Abstract

Intensive analysis of the culture broth of the marine-derived Penicillium sp. strain SCH3-Sd2 led to the isolation of one spirocyclic diketopiperazine alkaloid, spirotryprostatin H (1), as well as two indolyl diketopiperazines, fumitremorgins O and P (2 and 3). The planar structures of 1–3 were elucidated by comprehensive spectroscopic analyses, while their absolute configurations were determined by combined NOESY and ECD analyses, and the configuration of the proline moiety was further confirmed using the advanced Marfey’s method. The evaluation of the antibacterial activity of compounds 1–3 against six bacterial strains revealed weak and selective activity only against Kocuria rhizophila KCTC 1915, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 64, 128, and 64 μg/mL, respectively.

1. Introduction

Fungi exhibit remarkable adaptability, which enables them to colonize diverse habitats, including marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments [1,2]. Their ability to withstand extreme environmental conditions has driven the evolution of unique metabolic pathways in marine fungal species [3]. Secondary metabolites produced through these specialized metabolic pathways show promising applications in drug discovery [4]. Notably, fungi belonging to the genus Penicillium are commonly found in marine environments, and secondary metabolites produced by these strains have been shown to possess a broad array of biological activities [5]. In particular, indole diketopiperazine alkaloids from Penicillium, recognized as privileged structures, show significant biological activities, including antimicrobial, antiviral, anticancer, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and insecticidal effects [6,7,8].

In typical laboratory conditions, the inefficient production of bioactive compounds by marine fungi is attributed to the quiescence of numerous biosynthetic gene clusters [2]. Recent developments in cultivation-based strategies aim to activate these silent gene clusters [9]. Variations in cultivation parameters, including in nutrient composition, temperature, salinity, aeration, and even the geometry of culture flask, have been employed to induce the production and facilitate the discovery of novel natural products [10]. This approach, known as the one strain−many compounds (OSMAC) strategy, facilitates the exploration of the diverse variety of complex chemical structures hidden within the specific strains [11].

Upon incorporating the OSMAC strategy into our ongoing bioprospecting effects for novel bioactive natural products from marine fungi, the cultivation of Penicillium sp. SCH3-Sd2 in potato dextrose broth (PDB) under static culture conditions yielded a markedly different metabolite profile compared to those of strain grown under shaking conditions. This finding prompted an in-depth investigation into the chemical constituents using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) chemical profiling and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses. Subsequent studies resulted in the isolation of spirotryprostatin H (1) from a 7-day shake culture, while fumitremorgin O and P (2 and 3) were obtained from a 21-day static culture. Herein, we report on the isolation, structures, and bioactivities of these compounds.

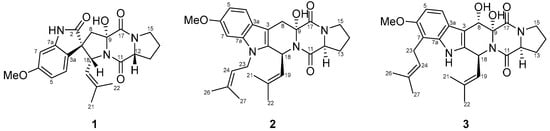

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1–3.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Elucidation

Spirotryprostatin H (1) was isolated as a pale-yellow powder, and its molecular formula was determined as C22H25N3O5 on the basis of a protonated adduct observed at m/z 410.1726 [M−H]− (calcd for C22H24N3O5, 410.1721) in high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (HR-ESI-MS). The 1H NMR spectroscopic data displayed three aromatic protons H-4 (δH 6.99, d, J = 8.3 Hz), H-5 (δH 6.50, dd, J = 8.3, 2.4 Hz), H-7 (δH 6.40, d, J = 2.4 Hz), one methoxy group 6-OMe (δH 3.72, s), and two methyl groups H-21 (δH 1.16, s) and H-22 (δH 1.49, s). 13C and HSQC NMR spectra revealed the presence of three aromatic methine carbons C-4 (δC 126.8), C-5 (δC 106.7), C-7 (δC 96.5); methoxy carbon 6-OMe (δC 55.2), and two methyl carbons C-21 (δC 17.7) and C-22 (δC 25.1). Further analysis of the 13C and HSQC NMR data enabled the assignment of four methylene groups C-8 (δC 41.2)/H-8 (δH 2.35, d, J = 15.0 Hz and 2.89, d, J = 15.0 Hz), C-13 (δC 27.8)/H-13 (δH 1.89, m and 2.22, m), C-14 (δC 22.7)/H-14 (δH 1.90, m), and C-15 (δC 44.8)/H-15 (δH 3.43, m), methine groups C-12 (δC 60.1)/H-12 (δH 4.44, m), C-18 (δC 60.9)/H-18 (δH 4.79, d, J = 9.0 Hz), and C-19 (δC 121.8)/H-19 (δH 4.92, d, J = 9.0 Hz), as well as three carbonyl groups C-2 (δC 182.3), C-11 (δC 168.2), and C-17(δC 164.3). These NMR data indicated that 1 contains a skeleton similar to the oxindole diketopiperazine structure observed in spirotryprostatin A [12], and asperdiketopoid D [13], except for the presence of a hydroxyl group at 9-OH (δH 7.42, s)/C-9 (δC 89.4) (Table 1, Figure 1). Compound 1 shares the same indole diketopiperazine core as spiro spirotryprostatin A and asperdiketopoid D; however, a clear structural difference is observed at the C-9 position. In spirotryprostatin A and asperdiketopoid D, C-9 is a methine carbon, whereas in compound 1, C-9 is an oxygenated quaternary carbon (δC 89.4) bearing a hydroxy group. This difference is supported by the absence of C-9 proton signal in 1H NMR spectrum of 1 and the corresponding downfield shift in the 13C NMR data (Table 1).

