Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., M.A.Z. and A.K.; methodology, A.A., M.A.Z. and A.K.; software, M.A.Z., A.K., M.A.S., A.M.G. and O.A.M.; validation, A.A., M.A.Z. and A.K.; formal analysis, A.A., M.A.Z. and A.K.; investigation, M.A.Z., A.K., M.A.S., A.M.G. and O.A.M.; resources, A.A.; data curation, A.A., M.A.Z. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.Z. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A.Z., M.A.S., A.K., A.M.G. and O.A.M.; visualization, M.A.Z., M.A.S., A.K., A.M.G. and O.A.M.; supervision, A.A. and A.K.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Validation of the Leucine Binding Mode through Molecular Docking. (A) 3D visualization comparing the computationally docked pose of leucine (top) with its experimentally determined crystallographic pose (bottom). Green ribbons denote the SESN2 protein backbone, and grey sticks represent carbon atoms of key interacting residues. Yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds, with adjacent numbers specifying the interaction distances in Angstroms (Å). (B) Corresponding 2D ligand interaction diagrams for the docked (top) and experimental (bottom) poses. Residue spheres are colored by chemical property: green (hydrophobic), blue (polar), purple (basic), and orange (acidic). Purple arrows indicate hydrogen bond directionality (donor to acceptor). (C) Structural alignment of the experimental (red) and docked (green) leucine poses. The low root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.68 Å confirms the high accuracy of the docking protocol, while the docking score of −6.15 kcal/mol indicates a favorable theoretical binding affinity.

Figure 1.

Validation of the Leucine Binding Mode through Molecular Docking. (A) 3D visualization comparing the computationally docked pose of leucine (top) with its experimentally determined crystallographic pose (bottom). Green ribbons denote the SESN2 protein backbone, and grey sticks represent carbon atoms of key interacting residues. Yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds, with adjacent numbers specifying the interaction distances in Angstroms (Å). (B) Corresponding 2D ligand interaction diagrams for the docked (top) and experimental (bottom) poses. Residue spheres are colored by chemical property: green (hydrophobic), blue (polar), purple (basic), and orange (acidic). Purple arrows indicate hydrogen bond directionality (donor to acceptor). (C) Structural alignment of the experimental (red) and docked (green) leucine poses. The low root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.68 Å confirms the high accuracy of the docking protocol, while the docking score of −6.15 kcal/mol indicates a favorable theoretical binding affinity.

![Molecules 30 04791 g001 Molecules 30 04791 g001]()

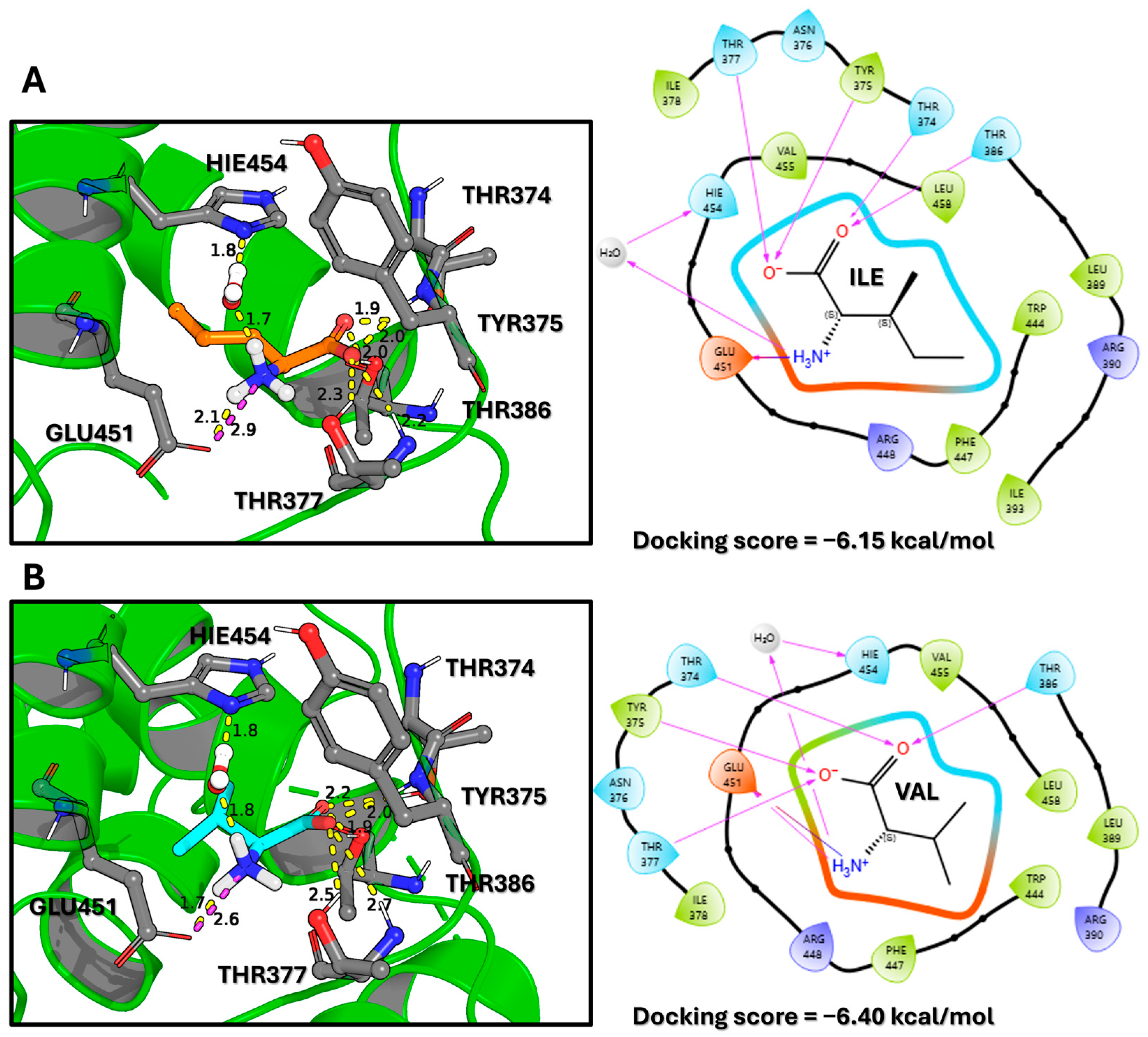

Figure 2.

