Abstract

Ladle furnace (LF) refining is one of the most widely used secondary refining processes for producing clean steel and constitutes a key process in the steelmaking–continuous casting section. The properties of slag play a decisive role in determining molten steel quality and refining efficiency. In this study, based on the composition of refining slag from a steelmaking plant in China, the properties of a CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system were investigated with respect to five aspects, the liquid phase region, sulphide capacity, melting properties, slag viscosity, and mineralogical phase precipitation, at varying temperatures, basicity, w(MgO) and w(Al2O3) using FactSage and the KTH model. Analysis of the slag properties indicates that the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system performs better when basicity ranges from 3 to 4, w(MgO) is between 6% and 8%, and w(Al2O3) is 15%–25%. These findings provide theoretical support and guidance for optimizing the refining slag system in plant trials.

1. Introduction

In the ladle furnace (LF) refining process, slag plays a crucial role in deep deoxidization, deep desulfurization, submerged arc operation, absorption of inclusions, prevention of secondary oxidation of molten steel, and heat preservation of molten steel, thereby determining the high efficiency and stability of ladle furnace operations [1,2,3]. Numerous slag properties have been investigated by many researchers [4,5,6]. Kim et al. [7] investigated the effect of Al2O3 and CaO/SiO2 on the viscosity of the CaO-SiO2-10 mass pct MgO-Al2O3 slags at fully liquid temperatures of 1773 K (1500 °C) and below. Yao et al. [8] studied the effects of Al2O3, MgO, and CaO/SiO2 on the viscosity of high-alumina blast furnace slag at 1773 K (1500 °C) and below using the orthogonal experimental design method. Kim et al. [9] investigated the effect of MgO on the viscosity of CaO-SiO2-20%Al2O3-MgO slags at elevated temperatures by measuring the slag system’s viscosity.

Desulfurization plays a crucial role in the LF refining process. To quantify the desulfurization capacity of slag, Fincham and Richardson [10] proposed the concept of sulphide capacity (CS). Many CS calculation models have been developed by metallurgists, among which optical basicity [11] and the KTH model [12] have been widely used for calculating the CS of slag. Sosinsky et al. [13] investigated the relationship between CS and optical basicity. Young et al. [11] optimized the CS calculation model based on that of Sosinsky et al. Nzotta et al. [14] experimentally determined the CS under different slag systems by means of experimental determination and developed the KTH model. The main idea of the KTH sulphide capacity model is to combine thermodynamic parameters with experimental data analysis to achieve an accurate prediction of sulphide capacity. According to Refs. [15,16,17], the CS values calculated using the KTH model developed by the KTH Royal Institute of Technology (Stockholm, Sweden) are close to the actual values. However, most studies have focused on a single property, while few have systematically investigated the liquid phase region of slag, melting behaviour, and mineralogical phase precipitation. Due to time-consuming and costly high-temperature experiments, an experimental simulation was adopted in this study. FactSage [18,19,20,21] has been successfully used to calculate the thermodynamic data of metallurgical melts, providing valuable guidance for laboratory experimental design and plant trials. This approach not only achieves reliable experimental results but also reduces the experimental cost and risk.

In this study, based on the actual slag conditions at a steelmaking plant in China, the effect of basicity, MgO, and Al2O3 on the metallurgical properties of slag were investigated using FactSage, Photoshop, and the KTH model. Meanwhile, the precipitation behaviour of slag was simulated. Based on the simulation results, the effects of different factors on slag properties were further analyzed, providing theoretical guidance for the optimization of the slag system.

2. Calculation Methods

2.1. Slag Composition

Based on the composition of refining slag from a steelmaking plant in China, the basicity was designed to vary from 2.0 to 4.5 at 0.5 intervals. The MgO content was designed to vary from 0 to 10% at 2% intervals. The Al2O3 content was designed to vary from 10% to 35% at 5% intervals, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of refining slag.

2.2. Liquid Phase Region and Melting Properties

The effects of MgO and Al2O3 on the liquid phase region of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system were calculated using the Phase module of the FactSage7.1 software, and the interface of the software is shown in Figure 1. The calculation steps are as follows:

Figure 1.

Interface of the FactSage7.1 software.

Step 1: Select “FToxide” from the FactSage7.1 database and enter the components (CaO, SiO2, MgO, and Al2O3).

Step 2: Select “Solution Phases” by clicking the “Select” button and selecting all solution phases retrieved from the database.

Step 3: Set the parameters. The temperature ranges from 1300 °C to 1600 °C in increments of 100 °C. The MgO content ranges from 0 to 10% in increments of 2%. The Al2O3 content ranges from 10% to 35% in increments of 5%.

