Synthesis and Anti-Tumor Evaluation of Carboranyl BMS-202 Analogues—A Case of Carborane Not as Phenyl Ring Mimetic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

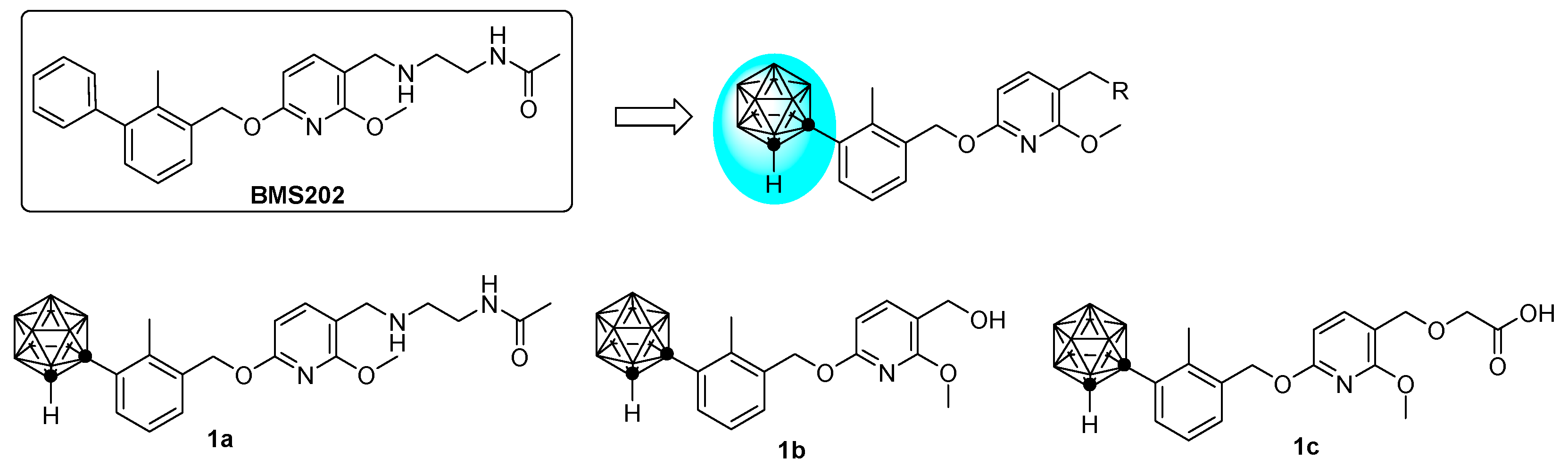

2.1. Molecular Design

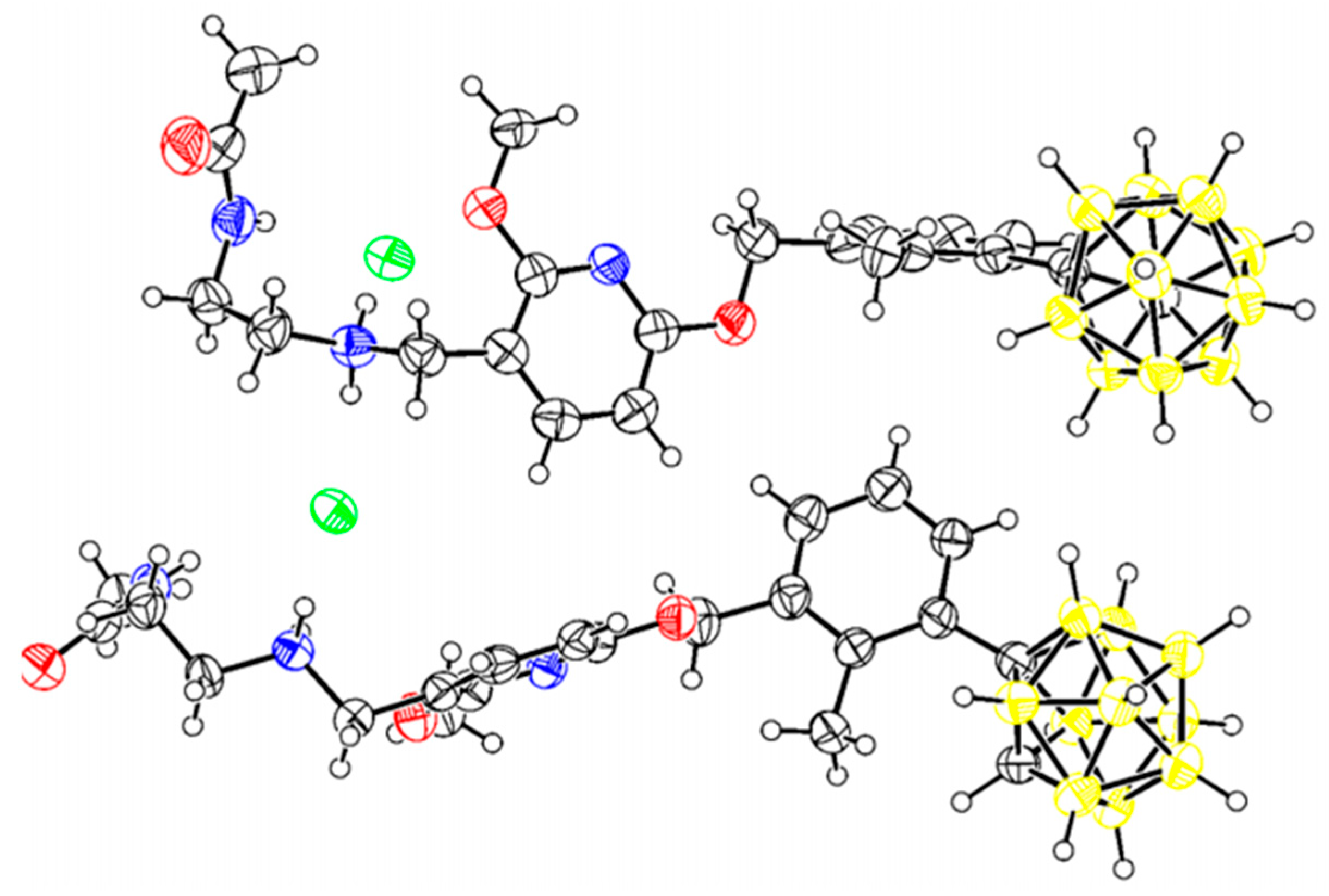

2.2. Chemistry

2.3. Biological Evaluation

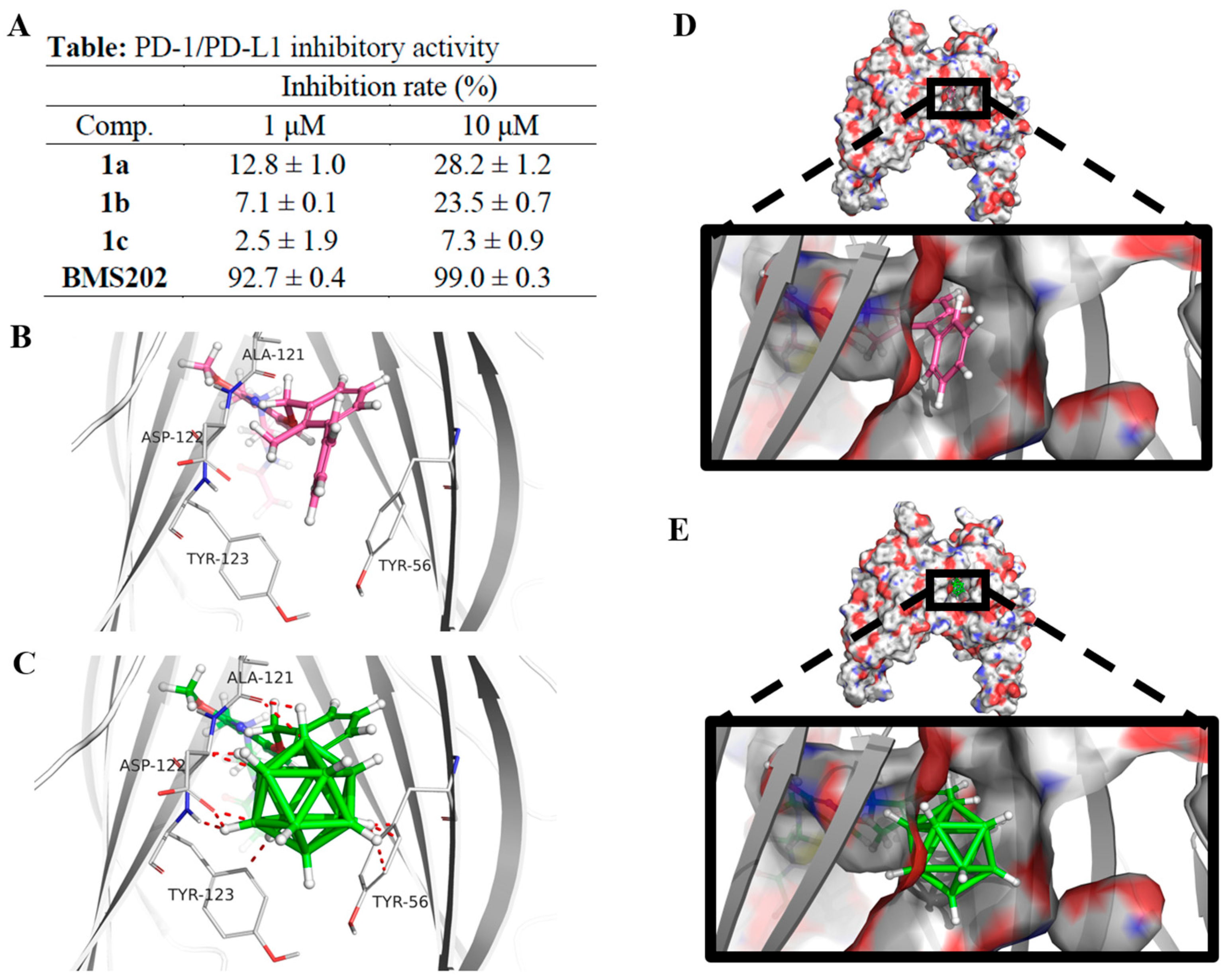

2.3.1. PD-L1 Inhibition Studies

2.3.2. Anti-Proliferation Study

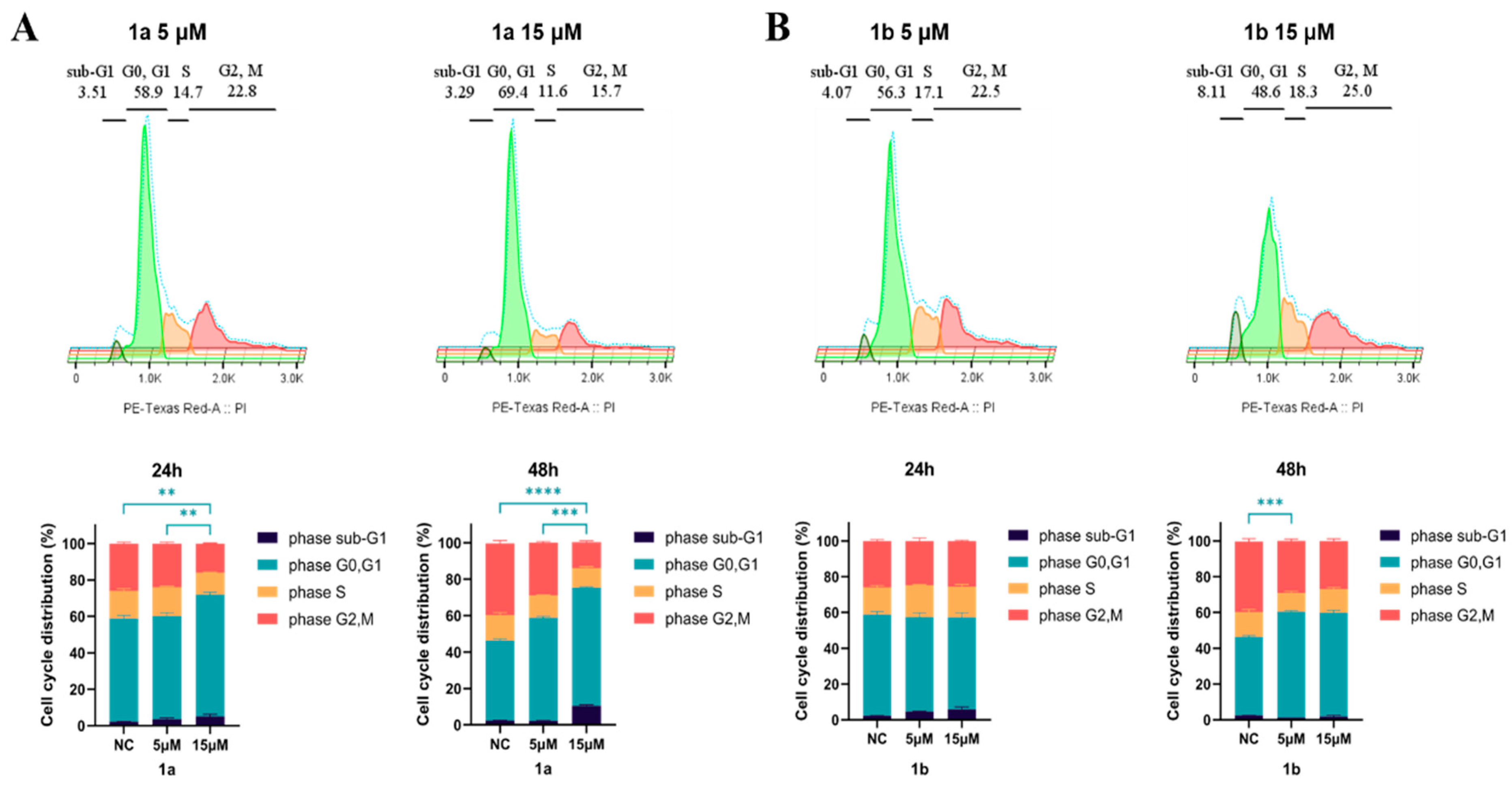

2.3.3. Compounds 1a and 1b Induce G1 Cell Cycle Phase Arrest

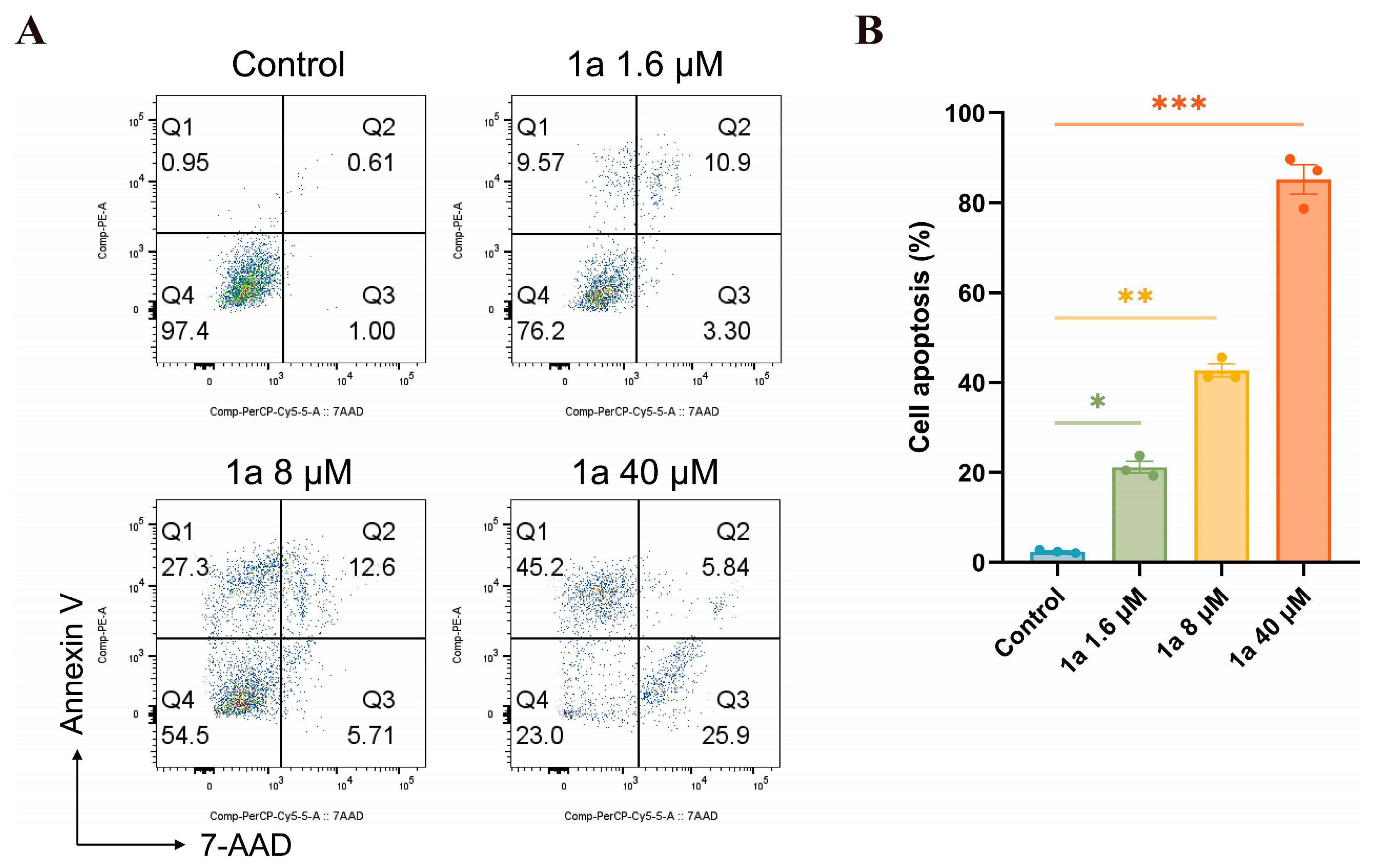

2.3.4. Apoptosis Study

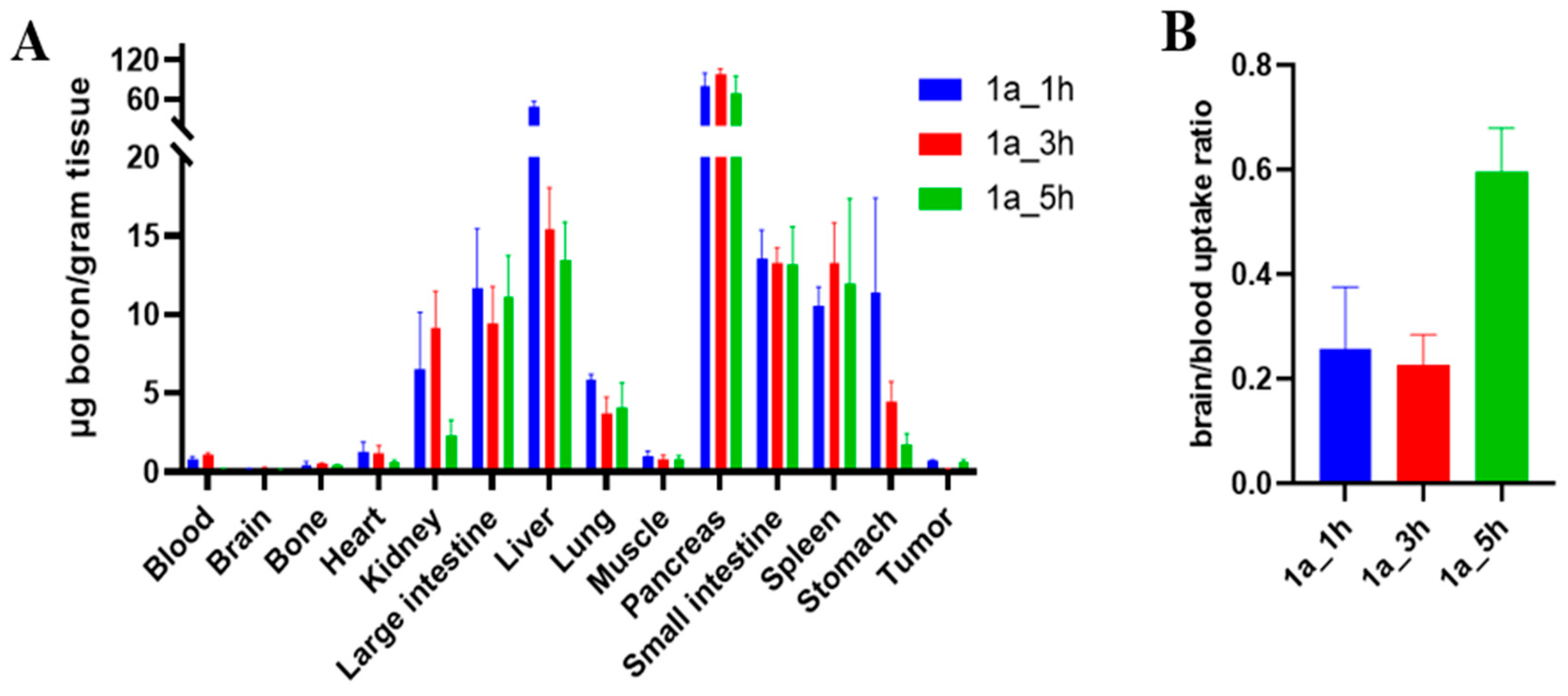

2.3.5. Biodistribution Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Biological Evaluation

3.2.1. PD1/PD-L1 Blockade Bioassay

3.2.2. Docking Studies

3.2.3. Cell Culture

3.2.4. Anti-Proliferation Assay

3.2.5. Cell Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

3.2.6. Apoptosis Analysis Assay

3.2.7. Xenograft Models

3.2.8. Biodistribution Study of Compound 1a Using ICP-MS

3.2.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valliant, J.F.; Guenther, K.J.; King, A.S.; Morel, P.; Schaffer, P.; Sogbein, O.O.; Stephenson, K.A. The medicinal chemistry of carboranes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 232, 173–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Xie, Z. Functionalization of o-carboranes via carboryne intermediates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 3164–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, R.; Lin, J.; Gui, L.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Xia, W.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, S.; et al. Novel promising boron agents for boron neutron capture therapy: Current status and outlook on the future. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 511, 215795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, D.S.; Saifi, O.; Mackeyev, Y.; Malouff, T.; Krishnan, S. Next-generation boron drugs and rational translational studies driving the revival of BNCT. Cells 2023, 12, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvinen, J.; Pulkkinen, H.; Rautio, J.; Timonen, J.M. Amino acid-based boron carriers in boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT). Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Josephson, L.; Liang, S.H.; Zhang, M.R. Boron agents for neutron capture therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 405, 213139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, M.; Alamón, C.; Nievas, S.; Perona, M.; Dagrosa, M.A.; Teixidor, F.; Cabral, P.; Viñas, C.; Cerecetto, H. Bimodal therapeutic agents against glioblastoma, one of the most lethal forms of cancer. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 14335–14340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamón, C.; Dávila, B.; García, M.F.; Nievas, S.; Dagrosa, M.A.; Thorp, S.; Kovacs, M.; Trias, E.; Faccio, R.; Gabay, M.; et al. A potential boron neutron capture therapy agent selectively suppresses high-grade glioma: In vitro and in vivo exploration. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 2702–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, P.; Gozzi, M.; Kuhnert, R.; Sárosi, M.B.; Hey-Hawkins, E. New keys for old locks: Carborane-containing drugs as platforms for mechanism-based therapies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3497–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauchère, J.L.; Do, K.Q.; Jow, P.Y.; Hansch, C. Unusually strong lipophilicity of ‘fat’ or ‘super’ amino-acids, including a new reference value for glycine. Experientia 1980, 36, 1203–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Lepšík, M.; Horinek, D.; Havlas, Z.; Hobza, P. Interaction of carboranes with biomolecules: Formation of dihydrogen bonds. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunato, A.J.; Wang, J.; Woollard, J.E.; Anisuzzaman, A.K.M.; Ji, W.; Rong, F.; Ikeda, S.; Soloway, A.H.; Eriksson, S.; Ives, D.H.; et al. Synthesis of 5-(carboranylalkylmercapto)-2′-deoxyuridines and 3-(carboranylalkyl)thymidines and their evaluation as substrates for human thymidine kinases 1 and 2. