Abstract

This review explores the integration of Boron-Dipyrromethene (BODIPY) dyes within Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs), highlighting their combined potential in various applications. MOFs, with their high porosity and structural versatility, provide an ideal platform to enable applications with BODIPYs, which otherwise remain challenging in the solid state. The article discusses different strategies for incorporating BODIPYs into MOFs, including their use as monodentate, bidentate, and tridentate ligands, as well as covalent attachment and non-coordinating encapsulation. The resulting hybrid materials exhibit enhanced properties suitable for applications in the luminescent materials/light harvesting, photodynamic therapy, sensing, and photocatalysis areas. The review emphasizes the importance of synthetic conditions, characterization techniques, and the quantification of BODIPY loading to ensure the integrity and functionality of the MOF structures.

1. Introduction

This short comprehensive review of the literature published up to October 2025 deals with the interplay between two hot research areas, BODIPYs as exquisite molecular fluorophores and Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) as host materials. Before discussing the complete series of examples from this specific but rapidly expanding research area, we will first introduce BODIPYs and their applications that could benefit from a hybrid materials approach and then MOFs. This topic has only been covered partially in previous reviews [1,2,3].

In this review, we will shortly introduce both BODIPYs and MOFs, before reviewing the literature with an emphasis on synthetic conditions and materials characterization (with the scope of both verifying and quantifying the inclusion of BODIPY and the integrity of the MOF). The applications will also be briefly discussed and used to organize the examples thematically.

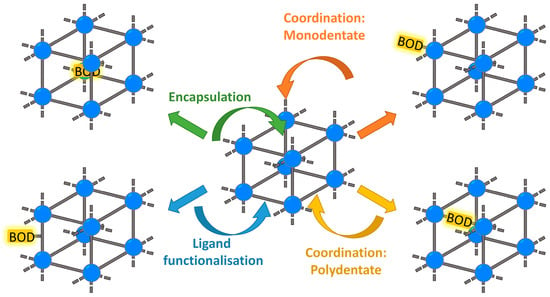

Four different approaches will be discussed in this review: monodentate coordination (Section 2.1), polydentate coordination (Section 2.2 and Section 2.3), covalent ligand functionalization (Section 3), and encapsulation (Section 4). They are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of synthetic strategies for BODIPY@MOF materials. Lines: organic linkers. Balls: metallic nodes.

1.1. BODIPYs and Their Applications

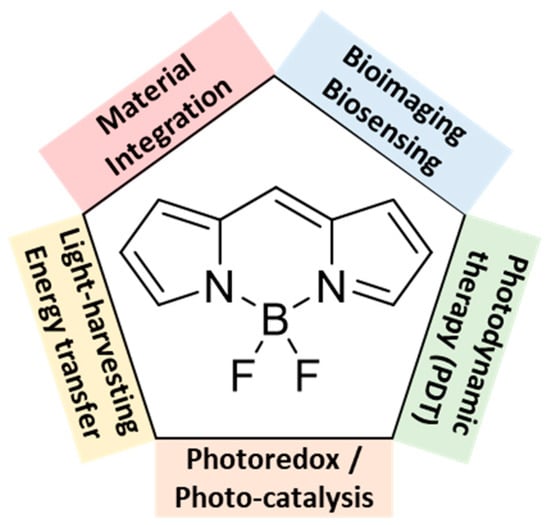

Boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) dyes constitute one of the most widely studied families of fluorophores owing to their outstanding photophysical and chemical properties. They typically exhibit intense absorption bands, narrow emission profiles with high fluorescence quantum yields in solution. They are usually associated with small Stokes shifts, which might be a limitation for some applications. In addition, BODIPY derivatives exhibit remarkable stability and tolerate a wide range of chemical environments, a property that largely accounts for their successful use in biological systems [4]. The wide range of applications of BODIPY dyes, spanning from bioimaging to photonic and hybrid materials, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Main application of BODIPY dyes.

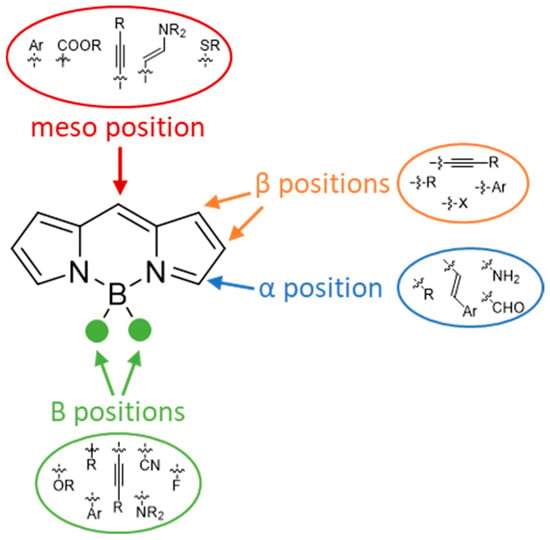

A key advantage of BODIPY dyes lies in their remarkable structural tunability. The dipyrromethene core can be decorated at multiple positions with a wide range of substituents, providing straightforward access to derivatives with tailored properties. The most common substitution sites and typical functionalization patterns of BODIPY dyes are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structure of the BODIPY core highlighting the main substitution positions (meso, α-, β-, and boron sites) commonly used to tune photophysical and chemical properties.

Substitution at the meso position is commonly used to introduce functional handles for conjugation. Substituents at the α- and β-positions can modulate electronic properties, control photophysical behaviour, and extend conjugation, enabling bathochromic shifts in the spectra [5]. Furthermore, functionalization at the boron centre itself allows additional modulation of stability and solubility. This high degree of modularity makes it possible to design BODIPY dyes with customized optical properties [6].

Despite these advantages, BODIPY dyes, like many organic fluorophores, suffer from a significant drawback for solid-state applications; their fluorescence is often quenched in the solid state due to aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ). Strong π–π stacking interactions between BODIPY chromophores can lead to non-radiative deactivation pathways, resulting in quenched fluorescence at high concentrations or in condensed phases. This limitation restricts their direct use in solid-state optical materials and has motivated the development of strategies to suppress ACQ, such as chemical modification, aggregation-induced emission (AIE) design, or incorporation into host matrices [7,8].

Through appropriate decoration and functionalization, BODIPY dyes have been adapted for a wide spectrum of applications. They have found extensive use in bioimaging and chemical sensing, where their sharp emission profiles and high brightness are particularly advantageous. Their ability to generate reactive oxygen species has also made them attractive candidates for photodynamic therapy (PDT), especially for halogenated BODIPYs [9]. In addition, BODIPYs are increasingly explored as efficient light-harvesting antennas in energy transfer processes and as active components in photocatalysis and optoelectronic devices [10,11,12,13]. Most importantly, the introduction of functional groups such as carboxylates or pyridyl substituents provides anchoring sites that can be exploited for integration into hybrid materials, including coordination polymers and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs).

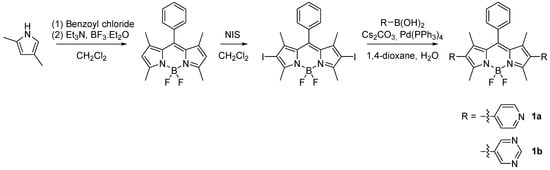

In this context, the association of BODIPY dyes with metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome the intrinsic limitations of these fluorophores in the solid state. MOFs provide well-defined porous architectures (see next subsection) that spatially isolate the chromophores, thereby suppressing aggregation-caused quenching and preserving the high fluorescence efficiency of BODIPYs. Their tunable chemical environment also enhances the stability of the dyes and enables fine control over their photophysical and photochemical behaviour. Furthermore, the easy introduction of anchoring (coordinating) groups on BODIPY derivatives facilitates their integration into MOF structures, giving rise to hybrid materials that combine the optical performance of BODIPYs with the versatility of MOFs for sensing, photocatalysis, and light-harvesting applications. The BODIPY chromophores discussed in this review are, for the most part, synthesized using the classical route to BODIPY dyes, which involves constructing a dipyrromethene intermediate followed by BF2 complexation [6]. Owing to its reliability and functional-group tolerance, this method remains the dominant approach for accessing the derivatives later incorporated into MOF systems. β-Functionalisation is most commonly achieved through halogenation (Br or I), providing reactive sites for diversification via cross-coupling reactions such as Suzuki–Miyaura or Sonogashira couplings. An example of this synthetic pathway for one of the most used BODIPY-derived ligands [14] is shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Classical BODIPY synthesis and common β-functionalisation pathways, exemplified for BODIPYs 1a and 1b.

Finally, α-methyl groups can be functionalized through Knoevenagel-type condensations, extending the π-conjugation and inducing a bathochromic shift in the absorption and emission wavelengths [5].

1.2. Metal–Organic Frameworks: General Considerations and Applications

Discovered in the late 20th century, Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are hybrid materials combining organic and inorganic components. They consist of metal nodes (metal ions or clusters) acting as Lewis acids, and organic ligands that are at least bidentate and non-chelating, considered as Lewis bases [15]. MOFs are thus three-dimensional coordination polymers based on metal-ligand bonds and exhibit well-defined crystalline structures. These materials are distinguished by their high porosity, which allows them to capture various molecules such as solvents, gases, pollutants, etc. [16]. The pioneering work in this field has very recently earned Richard Robson, Susumu Kitagawa, and Omar Yaghi the 2025 Nobel Prize for the development of these innovative materials. While an exhaustive introduction of the field of MOFs (more than 65,000 references as of October 2025) is completely outside the scope of this review, we will focus herein on some of their core characteristics, as well as their applications to illustrate the possible synergies with the BODIPY guests described in the following sections.