Table 1.

NMR data for compounds 1–3 in DMSO-d6.

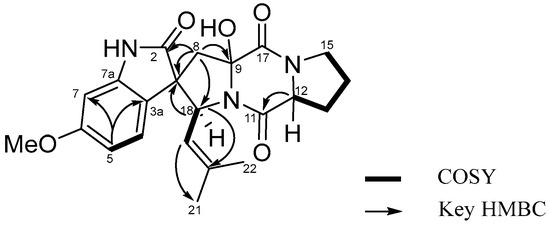

The analysis of COSY, HSQC and HMBC NMR spectroscopic data enabled the construction of distinct fragments with a unique structural skeleton, characterized by a spiro ring system. This system consists of a γ-lactam fused to a benzene ring and a pentacyclic enamine linked to a diketopiperazine moiety. The diketopiperazine moiety, linked to the pentacyclic enamine derived from a proline residue and to an isoprenyl group, was assigned based on the long-range HMBC correlations from 9-OH (δH 7.42, s) to C-9 (δC 89.4) and C-17 (δC 164.3), from H-8 (δH 2.35, d, J = 15.0 Hz and 2.89, d, J = 15.0 Hz) to C-2 (δC 182.3), C-3 (δC 55.9), C-3a (δC 119.8), C-9 (δC 89.4), and C-18 (δC 60.9), and from H-12 (δH 4.44, m) to C-11 (δC 168.2), and C-13 (δC 27.8). The isoprenyl group was characterized by the COSY correlations H-18 (δH 4.79, d, J = 9.0 Hz)/H-19 (δH 4.92, d, J = 9.0 Hz), combined with the HMBC correlations from H-18 (δH 4.79, d, J = 9.0 Hz) to C-2 (δC 182.3), C-3 (δC 55.9), C-8 (δC 41.2), C-19 (δC 121.8), C-20 (δC 135.2), from H-19 (δH 4.92, d, J = 9.0 Hz) to C-21 (δC 17.7) and C-22 (δC 25.1), from H-21 (δH 1.16, s) to C-19 (δC 121.8), C-20 (δC 135.2), C-22 (δC 25.1), and from H-22 (δH 1.49, s) to C-19 (δC 121.8), C-20 (δC 135.2), and C-21 (δC 17.7) (Figures S1–S7). These results illustrate the connectivity of the spiro ring system, which comprised a γ-lactam fused to a benzene ring and a pentacyclic enamine associated with the diketopiperazine moiety. Thus, the planar structure of 1 was assigned as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

COSY and key HMBC correlations of 1.