Predicted Binding Modes and Interaction Profiles of Isoleucine and Valine. (A) 3D visualization of the docked isoleucine ligand (orange sticks) within the SESN2 binding pocket (green ribbons). Interacting amino acid residues are shown as grey sticks. Yellow dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds, with adjacent numbers indicating bond lengths in Angstroms (Å). The corresponding 2D interaction diagram (right) depicts residue spheres colored by chemical property: green (hydrophobic), blue (polar), purple (basic), and orange (acidic). Purple arrows denote hydrogen bond directionality (donor to acceptor). (B) 3D visualization of the docked valine ligand (cyan sticks) and its 2D interaction diagram (right), which follows the same color scheme as in (A). Both ligands maintain a conserved interaction network anchored by residues GLU451 and HIS454. The favorable docking scores (−6.15 kcal/mol for isoleucine and −6.40 kcal/mol for valine) suggest strong binding affinities, comparable to that of leucine.

Figure 2.

Predicted Binding Modes and Interaction Profiles of Isoleucine and Valine. (A) 3D visualization of the docked isoleucine ligand (orange sticks) within the SESN2 binding pocket (green ribbons). Interacting amino acid residues are shown as grey sticks. Yellow dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds, with adjacent numbers indicating bond lengths in Angstroms (Å). The corresponding 2D interaction diagram (right) depicts residue spheres colored by chemical property: green (hydrophobic), blue (polar), purple (basic), and orange (acidic). Purple arrows denote hydrogen bond directionality (donor to acceptor). (B) 3D visualization of the docked valine ligand (cyan sticks) and its 2D interaction diagram (right), which follows the same color scheme as in (A). Both ligands maintain a conserved interaction network anchored by residues GLU451 and HIS454. The favorable docking scores (−6.15 kcal/mol for isoleucine and −6.40 kcal/mol for valine) suggest strong binding affinities, comparable to that of leucine.

![Molecules 30 04791 g002 Molecules 30 04791 g002]()

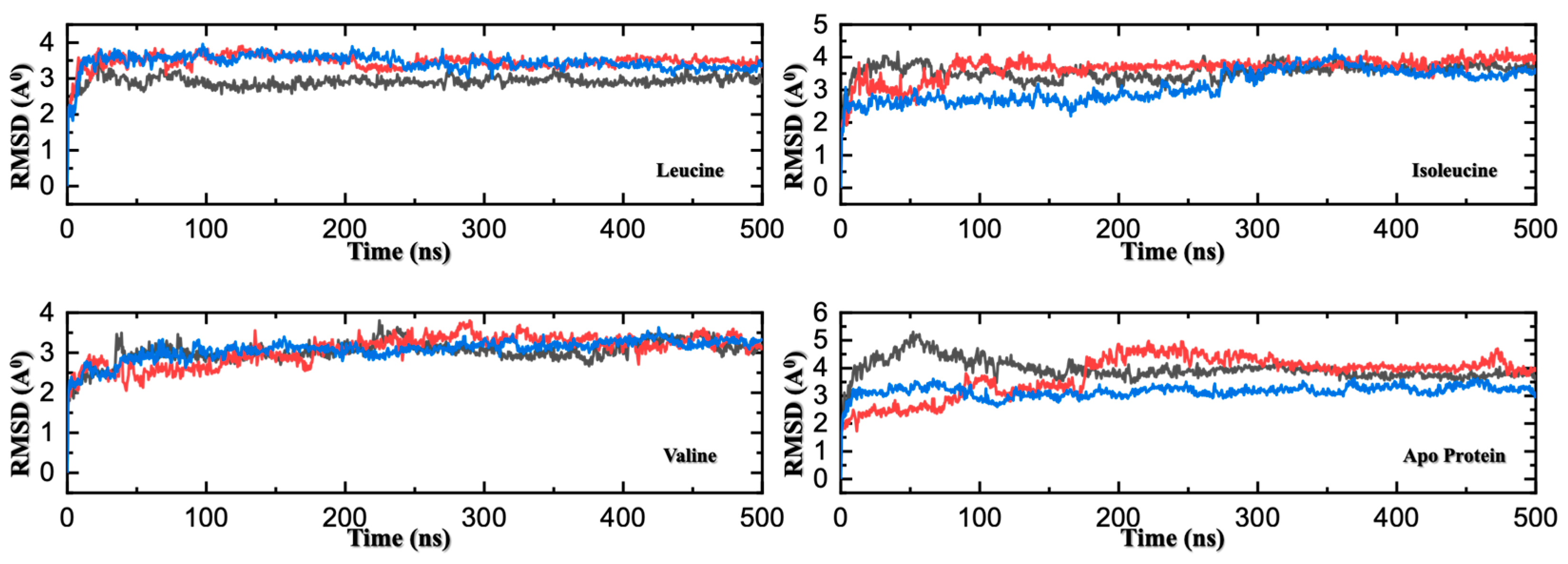

Figure 3.

RMSD Comparison of Three MD Replicates for Apo and Ligand-Bound SESN2. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) trajectories of backbone atoms for three independent 500 ns molecular dynamics replicates of SESN2 in its apo form and in complex with leucine, isoleucine, or valine. Each panel corresponds to one system, with three colored traces (red, blue, and black) representing individual replicates. All systems reach equilibration within ~25 ns. Leucine- and valine-bound systems display low RMSD variability across replicates, indicating high structural stability and reproducibility. In contrast, the apo and isoleucine-bound forms exhibit greater fluctuations and greater divergence between replicates, reflecting increased conformational flexibility and reduced stabilization upon binding.

