Abstract

Investigating aluminum nitride (AlN) clusters is essential for understanding the properties of bulk AlN materials. The incorporation of hydrogen into AlN clusters represents an effective strategy for structural modification and for tuning their physicochemical properties. In this work, we conducted density functional theory (DFT) calculations on the dynamically stable global-minimum (GM) structure of Al6N6H8. Compared to the precursor Al6N6 cluster, the incorporation of eight hydrogen atoms achieves coordination saturation of all aluminum and nitrogen atoms, inducing a structural transformation from a hexagonal prism with D3d symmetry to a cuboid structure with D2h symmetry. The HOMO–LUMO gap of the Al6N6H8 cluster is increased by 1.85 eV compared to that of Al6N6, indicating a remarkable enhancement in stability. Chemical bonding and natural bond orbital (NBO) charge analyses reveal that the Al–N, Al–H, and N–H bonds are predominantly covalent single bonds, with a degree of ionicity arising from electronegativity differences. The hydrogen atoms bonded to Al and N can be substituted with a series of other atoms or functional groups, thereby further tuning the structures and properties of the clusters. To facilitate future experimental characterization, the infrared spectrum of Al6N6H8 was calculated, which shows an overall blue shift in the Al–N bond’s bending and stretching vibrations compared to those in the Al6N6 cluster.

1. Introduction

Aluminum nitride (AlN), an important wide bandgap semiconductor material, typically crystallizes in the hexagonal wurtzite structure. It possesses excellent thermal conductivity, a low thermal-inflate coefficient, high chemical stability, and favorable dielectric properties, exhibiting broad application prospects in fields such as optoelectronic devices [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Aluminum nitride clusters, serving as an intermediate system bridging the atomic scale and bulk materials, have become a focus of theoretical research concerning their structures, stability rules, and growth mechanisms [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Chang et al. [10] employed density functional theory (DFT) to investigate the structures, energies, and vibrational frequencies of (AlN)x (x = 1, 2, 4, 6, 12) clusters, finding that cage-like structures gradually become more stable than planar structures as their size increases, with (AlN)12 exhibiting high symmetry and stability. Recently, Xu et al. [13], based on Fukui function analysis and transition-state searches, studied the growth mechanism of AlnNn (n = 2–9) clusters, proposing a transition from planar to three-dimensional cage-like structures during their growth. Costales et al. [7] utilized global optimization methods to investigate (AlN)n (n = 1–100) clusters, revealing that their structural evolution with size can be divided into three stages: Small-sized clusters (n = 2–5) are dominated by planar ring structures. Medium-sized clusters (n = 6–40) show competition between stacked rings and globular-like empty cages, and large-sized clusters (n > 40) develop interior atoms and exhibit a competition between tetrahedral- and octahedral-like features. This study also revealed that clusters with sizes of n = 6 and n = 12 are particularly stable in terms of energy, displaying “magic number” characteristics. These works lay a crucial foundation for understanding the stability and growth patterns of aluminum nitride clusters. As the smallest AlnNn-type three-dimensional aluminum nitride cluster, Al6N6 holds significant value for further investigation.

However, despite considerable research elucidating the structural and stability rules of aluminum nitride clusters, theoretical studies on ternary Al-N-H clusters in the existing literature remain very limited. Current investigations are primarily focused on small molecular systems [21,22,23,24,25]. Davy et al. investigated the structures of AlNH2, AlNH3, and AlNH4 clusters using ab initio molecular electronic structure methods [22], finding that the number of hydrogen atoms on the aluminum atom significantly modulates its Lewis acidity, thereby influencing the strength of the Al–N bond. Furthermore, the structures and reaction energies of cyclic and cage-like aluminum–nitrogen–hydrogen clusters have also attracted attention [23]. For instance, a comparison between the (HAl–NH)2 and (H2Al–NH2)2 tetrameric ring structures revealed that the transition from a saturated to an unsaturated ring requires higher energy, indicating that coordination-saturated AlNH clusters possess greater stability. While these studies provide a preliminary exploration of AlNH cluster systems, there is still no systematic report on how to precisely regulate their geometric structures and electronic properties through hydrogen atoms.

Previous studies have reported a fully hydrogenated Al6N6H12 [25] cluster that formally achieves tetracoordinate saturation by introducing one H atom to each Al and N atom of the pristine Al6N6. Nevertheless, this structure merely supplements the coordination number through the formation of Al–H and N–H bonds without altering the symmetry and hexagonal prism geometric framework of the Al6N6 core. Essentially, it is merely a “hydrogenated derivative” of the original structure, failing to induce substantial geometric reconstruction. This naturally leads to the following question: can hydrogenation be rationally designed to effectively modulate both the geometry and electronic properties of AlN clusters?

To address this, we propose a “selective hydrogenation” strategy for structural modification and property tuning of AlN clusters. Using the smallest three-dimensional AlnNn-type cluster, Al6N6 (0), as the precursor, the stepwise introduction of eight H atoms transforms the bilayer hexagonal prism into a cuboid-shaped Al6N6H8 cluster (1), accompanied by pronounced charge redistribution and chemical-bonding rearrangements. Notably, its HOMO–LUMO gap increases significantly, reflecting enhanced electronic stability.

This work thus demonstrates that targeted hydrogenation can fundamentally reshape the structures and properties of AlN clusters. The strategy not only enables precise tuning of geometry and stability but also provides reactive hydrogen sites in the newly formed surface Al–H/N–H bonds, laying the foundation for further functionalization and potential applications of the cluster.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Designing the Al6N6H8 Cluster