MOFs come in several families with various common names. In some cases, their names refer to the institution where they were discovered, such as the University of Oslo (UiO) or Matériaux de l’Institut Lavoisier (MIL). Others; however, provide insights into their structure. This is particularly the case for the Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF) family, whose three-dimensional network is topologically very similar to that of zeolites. These materials have metal nodes composed of a tetrahedral metal and imidazolate ligands. The family of Porous Coordination Networks (PCN) is a porous network with a stereo-octahedron geometry, often associated with porphyrin-centred ligands; PCN-222 is a representative example [17]. Porous Coordination Polymers (PCPs) also belong to the large family of MOFs. They are distinguished by the use of carboxylate and pyridinic ligands associated with transition metals. Finally, another particular class is that of Isoreticular Metal–Organic Frameworks (IRMOF), which are isoreticular to MOF-5, also known as IRMOF-1. These MOFs use aromatic ligands, such as terephthalic acid, and present similar topologies, differing mainly by the substitutions on the aromatic ring [18].

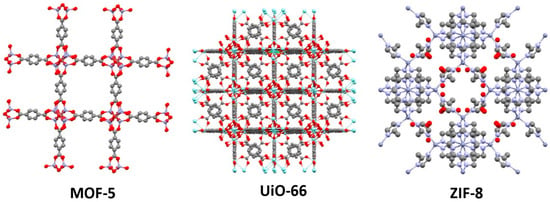

Among the many listed MOFs, MOF-5, UiO-66, and ZIF-8 (Figure 4) are some of the most frequently studied. We will detail here some elements of their structure as representative examples. MOF-5, with the formula Zn4O(C8H6O4)3, consists of tetrahedral zinc clusters {Zn4O}6+ connected by terephthalate ligands. Its crystalline structure forms an extended three-dimensional cubic network. This MOF was reported by O. Yaghi’s group in 1999 [19]. UiO-66, synthesized by K. Lillerud in 2008 at the University of Oslo, has the formula Zr6O4(OH)4(C8H4O4)6 [20]. It is composed of zirconium metal clusters (Zr4+) connected by terephthalate ligands. Its crystalline structure exhibits a face-centred cubic (fcc) geometry. UiO-66 is renowned for its robustness, particularly its resistance to various solvents such as water (except at extreme pH), DMF, or acetone. Finally, ZIF-8 (Figure 4), discovered in 2006 by O. Yaghi, with the formula Zn(C4H6N2)2, consists of Zn2+ ions connected by 2-methylimidazole ligands. It is archetypal of the ZIF family (see above) [21]. This material is distinguished by its stability in water and at high temperatures (550 °C), and also presents good chemical stability.

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of archetypical MOFs (CCDC numbers): MOF-5 (256965) [22], UiO-66 (733458) [20], and ZIF-8 (602542) [21]. Figure generated with Mercury software 4.0 [23].

MOFs generally have relatively harsh synthesis methods compared to usual organic synthesis. Indeed, they are often obtained by solvothermal synthesis, a technique performed at high temperature and pressure in sealed autoclaves [24]. The temperature used is generally above the boiling point of the solvent with added pressure, which allows the dissolution of all precursors (even the most difficult to dissolve), and provides crystallization conditions similar to those governing the geological formation of minerals. However, some MOFs can also be obtained by slow vapour diffusion. This technique consists of dissolving the reagents in a solvent A, and then placing this solution in a closed container together with solvent B, in which the solubility of the product is reduced. Examples for MOF-5 (in this particular case, the vapour diffusion brings a weak base to the reaction medium), UiO-66, and ZIF-8 are presented in Table 1. These processes improve the crystallinity of the MOF, and solvothermally synthesized MOFs are generally more crystalline than those obtained under milder conditions [25]. However, hydrothermal conditions might be challenging for organic fluorophore guests such as BODIPYs. Moreover, when organic linkers of the MOF consist of carboxylates and are introduced in the synthesis in their protonated state, the synthetic conditions imply Brønsted acidity in addition to the Lewis acidity of the metal precursors. Both of them can prove challenging to BODIPYs. However, alternative milder methods are now being studied to avoid the harsh solvothermal conditions. For example, MOF-5 can be synthesized at room temperature in the presence of a weak base, triethylamine, according to a method published by Yaghi [26]. Other synthesis processes in aqueous media are also now documented [27].

Table 1.

Synthetic conditions of the MOF-5, UiO-66, and ZIF-8.

MOFs are known for their numerous applications, particularly in gas or solvent capture. Due to their exceptionally high porosity, they are capable of selectively or non-selectively capturing various gases, thus enabling gas separation. Additionally, these materials can act as solvent traps, generally by occupying the cavities or channels of the porous structure [29,30]. Another frequently studied application is catalysis, and more specifically, photocatalysis. Some MOFs, due to their photochemical properties, can thus be used as photocatalysts [31,32]. In some cases, MOFs also exhibit interesting luminescence properties for detection applications [33,34]. This luminescence can originate from the ligand, if it is a fluorophore, or from the metal if it has emissive properties. Charge transfer from the metal to the ligand or vice versa can also induce material emission [35,36]. The interested reader is referred to further specialized reviews (e.g., [37,38,39,40,41,42]).

2. BODIPYs as Ligands

This section focuses on BODIPY@MOF materials, where BODIPY has been modified to confer coordinating properties. The examples will be organized by increasing denticity of the BODIPY ligand.

2.1. Monodentate Ligands

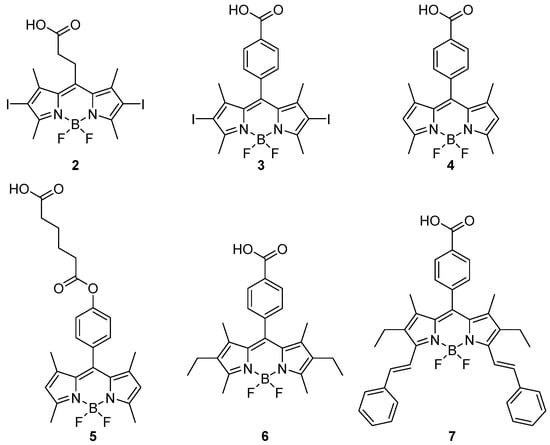

In order to incorporate BODIPY into MOF structures, some groups have chosen to functionalize BODIPY by adding a single coordinating arm (BODIPY 2–7 depicted in Scheme 2). Synthetically, the meso position is the most easily modifiable. This approach allows the fluorophore to be integrated as a monodentate ligand within the structure for various applications. However, from a thermodynamic perspective, the substitution within the MOF of polydentate ligands with monodentate ones is highly unfavourable. To overcome this hurdle, coordination to additional node sites—i.e., those not occupied by the MOF linkers—or to sites resulting from defects can be considered. For this subsection, synthetic strategies and results in terms of BODIPY incorporation (specifically important in this case as no defined stoichiometry is expected) are summarized in Table 2. The synthetic conditions highlight that, whatever the incorporation procedure, mild conditions compatible with the BODIPY chromophore were used, a distinctive feature that differs markedly from standard MOF synthesis conditions (typically, high-temperature solvothermal).

Scheme 2.

Monodentate BODIPYs 2–7.

Table 2.

Overview of synthetic conditions, quantification of BODIPY, and applications for MOFs containing monodentate BODIPYs.

In many cases, these applications relate to the biomedical field, such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) or the development of antibacterial systems. For instance, Xie et al. reported in 2016 the formation of a material capable of acting as an anticancer agent [43]. In this study, BODIPY 2 was functionalized with a 2-carboxyethyl group at the meso position and two iodine atoms at the β positions. This BODIPY was immobilized within a nanoscale UiO-66-type MOF, which has the formula Zr6O4(OH)4(C8H4O4)6 and features Zr4+ metal clusters connected by terephthalate linkers [20]. BODIPY 2 was incorporated into the structure using the solvent-assisted ligand exchange (SALE) method—a post-synthetic approach allowing the exchange of one ligand for another. In this case, the ditopic terephthalate ligand was partially replaced by the monotopic BODIPY. After the SALE procedure, the material was washed multiple times with (DMF, MeOH) to remove any BODIPY molecules trapped within the pores. Incorporation was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with elemental mapping of iodine, revealing a relatively homogeneous distribution. Additionally, the decrease in specific surface area from 1591 m2/g to 1422 m2/g after SALE is consistent with successful incorporation. The appearance of two characteristic signals of 2 in the IR and solid-state 1H NMR spectra. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and UV-Vis analysis of the washing solutions allowed quantification of the BODIPY within the structure. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analyses showed that this modification had minimal impact on the MOFs’ crystalline structure. Biological tests demonstrated that the material exhibits good biocompatibility in the dark, significant photosensitivity and cellular uptake, and a notable ability to generate singlet oxygen (1O2). Under irradiation, 2@UiO-66 effectively reduced the viability of B16F10, CT26, and C26 cancer cells.

In 2019, Gupta et al. reported BODIPY 3 functionalized with a carboxylate group at the meso position and iodine atoms at the β positions [44]. This derivative was incorporated via solvent-assisted ligand incorporation (SALI). Unlike the previously mentioned SALE approach, 3 was directly coordinated to the preformed MOF cluster in nanoscale PCN-222 [17], a material with the formula Zr6O8(OH)8(C48H30N4O8)2, where Zr4+-containing metal clusters are connected by tetradentate porphyrin linkers. The material was washed (acetone/methanol, then acetone) to remove any uncoordinated BODIPY, confirming that the remaining 3 in the MOF was complexed. Again, the specific surface area decreased in the presence of BODIPY, from 1755 m2/g to 1015 m2/g. NMR analysis after degradation (D2SO4 (10%) in DMSO-d6) revealed the presence of BODIPY 3 within the structure. Quantitative analysis indicated a ratio per Zr6 cluster of 8 porphyrins to 3.5 BODIPYs, corresponding to 44% BODIPY relative to the porphyrins in the structure. Successful integration of BODIPY into the MOF was further confirmed by (the disappearance of the OH stretching of Zr clusters). The resulting material exhibited significant anticancer activity under irradiation, showing 10 to 20 times greater cytotoxicity against MCF-7 and B16F10 cancer cells compared to PCN-222 alone.

