Abstract

In this work, the first review paper about bis-iridoids was presented. In particular, their detailed occurrence, chemophenetic evaluation and biological activities were reported. To the best of our knowledge, two hundred and eighty-eight bis-iridoids have been evidenced so far, bearing different structural features, with the link between two seco-iridoids sub-units as the major one. Different types of base structures have been found, with catalpol, loganin, paederosidic acid, olesoide methyl ester, secoxyloganin and loganetin as the major ones. Even bis-irdioids with non-conventional structures like intra-cyclized and non-alkene six rings have been reported. Some of these compounds have been individuated as chemophenetic markers at different levels, such as cantleyoside, laciniatosides, sylvestrosides, GI-3, GI-5, oleonuezhenide, (Z)-aldosecologanin and centauroside. Only one hundred and fifty-nine bis-iridoids have been tested for their biological effects, including enzymatic, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitumoral and anti-inflammatory. Sylvestroside I was the compound with the highest number of biological tests, whereas cantleyoside was the compound with the highest number of specific biological tests. Bis-iridoids have not always shown activity, and when active, their effectiveness values have been both higher and lower than the positive controls, if present. All these aspects have been deeply discussed in this paper, which also shows some critical issues and even suggests possible arguments for future research, since there is still a lot unknown about bis-iridoids.

1. Introduction

Bis-iridoids are a sub-class of iridoids characterized by the link of two iridoidic sensu lato sub-units to form a bigger molecule. Actually, these sub-units may be extremely different, and the bond may occur in different positions of both the sub-units, including the glucose moiety but also after conjugation with other classes of natural compounds like phenolics and terpenes to act as a bridge between them [1,2,3,4,5].

They are biosynthesized following the general route for the biosynthesis of simple iridoids and seco-iridoids but with the further passage of the intermolecular bond of the two sub-units alone or after conjugation with bridges [6].

In the literature, there is no specific review paper on bis-iridoids, whereas several review papers have dealt with the topic of iridoids in general on several aspects [1,2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10].

In this review paper, the occurrence, chemophenetic value and biological activities of bis-iridoids are presented and discussed in detail. The literature search was conducted on renowned scientific databases such as PubMed, PubChem, Google Scholar and Reaxys using keywords like bis-iridoid, bis-iridoids, occurrence, biological activities alone or together and specific names of compounds or plant species, as recovered from previous papers. All the papers written in English in spite of their publication year and journal were considered. Not fully accessible papers were also included. Indeed, all the papers not concerning plant species, concerning a mixture of plants where the identification of this type of compounds has not been clearly attributed, deriving from cell cultures or from sure enhancement of their production in a botanical or biotechnological manner, were neglected.

2. Occurrence of Bis-Iridoids in Plants

Table 1 reports on the occurrence of bis-iridoids in plants in alphabetical order. In this, the organs of the plants where they have been recovered and the collection area of the species, as well as the methodologies adopted for their extraction, separation and identification, are also presented.

Table 1.

List of all the identified bis-iridoids in plants.

To the best of our knowledge, two hundred and eighty-eight bis-iridoids have been identified in plants, so far. Sixty are structurally characterized by the link between two iridoid sub-units, fifty-four by the link between one iridoid sub-unit and one seco-iridoid sub-unit, ninety-two by the link between two seco-iridoid sub-units, nine by the link between two non-glucosidic iridoid sub-units, eleven by the link between one non-glucosidic iridoid sub-unit and one non-glucosidic seco-iridoid sub-unit, six by the link between one iridoid sub-unit and one non-glucosidic iridoid sub-unit, thirty-four by the link between one non-glucosidic iridoid sub-unit and one seco-iridoid sub-unit, twenty-two by a non-conventional bis-iridoid structure. By consequence, bis-iridoids with two seco-iridoid sub-units are the most abundant, whereas bis-iridoids with one iridoid sub-unit and one non-glucosidic iridoid sub-unit are the least abundant.

Different types of iridoid, seco-iridoid and non-glucosidic iridoid base structures are used to form bis-iridoids. Catalpol, loganic acid, loganin and paederosidic acid, together with their derivatives, are the most common for iridoids, whereas oleoside methyl ester and secoxyloganin, together with their derivatives, are the most common for seco-iridoids and loganetin, together with its derivatives, is the most common for non-glucosidic iridoids. Other present base structures for iridoids include 8-O-acetyl-harpagide, adoxoside, arborescoside, ajugoside, anthirride, anthirrinoside, aucubin, euphroside, gardenoside, gardoside, geniposide, scandoside and their derivatives. Other present base structures for seco-iridoids include morronoside, seco-loganol, seco-loganoside, swertiamarin, 9-oxo-swerimuslactone A and their derivatives. Other present base structures for non-glucosidic iridoids include iso-boonein, alyxialactone and their derivatives. Indeed, among the non-conventional bonds, there are intra-cyclic bis-iridoids, bonds with differently functionalized five carbon rings fused with other rings or not, and bonds with iridoids deprived of their classical double bond between carbons 3 and 4. From a specific observation of these base structures, it can be easily established that not all the existing base structures for iridoids, seco-iridoids and non-glucosidic iridoids are present in bis-iridoids, as well as not all the possible non-conventional bonds, and this may, indeed, represent an interesting research line for the future.

For what concerns the general structures of bis-iridoids, the literature survey has displayed some important issues. The first one regards the real existence of compounds having methyl, ethyl and dimethyl acetal groups, like in abelioside A methyl acetal, abeliforoside C, abeliforoside E, cantleyoside dimethyl acetal, cocculoside, dipsanoside J, saugmaygasoside D, sylvestroside III dimethyl acetal, sylvestroside IV dimethyl acetal, triplostoside A and tripterospermumcin B methyl acetal or having methyl ester, ethyl and butyl groups, like in aldosecolohanin B, atropurpurins A–B, pterocesides A–C, cornuside K, hookerinoid A, hookerinoid B, pterhookeroside and tricoloroside methyl ester. Given the methodologies adopted for their extraction and isolation, these compounds are likely to be artifacts [239], even if they are often found, thus evidencing their extreme ease of formation. Yet, these have not been considered as artifacts but as natural. It is not very simple to establish which is correct, but this whole situation can be easily solved by a simple analytical procedure constituted of steps of maceration, separation and identification using non-corresponding solvents, meaning not methanol for methyl acetal, dimethyl acetal and methyl ester compounds and not ethanol and butanol for ethylated and butylated compounds. The presence of these functional groups in the same compounds obtained following this way will be clear evidence of the fact they are not artifacts. In this sense, this topic may also be an involved line for future research. Another detected issue regards (E)-aldosecologanin and centauroside. Indeed, they are often considered as different compounds, but they present the same structure, and thus, they are the same compound. In the future, more attention must be paid to this aspect. Another issue is surely the need for major harmonization on the names of these compounds. This has been widely shown for the compounds named GI-3 and GI-5 in this paper. Actually, in others, they are named Gl-3 and Gl-5 or GL-3 and GL-5, but they are all the same. One single name for each compound is compulsory in order to avoid confusion and possible identification mistakes. Lastly, it is important to underline that most of the existing bis-iridoids have trivial names but not in a few cases: dimer of alpinoside and alpinoside, dimer of aperuloside and asperulosidic acid, dimer of nuezhenide and 11-methyl-oleoside, dimer of oleoside and 11-methyl-oleoside, dimer of paederosidic acids, dimer of paederosidic acid and paederoside, dimer of paederosidic acid and paederosidic acid methyl ester. The choice of giving trivial names to new compounds is always up to the authors, but this should always be encouraged, since it can really diminish the possibility of giving different names to the same structure, considering them to be new when they are not. The most fitting example of this is the compound named in this review as iridoid glycoside dimer I.

The most present compound in plants is cantleyoside, which has been reported in twenty-one different species belonging to ten different genera and four different families. Its highest occurrence is in four different genera (Cephalaria, Dipsacus, Pterocephalus and Strychnos), whereas, in two genera (Abelia and Lomelosia), its presence is singular. Conversely, several compounds have been found in single species. The presence of specific compounds in different species of the same genus, in different genera of the same family and in different families of the same order is extremely important, since it allows the individuation of chemophenetic markers at these levels. On the contrary, the presence of specific compounds in single species has no chemophenetic relevance due to their extremely limited distribution. The compound with the highest number of reports in the same species is centauroside in Lonicera japonica with twenty-three citations. Centauroside is also the compound with the highest number of studies for different populations of the same species (Lonicera japonica) collected in different countries. The multiple presence of the same compound at every classification level confirms that this compound is usually biosynthesized here, which is extremely important under the chemophenetic standpoint, potentially considering it as a chemophenetic marker.

For what concerns the organs of the species studied, flowers, flower buds, seeds, twigs, leaves, stems, stem bark, bark, wood, heartwood, roots and rhizomes have all been mentioned. A combination of two different organs has also been studied (stems and leaves, leaves and branches, flowers and twigs, bark and wood and roots and rhizomes), as well as more organs (whole plant, aerial parts, flowering aerial parts, foliage and underground parts). In some papers, the organs studied have been dried (generally, in the open air) prior to the phytochemical analysis, as dictated by the local Pharmacopeias (roots of Dipsacus inermis, flower buds and roots of Lonicera spp. and dried fruits of Ligustrum spp.). In all the other cases, the organs were fresh. For non-volatile secondary metabolites like bis-iridoids, the renowned issue regarding the utilization of dried or fresh organs for the phytochemical analysis is not so relevant given that they are generally stable at high temperatures but not too high [240,241].

For what concerns the collection areas of the species, all the continents are included. The highest number of reports where bis-iridoids have been found is in Asian countries, with China as the most numerous. The countries with the highest numbers of reports are Italy for Europe, Algeria for Africa, the USA for America and New Caledonia for Oceania. On the other hand, some countries (Montenegro, Namibia and Tanzania) have been mentioned only once. The number of reports for the occurrence of bis-iridoids in the plants of different territories is strictly correlated with the number of species in the territory that biosynthesize them, but it is not an absolute mirror of their worldwide distribution, since this also depends on their search. Either way, a little parallelism between the distribution of iridoids and bis-iridoids is present [242].

For what concerns the methodologies for the extraction, isolation and identification of bis-iridoids, classical procedures have been utilized. Maceration has been the most common extraction method. Column chromatography and HPLC techniques have been mostly employed as separation methodologies, whilst different spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques together have been used for the identification. All these methods are widely accepted for the analysis of non-volatile metabolites, not causing big issues, except for those previously discussed.