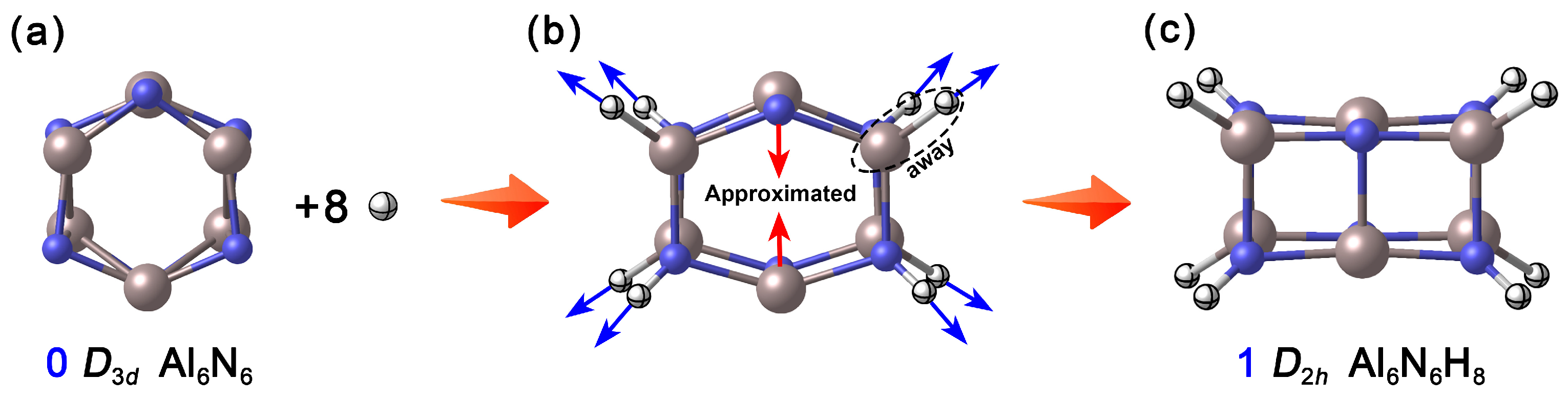

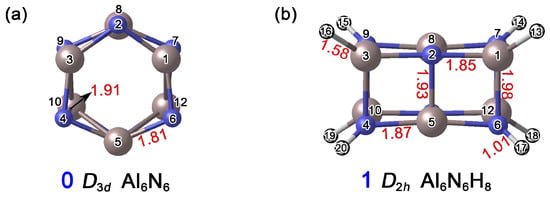

In nature, aluminum (Al) and nitrogen (N) tend to form tetrahedrally coordinated configurations, as exemplified by the wurtzite-type crystal structure of aluminum nitride (AlN). However, the neutral Al6N6 (0, D3d) [7,15] (Figure 1a) reported in existing theoretical studies adopts a hexagonal prism structure composed of two layers of six-membered rings, where each Al and N atom is tricoordinate. This low-coordination unsaturated state not only endows the cluster with high chemical reactivity but also provides room for its structural regulation and modification. Based on this, the present study proposes a “selective hydrogenation” modification strategy. How were the specific hydrogenation sites determined? To address this question, we systematically calculated the relative energies of various possible structures formed during the stepwise hydrogenation of Al6N6 (0). As shown in Figure S1, upon the introduction of the first hydrogen atom, hydrogen preferentially binds to a nitrogen atom. The structure with hydrogen attached to nitrogen is approximately 34.3 kcal·mol−1 lower in energy than the configuration where hydrogen is bonded to an aluminum atom. When adding the second hydrogen atom, it tends to bond to the aluminum atom located on the same side as the initially hydrogenated nitrogen atom. Calculation results indicate that the third and fourth hydrogen atoms preferentially occupy the para-positioned nitrogen and aluminum atoms, respectively. In general, hydrogen atoms added in odd-numbered steps exhibit a stronger tendency to bond with nitrogen atoms, while those added in even-numbered steps favor attachment to aluminum atoms situated on the same side as previously hydrogenated nitrogen atoms. When eight hydrogen atoms are introduced, the four Al atoms and four N atoms on two opposite quadrangular side faces of Al6N6 (0) are hydrogenated, constructing the Al6N6H8 cluster. Interestingly, during the geometry optimization process, the hydrogenation sites are stretched outward due to the formation of Al–H and N–H covalent bonds (4 each), leading to the distortion of the hexagonal prism framework. Meanwhile, the unhydrogenated, para-positioned Al and N atoms on the other two sides approach each other under the transfer of skeletal tension, ultimately forming a new set of Al–N single bonds in the upper and lower layers, respectively. As shown Figure 1, this synergistic rearrangement drives a fundamental transformation of the cluster structure: from the pristine honeycomb-like hexagonal prism to a cuboid configuration. As a result, all Al and N atoms achieve tetracoordinate saturation, and the overall shape and physicochemical properties of the cluster are significantly altered.

Figure 1.

Basic idea of designing Al6N6H8 (1) clusters. (a) Reported neutral Al6N6 cluster; (b) The trend of change when introducing eight hydrogen atoms; (c) Optimized Al6N6H8 cluster. The N atoms are shown in blue, Al in light pink, and H in white.

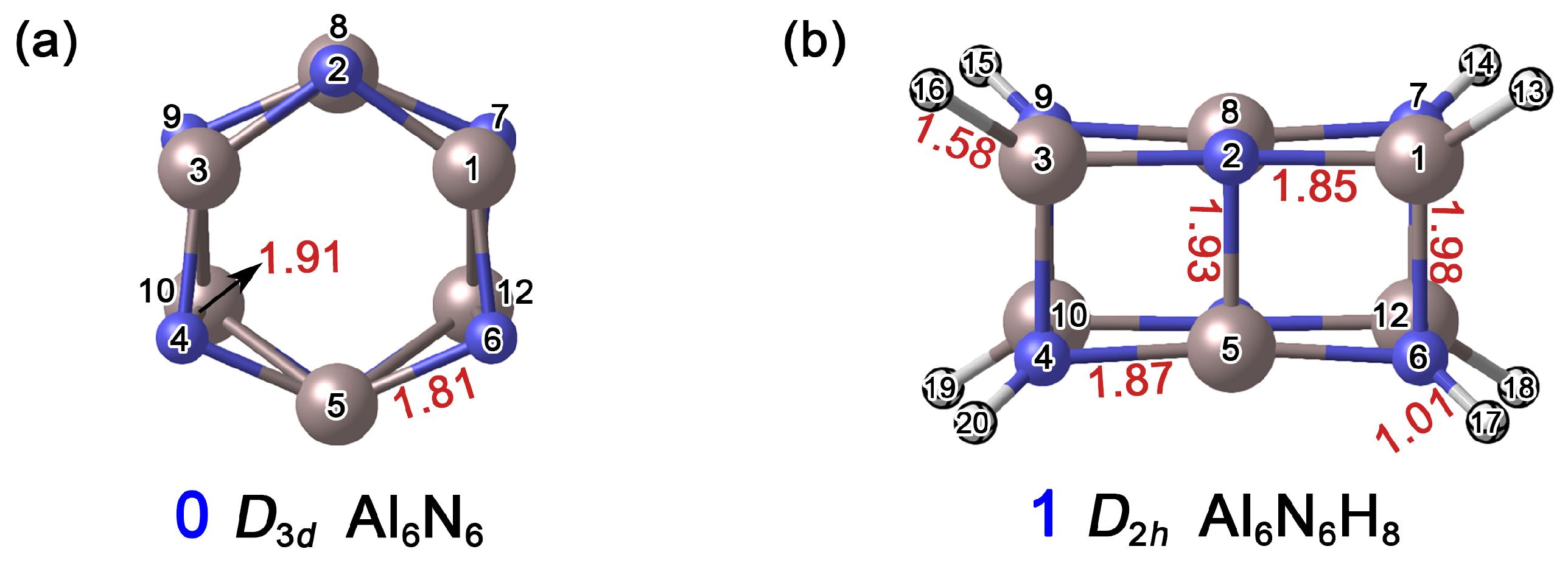

As shown in Figure 2, the distances between Al1–N2 and Al1–N7 in the Al6N6 (0) cluster are 1.81 Å and 1.91 Å, respectively. In cluster Al6N6H8 (1), the corresponding Al1–N2, Al1–N6, N4–Al5, and Al2–N5 bond lengths range from 1.85 Å to 1.98 Å. Based on the covalent radii recommended by Pyykkö [26], the upper limits for single-bond lengths of Al–N, Al–H, and N–H are 1.97 Å, 1.58 Å, and 1.03 Å, respectively, while the Al=N double bond is approximately 1.63 Å in length. Accordingly, all Al–N bonds in 0 can be preliminarily identified as single bonds. Similarly, the Al–N, Al–H, and N–H interactions in 1 are consistent with a single-bond character. Notably, the Al1–N6 distance in 1 is 1.98 Å, which slightly exceeds the covalent single-bond limit. This slight elongation can be attributed to the formation of new chemical bonds following hydrogen atom addition, where both steric hindrance and charge redistribution collectively lead to an outward displacement of the atoms.

Figure 2.

Optimized structures of (a) Al6N6 (0) and (b) Al6N6H8 (1) at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level. The interatomic distances are given in Å (red color). The atomic numbers are displayed in black font. The N atoms are shown in blue, Al in light pink, and H in white.

