Abstract

Photothermal catalysis has emerged as a promising approach for the efficient and cost-effective removal of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Pt@MnO2 catalysts have demonstrated excellent performance in the photothermal catalytic oxidation of VOCs. However, current research has predominantly focused on the interaction between Pt and MnO2, while often overlooking the influence of the MnO2 crystal phase. Therefore, in this study, we synthesized Pt supported on four crystal phases (α, β, γ, and δ) of MnO2 and established the structure–activity relationships through performance evaluation and characterization. Among the prepared catalysts, Pt@Mn[δ] exhibited excellent performance and possessed outstanding stability. Crystal structure characterization revealed that the larger specific surface area and lower crystallinity of Pt@Mn[δ] exposed more active sites. XPS analysis indicated the transformation of Mn4+ to Mn3+ on Pt@Mn[δ], leading to the formation of oxygen vacancies. O2-TPD and H2-TPR further confirmed the activation of lattice oxygen and the promoted redox cycle of Pt@Mn[δ]. UV-Vis DRS and electrochemical measurements demonstrated that Pt@Mn[δ] exhibited the most pronounced visible-light absorption, the highest photocurrent density, the lowest charge transfer resistance and superior charge carrier mobility. TD-GC-MS analysis indicated that o-xylene underwent alkylation and isomerization, with subsequent oxidation following the Mars–van Krevelen (MvK) mechanism.

1. Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a major group air pollutants characterized by their complex composition and diverse emission sources, posing significant adverse effects to both human health and air quality [1,2]. Therefore, it is an urgent task to effectively remove VOCs. In recent years, the development of VOC removal technologies from industrial exhaust gas has attracted considerable attention. Current VOC elimination methods include adsorption, photocatalysis, plasma catalysis, thermal catalysis, and photothermal catalysis [3]. Among them, photothermal catalysis has emerged as a particularly promising approach, with higher efficiency and less energy consumption [4]. Catalysts serve as the core component of photothermal catalysis systems, and their performance directly governs the conversion efficiency of VOC eliminations from exhaust gas [5]. Therefore, substantial research endeavors have focused on developing highly efficient, cost-effective, and durable catalysts.

Over the years, various catalysts have been developed for the photothermal catalytic degradation of VOCs, mainly falling into two categories: transition metal oxides and noble metals such as Pd and Pt [6]. Despite the high efficacy of noble metals in VOC oxidation, their practical application is limited by high cost and scarcity [7]. In contrast, transition metal oxides offer advantages such as low cost, poison resistance, and sintering stability, making them attractive alternatives. However, they generally suffer from lower activity, poorer stability, and higher susceptibility to deactivation in complex atmospheres, restricting their widespread use [8]. To address these limitations, supported noble metal catalysts—where noble metals are dispersed on various supports—have gained increasing attention. The dispersion of noble metal nanoparticles maximizes active sites and enhances synergistic effects with the support, significantly boosting catalytic performance [9]. For example, Li et al. [10] prepared a Pt/[TiN@TiO2] core–shell catalyst that exhibited broadened light absorption and high photothermal efficiency, achieving complete toluene degradation under 500 mW·cm−2 light irradiation. Similarly, Fan et al. [11] developed a Pd/Fe-TiO2 catalyst with dual-active sites, where the incorporation of Pd and Fe promoted charge separation and reactive oxygen species generation, leading to significantly improved toluene degradation.

Supported Pt catalysts are regarded as highly promising for VOC oxidation due to their high activity and stability. In such systems, the Pt–support interface facilitates the formation of Pt0/Ptδ+ active species, which play a key role in enhancing oxidation reactivity and modulating catalyst properties [9]. For instance, Wang et al. [12] developed Pt/N–TiO2–H2, which contained a high proportion of Pt0 and achieved 98.4% toluene conversion under 260 mW·cm−2 light irradiation. The choice of support is crucial in photothermal catalysis. MnO2 has attracted wide interest owing to its broad light absorption from visible to NIR regions and multivalent manganese species, enabling both photocatalytic and thermal catalytic functions [13,14,15]. Yu et al. [16] prepared 1Pt/MO by depositing Pt nanoparticles on MnO2, attaining complete toluene degradation under 200 mW·cm−2 light. Wang et al. [17] further constructed a Pt single-atom catalyst on δ-MnO2, where strong Pt–support electronic interaction activated lattice oxygen and promoted intermediate conversion. Despite these advances, most previous studies have emphasized noble metal–support interactions, while the influence of the support’s intrinsic structure on catalytic performance has often been overlooked. MnO2 consists of [MnO6] octahedra as fundamental building units, can assemble into diverse structural architectures through different connectivity patterns, thereby exhibiting multiple crystal phases [18]. Distinct polymorphs of MnO2 possess markedly different physicochemical properties, suggesting that the structure–activity relationship can substantially modulate catalytic behavior.

Herein, MnO2[α, β, γ, and δ] with different crystalline phases were synthesized via a hydrothermal method. Subsequently, Pt was immobilized onto MnO2 supports using the NaBH4 reduction method, resulting in the formation of Pt@Mn[α], Pt@Mn[β], Pt@Mn[γ], and Pt@Mn[δ] catalysts. A series of characterization techniques were utilized to probe the structural characteristics of the synthesized catalysts. Subsequently, we evaluated the photothermal catalytic activity of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] in the oxidation of o-xylene. The degradation pathway of o-xylene was further elucidated using the thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (TD-GC-MS).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Characterization

