Abstract

High denitration efficiency and strong adaptability to flue gas temperature fluctuations are the core properties of the NH3-SCR catalyst. In this study, Fe2O3 modification is used as a means to explore the mechanism of adding Fe2O3 to broaden the temperature range of the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst during the preparation process. The results show that the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibits excellent denitration performance, with a denitration efficiency higher than 90%. The temperature range is from 129 to 390 °C. N2 selectivity and resistance to SO2 and H2O are good, and the denitration performance is significantly improved. When the Fe2O3 content is 6%, it promotes lattice shrinkage of TiO2, improves its dispersion, refines the grain size, and increases the specific surface area of the catalyst. At the same time, Fe2O3 enhances the chemical adsorption of oxygen on the catalyst surface and increases the proportion of low-cost metal ions, thereby promoting electron transfer between active elements, generating more surface reactive oxygen species, increasing the oxygen vacancy content and adsorption sites for NOx and NH3, and significantly improving the redox performance of the catalyst. This effect is particularly conducive to the formation of strong acid sites on the catalyst surface. The NH3-SCR reaction on the surface of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst follows both the L-H and E-R mechanisms, with the L-H mechanism being dominant.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen oxide (NOx) pollution has become one of the main sources of air pollution. Among industrial emissions, those from the power industry account for the largest proportion [1,2]. Excessive NOx in the atmosphere can lead to environmental problems such as acid rain, photochemical smog, eutrophication of water bodies, and the greenhouse effect [3]. The country’s regulations on industrial NOx emissions are becoming increasingly stringent, so environmental protection in metallurgy, building materials, glass, and other industries is under great pressure. The selective catalytic reduction (SCR) method is currently the most widely used flue gas denitration technology for controlling NOx emissions from industrial sources [4]. A more mature catalyst for this method is the V2O5-WO3(MoO3)/TiO2 catalyst, which belongs to the category of medium-temperature catalysts [5]. To avoid sulfur dioxide poisoning, it is placed in the flue gas treatment process after desulfurization and dust removal. Therefore, the flue gas needs to be reheated before denitration, which imposes greater economic pressure on enterprises. Moreover, the vanadium component in the catalyst is toxic, and the recycling and disposal of waste catalysts can easily cause pollution. The application prospects of non-toxic SCR catalysts capable of denitrating at low temperatures are very promising.

Among the many transition metal oxides, MnOx has the advantages of multiple valence states, strong acidity, and low cost, while CeO2 has excellent oxygen storage and release capacity as well as redox performance. Thus, low-temperature SCR denitration catalysts with MnOx and CeO2 as the main active components or additives have become a hot topic in the field of denitration catalysts [6,7]. Liu et al. [8] used the sol–gel method to prepare a series of Mn-Ti oxide catalysts. Through experiments, they found that these catalysts have high low-temperature SCR activity. The excellent low-temperature NH3-SCR activity can be attributed to appropriate structural properties, amorphous manganese oxides with equal proportions of Mn3+/Mn4+, good low-temperature reducibility, and rich surface acid sites. Liu et al. [9] studied the performance of the Mn-Ce-Ti mixed oxide catalyst prepared by the hydrothermal method for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by NH3 in the presence of oxygen. The results show that the Mn-Ce-Ti catalyst has excellent NH3-SCR activity, strong resistance to H2O and SO2, and a wide operating temperature window. On the basis of catalyst characterization, the double redox cycles (Mn4+ + Ce3+, Mn4+ + Ti3+ ↔ Mn3+ + Ce4+, Mn4+ + Ti3+) and the amorphous structure play key roles in the catalytic properties for NOx reduction.

China is one of the countries with the richest iron ore resources in the world. If Fe2O3 is used in combination with other metal oxides for the research and development of denitration catalysts, it can realize the efficient denitration of industrial source flue gas at low cost, which is a catalyst preparation technology route that aligns with China’s national conditions [10]. Many studies have shown that Fe2O3 modification can improve the denitration performance and anti-toxicity performance of SCR catalysts. Shi et al. [11] investigated the effects of iron in the Mn/Ti catalyst system on NH3-SCR activity and the water-induced inactivation. The results show that the addition of iron promotes the dispersion of surface species, improves the valence state of manganese, and enhances the low-temperature activity. Chen et al. [12] prepared a new type of Fe-Mn mixed oxide catalyst, of which the Fe(0.4) MnOx catalyst has the highest catalytic activity. At 120 °C and the airspeed of 30,000 h−1, the NOx conversion rate is 98.8%, and the N2 selectivity is 100%. The characterization results show that there is a strong interaction between iron oxide and manganese oxide, which leads to the formation of the Fe3Mn3O8 phase in the catalyst. The electron transfer between Fen+ and Mnn+ ions may be the reason for the long lifespan of the Fe(0.4) MnOx catalyst. Mu et al. [13] prepared the Fe2O3-MnO2/TiO2 catalyst using an ethylene glycol-assisted impregnation method. The catalyst exhibited excellent low-temperature activity, a low apparent activation energy, and strong resistance to sulfur poisoning. The characterization results indicate that the catalyst has better dispersion, smaller particles, and that Fe is partially doped into the TiO2 lattice, forming a Fe-O-Ti structure. This enhances the electronic induction effect and increases the proportion of surface chemisorbed oxygen. NO oxidation is enhanced through the “fast SCR” process, which is beneficial for low-temperature SCR activity. Zhao et al. [14] studied the low-temperature denitration properties of catalysts with different Fe contents. The results show that Fe4Mn7Ce3, doped with 4 wt% Fe on the basis of Mn7Ce3, has the best DeNOx performance. The doping of Fe makes the oxides evenly distributed on the catalyst surface, promotes the valence state cycle of the catalyst, generates more Mn4+ and Ce3+, and shifts the optimal temperature of DeNOx toward lower temperatures. At the same time, the Lewis acid sites on the catalyst surface are enhanced, which promotes the formation of amides and facilitates the DeNOx reaction. Qiu et al. [15] prepared a Fe-modified Mn-Co-Ce/TiO2-SiO2 catalyst by the impregnation and sulfuric acid methods and evaluated its low-temperature NH3-SCR performance in the presence of SO2 and H2O. The study found that adding Fe to MnCoCe/Ti-Si plays an important role in enhancing the anti-sulfur and anti-water poisoning properties of MnCoCe/Ti-Si. When the optimal MnFeCoCe/Ti-Si catalyst is operated at a reaction temperature of 160 °C, an SO2 concentration of 50 ppm, and an H2O concentration of 100%, the NOx conversion rate is as high as 93%. The interaction between MnOx and FeOx improves the sulfur and water resistance more effectively compared to other bimetallic interactions.

Through previous research and early experimental demonstrations by this group, it is concluded that when MnO2 and CeO2 account for 0.4 and 0.06 of the overall mass of the catalyst, respectively, the denitration performance of the CeO2-MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is relatively superior [16]. When Fe2O3 is used as an active component or additive, it can improve the anti-poisoning and anti-sintering capabilities of the catalyst [17]. Meanwhile, the interaction among Fe, Mn, and Ce is helpful in increasing the number of active sites of the catalyst and improving the dispersion state of the active components on the support [18,19]. In order to clarify the mechanism by which Fe2O3 modification’s influence on the denitration performance of the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, this study employs XRD, BET, XPS, SEM, TEM, H2-TPR, NH3-TPD, and in situ DRIFTS to investigate the effects of Fe2O3 on denitration performance, catalytic material morphology, surface acidity, redox capacity, and the catalytic mechanism during the modification of the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst. This study aims to provide theoretical and technical support for the research, development, and application of rare earth-modified denitration catalysts.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphology and Structure of the Catalysts

2.1.1. XRD, BET Surface Area and Pore Morphology

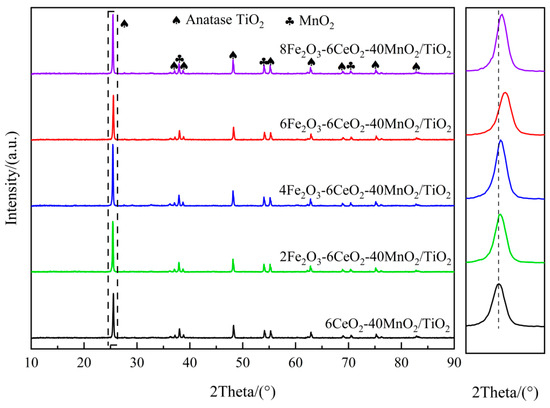

Figure 1 shows the XRD spectrum of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst. It can be seen that there are obvious anatase-type TiO2 and MnO2 diffraction peaks in all catalysts, but no obvious Fe2O3 and CeO2 diffraction peaks appear, indicating that they exist in an amorphous state or are highly dispersed on the surface of the TiO2 support. When the Fe2O3 content increases, the TiO2 diffraction peak at 25.3° shifts gradually to higher angles. Combined with the Bragg equation (), it can be observed that the diffraction angle is inversely proportional to the lattice spacing. Therefore, after the Fe2O3 content increases, the lattice spacing and grain size of TiO2 in the catalyst decrease, and the lattice spacing of TiO2 in the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst decreases the most, indicating that adding an appropriate amount of Fe2O3 can promote the lattice shrinkage of TiO2. This point is also confirmed by the TEM test results presented later. This shrinkage and the resulting decrease in crystallinity increase the overall specific surface area of the catalyst, thereby enhancing the exposure area of the active component and improving the denitration performance of the catalyst.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

The specific surface area and pore structure characteristics of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst were analyzed using the N2 adsorption–desorption measurement method, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specific surface area and pore size parameters of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

Studies have shown that increasing the specific surface area is conducive to improving catalytic performance, and micropores and mesopores can provide a larger inner surface area and pore volume in the SCR reaction [20]. As depicted in Table 1, when the Fe2O3 content increases, the specific surface area and pore capacity of the catalyst increase, while the pore size decreases. The specific surface area and pore capacity of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst increase to 87.73 m2·g−1 and 0.268 cm3·g−1, respectively, and the average pore size decreases to 12.22 nm. Combined with XRD analysis, the increase in Fe2O3 content can inhibit the crystallization and crystal growth of TiO2, improve the overall dispersion of the catalyst, and increase the specific surface area. When the Fe2O3 content continues to increase to 8%, the specific surface area (87.75 m2·g−1) and pore capacity (0.254 cm3·g−1) of the catalyst remain nearly constant.

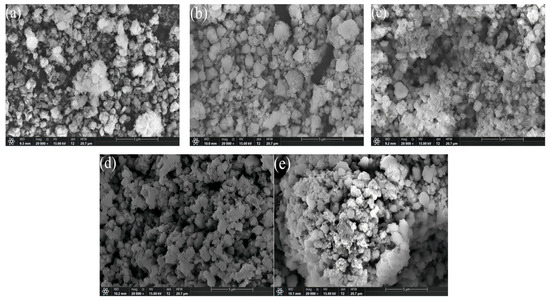

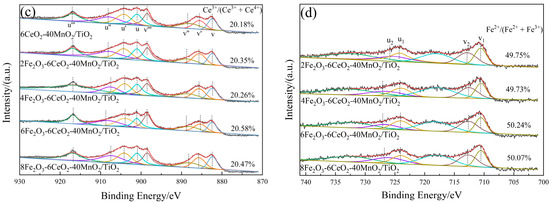

2.1.2. Morphological Analysis

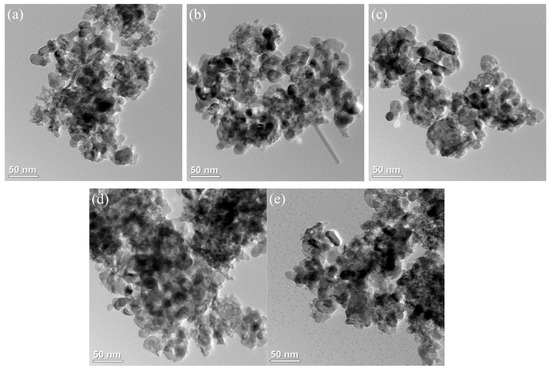

The SEM image of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is shown in Figure 2. It can be observed that the catalyst is mainly composed of particles with uneven sizes, and there are varying degrees of agglomeration. As illustrated in Figure 2a, large and dense aggregates can be clearly observed on the surface of the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst. The active components are encapsulated within these aggregates and cannot participate in the denitration reaction, which negatively affects the catalyst’s denitration performance. With the increase in Fe2O3 content, the surface particles of the catalyst become gradually finer, and the agglomeration and encapsulation phenomena decrease, indicating a relatively better pore structure. In Figure 2d, the surface particles of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibit similar sizes and a uniform distribution. A good pore structure with more micropores can provide a larger contact area for flue gas, thereby facilitating a more thorough removal of NOx during the denitration reaction.

Figure 2.

SEM images of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts. ((a) 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (b) 2Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (c) 4Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (d) 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (e) 8Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2).

The TEM image of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is shown in Figure 3. Most of the catalyst is composed of particles of different sizes, and the dark-colored small particles are generally adsorbed on the surface of the large particles (the TiO2 support) in a loaded state. Figure 3a shows that when the Fe2O3 content is low, the dispersion of the particles on the catalyst surface is poor, and there is a significant agglomeration phenomenon, which is consistent with the results from the SEM image. As the Fe2O3 content increases, the number of active substance particles in the figure gradually increases and becomes more dispersed. In Figure 3d, the surface of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst has the largest number of active substances exposed and is the most evenly distributed, which is conducive to the acid cycle and redox cycle of the NH3-SCR reaction. When the Fe2O3 content continues to increase, the number of active substance particles does not change significantly, but the agglomeration phenomenon becomes more pronounced.

Figure 3.

