Abstract

Members of the Pinus genus are well known for their medicinal properties, which can be attributed to their essential oils. In this work, we have examined the leaf essential oils of five understudied Pinus species collected from various locations in western North America. The essential oils were obtained by hydrodistillation and analyzed by gas chromatographic methods, including enantioselective gas chromatography. Pinus albicaulis was dominated by (+)-δ-3-carene; Pinus flexilis was dominated by α-pinene (mostly (+)-α-pinene) and (−)-β-pinene; Pinus lambertiana was dominated by (−)-β-pinene; Pinus monticola was dominated by (−)-β-pinene, (+)-δ-3-carene, and (−)-α-pinene; and Pinus sabiniana was rich in (−)-α-pinene and limonene. While this work adds to our knowledge of Pinus essential oils, additional research is needed to more fully appreciate the geographic and altitudinal variations in the volatile compositions of these Pinus species.

1. Introduction

The genus Pinus L. is composed of around 134 species, distributed throughout the northern hemisphere, and introduced to several locations in the southern hemisphere [1]. Members of the Pinus genus are valued for their medicinal properties [2,3,4], which can be largely attributed to their essential oils. Common components in pine essential oils include α-pinene, β-pinene, myrcene, δ-3-carene, camphene, limonene, and β-phellandrene, among others [2]. In this study, several unstudied or understudied Pinus species from western North America have been obtained and analyzed using gas chromatographic methods.

Pinus albicaulis Engelm. (whitebark pine) is an evergreen monoecious tree found in Alpine habitats in western North America, including the Cascade, Rocky Mountain, and Sierra Nevada ranges (Figure 1) [5]. The trees grow up to 21 m tall, the bark is gray, and the leaves (needles) are five per fascicle (Figure 2). Whitebark pine is considered to be a keystone species, providing food for birds and mammals, slowing snowmelt runoff, and reducing soil erosion. Whitebark pine has co-evolved with Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana (A. Wilson)), which disperse the seeds of the tree [6]. Unfortunately, the population of this tree species has been declining at an alarming rate due to the invasive pathogen Cronarium ribicola J.C. Fisch., which causes blister rust, large-scale outbreaks of the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins), altered fire regimes from fire exclusion, and more frequent and severe fires due to climate change [7,8]. Whitebark pine deaths have increased from 43% to 54% from 2010 to 2019 [9]. Whitebark pine has recently (2022) been classified by the Endangered Species Act as a “threatened species” [10]. As far as we are aware, there have been no previous reports on the essential oil composition of P. albicaulis; identification of the volatile phytochemicals in whitebark pine may be useful in identifying potential bark beetle repellents or antifungal agents.

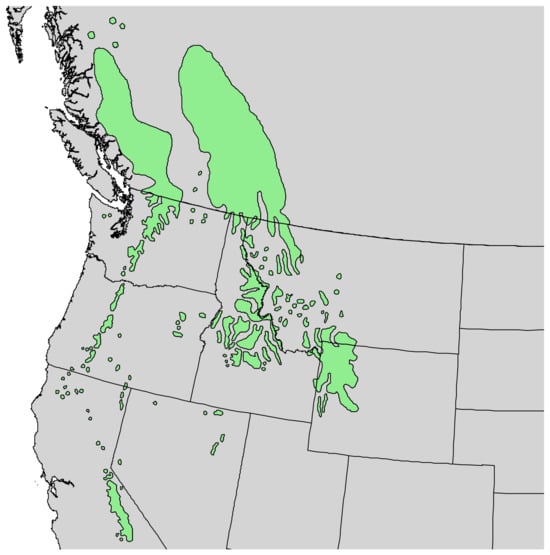

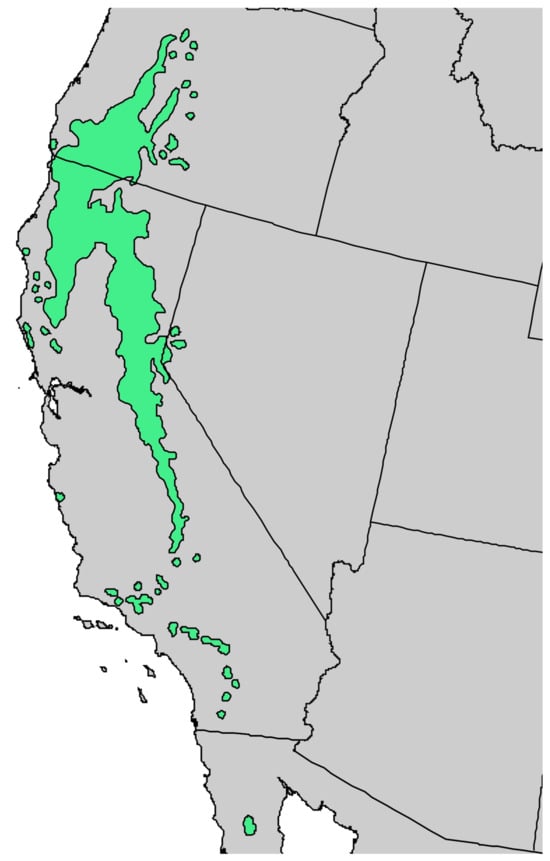

Figure 1.

