Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) involve multiple per- and polyfluorinated compounds that are widely used globally. Legacy PFAS, including PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS, were manufactured before 2000 in various industrialized nations, then gradually phased out in accordance with the Stockholm Convention. Due to the substantial accumulation of these legacy PFAS compounds, their concentrations in drinking water are regulated in some countries. This review first summarizes the historical background of PFAS, followed by a description of their chemical properties. The clinical manifestations of legacy PFAS in humans, such as dyslipidemia, attenuated immune function, and chronic kidney disorders, are also summarized. Emerging PFAS involve Gen-X and F-53B as well as numerous newly developed chemicals with their associated precursors/metabolites, including volatile PFAS. Research on these emerging PFAS compounds in the environment continues to grow, building a substantial body of evidence about their effects. The chemical structure of emerging PFAS shows a wide variety: they could contain ether, ester, sulfoneamide, and other halogen atoms rather than fluorine. Volatile PFAS involve the fluorotelomer 6:2 FTOH and other short-chain PFAS compounds, which are best measured by GC-MS. This review also briefly summarizes the assay for total oxidizable precursors of PFAS, an LC-MS-based assay for an emerging assay that will be used for a quantitative estimation of total PFAS, including emerging PFAS.

1. Introduction

1.1. History

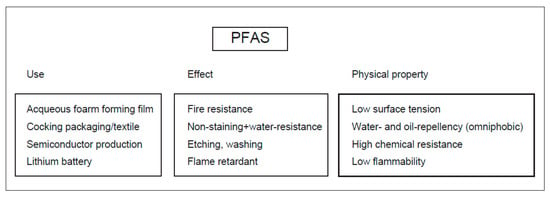

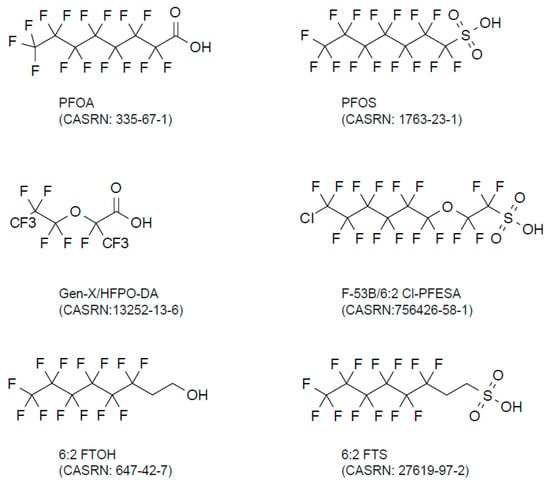

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been used in a wide variety of applications, such as aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), nonstick cookware, rubber packing materials, water-repellent fabrics, food packaging, cosmetics, and pesticides [1,2,3] (Figure 1). In 1938, Teflon (R), a prototypical PFAS, was invented by DuPont. PFAS are less susceptible to chemical degradation; thus, they are called “forever chemicals.” PFAS are an anthropogenic group of chemicals that are routinely detected in many industrialized countries in almost all samples (Table 1). Before 2000, a variety of PFAS compounds were produced. After the early 2000s, some major PFAS were phased out. Specifically, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS, Figure 2) was first listed in the Stockholm Convention in 2009. Subsequently, perfluorooctanic acid (PFOA) was added in 2019, followed by perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS) in 2022. In 2025, many industrialized countries followed this proposal [3].

Figure 1.

The uses, effects, and physical properties of PFAS.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of PFAS.

This review article aims to overview the industrial history and chemical application of PFAS, as well as its remediation technique to conserve the global environment. Currently available data for remediation and health concerns are almost limited to legacy PFAS. The author wishes to summarize such legacy-PFAS-related data first, then expand the discussion for emerging PFAS-related issues. Furthermore, for the research paper on PFAS distribution, the geological fairness of the US, the EU, Asia, and the rest of the world was considered. The current concentration of emerging PFAS is still relatively low in soil, water, and atmosphere. However, an increasing number of studies raises a concern for the conversion to volatile PFAS from legacy PFAS. Thus, the author’s motivation will be focused on the environmental and biological outcome of currently producing emerging PFAS around the globe. This is a narrative review of published articles found in the PubMed database (Section 1, Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4). The cited articles of Section 5 (Perspectives) were selected from articles published in PubMed during the last 5 years.

1.2. Nomenclature: Legacy PFAS and Emerging PFAS

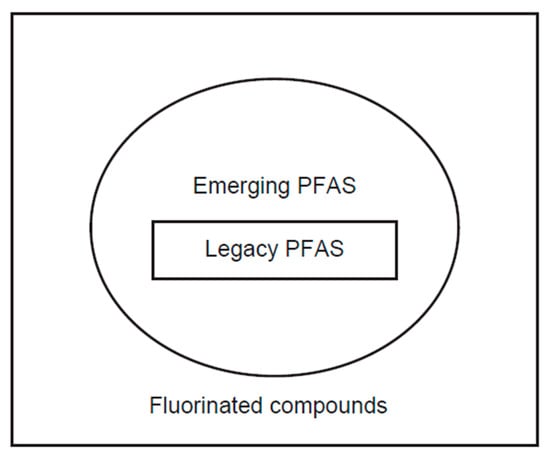

1.2.1. Legacy PFAS

Currently, more than thousands of PFAS chemicals have been synthesized. While the term ‘legacy PFAS’ was not officially defined, this term itself is commonly found in recent publications [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] (Figure 3). It contains PFOA, PFOS, and several similar compounds with different chain lengths, such as PFUnDA (C10), PFNA (C9), PFHpA (C7), PFHxA (C6), and PFPA (C5). These well-characterized series of legacy PFAS species are routinely quantified using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [12] (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Legacy PFAS, emerging PFAS, and fluorinated compounds.

Table 1.

Quantification procedure for PFASs.

Table 1.

Quantification procedure for PFASs.

| Method | Target | Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS | Legacy PFAS | Food | [13] |

| Legacy PFAS | Food | [14] | |

| Legacy PFAS | Food | [15] | |

| Legacy PFAS | Drinking water, river water, sea water | [16] | |

| Legacy PFAS | Human serum | [17] | |

| GC-MS | Volatile PFAS | Indoor air | [18] |

| LC-Q-TOF | Non-target | Food | [15] |

| GC-Q-TOF | Volatile PFAS | Water | [19] |

| EOF | Total fluoride | Soil | [20] |

| TOP + EOF | Total fluoride | Honeybees and bee-collected pollen | [21] |

| Total fluoride | Sugarcane pulp, tableware | [22] | |

| Total fluoride | Outdoor textiles, paper packaging, carpeting, and permanent baking sheets | [23] | |

| Total fluoride | Ski wax, snowmelts, and soil from skiing areas | [24] | |

| Total fluoride | Pooled human serum | [25] | |

| Total fluoride | Dust | [26] | |

| Total fluoride | Cosmetics | [27] |

EOF, extractable organic fluoride; GC, gas chromatography; LC, liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; Q, quadrupole; TOP, total oxidizable precursors.

1.2.2. Emerging PFAS

Emerging PFAS is another widely used term for newly developed PFAS compounds and their precursors/metabolites that are not included in legacy PFAS [1]. Recent evidence has demonstrated that these emerging PFAS are now widely detectable (reviewed in [28,29]) (Table 2). Emerging PFAS include Gen-X (hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid, also known as HFPO-DA) and F-53B (2-((6-chloro-1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6-dodecafluorohexyl)oxy)-1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethanesulfonic acid) [30] (Figure 2). Gen-X constitutes a common short-chain PFAS alternative, replacing PFOA, the linear long-chain PFOA representing the most common PFAS. F-53B is an alternative to the PFOS used in the industry, offering wide applications in manufacturing. These emerging PFAS usually contain, but are not limited to, an ether group [31]. 6:2 FTOH and 6:2 FTS are fluorotelomer PFAS, also classified as emerging PFAS. Based on these structures, there are also many telomer-structured emerging PFAS that might contain amide, ester, branched alkane, alkene, halogen atom, or other functional groups. In these cases, each perfluorinated compound, such as 6:2 FTOH, has a shorter carbon chain (C ≤ 6 in PFOS) [32]. Some such short-chained emerging PFAS are also called volatile PFAS; they are better quantified using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) than LC-MS (Table 1). These shorter-chain PFAS accumulate in the air as the decomposition product of parental emerging PFAS by either chemical or biological pathways [2]. The biological effects of the emerging PFAS appeared to be similar [33]. The pharmacokinetics of emerging PFAS’ excretion from the human body have yet to be established.

Table 2.

Reported emerging PFAS in the environment and humans.

