Abstract

Quartz is capable of capturing heavy metals (HMs); however, alkaline metals compete with HMs for active adsorption sites during coal combustion. Therefore, this study investigated the influence of alkaline metals (Na2CO3, NaCl, and CaO) on the adsorption behavior of HMs (Pb, Cd, Cu, and Zn) onto quartz via tube furnace combustion experiments and the CASTEP module based on density functional theory (DFT). The results showed that the addition of Na2CO3 and NaCl was disadvantageous for the retention of HMs in the ash, particularly NaCl. With the increase in NaCl from 0 to 5 wt%, the immobilization efficiencies for Pb and Cd progressively declined from 33.99% and 37.78% to 9.89% and 12.04%, respectively. As the temperature increased from 800 °C to 1200 °C, the fixation rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd decreased by 19.96%, 27.75%, 23.35%, and 20.68%, respectively, when Na2CO3 was present in the coal. The results of the DFT demonstrated that the adsorption energy of alkali metals on quartz-α(001) surfaces was much greater than that of HMs, thus adversely affecting the adsorption of HMs. The adsorption energy of Na2O reached as high as −924.70 kJ/mol, while that of HMs was generally below −650 kJ/mol. This work contributed to a deeper understanding of the fate, migration, and transformation of HMs, thereby facilitating the mitigation of HMs release and subsequent associated ecological risks.

1. Introduction

In 2021, China’s overall energy consumption reached 5.24 billion tons of standard coal, with coal remaining the predominant source [1]. Although the composition of coal varies in different regions, they all present the risk of heavy metals (HMs) being released during combustion [2,3,4,5]. Semi-volatile HMs such as Pb, Cd, Cu, and Zn have garnered significant interest in recent years owing to their intricate transport mechanisms than those of high-volatile and non-volatile HMs [6,7,8]. HMs are not only a serious threat to human health, but also weaken the ability of catalysts to remove pollutants such as chlorinated volatile organic compounds and nitric oxides [9,10]. Therefore, it is essential to explore the control mechanism of HMs at high temperatures, in which mineral sorbents are promising in reducing the hazard of HMs [11,12].

Quartz (SiO2) is widely found in coal and could trap HMs vapors at high temperatures [13,14,15,16]. For example, Yu et al. [17] examined the adsorption capacity of the primary oxides found in coal on PbO at a temperature of 900 °C, and the results showed that the adsorption capacity of SiO2 on PbO was much higher than that of Fe2O3, Al2O3, CaO, and MgO, and the controlling effectiveness of SiO2 on Pb demonstrated an initial propensity to rise followed by a subsequent decline within the range of 700~1200 °C. Furthermore, the adsorption performance of SiO2 on Cd, Cu, and Zn has been widely reported by scholars [18,19,20]. However, these findings were constrained in scope, as they failed to account for the influence of other mineral-related components (e.g., alkaline metals) on the control of HMs release.

In recent years, numerous investigations have been conducted on the co-combustion of coal alongside alternative fuels, e.g., sludge, municipal waste, biomass, etc., which may increase the content of alkaline metals in the combustion system [21,22,23]. In addition, the high-alkaline coal in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China is often used in the process of coal blending combustion, due to the problems of slagging and ash deposition caused by its individual combustion, which would also introduce a certain amount of alkaline metals (Na and Ca), with the content of Ca being more significant [24,25,26].

Numerous studies have appeared related to the effect of alkaline Na and Ca species on the transport and transformation of HMs. For example, Liu et al. [27] investigated the migration and transformation characteristics of Pb, Zn, and Cu with the addition of NaCl to sludge using a tube furnace, and found that Pb largely existed in the form of PbCl2 (g) in the gas phase. Ca-based compounds also influence the behavior of HMs during combustion. Zha et al. [28] found that CaO promoted the evaporation of Cu from sludge in the range from 600 to 1100 °C, but increased the fixation rate of Zn at higher temperatures, and assumed that Ca could form eutectic silica-aluminate with Zn. It can be observed that existing studies primarily employ the approach of directly adding additives to the fuel. However, the inorganic components in fuel are often highly complex, which introduces numerous interfering factors, thereby increasing the uncertainty of experimental results. Accordingly, this study adopts a method that eliminates the interference of inherent minerals in coal, aiming to more rigorously elucidate the effect of variations in Na and Ca contents on the immobilization of HMs by quartz during coal combustion.

To better understand the effects and mechanisms of alkaline metals on HMs adsorption by SiO2, in this study, the raw coal was pre-treated using the HCl-HF method, which removed most of the minerals in the coal, and the impact on the primary organic framework of the unprocessed coal was negligible [29,30]. Then, SiO2, trace HMs, and alkaline metals were loaded into the demineralized coal at a certain content, so that the experimental coal was obtained. Accordingly, this study aimed to (1) quantify the influence of NaCl, Na2CO3, and CaO on the retention and chemical forms of Pb, Cd, Cu, and Zn during combustion of quartz-dominated coal; (2) elucidate the effects of temperature on HMs volatilization and stabilization; (3) analyze the microstructure and crystalline phase composition of coal fly ash; and (4) use density functional theory (DFT) methods to clarify the competitive adsorption mechanisms between alkaline metals and HMs on quartz surfaces.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. HMs Behavior with Different Ratios of Alkaline Metals

2.1.1. Fixation Rates of HMs

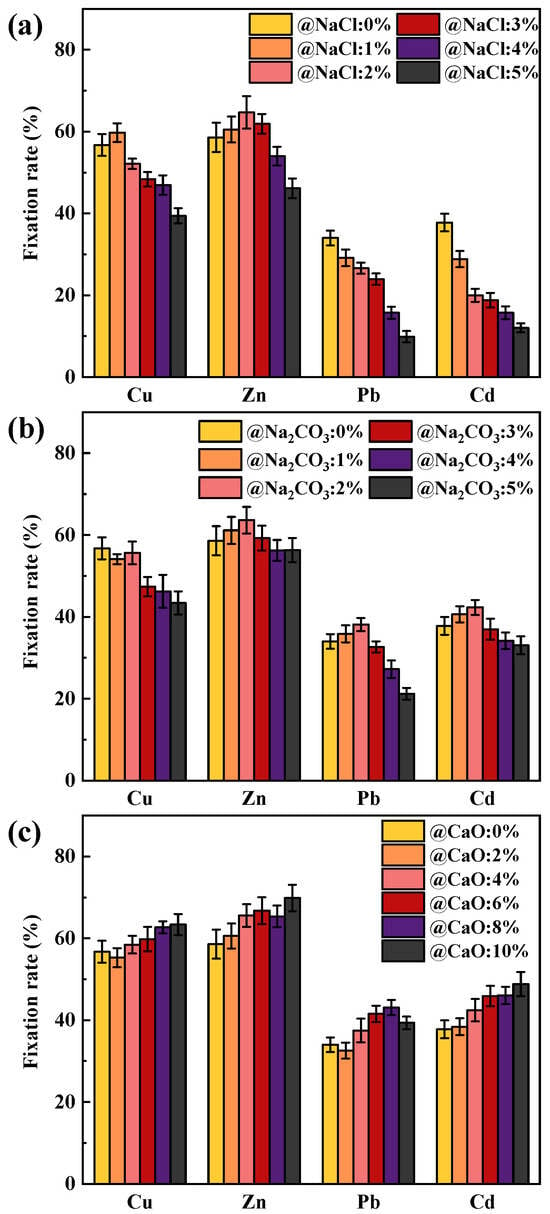

The immobilization rates of HMs during the combustion of coal, primarily made up of SiO2 and loaded with alkaline metals at 1000 °C, are depicted in Figure 1. When coal was free of alkaline metals, the immobilization rates for Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd were 56.72%, 58.60%, 33.99%, and 37.78%, respectively. Since PbO and CdO oxides exhibited lower boiling and melting points compared to CuO and ZnO, they were more easily released into the atmosphere at high temperatures, resulting in relatively lower fixation rates than Pb and Cd [31].

Figure 1.

Effect of Na and Ca content on the immobilization rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd: (a) NaCl; (b) Na2CO3; (c) CaO.

The effect of NaCl content on the HMs immobilization rate of SiO2-dominated coal is shown in Figure 1a. With the increase in NaCl addition, the fixation rates of Pb and Cd progressively decreased to 9.89% and 12.04% (@NaCl 5 wt%), respectively, whereas Cu and Zn displayed an elevated and then reduced trend. It was found that NaCl addition affected Pb and Cd to a greater extent than Cu and Zn. The decrease in the fixation rate of HMs was mainly attributed to the formation of low-melting-point chlorinated HMs and the competition between Na and HMs for the active sites. Chlorinated HMs may be formed through two reaction paths when SiO2, NaCl and oxidized HMs were co-present in the system [32]. On the one hand, NaCl and SiO2 react to form Na-containing silicates with the release of Cl2 or HCl, with the reaction formulae Equations (1) and (2) in the presence of oxygen and moisture. Then, Cl2 and HCl react with oxidized HMs to form chlorinated HMs in the reaction Equations (3) and (4), where M represents HMs. On the other hand, oxidized HMs can react with SiO2 to form HMs-containing silicates, Equations (5) and (6). Then, NaCl participated in the chlorination reaction, Equation (7). SiO2 could also chemisorb chlorinated HMs, with H2O and O2 playing a contributing role, Equations (8) and (9). However, Wang et al. [16] concluded that the inhibitory effect of SiO2 on the release of chlorinated HMs was not obvious in high-temperature adsorption experiments. Therefore, the fixation rate of HMs after NaCl addition demonstrated a more noticeable decreasing trend.