Range of Pinus albicaulis Engelm. [11].

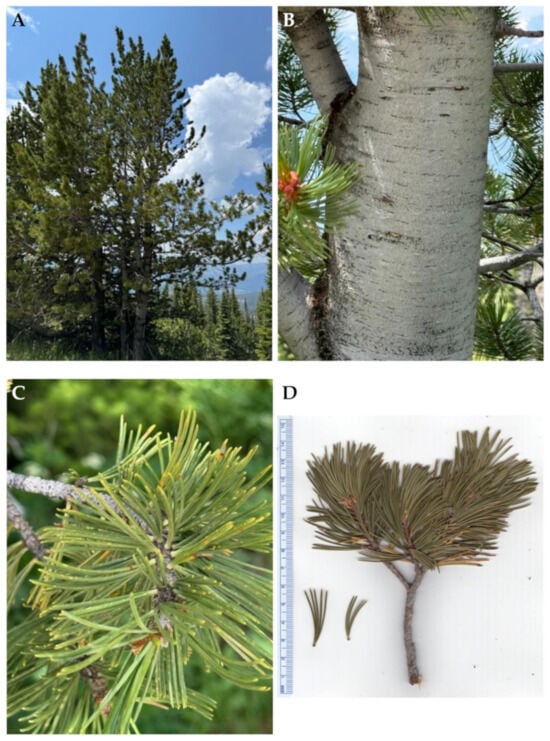

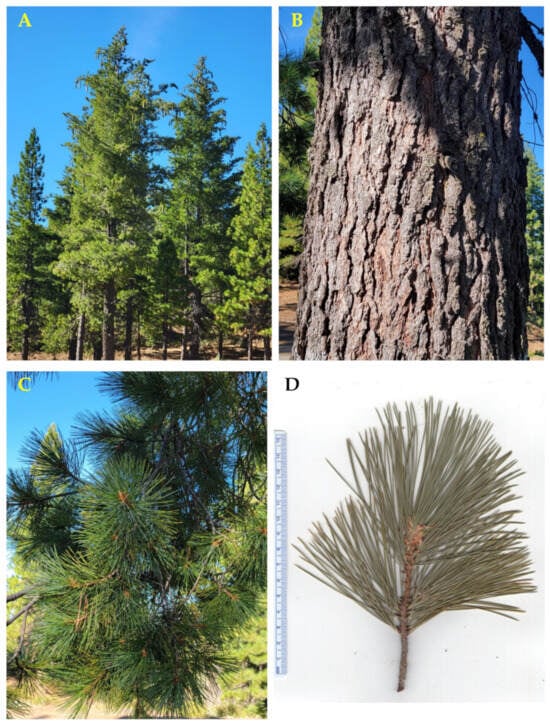

Figure 2.

Pinus albicaulis Engelm. (A): The tree habit. (B): Bark. (C): Leaves. (D): A scan of a twig with leaves. Photographs by K. Swor at the time of collection.

Pinus flexilis E. James (limber pine) is a five-needle pine species [9]. The tree is found in the Rocky Mountains of western North America, from southeastern British Columbia to southwestern Alberta, and south through Colorado and New Mexico. Limber pine is also found in the mountains of Utah, Idaho, Nevada, and California [12] (Figure 3). The tree grows up to 26 m tall, with gray bark and five needles per fascicle (Figure 4). The Navajo people used P. flexilis as a febrifuge, emetic, and cough medicine [13]. There has been one previous report on the leaf essential oil of P. flexilis from Idaho [14].

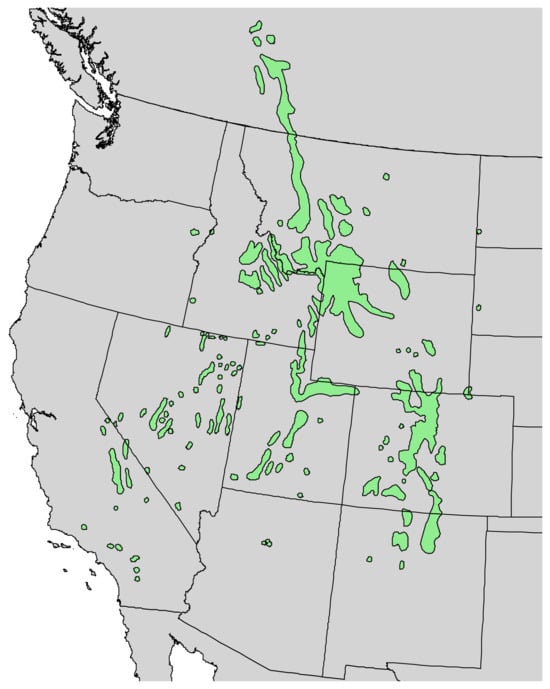

Figure 3.