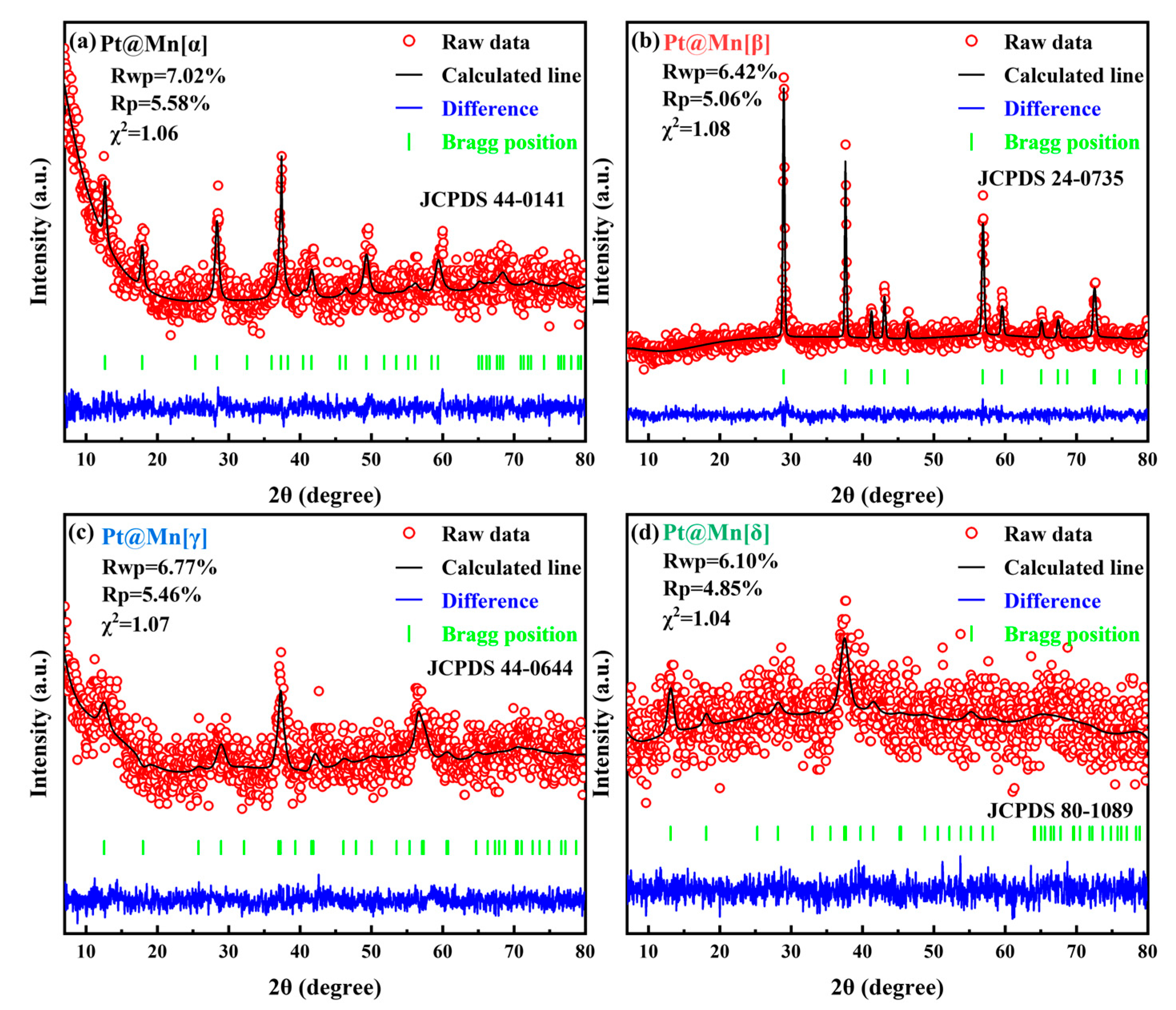

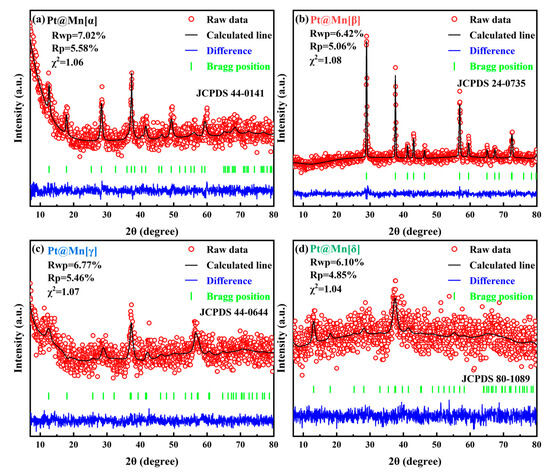

The crystallographic structures of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts with different polymorphs were characterized by XRD, and Rietveld refinement was performed on the obtained patterns. Figure 1 shows that prepared catalysts displayed diffraction patterns attributable only to their specific MnO2 phases [19,20,21,22]. Moerover, the XRD peaks of Pt@Mn[α] were shown at 49.7°, 41.8°, 37.6°, 28.5°, 17.9°, and 12.2°, which can be corresponded to the (411), (301), (211), (310), (200), and (110) planes. The diffraction peaks observed at 66.2°, 37.4°, 25.6°, and 13.1° can be assigned to the (020), (−111), (002), and (001) crystal planes of Pt@Mn[δ]. For Pt@Mn[γ], the peaks observed at 45.6°, 37.2°, and 22.7° correspond to the (300), (131), and (120) planes. Meanwhile, the peaks at 43.1°, 37.6°, and 29.0° were assigned to the (111), (101), and (110) planes of Pt@Mn[β]. This phase purity confirmed that no significant crystal transformation occurred during Pt deposition. In addition, the absence of detectable PtOx diffraction peaks suggested a high dispersion of Pt species on the catalyst surfaces. Notably, Pt@Mn[β] displayed substantially sharper and more intense diffraction peaks compared to Pt@Mn[α], Pt@Mn[γ] and Pt@Mn[δ]. In contrast, the comparatively broad peaks observed for Pt@Mn[δ] indicated poor crystallinity, primarily attributed to synthesis-induced structural defects that generate pronounced disorder along specific crystallographic directions [23]. Then the grain size was calculated from the Full Width at Half Maxima (HWFM) of the major crystallographic plane, as shown in Table 1. The calculated grain sizes followed the order: Pt@Mn[β] (25.6) > Pt@Mn[α] (18.9) > Pt@Mn[γ] (15.1) > Pt@Mn[δ] (10.3). Consequently, Pt@Mn[δ] possessed the smallest grain size, which might due to the formation of surface defect sites [24].

Figure 1.

Rietveld refined XRD patterns for (a) Pt@Mn[α], (b) Pt@Mn[β], (c) Pt@Mn[γ] and (d) Pt@Mn[δ].

Table 1.

Chemical and physical properties of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ].

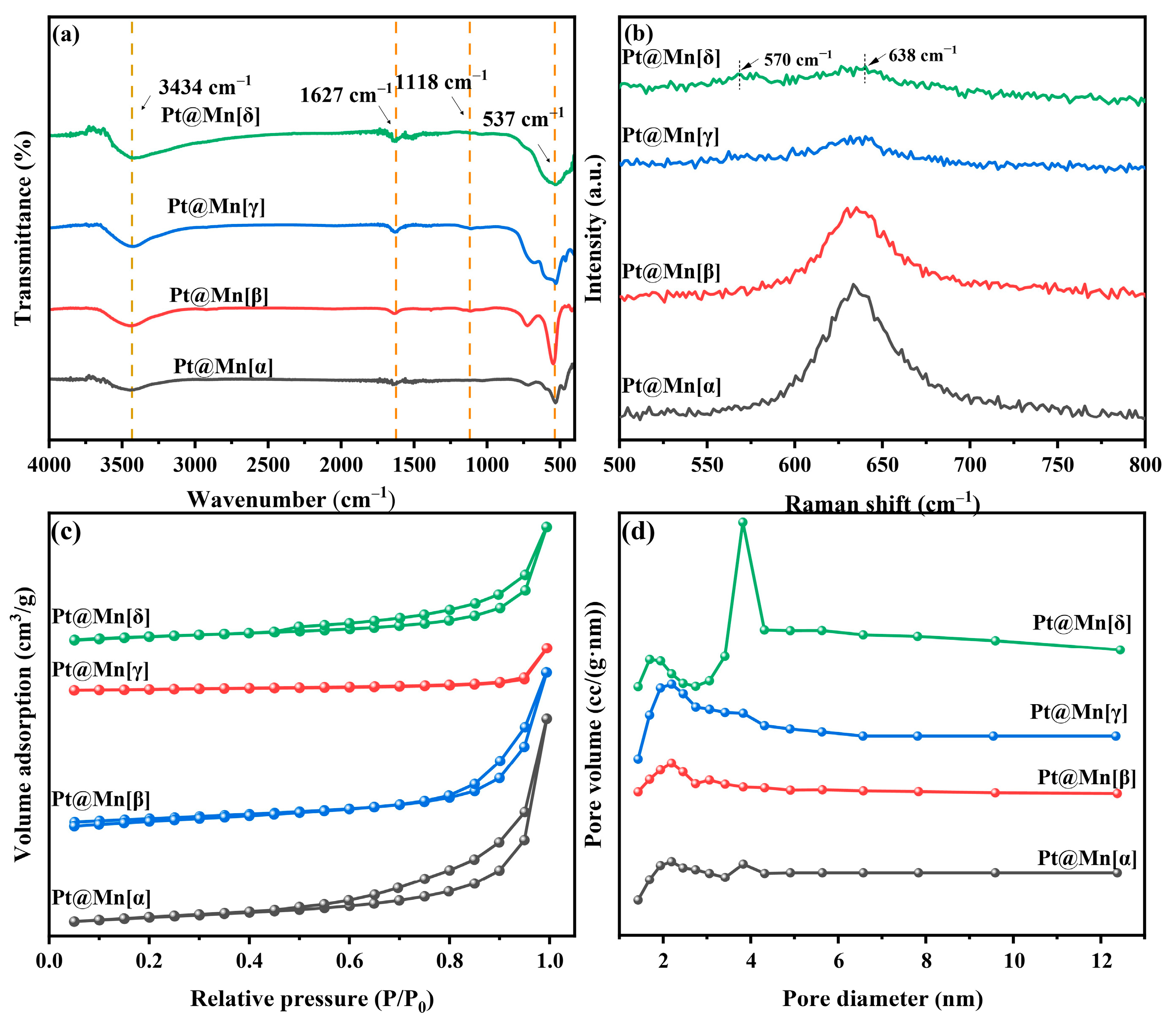

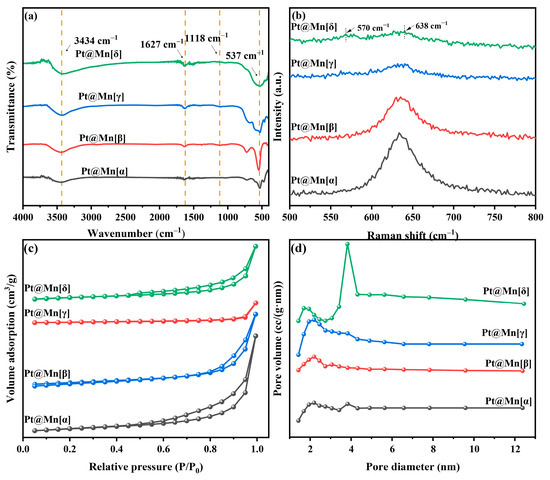

The functional groups on the prepared catalysts were identified by FT-IR spectroscopy, Figure 2a. The observed bands at approximately 3434 cm−1 and 1627 cm−1 are characteristic of O–H stretching and bending vibrations, respectively, indicating the presence of adsorbed water [25]. Furthermore, bands were observed at approximately 1118 cm−1 and 543 cm−1, which were assigned to Mn–O–H coordination and the stretching vibration of Mn–O/Mn–O–Mn, respectively [26]. Among them, the Mn-O bond vibration at 543 cm−1 exhibited the highest intensity for Pt@Mn[β], while it was less intense for Pt@Mn[γ] and Pt@Mn[δ].

