A Biopolymer System Based on Chitosan and an Anisotropic Network of Nickel Fibers in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

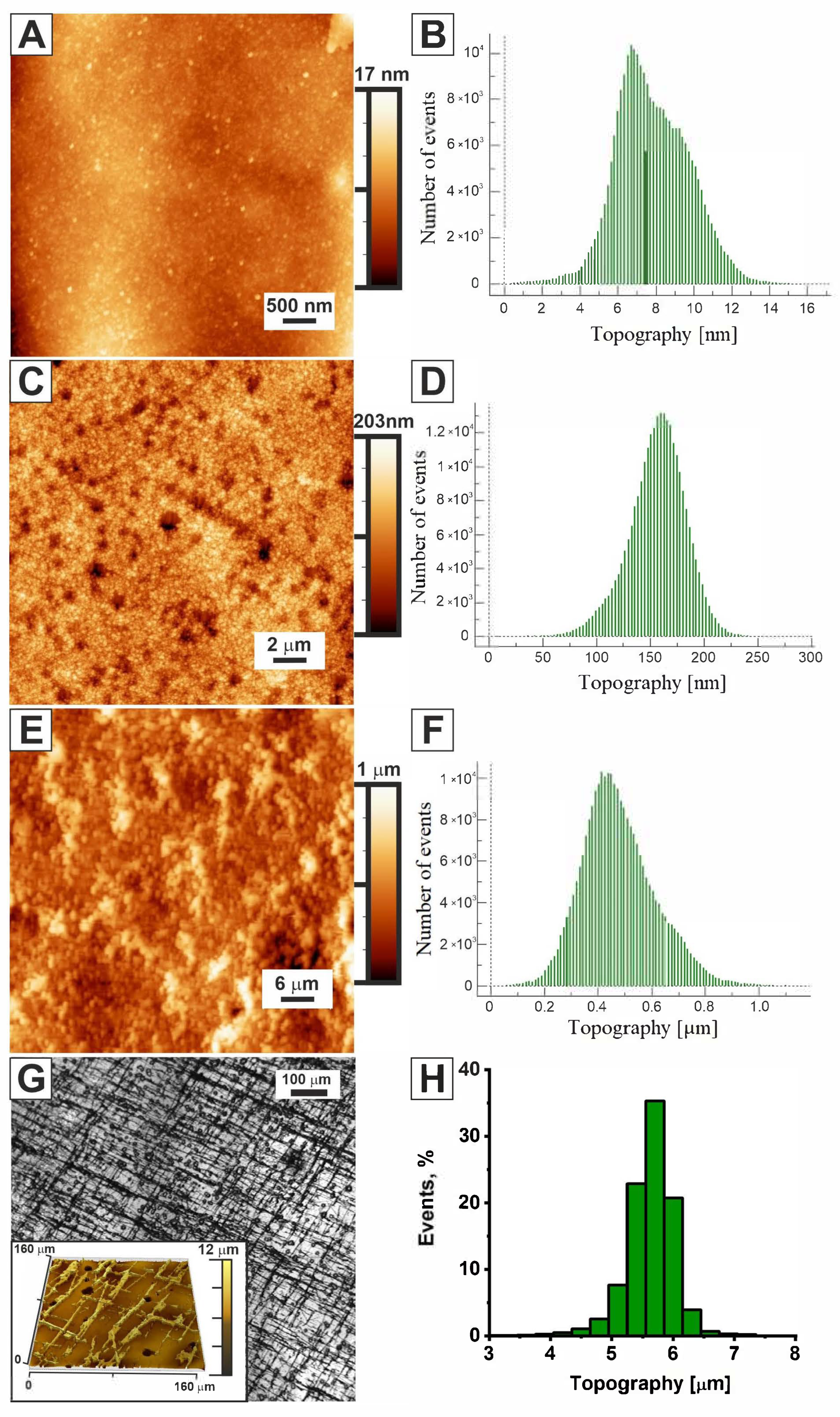

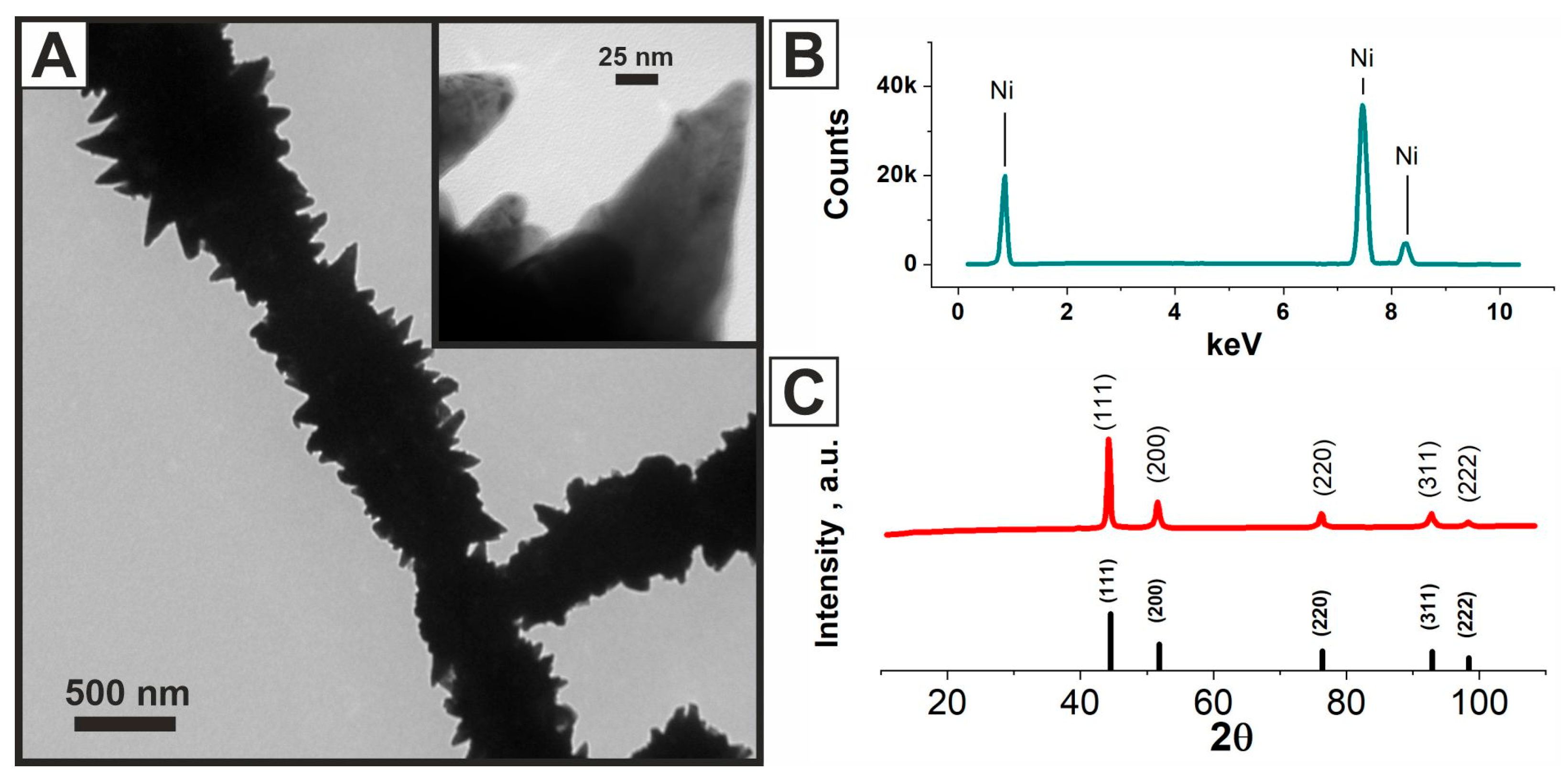