Shen, Linhardt et al. described in 2021 a synthesis of ZIF-90 modified with 4. Despite the low loading, PXRD showed deep structural modifications of the resulting material as compared to pristine ZIF-90, which can be related to the different coordination pattern of 4 as compared to imidazolate ligands. Nevertheless, the resulting material allowed the detection of protamine (arginine-rich protein) and heparin in solution, including in realistic conditions (serum) for the former [45].

In a publication focused on designing an antibacterial material, Qu et al. described in 2022 the use of the same BODIPY 4 functionalized with a carboxylate group at the meso position, which was then integrated as a monodentate ligand into a ZIF-8 MOF [46]. This MOF consists of Zn2+ ions connected by 2-methylimidazole (formula: Zn(C4H6N2)2) [21], aiming to develop a photosensitive antibacterial material. The synthesis of ZIF-8 was carried out under standard conditions, with BODIPY added after a certain time. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis of the resulting material still matched the diffraction peaks of pristine ZIF-8. SEM images revealed hexagonal particles with a diameter of approximately 350 nm for ZIF-8 and rough, hollow nanospheres of about 300 nm for 4@ZIF-8; these morphological changes were correlated with the integration of BODIPY into the structure. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed a homogeneous dispersion of 4 within the MOF structure. IR spectroscopy also highlighted the presence of 4 in the structure through observation of characteristic bands. The optical properties of the material were studied using UV-vis and photoluminescence spectroscopies, revealing an absorption peak centred at 465 nm and subsequent emission. Porosity analysis further demonstrated the integration of BODIPY, as the specific surface area decreased from 1351 m2/g for ZIF-8 to 612 m2/g for 4@ZIF-8. This material exhibited notable antibacterial activity, inhibiting the growth of E. coli and S. aureus after 1.5 h under illumination.

In an approach using photochemistry for chemical applications, Farha et al. described in 2017 a material active in photo-oxidation [47]. They integrated a BODIPY 5, modified with a carboxylate-bearing chain at the meso position, into the MOF NU-1000 [50] using the SALI method. This MOF is described by the formula Zr6O8(OH)8(C44H26O8)2 and consists of zirconium clusters connected by 1,3,6,8-tetra(4-carboxylphenyl)pyrene linkers. No extensive characterizations to confirm the insertion of BODIPY into the MOF have been reported. However, the analysis of the specific surface area indicated a significant decrease upon incorporation of 5, from 2100 m2/g to 1100 m2/g, suggesting successful integration. This assembly enabled the formation of a photocatalyst capable of detoxifying sulphur mustards.

In studies focusing on the optical properties of the fluorophore within the material, other applications have also been explored. For example, Kim et al. in 2020 investigated the Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) phenomenon between BODIPY and a porphyrin (tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin, TCPP) [48]. To achieve this, they incorporated BODIPY 4 and its diiodinated analogue 3 into a nanoscale MOF of the nPCN-222 type, which also contains {Zr6O8} nodes as in the previous example. They obtained nanoparticles in the form of small rods, with varying sizes depending on the composition; the control undoped nPCN-222 nanoparticles measure 72 nm in length, while the 4@nPCN-222 and 3@nPCN-222 nanoparticles measure 90 nm and 88 nm, respectively. The BODIPYs were incorporated via post-synthetic modification using the SALI method, with an excess relative to the MOF linker, which did not allow precise control of the amounts actually introduced into the MOF structure. NMR (decomposition in D2SO4 (10%)/DMSO-d6) was used to quantify the BODIPY relative to the porphyrins. The ratios of BODIPY to porphyrins per Zr6 cluster were 3.6 and 3.5 for 4@nPCN-222 and 3@nPCN-222, respectively. The authors studied the FRET phenomenon using luminescence spectroscopy and showed that the excitation of BODIPY at 500–600 nm could result in the emission of TCPP at 630–750 nm within the material.

In a different approach, Cisnetti et al. reported in 2023 a strategy to limit the ACQ (Aggregation-Caused Quenching) effect by diluting a BODIPY fluorophore in MOF-5 [49]. MOF-5 has the formula Zn4O(C8H6O4) and consists of zinc clusters connected by terephthalic acid [19]. To achieve this, the authors synthesized a BODIPY 6 functionalized at the meso position with a carboxylate (phenylene spacer) and attempted to integrate it into MOF-5 during synthesis. A room-temperature and neutralized (NEt3) procedure was chosen to ensure compatibility with 6 [26]. The fluorophore was incorporated directly during synthesis, adjusting its percentage relative to the linker. The resulting material was washed several times with chloroform to remove any uncoordinated BODIPY, confirming that the remaining 6 was indeed bound within the structure. The obtained MOF exhibited a pink colour and emitted green fluorescence (525 nm) while irradiated under UV light (365 nm). An additional control test was conducted by replacing 6 with a non-coordinating BODIPY (23, see Section 4), which did not yield a luminescent MOF, further confirming the coordination of 6 within the structure rather than mere encapsulation. The sample was characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), and the observed crystalline pattern matched the simulated pattern of MOF-5. The specific surface area was also measured, showing a 44% decrease between the control and doped MOF-5 samples, providing further evidence of the incorporation of 6. A second BODIPY 7, similar to 6 but functionalized with two aromatic arms at the α positions via Knoevenagel condensation with benzaldehyde, was also used. 6@MOF-5 exhibited a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 45% (external PLQY, accounting for absorption: 27.3%) for its best sample containing 10.6 wt-%. For 7, the optimal properties (52% PLQY and 16% ePLQY) were obtained for a sample containing 5.2% wt-% of BODIPY 7. For the sake of comparison, the authors measured the quantum yields of 6 and 7 in the synthetic medium (DMF/Et3N) and obtained 54 and 77%, respectively. This highlights that the MOF is allowed to obtain solid-state luminescence properties comparable to solution ones.

2.2. Bidentate Ligands: MOFs Containing Exclusively BODIPY Ligands

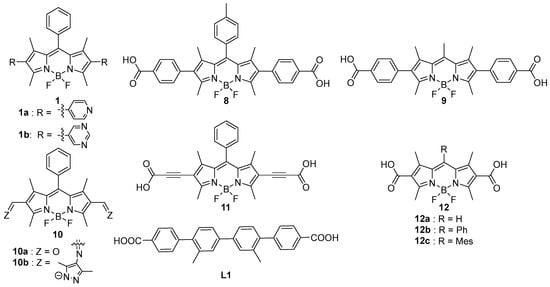

In this section, we will discuss examples of bidentate ligands centred on BODIPYs. All examples involve dual functionalization at the β positions, which ensures an angle close to 180° between the two coordinating functions (Scheme 3). Table 3 overviews the synthetic conditions used for the preparation of MOFs from these ligands. The reaction conditions are slightly harsher than the example discussed in the former subsection, to ensure crystallization. Indeed, in articles discussed within this subsection, the MOF is described by a precise chemical formula (assuming no structural defects), and most frequently, the proof of structure is provided by single-crystal crystallography (SCXRD), coupled with powder X-ray crystallography (PXRD) to prove phase purity.

Scheme 3.

Bidentate BODIPYs 1 and 8–11 functionalized and ligand L1 used along one of these in a single-crystal to single-crystal ligand exchange.

Table 3.

Overview of synthetic conditions, MOF characterization, and applications for MOFs containing bidentate BODIPYs.

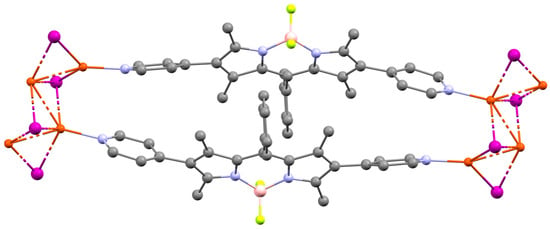

In a seminal research article focused on the impact of cluster differences on the structure and crystallinity of MOFs, Champness et al. used in 2019 two BODIPYs functionalized with two pyridines (1a) or two pyrimidines (1b) at the β positions [14]. Their reaction in the presence of copper(I) iodide led to the formation of Cu4I4 clusters in the presence of 1a, with which they formed one-dimensional chains. However, in the presence of 1b, the resulting clusters were Cu2I2, but in this case, alternating stacks of fluorophores and clusters are observed, generating a 3D network. Thus, this study illustrates how modifying the BODIPY functionalization allows control over the topology of the obtained structures. Additionally, photophysical studies were conducted showing the emission of BODIPYs in solution (PLQY of 86% for 1a and 90% for 1b in CH2Cl2 solution) and the loss of this luminescence once integrated into the material. To exemplify a structure typical of MOFs constructed exclusively from BODIPY linkers, the crystal structure of 1a/Cu4I4 is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Crystal structure of 1a/Cu4I4 CCDC number: 1920194 [14]. Figure generated with Mercury software [23].