Natural range of Pinus flexilis E. James [11].

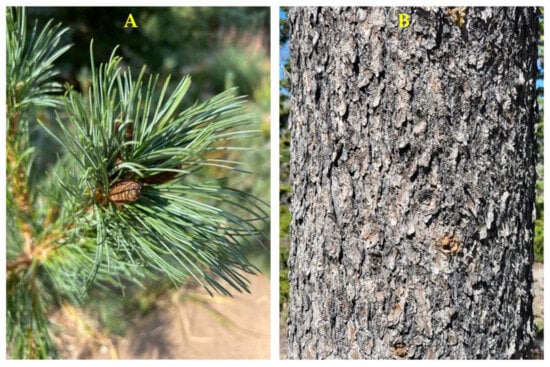

Figure 4.

Pinus flexilis E. James. (A): A branch with leaves (needles). (B): Bark. Photographs by K. Swor at the time of collection.

Pinus lambertiana Douglas (sugar pine) is found in montane dry to moist forests in western North America from Oregon, south through California, and into Baja California (Figure 5) [15]. These are very large trees, growing up to 75 m tall; the bark is cinnamon- to gray-brown in color and deeply furrowed. There are five leaves (needles) per fascicle; the seed cones are large (25–50 cm), yellow-brown, and resinous (Figure 6) [16]. The Mendocino Native Americans used P. lambertiana as a cathartic [17]. As far as we are aware, there have been no previous reports on the essential oil of P. lambertiana.

Figure 5.

Natural range of Pinus lambertiana Douglas [11].

Figure 6.

Pinus lambertiana Douglas. (A): The tree habit. (B): Bark. (C): Leaves (needles). (D): A scan of a twig with leaves. Photographs by A. Moore at the time of collection.

Pinus monticola Douglas ex D. Don (western white pine) is a large tree that is found in western North America from British Columbia; south through Washington, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, and Oregon; and into California (Figure 7) [18]. The tree is 30–50 m, up to 70 m tall; the bark is grey and smooth, becoming furrowed into hexagonal scaly plates in large individuals. There are five needles per fascicle; the seed cones are 10–25 cm long, creamy brown to yellowish (Figure 8) [18]. The Mahuna Native Americans of California took the plant internally to treat rheumatism [19]. There has been one previous report on the leaf essential oil of cultivated P. monticola from Argentina [20].

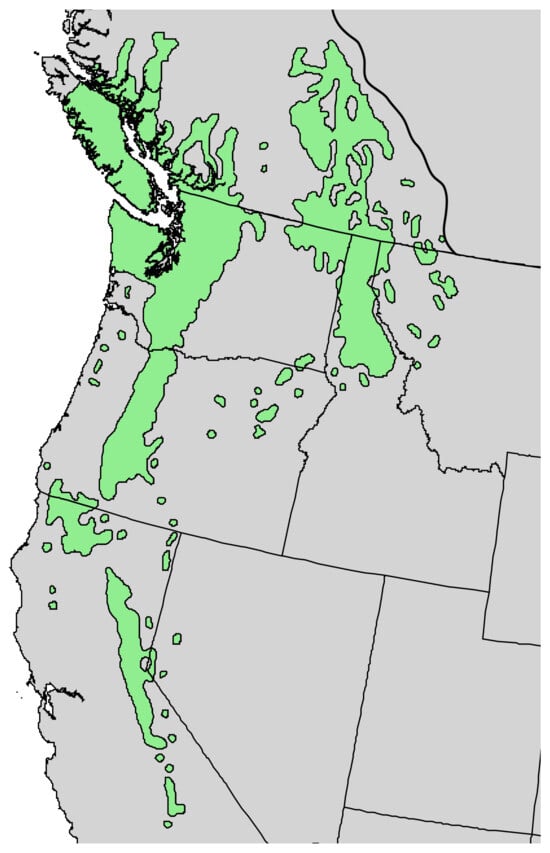

Figure 7.

Natural range of Pinus monticola Douglas ex. D. Don. [11].

Figure 8.

Pinus monticola Douglas ex. D. Don. (A): The tree habit. (B): The bark of a young tree. (C): Leaves (needles). (D): A scan of leaves. Photographs by K. Swor at the time of collection.