2.1. Morphology of Chitosan, Chitosan/Ni, and Chitosan/Ni + NiFs

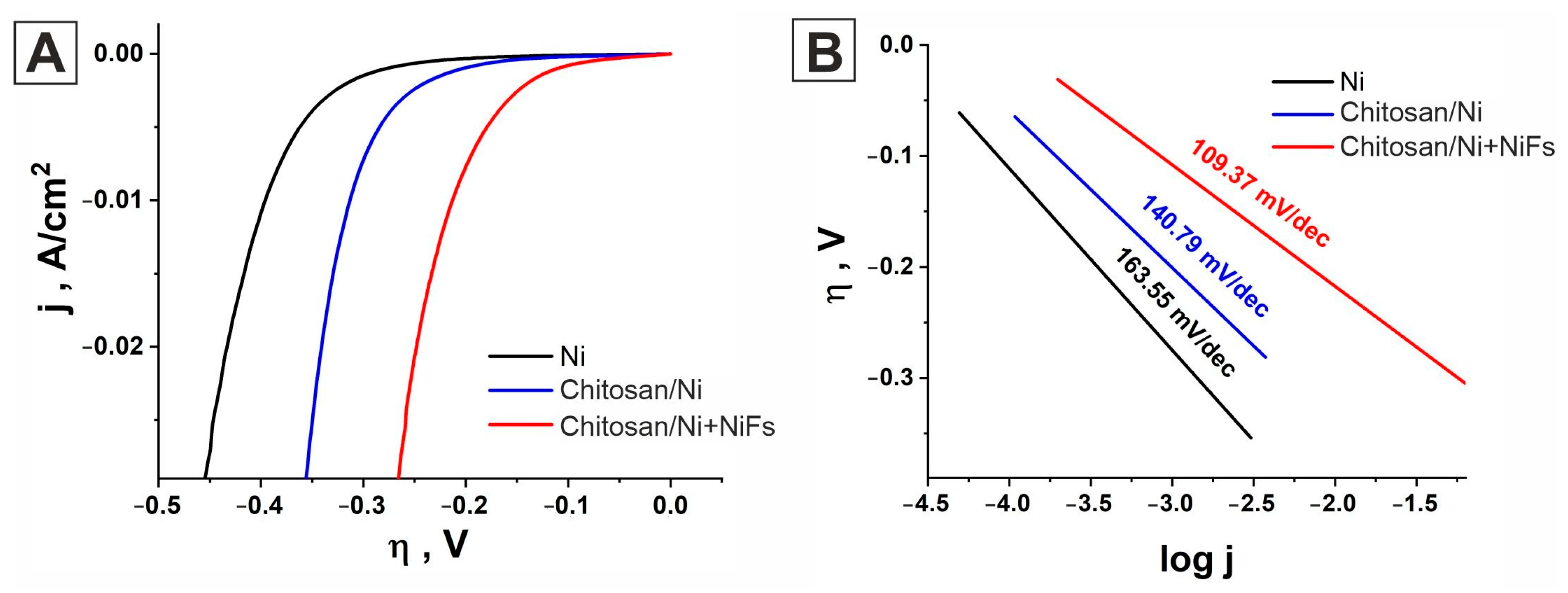

2.2. Linear Sweep Voltammetry

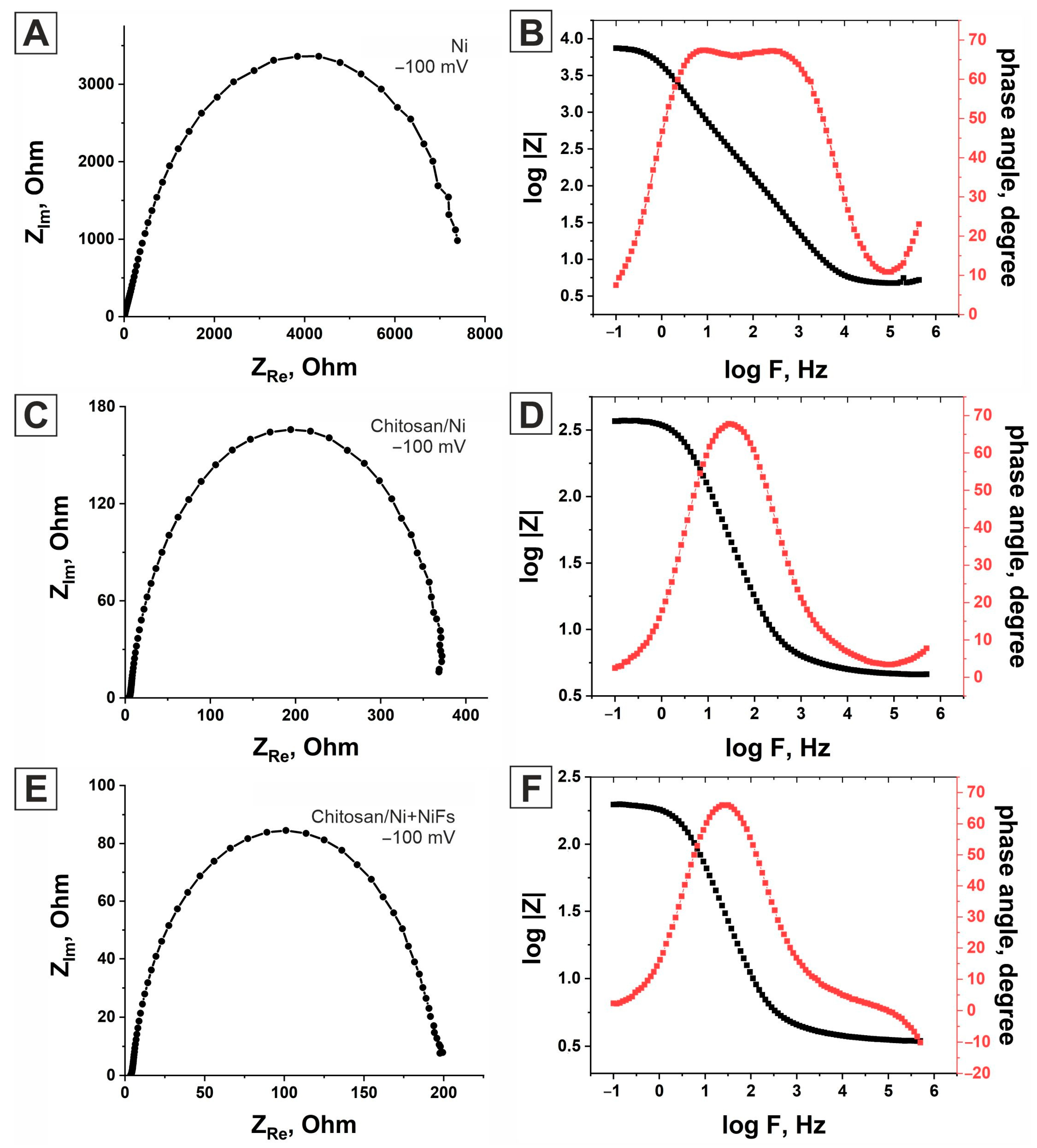

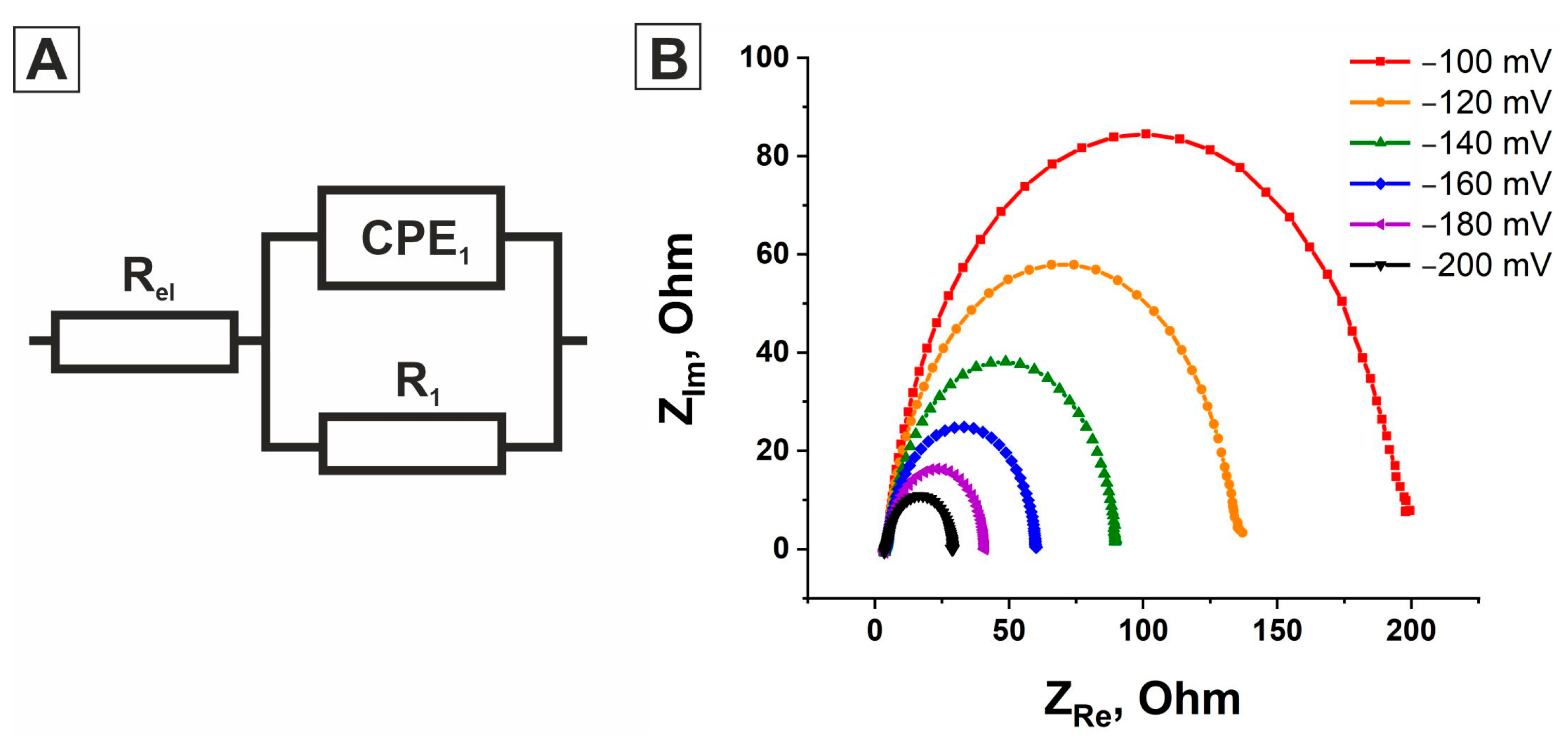

