Thickness Effect on Structural, Electrical, and Optical Properties of Ultrathin Platinum Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Structure and Morphology of the Pt Thin Films

2.1.1. SEM, AFM

2.1.2. TEM

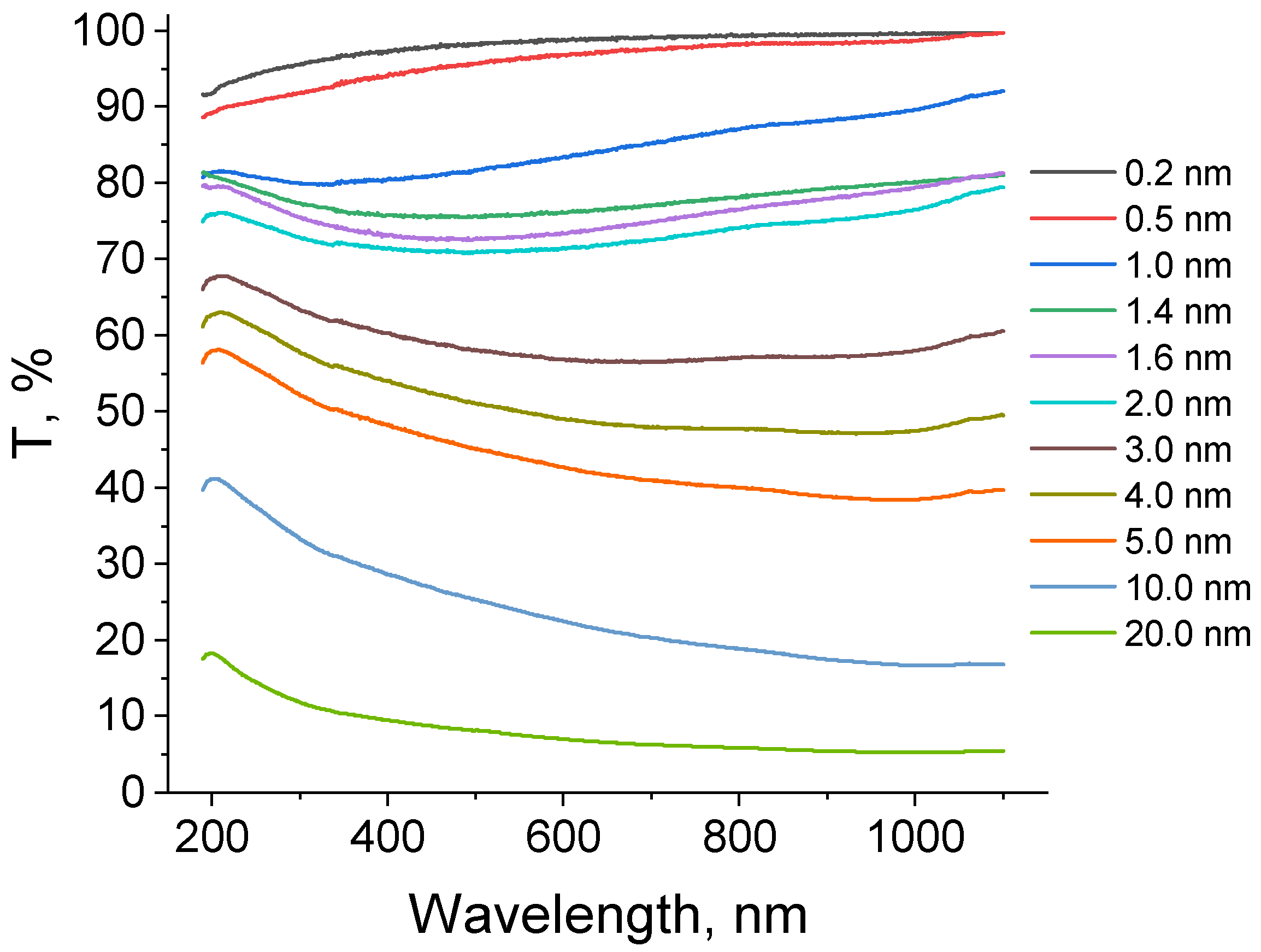

2.2. Optical Properties of the Pt Thin Films

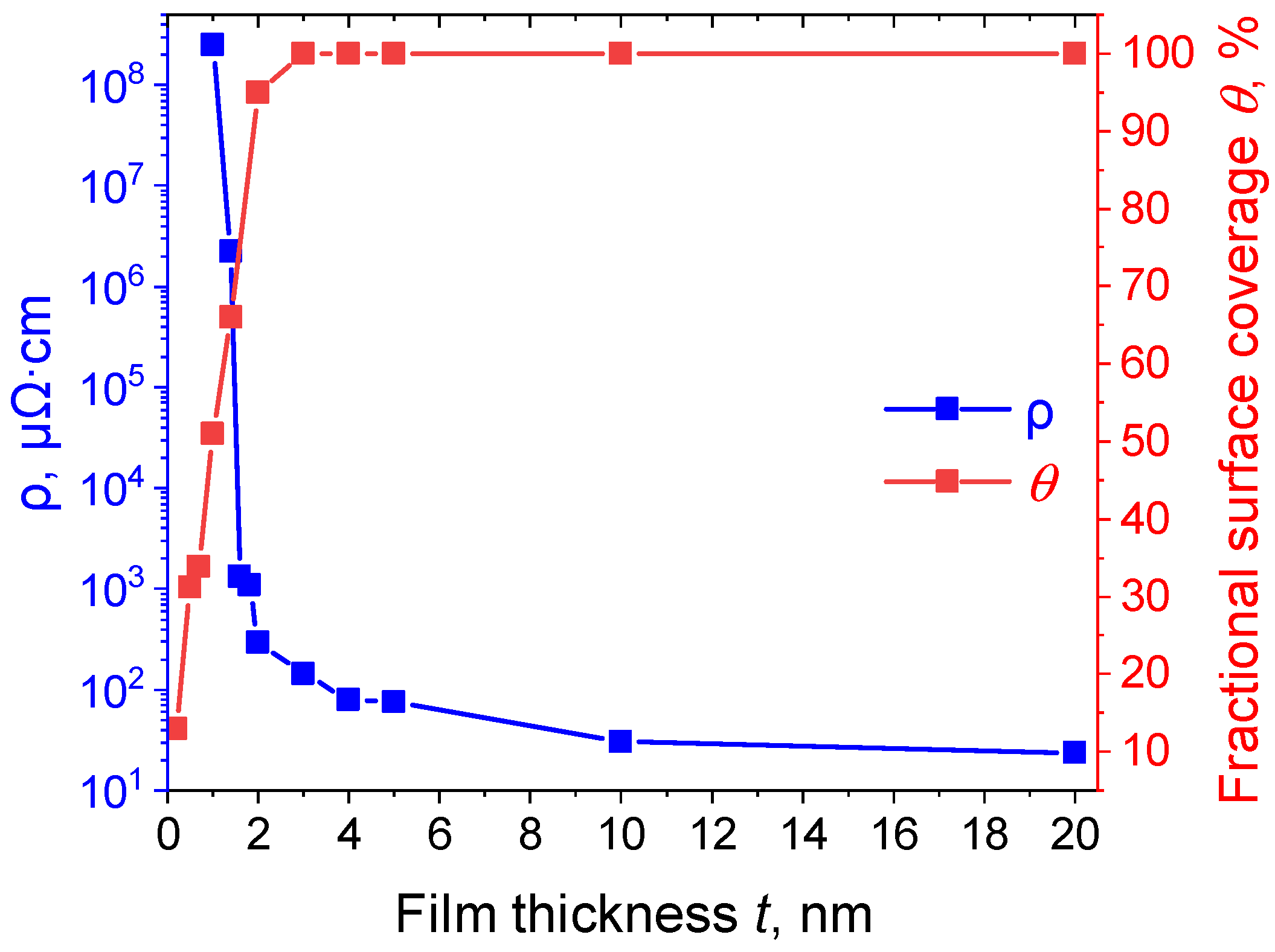

2.3. Electrical Properties of the Pt Thin Films

2.3.1. The Effect of Pt Film Thickness on the Value of Electrical Resistivity

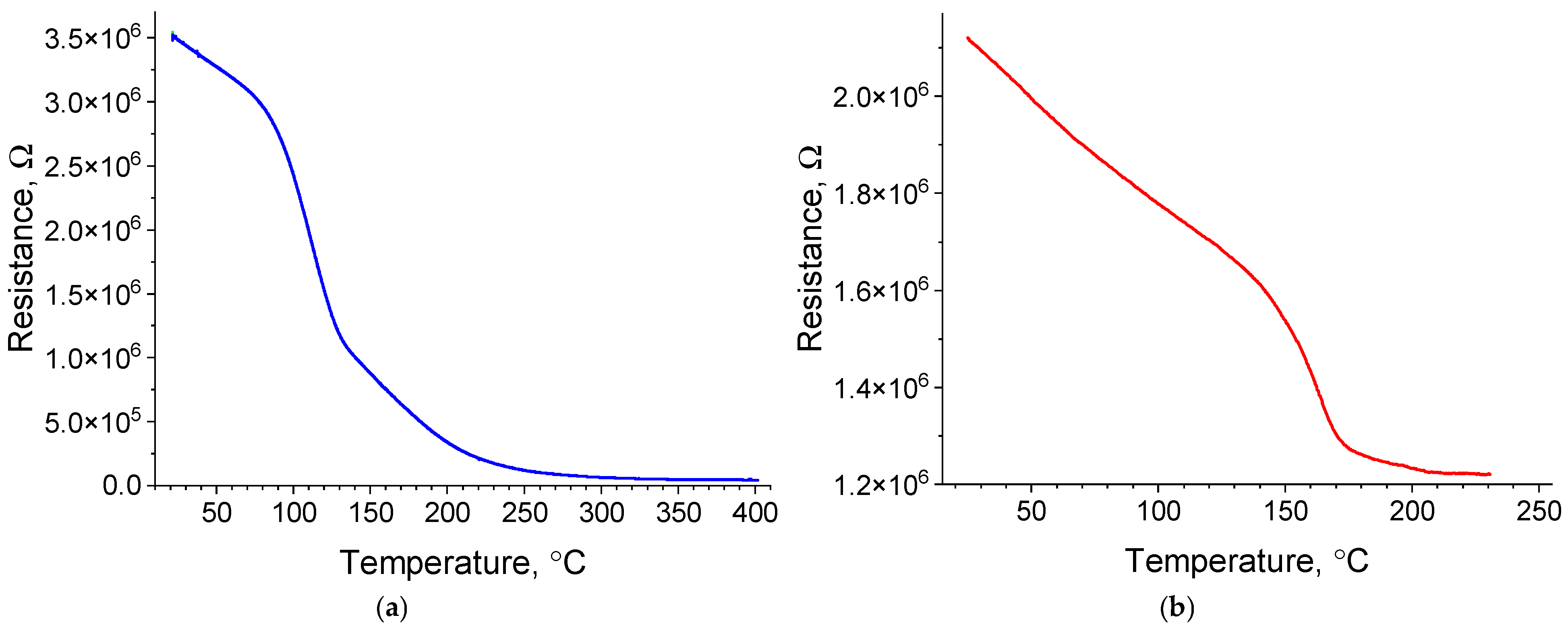

2.3.2. Temperature Dependence of the Electrical Resistance on Platinum Island Films

3. Discussion

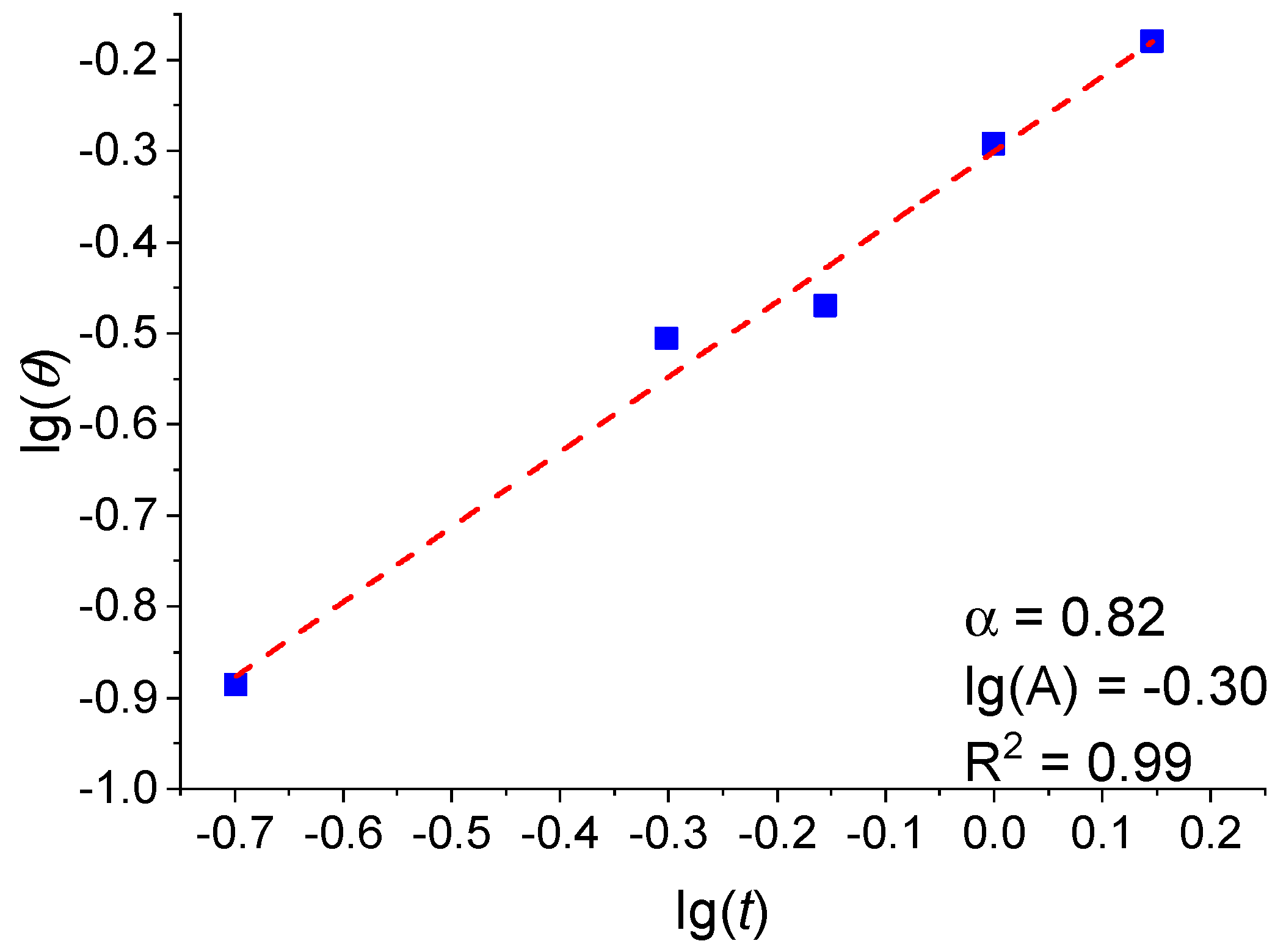

3.1. Analysis of the Dependence of the Fractional Surface Coverage on the Pt Film Thickness

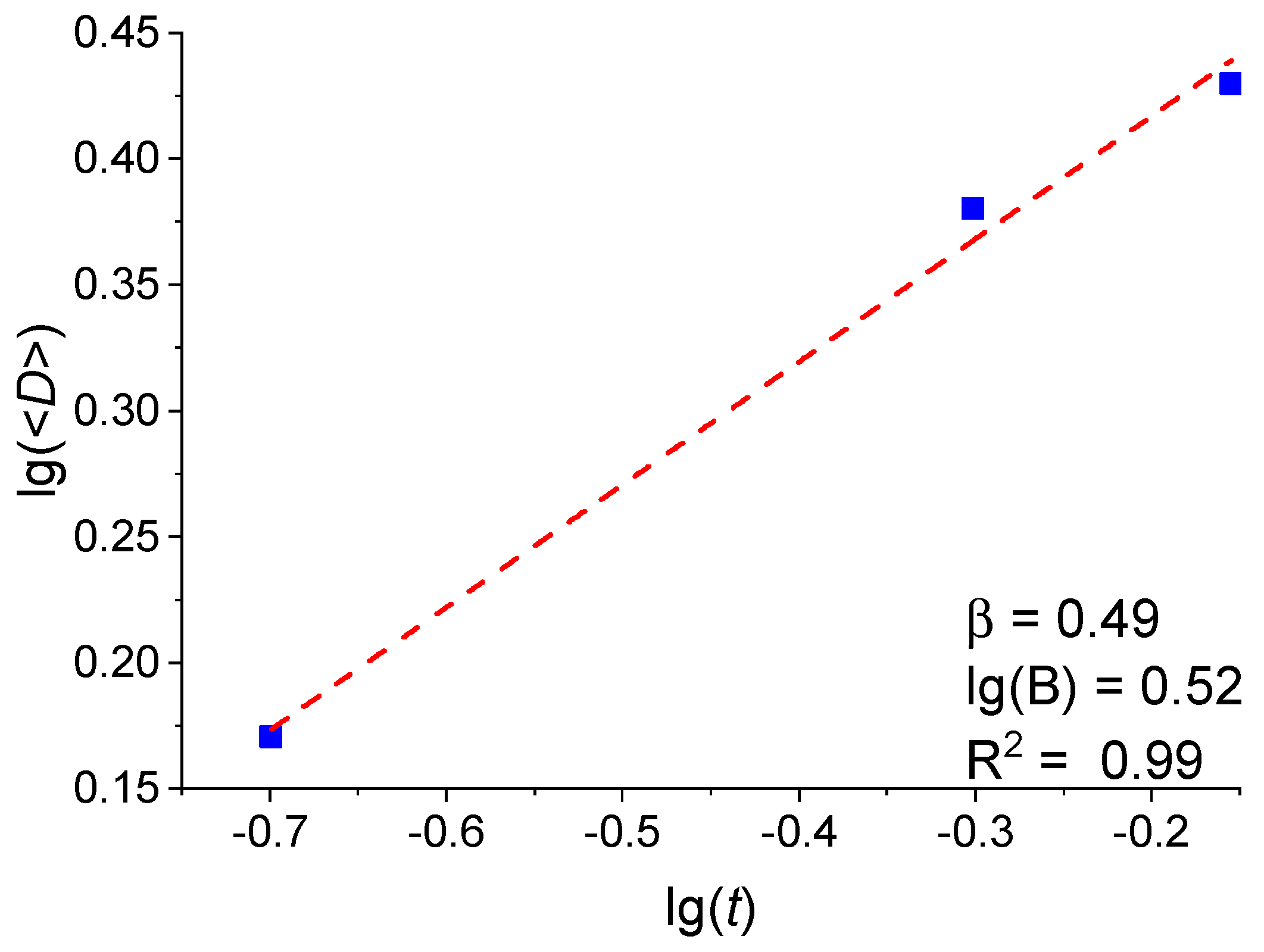

3.2. Analysis of the Dependence of the Crystallite Size on the Pt Film Thickness

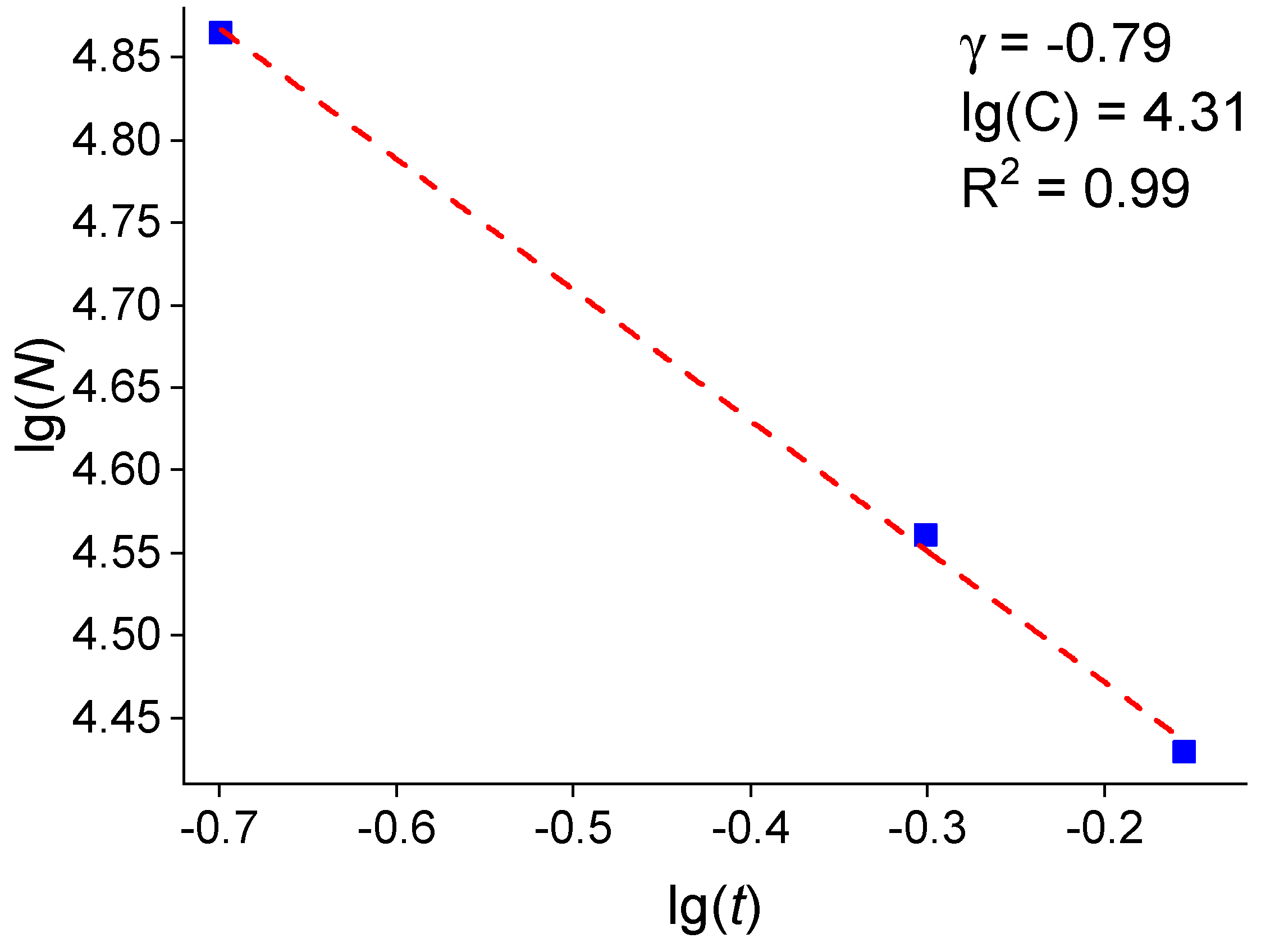

3.3. Analysis of the Dependence of the Island Density on the Pt Thin Films

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Method and Conditions of Fabricating Thin Film Samples

4.2. Methods for Studying Structural Properties

4.2.1. SEM and AFM

4.2.2. TEM and ED

4.3. Study of Electrical Properties

4.4. Study of Optical Properties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| BCC | Body-Centered Cubic |

| BCT | Body-Centered Tetragonal |

| ED | Electron Diffraction |