The effect of Na2CO3 content on the immobilization rate of HMs is shown in Figure 1b. The effect of Na2CO3 on the fixation rate of HMs was divided into two stages. The immobilization rate of Cu remained stable, while the fixation rates of Pb, Zn, and Cd were slightly increased when the Na2CO3 content was 1% and 2%. However, a decreasing trend in the immobilization rates of Zn, Pb, Cu, and Cd was observed at 3%, 4%, and 5% Na2CO3 content, which may result from the change in the physicochemical properties of the mineral after the capture of Na by the SiO2. Na2CO3 decomposed at high temperatures to gaseous Na2O, which reacted with SiO2 in a process that may proceed in the form of Equation (10) and Equation (11) to form low-melting Na-containing silicates [33]. Since the Na2CO3 content was relatively low, the mineral surface was in the early stages of melting, and capture of HMs was favored. However, the melting of the minerals intensified as the Na2CO3 content increased, at which point the minerals became completely deactivated, resulting in an increased release of HMs [34]. Therefore, it was the excessive Na2CO3 content (above 3%) that showed a more pronounced decrease in the fixation rate of HMs.

Figure 1c illustrates the impact of CaO content on the fixation rate of HMs. The fixation rate of HMs gradually increased with the addition of CaO content, indicating that the addition of CaO was favorable to immobilize more HMs in the coal ash. It is important to note that the reaction of CaO with SiO2 theoretically results in a reduction in active sites, reactions Equations (12) and (13), which hinder the fixation of HMs in the ash. The increase in the fixation rate of HMs may be due to the fact that SiO2, after chemisorption of CaO, does not seriously affect the subsequent adsorption of HMs, and CaO fixes the HMs by physical adsorption.

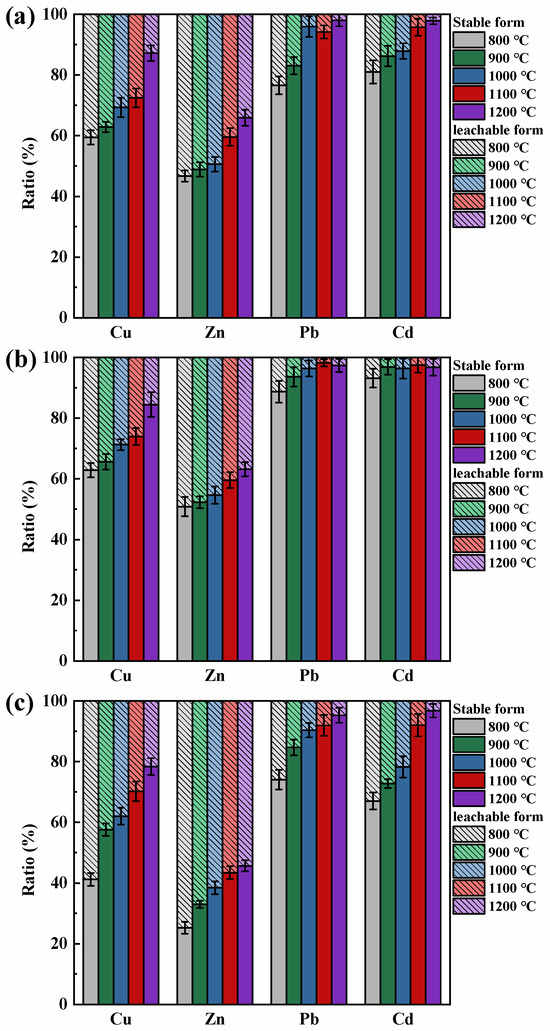

2.1.2. HMs Leaching Behavior

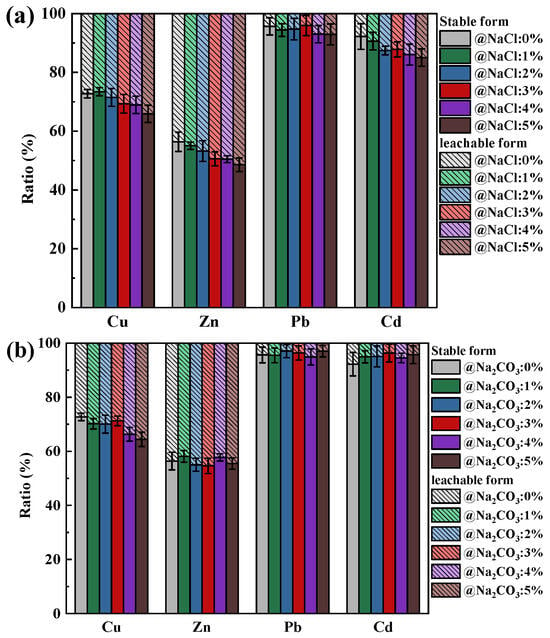

The effect of changes in Na and Ca content on the leaching behavior of HMs forms in coal ash is shown in Figure 2. After the combustion of SiO2-dominated coal, the percentage of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd in the stable form was 72.73%, 56.39%, 95.66%, and 92.21%, respectively. Since the oxides of Pb and Cd were more readily released in gaseous form than Cu and Zn, most of the Pb and Cd retained in the ash was in the form of stable silicates, and thus a relatively large proportion of Pb and Cd was present in stable form.

Figure 2.

Effect of Na and Ca contents on the leaching behavior of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd in ash: (a) NaCl; (b) Na2CO3; (c) CaO.

It can be found that as the content of NaCl and Na2CO3 in SiO2-dominated coal increased, the HMs in the leachable state remained relatively stable (Figure 2a,b), indicating that SiO2 was still able to chemisorb most of the HMs under the influence of NaCl and Na2CO3. Especially for Pb and Cd, the proportion of them in a stable state was consistently above 80%, indicating that the risk of their leakage into the natural environment was relatively low. The percentage of HMs in the leachable state showed an increasing trend with increasing CaO addition (Figure 2c). Because of the physiosorption by CaO on HMs, the probability of chemical reaction of HMs with SiO2 was reduced, which heightens the risk of HM leakage from ash into the surrounding environment. However, the increase in HMs in the leachable state with CaO addition was more prominent compared to those with NaCl and Na2CO3. Therefore, additional attention needed to be paid to the exposure of HMs leached from coal ash.

2.2. HMs Behavior with Different Temperatures

2.2.1. Fixation Rates of HMs

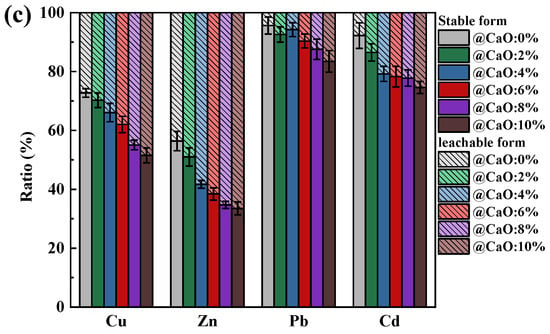

The effect on the immobilization rate of HMs under different temperatures in SiO2-dominated coal is shown in Figure 3, with the contents of sodium chloride, sodium carbonate, and calcium oxide being 3 wt%, 3 wt%, and 6 wt%, respectively. The immobilization rate of HMs gradually decreased with increasing temperature when NaCl was present (Figure 3a). As the temperature increased from 800 °C to 1200 °C, the fixation rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd decreased by 22.60%, 25.23%, 14.21%, and 15.20%, respectively. The decrease in the immobilization rate of Cu, Zn, and Pb was above 1000 °C, which may be due to the increase in the content of chlorinated HMs at high temperatures and the increase in the diffusion rate of HMs. Compared to oxidized HMs, SiO2 was not effective in preventing the volatilization of chlorinated HMs [17,35], which were therefore more likely to be released in gaseous form.

Figure 3.

Temperature effects on the immobilization rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd: (a) NaCl existence; (b) Na2CO3 existence; (c) CaO existence.

The volatilization rate of HMs gradually increased with increasing temperature when Na2CO3 was present (Figure 3b). As the temperature increased from 800 °C to 1200 °C, the fixation rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd decreased by 19.96%, 27.75%, 23.35%, and 20.68%, respectively. At lower temperatures, the reaction between Na2O and SiO2 was kinetically restricted as the generation or diffusion of Na2O was restricted. At high temperatures, the chemical adsorption capacity of SiO2 to Na was enhanced, resulting in a reduction in active sites on the mineral surface. In addition, the higher the temperature, the greater the volatility of HMs, and the lower the ability of SiO2 to control HMs, which were the reasons for the decrease in fixation rate. For example, Yu et al. [17] carried out high-temperature adsorption of PbO on SiO2 at 700~1200 °C, and found that the immobilization rate of Pb gradually decreased after 900 °C. Compared with loading NaCl, a relatively higher immobilization rate was observed in loaded Na2CO3. This may be due to the lack of Cl interference in the combustion system, so most HMs exist in the form of oxides. Compared with chlorinated HMs, their melting and boiling points were lower and easier to retain in coal ash.

