Abstract

To address the issues of slow curing rate, post-curing reactions, and suboptimal mechanical properties in the carboxyl-terminated polybutadiene (CTPB)/epoxy resin (EP) binder system used for solid propellants, this study optimized the curing system by introducing 593 aliphatic amine compounds containing primary and secondary amine groups as a cure accelerator. It is found that the incorporation of the cure accelerator improved the fracture strength and elongation at break of the CTPB/EP binder system. With the addition of 0.3 wt.% cure accelerator, the tensile fracture strength increased to 0.37 MPa, while the elongation at break reached 655%. Moreover, augmenting the quantity of cure accelerator can substantially elevate the crosslink density and gel fraction of the binder system. When the addition reaches 0.3 wt.%, the crosslink density is 4.3 × 10−4 mol/cm3. Further studies showed that 593 cure accelerator reduced the activation energy of the curing reaction of the CTPB/EP binder system, with higher levels of cure accelerator resulting in lower activation energy. This study established a preparation methodology for a CTPB/EP binder system with high elongation and tensile strength. These findings provide a solid scientific foundation for the application of CTPB-based binder systems in solid propellants.

1. Introduction

Solid propellants are energetic composite materials composed of polymer binder, solid powder oxidizer, powdered metal fuel, and other additional components. This class of materials enables sustained and stable combustion, generating copious amounts of high-temperature and high-pressure gas, which in turn provides continuous thrust for propulsion systems [1]. The performance of solid propellant directly affects the operational effectiveness of rockets and missiles [2].

Carboxyl-terminated polybutadiene (CTPB) is predominantly synthesized via anionic or radical polymerization of 1,3-butadiene. It has been extensively applied as a polymer binder in solid rocket propellants due to its excellent adhesion, appropriate viscosity, mild curing reaction, and low heat release during curing [3,4]. Its curing reaction takes place on the terminal carboxyl group that can react with the curing agents containing epoxy aziridinium, alcohols, or isocyanate groups [5,6,7]. The reaction forms a curing network structure that can improve the casting molding process and mechanical properties of the cured binder and composite system [8,9]. Therefore, it is also a potential method to increase the solid content of the propellants and enhance the safety of preparation processes.

CTPB tends to absorb moisture, and the oxidizer is prone to produce CO2 and other small molecule by-products, which affects the density and uniformity of the cured propellant [10,11]. The curing system of CTPB and epoxy resin (EP) curing agents can form an ester bond network. The cross-linked products exhibit excellent mechanical properties and strength. As a result, epoxy resin curing agents are extensively utilized in CTPB binder system [12,13,14]. However, during the curing process of the EP and CTPB adhesive, the curing rate is relatively slow, resulting in a prolonged curing time. Additionally, the elongation at break of the solid propellant after curing is relatively low [15,16].

The carboxyl–epoxy reaction, although theoretically capable of proceeding without a cure accelerator, generally demands high temperatures to achieve adequate completion [17]. During the manufacturing process of solid propellants, the typical curing temperature range is 50–70 °C [18,19]. Surpassing this temperature threshold may induce thermal stress within the material. The energetic components in the propellant, including RDX (Royal Demolition Explosive) and AP (Ammonium Perchlorate), could encounter substantial safety hazards [20]. Utilizing end-amino terminated polybutadiene, which possesses higher reactivity, as the binder for epoxy resin, although eliminating the need for a cure accelerator, predominantly results in the formation of rigid C–N bonds within the resultant network [21,22]. This can enhance the brittleness of the material. Concurrently, an excessively rapid curing reaction rate can readily cause the viscosity of the mixed paste to escalate too swiftly. The solid fillers then encounter difficulties in achieving uniform dispersion, leading to localized aggregation of fillers and thereby engendering safety hazards [23,24].

To solve this problem, a substance capable of promoting the ring opening of the epoxy bond in EP can be added to facilitate the esterification between EP and the carboxyl group at the end of the CTPB moiety after ring opening. Aliphatic amine compounds, which contain amino groups, are capable of promoting the ring opening of EP under medium and low-temperature conditions. This characteristic makes them highly suitable for such applications and renders them ideal catalysts for the curing reaction between EP and CTPB [25,26,27].