2.2. Structures and Stability

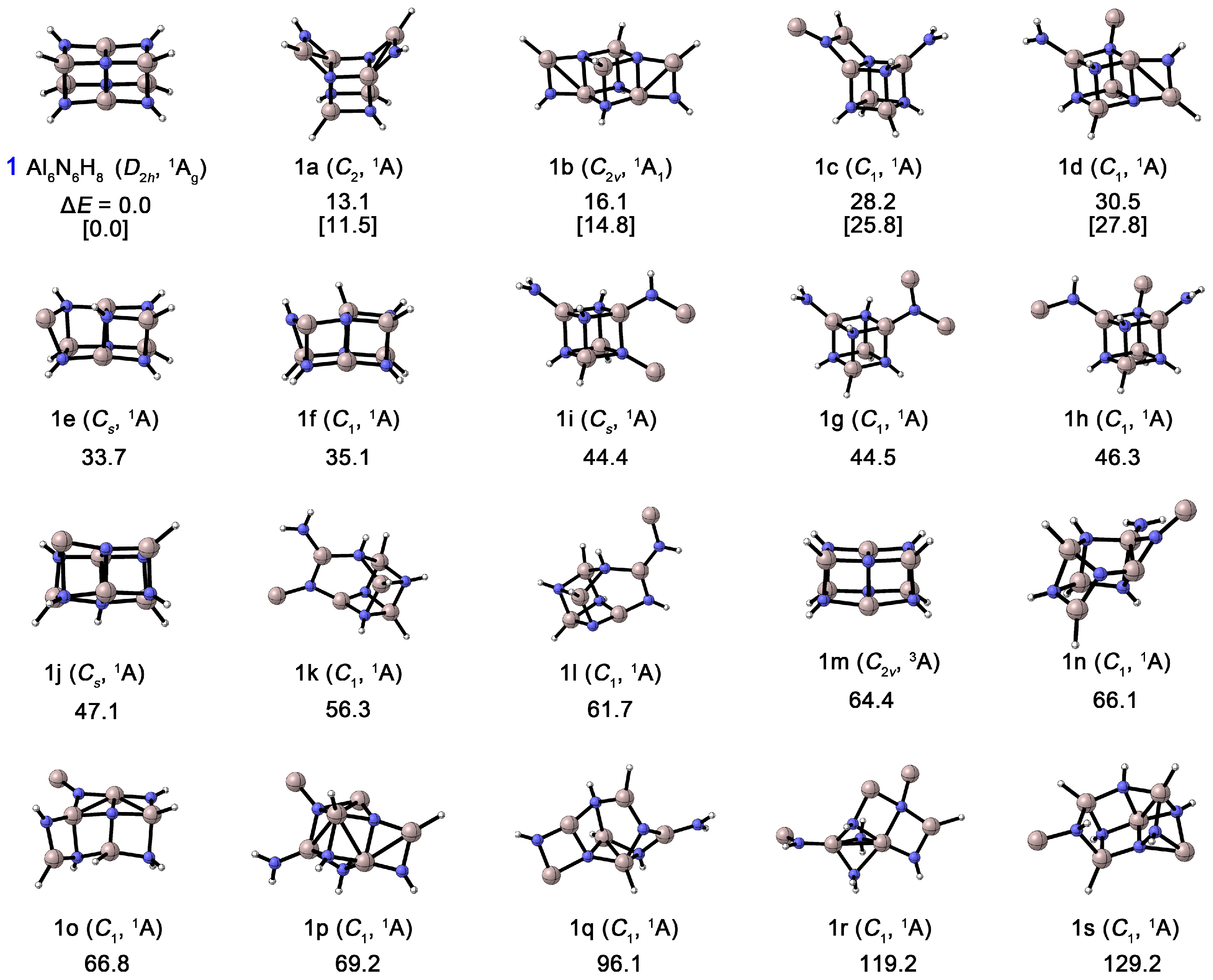

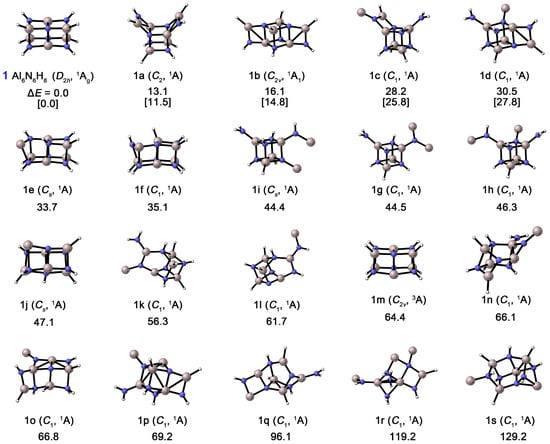

As shown in Figure 3, the thermodynamic stability of Al6N6H8 (1) was compared with that of its nineteen isomers. All structures were confirmed to possess no imaginary frequencies through harmonic vibrational frequency calculations, confirming that each structure corresponds to a true minimum on the potential energy surface. At the CCSD(T)/def2-TZVPP//PBE0/def2-TZVPP level, structure 1 is confirmed to be the global minimum (GM), lying at least 11.5 kcal mol−1 lower in energy than all other isomers. Furthermore, the T1 diagnostic values obtained from the CCSD(T) calculations for these isomers range from 0.012 to 0.014, which is well below the commonly adopted threshold of 0.02, indicating that this level of theory is reliable for describing these systems. The results show that the energy ordering remains fully consistent between CCSD(T) and PBE0, and a large energy gap (>10 kcal mol−1) exists between the GM structure (1) and the next most stable isomer (1a). This significant energy difference, together with the consistent energy trend, strongly supports the reliability of our conclusion regarding the most stable structure. Structure 1 possesses D2h symmetry, exhibiting an elongated rectangular shape, with eight hydrogen atoms bonded at its vertices. Notably, isomers containing the Al4N4 unit generally exhibit relatively lower energies. For instance, isomer 1a (C2) can be viewed as a GM-like structure in which two Al–N bonds on the shorter edge of the parallelepiped are broken, resulting in two AlNH2 units positioned on opposite sides of one face of the Al4N4 cube, resembling an “open box”. Isomer 1b (C2v) also retains the Al4N4 core, but the two AlNH2 units are arranged on opposite sides along the diagonal of the cube. Isomers 1c–1j likewise feature the central Al4N4 unit, with the remaining atoms forming various groups (e.g., NH2) attached irregularly at the cube vertices. In contrast, structures 1k–1s (except for the triplet state 1m), in which the Al4N4 unit is disrupted, are all at least 56.3 kcal mol−1 higher in energy than 1. The GM structure contains two coupled Al4N4 units, and its excellent thermodynamic stability suggests a high potential for formation and characterization in gas-phase experiments.

Figure 3.

Optimized global-minimum structures of Al6N6H8 (1) and the nineteen lowest-lying isomers (1a–1s). Relative energies are shown in kcal mol−1 at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level. Also shown are energetics data for the top 5 lowest-energy isomers at the single-point CCSD(T)/def2-TZVPP//PBE0/def2-TZVPP level with zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections at PBE0 (in square brackets).

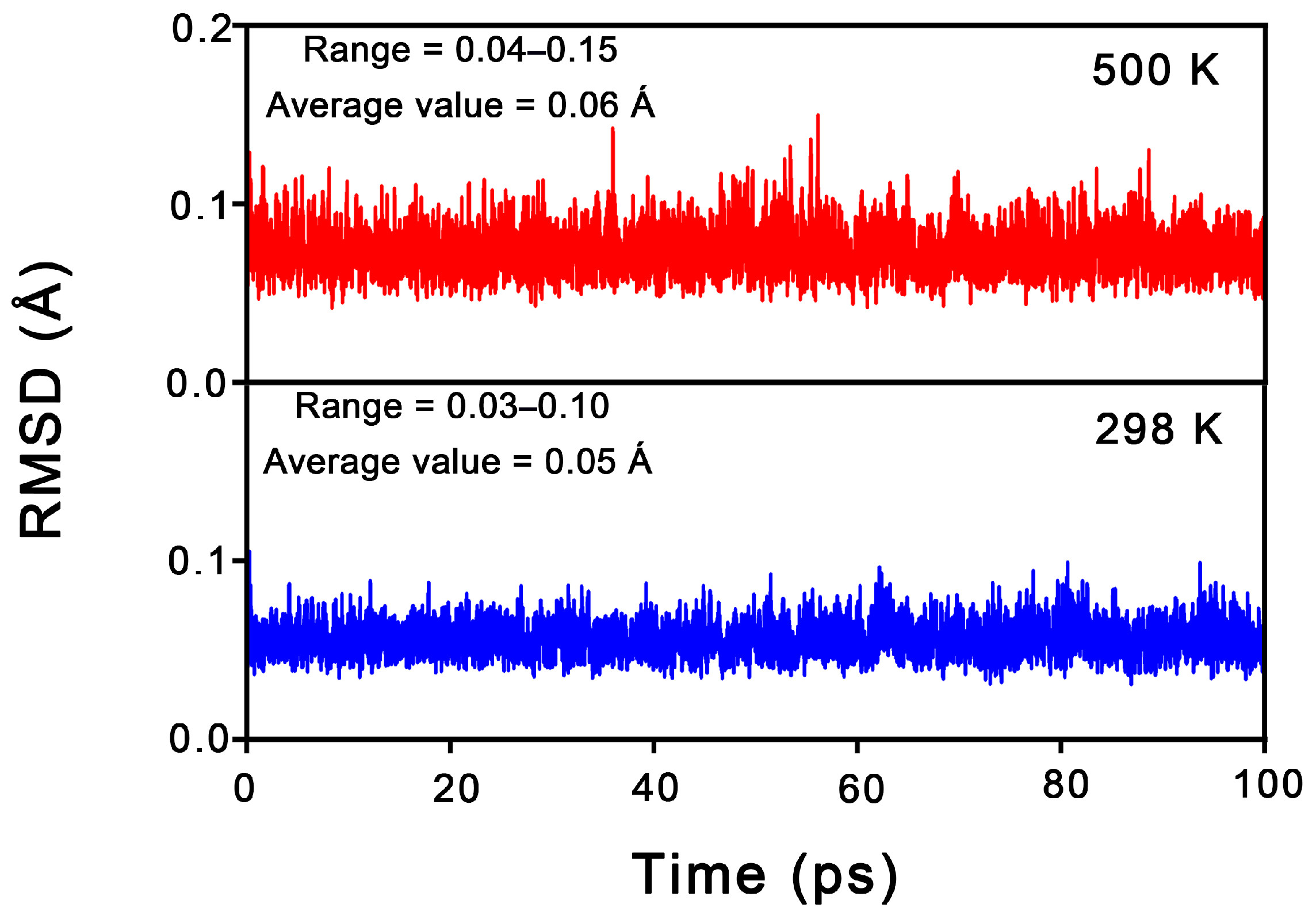

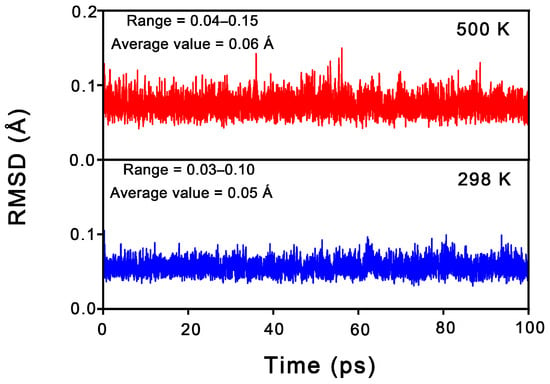

From an experimental characterization perspective, the dynamic stability of a cluster is as crucial as its thermodynamic stability. To assess this, Born–Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations were conducted for 1 at the PBE/DZVP level, with the time to 100 ps carried out at 298 K and 500 K. The structural evolution was described using the root mean square deviation (RMSD, in Å); smaller RMSD fluctuations correspond to greater dynamic stability. As shown in Figure 4, 1 exhibits relatively excellent dynamic stability at both 298 K and 500 K, maintaining its original framework throughout the simulations. The average RMSD values for 1 at 298 K and 500 K are 0.06 Å and 0.07 Å, respectively. These small values suggest that cluster 1 possesses strong resistance to isomerization and dissociation.