2.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

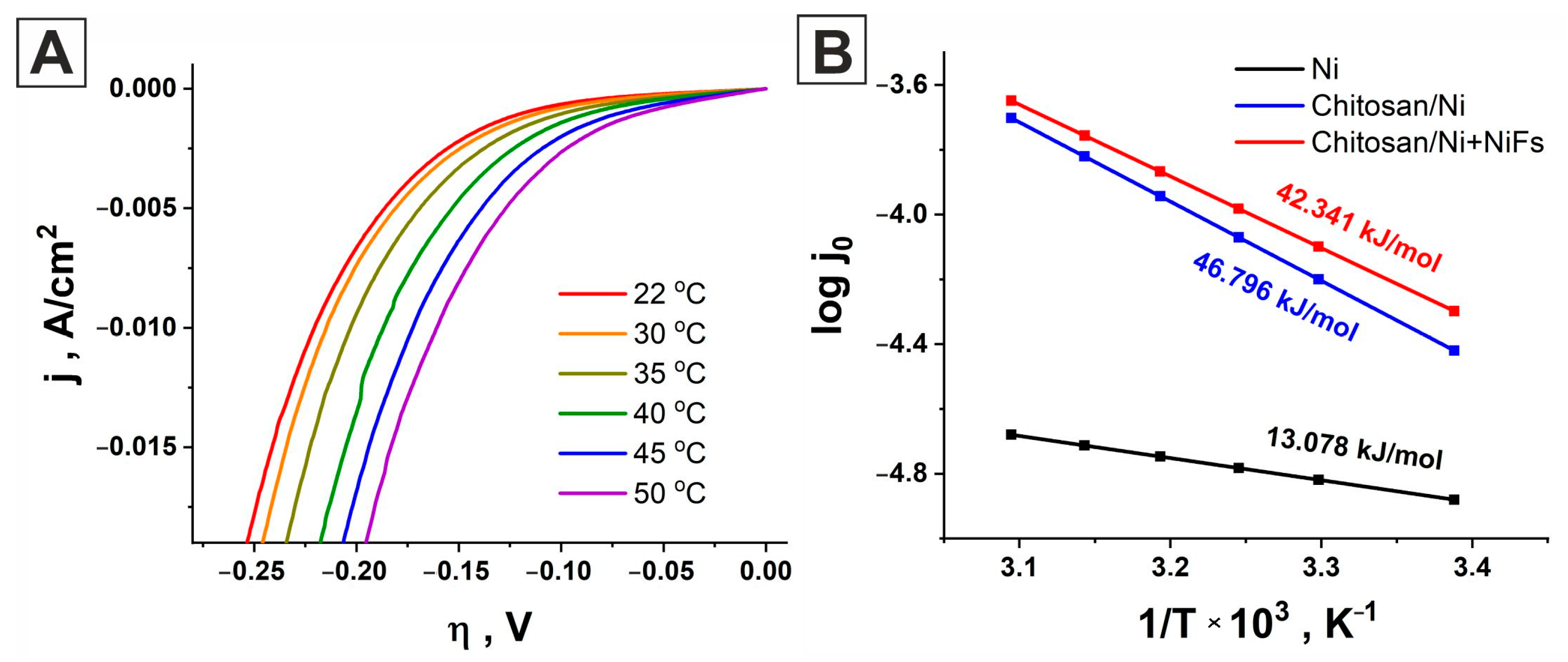

2.4. Activation Energy

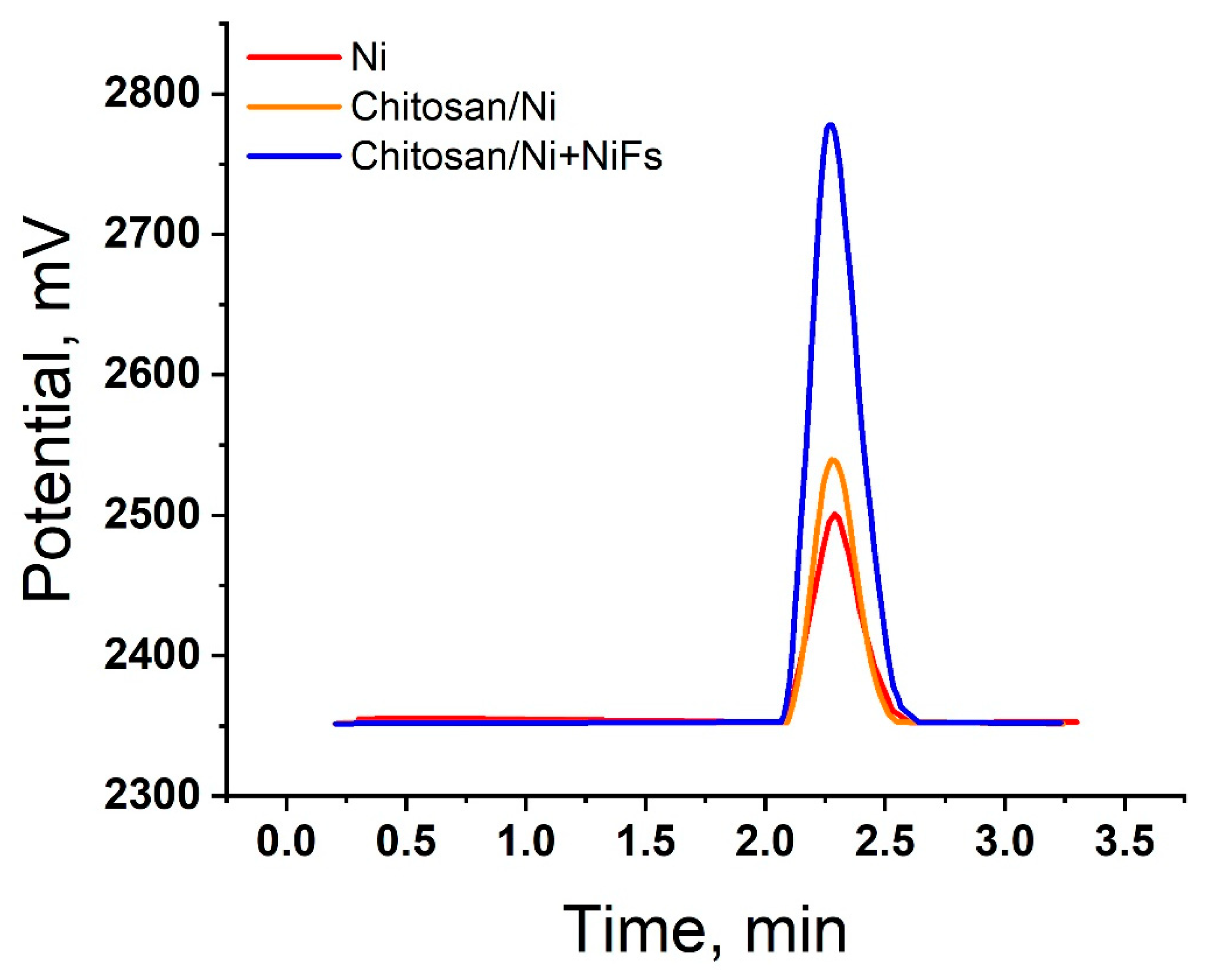

2.5. Gas Chromatography

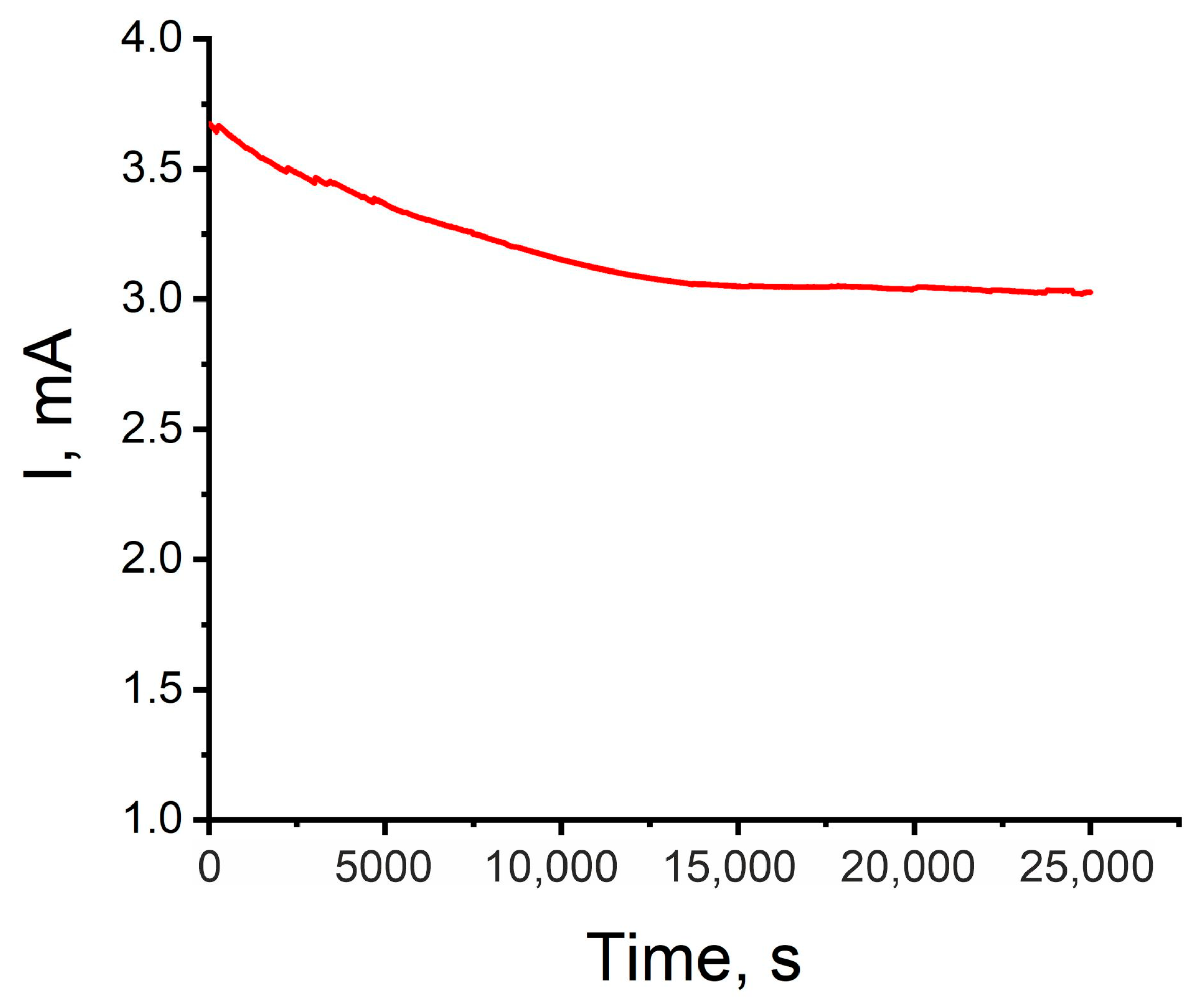

2.6. Stability Test

3. Experimental Section

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HER | Hydrogen evolution reaction |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| LSV | Linear sweep voltammetry |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| EEC | Electrical equivalent circuit |

| CPE | Constant-phase element |

| EP | Equilibrium potential |

| FRA | Frequency response analysis |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