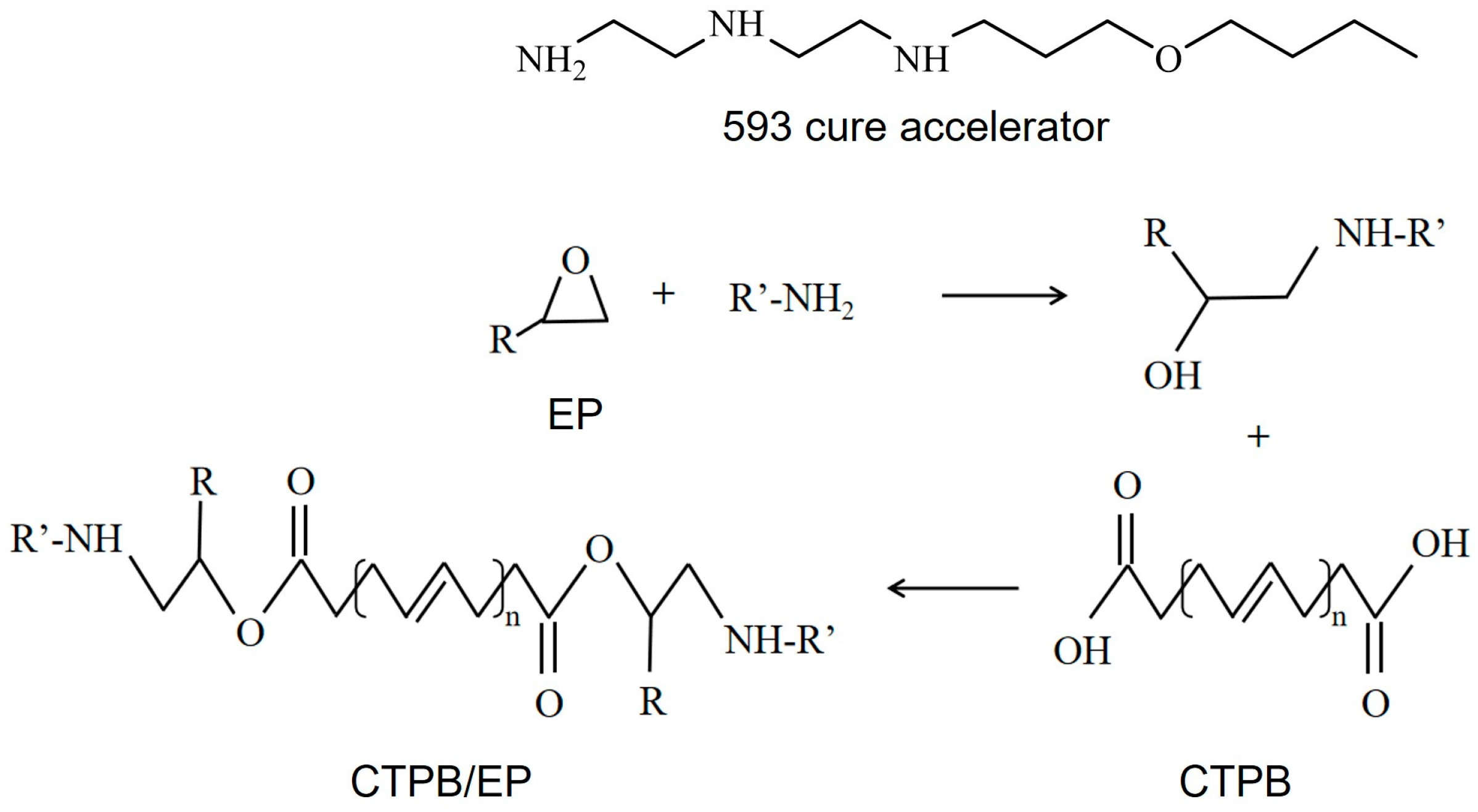

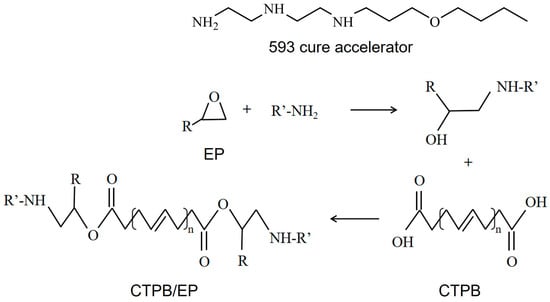

For the CTPB/EP binder system in this article, EP is the curing agent, and dioctyl sebacate (DOS) is the plasticizer. To address the issues of low tensile strength and prolonged curing time in the CTPB/EP binder system, the 593 cure accelerator, which contains amino groups in its molecular structure, was employed in this study. The 593 cure accelerator is an adduct of diethylenetriamine and butyl glycidyl ether, offering advantages such as transparency, low toxicity, and low volatility [28]. The primary and secondary amine groups within this substance can facilitate the ring-opening reaction of the epoxy bonds in EP. Subsequently, the hydroxyl groups produced from the ring-opening reaction can engage in esterification reactions with carboxyl groups, thereby enhancing the curing efficiency and mechanical properties of the system. The cross-linking mechanism of the system and the molecular structure of each component are shown in Figure 1. The optimization of the formulation composition led to enhanced mechanical properties in the CTPB/EP binder system [29,30].

Figure 1.

Cross-linking mechanism of carboxyl-terminated polybutadiene (CTPB)/epoxy resin (EP) binder system and molecular structure of each component.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Infrared Spectroscopy (IR)

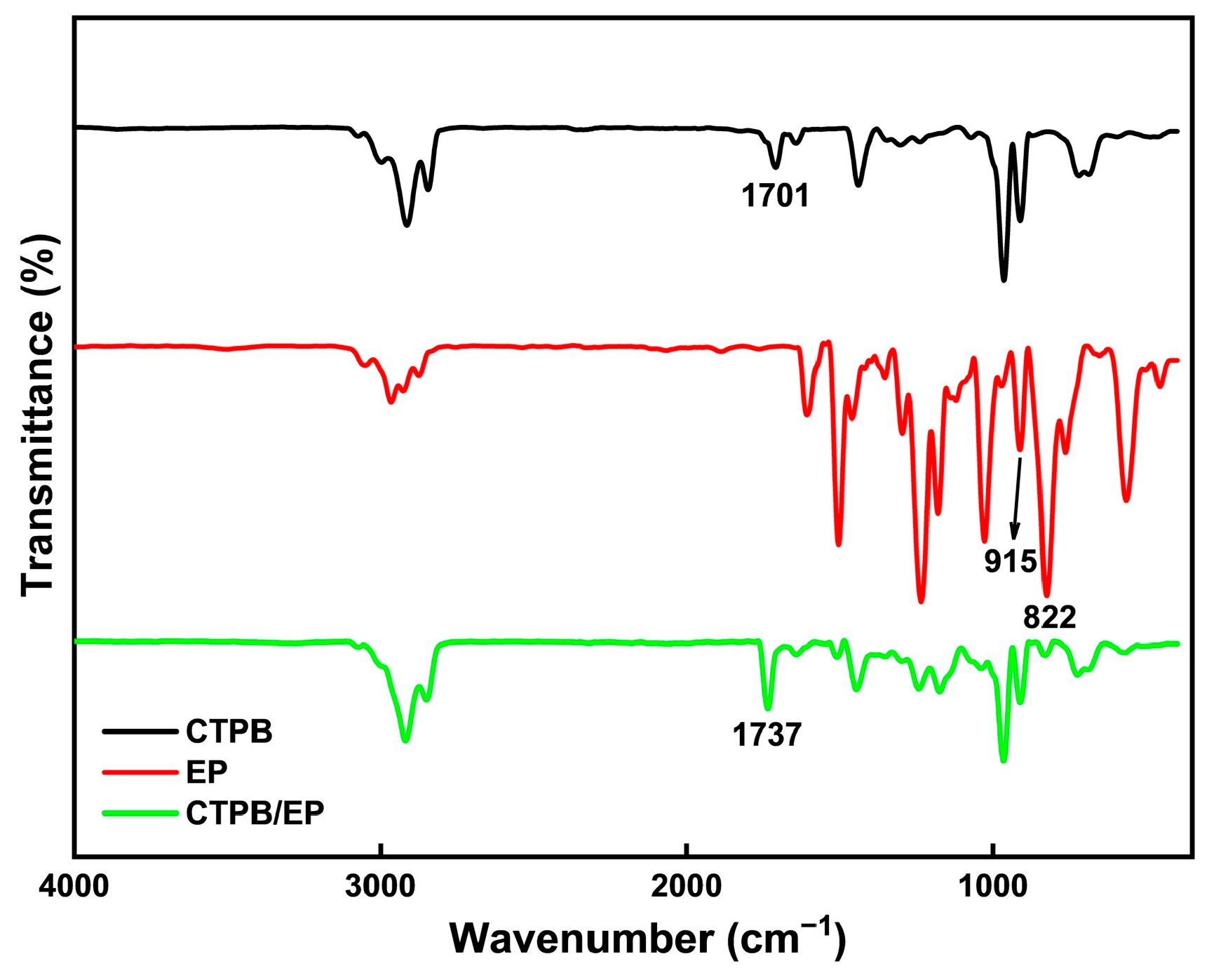

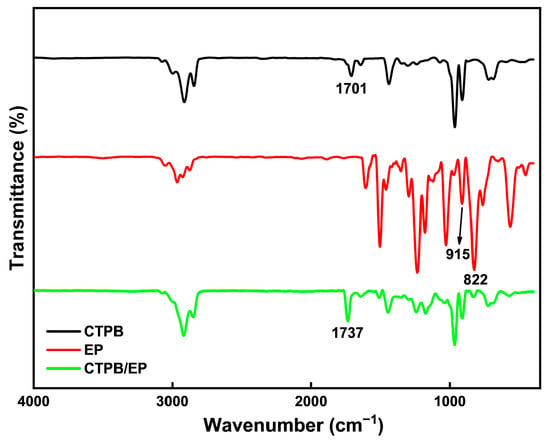

Figure 2 shows the Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of CTPB, EP, and the cured CTPB/EP system with 4% EP content using the 593 cure accelerator. The spectral comparison clearly confirms the chemical reaction between CTPB and EP during curing. The pure EP spectrum displays characteristic epoxy group peaks at 915 cm−1 and 822 cm−1, corresponding to epoxy ring stretching vibrations. These peaks show substantial weakening in the cured product, indicating consumption of epoxy groups through ring-opening reactions. Similarly, the C=O stretching vibration of carboxyl groups in CTPB at 1701 cm−1 decreases significantly after curing, confirming the participation of –COOH groups in the reaction. A new peak appears at 1737 cm−1 in the cured product, characteristic of ester carbonyl groups. This provides direct evidence for ester bond formation between CTPB carboxyl groups and EP epoxy groups.