Figure 4.

RMSD (in Å) versus simulation time (in ps) for the BOMD simulations of Al6N6H8 (1) at the PBE/DZVP level and 298 and 500 K.

2.3. Electronic Structure Analyses

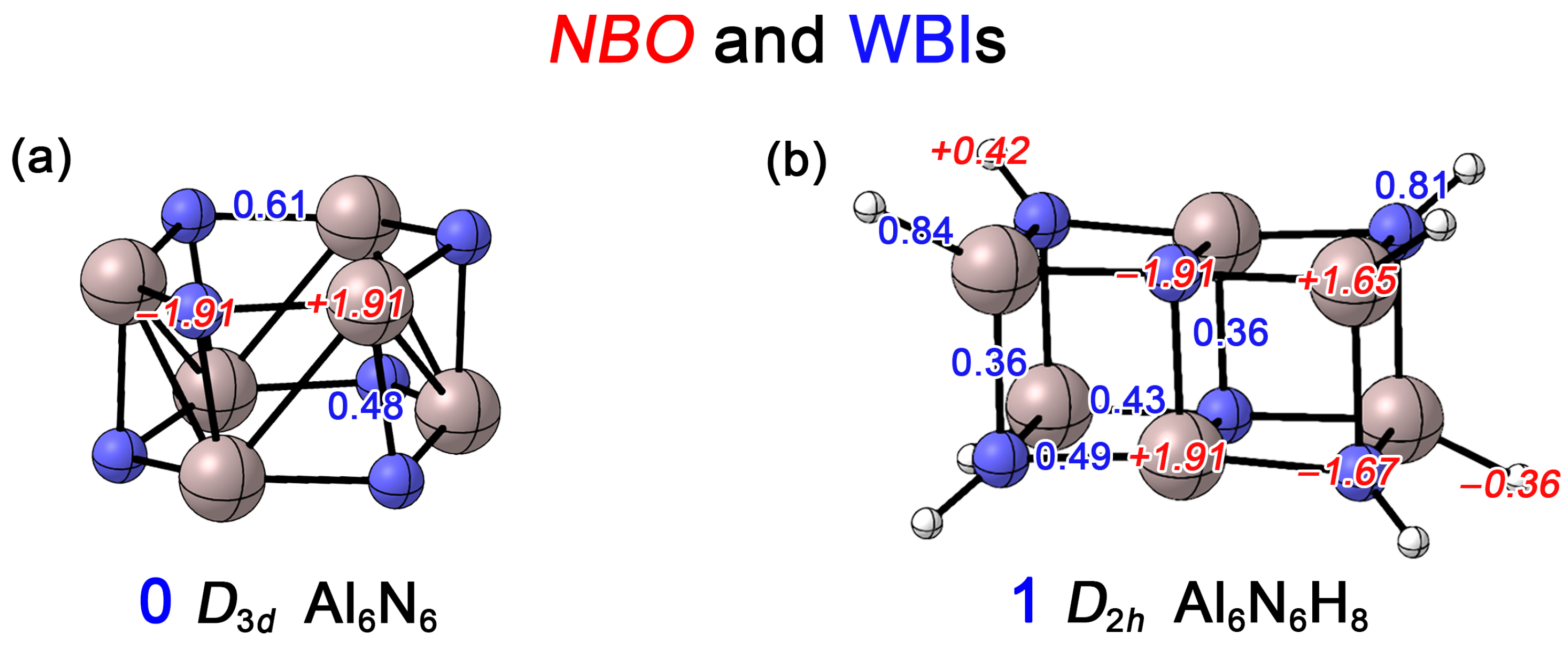

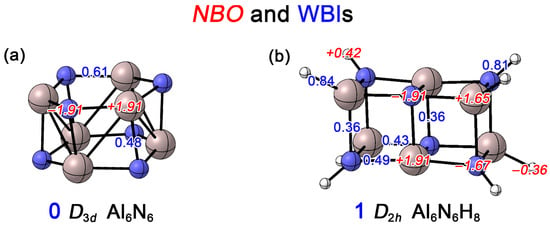

In this work, we first conducted Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analyses to determine the Wiberg bond indices (WBIs) and NBO charges for the Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) clusters. As shown in Figure 5a, the WBI for the Al–N bonds within the hexagonal rings of 0 is 0.61, while the WBI for the interlayer Al–N bonds connecting the upper and lower rings is 0.48. Both values are significantly less than one, which is primarily attributed to the substantial electronegativity difference between Al and N, leading to obvious charge transfer. Each N atom carries a charge of −1.91 |e|, whereas each Al atom carries +1.91 |e|. This indicates that the Al–N bonds exhibit not only a covalent character but also a considerable ionic character. In contrast, for 1 (Figure 5b), the WBIs for the Al1–N2 and Al5–N4 bonds are 0.49 and 0.43, respectively. All Al–N bonds on the short edges show a WBI of 0.36, consistent with ionic covalent bonds. Compared to cluster 0, all Al–N WBIs show a slight decrease. This is attributed to the transformation of the 4c–2e delocalized bond (primarily dominated by the lone pair on the N atoms) into other 2c–2e bonds upon hydrogenation (see the AdNDP analysis below). The N–H and Al–H bonds exhibit WBIs of 0.81 and 0.84, respectively, which are typical for single bonds. Due to the lower electronegativity of Al compared to H, significant charge transfer occurs in the Al–H bonds, where the vertex Al atoms carry a charge of +1.65 |e|, while the bonded H atoms become negatively charged. Similarly, because N is more electronegative than H, the vertex N atoms carry −1.67 |e|. For the Al and N atoms located at the centers of the long edges, the charges are +1.91 |e| and −1.91 |e|, respectively, identical to those in Al6N6 (0). Overall, as shown in Figure S2, a comparison of the electrostatic potential (ESP) maps of the Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) clusters reveals that Al6N6H8 (1) exhibits a narrower ESP distribution. This indicates that the introduction of hydrogen leads to a more homogeneous charge distribution within the cluster.

Figure 5.

Calculated Wiberg bond indices (WBIs, blue font) and natural atomic charges (in |e|, red font) of (a) Al6N6 (0) and (b) Al6N6H8 (1) at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level.