Figure 2.

(a) FT-IR spectra, (b) Raman patterns, (c) N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms and (d) pore size distribution curves for Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ].

Raman spectroscopy was employed to elucidate the crystal structures of the prepared catalysts. The observed peaks in the 500–700 cm−1 range were consistent with [MnO6] octahedra vibrations. For Pt@Mn[δ], the spectrum consisted of two primary bands at approximately 570 and 638 cm−1, the latter of which was ascribed to the symmetric stretching vibration of the Mn–O bond [27]. The Raman band at 570 cm−1 was attributed to the in-plane Mn–O stretching vibration of the [MnO6] sheets. Notably, the broad band around 638 cm−1 observed for the prepared catalysts demonstrated that the incorporation of Pt did not change the MnO2 structure [28]. The Raman spectrum of prepared catalysts in Figure 2b exhibited a characteristic band near 638 cm−1, which is attributed to the Mn-O vibration within the [MnO6] octahedral framework. Furthermore, the different crystal phases exhibit distinctive vibrational modes (Pt@Mn[α]: breathing vibrations; Pt@Mn[β]: symmetric stretching vibrations; Pt@Mn[γ]: symmetric stretching vibrations; Pt@Mn[δ]: symmetric stretching vibration). Notably, the Pt@Mn[δ] catalyst exhibited the lowest band intensity among the series, suggesting a lower degree of crystallinity. This observation is consistent with the broader XRD patterns observed for this material (Figure 1), further supporting its relatively disordered structure. Lower crystallinity generally facilitates the exposure of a greater number of active sites, thereby enhancing the catalytic activity [29].

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts are presented in Figure 2c. Pt@Mn[α], Pt@Mn[γ], and Pt@Mn[δ] displayed typical Type IV adsorption–desorption isotherms accompanied by H3-type hysteresis loops, while Pt/β-MnO2 aligned well with a Type III isotherm, also featuring the H3 hysteresis loop. These results collectively indicated the presence of mesoporous structures in all prepared catalysts [30]. The textural properties of the catalysts, including specific surface area, pore size distribution, and average pore size, are listed in Table 1. The BET surface areas varied significantly, ranging from 13.2 m2·g−1 for Pt@Mn[α] to 59.7 m2·g−1 for Pt@Mn[δ]. The adsorption capacity of o-xylene was strongly influenced by the specific surface area, which governed the population of accessible active sites [13]. A correlation was observed between the pore volume and the specific surface area. Figure 2d displayed the corresponding pore size distribution calculated by the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. Conversely, Pt@Mn[δ] and Pt@Mn[γ] exhibited broader pore size distributions with larger average pore diameters, suggesting more heterogeneous pore structures.