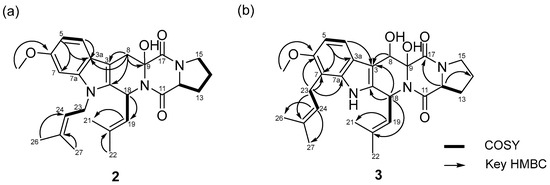

Fumitremorgin O (2), obtained as a pale-yellow amorphous powder, possessed a molecular formula of C27H33N3O4, as determined from its HRESIMS ion peaks at m/z 464.2542 [M+H]+ (calcd for C27H34N3O4, 464.2544). Both the UV and NMR spectra consistently confirmed the presence of an indole diketopiperazine system within compound 2 [14]. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 indicated the presence of one methoxyl proton 6-OMe (δH 3.76, s), four methyl protons H-21 (δH 1.91, s), H-22 (δH 1.59, s), H-26 (δH 1.85, s),and H-27 (δH 1.66, s), five sets of methylene protons H-8 (δH 3.08, d, J = 16.0 Hz and 3.40 d, J = 16.0 Hz), H-13 (δH 1.85, m and 2.27, m), H-14 (δH 1.86, m), H-15 (δH 3.45, m), and H-23 (δH 4.54, m and 4.64, m), and four methine protons H-12 (δH 4.37, m), H-18 (δH 5.93 d, J = 9.8 Hz), H-19 (δH 4.82, d, J = 9.8 Hz), H-24 (δH 4.98, m), and three aromatic protons H-4 (δH 7.42, d, J = 8.2 Hz), H-5 (δH 6.69, dd, J = 8.3 and 2.2 Hz), and H-7 (δH 6.80, d, J = 2.2 Hz). The 13C NMR and HSQC spectra displayed 27 carbon signals, including eight indole carbons C-2 (δC 132.3), C-3 (δC 103.3), C-3a (δC 121.1), C-4 (δC 118.4), C-5 (δC 108.5), C-6 (δC 155.3), C-7 (δC 93.5), and C-7a (δC 137.0), one methoxy carbon 6-OMe (δC 55.0), four methyl carbons C-21 (δC 17.7), C-22 (δC 25.1), C-26 (δC 18.0), and C-27 (δC 25.2), five methylene carbons C-8 (δC 29.4), C-13 (δC 28.5), C-14 (δC 22.1), C-15 (δC 44.9), and C-23 (δC 41.0), four methine carbons C-12 (δC 57.9), C-18 (δC 40.7), C-19 (δC 123.1), and C-24 (δC 120.4), two carbonyl carbons C-11 (δC 164.9) and C-17 (δC 169.9), and four quaternary carbons C-9 (δC 82.9), C-11 (δC 164.9), C-20 (δC 132.9), and C-25 (δC 133.7). Thorough analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1 and Table 2), combined with the COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure 3), revealed that 2 shared the same planar structure as the prenylated indole diketopiperazine alkaloid fumitremorgin B [15], except for the presence of a methylene group at H-8 (δH 3.08, d, J = 16.0 Hz and 3.40, d, J = 16.0 Hz)/C-8 (δC 29.4). This substitution was confirmed by the HMBC correlations from H-8 (δH 3.08, d, J = 16.0 Hz and 3.40, d, J = 16.0 Hz) to C-2 (δC 132.3), C-3 (δC 103.3), C-3a (δC 121.1), and C-9 (δC 82.9) (Figures S9–S15). In addition, the methylene carbon C-23 exhibited a characteristic downfield chemical shift at δC 41.0, which is consistent with a nitrogen-adjacent methylene (N–CH2–) environment. This observation strongly supports the assignment of the isoprenyl unit being directly attached to the indole nitrogen (N-1), despite the weak or ambiguous long-range HMBC correlations involving H2-23. Taken together, the spectroscopic data led to the definitive planar structural assignment of 2 (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

COSY and key HMBC correlations of 2 (a) and 3 (b).

Fumitremorgin P (3) was isolated as a pale-yellow amorphous powder. Its molecular formula was determined to be C27H33N3O5 based on the HRESIMS ion peaks at m/z 480.2495 [M+H]+ (calcd for C27H34N3O5, 480.2493). Detailed analysis of the NMR data (Figures S17–S23 and Table 1) indicated that compound 3 contained an indole diketopiperazine system similar to fumitremorgin B (7) except for the presence of an isoprenyl unit [C-23 (δC 23.4) to C-27 (δC 25.2)] attached to the indole C-7 (δC 111.9). Additionally, the 1H NMR spectrum displayed an additional hydroxyl group C-8 (δC 67.8). The key HMBC correlations from H-23 (δH 3.41, m and 3.54, m) to C-6 (δC 152.2), C-7 (δC 111.9), C-7a (δC 136.5), and C-24 (δC 123.1) confirmed the location of the isoprenyl unit [C-23 (δC 23.4) to C-27 (δC 25.2)] and allowed to assign the complete planar structure of 3 (Figure 3b). Comparison of compounds 2 and 3 revealed that, while both share a fumitremorgin-type indole diketopiperazine framework, they differ in their prenylation and hydroxylation patterns. Compound 2 possesses a methylene group at C-8 and an N-1-linked isoprenyl unit, whereas compound 3 features an additional hydroxy group at C-8 and a differently positioned isoprenyl unit attached to the indole C-7, as supported by key HMBC correlations. These structural features clearly distinguish compounds 2 and 3 from each other and from previously reported fumitremorgin analogues.

Spirotryprostatin H (1) and fumitremorgins O (2) and P (3) expand the chemical space of prenylated indole diketopiperazines, a well-recognized class of secondary metabolite produced by Aspergillaceae [16]. Compared to previously reported congeners, the presence of the 9-hydroxy-substituted oxindole system in 1 is uncommon within this scaffold, suggesting that late-stage, enzyme-mediated oxidation reactions substantially contribute to structural diversification in this biosynthetic pathway [17,18]. Similarly, the distinct prenylation patterns observed for 2 and 3 further highlight the flexibility of DKP cyclization and subsequent post-NRPS modifications.