The effects of basicity, MgO, and Al2O3 on the melting properties and viscosity of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system were calculated using the Equilib module and the Viscosity model of the FactSage7.1 software. The calculation steps are as follows:

Step 1: Select “FToxide” from the FactSage7.1 database; enter the CaO, SiO2, MgO, and Al2O3 components; and input their contents according to Table 1.

Step 2: Select “Solids” by clicking the “Select” button and selecting all possible solution phases retrieved from the database.

Step 3: If “IF” is selected from Ftoxid-Slag, the initial melting temperature of the slag will be calculated. If “IP” is chosen, the complete melting temperature will be calculated. The initial melting temperature refers to the temperature at which the liquid phase begins to form from the solid phase. The complete melting temperature refers to the temperature at which all solid phases in the system are completely transformed into the liquid phase.

2.3. Viscosity and Mineralogical Phase Precipitation

The viscosity calculation steps are as follows:

Step 1: Select “Melts” from the FactSage7.1 database.

Step 2: Enter the CaO, SiO2, MgO, and Al2O3 components; input their contents according to Table 1; and input the temperature.

Step 3: Use the Equilib module to determine whether the slag is completely in the liquid phase at the set temperature. If the slag is completely in the liquid phase, the viscosity is calculated using the Viscosity module. If not, the viscosity calculated using the Viscosity module is corrected using the Einstein–Roscoe equation [22,23], as shown in Equation (1).

Viscosity(solid+liquid mixture) ≈ Viscosity(liquid)(1 − solid fraction)−2.5

The Sheil–Gulliver cooling method of the Equilib module was used to calculate mineralogical phase precipitation. The calculation steps are as follows:

Step 1: Select “FToxid” from the FactSage 7.1 database; enter the CaO, SiO2, MgO, and Al2O3 components; and input their contents according to Table 1.

Step 2: Set the temperature to 1600 °C to start cooling.

Step 3: Calculate the composition, precipitation temperature, and maximum precipitation amount of mineralogical phase precipitation using the Sheil–Gulliver cooling method.

2.4. Sulphide Capacity

The effects of basicity, MgO, and Al2O3 on the Cs of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system were calculated using the KTH model.

The definition of CS is as shown in Equation (2) [24].

where K is the equilibrium constant, is the activity of ionic oxygen in slag, is the activity of ionic sulphur in slag, (%S) is the weight percent of the sulphur content in slag, is the partial pressure of oxygen gas, and is the partial pressure of sulphur gas. Based on the definition of sulphide capacity in Equation (2), the calculation of sulphide capacity in the KTH model is expressed as (Equation (3)) [14].

where is the Gibbs energy (J/mol) and R is the gas constant, 8.314 J/mol·K. In the multi-component system, is a function of the component and temperature, as shown in Equation (4).

where i is a component, Xi is the mole fraction of each component i in the multi-component system, is a linear change in the interaction between the different components, and is the mixed interaction coefficient between components.

The calculation parameters of are primarily obtained from Ref. [25]. The calculation of CS is not the focus of this study; therefore, detailed calculation procedures are not discussed here.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Chemical Composition on the Liquid Phase Region

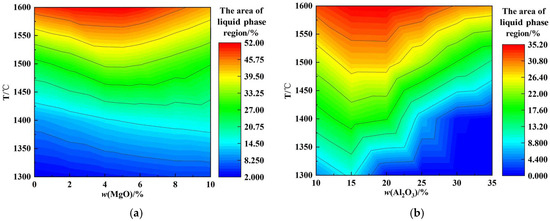

Figure 2a shows the effects of w(MgO) and temperature on the liquid phase region of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slags. It is evident from Figure 2a that at fixed MgO values, the area of the liquid phase region increases with increasing temperature. Within the temperature range of 1300 °C to 1400 °C, the area of the liquid phase region increases. In the temperature range of 1500 °C–1600 °C, the area of the liquid phase region first increases and then decreases with increasing w(MgO) content, reaching a maximum at approximately 5% w(MgO). As w(MgO) increases, the proportion of free oxygen ions increases, modifying the aluminum–oxygen complex ionic clusters, , into small units that form low-melting-point compounds, thereby increasing the area of the liquid phase region. When w(MgO) further increases beyond its saturation percentage, the high-melting-point single-phase MgO solid solution grows, leading to a reduction in the liquid phase region [26,27].

Figure 2.

Effect of w(MgO) and w(Al2O3) on the liquid phase region (1300 °C–1600 °C): (a) w(MgO); (b) w(Al2O3).