Pinus sabiniana Douglas (gray pine, foothill pine) is endemic to the dry foothills of the coast range and the Sierra Nevada Range in California, essentially encircling the Central Valley (Figure 9) [21]. The trees grow to 25 m tall, the bark is brown to near black and deeply furrowed, there are generally three needles per fascicle (15–32 cm long), and the seed cones are large (15–25 cm) (Figure 10) [22]. The Yuki people of California used the burning twigs and leaves of P. sabiniana as a sweat bath for rheumatism and bruises [17]. There has been one previous report on the leaf and wood essential oils of P. sabiniana [23].

Figure 9.

Natural range of Pinus sabiniana Douglas in California [11].

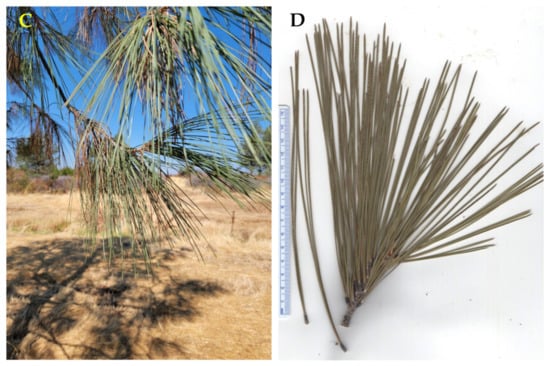

Figure 10.

Pinus sabiniana Douglas. (A): The habit of the tree. (B): Bark. (C): Leaves (needles). (D): A pressed sample of leaves. Photographs by A. Moore at the time of collection.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Pinus albicaulis Engelm

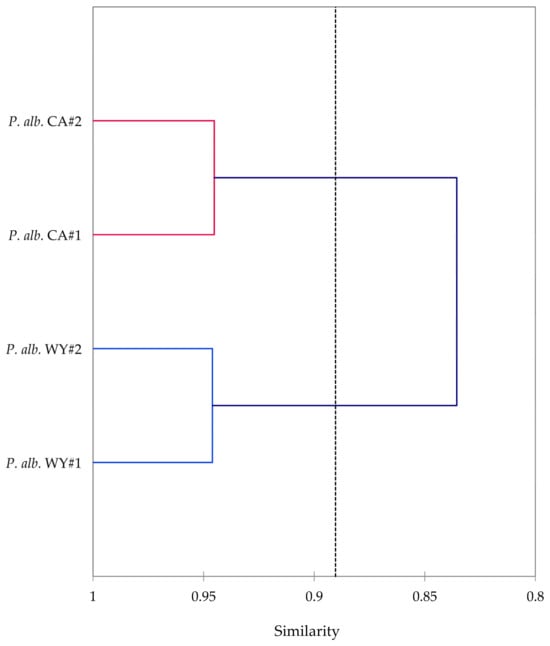

Leaf essential oils of P. albicaulis were obtained from sites in Wyoming and California in yields ranging from 2.96% to 3.51%. The essential oil compositions of P. albicaulis are presented in Table 1. A total of 106 components were identified in the P. albicaulis essential oils, accounting for more than 99% of the compositions. The major components were δ-3-carene (22.0–37.3%), α-pinene (7.8–12.6%), limonene (6.8–9.7%), β-phellandrene (2.0–11.3%), myrcene (3.0–7.1%), α-terpinyl acetate (0.2–14.4%), and terpinolene (3.3–5.1%). The essential oils from the Wyoming trees and the California trees are qualitatively similar and show only minor quantitative differences. That is, agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) shows 84% similarity between the two collection sites (Figure 11). Furthermore, two-sample t-test comparisons between the major components are not significantly different (Table 2).

Table 1.

Leaf essential oil compositions (percentages) of Pinus albicaulis Engelm. from Wyoming and from California.

Figure 11.

A dendrogram based on an agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis of the major components (δ-3-carene, α-pinene, β-pinene, limonene, myrcene, β-phellandrene, α-terpinyl acetate, α-cadinol, terpinolene, camphene, α-terpineol, and germacrene D) in the leaf essential oils of Pinus albicaulis.

Table 2.

Comparison (t-test) of concentrations of major components of Pinus albicaulis leaf essential oils collected from Wyoming and California.

2.2. Pinus flexilis E. James

Leaf essential oils were obtained from three individual trees growing in southern Utah in yields of 4.51%, 3.99%, and 5.02%. A total of 86 components were identified in the leaf essential oils of P. flexilis, which accounted for 99.6%, 99.9%, and 99.9% of the compositions. The leaf essential oil compositions of P. flexilis are listed in Table 3. The essential oils were dominated by β-pinene (11.1–54.8%) and α-pinene (19.8–37.5%), with lesser percentages of limonene (2.7–7.4%), β-phellandrene (1.8–5.1%), α-terpineol (1.5–4.9%), and α-cadinol (1.9–8.3%). The chemical compositions of the samples from southern Utah are qualitatively similar to a P. flexilis sample from southwestern Idaho, which showed α-pinene (37.1%) and β-pinene (21.9%) as the major components [14].

Table 3.