Taken together, these findings show that marine-derived fungal strains continue to generate unique structural variations within the spirotryprostatin and fumitremorgin lineages. Such structural diversity, arising from oxidative and prenylation-driven modifications, provides a broader platform for the exploration of structure–activity relationship in prenylated indole DKPs.

2.2. Absolute Configurations of Compounds 1–3

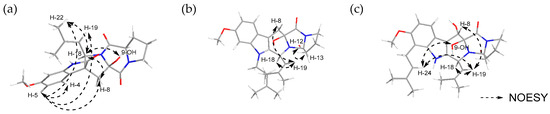

The relative stereochemistry of compounds 1–3 was determined through NOESY experiments. For compound 1, NOESY correlations were observed between H-4 (δH 6.99) and H-5 (δH 6.50), H-8 (δH 2.35 and 2.89), H-19 (δH 4.92), and H-22 (δH 1.49), between H-18 (δH 4.79) and H-8 (δH 2.35 and 2.89), H-21 (δH 1.16) and H-22 (δH 1.49), between H-19 (δH 4.92) and H-8 (δH 2.89), H-21 (δH 1.16), and H-22 (δH 1.49), as well as between 9-OH (δH 7.42) and H-12 (δH 4.44)/H-18 (δH 4.79). This indicated that these protons resided on the same face, which allowed the relative configuration as 9R*, 18R* (Figure 4a). For compound 2, the NOESY correlations observed between H-12 (δH 4.37) and H-13 (δH 2.27), between H-19 (δH 4.82) and H-8 (δH 3.08), as well as between H-18 (δH 5.93) and H-19 (δH 4.82) indicated that these protons were located on the same face, enabling the relative configuration to be assigned as 9R*, 18S* (Figure 4b). In the case of compound 3, NOESY correlations were established between H-18 (δH 5.83) and H-19 (δH 4.78), between H-8 (δH 5.51) and H-19 (δH 4.78), and H-24 (δH 5.20), between 9-OH (δH 4.09) and H-24 (δH 5.18), as well as between 8-OH (δH 4.76) and H-18 (δH 5.83), supporting the assignment of 8R*, 9S*, 18R* as the relative configuration of 3 (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

NOESY correlation of (a) spirotryprostatin H (1), (b) fumitremorgin O (2), and (c) fumitremorgin P (3).

The absolute configurations of proline (Pro) moiety in compounds 1–3 were determined through acid hydrolysis, followed by the advanced Marfey’s method [19]. The retention times of the 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-leucineamide (L-FDLA) derivatives of the constituent proline residues in 1–3 were evaluated using LC-ESI-MS. The Pro amino acid in compound 1 was identified as possessing a D-configuration, meaning the R configuration at C-12 (Figure S26), whereas those in compounds 2 and 3 were determined to a possess an L-configuration, meaning the S configuration at C-12 (Figure S27).

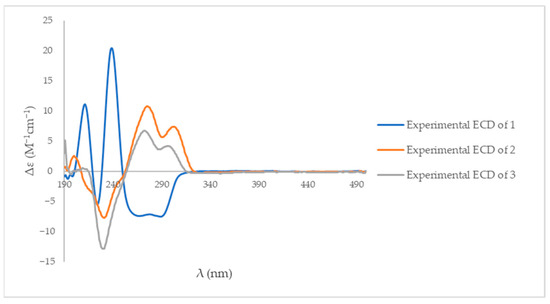

The ECD spectrum of compound 1 displayed a negative Cotton effect with a minimum at 282 nm and a positive Cotton effect with a maximum at 242 nm (Table S1). Compounds 2 and 3 exhibited negative Cotton effects with minima at 229 nm, while positive Cotton effects were observed with maxima at 270 nm for compound 2 and 292 nm for compound 3 (Table S1). Compared with previously reported ECD data for structurally related spirotryprostatin [20,21,22] and fumitremorgin [8,20] analogues, these Cotton effect patterns were consistent with a 3R configuration for compound 1 and supported the stereochemical assignments for compounds 2 and 3 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The experimental ECD spectra of compounds 1–3 in methanol.

Based on the NOESY spectra, the comparison with the ECD data of reported analogues, and the advanced Marfey’s method, the absolute configuration of spirotryprostatin H (1) was assigned as 3R, 9R, 18R, 12R, whereas that of fumitremorgins O (2) and P (3) was assigned as 9R, 18S, 12S and 8S, 9R, 18S, 12S, respectively.