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 3378–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfavi, A.; Kavianpour, P.; Rendina, L.M. Carboranes in drug discovery, chemical biology and molecular imaging. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, M.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Carbaboranes as pharmacophores: Properties, synthesis, and application strategies. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7035–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamón, C.; Dávila, B.; García, M.F.; Sánchez, C.; Kovacs, M.; Trias, E.; Barbeito, L.; Gabay, M.; Zeineh, N.; Gavish, M.; et al. Sunitinib-containing carborane pharmacophore with the ability to inhibit tyrosine kinases receptors FLT3, KIT and PDGFR-β, exhibits powerful in Vivo anti-glioblastoma activity. Cancers 2020, 12, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, M.; Alamón, C.; García, M.F.; Kovacs, M.; Trias, E.; Nievas, S.; Pozzi, E.; Curotto, P.; Thorp, S.; Dagrosa, M.A.; et al. Closo-Carboranyl- and Metallacarboranyl [1,2,3]triazolyl-decorated lapatinib-scaffold for cancer therapy combining tyrosine kinase inhibition and boron neutron capture therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, M.; García, M.F.; Alamón, C.; Cabrera, M.; Cabral, P.; Merlino, A.; Teixidor, F.; Cerecetto, H.; Viñas, C. Discovery of potent EGFR inhibitors through the incorporation of a 3D-aromatic-boron-rich-cluster into the 4-anilinoquinazoline scaffold: Potential drugs for glioma treatment. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3122–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbaiah, M.A.M.; Meanwell, N.A. Bioisosteres of the phenyl ring: Recent strategic applications in lead optimization and drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 14046–14128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K. Recent advances in bridged structures as 3D bioisosteres of ortho-phenyl rings in medicinal chemistry applications. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 6417–6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Altmann, E.; Racine, S.; Lewis, R. Ring replacement recommender: Ring modifications for improving biological activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Ohta, K.; Yoshimi, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ohta, S.; Endo, Y. m-Carborane bisphenol structure as a pharmacophore for selective estrogen receptor modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3943–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Masuno, H.; Taoda, Y.; Kano, A.; Wongmayura, A.; Nakabayashi, M.; Ito, N.; Shimizu, M.; Kawachi, E.; Hirano, T.; et al. Boron cluster-based development of potent nonsecosteroidal vitamin D receptor ligands: Direct observation of hydrophobic interaction between protein surface and carborane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20933–20941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poater, J.; Viñas, C.; Bennour, I.; Escayola, S.; Solà, M.; Teixidor, F. Too persistent to give up: Aromaticity in boron clusters survives radical structural changes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9396–9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepan, A.F.; Subramanyam, C.; Efremov, I.V.; Dutra, J.K.; O’Sullivan, T.J.; DiRico, K.J.; McDonald, W.S.; Won, A.; Dorff, P.H.; Nolan, C.E.; et al. Application of the bicyclo [1.1.1]pentane motif as a nonclassical phenyl ring bioisostere in the design of a potent and orally active γ-secretase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3414–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Du, F.; Tang, L.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Shen, J.; Wen, Q.; Cho, C.H.; et al. Carboranes as unique pharmacophores in antitumor medicinal chemistry. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2022, 24, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selg, C.; Neumann, W.; Lönnecke, P.; Hey-Hawkins, E.; Zeitler, K. Carboranes as aryl mimetics in catalysis: A highly active zwitterionic NHC-precatalyst. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 7932–7937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Bensdorf, K.; Gust, R.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Asborin: The carbaborane analogue of aspirin. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Kaluđerović, G.N.; Kommera, H.; Paschke, R.; Will, J.; Sheldrick, W.S.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Carbaboranes as pharmacophores: Similarities and differences between aspirin and asborin. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saretz, S.; Basset, G.; Useini, L.; Laube, M.; Pietzsch, J.; Drača, D.; Maksimović-Ivanić, D.; Trambauer, J.; Steiner, H.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Modulation of γ-secretase activity by a carborane-based flurbiprofen analogue. Molecules 2021, 26, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, W.; Xu, S.; Sárosi, M.B.; Scholz, M.S.; Crews, B.C.; Ghebreselasie, K.; Banerjee, S.; Marnett, L.J.; Hey-Hawkins, E. nido-Dicarbaborate induces potent and selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. ChemMedChem 2015, 11, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WO 2015/034820 A1; Compounds Useful as Immunomodulators. World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Zak, K.M.; Grudnik, P.; Magiera, K.; Dömling, A.; Dubin, G.; Holak, T.A. Structural biology of the immune checkpoint receptor PD-1 and its ligands PD-L1/PD-L2. Structure 2017, 25, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, K.M.; Grudnik, P.; Guzik, K.; Zieba, B.J.; Musielak, B.; Dömling, A.; Dubin, G.; Holak, T.A. Structural basis for small molecule targeting of the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Oncotarget 2016, 7, 30323–30335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Thi, E.P.; Carpio, V.H.; Bi, Y.; Cole, A.G.; Dorsey, B.D.; Fan, K.; Harasym, T.; Iott, C.L.; Kadhim, S.; et al. Checkpoint inhibition through small molecule-induced internalization of programmed death-ligand 1. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yin, M.; Cheng, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Yuan, K.; Min, W.; Dong, J.; et al. Novel small-molecule PD-L1 inhibitor induces PD-L1 internalization and optimizes the immune microenvironment. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 66, 2064–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, K.; Zak, K.M.; Grudnik, P.; Magiera, K.; Musielak, B.; Törner, R.; Skalniak, L.; Dömling, A.; Dubin, G.; Holak, T.A. Small-molecule inhibitors of the programmed cell death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) interaction via transiently induced protein states and dimerization of PD-L1. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5857–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, B.; Magiera-Mularz, K.; Skalniak, L.; Musielak, B.; Kholodovych, V.; Holak, T.A.; Hu, L. Design, synthesis, evaluation, and structural studies of C2-symmetric small molecule inhibitors of programmed cell death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 protein–protein interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7250–7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Cai, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Sun, H.; Guo, B.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Jiang, S. Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis that promote PD-L1 internalization and degradation. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 3879–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Yuan, C.; Hao, G.; Sun, N.; Li, H.; et al. Discovery and biological evaluation of carborane-containing derivatives as TEAD auto palmitoylation inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2025, 121, 130155–130163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.; Yuan, C.; Sun, N.; Hao, G.; Ma, C.; Lin, Y.; et al. Synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation of novel carborane-containing isoflavonoid analogues. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 18720–18732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Blaha, C.; Santos, R.; Huynh, T.; Hayes, T.R.; Beckford-Vera, D.R.; Blecha, J.E.; Hong, A.S.; Fogarty, M.; Hope, T.A.; et al. Synthesis and initial biological evaluation of boron-containing prostate-specific membrane antigen ligands for treatment of prostate cancer using boron neutron capture therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3831–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppino, A.; Genady, A.R.; El-Zaria, M.E.; Reeve, J.; Mostofian, F.; Kent, J.; Valliant, J.F. High yielding preparation of dicarba-closo-dodecaboranes using a silver(I) mediated dehydrogenative alkyne-insertion reaction. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 8743–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonnemann, C.J.; Engelage, E.; Ward, J.S.; Rissanen, K.; Keller, S.; Huber, S.M. Ortho-carborane-derived halogen bonding organocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202424072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zaria, M.E.; Keskar, K.; Genady, A.R.; Ioppolo, J.A.; McNulty, J.; Valliant, J.F. High yielding synthesis of carboranes under mild reaction conditions using a homogeneous silver(I) catalyst: Direct evidence of a bimetallic intermediate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5156–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Qin, X.; Xu, Z.; Song, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, Y.; Ruan, H.; Chen, J. Comparison of cytotoxicity evaluation of anticancer drugs between real-time cell analysis and CCK-8 method. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12036–12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ok, K.; Jung, Y.W.; Jee, J.; Byun, Y. Facile docking and scoring studies of carborane ligands with estrogen receptor. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2013, 34, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donarska, B.; Cytarska, J.; Kołodziej-Sobczak, D.; Studzinska, R.; Kupczyk, D.; Baranowska-Łaczkowska, A.; Jaroch, K.; Szeliska, P.; Bojko, B.; Rózycka, D.; et al. Synthesis of carborane–thiazole conjugates as tyrosinase and 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitors: Antiproliferative activity and molecular docking studies. Molecules 2024, 29, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IC50 (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Ramos | Raji | DU-145 | HepG2 | A549 | MDA-MB-468 |