Gen-X and F-53B

These are well-characterized emerging PFAS compounds with a chemical nature [33] (Figure 2). Although Gen-X and F-53B are recently emerging PFAS, they are already detectable globally. The quantification of Gen-X and F-53B was performed in LC-MS/MS (Table 2). These data demonstrate that the concentrations of Gen-X and F-53B are relatively lower than those of legacy PFAS, such as PFOS. It seems too early to discuss the biological effects of Gen-X and F-53 due to their small accumulation in humans. Furthermore, the inability to assess the authentic effects of Gen-X and F-53B in humans only allows us to estimate them for ethical reasons. This is due to widespread legacy PFAS contamination that cannot be properly controlled for in epidemiological studies.

Volatile PFAS

Volatile PFAS, such as PFBA, have attracted much attention [18]. How these volatile PFAS might have a deteriorating effect on humans remains unestablished. This is partly due to the quantification procedures used for these volatile PFAS. These concentrations should be carefully determined; otherwise, some or most PFAS might be lost during sample collection, storage, and pretreatment before analysis.

We might have an additional understanding of emerging PFAS substances when PFAS mitigation has been employed. Electrostatic interactions between carbons and fluoride in emerging PFAS are similarly found in legacy PFAS; thus, the bioremediation of emerging PFAS seems to undergo nearly similar efficiency. However, because they have a distinct structure from legacy PFAS, emerging PFAS are less likely to be microbiologically processed than PFOS.

1.3. PFAS Synthesis

The synthesis of PFAS has two separate methods [1]. One involves electrochemical fluorination, which replaces all hydrogen with fluoride in an electrochemical manner. This method has a high efficiency of fluoride replacement, while a branched PFAS has also been obtained at a high yield [40]. Another method involves the fluorotelomeric method, which allows higher efficiency of linear PFAS [41]. Terminal iodine acts as a hub for further reactions, such as hydroxylation and carboxylation.

1.4. PFAS Quantification

1.4.1. LC-MS

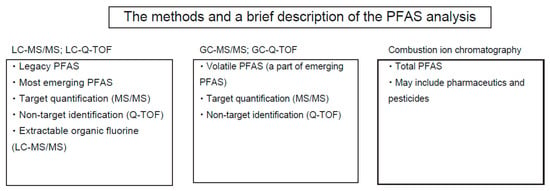

LC-MS is a widely used quantitative platform for PFAS species for legacy PFAS with C ≥ 4 compounds [12] (Table 1) (Figure 4). For quantification, reversed-phase chromatography with MS/MS detection is employed. This assay has been used for a variety of specimens, such as soil, drinking water, food, serum, and plasma of humans and animals. Among the many legacy PFAS compounds, PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS are routinely quantified for biomonitoring. In the U.S., the EU, and some other industrialized countries, such as Canada and Australia, their regulatory authorities now request the monitoring of legacy PFAS in drinking water [42,43]. Some other countries, such as Japan, will follow this trend in the coming year [42]. For PFAS quantification in water, two international standards (ISO 21675:2019, EPA 533/537.1/1633) are effective [16,44].

Figure 4.

Analytical methods for PFAS.

For the pretreatment of samples, particularly food, the QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe) method is a sophisticated version of the multistep solid-phase extraction method developed by the United States Food and Drug Administration [13,14,15]. Currently, these services are commercially provided by multiple vendors. Essentially, a liquified sample was mixed with methyl tert-butyl ether, followed by the addition of MgSO4 as the desiccant. Collection of an organic layer allows a specimen to be ready for 1st solid-phase extraction, such as graphite carbon chromatography. Flow-through was collected and applied to a second solid-phase extraction, typically composed of weak anion exchange chromatography. Because most PFAS, such as PFOS and PFOA, are negatively charged at neutral pH, the elution of PFAS is achieved by an acidified solution to protonate a weak anion exchange resin. The collected eluate was then dried and concentrated when necessary, followed by an injection onto LC-MS/MS.

Each PFAS peak was separated using a C18 column and quantified by LC-MS/MS. It is well known that some species of bile acid comigrate with PFAS, leading to incorrect measurement of some PFAS [45,46]. For analytical laboratory consumables, a septum made with PFTE should be avoided because it generates contamination of fluorinated compounds. In cases where an unstable blank baseline of LC-MS/MS was observed, the insertion of a short trap column with the same packing materials as the analytical column between the upstream of the analytical column effectively eliminates contaminating PFAS for a high background.

The total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay has been developed to estimate the levels of total PFAS, which is an ammonium persulfate-oxidizable PFAS, using LC-MS/MS [47,48]. Under this reaction, perfluorosulfuric acid (PFSA) undergoes perfluorocarboxylic acid (PFCA) via a hydroxyl radical-mediated reaction. An increasing number of studies have reported PFAS data using the TOP assay, suggesting that an increase in the role of emerging PFAS in the environment and humans needs to be properly assessed in the future.

1.4.2. GC-MS

GC-MS is normally used for quantification of volatile PFAS, short-chained PFAS (C ≤ 4) species with high volatility [6,49] (Table 1). For enrichment of PFAS analytes, headspace solid-phase microextraction is routinely used. For derivatization, silylation and methoxylation are used for alcohol and aldehyde, respectively.

1.4.3. Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) Mass Spectrometry

To determine the chemical structure of unknown PFAS species, an untargeted quantification using a Q-TOF mass spectrometer was used (Table 1). Q-TOF allows the identification of unique compounds in a variety of samples, such as soil, drinking water, food, and human plasma [15]. Q-TOF is mainly used for the identification of unknown emerging PFAS. For volatile PFAS assay, GC-Q-TOF is accepted in a recent study [19].

1.4.4. Combustion Ion Chromatography

By increasing the number of emerging PFAS, there is an increasing demand to estimate the total concentration of PFAS. Current analytical methods employ LC-MS/MS for quantification and LC-Q-TOF for non-targeted screening of PFAS compounds. For LC-MS/MS assay, the analyte needs to be specified before quantification by LC-MS/MS with an appropriate internal standard. Alternatively, a non-target assay allows for the identification of unknown PFAS. In this case, it is impossible to quantify them due to a lack of proper internal standards. Thus, to estimate the total PFAS concentration, such a specific assay is needed.

Combustion ion chromatography (CIC) measures fluoride in the sample (Table 1). Depending on the sample preparation, a variety of methods have been proposed (Table 3). The total fluorine (TF) method quantifies fluoride in the sample without any sample pretreatment. Thus, endogenous inorganic fluoride might be predominant in liquid samples such as water, wet soil, and human plasma. The absorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method measures activated carbon-absorbable fluoride by CIC. In this case, the analyte essentially contains organic compounds. The extractable organic fluorine (EOF) method is similar to AOF, but EOF uses a variety of extraction procedures such as weak anion exchange. In EOF, the nature of target compounds would become more selective compared to AOF.

Table 3.

Comparison of method and purpose among TF, AOF, EOF, and TOP assay.

To determine what percentage of total fluoride is attributable to PFAS remains an open question. To achieve this, both EOF-derived total fluoride concentration and LC-MS/MS-derived specific PFAS concentration were compared [48]. As a result, PFAS accounted for only 1/5–1/8 in the EOF. A subsequent study revealed that most EOF was found to be from pharmaceuticals and pesticides [48]. In fact, a similar calculation has been made in separate studies [51,52]. Given that emerging PFAS usually have lower concentrations than legacy PFAS, such as PFOS, the usefulness of the EOF assay is expected in the future, particularly after legacy PFAS mitigation proceeds.

1.4.5. Comparison of Methodology

Currently available methodology for PFAS measurement is summarized (Table 4). Because PFAS are found in many matrices such as water, soil, food, human plasma, and industrial products, this author chose serum as a matrix for subsequent discussion. LC-MS generally provides a lower limit of detection or quantitation. It is a robust assay when matrix effects, such as ion suppression, are properly considered. GC-MS appears to be less sensitive compared to LC-MS, possibly because of the volatility and stability of target compounds. Apparently, these low limits of detection can be achieved when a proper internal standard is available. HRMS is used for non-target analysis with a reasonably low limit of detection, possibly due to an elimination of contaminated interference compounds. CIC has the advantage of total fluorine quantification but is less sensitive. This is because all mass spectrometric quantification is performed under vacuum, while the detection of CIC uses an electrical conductivity detector.

Table 4.

Quantification procedure for PFAS.

2. Distribution of PFAS

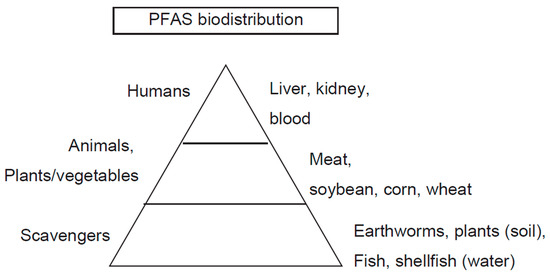

PFAS have been synthesized in almost all industrialized countries, such as the U.S., EU, Canada, Japan, Australia, China, and India. As a result, legacy PFAS have accumulated almost everywhere. Historically, PFAS had been found in soil, especially that which is close to chemical industries, as well as the places that have been previously used for airports, firefighting areas, and military areas [33] (Table 5). Water, such as river water, groundwater, and seawater, is another source of PFAS. Once PFAS accumulate in these waters, it is highly anticipated that fish and shellfish will be highly contaminated [57]. In humans, the intake of water and food is a major source of PFAS accumulation in the body (Figure 5). This leads to the regulation of PFAS concentrations in drinking water in some industrialized countries.