2.3. Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activities of compounds 1–3 were evaluated against three Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis KCTC 1021, Kocuria rhizophila KCTC 1915, and Staphylococcus aureus KCTC 1621) and three Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli KCTC 2441, Salmonella typhimurium KCTC 2515, and Klebsiella pneumoniae KCTC 2690). Among the tested strains, compounds 1–3 displayed weak antibacterial effects only against Kocuria rhizophila KCTC 1915, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 64, 128, 64 μg/mL, respectively (Table 2). In contrast, no significant inhibitory effects were observed against the other bacterial strains, indicating that the present compounds possessed selective and weak antibacterial activity

The weak antibacterial activity of compounds 1–3, which was only observed against the Gram-positive strain K. rhizophila, may be attributed to structural factors such as low membrane permeability or limited interaction with bacterial targets. This lack of efficacy against Gram-negative bacteria is consistent with previous findings that the outer membrane of Gram-negative species serves as a permeability barrier, limiting the entry of indole-based metabolites and related compounds [23,24,25]. This selectivity suggests that the present compounds are not broad-spectrum antibiotics, but could serve as scaffolds for structural modifications to enhance the antibacterial of a drug.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity (MIC, μg/mL) of compounds 1–3 a.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity (MIC, μg/mL) of compounds 1–3 a.

| Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (μg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | Gram (+) Bacteria | Gram (−) Bacteria | ||||

| B. subtillis KCTC 1021 | K. rhizophila KCTC 1915 | S. aureus KCTC 1621 | E. coli KCTC 2441 | S. tyhimurium KCTC 2515 | K. pneumonia KCTC 2690 | |

| 1 | >128 | 64 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| 2 | >128 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| 3 | >128 | 64 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Ampicillin | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 64 | 16 | >128 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

a Each sample was tested in triplicate.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were determined using a Krüss Optronic P-8000 polarimeter with a 5-cm cell (Krüss, Hambrug, Germany) in methanol (MeOH). UV spectra were acquired with a Varian Cary 50 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Varian Inc., Mulgrave, Australia), whereas ECD spectra were obtained using a JASCO J-810 spectrometer (JASCO Inc., Tokyo, Japan). IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS 10 FT-IR spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA). The weak absorption observed around 2200–2400 cm−1 was also present in the CHCl3 blank spectrum and was therefore attributed to background signals rather than the sample (Figure S25). NMR spectra were obtained utilizing a Varian Inova spectrometer (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Charlottesville, VA, USA) operating at 500 MHz for 1H and 125 MHz for 13C experiments, and a Bruker NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Middlesex, MA, USA) working at 300 MHz for 1H measurements. The residual solvent signals served as internal references, with δH 3.31 ppm and δC 49.0 ppm for deuterated methanol (CD3OD), and δH 7.26 and 1.56 ppm for chloroform-d (CDCl3). Low-resolution LC-MS data were measured using the Agilent Technologies 1260 quadrupole (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Waters Micromass ZQ LC/MS system with a reversed-phase column (Phenomenex Luna C18 (2), 100 Å, 100 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), operating at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, at the National Research Facilities and Equipment Center (NanoBioEnergy Materials Center) at Ewha Womans University. Column chromatography (CC) experiment was performed using a reversed-phase C18 gel (70-230 mesh, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with a step-gradient solvent of water (H2O) and methanol (MeOH). Subsequently, the fractions were purified using a reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm, 2.0 mL/min, 5 μm) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the antibacterial test was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) for various sample dilutions using a SpectraMax® ABS Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

3.2. Collection and Identification of the Strain SCH3-Sd2

Marine sediment was collected on June 15, 2020, from Suncheon, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea (34°50′47.9″ N; 127°31′28.3″ E). A 100 μL aliquot of the sediment suspension, prepared by suspending the sample in 1 × PBS solution, was spread onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, BD DifcoTM, Sparks, MD, USA) plates supplemented with 3.5% (w/v) NaCl, 0.01% (w/v) ampicillin, and 0.01% (w/v) streptomycin. The plates were incubated at 20 °C for 7 days. After incubation, the developed colonies were repeatedly transferred onto fresh media to obtain pure isolates. The isolates were preserved in 20% glycerol solution at −80 °C.

One of the isolates, designated SCH3-Sd2, was identified based on the nucleotide sequence of the β-tubulin gene marker (Figure S28). The strain was first inoculated into potato dextrose broth (PDB; BD, USA) and incubated at 25 °C for 3 days to obtain mycelia. Genomic DNA was extracted from the harvested mycelia using the phenol-chloroform method [26]. The β-tubulin fragment was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers Bt2a and Bt2b [27]. The resulting 415 bp PCR product was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea).

The β-tubulin sequence of SCH3-Sd2 was used as a query for a BLAST search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (accessed on 10 October 2025) in the NCBI database to assess its homology with closely related fungal species. Based on the homology analysis, the β-tubulin sequence of SCH3-Sd2 showed 99.76% identity with that of the Penicillium caprifimosum strain MGS 2017. As a result, SCH3-Sd2 was identified as P. caprifimosum. This strain has been deposited in the Marine BioBank database of the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), under accession number MABIK FU00001487.