2.2. Surface Chemical Properties Analysis

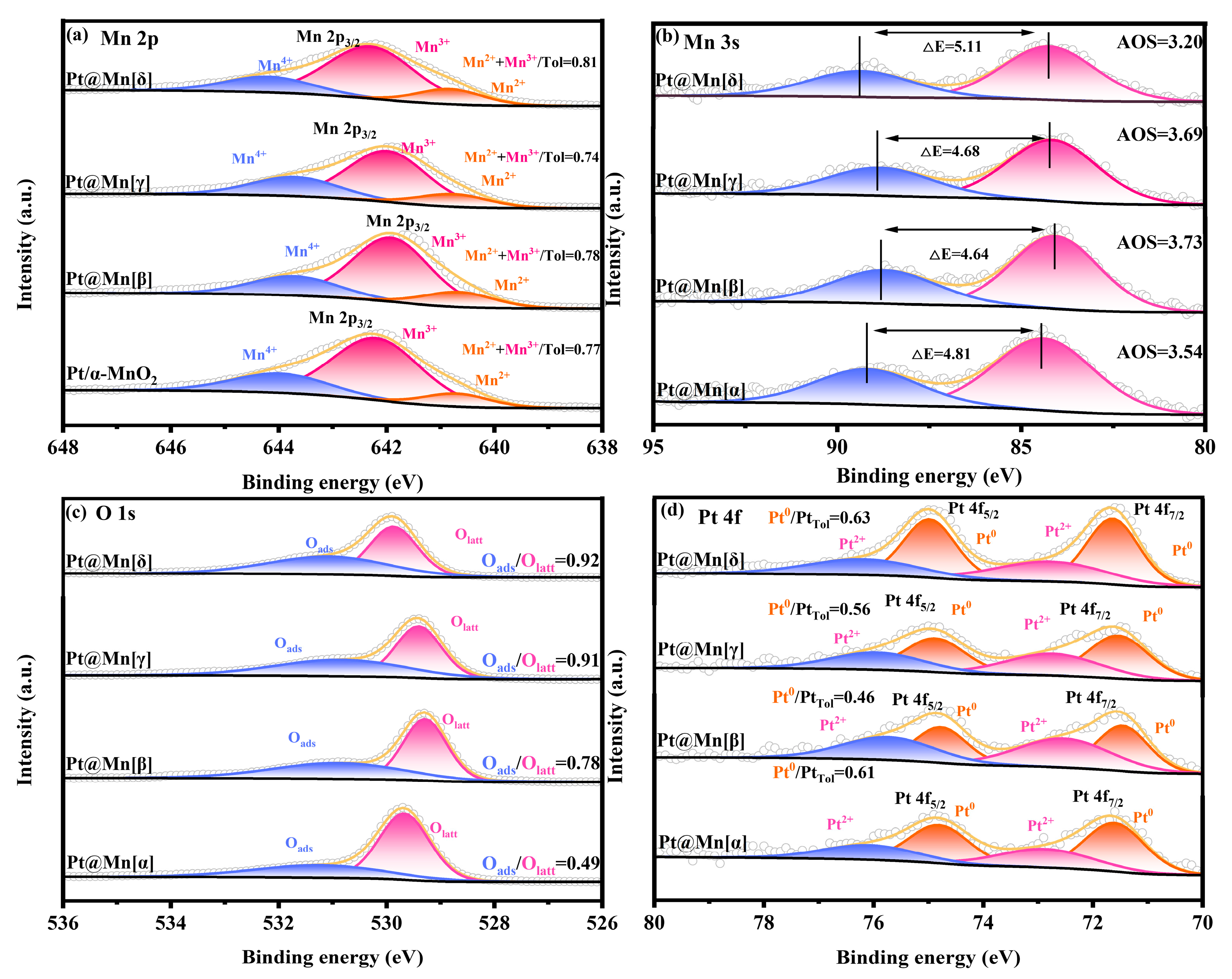

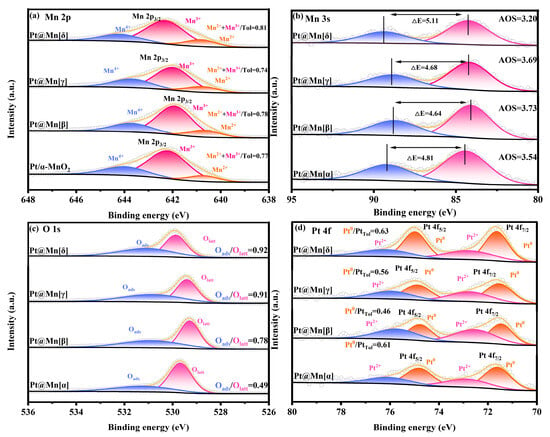

The Mn 2p XPS spectra of the Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts are presented in Figure 3a. Spectral deconvolution revealed three components at binding energies of 642.7 eV, 641.7 eV, and 640.4 eV, corresponding to Mn4+, Mn3+, and Mn2+ species, respectively [31]. The concentrations of low-valent Mn (Mn2+ and Mn3+) in the different catalysts were summarized in Table 1. From Table 1, it can be seen that Pt@Mn[δ] possessed the highest relative concentration of low-valence Mn (Mn2+ and Mn3+), which was 0.81. According to previous studies, the low-valent Mn2+ species and Mn3+ species represent the presence of surface oxygen vacancies in the catalyst, which is due to the need to balance the charge during the process of Mn4+ changing from a high-valent state to a low-valent state [32]. The Mn 3s XPS spectra (Figure 3b) were used to quantify the average oxidation state (AOS) of Mn, providing further evidence for the existence of low-valent Mn species. The calculated average oxidation states (AOS) of the synthesized samples are presented in Table 1. Notably, Pt@Mn[δ] exhibits the lowest AOS with a value of 3.20. This finding aligns with the established mechanistic understanding that the reduction of Mn4+ to lower oxidation states necessitates the generation of oxygen vacancies to maintain charge neutrality. The intrinsic crystal defects and tunnel hybridization in Pt@Mn[δ] were favorable for stabilizing more Mn2+/3+ on the surface, consequently enhancing the formation of oxygen vacancies. The XPS spectra of O 1s of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] samples are shown in Figure 3c. As displayed in Figure 3c, the O 1s XPS spectra of the Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] samples exhibited two peaks at 529.4 eV and 531.1 eV, which were attributed to lattice oxygen (Olatt) and surface-adsorbed oxygen (Oads), respectively [33]. The ratios of Oads/Olatt for four Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] samples were calculated based on the peak areas. Typically, oxygen vacancies serve as active sites on the material surface and exhibit a strong tendency to form Oads, leading to the formation of adsorbed oxygen species. Consequently, higher ratio of Oads/Olatt implies greater concentration of oxygen vacancies [34]. As summarized in Table 1, Pt@Mn[δ] showed the greatest Oads/Olatt proportion (0.92), which indicated a higher concentration of oxygen vacancies in Pt@Mn[δ]. Oxygen vacancies facilitated the activation of gaseous oxygen, promoted the regeneration of lattice oxygen, and accelerated the redox cycle in the Mars–van Krevelen (MvK) mechanism, thereby enhancing the overall catalytic activity [35]. The XPS spectra of Pt 4f orbitals for Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts were presented in Figure 3d, revealing that Pt species primarily exist in metallic Pt0 and oxidized Pt2+ states. The Pt0/Pttotal ratios were presented in Table 1. Quantitative analysis of the catalyst series revealed that the Pt@Mn[δ] catalyst possessed the highest proportion of metallic Pt0, with a Pt0/Pttotal of 0.63. This finding was consistent with previous reports establishing a positive correlation between Pt0 content and catalytic activity [36].

Figure 3.

XPS spectra of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ]: (a) Mn 2p, (b) Mn 3s, (c) O 1s, and (d) Pt 4f.

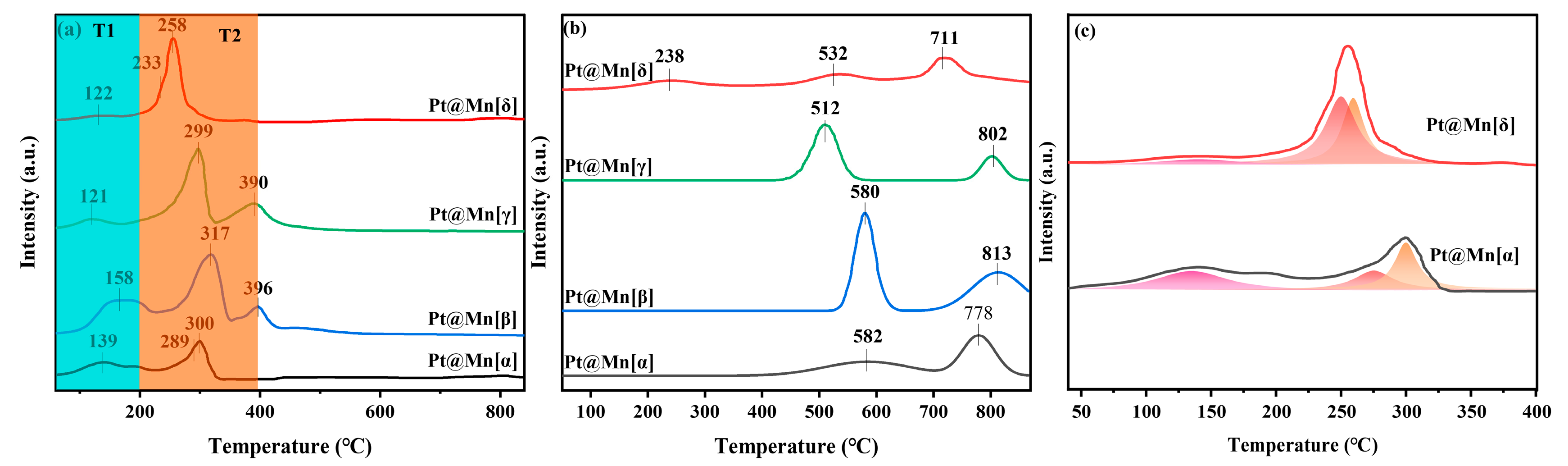

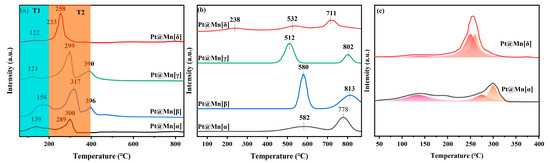

The reducibility of catalysts is crucial to the catalytic performance. Therefore, H2-TPR was employed to characterize the catalysts and is presented in Figure 4a. All catalysts exhibited a similar profile of reduction peaks, which were categorized into a low-temperature peak (T1, 0–200 °C) and a medium-temperature peak (T2, 200–400 °C). The peak in the T1 region was primarily due to the reduction of PtOx, while the peak in the T2 region was primarily due to the stepwise reduction in surface Mn4+ in MnO2. Specifically, the peak in the T1 region arose from the reduction of PtOx to metallic platinum (Pt0), and the broad peak in the T2 region corresponded to the multi-step reduction process of Mn4+ → Mn3+ → Mn2+ [37,38]. A comparison of the peak in the T1 region among the prepared catalysts revealed that Pt@Mn[δ] possessed the smallest peak area, indicating the lowest content of PtOx and the highest proportion of metallic Pt0. This conclusion was consistent with the results obtained from XPS analysis. During the medium-temperature stage, the peak in the T1 region of the prepared catalysts exhibited pronounced differences. For Pt@Mn[δ] and Pt@Mn[α], the overlapping reduction peaks suggested a rapid reduction process of Mn4+ (Figure 4). In contrast, Pt@Mn[β] and Pt@Mn[γ] displayed distinct, separated peaks, clearly indicating a stepwise reduction pathway of Mn4+ proceeding at a comparatively slower rate. Moreover, the peak in the T2 region for Pt@Mn[δ] appeared at a lower temperature compared to those of Pt@Mn[γ], Pt@Mn[β], and Pt@Mn[α], which could be explained by the enhanced hydrogen spillover effect from Pt0 to the MnOx support [9]. Specifically, the high concentration of metallic Pt0 on Pt@Mn[δ] facilitated the dissociation of H2 into active hydrogen species (H·), which acted as potent reducing agents to reduce Mn4+ via the metal–support interface. These results demonstrated that Pt@Mn[δ] demonstrated the greatest reducing capability among all synthesized samples.

Figure 4.

(a) H2-TPR, (b) O2-TPD profile of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ], and (c) deconvolution analysis on the overlapping H2-TPR peaks of Pt@Mn[α] and Pt@Mn[δ].

The oxidative activity of catalysts is directly related to the amount and reactivity of the active oxygen species. Hence, the Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] samples were characterized by O2-TPD and are shown in Figure 4b. For the catalytic oxidation of VOCs, researchers have focused on the peaks below 600 °C [16]. Therefore, the oxygen species with desorption temperatures below 600 °C are the primary contributors to the catalytic process [39,40]. Specifically, the peak below 300 °C was attributed to the desorption of oxygen molecule anions (O2−) adsorbed on oxygen vacancies, while the peak between 300 and 600 °C was attributed to the desorption of oxygen anions (O−) in the lattice oxygen. Observing the desorption peaks, it was found that Pt@Mn[δ] was significantly different from the other three catalysts. This indicated that there were differences in the oxygen species characteristics among different crystal forms of MnO2. Specifically, Pt@Mn[δ] had a distinct broad peak at 238 °C, indicating that the oxygen species adsorbed on oxygen vacancies on the Pt@Mn[δ] surface participate in the catalytic process at a lower temperature [6]. However, no desorption peaks were observed in this temperature range for Pt@Mn[α], Pt@Mn[β], and Pt@Mn[γ] catalysts, suggesting their poorer oxidation ability. Additionally, desorption peaks were observed for all prepared catalysts between 300 and 600 °C, indicating that lattice oxygen also participated in the reaction.