| GISAXS | Grazing incidence-small angle X-ray scattering |

| HCP | Hexagonal Close-Packed |

| ML | Monolayer |

| SAED | Selected Area Electron Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

References

- Wetzig, K.; Schneider, C.M. Metal Based Thin Films for Electronics, 2nd ed.; Willey-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; 410p. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-C.; He, L.-C.; Yeh, K.-Y.; Lin, K.-B.; Liu, H.-T.; Chiu, S.-J.; Lin, Y.-G.; Tsai, Y.-W.; Lin, J.-M.; Chang, S.-H.; et al. Large-Period van der Waals Epitaxy of Au on MoS2 at Room Temperature: Moiré-Engineered Interfaces for Nanoelectronics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 18208–18215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.A.L.; Mejía-Salazar, J.R.; Carvalho, W.O.F.; Mercado, C.L.; Nedev, N.; Gómez, F.R.; Oliveira, O.N., Jr.; Farías, M.H.; Tiznado, H. Ultrathin nanocapacitor assembled via atomic layer deposition. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 505711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, M.; da Silva Fanta, A.B.; Jensen, F.; Wagner, J.B.; Han, A. Influence of Ti and Cr Adhesion Layers on Ultrathin Au Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37374–37385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham-Diamand, Y.; Inberg, A.; Sverdlov, Y.; Bogush, V.; Croitoru, N.; Moscovich, H.; Freeman, A. Electroless processes for micro- and nanoelectronics. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 2987–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, J.J.; Stewart, D.R.; Li, Z. Plasma-produced ultra-thin platinum-oxide films for nanoelectronics: Physical characterization. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2005, 80, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, R.; Schwarz, D.; Funk, H.S.; Guguieva, K.; Schulze, J. High-quality remote plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition of aluminum oxide thin films for nanoelectronics applications. Solid-State Electron. 2021, 185, 108027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kats, M.A.; Capasso, F. Optical absorbers based on strong interference in ultra-thin films. Laser Photonics Rev. 2016, 10, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conoci, S.; Petralia, S.; Samorì, P.; Raymo, F.M.; Di Bella, S.; Sortino, S. Optically transparent, ultrathin Pt films as versatile metal substrates for molecular optoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosovsky, D.A.; Zalyalov, T.M.; Ponomarev, S.A.; Zhivodkov, Y.A.; Shukhov, Y.G.; Morozov, A.A.; Starinskiy, S.V. Controlling the percolation threshold in adhesion-layer-free room-temperature nanosecond pulsed laser deposition of ultrathin gold films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 719, 165049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Stokes, J.; Fox, N.A.; Teng, M.; Cryan, M.J. Ultra-thin metal films for enhanced solar absorption. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, H.M.; Williams, R.J.; Jones, T.S.; Hatton, R.A. Ultrathin transparent Au electrodes for organic photovoltaics fabricated using a mixed mono-molecular nucleation layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fthenakis, V. Sustainability of photovoltaics: The case for thin-film solar cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2746–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, H.-J.; Pacchioni, G. Oxide ultra-thin films on metals: New materials for the design of supported metal catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 2224–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Mukherjee, S.; Ren, B.; Cao, R.; Fischer, R.A. Open Framework Material Based Thin Films: Electrochemical Catalysis and State-of-the-art Technologies. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2003499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollár, T.; Vancsó, P.; Kun, P.; Koós, A.A.; Dobrik, G.; Sukhanova, E.V.; Popov, Z.I.; Németh, M.; Frey, K.; Pécz, B.; et al. Semiconducting Pt Structures Stabilized on 2D MoS2 Crystals Enable Ultrafast Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2504113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-W.; Takahara, N.; Korposh, S.; Yang, D.