TEM images of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.((a) 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (b) 2Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (c) 4Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (d) 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (e) 8Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2).

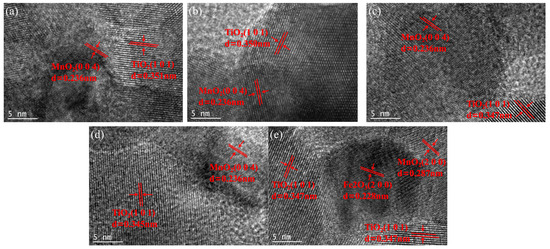

Figure 4 presents a high-resolution lattice stripe image of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst. The lattice stripe spacing of d = 0.351 nm corresponds to the TiO2(101) crystal surface, while the lattice stripe spacings of d = 0.236 nm and d = 0.287 nm correspond to the MnO2(004) and MnO2(200) crystal surfaces, respectively. The lattice stripe spacing of d = 0.228 nm corresponds to the Fe2O3(200) crystal surface. The figure shows that when the Fe2O3 content varies, the lattice stripe spacings corresponding to the MnO2(004) and MnO2(200) crystal surfaces remain almost unchanged. The lattice stripe spacing corresponding to the TiO2(101) crystal surface decreases with increasing Fe2O3 content, indicating that increasing the amount of Fe2O3 added can promote lattice shrinkage of TiO2 and increase the specific surface area of the catalyst, which is consistent with the results of XRD and BET analyses. When the Fe2O3 content increased to 8%, the Fe2O3(200) crystal surface appeared in Figure 4e, indicating that some Fe2O3 was present as dispersed particles on the surface of the TiO2 support at this point.

Figure 4.

Lattice fringe pattern of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts ((a) 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (b) 2Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (c) 4Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (d) 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2; (e) 8Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2).

2.2. Surface Properties of Catalysts

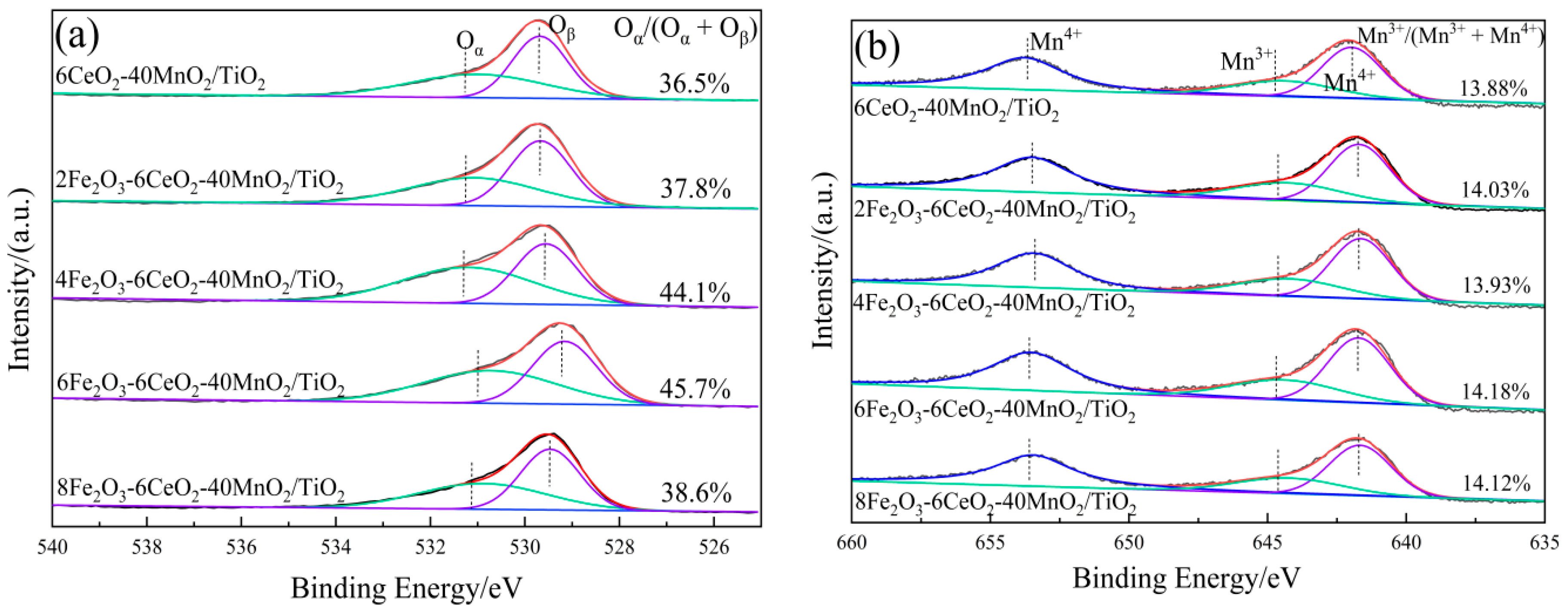

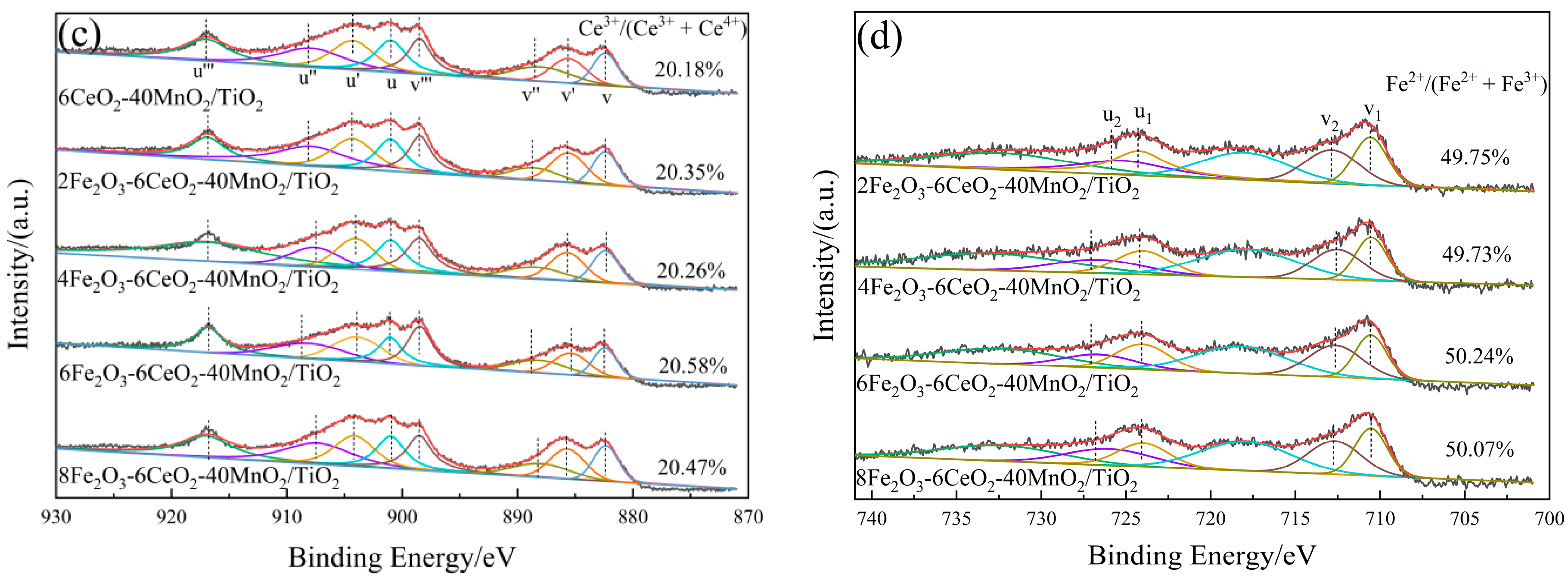

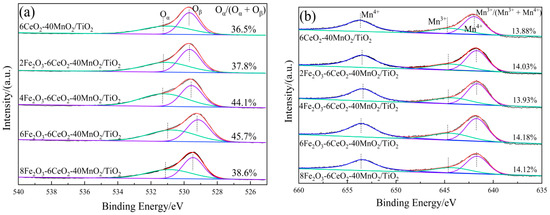

In order to explore the influence of Fe2O3 addition on the surface element distribution and redox performance of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, XPS tests were performed on catalysts with different Fe2O3 addition amounts. The results are presented in Figure 5 and Table 2.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts ((a) O 1s; (b) Mn 2p; (c) Ce 3d; (d) Fe 2p).

Table 2.

Surface element content of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts (mass, %).

Figure 5a shows the O 1s spectrum of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst. Two characteristic peaks appear in the figure at approximately 532.2 eV and 530.1 eV, corresponding to chemically adsorbed oxygen (Oα) and lattice oxygen (Oβ), respectively. With increasing Fe2O3 content, the Oα peak tends to shift to lower binding energies, and the ratio of Oα to the total surface oxygen (Oα/(Oα + Oβ)) first rises and then decreases. Since Oα exhibits higher mobility than Oβ, it is generally considered to be more reactive in redox reactions [21]. The xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibits a maximum Oα/(Oα + Oβ) value of 45.7%, indicating that an appropriate amount of Fe2O3 can promote the formation of highly active Oα species and more oxygen vacancies on the catalyst surface. This enhances the catalyst’s denitration performance, which is consistent with the denitration performance test results presented in Section 2.6.

The Fe 2p spectrum of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is shown in Figure 5d. The Fe 2p spectrum suggests that the Fe elements in the catalyst coexist in the form of Fe3+(u2,v2) and Fe2+(u1,v1). After the Fe2O3 content is increased, the proportion of Fe2+ on the catalyst surface relative to the total Fe elements (Fe2+/(Fe2+ + Fe3+)) also increases, and the Fe2+/(Fe2+ + Fe3+) value of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is as high as 50.24%, indicating that increasing the Fe2O3 content can promote the redox reaction between Fe3+ and Fe2+: Fe3+ ↔ Fe2+ + Cat-[O]. This provides more active sites and oxygen vacancies, which are conducive to improving the denitration activity of the catalyst [22]. In addition, due to the coexistence of Fe2+ and Fe3+, there is a Fe2+/Fe3+ redox couple in the catalyst, which facilitates the storage and release of oxygen on the catalyst surface and enhances the redox capacity of the catalyst.

Figure 5b,c show the Mn 2p and Ce 3d spectra of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, respectively. As can be seen from the figures, when the amount of Fe2O3 added varies, the positions of the characteristic peaks and the peak areas do not change significantly. This indicates that the surface Ce4+/Ce3+ and Mn3+/Mn4+ ratios remain relatively constant, suggesting that varying the amount of Fe2O3 does not significantly alter the valence states of Mn and Ce on the catalyst surface.