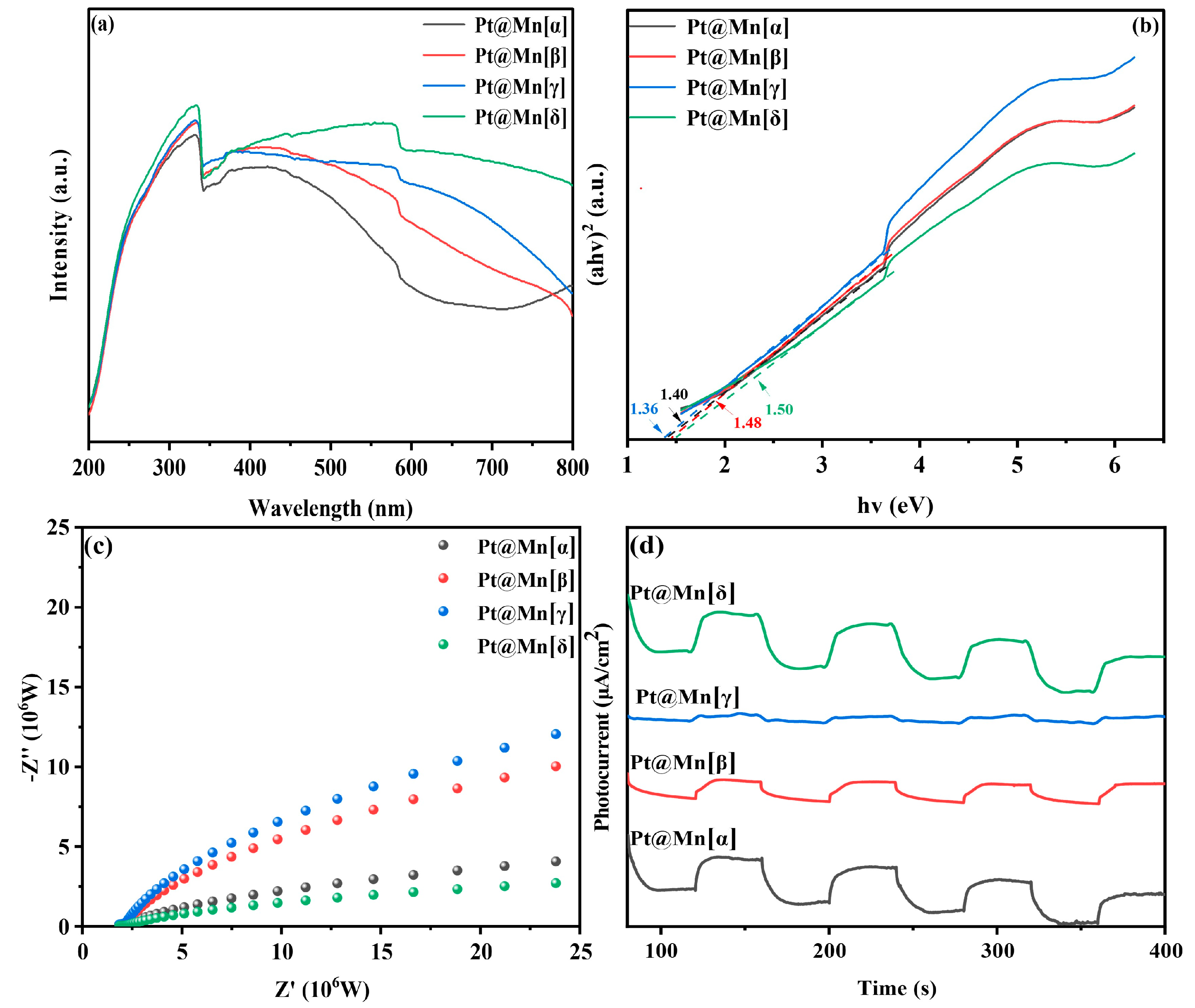

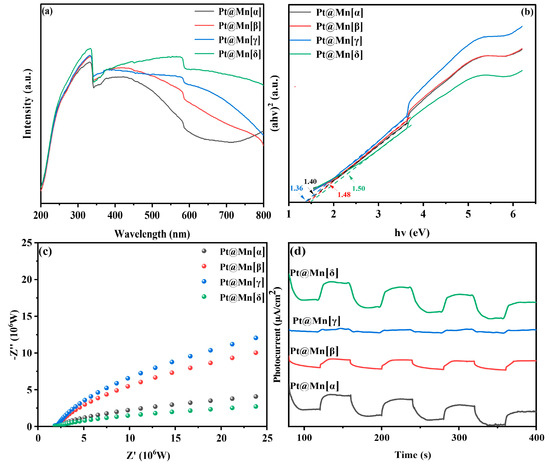

2.3. Detection of Optical Properties

The light absorption characteristics of catalytic materials play a crucial role in determining their photothermal catalytic performance. The optical properties of the Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts were studied using UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS). As shown in Figure 5a, all catalysts exhibited strong broadband absorption across the entire measured spectral range, which can be attributed to their intrinsic black coloration. Notably, the Pt@Mn[δ] exhibited significantly enhanced light absorption capabilities across both ultraviolet and visible spectral regions compared to other catalysts. The optical band gaps (Eg) of the catalysts were determined using Tauc plot analysis of the absorbance data (Figure 5b). The calculated Eg values followed the order Pt@Mn[δ] (1.50 eV) > Pt@Mn[β] (1.48 eV) > Pt@Mn[α] (1.40 eV) > Pt@Mn[γ] (1.36 eV). To evaluate the charge carrier dynamics, we conducted photocurrent and electrochemical impedance (EIS) measurements The photocurrent response (Figure 5c) revealed the following trend in photoinduced electron density: Pt@Mn[γ] > Pt@Mn[β] > Pt@Mn[α] > Pt@Mn[δ]. Notably, Pt@Mn[δ] exhibited a significantly enhanced photocurrent response compared to other catalysts, suggesting that Pt incorporation effectively suppressed the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs [41,42]. The EIS results (Figure 5d) demonstrated good correlation with the photocurrent measurements. The Nyquist plots showed that Pt@Mn[δ] possessed the smallest arc radius, indicating the lowest charge transfer resistance among the tested catalysts and superior charge carrier mobility with minimized recombination losses [43,44]. These characteristics collectively contribute to the enhanced photocatalytic performance observed for Pt@Mn[δ].

Figure 5.

(a) UV-vis DRS spectra; (b) Tauc plot; (c) EIS plots; and (d) photocurrents of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ].