The effect of temperature on the volatilization rate of HMs when the SiO2-dominated coal contains CaO is shown in Figure 3c. At 800 °C, the immobilization rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd were 64.87%, 75.21%, 55.43%, and 56.23%, respectively, which were greater than those in the presence of Na compounds, suggesting that CaO inhibited the volatilization of HMs. As the combustion temperature increased, the fixation rate of HMs gradually decreased, with the decrease in Pb was the largest. When the temperature was 1200 °C, the fixation rate of Pb was only 11.80%. In addition to the high volatility of HMs at high temperatures, the decrease in HMs fixation rate was also related to the transformation of CaO at high temperatures. Ca existed in the form of CaCO3 during coal combustion, and decomposition to CaO at about 750 °C. The obtained products had a high adsorption pore volume and pore specific surface area distribution of about 800 °C. Increasing the temperature may lead to sintering and agglomeration of grains, which reduces the adsorption capacity of CaO to HMs [36].

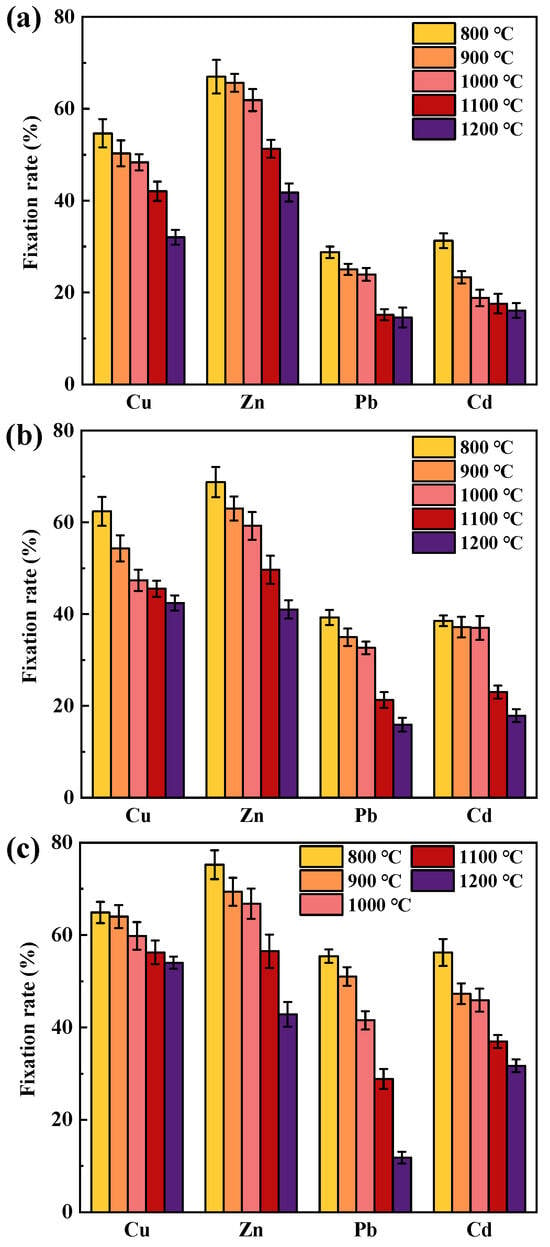

2.2.2. HMs Leaching Behavior

The effect on the leaching behavior of HMs due to temperature is shown in Figure 4. It can be found that with an increase in temperature, the proportion of stable form HMs progressively increases, thereby reducing the risk of HMs leaching. Among these, Zn faced the greatest leaching risk. The percentage of Zn in the leachable form after combustion at 800 °C of coal loaded with NaCl, Na2CO3, and CaO was 53.33%, 49.15%, and 74.76%, respectively. As the temperature reached 1200 °C, although the leachable form of Zn decreased to 34.08%, 36.81%, and 54.33%, a considerable part of Zn was still easily leached under weak acid conditions.

Figure 4.

Temperature effects on the leaching behavior of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd in ash: (a) NaCl existence; (b) Na2CO3 existence; (c) CaO existence.

As the combustion temperature increased, Pb and Cd were more likely to exist in the coal ash in stable form. For samples loaded with NaCl and Na2CO3, the percentage of stable forms Pb and Cd remained above 80% and 90%, respectively, after temperatures greater than 900 °C. When the coal was loaded with CaO, the percentage of stable forms of Pb and Cd remained above 90% at temperatures greater than 1100 °C. This was probably due to the strong volatility of Cd and Pb at high temperatures. SiO2 does not effectively inhibit their diffusion, and most of the Pb and Cd retained in the ash were stably fixed in the form of chemical adsorption.

2.3. Characterization Analysis

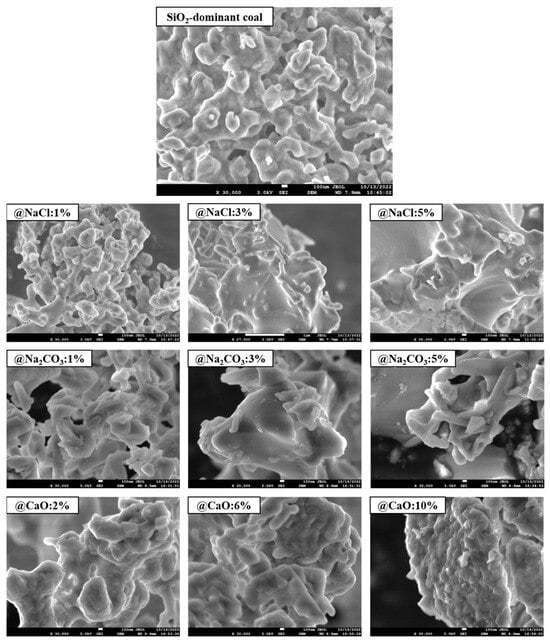

2.3.1. SEM Analysis

The effect of alkaline metals addition on the micro-morphology of the coal ash surface at 1000 °C is illustrated in Figure 5. It can be observed that the pore structure of SiO2-dominated coal ash was abundant, indicating that the metal vapors could freely enter the interior of the mineral with strong reactivity. As the NaCl and Na2CO3 content increased, the melting of the SiO2 surface grew more severe. When the content of NaCl and Na2CO3 increased to 5%, the surface became quite smooth, indicating that the addition of Na formed many of the lower-melting-point minerals. These minerals were wrapped on the SiO2 surface in liquid form at high temperatures, which reduced the active sites of SiO2. As the CaO content increased, the mineral gradually transformed into larger particles with the occurrence of a slight melting phenomenon, which may be related to the formation of wollastonite (melting point 1540 °C), a reaction between CaO and SiO2 [37].

Figure 5.

Morphology of coal ash from SiO2-dominated coal loaded with alkaline metals at 1000 °C.

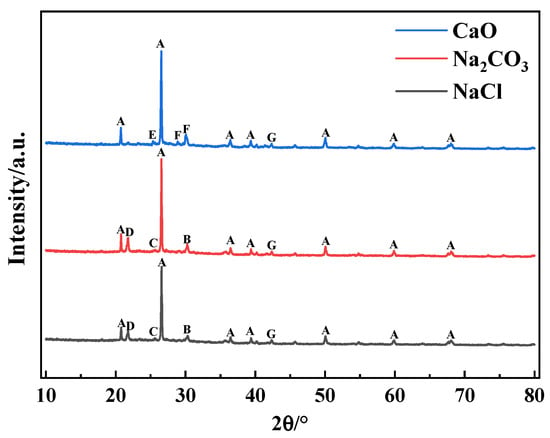

2.3.2. XRD Analysis

XRD analyses of SiO2-dominated coal loaded with constant heavy and alkaline metals after combustion are demonstrated in Figure 6. When the coal contained NaCl and Na2CO3, HMs-containing crystalline phases, including sodium zinc silicate, lead silicate, zinc silicate, and zinc oxide, were detected in the ash, suggesting that SiO2 was capable of chemisorbing Pb and Zn at high temperatures, ultimately immobilizing the HMs in the form of silicates. However, no Cd-containing and Cu-containing substances were detected in the ash, which may be due to the presence of related compounds in an amorphous state. In addition, the presence of alamosite was detected in the ash when CaO was present, whereas the product of Pb was lead silicate in the presence of NaCl and Na2CO3, suggesting that the species of alkaline metals affected the production of the reaction between HMs and SiO2.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of coal ash after combustion of SiO2-dominated coal loaded with alkaline metals at 1000 °C. A—quartz [SiO2]; B—Sodium zinc silicate [Na2ZnSiO4]; C—Lead silicate [Pb3Si2O7]; D—Zinc silicate [Zn2SiO4]; E—Alamosite [PbSiO3]; F—Wollastonite [CaSiO3]; G—Zinc oxide [ZnO].

