Control of Optical Reflection in Ca2MgWO6 by Co and Mo Doping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

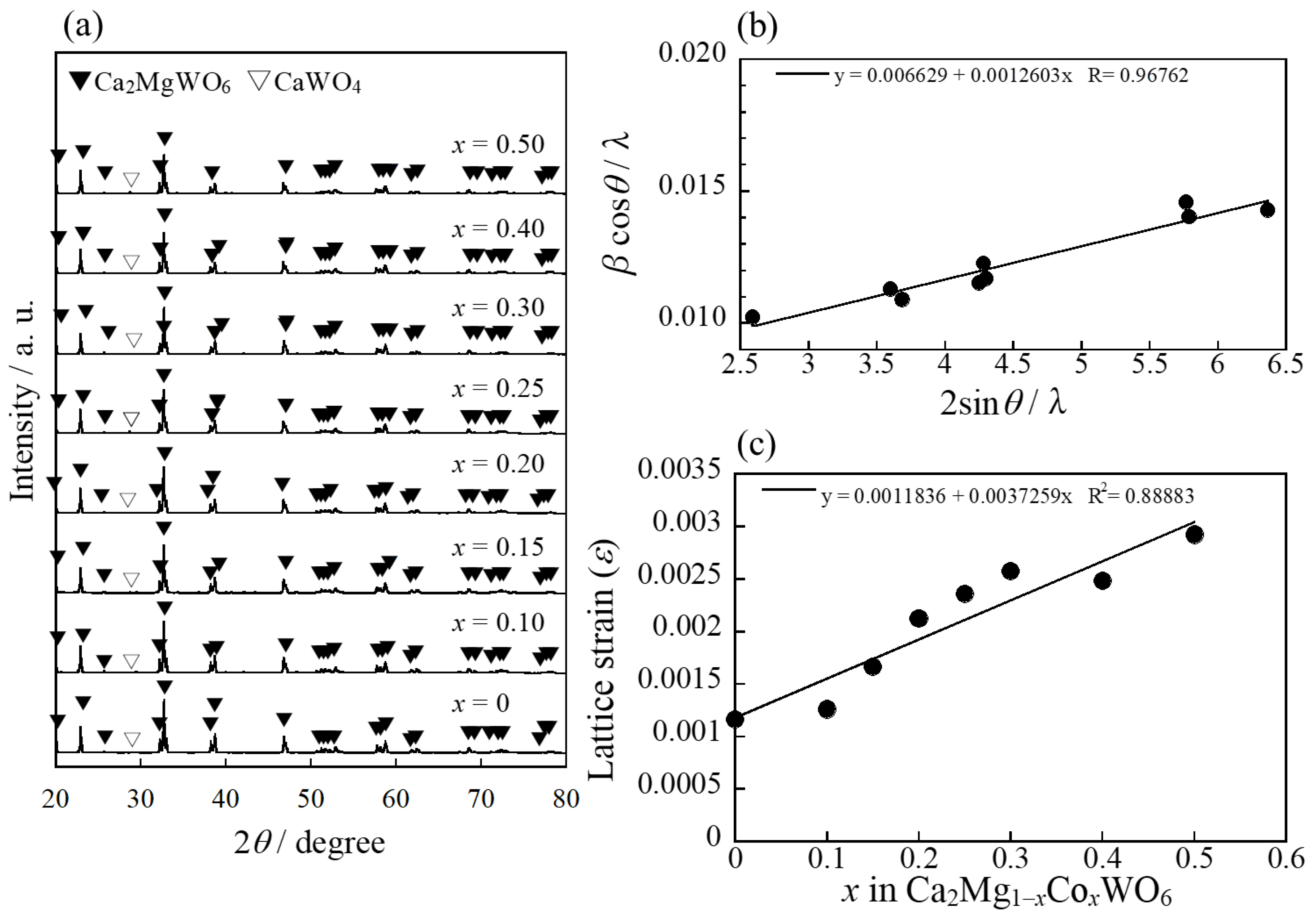

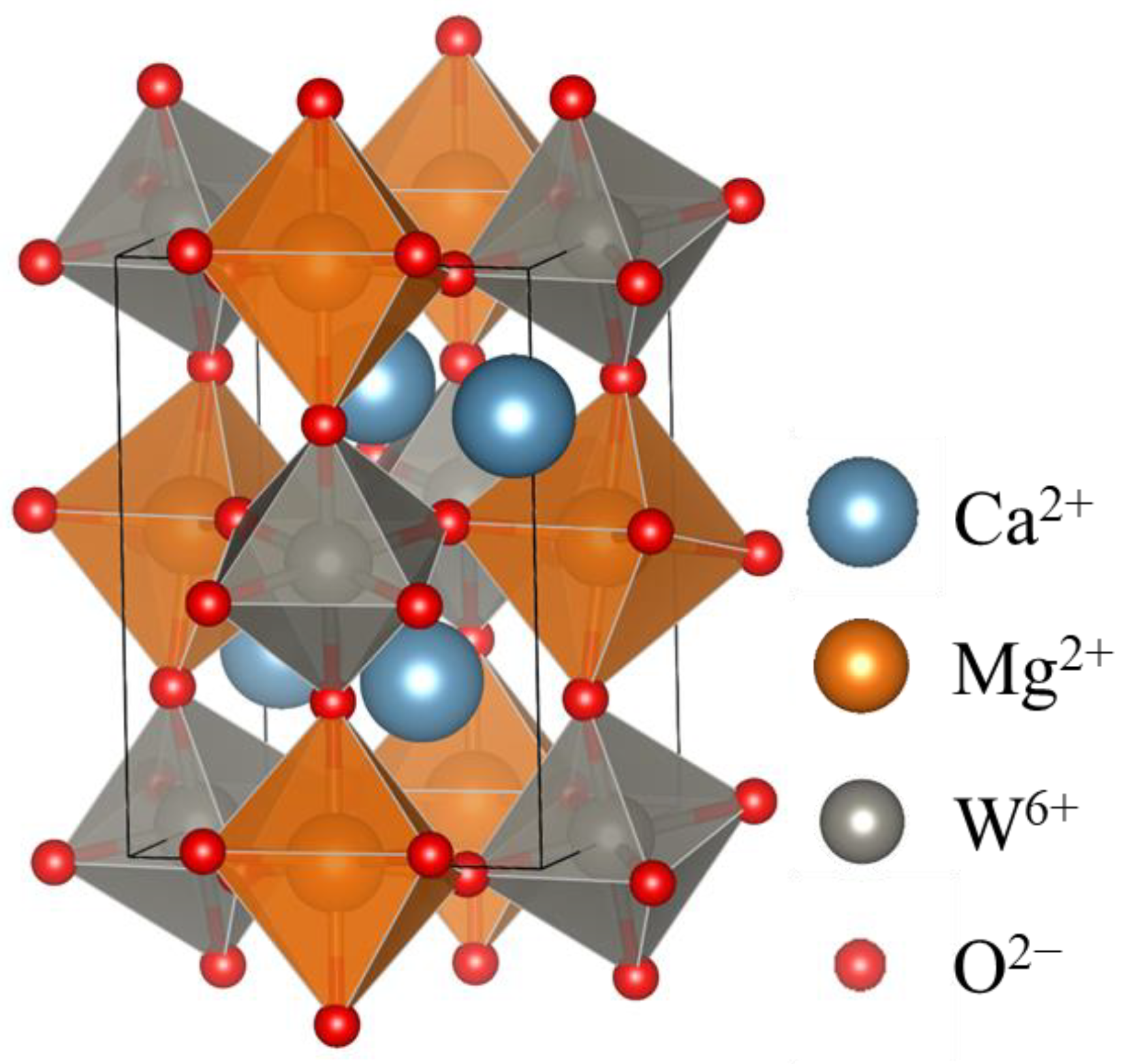

2.1. Ca2Mg1−xCoxWO6 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.50)

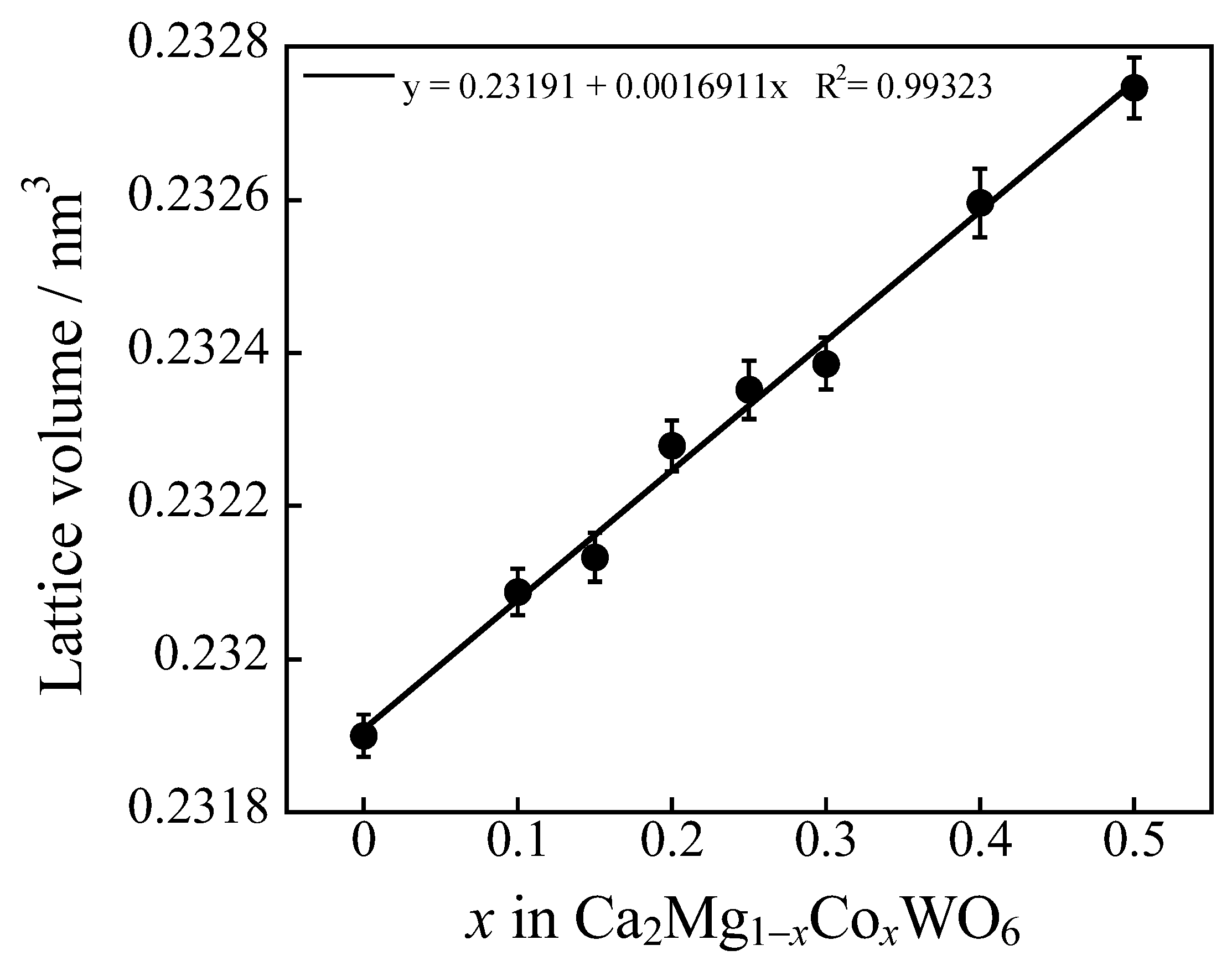

2.1.1. X-ray Powder Diffraction

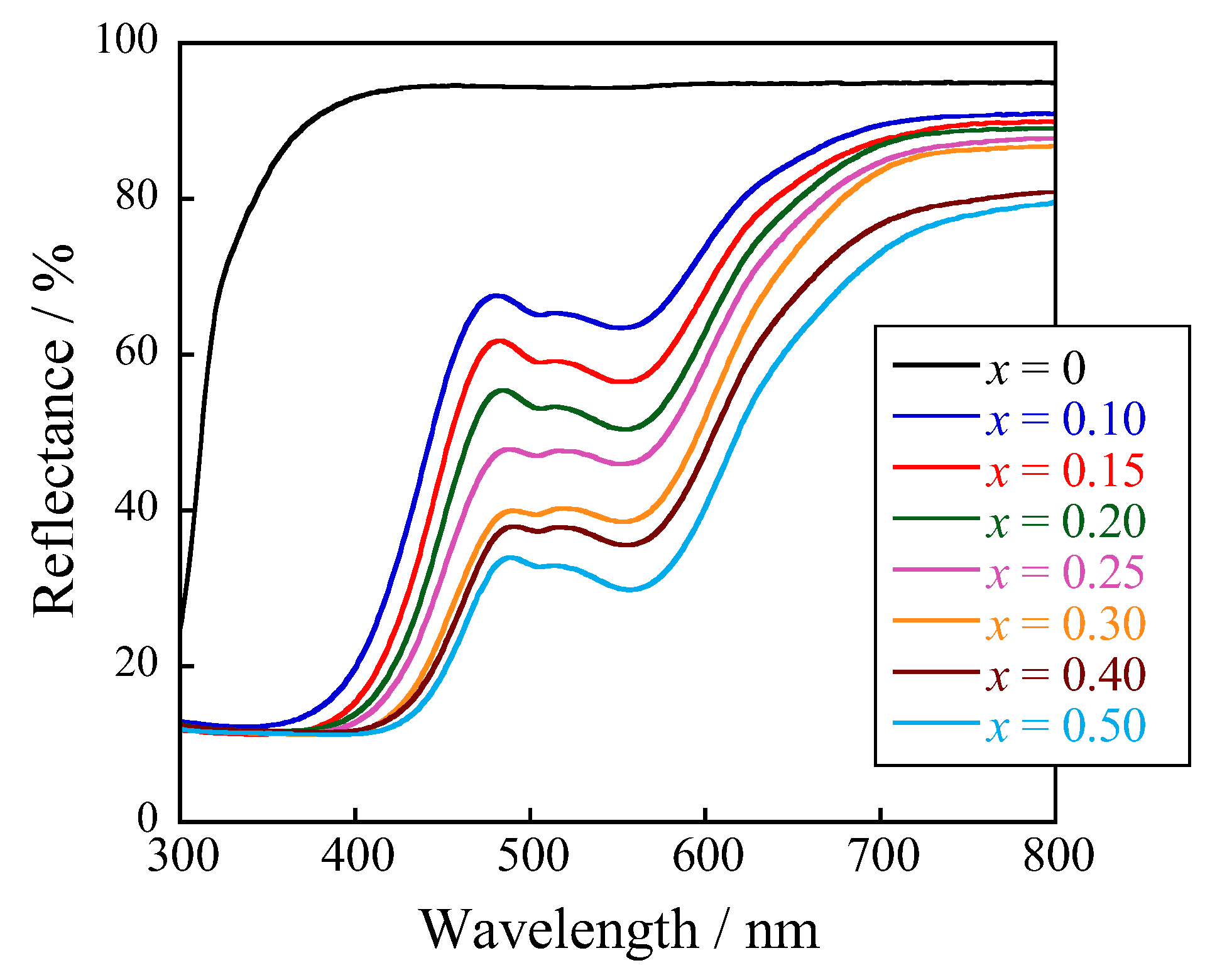

2.1.2. Ultraviolet–Visible Reflectance Spectra

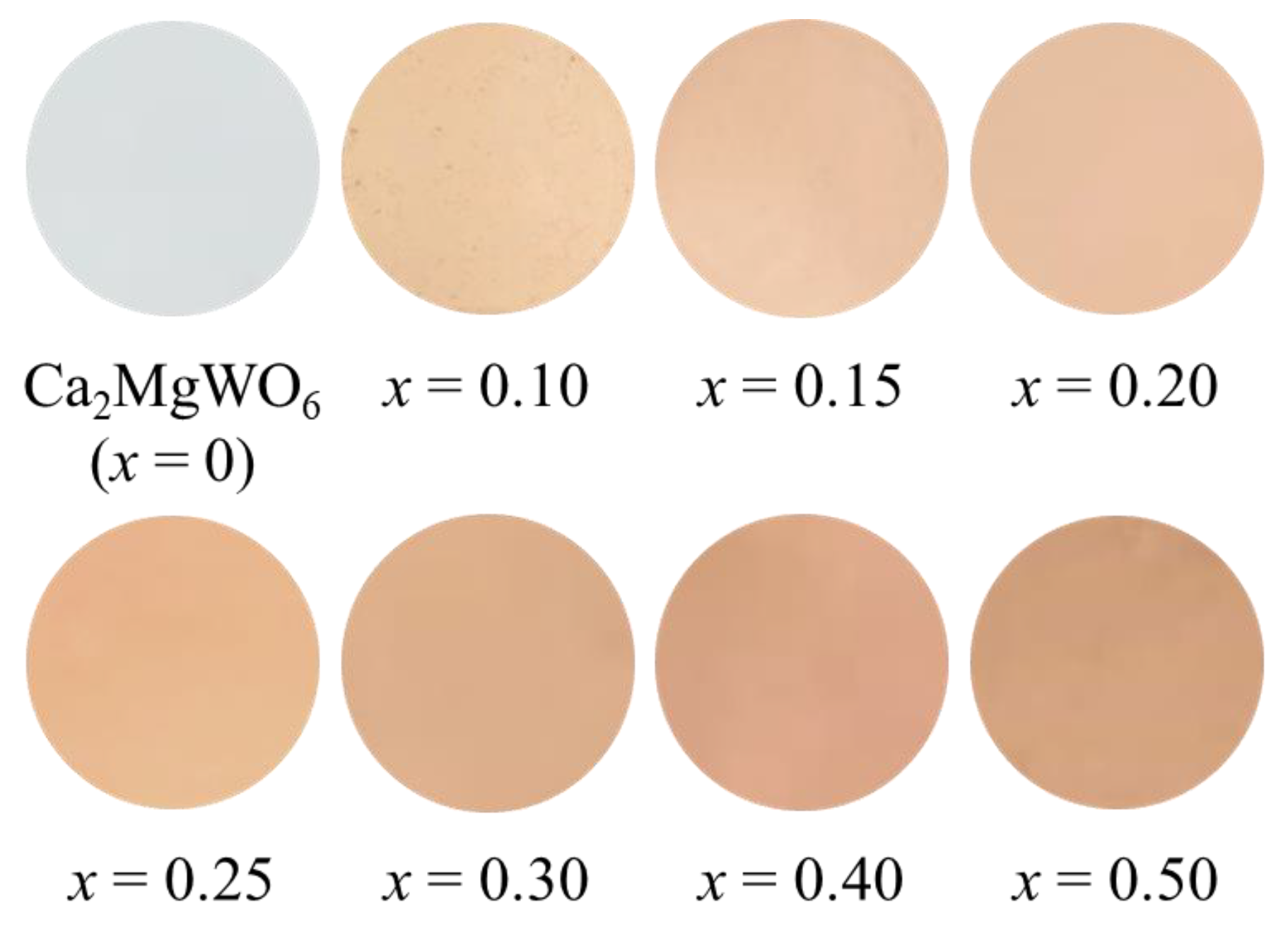

2.1.3. Color Property

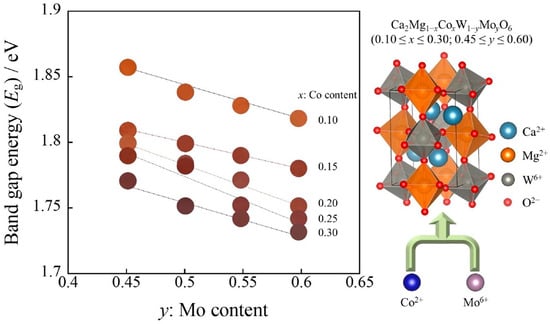

2.2. Ca2Mg1−xCoxW1−yMoyO6 (0.10 ≤ x ≤ 0.30; 0.45 ≤ y ≤ 0.60)

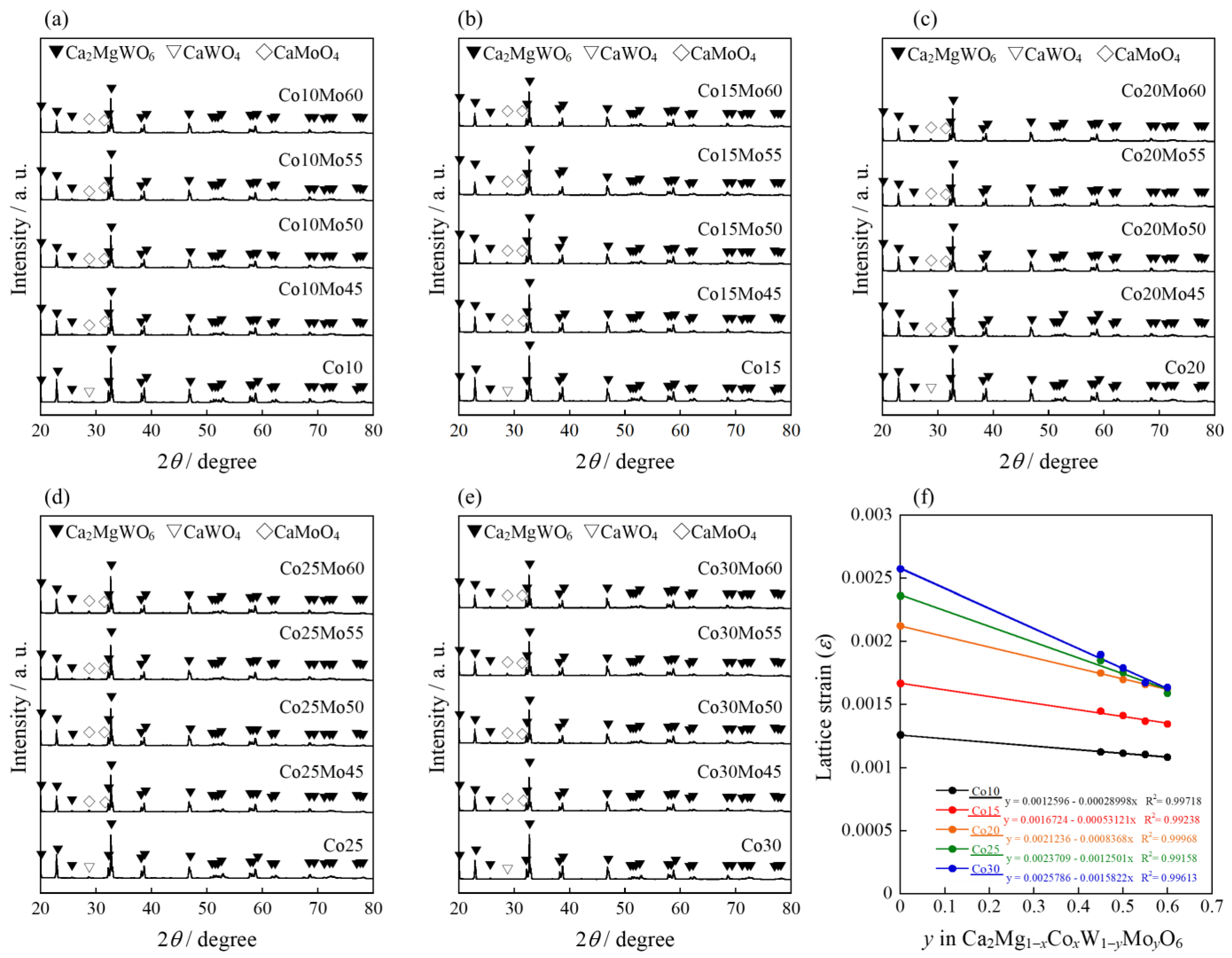

2.2.1. X-ray Powder Diffraction

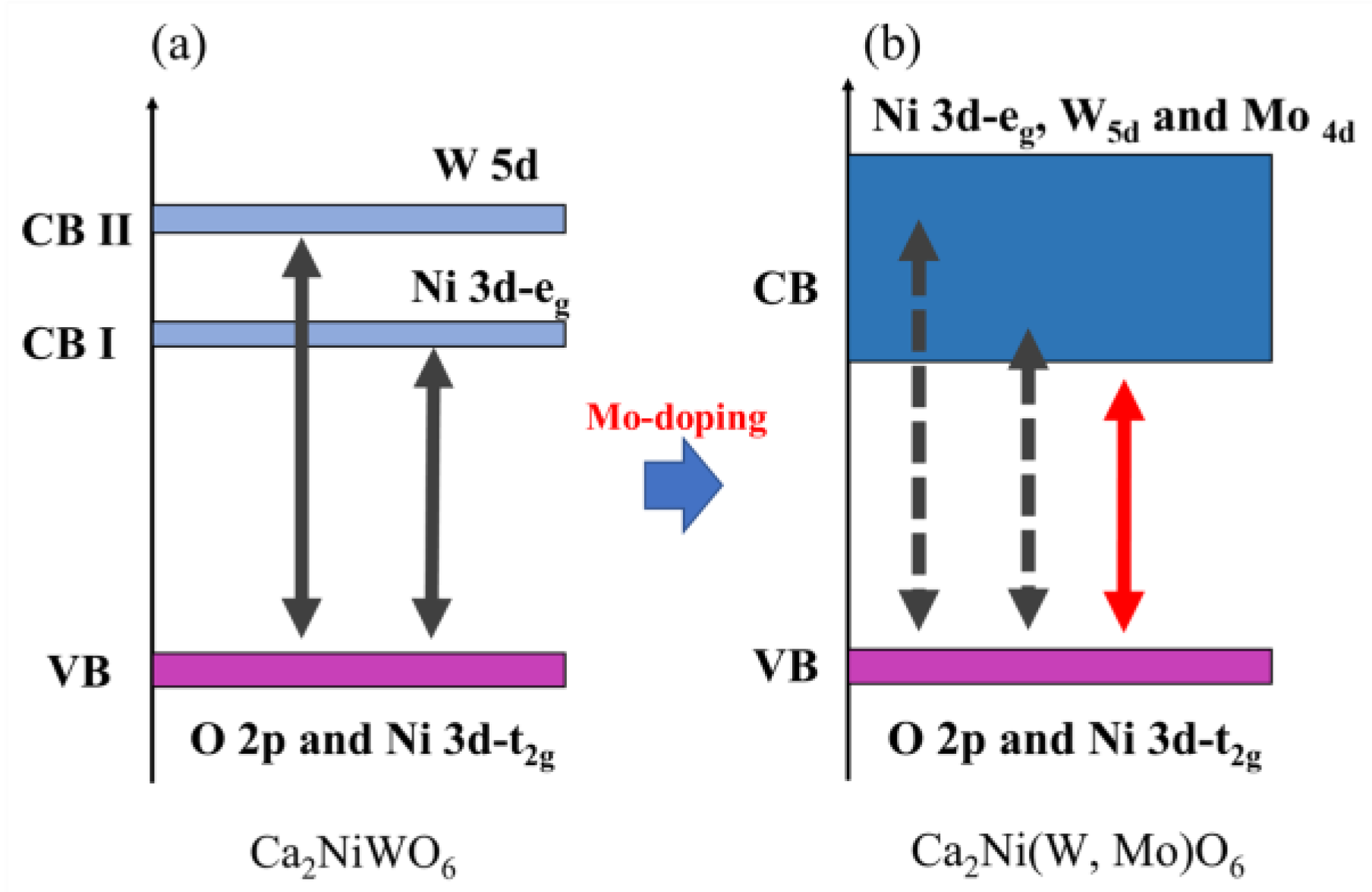

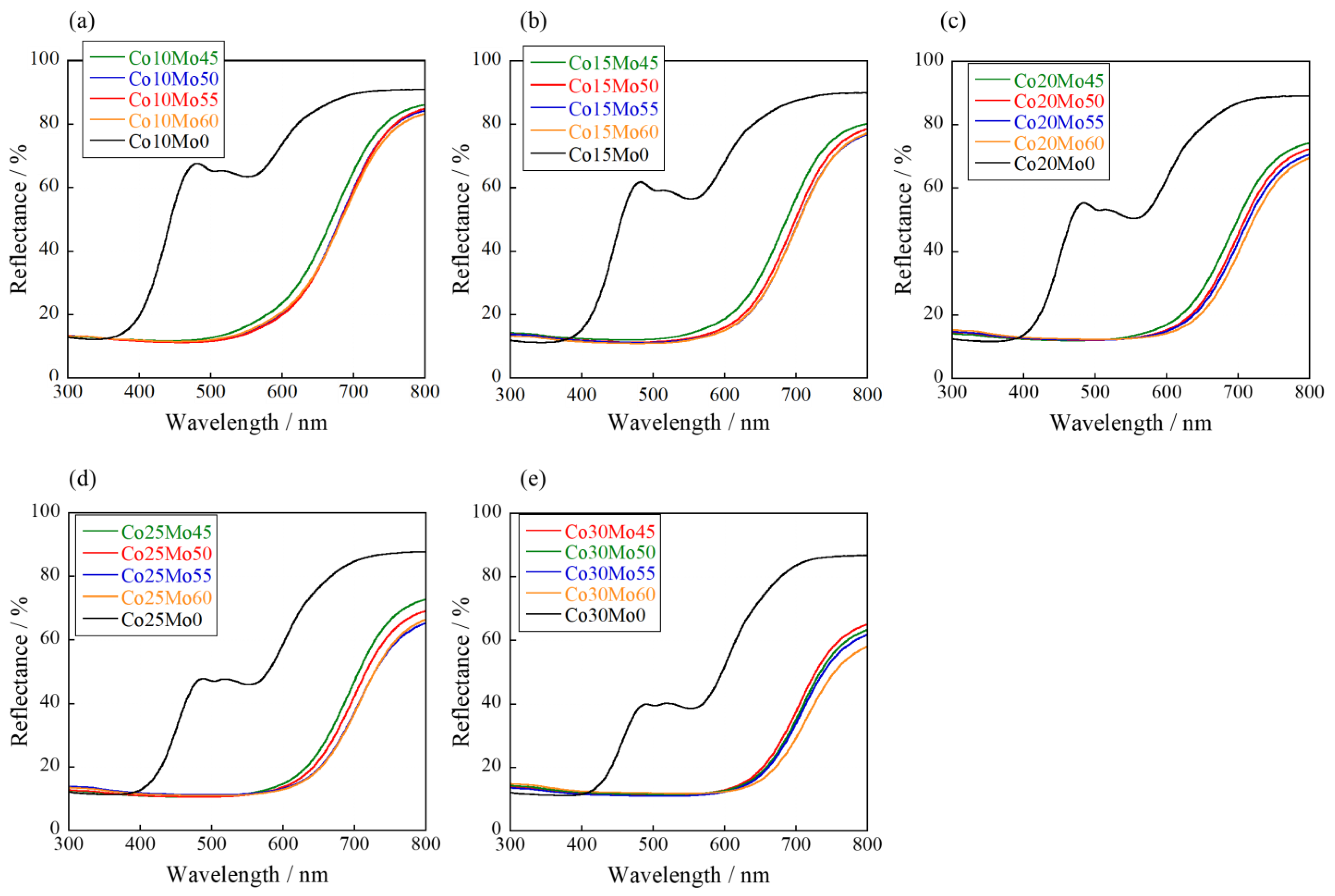

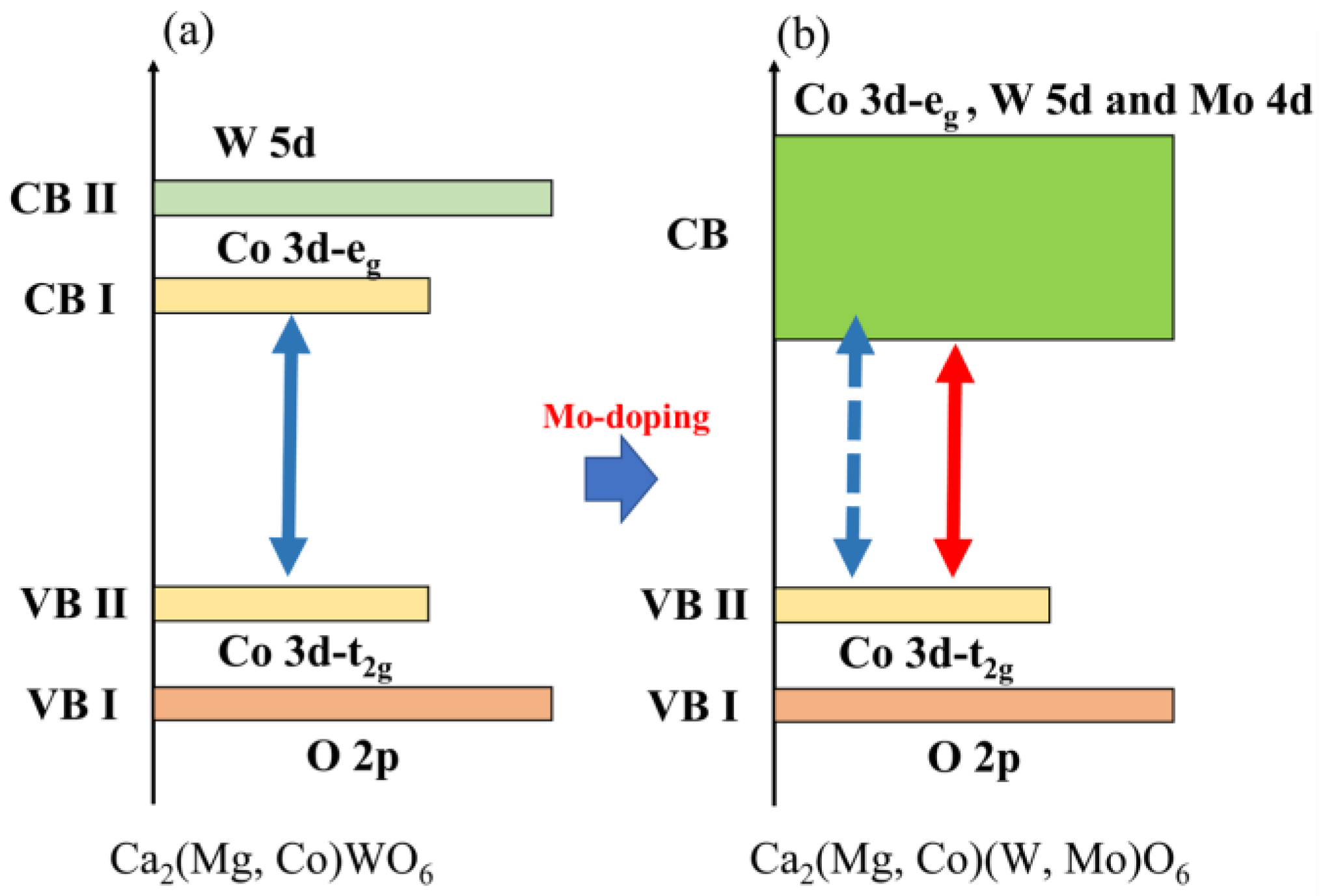

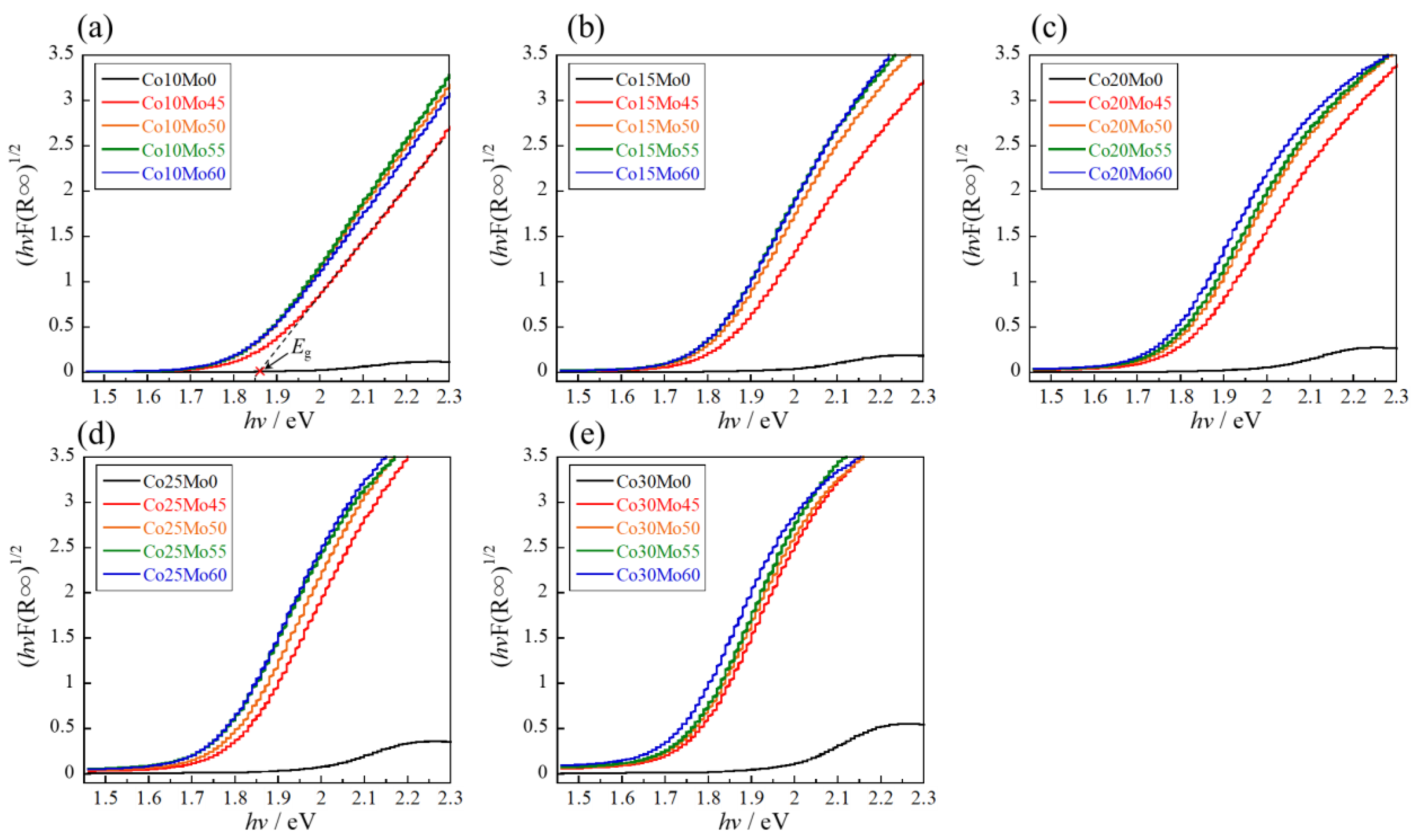

2.2.2. UV–Vis Reflectance Spectra

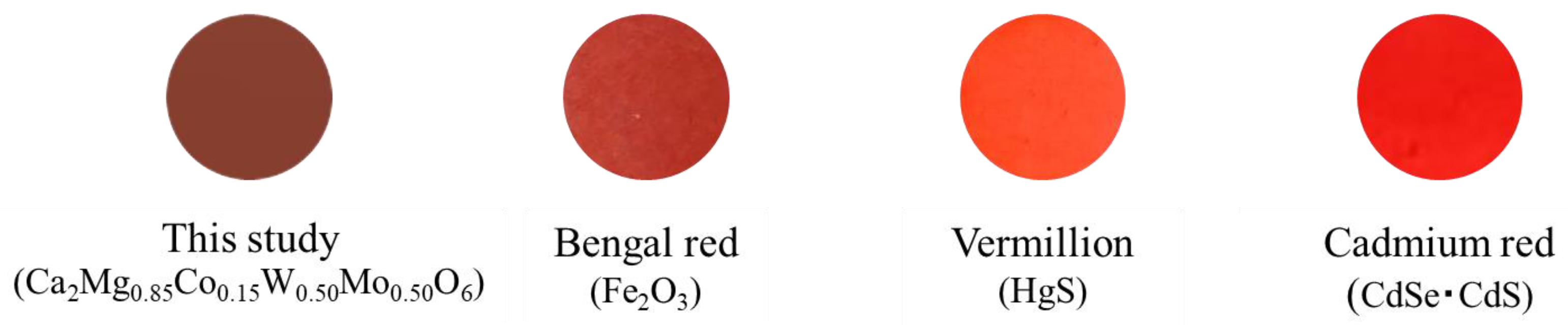

2.2.3. Color Property

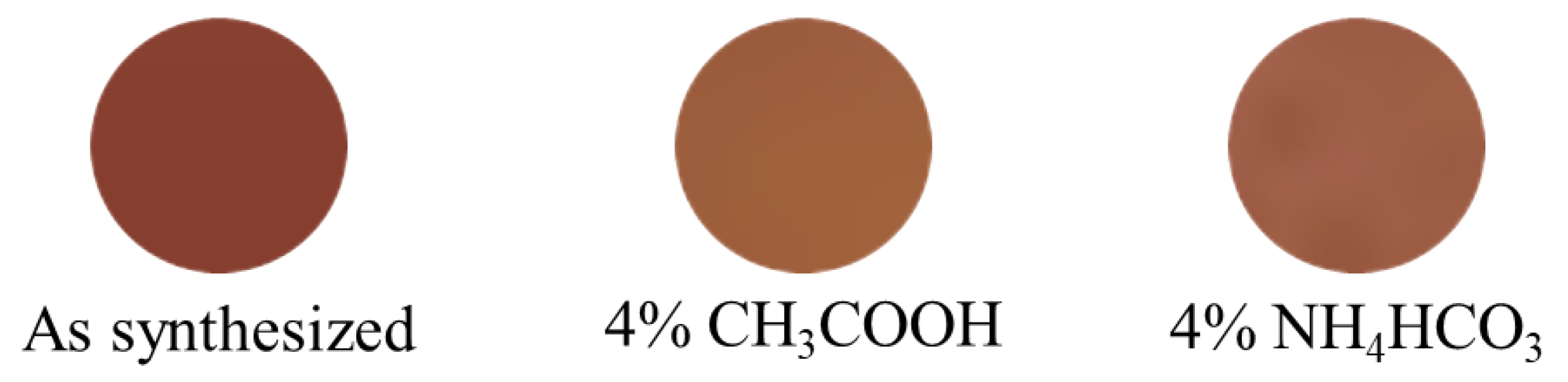

2.2.4. Chemical Stability Test

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Jin, C.; Shao, S.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chang, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, X. Electron-Deficient Cu Site Catalyzed Acetylene Hydrochlorination. Green. Energy Environ. 2023, 8, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ye, M.; Chen, S.; Han, A.; Zang, Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Mica/γ-Ce2−xYxS3 Composite Red Pigments with UV Absorption and High NIR Reflectance. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 16023–16030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Letschert, H.P. Inorganic Yellow-Red Pigments without Toxic Metals. Nature 2000, 404, 980–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-G.; Li, Y.-M.; Wang, Z.-M.; Shen, Z.-Y.; Xie, Z.-X. Enhanced High Temperature Oxidization Resistance of Silica Coated γ-Ce2S3 Red Pigments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 387, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, A.; Takeuchi, N.; Masui, T.; Imanaka, N. Novel Environment Friendly Inorganic Red Pigments Based on Bi4V2O11. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 44886–44894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Masui, T.; Imanaka, N. Novel Environmentally Friendly Inorganic Red Pigments Based on Calcium Bismuth Oxides. J. Adv. Ceram. 2015, 4, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, T.; Imanaka, N. Novel Environment-Friendly Inorganic Red Pigments Based on (Bi, Er, Y, Fe)2O3 Solid Solutions. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2014, 2, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirpour, M.; Sani, M.A.F.; Mirhabibi, A. Synthesis and Study of a New Class of Red Pigments Based on Perovskite YAlO3 Structure. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Hasegawa, T.; Watanabe, M.; Sugimoto, K.; Saito, Y.; Uematsu, K.; Toda, K.; Sato, M. Environmentally Friendly Rb3V5O14 Fluorescent Red Pigment. Dye. Pigm. 2017, 136, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Li, J.; Sleight, A.W.; Subramanian, M.A. New Oxides Showing an Intense Orange Color Based on Fe3+ in Trigonal-Bipyramidal Coordination. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5858–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, L.S.; Rao, P.P.; Reddy, M.L. Environment-Friendly Red Pigments from CeO2–Fe2O3–Pr6O11 Solid Solutions. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 461, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, L.S.; Rao, P.P.; Sameera, S.; Koshy, P. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Ce0.95Pr0.05−xMxO2 (M = Mn, Si) as Potential Ecological Red Pigments for Coloration of Plastics. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 4009–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovaní, M.; Sanz, A.; Beltrán-Mir, H.; Cordoncillo, E. New Red-Shade Environmental-Friendly Multifunctional Pigment Based on Tb and Fe Doped Y2Zr2O7 for Ceramic Applications and Cool Roof Coatings. Dye. Pigm. 2016, 133, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, S.; Tena, M.A.; Gargori, C.; Badenes, J.A.; Llusar, M.; Monrós, G. Structure and Colour of Cobalt Ceramic Pigments from Phosphates. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serment, B.; Corucho, L.; Demourgues, A.; Hadziioannou, G.; Brochon, C.; Cloutet, E.; Gaudon, M. Tailoring the Chemical Composition of LiMPO4 (M = Mg, Co, Ni) Orthophosphates To Design New Inorganic Pigments from Magenta to Yellow Hue. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 7499–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Osorio, A.; Pineda-Villanueva, E.; Chávez-Fernández, J. Synthesis of Nanosized (Zn1−xCox)Al2O4 Spinels: New Pink Ceramic Pigments. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccichè, F.; Oostveen, E.; Haveren, J.V.; Linde, R.V.D. The Combination of Reducing Agents/Iron as Environmentally Friendlier Alternatives for Co-Based Driers in the Drying of Alkyd Paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 2005, 53, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uner, D.; Demirkol, M.K.; Dernaika, B. A Novel Catalyst for Diesel Soot Oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2005, 61, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías, M.; Sánchez De Rojas, M.I. Total and Soluble Chromium, Nickel and Cobalt Content in the Main Materials Used in the Manufacturing of Spanish Commercial Cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, N.V.; Wigley, F.; Williamson, J. Microstructural Changes to Metal Bond Coatings on Gas Turbine Alloys with Time at High Temperature. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llusar, M.; Vitásková, L.; Šulcová, P.; Tena, M.A.; Badenes, J.A.; Monrós, G. Red Ceramic Pigments of Terbium-Doped Ceria Prepared through Classical and Non-Conventional Coprecipitation Routes. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 30, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llusar, M.; Forés, A.; Badenes, J.A.; Calbo, J.; Tena, M.A.; Monrós, G. Colour Analysis of Some Cobalt-Based Blue Pigments. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 21, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.S.; Shama, S.A.; Moustafa, M.M.; Dessouki, H.A.; Ali, A.A. Synthesis and Spectral Characterization of CoxMg1−xAl2O4 as New Nano-Coloring Agent of Ceramic Pigment. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 74, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, L.; Duttine, M.; Gaudon, M.; Demourgues, A. Cobalt–Zinc Molybdates as New Blue Pigments Involving Co2+ in Distorted Trigonal Bipyramids and Octahedra. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 2419–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodylova, N.; Kosinová, V.; Dohnalová, Ž.; Bělina, P.; Šulcová, P. New Purple-Blue Ceramic Pigments Based on CoZr4(PO4)6. Dye. Pigm. 2013, 98, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erič, S.; Kostić-Gvozdenović, L.; Miladinović, M.; Pavlović, L. Synthesis of cobalt-based ceramic pigments from industrial waste materials. Ceramics-Silikáty 1990, 34, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R.; Quan, G.; Shi, Z.; Luo, Z.; Hu, Q.; Guo, S. A Double Perovskite Ca2MgWO6:Bi3+ Yellow-Emitting Phosphor: Synthesis and Luminescence Properties. J. Lumin. 2017, 181, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, T.; Cao, L.; Meng, J. Fluorescence Property of Novel Near-Infrared Phosphor Ca2MgWO6:Cr3+. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 731, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Hu, F.; Wei, R.; Guo, H. A Three-Mode Self-Referenced Optical Thermometry Based on up-Conversion Luminescence of Ca2MgWO6:Er3+, Yb3+ Phosphors. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhu, X.; Daniel, J.; Gao, X.; Sun, S.; Gao, C.; Bao, J. Enhanced Photocatalytic Oxygen Evolution over Mo-Doped Ca2NiWO6 Perovskite Photocatalyst under Visible Light Irradiation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 5821–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zheng, J.; Zou, Z. Band Structure and Photocatalytic Properties of Perovskite-Type Compound Ca2NiWO6 for Water Splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2006, 67, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Hall, W.H. X-Ray Line Broadening from Filed Aluminium and Wolfram. Acta Metall. 1953, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Zhong, J.; Xu, H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Hu, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, M.; Xu, X.; Zhou, W.; et al. A Universal Chemical-Induced Tensile Strain Tuning Strategy to Boost Oxygen-Evolving Electrocatalysis on Perovskite Oxides. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2022, 9, 011422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. 1976, A32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Massignan, C.; Daolio, S.; Fabrizio, M.; Piccirillo, C.; Armelao, L.; Tondello, E. Composition and Microstructure of Cobalt Oxide Thin Films Obtained from a Novel Cobalt(II) Precursor by Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xue, D. Estimation of Electronegativity Values of Elements in Different Valence States. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 11332–11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauc, J.; Grigorovici, R.; Vancu, A. Optical Properties and Electronic Structure of Amorphous Germanium. Phys. Stat. Sol. 1966, 15, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Shi, R.; Jiao, K.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; et al. Hydrogen Society: From Present to Future. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4926–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| x | L* | a* | b* | C | h° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 96.4 | +0.70 | −0.08 | 0.70 | 353 |

| 0.10 | 86.5 | +5.05 | +12.3 | 13.3 | 67.7 |

| 0.15 | 83.1 | +6.12 | +14.9 | 16.1 | 67.7 |

| 0.20 | 78.8 | +8.24 | +18.2 | 20.0 | 65.6 |

| 0.25 | 75.0 | +9.57 | +22.3 | 24.3 | 66.8 |

| 0.30 | 71.0 | +12.3 | +25.6 | 28.4 | 64.3 |

| 0.40 | 67.0 | +11.4 | +25.0 | 27.7 | 65.5 |

| 0.50 | 62.7 | +12.3 | +23.0 | 26.0 | 61.9 |

| Samples | Eg/eV |

|---|---|

| Co10Mo0 | 1.99 |

| Co10Mo45 | 1.86 |

| Co10Mo50 | 1.84 |

| Co10Mo55 | 1.83 |

| Co10Mo60 | 1.82 |

| Co15Mo0 | 1.99 |

| Co15Mo45 | 1.81 |

| Co15Mo50 | 1.80 |

| Co15Mo55 | 1.79 |

| Co15Mo60 | 1.78 |

| Co20Mo0 | 1.97 |

| Co20Mo45 | 1.80 |

| Co20Mo50 | 1.78 |

| Co20Mo55 | 1.77 |

| Co20Mo60 | 1.75 |

| Co25Mo0 | 1.97 |

| Co25Mo45 | 1.79 |

| Co25Mo50 | 1.78 |

| Co25Mo55 | 1.75 |

| Co25Mo60 | 1.74 |

| Co30Mo0 | 1.97 |

| Co30Mo45 | 1.77 |

| Co30Mo50 | 1.75 |

| Co30Mo55 | 1.74 |

| Co30Mo60 | 1.73 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | C | h° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co10Mo0 | 86.5 | +5.05 | +12.3 | 13.3 | 67.7 |