3.3. Fermentation, Extraction, and Isolation

The strain SCH3-Sd2 underwent two distinct culturing procedures. First, it was cultivated under shaking conditions in 10 L of 2.5 L Ultra Yield® flasks (Thomson Instrument Company, Oceanside, CA, USA) with 1 L of PDB SW medium (24 g/L of PDB and 37.8 g/L of sea salt in 1 L of distilled water), followed by shaking at 120 rpm and 27 °C. After 7 days of cultivation, the broth was extracted using ethyl acetate (EtOAc) to produce 10 L of extract, and the soluble fraction was further concentrated in vacuo to obtain 2.5 g of crude extract. The crude extract was subjected to flash column chromatography on a C18 resin eluted with H2O/CH3OH (80/20, 60/40, 50/50, 40/60, 30/70, 20/80, 0/100, 200 mL each) to obtain seven fractions (F1–F7). Then, fraction 4 (166.5 mg) underwent purification via reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm, 2.0 mL/min, 5 μm, UV = 254 nm) using 30% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), yielding spirotryprostatin H (1, 2.9 mg, tR = 41.0 min).

In the subsequent culture, SCH3-Sd2 was statically cultured in 18 L of 2.5 L Ultra Yield® flasks containing 1 L of PDB SW medium for 21 days at 27 °C. After cultivation and extraction using EtOAc (18 L extract overall), the soluble fraction was subsequently concentrated to yield 7.0 g of crude extract. Moreover, fraction 6 (214.5 mg) underwent further purification by reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm, 2.0 mL/min, 5 μm, UV = 254 nm) under isocratic conditions using a 50% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA as the mobile phase. The procedure performed under either low-light or dark conditions led to the isolation of fumitremorgin O (2, 4.7 mg, tR = 60.5 min) and fumitremorgin P (3, 11.2 mg, tR = 52.5 min).

Spirotryprostatin H (1): pale-yellow powder; = −97 (c 0.05, chloroform); UV (MeOH) max (log ε) 201 (3.17), 219 (3.16), and 298 (2.10) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3595, 2955, 2939, 1717, 1684, 1653, 1540, 1376 and 1061 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data (400 and 100 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 410.1726 [M−H]− (calcd for C22H24N3O5, 411.1721).

Fumitremorgin O (2): pale-yellow amorphous powder; = +128 (c 0.05, chloroform); UV (MeOH) max (log ε) 217 (3.26), 276 (1.78), and 295 (1.71) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2955, 2924, 1653, 1458, 1379, 1225, 1172, and 1083 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data (400 and 100 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 464.2542 [M+H]+ (calcd for C27H34N3O5, 464.2544).

Fumitremorgin P (3): pale-yellow amorphous powder; = +128 (c 0.05, chloroform); UV (MeOH) max (log ε) 202 (3.20), 220 (3.17), and 298 (2.66) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3597, 2954, 1718, 1686, 1653, 1506, 1457, 1209 and 1079 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data (400 and 100 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 480.2495 [M+H]+ (calcd for C27H34N3O4, 480.2493).

3.4. Acid Hydrolysis and Advanced Marfey’s Analysis of Spirotryprostatin H

The absolute configurations of spirotryprostatin H (1), fumitremorgin O (2), and fumitremorgin P (3) were determined using the advanced Marfey’s method. Samples of compounds 1–3 (1 mg each) were dissolved in 100 μL of 2 N HCl and heated at 100 °C for 12 h. The resulting hydrolysate was evaporated to dryness under a stream of N2 gas; the residue was subsequently redissolved in distilled H2O and divided into two aliquots. After removing water under a continuous N2 stream, each hydrolysate was dissolved in 100 μL of 1 N NaHCO3 and derivatized with 100 μL of 1% L-FDLA (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-leucine amide) in acetone. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 65 °C for 1 h and subsequently quenched with 2 N HCl. A small volume of CH3CN (100 μL) was added to the reaction products and injected into the LC-ESI-MS system with following chromatographic conditions: Phenomenex Luna C18 (2) 100 Å, 100 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, 1 mL/min flow, solvent A (0.01% formic acid in H2O), solvent B (0.01% formic acid in CH3CN), A/B = 95:5 → 50:50 (50 min) → 100:0 (70 min) → 0:100 (85 min) → 95:5 (90 min). The standard amino acids were prepared according to an established protocol and subsequently analyzed. The reaction products were analyzed using UV spectroscopy at 340 nm in positive ESIMS mode [28].