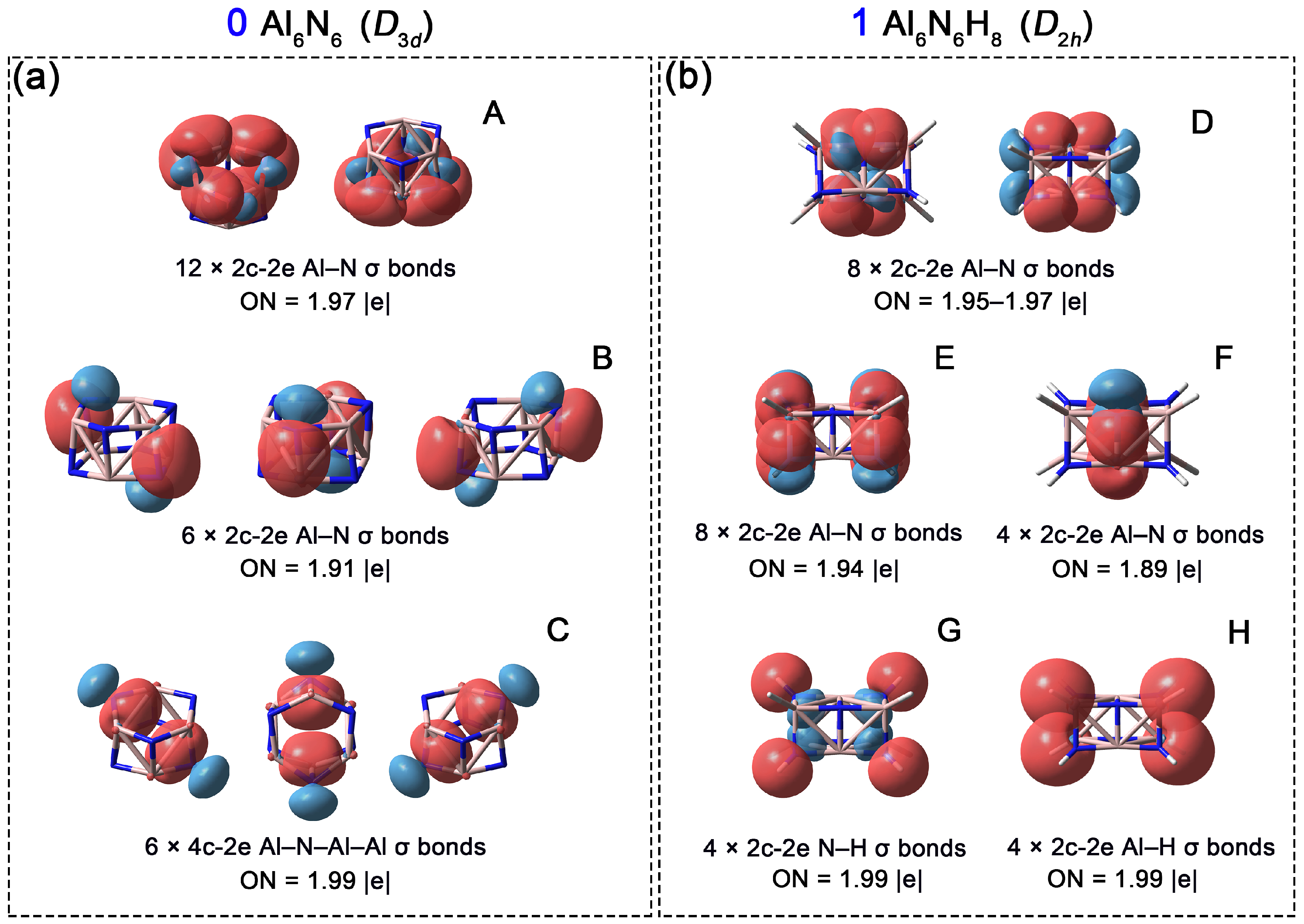

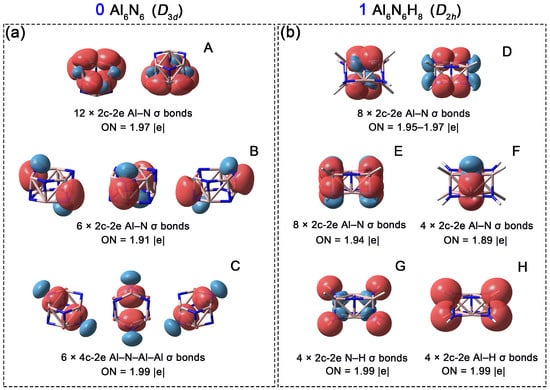

Subsequently, to compare chemical bonding in 0 and 1, Adaptive Natural Density Partitioning (AdNDP) analyses were performed. As shown in Figure 6a, the Al6N6 cluster (0) possesses 24 pairs of valence electrons. The analysis reveals twelve 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds along the six edges of each hexagon with occupation numbers (ONs) of 1.97 |e| (orbital A). Additionally, six 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds (orbital B, ON = 1.91 ∣e∣) connect the two layered hexagons. The remaining six pairs of valence electrons correspond to 4c-2e delocalized σ bonds (orbital C, ON = 1.99 ∣e∣), each involving one N atom and three Al atoms. An alternative interpretation of orbital C is to view it as six lone pairs on the nitrogen atoms, with an ON of 1.84 |e| (Figure S1). Concurrently, the ONs of the Al–N 2c-2e bonds decrease to 1.94 and 1.88 |e|, respectively. This scheme further explain that the primary contribution to the 4c-2e bond originates from N lone pairs. After the addition of eight hydrogen atoms, the system gains eight electrons (one from each H atom), resulting in a total of 28 valence electron pairs for Al6N6H8 (1). As shown in Figure 6b, the AdNDP scheme identifies eight 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds along the long edges of the cuboid (orbital D, ON = 1.95–1.97 ∣e∣). Another eight 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds are located on the short edges (orbital E, ON = 1.94 ∣e∣). In contrast to 0, four additional Al–N σ bonds are observed in the central region of the cuboid in 1 (orbital F, ON = 1.89 ∣e∣). Overall, 1 features two more Al–N bonds than 0. The formation of these new Al–N σ bonds is attributed to the introduction of eight hydrogen atoms at the vertices of 0: the repulsive forces induced by hydrogenation elongate the original double-layered hexagonal structure, causing the Al and N atoms along the central diagonal to approach each other passively, thereby promoting the formation of these new Al–N bonds. The remaining eight pairs of valence electrons correspond to four Al–H bonds and four N–H bonds (2c-2e each).

Figure 6.

Chemical bonding patterns of Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) according to the AdNDP analysis. Occupation numbers (ONs) are denoted. (a) (A) Twelve 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds along the six edges of each hexagon; (B) Six 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds connect the two layered hexagons; (C) Six 4c-2e Al–N–Al–Al delocalized σ bonds; (b) (D) Eight 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds along the long edges of the cuboid; (E) Eight 2c-2e Al–N σ bonds are located on the short edges; (F) Four Al–N σ bonds in the central region of the cuboid; (G) Four N–H σ bonds. (H) Four Al–H σ bonds.