Leaf essential oil compositions (percentages) of Pinus flexilis E. James collected in southern Utah.

2.3. Pinus lambertiana Douglas

Leaves of P. lambertiana were collected near Butte Meadows, California, and hydrodistilled to give colorless essential oils in yields ranging from 2.01% to 2.26%. The gas chromatographic analysis revealed compositions of 126 total identified components (Table 4). The major components in the essential oils were β-pinene (28.9–46.4%), α-pinene (11.4–20.3%), (E)-β caryophyllene (2.5–16.6%), germacrene D (4.4–13.0%), and α-terpineol (2.6–6.9%).

Table 4.

Leaf essential oil compositions (percentages) of Pinus lambertiana from northern California.

2.4. Pinus monticola Douglas ex D. Don

Needles of P. monticola were collected from three individual trees located on a lahar slope of Mt. St. Helens, Washington, and three individual trees located near Priest Lake, Idaho. Hydrodistillation gave colorless essential oils ranging from 1.71% to 2.03%. The gas chromatographic analysis led to the identification of a total of 114 components (Table 5). The major leaf oil components were β-pinene (16.7–25.6%), α-pinene (9.8–15.7%), δ-3-carene (8.2–12.9%), limonene (3.7–8.2%), β-phellandrene (3.4–6.2%), myrcene (3.9–4.9%), α-terpineol (2.1–7.8%), α-cadinol (0.7–6.9%), and trans-β-elemene (0.7–15.2%). A previous examination of P. monticola, cultivated in Valle Chico, Argentina, was found to show β-pinene (22.8%), α-pinene (21.0%), limonene (14.0%), isobornyl formate (5.7%), terpinolene (5.1%), myrcene (4.2%), and δ-3-carene (4.2%) as major components [20].

Table 5.

Leaf essential oil compositions (percentages) of Pinus monticola from Mt. St. Helens, Washington, and Priest Lake, Idaho.

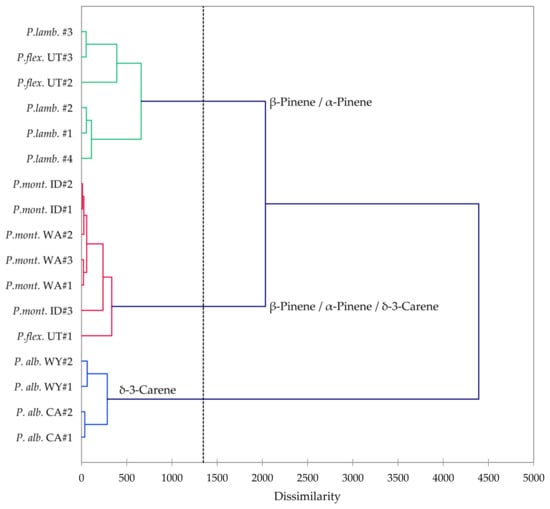

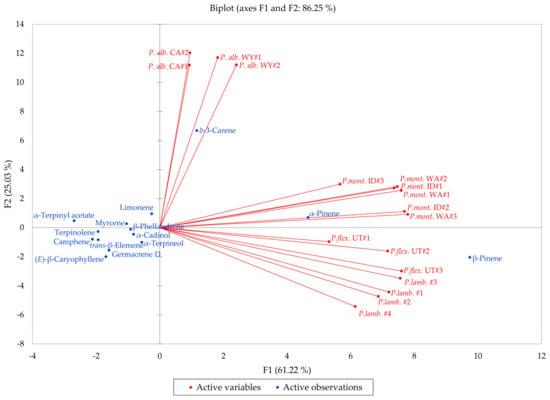

Pinus albicaulis, P. flexilis, P. lambertiana, and P, monticola are all members of the subgenus Strobus, section Quinquefoliae, subsection Strobus (the five-needle white pine group). In order to investigate the similarities and differences in volatile phytochemicals in these species, a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and a principal component analysis (PCA) were carried out. The HCA shows three well-defined clusters based on the essential oil compositions (Figure 12): (a) a cluster dominated by β-pinene and α-pinene and made up of samples of P. flexilis and P. lambertiana; (b) a cluster dominated by δ-3-carene and made up of P. albicaulis samples from northern Wyoming and from northern California; and (c) a cluster defined by relatively large percentages of β-pinene, α-pinene, and δ-3-carene, composed largely by samples of P. monticola from Idaho and from Washington. The PCA further delineates the species based on essential oil compositions (Figure 13). The P. albicaulis samples all strongly correlate with δ-3-carene; P. lambertiana and P. flexilis essential oil samples correlate strongly with β-pinene; and P. monticola samples positively correlate with β-pinene, α-pinene, and δ-3-carene. Unless cones are present, it is generally difficult to distinguish P. flexilis from P. albicaulis [6]. However, the leaf volatile compositions readily distinguish the P. albicaulis from the other members of the Strobus group. Pinus albicaulis essential oils are dominated by δ-3-carene, while the other Pinus essential oils are rich in α- and β-pinenes. Thus, based on essential oil compositions, it may be possible to more confidently identify members of the Strobus subgenus.