-H.; Toko, K.; Kunitake, T. Nanoassembled Thin Film Gas Sensors. III. Sensitive Detection of Amine Odors Using TiO2/Poly(acrylic acid) Ultrathin Film Quartz Crystal Microbalance Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 2228–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, M. Single-atom catalysts boosted ultrathin film sensors. Rare Met. 2020, 39, 1110–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva, N.S.; Klyamer, D.D.; Zharkov, S.M.; Tsygankova, A.R.; Sukhikh, A.S.; Morozova, N.B.; Basova, T.V. Heterostructures based on Pd-Au nanoparticles and cobalt phthalocyanine for hydrogen chemiresistive sensors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19682–19692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorovskikh, S.I.; Klyamer, D.D.; Maksimovskii, E.A.; Volchek, V.V.; Zharkov, S.M.; Morozova, N.B.; Basova, T.V. Heterostructures Based on Cobalt Phthalocyanine Films Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles for the Detection of Low Concentrations of Ammonia and Nitric Oxide. Biosensors 2022, 12, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Chang, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, P.; Pinna, N.; Zhang, J. PdRh-Sensitized Iron Oxide Ultrathin Film Sensors and Mechanistic Investigation by Operando TEM and DFT Calculation. Small 2023, 19, 2301485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L. Thin-Film Deposition: Principles and Practice; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; 617p. [Google Scholar]