Table 5.

PFAS levels in various specimens.

Figure 5.

PFAS biodistribution.

2.1. Soil/Environmental Water

Since PFAS were first synthesized more than eight decades ago, PFAS are normally found everywhere at various levels [1] (Table 5). Perhaps, based on existing data, the U.S. is the country that has most extensively measured PFAS levels. In addition to previously described areas, rivers might show high PFAS concentrations when such places are located upstream. From the viewpoint of the conservation of land and water, a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) is another source of PFAS. Another area where PFAS are highly detectable involves landfills; in these cases, whether such a landfill might contain high PFAS or not is apparently clear.

2.2. Drinking Water

The levels of contaminants, such as chloride, pesticides, metals, and other chemicals in drinking water, have been highly regulated by every country’s authority. PFAS’ concentration in drinking water is consistently regulated in some countries [42,43,79]. In some studies, 45% of tap water in the U.S. contains at least one type of PFAS [80]. The regulatory threshold of PFAS in drinking water depends on each country, with its own criteria [42,43]. PFAS levels in drinking water might be affected by upstream water sources. Furthermore, PFAS levels in groundwater could also affect those in drinking water. After the effort of PFAS mitigation in water sources, such as soil, rivers, and landfills, PFAS levels, particularly PFOS, gradually decreased in the U.S. and Japan [2,81].

2.3. Food

Food is another source that potentially elevates PFAS in humans through the food chain. Like soil and drinking water, PFAS accumulation is also consistently found in many places. Lifetime-exposed dairy cattle contain high PFAS levels [82]. In aquatic living things, high PFAS levels in clams have been reported [67,68]. Consequently, potential PFAS contamination might reach freshwater fish [69]. In the EU, a study reported high PFAS accumulation in eggs [71]. In Japan, PFAS accumulation in a Pacific cod has been reported [73]. In this particular case, these fish were caught at sea, far from mainland Japan; thus, severe PFAS contamination of this marine area was a concern.

2.4. Biodistribution in Humans

2.4.1. Blood

Biomonitoring of PFAS in humans has been performed in many countries [2,33,83,84,85] (Table 6). Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated an increase in legacy PFAS concentrations before their phase-out. The half-life of PFAS ranges from one year to a decade in the order of PFHxS > PFOS > PFOA [86]. Importantly, a U.S. study demonstrated a decline in plasma PFAS, particularly PFOS, clearly demonstrating that an accumulated PFAS could be excreted in humans regardless of either endogenous or exogenous metabolic systems [2,81]. Food and water are two major routes of PFAS intake in humans. Fish and seafood are considered major sources of PFAS in the Japanese population.

Table 6.

Major manifestations of PFAS-exposed humans.

2.4.2. Liver

The liver is a major organ that metabolizes exogenous chemicals through a variety of reactions, such as oxidation, reduction, and conjugation. Consistently, a high concentration of PFOS was detected in the liver, followed by PFOA, PFNA, and PFHxS in humans [108]. Concerning the concentration of PFAS detected in the specimens, a comparison of this and a previous result obtained a decade ago, when PFAS production was not yet prohibited [99], revealed a marked reduction in newer specimens. Concerning PFAS species preference, this is also consistent with previous results in mice: it is known that long-chain PFCAs, such as PFOA (C8), PFNA (C9), PFDA (C10), and PFUnDA (C11), accumulate in the liver and plasma, while shorter-chained PFCAs, such as PFHpA (C7) and PFHxA (C6), are essentially excreted into the urine [81].

2.4.3. Kidney

Similar to the liver, the kidney is another organ where PFAS compounds tend to accumulate at high concentrations [108,109]. Organic anion transporter 4 has been the best-examined transporter of PFAS in the kidneys. Physiologically, the kidney plays a key role in PFAS excretion [81]. Specifically, PFOS and PFNA showed the highest renal excretion, with decreasing excretion in the longer PFCA. Excretion of PFAS in humans is two orders of magnitude slower than that in rats, possibly because of the high binding of PFAS to renal protein.

3. Clinical Manifestations

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that PFAS, particularly longer-chained PFAS, tend to remain in humans in contrast to rodents [2,81]. This suggests that humans are likely to exhibit several manifestations (Table 6). Among them, dyslipidemia, attenuated immune response, and renal disorder are described below.

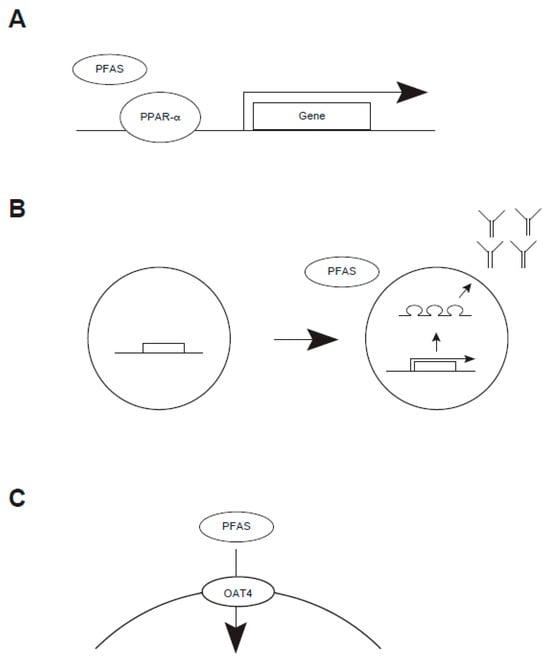

3.1. Dyslipidemia

An earlier study reported that total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were inversely correlated with PFAS concentrations, such as PFOS [110,111,112]. Such a trend might be found regardless of age and sex, raising the possibility that PFAS would modulate cholesterol accumulation in these populations in the same manner. On a molecular basis, several studies have suggested that PPAR-α may be involved in this bioprocess [81,113] (Figure 6). While an increase in cholesterol due to PFAS has been suggested in humans, a recent review concluded that PFAS accumulation appeared not to be linked to atherosclerosis [112]. While PPAR receptors accommodate a relatively wide variety of substrates, short-chained PFAS might not activate this receptor as effectively as long-chain ones do.

Figure 6.

Biochemical action of PFAS (A–C).

3.2. Attenuated Immune Response

An epidemiological study suggested that a high-PFAS exposure group seemed to be highly susceptible to COVID-19 [42,43]. Emerging evidence suggests a potential link between this and impaired antibody production [114] (Figure 6). Earlier studies reported the mortality of COVID-19-related events [94,97]. Subsequent studies elucidated that the level of antibodies against COVID-19-derived viral antigens was decreased in PFAS-exposed individuals [99,101]. Research on children with allergies found an unexpected result: those exposed to PFAS compounds demonstrated reduced sensitivity to food allergen reactions compared to unexposed children [115]. The role of PFAS on immune response might be modulated, at least in part, by NF-κB, PPAR, calcium signaling, and cytokine-mediated signaling; thus, future study will be required [116]. Whether the immunological outcome could be modulated by the chain length of PFAS remains uncertain.

3.3. Renal Disorder

Studies have shown that high plasma PFAS concentrations, such as PFOS, are correlated with renal disorder [7,117] (Table 6). A possible mechanism raises a potential link between PFAS and renal transportation through human organic acid transporter 4 [113] (Figure 6). One study reported that exposure to PFAS increased the severity of chronic kidney disease, while their mortality remained unchanged [118]. Increasing PFAS chain length has been shown to increase its OAT4-binding activity in legacy PFAS (PFCA and PFSA) and an emerging PFAS (FTSA) in vitro and in silico [119].

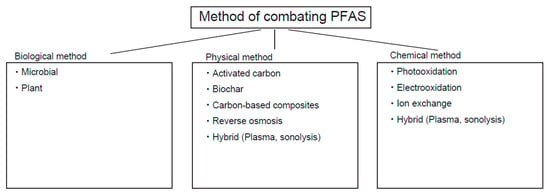

4. PFAS Mitigation

4.1. Removal Technology

As mentioned, PFAS are less susceptible to chemical degradation. The bond dissociation energy between a C-F bond is approximately 130 kcal/mol, higher than that of a C-H bond (110 kcal/mol) [120]. As mentioned, this chemical property is suitable for numerous applications of PFAS, such as AFFF, nonsticking chemicals, and other applications. However, this chemical property is problematic when its degradation needs to be discussed [1] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Methods of combating PFAS.