3.5. Antibacterial Activity Assay

Antibacterial susceptibility assays were conducted against six pathogenic bacterial strains: Escherichia coli (KCTC 2441), Salmonella typhimurium (KCTC 2515), Klebsiella pneumoniae (KCTC 2690), Bacillus subtilis (KCTC 1021), Kocuria rhizophila (KCTC 1915), and Staphylococcus aureus (KCTC 1621). Bacterial cultures were grown overnight in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) at 37 °C. The bacterial suspensions were subsequently adjusted to match the 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1.0 × 108 CFU/mL) and further diluted to achieve a final inoculum concentration of 5.0 × 105 CFU/mL.

The test compounds and positive controls (ampicillin and vancomycin) were initially dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare stock solutions with a concentration of 10 mg/mL. These stock solutions were further diluted in MHB to achieve a working concentration of 256 μg/mL. A 100 μL aliquot of each prepared sample was added to the first column of a sterile 96-well microtiter plate, followed by twofold serial dilutions across the plate to achieve a concentration range of 128–0.25 μg/mL. Then, 50 μL of the standardized bacterial suspension was added to each well, resulting in final test concentrations of 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, and 0.25 μg/mL.

The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h under static conditions. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the compound that completely inhibited visible bacterial growth. Growth inhibition was confirmed by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm using a SpectraMax® ABS Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, three prenylated indole diketopiperazines, spirotryprostatin H (1), fumitremorgin O (2) and fumitremorgin P (3), were isolated from marine-derived Penicillium sp. SCH3-Sd2. Their planar structures and absolute configurations were established via a comprehensive spectroscopic analysis, including NOESY, ECD, and the advanced Marfey’s method. Although compounds 1–3 exhibited only weak and selective antibacterial activity, the uncommon oxidation pattern and distinct prenylation features observed in these DKPs expand the structural diversity of the spirotryprostatin or fumitremorgin family. This study highlights the potential of marine-derived fungi as a valuable source of structurally unique indole alkaloids and provides a basis for further studies of their structure–activity relationship.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules31010149/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR Spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1) in DMSO-d6; Figure S2: 13C NMR Spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1) in DMSO-d6; Figure S3: COSY NMR Spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1) in DMSO-d6; Figure S4: HSQC NMR Spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1) in DMSO-d6; Figure S5: HMBC NMR Spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1) in DMSO-d6; Figure S6: NOESY NMR Spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1) in DMSO-d6; Figure S7: High resolution mass data of spirotryprostatin H (1); Figure S8: FT-IR spectrum of spirotryprostatin H (1); Figure S9: 1H NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2) in DMSO-d6; Figure S10: 13C NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2) in DMSO-d6; Figure S11: COSY NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2) in DMSO-d6; Figure S12: HSQC NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2) in DMSO-d6; Figure S13: HMBC NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2) in DMSO-d6; Figure S14: NOESY NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2) in DMSO-d6; Figure S15: High resolution mass data of fumitremorgin O (2); Figure S16: FT-IR spectrum of fumitremorgin O (2); Figure S17: 1H NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3) in DMSO-d6; Figure S18: 13C NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3) in DMSO-d6; Figure S19: COSY NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3) in DMSO-d6; Figure S20: HSQC NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3) in DMSO-d6; Figure S21: HMBC NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3) in DMSO-d6; Figure S22: NOESY NMR Spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3) in DMSO-d6; Figure S23: High resolution mass data of fumitremorgin P (3); Figure S24: FT-IR spectrum of fumitremorgin P (3); Figure S25: FT-IR spectrum of CHCl3 background signal; Table S1: ECD data of compounds 1–3; Table S2: NMR correlation data for compounds 1–3 in DMSO-d6; Figure S26: LC chromatograms of L and D-FDLA derivatives of proline from spirotryprostatin H (1); Figure S27: LC chromatograms of L and D-FDLA derivatives of proline from fumitremorgins O (2) and P (3); Figure S28: β-tubulin gene sequence of strain SCH3-Sd2.

Author Contributions

E.-Y.L. and Q.G. were involved in conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation. E.-Y.L. was responsible for compound isolation and absolute configuration. Q.G. was responsible for compound isolation. D.C. and G.C. were isolated the fungal strain. E.-Y.L., Q.G., H.T., P.F.H. and H.K. were responsible for writing—review and editing. K.-M.L. and S.-J.N. were project leaders guiding the chemical analysis experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion (KIMST) funded by Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (No. RS-2021-KS211520), National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2022R1A2C1011848), and the Ministry of Education (No. 2020R1A6C101B194 and No. 2021R1A6C101A442), as part of the Korea Basic Science Institute’s National Research Facilities and Equipment Center program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are contained within the manuscript and its Supporting Information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing financial interests. All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COSY | Correlated Spectroscopy |

| DKPs | Diketopiperazines |

| ECD | Electronic Circular Dichroism |

| HMBC | Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear Single-Quantum Correlation |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| NOESY | Nuclear Overhauser Effect |

| OSMAC | One strain−many compounds |

| PDB | Potato Dextrose Broth |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