Figure 2b shows the effects of w(Al2O3) and temperature on the liquid phase region of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slags. It is evident from Figure 2b that at fixed Al2O3 values, the area of the liquid phase region increases with increasing temperature. Within the temperature range of 1300 °C to 1400 °C, the area of the liquid phase region first increases and then decreases with increasing w(Al2O3) content, reaching a maximum at approximately 15% w(Al2O3). Similarly, in the range of 1500 °C to 1600 °C, the area of the liquid phase region first increases and then decreases as w(Al2O3) increases, reaching a maximum near 20% w(Al2O3). As w(Al2O3) increases, the maximum precipitation of high-melting-point single-phase solid solutions of MgO and CaO decreases, and the precipitation of high-melting-point silicates decreases, while the precipitation of low-melting-point aluminates increases, collectively expanding the liquid phase region. However, when w(Al2O3) exceeds a certain threshold, Ca3Al2O6 is transformed into CaAl2O4, and magnesium aluminum spinel forms, resulting in a reduction in the liquid phase region.

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of w(MgO) and w(Al2O3) on the liquid phase region of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slags. Figure 3a illustrates the liquid phase regions of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system with w(MgO) = 0, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, respectively. Figure 3b shows the corresponding liquid phase regions of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system with w(Al2O3) = 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, and 35%, respectively. As shown in Figure 3a, at 1600 °C and fixed w(MgO) values of 0, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, the CaO content at the boundary between the liquid-phase and non-liquid-phase zones—located near the lower part of the CaO-SiO2 axis—is approximately 56.8%, 56.0%, 55.4%, 55.1%, 54.7%, and 54.5%, respectively. The CaO content at this boundary decreases with increasing w(MgO) content. Figure 3b shows that the CaO content at the boundary between the liquid-phase and non-liquid-phase zones increases with increasing w(Al2O3) content [28].

Figure 3.

Effect of w(MgO) and w(Al2O3) on the liquid phase region (1600 °C): (a) w(MgO); (b) w(Al2O3).

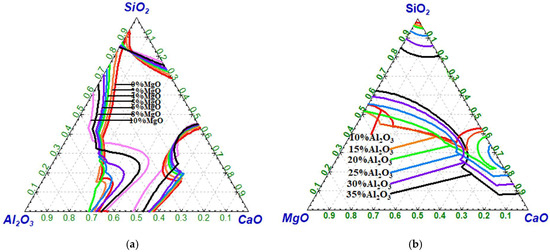

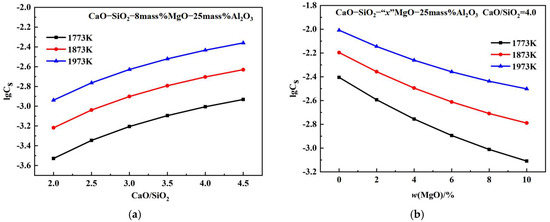

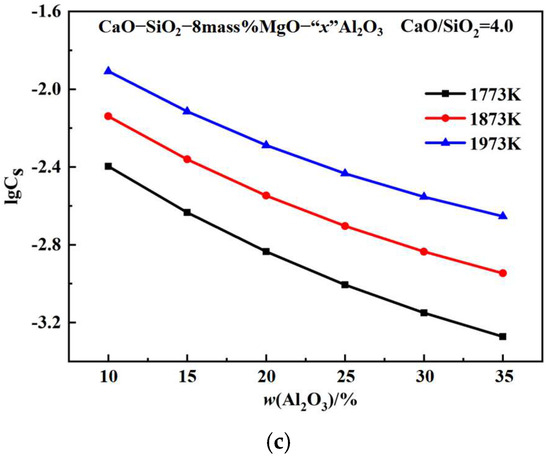

3.2. Effects of Chemical Composition on the CS

Figure 4a shows the CS of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slags with a w(MgO) value of 8% and a w(Al2O3) of 25% at temperatures of 1773 K, 1873 K, and 1973 K, plotted as a function of basicity. At fixed 8% MgO, 25% Al2O3, and temperatures, the sulphide capacity increases with increasing basicity. At a fixed slag composition, the sulphide capacity increases with increasing temperature. As the w(CaO) increases, the SiO2 networks simplify into smaller anion groups, and the proportion of free oxygen ions increases, increasing the sulphide capacity [29]. Figure 4b shows the effect of w(MgO) on the CS of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slags with 25% Al2O3 and CaO/SiO2 at a ratio of 4.0. The sulphide capacity decreases with increasing w(MgO) content. The equilibrium constant for the reaction between CaO and S2 is higher than that between MgO and S2. As w(MgO) increases, CaO is partially replaced by MgO, reducing the saturation solubility of CaO and thus decreasing the CS [30]. Figure 4c shows the effect of w(Al2O3) on the CS of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slags with 8% MgO and CaO/SiO2 at a ratio of 4.0. The sulphide capacity decrease with increasing w(Al2O3) content. Al2O3 is an amphoteric oxide that readily combines with free oxygen ions to form aluminum–oxygen composite ions in basic slag, thereby reducing free oxygen ions and decreasing the CS [31].