Physical Removal of PFAS

Physical adsorption processes, including activated carbons, biochar, carbon nanotubes, and carbon-based composites, have been evaluated for the removal of PFAS from various complex water matrices [60] (Table 7). All of these methods are essentially linked to carbon with different properties. Activated carbons are made from coal or oil-derived materials that have a high surface area for higher absorption of small molecules, such as PFAS. Biochar is also made of carbon from wood-derived charcoal with a high surface area and different chemical properties. Activated carbons are made at higher temperatures (~900 °C) compared to biochars (~300 °C). Activated carbons can be functionalized with additional chemical groups to enhance their properties, whereas biochars generally cannot undergo such modifications. Activated carbons and biochar are significantly more affordable than carbon nanotubes.

Table 7.

Engineering techniques for PFAS mitigation.

Carbon-based composites are crude materials made with biochars by fermentation with multiple bacteria before use. For binding these carbon materials to PFAS, the most important interaction involves the electrostatic interaction between carbons through π–π interaction. Ionic interactions could modulate PFAS binding with carbons. Similarly, hydrophilic interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, play a role in binding. Among these techniques, activated carbon and biochars have been shown to be effective for PFAS mitigation in soil. Also, carbon-based composites have been increasingly attracting attention, and as a result, some of them have been commercialized [123,124,125]. Ion exchange and reverse osmosis are preferably used for PFAS mitigation in water [115,121]. Phytoremediation is a new technique that uses plant-associated microbes in roots for PFAS absorbance [121].

4.2. Destruction Technology

4.2.1. Biodegradation

Based on previous studies, it was initially found that PFOA was more susceptible to biodegradation [126,127] (Table 8). The mechanism of biodegradation is usually studied by its decomposition products. In PFOA, shorter-chained PFCA species were detectable. This raises the possibility of the elimination of CO2, followed by the formation of carboxylic acid (reviewed in [128]). Aerobic bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, Delftia acidovorans, and Acidimicrobium sp. strain A6, were well-studied cases for PFAS biodegradation. More recently, PFOS-degrading enzymes in soil were subsequently identified in multiple cases, suggesting a consistent outcome that PFOS-degrading products were also found in a non-target study.

Table 8.

Degradation of PFAS by biological and chemical procedures.

4.2.2. Chemical Degradation

Photocatalysis

In contrast, PFOS degradation has been studied based on chemical degradation, including photo-oxidation and electro-oxidation, as the major chemical reactions [136,137] (Table 8). These reactions convert CF2-SO3− to a C-centered radical by eliminating SO3− by reduction, followed by the formation of a short-chained C-centered radical under anaerobic oxidation [138,139]. The Fenton reaction and ammonium persulfate-mediated oxidation were well studied for PFOS degradation. Under aerobic conditions, the termination of peroxyl radicals results in the generation of alkoxyl radicals and molecular oxygen, followed by the formation of alcohol. In fact, this reaction might apply to PFOA; in this case, the elimination of carbon dioxide occurs as a product of the initial reaction.

FTCA, fluorotelomer carboxylic acid; FTS, fluorotelomer sulfonates; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid; UV, ultraviolet.

Plasma-Mediated Degradation

Generation of plasma leads to PFAS degradation in aqueous solution [140]. Activated electrons and free radicals react with PFAS, leading to the decomposition of C-F bonding. This technique is best applicable to water and equivalent clean samples.

Sonolysis

Sonolysis irradiates high-frequency sonic waves into a PFAS-containing solution, generating the formation and decay of fine air bubbles [141]. Under this condition, the PFAS, a surfactant, accumulates at the interface between air and water. In these conditions, C-F bonding of PFAS might be dissociated upon high temperature and free radicals when air bubbles decay. The associated concerns of this method depend on frequency, power, and temperature. Optimization of these parameters is better carried out by AI today.

4.2.3. Emerging Methods: Hybrid Treatments

Hybrid treatment of PFAS degradation usually performs PFAS’ physico-chemical separation/concentration followed by degradation [142]. Physical separation includes membranous separation, absorption, and foam fractionation. Generally, concentration of samples prior to PFAS degradation increases its efficiency, leading to cost reduction. Membranous separation yields a clear solution that can be easily concentrated, leading to a cost-effective destruction process. The adsorption process can be easily combined with the current water purification process in a water purification facility. The foam-mediated phase separation technique applies wastewater, which accumulates highly concentrated foams. Such concentrated foam, then, is going to be degraded by sonolysis as described above.

4.3. Summary of the Latest Policy Frameworks (EU, US EPA) with Implications for Monitoring

4.3.1. EU

The EU aims for a stepwise elimination of PFAS. The European Chemicals Agency is now proposing restricted use of PFAS for industrial application. For drinking water, the upper limit of total PFAS and of 20 PFAS compounds is 500 ng/L and 100 ng/L, respectively [143]. Development of PFAS alternatives and their degradation techniques is currently prioritized.

4.3.2. US EPA

The US EPA regulates PFOA and PFOS concentrations at very low levels (4 ng/L). Similar to the EU, the US EPA also encourages the development of PFAS mitigation procedures. Importantly, the government expresses an intention to ask PFAS-manufacturing companies to pay the cost to obtain PFAS-free water for American citizens.

5. Perspectives

The concentration of legacy PFAS has been regulated in the U.S. and the EU [79]. Tokranov A.K. et al. measured legacy PFAS concentrations in wells and mapped this distribution across U.S. aquifers [79]. These authors demonstrated that this study allowed for the prediction of PFAS levels in each area, providing the possibility of whether any additional remediation might be required. Washington, JW et al. studied chloroperfluoropolyether carboxylates, a series of emerging PFAS in New Jersey, using non-target mass spectrometry [144]. These authors tentatively identified ten compounds, of which nine congeners contained (CF2)7 or a longer chain. It was found that the shorter-chain PFAS were highly detectable in far more distant areas; thus, these authors concluded that shorter-chain PFAS were mainly delivered atmospherically.

Selective detection of PFAS has largely been achieved by conventional chromatography-coupled mass spectrometry. Recently, a variety of sophisticated detection methods have been reported. Ion mobility mass spectrometry allows for the acquisition of the collision cross-section, which depends on the tertiary structure of low-molecular-weight compounds. In other words, a globular compound can be identified separately from a flatter compound by a difference in drift time. Kirkwood-Donelson et al. used this technique on many uncharacterized PFAS-related compounds [145]. Photoionization mass spectrometry, in theory, ionizes an analyte compound to give rise to fluorocarbon radicals. Xu M-G et al. successfully applied this technique for fluorinated compounds to demonstrate the formation of fluorocarbon radicals at high temperatures (400–950 °C). This photoionization technique generates characteristic fragmented ions that will never appear in electrospray and atmospheric pressure ionization [146]. Cyclodextrin-mediated molecular recognition is often used for molecular recognition and is studied for the single-molecule detection of DNA and peptides. Wei X et al. used cyclodextrin-mediated host–guest chemistry for PFAS-profiling at low levels [120]. Apart from the mass spectrometric technique, this nanopore-based PFAS assay is affordable; thus, its expansion into routine PFAS monitoring is highly expected.

Thousands of PFAS, as well as their precursors/metabolites, are known to accumulate and are characterized by non-targeting mass spectrometry. For the rapid identification of uncharacterized compounds, Wang X et al. developed novel machine learning software, characterizing its unreported structure by mass spectral data [147]. These authors originally developed a PFAS_ID module that allows the extraction of highly fluorinated compounds from spectral data. To demonstrate the efficacy of this system, fluorinated compounds were screened in wastewater. As a result, substantial species of unreported PFAS were detected globally in both legacy and emerging PFAS.

6. Conclusions

A large amount of research evidence on both legacy and emerging PFAS has been available now. Individual research goals have been reasonably achieved by many researchers’ efforts. Below is a list of remaining factors to be considered in the future:

- Global method harmonization;

- Precursor-to-product transformation assessment;

- Development of fluorine-free alternatives.