Figure 2.

Infrared spectroscopy analysis of CTPB, EP, and CTPB/EP.

2.2. Mechanical Properties

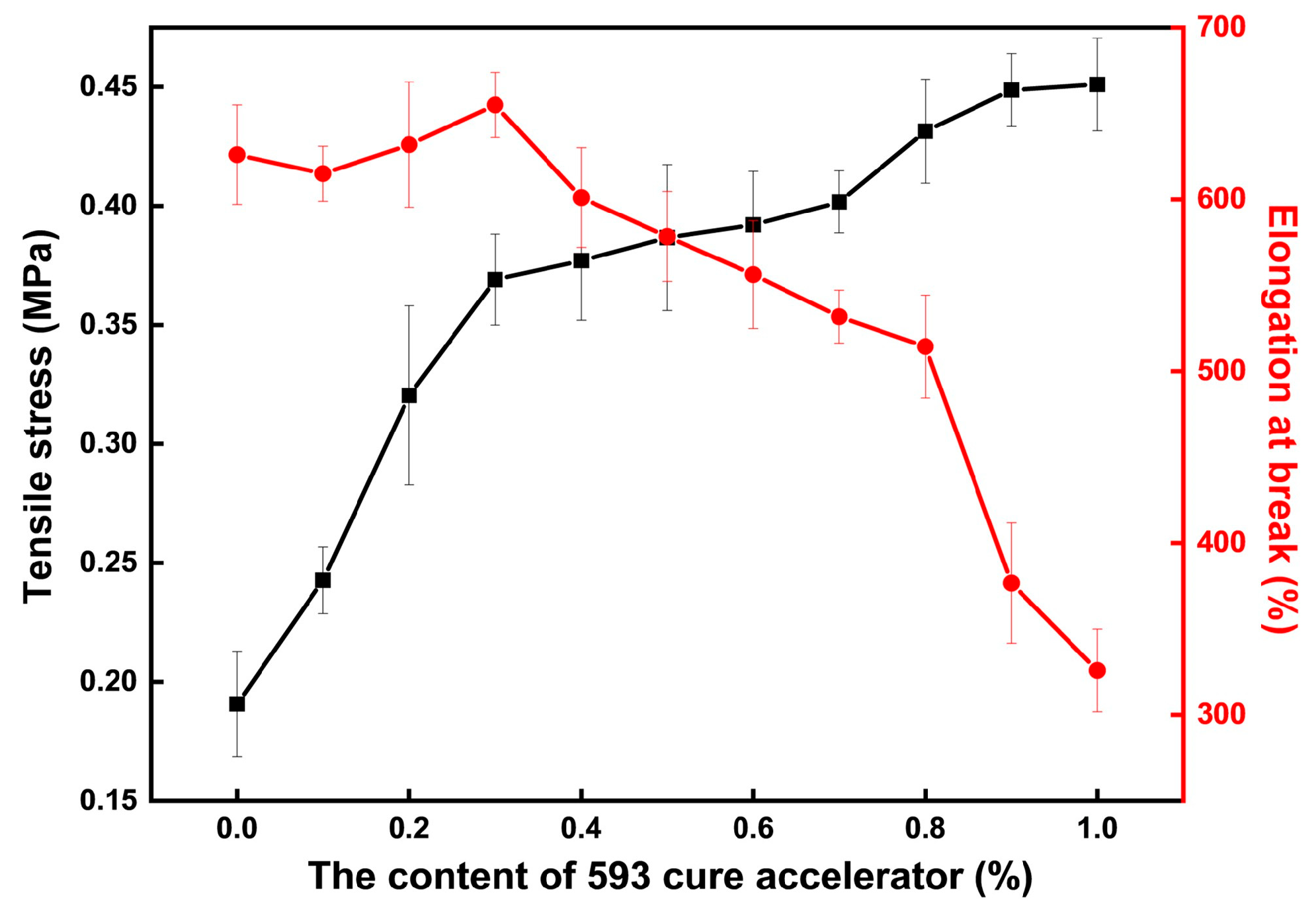

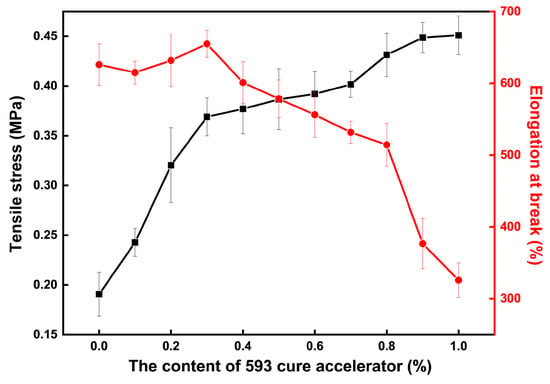

The mechanical properties test results of the CTPB/EP binder system with different amounts of cure accelerator are shown in Figure 3. The adhesive system without the addition of 593 cure accelerator has an elongation at break of 626% and a tensile strength of only 0.19 MPa. As the amount of 593 cure accelerator added increases, the tensile breaking strength of the CTPB/EP binder system gradually increases, while the elongation at break first slightly increases and then rapidly decreases. When an excessive amount of 593 cure accelerator is added, the toughness of the adhesive deteriorates.

Figure 3.

Changes in tensile strength and elongation at break of the CTPB/EP binder system with the increase in 593 cure accelerator content.

When the amount of 593 cure accelerator added is 0.3 wt.%, the tensile breaking strength of the adhesive is 95% higher than that of the original adhesive, reaching 0.37 MPa, while achieving the highest elongation at break of 655%. Moreover, regarding the surface of the samples, the surface of the sample cured with the addition of 0.3 wt.% 593 cure accelerator is smoother than that of the adhesive sample without the addition of 593 cure accelerator.

Based on the above experimental observations, it can be inferred that the amine groups in the 593 cure accelerator can effectively catalyze the ring-opening reaction of the epoxy groups in EP and significantly enhance the reaction efficiency between the epoxy rings and the terminal carboxyl groups of CTPB, thereby promoting the formation of more ester bonds and ultimately creating a polymer network with a higher degree of cross-linking. The increase in crosslink density restricts the mobility of the polymer chains, enhances the material’s resistance to deformation, and thus improves the mechanical strength of the CTPB/EP binder system.