Figure 3.

RMSD Comparison of Three MD Replicates for Apo and Ligand-Bound SESN2. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) trajectories of backbone atoms for three independent 500 ns molecular dynamics replicates of SESN2 in its apo form and in complex with leucine, isoleucine, or valine. Each panel corresponds to one system, with three colored traces (red, blue, and black) representing individual replicates. All systems reach equilibration within ~25 ns. Leucine- and valine-bound systems display low RMSD variability across replicates, indicating high structural stability and reproducibility. In contrast, the apo and isoleucine-bound forms exhibit greater fluctuations and greater divergence between replicates, reflecting increased conformational flexibility and reduced stabilization upon binding.

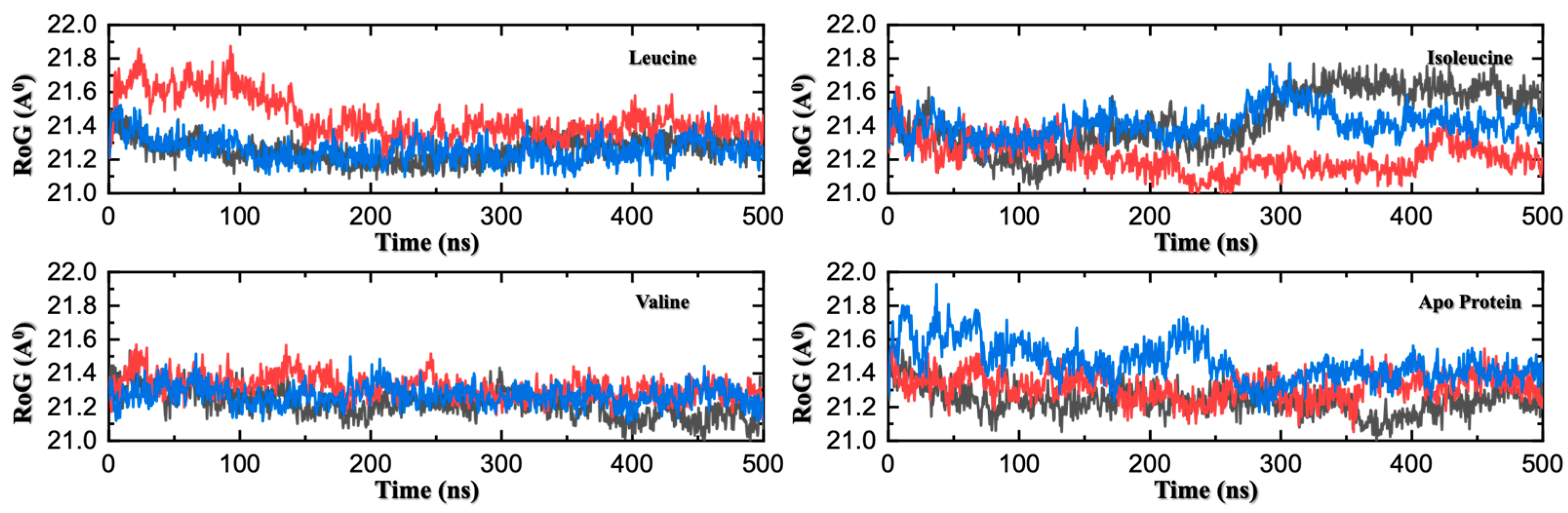

Figure 4.

Radius of Gyration (Rg) Comparison Across Three MD Replicates of Apo and Ligand-Bound SESN2. Time evolution of the Rg for three independent 500 ns MD replicates. Each panel corresponds to one system, with three colored traces (red, blue and black) representing individual replicates. While the average Rg is similar across all systems, the leucine- and valine-bound complexes exhibit markedly reduced fluctuations and more stable Rg values over time. This demonstrates that ligand binding locks the protein into a conformationally stable state, dampening the large-scale motions observed in the more flexible apo and isoleucine-bound forms.

Figure 4.

Radius of Gyration (Rg) Comparison Across Three MD Replicates of Apo and Ligand-Bound SESN2. Time evolution of the Rg for three independent 500 ns MD replicates. Each panel corresponds to one system, with three colored traces (red, blue and black) representing individual replicates. While the average Rg is similar across all systems, the leucine- and valine-bound complexes exhibit markedly reduced fluctuations and more stable Rg values over time. This demonstrates that ligand binding locks the protein into a conformationally stable state, dampening the large-scale motions observed in the more flexible apo and isoleucine-bound forms.