- Vanables, J.A. Introduction to Surface and Thin Film Processes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; 372p. [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovskii, V.G. Nucleation Theory and Growth of Nanostructures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; 601p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozovoy, K.A.; Korotaev, A.G.; Kokhanenko, A.P.; Dirko, V.V.; Voitsekhovskii, A.V. Kinetics of epitaxial formation of nanostructures by Frank–van der Merwe, Volmer–Weber and Stranski–Krastanow growth modes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 384, 125289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagmut, A.G. Layer, island and dendrite crystallizations of amorphous films as analogs of Frank-van der Merwe, Volmer-Weber and Stranski-Krastanov growth modes. Funct. Mater. 2019, 26, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmer, G.N.; Huang, H.; Roland, C. Thin film deposition: Fundamentals and modeling. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1998, 12, 354–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, W.W. Theory of Thermal Grooving. J. Appl. Phys. 1957, 28, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, S.; Gan, C.L.; Boey, F.; Mirkin, C.A.; Zhang, H. Synthesis of hexagonal close-packed gold nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Luo, J.; Zhu, J. Size Effect on the Crystal Structure of Silver Nanowires. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, J.; Okasinski, J.S.; Miller, D.J. Ambient-stable tetragonal phase in silver nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wormeester, H.; Hüger, E.; Bauer, E. hcp and bcc Cu and Pd Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 1540–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, R.; Etzkorn, M.; Kumar, P.S.A.; Ibach, H.; Kirschner, J. Spin-polarized electron energy loss spectroscopy of high energy, large wave vector spin waves in ultrathin fcc co films on Cu(001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 147201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmuller, S.J.; Vaz, C.A.F.; Ström, V.; Moutafis, C.; Tse, D.H.Y.; Gürtler, C.M.; Kläui, M.; Bland, J.A.C.; Cui, Z. Effect of substrate roughness on the magnetic properties of thin fcc Co films. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 054429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, G.A. Stabilization of bcc Co via Epitaxial Growth on GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 54, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.A.C.; Bateson, R.D.; Riedi, P.C.; Graham, R.G.; Lauter, H.J.; Penfold, J.; Shackleton, C. Magnetic properties of bcc Co films. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 69, 4989–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkov, S.M.; Zhigalov, V.S.; Frolov, G.I. A Hexagonal Close Packed Phase in Nickel Films. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 1996, 81, 328–330. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Yue, G.-H..; Peng, D.-L.; Luo, X. Preparation of hexagonal close-packed nickel nanoparticles via a thermal decomposition approach using nickel acetate tetrahydrate as a precursor. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 476, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Azmat, M.U.; Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, G. Controllable synthesis of hexagonal close-packed nickel nanoparticles under high nickel concentration and its catalytic properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 4606–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, H.; Kondo, K. Modified phases of diamond formed under shock compression and rapid quenching. Science 1991, 253, 772–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarkov, S.M.; Titarenko, Y.N.; Churilov, G.N. Electron microscopy studies of fcc carbon particles. Carbon 1998, 36, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyashin, I.; Muydinov, R.; Cammarata, A.; Bondarev, A.; Rusu, M.; Koliogiorgos, A.; Polcar, T.; Twitchen, D.; Colard, P.-O.; Szyszka, B.; et al. Face-centered cubic carbon as a fourth basic carbon allotrope with properties of intrinsic semiconductors and ultra-wide bandgap. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ino, S. Stability of multiply-twinned particles. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1969, 27, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ino, S. Epitaxial growth of metals on rocksalt faces cleaved in vacuum. II. Orientation and structure of gold particles formed in ultrahigh vacuum. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1966, 21, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.P.; Chaudhary, M.; Pasricha, R.; Ahmad, A.; Sastry, M. Synthesis of Gold Nanotriangles and Silver Nanoparticles Using Aloevera Plant Extract. Biotechnol. Prog. 2008, 22, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönecker, S.; Li, X.; Richter, M.; Vitos, L. Lattice dynamics and metastability of fcc metals in the hcp structure and the crucial role of spin-orbit coupling in Pt. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 224305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffat, P.H.; Borrel, J.P. Size Effect on the Melting Temperature of Gold Particles. Phys. Rev. A 1976, 13, 2287–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustis, S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Why gold nanoparticles are more precious than pretty gold: Noble metal surface plasmon resonance and its enhancement of the radiative and nonradiative properties of nanocrystals of different shapes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Pal, T. Interparticle coupling effect on the surface plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles: From theory to applications. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4797–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Xie, Y.; Jia, P.; Hayashi, K. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Gas Sensor Based on Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Coated Au Nano-Island Films: Influence of Nanostructure on Sensing Characteristics. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 3532–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhny, G.; Vaskevich, A.; Schneeweiss, M.A.; Rubinstein, I. Transmission Surface-Plasmon Resonance (T-SPR) Measurements for Monitoring Adsorption on Ultrathin Gold Island Films. Chem. A Eur. J. 2002, 8, 3849–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-C.; Lin, S.-J.; Lin, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-S.; Lu, Y.-J. Size effect of Ag nanoparticles on surface plasmon resonance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 5339–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, N.; Mitra, A. Influence of temperature dependent morphology on localized surface plasmon resonance in ultra-thin silver island films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 285, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Tazawa, M.; Jin, P.; Nakao, S.; Yoshimura, K. Wavelength tuning of surface plasmon resonance using dielectric layers on silver island films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 3811–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, G.; Prasad, P.N.; Swihart, M.T. Synthesis of Monodisperse Au, Ag, and Au–Ag Alloy Nanoparticles with Tunable Size and Surface Plasmon Resonance Frequency. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 4098–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ren, X.; Chen, D.; Tang, F.; Ren, J. Bimetallic Ag–Pt hollow nanoparticles: Synthesis and tunable surface plasmon resonance. Scr. Mater. 2007, 57, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Kunwar, S.; Pandey, P.; Lee, J. Strongly confined localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) bands of Pt, AgPt, AgAuPt nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Rui, M.; Zeng, H. Localized surface plasmon resonance of Cu nanoparticles by laser ablation in liquid media. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 79738–79745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, I.S.; Petrov, D.A.; Ivantsov, R.D.; Zharkov, S.M.; Velikanov, D.A.; Gumarov, G.G.; Nuzhdin, V.I.; Valeev, V.F.; Stepanov, A.L. Study of morphology, magnetic properties, and visible magnetic circular dichroism of Ni nanoparticles synthesized in SiO2 by ion implantation. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 115435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Rani, M.; Sharma, N.K.; Sajal, V. Sensitivity enhancement of a SPR based fiber optic sensor utilizing Pt layer. Optik 2015, 126, 4636–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Arce, A.S.; Nilsson, S.; Albinsson, D.; Hellberg, L.; Alekseeva, S.; Langhammer, C. In Situ Plasmonic Nanospectroscopy of the CO Oxidation Reaction over Single Pt Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6090−6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, S.; Sui, M.; Pandey, P.; Gu, Z.; Pandit, S.; Lee, J. Improved Configuration and LSPR Response of Platinum Nanoparticles via Enhanced Solid State Dewetting of In-Pt Bilayers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homola, J. Surface plasmon resonance sensors for detection of chemical and biological species. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 462–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, J.A.; Evans, B.L.; Maaroof, A.I. Analysis of island-size distributions in ultrathin metallic films. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 13863–13871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maaroof, A.I.; Evans, B.L. Onset of electrical conduction in Pt and Ni films. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 76, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomann, A.L.; Brault, P.; Rozenbaum, J.P.; Andreazza-Vignolle, C.; Andreazza, P.; Estrade-Szwarckopf, H.; Rousseau, B.; Babonneau, D.; Blondiaux, G. Chemical and morphological characterization of Pd aggregates grown by plasma sputter deposition. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1997, 30, 3197–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustsson, J.S.; Arnalds, U.B.; Ingason, A.S.; Gylfason, K.B.; Johnsen, K.; Olafsson, S.; Gudmundsson, J.T. Growth, coalescence, and electrical resistivity of thin Pt films grown by dc magnetron sputtering on SiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 7356–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Evans, B.L.; Flynn, D.I.; En, C. The study of island growth of ion beam sputtered metal films by digital image processing. Thin Solid Films 1994, 238, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed.; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; 2670p, ISBN 978-1498754286. [Google Scholar]