With this type of ligand, some studies have focused on applications in photodynamic therapy (PDT). Meng et al. described in 2024 a BODIPY 8, substituted at the β position with a carboxylate group, which was then linked to rare earth ions (RE3+, RE = Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Eu, Gd, Tb, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu) to form a set of MOFs [51]. The structures were elucidated using single-crystal X-ray diffraction, revealing a three-dimensional structure where the metal centre has a coordination number of 8, with different phases for lanthanum and cerium on one hand, and for all the other tested ions on the other [52]. The authors thus developed a new PDT material that can be used with different rare earths in vitro on HeLa cancer cells as well as in vivo on tumours caused by these cells in mice. In vivo, 8@Gd-MOF showed good results in sonophotodynamic therapy (SPDT), reducing tumour volume by 86%. The same Gd-based MOF was used in another study by the same group, in combination with a heterostructure based on NaLnF4 nanoparticles capable of upconversion (808 nm → 515–564 nm) via a Nd3+ ⟶ Yb3+ ⟶ Er3+ cascade. The MOF was synthesized in situ on preformed nanoparticles. The overall system resulted in the excitation of BODIPY 8 via near-infrared (NIR) radiation, which has high tissue penetration. In vivo experiments demonstrated that 808 nm NIR light was more effective than visible light to reduce tumour volume in a murine model (90% reduction vs. 65% for 505 nm).

In another recent publication (2024), Fairen–Jimenez et al. first synthesized an isoreticular MOF to UiO-68 named 69-Me2 [57] with a ligand L1, then proceeded with ligand exchange using a bidentate BODIPY 9, functionalized at the β positions with paracarboxyphenyl groups [53]. To achieve this, the MOF 69-Me2 was incubated with 9, observing a complete visual change from colourless to red. To verify if all the ligands had been exchanged, they analyzed the degradation products of the MOF using 1H NMR, which demonstrated that 100% of the initial ligand had been substituted in what proved to be a single-crystal to single-crystal reaction. The authors then coated their MOF nanoparticles with fluorinated polyethylene glycol and integrated them into a hydrogel based on hydroxyethyl cellulose. This allowed the injection of the MOF containing 9 into a murine tumour. ROS were generated under irradiation by a green LED at 525 nm, leading to a tumour regression of up to 80%.

Photocatalysis is another application field that has been studied. Notably, Li et al. synthesized in 2023 a BODIPY 10a functionalized at the β positions with aldehyde groups and an aromatic cycle at the meso position [54]. Their strategy is original as the actual BODIPY ligand is assembled on preformed clusters via aldehyde-imine condensation. Indeed, 10a reacted initially with preformed copper(I) clusters Cu3L3, where L is a pyrazolate bearing a primary amine. Thereafter, during the MOF formation step, the aldehydes of 10a reacted with the primary amines of the clusters to form covalent imine bonds in 10b. The resulting MOF was named JNM-20. Its structure was modelled, although single-crystal structures were not reported. It was characterized by PXRD, consistent with the predicted model (albeit with limited crystallinity). NMR and IR analyses were performed to confirm the clear disappearance of the strong C=O bond (1665 cm−1) and the formation of the weak C=N bond (1616 cm−1). This material serves as a catalyst for synthetic interest. It combines a catalytic copper site with a photocatalytic site (10b) to enable the formation of 1O2. This material promotes the anti-Markovnikov transformation of terminal alkenes or alkynes into primary alcohols.

In 2025, Liu et al. recently published a study investigating the effect of cluster size on MOF structure [55]. A BODIPY 11, substituted at the β positions with alkynes bearing carboxylic acid groups (obtained via Sonogashira coupling with trimethylsilylacetylene followed by reaction with CO2), was reacted with a zirconium salt (ZrOCl2.8H2O), forming two types of clusters: (Zr6(µ3-O)4(µ3-OH)4) or (Zr12(µ3-O)8(µ3-OH)8(µ2-OH)6). Depending on the cluster size, the unit cell shape differed. For the former cluster, the unit cell was face-centred cubic, while for the latter, it was hexagonal close-packed. The materials were applied in the photocatalytic reduction in CO2 to CO. Under UV irradiation, both materials showed promising results with nearly 100% selectivity, yielding CO at 16.72 µmol g−1 h−1 for 11@Zr12 and 13.91 µmol g−1·h−1 for 11@Zr6.

In a comprehensive and very recent study (2025), Fairen–Jimenez et al. described various BODIPYs functionalized at the β positions with a carboxylic acid: 12. These BODIPYs act as ligands towards Zr6O4(OH)4 [56]. The BODIPY 12a, integrated into a MOF, was then post-functionalized with different groups at the α and free β positions. Knoevenagel-type condensation reactions with aldehydes allowed modification of the chromophore’s absorption, covering a large part of the visible spectrum. Finally, the same BODIPY 12a was combined with zirconium and other ions such as Sc3+, Ti4+, V4+, and Sn4+, leading to bimetallic clusters. The proportion of metal incorporated into each node relative to zirconium was determined by ICP-MS: 83% Sc, 87% Ti, 50% V, and 46% Sn. SEM analyses showed a uniform distribution of the various metals. These different functionalized materials were used in photocatalytic applications on tertiary aniline substrates under ordinary atmosphere: Csp3–H carbamoylation in the presence of isonitriles, or dealkylation/acylation in the presence of acyl chlorides or arenesulfonyl chlorides, with very satisfactory yields.

2.3. Bidentate Ligands: MOFs Containing BODIPY Ligands and Auxiliary Ligands

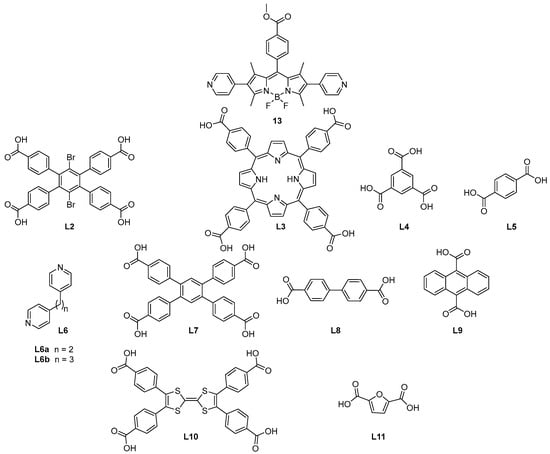

In this subsection, MOFs containing a coordinating bidentate BODIPY as well as a second non-BODIPY auxiliary ligand will be discussed. The resulting materials are supposed to contain the BODIPY and the auxiliary ligand in proportions defined by the compound’s stoichiometry—if defects are not considered. The BODIPY ligands considered within the studies reviewed in this subsection are essentially the same as for the previous subsection (except 13), while the auxiliary ligands are of varied structure, denticity, topology, and electronic properties (Scheme 4). The synthesis conditions are summarized in Table 4, as well as other key data. The same remarks as for Section 2.2 apply.

Scheme 4.

Auxiliary ligands L2–L11 are used along with bidentate BODIPYs for MOF design, as well as bidentate BODIPY 13.

Table 4.

Overview of synthetic conditions, MOF description and applications for MOFs containing bidentate BODIPYs.

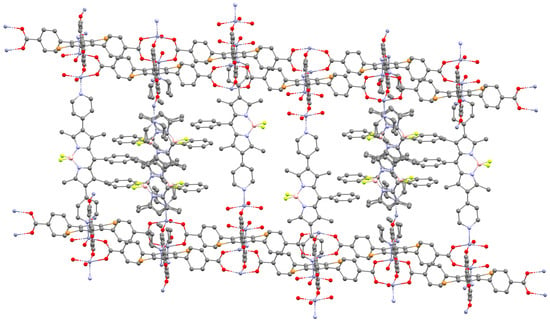

For this type of material, some studies have focused on its optical properties. In a foundational example reported in 2011, Farha et al. prepared 1a, and reacted it with zinc ions, in the presence of two different auxiliary ligands: 4-[2,5-dibromo-3,4,6-tris(4-carboxyphenyl)phenyl] benzoate (L2) and tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (L3): a one-pot method for L2, while the porphyrin L3 was pre-coordinated with zinc before the introduction of 1a [58]. The BODIPYs are perpendicular to the auxiliary ligands. For the L2-based MOF, the BODIPY is excited and emits at 596 nm with an excitation of 520 nm. However, for its L3 counterpart, the BODIPY performs an energy transfer (FRET) with the porphyrin, which emits at 667 nm. This allows obtaining a material that absorbs a large part of the visible spectrum while emitting a defined wavelength corresponding to the porphyrin. To exemplify a structure typical of MOFs constructed from BODIPYs and auxiliary ligands, the crystal structure of 1a@ZnL2 is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Crystal structure of 1a@ZnL2 CCDC number: 860288. Some BODIPYs display disorder. Figure generated with Mercury software [23].

Du et al. reported in 2013 a hybrid material with the same BODIPY 1a and a metal cluster composed of zinc with either 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate (L4) or terephthalate (L5) as the auxiliary ligand [59]. In both cases, a 3D structure was obtained, featuring two forms of pores, large, interpenetrated openings (361 Å2) and small cavities (72 Å2). The materials formed with L4 and L5 emit in the solid state at 540 nm (λexc = 512 nm), typical of BODIPY, but the properties were not studied in greater detail.

Hou et al. described in 2015, MOFs with BODIPY 12a, difunctionalized at the β position with a carboxylic acid function, coordinated to zinc or cadmium clusters, with different pyridine ligands L6a,b as auxiliary ligands [60]. The synthesis was carried out in a one-pot method using two equivalents of the auxiliary ligand relative to the fluorophore. The results show that the choice of metal or auxiliary ligand influences the final structure obtained, particularly the configuration of the clusters. In the case of cadmium, the impact of different solvents used during synthesis was also studied, revealing a direct influence on the optical properties of the obtained materials. Indeed, among the five compounds obtained, the maximum emission wavelengths varied from 573 nm to 602 nm (λexc = 450 nm). Additionally, the quantum yields were determined and differed among the reported examples, though they remained modest (PLQY = 0.67–1.7% for BODIPY@MOF materials, compared to 0.73% for 12a in the solid state).