| GC | Glassy carbon |

References

- Qin, X.; Ola, O.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Tiwari, S.K.; Wang, N.; Zhu, Y. Recent progress in graphene-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Liao, W.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H. Recent Advances in Non-Noble Metal Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Water Splitting. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Youn, D.H. A review of stoichiometric nickel sulfide-based catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media. Molecules 2024, 29, 4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; He, Y.; Wang, B.; Peng, S.; Tong, L.; Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Tang, H. PtNi alloy coated in porous nitrogen-doped carbon as highly efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution reactions. Molecules 2022, 27, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhan, G. Ru and Se co-doped cobalt hydroxide electrocatalyst for efficient hydrogen evolution reactions. Molecules 2023, 28, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Aepuru, R.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J. Advances in catalysts for hydrogen production: A comprehensive review of materials and mechanisms. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiao, M.; Ye, C. Single-Atom Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: The Role of Supports, Coordination Environments, and Synergistic Effects. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, P.; He, M.; Yang, C.; Li, Z. Rare Earth-Based Alloy Nanostructure for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Catalysis 2023, 13, 13804–13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Hu, X. Nanoporous Ni3S2 film on Ni foam as highly efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution in acidic electrolyte. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2019, 55, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.J. Impact of surface area in evaluation of catalyst activity. Joule 2018, 2, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Han, M.Y.; Xu, Z.J. Size effects of electrocatalysts: More than a variation of surface area. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 8531–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüksel, H.; Özbay, A.; Solmaz, R.; Kahraman, M. Fabrication and characterization of three-dimensional silver nanodomes: Application for alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 2476–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ao, K.; Lv, P.; Wei, Q. MoS2 coexisting in 1T and 2H phases synthesized by common hydrothermal method for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Lam, N.D.; Linh, D.C.; Mai, N.T.; Chang, H.; Han, S.H.; Oanh, V.T.K.; Pham, A.T.; Patil, S.A.; Tung, N.T.; et al. Escalating catalytic activity for hydrogen evolution reaction on MoSe2@ graphene functionalization. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Rabani, I.; Vikraman, D.; Feroze, A.; Ali, M.; Seo, Y.S.; Kim, H.S.; Chun, S.H.; Jung, J. One-pot synthesis of W2C/WS2 hybrid nanostructures for improved hydrogen evolution reactions and supercapacitors. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, S.; Shah, S.A.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, N.; Yuan, A. Synthesis of Fe2O3 nanorod and NiFe2O4 nanoparticle composites on expired cotton fiber cloth for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. Molecules 2024, 29, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Fang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Tian, J. Enhanced Electrocatalytic Performance of P-Doped MoS2/rGO Composites for Hydrogen Evolution Reactions. Molecules 2025, 30, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yao, J.; Meng, S.; Wang, P.; He, M.; Li, P.; Xiao, P.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. A Library of Polymetallic Alloy Nanotubes: From Binary to Septenary. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 9865–9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Zhang, L.; Luo, L.; Lu, J.; Yin, S.; Shen, P.K.; Tsiakaras, P. N-doped porous molybdenum carbide nanobelts as efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 224, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cheng, J.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhou, J. Facet-tunable coral-like Mo2C catalyst for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, B.; Meng, C.; Shi, F.; Yuan, A.; Miao, W.; Zhou, H. Coupling NiSe2 nanoparticles with N-doped porous carbon enables efficient and durable electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction at pH values ranging from 0 to 14. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 7, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wu, A.; Jiao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Tian, C.; Fu, H. Two-dimensional porous molybdenum phosphide/nitride heterojunction nanosheets for pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6673–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Chan, K.C.; Lu, Z. Design of hierarchical porosity via manipulating chemical and microstructural complexities in high-entropy alloys for efficient water electrolysis. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, P.; Dou, M.; Niu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F. Promotion of hydrogen evolution catalysis by ordered hierarchically porous electrodes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 2997–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fei, Y.; Chen, J.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, L.Y.; Guo, C.X.; Li, C.M. Directionally in situ self-assembled, high-density, macropore-oriented, CoP-impregnated, 3D hierarchical porous carbon sheet nanostructure for superior electrocatalysis in the hydrogen evolution reaction. Small 2022, 18, 2103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Wan, S.; Kuang, P.; Cheng, B.; Yu, L.; Yu, J. Crystalline/amorphous Ni/NixSy supported on hierarchical porous nickel foam for high-current-density hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 340, 123195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Huang, A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Wu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Fu, Y.; Wen, M. Two-dimensional hetero-nanostructured electrocatalyst of Ni/NiFe-layered double oxide for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline medium. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghubayra, R.; Shariq, M.; Sadaf, S.; Almuhawish, N.F.; Iqbal, M.; Alam, M.W. Constructing a hybrid CuO over bimetallic spinal NiCo2O4 nanoflower as electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; He, R.; Wu, H.; Ding, Y.; Mei, H. Needle-like CoP/rGO growth on nickel foam as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 9690–9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.K.; Sharma, V.; Mishra, S.; Kulshrestha, V. MoS2 quantum dot-modified MXene nanoflowers for efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2024, 1, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.P.D.S.; Dourado, A.H.; Cutolo, L.D.O.; Parreira, L.S.; Alves, T.V.; Slater, T.J.; Haigh, S.J.; Camargo, P.H.C.; Cordoba de Torresi, S.I. Gold–rhodium nanoflowers for the plasmon-enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction under visible light. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13543–13555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, J.; Tao, S.; Gan, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Su, H.; Shen, R.; Tang, H.; Wu, G. Atomic-Scale Platinum Catalysts via Electron-Beam Irradiation: A Strategy for Robust Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Langmuir 2025, 41, 22492–22500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Jiang, S.; Fu, L.; Chang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Wu, G. Atomic-Level Dispersed Pt on Vulcan Carbon Black Prepared by Electron Beam Irradiation as a Catalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 22011–22021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, T.; Fortunelli, A.; Chen, C.Y.; Yu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, L.; Merinov, B.V.; Lin, Z.; et al. Ultrafine jagged platinum nanowires enable ultrahigh mass activity for the oxygen reduction reaction. Science 2016, 354, 1414–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Shang, H.; Wang, C.; Du, Y. Ultrafine Pt-based nanowires for advanced catalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Cai, M.; Balogh, M.P.; Tessema, M.M.; Lu, Y. Symmetric growth of Pt ultrathin nanowires from dumbbell nuclei for use as oxygen reduction catalysts. Nano Res. 2012, 5, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Gong, B.; Xiao, K.; Wang, L. In situ assembly of ultrathin PtRh nanowires to graphene nanosheets as highly efficient electrocatalysts for the oxidation of ethanol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 3535–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalwadi, S.; Goel, A.; Kapetanakis, C.; Salas-de la Cruz, D.; Hu, X. The integration of biopolymer-based materials for energy storage applications: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalaya, I.; Alves, G.; Lopes, J.; Silva, L.R. A review of natural polysaccharides: Sources, characteristics, properties, food, and pharmaceutical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Xie, K.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Tan, X.; Dong, H.; Li, X.; Dong, Z.; Xia, Q.; et al. Chitin and cuticle proteins form the cuticular layer in the spinning duct of silkworm. Acta Biomater. 2022, 145, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, M.; Perumal, V.; Karuppanan, S.; Ovinis, M.; Bothi Raja, P.; Gopinath, S.C.; Immanuel Edison, T.N.J. A comprehensive review on biopolymer mediated nanomaterial composites and their applications in electrochemical sensors. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 1871–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallam, G.S.; Sam, S.; S, S.; Kumar, K.G. A sensitive voltammetric sensor for the simultaneous determination of norepinephrine and its co-transmitter octopamine using a biopolymer modified glassy carbon electrode. Ionics 2023, 29, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Hasan, K.; Imran, A.B. Biopolymers for Supercapacitors. In Bio-Based Polymers: Farm to Industry; Gupta, R.K., Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.B.; Nofal, M.M.; Abdulwahid, R.T.; Kadir, M.F.Z.; Hadi, J.M.; Hessien, M.M.; Kareem, W.O.; Dannoun, E.M.A.; Saeed, S.R. Impedance, FTIR and transport properties of plasticized proton conducting biopolymer electrolyte based on chitosan for electrochemical device application. Results Phys. 2021, 29, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuhile, A.; Pein, P.S.; Barım, Ş.B.; Bozbağ, S.E.; Smirnova, I.; Erkey, C.; Schroeter, B. Synthesis of Pt Carbon Aerogel Electrocatalysts with Multiscale Porosity Derived from Cellulose and Chitosan Biopolymer Aerogels via Supercritical Deposition for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2400433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayan, D.B.; İlhan, M.; Koçak, D. Chitosan-based hybrid nanocomposite on aluminium for hydrogen production from water. Ionics 2018, 24, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, M.T.; Sarilmaz, A.; Aslan, E.; Ozel, F.; Potrich, C.; Ersoz, M.; Patir, I.H. Biopolymer supported silicon carbide for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 316, 122019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayan, D.B.; Koçak, D.; İlhan, M. The activity of PAni-Chitosan composite film decorated with Pt nanoparticles for electrocatalytic hydrogen generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 10522–10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, K.E.; Modibane, K.D.; Ndipingwi, M.M.; Makhado, E.; Hato, M.J.; Raseale, S.; Makgopa, K.; Iwuoha, E.I. The effect of copolymerization on the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution properties of polyaniline in acidic medium. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Lyczko, N.; Gopakumar, D.; Maria, H.J.; Nzihou, A.; Thomas, S. Chitin and chitosan based composites for energy and environmental applications: A review. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 4777–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A natural biopolymer with a wide and varied range of applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanmani, P.; Aravind, J.; Kamaraj, M.; Sureshbabu, P.; Karthikeyan, S. Environmental applications of chitosan and cellulosic biopolymers: A comprehensive outlook. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 242, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshipour, S.; Hadidi, M.; Gholipour, O. A Review on Hydrogen Generation by Photo-, Electro-, and Photoelectro-Catalysts Based on Chitosan, Chitin, Cellulose, and Carbon Materials Obtained from These Biopolymers. Adv. Polym. Tech. 2023, 2023, 8835940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sahai, Y. Chitosan biopolymer for fuel cell applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 955–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chi, B.Y.; Yang, T.Y.; Ren, W.F.; Gao, X.J.; Wang, K.H.; Sun, R.C. Natural biopolymers derived kinematic and self-healing hydrogel coatings to continuously protect metallic zinc anodes. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 489, 144238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Rahman, G.; Nguyen, T.M.; Shah, A.U.H.A.; Pham, C.Q.; Tran, M.X.; Nguyen, D.L.T. Recent development of nanostructured nickel metal-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction: A review. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 149–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Chen, H.; Feng, H. Room-temperature synthesis of sub-2 nm ultrasmall platinum-rare-earth metal nanoalloys for hydrogen evolution reaction. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 13379–13385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojîncă, R.; Muntean, R.; Crişan, R.; Kellenberger, A. Nickel Electrocatalysts Obtained by Pulsed Current Electrodeposition from Watts and Citrate Baths for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Media. Materials 2025, 18, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Wu, Y.; Ren, S. Se doping regulates the activity of NiTe2 for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 26793–26800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Castany, R.; Eiler, K.; Nicolenco, A.; Lekka, M.; García-Lecina, E.; Brunin, G.; Rignanese, G.; Waroquiers, D.; Collet, T.; Hubin, A.; et al. Hydrogen Evolution Reaction of Electrodeposited Ni-W Films in Acidic Medium and Performance Optimization Using Machine Learning. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202400444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nizameev, I.R.; Nizameeva, G.R.; Faizullin, R.R.; Kadirov, M.K. Oriented Nickel Nanonetworks and Their Submicron Fibres as a Basis for a Transparent Electrically Conductive Coating. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizameev, I.R.; Nizameeva, G.R.; Kadirov, M.K. Doping of Transparent Electrode Based on Oriented Networks of Nickel in Poly (3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene) Polystyrene Sulfonate Matrix with P-Toluenesulfonic Acid. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | b, mV/dec | jo, A/cm2 | α | η, mV at 10 mA/cm2 | j, μA/cm2 at −150 mV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | 163.55 | 2.09 × 10−5 | 0.361 | −396 | 163.5 |