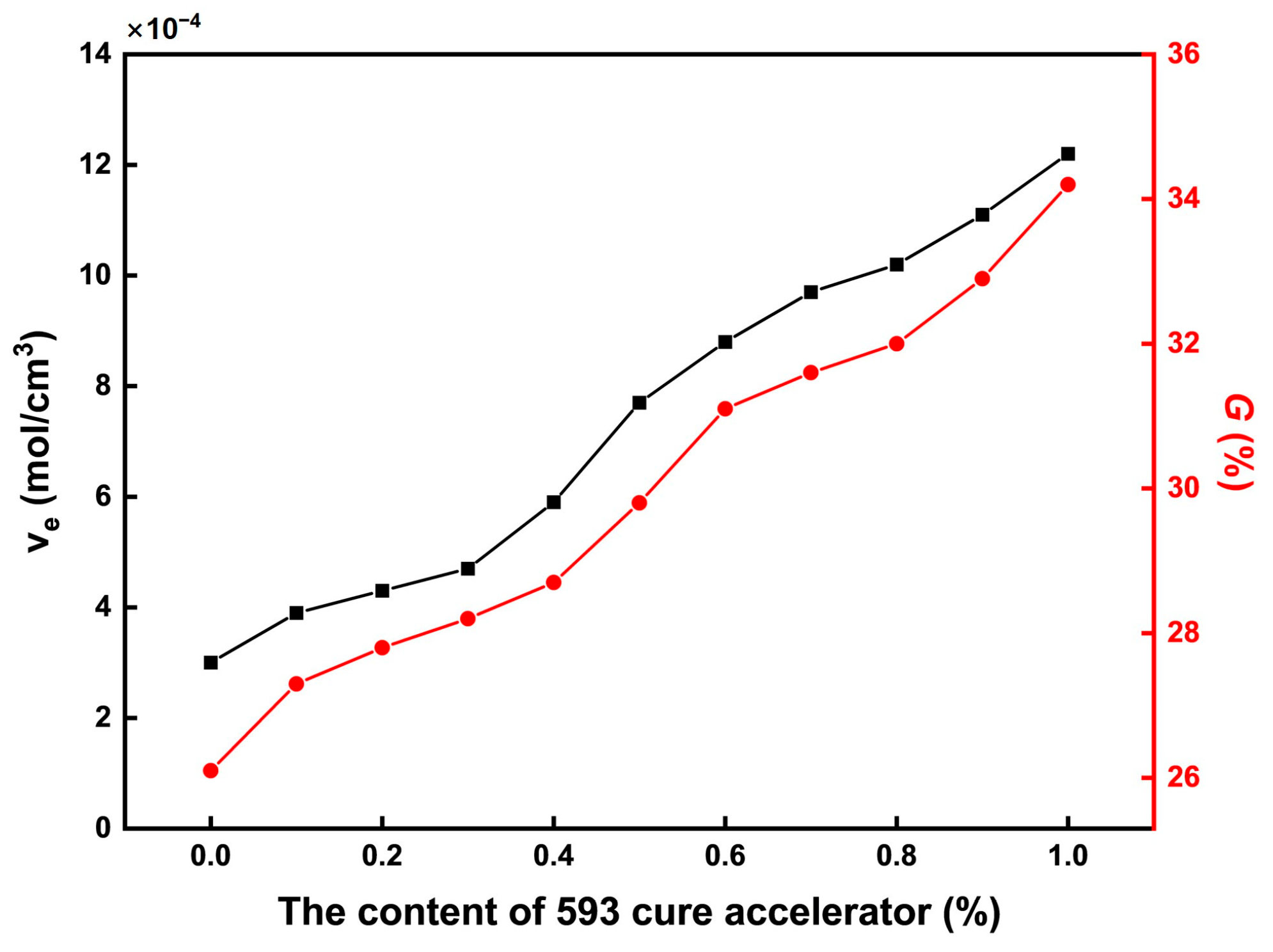

2.3. Crosslink Density

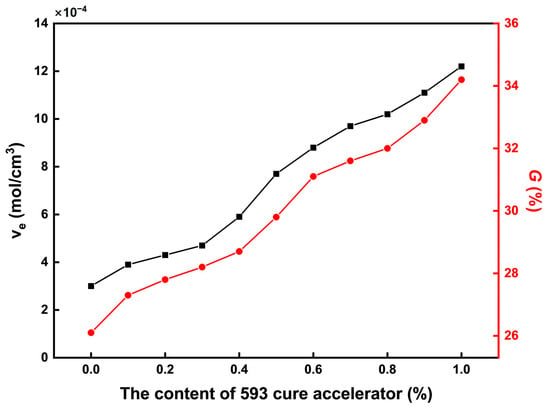

The cross-linking characteristics of the CTPB/EP binder systems were evaluated through crosslink density and gel fraction measurements, as summarized in Figure 4. Both parameters exhibit a clear increasing trend with higher contents of the 593 cure accelerator, indicating enhanced network formation. This trend can be attributed to the catalytic effect of the amine groups in the 593 cure accelerator. These amine groups can promote the ring-opening reaction of the epoxy groups in EP, thereby increasing the number of active sites in the system. The hydroxyl groups generated from the ring opening of EP can then form more ester bonds with the terminal carboxyl groups of CTPB, ultimately achieving an increase in crosslink density. The corresponding rise in gel fraction further confirms the formation of a more complete and robust three-dimensional network. This structural evolution corresponds to the observed increase in tensile breaking strength in the mechanical property tests of Section 2.2: Mechanical Properties.

Figure 4.

Variations in crosslink density and gel fraction of the CTPB/EP binder system with the increase in 593 cure accelerator content. is the crosslink density of the polymer (mol/cm3); is related to the crosslinking network properties of the binder.