Ju et al. recently reported in 2025 three MOFs, two of which incorporated 1a coordinated to a cadmium node [Cd2(COO)4] (COO groups belonging to the linkers) [61]. In the first case, the auxiliary ligand is a tetracarboxylated porphyrin L3 (which is also photoactive), and in the second case, it is 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)benzene (L7). The choice of the 1a and L3 ligands allowed Intrareticular Energy Transfer (IRET), from L7 to 1a. This process was very efficient with 88% energy transfer upon 545 nm excitation. By modifying indium tin oxide (ITO) electrodes with the MOFs, photocurrents were determined. IRET allowed photocurrent responses at wavelengths in the 460–550 nm range corresponding to the 1a absorption. The photoelectrochemical analysis was performed in the presence of sacrificial dopamine (reductant) and O2 (oxidant). Using the photoelectrochemical properties of the MOF containing 1a and L3, a biosensor for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor isoform 165 (VEGF165) was designed.

The next studies discussed will focus on electrochemical applications. Lei et al. investigated in 2022 the electrochemical behaviour of BODIPY-based MOFs in electrochemiluminescence (ECL)-based sensors. BODIPYs have been reported to be active in ECL (e.g., see ref. [69]). The authors used BODIPY 1a, coordinated to zinc(II) ions along with terephthalic acid L5 as an auxiliary ligand [62]. The synthesis was carried out in a one-pot method with one equiv. auxiliary ligand for two equiv. BODIPY. In the final structure, the BODIPYs are placed parallel to each other and perpendicular to the auxiliary ligand, with a 1a–1a distance far greater than in crystals of the pure compound. IR analysis identified the modification of the C=N stretching bands of the pyridine, highlighting the coordination of Zn with N. The distance and orderly arrangement in the MOF could reduce non-radiative deactivation and thus enhance the optical signal. Indeed, after electrochemical reduction, the radical anion form of the MOF was transformed into its excited emissive state after reaction with the sulphate radical anion in a process 24 times more efficient than for an aqueous solution of 1a. This was exploited in an ECL-based detection method of the biologically important protein telomerase.

Gupta et al. also described in 2023 the use of 1a, this time linked to cobalt(II) with 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate (L4) as the auxiliary ligand [63]. The obtained solid was characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, revealing alignments of BODIPY perpendicular to L4, connected by metal nodes consisting of a single Co2+ ion. This material was then incorporated into various carbon composites, enabling the formation of an electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reactions (OER). OERs are essential for sustainable energy solutions requiring water splitting; however, non-sustainable noble-metal-based catalysts define the state of the art currently. In their study, the authors demonstrated that their MOF outperformed IrO2, a benchmark OER catalyst.

In a PDT application, Meng et al. reported in 2021 a MOF based on the BODIPY 13 bearing pyridines at the first β position and a 4-(carboxymethyl)phenyl as meso substituent along with Cd2+ ions [64]. 4,4′-diphenyldicarboxylate (L8) is also present in the structure as an auxiliary ligand. The latter takes a position perpendicular to the BODIPY ligand, resulting in the formula Cd(L8)(13). The resulting porous material is loaded with the therapeutic agent DOX (doxorubicin, a DNA intercalator used as an anticancer drug). The authors then presented biological results indicating the theranostic potential of their DOX@MOF, as well as the complementarity of dynamic phototherapy (generation of 1O2 by the BODIPY) with chemotherapy by DOX.

In a 2021 study combining optical characterization and photocatalysis, Gupta et al. once again examined 1a, linked to zinc nodes, with anthracene dicarboxylate (L9) as the auxiliary ligand [65]. The synthesis was carried out in a one-pot method with 1a in a slight deficit relative to the auxiliary ligand. The two different ligands are positioned perpendicular to each other in the unit cell. The authors conducted preliminary photophysical characterization of the MOF. They demonstrated that BODIPY emission is observed when L9 is excited, and this is correlated with a significant decrease in luminescence lifetime (0.6 ns vs. 12 ns) and the photoluminescence quantum yield of the anthracene fluorophore (0.5% vs. 16%). Subsequently, they also showed that this MOF can be used in the photocatalytic oxidation of DHN (1,5-dihydroxynaphthalene) to juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), a molecule of therapeutic interest.

Finally, studies were focused on photocatalysis. In an article dealing with BODIPY 1a, as well as terephthalate L5, Wen, Peng, described a MOF containing a two-zinc node, Zn2(COO)4 (COO− from terephthalate). The MOF is threefold interpenetrated, and the authors named it CCNU-1. This material was then used in photocatalysis oriented toward the hydrogen evolution reaction. Indeed, a composite material was assembled with platinum(0) nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were synthesized by reduction in H2PtCl6 in the presence of CCNU-1. The authors provide both electrochemical and photophysical evidence of electron transfer to the Pd nanoparticles. This allowed the authors to report a very high activity of the photocatalyst (4680 µmolg−1h−1, with an apparent quantum efficiency of 9.06%) [60].

Wen et al. reported in 2024 the integration of BODIPY 1a into two different MOFs, one based on zinc and the other on cadmium. Both MOFs contained the auxiliary ligand 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylate (TDC) (L10) [67]. The authors used a one-pot synthesis, introducing two equivalents of H2TDC relative to the BODIPY. In the first case, zinc formed a bimetallic node involving four metal–ligand bonds, while cadmium generated a monometallic node with six metal-ligand bonds, resulting in [Zn2(1a)2(L10)2] and [Cd(1a)(L10)]∙2H2O. For Zn (but not for Cd), an interpenetrated structure was observed. These materials enabled the photocatalytic oxidation of thioanisole to sulfoxides and the hydroxylation of arylboronic acids. In both reactions, the Zn-containing MOF performed better.

Very recently, in 2025, Wen et al. again used the BODIPY 1a to integrate it into two different MOFs, one based on zinc and the other on cobalt [68]. Both MOFs contain an auxiliary ligand, tetrathiafulvalene-3,4,5,6-tetrakis(4-benzoate) (L11). They synthesized these MOFs using a one-pot method, with one equiv. of L11 for two equiv. of 1a. Single-crystal. This zinc-based MOF has an interpenetrated structure. The MOFs are used for the photocatalysis of various reactions, such as photoreductive dehalogenation and thiol oxidation. The authors demonstrated that the zinc-based MOF is more effective for reduction, while the cobalt-based MOF is more effective for oxidation.

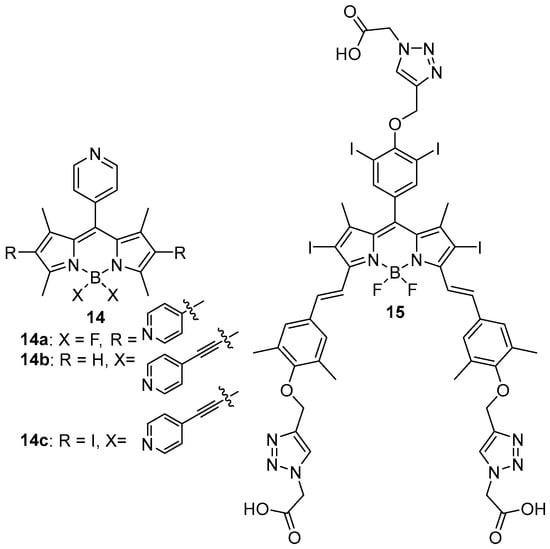

2.4. Tridentate Ligands

To this date, only two publications report the synthesis of MOF containing tridentate BODIPY ligands. The structures of these ligands are depicted in Scheme 5, and the synthesis and characterization details are given in Table 5. The same remarks as for Section 2.2 apply again.

Scheme 5.

Tridentate BODIPYs 14, 15.

Table 5.

Overview of synthetic conditions, MOF description, and applications for MOFs containing tridentate BODIPYs.

Zang et al., in 2023, described the synthesis of a MOF consisting of silver clusters (Ag12(StBu)6(CF3COO)6), connected by three different tridentate BODIPY ligands 14a–c [70]. Ligand 14a is functionalized with three pyridine groups, one at the meso position and two others at the β positions. Ligand 14b is also functionalized with a pyridine at the meso position, but the other two pyridines replace the fluorine atoms, with the β positions occupied by hydrogens. Ligand 14c is similar to 14b, except that the β positions bear iodine atoms. The MOF synthesis was carried out using a one-pot method, followed by slow evaporation to obtain single crystals. These crystals of formula [Ag12(StBu)6(CF3COO)6(14)6]. This synthesized material is capable of capturing pollutant gases, such as sulphur mustard, and allows their photocatalytic decontamination.

Guo et al., in 2023, formed a MOF from zirconium clusters (Zr6O4(OH)4) incorporating BODIPY 15 [71]. This peculiar BODIPY is functionalized with three similar long arms at the meso and α positions, each featuring triazole groups formed after a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC, flagship reaction of Click Chemistry), resulting in a coordinating carboxylate group at the end of each arm. The β positions bear iodine atoms. TEM-EDX studies allowed for elemental mapping of the atoms present and their distribution within the structure, revealing good homogeneity. However, the sample appeared to have low crystallinity, as SEM observations showed particles in the form of small beads, and powder X-ray diffractograms indicated moderate crystallinity. The material displayed potential as an anticancer agent, as it has been demonstrated to selectively accumulate in 4T1 tumour cells while exhibiting good stability.