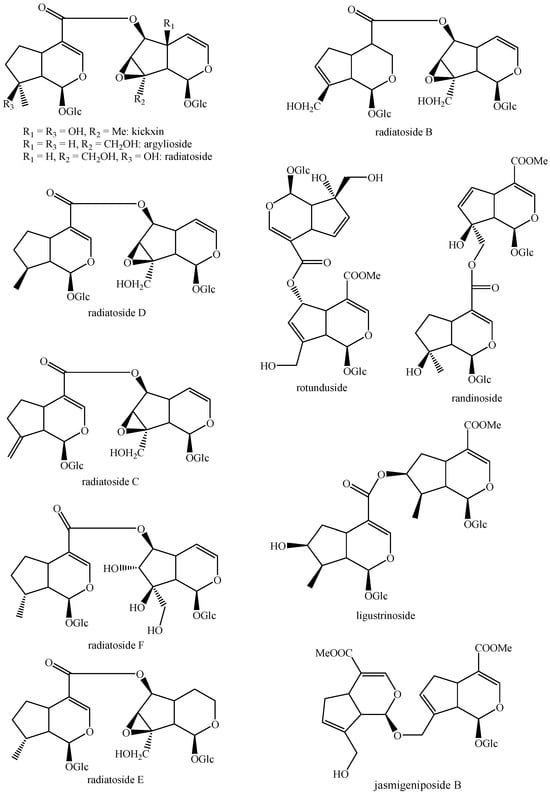

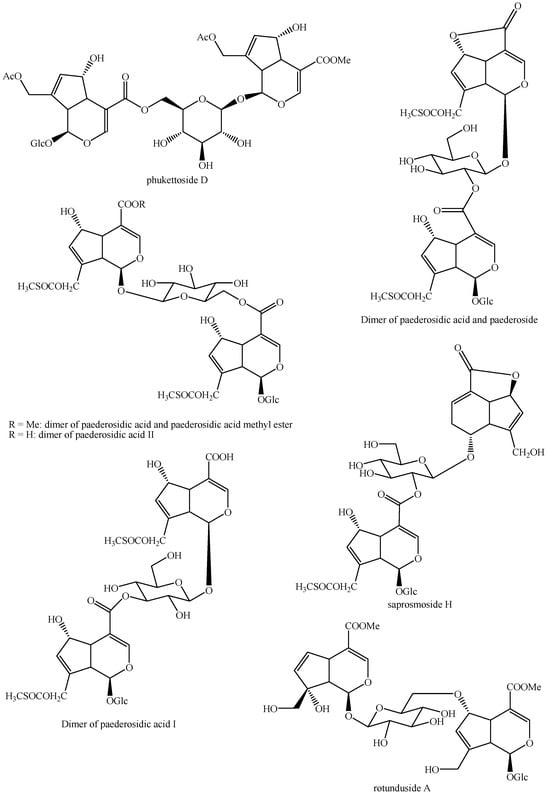

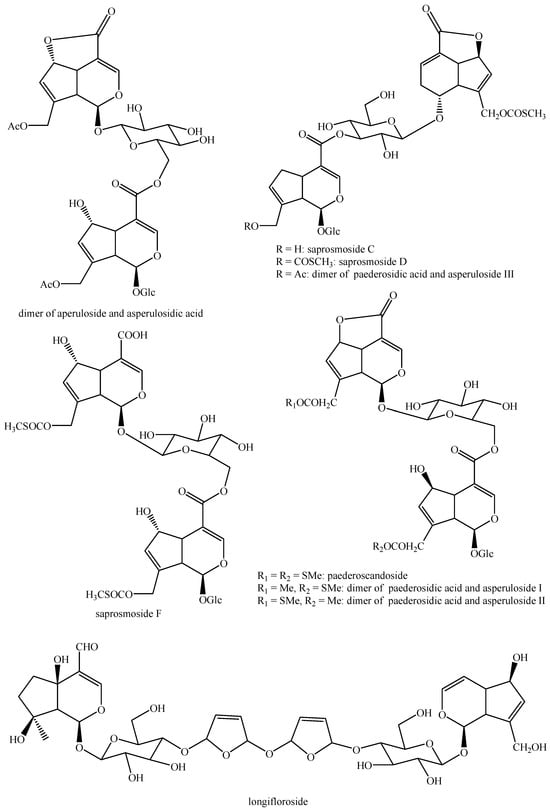

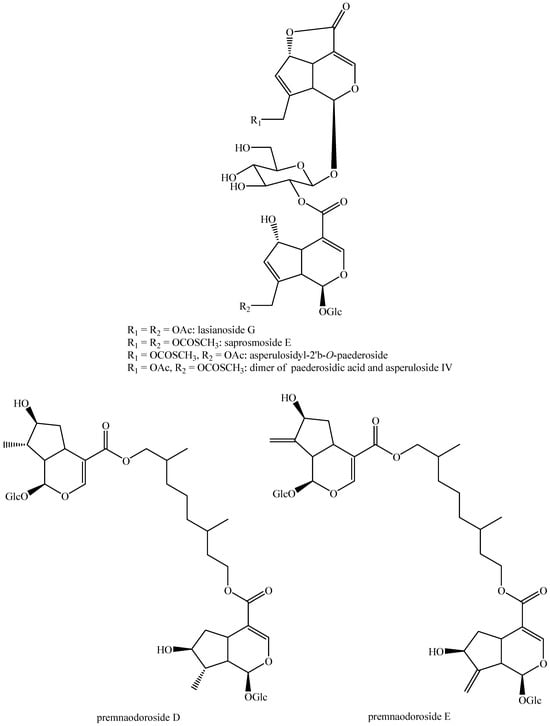

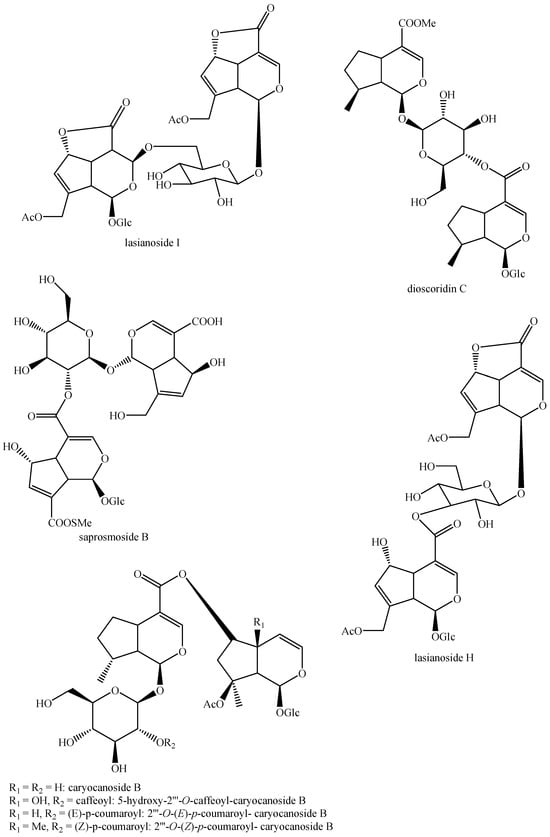

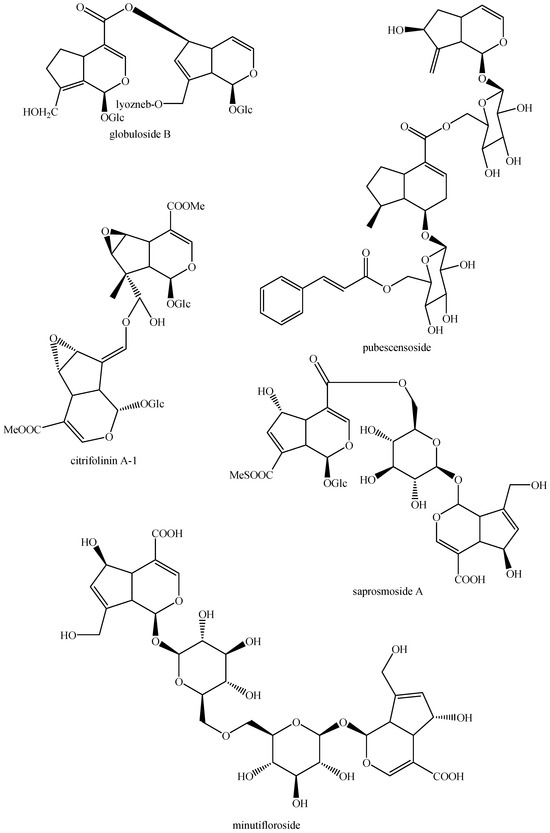

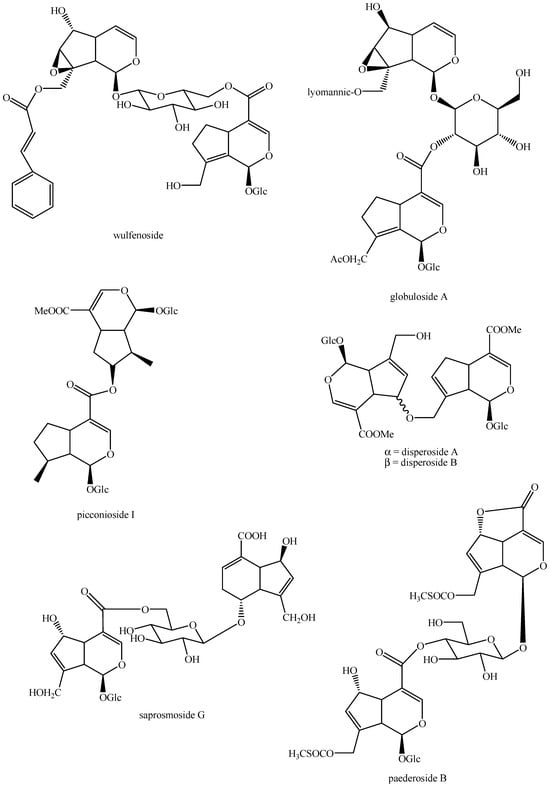

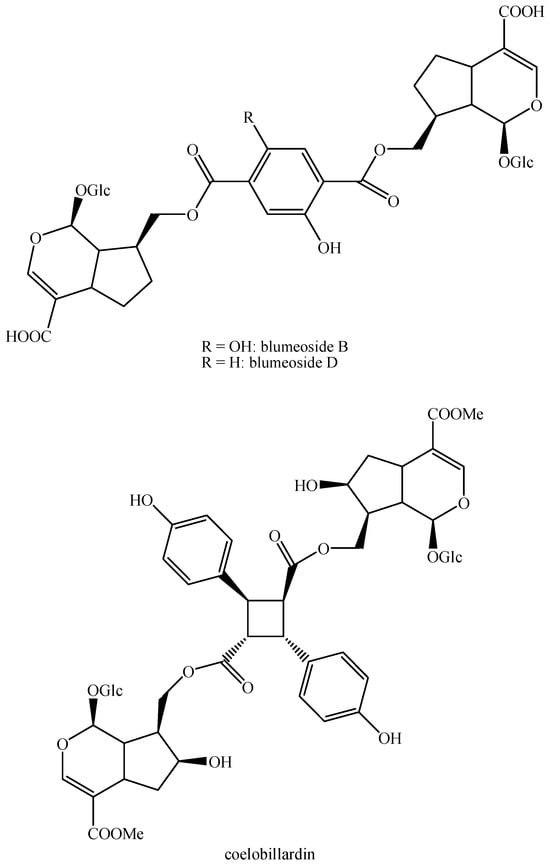

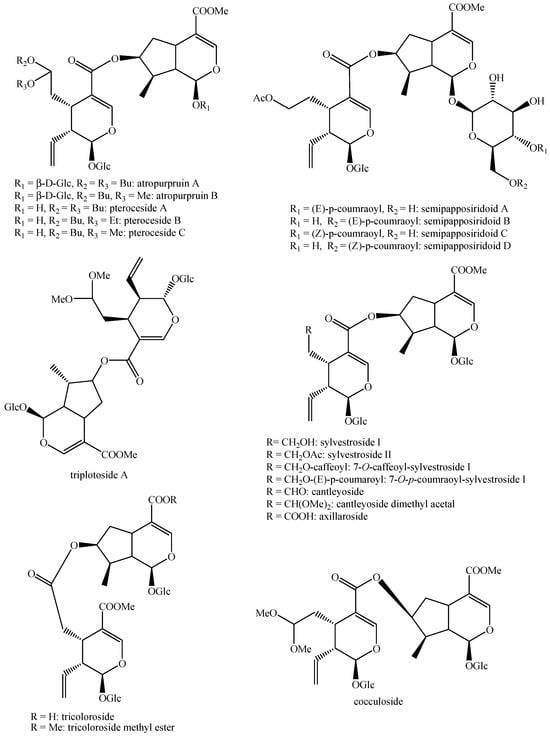

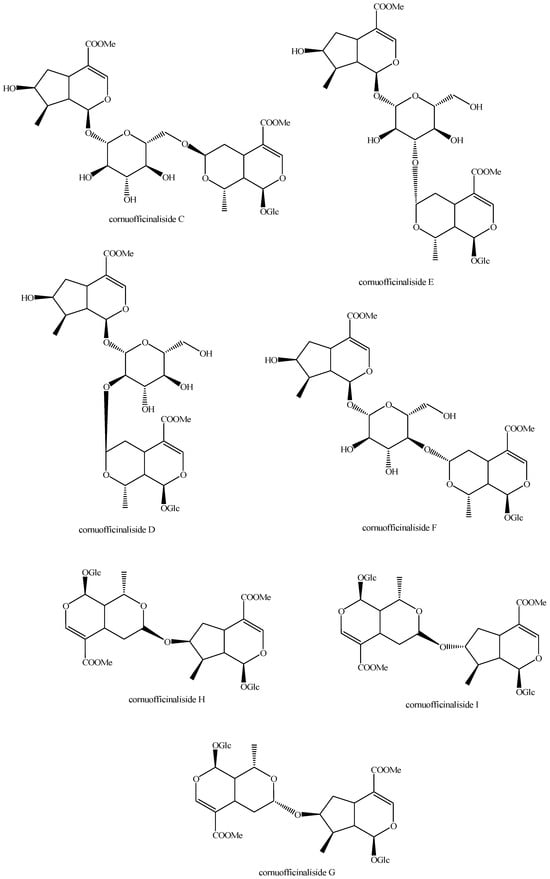

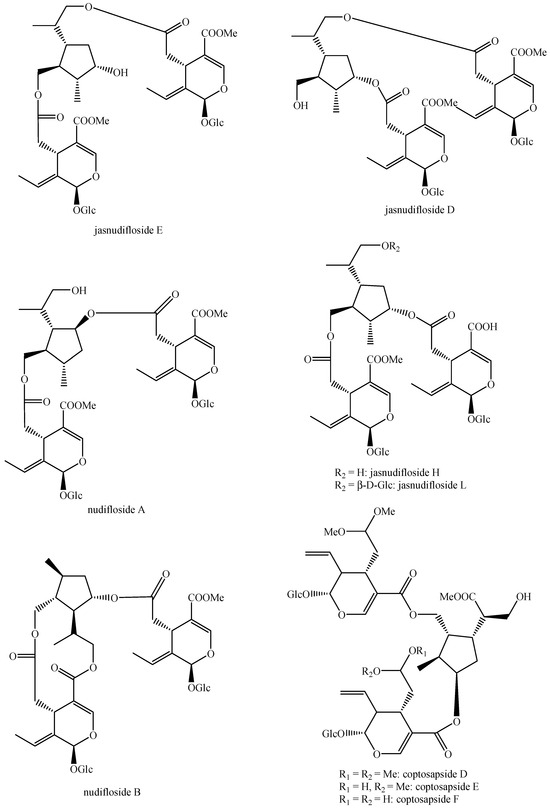

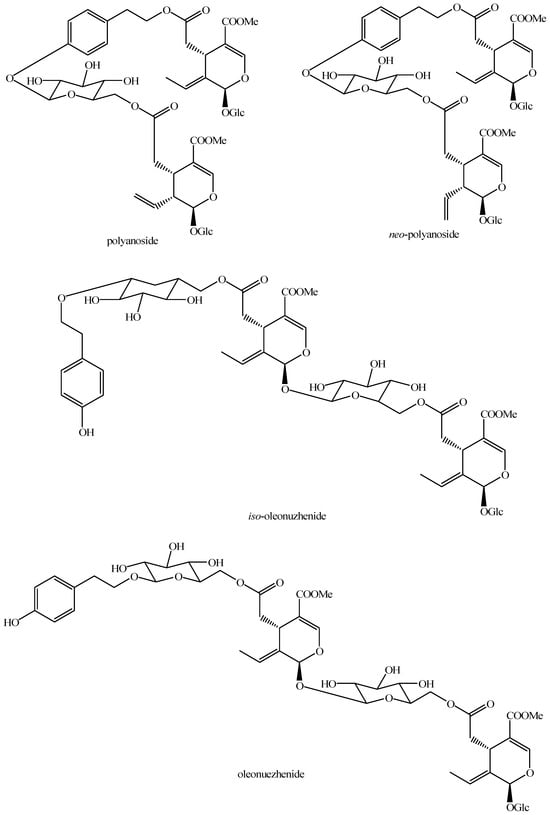

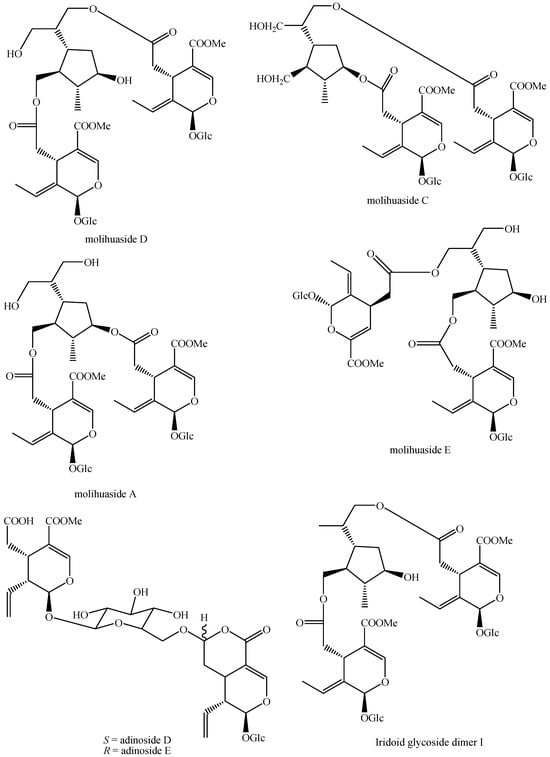

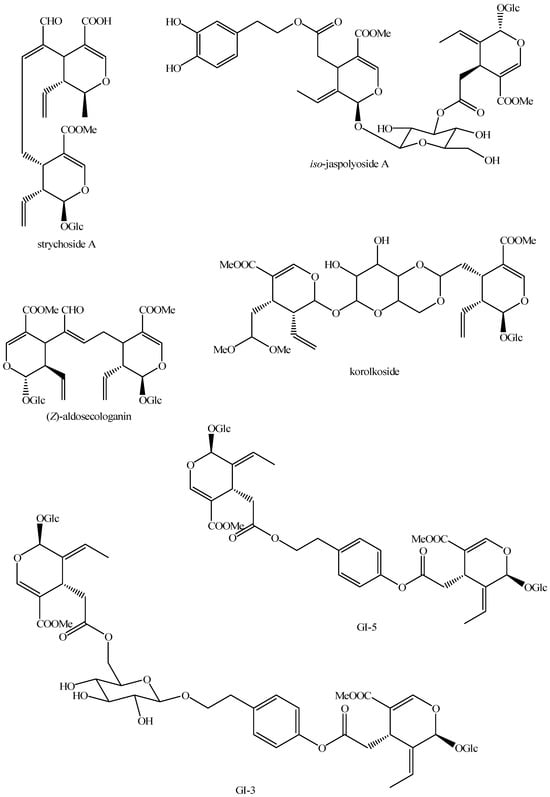

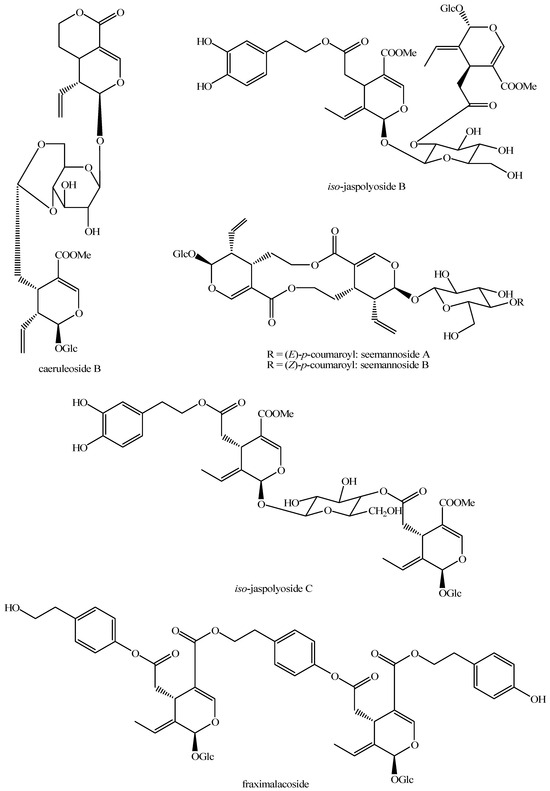

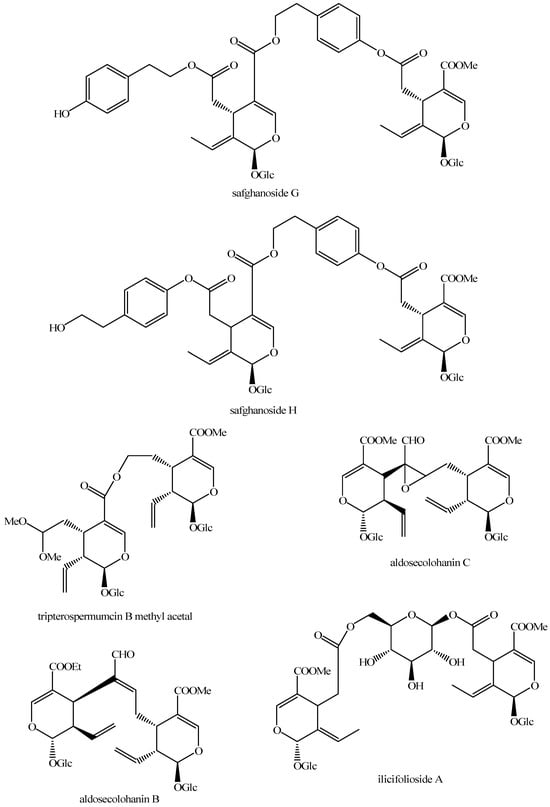

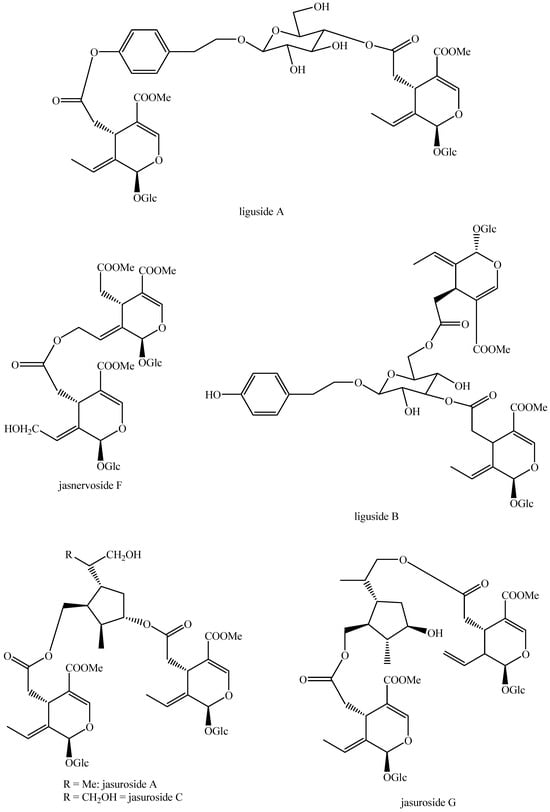

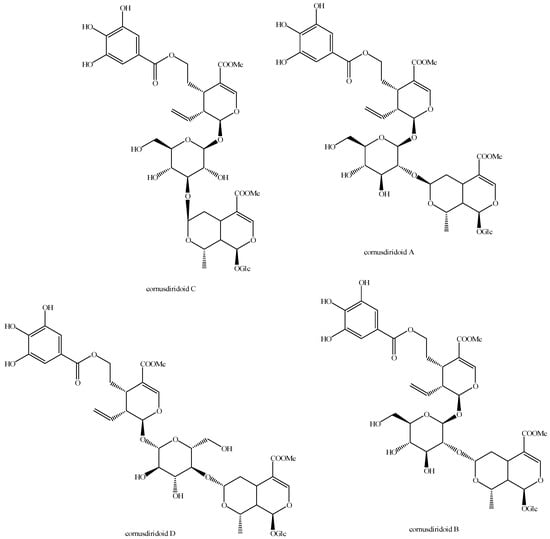

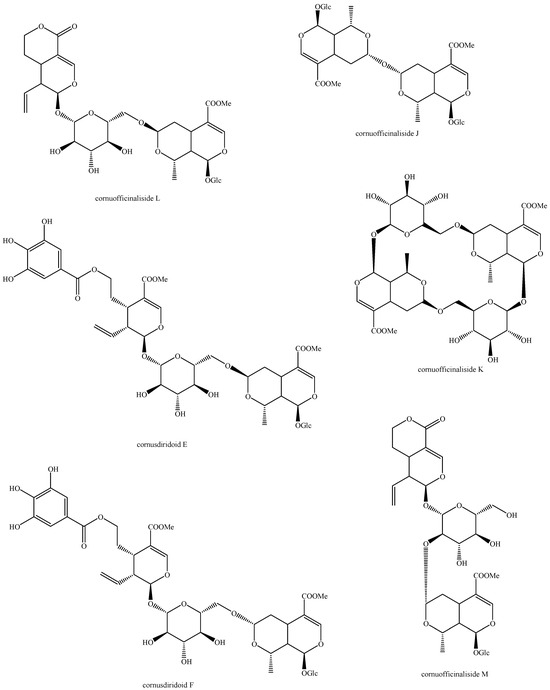

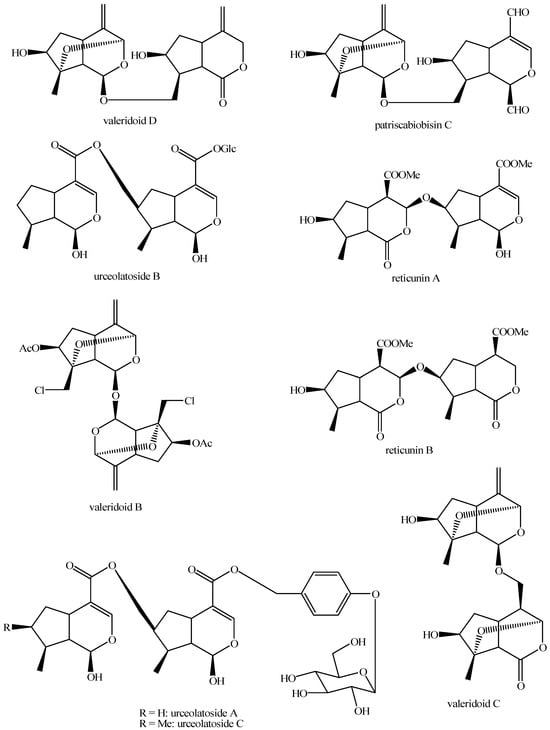

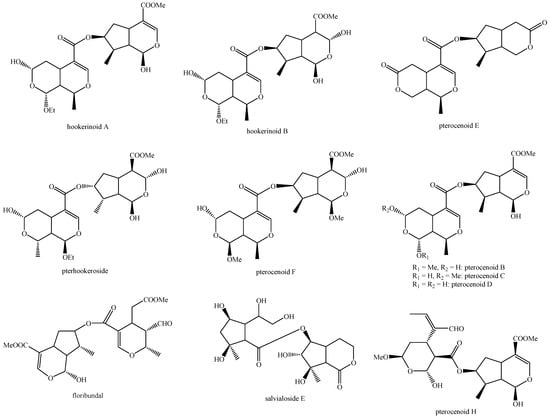

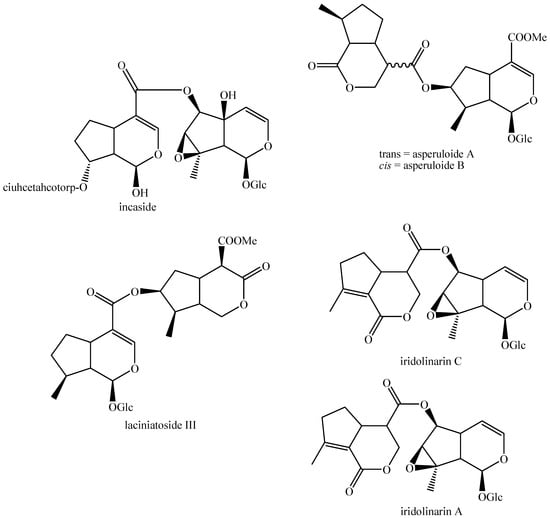

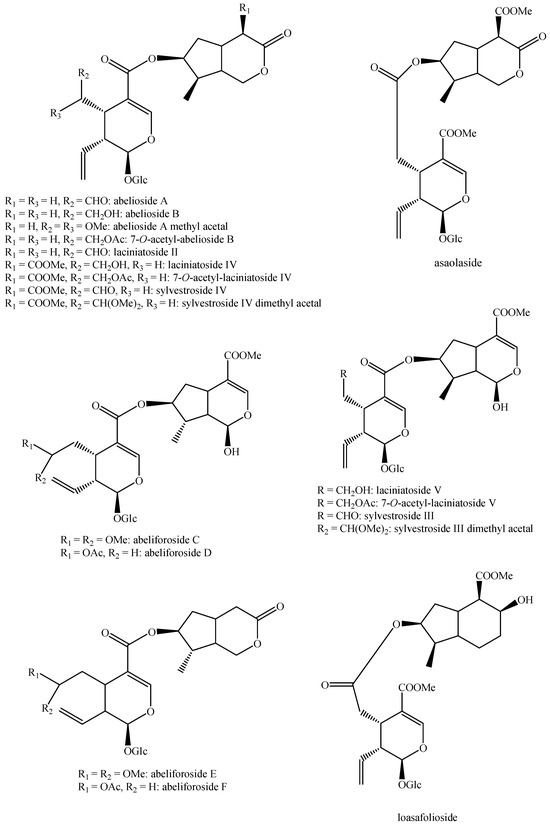

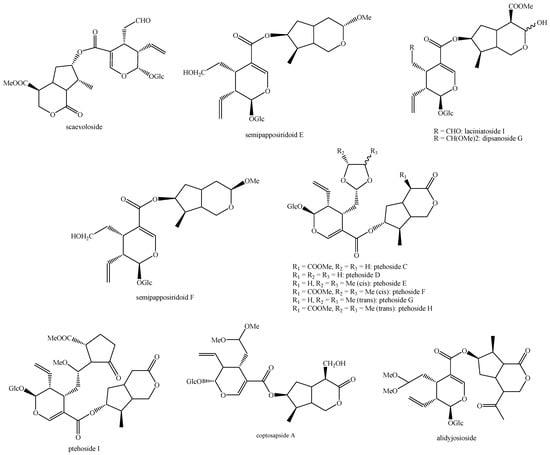

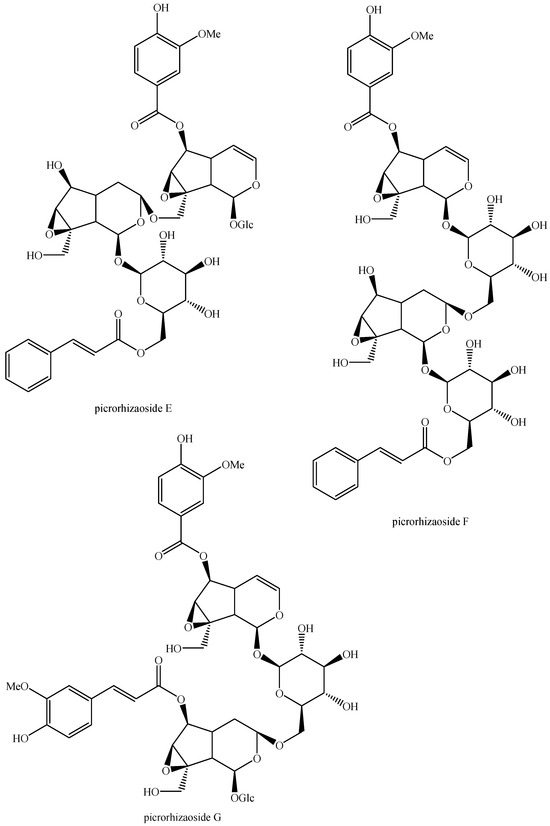

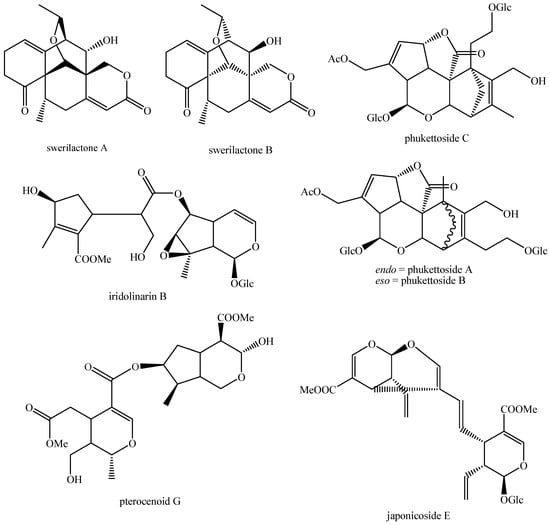

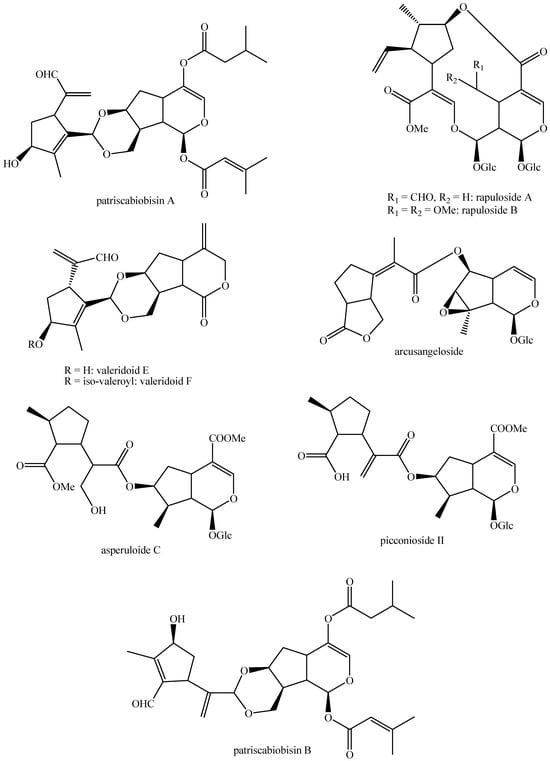

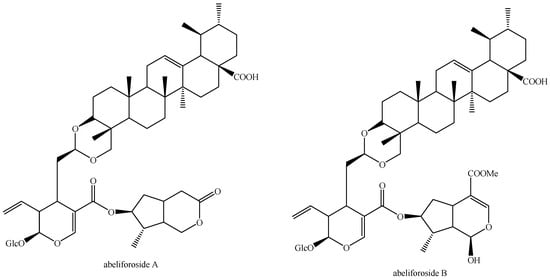

The structures of all the fully characterized bis-iridoids isolated from plants are reported in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35.