Figure 12.

Dendrogram based on hierarchical cluster analysis of leaf essential oil compositions of Pinus albicaulis, Pinus flexilis, Pinus lambertiana, and Pinus monticola.

Figure 13.

Biplot based on principal component analysis of Pinus albicaulis, Pinus flexilis, Pinus lambertiana, and Pinus monticola leaf essential oil compositions.

2.5. Pinus sabiniana Douglas

Leaves of P. sabiniana were collected from three individual trees growing near Paradise, California. Hydrodistillation gave colorless essential oils in yields of 2.33 to 2.45%. The gas chromatographic analysis of the leaf essential oils resulted in the identification of 96 components, accounting for 99.6%, 99.6%, and 99.8% of the total compositions (Table 6). The leaf essential oils showed notable variation in compositions, depending on the elevation of the collection site, whether in Butte Creek Canyon (samples #1 and #2) or on the top of the butte in Paradise (sample #3). Thus, for example, the major component in samples #1 and #2 was α-pinene (65.0% and 61.2%) but only 15.8% in sample #3, while the major component in sample #3 was limonene (54.9%) but only 1.5% and 1.4% in samples #1 and #2. Other major components in the leaf essential oils were (Z)-β-ocimene (7.9%, 11.3%, and 9.6%), β-pinene (6.6%, 6.6%, and 2.0%), and myrcene (3.8%, 4.9%, and 5.7%). The leaf essential oil compositions in this study are in qualitative agreement with a previous study on P. sabiniana from Placerville, California, that showed α-pinene (39.1%), limonene (10.5%), β-phellandrene (10.4%), thunbergol (4.7%), (Z)-β-ocimene (4.6%), methyl chavicol (4.5%), myrcene (3.6%), and β-pinene (3.3%) to be the major components [23]. Note that in addition to elevation, a recent wildfire episode (the so-called Camp Fire, 8 November 2018 [29]) may also have affected the trees in this study.

Table 6.

Leaf essential oil compositions (percentages) of Pinus sabiniana collected in Paradise, California.

2.6. Enantiomeric Distributions

The leaf essential oils of P. albicaulis, P. flexilis, P. lambertiana, P. monticola, and P. sabiniana were analyzed by enantioselective gas chromatography in order to determine the enantiomeric distributions of chiral monoterpenoid components. The enantiomeric distributions of chiral monoterpenoid components found in the Pinus species are compiled in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11, respectively.

Table 7.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral monoterpenoids in Pinus albicaulis.

Table 8.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral monoterpenoids in Pinus flexilis.

Table 9.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral monoterpenoids in Pinus lambertiana.

Table 10.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral monoterpenoids in Pinus monticola.

Table 11.

Enantiomeric distribution of chiral monoterpenoids in Pinus sabiniana.

Only one enantiomer of α-thujene was observed in P. albicaulis or P. flexilis. Unfortunately, the RI values for (+)- and (−)-α-thujene are very similar, so the assignment of (−)-α-thujene is tentative. Interestingly, the enantiomeric distribution for α-pinene showed (+)-α-pinene to be dominant in P. flexilis from southern Utah, whereas (−)-α-pinene dominated P. albicaulis. It would be tempting to suggest that the enantiomeric distribution of α-pinene could serve to differentiate P. albicaulis from P. flexilis, but (−)-α-pinene dominated P. flexilis from southern Idaho [14]. Indeed, the enantiomeric distribution of α-pinene in Pinus species is variable both between species and within species [14,30]. Nevertheless, (−)-α-pinene was dominant in P. lambertiana, P. monticola, and P. sabiniana.

(−)-Limonene often dominates the essential oils of Pinus species [14], but there are exceptions (e.g., Pinus mugo Turra [31], Pinus sylvestris L. [31], and Pinus uncinata subsp. uliginosa (G.E.Neumann ex Wimm.) Businský [32]). In this work, (−)-limonene was dominant in P. albicaulis, P. flexilis, and P. lambertiana, but the limonene distribution was variable in P. monticola and P. sabiniana.