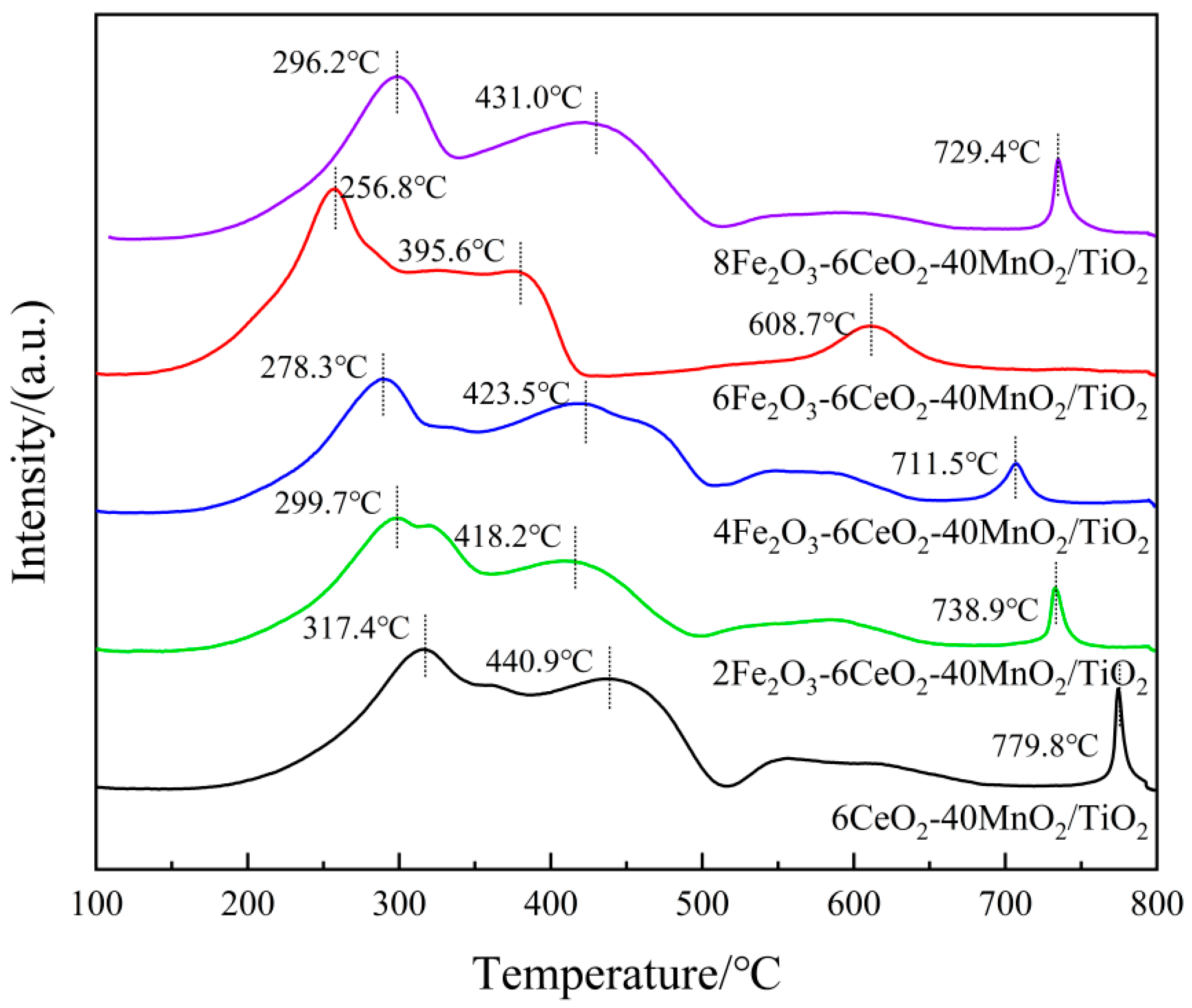

2.3. Acidic Sites Distribution of the Catalyst

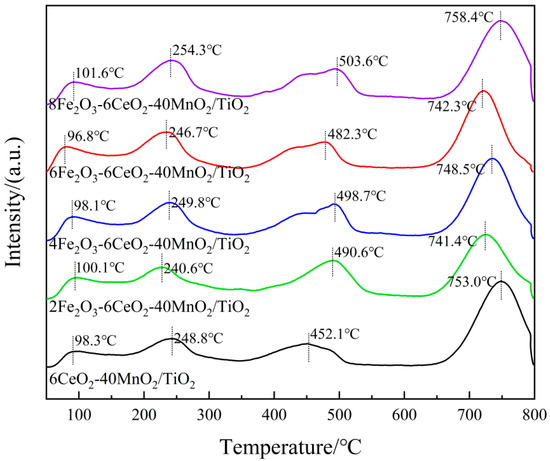

In order to study the influence of acid density, acid strength, and acid strength distribution on the catalyst surface on denitration performance, the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was analyzed using NH3-TPD. The results are shown in Figure 6 and Table 3. According to existing studies, the desorption peak located in the range of 25~200 °C represents a weak acid site, which is mainly derived from NH3 adsorbed by Lewis acid sites and physically adsorbed NH3. The peak between 200 and 400 °C corresponds to medium-strong acid sites, mainly due to NH3 adsorbed by Lewis acid sites. In addition, the desorption peak above 400 °C corresponds to strong acid sites, which belong to NH3 adsorbed by Brønsted acid sites [23]. As shown in Figure 6, with the change in Fe2O3 content, the position of the desorption peak of each acid site has not shifted significantly. According to the data in Table 3, with the increase in Fe2O3 content, the NH3 adsorption capacity of weak and medium-strong acid sites has not changed significantly, whereas the adsorption capacity of strong acids has increased. The 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibits the highest adsorption capacity. This indicates that increasing Fe2O3 promotes the formation of strong acid sites, thereby increasing the number of Brønsted acid sites on the catalyst surface. This complements the role of CeO2 in promoting the formation of weak and medium-strong acid sites (e.g., enhancing Lewis acid sites) [24]. Lewis acid sites are usually associated with the adsorption and activation of NH3, and are key active sites for low-temperature SCR; The Brønsted acid sites adsorb NH3 to form NH4+, which can enhance the activity at medium to high temperatures through a “rapid SCR” reaction (NH4+ + NO2 → N2 + H2O) and affect N2 selectivity (reducing excessive oxidation of NH3). After doping with Fe2O3, the number of strong acid sites on the catalyst surface increases, and the number of Brønsted acid sites on the catalyst surface increases. This is the main reason for the significant enhancement of high-temperature catalytic activity and N2 selectivity in the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst shown in Section 2.5.

Figure 6.

NH3-TPD pattern of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

Table 3.

NH3 adsorption capacity of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

2.4. Redox Performance of the Catalysts

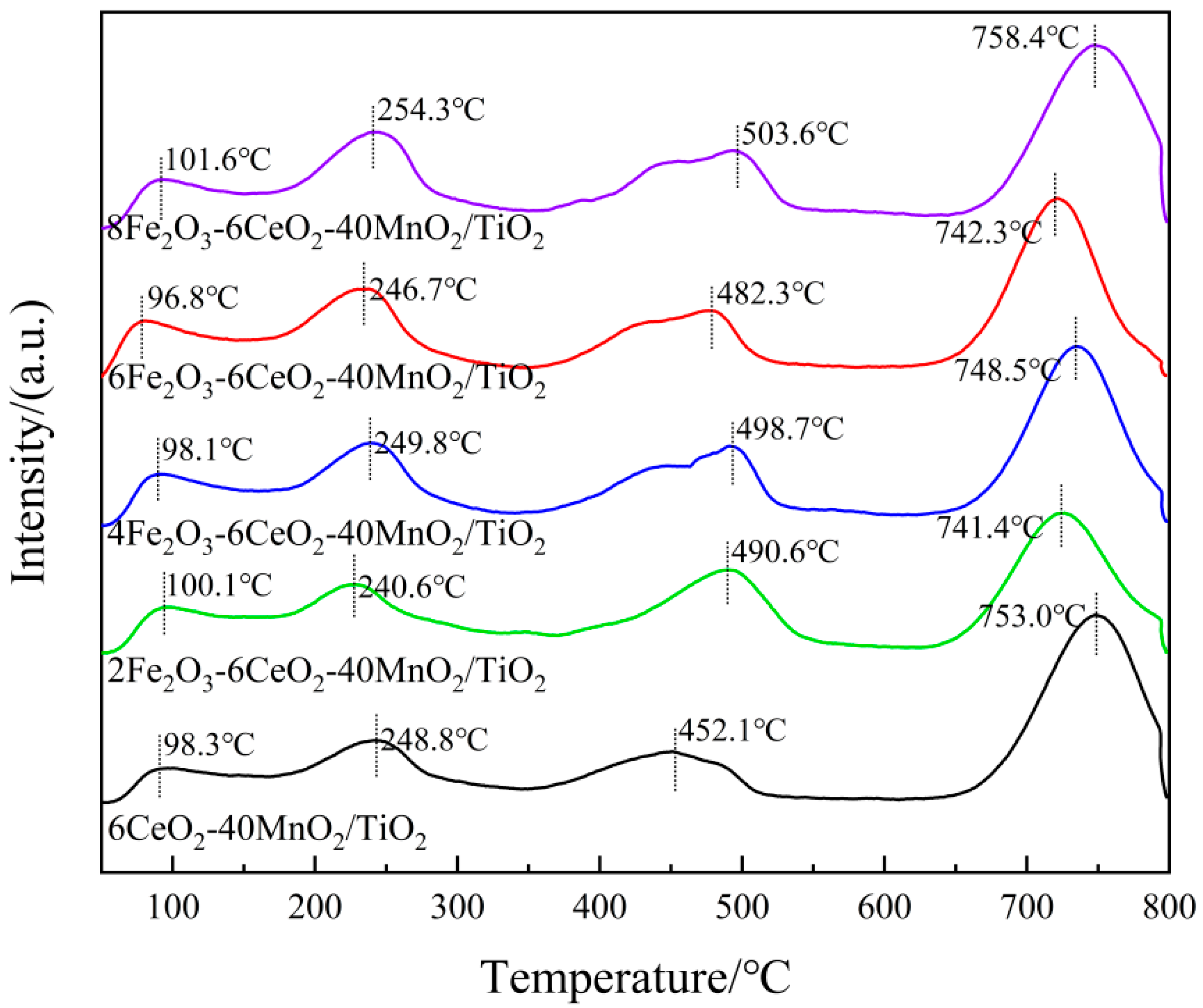

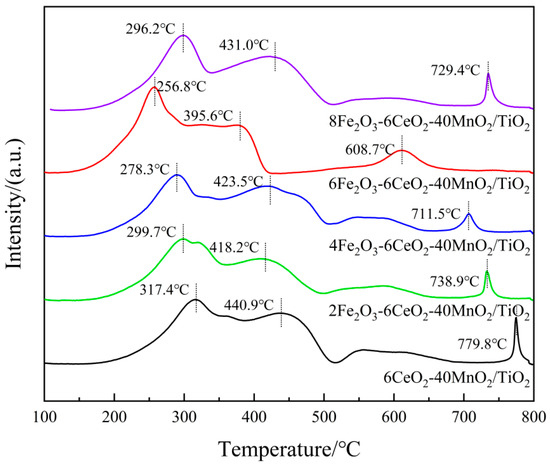

In the NH3-SCR reaction process, the redox performance of the catalyst plays a key role in the cyclic operation of the denitration reaction. To study the influence of Fe2O3 addition on the redox characteristics of the catalyst, the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts with different Fe2O3 contents were characterized and analyzed by H2-TPR. The results are shown in Figure 7 and Table 4.

Figure 7.

H2-TPR pattern of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

Table 4.

H2 consumption of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

In Figure 7, each catalyst sample demonstrates three reduction peaks. Among these, the reduction peaks ranging from 250 to 350 °C correspond to the reduction of Fe3+ → Fe2+, those ranging from 350 to 520 °C correspond to the reduction of Mn4+ → Mn3+, and those ranging from 520 to 800 °C correspond to the reduction of Ce4+ → Ce3+ [25,26,27]. When the amount of Fe2O3 added was gradually increased to 6%, the positions of each reduction peak shifted toward lower temperatures, suggesting that an appropriate increase in Fe2O3 content can enhance the activity of oxygen species and improve the reduction capacity of the catalyst. When the Fe2O3 content continued to increase to 8%, the reduction peaks shifted toward higher temperatures again. This may be because the addition of a small amount of Fe2O3 enhances the interaction between Fe2O3, MnO2, and CeO2 (e.g., Fe3+ + Mn3+ ↔ Fe2+ + Mn4+, Fe3+ + Ce3+ ↔ Fe2+ + Ce4+). However, excessive Fe2O3 content leads to the disruption of the electron transfer balance among the active components, thus decreasing the reduction capacity of the catalyst. In addition, as the Fe2O3 content increases, the H2 consumption associated with Fe3+ → Fe2+ gradually increases. When the H2 consumption of the catalyst sample increases, the corresponding denitrification activity of the sample also improves. At the same time, the H2 consumption for Mn4+ → Mn3+ and Ce4+ → Ce3+ also increases, demonstrating that increasing the amount of Fe2O3 can increase the number of active species on the catalyst surface, thereby increasing the relative content of surface chemisorbed oxygen, which is beneficial for the NH3-SCR reaction. This observation is consistent with the XPS analysis results.

2.5. Catalytic Activity of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 Catalyst

2.5.1. The Denitration Performance of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 Catalyst

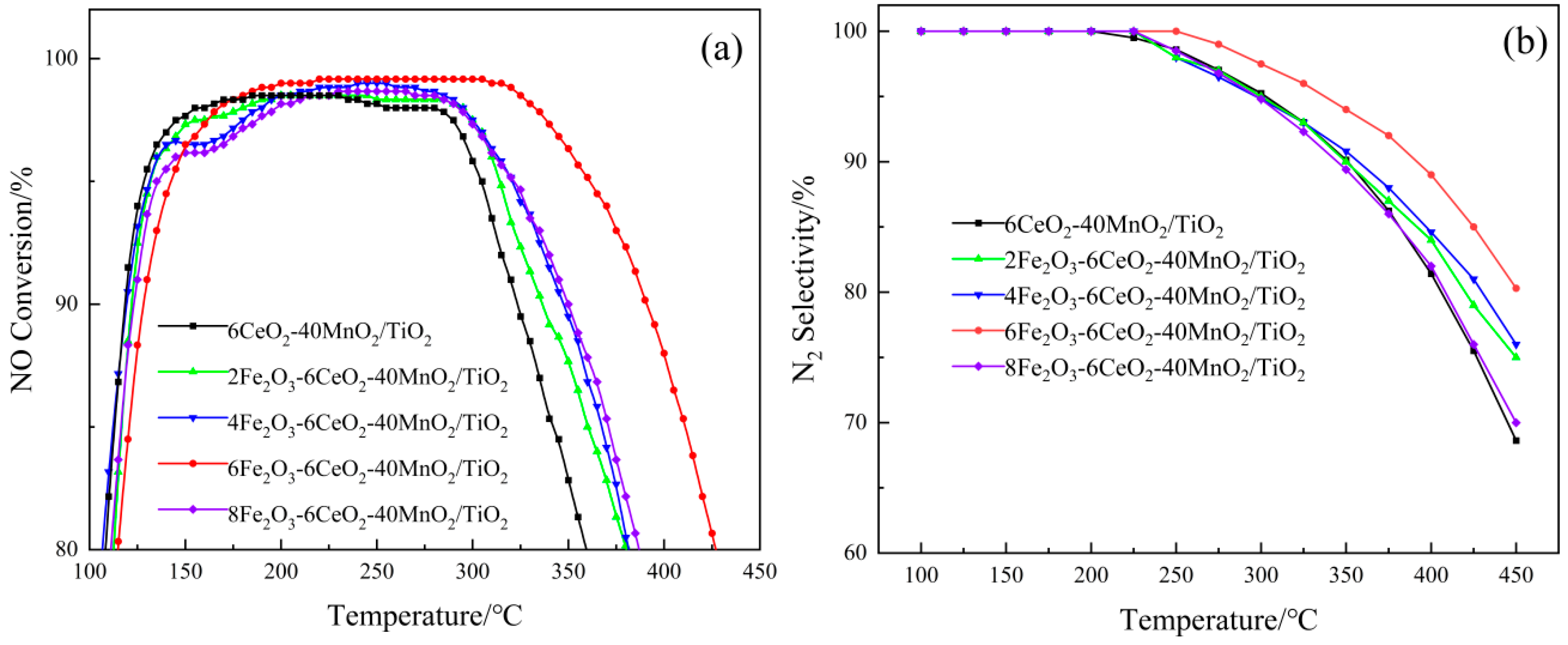

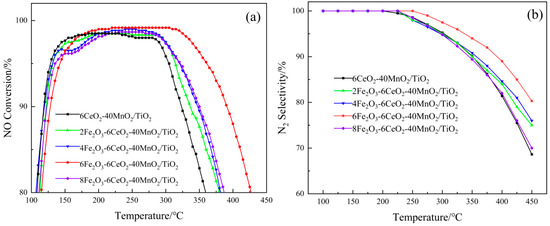

Figure 8 shows the experimental results of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst in terms of denitration performance. As shown in Figure 8a, without the addition of Fe2O3, the denitration effect of the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is the least ideal. The denitration efficiency is above 80% within the temperature range of 110~360 °C, while the temperature range where the efficiency exceeds 90% is 118~321 °C. With the gradual increase in Fe2O3 content, the denitration performance of the catalyst also shows an increasing trend. When the Fe2O3 content reaches 6%, the catalyst exhibits optimal denitration performance. At this point, the temperature range where the denitration efficiency exceeds 80% extends to 115~425 °C, and the range where the efficiency is higher than 90% is 129~390 °C. Between 220 and 305 °C, the denitration efficiency reaches its peak at 99.17%. However, when the Fe2O3 content is further increased to 8%, the denitration performance of the catalyst is weakened.