2.4. Catalytic Activity

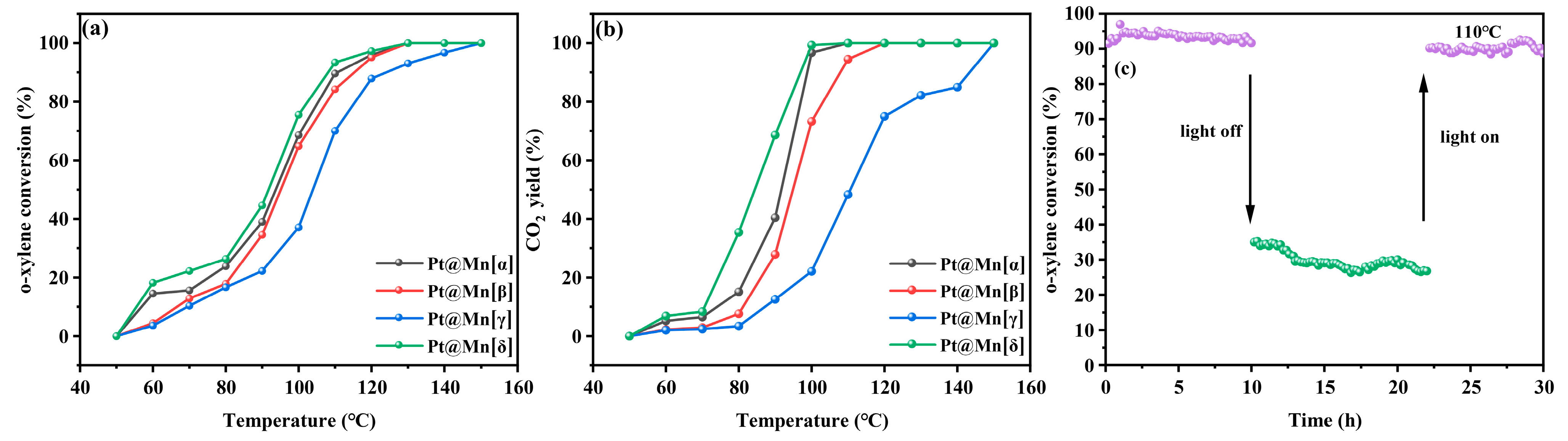

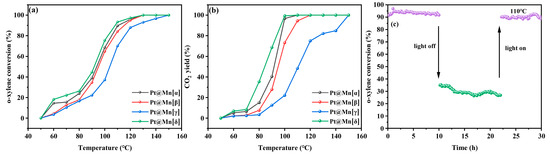

As shown in Figure 6a, the o-xylene oxidation conversion over the Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts remained below 30% at temperatures under 80 °C. The conversion of o-xylene increased rapidly once the reaction temperature exceeded 80 °C. Complete o-xylene degradation was achieved over Pt@Mn[α] at 147 °C, Pt@Mn[β] at 149 °C, Pt@Mn[γ] at 150 °C, and Pt@Mn[δ] at 145 °C. The catalytic activity followed the order: Pt@Mn[δ] > Pt@Mn[α] > Pt@Mn[β] > Pt@Mn[γ], with Pt@Mn[δ] exhibiting the highest performance. For quantitative comparison, Table 2 summarized the characteristic temperatures required to achieve 10%, 50%, and 90% o-xylene conversion (T10, T50, and T90). T10, T50, and T90 values exhibited the same trend—Pt@Mn[δ] < Pt@Mn[α] < Pt@Mn[β] < Pt@Mn[γ] —confirming the superior low-temperature activity of Pt@Mn[δ]. These results clearly demonstrate that Pt@Mn[δ] possesses exceptional catalytic performance for the complete oxidation of o-xylene. In addition, the CO2 yield at equivalent reaction temperature was evaluated, as presented in Figure 6b. At 80 °C, the Pt@Mn[δ], Pt@Mn[α], Pt@Mn[β], and Pt@Mn[γ] catalysts yielded CO2 at rates of 39%, 27%, 8%, and 4%, respectively. Although the CO2 yield progressively increased with rising temperature, the activity sequence remained unchanged throughout the tested range. To further investigate the stability of the Pt@Mn[δ] catalyst, photothermal tests were conducted at 110 °C under simulated sunlight illumination. As presented in Figure 6c, the o-xylene conversion exhibited excellent stability during the initial 10 h illumination period, decreasing only slightly from 93% to 90%. However, when the light source was removed, the conversion dropped significantly to approximately 20%. After maintaining this dark condition for 10 h, the light was reintroduced, and the o-xylene conversion promptly recovered to 90% with subsequent stable performance. These results clearly demonstrated that the Pt@Mn[δ] catalyst maintains exceptional stability under photothermal catalytic conditions, with its activity being light-dependent and fully reversible.

Figure 6.

(a) o-xylene conversion and (b) CO2 yield of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] and (c) stability of Pt@Mn[δ].

Table 2.

Catalytic performance of Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ].