2.4. Surface Morphology

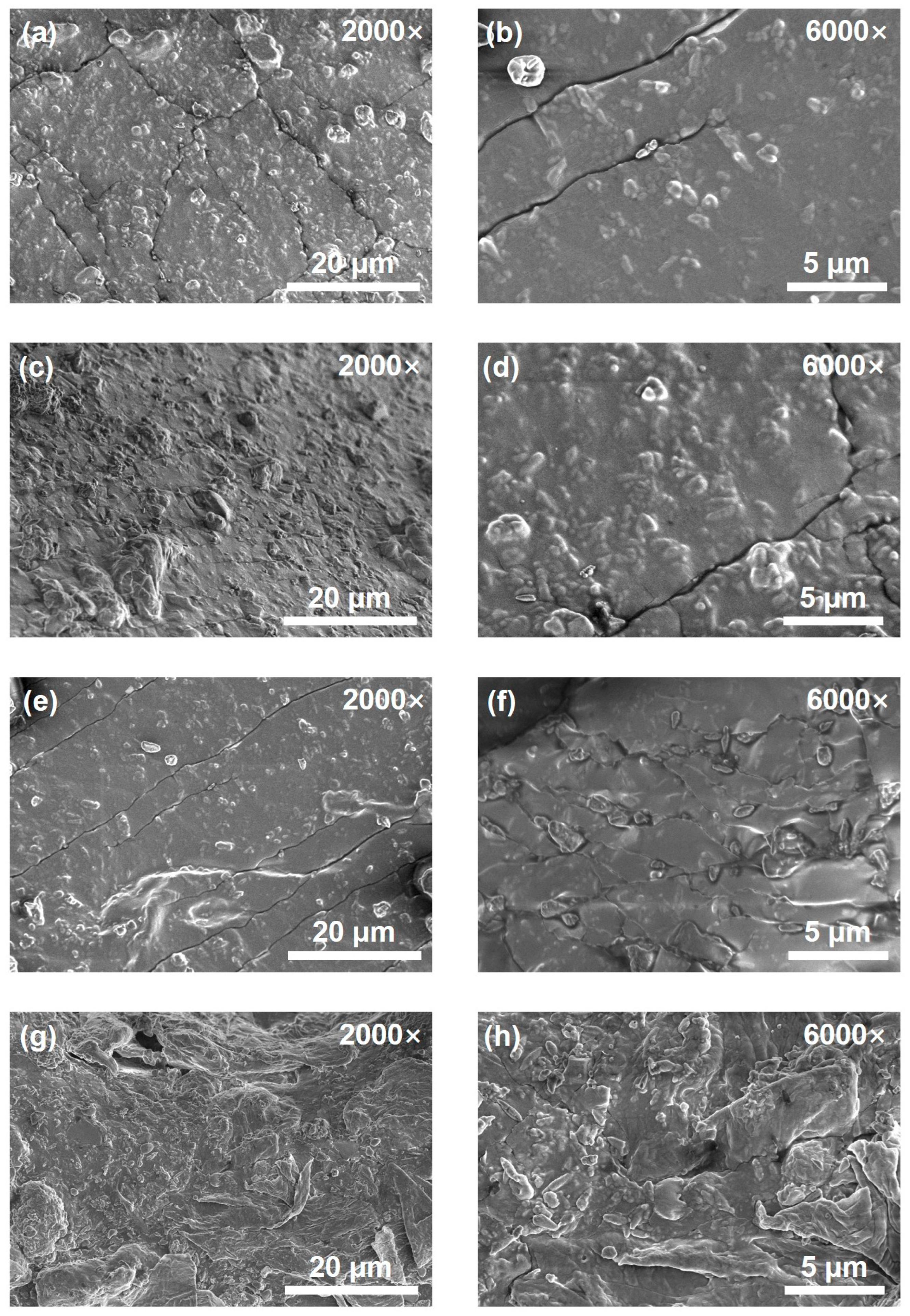

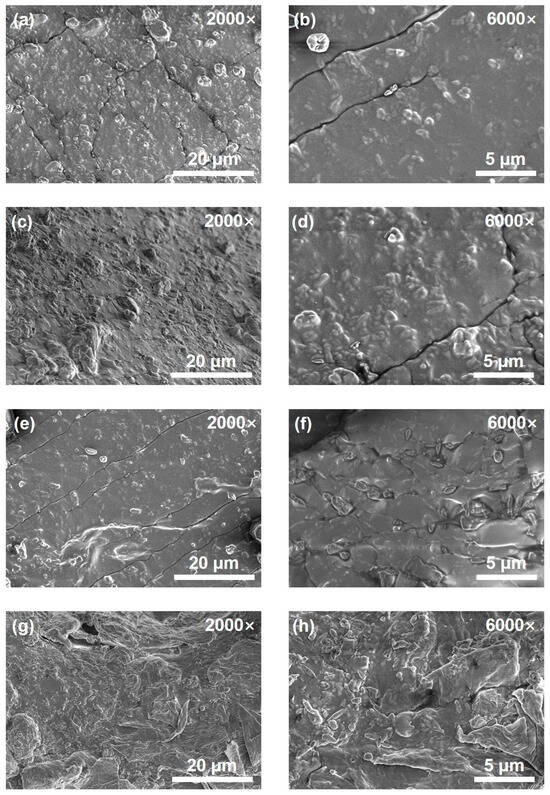

Figure 5 shows the SEM images of the cured CTPB/EP binder systems with different 593 cure accelerator contents at the magnifications of 2000× and 6000×. As can be seen, the surface of the control binder system sample (no 593 cure accelerator) is extremely uneven (Figure 5g,h), and the solid filler is concentrated in the lower left corner of the sample, showing obvious signs of incomplete curing. Figure 5a–f illustrate the surface morphologies of the CTPB/EP binder systems containing 0.3 wt.%, 0.5 wt.%, and 1 wt.% of 593 cure accelerator, respectively. When the amount of cure accelerator added is low, obvious cracks appear on the surface of the sample. These cracks can absorb a certain amount of energy when the sample is stretched, thereby increasing both the tensile strength and the elongation at break of the system. As the 593 cure accelerator content increased, the binder surface gradually became smoother. The cracks decrease in number and tend to align in the same direction. The compact and uniform surface morphology can contribute to the higher axial tensile strength of the binder with higher cure accelerator contents. However, it also diminishes the toughness of the binder to certain extents, leading to lower elongations at break as observed macroscopically.

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the CTPB/EP binder systems containing 0.3 wt.% (a,b), 0.5 wt.% (c,d), 1 wt.% (e,f) 593 cure accelerator and the control system sample (no 593 cure accelerator) (g,h). The left images are at a magnification of 2000×, and the right ones are at a magnification of 6000×.