Figure 1.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 1.

Figure 2.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 2.

Figure 3.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 3.

Figure 4.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 4.

Figure 5.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 5.

Figure 6.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 6.

Figure 7.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 7.

Figure 8.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus iridoid part 8.

Figure 9.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 1.

Figure 10.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 2.

Figure 11.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 3.

Figure 12.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 4.

Figure 13.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 5.

Figure 14.

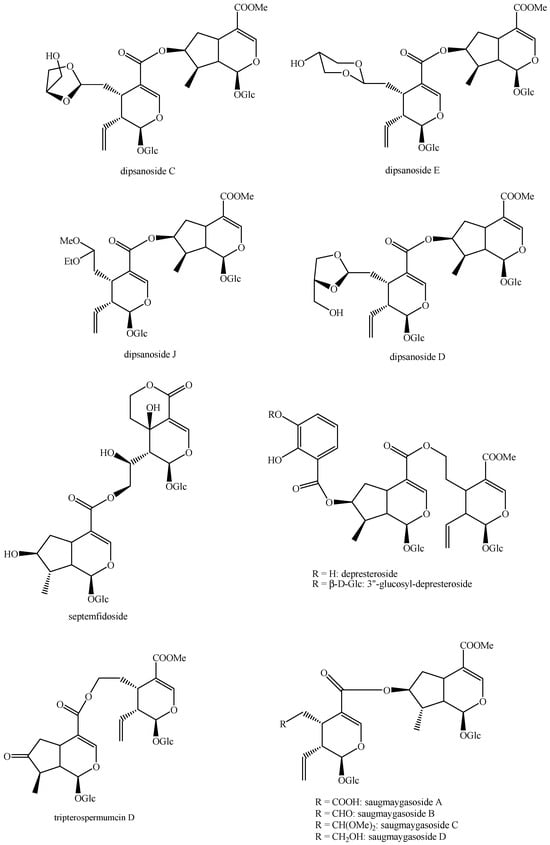

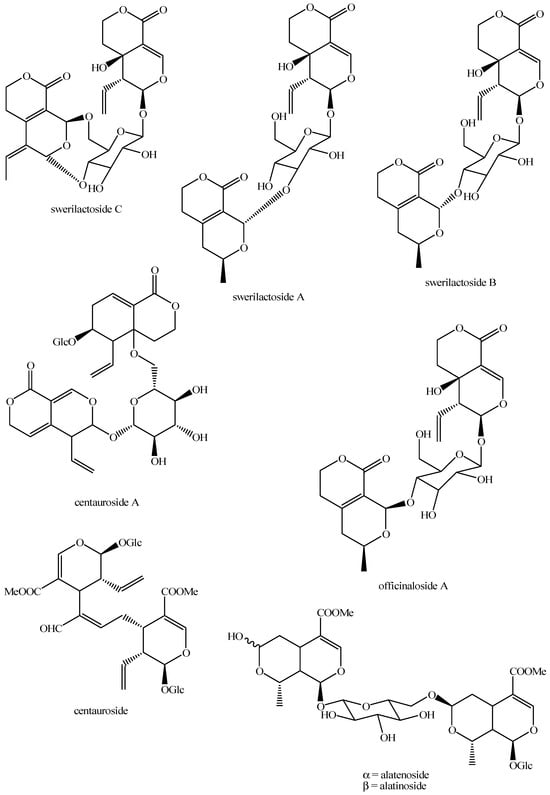

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 1.

Figure 15.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 2.

Figure 16.

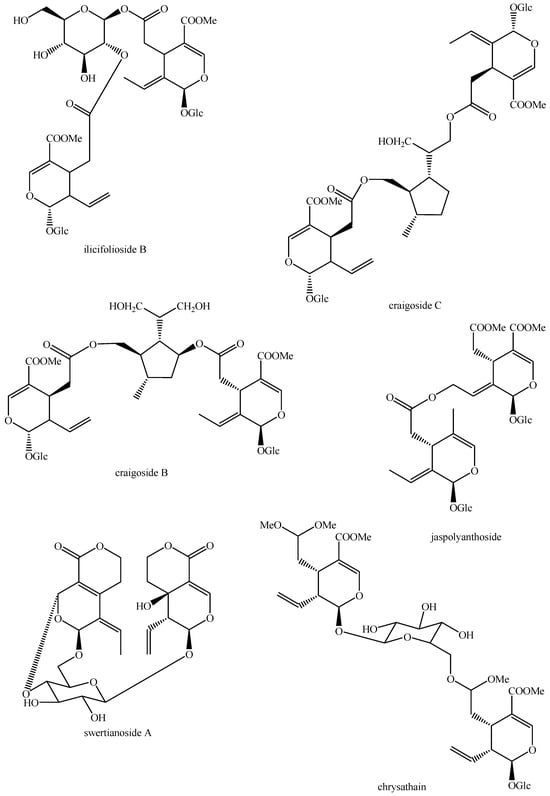