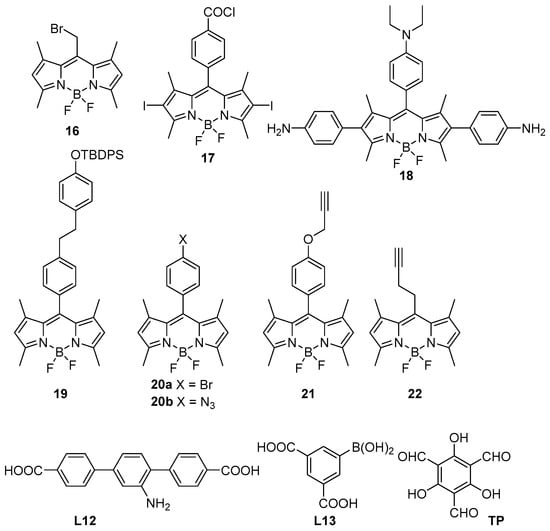

3. BODIPYs Attached to MOFs by Organic Reactions

In this section, a limited number of examples will be discussed. These are conceptually designed by appending BODIPY moieties to entities known to behave as linkers between metal nodes, as opposed to BODIPY-centred ligands (see Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4). Hence, the structures of the resulting BODIPY@MOF materials are expected to be very similar to those of the parent MOFs.

To obtain the target materials, only post-functionalization strategies were developed, which allow divergent functionalization from a single MOF precursor. However, they face challenges typical of heterogeneous reactions, and the MOF structure must be compatible with the synthetic conditions envisioned. The BODIPYs used for these strategies are summarized in Scheme 6, and the synthesis conditions and quantitative characterization of the BODIPY loading are summarized in Table 6. The synthetic conditions are typically milder (often RT) than methods requiring the integration of BODIPY-centred ligands (Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4), with the notable exception of the last entry in which harsher conditions are required due to the concomitant formation of MOF with a Click reaction. Due to the limited number of examples, articles in this section are presented chronologically rather than by application.

Scheme 6.

BODIPYs 16–22 used in the covalent functionalization of MOFs, as well as auxiliary ligands L12, L13, and TP, reactant.

Table 6.

Overview of synthetic conditions, quantification of BODIPY, and applications for MOFs covalently functionalized with BODIPYs.

In an early (2009) and seminal example, Lin and co-workers reported the postsynthetic functionalization of a MIL-101(Fe) nanosized MOF described by the formula Fe3(µ3-O)Cl(H2O)2(L)3 (where L = terephthalate or 2-aminoterephthalate) [72]. The incorporation of up to 17.5 mol-% of 2-aminoterephthalate did not result in changes detectable by PXRD. Then, reaction with brominated BODIPY 16 (about the same mass as the MOF) allowed the covalent grafting of the BODIPY on the structure. The 16 loading was quantified by digesting the MOF (Na4EDTA solution) and assaying the 16 released in solution by UV-Vis spectrophotometry. The authors stress that their 16@MOF material is nonemissive due to quenching by d-d transitions of FeIII. Their BODIPY-loaded nanoparticles of their MOF were found to be unstable in the common PBS buffer (half-life t1/2 = 2.5 h, for 8 mM buffer at 37 °C) by assaying the release of 16. The t1/2 could be raised to 16 h by coating the particles with silica. The silica-coated particles proved efficient in delivering the BODIPY dye to HT-29 cancerous cells. Their article also included the application of the same functionalization strategy for an anticancer drug.

In 2016, Li, Zhao, Wang, and co-workers described the post-modification of a ZrIV MOF with a diiodo-BODIPY 17. The zirconium MOF was UiO-68-NH2, which was obtained from aminotriphenyldicarboxylic acid (L12). Hence, a smooth reaction allowed the coupling of the acyl chloride of 17 to the amine group of L12 within a preformed MOF [73]. The as-synthesized UiO-68-NH2 was treated with 10% triethylamine in ethanol to deprotonate the amine groups. Then, the solvent mixture was reacted with 17. The loading of BODIPY was determined by X-ray fluorescence using the heavy elements Zr (from the MOF) and I (from 17), indicating that up to 11% of the organic ligands in UiO-68-NH2 were functionalized with 17. Then, the authors verified that the photocatalytic activity of 17 towards the dehydrogenative cross-coupling of N-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline with nitromethane under green LED irradiation was maintained when 17 was immobilized within the MOF. Other oxidative reactions were also successfully tested.

Chen, Wang, Xie et al. have reported in 2020 an original strategy to post-functionalize UiO-66-NH2 [74]. The preformed MOF was exposed to a diamine-functionalized BODIPY 18 along with 1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol (TP). Through the formation of imine bonds, the BODIPY dye was covalently immobilized in the MOF. PXRD showed that the crystallinity was maintained in the process. The solid material acquired the characteristic colour of the BODIPY dye. UV-Vis, IR, and NMR spectroscopies proved the immobilization of BODIPY in the MOF. TGA analyses showed that the added organic part consists of around 15 wt-%. The presence of the diethylamino moiety in 18 allowed the achievement of smart properties in the biological context (photodynamic therapy) for the final MOF. Indeed, the final MOF was active in type I photodynamic therapy, with an extra activity against HeLa cancerous cells versus normal L929 cells. This selectivity stems from the protonation of the diethylamino group. If the latter is protonated, the final MOF releases hydroxyl radicals. If not, there is a competitive PET process implying -NEt2.

Fan, Yan, Ke, and co-workers described in 2022 a MOF based on Eu3+ and the ligand BBDC (L13) doped with the BODIPY 19 [75]. According to these authors, the covalent immobilization strategy consisted of the formation of an adduct with bridging fluoride between the 19 and the boronic acid group of L13 within the MOF. The inclusion of up to 9.5 wt-% of 19 with respect to BBDC was performed in a one-pot approach in solvothermal conditions. The inclusion of 19 resulted in lower crystallinity (PXRD). The inclusion of growing amounts of 19 changed the morphology of the material from nanorods to nanosheets. From the fluorescence spectroscopy, elemental mapping showed a uniform distribution of elements (including Si, only present in 19), which supports the formation of an adduct, although the loading of 19 in the final material was not quantified. The material with an initial loading of 4.8 wt-% was investigated for applications. Eu3+ is inherently emissive (lmax = 616 nm), and for the final material, a band appeared in the emission spectrum at 420 nm for the adduct between 19 and the boronic acid group of BBDC. This allowed us to design ratiometric detection approaches for F− and H2O2 based on the reactivity of those analytes with boronic acid moieties.

Li and co-workers described in 2022 a peculiar MOF with a thiazolothiazole-based dicarboxylate linker, isoreticular to the terphenyl-based UiO-68 (ZrTc). The thiazole nitrogen could be alkylated post-synthetically. The resulting alkylated MOF had improved NLO properties, displaying fluorescence after efficient multi-photon excitation in the NIR-II region [78]. In 2025, they reported the propargylation of the thiazole in a preformed ZrTc MOF, followed reportedly by a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (reaction with a BODIPY carrying a para-azidophenyl substituent in the meso position) [76]. Examination of the analytical data reported for the azido-BODIPY casts a doubt on this result, as no IR band associated with N3 was observed in the BODIPY starting material 20a, whose precursor 20b displayed a para-bromophenyl group. In our opinion, it is likely that encapsulation of 20b was performed in the ZrTc MOF rather than click CuAAC of its azidated counterpart 20a. After loading the BODIPY, the MOF nanoparticles were coated with hyaluronic acid. On these final materials, named ZTBH, the authors performed extensive photophysical and biological experiments showing that efficient two-photon photosensitization was achieved under NIR laser irradiation. Moreover, fluorescence lifetime measurements were indicative of changes in cellular microenvironments during PDT.

Guo, Liu, Zhang et al. described in 2024 a new MOF following overall the UiO architecture but with a Co16 cluster containing both azide and formate ions [77]. These authors reported an impressive array of MOFs by varying the ligands bridging the Co16 clusters. Among those was the usual terephthalate. The Co16-MOF with terephthalate was coupled by azide–alkyne cycloaddition with BODIPYs 21 and 22. Hence, the BODIPY was directly attached to the Co16 clusters. Control experiments proved the covalent attachment, and the presence of significant amounts of copper contaminants (CuAAC catalyst) was ruled out by ICP. The BET surface area was also reduced from 194 m2g−1 to 155 m2g−1 upon covalent grafting. In the photocatalytic oxidative coupling of benzylamine, the authors then demonstrated that the clicked 21-Co16-MOF clearly outperformed the parent material. The clicked MOF achieved nearly quantitative yield, which was attributed to a synergistic behaviour between the metal cluster and the BODIPY. Notably, the BODIPY allowed the photogeneration of the superoxide ion, which was not possible with the pristine material.

4. Non-Coordinating BODIPYs

In this section, examples of hybrid BODIPY@MOF materials not relying on the coordination of the BODIPY on metal nodes will be reviewed. To this end, the BODIPYs used lack coordinating moieties, freeing several positions for other functionalities (Scheme 7). The main practical advantage of this strategy is the operational simplicity, as shown by the synthesis conditions outlined in Table 7. However, for this strategy, there is the obvious possibility of BODIPY guest leakage from the MOF host. Indeed, a simple tetramethylated BODIPY 23 was used as a probe to investigate the transport process in solvent-filled NU-1008 crystallites. NU-1008 has large 1D hexagonal channels [79]. The impact of post-synthetic modifications of the latter MOF on the transport properties was investigated [80]. This proof-of-concept study paves the way for a deeper understanding of mass transport phenomena in MOFs, the control of which is important for numerous applications, but also underlines the special considerations that must be made to avoid leakage of the BODIPY from the MOF when the hybrid is exposed to solvents. In this section, several examples of materials arising from non-covalent interactions between a BODIPY and an MOF scaffold will be discussed in detail.