Figure 8.

The denitration performance of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts. (a) NO Conversion; (b) N2 Selectivity).

As shown in Figure 8b, the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibits 100% N2 selectivity at temperatures below 200 °C. Nevertheless, when the temperature rises above 200 °C, the selectivity of N2 begins to decrease, indicating that the NH3 adsorbed on the catalyst surface undergoes excessive oxidation at higher temperatures, resulting in the generation of the by-product N2O. With the increase in Fe2O3 content, the downward trend of N2 selectivity gradually slows down. Among them, the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibits optimal N2 selectivity, which can still be maintained at more than 80% at 450 °C, with the slowest decline rate. However, when the Fe2O3 content is further increased to 8Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2, the N2 selectivity of the catalyst deteriorates.

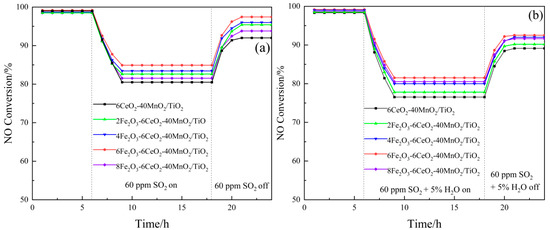

2.5.2. The Anti-SO2 and Anti-H2O Properties of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 Catalyst

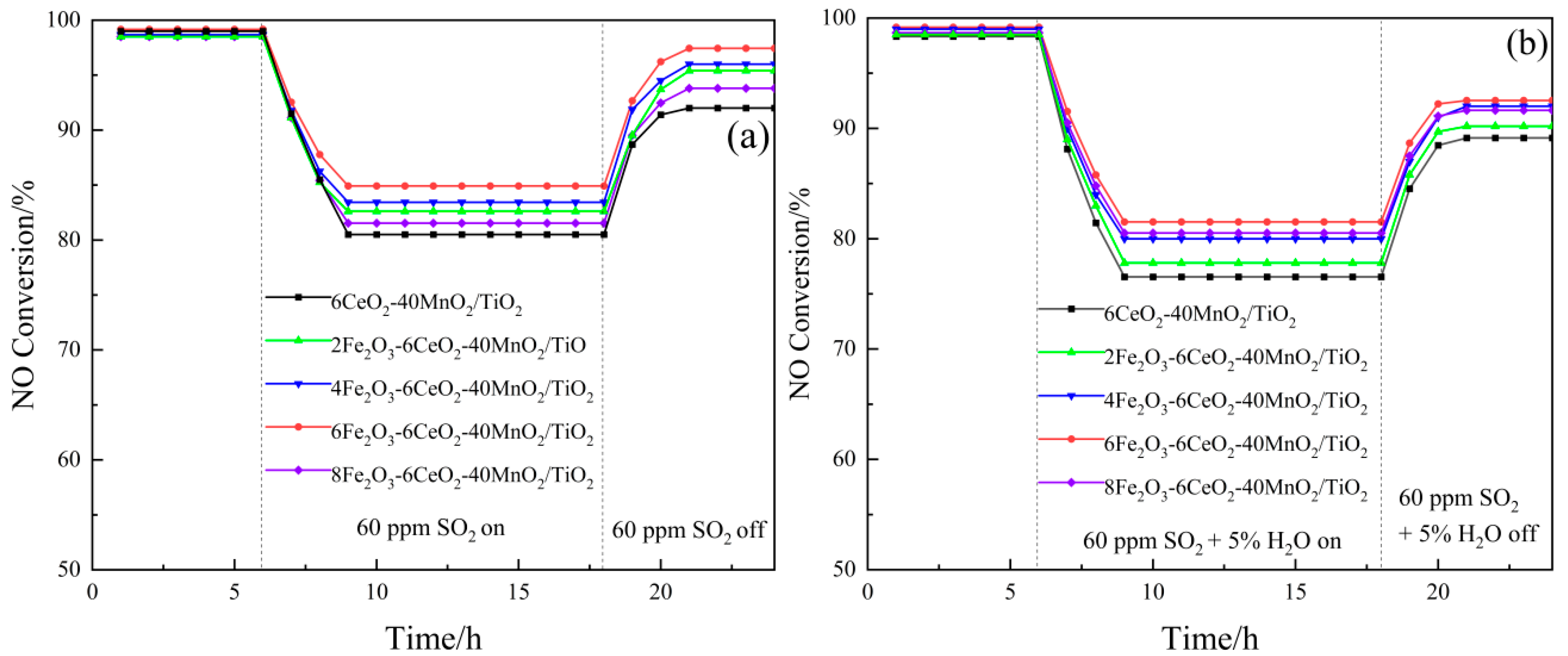

The test results of the SO2 and H2O resistance of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst are shown in Figure 9. Each group of catalysts was first stabilized at 200 °C for 6 h, and then 60 ppm SO2 was introduced into the simulated flue gas. The denitration efficiency of the catalysts with SO2 contents of 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% decreased to 80.5%, 82.6%, 83.4%, 84.8%, and 81.5%, respectively, and then gradually stabilized. After 18 h, the introduction of SO2 was stopped, and the denitration efficiency gradually recovered to a certain value and remained stable. Among them, the denitration performance of the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was most affected by SO2, while the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was least affected. Its denitration efficiency rose to a higher value after the introduction of SO2 was stopped. This is probably due to the fact that an appropriate amount of Fe2O3 can increase the dispersion of the active substance on the catalyst surface, providing more active sites, thereby improving the anti-SO2 performance of the catalyst.

Figure 9.

SO2 and H2O resistance of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts ((a) SO2; (b) SO2 and H2O).

Also after constant temperature denitration at 200 °C for 6 h, 60 ppm SO2 and water vapor with a volume fraction of 5% were simultaneously introduced into the mixed flue gas, and the denitration efficiency of the catalyst with FeO2 content of 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% was reduced to 76.5%, 77.8%, 80.1%, 81.6%, and 80.5%, respectively. After that, it gradually stabilized, and the introduction of SO2 and H2O was stopped at 18 h. Afterward, the denitration efficiency recovered to some extent. Among them, the 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was most affected by SO2 and H2O, while the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst exhibited good anti-SO2 and anti-H2O properties.

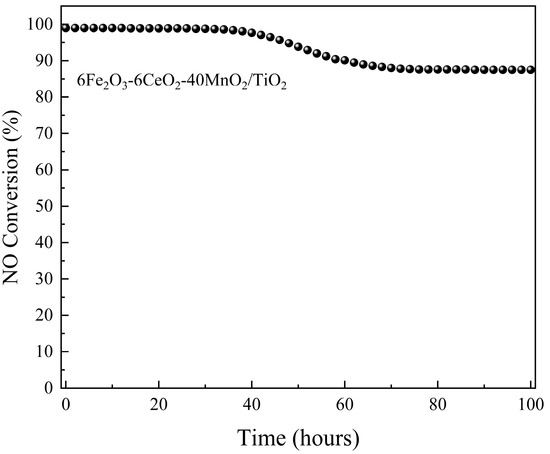

2.5.3. Stability of Catalytic Activity of 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 Catalyst

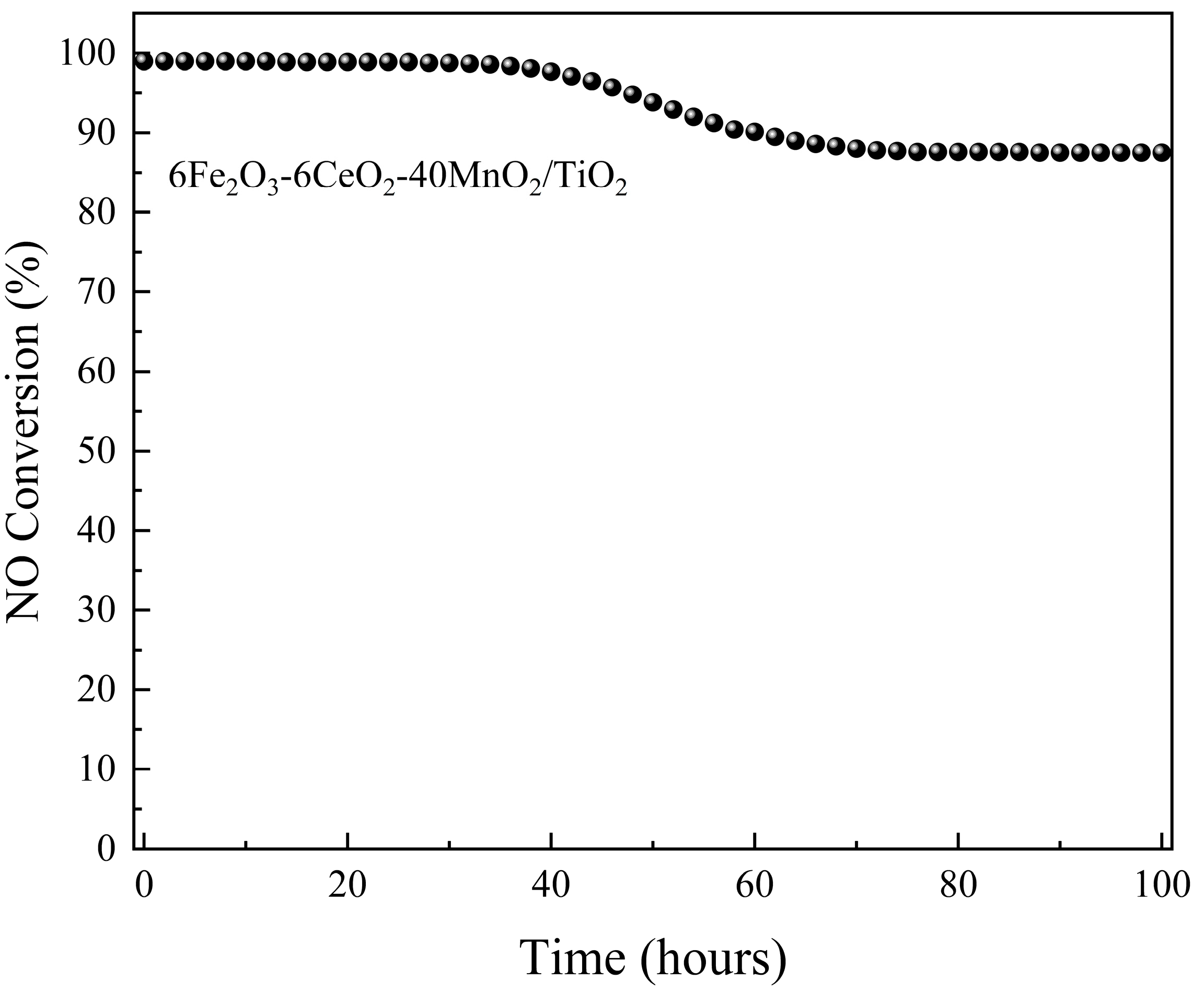

To evaluate the stability of the catalytic activity of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, its performance was continuously monitored for 100 h at 240 °C. Denitrification efficiency was recorded at two-hour intervals. The results are presented in Figure 10. For the first 34 h, the catalytic activity remained stable at about 99%. From 36 h onward, a decline in denitrification efficiency was observed, reaching 87.5% by 76 h. This level was maintained until the conclusion of the test.

Figure 10.

Stability of catalytic activity of 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst.