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 3.

Figure 17.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 4.

Figure 18.

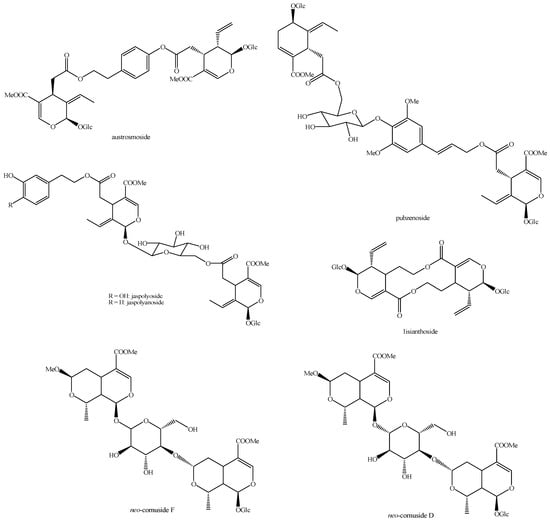

Structures bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 5.

Figure 19.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 6.

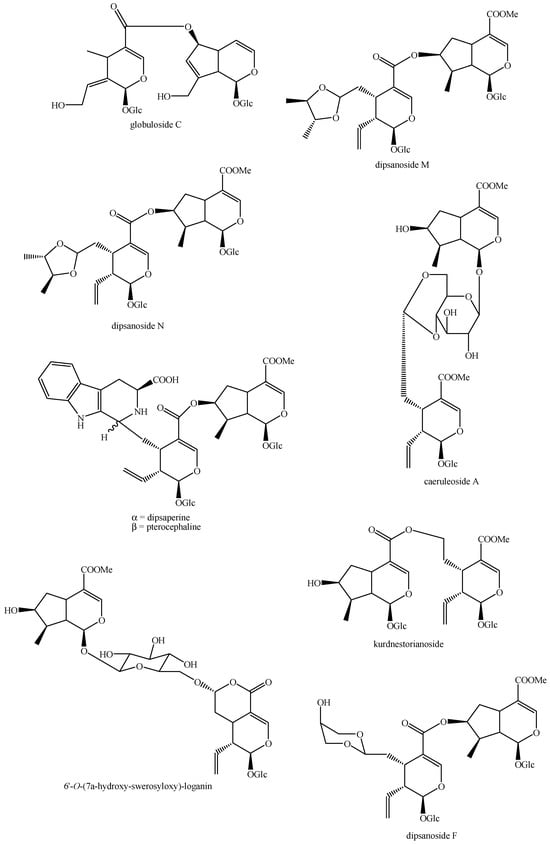

Figure 20.

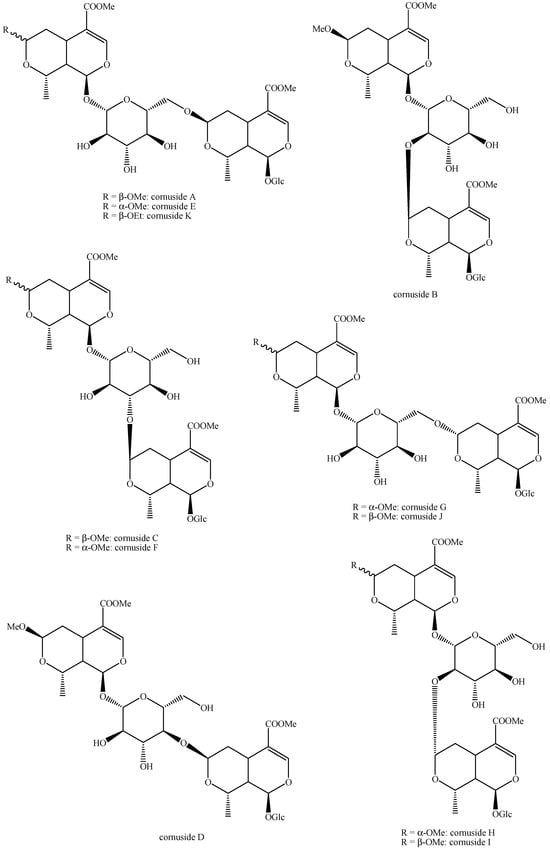

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 7.

Figure 21.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 8.

Figure 22.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 9.

Figure 23.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 10.

Figure 24.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 11.

Figure 25.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 12.

Figure 26.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—seco-iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 13.

Figure 27.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—non-glucosidic iridoid plus non-glucosidic iridoid.

Figure 28.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—non-glucosidic iridoid plus non-glucosidic seco-iridoid.

Figure 29.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—iridoid plus non-glucosidic iridoid.