2.5. Effects of 593 Cure Accelerator on Curing Kinetics of CTPB Binder

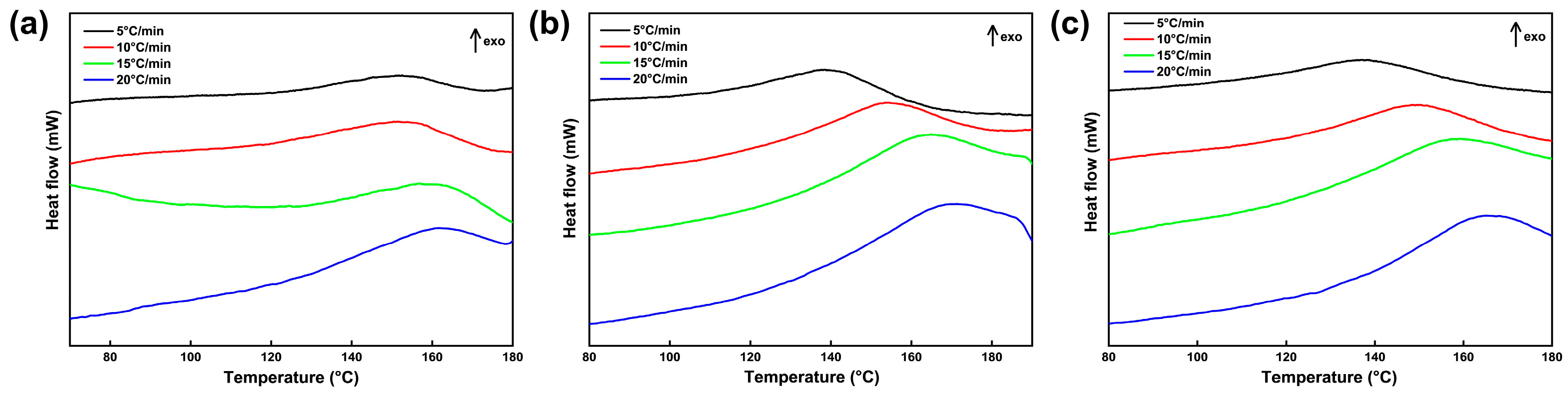

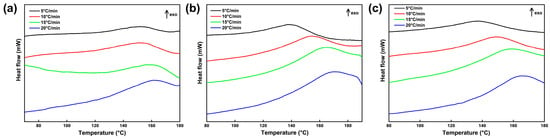

Studying the curing kinetics of the CTPB/EP binder system containing 593 cure accelerator is essential for understanding the affecting mechanism of the accelerator on the curing performance of CTPB binder and enabling the selection of optimal reaction conditions and controllable reaction process. It is of significant importance for tuning the binder network structure, predicting the pot life of the slurry, and preparing propellants that meet the requirements in mechanical and process properties. For the curing reaction kinetics analysis, three CTPB/EP binder systems containing 0 wt.%, 0.5 wt.%, and 1 wt.% 593 cure accelerators were prepared and subjected to mechanical testing and cross-linking network structure evaluation. Figure 6 displays the non-isothermal differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves of the three CTPB/EP binder systems at different heating rates. The characteristic peak temperatures of the DSC curves are listed in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves of CTPB/EP binder systems containing 0 wt.% (a), 0.5 wt.% (b), and 1 wt.% (c) 593 cure accelerator.

Table 1.

Thermal curing reaction characteristic temperatures of the CTPB/EP binder systems at different heating rates.

As can be seen from Figure 6 and Table 1, the corresponding exothermic peaks of all three binder systems shift to the high temperature region, and the peak shapes gradually become sharper with the increase in the heating rate. The cross-system comparison reveals that the temperature difference of the peak temperature () between the different heating rates gradually increases with the increase in 593 cure accelerator content. This can be explained by the strong curing promotion capability of 593 cure accelerator. Higher cure accelerator contents shorten the curing time. At lower cure accelerator contents, the phase transition from liquid to solid is longer, and thus the heat release is higher at a constant heat release rate during the exothermic curing reaction. Consequently, the peak temperature difference between low and high heating rates is smaller. The phase transition process at higher cure accelerator contents is fast and the curing time is shorter, which produces less heat dissipation during the process. Because the thermal conductivity of a solid is lower than that of a liquid, the shorter time and higher insulation rate result in larger temperature differences between low and high heating rates, while the exothermic heat release remains constant. This phenomenon clearly demonstrates the strong curing promotion effect of 593 cure accelerator on the CTPB/EP binder system.

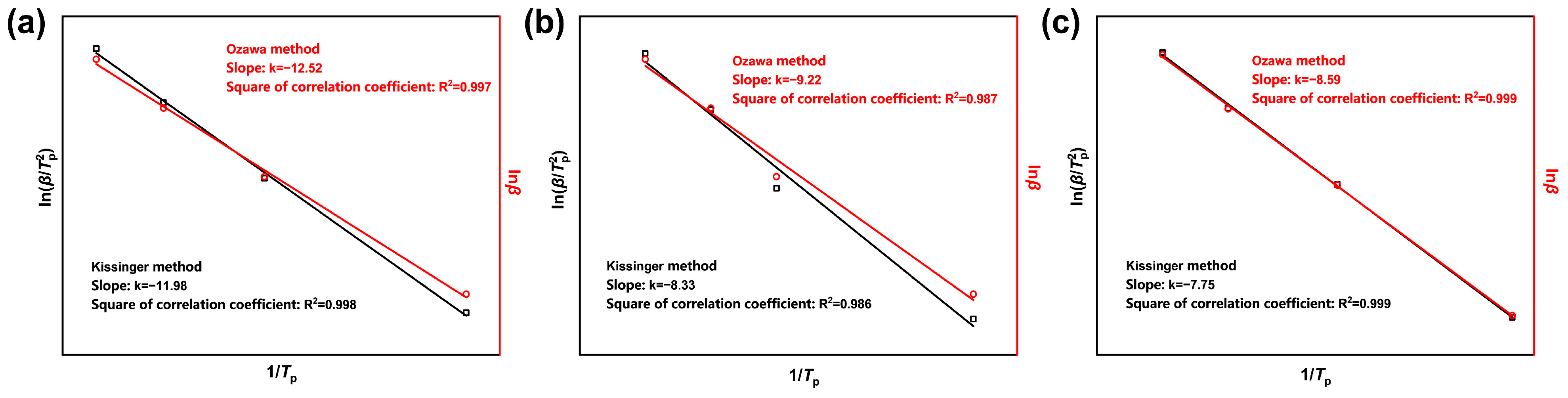

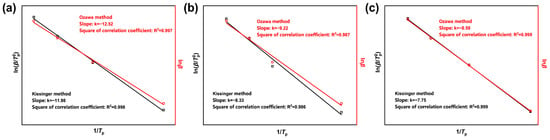

The non-isothermal curing kinetics parameters of the CTPB/EP binder system were determined by the linear fitting of against using the Kissinger method and the linear fitting of against using the Ozawa method [31]. The corresponding to the DSC curves of the three formulas at different heating rates were obtained from Table 1. The fitting results are shown in Figure 7, and the kinetic parameters obtained by the two fitting methods are presented in Table 2. The activation energies obtained by the two methods were then calculated and averaged.

Figure 7.

Curing kinetics fitting curves of CTPB/EP binder systems containing 0 wt.% (a), 0.5 wt.% (b), and 1 wt.% (c) 593 cure accelerator. is the heating rate (°C/min); is the peak temperature (°C).

Table 2.

Non-isothermal curing kinetic parameters of CTPB/EP binder systems.

The apparent activation energy of the curing reaction is higher for the binder system in the absence of 593 cure accelerator. The reaction rate is low at low temperatures and only significantly increases above the critical temperature. After the addition of the 593 cure accelerator, the average activation energy shows a decreasing trend with the increase in the cure accelerator content. This suggests that the 593 cure accelerator can effectively lower the energy barrier of the curing reaction of the CTPB/EP binder, making the reaction occur more easily and thereby increasing the reaction rate. This explanation, from the perspective of curing kinetics, elucidates the differences in the curing rate during the macroscopic curing process. The activation energy parameters obtained can provide strong support for the optimization of curing conditions and the regulation of the network structure.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Carboxy-terminated polybutadiene (CTPB; the carboxyl value is 0.588 mmol/g) was purchased from Liming Research Institute of Chemical Industry (Luoyang, China). Bisphenol A-type epoxy resin (E-51; epoxy equivalent: 184~195 g/mol) was purchased from Shandong Yousuo Chemical Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Heze, China). The 593 cure accelerator (hydroxyl value of 500~700 mg·KOH/g) was purchased from Guangzhou Yuanshengtai Chemical Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Dioctyl sebacate (DOS) and toluene were all analytical-grade. DOS was purchased from Zhengzhou Baotai Nanomaterials Co., Ltd. (Zhengzhou, China), and toluene was purchased from Shanghai Zhixin Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

3.2. Preparation of CTPB/EP Binder Systems

The formulas of different CTPB/EP binder systems are shown in Table 3. For a typical preparation process, E-51 was preheated in an oven at 70 °C for 20 min for better fluidity and mixed with a certain amount of CTPB. The mixture was put on a thermostatic stirrer of 70 °C and stirred at 300 rpm for 20 min until the system became milky white. After thorough stirring, the mixture was slowly poured into a polytetrafluoroethylene mold, transferred into a vacuum oven of 70 °C to remove air bubbles, and cured at 75 °C for 5–7 days.