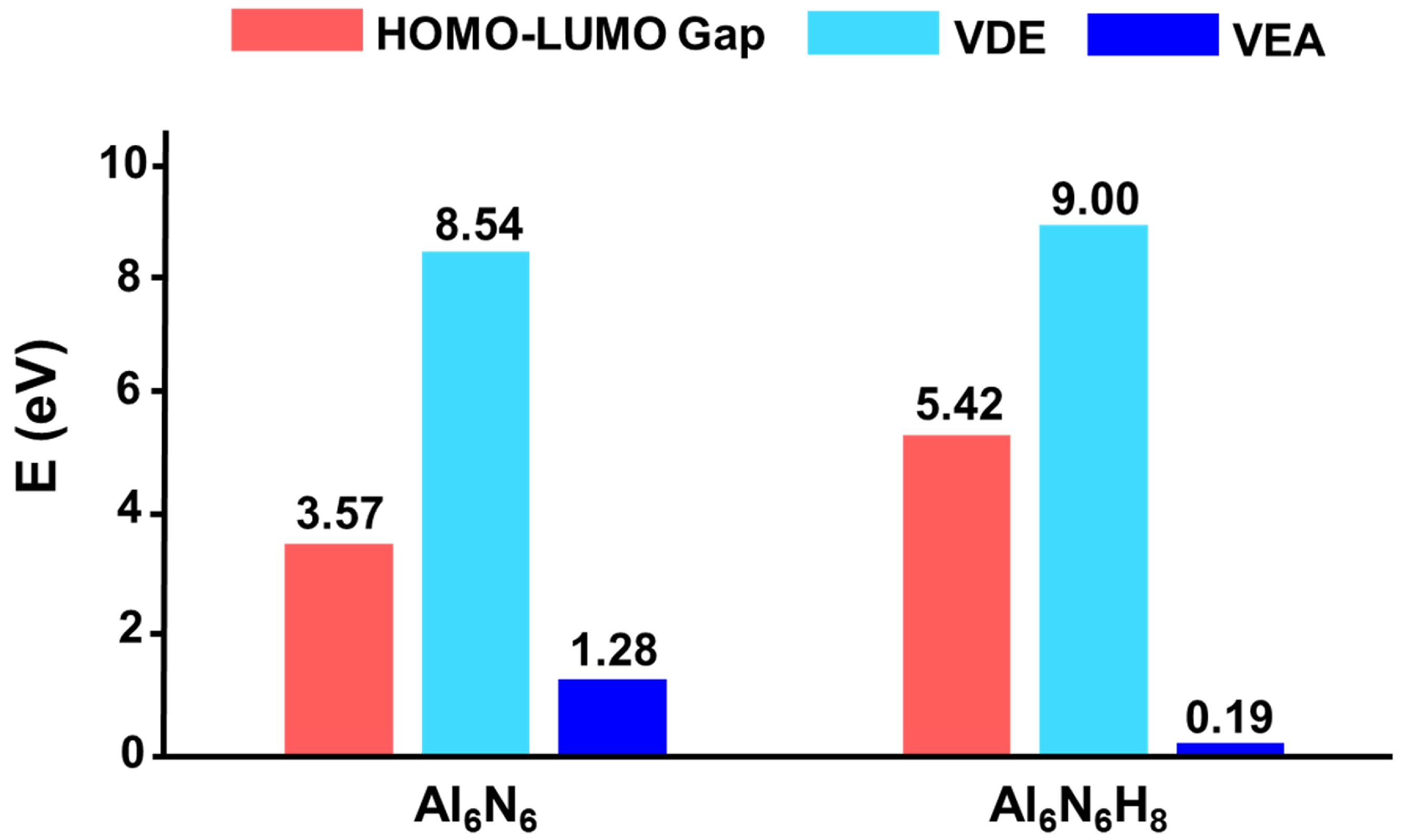

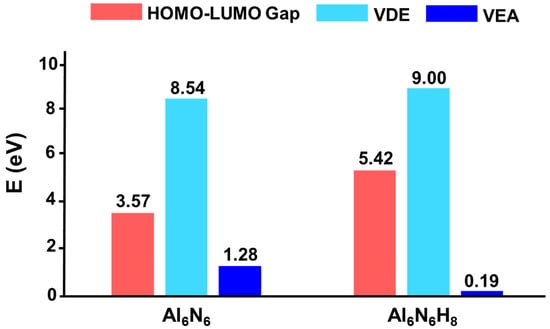

The HOMO–LUMO gap serves as a critical indicator of a cluster’s electronic stability, revealing its propensity to participate in chemical reactions. Generally, a larger HOMO–LUMO gap correlates with higher chemical stability. As shown in Figure 7, the HOMO–LUMO gap of Al6N6 (0) is 3.57 eV. Interestingly, hydrogenation leads to a significant enhancement in electronic stability, with the gap increasing to 5.42 eV for Al6N6H8 (1), which is 1.85 eV higher than that of 0. This indicates that hydrogen incorporation effectively modulates the electronic structure, endowing 1 with considerably improved electronic stability. Furthermore, the vertical detachment energy (VDE) and vertical electron affinity (VEA) of both clusters were calculated at the OVGF/def2-TZVPP level. For a neutral cluster, a higher VDE value reflects greater resistance to electron loss, while a lower VEA value suggests a reduced tendency to accept an additional electron. The computed VDE of 1 is 9.00 eV, which is higher than that of 0 (8.54 eV), while its VEA is 0.19 eV, which is substantially lower than the 1.28 eV of 0. These results indicate that hydrogenation renders cluster 1 more resistant to both electron loss and electron capture, confirming that its electronic structure is more robust than that of its precursor.

Figure 7.

Comparison of HOMO–LUMO gaps (in eV) between Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level.

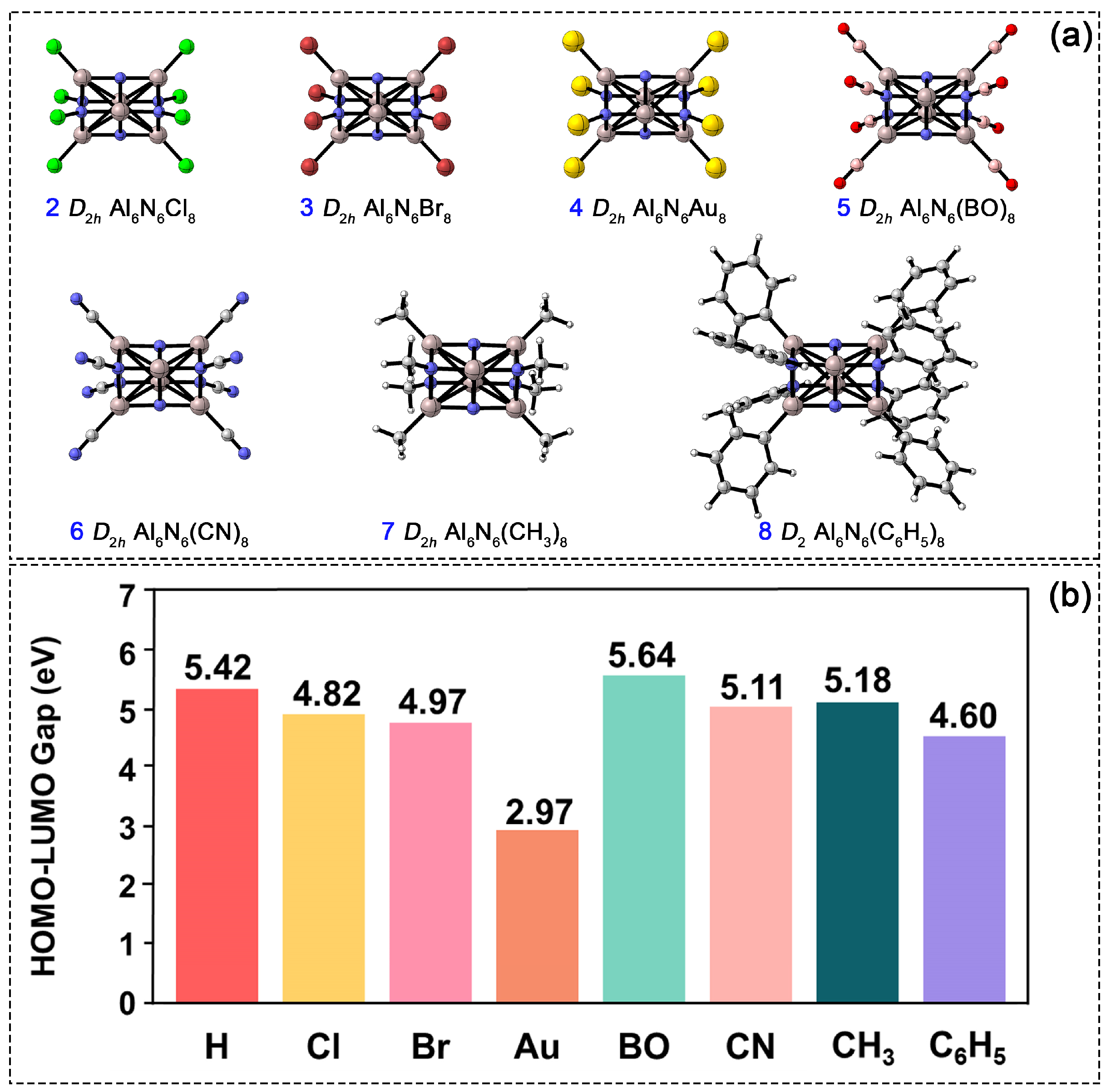

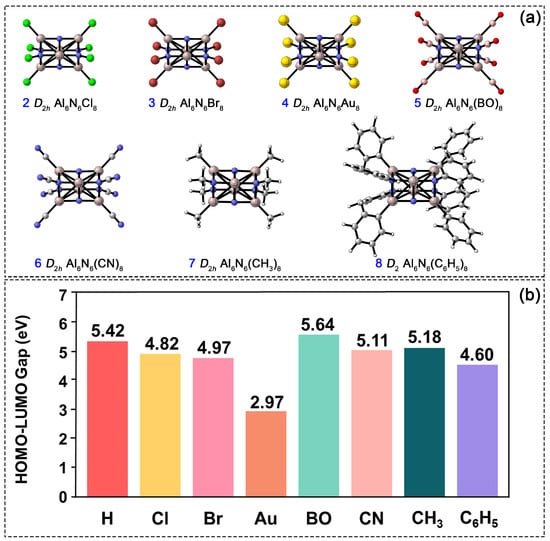

2.4. Functionalization Regulation

In the Al6N6H8 (1) cluster, the hydrogen atom’s positions serve as substitutable sites, enabling the modulation of the cluster’s structure and properties. To investigate the influence of diverse substituents on electronic stability, we systematically replaced all hydrogen atoms with seven different species, as shown in Figure 8a. The substituents strategically selected in this work cover a diverse range of electronic and steric properties, including halogens (Cl and Br) as electronegative elements with strong electron-withdrawing properties, Au as a transition metal atom with potential catalytic applications, boronyl (BO) [27] as an emerging novel ligand with prominent electron-withdrawing characteristics, cyano (CN) and methyl (CH3) as typical common functional groups in organic chemistry, and phenyl (C6H5) as a sterically bulky aromatic group for investigating steric hindrance effects. The following discussion focuses on these fully octa-substituted derivatives. Computational results indicate that at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level, structures 2–7 retain D2h symmetry and are confirmed by frequency calculations to possess no imaginary frequencies, with each corresponding to a true minimum on the potential energy surface. In contrast, when optimized under D2h symmetry constraints, structure 8 exhibits an imaginary frequency, primarily due to the steric hindrance of the phenyl substituent. After relaxation along the imaginary vibrational mode, the structure stabilizes into a lower D2 symmetry. The corresponding atomic displacements for imaginary frequency vibrational modes under D2h symmetry are provided in Figure S4. The bond lengths of Al1–N2, Al1–N6, N4–Al5, and Al2–N5 in structures 2–8 range from 1.84 to 1.86 Å, from 1.97 to 2.00 Å, from 1.87 to 1.89 Å, and from 1.91 to 1.93 Å, respectively. These values closely match the corresponding bond lengths in 1, indicating that the cuboid Al6N6 core’s framework remains stable upon complete hydrogen substitution. However, the electronic properties of 2–8 differ noticeably from those of the parent cluster (1). As shown in Figure 8b, all atom-substituted clusters (2–4) exhibit a narrower HOMO–LUMO gap compared to 1. Among them, the Au-substituted structure shows the smallest gap, suggesting its higher chemical reactivity. In contrast, substitution with the BO group results in the widest HOMO–LUMO gap: 0.22 eV larger than that of 1 and exceeding those of the organic-group-substituted clusters (CN, CH3, and C6H5) by 0.53, 0.46, and 1.04 eV, respectively. Thus, the BO-substituted derivative possesses the most stable electronic structure among all substituted systems studied.