| 1a | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 1.2 | 13.3 ± 1.2 | 67.2 ± 1.2 | 70.5 ± 1.0 |

| 1b | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 10.4 ± 1.4 | 26.1 ± 1.1 | 99.4 ± 1.2 | 38.5 ± 1.1 |

| 1c | 57.6 ± 1.1 | 169.3 ± 1.2 | 80.4 ± 1.3 | 110.9 ± 1.2 | 149.5 ± 1.0 | 52.9 ± 1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Ma, C.; Lin, Y.; Wang, L.; Hao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Synthesis and Anti-Tumor Evaluation of Carboranyl BMS-202 Analogues—A Case of Carborane Not as Phenyl Ring Mimetic. Molecules 2025, 30, 4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244789

Yuan C, Li C, Ma C, Lin Y, Wang L, Hao G, Zhang Y, Li H, Li Y, Zhao Y, et al. Synthesis and Anti-Tumor Evaluation of Carboranyl BMS-202 Analogues—A Case of Carborane Not as Phenyl Ring Mimetic. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244789

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Changxian, Chaofan Li, Chenyang Ma, Yuzhe Lin, Linyuan Wang, Guanxiang Hao, Yirong Zhang, Hongjing Li, Yuan Li, Yu Zhao, and et al. 2025. "Synthesis and Anti-Tumor Evaluation of Carboranyl BMS-202 Analogues—A Case of Carborane Not as Phenyl Ring Mimetic" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244789

APA StyleYuan, C., Li, C., Ma, C., Lin, Y., Wang, L., Hao, G., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Sun, N., Chen, T., Zhang, Z., Cheng, D., & Wang, S. (2025). Synthesis and Anti-Tumor Evaluation of Carboranyl BMS-202 Analogues—A Case of Carborane Not as Phenyl Ring Mimetic. Molecules, 30(24), 4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244789