2.4. Computational Results and Discussion

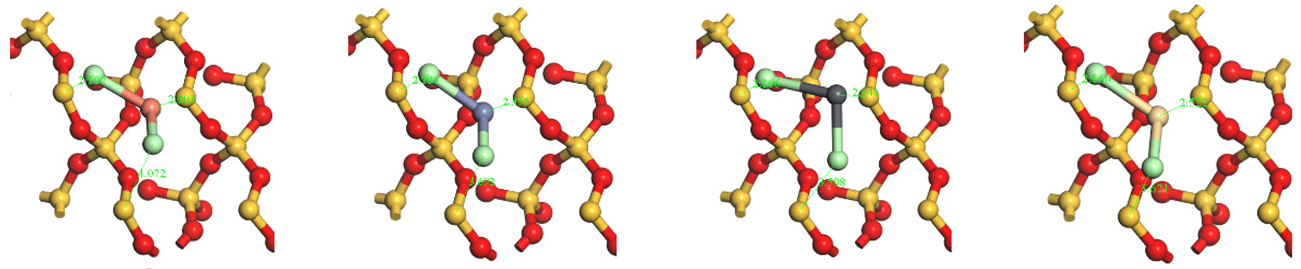

2.4.1. HMs Oxides and Chlorides Adsorption on SiO2(001) Surface

The adsorption configurations of HMs oxides and chlorides on the SiO2(001) surface are presented in Table A1. The adsorption energies of HMs on the SiO2(001) surface are shown in Table 1. The adsorption energies of CuO, ZnO, PbO, and CdO were −620.03 kJ/mol, −505.15 kJ/mol, −378.10 kJ/mol, and −551.94 kJ/mol, respectively, while those of CuCl2, ZnCl2, PbCl2, and CdCl2 were −216.65 kJ/mol, −124.07 kJ/mol, −152.64 kJ/mol, and −144.61 kJ/mol, respectively. These results indicated that SiO2 was chemisorbed for both oxidized and chlorinated HMs.

Table 1.

HMs oxides and chlorides adsorption energies on the SiO2(001) surface and in the existence of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO (kJ/mol).

The Mulliken bond population analysis of HMs molecules and their interacting atoms after the HMs adsorption on the SiO2(001) surface is provided in Table A2. Higher population indicated a stronger interaction force between the atoms [38]. It can be found from Table A2 (a) that the bond population between O and Si(II) atoms was larger than that between heavy metal atoms and Si(IV) atoms, indicating that the O atoms were the main factor for the adsorption of oxidized HMs on the SiO2(001) surface. From Table A2 (b), it could be revealed that the bond population of heavy metal atoms and Si(IV) atoms was relatively larger, indicating that the interaction of Si(IV) with heavy metal atoms dominated the occurrence of chlorinated HMs adsorption.

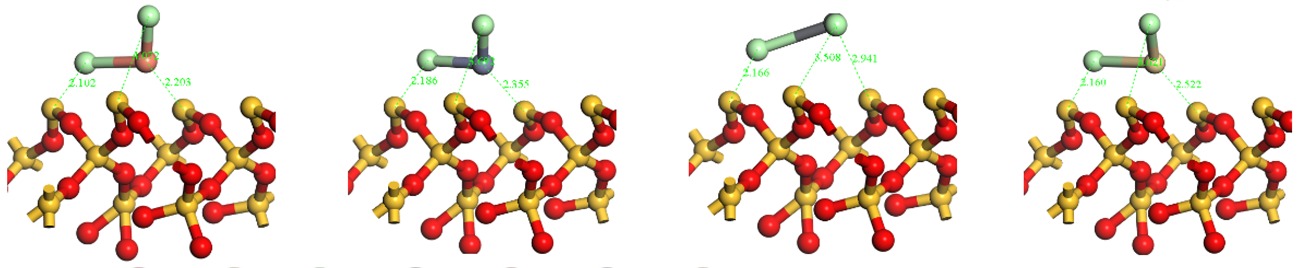

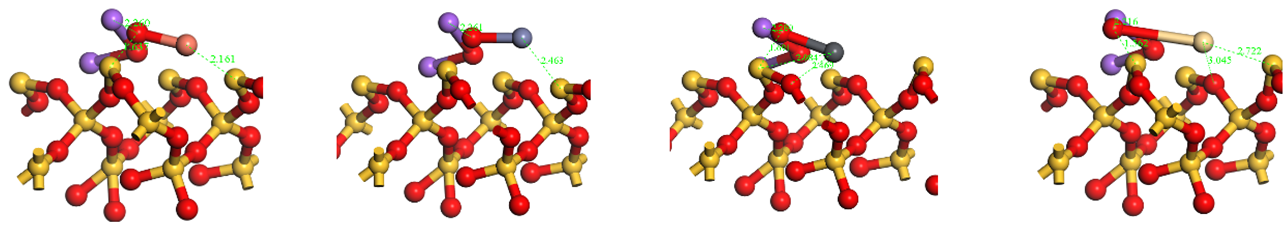

2.4.2. Alkaline Metals Adsorption on SiO2

The optimized structures of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO adsorption on the SiO2(001) surface are shown in Table A3. The adsorption energies of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO on the SiO2(001) surface were −494.31 kJ/mol, −924.70 kJ/mol, and −587.13 kJ/mol, respectively, indicating that SiO2 has better adsorption properties for alkaline metals than HMs. It can be found that the Na atom in the NaCl molecule was spatially close to the Si(IV) atom and the Cl atom was close to the Si(II) atom after adsorption stabilization. O atoms (from Na2O and CaO) were closer to Si(IV) atoms. Since Si(II) and Si(IV) were also active sites for the adsorption of HMs, it can be speculated that the adsorption of alkaline metals on the SiO2(001) surface will affect the subsequent adsorption of HMs.

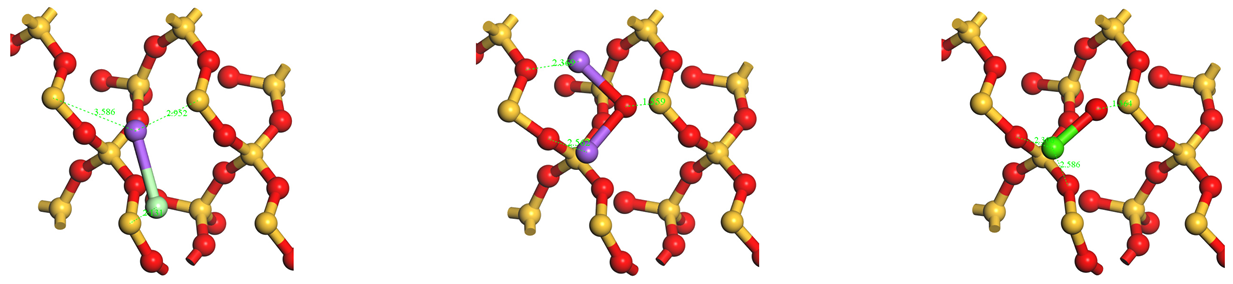

2.4.3. Influence of Alkaline Metal-SiO2 Interactions on the Adsorption of HMs

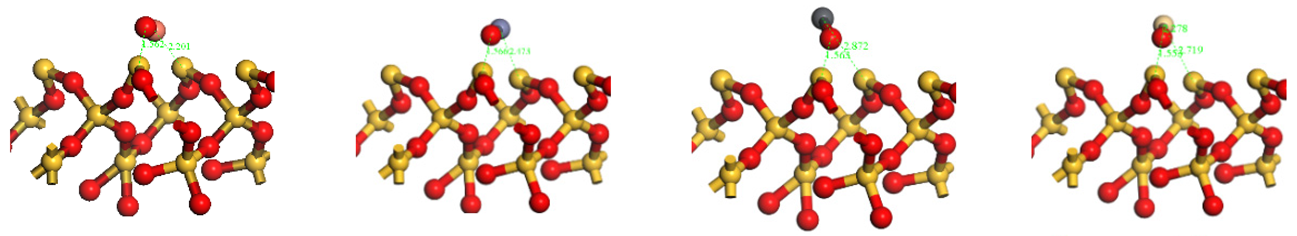

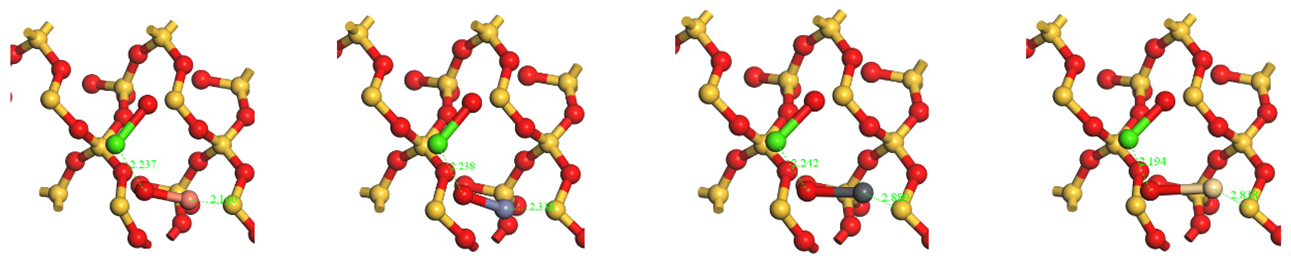

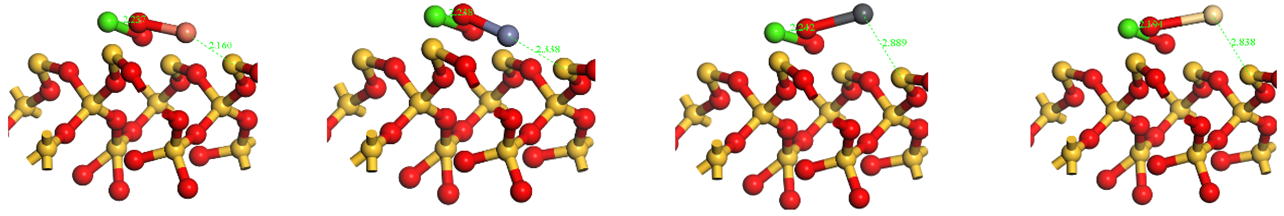

The optimized structures of the HMs adsorption on the surface of NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2 (001) are displayed in Table A4. From Table 1, it can be found that pre-adsorption of alkaline metals caused the adsorption energy of HMs to decrease to different degrees.