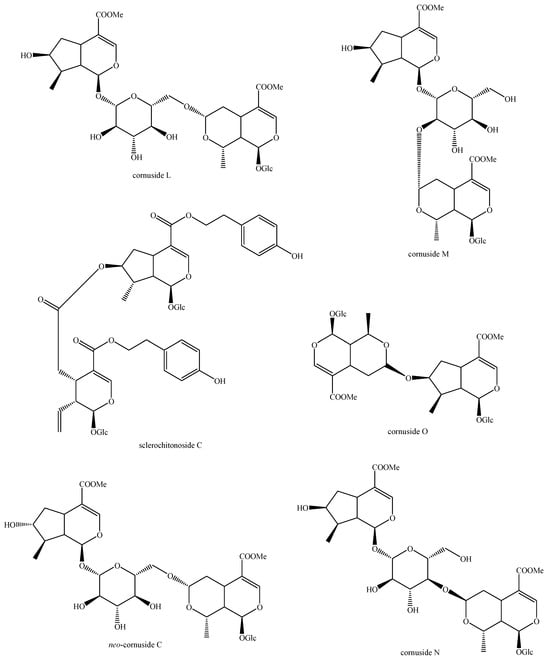

Figure 30.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—non-glucosidic iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 1.

Figure 31.

Structures of bis-iridoids in plants—non-glucosidic iridoid plus seco-iridoid part 2.

Figure 32.

Structures of non-conventional bis-iridoids in plants—part 1.

Figure 33.

Structures of non-conventional bis-iridoids in plants—part 2.

Figure 34.

Structures of non-conventional bis-iridoids in plants—part 3.

Figure 35.

Structures of non-conventional bis-iridoids in plants—part 4.

The dimer of alpinoside and alpinoside, the dimer of nuezhenide and 11-methyl-oleoside, the dimer of oleoside and 11-methyl-oleoside, demethyl-hydroxy-oleonuezhenide, demethyl-oleonuezhenide, hydroxy-oleonuezhenide and oleoneonuezhenide have not been fully characterized, and their structures have not been drawn. This may surely be an argument for future research. Additionally, the structures of premnaodoroside F and premnaodoroside G have not been drawn, since they are constituted by two isomers.

3. Chemophenetic Evaluation of Bis-Iridoids

As Table 1 clearly displays, bis-iridoids have been found in many families: Apiaceae Lindl., Aquifoliaceae Bercht. & J.Presl, Bignoniaceae Juss., Calyceraceae R.Br. ex Rich., Caprifoliaceae Juss., Cornaceae Bercht. ex J.Presl, Gentianaceae Juss., Goodeniaceae R.Br., Lamiaceae Martinov, Loasaceae Juss., Loganiaceae R.Br. ex Mart., Oleaceae Hoffmanns. & Link, Orobanchaceae Vent., Plantaginaceae Juss., Rubiaceae Juss., Sarraceniaceae Dumort., Stemonuraceae Kårehed and Viburnaceae Raf. Their highest occurrence is in Rubiaceae, reported from fourteen different genera (Adina Salisb., Catunaregam Wolf, Coelospermum Blume, Coptosapelta Korth., Galium L., Gardenia J.Ellis, Gynochthodes Blume, Lasianthus Jack, Morinda L., Mussaenda Burm. ex L., Neonauclea Merr., Paederia L., Palicourea Aubl. and Saprosma Blume), whereas the lowest was in ten families, having been reported in one only genus each (Apiaceae: Heracleum L.; Aquifoliaceae: Ilex L.; Calyceraceae: Acicarpha Juss.; Cornaceae: Cornus L.; Cyperaceae: Cyperus L.; Goodeniaceae: Scaevola L.; Loganiaceae: Strychnos L.; Orobanchaceae: Pedicularis L.; Sarraceniaceae: Sarracenia Tourn. ex L.; Stemonuraceae: Cantleya Ridl.; Viburnaceae: Viburnum L.). Bis-iridoids have been reported in two Bignoniaceae genera (Argylia D.Don and Handroanthus Mattos), in twelve Caprifoliaceae genera (Abelia Gronov., Cephalaria Schrad., Dipsacus L., Linnaea Gronov., Lomelosia Raf., Lonicera L., Patrinia Juss., Pterocephalus Vaill. ex Adans., Scabiosa L., Triosteum L., Triplostegia Wall. ex DC. and Valeriana L.), in six Gentianaceae genera (Centaurium Hill, Fagraea Thunb., Gentiana Tourn. ex L., Gentianella Moench, Swertia L. and Tripterospermum Blume), in five Lamiaceae genera (Caryopteris Bunge, Clinopodium L., Leonotis (Pers.) R.Br. and Premna L., Salvia L.), in two Loasaceae genera (Kissenia R.Br. ex Endl. and Loasa Adans.); in seven Oleaceae genera (Fraxinus Tourn. ex L., Jasminum L., Ligustrum L., Olea L., Osmanthus Lour., Picconia DC. and Syringa L.) and in six Plantaginaceae genera (Anarrhinum Desf., Globularia Tourn. ex L., Kickxia Dumort., Linaria Mill., Picrorhiza Royle ex Benth. and Wulfenia Jacq.). This occurrence is not in perfect agreement with the one for simple iridoids [242]. In fact, several families (Acanthaceae Juss., Actinidiaceae Gilg & Werderm., Apocynaceae Juss., Asteraceae Giseke, Cardiopteridaceae Blume, Celastraceae R.Br., Centroplacaceae Doweld & Reveal, Columelliaceae D.Don, Cucurbitaceae Juss., Cyperaceae Juss., Daphniphyllaceae Müll.Arg., Ericaceae Juss., Escalloniaceae R.Br. ex Dumort., Eucommiaceae Engl., Fabaceae Juss., Euphorbiaceae Juss., Fouquieriaceae DC., Garryaceae Lindl., Gel-miaceae Struwe & V.A.Albert, Gri-liniaceae J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. ex A.Cunn., Hamamelidaceae R.Br, Hydrangeaceae Dumort., Icacinaceae Miers, Lentibulariaceae Rich., Malpighiaceae Juss., Malvaceae Juss., Martyniaceae Horan., Meliaceae Juss., Menyanthaceae Dumort., Metteniusaceae H.Karst. ex Schnizl., Montiniaceae Nakai, Nyssaceae Juss. ex Dumort., Passifloraceae Juss. ex Rous-l, Paulowniaceae Nakai, Pedaliaceae R.Br., Roridulaceae Martinov, Salicaceae Mirb., Sarraceniaceae Dumort., Scrophulariaceae Juss., Stilbaceae Kunth, Stylidiaceae R.Br. Symplocaceae Desf. and Verbenaceae J.St.-Hil.) are absent from Table 1, as well as a myriad of genera [242,243,244,245], and this clearly demonstrates that bis-iridoids must be separately considered from simple iridoids for biochemical, chemophenetic and pharmacological purposes and that their biosynthesis is only due to genetic factors and not to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Simple iridoids are generally considered as chemophenetic markers at different systematic levels from subspecies to orders [242]. The order with the highest occurrence of bis-iridoids is Lamiales, presenting a certain parallelism with simple iridoids [242]. From a careful and exhaustive evaluation of Table 1, some chemophenetic markers among bis-iridoids could be individuated at different levels. In particular, given their distribution, cantleyoside, laciniatosides and sylvestrosides can be used as chemophenetic markers for the Caprifoliaceae family, GI3 and GI5 for the Oleaceae family, oleonuezhenide for the Ligustrum genus and (Z)-aldosecologanin and centauroside for the Lonicera genus. For what concerns the other compounds, some have been reported in single species, while others in too many. For this, at the moment, they do not have the necessary characteristics to act as chemophenetic markers. Yet, future phytochemical studies might be useful in this sense, providing further information.

4. Biological Activities of Bis-Iridoids

Table 2 displays the biological activities associated with bis-iridoids. These are divided according to the type of activity, considering the methods employed and the effectiveness values of bis-iridoids in comparison with the positive controls.

Table 2.

Associated biological activities of all the identified bis-iridoids in plants.

Only one hundred and fifty-nine bis-iridoids have been studied for their biological activities. The highest number of biological studies has been observed for sylvestroside I, whereas cantleyoside is the compound presenting the highest number of biological studies for the same type. Conversely, only one type of biological assay has been performed for several bis-iridoids. Among the types, not all of them have been performed with the enzymatic assay as the major one. Not all the bis-iridoids have shown biological activity, and some have shown activities only for some assays, with effectiveness values both higher and lower than the positive controls when present. No clear preference of bis-iridoids for a specific biological activity among the studied ones has been observed, given that they exert, at least, one, except immunosuppressive. However, bis-iridoids have mostly shown anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral and enzymatic inhibitory effects, which are in perfect agreement with those reported for simple iridoids [9,242]. In-depth structure—activity relation speeches are not so easy to perform at the moment, because biological studies on bis-iridoids have been few, too sectorial and generally not specific from this point of view. Nevertheless, a generic conclusion from the careful observation of Table 2 indicates that the presence and the type of substituent, as well as the type of sub-unity, greatly affect the activity and the effectiveness of bis-iridoids, as already observed for simple iridoids [9,242]. At the moment, the comparison of the effectiveness values between bis-iridoids and simple iridoids cannot be performed as well, for the same previous reasons but also because some bis-iridoids are unconventionally structured (there is no base structure to compare to), almost all bis-iridoids are constituted by different sub-units (it is impossible to establish the starting compound) and the bond between the sub-units of bis-iridoids transforms the base structure and modifies its geometry (the comparison may not be reliable due to possible different mechanisms of action). Under all these last aspects, it is obvious that bis-iridoids need to be further studied.

5. Conclusions

In this review paper, two hundred and eighty-eight bis-iridoids have been listed and detailed with their occurrence in plants and the methodologies of extraction, isolation and identification and also one hundred and fifty-nine out of these with their biological activities. The bis-iridoids reported so far in the literature are mainly characterized by the link between two seco-iridoids sub-units under the structural profile and mostly exert anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral and enzymatic inhibitory activities, both with good and low effectiveness values. The chemophenetic evaluation has allowed to individuate cantleyoside, laciniatosides, sylvestrosides and GI3 and GI5 as chemophenetic markers for the Caprifoliaceae and Oleaceae families, respectively, and oleonuezhenide and (Z)-aldosecologanin and centauroside as chemophenetic markers for the Ligustrum and Lonicera genus, respectively. Yet, many aspects of bis-iridoids are still to be discovered, elucidated and completed, and this review paper, meaning to work as a multi-comprehensive database for the future, has clearly proven this.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F.; investigation, C.F., A.V., D.D.V., M.G. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.F., A.V., D.D.V., M.G. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, C.F., A.V., D.D.V., M.G. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bianco, A. The Chemistry of Iridoids. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 1990, 7, 439–487. [Google Scholar]