Figure 4.

Effects of basicity, w(MgO), and w(Al2O3) on the sulphide capacity: (a) basicity; (b) w(MgO); (c) w(Al2O3).

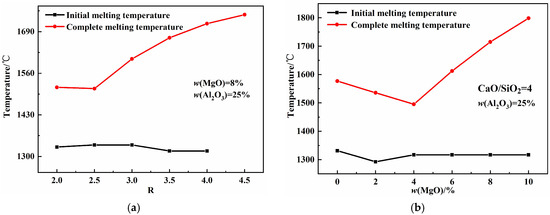

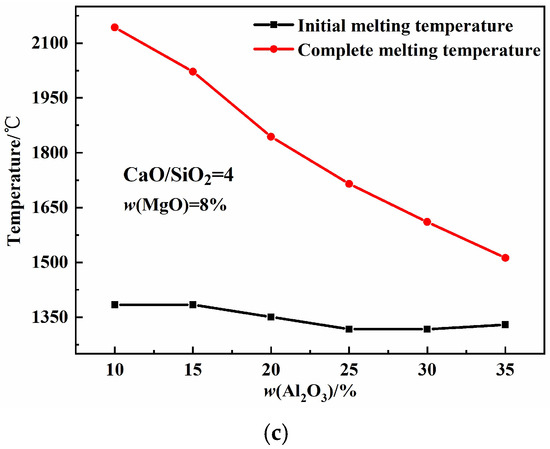

3.3. Effects of Chemical Composition on the Melting Properties

Figure 5 illustrates the effects of basicity, w(MgO), and w(Al2O3) on the melting properties of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system. As shown in Figure 5a, the initial melting temperature first increases and then decreases with increasing basicity, while the complete melting temperature increases. The increase in basicity promotes the formation of high-melting-point single-phase CaO solid solutions, leading to the rise in complete melting temperature. Figure 5b shows that both the initial and complete melting temperatures first decrease and then increase with increasing w(MgO) content. As the w(MgO) values increase, the proportion of free oxygen ions increases, and the aluminum–oxygen complex ionic clusters break down into smaller units, forming low-melting-point compounds that reduce the complete melting temperature. When w(MgO) exceeds its saturation percentage, the high-melting-point single-phase MgO solid solution increases, causing the complete melting temperature to rise [26,27]. Figure 5c shows that the initial melting temperature first decreases and then increases with increasing w(Al2O3), whereas the complete melting temperature decreases continuously. Mineralogical phase precipitation indicates that increasing the w(Al2O3) content reduces the maximum precipitation of high-melting-point single-phase MgO and CaO solid solutions, as well as high-melting-point silicates, while increasing the precipitation of low-melting-point aluminates, collectively lowering the complete melting temperature.

Figure 5.

Effects of basicity, w(MgO), and w(Al2O3) on melting properties: (a) basicity; (b) w(MgO); (c) w(Al2O3).