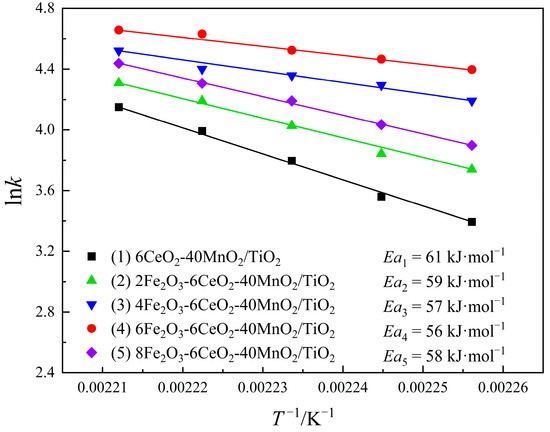

2.5.4. Kinetic Analysis of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 Catalyst

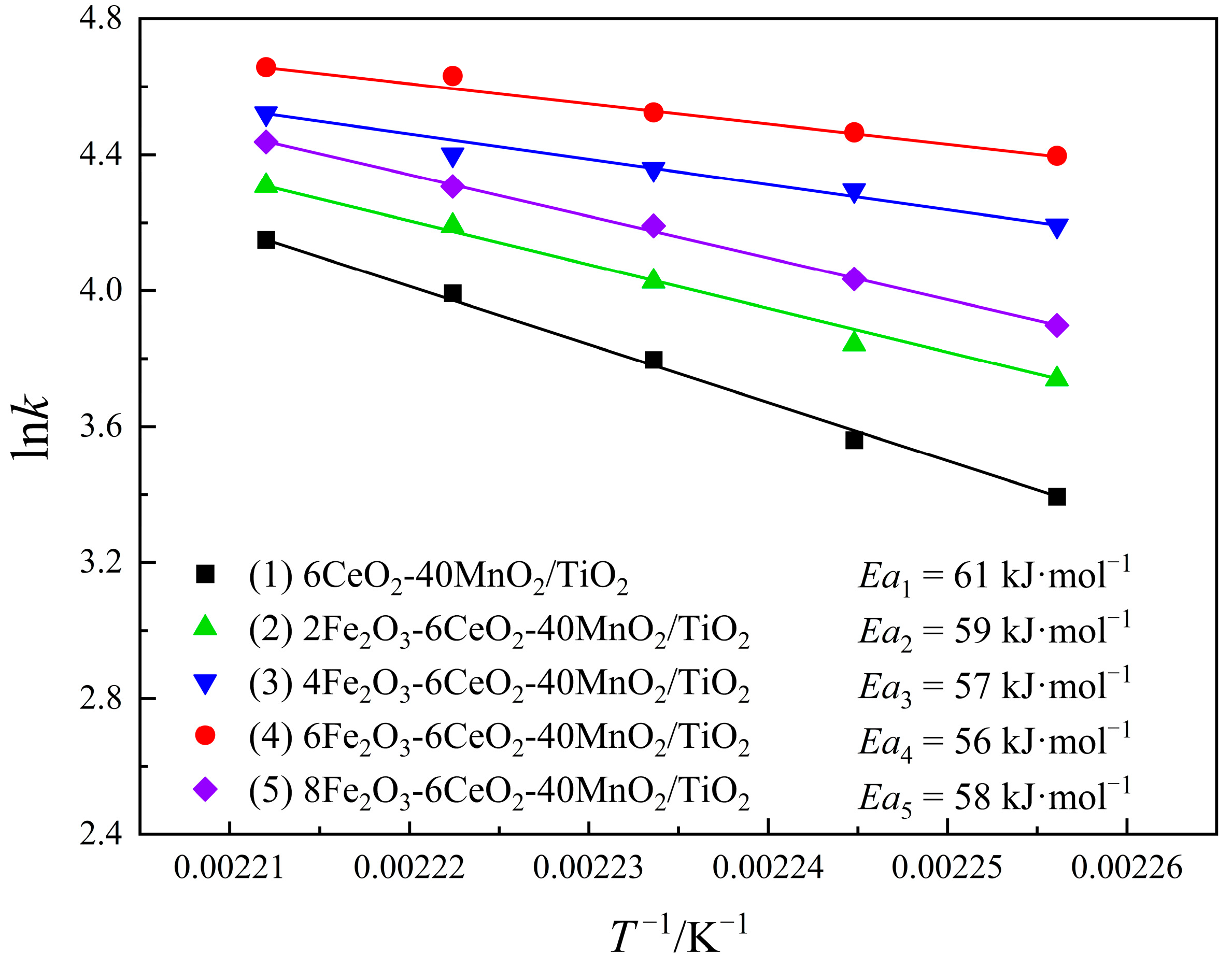

In order to explore the effect of Fe2O3 modification on the reaction rate of the CeO2-MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, the kinetic characteristics of its denitration reaction were analyzed in this study. By comparing the apparent activation energy of the catalytic reaction, different reaction paths can be identified, and the adsorption and desorption behavior of the reactants on the catalyst surface can be further understood [28]. The reaction rate constant k is calculated based on Equation (3).

where k is the reaction rate constant in cm3·g−1·s−1, V represents the gas flow rate (cm3·s−1), W is the mass of the catalyst (g), and X represents the conversion rate of NO. After calculating the k value using Equation (3) and combining it with the specific values of R and T, the three-point fitting method is applied to the Arrhenius plot. The expression is as follows (Equation (4)):

where A is the precursor (cm3·g−1·s−1), Ea represents the apparent activation energy (J·mol−1), R is the universal gas constant, which has a value of 8.314 J·K−1·mol−1, and T is the reaction temperature (K). A graph is drawn with 1/T as the abscissa and the natural logarithm of the reaction rate k is plotted as the ordinate. There is a linear relationship between 1/T and lnk, and the reaction activation energy Ea can be obtained after linear regression.

Combined with the test results of the denitration performance of the catalyst, the denitration reaction dynamics of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst were studied using Equations (3) and (4). The results are shown in Figure 11. As can be obtained from Equation (4), lnk has a linear relationship with T−1. The smaller the absolute value of the slope, the smaller the reaction activation energy Ea, and the easier the denitration reaction proceeds. As the Fe2O3 content increases, the activation energy of the catalyst gradually decreases. The 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst has a minimum activation energy of 56 kJ·mol−1. In addition, as the reaction temperature increases, the reaction rate of the catalyst increases. At the same temperature, the reaction rates follow the order: 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 > 4Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 > 8Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 > 2Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 > 6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2, which is consistent with the denitration performance test results shown in Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Kinetic diagrams of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalysts.

2.6. Catalytic Mechanism Analysis of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 Catalyst

Through the above analysis, the catalytic activity of the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst is influenced by a variety of factors, and one of the main reasons is the variation in acidic sites. The SCR reaction is a heterogeneous gas–solid reaction catalyzed by a solid catalyst, which requires the catalyst to have sufficient active sites to adsorb the reaction gases. In order to study the changes in the adsorption characteristics of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst during the low-temperature NH3-SCR reaction and to explore the catalytic reaction mechanism on the catalyst surface, in this part, in situ DRIFTS was used to investigate the interaction between the reaction gases (NH3 and NO) and the catalyst surface.

- (1)

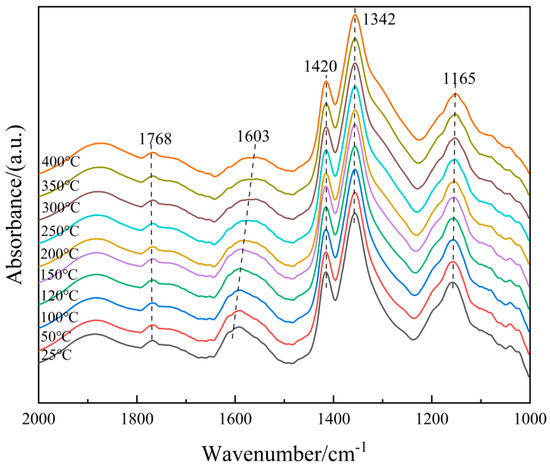

- Adsorption of NH3

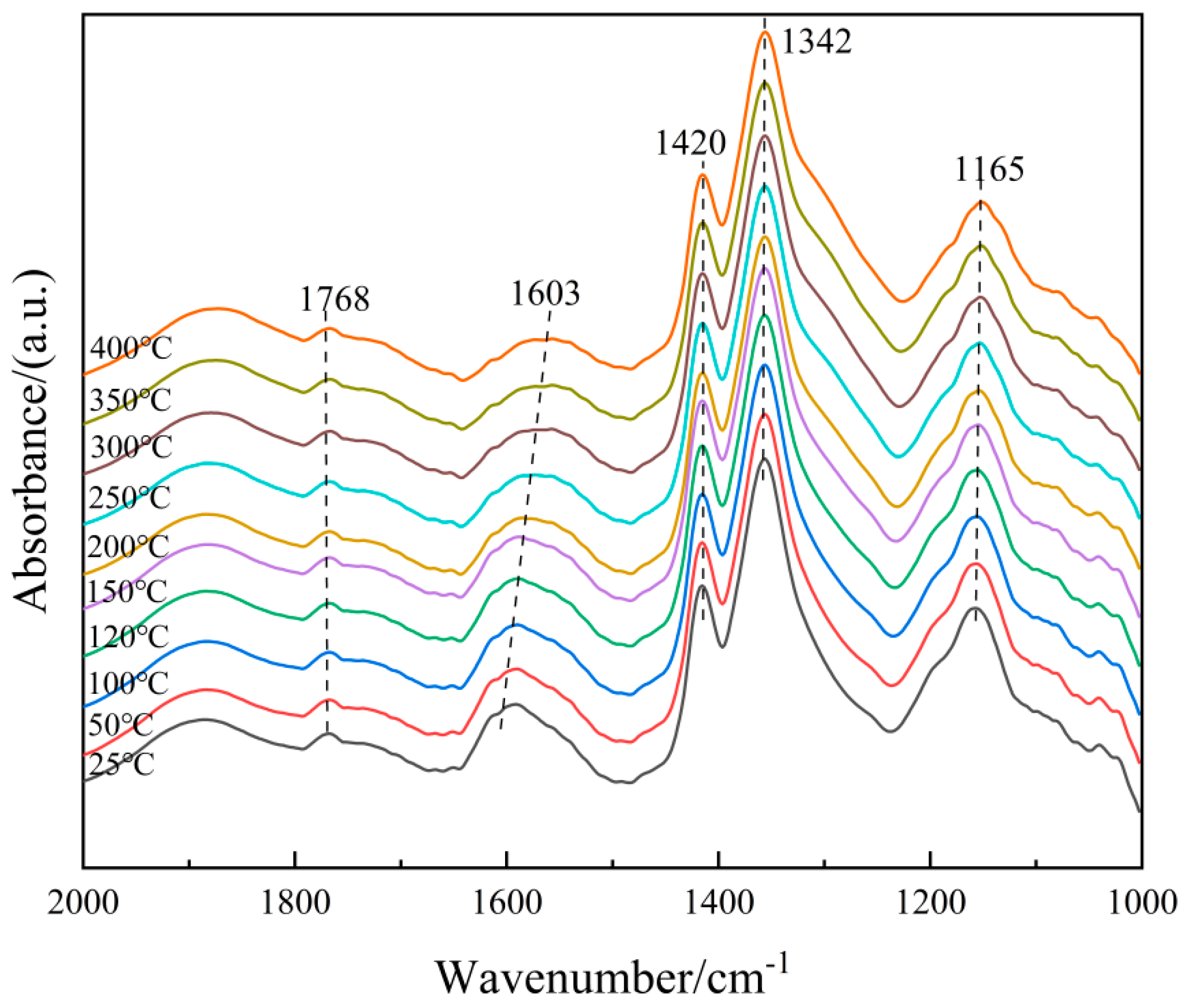

In order to further clarify the properties of the NH3(ad) species on the surface of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, in situ DRIFTS of NH3 adsorption at different temperatures were conducted, and the results are shown in Figure 12. Based on the spectrum of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, the bands that appear at 1768 cm−1, 1603 cm−1, 1342 cm−1, and 1141 cm−1 correspond to NH3 molecules coordinated to Lewis acid sites, while the band at 1420 cm−1 corresponds to NH4+ ions adsorbed at Brønsted acid sites [29,30]. As the temperature increases, the weakening of peak intensity is mainly due to thermal desorption and possible decomposition, and the attenuation rate is related to the adsorption enthalpy. By comparison, the adsorption peaks corresponding to Brønsted acid sites weaken more rapidly, probably indicating that Lewis acid sites have stronger thermal stability due to higher adsorption enthalpy. Therefore, at low temperatures, NH3 adsorption in the catalytic reaction involves both Lewis and Brønsted acid sites, whereas at high temperatures, NH3 adsorption mainly occurs at Lewis acid sites.

Figure 12.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of NH3 adsorption on 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst.