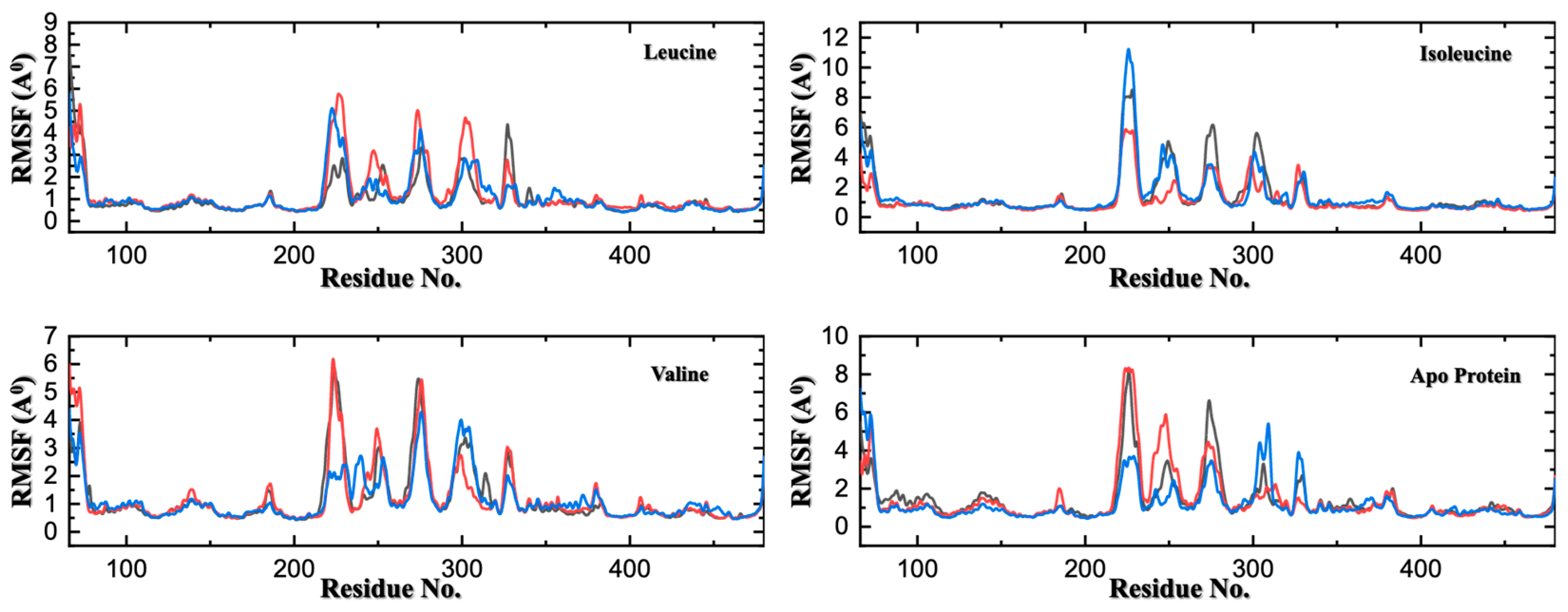

Figure 5.

Residue-Level Flexibility Analysis via Cα-RMSF Across Three MD Replicates. Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) profiles of Cα atoms, with each colored line (red, blue, and black) in the panels representing one of the three independent 500 ns simulations for SESN2 in its apo form and in complex with leucine, isoleucine, or valine. The analysis shows consistent flexibility patterns across the replicates. Leucine and valine binding not only rigidifies residues in the binding pocket but also allosterically dampens the flexibility of distant loop regions (e.g., residues ~240–260). In contrast, the apo and isoleucine-bound forms exhibit significantly greater mobility in these regions, indicating weaker conformational restraint.

Figure 5.

Residue-Level Flexibility Analysis via Cα-RMSF Across Three MD Replicates. Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) profiles of Cα atoms, with each colored line (red, blue, and black) in the panels representing one of the three independent 500 ns simulations for SESN2 in its apo form and in complex with leucine, isoleucine, or valine. The analysis shows consistent flexibility patterns across the replicates. Leucine and valine binding not only rigidifies residues in the binding pocket but also allosterically dampens the flexibility of distant loop regions (e.g., residues ~240–260). In contrast, the apo and isoleucine-bound forms exhibit significantly greater mobility in these regions, indicating weaker conformational restraint.