| Co10Mo45 | 40.4 | +26.3 | +31.3 | 40.9 | 50.0 |

| Co10Mo50 | 36.8 | +24.8 | +23.6 | 34.2 | 43.6 |

| Co10Mo55 | 36.0 | +25.8 | +24.0 | 35.2 | 42.9 |

| Co10Mo60 | 37.2 | +24.5 | +24.2 | 34.4 | 44.6 |

| Co15Mo0 | 83.1 | +6.12 | +14.9 | 16.1 | 67.7 |

| Co15Mo45 | 35.0 | +24.8 | +20.7 | 32.3 | 39.9 |

| Co15Mo50 | 31.2 | +22.3 | +15.0 | 26.9 | 33.9 |

| Co15Mo55 | 31.1 | +22.1 | +14.6 | 26.5 | 33.5 |

| Co15Mo60 | 29.8 | +21.6 | +13.4 | 25.4 | 31.8 |

| Co20Mo0 | 78.8 | +8.24 | +18.2 | 20.0 | 65.6 |

| Co20Mo45 | 31.0 | +22.9 | +17.1 | 28.6 | 36.7 |

| Co20Mo50 | 30.0 | +20.2 | +11.7 | 23.3 | 30.1 |

| Co20Mo55 | 27.9 | +19.2 | +10.6 | 21.9 | 28.9 |

| Co20Mo60 | 28.2 | +19.0 | +10.3 | 21.6 | 28.5 |

| Co25Mo0 | 75.0 | +9.57 | +22.3 | 24.3 | 66.8 |

| Co25Mo45 | 29.7 | +21.9 | +13.7 | 25.8 | 32.0 |

| Co25Mo50 | 26.3 | +20.2 | +11.8 | 23.4 | 30.3 |

| Co25Mo55 | 25.4 | +15.9 | +7.53 | 17.6 | 25.3 |

| Co25Mo60 | 25.7 | +16.3 | +7.64 | 18.0 | 25.1 |

| Co30Mo0 | 71.0 | +12.3 | +25.6 | 28.4 | 64.3 |

| Co30Mo45 | 27.0 | +16.0 | +6.86 | 17.4 | 23.2 |

| Co30Mo50 | 25.4 | +14.4 | +5.46 | 15.4 | 20.8 |

| Co30Mo55 | 25.5 | +14.3 | +5.54 | 15.3 | 21.2 |

| Co30Mo60 | 25.4 | +10.8 | +3.24 | 11.3 | 16.7 |

| Samples | L* | a* | b* | h° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co15Mo50 | 31.2 | +22.3 | +15.0 | 33.9 |

| Bengal red (Fe2O3) | 36.7 | +33.1 | +25.0 | 37.0 |

| Vermillion (HgS) | 53.5 | +55.6 | +42.9 | 37.7 |

| Cadmium red (CdS·CdSe) | 54.0 | +61.8 | +55.3 | 41.8 |

| Treatment | L* | a* | b* | C | h° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As synthesized | 31.2 | +22.3 | +15.0 | 26.9 | 33.9 |

| 4% CH3COOH | 39.8 | +22.0 | +21.6 | 30.8 | 44.5 |

| 4% NH4HCO3 | 40.2 | +20.2 | +22.0 | 28.4 | 44.7 |

| Sample | Ca(NO3)2·4H2O | Mg(NO3)2·6H2O | Co(NO3)2·6H2O | WO3 | CA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2MgWO6 | 1.2290 g | 0.6672 g | - | 0.6033 g | 3.9994 g |

| Co10 | 1.2180 g | 0.5951 g | 0.0751 g | 0.5979 g | 3.9637 g |

| Co15 | 1.2126 g | 0.5296 g | 0.1121 g | 0.5952 g | 3.9460 g |

| Co20 | 1.2072 g | 0.5243 g | 0.1488 g | 0.5926 g | 3.9286 g |

| Co25 | 1.2019 g | 0.4894 g | 0.1852 g | 0.5900 g | 3.9113 g |

| Co30 | 1.1966 g | 0.4548 g | 0.2212 g | 0.5874 g | 3.8941 g |

| Co40 | 1.1862 g | 0.3864 g | 0.2924 g | 0.5823 g | 3.8602 g |

| Co50 | 1.1760 g | 0.3192 g | 0.3623 g | 0.5773 g | 3.8269 g |

| Sample | Ca(NO3)2·4H2O | Mg(NO3)2·6H2O | Co(NO3)2·6H2O | WO3 | MoO3 | CA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co10Mo45 | 1.3564 g | 0.6627 g | 0.0836 g | 0.3662 g | 0.1860 g | 4.4139 g |

| Co10Mo50 | 1.3737 g | 0.6712 g | 0.0846 g | 0.3372 g | 0.2093 g | 4.4703 g |

| Co10Mo55 | 1.3915 g | 0.6799 g | 0.0857 g | 0.3074 g | 0.2333 g | 4.5281 g |

| Co10Mo60 | 1.4097 g | 0.6888 g | 0.0869 g | 0.2768 g | 0.2578 g | 4.5875 g |

| Co15Mo45 | 1.3496 g | 0.6228 g | 0.1247 g | 0.3644 g | 0.1851 g | 4.3920 g |

| Co15Mo50 | 1.3668 g | 0.6338 g | 0.1263 g | 0.3355 g | 0.2083 g | 4.4479 g |

| Co15Mo55 | 1.3844 g | 0.6388 g | 0.1280 g | 0.3058 g | 0.2321 g | 4.5051 g |

| Co15Mo60 | 1.4025 g | 0.6472 g | 0.1296 g | 0.2754 g | 0.2565 g | 4.5640 g |

| Co20Mo45 | 1.3430 g | 0.5833 g | 0.1655 g | 0.3626 g | 0.1842 g | 4.3704 g |

| Co20Mo50 | 1.3600 g | 0.5907 g | 0.1676 g | 0.3338 g | 0.2073 g | 4.4257 g |

| Co20Mo55 | 1.3774 g | 0.5982 g | 0.1698 g | 0.3043 g | 0.2309 g | 4.4824 g |

| Co20Mo60 | 1.3953 g | 0.6060 g | 0.1720 g | 0.2740 g | 0.2552 g | 4.5406 g |

| Co25Mo45 | 1.3364 g | 0.5442 g | 0.2059 g | 0.3607 g | 0.1833 g | 4.3490 g |

| Co25Mo50 | 1.3532 g | 0.5510 g | 0.2085 g | 0.3321 g | 0.2062 g | 4.4037 g |

| Co25Mo55 | 1.3705 g | 0.5580 g | 0.2111 g | 0.3027 g | 0.2297 g | 4.4599 g |

| Co25Mo60 | 1.3882 g | 0.5652 g | 0.2139 g | 0.2726 g | 0.2539 g | 4.5175 g |

| Co30Mo45 | 1.3299 g | 0.5054 g | 0.2458 g | 0.3590 g | 0.1824 g | 4.3278 g |

| Co30Mo50 | 1.3466 g | 0.5117 g | 0.2489 g | 0.3305 g | 0.2052 g | 4.3820 g |

| Co30Mo55 | 1.3637 g | 0.5182 g | 0.2521 g | 0.3012 g | 0.2286 g | 4.4376 g |

| Co30Mo60 | 1.3812 g | 0.5249 g | 0.2553 g | 0.2712 g | 0.2526 g | 4.4946 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamaguchi, K.; Minagawa, K.; Oka, R.; Masui, T. Control of Optical Reflection in Ca2MgWO6 by Co and Mo Doping. Molecules 2024, 29, 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29081886

Yamaguchi K, Minagawa K, Oka R, Masui T. Control of Optical Reflection in Ca2MgWO6 by Co and Mo Doping. Molecules. 2024; 29(8):1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29081886

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamaguchi, Kazuki, Kohei Minagawa, Ryohei Oka, and Toshiyuki Masui. 2024. "Control of Optical Reflection in Ca2MgWO6 by Co and Mo Doping" Molecules 29, no. 8: 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29081886

APA StyleYamaguchi, K., Minagawa, K., Oka, R., & Masui, T. (2024). Control of Optical Reflection in Ca2MgWO6 by Co and Mo Doping. Molecules, 29(8), 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29081886