- Bakonyi, I. Accounting for the resistivity contribution of grain boundaries in metals: Critical analysis of reported experimental and theoretical data for Ni and Cu. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Shin, K.W.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, K.-B. Scaling Properties of Ru, Rh, and Ir for Future Generation Metallization. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2023, 11, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, T. Lattice defects and the electrical resistivity of metals. Adv. Phys. 1954, 3, 26–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seriani, N.; Jin, Z.; Pompe, W.; Ciacchi, L.C. Density functional theory study of platinum oxides: From infinite crystals to nanoscopic particles. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 155421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, J.A.; Wilding, A. Scaling Theory of Island Growth in Thin Films. Europhys. Lett. 1991, 16, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinrück, H.-P.; Pesty, F.; Zhang, L.; Madey, T.E. Ultrathin films of Pt on TiO2(110): Growth and chemisorption-induced surfactant effects. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamara, O.; Snoeck, E.; Respaud, M.; Blon, T. Growth of platinum ultrathin films on Al2O3(0001). Surf. Sci. 2011, 605, 1906–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreazza, P.; Andreazza-Vignolle, C.; Rozenbaum, J.P.; Thomann, A.L.; Brault, P. Nucleation and initial growth of platinum islands by plasma sputter deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 151–152, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, A.; Oka, N.; Nakamura, S.; Shigesato, Y. Visible-light active photocatalytic WO3 films loaded with Pt nanoparticles deposited by sputtering. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 5082–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Evans, B.L. Nucleation and growth of ion beam sputtered metal films. J. Mater. Sci. 1992, 27, 3108–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwoebel, R.L.; Shipsey, E.J. Step Motion on Crystal Surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1966, 37, 3682–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, D. Initial Stages of Thin Film Growth in the Presence of Island-Edge Barriers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, L.Ç.; Sanborn, C.; Anzenberg, E.; Ludwig, K.F. Evidence for Family-Meakin Dynamical Scaling in Island Growth and Coalescence during Vapor Phase Deposition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family, F.; Meakin, P. Kinetics of droplet growth processes: Simulations, theory, and experiments. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 40, 3836–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarakinos, K. A review on morphological evolution of thin metal films on weakly-interacting substrates. Thin Solid Films 2019, 688, 137312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunin, R.R.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Zharkov, S.M. Structural phase transformations in Al/Pt bilayer thin films during the solid-state reaction. Phys. Solid State 2018, 60, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseenko, E.T.; Yumashev, V.V.; Altunin, R.R.; Solovyov, L.A.; Belousov, O.V.; Zharkov, S.M. Kinetics of intermetallic phase formation in multilayer Al/Pt thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1047, 185110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunin, R.R.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Zharkov, S.M. Kinetics of diffusion and phase formation during solid-state reaction in Al/Au thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkov, S.M.; Altunin, R.R.; Yumashev, V.V.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Belousov, O.V.; Solovyov, L.A.; Volochaev, M.N.; Zeer, G.M. Kinetic study of solid state reaction in Ag/Al multilayer thin films by in situ electron diffraction and simultaneous thermal analysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 871, 159474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseenko, E.T.; Altunin, R.R.; Zharkov, S.M. In situ electron diffraction and resistivity characterization of solid state reaction process in Al/Cu bilayer thin films. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseenko, E.T.; Yumashev, V.V.; Altunin, R.R.; Solovyov, L.A.; Volochaev, M.N.; Belousov, O.V.; Zharkov, S.M. Thermokinetic study of intermetallic phase formation in an Al/Cu multilayer thin film system. Materialia 2023, 28, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunin, R.R.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Zharkov, S.M. Structural phase transformations during a solid-state reaction in a bilayer Al/Fe thin-film nanosystem. Phys. Solid State 2020, 62, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkov, S.M.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Altunin, R.R.; Nikolaeva, N.S.; Zhigalov, V.S.; Myagkov, V.G. Study of solid-state reactions and order-disorder transitions in Pd/α-Fe(001) thin films. JETP Lett. 2014, 99, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkov, S.M.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Altunin, R.R. L10 ordered phase formation at solid state reactions in Cu/Au and Fe/Pd thin films. Phys. Solid State Chem. 2019, 269, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseenko, E.T.; Yumashev, V.V.; Altunin, R.R.; Zeer, G.M.; Nikolaeva, N.S.; Belousov, O.V.; Zharkov, S.M. Solid-state reaction in Cu/a-Si nanolayers: A comparative study of STA and electron diffraction data. Materials 2022, 15, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myagkov, V.G.; Zhigalov, V.S.; Bykova, L.E.; Zharkov, S.M.; Matsynin, A.A.; Volochaev, M.N.; Tambasov, I.A.; Bondarenko, G.N. Thermite synthesis and characterization of Co–ZrO2 ferromagnetic nanocomposite thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 665, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkov, S.M.; Yumashev, V.V.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Altunin, R.R.; Solovyov, L.A.; Volochaev, M.N.; Zeer, G.M.; Nikolaeva, N.S.; Belousov, O.V. Thermokinetic study of aluminum-induced crystallization of a-Si: The effect of Al layer thickness. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moiseenko, E.T.; Yumashev, V.V.; Altunin, R.R.; Solovyov, L.A.; Zharkov, S.M. Kinetic study of a-Si crystallization induced by an intermetallic compound. Vacuum 2025, 232, 113877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average Pt Film Thickness t, nm | Average Crystallite Size <D>, nm | Fractional Surface Coverage θ, % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 1.5 | 13 |