Similarly, (−)-β-phellandrene was dominant in P. albicaulis, P. flexilis, P. lambertiana, and P. sabiniana, consistent with observations in Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex C. Lawson var. ponderosa, Pinus contorta Douglas ex Loudon subsp. contorta, P. flexilis from Idaho [14], and Pinus contorta subsp. murrayana (Balf.) Engelm. [33]. In contrast, however, β-phellandrene was virtually racemic in P. monticola. The (−)-enantiomers dominated camphene, β-pinene, terpinen-4-ol, and α-terpineol in P. albicaulis, P. flexilis, P. lambertiana, P. monticola, and P. sabiniana. (−)-Sabinene was dominant in the leaf essential oils of P. albicaulis and P. flexilis. Only one enantiomer was observed for δ-3-carene in P. albicaulis, P. flexilis, and P. monticola. The observed RI value is consistent with (+)-δ-3-carene, but a reference for (−)-δ-3-carene was not available for comparison. The only enantiomer of borneol was (−)-borneol in the essential oils of P. monticola, which is consistent with those observed in the essential oils of P. contorta latifolia [33], P. flexilis from Idaho [14], Pinus edulis Engelm., and Pinus monophylla Torr. & Frém. [30].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Collection and Identification

The collection details are summarized in Table 12. Leaves (needles) were collected from individual trees at the locations indicated. Several branch tips from each individual tree were collected. Voucher specimens were deposited with the University of Alabama in Huntsville herbarium. Identification in the field was carried out by W.N. Setzer and later verified by comparison with herbarium samples from the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium, New York Botanical Garden (https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/vh/, accessed on 12 December 2024). The leaves were stored frozen (−20 °C) until hydrodistillation.

Table 12.

Collection and hydrodistillation details for Pinus species (P. albicaulis, P. flexilis, P. lambertiana, P. monticola, and P. sabiniana).

3.2. Essential Oils

The leaf essential oils of the Pinus species were obtained by hydrodistillation of each tree sample using a Likens–Nickerson apparatus for four hours with continuous extraction of the distillate with dichloromethane to give colorless essential oils. The hydrodistillation yields are summarized in Table 12.

3.3. Gas Chromatographic Analyses

The Pinus leaf essential oils were subjected to gas chromatographic analyses (GC-FID, GC-MS, and enantioselective GC-MS) as previously described [14,33]. One replicate was carried out for each essential oil.

3.4. Statistical Analyses

The agglomerative hierarchical cluster analyses (HCA) and principal component analyses (PCA) were carried out using XLSTAT v. 2018.1.1.62926 (Addinsoft, Paris, France). In the case of HCA on P. albicaulis, the percentages of the major components (δ-3-carene, α-pinene, β-pinene, limonene, myrcene, β-phellandrene, α-terpinyl acetate, α-cadinol, terpinolene, camphene, α-terpineol, and germacrene D) were used, Pearson correlation was used to measure similarity, and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA) was used for cluster definition. For the HCA on the Strobus group, the concentrations of the most abundant components (β-pinene, α-pinene, δ-3-carene, limonene, α-terpineol, β-phellandrene, myrcene, α-cadinol, germacrene D, (E)-β-caryophyllene, terpinolene, camphene, α-terpinyl acetate, and trans-β-elemene) were used. Dissimilarity was used to determine clusters considering Euclidean distance, and Ward’s method was used to define agglomeration. A PCA, type Pearson correlation, was carried out to verify the results of the HCA using the same major components. Student’s t-test [34] was used to compare the major components in the P. albicaulis samples using Minitab® 18 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). Differences of p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

4. Conclusions

This report, for the first time, presents the leaf essential oil compositions, including enantiomeric distributions, for P. albicaulis and P. lambertiana. In addition, the enantiomeric distributions have been determined for P. monticola and P. sabiniana. The pine essential oils examined in this study reveal high concentrations of α-pinene and β-pinene, typical for pine species. There are, however, interspecific variations in compounds such as δ-3-carene, (E)-β-caryophyllene, and germacrene D. The enantiomeric distributions are, in general, inconsistent throughout the genus. However, the differences observed may be useful in identifying species, hybrids, or essential oil adulteration. An obvious limitation of this study is that samples were obtained opportunistically, with only a few samples of each species obtained from limited geographical locations. While this work does provide additional insight into the essential oil compositions of several understudied Pinus species in western North America, additional research is needed to confirm these observations. For example, are the leaf essential oil compositions of P. albicaulis and P. flexilis relatively consistent throughout their range? Additional collections and analyses of the Pinus species from other locations in their respective ranges would provide additional information regarding the volatile phytochemistry of these pine trees. Depending on availability (e.g., Pinus albicaulis is a threatened species), the essential oils may be useful in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, or aromatherapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.N.S.; methodology, P.S. and W.N.S.; software, P.S.; validation, P.S. and W.N.S.; formal analysis, A.P., P.S. and W.N.S.; investigation, A.M., E.A., K.S., A.P., P.S. and W.N.S.; resources, P.S. and W.N.S.; data curation, W.N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.N.S.; writing—review and editing, A.M., E.A., K.S., A.P. and P.S.; visualization, W.N.S.; supervision, P.S. and W.N.S.; project administration, W.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available within this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to James Moore and Dewey Ankney for help with the collection of plant material. This work was carried out as part of the activities of the Aromatic Plant Research Center (APRC, https://aromaticplant.org/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Flora Online, W.F.O. Pinus L. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000029794 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Rhind, J.P. Essential Oils: A Comprehensive Handbook for Aromatic Therapy; Singing Dragon: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1787752290. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneton, J. Pharmacognosy, 2nd ed.; Intercept Ltd.: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 1-898298-63-7. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, B.-E.; Wink, M. Medicinal Plants of the World, 2nd ed.; CABI: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-786393-25-8. [Google Scholar]