Figure 8.

(a) PBE0/def2-TZVPP-optimized structures of Al6N6E8 (E = Cl, Br, Au, BO, CN, CH3, C6H5, 2–8). (b) Comparison of the HOMO-LUMO gap among 2–8.

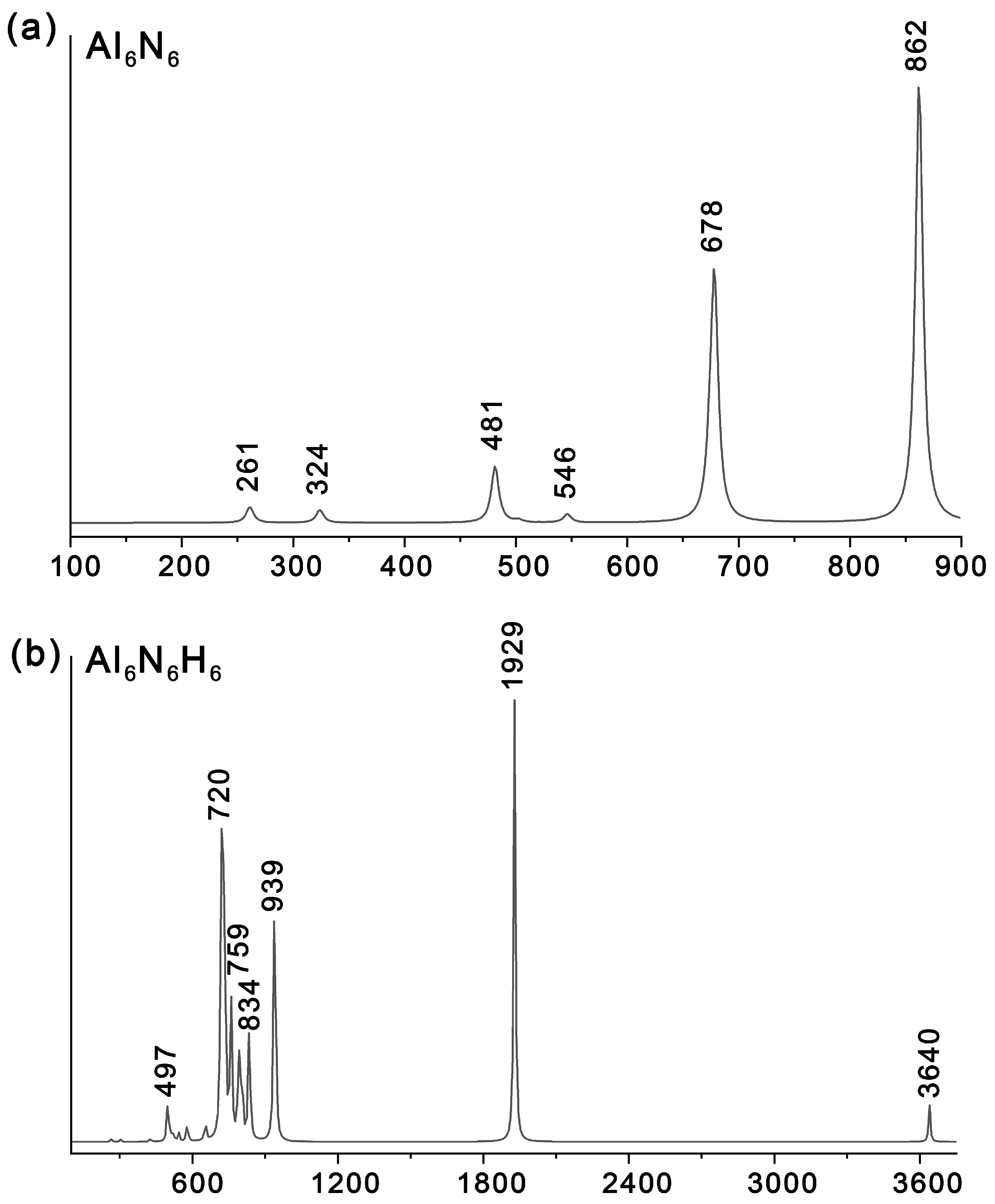

2.5. Simulated IR Spectrums

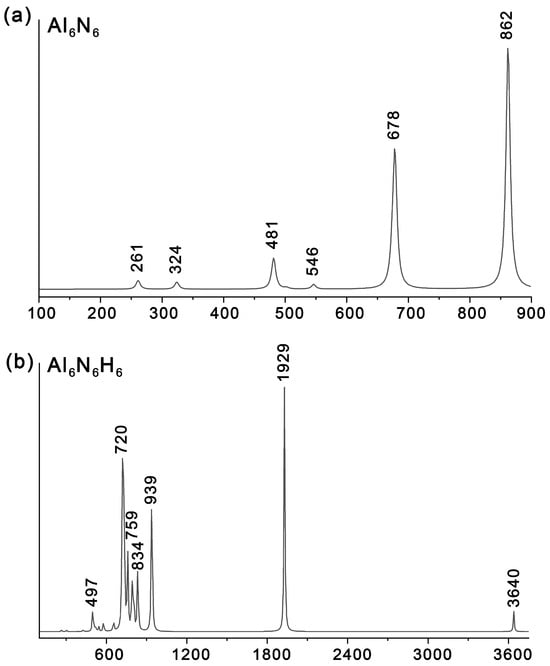

To facilitate future experimental characterization, we simulated the infrared (IR) spectra of Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) (Figure 9) at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level and compared them with those of the precursor structure, Al6N6 (0). As shown in Table 1, the key information on the main vibrational peaks for 0 and 1 is detailed, covering peak positions, activity intensities, vibrational mode types, and specific vibrational assignment. For 1, the most intense IR absorption peak is observed at 1929 cm−1, which is primarily attributed to the stretching vibration of the Al–H bonds at the vertices. A weak peak at 497 cm−1 is mainly ascribed to the bending vibration of Al–H bonds. The weak feature at 3640 cm−1 corresponds to N–H stretching vibrations, while the signals spanning 759–834 cm−1 correspond to N–H bending modes. Notably, the second most intense peak is located at 720 cm−1, corresponding to Al–N bending vibrations, and the third most intense peak at 939 cm−1 is assigned to Al–N stretching vibrations. In contrast, the IR spectrum of 0 exhibits characteristic Al–N bending and stretching vibrations at 678 cm−1 and 862 cm−1, respectively. And the corresponding atomic displacement vectors of the IR vibrational mode of both Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) are shown in Table S2. In addition, it should be noted that introducing eight hydrogen atoms induces a distinct blue shift in these characteristic Al–N stretching and bending vibrational modes.

Figure 9.

Simulated IR spectra of (a) Al6N6 and (b) Al6N6H8 (1) at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level.

Table 1.

All peak positions are theoretical values calculated at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level.