| 0.5 | 2.4 | 31 |

| 0.7 | 2.7 | 34 |

| 1.0 | 3.0 | 51 |

| 1.4 | 3.6 | 66 |

| 2.0 | 4.4 | 95 |

| 3.0 | 4.7 | 100 |

| Reaction | Air Pressure, Torr | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 770 | 77 | 0.77 | 7.7 × 10−3 | 5 × 10−6 | 1 × 10−6 | |

| Onset Temperature of the Reaction, °C | ||||||

| 2PtO = 2Pt + O2 | 480 | 411 | 305 | 227 | 155 | 138 |

| PtO2 = Pt + O2 | 430 | 366 | 267 | 195 | 128 | 112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Altunin, R.R.; Moiseenko, E.T.; Nemtsev, I.V.; Lukyanenko, A.V.; Rautskii, M.V.; Tarasov, A.S.; Gerasimov, V.S.; Belousov, O.V.; Zharkov, S.M. Thickness Effect on Structural, Electrical, and Optical Properties of Ultrathin Platinum Films. Molecules 2025, 30, 4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244794

Altunin RR, Moiseenko ET, Nemtsev IV, Lukyanenko AV, Rautskii MV, Tarasov AS, Gerasimov VS, Belousov OV, Zharkov SM. Thickness Effect on Structural, Electrical, and Optical Properties of Ultrathin Platinum Films. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244794

Chicago/Turabian StyleAltunin, Roman R., Evgeny T. Moiseenko, Ivan V. Nemtsev, Anna V. Lukyanenko, Mikhail V. Rautskii, Anton S. Tarasov, Valeriy S. Gerasimov, Oleg V. Belousov, and Sergey M. Zharkov. 2025. "Thickness Effect on Structural, Electrical, and Optical Properties of Ultrathin Platinum Films" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244794

APA StyleAltunin, R. R., Moiseenko, E. T., Nemtsev, I. V., Lukyanenko, A. V., Rautskii, M. V., Tarasov, A. S., Gerasimov, V. S., Belousov, O. V., & Zharkov, S. M. (2025). Thickness Effect on Structural, Electrical, and Optical Properties of Ultrathin Platinum Films. Molecules, 30(24), 4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244794