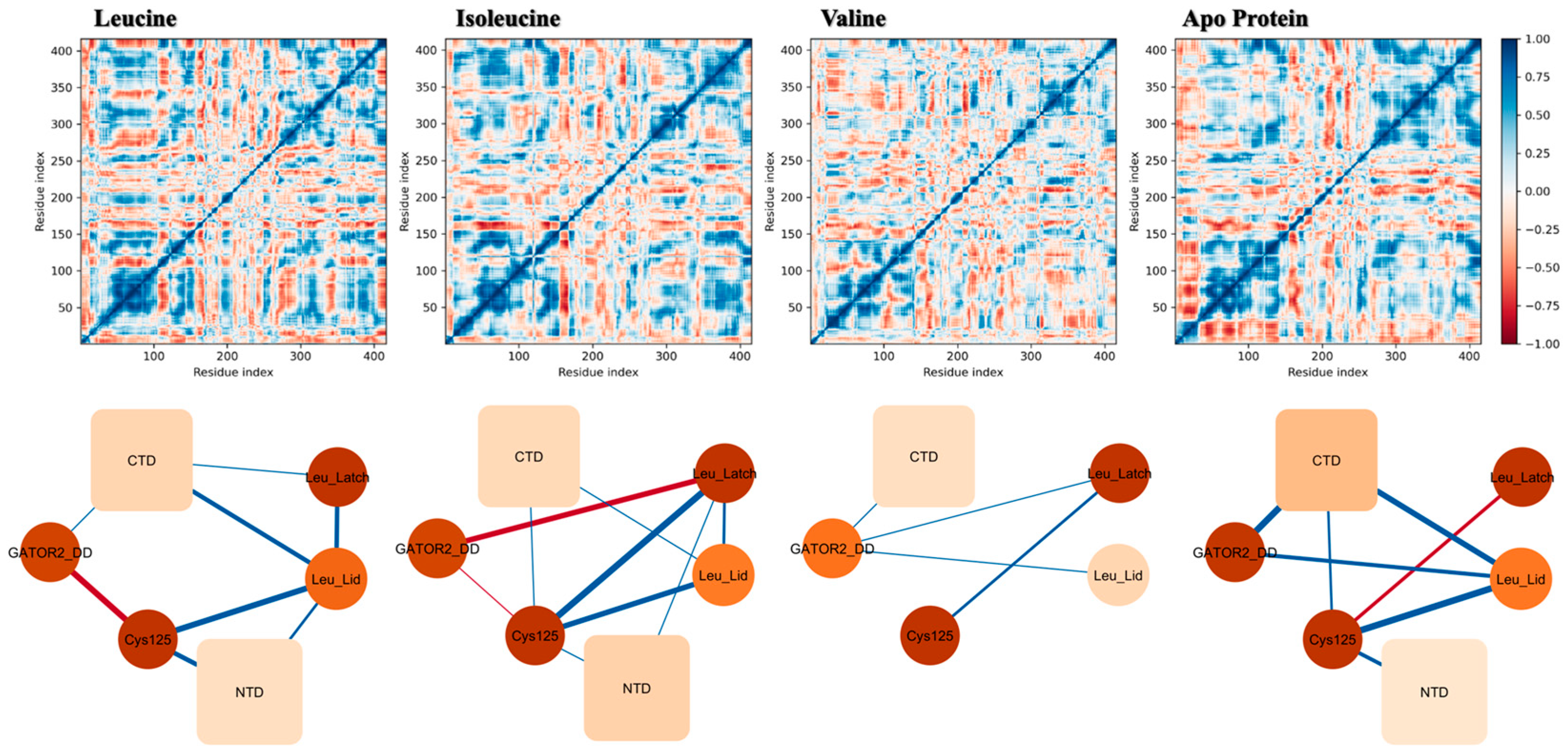

Figure 6.

Dynamic Cross-Correlation Analysis Reveals a Leucine-Specific Allosteric Communication Network. (Top Panels) Dynamic cross-correlation matrices (CCMs) showing pairwise residue motion correlation computed from concatenated MD trajectories. Strong positive correlations (coordinated motion) are colored deep blue, whereas strong negative correlations (anti-correlated motion) are deep red. (Bottom Panels) Simplified network models representing the average correlations between key functional domains. Nodes represent the C-terminal domain (CTD), N-terminal domain (NTD), the GATOR2 docking domain (GATOR2_DD), the redox-sensitive cysteine (Cys125), and leucine-binding microdomains (Leu_Lid, Leu_Latch). The thickness of the edges is proportional to the correlation strength (blue for positive, red for negative). The analysis reveals that only leucine binding establishes a strong, fully connected allosteric network, providing a physical pathway for the binding signal to be transmitted to distal functional sites.

Figure 6.

Dynamic Cross-Correlation Analysis Reveals a Leucine-Specific Allosteric Communication Network. (Top Panels) Dynamic cross-correlation matrices (CCMs) showing pairwise residue motion correlation computed from concatenated MD trajectories. Strong positive correlations (coordinated motion) are colored deep blue, whereas strong negative correlations (anti-correlated motion) are deep red. (Bottom Panels) Simplified network models representing the average correlations between key functional domains. Nodes represent the C-terminal domain (CTD), N-terminal domain (NTD), the GATOR2 docking domain (GATOR2_DD), the redox-sensitive cysteine (Cys125), and leucine-binding microdomains (Leu_Lid, Leu_Latch). The thickness of the edges is proportional to the correlation strength (blue for positive, red for negative). The analysis reveals that only leucine binding establishes a strong, fully connected allosteric network, providing a physical pathway for the binding signal to be transmitted to distal functional sites.

![Molecules 30 04791 g006 Molecules 30 04791 g006]()

Figure 7.

Quantitative Analysis of Protein–Ligand Interactions Throughout MD Simulations. Interaction fraction plots showing the percentage of simulation time that specific interactions—hydrogen bonds (green), hydrophobic contacts (purple), electrostatic interactions (red), and water bridges (blue)—are maintained between SESN2 residues and each bound ligand. The data demonstrates that leucine forms the most extensive, diverse, and persistent set of interactions, providing an atomic-level explanation for its superior binding affinity.

Figure 7.

Quantitative Analysis of Protein–Ligand Interactions Throughout MD Simulations. Interaction fraction plots showing the percentage of simulation time that specific interactions—hydrogen bonds (green), hydrophobic contacts (purple), electrostatic interactions (red), and water bridges (blue)—are maintained between SESN2 residues and each bound ligand. The data demonstrates that leucine forms the most extensive, diverse, and persistent set of interactions, providing an atomic-level explanation for its superior binding affinity.