2.5. Intermediates and Reaction Mechanism

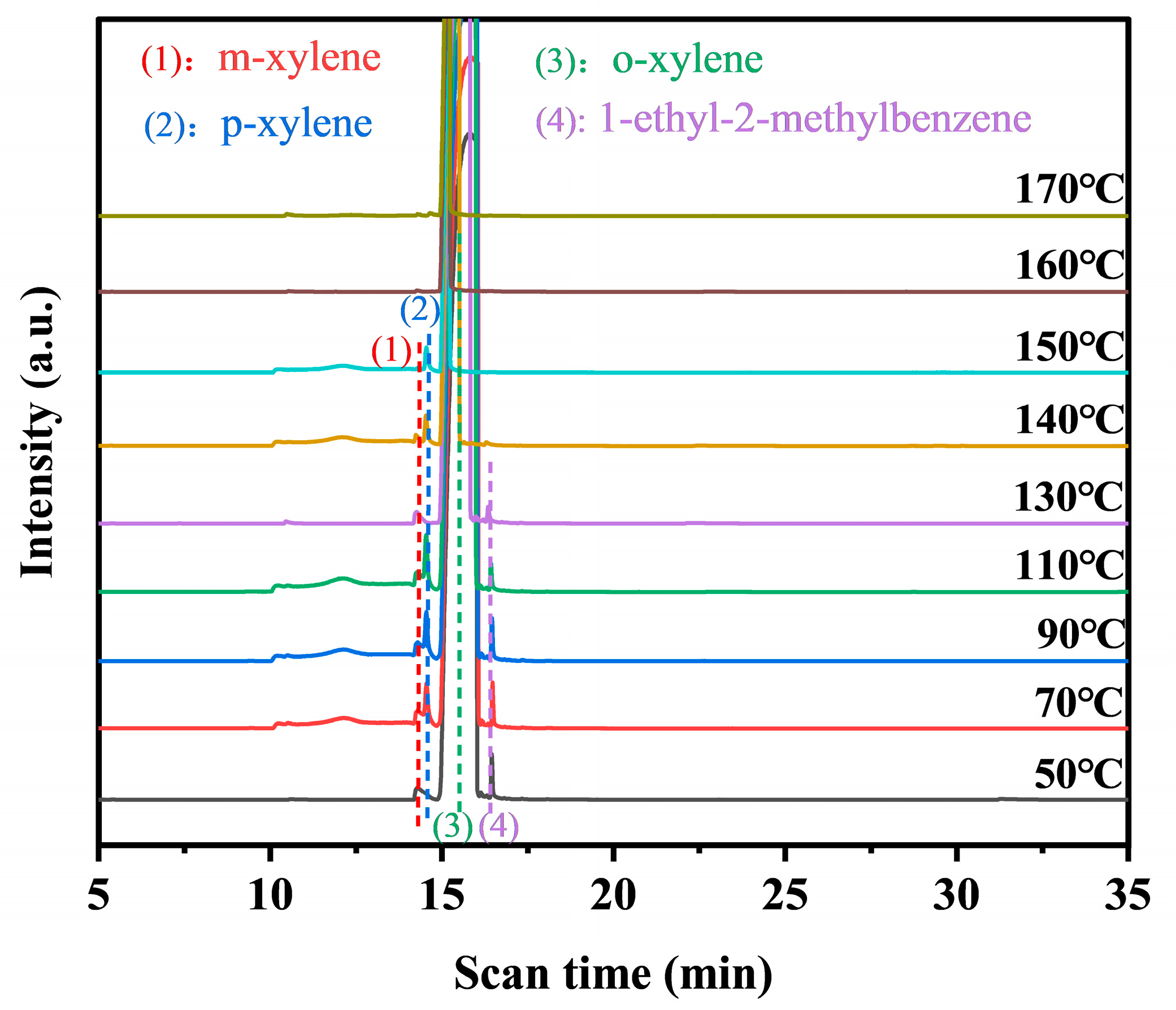

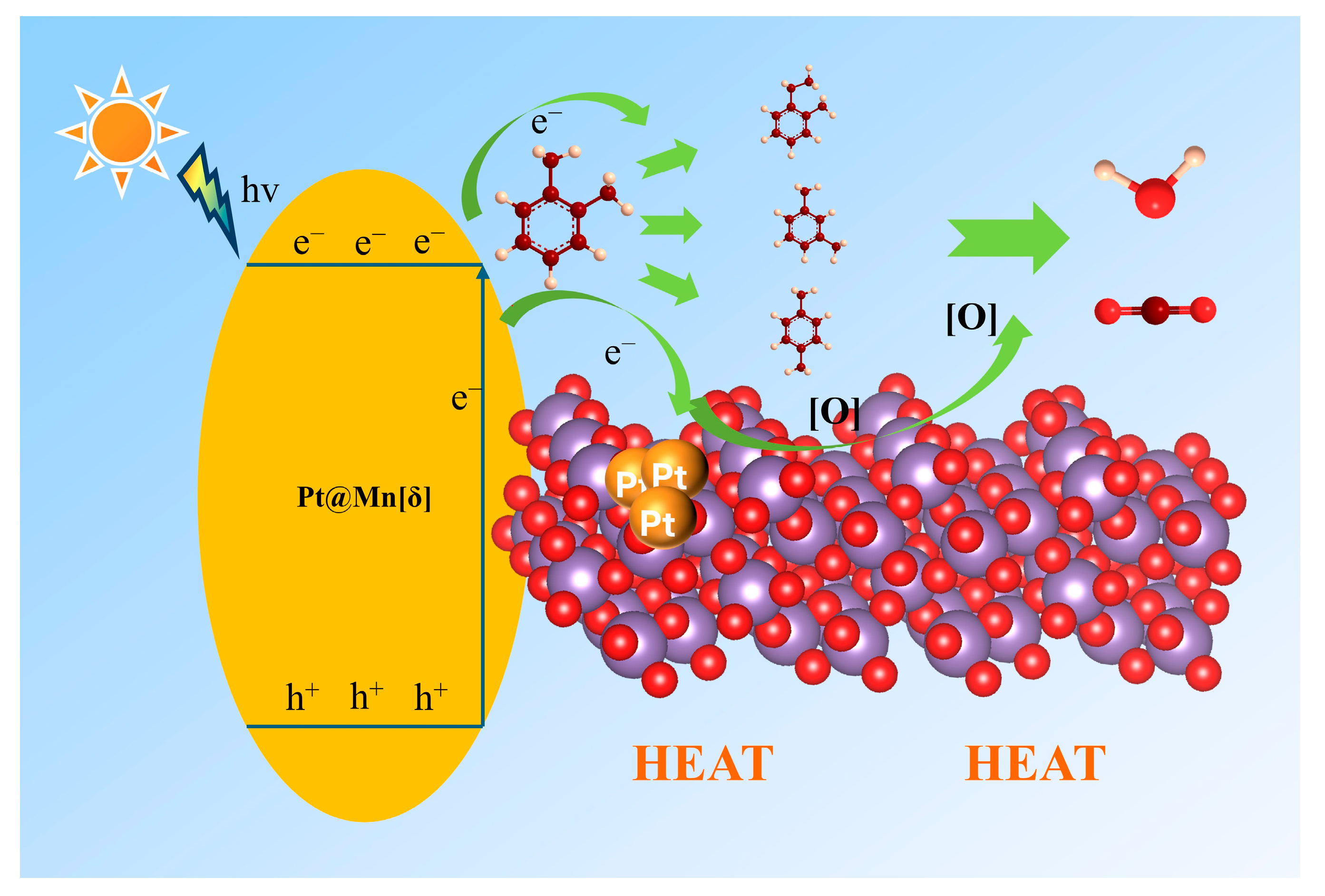

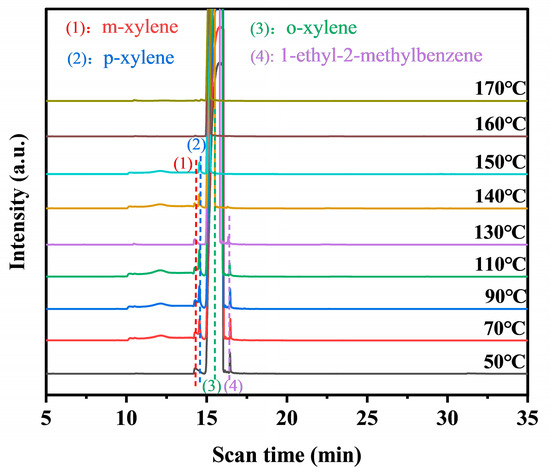

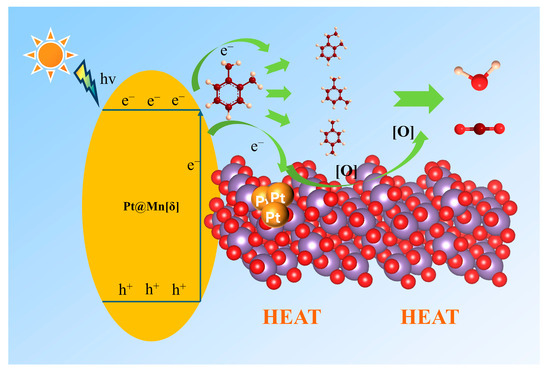

The intermediates formed during the photothermal catalysis oxidation of o-xylene on Pt@Mn[δ] were identified by TD-GC-MS (Figure 7). Three probable intermediates were detected: m-xylene, p-xylene, and 1-ethyl-2-methylbenzene. The formation of m- and p-xylene was attributed to acid-catalyzed isomerization (Friedel––Crafts reaction), proceeding via intramolecular or intermolecular methyl shifts, followed by protonation–deprotonation prior to desorption. In addition, 1-ethyl-2-toluene was produced by the alkylation of o-xylene [45]. Based on the experimental findings, a potential photothermal synergistic mechanism was illustrated in Figure 8. The process initiated with oxygen activation, wherein O2 molecules acquired electrons from the catalyst surface to form active oxygen species. Subsequently, MnO2 compensated for electron loss by extracting electrons from adsorbed o-xylene or reaction intermediates. As electron transfer kinetics were thermally enhanced, elevated temperatures facilitated more efficient activation. Additionally, increased temperature improved surface oxygen mobility, promoting the transfer of proton-activated oxygen species, thereby accelerating the overall reaction process. Consequently, the probable degradation pathway of o-xylene proceeded primarily through intermediates such as m-xylene, p-xylene, and 1-ethyl-2-methylbenzene, ultimately leading to complete mineralization into CO2 and H2O.

Figure 7.

TD-GC-MS of Pt@Mn[δ] under photothermal catalysis.

Figure 8.

Schematic reaction mechanism under photothermal catalysis.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

KMnO4 (A.R.), MnSO4·H2O (A.R.) and H2PtCl6·6H2O were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). (NH4)2S2O8 (A.R.) was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

3.2. Catalysts Preparation

α-, β-, γ-, and δ-MnO2 were synthesized by the hydrothermal method. The specific polymorph of MnO2 was determined primarily by the selection of the precursor and tailored through precise control of the hydrothermal temperature. Pt was immobilized onto MnO2 supports using the NaBH4 reduction method, resulting in the formation of Pt@Mn[α], Pt@Mn[β], Pt@Mn[γ], and Pt@Mn[δ] catalysts. The comprehensive experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information.

3.3. Structural Characterization

The prepared catalysts were characterized through multiple experiments such as X-ray diffraction (XRD, Billerica, MA, USA), Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR, Waltham, MA, USA), Raman spectroscopy (Kyoto, Japan), N2 adsorption–desorption experiment (Boynton Beach, FL, USA), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Waltham, MA, USA), the solid-state UV-Vis spectroscopy, electrochemical measurements, hydrogen programmed-temperature reduction (H2-TPR, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) test, the oxygen programmed-temperature desorption (O2-TPD, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) test and thermal desorption–gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (TD-GC-MS, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Comprehensive experimental details can be found in the Supporting Information.

3.4. Catalytic Reaction

The catalytic performance was assessed in a quartz microreactor. The reaction system contained o-xylene at 300 ppm and oxygen at 21%, along with an optical density of 297.3 mW·cm−2. The detailed process could be found in the Supporting Information.

4. Conclusions

In this work, four Pt@Mn[α, β, γ, and δ] catalysts with distinct crystal phases were synthesized via hydrothermal treatment followed by NaBH4 reduction. Multiple characterization techniques confirmed that Pt@Mn[δ] had the largest specific surface area, the smallest grain size, the highest oxygen vacancies, and superior low-temperature redox properties. Furthermore, the Pt@Mn[δ] catalyst exhibited the most efficient photogenerated carrier separation, the strongest photoresponse capability, and the broadest light absorption range among all preparedd samples. These advantages resulted in the excellent photothermal performance of Pt@Mn[δ] in o-xylene oxidation. The probable degradation of o-xylene proceeded through a pathway that primarily involved the following steps: o-xylene → 1-ethyl-2-methylbenzene, p-xylene and m-xylene → CO2 and H2O.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules30214193/s1, Ref. [46] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