- Dinda, B.; Debnath, S.; Harigaya, Y. Naturally occurring iridoids. A review, part 1. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 159–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinda, B.; Debnath, S.; Harigaya, Y. Naturally occurring secoiridoids and bioactivity of naturally occurring iridoids and secoiridoids. A review, Part 2. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 689–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinda, B.; Chowdhury, D.R.; Mohanta, B.C. Naturally occurring iridoids, secoiridoids and their bioactivity. An updated review, part 3. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 57, 765–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinda, B.; Debnath, S.; Banika, R. Naturally occurring iridoids and secoiridoids. An updated review, part 4. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 803–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, H.; Uesato, S. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; Zechmeister, L., Herz, W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 50, p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisalberti, E.L. Biological and pharmacological activity of naturally occurring iridoids and secoiridoids. Phytomedicine 1998, 5, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tundis, R.; Loizzo, M.R.; Menichini, F.; Statti, G.A.; Menichini, F. Biological and pharmacological activities of iridoids: Recent developments. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gong, X.; Bo, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zang, E.; Zhang, C.; Li, M. Iridoids: Research advances in their phytochemistry, biological activities, and pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2020, 25, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.-D.; Chou, G.-X.; Zhao, S.-M.; Zhang, C.-G. New iridoid glucosides from Caryopteris incana (Thunb.) Miq. and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, L.; Fddai, S.; Serafini, M.; Cometa, M.F. Bis-iridoid glucosides from Abelia chinensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 998–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehbili, M.; Magid, A.A.; Hubert, J.; Kabouche, A.; Voutquenne-Nazabadioko, L.; Renault, J.-H.; Nuzillard, J.-M.; Morjani, H.; Abedini, A.; Gangloff, S.C.; et al. Two new bis-iridoids isolated from Scabiosa stellata and their antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase and cytotoxic activities. Fitoterapia 2018, 125, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, K.; Sasaki, H.; Iijima, T.; Kikuchi, M. Studies on the constituents of Lonicera species. XVII. New iridoid glycosides of the stems and leaves of Lonicera japonica Thunb. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulia, A.J.; Vercauterent, J.; Mariotte, A.M. Iridoids and flavones from Gentiana depressa. Phytochemistry 1996, 42, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-X.; Liu, C.-T.; Liu, Q.-B.; Ren, J.; Li, L.-Z.; Huang, X.-X.; Wang, Z.-Z.; Song, S.-J. Iridoid glycosides from the flower buds of Lonicera japonica and their nitric oxide production and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Hao, H.; Li, J.; Xuan, J.; Xia, M.-F.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Three new secoiridoid glycosides from the flower buds of Lonicera japonica. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Shan, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. New iridoid glucoside from Pterocephalus hookeri. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 35, 2441–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Yang, R.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F. Quality evaluation of Lonicerae Japonicae Flos from different origins based on high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fingerprinting and multicomponent quantitative analysis combined with chemical pattern recognition. Phytochem. Anal. 2024, 35, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Ji, W.; Liu, S.; Fan, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, X. Metabolomics analysis of different tissues of Lonicera japonica Thunb. based on liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry. Metabolites 2023, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.B.; Kang, S.-J.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, D.Y.; Han, S.I.; Kim, T.B.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Yang, T.-J.; Sung, S.H. Chemical and genomic diversity of six Lonicera species occurring in Korea. Phytochemistry 2018, 155, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Jiang, C.-X.; Tang, Y.; Ma, G.-L.; Tong, Y.-P.; Jin, Z.-X.; Zang, Y.; Osman, E.E.A.; Li, J.; Xiong, J.; et al. Structurally diverse glycosides of secoiridoid, bisiridoid, and triterpene-bisiridoid conjugates from the flower buds of two Caprifoliaceae plants and their ATP-citrate lyase inhibitory activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 120, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, F.; Tagawa, M.; Matsuda, S.; Kikuchis, T.; Uesato, S.; Inouye, K. Abeliosides A And B, secoiridoid glucosides from Abelia grandiflora. Phytochemisty 1985, 24, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, N.N.; Kodama, T.; Lae, K.Z.W.; Win, Y.Y.; Ngwe, H.; Abe, I.; Morita, H. Bis-iridoid and iridoid glycosides: Viral protein R inhibitors from Picrorhiza kurroa collected in Myanmar. Fitoterapia 2019, 134, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, R.; Qiu, Y.; Meng, F.; Liao, Z.; Lan, X.; Chen, M. Ptehosides A-I: Nine undescribed iridoids with in vitro cytotoxicity from the whole plant of Pterocephalus hookeri (C.B. Clarke) Höeck. Phytochemistry 2024, 223, 114144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, A.; Fujii, K.; Tomatsu, S.; Takao, C.; Tanahashi, T.; Nagakura, N.; Chen, C.-C. Six secoiridoid glucosides from Adina racemosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-F.; Starks, C.M.; Williams, R.B.; Rice, S.M.; Norman, V.L.; Olson, K.M.; Hough, G.W.; Goering, M.G.; ONeil-Johnson, M.; Eldridge, G.R. Secoiridoid glycosides from the pitcher plant Sarracenia alata. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, E.M.A.; El Sayed, A.M.; Tadros, S.H.; Soliman, F.M. Chemical and biological analysis of the bioactive fractions of the leaves of Scaevola taccada (Gaertn.) Roxb. Int. J. Pharma. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 13, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Guiso, M.; Martino, M.; Nicoletti, M.; Serafini, M.; Tomassini, L.; Mossa, L.; Poli, F. Iridoids from endemic Sardinian Linaria species. Phytochemistry 1996, 42, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Passacantilli, P.; Righi, G.; Nicoletti, M.; Serafini, M.; Garbarino, J.A.; Gambaro, V. Argylioside, a dimeric iridoid glucoside from Argylia radiata. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 946–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Marini, E.; Nicoletti, M.; Foddai, S.; Garbarino, J.A.; Piovano, M.; Chamy, M.T. Bis-iridoid glucosides from the roots of Argylia radiata. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 4203–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.A.; Kufer, K.K.; Dietl, K.G.; Weigend, M. A dimeric iridoid from Loasa acerifolia. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1705–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.S.; Woo, E.-R.; Park, H.; Lee, Y.S. New iridoids from Asperula maximowiczii. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; He, X.; Wang, Y. Anti-inflammatory iridoid glycosides from Paederia scandens (Lour.) Merrill. Phytochemistry 2023, 212, 113705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılınc, H.; Masullo, M.; Lauro, G.; D’Urso, G.; Alankus, O.; Bifulco, G.; Piacente, S. Scabiosa atropurpurea: A rich source of iridoids with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity evaluated by in vitro and in silico studies. Phytochemistry 2023, 205, 113471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkrief, R.; Ranarivelo, Y.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Tillequin, F.; Koch, M.; Pusset, J.; Sévenet, T. Monoterpene alkaloids, iridoids and phenylpropanoid glycosides from Osmanthus ustrocaledonica. Phytochemistry 1998, 47, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Nagakura, N.; Akita, T.; Nishi, T.; Tanahashi, T. Phenolic and iridoid glycosides from Strychnos axillaris. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuendet, M.; Hostettmann, K.; Potterat, O.; Dyatmiko, W. Iridoid glucosides with free radical scavenging properties from Fagraea blumei. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, K.; Asano, J.; Kikuchi, M. Caeruleosides A and B, bis-iridoid glucosides from Lonicera caerulea. Phytochemistry 1995, 39, 111–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sévenet, T.; Thal, C.; Potier, P. Isolement et structure du cantleyoside: Nouveau glucoside terpénique de Cantleya corniculata (Becc.) Howard, (Icacinacées). Tetrahedron 1971, 27, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Sasaki, H.; Taguchi, M.H. Studies on the constituents of Scabiosa japonica Miq. Yakugaku Zasshi 1976, 96, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, W.R.; Lyse-Petersen, S.E.; Nielsen, B.J. Novel bis-iridoid glucosides from Dipsacus sylvestris. Phytochemistry 1979, 18, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oszmiański, J.; Wojdyło, A.; Juszczyk, P.; Nowicka, P. Roots and leaf extracts of Dipsacus fullonum L. and their biological activities. Plants 2020, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaltsounis, A.L.; Sbahi, S.; Demetzos, C.; Pusset, J. Plants in New Caledonia. Iridoids from Scaevola montana Labill. Ann. Pharma. Franc. 1989, 47, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Tillequin, F.; Koch, M.; Pusset, J.; Chauvière, G. Iridoids from Scaevola racemigera. Planta Med. 1989, 55, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocsis, Á.; Szabó, L.F.; Podanyi, B. New bis-iridoids from Dipsacus laciniatus. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasi, S.; Aligiannis, N.; Chinou, I.B.; Skaltsounis, A.L. Chemical constituents and their antimicrobial activity from the roots of Cephalaria ambrosioides. In Natural Products in the New Millennium: Prospects and Industrial Application; Proceedings of the Phytochemical Society of Europe; Rauter, A.P., Palma, F.B., Justino, J., Araújo, M.E., dos Santos, S.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 47. [Google Scholar]

- Papalexandrou, A.; Magiatis, P.; Perdetzoglou, D.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Chinou, I.B.; Harvala, C. Iridoids from Scabiosa variifolia (Dipsacaceae) growing in Greece. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2003, 31, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Liu, H.-Y.; Yu, S.-S.; Fang, W.-S. On the chemical constituents of Dipsacus asper. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 1677–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Shen, J.; Yang, Z. A new iridoid glycoside from the roots of Dipsacus asper. Molecules 2012, 17, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Tanaka, K.; Watanabe, S.; Tezuka, Y.; Saiki, I. Dipasperoside A, a novel pyridine alkaloid-coupled iridoid glucoside from the roots of Dipsacus asper. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ling, T.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, L.; Lu, Y. High performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization and quadrupole time-of-flight–mass spectrometry as a powerful analytical strategy for systematic analysis and improved characterization of the major bioactive constituents from Radix Dipsaci. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 98, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, W.; Ma, B.; Guo, B. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of furofuran lignans, iridoid glycosides, and phenolic acids in Radix Dipsaci by UHPLC-Q-TOF/MS and UHPLC-PDA. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 154, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, A.; Oya, N.; Kawaguchi, E.; Nishio, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Kawachi, E.; Akita, T.; Nishi, T.; Tanahashi, T. Secoiridoid glucosides from Strychnos spinosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1434–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Nagakura, N.; Nishi, T.; Tanahashi, T. A quinic acid ester from Strychnos lucida. J. Nat. Med. 2006, 60, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcemal, D.; Masullo, M.; Alankuş, O.; Ïkan, Ç.; Karayıldırım, T.; Şenol, S.G.; Piacente, S.; Bedir, E. Monoterpenoid glucoindole alkaloids and iridoids from Pterocephalus pinardii. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2010, 48, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafayeva, K.; Mahiou-Leddet, V.; Suleymanov, T.; Kerimov, Y.; Ollivier, E.; Elias, R. Chemical constituents from the roots of Cephalaria kotschyi. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2011, 47, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaev, E.E.; Mahiou-Leddet, V.; Mabrouki, F.; Herbette, G.; Garaev, E.A.; Ollivier, E. Chemical constituents from roots of Cephalaria media. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014, 50, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhu, G. Secoiridoid/iridoid subtype bis-iridoids from Pterocephalus hookeri. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2014, 52, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Guo, F.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of a standardized extract of bis-iridoids from Pterocephalus hookeri. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 216, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-Q.; Sheng, D.-L. Chemical constituents from Pterocephalus hookeri and their neuroprotection activities. Chin. Trad. Pat. Med. 2018, 12, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Shan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. A novel tetrairidoid glucoside from Pterocephalus hookeri. Heterocycles 2017, 94, 485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Lu, Y.; Han, C.; Zhu, G. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of n-butanol extracts of Pterocephalus hookeri on Hep3B cancer cell. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 159132. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.-F.; Zeng, Y.; Li, J.-C.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, X.-L. The anti-arthritic activity of total glycosides from Pterocephalus hookeri, a traditional Tibetan herbal medicine. Pharma. Biol. 2017, 55, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Li, H.-J.; Fan, G.; Kuang, T.-T.; Meng, X.-L.; Zou, Z.-M.; Zhang, Y. Network pharmacology and UPLC-Q-TOF/MS studies on the anti-arthritic mechanism of Pterocephalus hookeri. Tropic. J. Pharma. Res. 2018, 17, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-X.; Luo, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, L.; Liu, X.-H.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Y. Pterocephanoside A, a new iridoid from a traditional Tibetan medicine, Pterocephalus hookeri. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 23, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wu, C.-Y.; Long, F.; Shen, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, S.-L. Quality evaluation of Pterocephali Herba through simultaneously quantifying 18 bioactive components by UPLC-TQ-MS/MS analysis. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 238, 115828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, F.O.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Clericuzio, M.; Porta, A.; Vidari, G. New iridoid dimer and other constituents from the traditional Kurdish plant Pterocephalus nestorianus Nábelek. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, E.; Alankus-Caliskan, Ö.; Karayildirim, T.; Bedir, E. Iridoids from Scabiosa atropurpurea L. subsp. maritima Arc. (L.). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Toumia, I.; Sobeh, M.; Ponassi, M.; Banelli, B.; Dameriha, A.; Wink, M.; Chekir Ghedira, L.; Rosano, C. A methanol extract of Scabiosa atropurpurea enhances doxorubicin cytotoxicity against resistant colorectal cancer cells in vitro. Molecules 2020, 25, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graikou, K.; Aligiannis, N.; Chinou, I.B.; Harvala, C. Cantleyoside-dimethyl-acetal and other iridoid glucosides from Pterocephalus perennis and antimicrobial activities. Z. Naturforsch. C 2002, 57, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Yamaki, M.; Yumioka, E.; Nishimura, T.; Sakina, K. Studies on the constituents of Erythraea centaurium (Linne) Persoon. 2. The structure of centauroside, a new bis-secoiridoid glucoside. Yakugaku Zasshi 1982, 102, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryuk, J.A.; Lee, H.W.; Ko, B.S. Discrimination of Lonicera japonica and Lonicera confusa using chemical analysis and genetic marker. Kor. J. Herbol. 2012, 7, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Liao, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Tan, M.; Mei, Y.; Wei, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, R.; Liu, X. A comprehensive study of the aerial parts of Lonicera japonica Thunb. based on metabolite profiling coupled with PLS-DA. Phytochem. Anal. 2020, 31, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, S.-L.; Wu, M.-H.; Li, H.-J.; Li, P. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of iridoid glycosides in the flower buds of Lonicera species by capillary high performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometric detector. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 564, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Song, Y.; Li, P. Capillary high-performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry for simultaneous determination of major flavonoids, iridoid glucosides and saponins in Flos Lonicerae. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1157, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.-T.; Chen, J.; Song, Y.; Sheng, L.-S.; Li, P.; Qi, L.-W. Identification and quantification of 32 bioactive compounds in Lonicera species by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 48, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Qi, L.-W.; Li, H.-Y.; Li, P.; Yi, L.; Ma, H.-L.; Tang, D. Simultaneous determination of iridoids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and saponins in Flos Lonicerae and Flos Lonicerae Japonicae by HPLC-DAD-ELSD coupled with principal component analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 3181–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Z.-M.; Li, H.-J.; Li, P.; Ren, M.-T.; Tang, D. Simultaneous qualitation and quantification of thirteen bioactive compounds in Flos Lonicerae by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detector and Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Jeon, J.-E.; Kang, G.W.; Kang, S.S.; Shin, J. Simultaneous analysis of bioactive metabolites from Lonicera japonica flower buds by HPLC-DAD-MS/MS. Yakhak Hoeji 2008, 52, 446–451. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Kang, S.-S. Phytochemical studies on Lonicerae flos (1)-isolation of iridoid glycosides and other constituents. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2010, 16, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.-J.; Yu, B.-Y. Screening of peroxynitrite scavengers in Flos Lonicerae by using two new methods, an HPLC-DAD-CL technique and a peroxynitrite spiking test followed by HPLC-DAD analysis. Phytochem. Anal. 2016, 27, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Xie, X.; Wang, B.; Jin, Y.; Wang, L.; Yin, G.; Wang, J.; Bi, K.; Wang, T. Chemical pattern recognition for quality analysis of Lonicerae Japonicae Flos and Lonicerae Flos based on ultra-high performance liquid chromatography and anti-SARS-CoV2 main protease activity. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 810748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-J.; Kuang, X.-P.; Wang, W.-J.; Wan, C.-P.; Li, W.-X. Comparison of chemical constitution and bioactivity among different parts of Lonicera japonica Thunb. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Laib, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Geng, Y.; Wang, X. An improved 2D-HPLC-UF-ESI-TOF/MS approach for enrichment and comprehensive characterization of minor neuraminidase inhibitors from Flos Lonicerae Japonicae. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 175, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Sun, X.; Meng, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y. Comparative study on chemical constituents of different medicinal parts of Lonicera japonica Thunb. based on LC-MS combined with multivariate statistical analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Su, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, W. Comparative investigation on chemical constituents of flower bud, stem and leaf of Lonicera japonica Thunb. by HPLC–DAD–ESI–MS/MSn and GC–MS. J. Anal. Chem. 2014, 69, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidorn, C.; Ellmerer, E.P.; Ziller, A.; Stuppner, H. Occurence of (E)-aldosecologanin in Kissenia capensis (Loasaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Su, Y.-F.; Zheng, Y.-H.; Yan, S.-L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.-M. Iridoids from the roots of Triosteum pinnatifidum. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, J.; Yang, S.; Yu, H.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T. Bioactive constituents from the whole plants of Gentianella acuta (Michx.) Hulten. Molecules 2017, 22, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akşit, H.; Gozcü, S.; Altay, A. Isolation and cytotoxic activities of undescribed iridoid and xanthone glycosides from Centaurium erythraea Rafn. (Gentianaceae). Phytochemistry 2023, 205, 113484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.-L. Iridoid glucosides from Chinese herb Lonicera chrysatha and their antitumor activity. J. Chem. Res. 2003, 676–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Liu, G.; He, K.; Zhu, N.; Dong, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Rosen, R.T.; Ho, C.-T. New unusual iridoids from the leaves of noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) show inhibitory effect on ultraviolet B-induced transcriptional activator protein-1 (AP-1) activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 2499–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunghwa, F.; Koketsu, M. Phenolic and bis-iridoid glycosides from Strychnos cocculoides. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 23, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.-P.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yu, S.-J.; Bao, J.; Yu, J.-H.; Zhang, H. Absolute structure assignment of an iridoid-monoterpenoid indole alkaloid hybrid from Dipsacus asper. Fitoterapia 2019, 135, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiatis, P.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Tillequin, F.; Seguin, E.; Cosson, J.-P. Coelobillardin, an iridoid glucoside dimer from Coelospermum billardieri. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.-R.; Liu, Z.-F.; Yang, X.-F.; Song, Y.-L.; Cui, X.-Y.; Yang, J.-Y.; Lu, C.-H.; Shen, Y.-M. Specialised metabolites as chemotaxonomic markers of Coptosapelta diffusa, supporting its delimitation as sisterhood phylogenetic relationships with Rubioideae. Phytochemistry 2021, 192, 112929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.-Y.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, M.; Cao, B.; Zeng, M.-N.; Zhou, S.-Q.; Li, M.; Cao, Y.-G.; Xie, S.-S.; Zheng, X.-K.; et al. Minor iridoid glycosides from the fruits of Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc. and their anti-diabetic bioactivities. Phytochemistry 2023, 205, 113505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.-C.; He, J.; Pan, X.-G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.-M.; Ye, X.-S.; Xia, C.-Y.; Lian, W.-W.; Yan, Y.; He, X.-L.; et al. Secoiridoid dimers and their biogenetic precursors from the fruits of Cornus officinalis with potential therapeutic effects on type 2 diabetes. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 117, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.-S.; He, J.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Zhang, L.; Qiao, H.-Y.; Pan, X.-G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.-N.; Zhang, W.-K.; Xu, J.-K. Cornusides A−O, bioactive iridoid glucoside dimers from the fruit of Cornus officinalis. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 3103–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Hao, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Yang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zheng, X.; Feng, W. Four undescribed iridoid glycosides with antidiabetic activity from fruits of Cornus officinalis Sieb. Et Zucc. Fitoterapia 2023, 165, 105393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chi, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.-X.; Wang, Z.-M.; Dai, L.-P. Revealing the effects and mechanism of wine processing on Corni Fructus using chemical characterization integrated with multi-dimensional analyses. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1730, 465100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.R.; Palazzino, G.; Federici, E.; Iurilli, R.; Delle Monache, F.; Chifundera, K.; Galeffi, C. Oligomeric secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum abyssinicum. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.K.; Michalak, B.; Woźniak, M.; Czerwińska, M.E.; Filipek, A.; Granica, S.; Kiss, A.K. Hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives and secoiridoid glycoside derivatives from Syringa vulgaris flowers and their effects on the pro-inflammatory responses of human neutrophils. Fitoterapia 2017, 121, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chulia, A.J.; Vercauterent, J.; Mariotte, A.M. Depresteroside, A mixed iridoid-secoiridoid structure from Gentiana depressa. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızıbekmez, H.; Kúsz, N.; Bérdi, P.; Zupkó, I.; Hohmann, J. New iridoids from the roots of Valeriana dioscoridis Sm. Fitoterapia 2018, 130, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.-Y.; Ai, L.-Q.; Qian, C.-Z.; Zhang, M.-D.; Mei, R.-Q. The polymer iridoid glucosides isolated from Dipsacus asper. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 33, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ma, G.; Zhang, D.; Huang, W.; Ding, G.; Hu, H.; Tu, G.; Guo, B. New lignans and iridoid glycosides from Dipsacus asper Wall. Molecules 2015, 20, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Nishidono, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Watanabe, A.; Tezuk, Y. A new monoterpenoid glucoindole alkaloid from Dipsacus asper. Nat. Prod. Comm. 2020, 15, 1934578X20917292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.G.; Ren, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, M.-N.; He, C.; Chen, X.; Fan, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Hao, Z.-Y.; Li, H.-W.; et al. Iridoid glycosides and lignans from the fruits of Gardenia jasminoides Eills. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambie, R.C.; Rutledge, P.S.; Wellington, K.D. Chemistry of Fijian plants. 13.1 Floribundal, a nonglycosidic bisiridoid, and six novel fatty esters of δ-amyrin from Scaevola floribunda. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 1303–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-D.; Ueda, S.; Inoue, K.; Akaji, M.; Fujita, T.; Yang, C.-R. Secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus malacophylla. Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Liu, S.; Guo, Y.; Bai, L.; Ho, C.-T.; Bai, N. Chemical characterization, multivariate analysis and comparison of biological activities of different parts of Fraxinus mandshurica. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2024, 38, e5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondheimer, E.; Blank, G.E.; Galson, E.C.; Sheets, F.M. Metabolically active glucosides in Oleaceae seeds. Plant Physiol. 1970, 45, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- LaLonde, R.T.; Wong, C.; Tsai, A.I.-M. Polyglucosidic metabolites of Oleaceae. The chain sequence of oleoside aglucon, tyrosol, and glucose units in three metabolites from Fraxinus americana. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 3007–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; He, K.; Ibarra, A.; Bily, A.; Roller, M.; Chen, X.; Rühl, R. Iridoids from Fraxinus excelsior with adipocyte differentiation-inhibitory and PPARr activation activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, G.; Ip, F.C.F.; Pang, H.; Ip, N.Y. New secoiridoid glucosides from Ligustrum lucidum induce ERK and CREB phosphorylation in cultured cortical neurons. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.-N.; Xu, X.-H.; Ren, D.-C.; Duan, J.-A.; Xie, N.; Tian, L.-J.; Qian, S.-H. Secoiridoid constituents from the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum. Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, L.; Mao, B.; Zhao, D.; Cui, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, X. Analysis of chemical variations between raw and wine processed Ligustri Lucidi Fructus by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–Q-Exactive Orbitrap/MS combined with multivariate statistical analysis approach. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2021, 35, 5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-J.; Wang, J.; Yin, Z.-Q.; Ye, W.-C. Two new dimeric secoiridoid glycosides from the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum. J. Asian. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 12, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Osmanthus fragrans seeds, a source of secoiridoid glucosides and its antioxidizing and novel platelet-aggregation inhibiting function. J. Func. Foods 2015, 14, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, Q.-M.T.; Lee, H.-S.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Kim, J.A.; Woo, M.-H.; Min, B.S. Chemical constituents from the fruits of Ligustrum japonicum and their inhibitory effects on T cell activation. Phytochemistry 2017, 141, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Karadeniz, F.; Kong, C.-S.; Seo, Y. Evaluation of MMP inhibitors isolated from Ligustrum japonicum fructus. Molecules 2019, 24, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Zheng, Z.; Ren, X.; Ho, C.-T.; Bai, N. Anti-obesity and gut microbiota modulation effect of secoiridoid-enriched extract from Fraxinus mandshurica seeds on high-fat diet-fed mice. Molecules 2020, 25, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Nagakura, N. Two dimeric secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum polyanthum. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaliş, I.; Kirmizibekmez, H.; Sticher, O. Iridoid glycosides from Globularia trichosantha. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tundis, R.; Peruzzi, L.; Colica, C.; Menichini, F. Iridoid and bisiridoid glycosides from Globularia meridionalis (Podp.) O. Schwarz aerial and underground parts. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012, 40, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, M.; Bucar, F.; Pilepić, K.H. LC-PDA-ESI-MSn analysis of phenolic and iridoid compounds from Globularia spp. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 51, 1211–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frišcíc, M.; Petlevski, R.; Kosalec, I.; Maduníc, J.; Matulíc, M.; Bucar, F.; Pilepíc, K.H.; Maleš, Ž. Globularia alypum L. and related species: LC-MS profiles and antidiabetic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and anticancer potential. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmizibekmez, H.; Çaliş, I.; Akbay, P.; Sticher, O. Iridoid and bisiridoid glycosides from Globularia cordifolia. Z. Naturforsch. C 2003, 58, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, J.; Lu, X.Q.Y.; Li, R.; Guo, J.; Guo, F.; Li, Y. Monoterpenoids and triterpenoids from Pterocephalus hookeri with NF-kB inhibitory activity. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 13, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, S.; Machida, K.; Kikuchi, M. Ilicifoliosides A and B, bis-secoiridoid glycosides from Osmanthus ilicifolius. Heterocycles 2007, 74, 937–941. [Google Scholar]