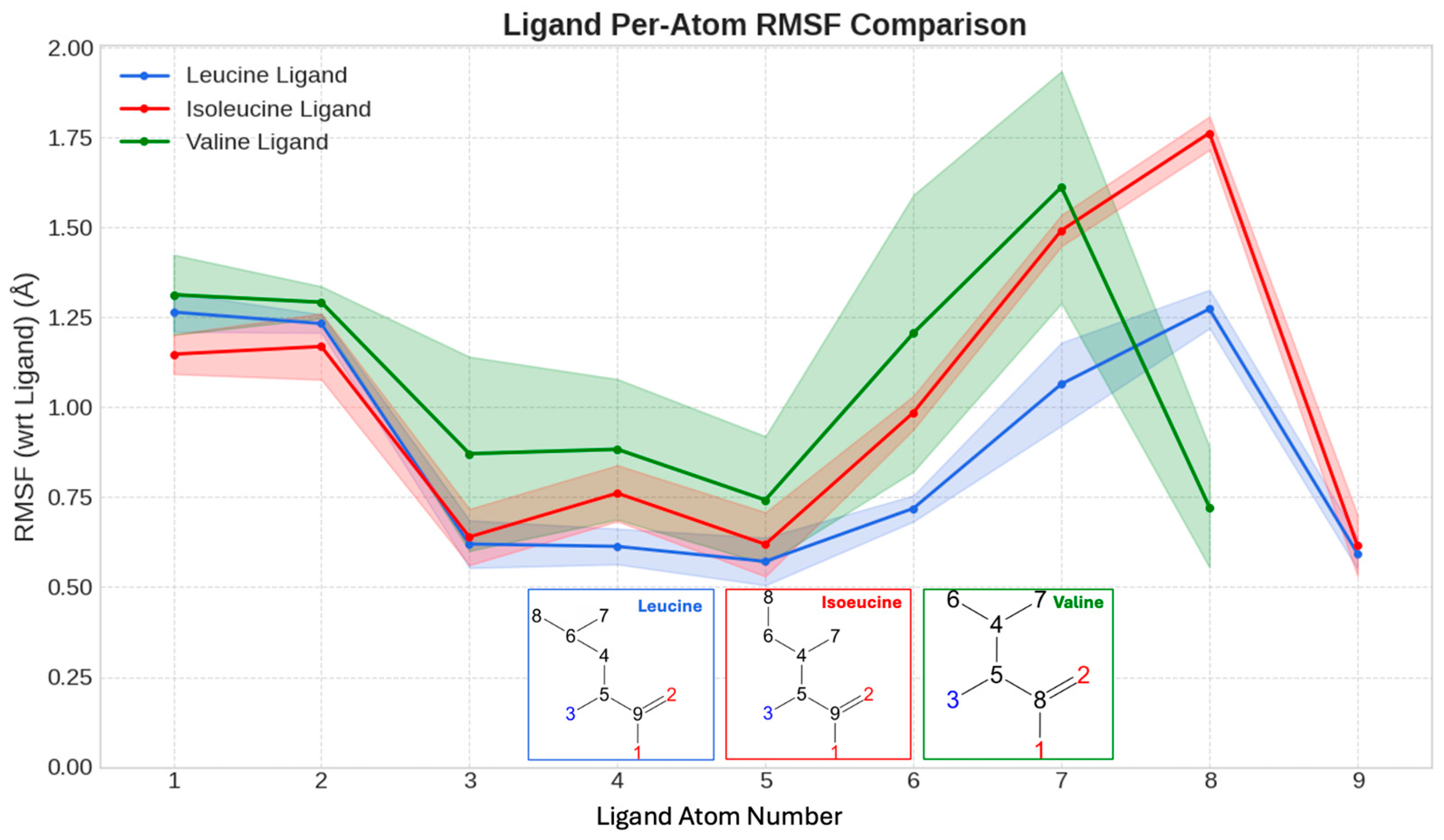

Figure 8.

Positional Stability of Bound Ligands within the SESN2 Pocket. Per-atom root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF, in Å) for the heavy atoms of leucine, isoleucine, and valine during their respective simulations. Lower RMSF values indicate a more rigidly held, stable atom. Inset diagrams show the atom numbering used for the RMSF calculation on the x-axis. Leucine’s atoms exhibit the lowest fluctuations, confirming that its extensive interaction network tightly anchors it. The data reveal a clear ligand-stability hierarchy (Leucine < Isoleucine < Valine) that mirrors the binding affinities.

Figure 8.

Positional Stability of Bound Ligands within the SESN2 Pocket. Per-atom root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF, in Å) for the heavy atoms of leucine, isoleucine, and valine during their respective simulations. Lower RMSF values indicate a more rigidly held, stable atom. Inset diagrams show the atom numbering used for the RMSF calculation on the x-axis. Leucine’s atoms exhibit the lowest fluctuations, confirming that its extensive interaction network tightly anchors it. The data reveal a clear ligand-stability hierarchy (Leucine < Isoleucine < Valine) that mirrors the binding affinities.