R.Q.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, and Formal analysis; Y.W.: Investigation and Visualization; J.C.: Investigation, Resources, and Supervision; H.H.: Project administration; J.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, and Supervision; Y.Z.: Data curation; F.B.: Funding acquisition and Visualization, X.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, and Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22506124 and 12175145) and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (24YF2729800).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the sponsor of Energy Science and Technology discipline under the Shanghai Class IV Peak Disciplinary Development Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, H.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of Residual Ions on Catalyst Structure and Catalytic Performance: A Review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Feng, X.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; et al. Unveiling the Influence Mechanism of Impurity Gases on Cl-Containing Byproducts Formation during VOC Catalytic Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15526–15537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Wei, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. Insight into the Synergistic Effect of Binary Nonmetallic Codoped Co3O4 Catalysts for Efficient Ethyl Acetate Degradation under Humid Conditions. JACS Au 2025, 5, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bi, F.; Wei, J.; Han, X.; Gao, B.; Qiao, R.; Xu, J.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X. Boosting the Photothermal Oxidation of Multicomponent VOCs in Humid Conditions: Synergistic Mechanism of Mn and K in Different Oxygen Activation Pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11341–11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chu, P.; Hou, Z.; Wu, L.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Dai, H. Single-Atom Catalysts in the Photothermal Catalysis: Fundamentals, Mechanisms, and Applications in VOCs Oxidation. Chem. Synth. 2025, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Qu, Z.; Dong, C.; Qin, Y. Enhancement of toluene oxidation performance over Pt/MnO2@Mn3O4 catalyst with unique interfacial structure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 503, 144161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Gao, X.; Fan, Q.; Gao, X. Facial Controlled Synthesis of Pt/MnO2 Catalysts with High Efficiency for VOCs Combustion. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 16547–16556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhu, D.; Di, S.; Xu, L.; Wu, Z.; Yao, S. Construction of Pt-MnO2 Interface with Strong Electron Coupling Effect for Plasma Catalytic Oxidation of Aromatic VOCs. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 665, 131248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z.; Wen, X.; Mo, S.; Zhang, Q.; Mo, D. Regulating the Surface Local Environment of MnO2 Materials via Metal-Support Interaction in Pt/MnO2 Hetero-Catalysts for Boosting Methanol Oxidation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 281, 119079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chong, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Chen, G.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. A Dual Plasmonic Core—Shell Pt/[TiN@TiO2] Catalyst for Enhanced Photothermal Synergistic Catalytic Activity of VOCs Abatement. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 7071–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Luo, S.; Wang, Y.; Yue, X.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, X.; Dai, W. TiO2-Based Pd/Fe Bimetallic Modification for the Efficient Photothermal Catalytic Degradation of Toluene: The Synergistic Effect of ∙O2– and ∙OH Species. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; et al. Boosting Photothermocatalytic Oxidation of Toluene Over Pt/N-TiO2: The Gear Effect of Light and Heat. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 7662–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zou, T.; Jing, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, F.; Jiang, G. Ni-Doped α-MnO2 Catalyst for Photothermal Synergistic Oxidation of Propane: Investigation of Catalytic Activity and Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bi, Y.; Ji, G.; Jing, Y.; Zhao, J.; Sun, E.; Wang, Y.; Chang, H.; Liu, F. Acid-Activated α-MnO2 for Photothermal Co-Catalytic Oxidative Degradation of Propane: Activity and Reaction Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Ji, G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, E.; Feng, C.; Han, F.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y. In-Situ Modulation of α-MnO2 Surface Oxygen Vacancies for Photothermal Catalytic Oxidation of Propane: Insights into Activity and Synergistic Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Hong, Z.; Jia, H. Enhanced Photothermal Catalytic Degradation of Toluene by Loading Pt Nanoparticles on Manganese Oxide: Photoactivation of Lattice Oxygen. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, M.; Qi, F.; Jin, X.; Zhang, L. Enhanced Toluene Oxidation by Photothermal Synergetic Catalysis on Manganese Oxide Embedded with Pt Single-Atoms. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 636, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J. Photocatalytic Degradation of NO by MnO2 Catalyst: The Decisive Relationship between Crystal Phase, Morphology and Activity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, D.; Rath, C. Structural, Optical and Magnetic Properties of α- and β-MnO2 Nanorods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 557, 149693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Mei, J.; Quan, F.; Yan, N. Different Crystal-Forms of One-Dimensional MnO2 Nanomaterials for the Catalytic Oxidation and Adsorption of Elemental Mercury. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Qu, Z.; Dong, C.; Qin, Y.; Duan, X. Superior Performance of A@β-MnO2 for the Toluene Oxidation: Active Interface and Oxygen Vacancy. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2018, 560, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Bi, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Xin, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, F.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Urea-H2O2 Defect Engineering of δ-MnO2 for Propane Photothermal Oxidation: Structure-Activity Relationship and Synergetic Mechanism Determination. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 641, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Su, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, W.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. Comparative Study of α-, β-, γ- and δ-MnO2 on Toluene Oxidation: Oxygen Vacancies and Reaction Intermediates. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 260, 118150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhuge, X.; Wang, Y.; Du, K. Mn-Ce Solid Solution Growth on Mn2O3 Surface to Form Heterostructure Catalysts with Multiple Active Sites for Toluene Degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Yuan, J.; Hao, H.; Ji, Z.; Liu, M.; Hou, S. The Exploration of a New Adsorbent as MnO2 Modified Expanded Graphite. Mater. Lett. 2013, 110, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, A.K.; Ayele, D.W.; Habtu, N.G.; Teshager, M.A.; Workineh, Z.G. Enhancing Oxygen Reduction Reaction Activity of ε-MnO2 Nanoparticles via Iron Doping. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 157, 110207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Fjellvåg, H.; Norby, P. A Comparison Study on Raman Scattering Properties of α- and β-MnO2. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 648, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z. In-Plasma Catalytic Degradation of Toluene over Different MnO2 Polymorphs and Study of Reaction Mechanism. Chin. J. Catal. 2017, 38, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Su, S.; Yin, H.; Zhang, S.; Isimjan, T.T.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Cai, D. Precise Anchoring of Fe Sites by Regulating Crystallinity of Novel Binuclear Ni-MOF for Revealing Mechanism of Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution. Small 2024, 20, 2306085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Zong, R.L.; Zhu, Y.F. Enhanced MnO2 Nanorods to CO and Volatile Organic Compounds Oxidative Activity by Platinum Nanoparticles. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2012, 28, 437–444. [Google Scholar]

- Ndayiragije, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, N.; Majima, T.; Zhu, L. Mechanochemically Tailoring Oxygen Vacancies of MnO2 for Efficient Degradation of Tetrabromobisphenol A with Peroxymonosulfate. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2022, 307, 121168. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Wei, G.; Wang, L.; Yao, W.; Yang, X.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Z.; Lu, J.; Kang, Z.; Yao, Y. Low-temperature catalytic oxidation of ethyl acetate over MnO2–CeOx composite catalysts: Structure–activity relationship and empirical modeling. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Qu, Z. Layer MnO2 with oxygen vacancy for improved toluene oxidation activity. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 22, 100897. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhuge, X.; Wang, Z. Tailoring Oxygen Vacancies by Synergy of Dual Metal Cations in LaCo0.8M0.2O3 (M = Cu, Ni, Fe, Mn) towards Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, B.; Tang, Y.; Ju, J.; Guo, M. Enhanced Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene over Manganese-Based Multi-Metal Oxides Synthesized by Ozone Driving Redox Reaction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 300, 121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qin, L.; Xiao, W.; Zeng, C.; Li, N.; Lv, T.; Zhu, H. Oriented Growth of Layered-MnO2 Nanosheets over α-MnO2 Nanotubes for Enhanced Room-Temperature HCHO Oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 207, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, L.; Wu, R.; Song, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, G.; He, H. Activity Enhancement of Pt/MnOx Catalyst by Novel β-MnO2 for Low-Temperature CO Oxidation: Study of the CO–O2 Competitive Adsorption and Active Oxygen Species. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Tan, W.; Ji, J.; Cai, Y.; Tong, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Wan, H.; Dong, L. Thermal-Driven Optimization of the Strong Metal–Support Interaction of a Platinum–Manganese Oxide Octahedral Molecular Sieve to Promote Toluene Oxidation: Effect of the Interface Pt2+–Ov–Mnδ+. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 56790–56800. [Google Scholar]

- Andana, T.; Piumetti, M.; Bensaid, S.; Veyre, L.; Thieuleux, C.; Russo, N.; Fino, D.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Pirone, R. CuO Nanoparticles Supported by Ceria for NOx-Assisted Soot Oxidation: Insight into Catalytic Activity and Sintering. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 216, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Song, W.; Ji, J.; Zou, W.; Sun, J.; Tang, C.; Xu, B.; Dong, L. The Construction of MnOx with Rich Oxygen Vacancy for Robust Low-Temperature Denitration. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 6, 100227. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Dong, S.; Bian, Z. Enhancing the Photocatalytic Removal of Toluene by Modified Porous TiO2 with Internal Hydrophobic Interface. Environ. Funct. Mater. 2023, 2, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.-H.; Xu, B.-R.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, H.; Luo, S.-C.; Duan, R.-H.; Li, H.; Yan, X.-Q.; Lin, B.; Yang, G.-D. AuAg Plasmonic Nanoalloys with Asymmetric Charge Distribution on CeO2 Nanorods for Selective Photocatalytic CO2-to-CH4 Conversion. cMat 2024, 1, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Fan, G.; Luo, J.; Cai, C.; Cao, X.; Xu, K.-Q. Synergistic Piezoelectric Effect and Oxygen Vacancies in MoS2/BiOIO3 Heterojunctions Boosting Photocatalytic Degradation of 17β-Estradiol. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 166094. [Google Scholar]

- Di, J.; Liu, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.-S.; Wang, S.-W.; Jiang, W.; Li, H.-M.; Xia, J.-X. In Situ N-Doped Bi3O4Br/(BiO)2CO3 Ultrathin Nanojunctions with Matched Energy Band Structure for Nonselective Photocatalysis Pollutant Removal. cMat 2024, 1, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Jia, H. Combined Effects of Pt Nanoparticles and Oxygen Vacancies to Promote Photothermal Catalytic Degradation of Toluene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 449, 131041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; He, H. Catalytic Oxidation of Formaldehyde over Manganese Oxides with Different Crystal Structures. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).