Analysis of the Mulliken bonding numbers of HMs molecules and their interacting atoms after adsorption of HMs on the surface of NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2(001) is listed in Table A5. After HMs adsorption on NaCl-SiO2(001) surface, the bond population between Pb and Si(IV) atoms was 0.35, which was less than that of Cu (0.63), Zn (0.63), and Cd (0.56) atoms. After HMs adsorption on the Na2O-SiO2(001) surface, the bond populations of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd atoms with Si (III) atoms were 0.87, 0.7, 0.14, and 0.55, respectively. The above results indicate that the interaction between the Pb atom and substrate was relatively weak compared to Cd, Zn, and Cu, when the SiO2(001) surface was pre-adsorbed with NaCl and Na2O, which is in agreement with the experimental study. The interaction between HMs and alkali species was dominated by competition for Si-O active sites on the quartz surface. No direct electron transfer or redox transition between heavy-metal ions and alkali ions was implied by the DFT results.

Comparison of the co-adsorption energy calculation results and combustion test results found that they were not in good agreement. When the NaCl and Na2O were pre-adsorbed on the SiO2(001) surface, the matrix still exhibited a relatively strong chemisorption capacity for the HMs, which was not consistent with the experimental results that the fixation rate of HMs was significantly reduced by the addition of NaCl and Na2CO3. However, it should be noted that SiO2(001) surface had significant adsorption capacity for NaCl and Na2O with adsorption energies of −494.31 kJ/mol and −924.70 kJ/mol, respectively, which were much larger than the HMs. Considering that the content of alkali metals was well above the HMs, alkali metals would be the earliest to occupy the active sites on the SiO2(001) surface during the combustion process, thus leading to a reduced possibility of co-adsorption of alkali and HMs [39]. Therefore, a significant decrease in the immobilization rate of HMs by the presence of NaCl and Na2CO3 additions was observed in the experiments. It should be clarified that the DFT model reveals intrinsic thermodynamic trends, whereas experimental behavior is dominated by melt-induced kinetic effects [40].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Demineralized Coal

The coal sourced from Shaer Lake, Xinjiang Province, China, was chosen as the feedstock for the preparation of demineralized coal (DEMc). The unprocessed coal was subjected to crushing and sieving to achieve a particle size of 100–120 μm. The HF-HCl method was employed for the preliminary treatment of raw coal [30,41]. First, the raw coal was mixed with HCl (37%) solution at 1 g:3 mL and placed on a magnetic stirrer for 24 h. The material was subsequently subjected to filtration and rinsed in ultra-pure water until achieving a pH of roughly 7. Washing of HCl-washed coal by rinsing with HF solution, the coal was mixed with HF (40%) solution at 1 g:3 mL and placed on a magnetic stirrer for 24 h [42]. Ultimately, the coal subjected to double acid washing was filtered and rinsed until the filtrate reached a neutral pH, followed by drying in a vacuum oven at 105 °C for 12 h. The proximate and ultimate analyses for both the raw and DEMc samples are presented in Table 2. The measured ash content of DEMc was 0.88 wt%, demonstrating that the majority of mineral constituents had been effectively eliminated from primary coal.

Table 2.

The proximate and ultimate analysis of raw and demineralized coal.

3.2. Preparation of SiO2-Dominated Coal

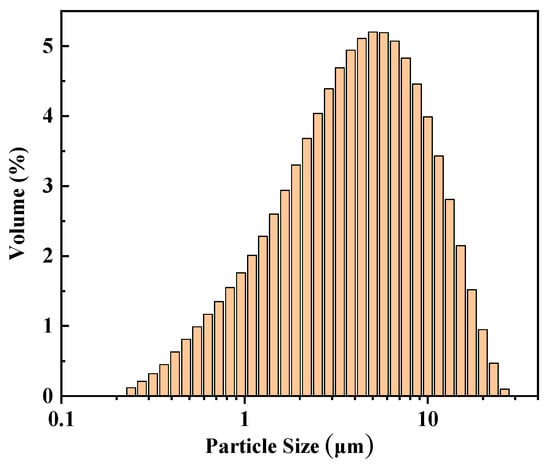

The chemical composition and structural properties of SiO2 are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. The particle size of SiO2 was tested using a Malvern Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK), and the results are shown in Figure A1.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of SiO2.

Table 4.

Structural properties of SiO2.

Initially, DEMc and SiO2 (20 wt%) were dissolved in 10 g of the resultant mix in 15 mL deionized water and 15 mL anhydrous ethanol, stirring for a duration of 24 h. The mass percentage of SiO2 was determined based on the reference range of coal ash content [43,44]. Subsequently, the mixture was subjected to drying at 105 °C to yield SiO2-dominated coal. The SiO2-dominated coal was then blended with NaCl, Na2CO3, and CaO in specific proportions. The concentrations of Na and Ca were set based on the compositional characteristics of high-alkali coal [45]. Specifically, NaCl and Na2CO3 were added at 1~5 wt%, while CaO was set at 2~10 wt%. Finally, the samples were loaded with HMs acetate (Cu 200 mg/kg; Zn 200 mg/kg; Pb 500 mg/kg; Cd 500 mg/kg). The HMs loading was determined with reference to the experimental protocol described by Cai et al. [46]. The concentrations of HMs in the SiO2-dominated coal were documented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The HMs concentrations of the HMs supplements and SiO2-dominated coal.

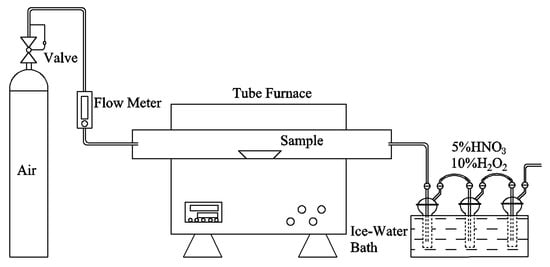

3.3. Combustion Experiment

The combustion experiments were conducted using a horizontal tube furnace, model SGL-1700, from Shanghai Jujing Precision Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, as depicted in Figure A2. This tube furnace was engineered in a closed chamber, utilizing corundum tube of 30 mm diameter and 1000 mm length. Each test involved placing 2.0 ± 0.01 g of the sample into a corundum crucible, which was then inserted into the furnace. When investigating the effect of alkaline metal content variation on the migration and transformation of HMs, the combustion temperature was fixed at 1000 °C. Additionally, a certain amount of alkaline metals was added to the samples, which were then heated to 800 °C, 900 °C, 1000 °C, 1100 °C, and 1200 °C, respectively, to study the influence of temperature changes on HMs. The combustion was carried out under an air atmosphere with a flow rate of 600 mL/min and a heating rate of 15 °C/min, and the combustion lasted for 1 h at the designated temperature. After the combustion tests, the ash remaining in the crucibles was collected for subsequent analysis. To reduce experimental errors, three parallel sets of tests were carried out.

3.4. HMs Detection

The total amount of HMs in the samples was obtained using ICP-OES (ICAP 7000, Thermo Fisher, Worcester, MA, USA). A total of 100 ± 0.5 mg of each ash sample was digested in a microwave digestion system (HANON TANK, Jinan, Shandong province, China) using a mixed acid solution consisting of 8 mL of 65% HNO3, 2 mL of 30% H2O2, and 2 mL of 40% HF. The digestion process was conducted at 180 °C for 40 min, ensuring complete dissolution of the coal ash. HMs leaching from the coal ash was performed via the Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP). For this, an acetate buffer (pH 2.88) was added to each sample at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 20:1, followed by mixing on a rotary shaker for 18 h. Subsequent to shaking, the samples were filtered to collect the HMs leachate, while the residual solids were subjected to complete digestion treatment [47,48]. The stable form indicated that HMs were incorporated into the mineral lattice in the form of silicates, which were not prone to leaching into the natural environment. In contrast, the leachable form referred to HMs physically adsorbed onto the mineral surface, which could be readily leached in acidic aqueous solutions. The distribution of HMs was computed using the following equation:

where MC represents mass of the HMs within the coal, MA denotes the mass of the HMs within the coal ash, and ML and MS refer to the masses of HMs leached and stabilized within the coal ash, respectively. η signifies the percentage of HMs immobilization, while RL and RS indicate the proportions of leached and stabilized forms of HMs within the coal ash, respectively.

3.5. Sample Characterization

The micro-morphology of coal ash was tested using an electron scanning electron microscope (SEM), model JSM-7610F, from Nippon Electron Co, Japan. The mineral composition of coal ash was determined by X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRD, Rigaku’s Smartlab, Wako, Japan). The test parameters were set to Cu target ray, working power set to 4 kW, and the sample was scanned between 2θ values of 10° and 80° at a step size of 10°. It must be declared that the coal ash tested by XRD was obtained by burning coal with a constant HMs content. The content of NaCl, Na2CO3, and CaO used in the experiment was 2 wt%, and the content of acetates containing Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd was 2 wt%, respectively.