Global method harmonization is always problematic in other research areas, including clinical, forensic, and food chemistry. This could originate from the target PFAS to be regulated. For example, the quantification of which emerging PFAS compounds need to be regulated still needs discussion. EOF provides a good measure for PFAS, while its sensitivity is normally low. Radical-mediated degradation of a PFAS compound leads to a smaller PFAS radical. In this reaction, a variety of small compounds such as PFBA and TFA will be produced. These are volatile compounds that will evaporate into the air. The balance between precursor and product is usually not consistent, because the volatile PFAS are quantified by GC-MS, while LC-MS is used for the measurement of legacy PFAS and their associated degrading compounds. Finally, chemical industries are studying fluorine-free alternatives [148]. The current major area of PFAS consumption includes semiconductors and batteries. Continuous efforts to search for such alternative chemicals are urgently required.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25K11117 to RM.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AFFF | aqueous film-forming foam |

| AOF | absorbable organic fluorine |

| CIC | combustion ion chromatography |

| EOF | extractable organic fluoride |

| F-53B | (2-((6-chloro-1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6-dodecafluorohexyl)oxy)-1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethanesulfonic acid) |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| Gen-X | hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid |

| HFPO-DA | hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid |

| LC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| PFAS | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFCA | perfluorocarboxylic acid |