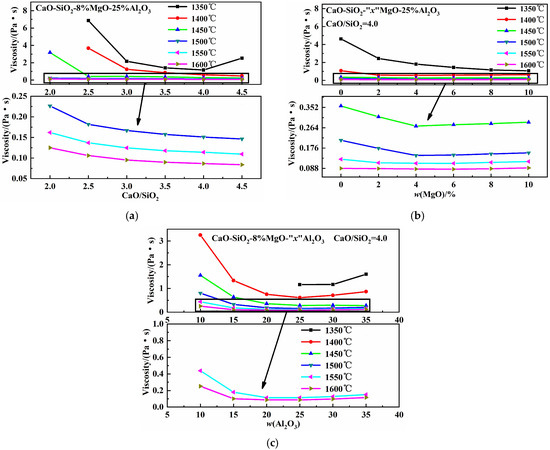

3.4. Effects of Chemical Composition on Viscosity

Figure 6 illustrates the effects of basicity, w(MgO), and w(Al2O3) on the viscosity of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system. As shown in Figure 6a, at 1350 °C, viscosity first decreases and then increases with increasing basicity, reaching a minimum at a basicity value of four. When basicity increases to a certain degree, the high-melting-point compounds form and the inhomogeneous phase content increases, causing viscosity to rise [32]. Between 1400 °C and 1600 °C, the slag’s viscosity decreases with increasing basicity. According to the ionic structure theory of liquid metallurgical slags [33], increasing basicity raises w(CaO), the proportion of free oxygen ions (O2−), and the O/Si ratio. This simplifies complex silicon–oxygen composite anions into simpler ones, reducing viscosity. Figure 6b shows that at 1350 °C, viscosity decreases with increasing w(MgO) content. Between 1400 °C and 1500 °C, viscosity first decreases and then increases with increasing w(MgO) content, reaching a minimum at 4% w(MgO). Between 1550 °C and 1600 °C, a similar trend is observed, with viscosity minimizing at 6% w(MgO). MgO, as a basic oxide, supplies free oxygen ions. Increasing w(MgO) raises the free oxygen ion content and breaks down aluminum–oxygen complex ionic clusters, , into smaller units, forming low-melting-point compounds and reducing viscosity [26]. Further increases in w(MgO) promote the formation of high-melting-point MgO single-phase solid solutions, leading to higher viscosity [27,34]. According to production experience at a Chinese steelmaking plant, slag causes minimal refractory erosion when w(MgO) is around 8%. Figure 6c shows that between 1400 °C and 1600 °C, viscosity first decreases and then increases with increasing w(Al2O3) content, reaching a minimum at 25% w(Al2O3). As the w(Al2O3) content increases, it promotes the transformation of high-melting 2CaO·SiO2 into low-melting calcium alumina feldspar [35]. When w(Al2O3) exceeds 25%, abundant complex aluminum–oxygen composite anions form, and mineralogical phase precipitation indicates that Ca3Al2O6 transforms into CaAl2O4, causing viscosity to increase [26].

Figure 6.

Effects of basicity, w(MgO), and w(Al2O3) on viscosity: (a) basicity; (b) w(MgO); (c) w(Al2O3).

3.5. Effects of Chemical Composition on Mineralogical Phase Precipitation

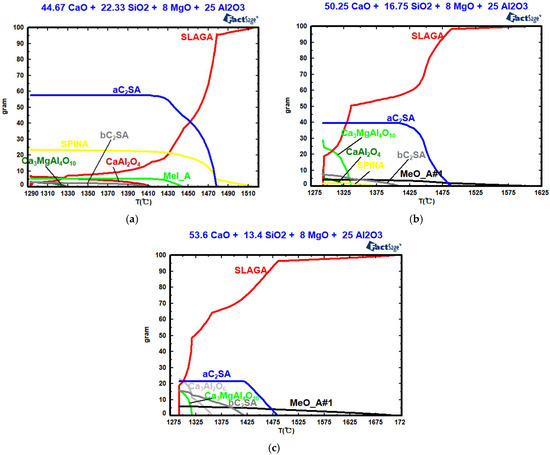

Figure 7, Table 2 and Table 3 show the effects of basicity on mineral composition, the crystal phase’s precipitation temperature, and the amount of crystal phase precipitation. As shown in Figure 7, when the basicity values are two, three, and four, the silicate (a-Ca2SiO4) begins to precipitate at 1478 °C, 1488 °C, and 1485 °C, respectively. With increasing basicity, the precipitation temperature first increases and then decreases, while the maximum precipitation decreases. When the basicity values are two, three, and four, the CaO and MgO solid solution (MeO_A#1) begins to precipitate at 1445 °C, 1605 °C, and 1715 °C, respectively. Increasing basicity raises the precipitation temperature of MeO_A#1, while the maximum precipitation of MeO_A#1 first decreases and then increases. When the basicity values are two and three, the magnesium aluminate spinel (SPINA) begins to precipitate at 1516 °C and 1376 °C. With increasing basicity, the precipitation temperature increases, whereas the maximum precipitation decreases. When the basicity values are two, three, and four, the silicate (b-Ca2SiO4) begins to precipitate at 1413 °C, 1410 °C, and 1419 °C, respectively. With increasing basicity, the maximum precipitation of silicate increases. When the basicity values are two and three, the calcium–aluminum spinel (CaAl2O4) begins to precipitate at 1413 °C and 1326 °C. When the basicity value is four, tricalcium aluminate (Ca3Al2O6) begins to precipitate at 1357 °C. When the basicity values are two, three, and four, the Ca3MgAl4O10 begins to precipitate at 1330 °C, 1336 °C, and 1317 °C, respectively. When the basicity value increases from 2 to 3, CaAl2O4 begins to precipitate, and its maximum precipitation increases. At a basicity value of four, Ca3Al2O6 begins to precipitate. With increasing basicity, the precipitation temperature and the maximum precipitation of Ca3MgAl4O10 first increase and then decrease; meanwhile, the maximum precipitation of silicates decreases, and the maximum precipitation of aluminate increases. The solidification endpoint of the CaO-SiO2-8% MgO-25% Al2O3 slag system remains constant at 1293 °C across various basicity values.

Figure 7.

Effects of basicity on the mineral composition: (a) R = 2; (b) R = 3; (c) R = 4.