Table 3.

Formulas of CTPB curing systems.

3.3. Measurements and Characterizations

3.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Testing

FTIR analysis of the binder samples was conducted using a Nicolet 8700 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in ATR mode. Spectra were collected in the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 with 64 scans.

3.3.2. Mechanical Testing

The obtained binder films were cut into dumbbell-shaped specimens (GBT528-2009 [32], Type 3) for the mechanical tests on an Instron 6022 general-purpose material testing machine (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA). The tensile tests were conducted at 25 °C at a tensile strain rate of 100 mm/min. Each test was repeated three times, and the mean value and standard deviation were calculated and recorded.

3.3.3. Crosslink Density Measurement

The cross-link densities of the cured binder films were determined by the density bottle method. A sample of approximately 0.25–0.35 g was cut from the binder film, accurately weighted as m0, and then immersed in 50 mL of toluene at 25 °C for 24 h. Fresh toluene was then added to continue the dissolution process for additional 48 h. The dissolved film was swiftly dried with filter paper and weighed, and the mass was recorded as ms. The film sample was then dried thoroughly to remove the toluene and weighed again, and the mass was recorded as md.

According to the Flory–Huggins polymer solution theory and the rubber entropy elasticity theory, for the dissolution of a polymer in a small-molecule solution, the maximum degree of dissolution is reached when its tendency to dissolve and elastic contraction reach the equilibrium state. In this state, the crosslink density of the polymer can be calculated with the Flory–Rehner equation as follows [33,34].

where is the crosslink density of the polymer, mol/cm3; is the average molecular weight between crosslinking points, g/mol; is the volume fraction of the polymer swollen in the solvent; is the molar volume of the solvent; is the interaction parameter of the polymer with the solvent; is the functional degree of the polymer crosslinking network; and is the density of the polymer.

can be calculated with Equation (2):

where is the density of the solvent.

can be obtained with the Bristow–Watson semi-empirical equation:

where is the ideal gas constant; is the absolute temperature; and and are the solubility parameters of the solvent and polymer respectively. The latter can be estimated by the group contribution method [35,36].

The gel fraction refers to the proportion of the macromolecular gel produced by the binder system in the total system after curing [37]. Under certain conditions, is related to the crosslinking network properties of the binder. It can be calculated as

3.3.4. Micro-Morphological Examination

The surface morphologies of the obtained binder films were imaged using a MIR-AXM cold field emission scanning electron microscope (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic). The samples were sprayed with a layer of gold before testing, and the accelerating voltage was set to 3.5 kV.

3.3.5. Curing Kinetics Testing

Three uncured CTPB binder formulas, each containing 10 mg CTPB and a certain amount of 593 cure accelerator, were accurately weighed, placed in a covered aluminum crucible in a N2 atmosphere, and allowed to cure at heating rates of 5 °C/min, 10 °C/min, 15 °C/min, or 20 °C/min. The DSC curves during the curing process were recorded using a 200 F3 differential scanning calorimeter (NETZSCH, Selb, Germany) to investigate the influences of the cure accelerator on the kinetics of CTPB curing reaction. The heating program consisted of three sections: the temperature ramping from room temperature to 200 °C at the preset heating rate to eliminate thermal history, the temperature being held at 200 °C for 30 min to ensure a complete reaction, and temperature decreasing from 200 °C to room temperature at the preset heating rate. The initial temperature (), peak curing temperature (), and final temperature () of the reaction at each heating rate were recorded. The apparent activation energy () is a measure of the minimum energy required for the resin to initiate the curing reaction, and its magnitude is one of the crucial factors in determining the curing reaction rate. The Kissinger Equation (5) and the Ozawa Equation (6) are the commonly used calculation methods of the activation energy for the curing reaction of thermosetting resins [38,39]. In this study, the curing reaction activation energy of each system was calculated by both the Kissinger method and Ozawa method, and the initial temperature, the peak curing temperature, and the post-curing treatment temperature of each system were determined by the T-β extrapolation method [40,41].

where is the heating rate (°C/min); is the molar gas constant with a value of 8.314 J/(mol·K).

4. Conclusions

To tackle the challenges of slow curing rate and suboptimal mechanical properties in the CTPB/EP binder system used for solid propellants, this study explored the impact of varying amounts of 593 cure accelerator—an aliphatic amine compound—on adhesive properties. The experimental results demonstrated that when the amount of 593 cure accelerator added was 0.3 wt.%, the tensile breaking strength of the adhesive increased by 95% compared to the original adhesive, reaching 0.37 MPa, while achieving the highest elongation at break of 655%. The crosslink density and gel fraction of the cured adhesive also gradually increased. The activation energy calculations for the curing reaction of the CTPB/EP binder system revealed that the 593 cure accelerator could significantly reduce the energy required for the curing reaction. In summary, this study clarified the preparation conditions for a CTPB/EP binder system with both high elongation at break and high tensile breaking strength. By adjusting the formulation, controllable regulation of the curing time and mechanical properties of the system was achieved.

This study achieved accelerated curing of the binder without increasing the curing temperature, thereby reducing the production cycle of solid propellant and significantly enhancing industrial production efficiency. Together, the relatively low curing temperature and optimized curing rate avoided filler aggregation, reduced thermal hazards, and enhanced process safety. Consequently, this work provides a solid research foundation for the application of this system in solid propellants.