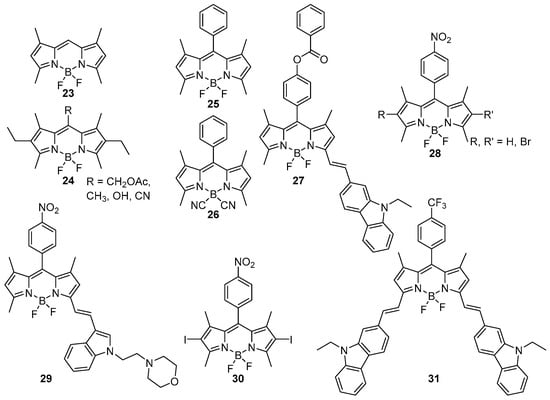

Scheme 7.

Non-coordinating BODIPYs 23–31.

Table 7.

Overview of synthetic conditions, quantification of BODIPY and applications for MOFs encapsulating non-coordinating BODIPYs.

Luminescent BODIPY@MOF materials not relying on coordination interaction were studied in 2018 by Friščić, Cosa, and co-workers with BODIPY dyes of the 24-type encapsulated in ZIF-8 [81]. The rationale of this study was the very good size matching between the pore diameter and the BODIPY dimensions in combination with smaller pore apertures, which could lead to a stable hybrid material. Most of the study was performed with a BODIPY bearing a methyleneacetoxy group in the meso position, with other substituents introduced to further exemplify the method. Synthetically, solvent-free mechanochemical (ion- and liquid-assisted grinding, ILAG [88]) or accelerated ageing (AA) [89] approaches were used in the presence of 0.05 to 5 wt-% of BODIPY. The encapsulation could be appreciated by the colour of the samples under visible light, along with a distinct luminescence upon UV irradiation. UV assays of solutions obtained by thoroughly washing the samples (MeOH, DCM) demonstrated a nearly total for and very good encapsulation for ILAG and AA approaches, respectively. PXRD and N2 sorption experiments yielded very similar results to pristine ZIF-8, as expected from low dye loading. Fluorescence quantum yields were compared to the solution measurement (67%) and ranged from 68% for the lowest loaded sample, while the quantum yields dropped to 7.8% for the highest loading. The lowest loading solid-state sample also displayed a luminescence lifetime quite similar to the value reported for the solution (6.76 vs. 7.5 ns), highlighting a monomeric emission in the diluted solid state. This, along with the observation of bathochromic shifts in the emission spectra and shortened emission lifetimes, induced the authors to postulate that weakly emissive H-aggregates could be formed with increased dye loading, and that these could act as trap sites in energy transfer processes with molecules in neighbouring pores. Very interestingly, the authors demonstrated that the incarceration in ZIF-8 improved dramatically the photostability of the BODIPY guest.

In a very recent article (published only a few days after the submission of this review), Janick et al. studied the encapsulation of BODIPYs 25 (37% PLQY, t = 5.7 ns in CHCl3) and 26 (89% PLQY, t = 4.8 ns in CHCl3) into four different MOFs, UiO-66, MOF-808, DUT-67 and MIP-206 [82]. At first, they focused on the case of UiO-66, but with 25, they did not obtain any positive result, likely due to the acidity of the defective UiO-66 structure. On the other hand, 26 is more stable towards acidic conditions and was successfully used in two strategies. The first one is a post-functionalization approach. For the post-synthetic method, they incorporated 0.44 wt-% of 26, associated with a sharp decrease in the BET surface area. The second integration approach is the one-pot method; for this, they introduced different quantities in the synthesis between 3 and 15 mmol/L. This resulted in up to 7.2 wt-% BODIPY in their MOF. The study of the BET surface area shows the same phenomenon as the post-synthetic approach. In terms of luminescence quantum yields, the best sample of the one-pot approach is 26@UiO-661.1wt% with 32% (t = 5.1 ns), compared with the post-synthetic approach sample, with 26@UiO-660.44wt% and a quantum yield of 29% (t = 5.1 ns). Subsequently, they performed the same studies with MOF-808, DUT-67, and MIP-206. For the MOF-808, they obtained the best sample with a post-synthetic approach, incorporated 0.57 wt-% with a quantum yield of 48% (t = 6.5 ns). For DUT-67, they obtained the best sample with the post-synthetic method, also, with 0.51 wt-% incorporated and a quantum yield of 77% (t = 6.8 ns). Finally, for MIP-206, they only performed the post-synthetic approach and obtained a sample with 0.3 wt-% and a quantum yield of 47% (t = 7.9 ns). The results highlight quantum yields and luminescence lifetimes similar to or higher than those in the solid state as compared to solution, which is compatible with the MOF, allowing a “solid solution” environment for efficient BODIPY luminescence.

Sensor applications were reported in several publications. Shen, Zhang, Huang, and co-workers reported in 2021 the use of 27@ZIF-8 to detect carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) [83]; 27 was used again in a very small amount compared to 2-methylimidazole (less than 0.3 mol-%). The authors used UV-Vis spectroscopy to assay the integration of the BODIPY 27 in their MOF (assay of a digested sample in DMSO/citrate buffer) and demonstrated 76% integration. They used their probe to detect CES1 by a decrease in the fluorescence intensity (initial quantum yield: 65% as deduced from indirect measurements) and reported a limit of detection (LOD) of 1.15 ng/L. This allowed the visual monitoring of CES1 activity in living cells. Moreover, the pesticide chlorpyrifos inhibits CES1, allowing an indirect assay of this pesticide. Indeed, a linear curve was obtained by comparing the luminescence intensity of the samples in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of the pesticide after a fixed incubation time.

Xue, Chen et al. reported in 2023 [84], the use of a copper-based terpyridine MOF, initially published by Konar and co-workers [90], to host BODIPY molecules of the 28-type. The MOF was prepared in the absence of 28 molecules, which were subsequently loaded in solution. Finally, PEG-600 was added as a stabilizer. In the same work, non-MOF nanoparticles were also used (porous silica and polystyrene-co-acrylic acid nanoparticles). The different materials were considered in an applied study towards the colorimetric detection of volatile organic compounds in the solid state. While the application was thoroughly studied, the characterization of the MOFs themselves was rather limited. In particular, the authors did not quantitatively investigate the loading of non-coordinating BODIPYs of type 28 in their MOFs.

In another article based on a similar strategy, He, Shen et al. reported in 2022 ZIF-8 loaded with BODIPY 29, to design a red-emitting nanocomposite for the detection of nitroreductase (NTR) in living cells [85]. NTR is correlated with hypoxia, which is typical of solid tumours. Their synthetic strategy relied on the addition of a small amount (29 as an additive in the synthesis of ZIF-8, followed by ethanol washings in the synthesis work-up. Direct evidence of the encapsulation of 29 was provided by XPS and microscopy element mapping; however, the BODIPY contents in the final material were not quantified. The authors demonstrated the use of 29@ZIF-8 as a sensor for NTR, with a fluorescence enhancement upon exposure of the material to the target enzyme, both with isolated enzymes and full cells.

In addition to these works, a report by Zhang et al. mentions MOF and BODIPYs in more sophisticated assembly with a polymer as a third party. In this work, nanoprobes relying on FRET between a luminescent MOF and a C, O-BODIPY appended to a polymeric chain were designed for pH and temperature sensing based on modulation of donor(MOF)-acceptor(BODIPY) distance [91].

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) was reported in 2018 by Li, Dong, and co-workers using diiodo-BODIPY 30 [86]. The presence of iodine atoms increases the quantum yield for the generation of 1O2, with applications in PDT. The authors chose ZIF-90 as host and underline the compatibility of the dimensions of molecule 30 (10.8 × 10.4 Å) with the pore diameter of the MOF (11.2 Å). Based on ICP measurements (no experimental details were provided), they claimed a loading of 25.4 wt-%, which is near the saturation of ZIF-90s pores. PXRD measurements showed that the ZIF structure was not disrupted, while the BODIPY guest was not detected by 13C solid-state NMR and IR. Such a high weight percentage seems inconsistent with the IR and NMR results. Despite this, the 30@ZIF-90 composite exhibited impressive biological properties, benefiting from a synergy between the MOF host and the BODIPY guest. Inclusion in the MOF greatly improved the photostability of BODIPY 30. Moreover, ZIF-90 is stable at physiological pH (blood circulation, pH = 7.4) but less so at slightly acidic pH values (pH of certain cellular compartments), due to imidazolate protonation. Biologically, the resulting positive surface charge of the 30@ZIF-90 nanoparticles enhances membrane crossing and selective uptake in cancer cells (with microenvironments at pH = 6.5) and also induces mitochondrial targeting. Finally, the authors demonstrated the potential of their material in PDT (high-light-induced vs. low dark cytotoxicity). Overall, their strategy was complementary to purely molecular PDT approaches, with fewer challenges in organic synthesis.