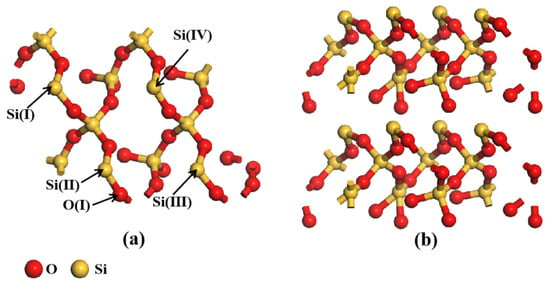

3.6. DFT Computation Details

The DFT computation was performed using the CASTEP (Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package) module within the Materials Studio 2021 Software. The DFT computation was conducted using a plane-wave pseudopotential framework, applying the generalized gradient approximation according to Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof for the exchange function [49]. It should be noted that dispersion correction and electron U addition have not been considered, which may lead to deviations in the value of adsorption energy [50,51]. The OTFG ultrasoft pseudopotential to model the interactions between real ions and valence electrons [52]. The geometric optimization was executed using the Broyden Fletcher Goldfarb Shanno (BFGS) algorithm [53]. To ensure the accuracy of the simulation calculation results, the relevant parameters of the optimization calculation were set as follows: cutoff energy was set to 500 eV; the optimal convergence criterion for total energy difference was set to 1.0 × 10−5 eV/atom; 0.03 eV/Å for the maximum force between atoms; stress was less than 0.05 GPa; and 1.0 × 10−3 Å for maximum displacement. The self-consistent field (SCF) convergence accuracy was 5.0 × 10−7 eV/atom.

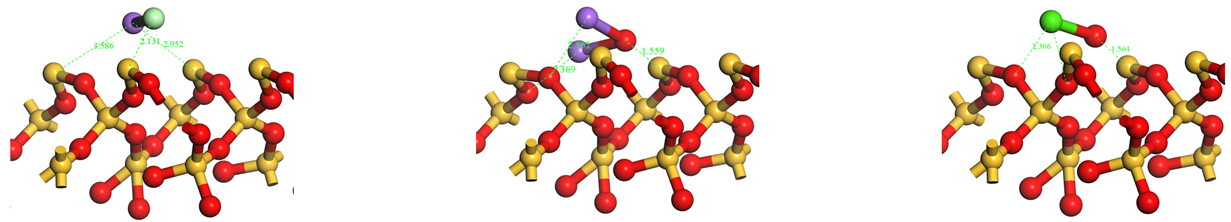

The substrate was chosen using the quartz-alpha structure that was supplied in the Materials Studio 2021 Software. The (001) crystalline surface of SiO2 with the strongest adsorption capacity for HMs was selected for this paper, a reference to the study of Yu et al. [17]. The structure of SiO2 unit cells was first optimized and then faceted. The configuration was then supercell-built (2 × 1 × 1), and a vacuum layer with a thickness of 20 Å was created above the (001) surface. The final SiO2 structure obtained is shown in Figure 7. Some of the atoms have been named to clearly express the bonding of HMs after adsorption on the surface.

Figure 7.

The structure diagram of SiO2: (a) top view; (b) side view.

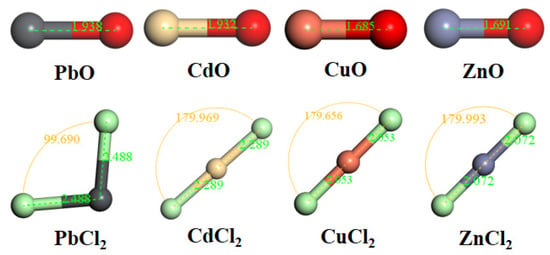

The HMs chlorides and oxides were selected for the study, as heavy metal acetates undergo chemical conversion at high temperatures. The optimized configurations of HMs are shown in Figure 8. As Na2CO3 decomposed to Na2O and participated in reactions at 785 °C, Na2O was selected for adsorption by SiO2 [54,55]. To explore the influence of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO on HMs adsorption to SiO2(001) surface, the co-adsorption of HMs oxide with Na2O, HMs oxide with CaO, and HMs chloride with NaCl was examined accordingly. The adsorption energy (Ead, kJ/mol) was computed based on Equation (17).

Figure 8.

The optimized configurations of oxidized and chlorinated HMs.

Ead = EA+S − EA − ES

4. Conclusions

In this research, the impact of alkaline metals (Na2CO3, NaCl, and CaO) on the adsorption capacity of quartz concerning Copper, Zinc, Lead, and Cadmium were examined during coal combustion.

The inclusion of NaCl and Na2CO3 negatively influenced the preservation of HMs within the ash, with NaCl being more significant in contributing to the release of HMs. As the addition of NaCl increased to 5 wt%, the fixation rates of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd decreased by 17.28%, 12.45%, 24.11%, and 25.73%, respectively. The addition of CaO favored the retention of HMs in the ash. An increase in the combustion temperature will increase the volatilization of HMs. Pb and Cd within the ash were more easily leached into the natural environment compared with Cu and Zn. After CaO addition, the ecological risk of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd leaching from the ash increased by 21.20%, 22.91%, 12.20%, and 17.63%, respectively. Elevated combustion temperatures reduced the proportion of leachable HMs in the ash. The DFT results indicated that the quartz-α(001) surface was capable of achieving chemisorption of chlorinated and oxidized HMs. The adsorption energy for oxidized HMs was higher than chlorinated HMs. After the alkaline metals were pre-adsorbed on the quartz-α(001) surface, the substrate still had a certain degree of chemisorption capacity for HMs.

The combined experimental and DFT study clarified the competitive adsorption mechanism between HMs and alkali metals on the quartz surface. This work provided practical guidance for optimizing the blended combustion of high-alkaline coal as well as the co-combustion systems involving coal and alkali metal-containing wastes. These findings helped improve ash management strategies and mitigate the environmental risks posed by HMs emissions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, Z.Z. and Z.W.; investigation, J.L. and Z.F.; supervision, J.L.; validation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; visualization, J.L.; funding acquisition, X.Z. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Laboratory of Ecological Security Monitoring and Governance at Sichuan Minzu College of Sichuan Province (Approval No. ESMG2025018, ESMG2025014), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Approval No. 2024NSFSC0140), Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (Approval No. 2023NSFSC0414), the Sichuan Engineering Research Center for Titanium Alloy Advanced Manufacturing Technology (Approval No. TM-2024-Z-01), the Open Fund of the Sichuan Engineering Technology Research Center for High Salt Wastewater Treatment and Resource Utilization (Approval No. SCGCZ-2501).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HMs | Heavy metals |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| DEMc | demineralized coal |

Appendix A

The particle size distribution of SiO2 is shown in Figure A1. The schematic diagram of the high-temperature horizontal tube furnace is shown in Figure A2. HMs oxides and chlorides optimize configurations for adsorption on SiO2(001) surfaces are summarized in Table A1. Mulliken bond population analysis of oxidized and chlorinated HMs adsorption on SiO2 is summarized in Table A2. The optimized configurations of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO adsorption over SiO2(001) surface are summarized in Table A3. The optimized structures of the HMs adsorption on the surface of NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2(001) are summarized in Table A4. The Mulliken bond population analysis of HMs adsorption on NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2 surface is summarized in Table A5.

Figure A1.

Particle size distribution of SiO2.

Figure A2.

High-temperature horizontal tube furnace.

Table A1.

HMs oxides and chlorides optimize configurations for adsorption on SiO2(001) surfaces.

Table A1.

HMs oxides and chlorides optimize configurations for adsorption on SiO2(001) surfaces.

| HMs | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxides HMs adsorption structures | Top view |  | |||

| Side view |  | ||||

| Chlorides HMs adsorption structures | Top view |  | |||

| Side view |  | ||||

Notes:  .

.

.

.

Table A2.

Mulliken bond population analysis of oxidized and chlorinated HMs adsorption on SiO2: (a) oxidized HMs; (b) chlorinated HMs.

Table A2.

Mulliken bond population analysis of oxidized and chlorinated HMs adsorption on SiO2: (a) oxidized HMs; (b) chlorinated HMs.

| (a) | |||||||||||

| CuO | ZnO | PbO | CdO | ||||||||

| Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P |

| Cu-O | 1.928 | 0.24 | Zn-O | 1.958 | 0.21 | Pb-O | 2.319 | 0.13 | Cd-O | 2.278 | 0.12 |

| Cu-Si(IV) | 2.201 | 0.59 | Zn-Si(IV) | 2.473 | 0.48 | Pb-Si(IV) | 2.872 | 0.46 | Cd-Si(IV) | 2.719 | 0.38 |

| O-Si(II) | 1.562 | 0.79 | O-Si(II) | 1.566 | 0.73 | O-Si(II) | 1.563 | 0.74 | O-Si(II) | 1.553 | 0.79 |

| (b) | |||||||||||

| CuCl2 | ZnCl2 | PbCl2 | CdCl2 | ||||||||

| Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P |

| Cu-Cl(I) | 2.474 | 0.06 | Zn-Cl(I) | 2.434 | 0.16 | Pb-Cl(I) | 2.922 | 0.07 | Cd-Cl(I) | 2.715 | 0.10 |

| Cu-Cl(II) | 2.093 | 0.46 | Zn-Cl(II) | 2.107 | 0.61 | Pb-Cl(II) | 2.483 | 0.31 | Cd-Cl(II) | 2.319 | 0.51 |

| Cu-Si(IV) | 2.203 | 0.54 | Zn-Si(IV) | 2.355 | 0.61 | Pb-Si(IV) | 2.941 | 0.36 | Cd-Si(IV) | 2.522 | 0.56 |

| Cl(I)-Si(I) | 2.102 | 0.44 | Cl(I)-Si(I) | 2.186 | 0.34 | Cl(I)-Si(I) | 2.166 | 0.32 | Cl(I)-Si(I) | 2.160 | 0.36 |

Notes: D(Å)-Bond length (Å); P-Population; Cl(I) and Cl(II) represent the top and bottom Cl atoms (from chlorinated HMs) in the top view (Table A1), respectively.