Table 2.

Effect of basicity on the precipitation temperature of the crystal phase (°C).

Table 3.

Effect of basicity on crystal phase precipitation (%).

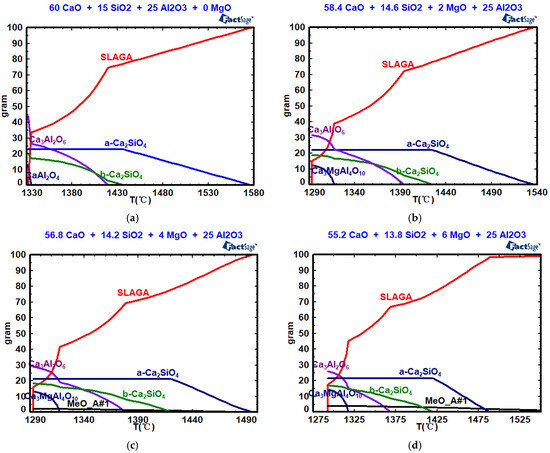

Figure 8, Table 4 and Table 5 show the effects of w(MgO) on mineral composition, the precipitation temperature of the crystal phase, and the amount of crystal phase precipitation. As shown in Figure 8, when the w(MgO) values are 0, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, the silicate (a-Ca2SiO4) begin to precipitate at 1577 °C, 1536 °C, 1495 °C, 1488 °C, 1485 °C, and 1481 °C, respectively. With increasing w(MgO) content, both the precipitation temperature and the maximum precipitation decrease. When the w(MgO) values are 0, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, the silicate (b-Ca2SiO4) begin to precipitate at 1437 °C, 1425 °C, 1420 °C, 1420 °C, 1419 °C, and 1418 °C, respectively. With increasing w(MgO) content, both the precipitation temperature and the maximum precipitation decrease. When the w(MgO) values are 0, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, tricalcium aluminate (Ca3Al2O6) begins to precipitate at 1419 °C, 1393 °C, 1378 °C, 1368 °C, 1357 °C, and 1344 °C, respectively. With increasing w(MgO) content, both the precipitation temperature and the maximum precipitation of tricalcium aluminate decrease. When the w(MgO) values are 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, Ca3MgAl4O10 begins to precipitate at 1317 °C. Increasing the w(MgO) content does not affect the precipitation temperature, but it increases the maximum precipitation of Ca3MgAl4O10. The solidification endpoint of the CaO-SiO2-Al2O3 slag system is 1332 °C. For the CaO-SiO2-“x” MgO-25% Al2O3 slag system, the solidification endpoint remains at 1293 °C, regardless of the w(MgO) content. The content of the high-melting-point MgO single-phase solid solution increases from 1.92% to 7.52% as w(MgO) increases from 4% to 10%, resulting in an increase in viscosity.

Figure 8.

Effects of w(MgO) on the mineral composition: (a) w(MgO) = 0; (b) w(MgO) = 2%; (c) w(MgO) = 4%; (d) w(MgO) = 6%; (e) w(MgO) = 8%; (f) w(MgO) = 10%.

Table 4.

Effect of w(MgO) content on the precipitation temperature of the crystal phase (°C).

Table 5.

Effect of w(MgO) on crystal phase precipitation (%).

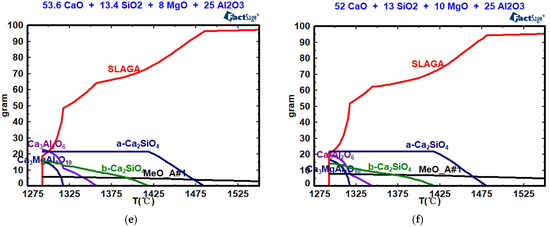

Figure 9, Table 6 and Table 7 show the effects of w(Al2O3) on the mineral composition, the precipitation temperature of the crystal phase, and the amount of crystal phase precipitation. In Figure 9, as w(Al2O3) increases, the precipitation temperature and maximum precipitations of the solid solutions (MeO_A#1 and MeO_A#2) and silicates decrease during slag cooling, significantly enhancing slag fluidity. With increasing w(Al2O3) content, the precipitation temperature of tricalcium aluminate (Ca3Al2O6) decreases, while its maximum precipitation increases. However, with increasing w(Al2O3) content, the precipitation temperature and the maximum precipitation of CaAl2O4 and Ca3MgAl4O10 increase. Ca3Al2O6 begins to precipitate, and its maximum precipitation increases as w(Al2O3) increases from 10% to 25%. When w(Al2O3) exceed 25%, Ca3Al2O6 transforms into CaAl2O4. In actual production, an appropriate w(Al2O3) value promotes the formation of a low-melting-point phase, thereby reducing the slag melting point and viscosity [36]. The solidification endpoint of the CaO-SiO2-8%MgO-“x” Al2O3 slag system remains at 1293 °C across different w(Al2O3) values. In future work, high-temperature experiments and plant trials will be conducted to further validate the results.