In 2022, Shen, Luan et al., reported the encapsulation in ZIF-8 of an extended conjugated BODIPY 31, with the objective of designing efficient materials for PDT [87]. 31 was chosen among a set of BODIPY photosensitizers and proved to be more efficient as compared to compounds bearing only one carbazole moiety. For 31@ZIF-8, the synthetic approach used again a very small amount of 31 as an additive in the synthesis of ZIF-8. The authors characterized the hybrids by several techniques, including microscopy, DLS, XPS and EDX element mapping, showing the formation of well-defined 250 nm particles with uniform distribution of B and F elements, hinting at a good encapsulation of 31. Interestingly, a MOF/BODIPY synergy was envisioned by the authors, with ZIF-8 able to promote the dismutation of H2O2 and thus increase the concentration of O2. This is of importance considering that tumours are typically hypoxic, thus reducing the efficiency of PDT based on the generation of singlet dioxygen. This effect was proven in vitro, and biological tests performed on living mice affected by tumours suggested a superior efficiency of the 31@ZIF-8 hybrid as compared to molecular 31.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

In this review article, we sought to summarize a recent research area building on the impressive properties of BODIPYs in their molecular form in solution, as well as the unique characteristics of MOF among the palette of hybrid materials. The examples discussed within this review provide a variety of ideas useful for future works, both for the synthetic conditions, materials characterization and applications. Current limitations and shortcomings of the literature differ following the integration strategy. On the one hand, for stoichiometrically defined materials with BODIPY-centred ligands, the main challenge is to ensure the compatibility of the synthetic conditions of MOF (often high temperature, and in the presence of strong Brønsted and Lewis Acids) with the BODIPY. On the other hand, for all other strategies, the crucial aspects of quantification of the BODIPY loading and verification of the MOF integrity arise. In the future, we anticipate discoveries in all of the research axes outlined in the paper, BODIPY-derived ligands as linkers, covalent grafting, and encapsulation. We believe that coordination chemistry of covalent-grafting procedures, though more challenging, offers greater opportunities in terms of fine-tuning of the hybrid materials as compared to encapsulation approaches, which might be, on the other hand, simpler in practice. The use of advanced and quantitative characterization techniques seems of paramount importance, especially when BODIPY is used as a dopant and not a stoichiometric linker of the MOF. The state of the art in this area is currently under definition, as the characterization efforts of the BODIPY-containing materials are quite heterogeneous in the reviewed articles.

This research area is quite new but promises further developments. The examples known to date demonstrate that the integration of BODIPYs within MOFs presents a fertile ground for discovery, innovation, and applications. The synergistic combination of BODIPYs’ photophysical and/or photochemical properties with the structural versatility and porosity of MOFs opens up avenues for applications in fields such as luminescent or light-harvesting materials, photodynamic therapy, sensing, and photocatalysis, which were only partly explored in recent years. The potential for new breakthroughs in this area is quite vast, and continued interdisciplinary collaboration will be key to unlocking new capabilities of BODIPY@MOF systems.

Author Contributions

L.B., C.M., F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M., F.C.; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

L.B. thanks the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research for her doctoral fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Accelerated Ageing |

| ACQ | Aggregation-Caused Quenching |

| AIE | Aggregation-Induced Emission |

| BODIPY | Boron-Dipyrromethene |

| CCDC | Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre |

| CES1 | Carboxylesterase 1 |

| CuAAC | Copper-catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| ECL | Electrochemiluminescence |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| FRET | Förster Resonance Energy Transfer |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| ILAG | Ion-and Liquid-Assisted Grinding |

| IR | Infrared Spectroscopy |

| IRET | Intrareticular Energy Transfer |

| ITO | Indium Tin Oxide |

| LED | Light-Emitting Diode |

| MIL | Matériaux de l’Institut Lavoisier |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Frameworks |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| NLO | Nonlinear Optics |

| NTR | Nitroreductase |

| NU | Northwestern University |

| OER | Oxygen Evolution Reactions |

| PCN | Porous Coordination Networks |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PET | Photoinduced Electron Transfer |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray Diffraction |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SALE | Solvent-Assisted Ligand Exchange |

| SALI | Solvent-Assisted Ligand Incorporation |

| SCXRD | Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SPDT | Sonophotodynamic Therapy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| TDC | 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylate |

| UiO | University of Oslo |

| UV-vis | Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| ZIF | Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework |

References

- Baudron, S.A. Luminescent Metal-Organic Frameworks Based on Dipyrromethene Metal Complexes and BODIPYs. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 4671–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Sun, Y.; Das, A.; Stang, P.J.; Yeon Lee, C. BODIPY Based Metal-Organic Macrocycles and Frameworks: Recent Therapeutic Developments. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 452, 214308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Cheng, C.; Chu, D.; Tang, X.; Li, H.; Cui, Y. Synthesis, Structure and Property of Boron-Based Metal–Organic Materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 435, 213783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowada, T.; Maeda, H.; Kikuchi, K. BODIPY-Based Probes for the Fluorescence Imaging of Biomolecules in Living Cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4953–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; MacK, J.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Z. Structural Modification Strategies for the Rational Design of Red/NIR Region BODIPYs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 4778–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loudet, A.; Burgess, K. BODIPY Dyes and Their Derivatives: Syntheses and Spectroscopic Properties. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4891–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Bouffard, J.; Kim, Y. Aggregation-Induced Emission Enhancement of a Meso-Trifluoromethyl BODIPY via J-Aggregation. Chem. Sci. 2013, 5, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bouffard, J.; Kim, Y. A Reflection on ‘Aggregation-Induced Emission Enhancement of a Meso-Trifluoromethyl BODIPY via J-Aggregation’: From Fundamental Discovery to Versatile Sensing Platforms. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 21147–21151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkaew, A.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, H.B.; Kiew, L.V.; Chung, L.Y.; Burgess, K. BODIPY Dyes in Photodynamic Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 42, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurubasavaraj, P.M.; Sajjan, V.P.; Muñoz-Flores, B.M.; Jiménez Pérez, V.M.; Hosmane, N.S. Recent Advances in BODIPY Compounds: Synthetic Methods, Optical and Nonlinear Optical Properties, and Their Medical Applications. Molecules 2022, 2022, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, P.; Singh, N.; Majumdar, P.; Prakash Singh, S. Evolution of BODIPY/Aza-BODIPY Dyes for Organic Photoredox/Energy Transfer Catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 470, 214698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziessel, R.; Ulrich, G.; Harriman, A. The Chemistry of Bodipy: A New El Dorado for Fluorescence Tools. New J. Chem. 2007, 31, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, K.; Yang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, F. The Triplet Excited State of Bodipy: Formation, Modulation and Application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8904–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, H.; Davies, E.S.; Lewis, W.; Kays, D.L.; Champness, N.R. Structural Characterization and Optical Properties of Two Copper(I)-Iodide BODIPY Coordination Polymers. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 4551–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliken, R.S. Lewis Acids and Bases and Molecular Complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 1951, 19, 514–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.C.J.; Kitagawa, S. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5415–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, W.; Volosskiy, B.; Demir, S.; Gándara, F.; McGrier, P.L.; Furukawa, H.; Cascio, D.; Stoddart, J.F.; Yaghi, O.M. Synthesis, Structure, and Metalation of Two New Highly Porous Zirconium Metal-Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 6443–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, V.F.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Review on Metal-Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Eddaoudi, M.; O’Keefe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Design and Synthesis of an Exceptionally Stable and Highly Porous Metal-Organic Framework. Nature 1999, 402, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavka, J.H.; Jakobsen, S.; Olsbye, U.; Guillou, N.; Lamberti, C.; Bordiga, S.; Lillerud, K.P. A New Zirconium Inorganic Building Brick Forming Metal Organic Frameworks with Exceptional Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13850–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Ni, Z.; Côté, A.P.; Choi, J.Y.; Huang, R.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Chae, H.K.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional Chemical and Thermal Stability of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10186–10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddaoudi, M.; Li, H.; Reineke, T.; Fehr, M.; Kelley, D.; Groy, T.L.; Yaghi, O.M. Design and Synthesis of Metal-Carboxylate Frameworks with Permanent Microporosity. Top. Catal. 1999, 9, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From Visualization to Analysis, Design and Prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkar, P.; Kukkar, D. Recent Breakthroughs in the Solvothermal Assisted Synthesis of Luminescent Metal-Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 178, 114631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.W.; Nguyen, V.H.; Zhou, S.R.; Hsu, S.Y.; Tan, J.X.; Wu, K.C.W. Metal-Organic Frameworks: Preparation and Applications in Highly Efficient Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranchemontagne, D.J.; Hunt, J.R.; Yaghi, O.M. Room Temperature Synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks: MOF-5, MOF-74, MOF-177, MOF-199, and IRMOF-0. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 8553–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Simms, C.; Dovgaliuk, I.; Patriarche, G.; Tissot, A.; Parac-Vogt, T.N.; Serre, C. Monodispersed MOF-808 Nanocrystals Synthesized via a Scalable Room-Temperature Approach for Efficient Heterogeneous Peptide Bond Hydrolysis. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 7057–7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Eddaoudi, M.; Groy, T.L.; Yaghi, O.M. Establishing Microporosity in Open Metal-Organic: Gas Sorption Isotherms for Zn(BDC) (BDC = 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylate). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8571–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chai, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, B. Metal-Organic Framework Films and Their Potential Applications in Environmental Pollution Control. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbaghi, A.; Pourbabaki, R.; Zarandi, A.F.; Sadeghian, M.; Damiri, Z. Sampling of Air Pollutants by MOFs, COFs, and POFs in Needle Traps: A Systematic Review. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. 2025, 12, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Yu, L.; Kang, P.; Chu, Z.; Li, Y. Modifications and Applications of Metal-Organic-Framework-Based Materials for Photocatalysis. Molecules 2024, 29, 5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yang, H.; Xu, W.; Sun, Y.; Pang, H. Research Progress of MOF-Based Materials in Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 and N2. Chem. Catalysis 2024, 4, 100929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M. Recent Progress in Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) Based Luminescent Chemodosimeters. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, T. Recent Progress in MOF-Based Flexible Sensors: A Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 44, e01429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenkova, D.; Dimitrova, Y.; Tsvetkov, M.; Morgenstern, B.; Milanova, M.; Todorovsky, D.; Zaharieva, J. Investigation of the Sensing Properties of Lanthanoid Metal–Organic Frameworks (Ln-MOFs) with Terephthalic Acid. Molecules 2024, 29, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]