- (2)

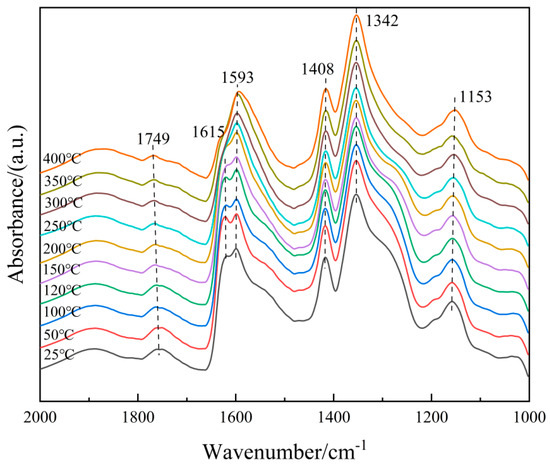

- Co-adsorption of NO + O2

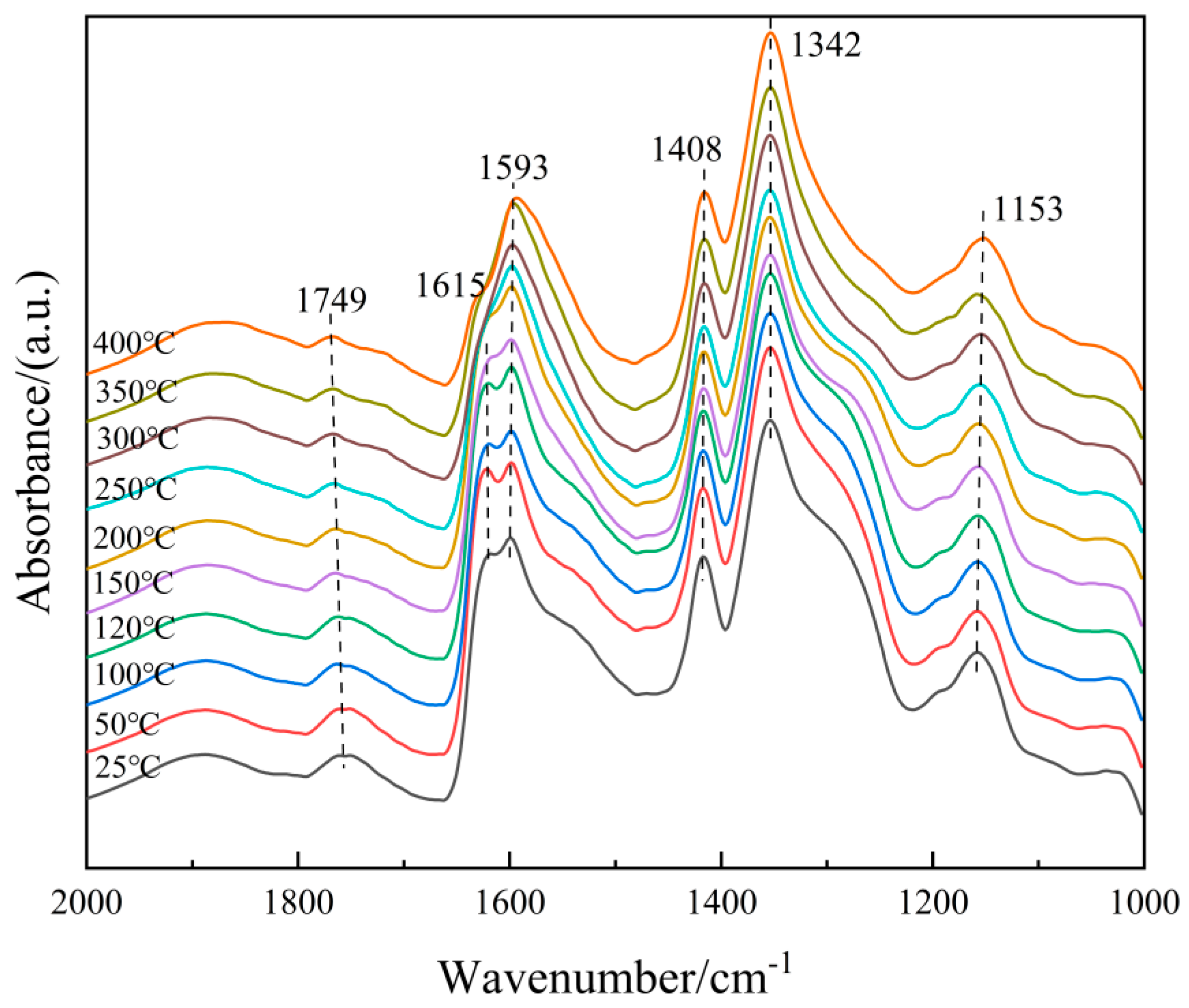

To understand the microscopic process of the NH3-SCR reaction on the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, it is necessary to distinguish the adsorbent species on the surface of the catalyst. Therefore, an in situ co-adsorption experiment of NO + O2 was carried out on the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst, and the results are shown in Figure 13. The 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was exposed to a NO + O2 mixed gas (500 ppm NO + 5% O2, N2 balance) at room temperature, and multiple infrared vibration signal peaks appeared between 1000 and 2000 cm−1. Among them, the bands located at 1408 cm−1 and 1593 cm−1 can be attributed to bidentate nitrates; the band located at 1153 cm−1 is related to monodentate nitrates; the band located at 1342 cm−1 belongs to M-NO2 nitro compounds; the band located at 1615 cm−1 belongs to adsorbed NO2; and the band located at 1749 cm−1 belongs to the physical adsorption of NO2 [31,32]. As can be seen from Figure 11, as the temperature rises, the absorption peak intensity corresponding to monodentate nitrate (1153 cm−1) gradually decreases with increasing temperature, while the absorption peaks of bidentate nitrates (1408 cm−1 and 1593 cm−1) appear at lower temperatures and are not easily decomposed. This is due to the low thermal stability of the monodentate nitrate and a certain degree of desorption on the surface of the catalyst at high temperatures, which is consistent with the fact that bidentate nitrates are more thermally stable than monodentate nitrates. The peak intensity corresponding to the adsorbed NO2 (1615 cm−1) gradually decreases with increasing temperature, which is probably related to the effect of NO oxidation and the accelerated desorption of NO2 after the temperature increase.

Figure 13.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of NO + O2 adsorption on 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst.

- (3)

- The microscopic reaction process of the catalyst

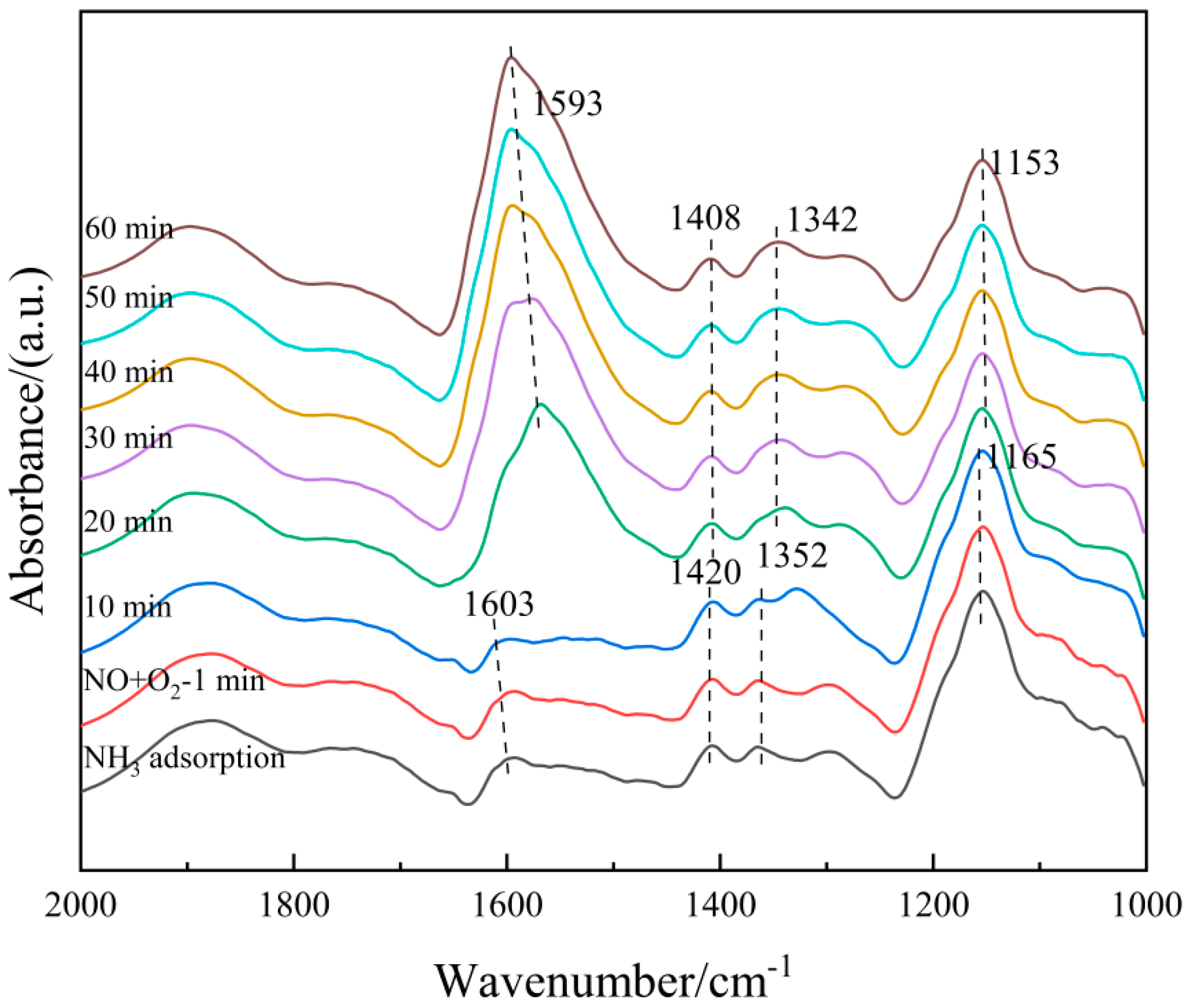

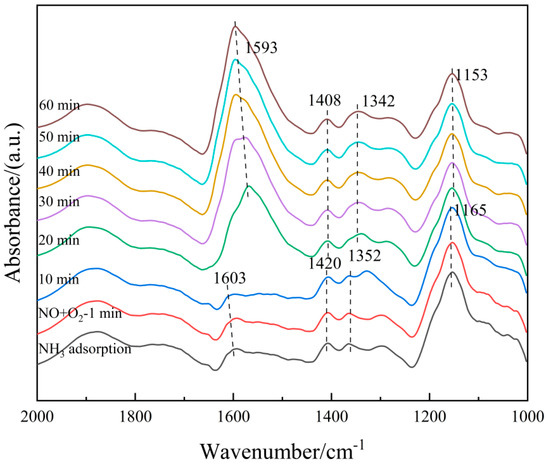

The 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst pre-adsorbed with NH3 was subjected to in situ co-adsorption tests of NO + O2, in order to explore the microscopic process of the NH3-SCR reaction on the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst at 250 °C. The results are shown in Figure 14. At 250 °C, when NH3 adsorption is saturated, signals corresponding to Lewis acid sites (1165 cm−1, 1352 cm−1, and 1603 cm−1) and Brønsted acid sites (1420 cm−1) can be observed. Then, the NH3 gas supply was turned off, and a NO + O2 mixed gas (500 ppm NO + 5% O2, balanced with N2) was introduced. The following phenomena were observed over time: After 20 min of NO + O2 exposure, the signals related to NH3 adsorption completely disappeared, indicating that the NH3 species adsorbed on the catalyst surface had almost entirely participated in the reaction. Subsequently, absorption peaks corresponding to bidentate nitrates (1408 cm−1), monodentate nitrates (1153 cm−1), M-NO2 nitro compounds (1342 cm−1), and adsorbed NO2 (1602 cm−1) appeared. The intensity of the bidentate nitrate peak at 1408 cm−1 further increased with prolonged reaction time, likely due to the accumulation of bidentate nitrate species after the surface-adsorbed NH3 species were fully consumed. These results indicate that the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst can adsorb NO + O2 and convert it into various nitrate species. These nitrate species then react with the NH3 species previously adsorbed on Lewis and Brønsted acid sites to complete the denitration reaction cycle. The NH3-SCR reaction on the catalyst surface follows the L-H mechanism, as shown in Equations (3)–(11) [33].

Figure 14.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of NO + O2 adsorption on 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst with pre-adsorption of NH3.