Table A3.

The optimized configurations of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO adsorption over SiO2(001) surface.

Table A3.

The optimized configurations of NaCl, Na2O, and CaO adsorption over SiO2(001) surface.

| Alkaline Metals | NaCl | Na2O | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top view |  | ||

| Side view |  | ||

Notes:  .

.

.

.

Table A4.

The optimized structures of the HMs adsorption on the surface of NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2(001).

Table A4.

The optimized structures of the HMs adsorption on the surface of NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2(001).

| HMs | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Metals | |||||

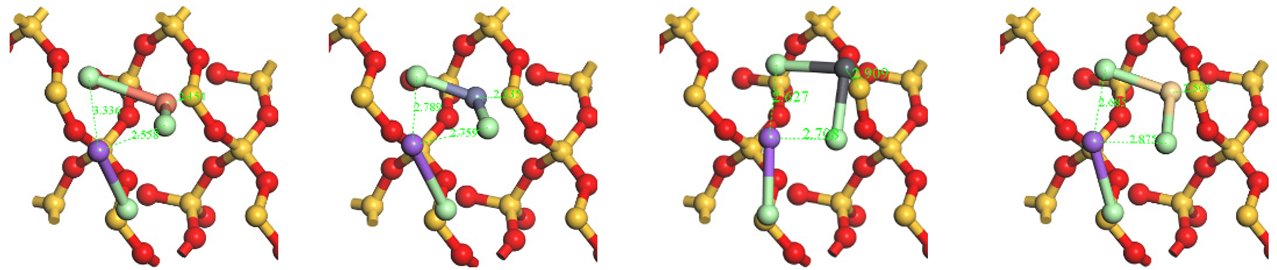

| NaCl | Top view |  | |||

| Side view |  | ||||

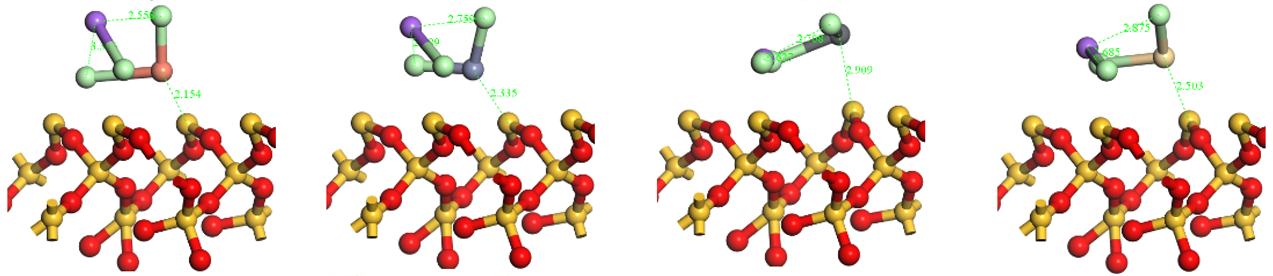

| Na2O | Top view |  | |||

| Side view |  | ||||

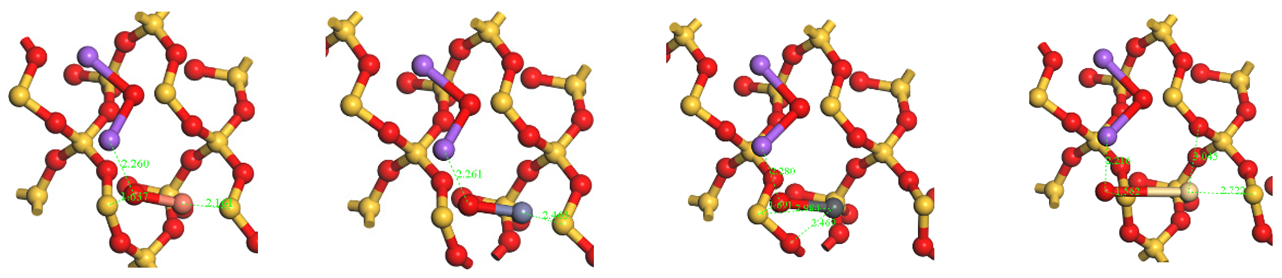

| CaO | Top view |  | |||

| Side view |  | ||||

Notes:  .

.

.

.

Table A5.

Mulliken bond population analysis of HMs adsorption on NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2 surface: (a) chlorinated HMs adsorption on the NaCl-SiO2 surface; (b) oxidized HMs adsorption on the Na2O-SiO2 surface; (c) oxidized HMs adsorption on the CaO-SiO2 surface.

Table A5.

Mulliken bond population analysis of HMs adsorption on NaCl/Na2O/CaO-SiO2 surface: (a) chlorinated HMs adsorption on the NaCl-SiO2 surface; (b) oxidized HMs adsorption on the Na2O-SiO2 surface; (c) oxidized HMs adsorption on the CaO-SiO2 surface.

| (a) | |||||||||||

| CuCl2 | ZnCl2 | PbCl2 | CdCl2 | ||||||||

| Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P |

| Cu-Cl(Ⅰ) | 2.906 | 0.03 | Zn-Cl(Ⅰ) | 2.229 | 0.42 | Pb-Cl(Ⅰ) | 2.639 | 0.22 | Cd-Cl(Ⅰ) | 2.484 | 0.33 |

| Cu-Cl(Ⅱ) | 2.132 | 0.47 | Zn-Cl(Ⅱ) | 2.183 | 0.53 | Pb-Cl(Ⅱ) | 2.573 | 0.27 | Cd-Cl(Ⅱ) | 2.376 | 0.45 |

| Cu-Si(Ⅳ) | 2.154 | 0.63 | Zn-Si(Ⅳ) | 2.335 | 0.63 | Pb-Si(Ⅳ) | 2.909 | 0.35 | Cd-Si(Ⅳ) | 2.503 | 0.56 |

| Cl(Ⅰ)-Si(Ⅰ) | 2.143 | 0.37 | Cl(Ⅰ)-Na | 2.789 | 0.03 | Cl(Ⅰ)-Na | 2.627 | 0.10 | Cl(Ⅰ)-Na | 2.685 | 0.06 |

| Cl(Ⅱ)-Na | 2.558 | 0.08 | Cl(Ⅱ)-Na | 2.759 | 0.03 | Cl(Ⅱ)-Na | 2.708 | 0.08 | Cl(Ⅱ)-Na | 2.875 | 0.05 |

| (b) | |||||||||||

| CuO | ZnO | PbO | CdO | ||||||||

| Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P |

| Cu-O | 1.852 | 0.40 | Zn-O | 1.918 | 0.32 | Pb-O | 2.193 | 0.20 | Cd-O | 3.357 | - |

| Cu-Si(Ⅱ) | 2.877 | - | Zn-Si(Ⅱ) | 3.126 | - | Pb-O(Ⅰ) | 2.469 | 0.05 | Cd-Si(Ⅱ) | 2.631 | 0.53 |

| Cu-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.161 | 0.87 | Zn-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.463 | 0.70 | Pb-Si(Ⅲ) | 3.532 | 0.14 | Cd-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.722 | 0.55 |

| O-Na(Ⅱ) | 2.260 | - | O-Na(Ⅱ) | 2.261 | - | O-Na(Ⅱ) | 2.280 | 0.04 | O-Na(Ⅱ) | 2.216 | 0.13 |

| O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.637 | 0.54 | O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.643 | 0.51 | O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.691 | 0.50 | O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.562 | 0.82 |

| (c) | |||||||||||

| CuO | ZnO | PbO | CdO | ||||||||

| Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P | Bond | D(Å) | P |

| Cu-O | 1.879 | 0.29 | Zn-O | 1.867 | 0.34 | Pb-O | 2.198 | 0.18 | Cd-O | 2.491 | 0.06 |

| Cu-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.160 | 0.57 | Zn-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.338 | 0.65 | Pb-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.889 | 0.40 | Cd-Si(Ⅲ) | 2.838 | 0.28 |

| O-Ca | 2.237 | 0.12 | O-Ca | 2.238 | 0.13 | O-Ca | 2.242 | 0.13 | O-Ca | 2.194 | 0.15 |

| O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.690 | 0.42 | O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.766 | 0.37 | O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.758 | 0.32 | O-Si(Ⅱ) | 1.631 | 0.50 |