- Dinda, B.; Debnath, S.; Majumder, S.; Arima, S.; Sato, N.; Harigaya, Y. A new bisiridoid glucoside from Mussaenda incana. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2006, 10, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, H. Iridolinarins A, B, and C: Iridoid esters of an iridoid glucoside from Linaria japonica. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Akimoto, M.; Okuda, A.; Kusunoki, Y.; Suekawa, C.; Nagakua, N. Six secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum polyanthum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 45, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bonilla, M.; Salido, S.; van Beek, T.A.; de Waard, P.; Linares-Palomino, P.J.; Sánchez, A.; Altarejos, J. Isolation of antioxidative secoiridoids from olive wood (Olea europaea L.) guided by on-line HPLC-DAD-radical scavenging detection. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salido, S.; Perez-Bonilla, M.; Adams, R.P.; Altarejos, J. Phenolic components and antioxidant activity of wood extracts from 10 main Spanish olive cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6493–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, W.; Li, H.-B.; Fang, H.; Yang, B.; Huang, W.-Z.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Z.-Z. A new dimeric secoiridoids derivative, japonicaside E, from the flower buds of Lonicera japonica. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-B.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.-Z.; Dai, Y.; Gao, H.; Xiao, W.; Yao, X.-S. Iridoid and bis-iridoid glucosides from the fruit of Gardenia jasminoides. Fitoterapia 2013, 88, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.-Y.; Li, P.; Huang, W.; Wang, J.-J.; Liu, Y.-J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.-L.; Wu, S.-B.; Kennelly, E.J.; Long, C.-L. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory caffeoyl phenylpropanoid and secoiridoid glycosides from Jasminum nervosum stems, a Chinese folk medicine. Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Nagakura, N.; Nishi, T. Secoiridoid glucosides esterified with a cyclopentanoid monoterpene unit from Jasminum nudiflorum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, Y.; Tanahashi, T.; Taguchi, H.; Nagakura, N.; Nishi, T. Nine new secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum nudiflorum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.J.; Suh, W.S.; Subedi, L.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, S.U.; Lee, K.R. Secoiridoid glucosides from the twigs of Syringa oblata var. dilatata and their neuroprotective and cytotoxic activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 65, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shiekh, R.A.; Saber, F.R.; Abdel-Sattar, E.A. In vitro anti-hypertensive activity of Jasminum grandiflorum subsp. floribundum (Oleaceae) in relation to its metabolite profile as revealed via UPLC-HRMS analysis. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1158, 122334. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, X.; Li, W.; Sasaki, T.; Li, Q.; Mitsuhata, N.; Asada, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Koike, K. Secoiridoid glucosides and related compounds from Syringa reticulata and their antioxidant activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 6426–6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Hsieh, P.-W. Four new secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum urophyllum. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Nagakura, N.; Nishi, T. Three secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum nudiflorum. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Hsieh, P.-W. Secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum urophyllum. Phytochemistry 1997, 46, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handjieva, N.; Tersieva, L.; Popov, S.; Evstatieva, L. Two iridoid glucosides, 5-O-menthiafoloylkickxioside and kickxin, from Kickxia dum. species. Phytochemistry 1995, 39, 925–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, M.; Kigoshi, H.; Uemura, D. Isolation and Structure of Korolkoside, a bis-iridoid glucoside from Lonicera korolkovii. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1090–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-Q.; Wang, Z.-P.; Zhu, H.; Li, G.; Wang, X. Chemical constituents of Lonicera japonica roots and their anti-inflammatory effects. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2016, 51, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Sarıkahya, N.B.; Pekmez, M.; Arda, N.; Kayce, P.; Karabay Yavasoğlu, N.Ü.; Kırmızıgül, S. Isolation and characterization of biologically active glycosides from endemic Cephalaria species in Anatolia. Phytochem. Lett. 2011, 4, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikahya, N.B.; Kirmizigül, S. Novel biologically active glycosides from the aerial parts of Cephalaria gazipashensis. Turk. J. Chem. 2012, 36, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, L.; Foddai, S.; Nicoletti, M. Iridoids from Dipsacus ferox (Dipsacaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 1083–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Ali, A.E.; Youssef, F.S.; El-Ahmady, S.H. LC-qTOF-MS/MS phytochemical profiling of Tabebuia impetiginosa (Mart. Ex DC.) Standl. leaf and assessment of its neuroprotective potential in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 331, 118292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podanyi, B.; Reid, R.S.; Kocsis, A.; Szabó, L. Laciniatoside V: A new bis-iridoid glucoside. isolation and structure elucidation by 2D NMR spectroscopy. J. Nat. Prod. 1989, 52, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikahya, N.B.; Goren, A.C.; Kirmizigul, S. Simultaneous determination of several flavonoids and phenolic compounds in nineteen different Cephalaria species by HPLC-MS/MS. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 173, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamoud, G.A.; Orfali, R.S.; Takeda, Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Yamano, Y.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Fantoukh, O.I.; Amina, M.; Otsuka, H.; Matsunami, K. Lasianosides F–I: A new iridoid and three new bis-iridoid glycosides from the leaves of Lasianthus verticillatus (Lour.) Merr. Molecules 2020, 25, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Bi, J.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G. An HPLC method for simultaneous quantitative determination of seven secoiridoid glucosides separated from the roots of Ilex pubescens. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2017, 31, e3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunaga, K.; Koike, K.; Fukuda, H.; Ishii, K.; Ohmoto, T. Ligustrinoside, a new bisiridoid glucoside from Strychnos ligustrina. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991, 39, 2737–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, M.; Hostettmann, M.; Stoeckli-evans, H.; Solis, P.; Gupta, M.; Hostettmann, K. A novel type of dimeric secoiridoid glucoside from Lisianthus jefensis. Planta Med. 1989, 55, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.A.; Weigend, M. Loasafolioside, a minor iridoid dimer from the leaves of Loasa acerifolia. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.-J.; Liu, Z.-M. Phenylpropanoid and iridoid glycosides from Pedicularis longiflora. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 3125–3127. [Google Scholar]