Figure 9.

Effects of w(Al2O3) on the mineral composition: (a) w(Al2O3) = 10%; (b) w(Al2O3) = 15%; (c) w(Al2O3) = 20%; (d) w(Al2O3) = 25%; (e) w(Al2O3) = 30%; (f) w(Al2O3) = 35%.

Table 6.

Effect of w(Al2O3) on the precipitation temperature of the crystal phase (°C).

Table 7.

Effect of w(Al2O3) on crystal phase precipitation (%).

4. Conclusions

The properties of the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system were evaluated from five aspects: the liquid phase region, sulphide capacity, melting behaviour, viscosity, and mineral phase precipitation.

- (1)

- The liquid phase region (1300 °C–1400 °C) expands with increasing temperature and MgO content. It reaches a maximum at w(Al2O3) = 15% or at w(MgO) = 5% with w(Al2O3) = 20%, then decreases with further additions.

- (2)

- Sulphide capacity decreases with increasing MgO and Al2O3 contents, but this can be mitigated with higher basicity and temperatures. The initial melting temperature is relatively insensitive to composition changes, whereas the complete melting point rises with basicity and decreases with added Al2O3, reaching a minimum at w(MgO) = 4%.

- (3)

- Slag viscosity exhibits a complex dependence on temperature and composition. At 1300 °C–1400 °C, viscosity decreases with increasing MgO content and reaches a minimum at basicity = 4. At 1550 °C–1600 °C, viscosity decreases with increasing basicity and is lowest at w(MgO) = 6%. Across 1400 °C–1600 °C, viscosity is lowest at w(Al2O3) = 25%.

- (4)

- Basicity and oxide contents significantly affect mineral phase precipitation. With increasing basicity, the maximum precipitation of Ca3MgAl4O10 first increases and then decreases. The MgO and Ca3MgAl4O10 solid solution’s contents increase with increasing w(MgO) content. Higher Al2O3 content promotes the precipitation of CaAl2O4 and Ca3MgAl4O10; when w(Al2O3) > 25%, Ca3Al2O6 transforms into CaAl2O4. Overall, optimal slag properties are obtained at basicity = 3–4, w(MgO) = 6%–8%, and w(Al2O3) = 15%–25%, offering theoretical guidance for optimization of the refining slag system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and Q.L.; methodology, Z.X.; software, Z.X.; validation, Z.X. and J.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; data curation, Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, Z.X.; supervision, Q.L.; project administration, Q.L.; funding acquisition, Z.X. and Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, under Grant Number 52374321; the State Key Laboratory of Advanced Metallurgy, University of Science and Technology Beijing, under Grant Number 41625030; and the Youth Science and Technology innovation Fund of Jianlong Group, University of Science and Technology Beijing, under Grant Number 20231235.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kazuyo, M.Y.; Hironari, K.; Tetsuya, N. Recycling effects of residual slag after magnetic separation for phosphorus recovery from hot metal dephosphorization slag. ISIJ Int. 2009, 95, 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. LF Refining Technology; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.M.; Che, J.L.; Zhou, F.; Tan, Y.F.; Li, D.L.; Dang, J.; Chen, C. Assessment of inclusion removal ability in refining slags containing Ce2O3. Crystals 2023, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, N.; Wang, D. Viscosity property and melt structure of CaO-MgO-SiO2-Al2O3-FeO slag system. ISIJ Int. 2019, 59, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, Y.L. Viscosity Measurements of CaO-SiO2-CrO Slag. ISIJ Int. 2018, 58, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, B.; Bai, C. Relationship between structure and viscosity of CaO-SiO2-MgO-30.00 wt-%Al2O3 slag by molecular dynamics simulation with FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2018, 45, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Matsuura, H.; Tsukihashi, F.; Wang, W.L.; Min, D.J.; Sohn, I. Effect of Al2O3 and CaO/SiO2 on the viscosity of calcium-silicate-based slags containing 10 mass pct MgO. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2013, 44, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Ren, S.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, Q.C.; Dong, L.Y.; Yang, J.F.; Liu, J.B. Effect of Al2O3, MgO, and CaO/SiO2 on viscosity of high alumina blast furnace slag. Steel Res. Int. 2016, 87, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, W.H.; Sohn, I.; Min, D.J. The Effect of MgO on the viscosity of the CaO-SiO2-20wt%Al2O3-MgO slag system. Steel Res. Int. 2010, 81, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, C.J.B.; Richardson, F.D. The behavior of Sulphur in silicate and aluminate melts. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1954, 223, 40–62. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.W.; Duffy, J.A.; Hassall, G.J.; Xu, Z. Use of optical basicity concept for determining phosphorus and sulphur slag-metal partition. Ironmak. Steelmak. 1992, 19, 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, A.; Du, S.C. Sulfide Capacity in Ladle Slag at Steelmaking Temperatures. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2015, 46, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar]