Author Contributions

All listed authors have made a significant scientific contribution to the research in the manuscript, approved its claims, and agreed to be an author. Conceptualization: Y.C.; methodology: X.Q.; investigation: X.Q., P.H., X.M., Y.L. and H.Y.; supervision: W.Z. and Y.C.; writing—original draft: X.Q.; writing—review and editing: W.Z. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Yu Chen can be contacted to request the data at cylsy@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ji, Y.; Lu, R. Experimental Study of Rheological Properties of Solid Propellant Slurry at Low-Shear Rate and Numerical Simulation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Tang, G.; Guo, X.; Liu, C.; Pang, A.; Gan, L.; Huang, J. Network Regulation and Properties Optimization of Glycidyl Azide Polymer-Based Materials as a Candidate of Solid Propellant Binder via Alternating the Functionality of Propargyl-Terminated Polyether. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 48016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wang, X.; Bu, Z.; Li, B.-G.; Jie, S. Facile Access to Carboxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene and Polyethylene from Cis-Polybutadiene Rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 46934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyars, C.; Klager, K. Solid Propellants Based on Polybutadiene Binders. Adv. Chem. 1969, 88, 122–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Ping, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, F.; Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Gong, X. A Metal Coordination-Based Supramolecular Elastomer with Shape Memory-Assisted Self-Healing Effect. Polymers 2022, 14, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; López, R.; Rodríguez, J.; Salazar, A. Evaluation of the Structural Integrity of Solid Rocket Propellant by Means of the Viscoelastic Fracture Mechanics Approach at Low and Medium Strain Rates. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 118, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Salazar, A.; Rodríguez, J. Fatigue Crack Propagation Behaviour of Carboxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene Solid Rocket Propellants. Int. J. Fract. 2020, 223, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhou, W.; Sui, X.; Wang, Z.; Cai, H.; Wu, P.; Zuo, J.; Liu, X. A Carboxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene Liquid Rubber Modified Epoxy Resin with Enhanced Toughness and Excellent Electrical Properties. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 3776–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhou, W.; Kou, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, H.; Zhao, W. Heat Conductive H-BN/CTPB/Epoxy with Enhanced Dielectric Properties for Potential High-Voltage Applications. High Volt. 2017, 2, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.M.; Rosborough, L. Oxidation and Heat Aging of Carboxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1966, 10, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, F.; Sage, T.; Orbey, N.; Guven, O. Lifetime Prediction of Carboxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene (CTPB). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1991, 42, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fan, X.; Pan, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Pang, X. Simultaneously Enhancing Tribological and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Composites Using Basalt Fiber/Reduced Graphene Oxide/Paraffin Wax. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 3343–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pan, B.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; Fan, X.; Yue, E.; Li, M.; Qin, Y. Interfacial Tailoring of Basalt Fiber/Epoxy Composites by Metal–Organic Framework Based Oil Containers for Promoting Its Mechanical and Tribological Properties. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 4757–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielarek, M.; Stopa, N. Isocyanate-Free Carboxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene and Epoxidised Hydroxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene Cross-Linking System as a Binder in Solid Heterogeneous Propellants. Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mater. 2023, 20, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, K.; Verneker, V.R.P.; Vasanthakumari, R. Curing Reactions in Elastomers. II. Carboxy-Terminated Polybutadiene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1983, 28, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilev, V.G.; Rusakov, S.V.; Chudinov, V.S.; Rakhmanov, A.Y.; Kondyurin, A.V. Modeling the Curing Kinetics of an Epoxy Binder with Disturbed Stoichiometry for a Composite Material of Aerospace Purpose. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2021, 57, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, A.; Yudaev, P.; Shapagin, A.; Panfilova, D.; Palamarchuk, A.; Chistyakov, E.; Konstantinova, A.; Yudaev, P.; Shapagin, A.; Panfilova, D.; et al. Non-Flammable Epoxy Composition Based on Epoxy Resin DER-331 and 4-(β-Carboxyethenyl)Phenoxy-Phenoxycyclotriphosphazenes with Increased Adhesion to Metals. Sci 2024, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, B.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Ao, W.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhao, J. In Situ Monitoring of Curing Reaction in Solid Composite Propellant with Fiber-Optic Sensors. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 2664–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, H.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, E.; Jiang, H.; Shao, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, H.; et al. Study on the Rheological Properties of BGAP Adhesive and Its Propellant. Molecules 2025, 30, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Fan, Y.; Huo, J. Hydroxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene Curing by 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Energetic Nitrile N-Oxides: Room Temperature Curing Property, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Propellant Combustion Characteristics. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2019, 44, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, A.; Konstantinova, A.; Korotkov, R.; Yudaev, P.; Mezhuev, Y.; Terekhov, I.; Gurevich, L.; Chistyakov, E.; Orlov, A.; Konstantinova, A.; et al. Epoxy Compositions with Reduced Flammability Based on DER-354 Resin and a Curing Agent Containing Aminophosphazenes Synthesized in Bulk Isophoronediamine. Polymers 2022, 14, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Cao, T.; Liu, P.; Ma, C.; Li, P.; Huang, D. Study on the Compounding of a New Type of Trimer Epoxy Resin Curing Agent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 52368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; An, C.; Li, F. Rheological Impact of Particle Size Gradation on GAP Propellant Slurries. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 38536–38542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Khan, L.; Mandal, S.K.; Jauhari, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.C. Studies on the Processing of HTPB-Based Fast-Burning Propellant with Trimodal Oxidiser Distribution and Its Rheological Behaviour. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 17, e2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatenko, V.Y.; Ilyin, S.O.; Kostyuk, A.V.; Bondarenko, G.N.; Antonov, S.V. Acceleration of Epoxy Resin Curing by Using a Combination of Aliphatic and Aromatic Amines. Polym. Bull. 2020, 77, 1519–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laza, J.M.; Julian, C.A.; Larrauri, E.; Rodriguez, M.; Leon, L.M. Thermal Scanning Rheometer Analysis of Curing Kinetic of an Epoxy Resin: 2. An Amine as Curing Agent. Polymer 1999, 40, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizza, J.R.; Moura-Letts, G. Solvent-Directed Epoxide Opening with Primary Amines for the Synthesis of β-Amino Alcohols. Synthesis 2017, 49, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bi, X.; Liu, G.; Cao, L.; Sun, C.; Tana, H.; Zhang, Y. Study on improving the toughness of rapidly curing epoxy resin composite materials with a biobased microcrystalline cellulose. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Ren, Y.; Tan, J.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, X. Preparation and properties of epoxy adhesives with fast curing at room temperature and low-temperature resistance. ACS Omega 2024, 20, 22186–22195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kezhen, Y.; Junyi, S.; Kaixin, S.; Min, W.; Goukai, L.; Zhe, H. Effects of the Chemical Structure of Curing Agents on Rheological Properties and Microstructure of WER Emulsified Asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraker, B.M.; Lobo, B. Multistage Thermal Decomposition in Films of Cadmium Chloride-Doped PVA–PVP Polymeric Blend. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 134, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 528-2009; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Flory, P.J.; Rehner, J., Jr. Statistical Mechanics of Cross-Linked Polymer Networks I. Rubberlike Elasticity. J. Chem. Phys. 1943, 11, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, K.; He, J.; Yang, R. Facile Synthesis of Three Diazido Compounds and Their Application in Polyether Polytriazido Elastomers as Solid Propellant Binders. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 4940–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, G.M.; Watson, W.F. Cohesive Energy Densities of Polymers. Part 2.—Cohesive Energy Densities from Viscosity Measurements. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1958, 54, 1742–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, S.C.; Sunitha, K.; Mathew, D.; Reghunadhan Nair, C.P. Acrylic Copolymers Crosslinked by Click Chemistry: Some Aspects of Synthesis, Curing, and Crosslinking. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 130, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gong, X.; Zhao, C.; Zou, G. The Effect of Peroxides on the Structure of High-Melt-Strength Polylactide with Long-Chain Branched Architecture or Micro-Crosslinking. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2023, 34, 3735–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Variation of Peak Temperature with Heating Rate in Differential Thermal Analysis. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1956, 57, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S. Kissinger Method in Kinetics of Materials: Things to Beware and Be Aware Of. Molecules 2020, 25, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Z.; Ning, Q.; Shaohua, J.; Suping, W. Research on the Preparation of Heat-Resistant Epoxy Resin Cured by o-Carborane-Based Diamine. High Perform. Polym. 2018, 30, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.; Rahman, M.B.; Shen, W.; Zhu, C. The Curing Kinetics of E-Glass Fiber/Epoxy Resin Prepreg and the Bending Properties of Its Products. Materials 2021, 14, 4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.