References

- Schueffler, A.; Anke, T. Fungal natural products in research and development. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1425–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eze, P.M.; Liu, Y.; Simons, V.E.; Ebada, S.S.; Kurtán, T.; Király, S.B.; Esimone, C.O.; Okoye, F.B.; Proksch, P.; Kalscheuer, R. Two new metabolites from a marine-derived fungus Penicillium ochrochloron. Phytochem. Lett. 2023, 55, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, J.F. Natural products from marine fungi—Still an underrepresented resource. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugni, T.S.; Ireland, C.M. Marine-derived fungi: A chemically and biologically diverse group of microorganisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Mei, J.; Jiang, R.; Tu, S.; Deng, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J. Origins, structures, and bioactivities of secondary metabolites from marine-derived Penicillium fungi. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2000–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.-G.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, G.-L.; Liu, H.-S.; Zhu, W.-M. Marine natural products sourced from marine-derived Penicillium fungi. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 18, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, A.D. 2,5-Diketopiperazines: Synthesis, reactions, medicinal chemistry, and bioactive natural products. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3641–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Du, H.-F.; Liu, Y.-F.; Cao, F.; Luo, D.-Q.; Wang, C.-Y. Novel anti-inflammatory diketopiperazine alkaloids from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium brasilianum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, F.; Bills, G.F.; Durán-Patrón, R. Strategies for the discovery of fungal natural products. Front. Media SA 2022, 13, 897756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Jackson, S.A.; Patry, S.; Dobson, A.D. Extending the “one strain many compounds”(OSMAC) principle to marine microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.M.R.; Paggi, G.M.; Brust, F.R.; Macedo, A.J.; Silva, D.B. Metabolomic strategies to improve chemical information from OSMAC studies of endophytic fungi. Metabolites 2023, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.-B.; Kakeya, H.; Osada, H. Novel mammalian cell cycle inhibitors, spirotryprostatins A and B, produced by Aspergillus fumigatus, which inhibit mammalian cell cycle at G2/M phase. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12651–12666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, W.-J.; Fang, C.-H.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; Lv, M.-J.; Yue, J.-M.; Yu, J.-H. Indole diketopiperazine alkaloids from a soil-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. KYS-11. Fitoterapia 2025, 185, 106697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Fang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, M.; Lin, A.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, W. Seven new prenylated indole diketopiperazine alkaloids from holothurian-derived fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 7986–7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Fujimoto, H.; Kawasaki, T. The structure of a tremorgenic metabolite from Aspergillus fumigatus fres., fumitremorgin a. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Gao, H.; Li, J.; Ai, J.; Geng, M.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Prenylated indole diketopiperazines from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 7895–7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, A.E.; Sherman, D.H. Enzyme evolution in fungal indole alkaloid biosynthesis. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 1381–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgman, P.; Lopez, R.D.; Lane, A.L. The expanding spectrum of diketopiperazine natural product biosynthetic pathways containing cyclodipeptide synthases. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, R.; Brückner, H. Marfey’s reagent for chiral amino acid analysis: A review. Amino Acids 2004, 27, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H.; Su, Z.; Liu, D.; Jie, L.; He, F. Antibacterial spirooxindole alkaloids from Penicillium brefeldianum inhibit dimorphism of pathogenic smut fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1046099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Shang, Z.-C.; Yu, P.; Luo, J.; Jian, K.-L.; Kong, L.-Y.; Yang, M.-H. Alkaloids from the endophytic fungus Penicillium brefeldianum and their cytotoxic activities. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lin, D.; Yang, L.; Li, F.; Yang, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X. Four novel alkaloids from Aspergillus fumigatus and their antimicrobial activities. Fitoterapia 2025, 185, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgurskaya, H.I.; López, C.A.; Gnanakaran, S. Permeability barrier of Gram-negative cell envelopes and approaches to bypass it. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štumpf, S.; Hostnik, G.; Primožič, M.; Leitgeb, M.; Salminen, J.-P.; Bren, U. The effect of growth medium strength on minimum inhibitory concentrations of tannins and tannin extracts against E. coli. Molecules 2020, 25, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, A.; Seepersaud, M.; Maxwell, A.; Jayaraman, J.; Ramsubhag, A. Isolation and antibacterial activity of indole alkaloids from Pseudomonas aeruginosa UWI-1. Molecules 2020, 25, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Baek, K.; Bae, S.S.; Jung, J. Identification and characterization of a marine-derived chitinolytic fungus, Acremonium sp. YS2-2. J. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-J.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Isolation and characterization of actinoramides A–C, highly modified peptides from a marine Streptomyces sp. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 6707–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.