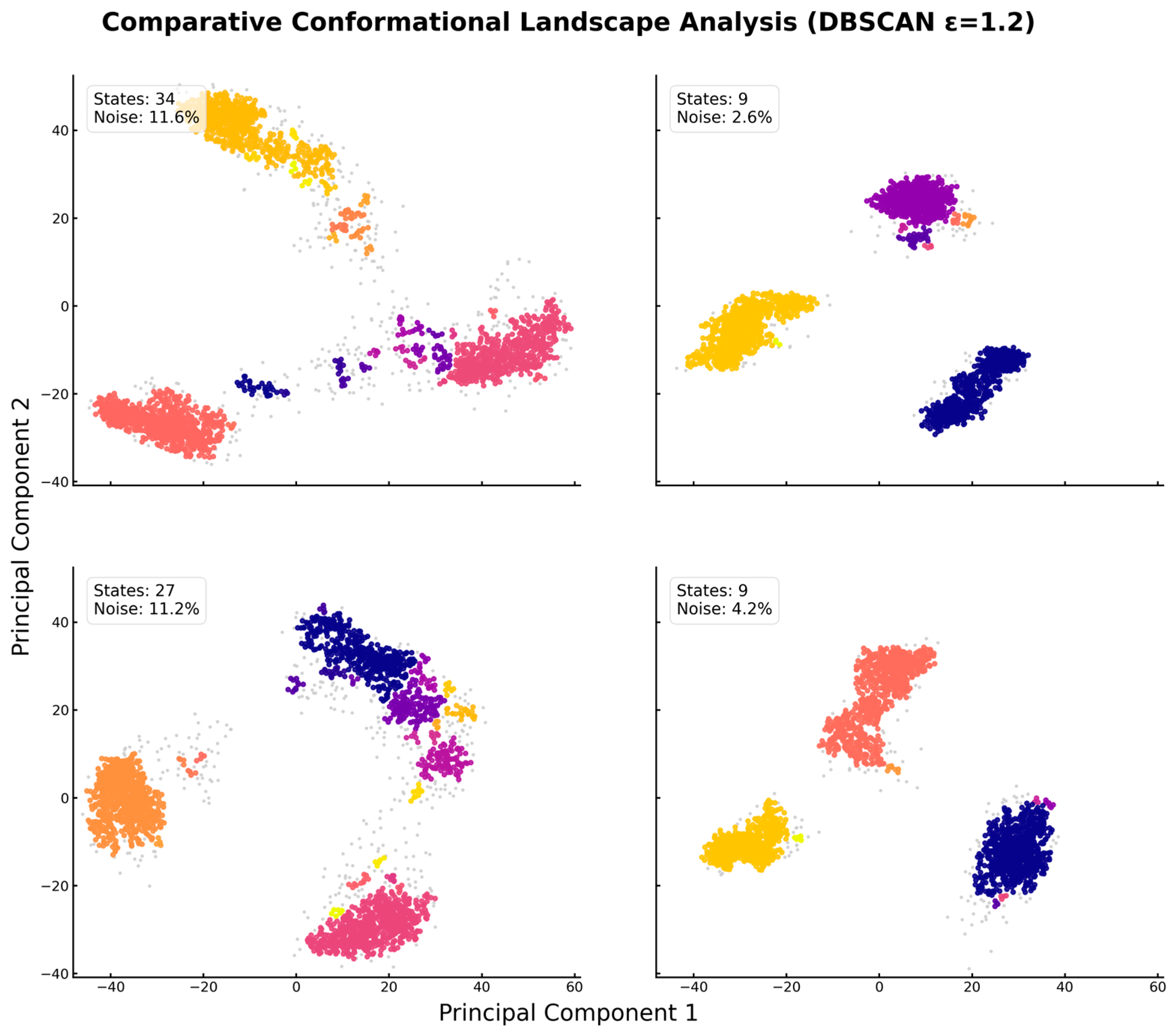

Figure 9.

Quantitative Clustering of Conformational Landscapes via DBSCAN Analysis Reveals Ligand-Induced Collapse. Projection of the Cα atom trajectories onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), with distinct colors in each panel representing unique stable conformational states identified by the clustering algorithm, and gray points representing transitional noise. (Top-Left) The apo-protein explores a vast landscape, sampling 34 distinct states with significant time (11.6%) in transitional conformations. (Top-Right) Leucine binding induces a dramatic collapse, restricting the protein to just 9 well-defined states and minimizing time spent in transitions (2.6% noise). (Bottom-Left) The isoleucine-bound form remains conformationally heterogeneous, similar to the apo state (27 states). (Bottom-Right) Valine binding also restricts the landscape to 9 stable states. In each panel, distinct colors represent unique stable conformational clusters, while gray points represent transitional “noise” conformations that do not belong to any stable state. This analysis provides direct, quantitative evidence of the “conformational locking” mechanism driven by leucine and valine.

Figure 9.

Quantitative Clustering of Conformational Landscapes via DBSCAN Analysis Reveals Ligand-Induced Collapse. Projection of the Cα atom trajectories onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), with distinct colors in each panel representing unique stable conformational states identified by the clustering algorithm, and gray points representing transitional noise. (Top-Left) The apo-protein explores a vast landscape, sampling 34 distinct states with significant time (11.6%) in transitional conformations. (Top-Right) Leucine binding induces a dramatic collapse, restricting the protein to just 9 well-defined states and minimizing time spent in transitions (2.6% noise). (Bottom-Left) The isoleucine-bound form remains conformationally heterogeneous, similar to the apo state (27 states). (Bottom-Right) Valine binding also restricts the landscape to 9 stable states. In each panel, distinct colors represent unique stable conformational clusters, while gray points represent transitional “noise” conformations that do not belong to any stable state. This analysis provides direct, quantitative evidence of the “conformational locking” mechanism driven by leucine and valine.

![Molecules 30 04791 g009 Molecules 30 04791 g009]()