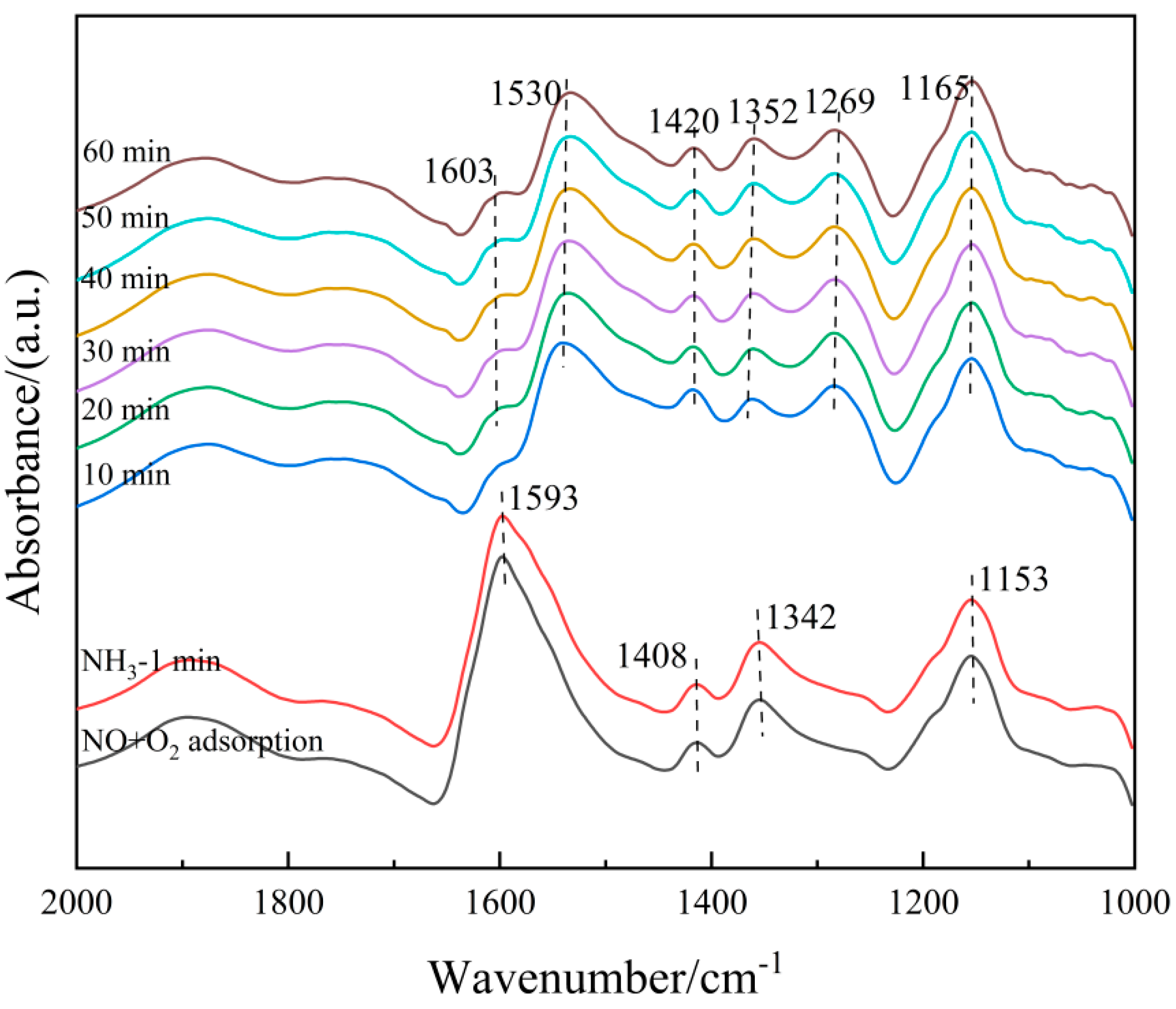

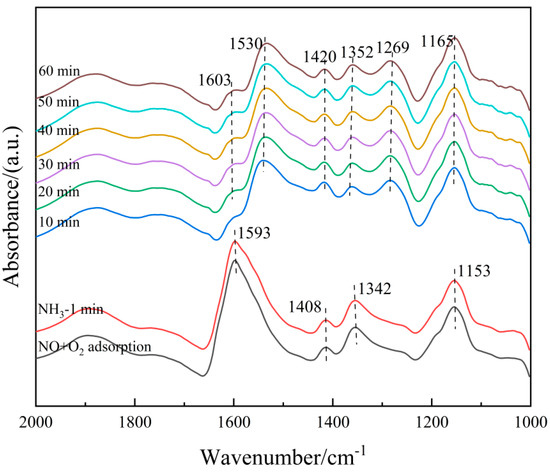

On the other hand, the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst pre-adsorbed with NO + O2 was subjected to in situ NH3 adsorption at 250 °C, as shown in Figure 15. When the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst adsorbs NO + O2 at 250 °C and reaches saturation, the absorption peaks of bidentate nitrate (1408 cm−1), monodentate nitrate (1153 cm−1), bridged nitrate (1269 cm−1), M-NO2 nitro compound (1342 cm−1), and adsorbed NO2 (1602 cm−1) can be detected. Then, the NO + O2 mixed gas is turned off and NH3 gas is introduced. Over time, the following phenomena occur: When NH3 gas is introduced for 10 min, the signals related to the adsorption of NO + O2 disappear, indicating that the nitrate species adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst have fully participated in the reaction. After 10 min, the Lewis acid sites (1165 cm−1, 1352 cm−1, and 1603 cm−1) and Brønsted acid sites (1269 cm−1, 1420 cm−1, and 1530 cm−1) adsorb NH3 species, forming corresponding absorption peaks. The intensity of each absorption peak does not change significantly with the extension of reaction time, indicating that the reaction is complete at this point. The above results show that the NOx species adsorbed on the surface of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst can react with gaseous NH3 molecules, indicating that the NH3-SCR reaction on the catalyst surface also follows the E-R mechanism. Combining Figure 14 and Figure 15, it can be concluded that the NH3-SCR reaction on the surface of the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst follows both the L-H and E-R mechanisms, with the L-H mechanism being dominant.

Figure 15.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of NH3 adsorption on 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst with pre-adsorption of NO + O2.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

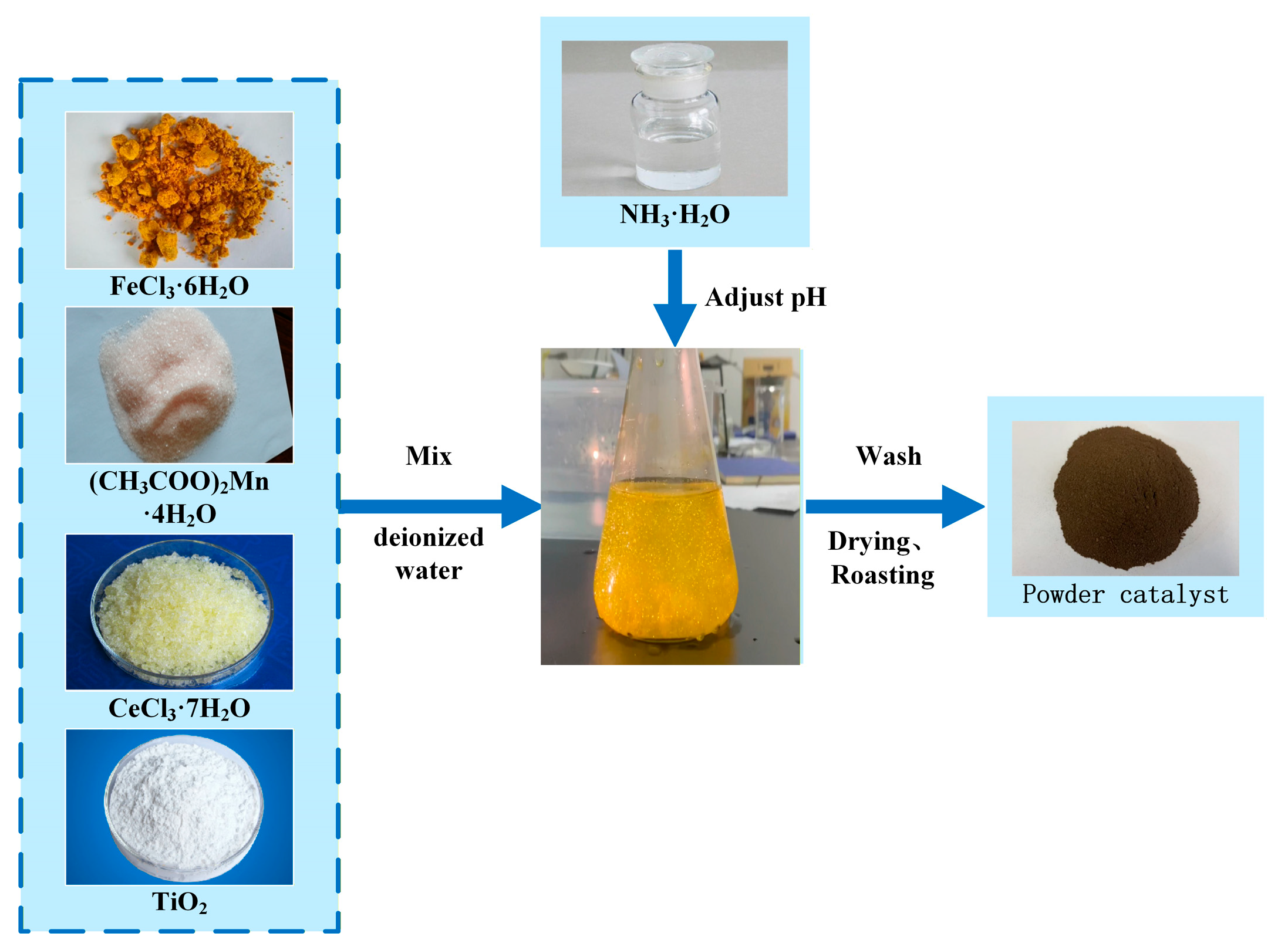

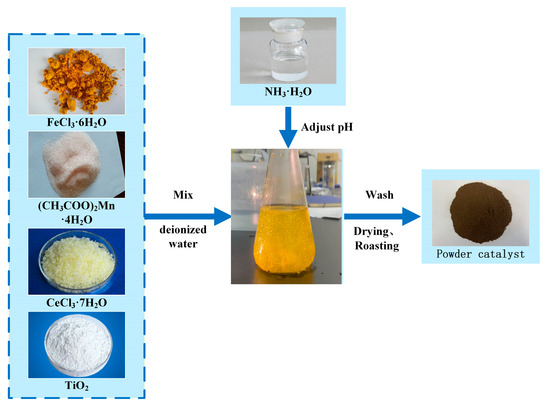

The Fe2O3-CeO2-MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was prepared by the co-precipitation method. The preparation steps are as follows: Manganese acetate tetrahydrate ((CH3COO)2Mn·4H2O, China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China), cerium chloride heptahydrate (CeCl3·7H2O, China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China), iron chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O, China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China), and anatase (TiO2, China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China) were added to a beaker containing deionized water in a specific weight ratio. The mixture was continuously stirred for 0.5 h, and ammonia was then added dropwise to the catalyst solution until the pH reached 9~10. After that, the mixture was stirred for an additional 3 h and filtered, and deionized water was added to the filter cake. The mixture was stirred and washed for 0.5 h, and then filtered again. These operations were repeated three times. The resulting filter cake was dried at 75 °C for 24 h. Finally, the dried filter cake was placed in a muffle furnace and roasted at 400 °C for 4 h to obtain the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst. The x-value represents the mass percentage of Fe2O3 in the entire catalyst (×100), and the values used were 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8. The actual x-value was determined by ICP and rounded to the nearest integer. The preparation process is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst preparation process.

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using an X-ray diffractometer, model JSM-7800F (Tokyo, Japan), manufactured by the Japanese Electronics Company. The test conditions included a Cu target, Kα radiation, an analysis voltage of 40 kV, an analysis current of 40 mA, a scanning range of 5° to 90°, and a scanning rate of 2° per minute.

The N2 adsorption–desorption curve was measured using the ASAP-2020 (Mike Instrument Company, Washington, DC, USA) physical adsorption instrument from Micromeritics Company in the United States. Prior to the test, the sample was vacuum-treated at 400 °C for 4 h. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method was used to calculate the specific surface area of the sample, and the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method was employed to determine the pore size distribution.

For scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis, a Hitachi SU8020 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) ultra-high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope was used, with a magnification range from 300,000 to 800,000 times. The X-ray spectrometer attached to the SEM has an elemental analysis range from B5 to U92 and an energy resolution of 130 eV.

A JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope (Nippon Electronics Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was used, which has a point resolution of 0.23 nm, a magnification range of 50 to 1,000,000, and an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. With this instrument, we observed the particle size and microstructure of the catalyst and conducted nanoscale analysis of the catalyst through high-resolution lattice fringe images.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out using the Thermo Fisher Scientific Escalab 250Xi X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New York, NY, USA). The excitation source was Al Kα (1486.6 eV), and the acceleration voltage was 150 W. The binding energy of C 1s (284.8 eV) was used as the internal standard. Peak fitting was performed using XPS Peak 4.1 software.

Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR) was analyzed using a Micromeritics Autochem II 2920 chemical adsorption instrument (Micromeritics, New York, NY, USA). The test conditions are as follows: Take about 70 mg of sample and place it in a quartz tube; heat it up to 300 °C for drying and pretreatment; purify with He gas for 1 h, and then cool it to room temperature; pass a 10% H2/Ar mixture through it for 30 min until the baseline is stable; finally, heat it up to 800 °C in a 10% H2/Ar atmosphere for TPR. The gas flow rate is 50 mL/min, and the heating rate is 10 °C/min. The detector used is a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD), which detects the consumption of the reducing gas.

Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) tests were carried out on an AutoChem II 2920 Chemisorption Analyzer (Micromeritics, New York, NY, USA). The specific conditions were as follows: approximately 70 mg of the sample was weighed and placed into a quartz tube; the sample was heated to 300 °C for drying and pretreatment under a flowing He gas atmosphere. After 1 h, cool it to room temperature. Subsequently, a 10% NH3/He gas mixture was introduced for 1 h to achieve saturation; the gas was switched to He, and the sample was purged for 1 h to remove physically adsorbed NH3. Finally, the sample was heated to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a He gas flow (50 mL/min), and the desorbed gas was detected using a TCD.

In situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (In situ DRIFTS) was performed using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet IS50 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The measurement procedure was as follows: approximately 15 mg of sample was placed flat in a small crucible and fixed inside a high-temperature in situ cell. The sample was pretreated with N2 at 400 °C for 1 h, then cooled to room temperature. Background spectra (32 scans, 4 cm−1 resolution) were collected periodically as references. Subsequently, the corresponding reaction gas (1000 ppm NH3, 1000 ppm NO, and 5% O2 by volume) was introduced for in situ infrared adsorption studies. For NH3 or NO + O2 adsorption, the gas was introduced at 200 °C, and data were collected over time. For the experiment involving initial NH3 pre-adsorption followed by NO + O2 exposure, saturated NH3 adsorption was first conducted at 200 °C, after which the NO + O2 mixture was introduced, and data were collected over time. Similarly, for the experiment involving initial NO + O2 pre-adsorption followed by NH3 exposure, saturated NO + O2 adsorption was performed at 200 °C, followed by NH3 introduction, and data were collected over time. At the end, the background spectrum was subtracted to obtain the infrared spectra at each time point.