| PFHxS | perfluorohexane sulfonate |

| PFOS | perfluorooctane sulfonate |

| PFOA | perfluorooctanic acid |

| PFSA | perfluorosulfuric acid |

| Q-TOF | quadrupole time-of-flight |

| QuEChERS | Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe |

| TF | total fluorine |

| TOP | total oxidizable precursor |

| WWTP | wastewater treatment plant |

References

- Evich, M.G.; Davis, M.J.B.; McCord, J.P.; Acrey, B.; Awkerman, J.A.; Knappe, D.R.U.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Speth, T.F.; Tebes-Stevens, C.; Strynar, M.J.; et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment. Science 2022, 375, 9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.C.; Smaoui, S.; Duffill, J.; Marandi, B.; Varzakas, T. Research Progress in Current and Emerging Issues of PFASs’ Global Impact: Long-Term Health Effects and Governance of Food Systems. Foods 2025, 14, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcan, R.X.S.; Yarleque, C.M.H.; Lu, X.; Yeerkenbieke, G.; Herrera, V.O.; Gunarathne, V.; Yánez-Jácome, G.S. Characterization of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Chinese River and Lake Sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, J.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Legacy Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) and Alternatives (Short-Chain Analogues, F-53B, GenX and FC-98) in Residential Soils of China: Present Implications of Replacing Legacy PFASs. Environ. Int. 2020, 135, 105419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghese, M.M.; Feng, J.; Liang, C.L.; Kienapple, N.; Manz, K.E.; Fisher, M.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Atlas, E.; Braun, J.M.; Bouchard, M.F.; et al. Legacy, Alternative, and Precursor PFAS and Associations with Lipids and Liver Function Biomarkers: Results from a Cross-Sectional Analysis of Adult Females in the MIREC-ENDO Study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2025, 267, 114592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liwara, D.J.; Araújo, A.R.L.; Pavlov, A.; Johansen, J.E.; Liu, H.; Koekkoek, J.; Heinzelmann, M.; de Boer, J.; Leonards, P.E.G.; Brandsma, S. Analysis of Legacy PFAS and Potential Precursors in Curtain, Sofa, and Carpet Fabric Samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 993, 180006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jane, L.; Espartero, L.; Yamada, M.; Ford, J.; Owens, G.; Prow, T.; Juhasz, A. Health-Related Toxicity of Emerging per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Comparison to Legacy PFOS and PFOA. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, P.; Xie, X.; Li, J.; An, X.; Liang, Z.; Sun, B.; Wang, C. Shift from Legacy to Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances for Watershed Management along the Coast of China. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouanneau, W.; Léandri-Breton, D.J.; Corbeau, A.; Herzke, D.; Moe, B.; Nikiforov, V.A.; Gabrielsen, G.W.; Chastel, O. A Bad Start in Life? Maternal Transfer of Legacy and Emerging Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances to Eggs in an Arctic Seabird. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6091–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, J.; Guckert, M.; Berger, U.; Fu, Q.; Nödler, K.; Nürenberg, G.; Koschorreck, J.; Schulze, J.; Reemtsma, T. Long Term Trends of Legacy Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), Their Substitutes and Precursors in Archived Wildlife Samples from the German Environmental Specimen Bank. Environ. Int. 2025, 201, 109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; He, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hong, D.; Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, W.; Yang, B.; Huang, X.; Song, S.; et al. Novel and Legacy Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Indoor Dust from Urban, Industrial, and e-Waste Dismantling Areas: The Emergence of PFAS Alternatives in China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, K.H.; Seo, J.I.; Kim, S.M.; Shiea, J.; Yoo, H.H. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Trends in Mass Spectrometric Analysis for Human Biomonitoring and Exposure Patterns from Recent Global Cohort Studies. Environ. Int. 2024, 194, 109117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroski, K.M.; Sapozhnikova, Y. Method Development and Validation for Analysis of 74 Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Food of Animal Origin Using QuEChERSER Method and LC-MS/MS. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1364, 344216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genualdi, S.; Beekman, J.; Carlos, K.; Fisher, C.M.; Young, W.; DeJager, L.; Begley, T. Analysis of Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Processed Foods from FDA’s Total Diet Study. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.B.; Sapozhnikova, Y. Comparison and Validation of the QuEChERSER Mega-Method for Determination of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Foods by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution and Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1230, 340400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniyasu, S.; Yeung, L.W.Y.; Lin, H.; Yamazaki, E.; Eun, H.; Lam, P.K.S.; Yamashita, N. Quality Assurance and Quality Control of Solid Phase Extraction for PFAS in Water and Novel Analytical Techniques for PFAS Analysis. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Feldmann, J.; Prieler, E.; Brodschneider, R. PFAS in the Buzz: Seasonal Biomonitoring with Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera) and Bee-Collected Pollen. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-McDevitt, M.E.; Becanova, J.; Blum, A.; Bruton, T.A.; Vojta, S.; Woodward, M.; Lohmann, R. The Air That We Breathe: Neutral and Volatile PFAS in Indoor Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corviseri, M.C.; Polidoro, A.; De Poli, M.; Stevanin, C.; Chenet, T.; D’Anna, C.; Cavazzini, A.; Pasti, L.; Franchina, F.A. Targeted Determination of Volatile Fluoroalkyl Pollutants and Non-Targeted Screening for Environmental Monitoring. Talanta 2025, 292, 127944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z. Migration Safety of Perfluoroalkyl Substances from Sugarcane Pulp Tableware: Residue Analysis and Takeout Simulation Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, P.; Schinnen, A.; Riedel, M.; Sommerfeld, T.; Sawal, G.; Bandow, N.; Vogel, C.; Kalbe, U.; Simon, F.G. Investigation of PH-Dependent Extraction Methods for PFAS in (Fluoropolymer-Based) Consumer Products: A Comparative Study between Targeted and Sum Parameter Analysis. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, V.; Andrade Costa, L.C.; Rondan, F.S.; Matic, E.; Mesko, M.F.; Kindness, A.; Feldmann, J. Per and Polyfluoroalkylated Substances (PFAS) Target and EOF Analyses in Ski Wax, Snowmelts, and Soil from Skiing Areas. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2023, 25, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioni, L.; Plassmann, M.; Benskin, J.P.; Coêlho, A.C.M.F.; Nøst, T.H.; Rylander, C.; Nikiforov, V.; Sandanger, T.M.; Herzke, D. Fluorine Mass Balance, Including Total Fluorine, Extractable Organic Fluorine, Oxidizable Precursors, and Target Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, in Pooled Human Serum from the Tromsø Population in 1986, 2007, and 2015. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 14849–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S.; Pickard, H.M.; Sunderland, E.M.; Allen, J.G. Organic Fluorine as an Indicator of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Dust from Buildings with Healthier versus Conventional Materials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17090–17099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütz, K.W.; Namazkar, S.; Plassmann, M.; Benskin, J.P. Are Cosmetics a Significant Source of PFAS in Europe? Product Inventories, Chemical Characterization and Emission Estimates. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2022, 24, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetverikov, S.; Hkudaigulov, G.; Sharipov, D.; Starikov, S. Probable New Species of Bacteria of the Genus Pseudomonas Accelerates and Enhances the Destruction of Perfluorocarboxylic Acids. Toxics 2024, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.D.; Coon, C.M.; Doherty, M.E.; McHugh, E.A.; Warner, M.C.; Walters, C.L.; Orahood, O.M.; Loesch, A.E.; Hatfield, D.C.; Sitko, J.C.; et al. Engineering and Characterization of Dehalogenase Enzymes from Delftia Acidovorans in Bioremediation of Perfluorinated Compounds. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, G.; Liu, J.; Duy, S.V.; Sauvé, S. Analysis of F-53B, Gen-X, ADONA, and Emerging Fluoroalkylether Substances in Environmental and Biomonitoring Samples: A Review. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019, 23, e00066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.A.; Cooper, J.; Koh-Fallet, S.E.; Kabadi, S.V. Comparative Analysis of the Physicochemical, Toxicokinetic, and Toxicological Properties of Ether-PFAS. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 422, 115531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.A.; Aungst, J.; Cooper, J.; Bandele, O.; Kabadi, S.V. Comparative Analysis of the Toxicological Databases for 6:2 Fluorotelomer Alcohol (6:2 FTOH) and Perfluorohexanoic Acid (PFHxA). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 138, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Xing, L.; Chu, J. Global Ocean Contamination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: A Review of Seabird Exposure. Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, N.; Junaid, M.; Sultan, M.; Yoganandham, S.T.; Chuan, O.M. The Untold Story of PFAS Alternatives: Insights into the Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Impacts, and Removal Strategies in the Aquatic Environment. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brase, R.A.; Mullin, E.J.; Spink, D.C. Legacy and Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Analytical Techniques, Environmental Fate, and Health Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, K.U.; Hærvig, K.K.; Flachs, E.M.; Bonde, J.P.; Lindh, C.; Hougaard, K.S.; Toft, G.; Ramlau-Hansen, C.H.; Tøttenborg, S.S. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Male Reproductive Function in Young Adulthood; a Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yu, N.; Wang, X.; Shi, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Pan, B.; Yu, H.; Wei, S. Comprehensive Exposure Studies of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the General Population: Target, Nontarget Screening, and Toxicity Prediction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14617–14626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y. On-Line Solid Phase Extraction-Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole/Orbitrap High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Determination of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Serum. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2022, 1212, 123484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, I.G.; Ekpe, O.D.; Megson, D.; Bruce-Vanderpuije, P.; Sandau, C.D. A Systematic Review of Methods for the Analysis of Total Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 967, 178644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, S.F.; Isobe, T.; Iwai-Shimada, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nishihama, Y.; Taniguchi, Y.; Sekiyama, M.; Michikawa, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Nitta, H.; et al. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Maternal Serum: Method Development and Application in Pilot Study of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1618, 460933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; van Hees, P.; Karlsson, P.; Jiao, E.; Filipovic, M.; Lam, P.K.S.; Yeung, L.W.Y. What We Learn from Using Mass Balance Approach and Oxidative Conversion—A Case Study on PFAS Contaminated Soil Samples. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 376, 126420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genualdi, S.; Srigley, C.; Young, W.; De Jager, L. Investigation of Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Isomer Profiles in Naturally Contaminated Food Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 16746–16753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevedouros, K.; Cousins, I.T.; Buck, R.C.; Korzeniowski, S.H. Sources, Fate and Transport of Perfluorocarboxylates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.K.; Mottaghipisheh, J.; Verma, S.; Singh, R.P.; Muthukumaran, S.; Navaratna, D.; Ahrens, L. PFAS Contamination in Key Indian States: A Critical Review of Environmental Impacts, Regulatory Challenges and Predictive Exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Donald, W.A. Assessment of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Sydney Drinking Water. Chemosphere 2025, 385, 144611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); OW. Analysis of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous, Solid, Biosolids, and Tissue Samples by LC-MS/MS; Ost Method 1633, Revision A; The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bangma, J.; Barry, K.M.; Fisher, C.M.; Genualdi, S.; Guillette, T.C.; Huset, C.A.; McCord, J.; Ng, B.; Place, B.J.; Reiner, J.L.; et al. PFAS Ghosts: How to Identify, Evaluate, and Exorcise New and Existing Analytical Interference. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangma, J.; McCord, J.; Giffard, N.; Buckman, K.; Petali, J.; Chen, C.; Amparo, D.; Turpin, B.; Morrison, G.; Strynar, M. Analytical Method Interferences for Perfluoropentanoic Acid (PFPeA) and Perfluorobutanoic Acid (PFBA) in Biological and Environmental Samples. Chemosphere 2023, 315, 137722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateia, M.; Chiang, D.; Cashman, M.; Acheson, C. Total Oxidizable Precursor (TOP) Assay─Best Practices, Capabilities and Limitations for PFAS Site Investigation and Remediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2023, 10, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K.; de Falco, G.; Fernando, E.; Boufadel, M.C.; Zhang, Z.; Sarkar, D. Assessing PFAS and Their Precursor Transformation in a Landfill Leachate-Impacted Wastewater Treatment Plant. Water Environ. Res. 2025, 97, 70172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela, H.; Williams, M.L.; McLeod, C.; Gionfriddo, E. Effective Preconcentration of Volatile Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from Gas and Aqueous Phase via Solid Phase Microextraction. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1345, 343746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Dada, T.K.; Whelan, A.; Cannon, P.; Sheehan, M.; Reeves, L.; Antunes, E. Microbial and Thermal Treatment Techniques for Degradation of PFAS in Biosolids: A Focus on Degradation Mechanisms and Pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, T.; Akhdhar, A.; Mueller, V.; Simon, F.; von der Au, M.; Cossmer, A.; Pfeifer, J.; Krupp, E.M.; Meermann, B.; Kindness, A.; et al. EOF and Target PFAS Analysis in Surface Waters Affected by Sewage Treatment Effluents in Berlin, Germany. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruyle, B.J.; Pennoyer, E.H.; Vojta, S.; Becanova, J.; Islam, M.; Webster, T.F.; Heiger-Bernays, W.; Lohmann, R.; Westerhoff, P.; Schaefer, C.E.; et al. High Organofluorine Concentrations in Municipal Wastewater Affect Downstream Drinking Water Supplies for Millions of Americans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2417156122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, B.G.; Lim, H.J.; Na, S.H.; Choi, B.I.; Shin, D.S.; Chung, S.Y. Biodegradation of Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) as an Emerging Contaminant. Chemosphere 2014, 109, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, M. Enriching Fluorotelomer Carboxylic Acids-Degrading Consortia from Sludges and Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 177823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Lee, M.; O’Carroll, D.; McDonald, J.; Osborne, K.; Khan, S.; Pickford, R.; Coleman, N.; O’Farrell, C.; Richards, S.; et al. Biotransformation of 6:2/4:2 Fluorotelomer Alcohols by Dietzia Aurantiaca J3: Enzymes and Proteomics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.; Holland, S.; Bhardwaj, S.; McDonald, J.; Khan, S.; O’Carroll, D.; Pickford, R.; Richards, S.; O’Farrell, C.; Coleman, N.; et al. Aerobic Biotransformation of 6:2 Fluorotelomer Sulfonate by Dietzia Aurantiaca J3 under Sulfur-Limiting Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne, C.; Bank, M.S.; Jenssen, B.M.; Cieseielski, T.M.; Rinklebe, J.; Lam, S.S.; Hansen, M.; Bossi, R.; Gustavson, K.; Dietz, R. PFAS Pollution Threatens Ecosystems Worldwide. Science 2023, 379, 887–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaymat, T.; Robey, N.; Krause, M.; Larson, J.; Weitz, K.; Parvathikar, S.; Phelps, L.; Linak, W.; Burden, S.; Speth, T.; et al. A Critical Review of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Landfill Disposal in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simones, T.L.; Evans, C.; Goossen, C.P.; Kersbergen, R.; Mallory, E.B.; Genualdi, S.; Young, W.; Smith, A.E. Uptake of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Mixed Forages on Biosolid-Amended Farm Fields. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 23108–23117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.H.; Zuverza-Mena, N.; Dimkpa, C.O.; Nason, S.L.; Thomas, S.; White, J.C. PFAS Remediation in Soil: An Evaluation of Carbon-Based Materials for Contaminant Sequestration. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 344, 123335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joerss, H.; Schramm, T.R.; Sun, L.; Guo, C.; Tang, J.; Ebinghaus, R. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Chinese and German River Water—Point Source- and Country-Specific Fingerprints Including Unknown Precursors. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Sivaram, A.K.; Megharaj, M.; Webb, L.; Adhikari, S.; Thomas, M.; Surapaneni, A.; Moon, E.M.; Milne, N.A. Investigation on Removal of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), Perfluorohexane Sulfonate (PFHxS) Using Water Treatment Sludge and Biochar. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, N.; Yamazaki, E.; Taniyasu, S.; Hanari, N.; Yeung, L.W.Y. Biochar from Paddy Field—A Solution to Reduce PFAS Pollution in the Environment. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.; Patton, H.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Guevara, R.; McCray, J.; Krometis, L.A.; Cohen, A. Microbiological and Chemical Drinking Water Contaminants and Associated Health Outcomes in Rural Appalachia, USA: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahne, H.; Gerstner, D.; Völkel, W.; Schober, W.; Aschenbrenner, B.; Herr, C.; Heinze, S.; Quartucci, C. Human Biomonitoring Follow-up Study on PFOA Contamination and Investigation of Possible Influencing Factors on PFOA Exposure in a German Population Originally Exposed to Emissions from a Fluoropolymer Production Plant. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2024, 259, 114387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yukioka, S.; Tanaka, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Echigo, S.; Kärrman, A.; Fujii, S. A Profile Analysis with Suspect Screening of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Firefighting Foam Impacted Waters in Okinawa, Japan. Water Res. 2020, 184, 116207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Wiggins, S.; Limm, W.; Fisher, C.M.; Dejager, L.; Genualdi, S. Analysis of Per- and Poly(Fluoroalkyl) Substances (PFASs) in Highly Consumed Seafood Products from U.S. Markets. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13545–13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genualdi, S.; Young, W.; Peprah, E.; Srigley, C.; Fisher, C.M.; Ng, B.; deJager, L. Analyte and Matrix Method Extension of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Food and Feed. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbo, N.; Stoiber, T.; Naidenko, O.V.; Andrews, D.Q. Locally Caught Freshwater Fish across the United States Are Likely a Significant Source of Exposure to PFOS and Other Perfluorinated Compounds. Environ. Res. 2023, 220, 115165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, H.L.; Blazer, V.S.; Lord, E.; Hurley, S.T.; LeBlanc, D.R. Occurrence and Tissue Distribution of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Fishes from Waterbodies with Point and Non-Point Sources in Massachusetts, USA. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 287, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aßhoff, N.; Bernsmann, T.; Esselen, M.; Stahl, T. A Sensitive Method for the Determination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Food and Food Contact Material Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1730, 465041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, R.; Hagen, T.G.; Champness, D. Accumulation of PFAS by Livestock–Determination of Transfer Factors from Water to Serum for Cattle and Sheep in Australia. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2021, 38, 1897–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Tuda, H.; Kato, Y.; Kimura, O.; Endo, T.; Harada, K.H.; Koizumi, A.; Haraguchi, K. Levels and Profiles of Long-Chain Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids in Pacific Cod from 14 Sites in the North Pacific Ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Goodrich, J.A.; Costello, E.; Walker, D.I.; Cardenas-Iniguez, C.; Chen, J.C.; Alderete, T.L.; Valvi, D.; Rock, S.; Eckel, S.P.; et al. Examining Disparities in PFAS Plasma Concentrations: Impact of Drinking Water Contamination, Food Access, Proximity to Industrial Facilities and Superfund Sites. Environ. Res. 2025, 264, 120370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hron, L.M.C.; Wöckner, M.; Fuchs, V.; Fembacher, L.; Aschenbrenner, B.; Herr, C.; Schober, W.; Heinze, S.; Völkel, W. Monitoring of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Human Blood Samples Collected in Three Regions with Known PFAS Releases in the Environment and Three Control Regions in South Germany. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 3727–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toms, L.M.L.; Bräunig, J.; Vijayasarathy, S.; Phillips, S.; Hobson, P.; Aylward, L.L.; Kirk, M.D.; Mueller, J.F. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Australia: Current Levels and Estimated Population Reference Values for Selected Compounds. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Nakayama, S.F.; Nishihama, Y.; Isobe, T. Determinants of Plasma Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances during Pregnancy: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, L.; Rakovic, J.; Ekdahl, S.; Kallenborn, R. Environmental Distribution of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) on Svalbard: Local Sources and Long-Range Transport to the Arctic. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokranov, A.K.; Ransom, K.M.; Bexfield, L.M.; Lindsey, B.D.; Watson, E.; Dupuy, D.I.; Stackelberg, P.E.; Fram, M.S.; Voss, S.A.; Kingsbury, J.A.; et al. Predictions of Groundwater PFAS Occurrence at Drinking Water Supply Depths in the United States. Science 2024, 386, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheringer, M. Innovate beyond PFAS. Science 2023, 381, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, Y.; Harada, K.H. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Toxicokinetics, Exposure and Health Risks. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2025, 50, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, S.J.; Smith, D.J.; Scholljegerdes, E.; Ivey, S.; Young, W.; Genualdi, S.; Dejager, L.; Snyder, A.; Esteban, E.; Johnston, J.J. Plasma and Skin Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Levels in Dairy Cattle with Lifetime Exposures to PFAS-Contaminated Drinking Water and Feed. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 15945–15954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.H.; Hitomi, T.; Niisoe, T.; Takanaka, K.; Kamiyama, S.; Watanabe, T.; Moon, C.S.; Yang, H.R.; Hung, N.N.; Koizumi, A. Odd-Numbered Perfluorocarboxylates Predominate over Perfluorooctanoic Acid in Serum Samples from Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleman, S.R.; Li, M.; Fujitani, T.; Harada, K.H. Plasma Eicosapentaenoic Acid, a Biomarker of Fish Consumption, Is Associated with Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acid Exposure in Residents of Kyoto, Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2023, 28, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Koizumi, A.; Saito, N.; Inoue, K.; Yoshinaga, T.; Date, C.; Fujii, S.; Hachiya, N.; Hirosawa, I.; Koda, S.; et al. Historical and Geographical Aspects of the Increasing Perfluorooctanoate and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Contamination in Human Serum in Japan. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, I.; Bonato, T.; Fletcher, T.; Batzella, E.; Canova, C. Estimation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Half-Lives in Human Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintern, G.; Scarlett, A.G.; Gagnon, M.M.; Leeder, J.; Amhet, A.; Lettoof, D.C.; Leshyk, V.O.; Bujak, A.; Bujak, J.; Grice, K. Phytoremediation Potential of Azolla Filiculoides: Uptake and Toxicity of Seven Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) at Environmentally Relevant Water Concentrations. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 2157–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, A.P.; Engel, S.M.; Whitworth, K.W.; Richardson, D.B.; Stuebe, A.M.; Daniels, J.L.; Haug, L.S.; Eggesbø, M.; Becher, G.; Sabaredzovic, A.; et al. Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Lipid Concentrations in Plasma during Pregnancy among Women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Environ. Int. 2014, 62, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.M.; Kotlarz, N.; Knappe, D.R.U.; Lea, C.S.; Collier, D.N.; Richardson, D.B.; Hoppin, J.A. Drinking Water–Associated PFAS and Fluoroethers and Lipid Outcomes in the GenX Exposure Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 97002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Ding, N.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C.A.; Mukherjee, B.; Calafat, A.M.; Park, S.K. Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Lipid Trajectories in Women 45–56 Years of Age: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 087004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, N.; Ding, L. Associations between Serum Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances as Mixtures and Lipid Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study in Jinan. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.W.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.H. Concentrations of Serum Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Lipid Health in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Korean National Environmental Health Survey 2018–2020. Toxics 2025, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Y.N.; Moustafa, J.S.E.S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Tomlinson, M.; Falchi, M.; Menni, C.; Bowyer, R.C.E.; Steves, C.J.; Small, K.S. Longitudinal Association of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) Exposure with Lipid Traits, in a Healthy Unselected Population. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Gade Timmermann, C.A.; Kruse, M.; Nielsen, F.; Vinholt, P.J.; Boding, L.; Heilmann, C.; Mølbak, K. Severity of COVID-19 at Elevated Exposure to Perfluorinated Alkylates. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 0244815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coêlho, A.C.M.; Charles, D.; Nøst, T.H.; Cioni, L.; Huber, S.; Herzke, D.; Rylander, C.; Berg, V.; Sandanger, T.M. Temporal and Cross-Sectional Associations of Serum per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Lipids from 1986 to 2016—The Tromsø Study. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlezinger, J.J.; Bello, A.; Mangano, K.M.; Biswas, K.; Patel, P.P.; Pennoyer, E.H.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Heiger-Bernays, W.J.; Bello, D. Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Circulation in a Canadian Population: Their Association with Serum-Liver Enzyme Biomarkers and Piloting a Novel Method to Reduce Serum-PFAS. Environ. Health 2025, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembek, Z.F.; Lordo, R.A. Influence of Perfluoroalkyl Substances on Occurrence of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.; Jöud, A. Susceptibility to COVID-19 after High Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances from Contaminated Drinking Water: An Ecological Study from Ronneby, Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollister, J.; Caban-Martinez, A.J.; Ellingson, K.D.; Beitel, S.; Fowlkes, A.L.; Lutrick, K.; Tyner, H.L.; Naleway, A.L.; Yoon, S.K.; Gaglani, M.; et al. Serum Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Concentrations and Longitudinal Change in Post-Infection and Post-Vaccination SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Environ. Res. 2023, 239, 117297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catelan, D.; Biggeri, A.; Russo, F.; Gregori, D.; Pitter, G.; Da Re, F.; Fletcher, T.; Canova, C. Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Mortality for COVID-19: A Spatial Ecological Analysis in the Veneto Region (Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, A.; Johansen, I.S.; Tolstrup, M.; Heilmann, C.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Nielsen, F.; Grandjean, P. Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccination in Danish Adults Exposed to Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): The ENFORCE Study. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.K.; Kleinschmidt, S.E.; Andres, K.L.; Reusch, C.N.; Krisko, R.M.; Taiwo, O.A.; Olsen, G.W.; Longnecker, M.P. Antibody Response to COVID-19 Vaccines among Workers with a Wide Range of Exposure to per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Environ. Int. 2022, 169, 107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Lesseur, C.; Chen, L.; Andra, S.S.; Narasimhan, S.; Pulivarthi, D.; Midya, V.; Ma, Y.; Ibroci, E.; Gigase, F.; et al. Cross-Sectional Associations of Maternal PFAS Exposure on SARS-CoV-2 IgG Antibody Levels during Pregnancy. Environ. Res. 2023, 219, 115067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Chen, J.; Kaur, K.; Amreen, B.; Lesseur, C.; Dolios, G.; Andra, S.S.; Narasimhan, S.; Pulivarthi, D.; Midya, V.; et al. High-Dimensional Mediation Analysis to Elucidate the Role of Metabolites in the Association between PFAS Exposure and Reduced SARS-CoV-2 IgG in Pregnancy. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 980, 179520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.B.; Ducatman, A. Perfluoroalkyl Acids Serum Concentrations and Their Relationship to Biomarkers of Renal Failure: Serum and Urine Albumin, Creatinine, and Albumin Creatinine Ratios across the Spectrum of Glomerular Function among US Adults. Environ. Res. 2019, 174, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampson, H.E.; Li, S.; Walker, D.I.; Wang, H.; Jia, Q.; Rock, S.; Costello, E.; Bjornstad, P.; Pyle, L.; Nelson, J.; et al. The Potential Mediating Role of the Gut Microbiome and Metabolites in the Association between PFAS and Kidney Function in Young Adults: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ouyang, C.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Yang, A.; Hu, X. Temporal Trend of Serum Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid among U.S. Adults with or without Comorbidities in NHANES 1999–2018. Toxics 2024, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F.; Fischer, F.C.; Leth, P.M.; Grandjean, P. Occurrence of Major Perfluorinated Alkylate Substances in Human Blood and Target Organs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, F.; Nadal, M.; Navarro-Ortega, A.; Fàbrega, F.; Domingo, J.L.; Barceló, D.; Farré, M. Accumulation of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Tissues. Environ. Int. 2013, 59, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.E.; Hagenbuch, B.; Apte, U.; Corton, J.C.; Fletcher, T.; Lau, C.; Roth, W.L.; Staels, B.; Vega, G.L.; Clewell, H.J.; et al. Why Is Elevation of Serum Cholesterol Associated with Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Humans? A Workshop Report on Potential Mechanisms. Toxicology 2021, 459, 152845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M.; Sun, Q. Associations between Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Exposures and Blood Lipid Levels among Adults—A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 056001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlezinger, J.J.; Gokce, N. Perfluoroalkyl/Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Links to Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 1136–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louisse, J.; Dellafiora, L.; van den Heuvel, J.J.M.W.; Rijkers, D.; Leenders, L.; Dorne, J.L.C.M.; Punt, A.; Russel, F.G.M.; Koenderink, J.B. Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Are Substrates of the Renal Human Organic Anion Transporter 4 (OAT4). Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinete, N.; Hauser-Davis, R.A. Drinking Water Pollutants May Affect the Immune System: Concerns Regarding COVID-19 Health Effects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Cheng, X.; Gunjal, S.J.; Zhang, C. Advancing PFAS Sorbent Design: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Perspectives. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, V.; Bil, W.; Vandebriel, R.; Granum, B.; Luijten, M.; Lindeman, B.; Grandjean, P.; Kaiser, A.-M.; Hauzenberger, I.; Hartmann, C.; et al. Consideration of Pathways for Immunotoxicity of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environ. Health 2023, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanvoravongchai, J.; Laochindawat, M.; Kimura, Y.; Mise, N.; Ichihara, S. Clinical, Histological, Molecular, and Toxicokinetic Renal Outcomes of per-/Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Exposure: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chemosphere 2024, 368, 143745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, T.; Li, X.; Pan, L. Associations between Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Exposure and Renal Function as Well as Poor Prognosis in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2520903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Meng, L.; Ma, D.; Cao, H.; Liang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, G. The Occurrence of PFAS in Human Placenta and Their Binding Abilities to Human Serum Albumin and Organic Anion Transporter 4. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Choudhary, A.; Wang, L.Y.; Yang, L.; Uline, M.J.; Tagliazucchi, M.; Wang, Q.; Bedrov, D.; Liu, C. Single-Molecule Profiling of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances by Cyclodextrin Mediated Host-Guest Interactions within a Biological Nanopore. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.A.; Zhou, J.; Clarke, B.O.; Leung, I.K.H. Enzymatic Degradation of PFAS: Current Status and Ongoing Challenges. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, 202401122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklund, A.; Taj, T.; Dunder, L.; Lind, P.M.; Lind, L.; Salihovic, S. Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Analysis of Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Kidney Function. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, J.T.; Anderson, R.H.; Lang, J.R.; Liles, D.; Matteson, K.; Olechiw, T. Field-Scale Demonstration of PFAS Leachability Following In Situ Soil Stabilization. ACS Omega 2021, 7, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biek, S.K.; Khudur, L.S.; Rigby, L.; Singh, N.; Askeland, M.; Ball, A.S. Assessing the Impact of Immobilisation on the Bioavailability of PFAS to Plants in Contaminated Australian Soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 20330–20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, T.; Jones, R.; Kastury, F.; Juhasz, A.L. Soil Amendments Reduce PFAS Bioaccumulation in Eisenia Fetida Following Exposure to AFFF-Impacted Soil. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 358, 124489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorada, C.M.; Sima, M.W.; Jaffé, P.R. Bacterial Degradation of Perfluoroalkyl Acids. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 88, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omagamre, E.W.; Custer, G.F. Digging Deep: Microbial PFAS-Degradation in Landfill Sediments. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wackett, L.P. Nothing Lasts Forever: Understanding Microbial Biodegradation of Polyfluorinated Compounds and Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; An, Z.; Mei, Y.; Tan, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Dong, Z.; Yang, M.; Wu, J.; Guo, H.; et al. Impact of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Exposure on Renal Dysfunction: Integrating Epidemiological Evidence with Mechanistic Insights. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerád, J.; Horká, P.; Filipová, A.; Kukla, J.; Holubová, K.; Musilová, Z.; Jandová, K.; Frouz, J.; Cajthaml, T. The Driving Factors of Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substance (PFAS) Accumulation in Selected Fish Species: The Influence of Position in River Continuum, Fish Feed Composition, and Pollutant Properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Xin, X.; Hawkins, G.L.; Huang, Q.; Huang, C.H. Occurrence, Fate, and Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Small- and Large-Scale Municipal Wastewater Treatment Facilities in the United States. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 5428–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, V.S.; Walsh, H.L.; Smith, C.R.; Gordon, S.E.; Keplinger, B.J.; Wertz, T.A. Tissue Distribution and Temporal and Spatial Assessment of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus Dolomieu) in the Mid-Atlantic United States. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 59302–59319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, W.; Partington, J.M.; Leung, I.K.H.; Clarke, B.O. Premium Ultra-Trace Analytical Method for Part per Quadrillion (Ppq) PFAS Quantification in Drinking Water. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1368, 344333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ekpe, O.D.; Macha, F.J.; Sim, W.; Kim, M.G.; Lee, M.; Oh, J.E. Occurrence and Distribution of Brominated and Fluorinated Persistent Organic Pollutants in Surface Sediments Focusing on Industrially Affected Rivers. Chemosphere 2025, 371, 144066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sharkey, M.; Coggins, A.M.; Stubbings, W.; Healy, M.G.; Harrad, S. Concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Sediments and Wastewater Treatment Plant-Derived Biosolids from Ireland. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 979, 179380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banayan Esfahani, E.; Asadi Zeidabadi, F.; Jafarikojour, M.; Mohseni, M. Photo-Reductive Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Its Common Alternatives by UV/VUV/Sulfite Process: Mechanism, Kinetic Modeling, and Water Matrix Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Leng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, F.; Wang, H. A Review of Electrooxidation Systems Treatment of Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Electrooxidation Degradation Mechanisms and Electrode Materials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 42593–42613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yang, Q.; Chen, F.; Sun, J.; Luo, K.; Yao, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Zeng, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Water: A Critical Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 328, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabaso, N.S.N.; Tshangana, C.S.; Muleja, A.A. Efficient Removal of PFASs Using Photocatalysis, Membrane Separation and Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors. Membranes 2024, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanugo, V.S.; Ojo, B.S.; Lin, T.C.; Huang, Y.W.; Locmelis, M.; Han, D. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Degradation in Water and Soil Using Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP): A Review. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2025, 5, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidnell, T.; Wood, R.J.; Hurst, J.; Lee, J.; Bussemaker, M.J. Sonolysis of Per- and Poly Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Meta-Analysis. Ultrason. Sonochem 2022, 87, 105944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Ronen, A. A Review on Removal and Destruction of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) by Novel Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grung, M.; Hjermann, D.; Rundberget, T.; Bæk, K.; Thomsen, C.; Knutsen, H.K.; Haug, L.S. Low Levels of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Detected in Drinking Water in Norway, but Elevated Concentrations Found near Known Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington, J.W.; Rosal, C.G.; McCord, J.P.; Strynar, M.J.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Bergman, E.L.; Goodrow, S.M.; Tadesse, H.K.; Pilant, A.N.; Washington, B.J.; et al. Nontargeted Mass-Spectral Detection of Chloroperfluoropolyether Carboxylates in New Jersey Soils. Science 2020, 368, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood-Donelson, K.I.; Dodds, J.N.; Schnetzer, A.; Hall, N.; Baker, E.S. Uncovering Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Nontargeted Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry Analyses. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadj7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.G.; Huang, C.; Zhao, L.; Rappé, A.K.; Kennedy, E.M.; Stockenhuber, M.; Mackie, J.C.; Weber, N.H.; Lucas, J.A.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Direct Measurement of Fluorocarbon Radicals in the Thermal Destruction of Perfluorohexanoic Acid Using Photoionization Mass Spectrometry. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, ADT3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, N.; Jiao, Z.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; Wei, S. Machine Learning-Enhanced Molecular Network Reveals Global Exposure to Hundreds of Unknown PFAS. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, ADN1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]