.; Corminboeuf, C. Fluorescence Quenching in BODIPY Dyes: The Role of Intramolecular Interactions and Charge Transfer. Helv. Chim. Acta 2017, 100, e1700093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, F.; Blancafort, L.; Bearpark, M.J.B.; Robb, M.A. New Algorithms for Optimizing and Linking Conical Intersection Points. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, B. Gradient Projection Method for Constraint Optimization and Relaxed Energy Paths on Conical Intersection Spaces and Potential Energy Surfaces. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, S.; Schweiger, A. EasySpin, a Comprehensive Software Package for Spectral Simulation and Analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006, 178, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Granovsky, A.A. Firefly Version 8. 2013. Available online: http://classic.chem.msu.su/gran/firefly/index.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Schmidt, M.W.; Baldridge, K.K.; Boatz, J.A.; Elbert, S.T.; Gordon, M.S.; Jensen, J.H.; Koseki, S.; Matsunaga, N.; Nguyen, K.A.; Su, S.; et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.