- de Moura, V.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.S.; Corrêa, J.G.S.; Peixoto, M.A.; Souza, G.K.; Morais, D.; Bonfim-Mendonça, P.S.; Svidzinski, T.I.E.; Pomini, A.M.; Meurerd, E.C.; et al. Minutifloroside, a new bis-iridoid glucoside with antifungal and antioxidant activities and other constituents from Pacourea minutiflora. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2020, 31, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Pu, X.-Y.; Yang, C.-R. Iridoidal glycosides from Jasminum sambac. Phytochemistry 1995, 38, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somanadhan, B.; Wagner Smitt, U.; George, V.; Pushpangadan, P.; Rajasekharan, S.; Duus, J.O.; Nyman, U.; Olsen, C.E.; Jaroszewski, J.W. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors from Jasminum azoricum and Jasminum grandiflorum. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-F.; Gao, J.; Zhao, C.; Chen, C.-Y. Secoiridoids glycosides from some selected Jasminum spp. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2000, 47, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Hao, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, D.; Yang, Y.; Wei, J.; Li, M.; Zheng, X.; Feng, W. Neocornuside A–D, four novel iridoid glycosides from fruits of Cornus officinalis and their antidiabetic activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Nagakura, N. Three secoiridoid glucosides esterified with a linear monoterpene unit and a dimeric secoiridoid glucoside from Jasminum polyanthum. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-C.; Yang, J.; Li, J.-K.; Liang, X.-H.; Sun, J.-L. Two new secoiridoid glucosides from the twigs of Cornus officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2016, 52, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipek, A.; Wyszomierska, J.; Michalak, B.; Kiss, A.K. Syringa vulgaris bark as a source of compounds affecting the release of inflammatory mediators from human neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 30, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, Y.; Koshino, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Yamada, T.; Nakagawa, L. New secoiridoid glucosides from Ligustrum japonicum. Planta Med. 1987, 53, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.H.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, Y.C. A new neuroprotective compound of Ligustrum japonicum leaves. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Sugiyama, M. Studies on the constituents of Ligustrum species. XIV. Structures of secoiridoid glycosides from the leaves of Ligustrum obtusifolium Sieb. et Zucc. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1989, 109, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-M. HPLC fingerprints of crude and processed Ligustri Lucidi Fructus. Chin. Trad. Herb. Drugs 2016, 24, 760–766. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, M.; Shi, X.; Han, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhao, S.; Jia, P.; Zheng, X.; Li, X.; Xiao, C. The screened compounds from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus using the immobilized calcium sensing receptor column exhibit osteogenic activity in vitro. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 245, 116192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, M.; Michalak, B.; Wyszomierska, J.; Dudek, M.K.; Kiss, A.K. Effects of Phytochemically characterized extracts from Syringa vulgaris and isolated secoiridoids on mediators of inflammation in a human neutrophil model. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, H. Two new iridoid glucosides from Paederia scandens (Lour.) Merr. var. mairei (Leveille) Hara. Nat. Med. 2002, 56, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.-C.; Wang, J.-H.; Fang, D.-M.; Wu, Z.-J.; Zhang, G.-L. Analyses of the iridoid glucoside dimers in Paederia scandens using HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2013, 24, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Peng, S.; Liu, X.; Bai, B.; Ding, L. Sulfur-containing iridoid glucosides from Paederia scandens. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zou, X.; Liu, X.; Peng, S.-L.; Ding, L.-S. Multistage electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analyses of sulfur-containing iridoid glucosides in Paederia scandens. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 21, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Hou, B.; Yang, L.; Ma, R.-J.; Li, J.-Y.; Hu, J.-M.; Zhou, J. Iridoids and bis-iridoids from Patrinia scabiosaefolia. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24940–24949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Niu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Meng, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Hu, J.; Kang, W. Nine unique iridoids and iridoid glycosides from Patrinia scabiosaefolia. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 657028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaweetripob, W.; Thongnest, S.; Boonsombat, J.; Batsomboon, P.; Salae, A.W.; Prawat, H.; Mahidol, C.; Ruchirawat, S. Phukettosides A–E, mono- and bis-iridoid glycosides, from the leaves of Morinda umbellata L. Phytochemistry 2023, 216, 113890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damtoft, S.; Franzyk, H.; Jensen, S.R. Iridoid glucosides from Picconia excelsa. Phytochemistry 1997, 45, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, D.T.M.; Phung, N.K.P.; Diem, T.A.; Nhung, N.T.; Nhan, L.C.; Du, N.X.; Dung, N.T.M. Identification of compounds from ethylacetate of Leonotis nepetifolia (L.) R.Br. (Lamiaceae). J. Sci. Technol. Food 2020, 20, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Inoue, N.; Manse, Y.; Matsuura, H.; Hamasaki, S.; Yoshikawa, M.; Muraoka, O.; Ninomiya, K. Acylated iridoid glycosides with hyaluronidase inhibitory activity from the rhizomes of Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. Phytochemistry 2020, 169, 112185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hawary, S.S.; El-Hefnawy, H.M.; Osman, S.M.; Mostafa, E.S.; Mokhtar, F.A.; El-Raey, M.A. Chemical profile of two Jasminum sambac L.(Ait) cultivars cultivated in Egypt-their mediated silver nanoparticles synthesis and selective cytotoxicity. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2019, 11, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hawary, S.S.; El-Hefnawy, H.M.; Osman, S.M.; El-Raey, M.A.; Mokhtar, F.A.; Ibrahim, H.A. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activities of Jasminum multiflorum (Burm. F.) Andrews leaves towards MCF-7 breast cancer and HCT 116 colorectal cell lines and identification of bioactive metabolites. Anti-Cancer Ag. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2572–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, H.; Takushi, A.; Hirata, E.; Ide, T.; Otsuka, H.; Takeda, Y. Premnaodorosides D-G: Acyclic monoterpenediols iridoid glucoside diesters from leaves of Premna subscandens. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaidomy, A.H.; Alhadrami, H.A.; Amin, E.; Aly, H.F.; Othman, A.M.; Rateb, M.E.; Hetta, M.H.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Hassan, H.M. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of terpene- and polyphenol-rich Premna odorata leaves on alcohol-inflamed female Wistar albino rat liver. Molecules 2020, 25, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Ying, Y.-J.; Guo, F.-J.; Zhu, G.-F. Bis-iridoid and lignans from traditional Tibetan herb Pterocephalus hookeri. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2014, 56, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Guo, C.-X.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Li, Y.-M.; Guo, F.-J.; Zhu, G.-F. Four new bis-iridoids isolated from the traditional Tibetan herb Pterocephalus hookeri. Fitoterapia 2014, 98, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.-F.; Miao, L.; Zhang, J.-S.; Zhang, H. Bis-iridoids from Pterocephalus hookeri and evaluation of their anti-inflammatory activity. Chem. Biodiversity 2022, 19, e202100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, E.; Hosny, M.; El-Hela, A.; Boroujerdi, A. New iridoid glycosides from Anarrhinum pubescens. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, B.; Cui, Y.; Chen, X.; Bi, J.; Zhang, G. Two new secoiridoid glucosides and a new lignan from the roots of Ilex pubescens. J. Nat. Med. 2018, 72, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.; Passacantilli, P.; Rispoli, C.; Nicoletti, M.; Messana, I.; Garbarino, J.A.; Gambaro, V. Radiatoside, a new bisiridoid from Argylza radiata. J. Nat. Prod. 1986, 49, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Passacantilli, P.; Righi, G.; Nicoletti, M.; Serafini, M.; Garbarino, J.A.; Gambaro, V.; Chamy, M.C. Radiatoside B and C, two new bisiridoid glucosides from Argylia radiata. Planta Med. 1987, 53, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.; Passacantilli, P.; Garbarino, J.A.; Gambaro, V.; Serafini, M.; Nicoletti, M.; Rispoli, C.; Righi, G. A new non-glycosidic iridoid and a new bisiridoid from Argylia radiata. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerski, L.; Furlan, M.; Silva, D.H.S.; Cavalheiro, A.J.; Nogueira Eberlin, M.; Tomazel, D.M.; da Silva Bolzani, V. Iridoid glucosides from Randia spinosa (Rubiaceae). Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Li, S.; Niu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, H. Rapulasides A and B: Two novel intermolecular rearranged biiridoid glucosides from the roots of Heracleum rapula. Tetrahedr. Lett. 2005, 46, 5743–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-P.; Huang, S.-S.; Lee, T.-H.; Chang, C.-I.; Kuo, T.-F.; Huang, G.-J.; Kuo, Y.-H. Four new iridoid metabolites have been isolated from the stems of Neonauclea reticulata (Havil.) Merr. with anti-inflammatory activities on LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yin, W.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Z.; Xia, J. A new iridoid glycoside and potential MRB inhibitory activity of isolated compounds from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1732–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H. Phenolic and iridoid glycosides from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus L. Med. Chem. Res. 2013, 22, 4830–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, Y.; Okazaki, N.; Tanahashi, T.; Nagakura, N.; Nishi, T. Secoiridoid and iridoid glucosides from Syringa afghanica. Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.-J.; Chan, Y.-Y. Five new iridoids from roots of Salvia digitaloides. Molecules 2014, 19, 15521–15534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, S.-K.; Komorita, A.; Tanaka, T.; Fujioka, T.; Mihashi, K.; Kouno, I. Sulfur-containing bis-iridoid glucosides and iridoid glucosides from Saprosma scortechinii. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.-K.; Komorita, A.; Tanaka, T.; Fujioka, T.; Mihashi, K.; Kouno, I. Iridoids and anthraquinones from the Malaysian medicinal plant, Saprosma scortechinii (Rubiaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Brown, A.S.; Veitch, N.C.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Leaf chemistry and foliage avoidance by the thrips Frankliniella occidentalis and Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis in Glasshouse Collections. J. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 37, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Hostettmann, K.; Stoeckli-Evans, H.; Gupt, M.P. Monoterpene dimers from Lisianthius seemannii. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendamene, S.; Boutaghane, N.; Sayagh, C.; Magid, A.A.; Kabouche, Z.; Bensouici, C.; Voutquenne-Nazabadioko, L. Bis-iridoids and other constituents from Scabiosa semipapposa. Phytochem. Lett. 2022, 49, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaliş, Í.; Ersoz, T.; Chulla, A.J.; Rüedi, P. Septemfidoside: A new bis-iridoid diglucoside from Gentiana septemfida. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Gadimli, A.I.; Isaev, J.I.; Kashchenko, N.I.; Prokopyev, A.S.; Kataeva, T.N.; Chirikova, N.K.; Vennos, C. Caucasian Gentiana species: Untargeted LC-MS metabolic profiling, antioxidant and digestive enzyme inhibiting activity of six plants. Metabolites 2019, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Masuda, T.; Honda, G.; Takaishi, Y.; Ito, M.; Ashurmetov, O.A.; Khodzhimatov, O.K.; Otsuka, H. Secoiridoid glycosides from Gentiana olivieri. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 1338–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balijagić, J.; Janković, T.; Zdunić, G.; Bošković, J.; Šavikin, K.; Gođevac, D.; Stanojković, T.; Jovančević, M.; Menković, N. Chemical profile, radical scavenging and cytotoxic activity of yellow gentian leaves (Genitaneae luteae folium) grown in northern regions of Montenegro. Nat. Prod. Comm. 2012, 7, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.-A.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Ma, Y.-B.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Wang, H.-L.; Shen, Y.; Zuo, A.-X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.-J. Swerilactones A and B, anti-HBV new lactones from a traditional Chinese Herb: Swertia mileensis as a treatment for viral hepatitis. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4120–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, C.-A.; Zhang, X.-M.; Ma, Y.-B.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Liu, J.-F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.-J. Three new secoiridoid glycoside dimers from Swertia mileensis. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 12, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Ma, Y.-B.; Cao, T.-W.; Wang, H.-L.; Jiang, G.-Q.; Geng, C.-A.; Zhang, X.-M.; Chen, J.-J. Seven new secoiridoids with anti-hepatitis b virus activity from Swertia angustifolia. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, A.; Urrunaga, R.; Garofalo, L.; Sorrentino, L.; Aquino, R. Phytochemical and pharmacological studies on medicinal herb Acicarpha tribuloides. Int. J. Pharmacog. 1996, 34, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-G.; Ding, K.; Xu, G.; Shen, Y.; Meng, Z.-G.; Yang, S.-C. Chemical constituents of Dipsacus asper. J. Chin. Med. Mat. 2012, 35, 1789–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Saar-Reisma, P.; Koel, M.; Tarto, R.; Vaher, M. Extraction of bioactive compounds from Dipsacus fullonum leaves using deep eutectic solvents. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1677, 463330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saar-Reisma, P.; Bragin, O.; Kuhtinskaja, M.; Reile, I.; Laanet, P.R.; Kulp, M.; Vaher, M. Extraction and fractionation of bioactives from Dipsacus fullonum L. leaves and evaluation of their anti-Borrelia activity. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, W.-J.; Li, C.-Y.; Fang, G.; Zhang, Y. UFLC-PDA fingerprint of Tibetan medicine Pterocephalus hookeri. China J. Chin. Mat. Med. 2014, 39, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Arráez-Román, D.; Al-Nuri, M.; Warad, I.; Segura-Carretero, A. Untargeted metabolite profiling and phytochemical analysis of Micromeria fruticosa L. (Lamiaceae) leaves. Food Chem. 2019, 279, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletti, M.; Di Fabio, T.A.; Serafini, M.; Garbarino, J.A.; Piovano, M.; Chamy, M.C. Iridoids from Loasa tricolor. Biochem. Sys. Ecol. 1991, 19, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.A.; Weigend, M. Iridoids from Loasa acerifolia. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]