- World Flora Online, W.F.O. Pinus albicaulis Engelm. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000482599 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Earle, C.J. Pinus albicaulis. The Gymnosperm Database. Available online: https://www.conifers.org/pi/Pinus_albicaulis.php (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Warwell, M.V.; Shaw, R.G. Climate-related genetic variation in a threatened tree species, Pinus albicaulis. Am. J. Bot. 2017, 104, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomback, D.F.; Sprague, E. The National Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan: Restoration model for the high elevation five-needle white pines. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 521, 120204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeking, S.A.; Windmuller-Campione, M.A. Comparative species assessments of five-needle pines throughout the western United States. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; threatened species status with section 4(d) rule for whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). Fed. Regist. 2022, 87, 76882–76917. [Google Scholar]

- Little, E.L. Digital Representations of Tree Species Range Maps. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Flora_distribution_maps_of_North_America#Artemisia (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Steele, R. Pinus flexilis James, limber pine. In Silvics of North America, Volume 1. Conifers; Burns, R.M., Honkala, B.H., Eds.; Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Vestal, P.A. The ethnobotany of the Ramah Navaho. Pap. Peabody Museum Am. Archaeol. Ethnol. 1952, 40, 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ankney, E.; Swor, K.; Satyal, P.; Setzer, W.N. Essential oil compositions of Pinus species (P. contorta subsp. contorta, P. ponderosa var. ponderosa, and P. flexilis); enantiomeric distribution of terpenoids in Pinus species. Molecules 2022, 27, 5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- eFloras.org. Pinus lambertiana Douglas. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=233500939 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- World Flora Online, W.F.O. Pinus lambertiana Douglas. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000481091 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Chestnut, V.K. Plants Used by the Indians of Mendocino County, California. Contrib. U.S. Natl. Herb. 1902, 7, 295–408. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, C.J. Pinus monticola Douglas ex D. Don; The Gymnosperm Database. Available online: https://www.conifers.org/pi/Pinus_monticola.php (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Romero, J.B. The Botanical Lore of the California Indians; Vantage Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1954; ISBN 978-9355751638. [Google Scholar]

- Dambolena, J.S.; Gallucci, M.N.; Luna, A.; Gonzalez, S.B.; Guerra, P.E.; Zunino, M.P. Composition, antifungal and antifumonisin activity of Pinus wallichiana, Pinus monticola and Pinus strobus essential oils from Patagonia Argentina. J. Essent. Oil-Bearing Plants 2016, 19, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, C.J. Pinus sabiniana Douglas ex D.Don. The Gymnosperm Database. Available online: https://www.conifers.org/pi/Pinus_sabiniana.php (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- eFloras.org. Pinus sabiniana Douglas. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=233500953 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Adams, R.P.; Wright, J.W. Alkanes and terpenes in wood and leaves of Pinus jeffreyi and P. sabiniana. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2012, 24, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Dool, H.; Kratz, P.D. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1963, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-932633-21-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mondello, L. FFNSC 3; Shimadzu Scientific Instruments: Columbia, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NIST20; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- Satyal, P. Development of GC-MS Database of Essential Oil Components by the Analysis of Natural Essential Oils and Synthetic Compounds and Discovery of Biologically Active Novel Chemotypes in Essential Oils. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anguiano, D.; Gee, A. Fire in Paradise: An American Tragedy; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0393542165. [Google Scholar]

- Swor, K.; Poudel, A.; Satyal, P.; Setzer, W.N. The pinyon pines of Utah: Leaf essential oils of Pinus edulis and Pinus monophyla. J. Essent. Oil-Bearing Plants 2024, 27, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochocka, J.R.; Asztemborska, M.; Sybilska, D.; Langa, W. Determination of enantiomers of terpenic hydrocarbons in essential oils obtained from species of Pinus and Abies. Pharm. Biol. 2002, 40, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonikowski, R.; Celiński, K.; Wojnicka-Półtorak, A.; Maliński, T. Composition of essential oils isolated from the needles of Pinus uncinata and P. uliginosa grown in Poland. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swor, K.; Satyal, P.; Poudel, A.; Setzer, W.N. Gymnosperms of Idaho: Chemical compositions and enantiomeric distributions of essential oils of Abies lasiocarpa, Picea engelmannii, Pinus contorta, Pseudotsuga menziesii, and Thuja plicata. Molecules 2023, 28, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1974; ISBN 0-13-084542-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).