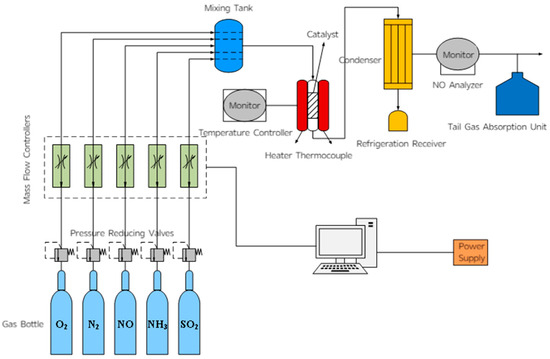

3.3. Measurement of Catalyst Activity

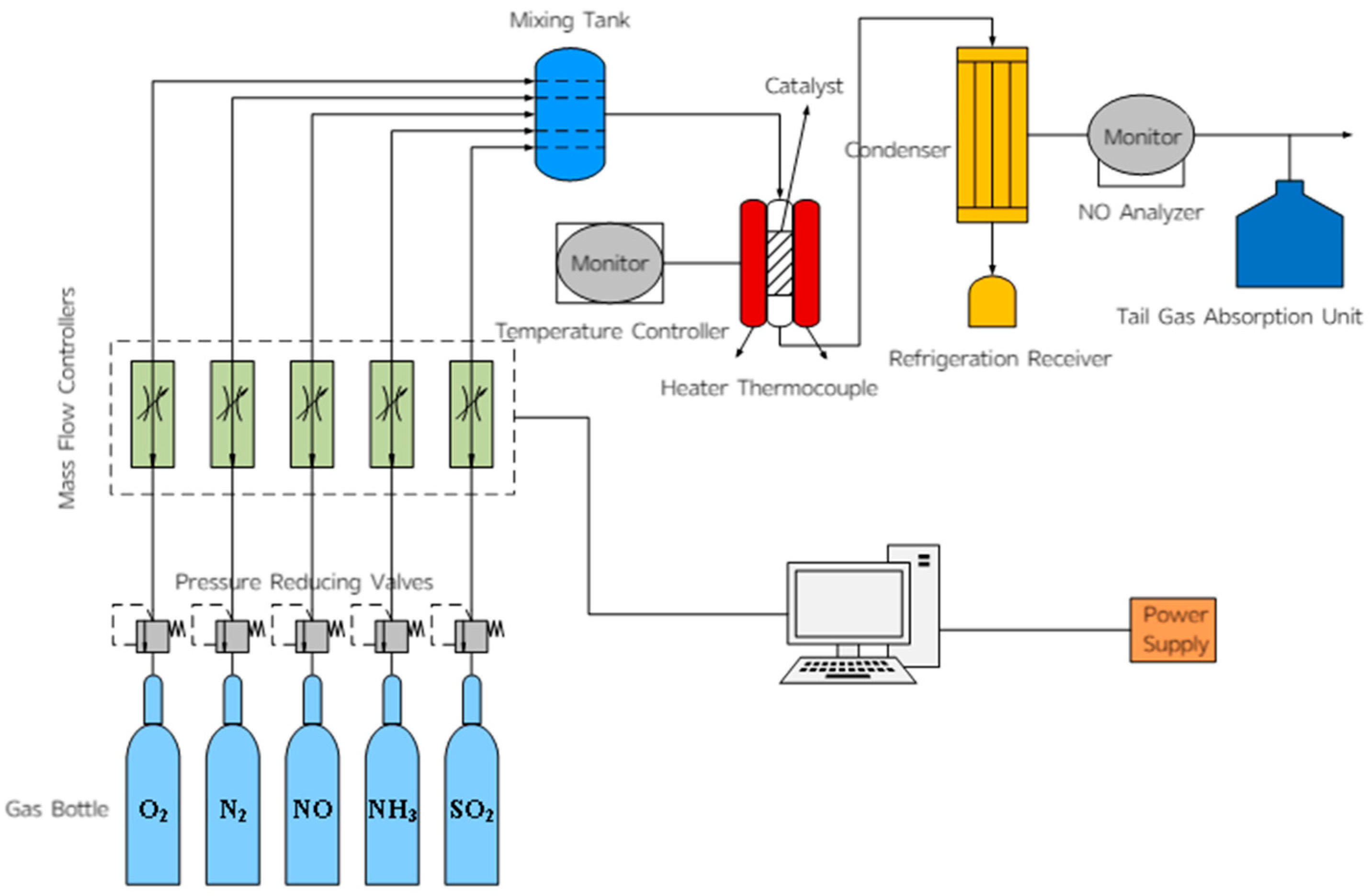

The laboratory micro-reaction device was used as shown in Figure 17 to simulate the components of the flue gas. The test conditions were as follows: a 5 mL catalyst sample, a gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 36,000 h−1, and a simulated flue gas composition consisting of 600 ppm NO, 300 ppm O2, 600 ppm NH3, and 60 ppm SO2 (when required), with N2 as the balance gas. Five milliliters of the catalyst to be tested were placed in a fixed-bed reactor, the flow control system was turned on, and the gas parameters were set. The pipeline was purged with N2, and the air tightness of the system was checked after 5 min. Then the final temperature was set, the temperature control switch was turned on, other gases were introduced, and the NO concentration detected by the analyzer was recorded as the temperature changed. After the test was completed, the other gas switches were turned off, N2 continued to flow, and the pipeline was purged with N2 until the NO detection indicator dropped to zero (NH3 analyzer model: Taihe Lianchuang THA100 (Taihe Lianchuang, Beijing, China); The models of NO, N2O, and NO2 analyzers are Wuhan Sensuo Technology SS7200, Wuhan, China).

Figure 17.

Schematic diagram of fixed-bed catalytic reactor.

The equations for calculating the denitration efficiency and N2 selectivity of the catalyst are as follows:

where [NO]in represents the input concentration of NO, [NO]out denotes the output concentration of NO, [NH3]in signifies the input concentration of NH3, [NH3]out refers to the output concentration of NH3, and [N2O] is the output concentration of N2O.

4. Conclusions

In this study, based on the Ce-Mn/TiO2 catalyst, Fe2O3 was introduced for modification, and a new type of xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was prepared. Its denitration properties and reaction kinetics in the NH3 selective catalytic reduction in the NO (SCR) reaction were systematically investigated. The experimental results show that the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst modified with 6% Fe2O3 exhibits the best denitration performance. This catalyst has the lowest reaction activation energy (Ea = 56 kJ·mol−1), and its denitration efficiency exceeds 80% and 90% within the temperature ranges of 115~425 °C and 129~390 °C, respectively. The denitration efficiency reaches as high as 99.17% within the temperature range of 220–305 °C. Additionally, it exhibits good N2 selectivity and excellent resistance to SO2 and H2O. To conduct an in-depth analysis of the influence of Fe2O3 addition on catalyst performance, the xFe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst was systematically studied using various characterization methods, such as XRD, BET, SEM, TEM, XPS, TPR, and TPD. The results show that after the addition of 6% Fe2O3, the TiO2 lattice contracts to some extent, enhancing its dispersion and significantly increasing the specific surface area of the catalyst. In addition, the content of chemically adsorbed oxygen on the catalyst surface and the proportion of low-cost metal ions such as Fe2+, Ce3+, and Mn2+ have increased substantially, providing more oxygen vacancies and active sites for the SCR reaction. Meanwhile, the number of strong acid sites on the catalyst surface has increased notably, and the redox capacity has been enhanced, which facilitates the NH3-SCR reaction. Further research has found that the introduction of Fe2O3 promotes the formation of strong acid sites, while CeO2, as the main active component, is more inclined to generate weak and medium-strong acid sites, thereby creating a favorable synergistic effect between the two. Through the analysis of in situ DRIFTS, it can be seen that the NH3-SCR reaction mechanism on the 6Fe2O3-6CeO2-40MnO2/TiO2 catalyst follows both the L-H and E-R mechanisms, with the L-H mechanism being the dominant reaction pathway.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and X.B.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, J.L.; validation, Y.Y., X.B. and J.L.; formal analysis, Z.J.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, Y.B.; data curation, Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.B.; visualization, Z.J.; supervision, J.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, X.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2022YFC2905302).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yuming Yang, Jiaqi Li and Zhongshuai Jia are employed by the company Baogang Group Mining Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zheng, F.; Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, J. Review on NH3-SCR for Simultaneous Abating NOx and VOCs in Industrial Furnaces: Catalysts’ Composition, Mechanism, Deactivation and Regeneration. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 247, 107773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirupathi, B.; Smirniotis, P.G. Nickel-Doped Mn/TiO2 as an Efficient Catalyst for the Low-Temperature SCR of NO with NH3: Catalytic Evaluation and Characterizations. J. Catal. 2012, 288, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Park, E.D.; Kim, J.M.; Yie, J.E. Cu-Mn Mixed Oxides for Low Temperature NO Reduction with NH3. Catal. Today 2006, 111, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Shi, J.-W.; Niu, C.; Wang, B.; He, C.; Cheng, Y. The Insight into the Role of Al2O3 in Promoting the SO2 Tolerance of MnOx for Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 398, 125572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.-K.; Wachs, I.E. A Perspective on the Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) of NO with NH3 by Supported V2O5-WO3/TiO2 Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6537–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xing, Z.; Bao, C.; Liang, G. Preparation and Characterization of CeO2-MoO3/TiO2 Catalysts for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with NH3. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 2726–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Luo, Z.; Cen, K. The Activity and Characterization of CeO2-TiO2 Catalysts Prepared by the Sol-Gel Method for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with NH3. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 174, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, J.; Luo, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Q. Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with NH3 Over Mn-Ti Oxide Catalyst: Effect of the Synthesis Conditions. Catal. Lett. 2021, 151, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Woo, S.I. Novel Mn-Ce-Ti Mixed-Oxide Catalyst for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 14500–14508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellmers, I.; Pérez Vélez, R.; Bentrup, U.; Schwieger, W.; Brückner, A.; Grünert, W. SCR and NO Oxidation over Fe-ZSM-5—The Influence of the Fe Content. Catal. Today 2015, 258, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shangguan, W. Promotion Effect of Tungsten and Iron Co-Addition on the Catalytic Performance of MnOx/TiO2 for NH3-SCR of NOx. Fuel 2017, 210, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, X. Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 over Fe-Mn Mixed-Oxide Catalysts Containing Fe3Mn3O8 Phase. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Li, X.; Sun, W.; Fan, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Qin, M.; Gan, G.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, D. Enhancement of Low-Temperature Catalytic Activity over a Highly Dispersed Fe-Mn/Ti Catalyst for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 10159–10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Peng, J.; Qian, Y.; Sun, Z. Low-Temperature DeNOx Characteristics and Mechanism of the Fe-Doped Modified CeMn Selective Catalytic Reduction Catalyst. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 244, 107704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Li, D.; Li, H.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Ouyang, F.; Guo, M. Improvement of Sulfur and Water Resistance with Fe-Modified S-MnCoCe/Ti/Si Catalyst for Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with NH3. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Ge, C.; Li, T.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Xiong, F.; Dong, L. Promoting N2 Selectivity of CeMnOx Catalyst by Supporting TiO2 in NH3-SCR Reaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 6325–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Bian, C.; Jin, Y.; Pang, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, T. Influence of Calcination Temperature on the Evolution of Fe Species over Fe-SSZ-13 Catalyst for the NH3-SCR of NO. Catal. Today 2022, 388–389, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Tian, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, W.; Yao, X. Promotional Effects of Nb5+ and Fe3+ Co-Doping on Catalytic Performance and SO2 Resistance of MnOx-CeO2 Low-Temperature Denitration Catalyst. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 648, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shen, B.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z. Promotion of Fe and Co Doped Mn-Ce/TiO2 Catalysts for Low Temperature NH3-SCR with SO2 Tolerance. Fuel 2019, 249, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Ren, S.; Guo, R.; Li, C.; You, Y.; Guo, S.; Pan, W. The Promotion Effect of Pr Doping on the Catalytic Performance of MnCeOx Catalysts for Low-Temperature NH3-SCR. Fuel 2024, 357, 129917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Sui, Z.; Chen, H.; Shen, Z.; Wu, X. A Basic Comprehensive Study on Synergetic Effects among the Metal Oxides in CeO2-WO3/TiO2 NH3-SCR Catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 127833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.; Dam, P.; Nguyen, K.; Vuong, T.H.; Le, M.T.; Pham, T.H. Copper-Iron Bimetal Ion-Exchanged SAPO-34 for NH3-SCR of NOx. Catalysts 2020, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Jiao, Q.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Hu, G.; Li, J. Promotion Effect and Mechanism of MnOx Doped CeO2 Nano-Catalyst for NH3-SCR. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 4394–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S. Ce and Zr Modified WO3-TiO2 Catalysts for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx by NH3. Catalysts 2018, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Chen, L.; Dai, Y.; Arandiyan, H.; Xu, J.; Hao, J. Ge, Mn-Doped CeO2-WO3 Catalysts for NH3-SCR of NOx: Effects of SO2 and H2O Regeneration. Catal. Today 2013, 201, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, A.; Wang, Z.; Schwämmle, T.; Ke, J.; Li, X. Novel Fe-W-Ce Mixed Oxide for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 at Low Temperatures. Catalysts 2017, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, G.; Duan, A. Effect of Ce Doping of TiO2 Support on NH3-SCR Activity over V2O5-WO3/CeO2-TiO2 Catalyst. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H.; Li, H.; Shi, L.; Zhang, D. Investigations on the Antimony Promotional Effect on CeO2-WO3/TiO2 for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, D.; Yu, S.; Liu, A.; Dong, L.; Feng, S. Insights into the Sm/Zr Co-Doping Effects on N2 Selectivity and SO2 Resistance of a MnOx-TiO2 Catalyst for the NH3-SCR Reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Liu, F.; He, H.; Shi, X.; Mo, J.; Wu, Z. Manganese-Niobium Mixed Oxide Catalyst for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 at Low Temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 250, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 over Mn-Ce Mixed Oxide Catalyst at Low Temperatures. Catal. Today 2013, 216, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Xiong, W.; Jiang, X.; Ouyang, T.; Bai, Y.; Cai, X.; Cai, J.; Tan, H. A DFT Study of the Mechanism of NH3-SCR NOx Reduction over Mn-Doped and Mn-Ti Co-Doped CoAl2O4 Catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 5073–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.D. Recent Progress on Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with Ammonia. Molecules 2024, 29, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).