| Chitosan/Ni | 140.78 | 3.76 × 10−5 | 0.419 | −317 | 405.56 |

| Chitosan/Ni + NiFs | 109.37 | 10.308 × 10−5 | 0.539 | −213 | 2608 |

| Pt-Tb/C [57] | 23.3 | - | - | −24 | - |

| Ni-PGE [58] | 208 | - | - | −210 | - |

| Se12%-NiTe2 [59] | 38 | - | - | 375 | - |

| Ni-W Films [60] | 186 | - | - | 363 | - |

| Ni | Chitosan/Ni | Chitosan/Ni + NiFs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overpotential, mV | R1, Ohm | CPE, μF∙Sn−1∙cm−2 | R1, Ohm | CPE, μF∙Sn−1∙cm−2 | R1, Ohm | CPE, μF∙Sn−1∙cm−2 |

| 100 | 8691.4 | 27.76 | 373 | 174 | 193.56 | 294.02 |

| 120 | 4473.4 | 27.96 | 203.13 | 191.29 | 131.45 | 299.11 |

| 140 | 2913 | 27.023 | 124.19 | 193.28 | 86.044 | 305.75 |

| 160 | 1878 | 27.385 | 76.076 | 204.85 | 56.191 | 304.42 |

| 180 | 1270 | 29.369 | 47.035 | 219.95 | 37.23 | 317.18 |

| 200 | 766 | 29.43 | 30.406 | 244.75 | 25.121 | 332.32 |

| Catalyst | CDL, F/cm2 | σ | j/σ, μA/cm2 (at −150 mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | 3.5 × 10−5 | 1.6 | 102 |

| Chitosan/Ni | 42.4 × 10−5 | 21.2 | 19 |

| Chitosan/Ni + NiFs | 66.8 × 10−5 | 33.4 | 78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nizameeva, G.R.; Lebedeva, E.M.; Vorobieva, V.V.; Soloviev, E.A.; Sarimov, R.M.; Nizameev, I.R. A Biopolymer System Based on Chitosan and an Anisotropic Network of Nickel Fibers in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Molecules 2026, 31, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010150

Nizameeva GR, Lebedeva EM, Vorobieva VV, Soloviev EA, Sarimov RM, Nizameev IR. A Biopolymer System Based on Chitosan and an Anisotropic Network of Nickel Fibers in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleNizameeva, Guliya R., Elgina M. Lebedeva, Viktoria V. Vorobieva, Evgeniy A. Soloviev, Ruslan M. Sarimov, and Irek R. Nizameev. 2026. "A Biopolymer System Based on Chitosan and an Anisotropic Network of Nickel Fibers in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction" Molecules 31, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010150

APA StyleNizameeva, G. R., Lebedeva, E. M., Vorobieva, V. V., Soloviev, E. A., Sarimov, R. M., & Nizameev, I. R. (2026). A Biopolymer System Based on Chitosan and an Anisotropic Network of Nickel Fibers in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Molecules, 31(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010150