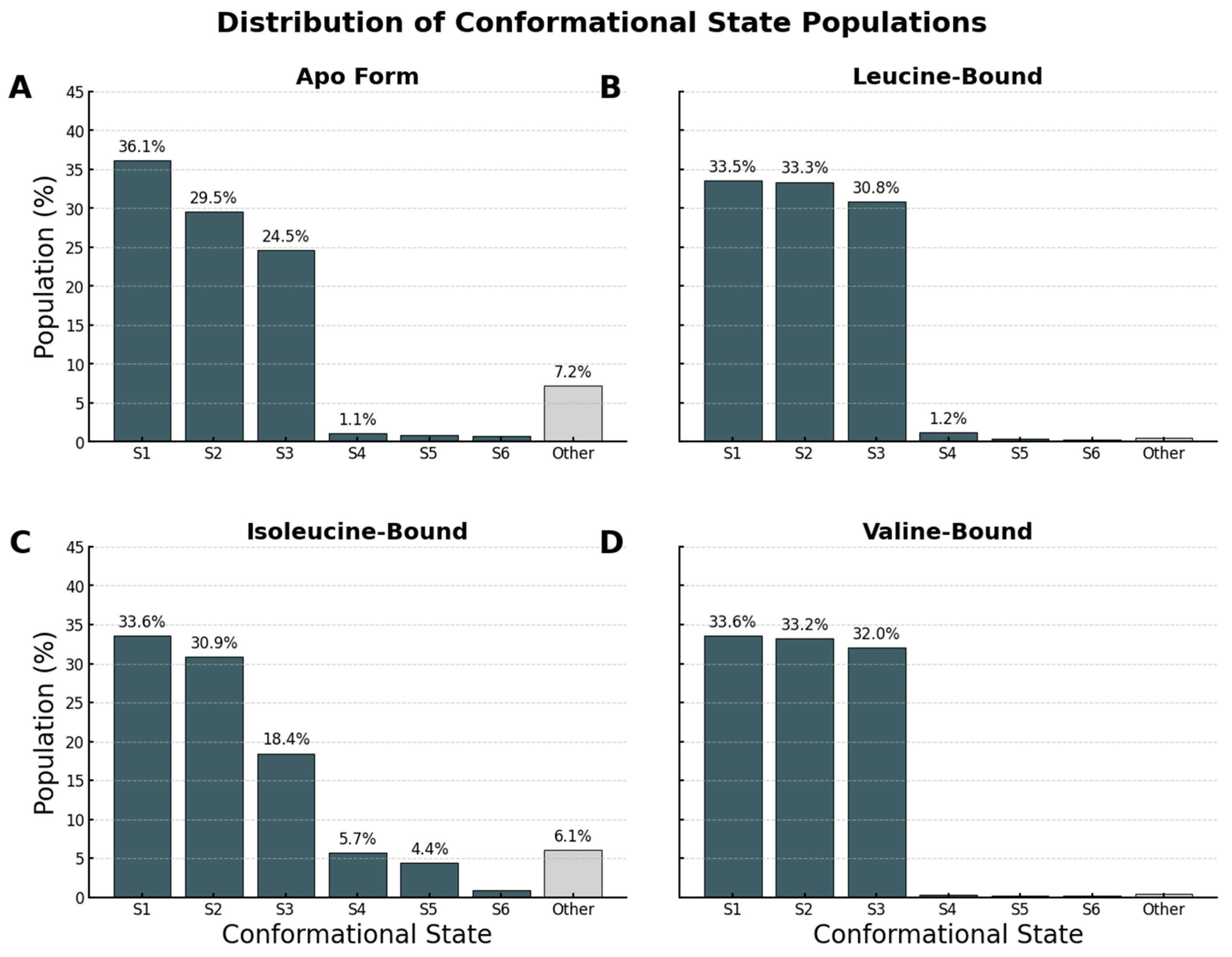

Figure 10.

Quantitative Population Analysis of Conformational States. Distribution of conformational state populations identified by DBSCAN clustering of the trajectories projected onto PC1 and PC2. In all panels, dark grey bars represent distinct stable macrostates (S1–S6), while the light grey “Other” bar aggregates the remaining low-population microstates and transitional noise. (A) The Apo form exhibits a broad distribution, with a large “Other” population (7.2%), consistent with high entropy. (B) Leucine binding consolidates the ensemble into three dominant states (S1–S3). (C) The Isoleucine-bound system retains significant heterogeneity, similar to that of the apo form. (D) Valine binding mirrors the leucine effect, showing a stabilized landscape dominated by three major states. These data provide quantitative evidence that leucine and valine drive a conformational locking mechanism, whereas isoleucine fails to stabilize a specific, distinct conformation.

Figure 10.

Quantitative Population Analysis of Conformational States. Distribution of conformational state populations identified by DBSCAN clustering of the trajectories projected onto PC1 and PC2. In all panels, dark grey bars represent distinct stable macrostates (S1–S6), while the light grey “Other” bar aggregates the remaining low-population microstates and transitional noise. (A) The Apo form exhibits a broad distribution, with a large “Other” population (7.2%), consistent with high entropy. (B) Leucine binding consolidates the ensemble into three dominant states (S1–S3). (C) The Isoleucine-bound system retains significant heterogeneity, similar to that of the apo form. (D) Valine binding mirrors the leucine effect, showing a stabilized landscape dominated by three major states. These data provide quantitative evidence that leucine and valine drive a conformational locking mechanism, whereas isoleucine fails to stabilize a specific, distinct conformation.

Table 1.

MM/GBSA Binding Free Energy and Component Analysis for BCAA-SESN2 Complexes. All energy values are in kcal/mol and represent the average ± standard deviation from three independent 500 ns MD simulations. ΔGbind is the total binding free energy. ΔEvdW and ΔECoulomb are the van der Waals and electrostatic contributions, respectively. ΔGLipo and ΔGSolvGB are the non-polar and polar solvation free energy terms. EStrainLig is the strain energy of the ligand in its bound conformation.

Table 1.

MM/GBSA Binding Free Energy and Component Analysis for BCAA-SESN2 Complexes. All energy values are in kcal/mol and represent the average ± standard deviation from three independent 500 ns MD simulations. ΔGbind is the total binding free energy. ΔEvdW and ΔECoulomb are the van der Waals and electrostatic contributions, respectively. ΔGLipo and ΔGSolvGB are the non-polar and polar solvation free energy terms. EStrainLig is the strain energy of the ligand in its bound conformation.

| Energy Term (kcal/mol) | Leucine | Isoleucine | Valine |

|---|

| ΔGbind (MMGBSA) | −37.60 ± 2.39 * | −34.47 ± 1.98 | −30.32 ± 3.18 |

| ΔEvdW | −28.09 ± 1.28 | −25.92 ± 1.38 | −21.96 ± 1.29 |

| ΔECoulomb | 13.13 ± 3.33 | 14.59 ± 2.89 | 11.27 ± 2.15 |

| ΔGLipo | −8.25 ± 0.59 | −7.42 ± 0.45 | −5.92 ± 0.61 |

| ΔGSolvGB | −12.30 ± 1.87 | −13.12 ± 1.55 | −11.10 ± 1.93 |

| EStrainLig | 0.66 ± 0.62 | 0.52 ± 0.27 | 0.41 ± 0.32 |

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Conformational Landscapes via DBSCAN Clustering. Quantitative results from the density-based clustering of the conformational space sampled by each system. “# Stable States” is the number of distinct conformational clusters identified. “% Noise (Transitions)” is the percentage of simulation time spent in low-density regions between stable states. “% in Largest State” is the population of the single most-populated conformational state. The data quantify the dramatic reduction in conformational heterogeneity upon binding of leucine and valine.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Conformational Landscapes via DBSCAN Clustering. Quantitative results from the density-based clustering of the conformational space sampled by each system. “# Stable States” is the number of distinct conformational clusters identified. “% Noise (Transitions)” is the percentage of simulation time spent in low-density regions between stable states. “% in Largest State” is the population of the single most-populated conformational state. The data quantify the dramatic reduction in conformational heterogeneity upon binding of leucine and valine.

| System | # Stable States | % Noise (Transitions) | % in Largest State |

|---|

| Apo Form | 35 | 11.6% | 36.1% |

| Isoleucine-Bound | 27 | 11.2% | 33.6% |

| Valine-Bound | 9 | 4.2% | 33.6% |

| Leucine-Bound | 9 | 2.6% | 33.5% |