References

- Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, D.; Feng, D. Effect of coal consumption on the upgrading of industrial structure. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 4313175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetari, P.S.; Hadi, S.P.; Huboyo, H.S. Trace elements in fine and coarse particles emitted from coal-fired power plants with different air pollution control systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109497. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhou, C. The partitioning and environmental characteristics of trace elements in a coal-fired power plant: A case study at Huaibei, China. Environ. Forensics 2019, 20, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Duan, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Lu, J.; Ding, Y.; Gu, X.; Tao, J.; Du, M. Emission characteristic and transformation mechanism of hazardous trace elements in a coal-fired power plant. Fuel 2018, 214, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, M.V.; Radomirović, M.; Velasco, P.M.; Mijatović, N. Geochemical profiles of deep sediment layers from the Kolubara district (Western Serbia): Contamination status and associated risks of heavy metals. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Dong, L.; Zhong, Z.; Lai, X.; Huang, Y. Capture effect of Pb, Zn, Cd and Cr by intercalation-exfoliation modified montmorillonite during coal combustion. Fuel 2021, 290, 119980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Tian, J.; Han, Y.; Chuang, H.; Sun, J.; Shen, Z.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Ho, K.F. ARTICLE INFO Keywords: Household coal combustion PM2.5 Oxidative stress Respiratory health effects. Fuel 2022, 321, 123998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabersek, M.; Watts, M.J.; Gosar, M. Attic dust: An archive of historical air contamination of the urban environment and potential hazard to health. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Su, W.; Li, N.; Song, Q.; Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Li, Y.; Lowe, S.; Bentley, R.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Association of urinary or blood heavy metals and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 67483–67503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Xue, Y.; Chen, J.; Meng, Q.; Wu, Z. Elimination of chloroaromatic congeners on a commercial V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalyst: The effect of heavy metal Pb. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 121705. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Naruse, I. Using sorbents to control heavy metals and particulate matter emission during solid fuel combustion. Particuology 2009, 7, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, G.; Xu, Z.; Sun, H.; Lam, P.K.S. Retention mechanisms of ash compositions on toxic elements (Sb, Se and Pb) during fluidized bed combustion. Fuel 2018, 213, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Masto, R.E.; Gautam, S.; Choudhury, D.P.; Ram, L.C.; Maiti, S.K.; Maity, S. Investigations on PAHs and trace elements in coal and its combustion residues from a power plant. Fuel 2015, 162, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liu, G.; Sun, M.; Hower, J.C.; Hu, G.; Wu, D. A comparative study on the mineralogy, chemical speciation, and combustion behavior of toxic elements of coal beneficiation products. Fuel 2018, 228, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.A.; Zhao, L.; Sun, R.; Hu, Y.; Tang, G.; Chen, W.; Du, Y.; Che, D. Effects of silicon-aluminum additives on ash mineralogy, morphology, and transformation of sodium, calcium, and iron during oxy-fuel combustion of Zhundong high-alkali coal. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 91, 102832. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; He, P.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H. Multifunctional effect of Al2O3, SiO2 and CaO on the volatilization of PbO and PbCl2 during waste thermal treatment. Chemosphere 2016, 161, 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, C.; Ma, L.; Fang, Q.; Chen, G. Experimental and DFT studies on the characteristics of PbO/PbCl2 adsorption by Si/Al-based sorbents in the simulated flue gas. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124742. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Zhong, Z.; Xue, H. Partition of Zn, Cd, and Pb during co-combustion of Sedum plumbizincicola and sewage sludge. Chemosphere 2018, 197, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Xia, J.; Zhu, Y. Dynamic zinc and potassium release from a burning hyperaccumulator pellet and their interactions with inhibitive additives. Fuel 2021, 286, 119365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Meng, A.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Effects of sorbents on the partitioning and speciation of cu during municipal solid waste incineration. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 22, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, Q.; Liu, J. Mineral transformation and emission behaviors of Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb and Zn during the co-combustion of dried waste activated sludge and lignite. Fuel 2017, 199, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Dou, C.; Hou, J.; Wang, Z.; Shen, B. Influence pattern of reaction conditions on pyrolysis products from solid agricultural and forestry waste. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Meiheriayi, M.; Liu, J.; Lyu, Q. Study on dynamic characteristics of preheating coal coke with high alkali coal by preheating air equivalent ratio. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H. Effect of Cl content on volatility of Na and K in high alkali coal. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 118−123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, X.; Lv, G.; Nixiang, A.; Jin, Y.; Yan, J.; Lin, X.; Song, H.; Cao, J. Effect of chlorine, sulfur, moisture and ash content on the partitioning of as, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni and Pb during bituminous coal and pickling sludge co-combustion. Fuel 2019, 239, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Han, Z.; Cai, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.; Chen, L. Research and application status of combustion of Zhundong coal with a large proportion in circulating fluidized bed boiler. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Fu, J.; Ning, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W.; Huang, S.; Zhong, S. An experimental and thermodynamic equilibrium investigation of the Pb, Zn, Cr, Cu, Mn and Ni partitioning during sewage sludge incineration. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 35, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Huang, Y.; Clough, P.T.; Dong, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, M. Desulfurization using limestone during sludge incineration in a fluidized bed furnace: Increased risk of particulate matter and heavy metal emissions. Fuel 2020, 273, 117614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Bai, Y.; Lv, P.; Wang, J.; Song, X.; Su, W.; Yu, G. Insights into the role of calcium during coal gasification in the presence of silicon and aluminum. Fuel 2021, 302, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Feng, J.; Li, W. Acid pretreatment effect on oxygen migration during lignite pyrolysis. Fuel 2020, 262, 116650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Meng, A.; Jia, J.; Zhang, Y. Investigation of heavy metal partitioning influenced by flue gas moisture and chlorine content during waste incineration. J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 22, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Du, R.; Liu, Y.; Lin, P.; Zhang, J.; Bu, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W. High-temperature chlorination of PbO and CdO induced by interaction with NaCl and Si/Al matrix. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 34449–34458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Wang, X.; Tan, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Effect of silicon-aluminum additives on ash fusion and ash mineral conversion of Xinjiang high-sodium coal. Fuel 2016, 181, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, J.O.L.; Lee, S.J. High-temperature sorbents for Hg, Cd, Pb, and other trace metals: Mechanisms and applications. Fuel 2010, 89, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, P.; Xia, Y.; Lu, W.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H. Role of sodium chloride and mineral matrixes in the chlorination and volatilization of lead during waste thermal treatment. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 143, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Lai, X. Enrichment of heavy metals during coal combustion by mineral additives. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2020, 39, 2479–2486. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Tan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, T.; Ruan, R. Investigation of characteristics and formation mechanisms of deposits on different positions in full-scale boiler burning high alkali coal. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 119, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, D.; Zeng, Y.; Wen, S.; Chen, L. DFT study of SDD and BX adsorption on sphalerite (110) surface in the absence and presence of water molecules. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 450, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, R.D.; Mcgrath, R. Structural studies of alkali metal adsorption and coadsorption on metal surfaces. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1996, 23, 43–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jund, P.; Kob, W.; Jullien, R. Channel diffusion of sodium in a silicate glass. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 134303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Sun, R.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Li, Y.P.; Ismail, T.M.; Ren, X.H. Investigation of demineralized coal char surface behaviour and reducing characteristics after partial oxidative treatment under an O2 atmosphere. Fuel 2018, 233, 658–668. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorai, S.; Ghosh, B.; Chandaliya, V.K.; Singh, R.; Dash, P.S.; Mal, D. Difference in structural chemistry of non-coking and coking coal using acid treatment demineralization technique. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2022, 42, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeev, D.; Kunilova, I.; Shoppert, A.; Salazar-Concha, C.; Kondratiev, A. High-pressure HCl leaching of coal ash to extract Al into a chloride solution with further use as a coagulant for water treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Prasad, A.K.; Vinod, A.; Shukla, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Purkait, B.; Varma, A.K.; Sarkar, B.C. A multi-model approach for estimation of ash yield in coal using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, M.; Yang, Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, L.; Shen, B. SO2 and NO emissions during combustion of high-alkali coal over a wide temperature range: Effect of Na species and contents. Fuel 2022, 309, 122212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Liu, J.; Kuo, J.; Xie, W.; Evrendilek, F.; Zhang, G. Ash-to-emission pollution controls on co-combustion of textile dyeing sludge and waste tea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yi, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Shen, B.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.; Shi, Q.; Huang, C. Effect of alkaline metals (Na, Ca) on heavy metals adsorption by kaolinite during coal combustion: Experimental and DFT studies. Fuel 2023, 348, 128503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liang, A.; Liu, J.; Mei, M.; Lao, X.; Hou, H.; Li, J. Effect of addition of rice husk on the fate and speciation of heavy metals in the bottom ash during dyeing sludge incineration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M.; Perdew, J.P. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple [Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996)]. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.J.; Pan, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Computational study of APTES surface functionalization of diatom-like amorphous SiO2 surfaces for heavy metal adsorption. Langmuir 2020, 36, 5680–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jossou, E.; Malakkal, L.; Dzade, N.Y.; Claisse, A.; Szpunar, B.; Szpunar, J. DFT + U Study of the Adsorption and Dissociation of Water on Clean, Defective, and Oxygen-Covered U3Si2{001}, {110}, and {111} Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 19453–19467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, R.A.; Brock, C.N.; Paikoff, B.C.; Tackett, A.R.; Walker, D.G. Automated generation of highly accurate, efficient and transferable pseudopotentials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2015, 196, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrommer, B.G.; Côté, M.; Louie, S.G.; Cohen, M.L. Relaxation of crystals with the Quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 131, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.E.; Lv, Y.; Niu, Y.; Li, S.; Lei, Y.; Li, P. Effects of leaching and additives on the formation of deposits on the heating surface during high-Na/Ca Zhundong coal combustion. J. Energy Inst. 2021, 94, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardane, R.V.; Poston, J.A.; Robinson, C.; Simonyi, T. Effect of additives on decomposition of sodium carbonate: Precombustion CO2 capture sorbent regeneration. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).