- Sosinky, D.J.; Sommerville, I.D. The composition and temperature dependence of the sulfide capacity of metallurgical slags. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1986, 17, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzotta, M.M.; Du, S.C.; Seetharaman, S. Sulphide capacity in some multi component slag system. ISIJ Int. 1998, 38, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margareta, A.; Jonsson, P.G.; Nzotta, M.M. Application of the sulphide capacity concept on high-basicity ladle slags used in bearing-steel production. ISIJ Int. 1999, 39, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.Q.; Li, J.P.; Cheng, S.S.; Liu, K.; Liu, Z. Application of IMCT model and KTH model in S50C steel desulfurization practice. J. Iron Steel Res. 2020, 32, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, D.D.; Zhang, Y.L.; Liu, Q.B.; Wen, X.S. Thermodynamic optimization of the CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-MgO slag system. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2014, 36, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, C.W.; Belisle, E.; Chartrand, P.; Decterov, S.A.; Ende, M.A.V. FactSage thermo-chemical software and databases. Calphad. 2002, 26, 189–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.H.; Van, E.; Marie, A. Computational thermodynamic calculations: FactSage from CALPHAD thermodynamic database to virtual process simulation. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2020, 51, 1851–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.D.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhao, Z.X.; Evans, T.; Zhao, B.J. Phase equilibria studies in the CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO system with CaO/SiO2 ratio of 1.10. ISIJ Int. 2016, 56, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.B.; Bielefeldt, W.V.; Vilela, A.C.F. Efficiency of inclusion absorption by slags during secondary refining of steel. ISIJ Int. 2014, 54, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.M.; Reddy, R.G.; Lv, X.W. Structure based viscosity model for aluminosilicate slag. ISIJ Int. 2019, 59, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.C.; Zhang, J.S.; Lan, M.; Liu, Q. TabPFN-SHAP-based slag viscosity prediction model with high accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2025, 56, 4330–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.C.; Zhang, J.S.; Lin, W.H.; Zhang, J.G.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Cui, J.F.; Liu, Q. Sulphide capacity prediction of CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag system by using regularized extreme learning machine. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2021, 48, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzotta, M.M.; Du, S.C.; Seetharaman, S. A Study of the sulfide capacity of iron-oxide containing. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1999, 30, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, P.G.; Jonsson, L.; Du, S.C. Viscosities of LF slags and their impact on ladle refining. ISIJ Int. 1997, 37, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.F.; Chai, N.; Zhang, J.Y.; Jie, C.; Liu, G.Y.; Zhou, G.Z.; Wang, B. Experimental study on melting properties for CaO-Al2O3-MgO slag system with low-melting-point zone. In Proceedings of the 7th CSM Annual Meeting, Beijing, China, 11 November 2009; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, F.M.; Abulikemu, Y. Analysis on effect of MgO content to the melting point of refinery slag and inclusions in pipeline steel. In Proceedings of the 13th Metallurgical Reaction Engineering Meeting, Beijing, China, 10 August 2009; pp. 586–589. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.D.; Chen, M.; Xu, H.F.; Zhu, J.M.; Wang, G.; Zhao, B.J. Sulphide capacity of CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO system relevant to low MgO blast furnace slags. ISIJ Int. 2016, 56, 2126–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Tang, H.Y.; Sun, K.M.; Wen, D.S. Sulfide capacity model and its application in CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3-FetO slag system. J. Iron Steel Res. 2009, 21, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Lv, Q.; Gao, F.; Li, F.M.; Zhang, S.H. Experimental research on desulphurization capacity of high TiO2 and Al2O3 BF slag. Iron Steel 2008, 43, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Z.C.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Liu, W.X. Fluidity of vanadium-titanium BF slag. J. Iron Steel Res. 2017, 29, 787–791. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.H. Principle of Ferrous Metallurgy; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, X. The Study of Reasonable Slag form of Jinchuan’s Nickel Flash Smelting Process. Ph.D. Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z.F.; Qiao, J.L.; Chen, T. Effect of composition on viscosity of CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-TiO2-MgO-Na2O system slag. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2016, 16, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.L.; Shu, Q.F.; Chou, K. Effect of Al2O3 SiO2 mass ratio on viscosity of CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-CaF2 slag. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2015, 42, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).