3. Methods

The geometry optimization and harmonic vibrational frequency analyses of the pristine honeycomb-like hexagonal prism Al6N6 cluster and the newly designed Al6N6H8 cluster were performed at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP [28,29] level. The potential energy surface (PES) calculations for Al6N6H8 were carried out using the Coalescence-Kick (CK) [30,31] and Basin-Hopping algorithms [32]; both singlet and triplet states were considered, and the initial structures were first generated and optimized at the PBE/DZVP level. Approximately 3000 stationary points were probed for Al6N6H8. Twenty low-energy isomers were then reoptimized at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level. Among these, the relative single-point energies of the top five structures were further evaluated at the CCSD(T)/def2-TZVPP level [33,34] with zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level [abbreviated as CCSD(T) + ZPEPBE0], while the PBE0 functional was used for subsequent electronic structure analyses. Chemical bonding was analyzed using Adaptive Natural Density Partitioning (AdNDP) [35] at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level. Dynamic stability was assessed via Born–Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations at selected temperatures using the CP2K package [36] at the PBE/DZVP level. Vertical detachment energies (VDEs) and vertical electron affinities (VEAs) were calculated using the Outer-Valence Green’s Function (OVGF) method [37]. Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis was performed using the NBO 6.0 program [38]. AdNDP analysis used Multiwfn 3.8 [39]. The Basin-Hopping algorithm was coded in the TGMin 2.0 program [40]. The CCSD(T) calculations were carried out with MolPro 2012.1 [41], and all other calculations were performed using Gaussian 16 (A.03) [42]. The results were visualized with GaussView 6.1 and CYLview 2.0.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the bilayer honeycomb-like hexagonal prism of Al6N6 (0) can be reconstructed into a thermodynamically and dynamically stable cuboid structure, Al6N6H8 (1), through a “selective hydrogenation” strategy. In cluster 1, the Al–N, Al–H, and N–H bonds are identified as covalent single bonds with an ionic character resulting from the electronegativity differences among Al, N, and H. The HOMO–LUMO gap of 1 increase by 1.85 eV compared to that of 0, indicating a significant enhancement in electronic stability upon hydrogenation. Substituting the eight hydrogen atoms in 1 with various atoms or groups preserves the cuboidal Al6N6 core framework while enabling notable modulation of its electronic properties. Furthermore, the simulated infrared spectrum reveals an overall blue shift in the Al–N vibrational modes after hydrogenation, providing a theoretical reference for future experimental characterization. In summary, selective hydrogenation serves as an effective strategy for tuning the structure and physicochemical properties of AlN clusters, offering a feasible pathway for the design of novel clusters.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31030495/s1, Table S1: Cartesian coordinates for optimized global-minimum (GM) structures of Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1) clusters at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level; Table S2: Simulated infrared (IR) vibrational mode assignment and atomic displacement maps of Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1). This table summarizes the calculated IR vibrational peaks, activity intensities, mode types, and corresponding atomic displacement vectors for both the Al6N6 (0) and Al6N6H8 (1), at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level. Figure S1: A structural schematic diagram illustrating the stepwise hydrogenation of Al6N6 (0) at different sites, with energies given in kcal mol−1 at the PBE0/def2-TZVPP level. Figure S2: Electrostatic potential (ESP) maps of (A) Al6N6 (0) and (B) Al6N6H8 (1). Figure S3: An alternative chemical bonding pattern of Al6N6 (0) according to the AdNDP analysis. Occupation numbers (ONs) are denoted. Figure S4: Optimized equilibrium structures of the D2 (left) and D2h (right) isomers of Al6N6(C6H5)8, with the number of imaginary vibrational frequencies (NImag) indicated. Atomic displacement vectors corresponding to the imaginary vibrational modes of the D2h isomer, with imaginary frequencies of (a) 43.40i, (b) 30.88i, (c) 28.27i, (d) 20.30i, and (e) 10.32i cm−1, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.-F.L.; methodology, P.-F.L. and Y.Y.; validation, P.-F.L. and S.-J.G.; investigation, P.-F.L. and Y.Y.; data curation, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, P.-F.L. and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, P.-F.L. and S.-J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Scientific and Technological Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (2024L465) and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202303021212289).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.D.; Jiang, W.; Norton, M.G.; Hipps, K.W. Morphology and orientation of nanocrystalline AlN thin films. Thin Solid Films 1994, 251, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, G.A.; Tanzilli, R.A.; Pohl, R.O.; Vandersande, J.W. The intrinsic thermal conductivity of AlN. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1987, 48, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, F.; Fiorentini, V.; Vanderbilt, D. Spontaneous polarization and piezoelectric constants of III–V nitrides. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, R10024–R10027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Lu, H.; He, Q.; Gu, S.; Zhang, D.; Yin, H.; et al. Preparation of high thermal conductivity aluminium nitride ceramics with low oxygen impurity for power semiconductors. Elec. Mat. Appl. 2024, 1, e12012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.K.; Moore, D.C.; Francis, A.M.; Kupernik, J.; Kennedy, W.J.; Glavin, N.R.; Olsson, R.H., III; Jariwala, D. Materials for high-temperature digital electronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 790–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, A.; Parlinski, K.; Wdowik, U.D. Ab initio calculation of structural phase transitions in AlN crystal. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 2006, 74, 104116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costales, A.; Blanco, M.A.; Francisco, E.; Pandey, R.; Martín Pendás, A. Evolution of the Properties of AlnNn Clusters with Size. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 24352–24360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wu, H.S.; Jin, Z.H. First-principles investigation of structure and stability of AlnNm clusters. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2005, 103, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalam, A.K.; Blanco, M.A.; Pandey, R. Theoretical Study of AlnNn, GanNn, and InnNn (n = 4, 5, 6) Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Patzer, A.B.C.; Sedlmayr, E.; Steinke, T.; Sülzle, D. A density functional study of small (AlN)x clusters: Structures, energies, and frequencies. Chem. Phys. 2001, 271, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costaies, A.; Blanco, M.; Francisco, E.; Pendas, A.M.; Pandey, R. First principles study of neutral and anionic. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 4092–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Q.E. Structure and stability of (AlN)n clusters. Sci. Chin. Ser. B 2000, 43, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Han, C.; Yang, B.; Xu, B.; Liu, D. Theoretical Study on Growth Mechanism of AlnNn (n = 2–9) Clusters. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 94, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukhovitski, B.I.; Sharipov, A.S.; Starik, A.M. Theoretical study of physical and thermodynamic properties of AlnNm clusters. Eur. Phys. J. D 2016, 70, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.S.; Zhang, F.Q.; Xu, X.H.; Zhang, C.J.; Jiao, H. Geometric and energetic aspects of aluminum nitride cages. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Qian, Z.; Du, W.; Lu, Z.; Li, H.; Ahuja, R.; Liu, X. Structural evolution of AlN nanoclusters and the elemental chemisorption characteristics: Atomistic insight. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yuan, H.; Kuang, A.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G.; Chen, H. High-capacity hydrogen storage in Li-decorated (AlN)n (n = 12, 24, 36) nanocages. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 3780–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Z. Structure, electronic and magnetic properties of the Al12N12 clusters encapsulated with transition metals. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2024, 38, 2450413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allangawi, A.; Shanaah, H.H.; Mahmood, T.; Ayub, K. Investigation of the cyclo [12] carbon nanoring and respective analogues (Al6N6 and B6N6) as support for the single atom catalysis of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023, 162, 107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Aizez, N.; Ma, J.; Yaermaimaiti, G.; Kadir, A.; Wang, X.; An, H.; Abulimiti, B.; Xiang, M. Investigation of structural, IR spectral, thermodynamics and excitation property alterations in (AlN)12 cluster under external electric fields. Eur. Phys. J. D 2024, 78, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, N.; Gordon, M.S. Stabilities and energetics of inorganic benzene isomers: Prismanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 11407–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, R.D.; Jaffrey, K.L. Aluminum-Nitrogen Multiple Bonds in Small AlNH Molecules: Structures and Vibrational Frequencies of AlNH2, AlNH3, and AlNH4. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 8930–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, R.D.; Schaefer, H.F. Structure, Spectra, and Reaction Energies of the Aluminum−Nitrogen (HAl−NH)2 and (H2Al−NH2)2 Rings and the (HAl−NH)4 Cluster. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 2291–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, C.; Jin, Z. Studies on the structure, infrared spectrum and chemical thermodynamics of (HAlNH)n (n = 1~6) clusters. Acta Chim. Sinica 2000, 58, 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Q. Structures and stability of (HAlNHn (n = 1–15)). Chin. Sci. Bull. 2001, 46, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, P. Additive covalent radii for single-, double-, and triple-bonded molecules and tetrahedrally bonded crystals: A summary. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 2326–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.J.; Chen, Q.; Bai, H.; Li, S.D.; Wang, L.S. Boronyl Chemistry: The BO group as a new ligand in gas-phase clusters and synthetic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M. Stochastic search for isomers on a quantum mechanical surface. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averkiev, B. Geometry and Electronic Structure of Doped Clusters via the Coalescence Kick Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wales, D.J.; Doye, J.P. Global optimization by basin-hopping and the lowest energy structures of Lennard-Jones clusters containing up to 110 atoms. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, G.D., III; Bartlett, R.J. A full coupled-cluster singles and doubles model: The inclusion of disconnected triples. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76, 1910–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noga, J.; Bartlett, R.J. The full CCSDT model for molecular electronic structure. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 7041–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, D.Y.; Boldyrev, A.I. Developing paradigms of chemical bonding: Adaptive natural density partitioning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 5207–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, T.D.; Iannuzzi, M.; Del Ben, M.; Rybkin, V.V.; Seewald, P.; Stein, F.; Laino, T.; Khaliullin, R.Z.; Schütt, O.; Schiffmann, F.; et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package-Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 194103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, J.V.; Zakrzewski, V.G.; Dolgounircheva, O. Conceptual Perspectives in Quantum Chemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, J. TGMin: A global-minimum structure search program based on a constrained basin-hopping algorithm. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 3407–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.J.; Knowles, P.J.; Knizia, G.; Manby, F.R.; Schütz, M. Molpro: A general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16 (Revision A.03); Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.